Damian Shiels's Blog, page 52

July 7, 2013

‘Rather a Monotonous Affair’: An Irishman on the Union Blockade

The Union navy often does not receive the attention it deserves when it comes to the American Civil War. This is particularly true of the Irish involvement; the Irish contribution to the Union navy was proportionately greater than that to Union armies. Of the 118,044 men who served as Union ‘Jacks’ during the war, some 20% were Irish. Many served in the unglamorous blockading squadrons that attempted to stifle Confederate trade along the Confederacy’s Atlantic and Gulf coasts. One of them described what it was like. (1)

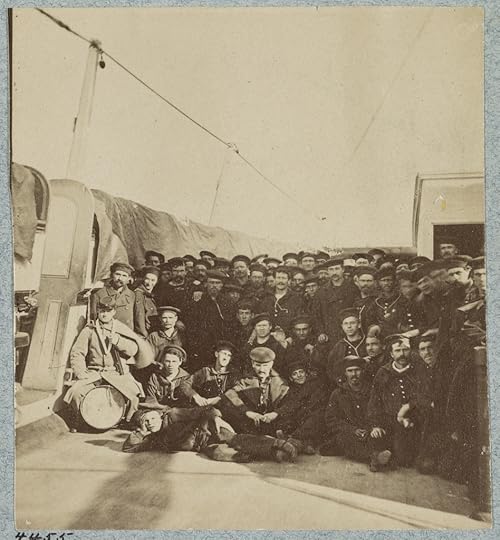

The crew of the U.S.S. Colorado, another member of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron (Library of Congress)

Life on the Union blockade was characterised by depressing monotony, with a seemingly never-ending daily routine only occasionally interspersed with efforts to run down Rebel blockade-runners- a task which more often than not ended in failure. Acting Assistant Surgeon George B. Higginbotham served on board the U.S.S. Grand Gulf, part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron off the Confederate port of Wilmington, North Carolina. The Irishman occasionally described life on the blockade for readers of the New York Irish-American. In a letter of 20th July 1864 he told of the trials of life on the blockade:

Gentlemen- In the absence of any definite, tangible news to send, I have ventured to enclose you a summary of what we have not been doing and my cogitations thereupon. You are aware that life in a “man-of-war,” unless she is occupied in fighting, or catching prizes, is rather a monotonous affair, and we prove the truth of this assertion every day, for about all we have to do is, as Shaftesbury says-

“To love the public, to study universal good, and to promote the interest of the whole world, so far as lies within our power.”

Mails from New York are getting extremely irregular; the last batch of papers which came brought us the tidings of the capture and sinking of the privateer ‘Alabama’, which, in the face of the many canards published, is almost too good to be true; but which ought to have been done two years ago. Yet, “better late than never.” We have rumors of the ‘Florida’ being in our proximity. If we could only get a glimpse of her we would send our “cartes-des-visites” on board in a hundred-pounder shell. If it were a possible thing to do so; and after that would feel quite satisfied (provided she went to Davy Jones’ locker), to come to New York for a week or two. But Deo Volente [God Willing].

The blockade is bordering on rather inefficiency at just this present time, as scarce a night passes that a blockade-runner does not get in, and as many come out: and when we get a chance to drive a shot through them, it seems as if fate was against us. Two or three nights since, one our fleet saw a blockade-runner trying to get in. The captain challenged; received no answer, and then gave the order to “fire.” But it seems by accounts that the captain of the gun could not find his primer; and, after that, he could not find the “vent-hole,” because of the dark; so by the time he was ready to fire, the Anglo-rebel was nicely out of range up to Wilmington.

I will bet a small amount that the captain of that gun was not an Irishman; for Irishmen never miss finding a place in the night time when they want to look for it. The ‘Grand Gulf’, however, is all right. When we see a thing in the shape of a “runner” we give her as much as she wants either in speed or metal, though having broken our propeller while chasing the ‘Young Republic’, we have lost a trifle of our former superiority. (2)

Life was sometimes fulfilling for the blockaders. A few months previously (6th March, 1864) Higginbotham had penned more positive news for the readers back home:

Gentlemen- I wish to inform you and your readers of the Irish-American that we are doing something on the Blockade. After a very exciting chase of three hours and thirty minutes, we have just captured the very fast side-wheel Anglo-rebel steamer ‘Mary Annie’ (blockade runner), one day from Wilmington to Nassau. We sighted the ‘Mary Annie’ at daylight, and chasing dead to windward forced her to throw overboard much of her cargo of cotton, and she, although light and in perfect running order, was overhauled and captured in a stern chase , “which is notoriously a long one,” by one of those very cruisers which the enemies of the Government have made so much ado against. This also corroborated the character of the ‘Grand Gulf’, in regard to the capture of the ‘Banshee’, the credit of which was given so hastily to the transport steamer ‘Fulton’, but which, like the present capture, was, under the goodness of God, owing to our superior speed , our hundred-pounder Parrot, and the intelligence of our noble commander, Geo. B. Ransom.

We return thanks to those of the Navy Department who furnished us the necessary repairs; and we assure you, Gentlemen, and those who read your very valuable journal, that we are after another ‘Mary Annie’. I regret that I cannot meet you on the 17th inst. Remember me when you are celebrating the National Anniversary. “Tho’ lost to sight to memory dear.” (3)

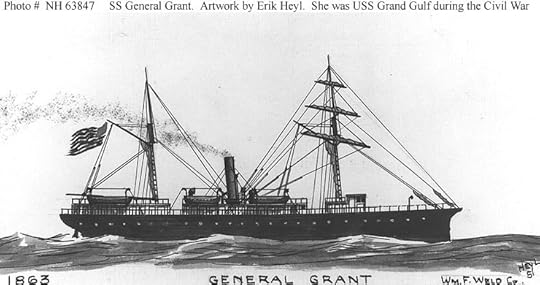

The U.S.S. Grand Gulf as she appeared after the war, when she had been renamed the S.S. General Grant (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Many Union sailors lived in hope of the prize-money they would share if they were fortunate enough to capture a blockade-runner. Given the numbers of Irishmen in the service, Higginbotham expressed his hope that those who had secured a prize would remember those across the Atlantic:

Some of our boys in the steamer are already counting up their prize money by hundreds of dollars. I sincerely hope that they will remember, many of them, at least, their friends in the old country; for it seems as if there was never a more favorable opportunity for young persons to come to this country. There is plenty of room and plenty of work here; and if the emigrants can only get solidly started, they can go on without much trouble for the future…There is many a poor acquaintance in “ould” Ireland, to whom the accession of a pound or two given would be an act of charity which would be blessed of God; and yet would not be missed out of the purses of those giving it. No doubt, when the vessel is paid off, by many of our lads, the Irish at home will be remembered. (4)

George B. Higginbotham would go on to serve aboard the U.S.S. Union later in the war. That he was highly regarded by his comrades is clear from an account written by Francis McDermott, who had served as Master Machinist at the Union’s Key West base in Florida. While serving there Higginbotham had seemingly gone the extra mile for his patients, at times giving up his own bed so that ill sailors could avail of it. When the men of the U.S. gunboat Alabama had been struck down by yellow-fever, it’s Commander spoke of the doctor’s ‘skilful and unremitting attention’ towards the sick. Even after the war was over he remained on the Atlantic coast. In 1866 on Tybee Island, Georgia he was active in the Quarantine Hospital where a cholera outbreak was killing up to 17 people a day. Dr. Higginbotham survived to return to his home in New York, and in late 1866 he was finally able to resume his medical practice at 142 Court Street, opposite Dean Street in Brooklyn. (5)

(1) Bennett 2004: 5, 9; (2) Irish-American 6th August 1864; (3) Irish-American 9th April 1864 (4) Irish-American 6th August 1864; (5) Irish-American 17th September 1864, Irish-American 26th September 1863, Irish-American 7th December 1866;

References

Bennett, Michael J. 2004. Union Jacks: Yankee Sailors in the Civil War.

New York Irish-American 26th September 1863. Dr. G.B. Higginbotham.

New York Irish-American 9th April 1864. A Voice From the Navy.

New York Irish-American 6th August 1864. A Voice From the Navy.

New York Irish-American 17th September 1864. Surgeon George B. Higginbotham.

New York Irish-American 7th December 1866. Dr. George B. Higginbotham.

Filed under: Navy Tagged: Blockade runner, Irish American Civil War, Irish Sailor, New York Irish-American, North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, U.S.S. Grand Gulf, Union Blockade, Wilmington

July 3, 2013

In Search of Willie: Seeking John Mitchel’s Son After Pickett’s Charge

John Mitchel was an Irish revolutionary who had been deported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1848. He escaped to America in 1853 and settled initially in New York. Mitchel found himself increasingly disillusioned with the form of capitalism he felt was being practised in the Northern States, where large numbers of people lived in poverty. He moved South before the war, becoming a strong proponent of slavery and supporter of the Confederacy. His three sons all fought in the Confederate Army, and the youngest, Willie, participated in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. When Willie was reported missing in action, it precipitated an unusual alliance of the Northern and Southern Irish press as they sought his whereabouts.

The area of Pickett’s Charge, Gettysburg (Wikipedia)

Early news of Willie being missing came on 13th July when the Richmond Daily Dispatch brought information on the casualties in the First Virginia Infantry. Willie was notable even then; he is the only non-officer to be mentioned in the initial list from Gettysburg:

‘The 1st Virginia carried in 175 men, about twenty five having been detailed for ambulance and other duty. They brought out between thirty or forty, many even of them being wounded. There is but one officer in the regiment who was not killed or wounded, and that was Lieut. Ballou, who now commands it. Col. L. B. Williams went into action on horseback and was instantly killed. He fell forward on being shot, and did not speak afterwards. His horse was hit three times. Col. W’s body is in the hands of the enemy. Among the officers we have ascertained the following losses: Company G, Lieut. Morris, comd’g, Capt. Langley was sick but went into the fight and was wounded; Lieuts Woody and Morris, all wounded; company B, color company, Capt. Davis, wounded and missing; Lieut. Paine, wounded; company C, Capt. Hallinan and Lieut. Dooley, both wounded and missing; company D, Capt. Norton, Lieuts. Reeve, Keiningham, and Blair, all wounded; company H, Capt. Watkins, Lieuts. Cabell and Martin, all wounded; company I, Lieuts Ballou and Caho, the latter wounded. Wm. Mitchell, son of John Mitchell, in command of the color guard of the regiment, is wounded and missing. Lieut. Blair, of company D, commanded the skirmishers. We have been unable to get a list of the privates killed and wounded.’ (1)

John Mitchel and his family were understandably desperate to hear news of their son. John’s position as a hero of Irish nationalism still carried weight among the Irish in the North, and allowed them to seek information Union soldiers might have on their boy. The New York Irish-American brought this request to the northern Irish community on 29th August:

‘A correspondent writes to us from Maryland requesting us to relieve the anxiety of an old friend by “communicating publicly the fate of Private William Mitchel, who fell on the field of Gettysburgh, killed or wounded.” If any of our readers can inform us whether such a person was among the Confederate prisoners taken at Gettysburg, or otherwise, we shall feel obliged by a communication of the facts as speedily as possible.’ (2)

However the Mitchels’ hopes were dashed in September. The Richmond Sentinel brought the news that John Mitchel and his family were dreading, weeks after the event:

‘We are sorry to learn that Wm. Mitchel, youngest son of John Mitchell, Esq., editor of the Enquirer, who was reported missing after the battle of Gettysburg, is now believed to have been killed in that hard-fought struggle. Young Mitchel was only eighteen years old, and is represented to have been a young gentleman of fine attainments, and an excellent soldier, and behaved with especial gallantry at Gattysburg. He has two brothers in the Confederate Service.’ (3)

The New York Irish-American, despite being a pro-Union northern newspaper, joined in the mourning for the Irish nationalist’s son, despite the fact that he had been a Confederate. On the 12th September they wrote the following eulogy:

JOHN MITCHEL’S YOUNGEST SON

‘We have received with sincere sorrow the intelligence that William Mitchel, the youngest of John Mitchel’s sons, fell mortally wounded on the battle-field of Gettysburgh, shot through the lower part of the abdomen. He was in the color-guard of the 1st Virginia regiment, and fell near the breastworks held by the 3d corps, in the last desperate charge which Longstreet’s troops made upon the position. He was a young lad of the highest promise, and never failed to endear himself to those with whom he was brought in contact, by the sterling goodness of his disposition and the many excellent traits of character he displayed. Few who remember the bright, open-hearted boy, who, three short years ago, was the life of a yet unbroken family circle in the vicinity of this city, but will join in the regret with which we now record his untimely fall upon a field where brother strove with brother in deadly conflict that could bring naught of good to either. Mr. Mitchel’s family have been sorely afflicted within a few short months. It is but the other day we had to chronicle the death of his eldest daughter in Paris; and now another of his children has gone to his last rest, far from home, and from the friends whose ministrations, at least, might have made lighter the steps that lead to the grave.’ (4)

News spread to Ireland of Willlie’s death, and was reported in the Dublin Nation of 26th September:

‘Amongst the sons of Ireland whose blood was poured on the slaughter-field of Gettysburg, was one whose fall will be learned with sorrow in many an Irish home. William Mitchel has given his young life in the cause to which his father early devoted his whole heart and his great intellect; and surely if there is to be at this moment a grief keener than all other in the parental heart of the brave exile, it is that the life of his second-born, so gallantly yielded on the battle-field, was not given, as Sarsfield said, “for Ireland.” to the Irish-American, of New York, we are indebted for the sad tidings which are conveyed in the following touching record: [There followed a reprint of the Irish-American eulogy]

Honor to the kindly heart that dictated , and the friendly hand that traced , those lines! Honor to the journal which, though within the Union lines, and consistently defending the Union cause, has not imitated those Irishmen who would depict John Mitchel’s son as fighting against Ireland, and “doing the work of Ireland’s foe!” it is mournful to think that over the bier of the young exile, thus bravely fallen as befitted his name and race, voices should be raised to poison against him the sympathies of his countrymen at home! But it cannot be done while faith remains and memory survives in the Irish heart. In the land for whose liberation his father staked his life as boldly as he at Gettysburg, young William Mitchel will, for his own and his parents’ sake, be mourned truly and lovingly. Ireland claims with equal affection her children in America, whether they be ranked under the Northern or the Southern banner; she claims with equal pride the gallant hearts who exhibit the ancient heroism of the race amidst the battlefield’s appalling scenes, whether they be “Confederates” or “Federals.” Whether they strike for North or South, they strike from a true man’s motive; they serve the free home of their adoption, and renew their claim to that proud testimony borne of their fathers of yore- “Always and everywhere faithful.” ‘(5)

Willie Mitchel’s death in Confederate service appeared to have united in mourning many Irish in the North and South as well as at home in Ireland. Many wished to extend their condolences to Willie’s highly respected father. This did not go unnoticed by the rest of the Northern press. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper recorded on 24th October:

‘The Irish papers mention with peculiar regret the death of John Mitchel’s youngest son, William, aged only 17, who fell fighting for the Rebels at Gettysburg. He was, by all accounts, a noble youth, and has evidently been sacrificed to his father’s insane desire to possess a plantation. Seldom has a man been more heavily punished for his apostacy than John Mitchel.’ (6)

Some papers, such as the New Haven Palladium, were even less charitable. They recorded the confirmation of Willie’s death briefly:

‘John Mitchel’s youngest son William was killed at Gettysburg. Pity it had not been the young man’s father.’ (7)

Willie Mitchel died during ‘Pickett’s Charge’, 150 years ago today. Though his father’s views on slavery and the South had divided many, his loss was widely acknowledged by the Irish nationalist community wherever they were based, be it North, South or at home. For John Mitchel worse was to come- his eldest son would later be killed while commanding Fort Sumter, mortally wounded where the war had begun in 1861.

(1) Daily Dispatch 13th July 1863; (2) Irish-American 29th August 1863; (3) Macon Telegraph 17th September 1863; (4) Irish-American 29th August 1863; (5) Irish-American 24th October 1863; (6) Frank Leslie’s 24th October 1863; (7) New Haven Palladium 17th September 1863

References

Richmond Daily Dispatch 13th July 1863. ’Description of Friday’s Fight- The First Virginia Regiment at Gettysburg’

New York Irish-American 29th August 1863. ‘William Mitchel’

Macon Telegraph quoting the Richmond Sentinel 17th September 1863. ‘Wm. Mitchel’

New York Irish-American quoting the Dublin Nation 6th September 1863. ‘Fallen on the Battle-Field’

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 24th October 1863. ‘Obituary’

New Haven Palladium 17th September 1863. ‘John Mitchel’

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, Derry, Virginia Tagged: 1848 Rebellion, First Virginia Infantry, Irish American Civil War, John Mitchel, New York Irish-American, Pickett's Charge, Willie Mitchel, Young Ireland

Irish Examiner Feature: Remembering the Irish Lost at Gettysburg

As many regular readers of the site will know I have been campaigning for some time (along with colleagues) to see greater recognition in Ireland of the cost of the American Civil War to the Irish community. It was the second biggest conflict in terms of numbers in which Irishmen served in uniform, yet we have no memorial. Despite repeated efforts the State has failed to take any steps to acknowledge the 150th anniversary of this important event in Irish history. As I have said before, I find the official apathy with which we seem to regard the Irish role in this conflict at odds with the consistent promotion of ‘The Gathering‘, aimed at welcoming the diaspora home to Ireland. I strongly believe that more than simply inviting the diaspora home we have an obligation to embrace our diaspora’s history and acknowledge that it is a central part of the Irish story.

I sought a number of weeks ago to get a feature piece in one of our national newspapers to coincide with the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg, and I am delighted to say the Irish Examiner took this offer up. The feature ran today and you can read it here. Unfortunately a couple of units (the 1st Virginia, 69th Pennsylvania and 42nd New York) lost their designations between page and print, but this is a minor aspect- I am very happy that the Examiner decided that this was a story worthy of highlighting. Hopefully it might be another small step towards wider recognition of the conflict in Ireland.

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, Discussion and Debate, Media Tagged: American Civil War, Battle of Gettysburg, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Examiner, New York, Pennsylvania, The Gathering

June 30, 2013

Reporting the Gettysburg Casualties of the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade

The Irish Brigade went into action at Gettysburg on 2nd July 1863. They did their fighting in the Wheatfield, one of the most infamous sections of the battlefield. The already depleted brigade suffered some 200 casualties. One of the brigade’s regiments that fought at Gettysburg was the 63rd New York Infantry. On 6th July the 63rd’s Adjutant, Miles McDonald, wrote to the Irish-American newspaper in an effort to let those at home in New York know the human cost of the fighting in Pennsylvania.

Federal Soldier Disembowelled by a Shell, Rose Woods, near The Wheatfield, Gettysburg (Library of Congress)

The “Irish Brigade” at Gettysburg

Headquarters, 63d Battalion, N.Y.S.V.,

Near Two Taverns, Penn.,

July 6, 1863.

To the Editors of the Irish-American:

Enclosed I send you the list of casualties of the 63d Battalion, N.Y.S. Vols., during the late engagement with the enemy near Gettysburg, Pa., July, 2d and 3d, 1863, for publication. It is as correct as can at present be ascertained, although some of the men reported missing may yet be found.

The Battalion fought splendidly, driving the enemy from the position they had taken, and the “Irish Brigade” by their courage and bravery in the late fights, nobly sustained the honor of the land which gave them birth.

KILLED- Company A- Privates Charles Hogan, Patrick Kenny, John O’Brien. Company B- Privates William Moran, Edward Egan.

WOUNDED- Lieut. Col. R.C. Bentley, leg, slightly. Company A- Sergt. Thomas Murphy, abdomen, severely; James Crow, hand, slightly; Hugh Meehan, side, severely; Peter Walsh, side, severely. Company B- Corporal John O’Halloran, hand, severely; Privates John Graham, thigh, severely; Daniel Hickey, hip, slightly; John Hartigan, hand, slightly.

MISSING- Company A- Corporal Daniel E. Looney; Privates Timothy Manly, Patrick McGeehan, Thomas Kelley. Company B- Lieut. Dominick Connolly, Privates Michael Kelley, John Murphy, Michael Sheehan.

RECAPITULATION- Killed, 5; Wounded 10; Missing, 8- Total, 23.

Very respectfully your obedient servant,

Miles McDonald. Adjutant, 63d N.Y.S. Vols. (1)

The rosters of the 63rd New York provide further detail on the regiment’s casualties at Gettysburg. The men who were listed as dead included those killed outright in the Wheatfield on July 2, such as 21-year-old Charles Hogan and 37-year-old Patrick Kenny. John O’Brien had lingered for a day before passing away from his wounds on 3rd July. These early reports from the field often contained mistakes- one can only imagine the impact such errors had on the families of the soldiers. Such was the case for William Moran, a 26-year-old listed as killed in action. He had in fact survived, captured on the 2nd. Paroled on 28th December 1863, he returned to the front and mustered out at the end of his term at Petersburg on 31st August 1864. The same also appears true of Edward Egan, listed as killed, but who also survived to muster out on 21st August 1864. (2)

What of those listed as wounded? Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Bentley survived and was discharged for disability in 1864. The severely wounded 20-year-old Sergeant Thomas Murphy managed to survive his Gettysburg wound and re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer. However, Thomas had clearly had enough of war; he deserted from the army during his veteran furlough in March 1864. James Crow who had been wounded in the hand was suffering his second battle injury, having been previously shot at Antietam. He also survived and was transferred to the Veteran Reserves in February 1864. Hugh Meehan pulled recovered from his severe wound and would fall to enemy fire again at the Wilderness. He also ended the war in the Veteran Reserves. Just as errors could be made in listing men as killed when they had in fact been wounded or captured, so too could early reports offer hope when there was none to be had. By the time Miles McDonald wrote his brief outline to the Irish-American on 6th July, 35-year-old Peter Walsh had already died of the wounds he had received in the Wheatfield. There was no further record of John O’Halloran after Gettysburg; he may have died from his wounds, been discharged due to wounds or deserted. John Graham survived his wound, as did Daniel Hickey. 20-year-old John Hartigan who was reported as slightly wounded was not so fortunate. He died from wounds at Satterlee Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 9th December 1863. (2)

The final category of men were those reported missing. Corporal Daniel Looney had already been captured at Malvern Hill and wounded at Antietam before being captured at Gettysburg on 2nd July. His luck had run out- Daniel died of disease in Hospital No.21, Richmond on 1st December 1863. There was no further record of Timothy Manly following his capture at Gettysburg, and he may well have been among the fallen. Patrick McGeehan succeeded in getting back to his regiment and reenlisted as a veteran volunteer. Like Thomas Murphy the 28-year-old deserted during his veteran furlough. Thomas Kelly had been captured in the Wheatfield, was exchanged and eventually mustered our before Petersburg in 1864. 25-year-old John Murphy had also been captured on 2nd July, and like Daniel Looney he would not survive. He died of disease in Richmond on 30th December 1863. Michael Sheehan was another man for whom there was no record beyond his disappearance at Gettysburg and his ultimate fate remains unknown. (3)

Given the confusion of the fighting it is unsurprising that Miles McDonald made some mistakes in his communication and that some men were not mentioned at all. These included soldiers like 19-year-old Dominick Connolly who was captured but survived; 35-year-old Laurence Cronin was wounded in the Wheatfield and was discharged from the service as a result the following August. Peter Flanaghan had seen enough at Gettysburg to make up his mind about his future. He deserted from the army on 4th July, the day after the fighting stopped. Peter Hannigan had the same idea- he went AWOL on 5th July. What of the adjutant who wrote to the Irish-American on 6th July? Miles McDonald had been just 23-years-old at Gettysburg. He was destined not to survive the war; he fell wounded at Petersburg on 16th June 1864, dying the following day. (4)

(1) New York Irish-American 25th July 1863; (2) New York Adjutant General Report; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.;

References & Further Reading

New York Irish-American 25th July 1863. The “Irish Brigade” at Gettysburg

Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901

Gettysburg National Military Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Gettysburg, Irish Brigade Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Battle of Gettysburg, Casualties of War, Gettysburg, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, New York Irish-American, Wheatfield

June 29, 2013

The Ages and Origins of the Union’s Irish Soldiers

In 1869 Benjamin Apthorp Gould published Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers. Very much a scientific work of its time, it explored topics such as the nativity and ages of Union volunteers together with examinations of physical characteristics such as stature, complexion, dimension and proportions of the head and pulmonary capacity, to name a few. The Irish are frequently referenced in the work; this post concentrates on the data regarding the States where Irish soldiers enlisted, what age they were when they did so and how tall they were.

Gould’s data was garnered from the records of the Sanitary Commission, and was partly based on the efforts of Irishman T.J. O’Connell, a graduate of University College Dublin. After he left the Union army O’Connell had served as Chief Clerk of the Statistical Bureau in the U.S. Sanitary Commission from the summer of 1863 until April 1865. Ill health brought on by his military service had forced his resignation, and eventually led to his death. Gould specifically acknowledges O’Connell’s contribution towards compiling the data upon which his study was based. (1)

Among the fascinating range of tables in Investigations are statistics on the stature of natives when compared to the Irish and Germans. Thus we can learn that the average height of the 746 Irishmen who enlisted in New Hampshire was 66.610 inches (5.55 feet) compared with 66.373 inches for Germans (5.53 feet, based on 299 recruits) and 68.418 inches for natives (5.7 feet, based on 5,239 recruits). (2)

The table in Investigations that looks at the comparative distribution of Irish soldiers by age examines data based on 83,128 records. The information serves to provide a glimpse of the age profile of Irish-American soldiers in Northern armies.

Age Last Birthday

Total in United States Army

Below 17

84

17

187

18

4,345

19

4,519

20

4,095

21

7,550

22

6,445

23

5,235

24

4,360

25 & upward

46,308

Total

83,128

Table 1. Comparative Distribution of Irish Soldiers, by Age (adapted from Table XL, Investigations) (3)

It is striking from the table that the majority of those Irish recorded were over the age of 25, a trend that is seen in many other groups. Information is also available with regard to where Irishmen joined the Northern military. Although it was not possible for the statisticians to exclude bounty-jumpers from their totals (which may have led to some duplication) the figures do provide a picture of the States which provided the strongest Irish contingents. Unsurprisingly New York was overwhelmingly dominant, with over 50,000 Irishmen recorded as enlisting there. It was followed by Pennsylvania, Illinois and Massachusetts.

Place of Enlistment

Number of Irish

Maine

1,971

New Hampshire

2,699

Vermont

1,289

Massachusetts

10,007

Rhode Island & Connecticut

7.657

New York

51,206

New Jersey

8,880

Pennsylvania

17,418

Delaware

582

Maryland

1,400

District of Columbia

698

West Virginia

550

Kentucky

1,303

Ohio

8,129

Indiana

3,472

Illinois

12,041

Michigan

3,278

Wisconsin

3,621

Minnesota

1,140

Iowa

1,436

Missouri

4,362

Kansas

1,082

TOTAL

144,221

Table 2. Nativities of United States Soldiers, by State (adapted from Table III, Investigations) (4)

Aside from comparing physical attributes such as height, eye colour and hair colour between nativities it is also possible to use the tables in Investigations to gain a range of information on a single nativity, such as the Irish. This is the case with the table below on mean height. This information would seem to suggest that the ‘average’ Irishman in the American Civil War was in the region of 5 feet 5 inches tall.

Age

Number

Mean Height (inches)

Mean Height (feet)

Under 17

84

62.586

5.215

17

187

65.344

5.445

18

4,345

65.818

5.485

19

4,519

66.309

5.526

20

4,095

66.612

5.551

21

7,550

66.809

5.567

22

6,445

67.030

5.586

23

5,235

67.071

5.589

24

4,360

67.144

5.595

25

4,679

67.106

5.592

26

3,760

67.131

5.594

27

3,596

67.192

5.599

28

3,994

67.206

5.600

29

2,400

67.202

5.600

30

3,730

67.103

5.592

31-34

7,621

67.242

5.603

35 and over

16,528

67.090

5.590

Total

83128

66.951

5.579

Table 3. Mean Heights of Irish soldiers by age (adapted from Table VI, Investigations) (5)

Naturally much of the information in Investigations has to be treated with due caution, but nonetheless it does contain some interesting data that can be used to increase our understanding of the Irish in the Northern forces during the war. Future posts will explore other aspects of the information in Investigations with a view to reproducing relevant tables in the ‘Resources’ section of the website.

(1) Apthorp 1869: viii; (2) Ibid: 128; (3) Ibid: 182; (4) Ibid: 27; (5) Ibid: 105;

References

Gould, Benjamin Apthorp 1869. Investigations in the Military and Anthropological Statistics of American Soldiers.

Filed under: Research, Resources Tagged: Benjamin Apthorp Gould, Irish Age, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish Height, Irish Soldiers Union Army, Irish State, University College Dublin

June 19, 2013

A Yankee and Rebel Side by Side in Cork Harbour

Cork Harbour is one of the largest natural harbours in the World. This coupled with its strategic location meant that it was of key significance for the British Empire over the centuries. The harbour’s importance to the Royal Navy led to the construction of a major series of defences at key locations around the anchorage. The linchpins of this defence were Fort Carlisle and Fort Camden on opposite sides of the harbour entrance, and Fort Westmoreland (Spike Island) within. When these fortifications were handed back to the Irish State in 1938 they were renamed to honour Irish patriots- inadvertently highlighting the divisions in the Irish community created by the American Civil War.

Fort Mitchel, Spike Island. Fort Davis and Fort Meagher occupy the two headlands on either side of the harbour entrance in the distance. (Courtesy Cork County Council)

The decision was taken to officially name the Forts for three prominent members of the nineteenth century Young Ireland movement. So it was that Fort Carlisle became Fort Davis, Fort Camden became Fort Meagher and Fort Westmoreland became Fort Mitchel. Thomas Davis had founded The Nation newspaper and had written ballads such as The West’s Awake and A Nation Once Again. His death at only 30 years of age meant that he was not involved in the abortive 1848 Young Ireland Rebellion. Such was not the case with Thomas Francis Meagher and John Mitchel, the other men honoured with the re-naming. They found themselves arrested and deported to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) but both would eventually end up in the United States. Meagher escaped to New York in 1852 while Mitchel followed in his footsteps in 1853.

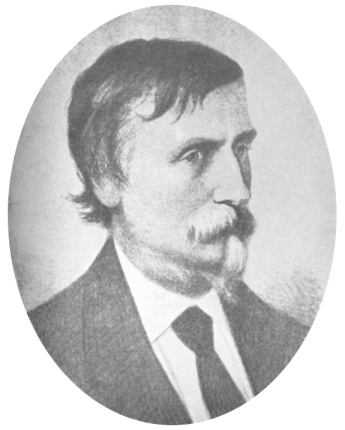

John Mitchel (Jail Journal)

The American Civil War would see the former allies on opposite sides. While Meagher remained in New York and would eventually throw in his lot with the Union, Mitchel took a very different path. Mitchel was disgusted by how capitalism was operating; he saw it as one of the main causes of the Famine and as the creator of terrible conditions for the industrialised poor of the North. At the same time he became a staunch supporter of slavery, the spread of which he supported. He eventually decided to move South to help the Southern cause.

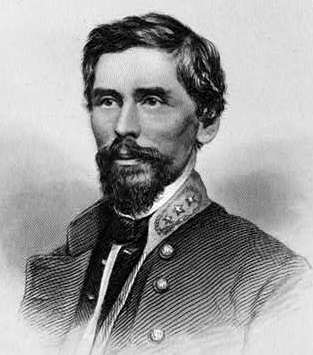

Thomas Francis Meagher (Library of Congress)

With the outbreak of war Thomas Francis Meagher became first a Captain in the 69th New York State Militia and later organised and led the Union’s Irish Brigade as a Brigadier-General. Meanwhile John Mitchel helped with the Confederate Ambulance Corps and later became editor of the Richmond Enquirer and subsequently the Richmond Examiner. The war was not kind to either of the former Young Irelanders. Meagher watched hundreds of his men fall in battle in 1862 and 1863, an experience which undoubtedly had a deep and lasting impact on him. Mitchel meanwhile had seen his sons march off to fight for the South. The youngest, Private Willie Mitchel, died in the ranks of the 1st Virginia Infantry during Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, almost 150 years ago. Willie’s eldest brother Captain John C. Mitchel of the 1st South Carolina Artillery was in command of Fort Sumter, South Carolina when he was mortally wounded during a barrage on 20th July 1864. The middle son, James, also served in the 1st Virginia Infantry and lost an arm during the fighting, but survived the war. James’s son, John Purroy Mitchel, would later become the Mayor of New York.

The former comrades Meagher and Mitchel had given virtually everything to the Northern and Southern causes during the American Civil War. Meagher would die in tragic circumstances in 1867 while serving as Governor of Montana, falling overboard and drowning while on a steamboat in the Missouri River. Mitchel was briefly arrested after the conflict for his wartime activities, settling in New York after his release. He eventually returned to Ireland in 1874 and was elected as MP for Tipperary, but was declared ineligible to hold a seat as he was a convicted felon. He died in 1875.

William Pope, Private, Confederate Army. Original caption notes his service with the Confederates (unit as yet not established) and states he was formerly a warden in Spike Island Prison (Mountjoy Prison Portraits)

Interestingly Fort Westmoreland on Spike Island (now Fort Mitchel) has a number of links to the Irish who served the Confederacy during the American Civil War. John Mitchel himself had been very briefly held here prior to his deportation to Van Diemen’s Land following the 1848 Rebellion. A Fenian called John Pope, arrested in 1866 while attempting to assist in the organisation of a Fenian Rising, claimed to be both a former Confederate soldier and former prison warden on Spike Island. On 1st July 1849 a Private in the 41st Regiment of Foot- Patrick Cleburne- was promoted to Corporal while serving on Spike. During his time on the island Cleburne got into trouble as a prisoner escaped while he was standing guard, but he avoided serious censure. His regiment was also on duty in nearby Cobh in 1849 when Queen Victoria visited, an event which resulted in the settlement being renamed Queenstown. Cleburne would later go on to become the highest ranking Irishman to serve on either side during the American Civil War. As a Major-General in the Confederate Army he became known as the ‘Stonewall of the West’ and has had a city and number of county’s named for him. (1)

Major-General Patrick Cleburne, former Spike Island soldier. Killed in action at Franklin, Tennessee on 30th November 1864 (Library of Congress)

Although the names of Fort Meagher and Fort Mitchel in Cork Harbour are intended to primarily remember these two men’s activities in the Young Ireland movement, they also provide us with an opportunity to recognise Irish involvement in the American Civil War. One was a Yankee, the other a Rebel- together they remind us of the conflict in which nearly 200,000 Irishmen served and which had such a deep impact on the 1.6 million strong Irish community in America.

* Special thanks to Louise Nugent of Spike Island for providing images for this post.

(1) Joslyn 2000:14;

References & Further Reading

Joslyn, Mauriel Phillips 2000. ‘Irish Beginnings’ in Joslyn, Mauriel Phillips (ed.) A Meteor Shining Brightly: Essays on Major-General Patrick R. Cleburne.

Mountjoy Prison Portaits of Irish Independence: Photograph Albums in Thomas A. Larcom Collection

Filed under: Cork, Derry, Irish Brigade, Waterford Tagged: Cork Harbour, Fort Meagher, Fort Mitchel, Irish American Civil War, John Mitchel, Patrick Cleburne, Spike Island, Thomas Francis Meagher

June 12, 2013

Medal of Honor: First Lieutenant Menomen O’Donnell, 11th Missouri Infantry

On the 22nd May 1863 Ulysses S. Grant launched an assault against the Rebel defences at Vicksburg, Mississippi. His previous effort to take the ‘Gibraltar of the Confederacy’ by storm, on 19th May, had ended in failure. Now he was trying again. At around 10 in the morning following an artillery barrage, blue-coated infantry surged forward across a three-mile front. The assault did not succeed. After hours of fighting the Union attack was thrown back, and Grant suffered over 3,000 casualties. Despite the setback feats of gallantry were commonplace; no fewer than eight Irishmen would receive the Medal of Honor for their actions that day. One of them was Donegal native Menomen O’Donnell.

Menomen O’Donnell, c. 1862 (Deborah Maroney)

Menomen O’Donnell was born in Drumboarty, Co. Donegal on 20th April 1830 and emigrated to the United States during the Famine, arriving in America in 1848. Gradually moving further and further west, he eventually settling in Bridgeport, Illinois in 1850. On 7th June 1853 Menomen married Mary Bailey of Towanda, Pennsylvania. The couple would go on to have nine children together, although two would not survive infancy. He did well as a farmer and stock-breeder, and at one point owned over 1,000 acres. His success meant that the family he left in Ireland could join him, and over the course of the 1850s he was able to welcome his brother, sisters, father and step-mother to Illinois. He was even able to take a trip back to Ireland shortly before the war broke out- for Menomen O’Donnell America was fulfilling all his hopes and dreams. (1)

With the outbreak of war Menomen answered the call for volunteers, enlisting in July 1861. As Illinois had filled its quota of men, his company became part of the 11th Missouri Infantry, with whom he would serve for the duration of the conflict. He quickly rose to the rank of Lieutenant and began to demonstrate the courage that marked him out during the war years. During the fight for New Madrid and Island No. 10 in March 1862 he volunteered to take a detachment of soldiers across the Mississippi to silence a newly constructed Rebel battery. One of his men recalled the event: ‘Lieut. O’Donnell said that if they would let him have 12 picked men he would go over and spike their guns. He did and I was one of the 12. We crossed the river at midnight on a dark night and drifted down to opposite the guns, when the rebel sentinel sang out, ‘Who goes there?’ Lieut. O’Donnell told them he was a friend and wanted to see the General in command. At least 1,000 men raised up from behind the guns.’ The Donegal native and his men beat a hasty retreat, and lived to fight another day. (2)

Siege of Vicksburg by Kurz and Allison c. 1888 (Library of Congress)

The 1863 siege of Vicksburg was one of the defining events of the war in the West. It’s capture would split the Confederacy in two and secure control of the Mississippi River for the Union. The 22nd May assault was an attempt to end the siege by force and compel the Confederate army in the city to surrender. For much of that day O’Donnell and the men of the 11th Missouri could only watch as their comrades tried- and failed- to take the Confederate fortifications. Finally, shortly after 4pm, they received orders to launch themselves against the enemy entrenchments in the vicinity of the Stockade Redan. Menomen later recounted the action:

‘The Eleventh Missouri led the advance. The enemy’s guns had been booming for some time, but as soon as the Union advance was seen coming over the bluff, the fire seemed to double its former strength and fury. The ground was covered with the dead and wounded, and not seeing my colors I felt like one lost in the wilderness. I called out: ‘Where is the flag of the Eleventh Missouri?’ A captain of an Ohio company answered: ‘Lieutenant, your flag is over there!’ then pointing still farther to the left he said: ‘And the head of your regiment is at the fort.’ I soon found the flag, and called all of the Eleventh Missouri, within sound of my voice, to come forward to the colors. Only forty-four appeared. I exhorted the boys to follow me to the fort. The color sergeant refused to carry the flag. Just as I was about to reach for it, brave Corporal Warner stepped forward, grabbed the flag, and to the fort it went with us. It was raised, but soon shot down, only to be again put up and floated on the rebel fort until dark. Twenty-four of the forty-four got to the fort. After arriving there we could do nothing but sit with our backs to the wall until darkness came, when under cover of the night, we finally got out, and safely returned to camp.’ (3)

Brigadier-General Joseph A. Mower (Library of Congress)

On the 11th September 1897 Menomen O’Donnell received the Medal of Honor for his actions that day at Vicksburg. The first part of the citation read: ‘Voluntarily joined the color guard in the assault on the enemy’s works when he saw indications of wavering and caused the colors of his regiment to be planted on the parapet.’ However Vicksburg was not the sole reason for the award. It also recognised his actions at Fort DeRussey, Louisiana on 14th March 1864 when he: ‘Voluntarily placed himself in the ranks of an assaulting column (being then on staff duty) and rode with it into the enemy’s works, being the only mounted officer present; was twice wounded in battle.’ (4)

The reference to Fort DeRussey was testament to Menomen’s continued bravery and his close relationship with Brigadier-General Joseph Mower. Mower had been O’Donnell’s brigade commander at Vicksburg, and had approved the Irishman’s promotion to Captain following the fighting there. By 1864 Mower had risen to divisional command, and both men were taking part in the ill-fated Red River Campaign. Fort De Russey blocked the Federal advance, and Mower had been ordered to deal with it. Menomen takes up the story:

‘Returning from a reconnaissance, in which, with a few mounted orderlies, I had taken twenty prisoners, with some supply wagons, I found General Mower with the command, about two miles from the fort. The general said to me: ‘Captain, I have received orders to go into camp; what do you say?’ ‘General, it is not for me to say what to do,’ I answered. ‘I wish you would give me your opinion,’ he persisted. ‘General,’ I replied, ‘if I were in your place, I would capture Fort DeRussy before evening. if we don’t, the enemy will be gone before daylight.’ ‘Just my own opinion,’ General Mower said, requesting me to take a brigade, and open fire, which was the signal for a general charge. Subsequently I led the Twenty-fourth Missouri of Colonel Shaw’s Brigade against the enemy. There was some hard fighting, but at 6.30 pm we were in possession of the fort.’ (5)

In his report of the action, Mower did not forget O’Donnell: ‘I deem it my duty to mention the conduct of Captain O’Donnell, of my staff, who rendered me most efficient and valuable aid in putting troops into position. He was always ready when his services were required, and was one of the first in the enemy’s works.’ Aside from the actions which saw him receive the Medal of Honor, Menomen had a number of other brushes with death. He received three gun-shot wounds in the left arm during a skirmish with the Rebels at Grand Ecore, Louisiana on 5th April 1864 and had two horses shot from under him at Tupelo, Mississippi that July. The latter encounter resulted in a fall that crushed his left shoulder and aggravating his earlier wound. These injuries forced Menomen from the service, and he was mustered out at St. Louis, Missouri on 9th August 1864. (6)

Menomen O’Donnell and his family in later years (Deborah Maroney)

Following the war Menomen O’Donnell returned to business in Bridgeport. He sought to build on his family’s position through cattle ranching and by expansion into the pork packing trade. However, he had not reckoned on the Panic of 1873. This financial crisis and the depression that followed destroyed his business and took his fortune, which was estimated at some $70,000. Having built himself up from scratch and survived the hardships of war, Menomen now faced what was perhaps his toughest challenge. He had to find a way to restore his family’s livelihood and secure their economic future. He decided to move to Vincennes, Indiana in 1879, where he opened a butcher’s shop and slowly but surely began to recover financially. He rebuilt his family’s business and became active in the Grand Army of the Republic and also the local Democratic Party. Having successfully conquered his post-war setbacks, Menomen O’Donnell was able to enjoy his later years. He passed away at the age of 81 on 4th September 1911 at his home in Vincennes, Indiana and is buried in the city’s Mount Calvary Cemetery. (7)

*Special thanks are due to Deborah Maroney, a descendant of Menomen O’Donnell, for providing images and valuable information about her ancestor.

(1) Maroney: Capt. Menomen O’Donnell, Blanchard 1898: 1136; (2) Blanchard 1898: 1137, Belcher 2011: 42; (3) Belcher 2011: 124, Beyer & Keydell 1901: 200- 201; (4) Proft 2002: 954; (5) Beyer & Keydell 1901: 201; (6) Belcher 2011: 149, Blanchard 1898: 1138; (7) Vincennes Sun-Commercial 2011, Blanchard 1898: 1138-1139, Maroney: Capt. Menomen O’Donnell;

References & Further Reading

Belcher, Dennis W. 2011. The 11th Missouri Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster.

Beyer, Walter F. & Keydel, Oscar F. 1901. Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won The Medal of Honor, Volume 1.

Blanchard, Charles 1898. History of the Catholic Church in Indiana, Volume 2.

Maroney, Deborah, n.d. Capt. Menomen O’Donnell.

Proft, R.J. (ed.), 2002. United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations, Fourth Edition.

Vincennes Sun-Commercial 3rd June 2011. Menomen O’Donnell: O’Donnell ‘A Man of Courage’.

Vicksburg National Military Park

Civil War Trust Vicksburg Page

Civil War Trust Red River Campaign Page

Filed under: Battle of Vicksburg, Donegal, Medal of Honor, Missouri Tagged: 11th Missouri, County Donegal, Fort DeRussey, Irish American Civil War, Joseph Mower, Medal of Honor, Siege of Vicksburg, Vicksburg May 22nd

June 9, 2013

Upcoming Speaking Engagements

I have a number of speaking engagements coming up over the next few months, many of which relate to the theme of the Irish in the American Civil War. I have included details below, so if you find yourself nearby please consider popping along!

The History Festival of Ireland, Duckett’s Grove, Co. Carlow

Sunday 16th June

‘Ireland and the American Civil War: Selective Memory Loss’- Panel discussion with Ciaran O’Neill (Trinity College, Dublin), Catherine Clinton (Queen’s University, Belfast) and Úna Ní Bhroiméil (University of Limerick)

Bere Island, Co. Cork

Saturday 22nd June

‘The Nineteenth Century Defences of Bere Island, Co. Cork’

Colonel Charles O’Kelly Aughrim Military History Summer School, Co. Galway

Saturday 13th July

‘Battle of Knockdoe: History and Archaeology’- with Dr. John Cronin

Third Annual International Famine Conference, Strokestown Park House, Co. Roscommon

Saturday 20th July

‘Allow me to Mingle My Tears: The Impact of the American Civil War on Female Famine Survivors’

Cashel Summer Lecture Series, Cashel, Co. Tipperary

Tuesday 13th August

‘Tipperary and the American Civil War’

NRA Archaeology Seminar, Dublin

Thursday 22nd August

‘Revealing the Individual with Conflict Archaeology’

Tipperary Remembrance Trust, Tipperary, Co. Tipperary

Saturday 28th September

‘The Irish in the American Civil War’

Newcastle Historical Society, Co. Tipperary

Monday 4th November

‘Tipperary and the American Civil War’

Old Athlone Society, Co. Westmeath

Wednesday 13th November

‘The Midlands and the American Civil War’

Centre for Contemporary Irish History Seminar, Trinity College, Dublin

Wednesday 4th December

‘Forgetting Ireland’s Sites of Independence?’

University College Galway Archaeological Society, Galway

Tuesday 28th January

‘The Conflict Archaeology of Ireland’

Filed under: Update Tagged: Battle of Knockdoe, Conflict Archaeology, History Festival of Ireland, Ireland American Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Irish Archaeology, Irish Famine, Irish History

June 3, 2013

In Search of Michael Corcoran’s Ireland

Michael Corcoran emigrated to the United States in 1849, shortly before his 22nd birthday. In the fourteen years that remained to him he became one of Irish-America’s most popular and influential leaders. Rising to Colonel of the 69th New York State Militia he notoriously refused to parade the regiment on the occasion of the Prince of Wales’ visit to New York in 1860. With the advent of war he led the 69th at Bull Run and was captured there, becoming a hero of the Union for his involvement in ‘Enchantress Affair.’ Upon his release in 1862 he organised and led his own brigade, ‘Corcoran’s Irish Legion’, which he commanded until his death in December 1863. I took the opportunity on a recent visit to Sligo and Donegal to visit some of the sites associated with Corcoran.

The memorial to Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran in Ballymote, Co. Sligo. This is the closest village to Carrowkeel where Corcoran was born on 21st September 1827. The memorial was erected in 2006 and together with the Thomas Francis Meagher equestrian statue in Waterford is Ireland’s most impressive American Civil War related memorial.

Detail of the Corcoran Memorial in Ballymote, Co. Sligo.

Plaque commemorating the unveiling by Mayor Michael Bloomberg of the Corcoran Memorial, Ballymote, Co. Sligo.

Fragment of steel from the World Trade Center, New York to commemorate Firefighter Michael Lynch who died as a result of the 9/11 attack. Firefighter Lynch’s family are originally from Co. Sligo.

The crest of the 69th New York at the Corcoran Memorial, Ballymote, Co. Sligo.

Ballymote, Corcoran’s home village.

Creeslough, where Corcoran served in the Police

New York, where Corcoran emigrated

Bull Run, where Corcoran led the 69th NYSM

In 1846 Michael Corcoran joined the Revenue Police and was stationed in Creeslough, Co. Donegal. His three years in the force, pursuing locals for misdemeanours such as illicit alcohol production radicalised the young man. He joined the local Ribbonmen, a secret agrarian society that sought to strike back at Landlords and the administration that supported them. He fled Ireland when the Revenue Police grew suspicious regarding his activities. These buildings now occupy the site of the former Revenue Police Depot in Creeslough, Co. Donegal.

These nineteenth century buildings now occupy part of the former Revenue Police Depot in Creeslough, Co. Donegal where Michael Corcoran served. It is possible that part of the original depot is partly preserved in their walls.

More Nineteenth Century buildings on the former site of the Revenue Police Depot, Creeslough, Co. Donegal which may preserve part of the fabric of the original layout.

The Lackagh Bridge, near Creeslough, Co. Donegal. Although slightly altered since Corcoran’s day, the bridge and road would have been extremely familiar to the Sligo man. It lies on the only north-easterly route from Creeslough, a road which Michael Corcoran would have regularly travelled while carrying out his duties with the Revenue Police.

Doe Castle, near Creeslough, Co. Donegal. Michael Corcoran was undoubtedly extremely familiar with this Castle, and most likely visited it often. Given his later Fenian persuasion is it easy to see him being attracted to the former Stronghold of the Mac Suibhne na d’Tuath, where the famous Red Hugh O’Donnell once spent part of his childhood.

Filed under: 69th New York National Guard, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Donegal, Michael Corcoran, Sligo Tagged: 69th New York, Ballymote, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Creeslough, Irish American Civil War, Michael Corcoran, Revenue Police, Ribbonmen

May 26, 2013

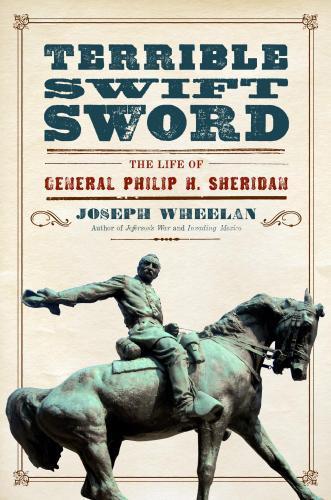

Book Review: Terrible Swift Sword- The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan

Terrible Swift Sword: The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan is widely regarded as one of the triumvirate of Union Generals (along with Grant and Sherman) who won the American Civil War. An often controversial individual, ‘Little Phil’ was a larger than life character who enjoyed a meteoric rise to high-command during the conflict. Joseph Wheelan’s new biography looks at the Irishman’s wartime-record but also explores beyond 1861-65 in an effort to examine Sheridan’s full contribution to American history.

One of the oft debated aspects of Phil Sheridan’s early life is where he was born. Sheridan himself claimed to have been born in Albany, New York, while others claim him for Killinkere in Co. Cavan or state that he came into the world on board the ship which carried the Sheridan family to the United States. We will almost certainly never know for sure his actual nativity, but in any event this is somewhat immaterial. What is of more interest is how Sheridan viewed himself, and in this regard he remains enigmatic. Although he was undoubtedly an extremely patriotic American, his interaction with his ‘Irishness’ is harder to discern- it is often referred to purely with regard to his fiery temperament. Shedding light on this aspect of Sheridan was not within the remit of this volume, but nonetheless Wheelan’s book does have an interesting story to tell about other aspects of his life.

Phil Sheridan is one of the archetypal ‘controversial’ Generals of the American Civil War. He subscribed to Grant and Shermans views on executing a form of total war, and his destruction of the Shenandoah Valley in 1864 became remembered locally as ‘The Burning.’ More recently historian Eric J. Wittenberg in his book Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan cogently questions his ability as a cavalry commander, his military record in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, his tendency towards disobeying orders and most convincingly his harsh treatment of men such as George Crook and Gouverneur Warren. In contrast to Wittenberg, Joseph Wheelan views Sheridan in a largely positive light and concentrates for the most part on the diminutive officer’s many undoubted talents, such as his exceptional capacity to motivate the forces under his command (illustrated to such legendary effect during ‘Sheridan’s Ride’ at the Battle of Cedar Creek).

Wheelan starts his book with a review of Sheridan’s early years in Ohio, his turbulent time at West Point and his first experience of army life in Texas, California and the Pacific North-West. The bulk of the book deals with the Civil War years and recounts Sheridan’s impressive displays at Stones River and Chattanooga, the latter catching Grant’s eye and catapulting Sheridan into the mix for high command in the eastern theater in 1864. Grant would remain Sheridan’s greatest admirer for years to come. Little Phil”s actions against Jeb Stuart’s cavalry, his command in the Shenandoah Valley and his extremely impressive performance leading up to Appomattox are also explored and are familiar territory for many interested in the Civil War.

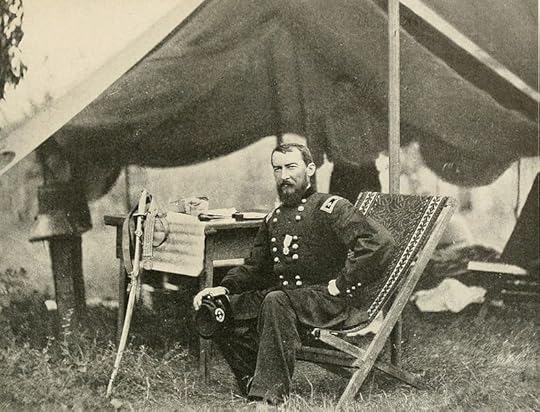

Phil Sheridan as Commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry in 1864 (Photographic History of the Civil War)

Wheelan is to be commended for dedicating significant space in the book to Sheridan’s post-war career. Some tough assignments came hot on the heels of the conflict for Little Phil. As commander of the Military District of the Southwest in 1865 he had to deal with the threat of the French military presence in Mexico, while as Military Governor of the Fifth Military District in Texas and Louisiana he oversaw Reconstruction and took a hard-line against those whom he perceived as obstructing it, a policy that brought him into direct confrontation with President Johnson.

The latter part of the 1860s saw Sheridan overseeing the ongoing Indian Wars where he replicated the ruthless efficiency he had displayed in the Shenandoah Valley to suppress the Native-Americans. In January 1869 during a meeting with Southern Plains chiefs, one introduced himself to Sheridan, stating ‘Me Toch-a-way. Me good Indian.’ The Irishman supposedly replied ‘The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.’ This has gone down in history as the infamous phrase ‘The only good Indian is a dead Indian.’

Sheridan would later observe the Franco-Prussian War and rise to Lieutenant-General of the Army of the United States. That he was more than just the brutally efficient soldier of the Shenandoah and Plains Wars can be seen in his exceptional efforts to have the Yellowstone region preserved in what amounted to a personal crusade. This extended to sending in troops to protect the Yellowstone Park; they continued to operate it until 1916.

Phil Sheridan’s personal life remains something we gain only glimpses of, such as his romance with a Native-American woman during his days in the Pacific Northwest and his marriage in 1875 to Irene Rucker. Much of the potential for a deeper insight into Sheridan the man was lost when his papers were lost during the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. As a result much of the accounts on which Wheelan draws are secondary, and the reader cannot help but be left with a desire for a deeper understanding of what made Sheridan tick. Despite this, Terrible Swift Sword is a useful overview of Phil Sheridan’s life, particularly in revealing what became of him in the decades after the conflict which made him famous.

References

Wheelan, Joseph 2012. Terrible Swift Sword: The Life of General Philip H. Sheridan. 387pp.

Wittenberg, Eric J. 2002. Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan

*I am grateful to Da Capo Press for providing a review copy of this book

Filed under: Book Review, Books, Cavan Tagged: Cavan, Irish American Civil War, Joseph Wheelan, Little Phil, Phil Sheridan, Sheridan's Ride, The Only Good Indian is a Dead Indian, Yellowstone National Park