Damian Shiels's Blog, page 51

September 1, 2013

‘After I Am Dead, Write to My Wife’: An Irish Soldier’s Last Moments Revealed

I have read the Widow’s Pension Files of many Irish families who were devastated by the American Civil War. The information contained in each reveals much about both the family behind the soldier and the long-term impact of the conflict on generations of Irish-Americans. However, when reading the application of Ann Scanlan, whose husband Patrick lost his life in the service of the Irish Brigade, I also came across the letter notifying her of her husband’s death. This remarkably emotive document related to Ann her husband’s last words to his family, and has to my knowledge not been read in 150 years. It is reproduced below for the first time.

Ann Leskey married 22-year-old Patrick Scanlan when both were in their early twenties, on 29th April 1851. At the time they were both living in Charleston, South Carolina. Her husband, an Irish laborer, must have been a striking individual- he stood at an above average 6 feet in height, had blue eyes, brown hair and a light complexion. Within a year the couple’s first child arrived- John, born on 26th March 1852. A daughter Catherine followed on 23rd February 1854, second son James on 7th November 1856. John and Catherine were baptised in St. Mary’s in Charleston while James was baptised at the Cathedral of Saint John and Saint Finbar in the city. Sometime after James’ birth the family decided to move to New York. A third son, Cornelius, was born there on 30th June 1860, but tragedy left its mark on the family when the baby died just a few months later on 17th January 1861. Within the year Patrick enlisted in what would become the 63rd New York Infantry, soon to be one of the famed regiments of the Irish Brigade. When he mustered in on 11th October 1861 Ann had recently become pregnant with their fifth child; Sarah Ann was born on 4th May 1862. Patrick would most likely not have seen his new daughter, as he was bound for the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia and the hard-fighting that was to be the Brigade’s lot throughout the summer of 1862. It appears he was wounded at Antietam that September, but recovered to be with his regiment for their next major battle, the ill-fated assault on Marye’s Heights, Fredericksburg on 13th December 1862. The big Irishman went into the engagement holding the rank of Corporal, a highly reliable and well-respected member of the regiment. (1)

Saint John and Saint Finbar Cathedral, Charleston after it was destroyed by fire in 1861. Patrick and Ann Scanlan’s son James was baptised here in 1856 (Library of Congress)

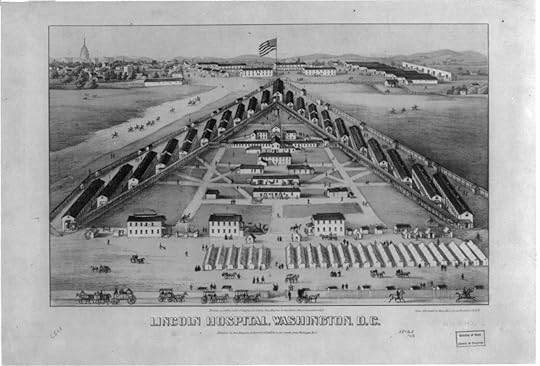

As the 63rd New York and the Irish Brigade advanced on 13th December, Patrick Scanlan’s luck ran out. A bullet struck him in the right knee, lodging in the joint. It appears that efforts may initially have been made to save his leg, but infection set in. Removed to Lincoln Hospital in Washington, D.C., he underwent surgery on 26th December- his right leg was removed at the thigh. The shock of the amputation must have been colossal. On 1st January 1863 Patrick’s wound haemorrhaged, weakening the already dangerously ill soldier. When his wound again haemorrhaged on 6th January he was operated on once more, in an attempt to try to stem the bleeding in his inner thigh, an area known as Scarpa’s triangle. The surgeon’s efforts ultimately proved in vain. Patrick Scanlan died in Ward 10 of Lincoln Hospital on the evening of 14th January 1863, a month after receiving what proved his fatal wound at Fredericksburg. Minutes after his death, a man called William Duffie sat down to write a letter to the newly widowed Ann. He informed her of her husband’s death, offered words of comfort, and communicated Patrick’s final words to his family. Ann later had to surrender the letter as proof of her relationship with Patrick; the fact that her marriage had taken place in what was now the Confederacy meant she did not have access to the records that would allow her to show the authorities her relationship with the Irish Brigade soldier. With four children to support, she was forced to give up what must have been a cherished document. It has rested in her Widow’s Pension File for 150 years, and is here transcribed for the first time (2):

Ward 10

Lincoln Hospital Washington D.C.

Jan. 14th 1863

Mrs. Ann Scanlan,

Dear Madam- its become my very painful duty to inform you that your husband has just breathed his last. He died at 25 minutes to seven o’clock this evening without pain. As quietly as the infant sinks to rest from the bosom of its mother so peacefully did he breathe out his last sigh and resign his spirit into the hands of the God who gave it. I know how great will be your grief upon reception of this sad news but it is the will of God that it should be so and you must try and bear the bereavement with resignation, knowing that is not for you to question His right to do with His own as He sees fit: “The Lord gave and the Lord taketh away: blessed be the name of the Lord!” Every heart knoweth its own sorrow; and there is a grief which cannot be expressed in word, God alone has power to comfort you and to bind up your wounded and bleeding heart, in this your season of great distress; turn then to Heaven and may He who is the refuge of the weary- the hope of the sorrowing of earth, be with you and sustain you in this hour of trial and throw the arms of His everlasting salvation around you! Mr. Scanlan received the last rights of his religion this morning- the Sister, who has charge of this ward, has been constant in her attendance upon your husband and has done all in her power to alleviate his sufferings. I am not myself a Catholic and do not therefore understand the peculiarities of that faith, but Sister told me that the Priest had administered all the last rites necessary in such cases provided. The Priest has seen him several times and was present last Sunday morning and the Sacrament was I believe administered. It will be a great satisfaction to you to know that it is, as it is in this respect I have thought of the difference between the case of your husband and of another poor fellow who died recently and belonging to a different faith. He passed away without so much as having a Minister of Religion near him to breathe a prayer for the peace of his departing soul – such is the difference between the two religions. It has set me to thinking and I shall do so seriously I assure after this. Your last letter was received, and I offered to write an answer knowing that you would naturally feel anxious to hear from him, but he said he’d wait a day or two first to see if there would be any change for the better. He felt sensible, I think, that his end was approaching for he requested me to make a note of his feelings at that time- this was yesterday forenoon, I think. He did not talk a great deal as it hurt him to do so much. “After I am dead, write to my wife and tell her that I died a natural death in bed, having received the full benefits of my church.” “Say that I felt resigned to the will of God and that I am sorry I could not see her and the children once more. That I would have felt better in such a case before I died. It is the will of God that it should not be so, and I must be content to do without.” This was about the substance of what he said. I read it to him and he said it was all that would be necessary to write. His pay amounts to some 6 1/2 months not having received any since the 1st of July. This of course you are entitled to draw and you can do so by getting some friend to assist you, understands about it. The few things in this letter are all his personal effects. The rest of his things letters & c. he said to burn- which will be done. I will close for the present.

I remain very truly your well wishes, William Duffie. If you wish to answer this, please direct to me Lincoln Hospital, Washington, D.C., Ward 10. (3)

The first page of William Duffie’s Letter to Ann Scanlan, informing her of her husband Patrick’s death (Fold3)

Ann would receive a pension for the service of her husband, and was also given aid for each of her surviving children until they reached the age of sixteen. Neither did Patrick’s comrades in the 63rd New York forget her. In a remarkable gesture the surviving men of the regiment held a collection to assist the widow and children of a man they had clearly been close to. Unusually the charitable effort was recorded in the New York Irish-American, along with the names of the men who gathered together a total of $100 for Ann and her children. Unfortunately her tribulations were not over. As so often seems to be the case, the spectre of death once again visited her family in 1863. On 6th August 1863 her youngest child Sarah Ann died, barely over a year old. It is unclear if the little girl had ever seen her father. One can only imagine the renewed anguish that this loss brought to Ann and her family. (4)

Lincoln Hospital as it appeared during the American Civil War. Corporal Patrick Scanlan died here, and William Duffie wrote from Ward 10 to inform Ann Scanlan of his last words (Library of Congress)

The charitable collection for Patrick Scanlan as recorded in the Irish-American is reproduced below, as is the ultimate fate of each of the men who contributed (recorded in parentheses after their donation):

GENEROSITY OF THE IRISH BRIGADE

New York, May 5th, 1863

To the Editors of the Irish-American: Your journal has often chronicled the deeds of the Irish Brigade on the battlefield. The fame of their daring and valor was spread and resounded over the whole extent of this continent, and even their very enemies have wafted it across the Atlantic and reechoed it throughout Europe. And what wonder? They have rendered every battle-field, where they have fought, memorable for some bold, unexpected, astonishing deed, won renown amidst disaster, and left the enemy, where they at least, happened to be, little cause for triumph or exultation. These things have often thrilled us through, and made us involuntarily speak a blessing and a prayer for the proud little cohort which shed such lustre on our race and land, and proved that the story of the prowess was no fiction. Such things as these excite our admiration and our pride. But the men of the Brigade do other things, which affect us to tears; they can prove themselves as kind-hearted and generous as they are brave. Standing again in the front, diminished in numbers, but not dismayed, and ready to interpose their bodies again between their country (for they have no other now) and the deadly thrusts of its destroyers, they rise above the tumult, the passion and horrors of war, and give way to the better impulses of their nature, the higher and nobler feelings of the heart. When at last, they receive their long looked for and much needed pay, their own wants alone are not uppermost in their minds; the memory of a dead comrade, and of his heroic deeds, comes back upon them, and they think of his widowed wife and orphan children. For them to conceive the generous deed, is to perform it, and as a proof of this, I enclose a note and a list of the names of the brave officers and men of the company of the deceased soldier, who contributed, it having accompanied the money remitted by Captain Condon, now commanding the 63d Regiment in front of the enemy. I know not whether I am doing exactly right in sending you the note and list of contributors for publication; but the amount sent (one hundred dollars) is so liberal, so generous, for so small a number of men, most of whom receive but a very small pittance in the way of pay, that I cannot help thinking that giving a place in your paper to so signal an act of generosity is as much due to the brave soldiers of the Brigade themselves, as it will be pleasing to your many readers to know about it. Patrick Barry [transferred to 24th Veteran Reserve Corps in 1864], another brave and generous soldier of Company A, 63d N.Y.V., sends to the “Limerick Fund” a contribution of two dollars, which I enclose, hoping you will be pleased to apply it, as you may deem fit, in accordance with the wish of the kind contributor.

Very respectfully yours, P.J.O. [Patrick J. O'Connor, First Lieutenant, Company E, discharged 28th May 1863]

ON PICKET NEAR SCOTT’S FORD, VA., April 2d, 1863

My Dear O.

You will please hand over the enclosed one hundred dollars to Mrs. Scanlan, widow of the late Patrick Scanlan, of my Company, who died from the effects of wounds received at the late battle of Fredericksburg. The generosity here displayed by the few remaining comrades of the gallant corporal towards his widow and orphans shows the estimation in which he was held by them, as also their own goodness of heart. He was beloved by all for his manliness and bravery. The officers whose names are attached were so well pleased with the action of the men in the affair that they have subscribed the sums set opposite to their names. In handing to Mrs. Scanlan the enclosed, please mention the honest and heartfelt expression of sympathy by the comrades of her husband in her bereavement.

I am, my dear O, very truly yours, P.J. Condon, Capt. [Captain Patrick J. Condon, Company G, mustered out 12th June 1863]

Sergeant Ed. Lynch, $5.00 [Mustered out with regiment, 30th June 1865]

Sergeant P.H. Vandewier $1.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Sergeant Wm. Hayden $5.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863, later service Company I, 2nd Artillery]

Corporal James Cline $1.00 [Mustered out with regiment, 30th June 1865]

Corporal John Tinsley $1.00 [POW Chancellorsville, Mustered out 17th September 1864]

Corporal Hugh Hamilton $1.00 [Deserted on expiration of veteran furlough, January 1864]

Corporal Sam. Walsh $1.00 [Deserted on expiration of veteran furlough, January 1864]

Private Peter O’Neil $1.00 [Wounded at Spotsylvania, 18th May 1864, absent wounded at muster out in 1865]

Private James Smith $1.00 [Deserted 29th June 1863, Frederick, Maryland]

Private Charles Hogan $5.00 [Killed in Action, 2nd July 1863, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania]

Private Michaely Byrns $1.00 [Died of Disease, 20th February 1864, Douglas Hospital, Washington D.C.]

Private Patrick Power $1.00 [Deserted on expiration of veteran furlough, January 1864]

Private James Riely $5.00 [Wounded Antietam, Maryland; Killed in Action 5th May 1864, Wilderness, Virginia]

Private Patrick Collins $5.00 [Mustered out with regiment 30th June 1865]

Private James Crowe $2.00 [Wounded Antietam, Maryland; Transferred to Veteran Reserve Corps 23rd February 1864]

Private Richd. Hourigan $1.00 [Wounded Antietam, Maryland; Mustered out 16th September 1864, Petersburg, Virginia]

Private P. Pendergast $1.00 [No record after 10th April 1863]

Private John McCarthy $1.00 [Mustered out with regiment 30th June 1865]

Private Patrick Harkin $1.00 [Mustered out 22nd September 1864, New York City]

Private Patrick Lucy $1.00 [Mustered out with regiment 30th June 1865]

Private Anthony Campbell $1.00 [Deserted on expiration of veteran furlough, January 1864]

Private P.J. Lynch $2.00 [Discharged for Disability 9th February 1863?]

Hospital Steward John J. Corridon $1.00 [Mustered out with regiment, 30th June 1865]

Private James Guiney Company F $1.00

Dr. Lawrence Reynolds 63rd N.Y.V. $5.00 [Mustered out with regiment, 30th June 1865]

Dr. Smart $5.00 [Discharged 29th March 1864 to become Assistant Surgeon in U.S. Army]

Major Geo. A. Fairlamb 148th P.V. $5.00

Mr. Coleman, Sutler 63rd N.Y.V. $5.00

Captain Dwyer $5.00 [Wounded Antietam, Maryland; Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Captain Quirk $5.00 [Wounded Fredericksburg, Virginia; Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Lieutenant Ryan $1.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Lieutenant Gallagher $3.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Lieutenant Maher $2.00 [Mustered out as Captain, Company D, 30th June 1865]

Lieutenant Murray $5.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Captain Condon $12.00 [Mustered out 12th June 1863]

Total $100.00. (5)

Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C. This is the former site of Lincoln Hospital, where Corporal Patrick Scanlan died in January 1863 and where William Duffie wrote to his wife Ann (Wikipedia)

(1) Widow’s Pension File, New York AAG Report; (2) Medical and Surgical History: 797, Widow’s Pension File; (3) Widow’s Pension File; (4) Widow’s Pension File, New York Irish-American; (5) New York Irish-American;

References & Further Reading

Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901.

Patrick Scanlan Widow’s Pension File WC83473.

New York Irish-American 23rd May 1863. Generosity of the Irish Brigade.

U.S. Army Surgeon General’s Office 1883. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Part 3, Volume 2 (3rd Surgical Volume).

Civil War Trust Battle of Fredericksburg Page

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Fredericksburg, Irish Brigade Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Civil War Amputation, Irish American Civil War, Irish Americans in New York, Irish Brigade at Fredericksburg, Irish Brigade Casualties, Irish widow's Pension File, Lincoln Hospital

August 26, 2013

‘Any Information Will Be Most Thankfully Received by His Mother’: Tracing Missing Irishmen in 1860s New York

Every week in the New York Irish-American a series of advertisements were run under the heading ‘Information Wanted.’ For $1 you could place a few carefully chosen lines in three issues of the paper, in the hope of finding a loved one. I find these ads some of the most emotive and powerful records of the impact of conflict. In an age before mass media and the internet, many friends and families searched fruitlessly for years in an effort to restore contact with cousins, sons and brothers. Some were successful; others received the bad news they had been dreading. Having previously explored this topic with the tragic story of Alexander Scarff and others, I wanted to take another look at this unique record of the impact of war on the Irish diaspora.

INFORMATION WANTED Of Patrick Bush, a native of Bennett’s Bridge, County Kilkenny, Ireland. When last heard from, two years ago, he was in Southwick, State of Massachusetts. There was an account of a man of the same name in the Irish-American of June 22, 1861, being killed at Bull’s Run, who belonged to a regiment of the New York State Militia, Co. E. If Lieut. Dempsey, of the 2d, knows anything about him he will confer a great favor by writing to Jeremiah Bush, Sommers Post-Office, Tolland County, State of Connecticut. (New York Irish-American, 7th June 1862)

It is unclear if Jeremiah ever established if this was his brother, but the balance of evidence suggests it was. Patrick Bush had enlisted in the 2nd New York State Militia on 20th May 1861 at the age of 25; two months later he was dead. He was killed in action on 21st July 1861 in the first major battle of the war. Clinton Berry of the 2nd N.Y.S.M. remembered Patrick being ‘struck by a shot from the enemy and afterwards I saw the body…lying dead upon the roadside.’ Patrick’s father (also a Jeremiah) had died on 20th January 1860, leaving his mother Johanna in need of support. She received a pension for her son’s sacrifice.

INFORMATION WANTED Of John, Timothy, Denis, James and Martin Driscoll, natives of Courtmacsherry, County Cork, Ireland, who arrived in America about 34 years ago. Any information of them will be thankfully received by their nephew, Daniel McCarthy, Co. H, 170th Regiment N.Y.V., Corcoran’s Irish Legion, Newport News, Va. (New York Irish-American, 13th December 1862)

31-year-old Daniel McCarthy had enlisted in the 170th New York on 15th September 1862. He was promoted to Corporal in 1863 but was returned to the ranks before April 1864, presumably for a misedemanour. He was captured at the Battle of Ream’s Station, Virginia on 25th August 1864 but survived to be paroled. He died on 26th December 1893.

INFORMATION WANTED Of John Callaghan, a native of Kilrush, Co. Clare, Ireland. He was a member of Co. G, 88th Regiment, Meagher’s Irish Brigade. Was taken prisoner at the Battle of Fredericksburg, and has not been heard of since. Any intelligence respecting him will be thankfully received by his brother, Patrick Callaghan, 602 Sixth Avenue, New York. (New York Irish-American, 29th August 1863)

John Callaghan had enlisted in the 88th New York on 25th August 1862 and appears to have been captured at Chancellorsville rather than Fredericksburg. he was paroled on 3rd June 1863 and would eventually rise to the rank of First Sergeant in Company E before mustering out at the war’s conclusion.

An Example of the ‘Information Wanted’ Section in the New York Irish-American. This issue from 14th October 1865 includes the ad placed by John Granfield’s Mother. (Genealogy-Bank)

INFORMATION WANTED Of Anthony O’Hara, who left the parish of Backs, County Mayo, two years ago, and came to the United States. When last heard from, he was in the United States Army, Battery G, 5th Artillery, Fort Hamilton, New York Harbor. Any information of his whereabouts will be thankfully received by his brother, Michl. O’Hara, Meadville, Crawford County, Pa. (New York Irish-American, 29th August 1863)

Anthony was alive and well at the time his brother was searching for him. He had enlisted in the 5th U.S. Artillery as a 22-year-old on 29th October 1862 and served with them until his term of service expired on 22nd August 1865. He was described as a 5 foot 6 inch laborer with hazel eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion.

INFORMATION WANTED Of Owen Fox, a native of the parish of Ballintemple, County Cavan, Ireland. He was a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians of New York, and is said to have driven a brick-cart for Patrick Lynch, the contractor. Any intelligence of him will be thankfully received by his first cousin, Patrick G. Brady, 69th Regiment, N.Y. Artillery, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, Fairfax, Alexandria P.O., Va. (New York Irish-American, 9th January 1864)

Patrick George Brady, who had submitted this query, was serving as a Private in Company K of the 182nd New York Infantry (69th New York National Guard Artillery). he had enlisted as a 39-year-old on 23rd September 1862. Unfortunately it is unlikely he ever managed to contact Owen, as Patrick was killed in action at the North Anna River on 24th May 1864.

INFORMATION WANTED Of Mary Anne Doran, daughter of Patrick Doran (or Dolan) 91st Regiment, N.Y.S.V., lately deceased. When last heard of supposed to be living with her grandparents in Eighth Avenue, New York. Any information of her will be thankfully received at 84 Wooster Street, New York, where she will hear of something to her advantage. (New York Irish-American, 3rd September 1864)

Patrick Doran had enlisted in Company K of the 91st New York from Albany on 6th November 1861 (under the name Dolan). He re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer on 1st January 1864 but died later that year of disease in Albany.

INFORMATION WANTED Of Mr. John Mulhall, who emigrated to American about three years since. When last heard of (about fifteen months ago) was Lieutenant in the 69th New York Regiment. Any information of him will be thankfully received by addressing Mr. Hugh O’Donnell, 87 North King Street, Dublin, or The Irish-American, 29 Ann Street, New York. (New York Irish-American, 19th November 1864)

John Dillon Mulhall had enrolled in the 69th New York as a First Lieutenant in Company H of the 69th on 11th February 1863. He transferred to Company B that June. He was most likely not in good health around the time of this appeal for information, as he was discharged for disability on 8th November 1864. He again mustered into the regiment on 16th February 1865, this time as Captain of Company D with whom he was wounded on 25th March that year. He was discharged on 15th May 1865 in Washington, D.C. He would live a long post-war life, claiming a pension for his service up to his death on 7th July 1903.

INFORMATION WANTED Of John Hoey, formerly of Montreal, Canada. He was last heard from June, 1863 when in the 18th Regiment N.Y.V. Information of him will be most thankfully received by his brother, James Hoey, Customs, Quebec, Canada. (New York Irish-American, 30th September 1865)

18-year-old John Hoey had enlisted in the 18th New York on 19th April 1861 as a Private, and mustered out with Company F on 28th May 1863. His fate following this date is unknown.

INFORMATION WANTED Of John Granfield, formerly a member of Co. C, (Capt. Lynch) 63d Regt. N.Y. Vols. He was captured before Richmond on the 14th day of October 1863, and when last heard from (February 14th, 1864) was confined at Belle Island as a prisoner. Any information respecting him will be most thankfully received by his mother. Address, William Downes, Attorney at Law, New Haven, Conn. (New York Irish-American, 14th October 1865)

John Granfield had enlisted as a 24-year-old in Company C of the 63rd New York on 21st August 1861. He had been captured while serving in Company B, at the Battle of Bristoe Station. He is recorded as dying of disease on 3rd March 1864 in Augusta, Georgia. His mother Mary, a widow from Co. Kerry, eventually discovered her son’s fate and was able to apply for a pension on 18th April 1866, over two years after his death. It would help to support her for a further 24 years.

References

New York Irish-American

New York Regimental Rosters

Union Pension Index Cards and Muster Rolls

Union Widow’s Pension Files

Filed under: Irish in the American Civil War Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Battle of Bristoe Station, Classified Ads Civil War, Information Wanted Irish, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Bull Run, New York Irish, New York Irish-American

August 23, 2013

Irish in the American Civil War on Tour

Despite writing this blog for a number of years now, it may surprise some readers to know that I have never had the opportunity to visit any of the American Civil War battlefields. Fortunately (and after a few false starts) I am finally in a position to rectify this, and hopefully catch some sesquicentennial events as well. I will be travelling to Washington D.C. in early May, and hope to be on the Wilderness battlefield for 5th May and Spotsylvania on the 12th. I intend to visit a number of other Civil War battlefields and take in some of the sights around Virginia and the capital. If any readers have suggestions as to what I should add to my itinerary I would love to hear from you!

Filed under: Events, General Tagged: American Airlines, American Civil War Tour, Battle of Spotsylvania, Battle of the Wilderness, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Virginia, Irish in Washington, Sesquicentennial 2014

August 18, 2013

War’s Cruel Hand: The Dedicated Service of Edward Carroll, Irish Brigade

Occasionally one has to look no further than a soldier’s service record to see both the poignancy and cruelty of war. Such is the case with Edward B. Carroll of the 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade. As I carry out work on the 63rd and other ‘green flag’ New York regiments, even a few matter-of-fact lines in the regimental roster cannot but highlight Carroll’s extraordinary service.

A native of Co. Tipperary, Edward B. Carroll enrolled in the 63rd New York as a fresh-faced 21-year-old in Albany, mustering in as a Corporal in Company K on 8th October 1861. He clearly showed his value during the hard fighting of 1862, as he began an inexorable rise through the ranks. He became a Sergeant on 4th August 1862, then a First Sergeant on 17th September 1862 (the same day as the 63rd endured the great bloodbath of Antietam). On 28th January 1863 he became Sergeant-Major, and made the jump to officer when he became a Second-Lieutenant in Company B on 7th April 1863. Then, despite the fact that Edward was clearly a highly-valued soldier, he was mustered out of the 63rd New York and the army on 12th June 1863. This was most likely caused by the consolidation of the regiment, which meant that less officers were required. It was a symptom of the ever-shrinking size of the Irish Brigade. Having survived some of the toughest fighting of the war, Edward would have been forgiven for sitting out the rest of the conflict- but clearly this was not the Tipperary native’s style. (1)

The Pension Index Card of Captain Edward B. Carroll, 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade (Fold3.com)

After the passage of a few months, presumably spent back in Albany, Edward Carroll returned to both the army and the 63rd New York Infantry on 23rd February 1864. Having lost his commission he was back to square one, enlisting as a Private in Company F. It would appear that his feelings for his regiment and his comrades trumped all else for Edward. However, his quality was clearly recognised by all, and once again he began to rise through the ranks. He became First Sergeant on 26th April 1864, a Second-Lieutenant in Company E on 15th September 1864, First-Lieutenant on 22 November 1864 and finally Captain on 13th January 1865. When reading through such an exceptional record of service you can’t help but admire this young man’s dedication to the 63rd, the Irish Brigade and the Union. Unfortunately his long and faithful service was not rewarded with a long life in peacetime as it might have been. The cruelty of war is indiscriminate. Captain Edward Carroll was killed in action at Sutherland Station, Virginia on 2nd April 1865, during the final days of the war in the east. Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia a week later, on 9th April. A cursory look at Carroll’s pension index card shows that he had not married, but that his parents had relied on him for their financial support. Even in regimental rosters, the heartbreak of the American Civil War is often on full display. (2)

(1) AG Report 1901: 20, Conyngham 1867: 572; (2) AG Report 1901:20, Edward B. Carroll Pension Index Card;

References

Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901.

Conyngham, David Power 1867. The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns.

Edward B. Carroll Pension Index Card.

Filed under: 63rd New York, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Battle of Sutherland Station, Civil War Widow's Pension, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Irish Brigade Antietam, New York Irish Regiments, New York Regimental Roster

August 15, 2013

Boston Immigrant to Crescent City Soldier: The Poignant Letters of William Hickey

I was recently contacted by historian Ed O’Riordan, who a number of years ago saved a remarkable series of letters sent home to Tipperary by an Irish emigrant in America, William Hickey. The letters chart the story of a young man who experienced the loneliness and uncertainty of life in a new country and his search for a place to settle down. That journey seemed fulfilled eight-years after his arrival, when William arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana. It would ultimately draw to a close near a small Tennessee Church, at a place called Shiloh.

In 1853 sixteen-year-old William Hickey left his home in Lisfuncheon, Clogheen, Co. Tipperary for the last time. Travelling first to Liverpool, he boarded a vessel (most probably the Vanguara) which brought him to New York that September. It was at Yarmouth Port in Massachusetts that he wrote his first letter home, on 3rd October:

Dear Father and Mother,

I take the opportunity in writing to you these few lines, hoping to find ye all in good health as this leaves me at present thanks be to God for it. Dear Mother I landed in New York on the 19 September, and since the day I left Liverpool I did not get one hours sickness…Dear brother keep your hilt [health] but I am not sorry for coming and I will have better news to send you in my next letter. (1)

However, despite William’s optimism it seems he struggled in his early days in the United States. He wrote home again from Boston in January of 1854, in a letter which suggests he was having trouble getting work and wanted to return home to Ireland. It also highlights how important it was for emigrants from a particular locality in Ireland to maintain contact in the United States after they arrived:

Dear Father and Mother,

I have to inform you that I received your kind note on the 20th which gave me the greatest pleasure in reading it. and also grieved me very much in your disappointment to me and if you had to send that money in your last letter I would be ready to sail on the 25[th] of this month to old Ireland once more. I have lost in some measure my time and credit, thereby yet my future diligence, I hope to recover both and to convince you that I will pay a strict regard to all your commands which I am bound to do. Dear Father and Mother I submit and give in that I was wrong in my down [doing] so to put you to that trouble but I hope it’s all for the better…This is the only season of the year to go home to Ireland. I can get a passage here in Boston for 12 dollars, when you can’t get in Liverpool for 20 dollars, and as quick as I receive your next letter I will write home the day before sailing, and when I get to Liverpool I will write likewise to you…Dear Father I am in Boston since September, boarding with Michael Keating with the exception of a few weeks. I met with [a] little accidence [accident]. I was to work on board the ship and got my two toes jammed and one almost cut off, but thanks be to god it’s all well now. You must excuse Michael Keating for not sending home some relief to his mother at present, in regard of the summer being bad and winter being likewise, and everything so dear, and he could not afford to send her some relief at present, but still he is not forgetting her, and he is still in the idea of sending for Wm. Keating his brother, and he was much pleased in hearing from all the family. Mick did not hear from Thos. for the last six months, in good health. (2)

One of William Hickey’s letters home to Tipperary (Ed O’Riordan)

Despite this correspondence, William did not return to Lisfuncheon. Instead over the next few months he decided that his future lay out west, in California. In his next letter of June 1854 he related his desire to move on, and also told of the successful arrival of more familiar Tipperary locals in Boston. He also revealed a heart-breaking story of one Irish family’s loss on their passage to America:

My dear Father,

I have to inform you that I am in perfect good health as I hope this will find you and my ever dear Mother, brother Thomas, James and my sister Bridget also. My dear father I am not being possess[ed] of as much as take me to go to California which place I am inclined to go with many others which are determined for the same Country where there is the greatest encouragement for young men if I had as much money as would pay my expenses. Dear Father it would take 8 weeks to take me there which would cost me 20 pounds which would take a long time to earn it here, everything is so dear and all commodities high through means of the Eastern War [Crimean War]. My dear Father and Mother I am much inclined for it. If you would take me into your kind consideration and remit as much money as would take me there. Therefore I will say no more on the subject but leave all to yourselves. So if you comply with my request I will kindly receive it with many thanks, Etc.

My dear Father and Mother I met with Wm. Starkey & family on board the Ship, Meridian at their arrival in Boston immediately at the dock in good health, after a voyage of 29 days without an hours sickness during the voyage. [62 year-old William Starkey had arrived on May 31st 1854 from Liverpool together with Alice (43) and children Richard (11), Peter (7) and Alice (9)]. At same time they have delivered the parcel you sent by them to me. You would not believe how well Wm. Starkey looks after his travels which I am happy to have to inform of. The same evening he arrived he was not two hours here when a Captain of another ship came into John Kelly’s where he stopped ordered on board for Chatham [Chatham, Massachusetts], at which time he and family started without taking the least nourishment but some gin and wine we took with Sister Norry, who kindly treated us. He then went on board and was driven back into Boston on the next morning…

…Dear Father we had Tom Russell with Wm. Starkey on board the same ship in good health. Not a single person died on board but one woman who was wife to John Bourke from Tubrid who went to bed with her husband the first night we went on board in Liverpool and was corpse the next morning at 4 o’clock, and left two young children to deplore her loss. He got only two hours to get her away on his back and have her interred. We lost no other person during the whole voyage. [William is here most likely referring to 30-year-old Michael Bourke, who sailed on the Meridian with Mary (9) and Oliver (1)]. We lost no other person during the whole voyage. Wm. Starkey had the title of being Mayor of the ship. My dear Father and Mother I have spent 6 months at the boot and shoe-making, which business is now rather dull here. I have brought Wm. Starkey to Aunt Norry, and Mickey Keatings and received him most kindly.

Dear Father, California is the West Country. Wm. Starkey says that I am much taller and stouter than my brother Thos. he joined me in love to you all, my mother, Thos., James and sister Bridget, and other inquiring friends, with many ardent wishes of your future prosperity. From your affection son etc.,

Wm. Hickey. (3)

William was clearly not sure what he really wanted to do. He had initially expressed a desire to return to Ireland, then changed his mind and set his sights on California. In the end he did neither. His next letter was dated 8th October 1854 when he was working at ‘Sheepscut Bridge’, most likely Sheepscot Bridge in Maine. Clearly lonely and missing Irish company, his attention was turning to a new potential destination- St. Louis, Missouri:

Dear Father and Mother, Brothers and Sister,

I take the opportunity in writing these few lines to you hoping to find you all in good health, as this leaves me, thanks be to God for it. Dear Mother and Father I have to inform you that I am here in this wilde country alone 200 miles from all friends in America. I was sure that any part I go to, but I would meet Irish, but here where I am now, there is none, but I could do no better and I should come here. I am in the wilde woods of America away from priests and chapel, and if I had as much money as would fetch me to St. Louis, I should have gone there before now, for I am sure it was there that the Ryans would get me a trade. I beg and request of you dear father and mother to send me the sum of six pounds, to as much as that would fetch me to St. Louis, and that’s all that ever I will ask of you, ’till I return you three times the compliment. I never had that cause to make money in this country, only as much as would keep me in clothing. I shed three tears from my eyes in this letter for you, thinking of you and being so lonesome here that I have no one that I would spare a word to but savage Yankees; some of them who [would] sooner see the divel than a Irishman. Michael Keating and his wife is in good health, and Aunt Norry and family likewise…

…Please go to Michael Ryan and he will leave you have the directions of his brother in St. Louis, and send it to me in your next letter. If I get a letter from you I will be in St. Louis before Christmas day, and I will have as much thin [then] as will buy me some clothes, and I can go there respectable. I am here working like a horse from four in the morning till ten at night before I can go to bed, and if I don’t get some supply from you dear Father and Mother, I will be perished going in the woods in the winter time cutting down wood, where there would be six foot of snow; in places fourteen foot of snow. (4)

William presumably received the money he requested from his father and moved to Missouri. However it seems he may have long harboured a desire to return to Ireland. His aunt Ellen Tobin indicated this in a letter to her brother and William’s uncle in Lisfuncheon, Father James Hickey, as late as 1859. Writing from Ware in Massachusetts she asks ‘if William Hickey went home yet.’ William did move on from Missouri but it was not to return home. A letter from March 1861 finds him in New Orleans, Louisiana:

Ever honoured Father and mother, brother and sister. I prefer addressing you these few lines not only to let you know that I am in health, but to present my humble duties and good wishes towards you. Ever wishing you an abundance of felicity and health, wealth and many prosperous days with the like duty and respect and the same good wishes to those that are near and dear to you. Inform you that I am employed in a very respectable Establishment. It is a new shoe factory. I get two dollars per day and very easy clean work. I enjoy the best of health and hope you do the same. You may rest assured that you are all fresh in my memory although not writing to you this many a day, for which I hope you will excuse me. I am sorry to hear of the death of my Venerable Uncle. I was told he died by a young girl of the O’Briens from Shandrahan. May God have mercy on his soul, amen.

Please write at the receipt of this, and let me know how is every member of the family, and all enquiring friends. Direct your letter to William Hickey, New Orleans, Louisiana. (6)

William Hickey’s Service Record with the 1st Louisiana Infantry (Fold3.com)

By the time William had written his letter Louisiana had already seceded from the Union. With the firing on Fort Sumter on 12th April 1861 and the outbreak of war, the Tipperary man decided to enlist. On 15th April the then 24-year-old joined up, mustering in to Company G of the 1st Louisiana Infantry Regiment (Strawbridge’s) on the 30th April. He clearly had leadership qualities, as he quickly became a Sergeant. William originally signed up to serve for one year. The beginning of 1862 found him and his regiment serving at Pensacola, Florida. It was here that William agreed to extend his time in the army to two years, making him eligible for a bounty of $50 that was to be paid on 15th April 1862. The early months of 1862 saw a major buildup of Union and Confederate forces in and around Tennessee, and the 1st Louisiana soon found themselves on the move to link up with the main army in the Western Theater. On 6th April 1862 the young man from Lisfuncheon and the Confederate Army of Mississippi advanced to the attack near Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee. The carnage that ensued across the 6th and 7th April was on a scale never before seen in American history. It became known as the Battle of Shiloh. (7)

The 1st Louisiana and the Confederate army had started their advance early on the morning of the 6th April. William and his comrades struggled forward through difficult wooded terrain and across a stream before they could move up a slight slope towards the first enemy line. They encountered their first taste of major battle at 8.30am, near the Union camps of General Prentiss. As they advanced to within 200 yards of the enemy the Louisianans took heavy fire from the Yankee line, which was supported by artillery and sharpshooters firing from the trees. As the engagement intensified the Rebel brigade commander, Brigadier-General Adley Gladden, was mortally wounded when a cannonball mangled his left arm and shoulder. With the men wavering, Colonel Daniel Adams of the 1st Louisiana (now acting as brigade commander) grasped the flag of his regiment and called on the men to follow him. They did. William and his fellow Rebels charged forward, driving the Union line back through their camp. The Lisfuncheon man had made it through the first encounter of the day. (8)

Despite their early success, there was a long day ahead for the 1st Louisiana Infantry. They eventually reformed on the other side of the captured Union camp, and had to endure artillery fire from nearby guns which were eventually silenced by Confederate fire. Eventually they were ordered forward once more, with the brigade soon losing another commander- Colonel Adams was wounded in the head by a bullet at around 2.30pm. As they drove forward to attack the next organised group of Federals, sometime around 4pm, Sergeant William Hickey was struck in the head and killed. He was one of 232 casualties sustained by the 1st Louisiana over the two days fighting at Shiloh. The young man’s fate was outlined in an 1866 letter written by David Ryan of St. Louis (the same Ryan cousins William had sought out in 1854) to his cousin and William’s uncle, Father James Hickey:

Your nephew William Hickey was a brave-hearted young man, well liked by everyone in St. Louis, and at the breaking out of the war he went to New Orleans where he joined the Confederate Army and was killed at the Battle of Shiloh holding the rank of Lieutenant [it is possible William was acting as a Lieutenant at the time of his death] and was acknowledged to be a brave intrepid commander. (9)

The man who had left home at the age of sixteen to travel to the United States had come to grief on a Tennessee battlefield at the age of only 25. His letters chart the story of a young boy in search of a better life- a boy who clearly had itchy feet, always looking towards the next place to live, the next opportunity. His journeying around America eventually took him to New Orleans, and ultimately the Confederate army. One can imagine the impact news of his death had at home in Lisfuncheon when it came. The Battle of Shiloh, and the American Civil War as a whole, cast a dark shadow that was often felt half a world away.

Hickey’s death as recorded in his Confederate Service Record (Fold3.com)

* I am greatly indebted to Ed O’Riordan who located these letters, which offer a remarkable insight into emigrant life. He also provided me with the transcripts of the letters for use in this post, for which I am most grateful. Thanks are also due to the Hickey family of Lisfuncheon, Clogheen for permission to tell William’s story.

(1) New York Passenger Lists, William Hickey to Parents October 3rd 1853; (2) William Hickey to Parents January 22nd 1854 (erroneously dated 1853); (3) William Hickey to Parents June 1st 1854, Boston Passenger and Crew Lists; (4) William Hickey to Parents October 8th 1854; (5) Ellen Tobin to Father James Hickey February 27th 1859; (6) William Hickey to Family March 4th 1861; (7) William Hickey Confederate Service Record; (8) OR: 536-537, Daniels 1997: 154; (9) OR: 536-537, OR: 538, Daniels 1997: 313, David Ryan to Father James Hickey July 10th 1866;

References & Further Reading

William Hickey Letters.

Boston Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1943. Record for Meridian arrived May 31st 1854.

New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957. Record for Vanguara arrived September 7th 1853.

Daniels, Larry 1997. Shiloh: The Battle that Changed the Civil War.

Official Records Series 1, Volume 10 (Part 1). Report of Col. Daniel W. Adams, First Louisiana Infantry, commanding First Brigade pp.536-537.

Official Records Series 1, Volume 10 (Part 1). Report of Col. Z.C. Deas, Twenty-second Alabama Infantry, commanding First brigade. pp. 538- 539.

Civil War Trust Battle of Shiloh Page

Filed under: Battle of Shiloh, Louisiana, Tipperary Tagged: 1st Louisiana Infantry, Battle of Shiloh, Boston Immigrants, Irish American Civil War, Irish Emigrant Letters, Irish emigration, Shiloh Irish, Tipperary Soldier

August 4, 2013

Scarred Men: The Disfigurements of New York Irishmen, 1863

The first post relating to my work on the New York Irishmen who enlisted in the Union navy in July 1863 looked at their tattoos. However, the marks on their body that they had not chosen for themselves were far more prevalent. Of the 319 Irish recorded as signing on that month, at least 131 exhibited scars or signs of previous illness. Neither were these old men. Of the 131, almost 62% were 25-years-old or younger. Less than 15% were older than 30. The punishment their bodies had taken at such a young age graphically reveals the harsh realities of life for the working classes in major urban centres during the 1860s. (1)

The graphic below has been prepared based on the data from the Irishmen who enlisted at the New York Rendezvous in July 1863. It highlights the extent to which these 131 men were scarred. On some of the records the cause of scarring was also noted; these included burning and smallpox. Other medical conditions were also occasionally mentioned.

The scars recorded on New York Irishmen who enlisted in the Union Navy, July 1863 (Sara Nylund)

Although in the majority of cases the cause of individual scars was not recorded, it is likely that they resulted from a combination of illness, workplace accidents and interpersonal violence. The impact of smallpox on the population was apparent, with a number of men bearing the marks of the disease. 23-year-old Christopher Toole was described as being ‘pitted by smallpox’ while 27-year-old Richard Stretton had a ‘pockmarked face.’ It is probable that smallpox had caused much of the other scarring prevalent among the group, even when it was not specified.

Smallpox was finally eradicated in 1979, but was still a major killer in North America in the 1860s. An infectious virus that caused raised blistering about the body, it had a mortality rate of 15-45%. If you were fortunate enough to survive it, you were likely to be scarred in the areas where the blistering had occurred; 75% of all sufferers had to live with this permanent disfigurement. There had been a number of smallpox epidemics in the United States in the first half of the 19th century, and the disease had ravaged the Native-American population in the late 1830s. Despite the fact that a vaccine had been created, systematic inoculation was not in place during the 1860s. The disease caused 7,058 deaths in the Union army during the Civil War. Some of the July 1863 enlistees may have contracted the disease while children in Ireland- figures for the 1870s show that it remained a deadly illness, claiming the lives of over 7,500 people in Ireland during that decade. (2)

Undoubtedly some of the scarring was as a result of workplace mishaps. Sixteen of the men had worked as Firemen; 45-year-old James Morgan and 25-year-old Michael Rooney both had burn marks on their bodies as a result. Similarly it is possible that 33-year-old machinist Charles Smith lost the little finger of his left hand while operating equipment. However, inter-personal violence had also taken its toll. It is hard to imagine how 29-year-old painter John Browne could have lost part of his right ear on the job. By far the most dramatic cause of scarring among the group belonged to Richard Smith, a 21-year-old machinist. Incredibly he was recorded as having ‘gun shot scars’ on his cheek and his left temple. The fact that he was even alive to enlist in July 1863 seems something of a miracle. Violence was part of everyday reality in working-class New York, and it would have been a fortunate man who navigated his way through life without encountering it.

In a number of cases the recruiters also took the time to note medical ailments. The prospective mariners were stripped for examination before being accepted into the service, leading to the recording of conditions (such as phymosis/phimosis) which were present in even the most private of locations. 34-year-old Fireman Thomas Dalton was the only man in the group unfortunate enough to have his lack of hair recorded, with ‘bald headed’ being jotted into the notes. We also learn that Patrick Sheady, a 22-year-old laborer, was afflicted with varicose veins, 21-year-old laborer Daniel Morrison was flatfooted, while 22-year-old mason John Hennesey had a speech impediment. Each piece of information adds a little more to our picture of these Irishmen and the lives they led.

The scars of these men graphically illustrate the harsh realities of life during this period and serve to dispel any romantic notions we might have about life in the past. Even without the American Civil War, the population had to contend with the threat of disease, fatal accident or violent death, all of which were near-constant companions for many in the poorer areas of New York. Even before joining the naval war, these men had already overcome significant odds to make it as far as the New York Naval Rendezvous in July 1863.

Name

Age

Occupation

Marks/Scars

Thompson, Fenton

17

None

Scar on left shin and right thigh

Power, Michael

19

None

Scar left cheek

O’Connor, Daniel

20

Clerk

Scar left forearm and right groin

Flamming, Michael

20

Harness Maker

Scar left shin

Morrison, Daniel

21

Laborer

Flatfooted

Smith, Richard

21

Machinist

Gun shot scars on cheek and left temple

Fitz, Patrick

21

Coast Pilot

Has had smallpox

Picker, Michael

21

Laborer

Has had smallpox

Riley, Hugh

21

Fireman

Injury on nose, scar right shoulder and thigh

McKeever, Francis

21

Fireman

Loss of index finger left hand, accepted by engineer

Flynn, James

21

Baker

Pitted by smallpox

Meehan, Francis

21

Laborer

Scar ball of left thumb

Donovan, Cornelius

21

Laborer

Scar left groin

Kelly, Thomas

21

None

Scar left hip

Holden, Thomas

21

None

Scar left thumb

Davitt, Joseph

21

None

Scar on back

McGuire, James

21

None

Scar on forehead

McColgan, Edward

21

Clerk

Scar on left arm

Love, William

21

Shoemaker

Scar on left eye

Graham, Peter

21

Laborer

Scar on left heel

Oliver, Thomas

21

Laborer

Scar on left heel

Rogers, Edward

21

Barber

Scar on left leg

Gibbons, Michael

21

Spinner

Scar on left shoulder near neck

Fox, James

21

Hatter

Scar on penis

Brennan, Patrick

21

Laborer

Scar on right eyebrow

O’Connor, Hugh

21

Printer

Scar on right eyebrow

Mouly, Daniel

21

Laborer

Scar on right thigh

Mockler, Thomas

21

Carpenter

Scar right cheek

McCormick, George

21

Bartender

Scars between eyebrows

Drum, Peter

21

Laborer

Scars on forehead

Carmady, Martin

21

None

Several scars on the back

Galligan, Bernard

22

Boatman

Burn on right arm and chest

Sheady, Patrick

22

Laborer

Inequality in size of pupils of eyes. Varicose left side foot and toes

Morrisey, Frederick

22

Moulder

Injury to 2nd finger of left hand

Grady, James

22

Bricklayer

Scar left arm

Pentony, William

22

Carpenter

Phymosis

Donnelly, Henry

22

Boatman

Pitted by smallpox

Smith, James C.

22

Carpenter

Scar left foot

Shaw, Henry

22

Riveter

Scar left thigh and side

McCann, John

22

Boiler Maker

Scar on breast

Herbert, James

22

Laborer

Scar on forehead

Johnson, William

22

Seaman

Scar on left breast

Fahey, John

22

Boatman

Scar on right groin

Mahony, William O.

22

Leather Maker

Scar on right groin

Stone, Thomas

22

Laborer

Scar on right thigh

Carter, Alfred B.

22

Butcher

Scar on the head

Garvey, Jeremiah

22

Laborer

Scar on the right thigh

Newtown, Lewis

22

None

Scar right cheek

Hines, Thomas

22

Boiler Maker

Scar right forearm

Tatfield, William

22

Mariner

Scar right knee

Hennesey, John

22

Mason

Scar with depression above left brow. Impediment in speech

Cabb, William

22

Laborer

Scars right leg

Brown, John

22

Laborer

Several scars on left thigh

Whitty, Michael

22

Mariner

Slight strabismus

Reilly, John

22

Laborer

Small scar above right eyebrow

Sutton, Michael

23

Bootmaker

Burn on chin, breast and right arm. Pitted by smallpox

Toole, Christopher

23

Porter

Pitted by smallpox

Finnigan, Daniel

23

Plumber

Scar left cheek

Hennessey, James

23

Laborer

Scar left eyebrow

Rigby, William

23

Boiler Maker

Scar on head

Kane, Joseph

23

Clerk

Scar on left cheek

Oswald, William

23

Brass Finisher

Scar on right forearm

Riley, Thomas

23

Laborer

Scar on side of throat

Gibson, James

23

Seaman

Scar on the back

Bradley, Peter

23

Laborer

Scars on right thigh

Cautlon, Edward

23

None

Small tumor left wirst

Allan, William

24

Laborer

Cross right breast, heart left breast, scar left leg

Flynn, Patrick

24

Laborer

Scar between eyebrows

Rodgers, Peter

24

None

Scar left buttock

Cavanagh, James

24

Boatman

Scar left groin

Ryan, John

24

Moulder

Scar left leg

Minar, Frank

24

Seaman

Scar on the abdomen

Campbell, John

24

Fireman

Scar right groin

McIlwain, William

25

Painter

Hairy noerus? on abdomen, scar on left groin

Vail, John

25

Hatter

Injury on right leg

O’Rourke, Patrick

25

Mason

Scar between eyebrows

Marron, Owen

25

Shoemaker

Scar left groin

Sullivan, Jeremiah

25

Fireman

Scar on forehead

May, James

25

Silk Weaver

Scar on left arm (had smallpox)

Rooney, Michael

25

Fireman

Scars from burns left elbow and forearm

Hoolihan, Patrick

25

Laborer

Scars on forehead

Glass, Robert

26

Laborer

Scar on left knee and Phymosis

Kearney, John

26

Laborer

Scar on right

Conolly, John

26

Fireman

Scar on right breast

Daly, John

26

Laborer

Several small scars on the back

Kenney, Patrick

26

Laborer

Slightly pitted by smallpox

Bradshaw, John

26

Laborer

wound of left hand

Welsh, Michael

27

Fireman

Lost portion of third finger, pitted by smallpox

McGuire, George

27

Plumber

Phymosis, scars on both wrists

Stretton, Richard

27

Mariner

Pockmarked face

Healy, John

27

Bootfitter

Scar left groin

O’Brien, Martin

27

Laborer

Scar left shin and right shoulder

Nolan, Patrick J.

27

Painter

Scar on left wrist

McNamara, Edward

27

Laborer

Scar on loins

Davison, William

27

Laborer

Scar on right arm

Smith, James

27

Fireman

Scar right breast

Caffray, George A.

28

Laborer

? left ankle

Butney, William

28

Fireman

Injury of littlefinger on right hand

Murphy, Michael

28

Carpenter

Lost ?, scars on left forearm

Smith, Peter

28

Morocco Dresser

Scar above left thumb

Dowd, Murthy

28

None

Scar on the right hip

Clark, James

28

None

Scars right leg

Mordaunt, Michael

28

Machinist

Slight ? and weakness both sides

Kane, Edward D

29

Laborer

Has had smallpox

Browne, John

29

Painter

Lost portion of right ear, scar on right thigh

Harkins, John

29

Bricklayer

Scar on forehead and left arm

Hogan, Patrick

29

Laborer

Scar on right leg

Fitzgerald, James

29

Coach Painter

Various scars on the left leg

McCarthy, John

30

Laborer

Scar left thigh

Phelan, Edward

30

Waiter

Pitted by smallpox

McEvoy, James

30

Fireman

Scar left leg

King, Daniel

30

Fireman

Scar scalp and forehead

Burke, Patrick

31

Boatman

Injury left thumb

McHugh, Peter

31

Laborer

Scar on the right leg

Wise, Matthew

31

Laborer

Scar right thigh

McGuire, Thomas

31

Fireman

Scars arms, legs, body & c.

Connell, Timothy O.

32

Cooper

Scar on left arm

Woods, Henry

32

Fireman

Scar right ear

Smith, Charles

33

Machinist

Lost little finger left hand

Hurley, John

33

Mariner

Scar on skin of left eye

Mulcahey, Michael

33

Laborer

Scar on the belly

Dalton, Thomas

34

Fireman

Bald headed, scar on neck

Manning, Thomas

34

Laborer

Little finger left hand crooked

Ritchey, John

36

Sailor

Macula left leg

Gibson, John

36

Sailor

Pitted by smallpox

Nimmo, George

37

Machinist

Front upper teeth (lost)

Connor, William O.

37

Carpenter

Scar on chest

Brooks, George

37

Seaman

scar on left knee

Kennedy, John

38

Laborer

Slight deformity left arm, pitted by small pox

Bannerman, Francis

40

Fireman

Scar on left thigh

Morgan, James

45

Fireman

Marks of burn by hot tin? about right elbow

Table 1. Marks and scars (excluding tattoos) of Irish enlistments in the New York Naval Rendezvous, July 1863 (3)

*I am indebted to illustrator Sara Nylund for producing the superb diagram of the scars that were present on these Irishmen.

(1) Naval Enlistment Returns; (2) Fenner et al. 1988: 240, Houghton & Kelleher 2002: 91, Behbehani 1983: 483, 485; (3) Naval Enlistment Returns;

References

Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns, New York Rendezvous, July 1863.

Behbehani Abbas M. 1983. ‘The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease’ in Microbiological Reviews December 1983, pp. 455-509.

Fenner Frank, Henderson Donald AInslie, Arita Isao, Jezek Zdenek, Ladnyi Ivan Danilovich 1988. Smallpox and Its Iradication.

Houghton Frank and Kelleher Kevin 2002. ‘Smallpox in Ireland- An Historical Note with Possible (and Unwlecome) Relevance For the Future’ in Irish Geography, Vol. 35(1), pp. 90-94.

Filed under: General, Navy, New York Tagged: American Civil War Scars, Irish American Civil War, Naval Recruitment, New York Firemen, New York Irish, New York Smallpox, Sailor Scars, Union Recruitment

July 31, 2013

Marked Men: The Tattoos of New York Irishmen, 1863

The enlistment records of many Irish recruits during the Civil War provide detail on age, height, hair/eye colour and complexion. Although informative, this data still leaves us without a picture of life experience, or any insight into character. One exception was those men who enlisted in the Union navy. The marks and scars they acquired during their lifetime were recorded on enlistment, providing us with a unique opportunity to garner more detail about both their appearance and their personalities. Perhaps most fascinating of all are those marks that the Irishmen had chosen for themselves- their tattoos.

A German Stowaway at Ellis Island. Although taken in 1911 this gives an idea of the types of tattoos prevalent (New York Public Library Digital Gallery, Digital ID: 418057)

I have recently examined the enlistment records of the New York Naval Rendezvous for July 1863 to create a database of those Irishmen who enlisted during that month, 150 years ago. Of 1,064 men who were recorded as signing on between 1st and 31st July, a total of 319 were listed as being of Irish birth. They will form the topic of a number of posts on the site in the coming days. Naval recruits were seen as being of the rougher sort, often with a different set of motivations for enlisting when compared with other branches of service. Many were from extremely poor backgrounds and inhabited some of the most notorious districts of New York, such as the Five Points. By and large they were working class men- to study them is to examine the reality of urban life for the majority of Irish emigrants.

In 1860s New York, tattooing was most popular among the working classes. There were many different motivations for getting ‘inked’, be it for identification purposes, to express feelings for a loved one, or simply to fit in. Of the 319 Irishmen who enlisted in the navy from New York in July 1863, over 30 of them had tattoos:

Name

Age

Occupation

Tattoo

Allan, William

24

Laborer

Cross on his right breast, heart on his left breast

Auction, Martin

20

Laborer

Anchor on his right hand

Breshnan, John

23

Printer

“hoha”? On his right forearm

Cahill, Patrick

21

Seaman

Cross on his right arm

Cahill, Peter

30

Fireman

Women on both his forearms

Carter, William R.

16

None

“12″ on his left forearm

Cautlon, Edward

23

None

Name on his left forearm

Conway, William

21

Painter

“42″ on his left arm

Coulter, James

21

Mariner

Cross on his right arm, anchor and heart on left arm

Crowley, John

29

Mariner

Anchor on his right hand

Donnelly, Patrick

30

Laborer

Crucifix on his left forearm, name on his right forearm

Flood, Thomas

21

Printer

Soldier on his left forearm

Grady, James

22

Bricklayer

“J.G.” and star on his right forearm

Gugerty, Michael

23

Trunk Maker

Monument? on his right forearm

Hickay, William

34

Mariner

Crucifix on his right forearm

Hill, Thomas

21

Laborer

Star on his left hand

Holden, Patrick

22

Fireman

“13″ on his right forearm

Keough, Philip

23

Bricklayer

Tattooed on the arms

Layton, Henry

22

Mariner

Star on his left hand

Mansfield, Thomas

17

None

Blue spots on his right arm (tattoo or scar?)

McCarthy, John

30

Laborer

“J.McC.” on his left forearm

McCarthy, John

35

Mariner

“M.P.” on his left wrist

McGill, James

35

Mariner

A.M.’ on his right forearm

McNally, William

41

Mariner

Woman and “I.C.” on his right arm

Murray, Francis

21

Laborer

“F.M.” on this right arm

Murray, Patrick

21

Laborer

Name on his right arm, crucifix on his left arm

Reilly, John

25

Machinist

Anchor on both his forearms

Smith, Henry

28

Mariner

Cross on his right forearm

Staldon, Charles

21

Shoemaker

Cross on his right arm

Sweeney, Miles

23

Shipsmith

“M.S.” on his right forearm

Whilon, Robert

23

Fireman

” B. O’Brien” on his right forearm

Wogan, William

22

Laborer

“17″ and “East River” on his right forearm

Table 1. Tattoos of Irish enlistments in the New York Naval Rendezvous, July 1863 (1)

What was the process these men went through to get tattooed? The best known tattoo artist of the period was Martin Hildebrandt, who operated throughout the American Civil War and in the post-war years had a New York tattoo workshop. In 1876 the New York Times visited him to learn more about the process:

Mr Hildebrandt, with the true modesty of an artist, exhibited his book of drawings. All you had to do, in case you wanted to be marked for life, was to select a particular piece, and in a short time, varying from fifteen minutes to an hour and a half, you could, presenting your arm or your chest as an animated canvas to the artist, have transferred on your person any picture you wanted, at the reasonable price of from fifty cents to $2.50. (2)

Of course many of the working class Irishmen who revealed their tattoos to the recruiters in July 1863 would have been inked by amateur tattooists, often with a varying degree of competence. Hildebrandt’s method was to take a half dozen No.12 needles, that he ‘bound together in a slanting form, which are dipped as the pricking is made into the best India ink or vermilion. The puncture is not made directly up and down, but at an angle, the surface of the skin being only pricked.’ Wet gunpowder and ink were also sometimes used as a colorant to mix into the needle-marks. Once the tattoo was completed, blood and excess colouring were washed off the skin using either water, urine or sometimes rum and brandy. (3)

Examples of some late 19th century tattoos (Wikimedia Commons)

What of the different types of tattoos? In his examination of American seafarers’ tattoos between 1796 and 1818, Ira Dye developed a classification for the types of tattoos he encountered. The July 1863 New York Rendezvous sample shows that a number of the Irishmen had elected for similar designs. Initials and names tended to be the most common form. Men like John McCarthy and James Grady were probably concerned with people being able to identify them should some mishap occur, and wanted the initials to serve as a form of identity tag. William McNally had the initials ‘I.C.’ beneath the image of a woman, and it may well be that these were the initials of a loved one. Robert Whilon had ‘B. O’Brien’ tattooed on his arm. This may either represent a woman, friend or it is possible that he was one of many men who elected to enlist under a false name. (4)

A number of the men sported anchors, the tattoo most quintessentially associated with sailors. Although John Crowley and John Coulter were mariners, it is not clear if the other men with anchors- Laborer Martin Auction and Machinist John Reilly- had previous naval experience. Stars were also a popular motif, as were crucifixes. Depictions of crosses may have had some religious significance, but there is also a suggestion that sailors selected them to mark them out for Christian burial; it may also have been regarded as lucky. Within this group of Irishmen crosses were the most common tattoo, with eight of the men carrying them. (5)

An interest in love and women generally can be seen with the selections a number of the men made. William Allan had a heart on his chest, while Fireman Peter Cahill clearly saw himself as somewhat of a paramour, with women on both his arms. Thomas Flood has also elected for a figure, but he chose a soldier rather than a woman, perhaps to remember service in the army or to recall a relative or friend who was fighting for the North. By far the most intriguing set of tattoos are the numbers that adorned some of the men. William Carter, a 16-year-old boy with no profession, had ’12′ on his arm. Painter William Conway had ’42′, Fireman Patrick Holden ’13′ and Laborer William Wogan ’17′ and ‘East River.’ I have been unable to ascertain what these numbers represent. Having considered areas or wards of the city, ladder companies and infantry regiments, none seem to offer a definitive answer. I would be interested to learn if any readers have come across references to such tattoos before, or if they have some suggestion as to what these numbers might represent.** (6)

Tattoos are most commonly associated with sailors in this period. What is fascinating about this group is that although all of them were bound for the navy, it was clear that many of the men who bore tattoos had no previous maritime experience. This allows us to envisage a scenario where a significant proportion of the working class Irish population (and indeed the working class generally) wore tattoos- indeed it must have been a common sight in areas like the Five Points. I hope in the future to extend my look at the Irish recruits in the navy and along the way discover more regarding the tattoos that were prevalent among the Irish community of New York.

*I am indebted to Dr. Matt Lodder for graciously providing information regarding sources and for his advice generally regarding 19th century tattooing and its interpretation.

**With regard to this question, see the contribution by Marc Hermann in the comments section below, which seems to confirm that these are most probably the numbers of Fire Engine, Ladder and Hose Companies.

(1) Naval Enlistment Returns; (2) New York Times 16th January 1876; (3) Dye 1989:531; (4) Ibid:542; (5) Ibid:542, 547; (6) Ibid:544-545;

References

Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns, New York Rendezvous, July 1863.

New York Times 16th January 1876. Tattooing in New York, A Visit Paid to the Artist.

Dye, Ira 1989. ‘The Tattoos of Early American Seafarers, 1796-1818′ in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 133, No. 4, pp. 520-554.

New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

Filed under: Navy, New York Tagged: 19th Century Tattoo, American Civil War Tattoos, History of Tattooing, Irish American Civil War, Irish Tattoos, Navy Tattoos, New York Tattoo, Soldier Tattoos

July 22, 2013

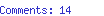

‘Father of the American Band’: The Story of Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore

Irishman Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore served as a musician and stretcher-bearer in the 24th Massachusetts Infantry during the American Civil War. His incredible post-army musical career includes penning When Johnny Comes Marching Home and performing some of the biggest musical shows ever seen, along the way becoming one of the icons of nineteenth century America. Gilmore expert Jarlath MacNamara brings us his remarkable story in the latest Guest Post on the site.

Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore was born outside Dublin in 1829, and from an infant was raised in Ballygar, Co Galway. He developed a love of music learning to play fife and drum and later studied it in detail in Athlone, Co Westmeath.

Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore (Library of Congress)

Boston and the Civil War

As a 19-year-old he emigrated with one million others, escaping the Great Famine in 1849. Arriving in Massachusetts he conducted bands in Salem and Boston and developed his craft further as an innovative conductor and band leader. Whilst in Boston he developed the initial 4th July Celebrations and the Boston Promenade Concerts, and was invited to lead the inauguration parade of President Buchanan in Washington D.C. in 1857 (the first of eight inaugurations Patrick participated in). In 1860 Gilmore’s band played to both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions- Abraham Lincoln was selected to run at the latter. At the outset of the Civil War both he and his band volunteered en masse for service with what became the 24th Massachusetts Infantry, setting sail to take part in the famous Burnside Expedition to the Carolinas in early 1862.

Nana Mouskouri performs ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home’

Patrick saw action at Roanoke, New Bern and Tranter’s Creek, and is recorded as playing music for his Union colleagues as well as entertaining Confederate prisoners and acting as a stretcher-bearer on the battlefield. In 1863 he composed a song that still stands the test of time; a ballad which mentions neither victor nor vanquished, cause or result: “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” He was inducted into the American Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970 for this composition. Patrick had written the song under the pseudonym of ‘Louis Lambert.’

‘We are coming Father Abraam, Thee Hundred Thousand More’ by P.S. Gilmore (Jarlath MacNamara Collection)

“Gilmorean Concerts”

Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore organised four great “Gilmorean Concert Jubilees” (‘Gilmorean’ was a word created by Harper’s Weekly to describe his massive concerts, which had no compare). They were as follows:

1. In 1864 Gilmore was asked by General Banks and Governor Andrews of Massachusetts to organise the inauguration ceremony of Governor Michael Hahn, the first Union Governor elected during the Civil War in Louisiana. For this occasion Gilmore conducted a band of 500 musicians assisted by a choir of over 5,000 voices, in front of an audience of over 35,000 in Lafayette Square, New Orleans.

2. In 1869 Gilmore organised the National Peace Jubilee Festival in Boston which took place over five days; 1,000 musicians were accompanied by a choir of 10,000 before an estimated audience of 50,000 people. Designed to help heal the wounds of the Civil War, President Grant and his cabinet were in attendance.

Johann Strauss II Jubilee Waltz dedicated to Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore and written for the International Peace Jubilee

3. In 1872 Gilmore organised the World Peace Jubilee which outwardly was designed to celebrate the end of the Franco-Prussian War in Europe, but which Gilmore viewed as a test to gauge where both his band and that of the U.S. Marines were placed compared with international leaders in music. The festival took place over 18 days in a custom built stadium in Boston. Participating bands included the French band of the Garde Républicaine, the Prussian band of the Kaiser Franz Grenadier Regiment, the band of the Royal Grenadier Guards, the orchestra of Johann Strauss Jnr., and an Irish band from Dublin. Gilmore had to pay Strauss to appear, as the Austrian was apparently concerned that his locks would be removed by warring Indians. By the end of the festival Gilmore realised that both his band and that of the U.S. Marines were vastly inferior to the bands of the Old World, and so he instituted new standards which survive to this day and led to the United States being accepted as a centre of performance excellence.