Damian Shiels's Blog, page 28

November 12, 2016

Time to Move Beyond the Irish Brigade? The Problems with Studying Ethnic Irish Units– A Case Study of the New York Irish at Gettysburg

When we think and examine the Irish of the American Civil War, we often consider first and foremost ethnic units; formations such as the Irish Brigade, Corcoran’s Legion or regimental level contingents such as the 9th Massachusetts and 69th Pennsylvania. Such units have undeniably been the focus of attention for both scholars and enthusiasts (this site included) when discussing the “Irish” of the Civil War. This is perfectly understandable- the ethnic identity of these units meant that veterans tended to highlight this “Irishness” in post-war writings, which in turn caused them to dominate the historical record. Unsurprisingly, as a result, they also dominate Civil War scholarship on the Irish. However, it is increasingly my view that these units, and what was written about them in the post-war decades by members of the Irish community, are skewing the realities of the broader Irish experience of the conflict. What was in reality an exceptional experience for the Irish of the conflict has become the central theme of how we explore, examine and remember Irish participation today.

Memorial to the New York Regiments of the Irish Brigade at Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

The reality of the American Civil War was that the vast majority of Irish who served in the conflict did not serve in ethnic Irish units. As regular readers are aware, over recent years I have been using the Widows and Dependents Pension Files to identify the letters of Irish-American soldiers, which illustrate that the Irish served in large numbers throughout the majority of Northern units. How did the experience of this majority differ (or not) from that of the Irish in the ethnic regiments? Were they fighting for the same reasons, and with the same goals? How did they view their Irish identity, and how did they view their American identity? How did they relate to the Irish at home, and were they drawn from the same communities and groupings as those who chose to serve in ethnic units? These are questions we need to explore in further detail. In many ways, the experience of this majority of Civil War Irish remains hidden from us, though I suspect they have much to teach us not only about Irish motivations during the conflict, but also Irish communities in 1860s America.

New York State Memorial, Gettysburg National Cemetery (Damian Shiels)

Of late I have been examining in some detail the New York Irish who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg. There is perhaps no clearer example of how ethnic Irish units have come to centrally dominate what we perceive to be the Irish experience of the conflict than this engagement. The Irish Brigade and it’s actions in the Wheatfield utterly dominate the perception of the Irish experience at this most famous of battlefield sites. Even during the conflict, the Irish-American press (particularly the New York Irish-American Weekly) looked to the Irish Brigade to be representative of Irish participation. This continued into the post war period, with the publication by David Power Conyngham of the Irish Brigade history only two years after war’s end, and with later writings by veterans such as St. Clair A. Mulholland. Irish Brigade veterans and the Irish-American community made sure they were remembered on the field as well, through memorials such as the Irish Brigade Monument and Father Corby statue. These are overtly connected to the Irish experience, and serve as permanent markers to Irish participation. The Irish Brigade as representative of the major Irish experience at Gettysburg (and in the wider war) continues today– for example it is often a focus of National Park Service interpretation with respect to the Irish. This is in no way a criticism of focus on the Irish Brigade. They are one of the most famed formations of the Civil War, and visiting sites associated with them and learning about their experiences is extremely popular (and something which I also greatly enjoy). The brigade’s history also serves as the most logical educational vehicle to explain the story of Irish participation in the conflict. But to what extent does the Irish Brigade actually come close to representing the entirety of the Irish experience at Gettysburg?

An excellent presentation by NPS Ranger Angie Atkinson on the Irish Brigade at Gettysburg. The experiences of the brigade dominate modern perception of the Irish at the battlefield, and is among the most popular stories of any relating to the engagement.

The Irish Brigade was a shadow of its former self at Gettysburg, taking into action some 530 men. They suffered a total of 198 casualties, heavily concentrated among members of the 28th Massachusetts, who alone lost 100. The three founding New York regiments lost 17 men killed and 50 wounded. There is no doubt this is an extremely high casualty rate given the proportion of men the Irish Brigade took into the fight. But from an ethnic Irish unit perspective, the experience of the 69th Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg fighting was significantly worse– they alone sustained 149 casualties, including 43 killed outright out of a strength of some 258. I am currently examining all the New York unit fatalities as a result of Gettysburg in an effort to gain some insight into the impact of the battle on the New York Irish community as a whole, the largest Irish community represented on the field. I am a particularly interested in those regiments and brigades that were not ethnic Irish but nonetheless contained large numbers of Irish troops, such as those which had strong Democratic Party ties. For example, an examination of those who men who died in the 42nd New York, the Tammany Regiment, shows a potential 16 men who may have been Irish-born or Irish-American, almost the same number of men who were killed outright in the entire Irish Brigade. (1)

Barrett, Daniel

Private

42 New York Infantry

C

Barron, Thomas

Private

42 New York Infantry

D

Byrne, William

Corporal

42 New York Infantry

K

Cuddy, Michael

Sergeant

42 New York Infantry

I

Cullen, James

Private

42 New York Infantry

F

Curley, Thomas

Private

42 New York Infantry

C

Flynn, William

Sergeant

42 New York Infantry

H

McGrann, Felix

Private

42 New York Infantry

F

McLear, Neal

Private

42 New York Infantry

A

McMara, Patrick

Private

42 New York Infantry

E

Moore, Charles

Sergeant

42 New York Infantry

D

Murphy, Hugh

Private

42 New York Infantry

G

O’Shea, Daniel

Private

42 New York Infantry

E

Riley, Michael

Private

42 New York Infantry

G

Smith, John

Private

42 New York Infantry

D

West, Peter

Private

42 New York Infantry

K

Table 1. 42nd New York Infantry Gettysburg Fatalities of Potential Irish Ethnicity (After Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg)

Memorial to the 42nd New York Infantry, the Tammany Regiment, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Another regiment with ties to the Democratic Party was the 40th New York Infantry, the Mozart Regiment. An examination of their Gettysburg related deaths reveals the names of 8 men who may have been Irish or Irish-American, comparable to all but one of the New York Irish Brigade regiments.

Fleming, George

Private

40 New York Infantry

B

Harding, Michael

Private

40 New York Infantry

C

Horrgian, Timothy

Private

40 New York Infantry

F

Kelly, Timothy

Private

40 New York Infantry

D

O’Brien, Thomas

Private

40 New York Infantry

C

O’Harra, Daniel

Private

40 New York Infantry

G

Slattery, Jeremiah D

Sergeant

40 New York Infantry

C

Sweeny, Francis

Private

40 New York Infantry

D

Table 2. 40th New York Infantry Gettysburg Fatalities of Potential Irish Ethnicity (After Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg)

Above the regimental level, there is one brigade level New York unit whose losses in all likelihood had a significantly greater impact on the Irish and Irish-American community in New York in real terms than those of the Irish Brigade. The Excelsior Brigade consisted of the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd and 74th New York (the 120th New York also formed part of the brigade at Gettysburg). They had been formed in New York and were initially led by Dan Sickles, who by Gettysburg commanded the Third Corps. The regiments had a strong Irish flavour. Joseph Hopkins Twichell, Chaplain of the 71st New York, wrote in a letter to his brother that “at least half, I might say two thirds, of my men are Irish Catholics alone.” On 2nd July the regiments were heavily engaged in the vicinity of the Peach Orchard, sustaining significant casualties. An assessment of the brigade deaths (excluding the 120th New York) identifies as many as 50 men who fell who may have been Irish or Irish-American. It would be reasonable to assume that in the case of the vast majority (certainly in excess of 40) they were ethnically Irish.

Detail of the New York State Memorial at Gettysburg National Cemetery (Damian Shiels)

NAME

RANK

UNIT

COMPANY

Crowley, Patrick

Private

70 New York Infantry

G

Higgins, John

Private

70 New York Infantry

G

McGraw, Matthew

Corporal

70 New York Infantry

E

McKenna, John

Private

70 New York Infantry

C

Massey, Joseph

Private

70 New York Infantry

H

Nolan, John

Private

70 New York Infantry

K

O’Connor, Robert

Private

70 New York Infantry

G

Robb, John

Private

70 New York Infantry

K

Ryan, Michael L.

Private

70 New York Infantry

C

Smith, Thomas

Private

70 New York Infantry

K

Tommy, John

Corporal

70 New York Infantry

D

Brady, James

Private

71 New York Infantry

A

Canty, Daniel

Private

71 New York Infantry

C

Holland, David

Private

71 New York Infantry

F

Kearns, Timothy

Private

71 New York Infantry

A

King, Thomas

Sergeant

71 New York Infantry

E

Olvaney, Patrick

Private

71 New York Infantry

A

Burke, Daniel L

Sergeant

72 New York Infantry

E

Colyer, John

Private

72 New York Infantry

K

Gormelly, Michael

Private

72 New York Infantry

E

Holland, Thomas

Private

72 New York Infantry

E

Coniff, John J

Sergeant

73 New York Infantry

K

Cowney, John

Private

73 New York Infantry

B

Devlin, Edward

Private

73 New York Infantry

A

Duane, Patrick

Private

73 New York Infantry

C

Flanigan, Patrick

Private

73 New York Infantry

B

Gallagher, Michael

Private

73 New York Infantry

G

Higgins, Martin E

Lieutenant

73 New York Infantry

E

Holmes, Edward

Private

73 New York Infantry

F

Keegan, Thomas F

Private

73 New York Infantry

B

Lacy, William

Private

73 New York Infantry

H

Lally, Thomas

Sergeant

73 New York Infantry

K

Lynch, Patrick

Private

73 New York Infantry

D

Malloy, Wilson M

Private

73 New York Infantry

C

McAdam, John

Private

73 New York Infantry

G

McAvoy, james

Private

73 New York Infantry

G

McCormick, Andrew

Private

73 New York Infantry

H

McGlare, George

Sergeant

73 New York Infantry

F

McIntyre. James D

Private

73 New York Infantry

G

Murphy, John

Sergeant

73 New York Infantry

B

O’Neil, James

Private

73 New York Infantry

G

Renton, John

Sergeant

73 New York Infantry

C

Shine, Eugene C

Captain

73 New York Infantry

F

Trainor, James

Private

73 New York Infantry

D

Trainor, Peter

Private

73 New York Infantry

D

Trihy, Edmund

Private

73 New York Infantry

C

Burke, Henry

Corporal

74 New York Infantry

B

Casey, John

Private

74 New York Infantry

H

McLaughlin, John

Corporal

74 New York Infantry

A

McMullen, John W

Corporal

74 New York Infantry

A

Table 3. Excelsior Brigade Gettysburg Fatalities of Potential Irish Ethnicity (After Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg)

Excelsior Brigade Memorial, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Based on the available evidence, it is reasonable to put forward that the Irish losses in the Excelsior Brigade at Gettysburg were almost certainly significantly greater than those in the Irish Brigade. There is little doubt in my mind that the fame of the Irish Brigade has masked an awareness (particularly in Ireland) of the sheer extent of Irish participation through Northern forces, and is one of a number of factors that has led to an under appreciation of just how much the war impacted large swathes of the Irish community both in America and Ireland. The experiences, social circumstances, motivations for service, and impact of fatalities on the Irish community relating to those who served outside of ethnic units are certainly worthy of more detailed attention by those of us engaged in the study of the Irish in the Civil War. To further this work, I hope in the coming weeks to produce a full list of the probable/possible Irish and Irish-American deaths associated with New York units at Gettysburg, in order to highlight this issue still further. I am in the process of examining a range of sources in order to establish ethnicity and origin, and would be grateful to any readers who can provide documentation to assist with the addition and subtraction of names to the list of New York Irish dead at Gettysburg.

73rd New York (2nd Fire Zouaves) Memorial, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

(1) OR: 175, OR: 431; (2) Butler 2012: 4;

References

New York Monuments Commission 1902. Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, Volume 1.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 27, Part 1.

Butler, Francis 2012. To Bleed for a Higher Cause: The Excelsior Brigade and the Civil War.

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, Discussion and Debate, New York Tagged: 40th New York Mozart, 42nd New York Tammany, Dan Sickles, Excelsior Brigade, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish Brigade, New York Irish

November 11, 2016

“Mother many a good man wint acrost the river but never come back, it was murder”: An Irishman at Fredericksburg & Gettysburg

I am currently working through the New York unit casualties at Gettysburg to draw together all those of Irish-birth or Irish ethnicity who lost their lives as a result of that engagement. Four men of the 65th New York Infantry (1st United States Chausseurs) died as a result of the fighting that July– almost certainly three were of Irish birth. The story of one of them, Westmeath’s John Clark, has been told on the site previously (see here). Another was John O’Brien. A few months before his death, he wrote his mother a letter– it would seem following the Battle of Fredericksburg– which described a near fatal incident during an artillery bombardment. John was once again subjected to such a bombardment at Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg on 3rd July 1863, with less fortunate results. (1)

John’s parents John and Margaret O’Brien had been married in Ireland on 26 June 1840, by a Reverend Father Delaney. They had afterwards settled in the United States, but John Senior had passed away in Paterson, New Jersey on 21st September 1852. Both Margaret and young John had to dedicate themselves to working for their own support. While her son contributed his wages towards the family rent, Margaret provided the majority of the other necessaries through her work as a servant, one of the countless “Irish Bridgets” in domestic service. During the 1860s their home was in Manhattan, at 243 Mulberry Street. (2)

Today’s 243 Mulberry Street in New York. Margaret O’Brien lived at this address in the 1860s.

Although not an Irish regiment, the 65th New York Infantry had many Irishmen in the ranks. Perhaps the most notable was Andrew Byrne, who would eventually return to Ireland and write his memoirs, now published (see here). John O’Brien was another. He had enlisted on 21st August 1861 at the age of 19, going on to serve as a private in Company H. The regiment had seen heavy fighting on the Peninsula during the summer of 1862, but had avoided the worst of the fighting at Antietam and Fredericksburg, though they were more closely involved in the action around Fredericksburg during the Chancellorsville Campaign. In John’s file is the letter he wrote to his mother, which although problematic, appears to have been composed after the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg (though there are slight errors in dates, location names and casualties, John’s description of the fighting would appear to match the regiment’s experience there). Despite the fact that the 65th was not heavily engaged, John’s correspondence provides an extremely interesting insight into cooperation with Rebels on picket duty, the strains of experiencing a bombardment, and the shock that the heavy defeat at Fredericksburg caused throughout the Army of the Potomac. (3)

VA the 22nd 1862 [sic]

camp at fare oak church [White Oak Church]

Dear Mother

wit pleasure i rite thoes fue lines to you hoping that they may finde you in good helt as the departure of them leves me at preasant thanks be to god for his mercies to us all. Dear Mother we crosed the river on the 11th and we wer the 1st Division to cross we re crost on the 17th all the time we wer on the other side we had to stand the fire of artilire the ground shuck with the fire of canon we were on picket the night our army fell back all day we had good time the rebel picket said if we did not fire on them they would not fire on us so there was no firing all day at a bout 4 oclock our artilirey opened on the rebel batrie and they made it the hotest place I ever was in the rebels did not fire a shot but our batrie sent half there shells in to our picket the most of them fell in our company but if our batrie had not opened the rebel batrie wold sweep us of the face of the ert [earth] they wer siting there pecies to open on us but ower battrie left not a man at the rebel batrie after our batrie had stoped the rebels came and drove [?] these batrie of wit hand after that we had a good time of it we fell back a bout 10 oclock that was the first we knew of our army falling back they wer a crost the river when we got relieved we could not speak above our breth until we crost the brig[e] so we wer the first and last to cros. Dear Mother I sent 60 Dolers to you on the 18th rite as soon as you get it I rote a letter to you on the 30th of last mont but got no answer rite as soon as you get this let me know how all the folkes is. Mother many a good man wint a crost the river but never come back it was murder you could compare it to any thing else we had to stay on the plane and look up on the rebels in there fortifickasions and redouts I believe they could [have] slane every man that crost the river if they opened there guns on us but thank god for it we lost about 9 out of our regt it was as looky as any in the field I may thank my aging[?] for my life the shell came so close that I doged it and it tuck the next companie it tuck two men if I had not droped to the ground as soon as the shell left the gun my hed wold have been swept of. it is very cold here nights we ar on the bankes of the river and it is more than cold you asked me how long I was enlisted for I am enlisted for the ware or 3 years I hav one yare to serve after the 1st of Jeulia [July] let me know how Mr Haley and familie is No more at preasant from your son

John O Brien. (4)

Of course, the reason this letter survives is because John O’Brien died as a result of his service. During the bombardment which the 65th New York endured at Culp’s Hill on 3rd July (the same bombardment which so horribly killed John Clark), John’s luck at dodging shells ran out. His officer later recorded that he was “killed at the Battle of Gettysburg Pa on the 3rd day of July 1863 by a solid shot passing through his body.” (5)

The monument to the 65th New York on Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg, which I took the opportunity to visit on my recent trip. Both John Clark and John O’Brien died as a result of artillery bombardment not far from this spot (Damian Shiels)

(1) John O’Brien Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) 65th New York Roster, John O’Brien Widow’s Pension File; (4) John O’Brien Widow’s Pension File; (5) Ibid.* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

WC73540 of Margaret O’Brien, Dependent Mother of John O’Brien, Company H, 65th New York Infantry.

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 65th New York Volunteer Infantry.

Gettysburg National Military Park.

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page.

Filed under: Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Gettysburg, New York Tagged: 1st U.S. Chausseurs, 65th New York Infantry, Culp's HIll, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish in Manhattan, Irish in New York, Mulberry Street Irish

November 9, 2016

Emigrant Irish Badgers: With the Second Wisconsin in Herbst’s Woods

A focus of my recent trip to the Gettysburg battlefield was to look at some of the stories of Irishmen who were among that majority who undertook their war service in non-ethnic Irish units. A number of them were to be found in the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry– part of the famed Iron Brigade– who on the first day at Gettysburg were engaged in the vicious fighting in Herbst Woods on McPherson Ridge and in the brief stand near the Lutheran Seminary. In this post I look at three of those Badger State Irish-Americans, explore their experiences, and examine their fates.

Second Wisconsin Infantry Memorial in the Herbst Woods, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

During the see-saw struggle in Herbst Woods on 1st July 1863, Private Patrick Maloney of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry spotted an opportunity. His regiment had just charged the Tennessean Confederates that opposed them, driving their foe back across the stream known as Willoughby Run from whence they had come. Continuing the pursuit, Maloney, “a brave patriotic, and fervent young Irishman”, identified amongst the Rebels none other than Brigadier-General James J. Archer, whose men the Black Hats were up against. Seemingly without hesitating, Maloney plunged into the Southerners and apprehended Archer, who initially tried to resist but was soon overwhelmed. Maloney brought his captive back to his commanding officer, Major John Mansfield, who in turn placed Archer in the hands of another Irishman in the 2nd Wisconsin, Galwegian Lieutenant Dennis Dailey. According to Dailey, so shaken was Archer by his encounter that the General appealed “for protection from Moloney.” Patrick Maloney’s actions had resulted in the first capture of an Army of Northern Virginia General since Robert E. Lee had taken command over a year before. His are probably the best known actions of any Irishman who served in the Iron Brigade at Gettysburg, though he would not live to reap any reward from them. Somewhere between the fighting in the Herbst Woods and the Brigade’s stand at the Seminary later in the day, Patrick Maloney was killed. The import of his contribution was enough to merit note in his commanding officer’s Official Report on the engagement at Gettysburg. Major Mansfield penned the account on 15 November 1863:

I ordered a charge upon this last position of the enemy, which was gallantly made at the double-quick, the enemy breaking in confusion to the rear, escaping from the timber into the open fields beyond. In this charge we captured a large number of prisoners, including several officers, among them General Archer, who was taken by Private Patrick Maloney, of Company G, of our regiment, and brought to me, to whom he surrendered his sword, which I passed over with the prisoners to Lieut. D.B. Dailey, acting aide-de-camp on the brigade staff. I regret to say that this gallant soldier (Private Maloney) was killed in action later in the day. (1)

The Herbst Woods, the terrain through which the Second Wisconsin fought on the first day at Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Willoughby Run, across which Patrick Maloney and other members of the Second Wisconsin advanced on their way to capturing Brigadier-General Archer (Damian Shiels)

Today, beyond his heroics on the field, we know very little about the origins, emigration or life of Patrick Maloney and his family. We know somewhat more about his compatriot Dennis Dailey, who had taken charge of Archer’s sword. He would be involved in more trials and tribulations on 1st July, as the survivors of the 2nd Wisconsin retreated through the town of Gettysburg towards Cemetery Hill. He was among those men, who included Colonel Morrow of the Iron Brigade’s 24th Michigan, who took refuge in the home of Mary McAllister near the Christ Lutheran Church. She remembered the Galway man in her home:

There was a young Irishman in there, too. His name was Dennis Burke Dailey, 2nd Wisconsin. He was so mad when he found what a trap they were in. He leaned out of the kitchen window and saw the bayonets of the rebels bristling in the alley and in the garden. I said, “There is no escape there.” I opened the kitchen door and they were tearing the fence down with their bayonets. This young Irishman says “I am not going to be taken prisoner, Colonel!” and he says to me “Where can I hide?” I said, “I don’t know, but you can go upstairs.” “No,” he said, “but I will go up the chimney.” “You will not,” said the Colonel. “You must not endanger this family.” So he came back. He was so mad he gritted his teeth. Then he says to me “Take this sword, and keep it at all hazards. This is Gen. Archer’s sword. He surrendered it to me. I will come back for it.” I ran to the kitchen, got some wood and threw some sticks on top of it…Col. Morrow says to me “Take my diary. I do not want them to get it.” I did not know where to put it, so I opened my dress and put it in my dress. He said, “That’s the place, they will not get it there.” Then all those wounded men crowded around and gave me their addresses. Then this Irishman, he belonged to the 2nd Wisconsin, said, “Here is my pocketbook, I wish you would keep it.” Afterward I did not remember what I did with it, but what I did was to pull the little red cupboard away and put it back of that… Then there came a pounding on the door. Col. Morrow said, “You must open the door. They know we are in here and they will break it.”…That Irishman, he was so stubborn…He stood back so very solemn. Then they took him prisoner. He asked them to let him come back into the house. Then he said to us “Give me apiece of bread.” Martha said, “I have just one piece and that is not good.” He said, “It don’t make any difference. I must have it. I have not had anything to eat for 24 hours.” Then the rebels took him. (2)

The monument marking the deathspot of Major-General John Reynolds, Commander of the First Corps at Gettysburg. He fell at the edge of Herbst’s Woods, as the Second Wisconsin and others plunged towards the Confederates (Damian Shiels)

The marker to Archer’s Confederate Brigade in the Herbst Woods at Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Born around 1840, Dennis Dailey and his family had emigrated when he was six-years-old, settling in Ohio where he was educated at Antioch College. The Galwegian survived his Gettysburg captivity and later went on to serve in the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, performing notable service at engagements such as the Weldon Railroad, where he was wounded. He ended the conflict a brevet Lieutenant-Colonel. He had an active and successful post-war career; in 1867 he settled in Council Bluffs, Iowa where he became a criminal lawyer and served as District Attorney. He passed away in Council Bluffs in 1898 where he is buried in Walnut Hill Cemetery (you can read his obituary here and see his grave here). (3)

Looking west from the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary towards Herbst Woods, the ground on which the Second Wisconsin fought on Gettysburg’s first day (Damian Shiels)

As with nearly every unit in the Army of the Potomac, there were Irish-American families at home who waited anxiously for news of the 2nd Wisconsin. One were the Brennans in Vermont. Mary Brennan’s son Michael had worked on a farm in Rutland County, Vermont during much of the 1850s, before striking out west in the winter of 1856-7 with some friends. He was still there when war came, and he enlisted in Company B of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry in La Crosse on 13th February 1862. He continued to financially support his mother. One of the letters he wrote home (addressed to his brother) came on 18th March 1863, just over three-months before Gettysburg. The patriotic soldier was optimistic about the future despite the low numbers of men left in the unit:

Camp near Bellplain VA

March 18th 63

Dear Brother and mother i take this oppertunity of writing these few lines to you and let you know that i have changed my location since i last wrote you and am now with my reg. i came hear yesterday and am well thank god as i expected to be at this time the boyes are all in good fiting trim never better what their is of them.

we had 80 men when i left the reg officers and all now their is only 25 their is 12 deserted this winter the rest have been shot died of wounds and sickness and so on but we have comfortable quarters and good grube and things look livley and active hear instead of the army being demorlised it is quite the reverse if i have my health i had rather be hear than any place i have been in hospitall but we will have active times before long i expect

i wrote severil letters to you from the convalsent camp and recived no answer but that was very bad about the maills coming regalar

William Obrin told me[he] heard from you regalar i have not got one dollar of my regelar pay since i got a few dollars extra pay for work but not anough hardly to keep me in tobaco at the prices we have to pay now. i am in hopes that i will get it by the first of next month if the reg is paid by that time which i hope in god it will. But it may be so that i cant get it when i was not hear to be mustered the last of febuary if i was hear and mustered for the roll their would be no troble when the reg is paid but i supose the paymaster can do as he feels about it. But i shall do the best i can to get it and when i do you shall get the most of it with the help of god. I know that you must stand in need of it all winter but god knows i could not helpe it i tride my best to get it but could not.

i want you to write to me as soon as you get this and direct as you did when i was with the reg before and then i shall be purty shure to get it give my love to mother and all frinds

I got a letter from philip the other day he is well and down at [illegible]

No more at present

from yours truley

Michael Brennan

Michael did eventually get paid, and sent his mother $30 via Adams Express on 27th April. A little over two-months afterwards he was with the 2nd Wisconsin on Gettysburg’s first day’s battlefield, where he was destined to be among the dead. His mother would include proof of his last remittance to her in a pension application as she sought to secure support based on his service. (4)

The Adams Express receipt from April 1863, the last remittance Michael Brennan sent to his mother prior to his death at Gettysburg (NARA/Fold3)

The 2nd Wisconsin Infantry is another example of a unit that can be examined to learn something of the Irish experience of the American Civil War (for the story of another Irishmen in this regiment, who beat the odds to survive First Bull Run, see here). I hope to look at other elements of Irish participation in the Iron Brigade (particularly that of the 24th Michigan) and other non-ethnic Irish units at Gettysburg in future posts, incorporating some of the images I took on my recent visit to the battlefield.

The Lutheran Seminary as seen from neat the edge of Herbst Woods, ground traversed and fought over by the Second Wisconsin on the first day at Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Hartwig 2005: 169, Official Records: 274; Roster of Wisconsin Volunteers: 366; (2) Mary McAllister Memoir; (3) Wisconsin Historical Society; (4) Michael Brennan Mother’s Pension File;

References & Further Reading

WC34622 Widow’s Certificate of Mary Brennan, Dependent Mother of Michael Brennan, Company B, Second Wisconsin Infantry.

Hartwig, D. Scott 2005. “I Have Never Seen the Like Before” Herbst Woods, July 1, 1863.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 27, Part 1. Report of Maj. John Mansfield, Second Wisconsin Infantry, 273-275.

Wisconsin State Legislature 1886. Roster of Wisconsin Volunteers, War of the the Rebellion, 1861-1865, Volume 1.

Adams County Historical Society. Mary McAllister Memoir. Transcription by Ginny Gage accessed via the Gettysburg Discussion Group.

Wisconsin Historical Society. Dailey, Lt. Col. Dennis B. (1840-1898).

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, Galway, Wisconsin Tagged: Galway Diaspora, General Archer, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish in Vermont, Irish in Wisconsin, Iron Brigade at Gettysburg, Second Wisconsin Infantry

November 2, 2016

‘Pro Patria Mori’: The 94th New York Memorial & the Irish of Oak Ridge, Gettysburg

I have just returned from a visit to the Gettysburg battlefield, a journey that will be the subject of a number of posts over the coming weeks and months. While there I had the opportunity to stay in the wonderful Doubleday Inn, which is located on Oak Ridge, part of the first day’s battlefield. The hospitality of Christine, Todd and Cooper while we were there helped to make a memorable few days even better. Each morning I looked from the door of the inn at the monument and flank markers of the 94th New York Infantry, situated directly across the road, and each morning I took the opportunity to spend a few moments there. I wondered about the experiences of the Irishmen in that unit, who went through the horrors of battle only yards from where I now slept. In this post, I tell part of the stories of two of them, who more than 150 years ago experienced Oak Ridge at its worst.

The Doubleday Inn on Doubleday Avenue, Oak Ridge, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

James Dolan was almost 40-years-old by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg. He had enlisted from Rochester’s Fifth Ward in December 1861, becoming a private in the 105th New York Infantry. The iron moulder had married fellow Irish-emigrant Mary Sullivan in Rochester on 9th October 1842; in 1860 they lived with their 17-year-old son Michael, a gas-fitter, 13-year-old Julia, 10 year-old Eliza and 4-year-old James at 40 Hand Street. They were not well enough-off that Mary did not have to supplement the household income, and she worked as a seamstress. James had seen some hard-fighting with the 105th in the early part of the war, and in March 1863 he and his remaining Rochester comrades were consolidated into five companies and transferred to the 94th New York. It was as a soldier in Company G of that regiment that he marched onto Oak Ridge on 1st July 1863. There is little doubt that he should never have been there. Just prior to the commencement of the Gettysburg Campaign, James was suffering severely from diarrhoea and ‘camp fever’ at the regimental camp in Aquia Creek, Virginia. Although he appeared to recover, the arduous march in pursuit of Lee’s Army in June caused a major relapse of his illness. On the 29th June, as the regiment arrived in Emmitsburg, Maryland from Frederick, James’s Captain ordered the Irishman into an ambulance and told him to report to the regimental surgeon, David Chamberlain. Chamberlain was fatalistic about what he saw. In his analysis, James’s ‘constitution was broken and he was hopelessly used up by reason of his exposure and service.’ Not only that, but in his assessment Chamberlain ‘did not expect he [Dolan] would live but a few hours and was much surprised the next day [30th June] to see him alive.’ By any measure, James Dolan should not have been in the ranks at Oak Ridge. Indeed, his very presence there was in defiance of the odds, with his own regimental surgeon considering him to be at death’s door. But James Dolan does not appear to have been the type of man to let his comrades down, particularly when he knew a fight was coming. (1)

The 94th New York Infantry Memorial, Oak Ridge, Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Something of the measure of James Dolan can be gleaned from what his officers said about him. After Gettysburg, his Captain, John McMahon (a native of Co. Cork, later Colonel of the 188th New York and Brevet Brigadier-General), recalled how ‘Dolan refused to leave the ranks and kept on with the regiment.’ McMahon was among the captured at Gettysburg, but in his estimation Dolan ‘was as good a soldier as ever served.’ His First Lieutenant, Isaac Doolittle, felt that he ‘was as good a soldier as ever left the City of Rochester.’ His determination to join his regiment on the field of battle on 1st July 1863 certainly suggest he was a fine serviceman. What became of him? Private William F. Dart was with James on Oak Ridge:

…he received a gunshot in the hand at Gettysburg…[Dart]…was in the same front rank with…Dolan when he was so wounded and while assisting…Dolan to the rear… he was again shot through the right shoulder by the enemy..[Dart]…got him (with assistance) to the rear of the Cemetery at…Gettysburg where he left him…[and] rejoined his company…he did not see…Dolan again until the until the fourth…he was then in a barn near said Cemetery…Dolan with others of the wounded were sent to Philadelphia on the night of the fourth… (2)

James Dolan was admitted to Saterlee Military Hospital in Philadelphia on 5th July. He seemed to recover quickly from his injuries, and on the 15th July he applied for, and was granted, a five day furlough to go and see his family. He never made it. Within days his body was returned to the hospital, his cause of death unspecified. Presumably he had succumbed to a combination of his original illness and his Gettysburg wounds. On 20th July a telegram was sent to his brother informing him of the fateful news. (3)

The telegram sent to James Dolan’s brother informing him of his death in Philadelphia (National Archives/Fold3)

Another Irishman who marched onto Oak Ridge on 1st July was James Ratigan of Company E. In his case, we know precisely where in Ireland he was from. His parents Thomas Ratigan and Mary Kelly had married in Kilcormick, Co. Longford on 15th March 1821. Mary had died in Ireland in September 1839, and almost immediately afterwards Thomas emigrated to New York. Among those he had in tow was his infant son James. As was so often the case, Thomas Ratigan had not emigrated in isolation– he had gone to be with fellow immigrants from Co. Longford. They had settled in and around the town of Scriba, Oswego County, and it was there that Thomas started a new life, running a 20 acre farm. As the years passed, rheumatism impacted Thomas’s ability to work the land, and he increasingly relied on James to help him with it. That ended in February 1862, when 24-year-old James enlisted at Sackett’s Harbor. We know that the young man retained a strong interest in Ireland, as did many men in the 94th Infantry. Previous work I have carried out on those men who donated portions of their army wages to be sent to the relief of the poor in Ireland in 1863 (see here), only weeks before Gettysburg, identified a number of soldiers of the 94th New York, including James. The names, contributions and ultimate fates of those who contributed are available in Table 1 below. Aside from James, a number of other donors from the 94th were killed or wounded on the field at Gettysburg:

Allen, Thomas

94th New York

$1.00

June 1864 (P.O.W.)

Ball, John

94th New York

$1.00

Five Forks (K.I.A.)

Barry, John

94th New York

$1.00

Bates, Jacob

94th New York

$1.00

Boyce, Richard

94th New York

$1.00

Boyne, Richard

94th New York

$2.00

Five Forks (K.I.A.)

Brennan, Edward

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

Burns, James H.

94th New York

$1.00

Calvin, John

94th New York

$0.50

Disability

Canty, James

94th New York

$1.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

Carey, Calvin G.

94th New York

$1.00

Gettysburg (W.)

Carroll, Peter

94th New York

$1.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.), Salisbury (D.D.)

Chamberlain, David C.

94th New York

$2.00

Clemens, William

94th New York

$0.50

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

Congor, Edward

94th New York

$0.50

Connors, Patrick

94th New York

$1.00

Curtain, Jefferson

94th New York

$2.00

Coyle, Patrick

94th New York

$2.00

Petersburg (W.)

Croaker, Albert

94th New York

$2.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

Creelie, Thomas

94th New York

$1.00

Delaney, Michael

94th New York

$1.00

Donohue, Michael

94th New York

$1.00

Donovan, William

94th New York

$2.00

Deserted

Fitzgerald, John R.

94th New York

$5.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.), Point Lookout (D.)

French, George

94th New York

$5.00

1864 (P.O.W.), Five Forks (K.I.A.)

Friend, A

94th New York

$1.00

Galvin, Michael

94th New York

$1.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

Graham, Owen

94th New York

$1.00

Haggerty, John

94th New York

$1.00

Hayes, E.

94th New York

$1.00

Heary, Matthew

94th New York

$1.00

Hickey, M.

94th New York

$5.00

Howell, John

94th New York

$1.00

Jacobs, Michael

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

Johnson, John

94th New York

$3.00

Court-martialled

Kerns, James

94th New York

$2.00

King, John

94th New York

$2.00

Kinsella, William

94th New York

$1.00

Gettysburg (W.)

Mackey, Alexander

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

Mangan, James

94th New York

$1.00

Mapey, William

94th New York

$1.00

McArdle, James

94th New York

$1.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

McCullagh, P.

94th New York

$1.00

McDonald, Robert

94th New York

$1.00

Weldon Railroad (P.O.W.)

McGlinn, Francis

94th New York

$1.00

McGuire, John

94th New York

$1.00

McKee, Robert

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

McKendry, William

94th New York

$2.00

Gettysburg (K.I.A.)

McKenna, Charles

94th New York

$2.00

Gettysburg (W.)

McLarney, John

94th New York

$1.00

June 1864 (W.)

McMahon, John

94th New York

$10.00

Gettysburg (P.O.W.)

McMaster, Charles

94th New York

$1.00

Petersburg (W.)

McMackin, James

94th New York

$1.00

McQuickin, H.

94th New York

$1.00

Mulligan, Patrick

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

Nichols, Alexander

94th New York

$0.50

O’Donnell, John

94th New York

$1.00

O’Donoghue, Florence

94th New York

$1.00

Pringle, George

94th New York

$1.00

Rattigan, James

94th New York

$1.00

Gettysburg (K.I.A.)

Rogers, J.H.

94th New York

$1.00

Rooney, James

94th New York

$1.00

Sard, Thomas P.

94th New York

$1.00

Slattery, Michael

94th New York

$2.00

Weldon Railroad (W.), Disability

Sullivan, John

94th New York

$1.00

Sullivan, Patrick

94th New York

$2.00

Sunman, Thomas

94th New York

$1.00

Taylor, Steadman

94th New York

$1.00

Thrasher, George

94th New York

$1.00

Deserted

Turim, Daniel

94th New York

$1.00

Whalen, Daniel

94th New York

$1.00

Winn, Patrick

94th New York

$1.00

Table 1. 94th New York donors in 1863 for the Relief of the Poor of Ireland (Damian Shiels) (4)

Looking south along Doubleday Avenue on Oak Ridge and the memorials that mark the First Corps line. The 94th New York memorial is located just before the woods (Damian Shiels)

No details survive as to how James Ratigan met his death at Gettysburg, but it likely occurred not far from the regimental memorial on Oak Ridge. Unsurprisingly, his loss left his father in dire straights. He turned to the community of Longford emigrants in Oswego to help him secure his pension; people like Michael Connor, who testified in 1870 that he had lived in Scriba for 34 years and had known both Thomas Ratigan and his wife Mary in Longford, and Elizabeth Fineran, who in 1868 related that she had lived in Oswego County for 30 years but had known the Ratigans for 40 years, having emigrated from Longford two years before them, in 1838. By so doing they revealed the Ratigan’s reasons for selecting Oswego County as their new home, a decision which ultimately led James to Oak Ridge on 1 July 1863, some 23-years after his departure from Ireland. (5)

Both James Dolan’s wife and James Ratigan’s father received Federal pensions based on their service, from which much of the above detail has been gleaned. They demonstrate the impacts on just two Irishmen and their families of the fighting on Oak Ridge- just two experiences among the hundreds that affected Irish emigrants in the fields of Gettysburg, spread through innumerable units. They are a further example to us that if we want to fully explore the Irish experience resulting from engagements like Gettysburg, then we must look beyond just ethnic Irish units such as the Irish Brigade and the 69th Pennsylvania, and seek to uncover the stories of the majority- those who did not march into history beneath a green banner. (6)

The official New York Roll of Honor records the names of fifteen men of the 94th New York Infantry who died as a result of the fighting at Gettysburg. Aside from James Dolan and James Ratigan, the names of a number of others suggest they were Irish-American. The full list is as follows:

Company A: Sergeant John Stratton

Company B: Private Albert E. Dickson

Company C: Sergeant Henry Saunders, Private William L. McIntyre

Company D: Private Michael Donohue, Private John Glaire Jr.

Company E: Private William McKendry, Private James Ratigan

Company F: Sergeant Lawrence Hennessy

Company G: Private James Dolan

Company H: Corporal James Cooney, Private William Bastian, Private Lemon T. Miner

Company K: Private Benzette Fuller, Private William H. Wydner (7)

At the 94th New York Memorial, erected in 1888- the first memorial I visited at the Gettysburg battlefield (Damian Shiels)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) James Dolan Pension File, 1860 Federal Census; (2) James Dolan Pension File; (3) Ibid. (4) Thomas Ratigan Pension File, Donors to the Irish Relief Fund; (5) Thomas Ratigan Pension File; (6) Ibid.; (7) New York Monuments Commission 1902: 223;

References & Further Reading

WC140100 Certificate of Thomas Ratigan, Dependent Father of James Ratigan, Company E, 94th New York Infantry.

WC143641 Certificate of Mary Dolan, Widow of James Dolan, Company G, 94th New York Infantry.

1860 United States Federal Census.

New York Monuments Commission 1902. Final Report on the Battlefield New York at Gettysburg, Volume 1.

Gettysburg National Military Park.

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page.

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, Longford, New York Tagged: 94th New York Infantry, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish in New York, Irish in Oswego, Irish in Rochester, Longford Emigrants, National Archives Widows Pensions

October 30, 2016

The Forgotten Irish Brought to Life on RTE Radio 1

The first publicity for my new book The Forgotten Irish came recently on the RTE Radio 1’s The History Show. The programme featured extracts from four of the stories, with actors reading from a number of the letters. It is always great to hear these letters brought to life in this way– particularly as one gets a feel for the regional accents of the individuals involved. This part of the show has now been podcast, and you can listen to it by clicking here.

Filed under: Media Tagged: American Civil War Irish, History Press Ireland, Irish American Civil War, Myles Dungan, RTE Radio 1, The Forgotten Irish, The History Show, Widow's Pension Files

October 8, 2016

In the Ghostly Footsteps of the Gettysburg Irish

My posts have been less frequent than normal of late due to a range of book and conference commitments, so apologies to readers for the longer than normal gap! I will shortly be heading to the United States for the first time in a couple of years, taking in some locations relating to the Irish experience in New York and Pennsylvania, as well as some of those associated with the Revolutionary War. The highlight though will be my first visit to the Gettysburg battlefield. As a result, I have been reviewing some of my writing on the Irish and Gettysburg over the years, with a view to connecting some of these stories to place when I am at the site.

The image of the Confederate Sharpshooter taken by Irish photographer Timothy O’Sullivan at the Gettysburg Battlefield, Pennsylvania in July 1863

When we think about the Irish at Gettysburg, we tend to concentrate on the Irish Brigade and their experiences in the Wheatfield. However, the much-reduced brigade represented just a tiny proportion of the Irish on the field. I am looking forward to seeing the sites related not only to them, but to the Irish who fought and died serving in multiple units across the three-day battle. Any accounts one reads of Gettysburg demonstrates the large numbers of Irish sprinkled throughout the units on both sides (which I have written about here). I will be thinking of men like Private Patrick Maloney of the 2nd Wisconsin, who captured Brigadier-General James J. Archer on the first day’s fighting– the first Army of Northern Virginia General captured since Lee had taken command– only to die himself later in the day. I will be thinking of the experiences of other Irishmen who wrote about their time at Gettysburg– men like James Sullivan of the 6th Wisconsin, and Thomas Galwey of the 8th Ohio. I will be thinking particularly of those whom I have uncovered in the pension files, and whose letters I transcribed. These are men like Hugh McGraw from Co. Down, a Lieutenant in the 140th New York Infantry, who wrote his last letter home to his mother in May 1863:

[I] was rather grieved and disappointed…to find that your health was rather poor, but I hope ere this reaches you that you will have recovered your former strength, and that God in his infinite mercy will be around you and bring you safe through your sickness… Knowing that I am necessarily absent and that there is none of the other members of the family near enough to pay any attention to you but I trust you will be able to get along…till I can again seek shelter under the old roof. If God in his divine Providence has so willed it that I again return to my home.

Buster Kilrain (Kevin Conway) engaging the Confederate on Little Round Top in Ron Maxwell’s ‘Gettysburg’. Kilrain is fictional, but one ‘old bachelor’ Irishman did fight with the 20th Maine at Gettysburg– Tommy Welch (Image: Dudster32)

Hugh fell mortally wounded as the 140th played a vital role in securing Little Round Top on the second day, together with his regimental Colonel, Paddy O’Rorke from Co. Cavan.

Although the Irish Brigade receive the most attention, arguably it was the 69th Pennsylvania who provided the most vital service to the cause of Union of any of the ethnic Irish units at Gettysburg. I have explored the stories of many of them who fell defending the stone wall in the face of the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble assault on the third day’s fighting. The letters of some of those who died have provided me with an insight into the personalities of some who breathed their last in that savage struggle. One was Patrick Carney, of Fintona, Co. Tyrone. A little over a year earlier he had seen the aftermath of battle for the first time at Fair Oaks:

Dear mother we were in that battle of Saturday and Sunday last, we were in the reserve and we were not in action we are under arms every minute in the day and night. I never saw in my life time the sight I saw. Our Company was sent out yesterday afternoon to bury the dead and we were out 2 hours and we buried 46 Rebels. We are encamped on the battle ground.

A depiction of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. One of the other 69th Pennsylvania men who repulsed it was Charly Gallagher, who later returned to Co. Donegal and recorded himself as a veteran of the regiment in the Irish 1901 Census (Library of Congress)

After Pickett’s Charge, Patrick was among those who now relied on others to bury them as he had once done himself. Another to die beside Patrick Carney with the 69th was Thomas Diver. A year earlier, he had written to his mother, with a request that, in light of his fate, is filled with extreme poignancy, as the self-conscious youth sought to look his best:

I would like you to send a couple of grey flannel overshirts and if you can afford a pair of strong legged boots, not expensive ones, also two bottle of the Balm of a Thousand Flowers for to take off the pimples on my face. It is only 15 cents a bottle at Petersons Book Store. Dear Mother I wish you would get your daugerrotype taken for me, the one I got is broke in my knapsack and I have only got the glass that it was taken on without the case, a 25 cent one will do.

Monument of the 73rd New York Infantry at Gettysburg, erected in 1897 and depicting a Union infantryman and a fireman side by side. Many Irishmen fought in this unit (Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg)

Another of the 69th Pennsylvania was officer Charles McAnally from Derry, who wrote to the wife of his friend, Louth native James Hand, who also died facing Pickett’s Charge at the stone wall on 3rd July:

It is a painfull task for me to communicate the sad fate of your husband (my own comrade)…he received a ball through the breast & one through the heart & never spoke after. I was in command of the skirmishers about one mile to the front & every inch of the ground was well contested untill I reached our Regt. The Rebels made the attack in 3 lines of Battle, as soon as I reached our line I met James he ran & met me with a canteen of watter. I was near palayed [played] he said I was foolish [I] dident let them come at once that the ‘ol 69th was waiting for them. I threw off my coat & in 2 minuets we were at it hand to hand. They charged on us twice & we repulsed them they then tryed the Regt on our right & drove them, which caused us to swing back our right, then we charged them on their left flank & in the charge James fell, may the Lord have mercy on his soul. He never flinched from his post & was loved by all who knew him.

Survivors of the 69th Pennsylvania at their old position in Gettysburg in 1887

Another aspect of Gettysburg I have spent time on is in exploring the impact of the death of loved ones on dozens of Irish families. The letters written to some, informing them of the terrible news, still survive. One relates to John and Mary Clark, who were married in Co. Westmeath in 1848. John was in the 65th New York Infantry at Gettysburg on 3rd July. In the letter informing Mary that John had been mortally wounded, she was spared no detail:

It is with regret I announce to you that your husband was killed in the Battle of Gettysburg the 3rd of July at about 11 O’clock. He lingered for about 4 hours when death put an end to his sufferings. He was universally beloved in the regiment, but more particularly in our company where he was better known. By his death the regiment loses the services of one whose place it will be difficult to fill. In passing this tribute to his memory I but re-echo the sentiments of the entire command. I sincerely sympathize with you in the irreparable loss you have sustained, whereby you have lost a kind husband, and your children an affectionate father. May his soul rest in peace…Your husband was laying on his back calmly talking of the “Union” when a fragment of a shell struck him nearly taking both legs off.

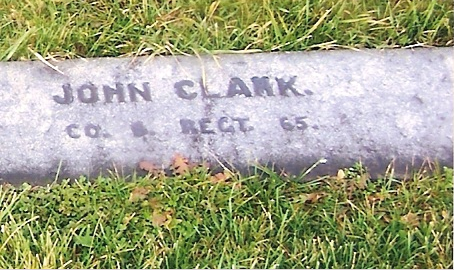

John Clark’s memorial in Gettysburg National Cemetery (Photo: Pat Callahan, Find A Grave)

Mary McKenna’s husband John was in the 70th New York Infantry, Excelsior Brigade on 2nd July. When his comrades buried him, they placed a photograph of Mary in the grave with him:

…it pains me to write you these few lines but brace yourself for the worst your Husband was killed on the battle feild of Gettyisburgh on the second day of July he died a brave man and was nobly fighting for his country and its rights you must bear up with his loss as well as you can for there is many left in the same way may God guard and protect you and your little ones through this world of battles as I am in command of this company I had to open seven letters so as to see where to direct this letter to you..Your likeness was buried with him your husband had nothing with him of any value no money or any such thing and soon as we get into camp I will see that his effects are made out and the papers sent on to you your husband was buried on the battle feild…

The Excelsior Brigade Monument at Gettysburg, a bridge with large numbers of Irishmen in the ranks (Photo: Cory Hartman)

Gettysburg also became the final resting place of many Irish step-migrants, who had travelled to the United States following extended stays in other countries, such as England. Among them are men like Irishman Timothy Kearns, who married Maria Pelham at St. Anthony’s in Liverpool in 1854 and was killed in action with the 71st New York Infantry on 2nd July, and John Curran, whose Irish parents had married in Liverpool in 1841, before the family emigrated after his father’s death in 1855. John served in 73rd New York Infantry, and was mortally wounded on 2nd July.

The 42nd New York ‘Tammany Regiment’ memorial at Gettysburg. Of the 182 men who contributed to the Irish Relief Fund only two months before, 13 would die as a result of this battle (Photo: J. Stephen Conn)

Then there are the men who only weeks before Gettysburg had donated funds to help the poor back in Ireland, despite the perils they themselves faced. Of those who have identified who contributed, many breathed their last in Pennsylvania that July. Men like Thomas Banon, Daniel Barrett, William Byrne, Michael Cuddy, James Cullen, Thomas Curly, William Flinn, Thomas James, Hugh Murphy, Daniel O’Shea, John Smith, Christopher Stone, Peter West, all of the 42nd New York, Denis Brady and Charles Neeson of the 15th Independent New York Light Battery, Patrick Kenny, Patrick McGeehan, John O’Brien and Michael Sheehan of the 63rd New York, John Ferry, J. McBride and John Small of the 88th New York, James Hatton of the 28th Massachusetts, William McKendry of the 94th Pennsylvania, James Rattigan of the 94th New York. Many more were wounded or captured.

John Lonergan Memorial, Carrick-On-Suir, Co. Tipperary. Lonergan received the Medal of Honor for actions at Gettysburg (Damian Shiels)

Of course, many of the Irish who fought for the Union at Gettysburg would later receive the Medal of Honor for their actions there. The variance in their units once again demonstrates that the Irish experience spreads far beyond ethnic Irish units; Hugh Carey of the 82nd Pennsylvania, Christopher Flynn of the 14th Connecticut, Thomas Horan of the 72nd New York, John Lonergan of the 13th Vermont, Bernard McCarren of the 1st Delaware, John Robinson of the 19th Massachusetts.

Though the fast majority of the Irish at Gettysburg fought in Union blue, there were nonetheless many in Confederate gray. Undoubtedly the most famous was Willie Mitchel, the son of Irish nationalist John Mitchel, who died with many others from the 1st Virginia while participating in Pickett’s Charge. Another with him was John Dooley, the son of a Limerick family, who was wounded in that assault and subsequently wrote of his experiences.

The area of Pickett’s Charge, Gettysburg, where Willie Mitchel lost his life (Wikipedia)

The Irish also played a big role in memory at the battle, which I am interested in exploring. The 69th Pennsylvania veterans were there for the dedication of their brigade monument in 1887, where they shook hands with former Confederate foe at the stone wall in which they fought. The Irish Brigade are also remembered with a fine monument to their service, together with another of Father Corby, who famously provided conditional absolution to the unit before they went into action. I am looking forward as well to explore how Gettysburg became the key home of memorials for Army of Potomac units during the Civil War. Another I will visit will be that to the 9th Massachusetts Infantry, an Irish regiment that has long fascinated me. The 9th were barely engaged at Gettysburg; it was at Gaines’ Mill in 1862 and The Wilderness in 1864 that they laid all at the feet Union- yet their memorial is not on those fields, it is at Gettysburg.

Father Corby at Gettysburg (Memoirs of Chaplain Life)

Perhaps most of all, as I try to do at all the Civil War sites I get the opportunity to visit, I will spend some time in the National Cemetery, looking at the many graves of those Irish-born and of Irish-descent who rest there. I hope to share some of the images of their headstones with you on the site in due course, and perhaps explore some of their stories.

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg Tagged: 69th Pennsylvania, Excelsior Brigade, Gettysburg National Battlefield Park, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish Brigade, Irish in America, Widow's Pension Files

September 27, 2016

Podcast: The Forgotten Irish– Revealing the Personal Stories of 19th Century Emigrants

On 18th August last I was privileged to return to the National Library of Ireland in Dublin to deliver one of the Summer lunchtime talks at the institution, which are organised by Eneclann and the Ancestor Network. The title of the talk was The Forgotten Irish: Revealing the Personal Stories of 19th Century Emigrants through American Civil War Pension Files. The 40 minute lecture looked briefly at the Irish in the American Civil War, before discussing the origins and contents of the U.S. pension files and finally going through a number of examples to demonstrate how they can be used to recreate social histories of individual emigrant family groups. The latter elements will also form part of my forthcoming book on the topic. The event was one of the small number of my talks that have been podcast, and I’m pleased to say it has just been made available via the Irish Family History Centre. If you are interested in hearing what I had to say, you can do so by clicking here. As ever, I am always interested in readers thoughts!

Filed under: National Library of Ireland, Podcast Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Irish in America, National Library of Ireland, NLI Lunchtime Talks, The Forgotten Irish, US Pension Bureau

September 18, 2016

The Other Bermuda Triangle: Invasion attempts in Ireland, America, and Bermuda

There is some superb research being undertaken into elements of the Irish diaspora at present, both at home and abroad. The site has been fortunate to feature a number of guest posts in the past highlighting some of this scholarly research. I am delighted to be able to share a fascinating post prepared for the site by Jerome Devitt, a PhD Scholar at Trinity College, Dublin. Jerome has been working on British counterinsurgency in Ireland in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, and has recently carried out substantial work on the fascinating Fenian connections with Bermuda. Jerome recently published on this topic in the latest Éire-Ireland and here distills for us his findings, and how they connect to Fenians in the United States– many of whom were Civil War veterans.

Oftentimes the story of Irish and Irish-American revolutionary nationalists can seem relatively direct: 1st or 2nd generation Irish-American’s develop military expertise in America during the Civil War which they hope to now use for the ultimate freedom of Ireland, either by a direct naval expedition to Ireland or though dragging Britain into direct confrontation with the United States. This year’s 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Ridgeway and the Campobello ‘Fiasco’ has seen the geographic focus of Fenianism broaden to include invasions of Canada, most recently explored by Peter Vronsky.(1) This, however, is not the full story. Recent research has seen historians trying to come to a better understanding of Fenianism’s geo-strategic ambition. Scholars like Jill Bender, Richard Davis, and Máirtín Ó Catháin have cast their eye farther afield – as far as New Zealand and Australia, coming to the conclusion that Fenianism had a broader global and transnational reach than previously understood. (2)

My recent research follows this trend, but focuses on the tiny mid-Atlantic colony of Bermuda. Barely bigger than the Aran Islands (53km2), Bermuda had massive strategic significance, primarily due to the presence of the Royal Navy’s base, located on the conveniently named “Ireland Island” on the western tip of the colony. Its location, right in the middle of the ‘Atlantic Arc’ made it the only secure British landfall between the remnants of Britain’s remaining America colonies, half way between its other two naval bases in Halifax, Nova Scotia and English Harbour, Antigua. Take a look at the map below, (which is rotated to show West at the top) to see just how centrally located Bermuda was to transatlantic trade and naval activity:

Bermuda and the Atlantic Arc- click to enlarge (Jerome Devitt)

Links between Ireland and Bermuda

The first reason most Irish people had to be aware of Bermuda came through literature. Thomas Moore, the “Bard of Erin” and author of The Last Rose of Summer, had spent time in 1804 working for the Admiralty on the island and his poem This Little Fairy Isle became very well known (partly because of scandal associated with some marital infidelity!). Moore became known as the “Unofficial Poet Laureate of Bermuda, but this was just the tip of the iceberg.

Thomas Moore Stature in Bermuda (Jerome Devitt)

Irish priests who served the Archdiocese of Halifax, Nova Scotia, formed the backbone of the Island’s Roman Catholic priests throughout the century, and numerous colonial administrators were rotated around the empire including Ireland and Bermuda. Perhaps the strongest link between the islands, however, came through the colonial penal system. The prison hulks that lay off the coast housed up to 1,500 transported criminals, almost 800 of whom were Irish and had been sent there during the famine. Their “lower stature and childish appearance,” evoked such pity from the Island’s Governor, Charles Elliot, that he separated them from other convicts and went as far as to find them apprenticeships! A prefabricated prison intended for Bermuda even ended up on Spike Island in Cork harbour! The most famous convict on the hulks, however, was John Mitchel, who was arrested in the build up to the 1848 Young Ireland Rising.

Prison Hulks in Bermuda (Jerome Devitt)

Plot #1

No sooner had Mitchel arrived at Bermuda in June 1848, however, than the Irish Republican Union was hatching plans from New York to liberate him from captivity. They hoped to use 2,000 veterans from the recent Mexican-American War to either liberate him, or distract the Royal Navy’s North Atlantic Squadron to allow for a landing in Ireland. Mitchel’s understanding of what was happening was limited, and was described in his subsequently published Jail Journal. Informants rushed to the British Consuls along the eastern coast of America who sprung into action and relied on the best British tactic of the time “Naval Deterrence”. Ships from Halifax were dispatched to Bermuda and off the coast of New York to “let it be generally known” that British Authorities were aware of the plot. This proved enough to put off the potential plotters! If you’d like to find out more about how the Royal Navy prepared for possible American landings in Ireland in 1848 click here.

Is Bermuda to be Captured? (Jerome Devitt)

Plot #2

In order to try and distract British attention from the Campobello expedition in April 1866, the Fenians, through one of their best known members – Bernard Doran Killian, leaked a plan to the authorities stating that they intended to invade Bermuda with the cutting edge technology of “Ironclad steamers” which had risen to prominence during the USCW. One consular report shows the scale of the plan, which now must be viewed as little more than a useful piece of ‘counter-intelligence’:

On Thursday morning of this week there appeared in the New York

Herald, Daily News, and World statements or detail of the secret sailing

at midnight on Monday of three ironclad [sic] with 3,000 desperadoes

on board; and at the same time on Tuesday night, of three

fast-sailing propellers with a reinforcement of 2,500 veteran soldiers,

all under the command of Lieutenant General Killian.

Most newspapers, both in America and Ireland eventually dismissed the seemingly foolish plan as the “Fenian Bermuda Hoax”, but inadvertently, the problem nearly became very real when the British Army sent its 61st Regiment (which had been infiltrated by the IRB in Ireland) to Bermuda later in the year to strengthen its defences! The disaster in Campobello rendered this plot dead in the water, but a definite pattern began to be established, whereby Bermuda was growing in importance in the minds of the Fenians.

HM Floating Dock, Bermuda (Jerome Devitt)

Plot #3

After eventually escaping captivity in Australia, Mitchel went on to broadcast that “a patriotic organization of Irishmen had at all times a clear right to attack English power, either in Canada or anywhere else” and the revolutionaries of the 1880s aimed to do just that in Bermuda. (3) Possibly the most impressive and significant piece of imperial infrastructure in the Atlantic was Bermuda’s world famous HM Floating Dock, which became a target for O’Donovan Rossa’s ‘Dynamiters’ in 1881/2. The dock had a displacement of 8,300 tons, an overall length of 381 feet, a width of 123 feet and was capable of lifting a 10,000-ton vessel clear out of the water for repairs, enough for all but the largest of the Royal Navy’s capital ships that were developed in the thirty years of the dock’s nearly continuous use from 1869. Information came to Consul Clipperton in New York from numerous sources stating that Edward O’Donnell and Thomas Mooney (already famous from the ‘Mansion House’ dynamite attack in London) were being dispatched to Bermuda to blow up the dock, causing a dramatic reinvigoration of the Island’s defences, and the mobilization of virtually the entire civil and military population to be on alert for potential attackers. Here Ireland and Bermuda were linked through an Atlantic-wide intelligence system as the map below illustrates.

Tracking the Dynamite Intelligence (Jerome Devitt)

What’s most interesting about this plot, however, is that it illustrates Irish involvement both within and in opposition to the British Empire. This is best illustrated by the fact that in 1882 Irish-Americans were attacking Bermuda, whose Lieutenant Governor was County Clare born Michael Laffan, who reported to a former Irish Lord Lieutenant in the Colonial Office (John Wodehouse, Earl of Kimberley – Irish Viceroy 1864-66), the island was garrisoned by the Royal Irish Rifles, who were in turn defending a naval base on Ireland Island, which was itself largely built by Irish convict labour!!! This, hopefully, demonstrates just how elaborate and complex Irish involvement in the British empire (and Bermuda in particular) was, and makes the simple reading of Irish-American Revolutionaries a little bit more interesting.

Jerome Devitt is a final year PhD Candidate in Trinity College, Dublin. His thesis, “Defending Ireland from the Irish”, examines British Counterinsurgency in Ireland in the immediate aftermath of the US Civil War. It focuses on British military institutions and their efforts to deter and suppress transatlantic Fenianism. He is a secondary school teacher living and working in King’s Hospital boarding school just outside Dublin.If you’d like to find out more about the connections between Ireland and Bermuda and significantly more detail on the plots of the US Civil War veterans and the reaction to the plots, click here to read my article in the recent edition of the journal Éire-Ireland.

References

(1) Peter Vronsky, Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion and the 1866 Battle That Made Canada (Toronto: Penguin Global, 2012).

(2) Jill Bender, ‘The “Piniana” Question: Irish Fenians and the New Zealand Wars’, in Ireland in an Imperial World: Citizenship, Opportunism, and Subversion, ed. Michael De Nie, Timothy McMahon, and Paul Townend (Palgrave Macmillan, Forthcoming); Richard Davis, ‘The Prince and the Fenians, Australasia 1868-9: Republican Conspiracy or Orange Opportunity?’, in The Black Hand of Republicanism: Fenianism in Modern Ireland, ed. Fearghal McGarry and James McConnel (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2009), 121–34; Máirtín Ó Catháin, ‘“The Black Hand of Irish Republicanism”? Transcontinental Fenianism and Theories of Global Terror’, in The Black Hand of Republicanism: Fenianism in Modern Ireland, ed. Fearghal McGarry and James McConnel (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2009), 135–48.

(3) New York Times, 2 February, 1867.

Filed under: Fenians, Guest Post Tagged: Dynamite Campaign, Fenians and Bermuda, HM Floating Dock, International Fenianism, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Bermuda, Jerome Devitt, Transnational Studies

September 9, 2016

‘All Abouth Home’: An Illiterate Emigrant’s Letters from America to Kerry in the 1850s

As I often reiterate, the greatest value of the widows’ and dependents’ Civil War Pension Files lies not in what they contain about the American Civil War, but in what they tell us about 19th century Irish emigrants and emigration. There are few finer examples of this than the file associated with Charles Greaney. The documents within it allow us to trace his origins in Ireland down to the laneway he likely grew up on, and the road on which he walked to work. They allow us to meet his family and friends, and learn how they interacted with each other in Ireland. His 1850s letters– after emigration– reveal the ties between east Kerry and Massachusetts, while the statements of others show the same connections between east Kerry and Chicago. In their words we can ‘see’ 19th century Kerry accents, and discover how entirely illiterate family groups could communicate across oceans.

Turf being taken home in Kerry at the turn of the 20th century. A scene that would have been familiar to Charles Greaney (Library of Congress)