Damian Shiels's Blog, page 27

February 1, 2017

An Appeal for Civil War Descendants

I have been involved of late in assisting Mind the Gap films here in Ireland with a proposal to examine the Irish of the American Civil War, particularly with information in the pension files. Mind the Gap are eager to hear from descendants of Irish emigrants who served during the conflict, and have asked me to share the appeal below. If you have anything you think would be of interest please email Fran at Mind the Gap (her email is below), and feel free to share!

Mind the Gap Films is developing a documentary about the personal experiences of Irish men who served in the American Civil War, for broadcast on RTÉ. We’re looking for descendants who have letters, photographs or any personal effects belonging to ancestors who were involved in the conflict and who might like to share their stories. We will be filming in Ireland and the eastern US and would be delighted to hear from people who are interested. Please email fran@mindthegapfilms.com. Mind the Gap Films is an independent television production company and you can find out more about us here www.mindthegapfilms.com

Filed under: Events Tagged: Civil War Descendants, Civil War Documentary, Civil War Letters, Irish American Civil War, Mind the Gap Films, Television Documentary

January 28, 2017

“My Cousin told me…that all my family were in America”: A Search for 1860s Cork Emigrants

The widows and dependent pension files often give us an extraordinary insight into 19th century emigration. Occasionally these are from the perspectives of those who remained in Ireland. I recently came across just such a letter, written in late 1863 by Dan McCarthy in Cork to his brother Ted in America. Its detail reveals just how cruel– and unexpected– the separation of families could be. Dan, who had been working out of Ireland for a few years (possibly at sea), returned home to discover that his entire family had emigrated. He had little information on them, and wrote to Ted to see could he find out something about their whereabouts and circumstances. Unfortunately, although we can see what he had to say, his brother Ted would never have the opportunity to read it.

[image error]

Cork Harbour as it appeared in the early 1870s (Library of Congress)

Cork, October 5th 1863

My Dear and loving Brother

I beg the liberty of respectfully writing to you to let you know that I landed in Cork in May last two years thinking to see father mother brothers and sister Johanna knowing that Mary Anne and Margaret were in America.

I must here say that my cousin Edmond Murphy told me that all my family were in America and that they sent Johanna off themselves and that my father came from America and that he was a shocking man for cursing and speaking bad words.

However it was not long until my poor father herd that I was in Cork and he came to see me we had a fouter together and I wanted from him my poor mother’s directions or any of your’s directions but he told me that he did not know where to write himself for that he wrote to you and that the letter was sent back to him and that he felt very uneasy about you that he was sure that something was the matter with his poor son or that he would have a reliefe before then as that he received five pound from you not long before– he spoke more of Mary Anne than all the rest.

He told me that Margaret married against his consent and that he had a man of his own choosing and that she would not look at him.

My Dear Brother I realy believe that my poor father was not right in his head he was as deaf as a stone and you should write down whatever you had to say to him. I never could get the slightest knowledge from him of any of ye he told me once that my mother was full of money that she with a Duch man a very rich gentleman he only stoped a week with me and went off to Carbery he came back again and worked a few weeks in Cork he went off to Crookstown was there a few days and he asked them to send him to his sister to Dunmanway they did so he did not feel well they never wrote to me to let me know that my poor father was ill. I got ready myself and went off to Skibbereen on the West Cork Railway to work in order to be a near him and to do all I could for him. To my surprise Don Carthy the mason told me that my father was dead and buried the day before. I passed my Aunt’s door twice since and would not call. She herd I did so and was surprised at me. I met her son Timothy he was at sea for the last ten years and came home full Captain of a merchant vessel full of money he asked me why I passed my Aunt that was his mother and the he was my first Cousin.

I told him that it was very wrong that she did not let me know that my poor father was ill that I may have the pleasure of weeping over his body as all the rest of my loving family were far away from me. She told me that she had no thoughts that he was so bad and that she had not my directions and that if she had that she might not do so as they little expected that he was so near death. I beg dear Mother to say that he was well cared for and had the Priest and Doctor with the help of God may God rest his soul and the souls of all our family not forgetting the souls of the faithful departed may they rest in peace.

Dear Brother I was told that you maid an inquiry for me to Cousin Ted + in Killarney I wrote to him and he answered my letter by return of post and mentioned to me that he received a joint letter from you and his sister and he sent me your part enclosed in the letter. My loving Tead I am double the man to be able to write to you to know all of my poor mother and brothers and sisters and Dear Tead it is long since your brother Dan shed so much as he did when I red in your letter that you lost a leg for my poor father told me that there were not many in New York able to take a round out of you and that you were a first class brick layer.

My Dear Brother I do not know what to write in this nor shall I be at rest until I receive a letter from you with a full account of my poor loving good mother brothers and sisters and I trust in god that you are not broken hearted for the loss of the leg and that it may not come again you until I see you and ye all I trust that you will keep your spirits up for if I was to swim across that is if I could not go otherwise I shall do all I can to see ye all before long please God. (1)

[image error]

A soldier of the 37th New York Infantry (Library of Congress)

Dan’s letter contains lots of interesting detail. Aside from what it tells us about emigration and the potential for families to be broken apart as a result of it, there is interesting social detail, for example the unsuccessful efforts of Dan’s father to arrange a match for his daughter (and indeed his use of foul language!). The pension file also allows us to piece together something of the McCarthy story. Dan was fortunate that his father was in Co. Cork at all, as he had also emigrated to America with the rest. He had been plying his trade as a mason in New York in the 1850s when he fell from a building and was severely injured. Unable to work, the physician advised him to return to Ireland for the sake of his health. Leaving his wife and children behind, he had retraced his steps back to Cork, where he would later be reunited with his son Dan– though he would never see the family he left behind in the United States again. (2)

The return home of Dan’s father meant that his mother Johanna depended on two other adult sons for support, Justin and Ted. Justin died in the late 1850s, making Johanna solely reliant on Ted. Ted (the intended recipient of the letter) had enlisted as a 25-year-old on 25th May 1861 in the 37th New York ‘Irish Rifles.’ He eventually rose to the rank of Sergeant in Company K, a position he held at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia on 31st May 1862. There he was shot in the right knee and left on the field. He was briefly captured by Confederate forces, but refused amputation and was left for dead. Some comrades recovered him on 1st June and brought him into Union lines where the leg was removed. Ted survived this procedure and was officially mustered out with the rest of his regiment, joining Company 26 of the 2nd Battalion, Veteran Reserve Corps. However, the effects of his wound followed him. In late 1863 he became gravely ill and was hospitalised, ultimately passing away at the General Hospital at Fort Schuyler, New York on 8th September 1863 of “paralysis” brought on by amputation. By the time Dan sat down in Cork to pen his letter to Ted, his brother had already been dead for nearly a month. (3)

[image error]

Burying the dead after the Battle of Fair Oaks (Library of Congress)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) McCarthy Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid., Roster, Muster Roll Abstracts;

References & Further Reading

Widow’s Certificate 73970. File of Johanna McCarthy, dependent mother of Timothy McCarthy, 26th Company, 2nd Battalion, VRC.

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 37th New York Infantry.

New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts.

Civil War Trust Fair Oaks/Seven Pines Page.

Filed under: 37th New York, Battle of Fair Oaks, Cork Tagged: 37th New York Irish Rifles, Amputation, Battle of Fair Oaks, Cork Emigrants, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Veteran Reserve Corps, West Cork Railway

January 22, 2017

Forgotten Irish Booklaunch, Hodges Figgis, 26th January

I am delighted to announce that the official Irish launch of The Forgotten Irish: Irish Emigrant Experiences in America will take place in Ireland’s oldest bookshop, Hodges Figgis of Dublin, on Thursday next 26th January at 6pm. The publication will be officially launched by Dr. Myles Dungan of the RTE History Show, who has himself been a trailblazer in popularising the experiences of the Irish in America. This book, which tells the stories of 35 different 19th century Irish emigrant families, has been a particular labour of love for me. Each story is founded on information contained within the Widows and Dependent Pension Files of Civil War soldiers, which I believe is the greatest repository of social information on the experiences of 19th century Irish emigrant families that exists anywhere in the world. The publication seeks to follow some of these families in both Ireland and America in the years before, during and after the war that caused the files to be created. To get a flavour of what it contains, see this post. The launch is open to all, so I hope some of you will be available to attend with me. For those readers in the United States, the book is being released across the water in May next, with plans for a March launch in Washington DC currently taking shape- I will keep you up to date on developments in the coming weeks![image error]

Filed under: Book, Update Tagged: Book Launch, Damian Shiels, Forgotten Irish, History Press, Hodges Figgis, Irish American Civil War, Myles Dungan, National Archives

January 6, 2017

The Distant Past? Ireland’s American Civil War Grandchildren

I have had the good fortune to deliver dozens of lectures around Ireland discussing local connections to the American Civil War. Wherever I am, I always highlight two factors; the reality that for many Irish counties, the American Civil War saw more locals in military uniform than any other conflict in their history, and the fact that these connections are not as distant as we might think. Nothing has brought that home to me more than three men I have met in recent years– Seamus Condon in Dublin, and Davy Power and Jack Lynch in Cork. All have something in common, as each has a forebear who fought in the American Civil War. However, unlike many with a connection to the conflict, their association is not third, fourth or fifth generation. In each case, the individual who served between 1861 and 1865 was their grandfather. There is surely no greater demonstration of just how close to us in history this major event in the story of the Irish diaspora is.

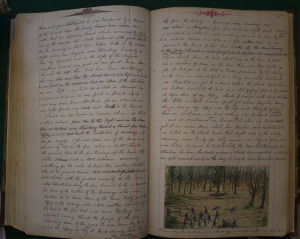

[image error]

Seamus Condon with the handwritten and hand-illustrated memoirs of his grandfather, Andrew J. Byrne, 65th New York Infantry (Damian Shiels)

Seamus Condon- grandson of Andrew J. Byrne, 65th New York Infantry

I met Seamus Condon in his home in Dublin. Seamus is himself a former soldier, having served as an officer in the Irish Army, experiencing United Nations service in the Congo. Seamus is the caretaker of a remarkable collection of material relating to his grandfather, Andrew J. Byrne. Andrew first arrived in New Orleans in 1849. It wasn’t long before he enlisted in the United States Army. Unlike many of his fellow emigrants he decided to return home, and after four years he decided to desert and travel back to Ireland. However by 1856 he was back in New York, having re-enlisted and confessed to his previous desertion. Returned to his unit, his pre-war adventures took in locations such as New Mexico, Texas and Arizona. On the expiration of his term of service in 1860 Andrew once again went home to Ireland, but hastened back to the Union’s defence on the outbreak of the Civil War. He enlisted in the 65th New York Infantry, otherwise known as the 1st U.S. Chausseurs. First Sergeant Byrne fought through the Peninsula Campaign and was seriously wounded at Malvern Hill, where he was captured by the Confederates and confined in Richmond’s Libby Prison. Eventually exchanged, Andrew returned to his unit in late 1863 and served during the Overland Campaign and in Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, where the Dubliner was wounded for a second time at Cedar Creek. He ended the war as a First Lieutenant. A member of the Fenian movement, Andrew was one of those who returned to Ireland after the war and was arrested on suspicion of plotting a rebellion (you can see his Fenian mugshot here). He was sent back to America, where he once again enlisted in the regular army.

Andrew eventually returned to Ireland permanently in 1875, living out his life in his home city and being buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. A keen writer and artist, Andrew wrote and illustrated his American experiences for his family, and Seamus continues to care for this remarkable manuscript and other possessions relating to his grandfather’s service. The manuscript was published on a limited basis through Original Writing in 2008 (you can read a review of it here). Seamus is eager to have this remarkable story made available to a wider audience both in Ireland and the United States, and would be keen to hear from anyone who might be interested in publishing this work in America.

[image error]

Davy Power, whose grandfather James served on the USS Katahdin during the Civil War (Damian Shiels)

Davy Power– grandson of James Power, USS Katahdin

I met Davy Power in Castletownbere, West Cork, when delivering a lecture on West Cork people in the American Civil War to the Beara Historical Society. Davy was aware that his grandfather James Power had served in Union forces, and even recalled a photograph of him in the family home. It transpired that James had served aboard three Union vessels during the Civil War- USS Vermont, USS Katahdin and USS Dacotah. James described his service in a letter the pension commissioners in 1891:

I enlisted in the United States Naval Service on 18th January 1861 in Boston and was ordered on board the “Katadin” as Coal Heaver. Subsequently I was employed as Fireman. I believe the ship was commanded by Captain Johnson. The “Katadin” was ordered to Key West and thence to the Mississippi. I was engaged in the attacks and captures of Forts Jackson, Philip and Hudson and after the hardships endured I was sent to Hospital under the care of I believe Dr. Bragg in New Orleans. I resumed duty after a short time on board the “Katadin” and we were ordered to the coast of Texas off Galveston to keep a strict blockade on the coast. I was employed there for more than a year. Subsequently I was discharged and later on received some prize money.

Joined the “Dacotah” in New York 3rd April 1865 as fireman and was ordered to the South Pacific and after about three years got an honourable discharge from the ship. My constitution was so much impaired in the service that I came to Ireland.

James’s service aboard the USS Katahdin was the most notable of his wartime career. He participated in the Battle of Forts Jackson & St. Philip which opened the way for the capture of New Orleans. The prize money he received was due to his ship’s part in the capture of Confederate blockade runners Hanover, Excelsior and Albert Edward. After his return home, James established a shop in Castletownbere, and married Johanna Murphy there in 1872. Johanna lived until well into the 20th century.

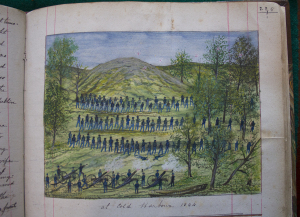

[image error]

Jack Lynch (left) and his family in The Cotton Ball, the bar established by his grandfather Humphrey, a veteran of the 4th U.S. Artillery in the Civil War (Irish Examiner)

Jack Lynch– grandson of Humphrey Lynch, Battery H & I, 4th United States Artillery

I have met Jack Lynch on a number of occasions in the pub which his grandfather established, The Cotton Ball, in Mayfield, Cork. Jack’s grandfather Humphrey enlisted in Boston on 19th March 1862 when he was described as a 5 foot 8 inch 21-year-old with blue eyes, light hair and a ruddy complexion. He was by occupation a gardener. Humphrey and Battery H served in the war’s Western Theater, and was heavily engaged at battles such Stones River and Chickamauga. Many of the men were transferred to Battery I in October 1864 while based at Nashville, and went to fight at locations such as Charlotte’s Pike and Pulaski before participating in Wilson’s Raid through Alabama in 1865. Humphrey was discharged when his term of enlistment ended on 19th March 1865, at Chickasaw Landing, Alabama. After the war, he returned to Massachusetts, where he embarked on a highly successful career dealing in cotton.

Humphrey’s success in America allowed him to return home to Ireland, where he was able to become a landowner and ultimately establish the pub, now named for the fibre which helped to create his wealth. It still contains many mementos of Humphrey’s time in America. The successful emigrant also named his new Cork property Byfield in honour of the Massachusetts location that had given him so much. This part of Mayfield retains the name Byfield today- a rare occasion where an American placename has inspired the creation of an Irish placename, rather than vice-versa.I n recent years The Cotton Ball has established a brewing company, producing a number of (in my opinion!) very fine craft beers. Each bottle pays tribute to the man who made it all possible, bearing an image of American Civil War veteran Humphrey on the label. You can read more about it here.

Humphrey occasionally returned to visit the United States after settling in Ireland. On one visit the Brockton Times recorded the event, publishing the account in its 8th September 1904 edition:

FROM IRELAND

Mr. and Mrs. Humphrey J. Lynch of Cork Visiting Here.

Mr. and Mrs. Humphrey J. Lynch of Byfield House, Mayfield, Cork, Ireland, are guests of Mr. Lynch’s cousin, Cornelius Hallissy of 486 Warren avenue. They will remain in this city about 10 days, then leaving for the Louisiana Purchase exposition. They came here from Newburyport, where they were entertained by Mr. Lynch’s brother, Denis Lynch of Warren street. Mr. Lynch has scores of acquanitances and relatives in Brockton and in all the towns in this vicinity. He and his wife have been warmly greeted and hospitably entertained.

Mr. Lynch was born in Cork, Ireland, and came to America when he was 15 years old. He went at once to Byfield, the little Essex county town which he has remembered in naming his present home estate. He found employment on the model farm of Joseph Longfellow, cousin of the famous poet, who was a frequent visitor there. “I believe that I owe all my success in later life,” said Mr. Lynch, “to the lessons I learned from Mr. Longfellow, my employer.”

He was there for two years, and then worked a year in the ship yard of Chas. Currier of Newburyport. He was there when the civil war broke out. he was one of the first to enlist and the last to be discharged. He went in as a private of the 4th U.S. artillery, and came out a sergeant. Of the 208 men who enlisted when he did there were only three of the original ones left when the battery was mustered out. He served through 27 general engagements, principally in the army of the southwest along the Mississippi valley. He was in many smaller fights and skirmishes.

After the war he worked 14 years as a foreman of the picker room in a Newburyport cotton mill, and then his wife’s health failed and it seemed best to return to Ireland to live. He took with him his modest savings, entered the real estate business, and amassed a considerable fortune. He has now retired.

He came to this country to meet his old comrades at the Grand Army national encampment in Boston. He is a member of Lawrence post, 66, of Medford. He met companions of this post and members of his old battery, but none of those who enlisted with him at the outbreak of the war.

“I am 20 years younger for this visit,” he says. “There is a bond between men who fought in the civil war closer than that which unites brothers. We endured hunger, thirst, fighting and blood together.”

After his visit with Brockton relatives and after seeing the world’s fair, he will visit a number of his old battlefields. He speaks in highest terms of the Brockton Grand Army veterans. He has been cordially welcomed at their hall, and shown courteous treatment by all of them whom he has met.

Seamus Condon, Davy Power and Jack Lynch all have extremely close connections to the American Civil War, and each rightly remembers this association with great pride. They are living proof that at least some emigrants did come home to live out their lives in Ireland. Given how few did make the return journey, it is remarkable that at least three grandchildren of such veterans can still be found today. It seems likely that in the United States hundreds– if not thousands– of grandchildren of Irish American Civil War veterans remain. Each is a reminder to us in the 21st century of how close the 1860s can be. If you know of any other Civil War grandchildren in Ireland, or indeed the United States, I would be very interested in hearing from you.

References

James Power Navy Widow’s Certificate 11147.

U.S. Register of Enlistments.

Brockton Times 8th September 1904.

Filed under: Cork, Dublin, Research Tagged: 4th US Artillery, 65th New York Infantry, Andrew Byrne Fenian, Byfield Cork, Cotton Ball Pub, Humphrey Lynch, Irish American Civil War, USS Katahdin

January 3, 2017

North Carolina Slave, Union Widow, Liberian Emigrant: The Journey of Nancy Askie

My interest in the remarkable information contained within the widows and dependent pension files extends well beyond just those claims associated with Irish-Americans. The files are of major importance for the study of all immigrant groups, as well as native-born Americans. However, there is one category of pensioners for which the files are undeniably more significant than any other, given the paucity of information often otherwise available– the claims of former slaves and their families. Continuing our occasional look at non-Irish pensions (see for example this post, focusing on the Scottish experience), I have decided to examine a pension relating to a woman and her family whose emigration journey took them not from Europe to the United States, but from the United States to Africa. Her name was Nancy Askie (Askew), and in 1883 she was the only person claiming a United States military pension in Liberia. (1)

The value of the pension files for unearthing social history relating to former slaves was highlighted by Elizabeth A. Regosin and Donald R. Shaffer in their excellent 2008 work, Voices of Emancipation: Understanding Slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction through the U.S. Pension Bureau Files. The case of Nancy Askie offers a fine example of how the files can be used to assist in piecing together the story of one family of former slaves.

An African-American soldier photographed with his wife and daughters (Library of Congress)

Prior to the Civil War, Nancy was most likely a slave in the ownership of Andrew Jackson Askew, a physician and farmer in Bertie County, North Carolina. Askew appears to have been active in Democrat Party circles; a newspaper report from 1839 records an Andrew J. Askew as Secretary at a meeting of the Democratic Republicans of Hertford County, where those assembled passed a number of resolutions in support of the re-election of President Martin Van Buren. One of their stated reasons for supporting Van Buren was “because he is opposed to the agitation of the slave question, and has given a pledge to veto any bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia.” Askew was also involved in religious activities, and was Secretary of the Chowan Bible Society in 1845. The slave owner is recorded as a 33-year-old physician on the 1850 Federal Census for Bertie County, with real estate valued at $4,000. He lived there with his wife, four young children and two other whites. The latter included 23-year-old George Askew, who was an Overseer of the farm, which according to the 1850 Slave Schedules contained 37 slaves. As with all the Slave Schedules, no names were provided. By the time of the 1860 Census Andrew J. Askew’s family had expanded, and he was recorded as having real estate valued at $3,500 and a personal estate of $41,530. He had also increased his slave ownership, now counting 44 slaves among his property. (2)We can only piece together something of Nancy’s story as a result of her widow’s pension file. As a result, the names of a number of those unnamed slaves who were likely connected with the farm of Andrew J. Askew in Bertie County are revealed to us. Nancy was married to another slave, George, on or around the 15th December 1843 at the Askew Farm, when she was most probably in her 20s. It is not entirely clear if both Nancy and George were owned by Askew, or if one of them was the property of a neighbour or relative. Two other slaves, who may also have worked the Askew farm– Winifred Eason and Harriet Linsay– recalled that “being slaves, they were not allowed to marry by any form or ceremony, only by their mutually consenting to live and cohabit together as man and wife.” Winifred and Harriet had helped Nancy through the birth of her children– the couple may have had as many as 12, at least 3 of whom died in infancy. Those who survived included Celia (born c. 1846), Caroline (born c. 1848), Rachel (born 2nd July 1852), George (born 11th September 1853), Chaney (born 20th December 1854), Alfred (born 4th April 1858) and Simon (born 12th December 1861). These children are also potentially among those recorded, unnamed, on the 1860 Slave Schedule. The American Civil War brought opportunity for the slaves of North Carolina, and Nancy’s husband George decided to grasp it. Taking advantage of the proximity of Union troops, on 6th January 1864 he enlisted at Plymouth, North Carolina in the 3rd North Carolina Colored Volunteer Infantry, otherwise known as the 37th Regiment, United States Colored Troops. George, like many other ex-slaves, used the name of his former master on his enlistment, signing on as “George Askie.” Askie or Askew would be the surname that George, Nancy and their children would continue to be known by into the future. (3)

The 1860 Slave Schedule listing the slaves of Andrew Jackson Askew, starting midway down the left-hand column, which may contain Nancy and her children (Fold3/NARA)

George was described as a 40-year-old, 5 feet 6 inch farmer when he joined up. He was far from the only former Bertie County slave in the 37th USCT. As many as eleven men served under the name Askie in Company C of the regiment, all likely former slaves of Andrew J. Askie or one of his relatives. Three of the other Askies in Company C– Bryant, Henry and Thomas– would later say that they had known Nancy since the early 1840s and all the couple’s children since birth, further raising the probability that a number of Andrew Askie’s ex-slaves had enlisted together. Among the other Bertie County men in the regiment who would later claim to have known the couple were Thomas Freeman (four men of the regiment chose to serve using the surname “Freeman”) and Silas Miller. George and his comrades in the 37th USCT ultimately became part of the 18th Army Corps, Army of the James. Their impressive service saw them engaged during the Siege of Petersburg, as well as at locations such as New Market Heights, Fair Oaks and Fort Fisher before the close of the war. George survived it all, living to see the official emancipation of his family. He was able to visit them on furlough in Bertie County in 1866, prior to returning to his unit to see out his final few months service. On 4th January 1867– only two days shy of the end of his three-year term of enlistment– George was among a group of troops transporting timber for barrack construction by boat between Fort Sumter and Castle Pinckney in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The seas were rough, and during the passage both he and one of his comrades, a soldier called McCabe, were washed overboard. McCabe was a strong swimmer, and made it back to the boat. Unfortunately, George was not. He lost his life when within touching distance of a return to his family. (4)The news must have been a severe blow to Nancy and her still dependent children back in North Carolina. She was living in Windsor when she applied for her widow’s pension, which was eventually granted. As was often the case for former slaves, she had some difficulty in proving her claim– among the steps she had to take was to have a physician examine her younger children to assess if they were under the age of 16, as they had no proper birth records due to their bondage. Despite emancipation, the immediate post-war period brought significant challenges for Nancy and other members of the emancipated African-American community. Black Codes were instituted which included a provision for African-American children to be “apprenticed”, with former masters given first preference. Republican ascendancy in the State in 1868 in the wake of black enfranchisement saw the worst of the Codes abolished, but there was a commensurate rise in the activity of the Ku Klux Klan, who perpetrated widespread violence against the African-American community. Against this backdrop, a number of Bertie County blacks turned to the American Colonization Society (ACS) for assistance. Established in 1816, the ACS, or “The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America”, was a controversial group that advocated the settlement of African-Americans on the African continent. One of their aims in undertaking this was that a “homogeneous population of white men will one day prevail in America.” The ACS had assisted with the foundation of the colony of Liberia (latin for “Land of the Free”) in the 1820s, where by the late 1860s many thousands of African-Americans had settled. (5)

Native African boys who were being educated in the Christian School in Arthington, Liberia (Library of Congress)

African-Americans in Bertie County were not the only ones who sought an escape from the racism and poverty they endured in the immediate post-war era. The ACS had sufficient interest in their scheme to purchase the vessel Golconda in 1866, a ship capable of transporting 600 emigrants at a time. From May 1867 to May 1868 she carried over 1,000 African-American migrants from various states to Liberia. Despite the interest, many African-Americans in Bertie were suspicious of the ACS motivations, with some concerned they would be sold into Cuban slavery, or that it was a scheme to remove Republican voters in order to restore Democrat control in North Carolina. Nonetheless, dozens remained keen on starting a new life across the Atlantic. On 5th November 1869 a total of 79 African-Americans from Bertie set off on the first leg of their journey to Liberia, joined by blacks from a number of other states. Among the group were five people bearing the surname Askew– Henry (27), Anika (20), Mary Jane (1), Andrew (22) and Rachel (17)– all likely known to Nancy if not related to her (it is possible Rachel was Nancy’s daughter). The Bertie settlers were known as the “Arthington Company” and were bound for the Liberian interior and a new settlement on St. Paul’s River funded by British philanthropist Robert Arthington, and named for him. Those who made their new homes there were, according to Arthington, to consist “as much as possible of men of Missionary spirit, and deeply and prayerfully interested in the moral redemption of all Africa.” (6)The 1869 emigrants were not the last Bertie County African-Americans to leave for Liberia. The fifth and final trip of the Golconda to Liberia occurred in 1870, when she took 196 North Carolinian’s across the sea, including 112 from Bertie County bound for Arthington. The journal of the ACS, The African Repository, published the names of those who had decided to make the journey in that year’s edition. Among them were Nancy (recorded as a 60-year-old Baptist), her 28-year-old daughter Caroline, 17-year-old son George, 16-year-old son Cheney, 14-year-old son Alfred and 8-year-old son Simon. They were among the 25 Bertie residents with the surname Askew who headed for Africa. Among the others was the former comrade of Nancy’s husband in the 37th USCT, Bryant Askew. (7)

Nancy and her children recorded as taking passage to Liberia in 1870, listed from No.37 to No. 42 (The African Repository)

Life was undoubtedly tough in the early years for the Askews and other members of the Arthington Company. The African Repository published correspondence from the initial settlers, led by Alonzo Hoggard, dated 19th May 1870, which has something of an air of propaganda to it:ARTHINGTON, ST. PAUL’S RIVER, May 19, 1870

DEAR SIR: We take much pleasure in writing you this letter, to inform you that all our company are now up at this new settlement, and, with the exception of chills occasionally, are well and doing well, and are much pleased with our location and prospects. All of our company are now living, with the exception of three– two of whom were children, and one grown person, who was sick before leaving the United States. We are now in our houses. This is the only place for the black man to live in. Send us all the hard-working men you can. We want such men as cleared up the fields in the South. We have under cultivation, rice, peas, potatoes, corn, eddoes, cassadas, ginger, fig and arrow root. Every family is well satisfied.

Alonzo Hoggard, Henry Reynolds, Solomon York, York Outlaw, Andrew Askew, Washington York, Benjamin Askew, Frederick Hoggard, Jonas Outlaw, Peter Sutton, Henry Askew, Blunt Hoggard. (8)

Nancy and her children succeeded for making a life for themselves in Liberia. Whether they would have ever travelled there had George not drowned in Charleston Harbor is impossible to know. When she first went to Africa, Nancy did not realise she could continue to claim her pension. As a result it lapsed until 1875, when she applied for its continuation. Former slaves like Bryant Askew and Nancy Rainey who had known her for over 30 years and now lived with her in Liberia gave statements on her behalf, as did some later emigrants to Arthington from South Carolina. Despite the fact that a number of veterans and dependents of USCT troops had left for Liberia in the immediate post-war years, Nancy was the only one claiming a pension there in 1883. She continued to do so until her death in Arthington on 27th June 1893. Her story, only possible to glimpse due to the existence of her pension file, allows us to follow the experiences of one small group of African-Americans. It allows us to follow them from their lives as slaves on the Askew farm, into the tumultuous period of the Civil War and its aftermath, and ultimately to emigration from Windsor to a new life in Liberia, where many of the family’s descendants are likely still to be found. (9)

Arthington, Liberia as it appears today (via Google Maps)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Pensioners on the Roll, 617 (Nancy’s surname is recorded as Askin in the list); (2) Weekly Standard 1839, Biblical Recorder 1845, 1850 Census, 1850 Slave Schedules, 1860 Census, 1860 Slave Schedules; (3) Nancy Askie Pension File; (4) Ibid., Service Records, Index to Records, NPS United States Colored Troops 27th Regiment; (5) Clegg III 2004: 251-253; (6) Clegg III 2004: 253-254, African Repository 1869: 268; (7) Clegg III 2004: 255, African Repository 1870: 373; (8) African Repository 1870: 258; (9) Nancy Askie Pension File;

References

The Weekly Standard, Raleigh, 17th April 1839.

The Biblical Recorder, Raleigh, 5th July 1845.

1850 Federal Census, Bertie County, North Carolina.

1860 Federal Census, Bertie County, North Carolina.

1850 Slave Schedules, Bertie County, North Carolina.

1860 Slave Schedules, Bertie County, North Carolina.

WC117272, Certificate of Nancy Askie, Widow of George Askie, Company C, 37th USCT.

37th US Colored Infantry Service Records.

Government Printing Office 1883. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883. Volume 5.

American Colonization Society 1869. The African Repository, Volume XLV.

American Colonization Society 1870. The African Repository, Volume XLVI.

Clegg III, Claude A. 2004. The Price of Liberty: African Americans and the Making of Liberia

37th Regiment, USCT, Index to Records

NPS: United States Colored Troops 37th Regiment Infantry

Filed under: African Americans, Pension Files Tagged: 37th USCT, African Repository, American Colonization Society, Arthington Liberia, Bertie North Carolina, Irish American Civil War, Liberian Settlement, North Carolina Slaves

December 29, 2016

Fairies, Púca & New Year’s Eve: An 1860s Irish Folktale for Irish-Americans

Tales of mythological creatures like fairies and púca remained popular in Ireland well into the 20th century. Many 19th century Irish emigrants carried a strong tradition of these stories with them to the United States. Traditional storytellers, the seanchaidhthe, kept these legends alive in the community, and many Irish-Americans remained eager to hear them even after their arrival in their new home. Evidence for this can be readily found in contemporary writings, such as the stories published in diaspora newspapers like the New York Irish-American Weekly. To give a flavour of both this tradition of storytelling and one of the ways they could be transmitted, this post reproduces one of these stories, first printed in 1864. It would have been widely read and retold throughout the Irish-American community in the United States, including among Irish soldiers in Union camps as they prepared for the dreadful summer campaigns of that year.

The tradition of the story-teller or seanchaí that was so strong in the 19th century has almost died out today. Ireland’s most famous remaining seanchaí is Eddie Lenihan, who here tells a story of the fairy folk, taking the form of a black dog.

The story was first published in Dublin’s Irish People on 2nd January 1864, and was authored by “Merulan”, a pen-name for Robert Dwyer Joyce, a Limerick-born poet and collector of Irish music and stories. The New York Irish-American picked up on it and published it for its readers on 13th February 1864. After the Civil War Joyce would emigrate to the United States, where he would formally publish the story in 1871 as part of his collection Irish Fireside Tales. The narrative revolves around Mun Carberry and his wife Nancy, a happy-go-lucky pair with a love of Irish music and dance, and their encounter with both the púca and the fairies, which reached a climax on New Year’s Eve. In the context of the story that follows, the púca were creatures trained by the fairies to do their bidding, taking the form of a goat or horse. New Year’s Eve was a time in Irish folklore when fairies could be found roaming through the landscape. The story demonstrates the extremely strong associations that many in the Irish countryside saw between the visible remains of Ireland’s Early Medieval landscape and the fairy folk. Ireland boasts one of the best preserved Early Medieval landscapes in Europe, principally demonstrated through the remains of earthen farmsteads known as ringforts or raths. Over time these became associated with the fairies, and were often called fairy forts. Until late in the 20th century, it was a widespread belief that it was extremely bad luck to interfere with these sites. It is fascinating to consider how this story may have been disseminated through Irish emigrants in the ranks of forces such as the Army of the Potomac, perhaps being recounted for illiterate comrades around the campfire, and conjuring up images of home. It is below reproduced in full.

MUN CARBERRY AND THE PHOOKA;

OR,

THE RETURN ON NEW YEAR’S EVE

BY MERULAN

There was not a man through all the wild fields of Munster, from the grey slopes of Sliav Bloom to Brandon Hill, that had such a light heart as Mun Carberry. Neither would you see from Youghal Harbor to Garryowen a fairer face than that of his young wife Nancy, nor hear a merrier voice than hers as she ordered out her two strapping servant maids to the milking bawn on a fine May morning. It is often said by wise people, that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and that a blackbird in the pot is better than a wild goose on the wing, and also that a clean conscience, a clean shirt, and guinea are no despicable possessions; and all these saws were illustrated by Mun Carberry and his wide, for they took what Providence sent them without murmuring, and joyfully made use of the little they possessed without wishing and repining for things beyond their reach; and as they each had an honest heart, and enough to live upon through either hard or prosperous times, you would not, on the whole, find a happier couple in a nice day’s ramble.

But all people have their failings. Mun had two. The first, which certainly was no failing, except in the eyes of the old and spiteful, was a love of music and dancing, which was shared in equally by his wife– said music being particularly the lilt of the Irish pipes, and the dancing, and the powdering away at an eight-hand reel, a slip jig or a moneen. There was a not a night of their lives, from Christmas Day to St. John’s and over again to Christmas Eve, that some wandering musician did not sit in their chimney corner; and ’tis there, upon the dry earthen floor you would hear the footing about, the shuffling and the jolly pattering of heel and toe, as Mun and Nancy, the servants and the neighbors rattled away to the tune of “The Cricket’s Rambles through the Hob,” “Allisdrum’s March,” “The Hare in the Corn,” or “The Pretty Girls of Coolroe,” or some other tune, that it would delight your heart to listen to. At fair, patron and meeting they were also to be seen footing it way on the “light fantastic toe;” and it was said all over the country, from Corrin Mor to Corrin Thierna, that there was not a piper in the barony that would not rather play for them for nothing that skirl a tune for any other pair of dancers for the brightest h’penny bit in Munster.

Mun’s other failing was a firm belief in the supernatural– in the existence and appearance of ghosts, fetches, cluricaunes, sheevras and phookas. To the latter– a phantom that generally appears to people in the shape of a mighty horse, a huge bearded he-goat, a kid, a great black bull, or a calf– he was particularly partial ,and often on going home at night from a fair, from the market in the neighboring town, or maybe from a wake, he would peer fearfully around him, expecting to catch a glimpse of the phooka in some dark hollow or glen, but for a long-time his half shuddering curiosity remained unsatisfied. Notwithstanding this, at the mowing time, the greenest and tenderest grass upon the upland remained behind by Mun’s especial orders for the regalement of the phooka, and for the same purpose, when the spalpeens dug out the potatoes, towards All Hallowtide, some of the best and brownest cups and the soundest and whitest jumpers were left behind upon the ridge. For a like intention, also, you would see every evening scattered over the farm-yard and the paddock wisps of sweet-smelling hay and handfuls of the cleanest and whitest straw, so that nothing was neglected on the part of Mun to render a meeting between himself and the phooka an amicable one in case of such an event occurring at any time of his life.

It is a nice thing to be contented, and a good thing as the song says, to be merry and wise; and, as I have said before, you would not find within the five corners of old Ireland a happier more jovial heart than Mun Carberry’s; but the old people will tell you that have proved it and known it well, that let a man’s path be ever so smooth and flowery in the beginning, it may before the end become rough and thorny, that the longest lane has a turning, that there never was a summer that a winter did not follow, and that the stream which glides and winds through the green flowery meadows like a thread of glittering silver or a bead of pearls may be dashed into smithereens over the rocks before it falls into the ocean. And what happened to Mun carried out the old peoples’ sayings to a T.

One fine summer morning while Mun and the neighbors who had come to help him were out saving hay in the meadow, his wife, with the milk set, the house swept clean and all her work done, was sitting upon her siesteen at the door crooning the “Colleen Bawn” to herself with a happy heart, and looking out over the long, straight boreen that, with its two rows of oershadowing beech and green, feathery ash trees, led up to the farm-yard from the broad, sunny plan beneath. After coming to the end of her song, she turned to Noreen Gal, the servant maid, and told her to prepare the potatoes for dinner. A moment before not a living thin could be observed upon the boreen; but now, as Nancy turned and was about to resume her song once more, she beheld a great funeral moving slowly along its whole extent upwards from the plain, with cars and horsemen and footmen, and a great gilded hearse in the front, from the top of which waved four snowy plumes of feathers in the light wind that blew across the sloping uplands.

Unable to speak a word, and with a heart throbbing fearfully, Nancy continued to gaze upon the mournful and unwonted spectacle till at last the hearse rumbled into the yard and stopped in its midst opposite the door. Four tall, dark-looking horsemen then dismounted behind, took a coffin from the hearse and were bearing it towards where Nancy sat in fixed and unutterable terror, when a little red cock that was perched upon the barn top flew down between her and them, clapped its wings and began crowing loud enough to break its gallant little heart. At its voice the men turned round slowly, and without a word laid the coffin in the hearse; and, as the brave little bird advanced, clapping its wings and crowing louder than ever ,the four great black horses that drew the spectral funeral car were turned round by the drivers, and at length the might concourse that accompanied it turned also, moved back again down the boreen, and finally faded from poor Nancy’s sight out upon the plain below.

Rathwaun-Hare in the Corn

That night, although the dancing went on as usual the piper played in vain for Nancy Carberry in the chimney corner. In vain Mun and the neighbors asked her the cause of her melancholy. Terror kept her silent, and not a word would she say concerning the spectral funeral. Next morning the same thing occurred:– the little cock flew down from the barn top, clapped its wings and crowed, and the fearful spectacle faded away from Nancy’s eyes as before. Still she did not tell her husband. On the third morning the funeral cam up again, the four men dismounted and brought forth the coffin, but now no saving bird of mercy flew down from the barn top. As the men came forward Nancy’s terror at length found voice.

“Noreen! Noreen Gal!” she screamed, “where is the little red cock that ought to be on the top of the barn? Noreen! Noreen! where is he? Quick! quick! or your misthress is dun for ever if be isn’t to the fore!”

“Wisha, faith a vanithee,” answered Noreen, who stood unsuspectingly filling a pot with potatoes by the fire, “the little imp o’ the divvle was making such a noise about the yard these days past that I thought it unlucky an’ kilt him for the masther’s supper!”

“Lord bethune us an’ harm!” exclaimed Nancy in her terror, “you have killed your misthress, too, Noreen.Oh! wirra wirra! what’ll become of me? Save me! save me, Noreen! Look! look!”

Noreen looked, and at the sight she beheld, darted into an inner room screaming with fright, and hid herself beneath a bed.

“Is there no one to save me? Oh! Mun! Mun! where are you?” shrieked Nancy, as she sat chained to the spot in the agony of terror.

No Mun appeared; but at the call a huge gray goat, with its long snowy beard sweeping the ground, danced with many a caper round the corner of the ouse, and in between her and the four men, where, raising himself upon his hind feet, he began to butt and present his sharp horns at the intruders, and with such effect that the latter turned as before, and laid the coffin back in the hearse. And now, with wilder antics than ever, the goat danced round the yard, charging and butting at horse and man, till at length the great funeral turned, moved slowly and mournfully down the boreen, and faded as before out upon the sunny plain. The moment they had disappeared, the goat turned round, trotted up to the door, and fixed its great black eyes upon Nancy Carberry. Fascinated by the look, Nancy arose, and followed the weird-looking animal round the corner of the house and into the garden. Dinner time came on and Mun came in with his hay-makers, but no vanithee [Bean an tí – lady of the house] sat at the table head to make their hearts merry with her bright smile. That night there was loud lamentation in poor Mun Carberry’s house, for the young vanithee did not return, and for many days after they searched through wood and glen, village and town, and over the wide and dreary moorlands that stretched up the slopes of the hills, but never a sight of Nancy did they see high or low. The wise ones, the old people– those who ought to know, shook their heads, and said that she was surely alive and well, in Corrin Thierus, maybe, or in the old Fort of Lisdorney with the fairies.

Still, Mun Carberry kept up his heart, and although he mourned in secret, the neighbors and those whom he met on the Fair Green, had always the light word and the pleasant smile, for he said to himself that a pound of sorrow never paid an ounce of debt, that a man in a pond must swim or else he’ll drown, and that if he ever was to win back his young vanithee, it was not by moping at home in grief and melancholy.

Now a’nights when returning home he looked around more eagerly than ever in order to catch a glimpse of the phooka, for he said–

“One who I have thrated so well ought to be my friend, an’ p’raps may give me news o’ the vanithee. Howsomever, if he’s not, there’s an ind to it. Sorrow kilt a Dane, an’ good humor is the sowl of long life. God help me this blessed night!”

His good humor and trust in the phooka’s friendship were soon, however, to be put to the test. One night as hr was coming home from the wake of Saer-gorm, or the Blue-mason– ’tis a quare name, but I can’t stop to tell stories– he crossed the river at Aha-na-slae, and took the short cut homeward through the fields. After ascending the side of the glen from the green inches beneath, he came to a formidable barrier in the shape of a huge double fence with its two well filled ditches. Mun Carberry’s light legs, however, were not to be stopped by any such impediment. He leaped over the first ditch, climbed up the side through the hazels and thick brier, stepped across to the other side, gave a flying leap to rach the green meadow beyond, and landed upon the back of the phooka, this time in the shape of a great black horse with streaming mane, and long sable tail that switched the heads off the flowers which bloomed upon the meadow behind him.

“Be the sowl o’ my body, but I’m in for it at last!” exclaimed Mun, as he stepped forward, clutched the phooka’s long black mane and squeezed his knees like the bold rider that he was, and thus holding on prepared himself for the worst. “Howsomever, the darkest an’ grumach face may have the kindest ondher it, an’ tisn’t the smiling friend that’ll always help one in his need so here goes for the sake of the vanithee and the blue skies over Grenx!”

With that the phooka darted off with a hilarious neigh, now doubling and rearing, now floundering and splashing with headlong speed through the quagmires and morasses of the low grounds, now rushing quick as lightning across the craggy ridges on the uplands, and then plunging through the winding river below. At length, after sweltering through the river about the sixth time, he suddenly stopped upon the inch reared upon his fore legs, and with a neigh like the blast of a trumpet, pitched Mun Carberry into the air, and landed him unhurt and safe upon the smooth top of Corrig-a-Phipera, or the Piper’s Rock, a solitary crag that rises over the north-eastern bank of the stream.

Well might it be called the Piper’s Rock, for as Mun landed upon it from the back of the phooka, there sat upon a boulder at one side of its flat summit a diminutive little atomy of a man, clad in red body-coat, waistcoat and breeches, with a pair of small top-boots that seemed one the have belonged to a horse-ride, a somewhat weather-beaten caubeen set jauntily over his right eye, and a chanter resting upon his knee– said chanter belonging to an elegant set of bran new pips, which was that moment in the act of tuning. After an infinite variety of flourishes, stops and wild skirls of music, he at length finished the tuning of his instrument, and then looked at Mun.

Téada Irish Christmas/Allisdrum’s March

“Be the hole o’ my voat, Mun,” said he, “but you’re just come in the nick o’ time, an’ you’re as welcome as the flowers o’ May! What’ll you have?– a thribble, a slip, or a moneen? ‘The Thursh’s Nest,’ ‘the Bay an’ the Grey,’ ‘Jackson’s Bottle o’Punch,’ or ‘Nora Ciestha?’ Allow me to insinivate that the latther is by far the most hilarious an’ lively in comparisment with the others, an’ that your fut will keep time to it as merrifluously as the jinglin’ of a sixpence on a tombstone!”

“Whatever is most plasin’ to yourself, sir,” answered Mun, politely. “Let it be ‘Norak Cleatha’ for sake o’ the ould times whin I an’ the vanithee often danced it forenint aich other.”

“Be this chanter in my hand, but yet may often dance it again together, if it lies in the power of Drinaun Brac to do ye a good turn!” said the little piper. “But here goes for good luck, as the gamecock said to the sparrow whin he picked out his eye,” and with that he rattled up “Norah Ciestha” in a wild and joyous tone that would make the dead shake their toes under their green sods in Religa Ronan.

“Hurroo!” shouted Mun, as he powdered away at the moneen with a gusto and a nice and careful attention to time that made the eyes of Drinaun Brac twinkle with satisfaction. “Be all the stones in Corrin Thierna, but that’s nate intirely!” and he footed it about, sprang up into the air, came down lightly upon his toes, drummed with his heels, and then executed step after step too numerous and various to describe.

“That’s it! straighten the chest, back with the elbows, and cover the buckle!” cries the little atomy encouragingly, and in high delight, as Mun now shuffled away like mad–”that’s it! Honom an dhial! but in all the forths in Munsther there isn’t the likes of him for a janius at the gut!”

At length Mun gave an athletic spring upward, came down with a resounding clash of his brogues upon the bare smooth rock, executed another stampede round and round, and then bringing the right foot behind the left, and taking off his caubeen, bowed to the little piper, thus ending the moneen with the height of politeness and urbanity.

“Well,” said the Drinaun Brac, as he stood up and bowed gracefully in return, “I have often wished to see you at a moneen, Mun Carberry. Allow me to express by onquinchable an’uprorious delight an’ shupernathral plisure at your performance of it. Go home for this night in pace an’ quietness, an’ tomorrow set out upon your thravels to look for the vanithee. The time p’rhaps, isn’t yet ome; but when next we meet, I may be able to do somethin’ for you, for I’m your friend, an’ have intherest with one who has power to do you good– manin’ bethune ourselves, my masther, Farreen Shrad, who thrains the phookas for the King o’ the Fairies. Good night; and may the most amberosial and unspeakable good forthin attind on your peregrinashins!”

With that he bowed once more, and, in the twinkling of an eye, vanished from the astonished gaze of Mun Carberry. Mun then descended the rock, crossed the stream, and went home with a lighter heart than he had known for many a long and weary day previously. Next morning he arose, told the servants that he was going from home for some time, warned them to take care of the cattle and the farm, and to be sure to have a piper in the chimney corner for a hearth warming at his returning, and then set off upon his wanderings n search of his lost wife.

One morning, about a month afterwards, as he was sitting on the top of the old castle of Kilcoleman, and gazing out sad and sorrowful upon the lake, he saw a small but intensely bright rainbow resting before him upon the water. Underneath this a figure, at first vague and shadowy, rose into view, but becoming at each successive movement more substantial and distinct, it at length assumed a form, the sight of which made his heart beat with a wild feeling of gladness. It was the very face and figure of his lovely wife Nancy, but now seeming far more fair and beautiful than ever. She seemed to be wrapped in a light robe of blue all glistening over like the coat of one of those gray-birds that flit like living sunbeams through the primeval woods of the torrid eastern climes. She stood lightly on the glassy surface gazing around, at first upon the green shores, but at last turning to poor Mun, who stretched out his loving arms towards her, she advanced a few steps, stood, and then pointed three times up to the pass of Aha-na-Suilish, or the Ford of Light, a gorge in the mountains behind the castle. After resting near him for a short time the apparition began to recede; and, when it reached the middle of the lake, the rainbow rising slowly into the air mingled with the light morning vapours, and the lovely figure of his wife disappeared again beneath the crystal, waveless water.

“be the blessed stone of Ard-na-naov, but ’tis herself at last!” exclaimed Mun. “An’ now I know by the way she pointed that she is in the ould Rath o’ Lisdorney; for, sure enough, there it lies above in the middle of the Pass of Aha-na-Suilish. If watchin’ an’ waitin’ there will do, night, morning, an’ noon, it’ll go hard with me if I don’t bring her back some time or another, anyhow!”

[image error]

Irish Púca (Celtic Mythpod)

He then came down from his perch upon the old castle, and morning, noon and night, for a long time after, watched for the appearance of his wife beside the fairy rath of Lisdorney in the pass. One fine December evening as the sun was setting in a blaze of red beyond the summit of Corrin-Mor, Mun sat in a thicket at the skirt of the wood, from which, although concealed himself, he could observe every object beside the Rath. As he was ruminating gloomily upon the sad fate that separated himself and his wife, he was suddenly startled from his reverie by a wild-skirl of a chanter outside, and sure enough, on looking out, he beheld his acquaintance of the rock sitting upon a stone beside the pathway. This time, however, Drinaun Brac was not alone. A figure sat beside him whom Mun at once recognised from his habiliments as the trainer of the phookas to the Fairy King– namely Farreen Shrad, the master of Drinaun, the piper. A blazing red hunting coat fell down upon his slender, bowed legs, which latter were encased in a pair of top boots, the fac simile of those worn by the little piper, differing only in the spurs that ornamented them. A scarlet riding cap decorated his head, and beneath its peak, his eyes, like two sparkling carbuncles, lit up a jovial round face, from the midst of which projected a splendid bacchanalian nose, with an extremity red as a ripe cherry in autumn. After a few attempts, Drinaun Brac seemed to give up the tuning of his instrument in despair, and then the two fairy men began conversing on various topics.

“Well,” said Farreen Shrad, which means the Little Man of the Bridle, “purshuin’ to me if I can stand the work at all at all, as I used to do in ould times. Five hundhert years ago, when the blood was hot in my veins, I could do a’most anything, but now I’m a feard I must give the trainin’ business up into younger hands!”

“Thrue for you, masther,” returned the piper, “whin ould age comes on everything looks quare and gloomy. To my mind there is mo plisure whin a person comes to that, but in making cquaintance with the sowl-soothering potheen bottle! ‘Tis the only cornucopy of plisure that warms my heart anyhow.”

“Sthrike us up a thune!” resumed Farreen Shard, abruptly, “sure enough, the pipes an’potheen are my only comfort now, whin I’m gettin’ ould an’ stiff!”

“Wish, where’s the use in playin’ afther all,” said Drinaun, “whin I haven’t a dancer to keep time? If I had only Mun Carberry here now!”

“Never say it twice!” exclaimed Mun, starting up from his hiding place. “Here I am so rattle up Norah Ciestha again, an’ be the lase o’ my hat I’ll do it justice, in compliment of the civil way you spake of me.”

Drinaun Brac tuned his pipes and struck up Norah Ciestha, and Mun rattled away as before to the great delight of Farreen Shrad, who gave vent to his pleasure in a series of yells and hunting shouts that made the Pass ring.

“An’ now,” said Farreen, as Mun bowed to him at the end of the jig, “as civility and perliteness is the ordher of the day, an’ as merriment an’ the most obsthreperous joviality must reign shruprame bethune us, I’ll sing you a song which I learned from ould Garodh Dorney, the poet, whom we had in the Rath with us for nearly a month o’ Sundays. Sate yourself foreninth me there on the bank. Here foes. He made it in praise of some place in the West which he called:

THE GARDEN O’ DAISIES

When first I saw my darlin’ in the Garden o’ Daisies,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

I thought she was Diana or the beautiful Vainus,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

I thravelled France an’ Spain, an’ likewise in Assiah !

An’ spint many a long day at my aise in Araabia;

But ever knew a place like the Lakes o’ Killarney.

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

‘Tish there the mountains rise up with great imulation,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

With the finest of ould timber an’ foxes in the nation,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

There the deers and bullocks broowse, and the pikes in the wather

They mutilate the salmon an’ throuts with great slaughter.

An’ the cockatoo an’ pheasant they crow in the mornin’,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

Were I numerate an’ confess all the praises,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

Of my darlin’ that dwells in this Garden o’ Daisies,

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

I’d want the pen o’ Vargil, an’ powers o’ great Homer,

A,’ the tongue that kissed ould Blarney, an’ riches o’ Damer.

An’ the eyes o’ Rhadymantus, an’ Bluebeard’s pine-thrashion

Fal urlium, ri durlium, muilearthach fa ral i !

[image error]

An Early Medieval Ringfort (“Fairy Fort”) in West Co. Limerick, across the road from the house in which I grew up (Damian Shiels)

Tallyho! there ’tis for you in the toss of a tinpinny bit! Lisdorney for ever and the blue skies above it– Tallyho-o-o!

“An’ now, Mun Carberry,” said Farreen Shrad, as he came ot the end of his hunting shout, ‘bethune ourselves, you have some inimies where you know. ‘Tis they that wanted to take your wife away the day they came up the boreen, an’ ’tis I out of an’ ould regard for you sent my favorite phooka, Gonreen Glas, to the house to save her; an’ he brought her here away from them, where she’s safe and sound. But as our queen has taken a fancy to her it won’t be so aisy to get her back. Never mind, howsomdever, I’ll manage it. Next New Year’s Eve, just at nightfall, be here at the Foord, where I’ll lave the best thrained phooka horse from here to the Rocks o’ Skellig behind for you in the wood. Mount him without fear or consthernation, and whin you see your wife crossing the Foord in the thrain of the queen, rattle into the midst of them, pull up your wife afore you, and then gallop away for your life. I’m now an ould ‘an a particklar friend to the king, an’ will stand the blame; and turn it all into ludicracy!”

Mun stood up to make his bow and thank Farreen Shrad, but when he looked again both the fairyment were gone.

At length came New Year’s Eve with its white mantle of sparkling feathery snow on hill and moorland, valley and lonely wildwood. Mun Carberry with a stout heart went up to the pass of Aha-na-Suilish, and into the wood where he found the identical phooka horse that had before pitched him to the top of the Piper’s Rock, awaiting him. The moment he had mounted the great steed, he looked out and there beheld the Rath of Lisdorney in one blaze of splendor glittering before him, with a long glimmering and shining train of knights and ladies issuing from a blazing portal in its front, in the midst of which he saw his wife riding on a little palfrey behind the Fairy Queen. He waited till they were in the act of crossing the ford, then rattled forward, and amid the shrieks of the Queen and her maids of honor, seized his wife, drew her before him on his steed, and dashed away like lightning down the pass out on the open moorland, and off towards his house, before the door of which they were safely deposited by the phooka, which now with a thunderous and joyful neigh darted back again to the moors the rejoin his companions.

That night the merriest dance that ever was seen was danced upon the kitchen floor in the light of their blazing turf fire by the light-hearted Mun Carberry and his wife, who were never afterwards troubled by either the Good People, the Phooka, or the Fairies.

References

The Irish People 2nd January 1864. Mun Carberry and the Phooka; Or, The Return On New Year’s Eve.

New York Irish-American Weekly 13th February 1864. Mun Carberry and the Phooka; Or, The Return On New Year’s Eve.

Joyce, Robert Dwyer 1871. Irish Fireside Tales.

Filed under: Irish Folklore Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Fairies, Irish Folk Tales, Irish Puca, Mun Carberry, Robert Dwyer Joyce, Seanchaidhthe

December 9, 2016

Communicating Death & Creating Memory on Fredericksburg’s Streets

I have recently had a conference paper accepted on the topic of letters communicating bereavement to those on the Home Front. Since I began my work on the widow’s and dependent pension files, I have become particularly interested in these types of document, and in exploring the multitude of questions we can ask of them. How was news of death transmitted? What degree of detail was provided (or not)? What was the language of consolation (if any) employed by the writer? I have also been thinking about how this information was physically imparted to the bereaved and experienced by them– for example, for illiterate families the correspondence would have to be read aloud by a third-party. What responses did they compose (if any?), and what questions did they ask? To demonstrate just how much of this type of correspondence survives in the files, and also something of its variety and range, this post takes a look at bereavement letters written to the Irish emigrant families of four soldiers– all of whom died as a result of the savage fighting endured by the 20th Massachusetts Infantry on the streets of Fredericksburg on 11th December 1862.

Depiction of Fredericksburg from the 1906 Regimental History of the 20th Massachusetts (The Twentieth Regiment)

On the evening of 11th December 1862 the 20th Massachusetts Infantry– the “Harvard Regiment”– was one of the units engaged in driving the Confederates from the city of Fredericksburg, clearing the way for the main assault of the Rebel positions that followed two days later. What they experienced that day would become one the famed episodes of the war. As Union troops sought to expand their bridgehead in the city, the 20th Massachusetts was sent forward to face an enemy who were ensconced in both buildings and at street intersections. The main body of the 20th advanced from the direction of the river up Hawke Street towards Caroline Street. Commanded by Captain Henry Macy, the regiment’s advance was led by Henry L. Abbott, who brought his company forward to march on the intersection. As the Massachusetts men pushed on, a Michigander Major warned them that “no man could live beyond that corner.” The Confederates were waiting. Once the 20th marched into the cross street the darkness was “lighted up by the flash of muskets” as a sheet of fire poured into the regiment. Although his command was almost wiped out, Abbott ran the gauntlet and crossed the intersection. As he sought to continue west, another battalion of the 20th faced south onto Caroline Street, while a third turned north. The fading light made it difficult for the Union men to see their targets. In the words of Captain Macy “we could see no one and were simply murdered.” While the other two battalions held the intersection, Abbott continued up Hawke Street; all three groups sustained terrible losses. The city was eventually taken by the Federals, but for the 20th Massachusetts it had come at a staggering cost. They had suffered 97 casualties in the space of just fifty yards. Many Irish-Americans were among the fallen. (1)

Depiction of the Fredericksburg streets where the 20th Massachusetts were engaged, depicted in the 1906 Regiment History. For discussion on the precise streets the 20th fought on, see O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign (20th Massachusetts)

Among the 20th Massachusetts Irishmen in the streets of Fredericksburg that day was James Briody (sometimes Briady). He was part of an emigrant family from Castlerahan, Co. Meath, who left Ireland for North Andover, Massachusetts. An express driver before his enlistment, he joined up on 11th August 1862. The 24 years-old was described as 5 feet 7 inches tall, with blue eyes, light hair and a fair complexion. On the night of 9th December, two days before the fight for the streets of Fredericksburg, he wrote to his widowed mother, seemingly with little idea of what was to come:

Falmouth Va.

Dec 9th 1862

Dear Mother,

I am well at this time and hope you are the same. I got your letter yesterday and was happy to hear you was well and my sister. I do not know of any news at this time we go on picket tomorrow and that is a job we do not like as we have now log huts to live in which we have built. I like to have you send me a pair of gloves by mail, as we have no chance to get them here, and we do not have any money now, nor do I know when we will get any. I hope soon as we cannot get anything without the money and it must be a good pile too, for the article we buy. I am out of money and I want to get a pair of boots and in order for to get them I want you to send $5 so I can get them. It is now very cold and wet here, and muddy. There is now some 3 or 4 inches of snow on the ground and it is poor shoes that the government gives us. As regards the box, you will not send it untill I write you again, as I do not know how long we shall stay here, and I shall have time to send it before I need it. When you do send it, send me a pretty good share of paper and envelopes, as it is hard to get them here, as there is not any chance to buy them here. Give my love to all of my sisters and send those things as soon as you get this, and be sure to write as often as you can as I am always happy to hear from you, and tell all of my sisters to write as often as they can. I am glad that all things are going on so well at home. I do not know of any more at this time, but I will write you more next time, if I have a plenty of time. I will now wish you good night, as soon as I get paid off I shall send you the most of my wages as I shall not want it all myself, but do you get the state aid, let me know, as I am in hopes you will let me know in your next without fail. No more from your son,

James Braidy

Direct as follows

Mr James Braidy

Co “I” 20 Reg Mass Vols

Washington D.C. (2)

A soldier of the 20th Massachusetts at Camp Benton, Maryland (Library of Congress)

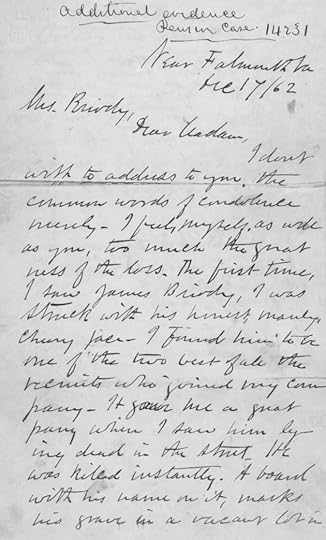

As is often the case with last letters, foreknowledge of what was to occur brings poignancy to the mundane. The events of 11th December meant there would be no opportunity for James to get new gloves or boots, there would be no “next time” to write. Beyond what this letter can tell us about the events of 1862, it also represents an object of memory in its own right. The context of its survival allows us to infer the emotional value that James’s mother Maggie invested in this last letter. We know this because the document in file is not an original, but a copy. Instead of submitting the actual correspondence– as so many others did– she instead had it transcribed in front of a Justice of the Peace, in order that she could keep hold of a cherished memento of her son. This fact allows us to consider how a very ordinary letter could be invested with additional meaning and emotional value because of subsequent events. How many times in the years ahead did she look at the original, her last communication from her son? Another who felt James’s loss was his Captain, Henry Livermore Abbott. On 17th December 1862 he penned the following to the Co. Meath emigrant:

Near Falmouth VA

Dec 17/62

Mrs. Briody,

Dear Madam,

I don’t wish to address to you the common words of condolence merely- I feel, myself, as well as you, too much the greatness of the loss. The first time, I saw James Briody, I was struck with his honest, manly, cheery face. I found him to be one of the two best of all the recruits who joined my company. It gave me a great pang when I saw him lying dead in the street. He was killed instantly. A board with his name on it, marks his grave in a vacant lot in Fredericksburg. Believe me that I sympathize most deeply with you, in your awful loss.

I remain,

Respectfully

H.L. Abbott

Capt Co I 20 Mass

The pay due him can be got by applying through a lawyer to the dept at Washington. (3)

The first page of Captain Henry Livermore Abbott’s letter to Maggie Briody (NARA/Fold3)

These letters informing loved ones of a soldier’s death had the potential to be powerful agents of memory. The words an officer chose in the hours and days after a death could form a lasting picture in a family’s mind of their fallen kin’s last moments, and whether or not they had met a good death. In that context, the words chosen had the capacity to resonate across decades. Abbott took up his pen again the following day, this time to the sister of another Irish emigrant, John Deasy. Unlike James Briody, John had grown to adulthood in Ireland, marrying his wife Joanna in Clonakilty, Co. Cork in February 1845. The couple subsequently emigrated to Boston during the Famine, where they began to raise a family. They had four surviving children by the time Joanna died of consumption in July 1860. The network of fellow Cork emigrants and family that surrounded John helped him to care for his children when he enlisted on 18th July 1861. By the time of the Battle of Fredericksburg his eldest Mary was 14, Daniel was 12, Catherine was 9 and Margaret was 6. John had already survived a wound in the arm during the Seven Days’ battles, but on 11th December his luck had run out. Captain Abbott demonstrated that he was well aware of the Corkman’s personal circumstances when he wrote to Boston:

Near Falmouth

Dec 18/62

Your brother John Duecy [Deasy] was mortally wounded in the battle of the 11th. He lived, I believe, till the next day, & was buried from the hospital. He was as honest and brave a fellow as ever lived. I trust his orphan children will be properly cared for. You can get his pay by applying through a lawyer to the dept at Washington.

Very truly yours

H.L. Abbott

Capt Co I 20 Mass. (4)

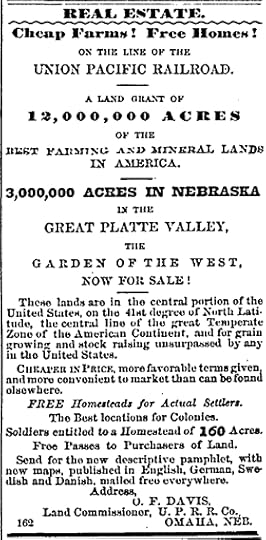

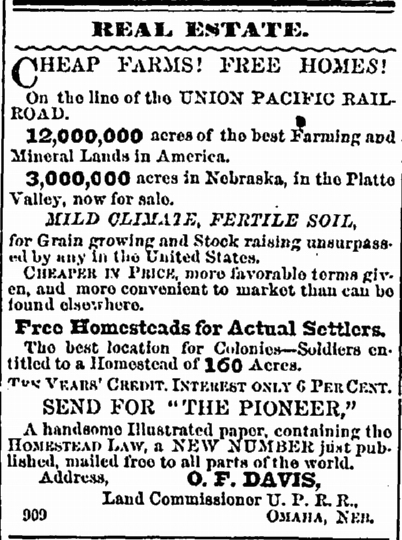

Is this the advertisement that brought the Donnelly family (below) to America? It was one a series that ran in Ireland in 1847, this example from the Cork Examiner of 4th August 1847. Those from Tipperary who wished to travel to the United States first made their way to Cork, where they boarded the Governor Davis before a rendezvous with the Ocean Monarch at Liverpool (Cork Examiner)