Damian Shiels's Blog, page 26

March 25, 2017

Mapping Mainland Europe’s American Civil War Widows & Dependent Parents: An Online Resource

Over recent months I have been working on a major new resource for those interested in the emigrant experience of the American Civil War. It seeks to provide information on all the widows and dependents receiving American pensions outside the United States, based on those listed in the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll. The first element of this project has now been completed and is made available here. It deals with widows and dependent parents who were in receipt of monies on mainland Europe, principally as a result of a loved one’s service in the American Civil War. Future additions to the project will include the UK & Ireland, the Americas (excluding the United States) and the Rest of the World. Ultimately it will constitute a detailed freely accessible resource on all 1883 American military pensioners everywhere outside of the U.S. I am eager for this resource to be of maximum use to prospective researchers, and as such the excel files I have created for have been freely provided for download below. For ease of use I have also mapped the results, creating an interactive resource on Google Fusion Tables so that readers can spatially explore the pensioners in a European context and also with respect to the locations in the United States where their loved ones died. I would like readers feedback on this project, so if you have any suggestions for corrections, additions or improvements please let me know.

As outlined above, the baseline data for this project has come from the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll, which was created at the direction of Congress in order to ascertain the details of American military pensioners then in receipt of Federal monies. The list contained details on the pension certificate number, the pensioner name, their postal location, the reason for their pension, its monthly value, and the date from which it was approved (see Figure 1 below). As my principal area of interest is in dependent pensioners, I am only seeking to map them as part of this project- pensioned former servicemen have therefore been excluded. Having first exported the information from the List of Pensioners into an excel spreadsheet, I sought to identify gaps or errors in the data. This most commonly arises from mis-spelling of the pensioners name, mis-spelling of their postal address, and occasionally mis-assignation to an incorrect region. In order to increase the functionality and usefulness of the dataset, I next conducted extensive research in pension files, pension indexes, regimental muster rolls and regimental rosters to add three further layers of information, namely the name of the serviceman on whom the pension was based, his unit, and his fate. In addition I added grid-coordinates for both the location of the pensioner in their home country, and also the site associated with their loved one’s death. The results allow for a range of different types of analysis of the data, which allow us to both ask and formulate different questions about these pensioners.

[image error]

Figure 1. An extract from the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll, showing pensioners in the Baden Region of Germany (Click to enlarge)

In this first data and mapping instalment, I have covered all those pensioners listed on mainland Europe, together with those who were recorded as having ‘Unknown’ locations, the majority of whom were also from the 19th Century German States. Readers should be aware that the geography of Europe has changed substantially since the 1883 list was prepared, and as a result, the homes of pensioners which were once part of the German States or the Austro-Hungarian Empire now form part of different countries, and some have undergone an official name change.In some instances I have found information within pension files or through other research which have led me to correct or interpret information provided on the List of Pensioners, and users will be able to identify this in the data through the use of parentheses ().

It is my intention once this project is complete to use the dataset to explore many different facets of both the pensioner experience and the pension process itself, but with this initial tranche I wanted to briefly draw attention to a number of interesting points. Perhaps the most fascinating is the overwhelming concentration of mainland European pensioners in the central belt of the Continent, covering Switzerland and most significantly Germany (Figure 2). It is certainly no surprise that German pensioners dominate; Apthorp Gould in his 1869 Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers estimated that there were 176,817 Union volunteers of Germanic origin. When British and Irish servicemen are excluded, Apthorp Gould surmised that there were only 48,410 ‘other foreigners’ under Union arms. However, even given this overwhelming dominance, it is still a surprise that there is not more geographic variety in the pension distribution. We are left to ponder possible explanations for this. Perhaps more Germanic dependents returned home to Europe than those of other nations? However, if this was the primary explanation one might expect to see higher representation in other regions such as Scandinavia. Foreign dependent pensions often relied on strong communications being maintained between immigrants in the United States and their origin communities, so perhaps these ties were not as solid for many mainland European emigrants. However, it seems the most probable explanation lies with knowledge of, and access to, the pension process. Not only did those in Europe have to be aware that they were entitled to a pension, they also had to have access to both legal assistance and in many cases U.S. Consular assistance. Language barriers also undoubtedly proved a major stumbling block. In light of that, it is likely that many thousands of European dependents who were entitled to military pensions were either unaware of their entitlements, or unable to navigate the process which would allow them to claim their payments. (1)

[image error]

Figure 2. Breakdown of Mainland Europe Widows and Dependent Pensioners by Defined Region (Click image to enlarge)

Another way of looking at the information relates to examining the death locations of the men on whom the pensions were based. Figure 3 records this data, looking at each location among the mainland Europe group where place of death was identifiable, and which registered three or more dead.

[image error]

Figure 3. Known locations where men died and on which Mainland European pensions were based. Only those with 3 and above deaths are represented on the chart. For the purposes of this representation all New York harbour military installations were amalgamated with New York, while all battles of the Petersburg Campaign were amalgamated with Petersburg (Click image to enlarge).

Readily apparent is the toll that prison camps, most notably Andersonville, took on Mainland European-born troops. It is also interesting to note the relative impact of different engagements when it comes to this dataset. Battles that are not among the most celebrated during the conflict, for example Cross Keys and Princeton, are prominent on this table, while others such as Antietam (where I recorded two deaths) are not. Indeed, Cross Keys is equivalent in impact to Chancellorsville on the reasons behind the pension claims, despite the fact that the latter engagement is viewed as the most disastrous with respect to German participation in the conflict. Gathering data in this fashion on both sides of the Atlantic also allows us to seek to visualise data in different ways. The map in Figure 4 uses the Palladio Visualization Tool (developed at Stanford) to connect the areas in Mainland Europe where pensions were being claimed with the Confederate prison locations where their loved one’s died.

[image error]

Locations in Mainland Europe where pensions were claimed based on deaths in Confederate prison camps. Andersonville, Georgia dominates. Visualized using Palladio (Click to enlarge).

It is also possible to examine the data from the perspective of State of affiliation (Figure 5). New York is overwhelmingly dominant, with almost four times as many associations with Mainland European pensioners when compared to any other State. Unsurprisingly given their German populations, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Illinois and Missouri also figure strongly.

[image error]

Figure 5. The States/Affiliations of the identified units in which men served and on which Mainland European pensions were based. It includes the United States Regulars and United States Navy (Click image to enlarge).

I am aware that many readers will be eager to discover what specific military units are connected with the dataset; with that mind, at the bottom of this post is a full listing, in numerical order, of all the units I was able to identify and the number of servicemen associated with each (Table 1).

As alluded to above, the main interface for this resource is through the mapping of the pensioners, which was carried out using Google Fusion Tables. Four maps have been produced, two location maps which identify the sites in Europe and the United States where pensioners were based and the servicemen died, and two heatmaps which identify relative concentrations of sites in Europe and the U.S. The latter are particular interesting for identifying regions within Germany where pensioners were at their densest. In order to utilise the location maps, click on the images below to go to map, and zoom in to specific area to explore the material. You can click your mouse over a point to see the information on the pensioner and their loved one’s service and fate. The information you can access for each datapoint can be seen in Figure 6 below.

[image error]

Figure 6. The details you will be able to access with each datapoint on the map. This particular example relates to Johanna Lonntz, whose son Gustav died with the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

It is also worth noting that in order to see all the datapoints in areas of high concentrations (e.g. cities such as Berlin and Paris) you will need to zoom right into that location, as the points are closely spaced. Hopefully there will be information of interest to a wide range of users. Keep an eye out for some of my favourite pensioners in this group, the wealthy American widows who were claiming their pensions while presumably on European tours in France and Italy.

[image error]

Map 1. Widows & Dependents in Receipt of American Military Pensions, Mainland Europe, 1883. Location Map (Click on image to explore map)

[image error]

Map 2. Widows & Dependents in Receipt of American Military Pensions, Mainland Europe, 1883. Concentration Heatmap (Click on image to explore map)

[image error]

Map 3. Widows & Dependents in Receipt of American Military Pensions, Mainland Europe, 1883. American locations where death occurred on which pensions were based (Click on image to explore map)

[image error]

Map 4. Widows & Dependents in Receipt of American Military Pensions, Mainland Europe, 1883. American locations where death occurred on which pensions were based. Concentration Heatmap (Click on image to explore map)

Although I sought to identify as many locations and units as possible, inevitably there are a number I was unable to locate. I would be very interested in hearing from anyone who may have information they can add to this dataset in this regard, or if you have any corrections to offer. For those who wish to access the original excel spreadsheets, you can download the European datasheet here: European Dependent Pensions Mainland Europe: DATA-EUROPE and the American datasheet here: Europe Dependent Pensions Mainland Europe:DATA-USA. Finally, below is the table of military units identifiable for men on whom the Mainland European pensions were based.

Unit

No. Servicemen

United States Navy

12

Mueller’s Battery B, Independent Pennsylvania Light Artillery

1

Independent New York Volunteers

1

Missouri Engineer Regiment of the West

1

1 Connecticut Heavy Artillery

1

1 Kansas Infantry

1

1 Kentucky Infantry

1

1 Louisiana Infantry

2

1 Michigan Cavalry

1

1 Missouri Light Artillery

1

1 New York Cavalry

1

1 New York Engineers

1

1 New York Infantry

1

1 New York Light Artillery

2

1 United States Sharpshooters

1

1 West Virginia Light Artillery

1

1 Wisconsin Infantry

1

2 Delaware Infantry

2

2 Illinois Light Artillery

1

2 Maryland Infantry

2

2 Michigan Cavalry

1

2 Michigan Infantry

1

2 Minnesota Infantry

2

2 Missouri Light Artillery

1

2 New Jersey Cavalry

2

2 Ohio Cavalry

1

2 Rhode Island Infantry

1

2 Wisconsin Infantry

1

3 California Infantry

1

3 Iowa Light Artillery

1

3 Maryland Infantry

2

3 Minnesota Infantry

1

3 Missouri Infantry

2

3 New Jersey Cavalry

2

3 New York Artillery

1

3 Wisconsin Cavalry

1

4 Maryland Infantry

1

4 Missouri Cavalry

2

4 Missouri Infantry

1

4 New York Infantry

1

4 Pennsylvania Cavalry

1

5 Iowa Cavalry

1

5 New Hampshire Infantry

1

5 New York Heavy Artillery

1

5 New York Infantry

1

5 United States Artillery

1

5 United States Infantry

2

5 Wisconsin Infantry

2

6 Connecticut Infantry

1

6 Minnesota Infantry

1

6 Ohio Infantry

1

6 United States Infantry

1

7 Connecticut Infantry

1

7 Minnesota Infantry

1

7 New Hampshire Infantry

1

7 New York Infantry

11

7 New York Heavy Artillery

1

7 United States Cavalry

1

8 Illinois Infantry

1

8 Kansas Infantry

1

8 Michigan Infantry

1

8 New York Infantry

1

8 United States Infantry

1

9 Illinois Cavalry

1

9 Michigan Cavalry

1

9 New Hampshire Infantry

1

9 New Jersey Infantry

1

9 Ohio Infantry

2

10 Massachusetts Infantry

1

11 New Jersey Infantry

1

11 New York Cavalry

1

11 Pennsylvania Reserves

1

12 Illinois Cavalry

1

12 Missouri Infantry

2

12 New Hampshire Infantry

1

12 Pennsylvania Cavalry

1

13 Connecticut Infantry

1

13 New York Infantry

3

13 United States Cavalry

1

14 New York Cavalry

1

14 Pennsylvania Cavalry

1

14 Wisconsin Infantry

2

15 Illinois Cavalry

1

15 Missouri Infantry

3

15 New York Heavy Artillery

7

15 New York Engineers

1

15 West Virginia Infantry

1

16 New York Cavalry

1

17 United States Infantry

1

18 New York Cavalry

1

18 United States Infantry

1

19 Illinois Infantry

1

20 Indiana Infantry

1

20 Massachusetts Infantry

2

20 New York Infantry

1

21 Wisconsin Infantry

1

22 Michigan Infantry

1

23 Indiana Infantry

1

23 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

24 Illinois Infantry

3

25 Ohio Infantry

1

26 New York Infantry

1

26 Ohio Infantry

1

27 Massachusetts Infantry

1

27 Pennsylvania Infantry

3

28 Ohio Infantry

6

29 Massachusetts Infantry

1

30 Missouri Infantry

1

30 Ohio Infantry

1

31 Iowa Infantry

1

31 New York Infantry

2

32 Indiana Infantry

3

32 Massachusetts Infantry

1

33 Ohio Infantry

1

34 Massachusetts Infantry

1

36 Illinois Infantry

1

36 Massachusetts Infantry

1

37 Ohio Infantry

2

39 New York Infantry

6

40 Missouri Infantry

1

41 New York Infantry

3

42 Illinois Infantry

1

42 New York Infantry

1

43 Illinois Infantry

1

45 New York Infantry

1

46 New York Infantry

4

47 New York Infantry

1

47 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

48 New York Infantry

1

51 New York Infantry

1

52 Illinois Infantry

1

52 New York Infantry

4

52 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

54 New York Infantry

3

55 Ohio Infantry

1

55 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

56 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

57 Illinois Infantry

1

58 Illinois Infantry

1

58 New York Infantry

2

58 Ohio Infantry

2

59 Massachusetts Infantry

1

59 New York Infantry

2

61 New York Infantry

1

61 Ohio Infantry

1

66 New York Infantry

1

68 New York Infantry

3

69 New York Infantry

2

73 Pennsylvania Infantry

4

74 New York Infantry

1

75 New York Infantry

2

75 Pennsylvania Infantry

3

75 United States Colored Troops

1

79 New York Infantry

1

80 New York Infantry

1

81 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

82 Illinois Infantry

1

82 New York Infantry

1

83 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

85 New York Infantry

1

89 Ohio Infantry

1

99 New York Infantry

1

98 Pennsylvania Infantry

2

99 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

100 Illinois Infantry

1

100 New York Infantry

2

103 New York Infantry

3

104 Pennsylvania Infantry

1

106 Ohio Infantry

1

108 New York Infantry

1

108 Ohio Infantry

1

113 Illinois Infantry

1

119 New York Infantry

1

131 New York Infantry

1

134 New York Infantry

1

140 New York Infantry

1

148 New York Infantry

1

156 Illinois Infantry

1

163 New York Infantry

1

174 New York Infantry

1

175 New York Infantry

1

176 New York Infantry

1

181 Ohio Infantry

1

183 Ohio Infantry

3

Table 1. The identifiable units associated with the Mainland European pensions, in numerical order.

(1) Apthorp Gould 1869: 27;

References

Gould, Benjamin Apthorp 1869. Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers.

Government Printing Office 1883. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883. Volume 5

Filed under: Mapping Pensions, Pension Files Tagged: Dependent Pension Files, Europeans in the Civil War, Germans in the Civil War, Google Fusion Tables, Irish American Civil War, Online History Resources, Palladio, Widow's Pension Files

March 20, 2017

Video: Discussing Forgotten Irish Emigrants at the National Archives, Washington D.C.

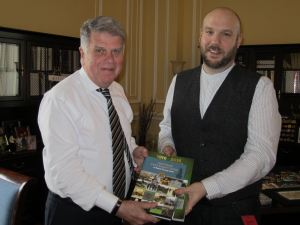

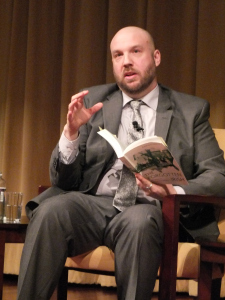

Last week I had the great honour of taking part in a discussion and audience Q&A at the National Archives in Washington D.C. with Dr. Michael Hussey of NARA and Professor David Gleeson of Northumbria University. The event was followed by the American launch of my book The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences in America, which draws primarily on widows and dependent files housed in NARA’s collections. For a bit more of the backstory behind my work on these files, you can check out the National Archives News article on my visit by clicking here. During the trip I also got to meet Mr. David Ferriero, the 10th Archivist of the United States. Mr. Ferriero has roots in Co. Cork, so I was delighted to present him with a copy of the book I recently wrote for Cork County Council on Cork’s revolutionary past. The Forgotten Irish discussion in the McGowan Theater was very well attended and we had some excellent interaction with the audience. I want to extend my thanks to all the staff at the National Archives who made the event possible, and who took such good care of us on the night.

The full event is now available to view on YouTube, which you can see below- the main discussion begins at the 12.21 mark. I would be keen to hear reader’s thoughts!

It is worth noting that for anyone near D.C., you can get 15% of my book in the Archives shop when you mention the presentation. The book itself dosen’t go on general release in the States until May, so for the next few weeks it is the only place to get it. While in the Archives I took the opportunity to do some archival research into some Irish-related topics, so watch this space in the next few weeks for some posts on that material.

A debt of gratitude is also due to photographer Bruce Guthrie, who took some great shots of the event, some of which are also shared below. You can check out Bruce’s homepage here.

Filed under: Events Tagged: Damian Shiels, Forgotten Irish, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Emigrant Experiences in America, McGowan Theater, National Archives Widows Pension Files, The History Press

March 9, 2017

“I am the Same Boy yet”: The Civil War Letters of Daniel Crowley, Part 2

The site welcomes back Catherine Bateson of the University of Edinburgh for the second in her series on the 1864 letters of Cork native Daniel Crowley, who served in the 28th Massachusetts Infantry, Irish Brigade (read the first post here). As the regiment pushes on to Petersburg, Daniel writes home of hand-to-hand combat, on his prospects of survival, and of the circumstances of his enlistment.

[image error]

Federal line at Petersburg (Library of Congress)

Three months into his time “in Uncle Sams employment” in the 28th Massachusetts, Daniel Crowley’s letters home to his friend Cornelius Flynn in Marlborough, Massachusetts, had developed from the correspondence of an eager young recruit in March 1864, to a weary, battle-hardened soldier by June of that year, scarred by conflict horrors. (1) The tone of his letters reflected this change, as he mixed an increasingly sarcastic, bitter and despondent voice with attempts at dark cheerfulness, still trying to convey to Flynn that all was well. While the 28th Massachusetts may have had “some hard times”, and Crowley no longer “cared about dancing on the bodies of dead men” as mentioned in the previous post, he also found time to write home for a more light-hearted request. He asked Flynn: “If you can get that old hat of mine from Mrs. Driscoll, fold it up and send it to me…I guess it would be much easier than the cap I wear”. It was a simple appeal, but tainted with the memory of a comment made in an earlier letter about how Crowley had narrowly avoided injury, or worse, after his cap had been shot from his head during one particular skirmish.

By the end of June 1864, Crowley found himself corresponding to Flynn “Before Petersburg”, where the 28th Massachusetts involvement in the siege and sporadic fighting there over the course of the summer months gave him pause to reflect about the wider war, his purpose in the army and, understandably, think about his own mortality and war’s futility. Writing to Flynn on June 30 1864, Crowley opened up again about his near-death experiences and first-hand encounters with Confederate soldiers:

“I had a hard fight myself as I was either a prisoner or a dead man. I had my choice but unfortunately my Irish Blood would not yield and I chanced the latter after Bayonetting one Reb and shooting another. It was a hand to hand affair and believe you me the Johnies are afraid of the steel while it is in an Irishman’s hand”.

For all his fighting Irish pride though, Crowley’s awareness about the battlefield’s diminishing odds returned. Gone were his previous thoughts that Irish Brigade veterans told “tall tales about their escapes from death” as he had told Flynn at the start of his enlistment. Now Crowley realised that his own survival was miraculous and limited. He told his friend fatalistically: “I expect myself I can’t survive much longer after all the narrow escapes I had”.

[image error]

Union picket at Petersburg (Library of Congress)

This was a similar sentiment to the one expressed in his letters from earlier that month, quoted in the previous post. June 1864 took a dark toll on Crowley’s sense of his own mortality. As with his letter on 19 May with the postscript that acknowledged his fear that he “might not write” again to Flynn, his letter from the end of June made similar reference to the awareness that every line he wrote could well be his last. He ended his correspondence promising to visit and “call to see” Flynn and his family, as well as other friends, “when I go home” but added the caveat “if I live” to make it clear that his hope was diminished. Flynn would have come to the same realisation that readers of these letters today will note – when Crowley stated at the end of this particular letter that “I am the Same Boy yet”, the comment could not have been further from the truth. His encounters after just three months of enlistment and service, and the increasing despair exhibited in his letters, revealed that Daniel Crowley was far from “the Same Boy” who had joined the 28th Massachusetts in March 1864. His optimism had been replaced with war weary pessimism.

Crowley’s 30 June letter to Flynn was the last in which he articulated explicit dark thoughts, but the depression and despondency brought on by his experiences thus far left their mark on the way in which he reported the war and his encounters. It also extended to the way in which he talked about his regiment. He noted to Flynn that due to its heavy losses, while the 28th Massachusetts were still standing the illustrious Irish Brigade that it was part of was on far more unsteady legs. Referring to its origins and establishment by General Thomas Francis Meagher earlier in the war, Crowley lamented that “Tom Meagher and the remnants of his Brigade [were] buried in oblivion” by mid-summer 1864 and that “Our Brigade is broken up…there is no longer an Irish Brigade”. Crowley’s comments to Flynn about the Irish Brigade’s history, and the pride it engendered in its soldiers and the Union Army, are interesting given that he had only been serving in it for barely three months at the point of writing. This reflects a recurring primary source theme in Irish American Civil War studies. The level of affection and devotion the Irish Brigade inspired within the Irish American diaspora and the soldiering community which Crowley was a part of, and Flynn would undoubtedly been aware of, is yet again on display in the former’s comments about his association with the unit.

Crowley had taken on the past glories and history of his regiment and the brigade as part of his own military service. While noting with despair the “oblivion” of the Irish Brigade by June 1864, he proclaimed proudly “Thanks to the Irish Brigade for saving this army from total disaster”. It is hard not to picture the battle hardened new recruit standing with pride in the knowledge that the 28th Massachusetts “still retain the green flag”, the flag that “I will die under”. In a subsequent letter written to Flynn in November 1864, Crowley informed his friend that the 28th Massachusetts “again are in the Irish Brigade” as the unit returned in name only, with no loss in its own sense of honour. Again, Crowley drew on its past histories to explain recent brigade developments, stating in a postscript that the Irish Brigade were to be commanded “by Col. Nugent of the 69th N. York – Lt. Col. of the old 69th of Bull Run fame under Corcoran”.

[image error]

USCT troops on the line at Petersburg (Library of Congress)

Crowley’s sense of honour about serving in such a famed and noteworthy regiment and brigade was something the young Massachusetts Irishman was very proud of and perhaps explains his bristling when his enlistment was called into question in the second half of 1864. As mentioned in the previous post, Crowley emphasised to Flynn that he was “not sorry for enlisting” and wished for people in Marlborough to know this. He returned to the subject over a couple of letters in July 1864, highlighting how Crowley could not let the matter go without full explanation for the events that took him to a Boston recruiting office several months previously. He claimed to his friend on 8 July 1864, that he had been made to enlist by one “John McCarthy of 108 Federal St., Boston” so that McCarthy could receive “$160 out of it”, which he split with another. Flynn, it would appear through reading the subtext of Crowley’s responses, was being blamed in Marlborough “as being the cause of [Crowley’s] enlisting” and collecting the bounty for his own purposes. The young soldier emphasised this was fundamentally not the case: “No Con”, he said using his affection nickname for Cornelius Flynn, “you often advised me not to, and it was against your consent I done so [enlisted]”. A couple of weeks later, on 22 July 1864, Crowley was still clearly bothered that Flynn was being held to account, defending his friend’s character and conduct by stressing that he “felt greatly annoyed at any person insinuating to you such acts”.

Crowley reiterated his stance that he did not regret the actions that led to his enlistment, nor was he sorry for being in the army despite the mounting psychological toll his involvement was taking. In early August 1864, he wrote to Flynn to state with a sense of ceremony that “I have been made sergeant”, and one month on he wrote “I cannot help doing my duty”. War had become an everyday part of Crowley’s persona. By October 1864 though, another letter from his hometown gave him pause to reassess the realities of war. Flynn had sent a note to his friend, now based around Petersburg, asking, “if I would advise you to enlist”. Crowley was quick with a response:

“I would not advise any person. It’s the task of all for a man to do. I mind this war is not going to end so soon as people think. The Rebs are very far from being whipped yet and God only knows who will live to see the last of it”.

This response to the thought of a close acquaintance enlisting in the Union Army echoes that of Crowley’s fellow 28th Massachusetts solider Peter Welsh, who had written to his recently emigrated brother-in-law in the spring of 1864 to stress “never for heavens sake let a thought of enlisting in this army cross your mind”. (2) Both Irish Brigade soldiers were committed to seeing the war through, but what they had witnessed on the battlefields had both made them resistant to thought they their own loved ones should share the same experience. Experiencing the war through their letters was a close enough encounter.

[image error]

Soldiers quarters at Petersburg (Library of Congress)

References & Further Reading

(1) All quotes from Daniel Crowley to Cornelius Flynn are taken from a series of letter correspondence between March 1864 and May 1865, now held in the Boston Athenaeum special collections archive.

(2) Peter Welsh to Francis (Frank) Prendergast, April-May 1864, in Irish Green and Union Blue: The Civil War Letters of Peter Welsh, Colour Sergeant, 28th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, eds. L.F. Kohl & M.C. Richard (New York: Fordham University Press, 1986), p. 155.

Civil War Trust Battle of Petersburg Page

Petersburg National Battlefield

Filed under: 28th Massachusetts, Battle of Petersburg, Cork, Guest Post, Irish Brigade, Massachusetts Tagged: 28th Massachusetts, Catherine Bateson, Hand to Hand Combat, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Petersburg, Massachusetts Irish, Siege of Petersburg, Union Recruitment

March 6, 2017

Exploring the 1867 Fenian Rising in Cork

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the 1867 Fenian Rising in Ireland. Though the attempt ended in failure, it played an important role in influencing future revolutionaries who undertook the 1916 Rising. East Cork, where I live, was one of the areas of the country where some of the most significant disturbances took place. As part of my role with Rubicon Heritage Services, I recently completed a book for Cork County Council examining the history and archaeology of sites associated with revolution in Cork. Entitled The Heritage Centenary Sites of Rebel County Cork, as part of that I explored some of my work on sites associated with 1867 in the county. With the permission of Cork County Council, I am reproducing the relevant section below. For those with an interest in the American Civil War, what becomes immediately apparent is the importance placed on returned veterans in the plans for the Rising- some of whom had not even been born in Ireland.

[image error]

The Heritage Centenary Sites of Rebel County Cork (Cork County Council)

In 1866, the British administration suspended habeas corpus, which allowed for detention without trial. That same year, Fenians in the United States who hoped to spark a border dispute between the U.S. and Britain launched a raid into Canada, which came to grief at the Battle of Ridgeway. Plans moved ahead for a Rising in Ireland, and a number of American Civil War veterans made their way to the country in the hope of providing assistance. In addition, the American Fenians dispatched the vessel Erin’s Hope to Ireland on 13 April 1867 with a supply of arms to support the effort (You can read more about the Erin’s Hope story here and here). But by the time the ship arrived, the attempted Rising was already over. It had taken the form of a series of disjointed and largely abortive actions at different locations around the country, beginning in Kerry in February . The major effort was in March, and was introduced by the issuance of a proclamation of the Irish republic that can be seen as a precursor for what was to be delivered at the GPO in 1916:

I.R.– Proclamation:– The Irish People to the World. We have suffered centuries of outrage, enforced poverty and bitter misery. Our rights and liberties have been trampled on by an alien aristocracy, who, treating us as foes, usurped our lands and drew away from our unfortunate country all material riches. The real owners of the soil were removed to make room for cattle, and driven across the ocean to seek the means of living, and the political rights denied to them at home; while our men of thought and action were condemned to loss of life and liberty. But we never lost the memory and hope of a national existence. We appealed in vain to the reason and sense of justice of the dominant powers. Our mildest remonstrances were met with sneers and contempt. Our appeals to arms were always unsuccessful. To-day, having no honourable alternative left, we again appeal to force as our last resource. We accept the conditions of appeal, manfully deeming it better to die in the struggle for freedom than to continue an existence of utter serfdom. All men are born with equal rights, and in associating together to protect one another and share public burdens, justice demands that such associations should rest upon a basis which maintain equality instead of destroying it. We therefore declare that unable longer to endure the curse of monarchical government we aim at founding a republic based on universal suffrage which shall secure to all the intrinsic value of their labour. The soil of Ireland, at present in the possession of an oligarchy, belongs to us, the Irish people, and to us it must be restored. We declare also in favor of absolute liberty of conscience, and the complete separation of Church and State. We appeal to the Highest Tribunal for evidence of the justice of our cause. History bears testimony to the intensity of our sufferings, and we declare, in the face of our brethren, that we intend no war against the people of England–our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields– against the aristocratic leeches, who drain alike our blood and theirs. Republicans of the entire world, our cause is your cause. Our enemy is your enemy. Let your hearts be with us. As for you workmen of England, it is not only your hearts we wish, but your arms. Remember the starvation and degredation brought to your firesides by the oppression of labour. Remember the past, look well to the future, and avenge yourselves by giving liberty to your children in the coming struggle for human freedom. Herewith we proclaim the Irish Republic.

THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT

[image error]

The bridge in Midleton where in 1867 constabulary officers faced Timothy Daly and his Fenians, marching towards the camera. The firefight which ensued left one of the costables mortally wounded (Damian Shiels)

The 5 March was set as the date for the main Rising, but poor-coordination and the efficiency with which the Government had targeted the movement’s leaders meant that it ended in failure. The largest engagement in the country took place in Tallaght, but there was also notable activity in Cork. Police barracks such as that at Ballyknockane were attacked in order to obtain arms and railway tracks were targeted to disrupt communications . One of the major incidents involving the Fenians in the county was that led by Timothy Daly. The actions of he and his followers, which began in Midleton, were later described in the London Times:

The Fenians collected on the fair green to the number of about 50, and marched through the town in military order. They were all armed, and had haversacks of provisions. At the end of the town, near Copinger’s-bridge, they were met by an armed police patrol of four men. The Fenian leader called on the patrol to surrender, and the demand was followed up by a volley, by which one of the four constables were killed and another slightly wounded. The uninjured men returned the fire, with what effect is not known, and made their escape hastily into an adjoining house, whence they afterwards regained the barracks. The Fenians marched from Midleton to Castlemartyr, leaving the police barrack in the former town unmolested. On the route they were joined by several parties of armed men, and arrived in Castlemartyr with a force about 200 strong. Daly, the Fenian leader, drew up his men in front of the police-barrack, which had been closed and barricaded on their approach, and called on its occupants to surrender. The policemen, who did not exceed six or seven in number, replied by a well-directed fire, killing Daly and wounding several of his band. The remainder then retired in the direction of Killeagh, to which place small parties of men were seen making their way from Cloyne, Youghal and several other places during the night.

[image error]

The Green House in Midleton, where one of the constabulary officers took refuge after the Fenian attack. The wall in front of the house was said to have been peppered with bullet holes (Damian Shiels)

[image error]

The barracks in Castlemartyr, Co. Cork. Fenian leader Timothy Daly was shot and mortally wounded while trying to attack this building in 1867 (Damian Shiels)

It is interesting to note the role played by American Civil War veterans in the county. Patrick J. Condon had served as a Captain in the 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade, fighting at battles such as Antietam and Fredericksburg . Condon had been assigned to take military command in Cork, but was arrested on 2 March, before the Rising began . Some of these Fenian veterans were American by birth. John William Mackey Lomasney, who had participated in the attack on Ballyknockane barracks and who later in the year launched a raid against Monning Martello Tower at Fota– supposedly the only Martello Tower ever taken– has variously had his place of birth recorded as Maryland, Ohio and Fermoy . He is likely to have served in the 179th New York Infantry during the Civil War . Another was John McClure, who had been born in Dobbs Ferry, New York in 1846 to Irish parents . During the Civil War he had served as a Quartermaster Sergeant in the 11th New York Cavalry, but in March 1867 he found himself creeping towards a coast guard station in East Cork at the head of a group of Fenians . Due to his military experience, McClure had been assigned to command of the Midleton District . Their action at Knockadoon Coastguard Station was later described by John Devoy:

…at the outset they had only one rifle…a few old shotguns, and McClure’s Colt’s revolver. There were a few pikes, and some of the men had sharpened rasps, fastened to rake handles with waxed hemp. With that paltry armament very little could be expected of them, but they did a very creditable piece of work. On three sides of the Coastguard Station there was a sort of platform made of planks, and on the one in front a sentry paced up and down…After carefully examining the surroundings, Crowley’s men took up a position in the rear of the station and McClure and Crowley crept silently along the plans on one of the dark sides, stood up close to the front and waited. When the sentry reached the corner McClure gripped him by the collar of his coat, put the revolver to his breast, and whispered to him that if he said a word he would be shoot. They then took his rifle and went to the door, which was not locked, the men following silently, opened it and went in quietly. The Coastguards were all lying down and most of them were asleep. The arms rack was beside the door and the rifles were secured at once. The Coastguards were made prisoners and marched toward Mogeely, a station on the Youghal Railway ten or twelve miles away, where they were set at liberty.

[image error]

Fenian mugshot of Patrick J. Condon, 2nd New York State Militia and later Captain of Company G, 63rd New York, Irish Brigade. Born in Creeves, Co. Limerick, he was to have played a leading role in the Rising in Cork (New York Public Library)

[image error]

The site of Knockadoon Warren Coastguard Station, Co. Cork, attacked in 1867 by John McClure, an American-born veteran of the 11th New York Cavalry (Damian Shiels)

[image error]

The muster-roll abstract detailing John McClure’s service in the 11th New York Cavalry, with his physical description (New York State Archives/Ancestry)

It quickly became apparent that the Rising was a failure. Among those with John McClure at Knockadoon was Peter O’Neill Crowley, who led the Ballymacoda Fenians and Edward Kelly from Youghal . When they realised no aid was coming and that the Rising had failed they moved off northwards, with police and troops on their trail. Kelly could not keep up the pace and was arrested, but McClure and Crowley made it as far as Kilclooney Wood near Mitchelstown . There they were surrounded on 31 March:

[They] were soon confronted by a soldier, who shouted to them to halt and give the countersign. Crowley levelled his rifle and fired at him, saying: “There’s the countersign for you.” The bullet did not hit the soldier and they were fired on from several points at once. The wood was filled with soldiers, evidently searching for them. The two men turned in other directions several times, but every time they turned they found soldiers in front of them, not in military formation, but scattered singly. Every soldier who saw them fired, and at last Crowley was hit and severely wounded. Evidently several bullets struck him, but not one hit McClure. They could have escaped the bullets in the beginning of the running fight by surrendering, but neither had the slightest thought of doing so. Shortly after Crowley was hit they reached the edge of the wood where they attempted to cross the Ahaphooca stream which skirted it. Crowley was weak from loss of blood, and in the stream McClure had to put his left arm around him, as his legs were fast weakening. He was six feet two in height, broad-shouldered, deep-chested, and very powerfully built, and in his efforts to hold him up McClure, who was only five feet seven, but strongly built, had to stoop, so that the revolver in his right hand dipped into the water and the old-fashioned paper cartridges with which it was loaded got wet. But McClure, in his excitement, didn’t know it. Soldiers and policemen came running up on the outer bank of the stream, with a magistrate at their head, and the magistrate, who wore top boots, stepped into the water and called on McClure to surrender. McClure pointed his revolver at him and pulled the trigger, but, of course, it didn’t go off, because the ammunition was wet. He was speedily overpowered and dragged up on the bank. Crowley was lifted up and placed lying on the bank, and it was at once seen that his wounds were mortal.

[image error]

The monument in Ballymacoda to Peter O’Neill (Courtesy of Martin Millerick)

The spot where Peter O’Neill Crowley gave his life in Kilclooney remains well remembered to this day. There were individuals from all over the county closely associated with the events of 1867. A number of memorials to them are dotted around Cork, such as that to Timothy Deasy in Millstreet. Originally from Clonakilty, Deasy served as an officer in the 9th Massachusetts Infantry during the American Civil War . Another is to Ricard O’Sullivan Burke, who had served in the 15th New York Engineers during the American Civil War and who is mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses . He is remembered with a memorial in his native Kenneigh.

[image error]

Monning Tower on Cork Harbour. It was captured in 1867 by John William Mackey Lomasney, a veteran of the 179th New York Infantry (Damian Shiels)

The 1867 Fenian Rising had further echoes beyond Ireland’s shores that involved both Deasy and O’Sullivan Burke. In September 1867 Timothy Deasy and fellow Fenian leader Thomas Kelly (a veteran of the 10th Ohio Infantry) were arrested in Manchester. It was decided to try and break them out, and on 18 September, while the prisoners were being transferred in a prison van, a rescue was staged, coordinated by O’Sullivan Burke. Though Deasy and Kelly were freed, a policeman was accidentally killed during the action. Among those participants in the breakout subsequently arrested were William Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien. William Allen and Michael O’Brien were both from Cork– Allen from Bandon and O’Brien from near Ballymacoda. Like so many others, O’Brien was a Civil War veteran, having served in the 5th New Jersey Light Artillery. The three were tried and executed for their role in the events, and subsequently became known as the Manchester Martyrs. Today a memorial commemorates them in the village of Ladysbridge, near where O’Brien was from.

[image error]

Memorial to the Manchester Martyrs in Ladysbridge, Co. Cork. One of them was local man Michael O’Brien, a veteran of the 5th New Jersey Light Artillery (Damian Shiels)

References

Ó Concubhair, Pádraig 2011. ‘The Fenians Were Dreadful Men’: The 1867 Rising. Mercier Press, Cork, 167.

Ibid., 58.

The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 16 May 1867

Ó Concubhair, Op. Cit., 139.

The London Times 8 March 1867.

Savage, John 1868. Fenian Heroes and Martyrs. Patrick Donahoe, Boston, 255.

Ibid., 153, 259.

Kane, Michael 2002. ‘American Soldiers in Ireland, 1865-67’ in The Irish Sword: The Journal of the Military History Society of Ireland Volume 23, No. 91, 103-140, 125; Dictionary of Irish Biography. “Lomasney, William Francis Mackey” by Desmond McCabe and Owen McGee at http://dib.cambridge.org/viewReadPage.do;jsessionid=4DF08581ACAA223F4CBE7A3AC95621FD?articleId=a4877 Accessed 16 September 2016.

Kane, Op. Cit.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Savage, Op. Cit., 273.

Devoy, John 1929. Recollections of An Irish Rebel. Chase D. Young, New York, 213-4.

Ó Concubhair, Op. Cit., 139-40.

Devoy Op. Cit., 215.

Ibid., 215-6.

Kane, Op. Cit., 119.

Ibid., 116.

Ó Concubhair, Op. Cit., 146; Kane, Op. Cit., 124.

Filed under: Cork, Fenians Tagged: 1867 Fenian Rising, Captain Mackey, Fenian Brotherhood, Irish American Civil War, Knockadoon Coastguard, Manchester Martyrs, Monning Martello Tower, Timothy Daly

February 27, 2017

Mapping Scotland’s 19th Century American Military Pensioners

As part of my continuing work on Civil War pension files, I returned again to Scotland (for my previous work on Scots in the Civil War see here and here), to comprehensively map all the American Pensioners in Scotland recorded in the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll. In 1882 Congress instructed that this list be compiled in order to document all individuals then in receipt of monies for service in the American military. In addition to mapping where these people lived, I also wanted to find out more of their personal stories. To that end I also sought to explore in detail each of the 30 individuals who were receiving pensions in Scotland during 1883.

What the pensions reveal are a series of fascinating insights into Scottish emigrants in the 19th century. Clearly apparent is the dominance of Scotland’s Central Belt among those who claimed these pensions, but other interesting aspects are also revealed; for example the presence of a number of weavers among those men who emigrated, and of the traditional emigration links between Scotland and Canada and Ireland and Scotland. Differing realities with respect to marriage are also revealed– below you will find details on a husband who left his wife for America immediately after their marriage, of a husband who committed bigamy against his wife, and of a man who returned briefly to marry in Scotland before leaving once again to serve the American military. Many of the pensioners had been affected by some of the great battles of the Civil War, such as Fredericksburg and Petersburg. The horrors of Andersonville Prison also loom large, and we see some last letters transcribed for the first time. The resource below starts with the mapping element, prepared on Google Fusion Tables. Beyond that are the relevant biographies, which I hope readers find of interest.

Click on the image to go to the Google Fusion Table interactive map of the 1883 Scottish Pensioners. Each tag reveals the basic information relating to every pensioner. Glasgow has the highest concentration, so zoom into the city to view the individuals there.

[image error]The Fusion Tables heatmap of the 1883 Pensioners in Scotland. Click on the image to explore in further detail. The concentration in the central belt is immediately apparent.

Anthony Hillcoat, Ardrossan, Ayrshire. United States Navy.c. 1823. Enlisting in the Navy in 1857, he served as a First Class Fireman aboard USS Saranac and USS Niagara. His first injury occurred when he fell down on a pipe. He recovered and served aboard USS Niagara on her trip to Japan, a voyage that brought Japan’s first diplomatic mission to the U.S. home. He was later assigned to work as a boiler maker in Pensacola, where he was hurt in another fall, which resulted in his discharge on 12 September 1861. Returning to Scotland, he had to wear a truss all the time due to his incapacity. He received his pension for this injury to his abdomen and orchitis, getting $8 per month from 1879.

USS Niagara, the vessel on which Anthony Hillcoat sailed to Japan (Naval History & Heritage Command)

Isabella Sherret, Brechin, Angus (Forfarshire). Widow of Graham Sherret, 67th New York Infantry.Graham Sherret and Isabella Milne had married in Brechin on 20th May 1853. Graham had been a mason at the time, and they were both living on the City Road in the town. Graham enlisted in the Union army on 24th June 1861, serving in Company K of the 67th New York Infantry. He was promoted to Corporal on 1st February 1863. Graham was shot in the head and mortally wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia on 6th May 1864. Isabella lived at 40 Union Street in Brechin when she was in receipt of her pension, which was $8 a month and was approved in 1865.

Union Street in Brechin, where Isabella Sherret lived after her husband was killed at the Battle of The Wilderness, Virginia.

James Wilkie, Dundee, Angus (Forfarshire). 1st Michigan Cavalry.

Born c. 1835. A member of Custer’s famed Michigan Brigade, the Wolverines. Enlisted in Company C of the 1st Michigan on 30th October 1863 in Detroit and was discharged at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on 10th July 1865. Received a pension of $2 per month for a wound to the left leg from 1879. His name is remembered on the American Civil War Memorial in Old Calton Cemetery, Edinburgh.

Detail of soldier’s names on the Old Calton American Civil War Memorial, which includes James Wilkie, one of Custer’s Wolverines (Damian Shiels)

Henry Myers, Dunfermline, Fife. “Old War” Service.Henry received his pension of $4 per month for a wound to the right leg. His pension was for “Old War” service, i.e. service that predated 1861 (and included conflicts like the Mexican War).

Jane Fortune, Thornton, Dysart, Fife. Widow of John Fortune, 5th Ohio Infantry.

John Fortune and Jane Paterson were married by Minister James Lowe in Thornton Parish Church on 10th May 1858. John was a labourer from Leven while Jane worked as a weaver in Dysart. John had enlisted on 19th June 1861 and served in Company E of the 5th Ohio. He was killed in action on 15th May 1864 at the Battle of Resaca, Georgia. Jane collected $8 per month dating to 1866, receiving payments until her death in the 1890s.

Thornton Parish Church, where John Fortune and Jane Paterson were married. John was later killed in action at Resaca, Georgia, as Sherman campaigned towards Atlanta.

Alexander McNeil, Dysart, Fife. United States Navy.

Alexander was born on 19th October 1837 in Sinclairtown, the son of a linen weaver from Pathhead, Dysart. He spent much of his life at sea, and like many sailors wore tattoos on his hands (an “A.M.N.” on the back of his left hand, an anchor on the back of his right). He enlisted in the Union Navy at Brooklyn in February 1865 and served a Seaman aboard the receiving ship USS North Carolina (until March 1865), the torpedo boat USS Naubuc (until July 1865 when he returned to the North Carolina) and finally aboard the training ship USS Constitution (which survives today, and is a major tourist attraction). While on the Constitution at Annapolis on 16th August 1865 a hawser cable came apart and struck him while the vessel was being hauled over a bar by a tug. The impact took away his left eye and deformed the left side of his face, while also fracturing his left forearm and left thigh. In later years cataract in his right eye would severely reduce his sight. After treatment he was discharged in August 1866, and was given permission to operate a cake stand beside the Constitution, which he did for a period after the war. In 1870 he left Annapolis and returned to Scotland, marrying factory worker Elizabeth Murray on 1st January 1872 at Coalgate, Dysart, with the ceremony being performed by the Reverend William Guthrie. They would go on to have at least five children. He received a pension of $15 per month until his death at 47 High Street in Dysart on 20th October 1913 from a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of 74. His wife Elizabeth subsequently made a claim for the payments. Including in the file is a newspaper clipping provided by Elizabeth, which charted Alexander’s life and is reproduced below.

The newspaper cutting charting the career of Alexander McNeil of Dysart, and included by his wife in her application for a widow’s pension based on his service (NARA/Fold3)

Alexander Smith, Edinburgh, Lothian. 66th New York Infantry.Alexander was 42-years-old when he enlisted on 7th September 1861, becoming a private in Company G of the 66th New York. He was promoted to Sergeant on 1st January 1862, and was wounded at Fredericksburg on 11th December 1862, as a result of which he lost his right foot. He was discharged for wounds on 1st May 1863 at Harewood Hospital in Washington D.C. Returning to Scotland, he received a pension of $18 per month from October 1863. His name is remembered on the American Civil War Memorial in Old Calton Cemetery, Edinburgh.

Another view of the American Civil War Memorial in Old Calton Cemetery, Edinburgh, where Alexander Smith is remembered (Damian Shiels)

John Owens, Falkirk, Central Lowlands. 7th U.S. Infantry.John served in Company C of the 7th U.S. Infantry, and received a pension of $4 a month from January 1881 for a disability to his lungs. He may well have served with the unit during the Indian Wars, though this is yet to be confirmed.

Margaret Affleck, Galashiels, Selkirkshire. Widow of Thomas Affleck, 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery.

Margaret Kyle and Thomas Affleck, a woollen weaver, were married in Lilliesleaf, Roxburghshire on 4th December 1846. They had five children but only two sons, Robert (b. 1847) and William (b. 1856), survived. Thomas travelled to the United States and became a member of Company F of the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavies on 29th February 1864. Captured during the fighting in Virginia, he died a prisoner of war at Andersonville in Georgia on 6th November 1864 of Scorbutus. Margaret lived on Roxburgh Street in Galashiels while she collected her pension of $8 a month, which was granted in 1868. She died on 8th November 1906.

Inspection of the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery in 1864, when Thomas Affleck from Lilliesleaf was a member of the unit (Alfred Waud/Library of Congress)

Andrew Angus, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. 72nd New York Infantry.Andrew Angus enlisted in the 72nd New York as a private on 9th November 1861 at Dunkirk, New York. The 36-year-old served in Company H. He was wounded at Williamsburg, Virginia on 5th May 1862, and re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer on 24th December 1863. He was again wounded on 6th May 1864 at The Wilderness, Virginia, and was transferred to Company E of the 120th New York while still recovering. On 1st June 1865 he was again transferred, to the 73rd New York Infantry, but had still not regained his health. He was absent in the U.S. General Hospital at muster out in July. Andrew received a pension of $8 a month for a wound to his left groin paid from November 1865. He died on 26th November 1896, after which date his wife received a widow’s pension.

John Carr, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. United States Navy.

The details of John Carr’s service in the Navy are still to be established. He received a pension for total blindness from July 1875 amounting to $72 per month.

Janet Dempster, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of John Dempster, 7th Rhode Island Infantry.

John served in Company E of the 7th Rhode Island. He enrolled at Providence on 13th August 1862, and was killed in action at Fredericksburg, Virginia on 13th December 1862. Janet received $8 per month from December 1871.

John Dempster was one of a number of Scots in the 7th Rhode Island Infantry. Another was Lieutenant John McKay, a native of Johnstone in Renfrewshire, who was severely wounded at Petersburg (The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War)

Catharine Fleming, Tradeston, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of Archibald Fleming, United States Navy.Scottish emigrants Catharine McLauchlan (who lived in Philadelphia) and Archibald Fleming were married in New York on 13th March 1856 by Presbyterian Minister John Brash. The couple had three children William Alexander (born in New York in December 1856), Catherine (born in St. Mary’s, Perth, Canada West in February 1859) and Isabella (born in New York in July 1861). Archibald enlisted as a Fireman in the Navy on 16th January 1864. He was assigned to the gunboat USS Chenango, which proceeded from New York to join the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron on 15th April. One of her boilers exploded, scalding over 30 men, 28 of whom died. Archibald was one of those fatally scalded, and was brought back to New York where he passed away at 1.30 am on the morning of 16th April. Catharine’s pension was approved in April 1873, and she received payments for the remainder of her life at 38 Nelson Street in Tradeston. She died around 1903.

Mary Liston, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of Robert Liston alias Henry Clark, 1st New Jersey Infantry.

Mary was the mother of Robert Liston (sometimes Leiston) who served in Company G of the 1st New Jersey Infantry. He is recorded as having mustered in as a private on 23rd January 1864. He was serving in Company B of the 1st Battalion at Petersburg, Virginia when he was wounded in action, and he died at Lincoln U.S. Army General Hospital as a result on 14th April 1865. Mary, though officially listed as his widow on the roll, appears to have been his mother. She received a pension of $8 per month from June 1878.

Lincoln General Hospital in 1865, where Glaswegian Robert Liston lost his battle for life (Library of Congress)

John McCann, Bridgeton, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. United States Navy.John, a native of Glasgow, enlisted at Boston on 14th October 1872 and served as a Seaman aboard USS Richmond. He received a pension of $8 per month for a right inguinal hernia suffered in the service aboard the Richmond at Key West, apparently caused when wrenching his body in an effort to keep his vessel from chafing alongside a burning ship, the Northwester. John ultimately returned to Scotland, where he died at 188 Preston Street in Bridgeton on 30th January 1909, having been bed-ridden for a year. A claim for reimbursement for his burial was made which included a bill from William Hood MacKinlay Undertakers of 205 Dalmarnock Road in Glasgow.

The bill from William Hood MacKinlay Undertakers for the burial of former U.S. Sailor John McCann (NARA/Fold3)

Margaret McFarlane, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of John McFarlane, 11th New Hampshire Infantry.Margaret Alexander and John McFarlane were married by the Reverend Robert Paisley in Partick on 14th October 1842. Their son Walter was born around 1858. John was enrolled in Company B of the 11th New Hampshire from Portsmouth on 17th December 1862 (he was borne as McFarland). He contracted chronic diarrhea and died at the Ninth Corps Hospital at City Point, Virginia on 10th October 1864. Margaret received $8 per month from June 1866 in pension payments.

American Cosuls in Scotland played a key role in helping Scottish pensioners navigate the application process. Here os one of the Glasgow Consul’s documents relating to Margaret McFarlane’s application (NARA/Fold3)

Thomas Provan, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. 28th Massachusetts Infantry.Thomas Provan enlisted in the 28th Massachusetts of the Irish Brigade and was mustered into Company D from Somerville, Massachusetts on 18th March 1864. A boiler-maker by trade, he was recorded as having blue eyes, brown hair, a light complexion and was 5 feet 5 1/2 inches tall. Thomas was wounded in the hand while on picket at Totopotomoy Creek on 31st May 1864. He was captured at the Second Battle of Deep Bottom on 16th August 1864, and confined first in Belle Isle, Richmond (where he suffered from intermittent fever) and then in Salisbury, North Carolina. He was paroled at North East Ferry, North Carolina on 1st March 1865, and was furloughed from Camp Parole in Maryland on 19th March. He spent time in hospital in Readville, Massachusetts, but returned to his unit on 15th May 1865 and was mustered out on 30th June 1865. He was allowed a pension of $4 per month from September 1878.

Elizabeth Shepard, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of James Shepard, 6th United States Infantry.

On 10th August 1860 James Shepard and Elizabeth Spence (then a widow) were married in Ayr, aged 36 and 39 respectively. At the time both were residents of the Allison Street in Newton. It seems likely that a decision had already been taken that James would go to America, as he enlisted in the U.S Army only weeks later on 1st November 1860 and served in Company G of the 6th U.S. Infantry. During his time in America he wrote home on a number of occasions to his wife in Scotland. James’s first letter was written in December 1861, when he lamented the poor political condition in the country and suggested that the time was not right for his wife to join him:

Washington City Dec 20th 61

My dear and affectionate wife I recived your welcom letter of the Second of Oct and nothing gave me more pleasure then to hear that you and my familey is all well and in good health my dear wife I think that you had better not come out to this country for the preasant the times hear at preasant is very troublesom and there is no sine of it getting any better at preasent my dear wife nothing gave me more trouble and sorrow then to hear that you ware in bad health but I hope in gad that by the time this reaches you that it will find you restored to perfect health I am very sorry that the troubles in this country has caused the the trade in Scotland to be so dull as it is my dear wife my advise you would be for to set up some kind of a shop with what money you have at preasent but please yourselfe dear wife give my best respects to Jane Gaston and I hope she wont get married until I go home and to youre sister margaret and my love to agnes mary and thomas if anything should happen me amy sickness or other misfortune you will write to Captain Levi C Bootes of Company G 6th Infantry Give my best respects to all enquiring friends I send my love and kind regards to you my dear and affectionate wife

No more at present I remain your affectionate husband

James Shepard

Co ‘G’ 6th US Infantry

Direct for me James Shepard Company ‘G’ 6th United States Infy Regular Armey Washington City or Elsewhere

[image error]

James’s first 1861 letter to his wife in Scotland (NARA/Fold3)

James decided having finished this letter to write another to his wife on the same day, outlining his journey from the west coast to the east, and containing much fascinating detail:

Washington City Dec 20th [1861]

My dear wife I forgot to tell you something about our voyage from Caliafornia across the pacific and atlantic ocions the trip was one of the finest ever made we had on board about five hundred troopes on board and a large number of citizens we put into mananella a mexican port on the pacific and I believe the convoy is the grandest I have ever seene everything was greene and looked fine it was very hot our next port was Acapulca another mexican port on the pacific it is very beautifull out next stopping place was the Isthmus of darien or the city of panama the oldest city in america here you can buy a monkey for two shillings and a parrot for one shilling all kinds of tropical fruits grows here such as oranges banas plantans coco nuts and such like the distance across the Ismus is 47 miles there is a railroad across it from panama to aspiniwall on the atlantic there is a perpetual spring here all the time it is very hot of our voyage on the atlantic there hapened nothing worthey or remark the distance from panama to San Francisco is 3264 miles and from aspinwall to N. York is 2950 miles so you have a prety good idea of our voyage as we left San Francisco the greatest enthisiasm prevaled canons was fired from all the forts and ships of war in the harbor the inhabitance crowded the quays to suffication the bay was alive with boats full of people waveing their hancherchiffs and chearing us as we moved from the pier of our reception in new york and philadelphia I could not say two mutch in N. York particularly as we paraded the streets to our quarters Chear after chear went up from the patriotic citizens of that loyal city as we passed through philiadelphia we had a fine super prepaired by the inhabitance after dinner the band played hil columbia yankey doodle and the star spangled baner which drew chear after chear from the excited mob and such was the feelings of the people that old men totering on the verge of the grave came to us shook us by the hand and toasted us for to fight for the honor of our flag and country as our fathers did before children scarcely able to lisp the word liberty would run to us with flags in their hands and say god bless the soldiers

My dear wife I forgot to tel you that our pay is raised it is thirteen shillings and three pence per week and we recive 2lbs of beef 24 ounces of bread and an abundance of all these kind of rations we also more clothes then we care ware so that I believe that this is the best armey in the word and I am well contented dear wife I am altogether temperate and I am going for to put ten pounds in the bank pretty soon I send all the children and yourself my love and best respects

I remain your affectionate husband

James Shepard

James died of chronic diarrhea at Eckington Hospital in Washington D.C. on 23rd October 1862. During the course of Elizabeth’s application she included the two letters transribed above as evidence of their relationship. Elizabeth also had friends such as Hugh McLellan and Robert McEwan of the Tylefield Street Factory in Glasgow give evidence on her behalf. She received a pension of $8 per month from 1866.

James’s second 1861 letter, replete with striking patriotic imagery (NARA/Fold3)

Daniel Stewart, Kinning Park, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. United States Navy.Daniel enlisted in the Navy on 5th February 1870, when he was around 25-years-old. He first served as a machinist aboard the USS Vermont and later USS Plymouth. After his first stint in the Navy Daniel appears to have briefly returned home to Scotland, where he married domestic servant Agnes Cunningham at St. Andrews Street in Kilmarnock on 8th August 1873. He was soon back in America, however, where he re-enlisted in 1873 and served on the USS Vermont and USS Ossipee until his discharge on 13th April 1874 on a certificate of disability. The sailor had been injured when his right hand was caught in the machinery aboard the Ossipee on 29th December 1873. It resulted in all his fingers being lacerated and his middle and little fingers broken. Daniel was living at 272 Scotland Street, Kinning Park in Glasgow when he was receiving the monies, consisting of $12 per month. He and Agnes had a number of children, including Margaret (b. 1875), Thomas (b. 1878), James (b. 1880), Daniel (b. 1884), Mary (b. 1886) and Robert (b. 1893). After his time at sea Daniel worked as a brush maker, and in his final years he and Agnes made their home at 30 Broompark Drive, Dennistoun in the city. He died on 6th September 1909 of disease of the mesenteric glands. His widow Agnes sought a pension following his death.

30 Broompark Drive in Dennistoun, the area where Daniel and Agnes Stewart lived.

Agnes Wilson, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. Widow of Archibald Wilson, 25th Connecticut Infantry.

Archibald Wilson and Agnes Buchanan were married on 9th December 1849 in the City of Glasgow by the Reverend McFarlane. At the time Archibald worked as a glass cutter. Their son William was born at 78 Stockwell Street in Glasgow on 6th October 1850, while their daughter was born after emigration to America, coming into the world at Winter Street in East Cambridge, Massachusetts on 24th November 1853. Archibald enlisted on 9th October 1862 and was mustered in to Company A of the 25th Connecticut on 11th November. He was killed in action at Port Hudson, Louisiana on 28th May 1863. Returning to Scotland, Agnes claimed a pension of $8 per month from September 1864. She died on 30th May 1891.

James D. Wilson, Glasgow, Lanarkshire. 82nd New York Infantry.

James served in Company I of the 82nd New York Infantry (2nd New York State Militia). He was 30 years-old when he enlisted on 3rd July 1861. He was wounded in action in the first major battle of the war, at Bull Run, Virginia on 21st July 1861 and discharged for disability on 10th November 1861 at Poolesville, Virginia. He was granted a pension of $18 per month for an injury to his right hand, with the application approved in April 1863.

Elizabeth Burgess, Kinghorn, Fife. Widow of John Burgess, 79th New York Infantry.

John Burgess and Elizabeth Simpson were married in Kinghorn on 2nd January 1843. On 28th May 1861, at the age of 37, John enlisted in the 79th New York, a unit with a Scottish identity, becoming a private in Company K. He was promoted to corporal but subsequently returned to the ranks. He was killed in action at Knoxville, Tennessee on 29th November 1863. John appears to have adopted the name Dan Driskcoll to marry a woman called Elizabeth Collins in New York on 4th March 1853, thereby becoming a bigamist. John’s second wife claimed a widow’s pension until 1872- stating in her application that Dan Driskcoll was his real name, and that John Burgess was an alias. Back in Scotland, John’s first wife Elizabeth successfully applied for a pension based on the service of the husband who had deserted her. She received $8 per month from 1870 until she died at 8 George Street in Leith on 26th October 1902.

Letter written to the U.S. Pension Agency from 8 George St., Leith by Charlotte Burgess informing them that her mother had died (NARA/Fold3)

Mary A Borland, Leith, Midlothian. Widow of John Borland, 17th United States Infantry.John Borland, a clerk living at 18 Salisbury Street in Edinburgh and Mary A Allen were married in the Parish Church of St. Cuthbert, Edinburgh on 30th April 1838. John enlisted on 7th March 1862 in Company H of the 17th U.S. Infantry, and died of pneumonia in Convalescent Camp in Alexandria, Virginia on 20th December 1862. Mary first applied for the pension in Portland, Maine. She received $8 a month from 1863.

The grave of Edinburgh native John Borland at Alexandria National Cemetery in Virginia (Cryptogram/FindAGrave)

Elizabeth McPherson, Montrose, Angus. Widow of William McPherson, 14th New York Heavy Artillery.William McPherson and Elizabeth Rioch were married on 24th February 1860 in the MacNab Street Presbyterian Church in Hamilton, Canada. Their son Hugh was born on 7th June 1861 in Sullivan Township, Gray County, Canada. William was enlisted in the 14th New York Heavy Artillery on 15th October 1863 and mustered into Company F. Captured near The Wilderness, Virginia on 8th May, he died on 30th August 1864 as a Prisoner of War in Andersonville, Georgia, from scorbutus. Elizabeth first applied for a pension from Hamilton in what is now Ontario, Canada. She was approved in May 1867 and received $8 per month.

The McNab Street Presbyterian Church in Hamilton where William and Elizabeth were married.

Neil Lucas, Oban, Argyll & Bute. 179th New York Infantry.

Neil was a 39-year-old ship carpenter when he enlisted on 13th April 1864 at Stillwater. He was initially mustered in as a private in Company A of the 180th New York Infantry but was quickly transferred to Company G of the 179th New York on 23rd July 1864. He was absent sick at the muster out of the regiment. He successfully applied for a pension of $8 per month from October 1866, awarded due to an abscess in his right breast.

Catharine Breckinridge, Paisley, Renfrewshire. Widow of Walter Breckinridge, 73rd Pennsylvania Infantry.

Walter Breckinridge (sometimes Brackenridge) and Catharine Pollock were married in Paisley’s High Church Parish on 22nd June 1832. Walter was therefore not a young man (probably in his 50s) when he enlisted. He initially joined the 66th Pennsylvania but was transferred to the 73rd and enrolled in Company K on 25th July 1861. Taken prisoner at The Wilderness on 8th May 1864, he died at Andersonville, Georgia as a Prisoner of War on 24th August of diarrhoea. Catharine was 60-years-old when she applied for the pension in 1865 from Underwood Mill in Paisley. Catharine received a pension of $8 per month from April 1875.

Bridget Wallace, Paisley, Renfrewshire. Widow of Michael Wallace, 4th United States Artillery.

Bridget’s husband Michael is likely the Michael Wallace who enlisted in New York on 4th May 1871. The 24-year-old was not a native of Scotland, but of Limerick in Ireland. He was described as having auburn hair, a ruddy complexion and being 5 feet 11 inches in height. A member of Company K of the 4th U.S. Artillery, he was killed on 26th April 1873 at the Battle of Sand Butte in California’s Lava Beds during an engagement with Modoc warriors led by the Chief known as Scarface Charley. Bridget received $8 a month from November 1874.

The bodies of slain soldiers being recovered during the Modoc War in 1873 (Harper’s Weekly)

William Connelly, Scotland. United States Marine Corps.William served as a private in the United States Marine Corps aboard USS State of Georgia. He was in receipt of $3 per month for the loss of his right finger. It was not recorded where in Scotland he lived.

Ellen McDonald, Scotland. Widow of Allan McDonald, United States Medical Department.

Allan McDonald, a worsted spinner, and Ellen Wiseman, a dressmaker, were married on 28th July 1852 in Barnsley, Lancaster, England when both were 25-years-old. Among their children were twins Colin and Eliza (b. 1855), Donald (b. 1856), Roderick (b. 1858), Reginald (b. 1860) and James (b. 1866). Allan was a Hospital Steward, having enlisted in D.C. on 6th December 1866. He died on 9th March 1869 0f Erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection. She initially applied for her pension in Washington D.C. and was award $8 per month from 1869. Ellen died on 26th February 1891. It was not recorded where in Scotland she received the payments.

James Cusiter, Stromness, Orkney. United States Navy.

The James Cusiter in receipt of a pension of $3 per month in Stromness was likely the 30-year-old man who enlisted in New York on 21st September 1859 as a Seaman for a period of 4 years. He had blue eyes, brown hair and a light complexion and was 5 feet 8 inches in height.

Stromness, where James Cusiter collected his American pension- the most northerly U.S. pensioner in Scotland (Dorcas Sinclair)

ReferencesA wide range of references were utilised in constructing the details above, including the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll, Civil War Widow’s Pension Files, Navy Widow’s Certificates, Navy Survivor’s Certificates, Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns, Regular Army Enlistments Returns, Pension Index Cards, Numerical Pension Index, Regimental Rosters, New York Muster Rolls and Regimental Histories. If any readers wish to receive specific references for any of the individuals covered above please contact me.

Filed under: Pension Files, Scotland Tagged: 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll, Civil War Pensioners, Irish American Civil War, Scotland American Civil War, Scotland Emigration, Scots in America, Scottish Diaspora, Scottish Widows Pension

February 19, 2017