Damian Shiels's Blog, page 55

February 17, 2013

The 146 Irish Recipients of the Medal of Honor from the American Civil War

As part of the Irish-born Medal of Honor Project I have overhauled the Medal of Honor page to provide further information on the 146 Irish-born recipients from the Civil War I have thus far identified. A new introduction provides some background to the Irish awards, while more detailed entries for each of the men are also included. This represents the most comprehensive listing of Irish-born recipients from the Civil War currently available; the revised introduction and listing is also available as part of this post.

The Medal of Honor was instituted on December 21, 1861, to recognise gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life and above and beyond the call of duty. It started its history as a Naval award, and was initially restricted to enlisted personnel in the United States Navy and Marines. An Army Medal of Honor followed on July 12, 1862, and was likewise restricted to enlisted personnel. The latter award was expanded to include army officers on March 3, 1863, although naval officers would remain ineligible until 1915. (1)

The first physical medals were issued to six survivors of ‘Andrew’s Raid’, an all volunteer mission which was targeted at disrupting rail communications in Confederate held Georgia. These were presented in Washington on March 25, 1863, with the first naval presentations taking place a few days later on April 3, 1863. A total number of 1,200 medals were awarded to army personnel for actions in the American Civil War, with a further 327 going to the navy and marines.(2) Many recipients did not receive recognition until decades after the conclusion of the conflict; the final recipients were two members of the 47th Ohio Infantry who received their awards in 1917.(3)

At least 146 Irish-born men received the Medal of Honor for services during the American Civil War, almost ten percent of the total number awarded. Of these, a number have only recently come to light as Irish-born, having initially been erroneously categorised as of unknown or American nativity. It is probable that this figure will increase as further research is conducted into the backgrounds of Medal of Honor recipients. Of the Irish awards, no fewer than fifty were awarded to Irishmen in the naval and marine service, just over fifteen percent of the total number for that category.

Studies of Irish participation in the American Civil War often focus on well-known ‘green flag’ units such as the Irish Brigade and Corcoran’s Irish Legion. However, the vast majority of Irish-born men served in non-Irish regiments or in the naval arm of the service. Perhaps understandably, their stories are often much harder to discover and explore. Analysis of the Irish-born Medal of Honor recipients brings some of these men to the fore. Indeed of the total number, fewer than twenty were members of ethnic Irish regiments.

Three of the Irishmen would eventually receive the award twice; Coxswain John Cooper of the U.S.S. Brooklyn for two separate actions in Mobile Bay, Alabama; Boatswain’s Mate Patrick Mullen for gallantry in action and lifesaving, both in 1865; Fireman John Laverty (Lafferty) for actions on the Roanoke River during the war with the second for bravery in peacetime, aboard the U.S.S. Alaska in 1881. Although instituted during the American Civil War, the earliest chronological award was to Irishman Assistant Surgeon Bernard J.D. Irwin for service at Apache Pass, Arizona in February 1861.(4) The chronologically earliest Irish award of the conflict was to Corporal Owen McGough for actions at the First Battle of Bull Run. The first Irish-born men to physically receive the Medal of Honor were all sailors, who were presented with the award on 3 April 1863.

A list of these 146 Irishmen appears below, together with their unit and the engagement at which they performed their act of heroism. This listing forms part of the Irish-born Medal of Honor Project. If you are aware of any potential additions or corrections to the list below, or have information that you feel will further the project please contact me at irishamericancivilwar@gmail.com.

Ahern, Michael. Paymaster’s Steward, USS Kearsarge. (5)

Co. Cork.

Action off Cherbourg, France, 19 June 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Allen, James. Private, Company F, 16th New York Infantry.

Action at South Mountain, Maryland, 14 September 1862. Medal issued 11 September 1890.

Anderson, Robert. Quartermaster, USS Crusader, USS Keokuk.

Action at Charleston, South Carolina, 7 April 1863. Medal issued 10 July 1863.

Barry, Augustus. Sergeant-Major, Company C, 16th U.S. Infantry.

Various actions. Medal issued 28 February 1870.

Bass, David L. Seaman, U.S.S. Minnesota.

Action at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, 15 January 1865. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Begley, Terrence. Sergeant, Company D, 7th New York Heavy Artillery.

Action at Cold Harbor, Virginia, 3 June 1864. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Blackwood, William R.D. Surgeon, 48th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Co. Down.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 21 July 1897.

Bradley, Charles. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Louisville. (6)

Various actions. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Brannigan, Felix. Private, Company A, 74th New York Infantry.

Action at Chancellorsville, Virginia, 2 May 1863. Medal issued 29 June 1866.

Brennan, Christopher. Seaman, U.S.S. Mississippi.

Action at Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, 24-25 April 1862. Medal issued 10 July 1863.

Brosnan, John. Sergeant, Company E, 164th New York Infantry.

Co. Kerry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 17 June 1864. Medal issued 18 January 1894.

Brown Jr., Edward. Corporal, Company G, 62nd New York Infantry.

Action at Fredericksburg and Salem Heights, Virginia, 3-4 May 1863. Medal issued 24 November 1880.

Burk, Michael E. Private, Company D, 125th New York Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania, Virginia, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Burke, Thomas. Private, Company A, 5th New York Cavalry.

Action at Hanover Courthouse, Virginia, 30 June 1863. Medal issued 11 February 1878.

Byrnes, James. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Louisville. (7)

Various actions. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Campbell, William. Private, Company I, 30th Ohio Infantry.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 14 August 1894.

Carey, Hugh. Sergeant, Company E, 82nd New York Infantry.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2 July 1863. Medal issued 6 February 1888.

Casey, David. Private, Company C, 25th Massachusetts Infantry.

Action at Cold Harbor, Virginia, 3 June 1864. Medal issued 14 September 1888.

Cassidy, Michael. Landsman, U.S.S. Lackawanna.

Action Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Colbert, Patrick. Coxswain, U.S.S. Commodore Hull.

Action at Plymouth, North Carolina, 31 October 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Collis, Charles H.T. Colonel, 115th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Co. Cork.

Action at Fredericksburg, Virginia, 13 December 1862. Medal issued 10 March 1893.

Conboy, Martin. Sergeant, Company B, 37th New York Infantry.

Action at Williamsburg, Virginia, 5 May 1862. Medal issued 11 October 1892.

Connor, Thomas. Seaman, U.S.S. Minnesota.

Action at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, 15 January 1865. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Connors, James. Private, Company E, 43rd New York Infantry.

Action at Fishers Hill, Virginia, 22 September 1864. Medal issued 6 October 1864.

Cooper, John. Coxswain, U.S.S. Brooklyn.

Co. Dublin.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Cooper, John. Coxswain, U.S.S. Brooklyn. (8)

Co. Dublin.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 26 April 1865. Medal issued 29 June 1865.

Corcoran, Thomas E. Landsman, U.S.S. Cincinnati.

Co. Dublin.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 27 May 1863. Medal issued 10 July 1863.

Cosgrove, Thomas. Private, Company F, 40th Massachusetts Infantry.

Co. Galway.

Action at Drurys Bluff, Virginia, 15 May 1864. Medal issued 7 November 1896.

Creed, John. Private, Company D, 23rd Illinois Infantry.

Co. Tipperary.

Action at Fishers Hill, Virginia, 22 September 1864. Medal issued 6 October 1864.

Cullen, Thomas. Corporal, Company I, 82nd New York Infantry.

Action at Bristoe Station, Virginia, 14 October 1863. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Curran, Richard. Assistant Surgeon, 33rd New York Infantry.

Co. Clare.

Action at Antietam, Maryland, 17 September 1862. Medal issued 30 March 1898.

Delaney, John C. Sergeant, Company I, 107th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Dabnys Mills, Virginia, 6 February 1864. Medal issued 29 August 1894.

Donoghue, Timothy. Private, Company B, 69th New York Infantry.

Action at Fredericksburg, Virginia, 13 December 1862. Medal issued 17 January 1894.

Doody, Patrick. Corporal, Company E, 164th New York Infantry.

Action at Cold Harbor, Virginia, 7 June 1864. Medal issued 13 December 1893.

Doolen, William. Coal Heaver, U.S.S. Richmond.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Dougherty, Michael. Private, Company B, 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Co. Donegal.

Action at Jefferson, Virginia, 12 October 1863. Medal issued 23 January 1897.

Dougherty, Patrick. Landsman, U.S.S. Lackawanna.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Downey, William. Private, Company B, 4th Massachusetts Cavalry.

Action at Ashepoo River, South Carolina, 24 May 1864. Medal issued 21 January 1897.

Drury, James. Sergeant, Company C, 4th Vermont Infantry.

Action at Weldon Railroad, Virginia, 23 June 1864. Medal issued 18 January 1893.

Dunphy, Richard D. Coal Heaver, U.S.S. Hartford.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

English, Edmund. First Sergeant, Company C, 2nd New Jersey Infantry.

Action at Wilderness, Virginia, 6 May 1864. Medal issued 13 February 1891.

Fallon, Thomas T. Private, Company K, 27th New York Infantry.

Co. Galway.

Action at Williamsburg, Virginia, 5 May 1862 and Fair Oaks, Virginia, 30-31 May 1862 and Big Shanty, Georgia 14-15 June 1864. Medal issued 13 February 1891.

Flood, Thomas. Boy, U.S.S. Pensacola. (9)

Action at Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, 24-25 April 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Flynn, Christopher. Corporal, Company K, 14th Connecticut Infantry.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 3 July 1863. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Ford, George W. First Lieutenant, Company E, 88th New York Infantry.

Action at Sailors Creek, Virginia, 6 April 1865. Medal issued 10 May 1865.

Fox, Nicholas. Private, Company H, 28th Connecticut Infantry.

Action at Port Hudson, Louisiana, 14 June 1863. Medal issued 1 April 1898.

Gardner, William. Seaman, U.S.S. Galena.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Gasson, Richard. Sergeant, Company K, 47th New York Infantry.

Action at Chapins Farm, Virginia, 29 September 1864. Medal issued 6 April 1865.

Ginley, Patrick. Private, Company G, 1st New York Light Artillery.

Action at Reams Station, Virginia, 25 August 1864. Medal issued 31 October 1890.

Gribben, James H. Lieutenant, Company C, 2nd New York Cavalry.

Action at Sailors Creek, Virginia, 6 April 1865. Medal issued 3 May 1865.

Haley, James. Captain of the Forecastle, U.S.S. Kearsarge.

Co. Cork

Action off Cherbourg, France, 19 June 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Harrington, Daniel. Landsman, U.S.S. Pocahontas. (10)

Action at Brunswick, Georgia, 11 March 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Havron, John H. Sergeant, Company G, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 16 June 1866.

Highland, Patrick. Corporal, Company D, 23rd Illinois Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 12 May 1865.

Hinnegan, William. Second Class Fireman, U.S.S. Agawam.

Action at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, 23 December 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Horan, Thomas. Sergeant, Company E, 72nd New York Infantry.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2 July 1863. Medal issued 5 April 1898.

Horne, Samuel B. Captain, Company H, 11th Connecticut Infantry.

Action at Fort Harrison, Virginia, 29 September 1864. Medal issued 19 November 1897.

Howard, Martin. Landsman, U.S.S. Tacony.

Action at Plymouth, North Carolina, 31 October 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Hudson, Michael. Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps.

Action with the U.S.S. Brooklyn at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Hyland, John. Seaman, U.S.S. Signal.

Action at Red River, Louisiana, 5 May 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Irwin, Patrick. First Sergeant, Company H, 14th Michigan Infantry.

Co. Clare.

Action at Jonesboro, Georgia, 1 September 1864. Medal issued 28 April 1896.

Jones, Andrew. Chief Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Chickasaw.

Co. Limerick.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Jones, William. First Sergeant, Company A, 73rd New York Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania, Virginia, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Kane, John. Corporal, Company K, 100th New York Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 12 May 1865.

Keele, Joseph. Sergeant-Major, 182nd New York Infantry.

Action at North Anna River, Virginia, 23 May 1864. Medal issued 25 October 1867.

Kelley, John. Second Class Fireman, U.S.S. Ceres. (11)

Action at Hamilton, North Carolina 9 July 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Kelly, Thomas. Private, Company A, 6th New York Cavalry.

Action at Front Royal, Virginia, 16 August 1864. Medal issued 26 August 1864.

Kennedy, John. Private, Company M, 2nd U.S. Artillery.

Action at Trevilian Station, Virginia, 11 June 1864. Medal issued 19 August 1892.

Keough, John. Corporal, Company E, 67th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Sailors Creek, Virginia, 6 April 1865. Medal issued 3 May 1865.

Kerr, Thomas R. Captain, Company C, 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Action at Moorefield, West Virginia, 7 August 1864. Medal issued 13 June 1894.

Laverty, John. Fireman, U.S.S. Wyalusing. (12)

Co. Tyrone.

Action at Roanoke River, North Carolina, 25 May 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Laffey, Bartlett. Seaman, U.S.S. Marmora.

Co. Galway.

Action off Yazoo City, Mississippi, 5 March 1864. Medal issued 16 April 1864.

Logan, Hugh. Captain of the Afterguard, U.S.S. Rhode Island.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 30 December 1862. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Lonergan, John. Captain, Company A< 13th Vermont Infantry.

Co. Tipperary.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2 July 1863. Medal issued 28 October 1893.

Madden, Michael. Private, Company K, 42nd New York Infantry.

Action at Masons Island, Maryland, 3 September 1861.

Medal issued 22 March 1898.

Mangam, Richard C. Private, Company H, 148th New York Infantry.

Action at Hatchers Run, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 21 September 1888.

Martin, Edward S. Quartermaster, U.S.S. Galena.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Martin, James. Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps.

Co. Derry/Londonderry.

Action with the U.S.S. Richmond at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Martin, William. Seaman, U.S.S. Varuna. (13)

Action at Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, 24 April 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

McAdams, Peter. Corporal, Company A, 98th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Salem Heights, Virginia, 3 May 1863. Medal issued 1 April 1898.

McAnally, Charles. Lieutenant, Company D, 69th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania, Virginia, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 1 August 1897.

McCarren, Bernard. Private, Company C, 1st Delaware Infantry.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania 3 July 1863. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

McCormick, Michael. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Signal.

Action on the Red River, Louisiana, 5 May 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

McEnroe, Patrick H. Sergeant, Company D, 6th New York Cavalry.

Action at Winchester, Virginia, 19 September 1864. Medal issued 27 September 1864.

McGough, Owen. Corporal, Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery.

Co. Monaghan

Action at Bull Run, Virginia, 21 July 1861. Medal issued 28 August 1897.

McGowan, John. Quartermaster U.S.S. Varuna. (14)

Action at Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Louisiana, 24 April 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

McGraw, Thomas. Sergeant, Company B, 23rd Illinois Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 12 May 1865.

McGuire, Patrick. Private, Chicago Mercantile Battery, Illinois Light Artillery.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 15 January 1895.

McHale, Alexander U. Corporal, Company H, 26th Michigan Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania Court House, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 11 January 1900.

McHugh, Martin. Seaman, U.S.S. Cincinnati.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 27 May 1863. Medal issued 10 July 1863.

McKee, George. Color Sergeant, Company D, 89th New York Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia 2 April 1865. Medal issued 12 May 1865.

McKeever, Michael. Private, Company K, 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Action at Burnt Ordinary, Virginia, 19 January 1863. Medal issued 2 August 1897.

Molloy, Hugh. Ordinary Seaman, U.S.S. Fort Hindman.

Action at Harrisonburg, Louisiana, 2 March 1864. Medal issued 16 April 1864.

Monaghan, Patrick. Corporal, Company F, 48th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 17 June 1864. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Montgomery, Robert. Captain of the Afterguard, U.S.S. Agawam.

Action at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, 23 December 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Moore, Charles. Landsman, U.S. Steam Gunboat Marblehead.

Action off Legareville, Stono River, South Carolina, 25 December 1863. Medal issued 16 April 1864.

Morrison, John G. Coxswain, U.S.S. Carondelet.

Action on the Yazoo River, Mississippi, 15 July 1862. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Morton, Charles W. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Benton. (15)

Action at Drumgould’s Bluff, Yazoo River, Mississippi, 27 December 1862. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Mulholland, St. Clair A. Major, 116th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Co. Antrim.

Action at Chancellorsville, Virginia, 4-5 May 1863. Medal issued 26 March 1895.

Mullen, Patrick. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Wyandank.

Action on Mattox Creek, Virginia, 17 March 1865. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Mullen, Patrick. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Don. (16)

Action near Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1 May 1865. Medal issued 29 June 1865.

Murphy, Denis J.F. Sergeant, Company F, 14th Wisconsin Infantry.

Co. Cork.

Action at Corinth, Mississippi, 3 October 1862. Medal issued 22 January 1892.

Murphy, John P. Private, Company K, 5th Ohio Infantry.

Co. Kerry.

Action at Antietam, Maryland, 17 September 1862. Medal issued 11 September 1866.

Murphy, Michael C. Lieutenant-Colonel, 170th New York Infantry.

Co. Limerick.

Action at North Anna River, Virginia, 24 May 1864. Medal issued 15 January 1897.

Murphy, Patrick. Boatswain’s Mate, U.S.S. Metacomet.

Co. Waterford.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Murphy, Thomas C. Corporal, Company I, 31st Illinois Infantry.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 14 August 1893.

Murphy, Thomas J. First Sergeant, Company G, 146th New York Infantry.

Action at Five Forks, Virginia, 1 April 1865. Medal issued 10 May 1865.

Nolan, John J. Sergeant, Company K, 8th New Hampshire Infantry.

Action at Georgia Landing, Louisiana, 27 October 1862. Medal issued 3 August 1897.

Nugent, Christopher. Orderly Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps.

Co. Cavan.

Action with the U.S.S. Fort Henry, Crystal River, Florida, 15 June 1863. Medal issued 16 April 1864.

O’Beirne, James R. Captain, Company C, 37th New York Infantry.

Co. Roscommon.

Action at Fair Oaks, Virginia, 31 May-1 June 1862. Medal issued 20 January 1891.

O’Brien, Peter. Private, Company A, 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry.

Action at Waynesboro, Virginia, 2 March 1865. Medal issued 26 March 1865.

O’Connell, Thomas. Coal Heaver, U.S.S. Hartford.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

O’Connor, Timothy. Private, Company E, 1st U.S. Cavalry.

Action at Malvern, Virginia, 28 July 1864. Medal issued 5 January 1865.

O’Dea, John. Private, Company D, 8th Missouri Infantry.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 12 July, 1894.

O’Donnell, Menonmen. First Lieutenant, Company A, 11th Missouri Infantry.

Actions at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863 and Fort DeRussey, Louisiana, 14 March 1864. Medal issued 14 March 1864.

Platt, George C. Private, Troop H, 6th U.S. Cavalry.

Action at Fairfield, Pennsylvania, 3 July 1863. Medal issued 12 July 1895.

Plunkett, Thomas. Sergeant, Company E, 21st Massachusetts Infantry.

Co. Mayo.

Action at Fredericksburg, Virginia, 11 December 1862. Medal issued 30 March 1866.

Preston, John. Landsman, U.S.S. Onieda.

Action at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Quinlan, James. Major, 88th New York Infantry.

Co. Tipperary.

Action at Savage Station, Virginia, 29 June 1862. Medal issued 18 February 1891.

Rafferty, Peter. Private, Company B, 69th New York Infantry.

Action at Malvern Hill, Virginia, 1 July 1862. Medal issued 2 August 1897.

Rannahan, John. Corporal, U.S. Marine Corps.

Action with the U.S.S. Minnesota at Fort Fisher, North Carolina, 15 July 1865. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Reynolds, George. Private, Company M, 9th New York Cavalry.

Action at Winchester, Virginia, 19 September 1864. Medal issued 27 September 1864.

Riley, Thomas. Private, Company D, 1st Louisiana Cavalry.

Action at Fort Blakely, Alabama, 4 April 1865. Medal issued 8 June 1865.

Roantree, James S. Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps.

Co. Dublin.

Action with the U.S.S. Oneida at Mobile Bay, Alabama, 5 August 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Robinson, John H. Private, Company I, 19th Massachusetts Infantry.

Action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 3 July 1863. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Robinson, Thomas. Private, Company H, 81st Pennsylvania Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania, Virginia, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 1 December 1864.

Ryan, Peter J. Private, Company D, 11th Indiana Infantry.

Action at Winchester, Virginia, 19 September 1864. Medal issued 4 April 1865.

Scanlan, Patrick. Private, Company A, 4th Massachusetts Cavalry.

Action on the Ashepoo River, South Carolina, 24 May 1864. Medal issued 21 January 1897.

Schutt, George. Coxswain, U.S.S. Hendrick Hudson.

Action at St. Marks, Florida, 5-6 March 1865. Medal issued 22 June 1865.

Sewell, William J. Colonel, 5th New Jersey Infantry.

Co. Mayo.

Action at Chancellorsville, Virginia, 3 May 1863. Medal issued 25 March 1896.

Shields, Bernard. Private, Company E, 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.

Action at Appomattox, Virginia, 8 April 1865. Medal issued 3 May 1865.

Smith, William. Quartermaster, U.S.S. Kearsarge.

Action at Cherbourg, France 19 June 1864. Medal issued 31 December 1864.

Spillane, Timothy. Private, Company C, 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Co. Kerry.

Action at Hatchers Run, Virginia, 5-7 February 1865. Medal issued 16 September 1880.

Stewart, Joseph. Private, Company G, 1st Maryland Infantry.

Action at Five Forks, Virginia, 1 April 1865. Medal issued 27 April 1865.

Sullivan, Timothy. Coxswain, U.S.S. Louisville. (17)

Various actions throughout the war. Medal issued 3 April 1863.

Tobin, John M. First Lieutenant and Adjutant, 9th Massachusetts Infantry.

Co. Waterford.

Action at Malvern Hill, Virginia, 1 July 1862. Medal issued 11 March 1896.

Toomer, William. Sergeant, Company G. 127th Illinois Infantry.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 9 July 1894.

Tyrell, George William. Corporal, Company H, 5th Ohio Infantry.

Action at Resaca, Georgia, 14 May 1864. Medal issued 7 April 1865.

Urell, M. Emmet. Private, Company E, 82nd New York Infantry.

Co. Tipperary.

Action at Bristoe Station, Virginia, 14 October 1863. Medal issued 6 June 1870.

Walsh, John. Corporal, Company D, 5th New York Cavalry.

Co. Tipperary.

Action at Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864. Medal issued 26 October 1864.

Welch, Richard. Corporal, Company E, 27th Massachusetts Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 2 April 1865. Medal issued 10 May 1865.

Wells, Thomas M. Chief Bugler, 6th New York Cavalry.

Action at Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864. Medal issued 26 October 1864.

Welsh, Edward. Private, Company D, 54th Ohio Infantry.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 11 May 1894.

Welsh, James. Private, Company E, 4th Rhode Island Infantry.

Action at Petersburg, Virginia, 30 July 1864. Medal issued 3 June 1905.

White, Patrick H. Captain, Chicago Mercantile Battery, Illinois Light Artillery.

Action at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 22 May 1863. Medal issued 15 January 1895.

Williams, William. Landsman, U.S.S. Lehigh.

Action at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1 November 1863. Medal issued 16 April 1864.

Wilson, Christopher W. Private, Company E, 73rd New York Infantry.

Action at Spotsylvania, Virginia, 12 May 1864. Medal issued 30 December 1898.

Wright, Robert. Private, Company G, 14th U.S. Infantry.

Action at Chapel House Farm, Virginia, 1 October 1864. Medal issued 25 November 1869.

(1) RJ Proft (ed.), United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations,Fourth Edition, (Minnesota, 2002), pp. 1-5; Robert P. Broadwater, Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients: A Complete Illustrated Record, (North Carolina, 2007), pp. 4-6.

(2) Over 900 further awards were revoked by a review panel in 1917 as they were deemed not to meet the criteria for the medal

(3) Broadwater, Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients, p.6. The Ohioans received the award for actions at Vicksburg in 1863.

(4) As Irwin’s award does not directly relate to the American Civil War he is not included in this list.

(5) Irish nativity usually not cited. Illegally recruited in Queenstown and erroneously named as ‘Michael Aheam’.

(6) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor.

(7) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(8) Two time recipient of the Medal of Honor

(9) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(10) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(11) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(12) Laverty (also referred to as Lafferty) was awarded a second Medal of Honor for bravery on the U.S.S. Alaska on 14 September 1881. This medal was issued on 18 October 1884.

(13) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(14) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(15) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

(16) Two time recipient of the Medal of Honor

(17) In the first group of naval recipients of the Medal of Honor

*With thanks to John Fay and Brendan Hamilton for additions to this list

Further Reading

Broadwater, Robert P. 2007. Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients: A Complete Illustrated Record

Proft, R.J. (ed.), 2002. United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations, Fourth Edition

Congressional Medal of Honor Society

Filed under: Medal of Honor, Research Tagged: American Civil War, Gallantry, Irish American Civil War, John Cooper, Medal of Honor, Mobile Bay, New York Infantry, United States Navy

February 7, 2013

Irish American Civil War Veterans- in Australia

The vast majority of Irish-born veterans of the American Civil War lived out the remainder of their lives in the United States. As we have previously explored on the site (see here and here) a small number of these men also returned home to Ireland. Incredibly, there were others who chose to travel even further afield. Some men chose to end their post-war days on the other side of the world, settling in Australia.

Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, Western Australia (Angela Gallagher)

The Australia of today is home to a vibrant community of those interested in the American Civil War. They even have their own Round Tables (see here and here). Barry Crompton, a founding member of the American Civil War Round Table of Australia, has also written a fascinating work entitled ‘Ireland, Australia and the American Civil War’ which I highly recommend. In the book Crompton details the history of a number of Irish veterans (and possible veterans) and charts their fate in Australia. As I have relations in Perth, Western Australia, I took the opportunity to ‘persuade’ one of my family to go on an expedition to photograph some of these men’s graves.* (1)

The grave of John Joseph Davies, Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, Western Australia (Angela Gallagher)

A number of the men are buried in Karrakatta Cemetery, located seven kilometres west of Perth city centre. One of the possible veterans is John Joseph Davies, from Co. Galway. He was said to have served the Confederacy while his brother Netterville fought for the Union, although it has not as yet been possible to confirm that this was the case. Another of the men in Karrakatta is Michael Joseph Malone (or Maloney) from Co. Clare who reportedly served as a Private in Company F, 20th Connecticut Infantry. An Australian newspaper noted in 1926 that the well-traveled Irishman was then due to celebrate his 100th birthday. The stark contrast between the two men’s grave markers suggests that they may have enjoyed differing fortunes in their new home. (2)

The simple marker of Michael Joseph Malone, Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, Western Australia (Angela Gallagher)

William Kenyon of SCV Camp 2160 has also researched American Civil War veterans in Australia, and includes another man interred in Karrakatta among his lists. His name is Edward Stanley from Belfast, who is said to have served in the US Navy during the war under the assumed name of Frank Lawrence. Among his ships were the USS Santiago de Cuba, USS Monongahela, USS Nipsic, USS Franklin, USS James Adger and USS Princeton. A merchant navy man after the war, Edward was discharged in Melbourne, Victoria in 1876. He married and had two children, living until 1908 when he died at Cottesloe Beach, Claremont in Western Australia. (3)

The grave of Edward Stanley, Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, Western Australia (Karrakatta Cemetery)

These Irishmen are but a small number of those who made the journey from Ireland to the United States and ultimately journeyed onwards to Australia. Their choice to try their luck in a third country is a fascinating one; many were surely driven by a sense of adventure, opportunity and perhaps the quest for gold. The rich research into Australia’s connections with the American Civil War have revealed this little-known Irish connection, yet another intriguing facet to the Irish experience of the American Civil War.

General view of Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, Western Australia (Angela Gallagher)

*I am grateful to Angela Gallagher of the Silver Voice Blog for braving the heat of Karrakatta to take photographs for this post.

(1) Crompton 2008; (2) Crompton 2008: 23, 30; (3) William Kenyon Australian and New Zealand American Civil War Veterans;

References & Further Reading

Crompton, Barry J. 2008. Ireland, Australia and the American Civil War

The American Civil War Round Table of Australia, Inc.

American Civil War Roundtable of Australia NSW Chapter

Filed under: Australia Tagged: American Civil War Roundtable, Australia American Civil War, Australian Gold Rush, Irish American Civil War, Karrakatta Cemetery, Perth, USS Nipsic, Western Australia

February 3, 2013

An Outline of ‘The Irish in the American Civil War’ Book

I am delighted to announce that my first book, ‘The Irish in the American Civil War’ published by The History Press Ireland, is now available. IF you are interested, the best place to purchase the book is from The History Press Ireland website page, here. They will ship anywhere free of charge. In addition the book should be available in bookshops across Ireland from the middle of this month. For any readers in the United States who are interested in getting a copy, although it is not yet available through US sites, you can also purchase it direct from the History Press Ireland in dollars with free shipping.

The Irish in the American Civil War (History Press Ireland)

To give readers a flavour of what the book is like, first and foremost I should point out that it is not intended as an all-encompassing history of the Irish in the American Civil War. Rather it follows the style of this blog, presenting personal stories that help to cast light on some of the influences on the Irish American community before, during and after the conflict. Some of the stories are significantly expanded versions of ones that have appeared on the site, while others are completely new to the book. It is split into four sections, ‘Beginnings’, ‘Realities’, ‘The Wider War’ and ‘Aftermath’, each intended to explore a different aspect of the Irish experience. The chapter breakdown and content is outlined below; I hope that for any of you who consider buying the book that it will prove an enjoyable read!

Introduction

Looks at the scale of Irish participation in the American Civil War, its links to the Famine generation, and why it is not better remembered in Ireland.

BEGINNINGS

The duel that almost changed history

The story of James Shields and the duel he challenged Abraham Lincoln to in 1842.

Witness to the first shots

Thee story of Commander Stephen Rowan and his ship the USS Pawnee at Fort Sumter in 1861.

The Irish at Sumter

Explores the Irish involvement in the army before the war and in events such as John Browns Raid, before looking at the Irish who were in the Sumter garrison in 1861.

Facing the first battle

The story of three Irishmen and their different experiences of First Bull Run, and the subsequent effect it had on them and their families.

Recruiting for the Irish Brigade

Why would the Irish fight for the Union? Examining the motivations of Irishmen in New York through a speech given by Thomas Francis Meagher at the Academy of Music in 1861.

Following them home

Who made up green-flag regiments? This chapter looks at that question, using the 23rd Illinois Infantry as a case study.

REALITIES

A Yankee and Rebel at Antietam

Two Irishmen led their regiments towards the Cornfield at Antietam. Both Irish, one was a Yankee and one a Rebel- neither would survive the experience.

Slaughter in Saunders’ Field

The American Civil War presented an opportunity for industrial killing on a frightening scale, where large numbers of men could be wiped out in moments. This was what the Irish 9th Massachusetts experienced at Saunders’ Field, The Wilderness in May 1864.

Blood on the Banner

The story of Thomas Plunkett of the 21st Massachusetts, grievously wounded at Fredericksburg, but who went on to become an important symbol of the Massachusetts war effort.

Death of a General

Patrick Cleburne remains largely unknown in Ireland. This tells the story of his final moments, when he lost his life at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee in November 1864.

The last to fall

No less a person than George Meade held Thomas Alfred Smyth as one of his finest Generals. This briefly tells his story, and how he became the last Union General to die in the American Civil War.

An Irishman in Andersonville

The story of Michael Dougherty, later a Medal of Honor recipient, who kept a diary in Andersonville and also survived the Sultana disaster.

THE WIDER WAR

Killed by his Own

Looks at the reasons behind the New York Draft Riots, Irish involvement, and the death of one Irishman, Colonel Henry O’Brien, in horrendous circumstances.

Confederates in Ireland

The Confederate government sent a number of agents to operate in Ireland to prevent recruitment into the Union army. This looks at their efforts, techniques and the men involved.

The Queenstown Affair

When the USS Kearsarge anchored in Queenstown (now Cobh), Co. Cork in 1863, she sparked a diplomatic incident through allegations of illegal recruitment. For one Irishman the visit would change the course of his life.

The Civil War with Canvas and Camera

Not all Irishmen at the front were combatants. This tells the story of photographer Timothy O’Sullivan and Special Artist Arthur Lumley who used their talents to bring the war to the Home Front.

Jennie Hodgers and Albert Cashier

The remarkable story of Jennie Hodgers, who served as Albert Cashier in the 95th Illinois and kept up her male identity until well into the twentieth century.

The Irish ‘Florence Nightingales’

Looks at some of the Irish laywomen who went to the front to help with the war effort, such as Bridget Diver of Custer’s Wolverines, and Mary Sophia Hill of the Louisiana brigade.

AFTERMATH

Mingle my Tears

The cost of the war for many families at home was huge. This looks at how a number of families sought to cope with the loss of their loved ones at the front and the effect it had on their lives.

The price of gallantry

The consequences of the war could last for decades. This looks at wounded veterans, both physically and mentally, and the pain that the war could still cause long after the guns fell silent.

Hunting Lincoln’s Killer

Roscommon man Jame Rowan O’Beirne was in the room when Lincoln died, and was charged with hunting down John Wilkes Booth, a job he carried out diligently. This is his story.

The passage of years

How did old veterans remember the war as the years passed? How did the Irish community seek to remember these honoured veterans? This looks at these efforts as the numbers of veterans dwindled into the twentieth century.

Back to the stone wall

24 years after their heroic defence of the stone wall at Gettysburg, the 69th Pennsylvania returned to erect a memorial to their fallen comrades, and to meet some of their former foes. This is the story of that occasion.

Epilogue

Looks at JFK’s presentation of an Irish Brigade flag in 1963, and the future of remembrance of the American Civil War in Ireland.

Filed under: Book Tagged: Abraham Lincoln, Bridget Diver, Civil War Books, Damian Shiels, History Press Ireland, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Irish in the American Civil War

February 1, 2013

The Irish Brigade Cigarette Case in the Attic

A little over a year ago friend Jim Swan, author of the excellent Chicago’s Irish Legion sent me on an image of a cigarette case he had come across. It commemorated a 50th anniversary dinner held in 1912 for the survivors of the Irish Brigade who served at Fredericksburg. I decided to research the object, which revealed a remarkable story which was the topic of a subsequent post (read it here). In fact I was so taken with it that I also decided to cover this commemorative dinner in my book (which is now available, but more of that anon!). The inscribed cigarette cases were available to those who attended the 1912 anniversary event, so imagine my delight when recently contacted by reader Patricia Doherty, who is also in possession of one of these cases.

The cigarette case in pristine condition, replete with original Turkish cigarettes (Patricia Doherty)

Patricia recently discovered the superbly preserved object in an attic, complete with the original packet of Turkish cigarettes inside! The object may well have belonged to Patricia’s Great-Great-Grandfather who was a Civil War veteran. Patricia is seeking the help of readers in determining the value of the object, so any assistance in that regard would be appreciated. It is a truly magnificent object, which was discovered just in time for the 150th anniversary of the event that it commemorates.

Detail of the inscription on the case, which was produced for the 50th anniversary dinner for Irish Brigade survivors of Fredericksburg (Patricia Doherty)

Obverse of the Turkish cigarette packet (Patricia Doherty)

Reverse of the Turkish cigarette packet (Patricia Doherty)

Filed under: Battle of Fredericksburg, Irish Brigade Tagged: 69th Armory, 69th New York, Cigarette Case, Civil War Memory, Civil War Reunion, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Reunion, Turkish Cigarettes

January 30, 2013

Visualising the Demographics of Death: 82 men of the 9th Massachusetts

The American Civil War killed hundreds of thousands of men, and devastated millions of lives. The industrialised battlefields of 1861-65 racked up casualty lists so huge that they become practically impossible to visualise- Fredericksburg 17,929; Shiloh 23,746; Gettysburg 51,000. The physical scale of such losses makes the overall ripple effect each death had on dependents and loved ones almost impossible for us to comprehend. Perhaps one way around this is to start looking at the losses in smaller and more mentally comprehensible numbers. One approach is to study a single battle- in this case the 1862 engagement at Gaines’ Mill, Virginia- and the dead from a single regiment, in order to try and visualise what was lost with all this death. The regiment I have chosen is the 9th Massachusetts Infantry.

To read an account of the 9th Massachusetts’s fighting at Gaines’ Mill, Virginia on 27th June 1862 see a previous post here. It suffices here to note that the battle was Robert E. Lee’s first in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, and ended in Southern victory. The Irish 9th Massachusetts were engaged for the entire day, a fact reflected by their losses, which were the worst in the Army of the Potomac. They sustained a total of 249 casualties, 82 of whom were killed or mortally wounded. A number like 82 dead, though still horrific, presents us with an opportunity to view in microcosm what thousands of deaths across whole battles and campaigns really represented. However, it is still a challenge for us to see behind and beyond the number, to see what it represents. To do that we have to try and find out who these men were, where they lived, what their jobs had been- what hole did their death leave in the fabric of life for those they left behind?

With these questions in mind I studied the 9th Massachusetts dead of Gaines’ Mill in the hope of partially answering some of these questions. Working with the regimental roster provided in veteran Daniel MacNamara’s 1899 History of the Ninth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, some interesting information was revealed. I have attempted to highlight some of that information in visual format here.

I started first with where these 82 men were born. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the ethnic nature of the regiment, the majority were from Ireland. At least 61 had been Irish emigrants born in Ireland, with a further 7 born in the United States, 4 in Canada and a further 10 unknowns. Despite the fact that we might expect many of these men to be of Irish birth, to note over 60 Irishmen dying in a single regiment in a single engagement (albeit in a notably arduous battle) brings home the true magnitude of the American Civil War for many Irish people. Clearly the hard fighting of the 9th Massachusetts Infantry, especially as it was a ‘green flag’ regiment, meant that the 27th June 1862 was a bad day for the Irish of that state.

Birthplaces of the Gaines’ Mill Dead

Although the men who died that day were largely Irish, they had made a new home in the United States, and the vast majority of them lived in Massachusetts when they enlisted in 1861. We might expect nearly all of them to have made that home in Boston- and indeed many did- but there was also a large number of others who had settled elsewhere in the state. The map below shows the state of Massachusetts- the blue pins represent the different locations where 76 of the 9th Massachusetts dead resided in 1861.

View Larger Map

What of these men’s jobs? We often expect the majority of the Irish poor to be listed as laborers, but at least in the sample from Gaines’ Mill dead this is not the case. Fifteen of those that fell dead in the face of the Confederate attack had just a year before been bootmakers; a further thirteen shoemakers. The dominance of the leather trade is a reflection of the vibrancy of that profession in their home state at the time. In addition, some of the men had what might be termed ‘unusual’ jobs, examples being George Grier, the Confectioner, and Peter McIntyre, the Oyster Opener.

Professions of the Gaines’ Mill Dead

What then of the age of the 82? The vast majority of those of the 9th Massachusetts killed at Gaines’ Mill had barely begun their lives. Of the 80 for whom age information is available, only eight were over 30 years old when they enlisted in 1861. At 37 Morroco-Dresser Joseph Smyth represented the eldest in 1861 by two clear years. A total of 49 of the men had been 23 years old or younger when they enlisted, the year before they lost their lives.

Ages of the Gaines’ Mill Dead on Enlistment

Given the low age of the majority of the dead it is perhaps unsurprising that only 14 of the 82 men killed were married. This reduced the number of offspring who were impacted by the losses, although at least fifteen children were left without a father as a consequence of the 9th Massachusetts death toll at Gaines’ Mill. Of these children, four were under two years old at the time their father was killed; none were over the age of fourteen.

Age of Children at Father’s Death in 1862

There is evidence for at least twenty pensions being claimed by dependents as a result of the 9th Massachusetts dead from 27th June. These are split evenly between ten widows of deceased men and ten mothers, who had relied on their sons for financial support. A more detailed look at this information will undoubtedly reveal more about the consequences of some of these deaths; for example Hannah Marrin and Ellen Day both remarried before the end of the war- the need for financial stability may well have played a role in their decisions. Ellen McQuade, the wife of Tyrone born papermaker John McQuade, went insane in the time after her husband’s death, again potentially a consequence of her loved one’s death, and one of the many ‘ripple effects’ of the war.

This is some of the information we can glean from an examination of the dead of Gaines’ Mill. There is much more that can be learned- for example, how many direct family members experienced personal loss as a result of the 9th’s fatalities on the 27th June 1862? One would expect given the age profile of the soldiers that many younger siblings were left to mourn their loss along with their parents. I have only begun to explore information such as this as it pertains to the 9th Massachusetts Infantry, and in the course of time I intend to look at the entire regiment, seeking to discover more about those who marched in its ranks. It is only by looking at these men’s social background, their ante-bellum lives and the effect of the war on their families that we can truly begin to understand the impact of the American Civil War.

Further Reading

MacNamara, Daniel George (edited by Christian G. Samito) 2000. The History of the Ninth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Second Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the Potomac, June 1861- June 1864 (1st Edition 1899)

Civil War Trust Battle of Gaines Mill Page

Filed under: 9th Massachusetts, Battle of Gaines' Mill Tagged: Army of Northern Virginia, Battle of Gaines's Mill, Demographics of Death, Irish American Civil War, Irish Ninth, John McQuade, Ninth Massachusetts, Robert E. Lee

January 25, 2013

Stamp Your Mark on Irish Commemoration of the American Civil War

As many readers will be aware, I do not believe that the Irish State is currently doing enough to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War, particularly given the huge impact it had on the Irish community in the United States. I rarely launch ‘appeals’ through the site, but colleague and accomplished historian Ian Kenneally has alerted me to a programme currently being run by An Post, the Irish Postal Service. They are now in the process of seeking suggestions for topics/subjects that might be covered in their 2015 series of postage stamps. As that will be the final year of the 150th, it would be appropriate that the Irish involvement in the American Civil War is one of the topics covered. To my knowledge the closest An Post have previously come to commemorating the war was a 1995 issue of military stamps covering the Irish Wild Geese which included a 69th New York soldier.

It would be an appropriate gesture if Ireland now produced a full set of stamps to commemorate the Irish experience of the conflict. An Post have an online form where you can put forward a suggestion for themes, with a brief outline of the reasons behind your choice. I would hope if enough of us suggest the Irish in the American Civil War as a topic, it might come to fruition. If you are interested in filling out the online form it can be accessed through the An Post Stamp Programme page here. The ‘Stamp Programme 2015′ section is towards the bottom of the page, with a link to the online form. The closing date for submissions is 29th March. Heres hoping for a positive outcome!

Captain Robert Halpin from Co. Wicklow was commemorated in a series of famous mariner stamps by An Post in 2003. Although most famous for laying telegraphic cables, he was also a blockade runner in the American Civil War

Filed under: Appeal Tagged: 69th New York, American Civil War, An Post, Ireland American Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Postage stamp, Stamp, Wild Geese

January 20, 2013

When Oscar Met Walt: Oscar Wilde and Walt Whitman, January 1882

Walt Whitman is one of America’s greatest poets. He was profoundly affected by his time spent visiting and caring for the wounded during the American Civil War, an experience that influenced much of his subsequent writing. In the decades following the conflict, one of Whitman’s biggest fans was a young Irish poet and playwright who was himself destined for greatness- Oscar Wilde. On 16th January 1882 the 27-year-old Wilde met the 62-year-old Whitman at the latter’s home in Camden, New Jersey, while the Irishman was on a lecture tour in North America. (1)

Walt Whitman in 1887 (Library of Congress)

The American Civil War had been the defining moment of Walt Whitman’s life, and led him to create acclaimed poems such as O Captain! My Captain! and When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, both of which deal with the death of Abraham Lincoln. Oscar Wilde certainly viewed Walt Whitman as America’s greatest poet. The Dubliner’s mother had purchased a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1866 and had read passages to Oscar while he was a child. It was therefore unsurprising that Wilde should seek out Whitman when he had the opportunity to visit the United States. The meeting of the two wordsmiths was initially reported in the Philadelphia Press, and later syndicated to many other newspapers, such as the Portland Daily Express. Here Walt Whitman gave his thoughts on the occasion:

‘”Yes, Mr. Wilde came to see me early this afternoon,” said Walt, “and I took him up to my den where we had a jolly good time. I think he was glad to get away from lecturing, and fashionable society, and spend a time with an ‘old rough.’ We had a very happy time together. I think him genuine, honest and manly. I was glad to have him with me, for his youthful health, enthusiasm and buoyancy are refreshing. He was in his best mood, and I imagine that he laid aside any affectation he is said to have, and that I saw behind the scenes. He talked freely about the London literati and gave me many inside glimpses into the life and doings of Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Morris, Tennyson and Browning”…”Wilde and I drank a bottle of wine downstairs,” he continued “and when we came up here, where we could be on ‘thee and thon’ terms, one of the first things I said was that I should call him ‘Oscar,’ ‘I like that so much,’ he answered, laying his hand on my knee. He seemed to me like a great big, splendid boy,” said Whitman, stroking his silvery beard. “He is so frank and outspoken and manly. I don’t see why such mocking things are written of him. He has the English society drawl, but his enunciation is better than I ever heard in a young Englishman or Irishman before. We talked here for two hours. I said to him, ‘Oscar you must be thirsty. I’ll make you some punch.’ ‘Yes, I am thirsty,’ he acknowledged, and I did make him a big glass of milk punch, and he tossed it off, and away he went.” (2)

Oscar Wilde also gave his record of the meeting:

‘There was big chair for him [Whitman] and a little stool for me, a pine table on which was a copy of Shakespeare, a translation of Dante, and a cruse of water. Sunlight filled the room, and over the roofs of the houses opposite were the masts of the ships that lay in the river. But then the poet needs no rose to blossom on his walls for him, because he carries nature always in his heart. This room contains all the simple conditions for art- sunlight, good air, pure water, a sight of ships, and the poet’s works.’ (3)

Oscar Wilde in 1882 (Library of Congress)

Aside from physically describing the meeting, Oscar Wilde gave his impressions of Whitman to the Boston Herald later that month. While on a general discussion regarding poets and their work, he revealed his deep admiration for Whitman:

‘”Do you know,” said Mr. Wilde, “that the greatest fault I have to find with you Americans is that you are not American enough. You are all to cosmopolitan. What I am wishing to meet is a true American. I mean a man of whom it can be said, He is entirely the product of American conditions.” “You will find that in Walt Whitman,” was suggested; “have you met Walt Whitman?” “Indeed I have,” said Mr. Wilde, his face kindling with enthusiasm. “I spent the most charming day I have spent in America with him. He is the grandest man I have ever seen. The simplest, most natural, and strongest character I have ever met in my life. I regard him as one of those wonderful, large, entire men who might have lived in any age, and is not peculiar to any one people. Strong, true and perfectly sane; the closest approach to the Greek we have yet had in modern times. Probably he is dreadfully misunderstood. If people would only know that no artist lives for praise; he only wants one thing, to be understood. I hope that America will not treat its great poets as England too often has. Now, in France, it is different; they are proud that they have poets and artists there, but in England they not only expect them to look to posterity for their fame, but also for their bread and butter.” (4)

The meeting between the two great writers excited public attention and commentary at the time. Wilde and Whitman met again in May 1882, although there is little record of what they discussed on that occasion. They clearly admired each other, and they would remain friends for many years to come. Oscar Wilde would go on to write works such as The Picture of Dorian Gray, Salomé and The Importance of Being Earnest before he was arrested and imprisoned in 1895 on charges of ‘sodomy’ and ‘gross indecency’- a result of his homo-sexuality, which was illegal in England at the time. Oscar was released in 1897 but only lived for a further three years, dying on 30th November 1890. Although Walt Whitman was almost 35 years his senior the American nonetheless outlived him by some 18 months; the man Wilde regarded as America’s greatest poet passed away on 26th March 1892.

(1) Scharnhorst 2008: 116; (2) Portland Daily Express 1882; (3) Scharnhorst 2008: 116; (4) Boston Herald 1882;

References & Further Reading

Portland Daily Express 23rd January 1882. Wilde and Whitman

Boston Herald 29th January 1882. Oscar Wilde

Scharnhorst, Gary 2008. ‘Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde: A Biographical Note’ in Walt Whitman Quarterly Review Volume 25, Number 3, pp. 116-118

Filed under: Dublin, Poetry Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Oscar Wilde, Picture of Dorian Gray, Walt Whitman, Whitman, Whitman American Civil War, Wilde in America

January 19, 2013

The Dead of the Irish Brigade: The Music and Message, 16th January 1863

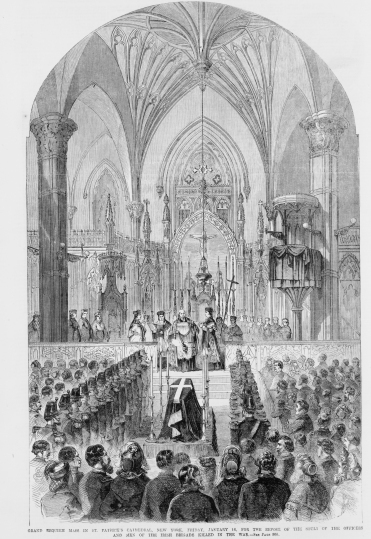

On 13th December 1862 the Irish Brigade had fought at Fredericksburg. Along with many other Union brigades they suffered horrendous casualties in the futile attempt to assault the Confederate positions at Marye’s Heights. The losses sent shockwaves through the Irish-American community. Even as some of the mortally wounded lay dying, it was decided something must be done in New York to remember those who wouldn’t be coming home.

In January 1863 the New York Irish-American informed its readers of the proposed ceremony:

THE DEAD OF THE IRISH BRIGADE

A Grand Requiem Mass, for the repose of the souls of the heroic dead, officers and soldiers, of the Irish Brigade, will be solemnized in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, on Friday, the 16th inst., at 10 o’clock a.m. The Rev. Mr. Ouillette, the devoted and fearless Chaplain of the Brigade, will be the officiating clergyman on the impressive occasion. His Grace the Most Rev. Archbishop Hughes and the clergy of the city, as well as of Brooklyn and New Jersey, will be present [Archbishop Hughes was in the end unable to attend]. General Thomas Francis Meagher, the members of his Staff, and all the officers of the Brigade at present in New York, will attend this most beautiful, tender, and solemn commemoration of their beloved and heroic comrades. A magnificent choir, assisted by the splendid band of the “North Carolina,” will perform Mozart’s immortal Requiem, and in every respect the event will be one that must leave a lasting and profound impression. Major Bagley and all the other officers of the ever-popular old 69th, State Militia, are invited to accompany their friends and brother-officers of the Brigade to the Cathedral on the occasion, and pay this last tribute of Catholic love and Catholic devotion to the never-to-be-forgotten dead of the Irish Brigade. Immediately after the ceremonies at St. Patrick’s, General Meagher, accompanied by all the officers of the Brigade who are able to travel, will return to his command. (1)

The Grand Requiem Mass held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral to honour the dead of the Irish Brigade (Library of Congress)

When the morning of the 16th arrived the front of the Cathedral had been draped in black for the occasion. The altar was similarly decorated and lit with large candles. At the top of the aisle a coffin was placed to represent those men who had fallen at Fredericksburg. It was surrounded by a guard of honor made of marines from the USS North Carolina. The ship’s band were located in one of the galleries beside the organ, in order to provide appropriate accompaniment throughout the ceremony. (2)

A large crowd duly arrived for the mass. Pews had been reserved for the officers of the Irish Brigade, and they entered through the central aisle to take their places. Thomas Francis Meagher was seated in front of the high altar along with his wife and staff. Among the other notables in attendance were Colonel Robert Nugent of the 69th volunteers and Lieutenant Mulhall; the latter attended in Papal army uniform as a Chevalier of the Order of St. Gregory. (3)

The ceremony opened with the organ playing Dies Irae, a latin hymn meaning ‘Day of Wrath.’ This music combined with the sombre scene to create a ‘sensation of awe and devotion to which no heart susceptible of the finer emotions of our nature could be indifferent.’ (4)

Mozart’s Requiem was selected for the High Mass, sung by the choir of the cathedral and accompanied by the band from the North Carolina.

According to correspondents who were present one of the strongest pieces of music played was Rossini’s Cujus Animam from Stabat Mater, described by one reporter as ‘one of the finest pieces of concerted instrumentation we have ever heard.’ (5)

Among the other music used for the ceremony were some selections from Tannhauser’s work and from Verdi’s l masnadieri (The Bandits).

After Father Ouellet had celebrated Mass, Father O’Reilly took to the pulpit requesting that widows of deceased members of the 69th New York make themselves known over the coming days, as a fund had been put together for their relief. The religious element of the sermon then began with the 44th chapter of Ecclesiasticus: ‘laudemus viros gloriosos, et parentes nostros in generatione sua’ (‘Let us praise men of renown, and our fathers in their generation).’ Father O’Reilly moved on to talk directly and extensively about the Irish Brigade and those who had fallen:

‘Let us praise those glorious men who have fallen, for they were our countrymen and our fathers, the bone of our bone, the flesh of our flesh, and let their memory live amongst us forever. Brethern, here we are today assembled before the altar of the Living God, to pray and to weep for those who have fallen in battle, our fellow-countrymen, our brethern at all events; and, who, as many among us can say, have been nearest and dearest to their hearts, and who have been bone of their bone and flesh of their flesh. Can I, too, not feel emotion in recollecting all those who have fallen, from the first day the Green Banner passed down Broadway. Oh, yes! let us praise them, for they were true men and true Christians. They were true men, those fallen soldiers of the Irish Brigade, and their adopted country shall ever more praise them and honor their memories.’ (6)

Father O’Reilly continued by informing those present why these men were true, and the pride that their families, the Union and Ireland could take from their sacrifice. Speaking directly to the families of the dead, still coming to terms with the loss of their loved ones, he attempted to provide some comfort:

‘And you, families of the departed members of the Irish Brigade, you may well be proud of their memory, and the inheritance of virtue and honor they have left you. Many a father among us might have seen his hopes extinguished every day, and the son whom he loved best fall in some obscure and unholy strife; but when the father, the husband and the son lays down his life in a noble cause- and when by doing so, in the highest patriotic spirit, he ennobles that cause, then I say that his family to the latest generation have a right to boast of his life, to resound his fame and to emblazon his name upon the walls of their household.’ (7)

Delmonicos Restaurant to which the Irish Brigade and 69th NYSM officers retired after the Requiem Mass (New York Public Library Digital Gallery Reference 0340-A1)

Following the sermon the Reverend Dr. Starrs intoned the Requiem and Absolution, after which the mass ended. It was reported that many of the congregation remained in the Cathedral long after the ceremonies had concluded. The officers of the Irish Brigade and officers of the 69th New York State Militia retired to Delmonicos restaurant on Fifth-Avenue. Here General Meagher presented the 69th NYSM with ornate resolutions from the Irish Brigade, acknowledging the services of the militia in paying the funeral costs of the Brigade’s fallen when the bodies had returned to New York. Meagher then spoke to the assembled officers:

‘We have but two wants to-day- one for the dead, and the other for the living. To the dead we have paid our tribute this morning, and listened to the eulogy so eloquently pronounced by my reverend and revered friend, the old chaplain of the Sixty-ninth. I feel that any word I can say in reference to my lost officers and men would be improper, because it would be superfluous. But I will exercise the privilege of being the host on this occasion and avail myself of the opportunity to say that war for me has no attractions beyond those developments which it gives for heart, mind and genius, and the most remarkable and delightful and consoling recollection with me, to my wife, my family and my friends, is the memory of the charities, the amenities, the sweetness of disposition I have seen- and which, in my ignorance, I never gave human nature the credit of possessing, I have seen what we are taught to regard as the rebel soldier, receiving the cup to assuage his parching thirst; I have seen the Federal arm bind his wounds; I have seen friendly and kindly words uttered, and I believe that even on the terrible battlefield there has been more done to cement this Union of American people than anywhere else. I give you The Stars and Stripes, and the heroism of both armies.’ (8)

This received loud cheers, and the festivities continued after Meagher’s speech with a series of toasts. Over the coming days the officers of the Brigade would return to their camps, readying themselves for the next offensive. They were soon to face the battlefields of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg- engagements which would add to the ranks of the fallen ‘glorious men’ of the Irish Brigade.

(1) Irish American January 1863; (2) Ibid; (3) Irish American January 1863; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; (8) New York Times;

References & Further Reading

New York Irish-American January 1863. The Dead of the Irish Brigade

New York Irish-American January 1863. The Dead of the Irish Brigade. Solemn Requiem Mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral

New York Times January 1863. The Dead of the Irish Brigade. Grand Requiem Mass at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

New York Public Library Digital Gallery

Filed under: Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: Delmonico, Fredericksburg, Irish American, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, New York, Requiem, Thomas Francis Meagher

January 18, 2013

The Next Big Thing

I was recently approached by a friend, Michael J. Whelan, to participate in an online blogging chain where writers describe their upcoming projects. Michael is a writer and poet as well as a military historian- he served with the Irish Defence Forces as a Peacekeeper in Lebanon and Kosovo, and has published on the Battle of Jadotville, where Irish soldiers became engaged in the Congo in 1961.

Although this style of post is a departure from what I normally put up on the site, after some reflection I thought it might be a means to discuss some of the current and future projects I want to work on.

My Next Big Thing

I have a tendency to work on a number of projects concurrently, until one emerges from the pack to take precedence over the others. At present I have four main areas I am looking at. These include the Irish-born Medal of Honor Project that I outlined here, which I hope will shed some light on the lives of these men and their families. As well as that I am about to start looking at Irish-born Generals in the Union army, to include the commissioned Generals (12 in total) and the breveted Generals (32 in total). Some of these men are not well-known but led quite remarkable lives. The final two areas are collections of eye-witness accounts. I intend to compile a range of these accounts for the Irish in the American Civil War and also Irish Redcoats in the British Army from the 17th to 19th centuries.

What is the Working Title of your book?

At the moment I think it probable that the next publication I will look to complete will be the Irish accounts of the American Civil War. I am using the working title ‘Irish Voices of the American Civil War.’

Where did the idea come from for the book?

General history readers often relate more to eye-witness accounts than to any other form of historical delivery. The American Civil War produced many Irishmen and women who recorded their experiences before, during and after the conflict. This combination should hopefully be of interest to readers, and further raise the profile in Ireland of the experiences of the 1.6 million Irish in the United States at this time.

What genre does your book fall under?

Historical non-fiction.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

The Irish experience of the American Civil War through the words of those who were there.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

In the case of my first book which is coming out in February in the region of 6 months, although I had carried out a large amount of the background research prior to that.

What other books would you compare this book to within your genre?

For the ‘Irish Voices’ concept it would be the likes of Ian Fletcher’s Voices From the Peninsula and Jerome A. Greene’s Indian War Veterans.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

As with all my writing on the American Civil War, be it on the blog or for publication, it is principally the fact that the impact this conflict had on Irish people has been largely forgotten in Ireland, and it certainly does nor receive the historical attention in Ireland it deserves given it’s scale.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

I am fascinated by the social impacts of the American Civil War on the Irish, both at an individual and community level. With this in mind I try to look beyond simply the battlefield and the confines of 1861-1865. What were Irish views before the conflict? How did they feel about it afterwards? How did change the lives of those involved?

When and how will it be published?

I intend to spend the next year of so putting the research together, with a view to exploring publication options in 2014.

It is customary to tag other writers to continue the chain, which I hope to do in the coming days. I will also have more news on the site shortly regarding the publication of The Irish in the American Civil War by The History Press Ireland.

Filed under: Update Tagged: American Civil War Ireland, Irish American Civil War, Michael Whelan, Next Big Thing, Publication, Writing

January 9, 2013

Medal of Honor: Private Patrick Ginley, 1st New York Light Artillery

The 25th November 1890 was undoubtedly one of the proudest days in the life of ‘Paddy The Horse.’ That evening the man from the west of Ireland was a guest at an Irish Brigade reunion being held at the Riccadonna Hotel, 42 Union Square, New York. The main event was to be the presentation of the Congressional Medal of Honor to Ginley, for actions he had undertaken on 25th August 26 years previously, at the Battle of Ream’s Station, Virginia in 1864. (1)

Patrick Ginley was ‘proud of being a Connaught man.’ He was born around 1822, and it may be that he is the ‘Patricius Ganly’ recorded as being baptised in Aghanagh, Co. Sligo on 10th October 1823. Patrick did not make his way to the United States until he well into his thirties, but by then he had already made many forays into the world. In 1883, he remembered:

Before I came to this country I saw active service in the Crimean war. Among the engagements I participated in were Balaklava, Inkerman and Sebastapol. At the breaking out of the Indian Mutiny in 1857, I volunteered with the 18th Royal Irish Infantry and served through the insurrection, being at the storming of Lucknow and Delhi. I was discharged at Aldershot in 1858 and in 1859 I came to this country. (2)

After his arrival in the United States Patrick gained employment with Dr. Pierre Van Wyck, with whom he remained until the outbreak of war. With the arrival of the conflict and the need for experienced martial men, Ginley enlisted for three months in Company K of the 69th New York State Militia, fighting at the Battle of Bull Run. He then decided to join the 14th New York Independent Battery, enlisting for a period of three years. It was as an artilleryman that he spent the rest of his war service, fighting in fourty-four engagements involving the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps. It was on 25th August 1864 that Patrick Ginley performed the actions that earned him the Medal of Honor. (3)

The Battle of Ream’s Station was the worst day in what was a long war for the Second Corps. Winfield Hancock’s men had been sent south by Grant from the Petersburg siege lines in order to tear up track along the Weldon railroad. Unwilling to allow the destruction to proceed unopposed, Robert E. Lee ordered a Rebel force under A.P. Hill to take a force and engage the Yankees. With Hill feeling unwell, Major-General Henry Heth led the decisive Confederate charge on 25th August which smashed into Hancock’s ill-prepared position, and sent many of the Second Corps to flight. There was little denying that the Second Corps had not been properly prepared to face the onslaught; although Hancock desperately tried to recover the situation, he was eventually forced to retreat.

By the time of Ream’s Station, Private Patrick Ginley was serving as an orderly with the 1st New York Light Artillery. When the Rebels struck, his Captain ordered him to seek out General Hancock and bear him a message. Mounting up, Ginley rode through the railroad cut and first encountered division commander General Miles, to whom he delivered the message. As Miles reached for the note, he was struck and slightly wounded by a bullet. Ginley remembered: ‘Well. I never saw such a face as he made when he was struck by that bullet.’ Returning to his unit, the Irishman would soon be sent on another errand, but with the Rebels beginning to break through around him, his task would become even more perilous. (4)

This time Ginley was told to accompany a Colonel on a mission to discover the nature of the Confederate dispositions around them. Ginley again found himself heading for the railroad cut, but by this time the Rebels had forced the Federals to retreat from their breastworks, exposing both men to capture. Ginley was riding some yards behind the officer:

‘He had just got into the cut and almost out of sight when I saw his leg lifted over the saddle. I knew that he had been taken prisoner. The confederates had gained the spot. I just wheeled around, but had ridden only a short distance, when my horse was shot from under me. I lay there thinking that my leg was broken. My sabre handle was sticking into my ribs and my revolver was jammed in my back. While I lay there between the two lines I could hear every order given on both sides. Finally I cut the strap and extricated myself, when I discovered I did not have a scratch on me.’ (5)

Patrick Ginley took in his situation. The abandoned breastworks were now swarming with Confederates, with Yankees streaming back across the cut. Crawling along the breastworks he came across another Union solder:

‘I motioned him to follow me. We reached one of our guns, I threw in more than an average charge of canister and told him to put his finger on the vent. I don’t know whether he was shot through the heart, or where. At any rate he fell dead without saying a word. I pulled the lanyard and ran. Why, do you know that that gun recoiled so much that I found it right at my heels while I was running at my best speed, and I could run, too. As I ran I saw the color-bearer of a Massachusetts regiment wave the standard, when the staff was struck and broken off and the man struck down. I picked up the colors, gave them one wave and shouted, ‘Follow me, boys.’ A large number followed and rallied to the attack. ‘ (6)

Private Patrick Ginley fires at advancing Confederates, Battle of Ream’s Station (Story of American Heroism)

The Confederate who had shot Ginley’s makeshift assistant had been close enough to roar ‘Come out of that, you blasted Yankee’ before firing. When Ginley returned fire with the cannon, the effect of The Irishman’s shot was devastating- mowing down a swathe of the enemy along the breastwork. Having run the gauntlet back to his own troops, his subsequent rallying cry and dash towards the enemy with the Massachusetts regiment colors was, according to the New York Herald ‘…the perfect representation of a wild Irishman. He appeared to think that it was himself alone that the enemy was fighting and he conducted himself accordingly.’ (7)

Patrick Ginley’s actions were immediately noted by his superiors. Even Ulysses S. Grant was impressed. Speaking of Ginley, the Lieutenant-General in command of all Union forces had the following to say:

‘Private Ginley, it is not to-day nor to-morrow that you and every man undergoing the hardships of this war will be remembered by the country for his services. But every hero sooner or later receives his just reward. In this day of history making, when the deeds of individual valor are taking their places in the record of the War of Rebellion, when the records are in the hands of those at Washington who helped to make them, each individual act of heroism of which there is a record will be recognized.’ (8)