Damian Shiels's Blog, page 50

October 12, 2013

‘Equaled by Few- Surpassed by None’: Colonel James Mallon and the Battle of Bristoe Station

At least 150,000 Irish-born men fought for the Union during the American Civil War. However this figure does not include those first-generation Irish, born in Canada and the United States, who considered themselves just as Irish as anyone born on the Emerald Isle. In an antebellum society where Know-Nothingism and anti-Catholic sentiment were widespread, ethnicity and religion bound Irish-Americans together in a tight-knit community. Tens of thousands of these Irish-Americans laid down their lives during the war, men like James A. Mulligan of ‘Mulligan’s Irish Brigade’ and the oft-quoted Peter Welsh of the 28th Massachusetts, Irish Brigade. Another was Colonel James Edward Mallon, who died 150 years ago this October at the Battle of Bristoe Station.

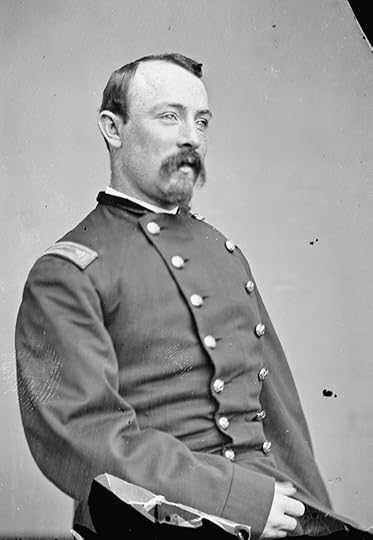

Colonel James E. Mallon (Library of Congress)

James E. Mallon was born on 12th September 1836 in Brooklyn to Hugh and Ann Mallon. His parents had emigrated from Co. Armagh to the United States in 1822. When James was eight years old his father died, passing away on 9th July 1845. He got his first job at fifteen, working in the Wholesale Commission Business for Wright, Gillet & Rawson and later Holcomb & Harvey. Before long he decided to set up for himself and procured positions on the floor of the Corn Exchange and Produce Exchange. James was doing well for himself, quickly becoming a well-respected member of New York’s merchant class. He was described as ‘a most intelligent, energetic and upright business man, faithful in the performance of all his duties, and scrupulously exact in all his mercantile transactions.’ (1)

Life in the pre-war years was good for James. He became a Private in Captain Roblet’s Company of the 7th New York State Militia before the war, often called the ‘Silk Stocking’ regiment, as many of its members were involved in business and represented the upper levels of New York society. On the 1st September 1859 he married Anna E. McCormick at the Church of the Assumption in Brooklyn; they celebrated the birth of their first child, James Edward, less than a year later on 16th August 1860. With the outbreak of the American Civil War Private Mallon marched off to war with the 7th New York State Militia on the 19th April 1861, bound for Washington, D.C. (2)

The 7th New York State Militia depart for the War (Thomas Nast/ New York State Military Museum)

The 7th did not spend long in Washington, being released from their duties at the capital on 31st May. James was eager to get back to the front, and enlisted in the 40th New York Infantry Regiment, becoming a Second Lieutenant in Company K on 6th August 1861. The 40th was known as the ‘Mozart’ Regiment, as it had received assistance from the Democratic General Committee of Mozart Hall in New York when it was forming. There were more personal reasons for James’s choice, however- his sister Teresa was married to the regiment’s Colonel, Edward Johns Riley. (3)

James became a First Lieutenant in September 1861. The start of 1862 brought more good news for him and his family, as his second child Anna was born on 4th January 1862. He clearly impressed his superiors in the Army of the Potomac, as Major-General Phil Kearny appointed him as an aide; he also acted as Assistant-Adjutant-General on Kearny’s staff. In August 1862 Mallon was on the move again, when he was appointed Major in the strongly Irish 42nd New York Infantry. This was another formation with strong Democratic Party links, and was known as the Tammany Regiment. His younger brother Thomas kept it a family affair, following his sibling into the unit as a Second Lieutenant. (4)

Major Mallon’s organisational talents meant that he initially spent little time with his new regiment. He was appointed Acting-Assistant Provost Marshal of Hooker’s Grand Division of the Army of the Potomac and later performed the same role for the Second Corps. On St. Patrick’s Day 1863 James Mallon was appointed to the command of the 42nd New York Infantry. One of his first acts was raising funds within the regiment for the relief of the Poor in Ireland, a cause to which he personally contributed $25. The 42nd’s contribution of $493.50 was sent to the Head of the Fenian Brotherhood in New York, John O’ Mahony, together with the attached sentiment:

We, of the Tammany Regiment, aware of the present distress existing in Ireland, beg you to transmit to the Rt. Rev. Dr. Keane, Bishop of Cloyne, the following amount. We hope it may contribute, if only in a small degree, to stop the stream of Irish emigration, and to keep our friends from starvation, so that, this war in which we are engaged being ended, there may be some of our race left at home whom we can aid in placing beyond fear of recurrence both the miseries of famine and the horrors of landlordism. (5)

Colonel Mallon commanded his regiment at the Battle of Gettysburg in July, when it played an important role in the repulse of Pickett’s Charge on the final day of the engagement. During the same battle his brother Thomas was seriously wounded, an incident which must have greatly disturbed James. With victory secured and Lee on the retreat, Mallon was detached to New York in the aftermath of the Draft Riots to bring conscripts back to the Army. He remained there during the months of August and September, undoubtedly taking the opportunity to spend time with his wife, three-year-old son and 18-month-old daughter. He departed New York telling his friends that he was leaving ‘for the next fight.’ (6)

The 42nd New York ‘Tammany Regiment’ memorial at Gettysburg. Of the 182 men who contributed to the Irish Relief Fund only two months before, 13 would die as a result of this battle (Photo: J. Stephen Conn)

When A.P. Hill launched his attack against the Union Second Corps at Bristoe Station on 14th October 1863, Colonel James Mallon was in command of the 3rd Brigade of the 2nd Division at the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. One of the members of Mallon’s 42nd New York described the fighting:

We had a sharp fight with the enemy at Bristow Station on the 14th inst. Our brigade, having been posted along the side of the railroad, which was an admirable position, did good service. Besides shattering a column of rebels that essayed to dislodge us, we captured five pieces of artillery and two stands of colors, and took a number of prisoners. While the battle lasted, it was one of the most desperate ever witnessed by those engaged. Our pickets, posted about one hundred yards in front of the line of the railroad, were driven in by the enemy’s skirmishers; and quickly after the rebel column steadily advanced across the field. Their front line was remarkably well dressed, and with colors flying they presented a good appearance. Our men preserved their fire until this line was quite close, when volley after volley was poured into them. Their advance was checked; their line was broken into pieces, and hundreds of them slain. Our loss is as follows:- one officer and three enlisted men killed, thirty-one men wounded, and twenty-three men missing. These are the entire casualties of our brigade. (7)

The one officer killed was Colonel James Mallon, struck down at the age of just 27. He was reported variously as having been struck by a bullet in the stomach or right breast, dying on the field within an hour of receiving his wound. It appears that Mallon received his mortal wound while rallying a part of of the 42nd New York’s line that was giving way. Lieutenant-Colonel Ansel Wass remembered that:

During the advance of the enemy, and while the fire was hottest, a part of the line of the Forty-second New York, composed principally of conscripts, and much exposed where a road crossed the track, gave way. In attempting to rally them Colonel Mallon, commanding the brigade, was shot through the body and died in an hour afterward.

Mallon’s actions had helped to preserve the integrity of the line. One of his men remembered:

He was fully competent to take command of not only a brigade, but a division, or even a corps; as a gallant and dashing field officer, Col. James E. Mallon was equaled by few- surpassed by none. The bullet that pierced him, struck down for ever one of the brightest stars in our Irish military horizon- one to whom we, Irish soldiers, used to point with proud feelings, for his dashing bravery on the field of battle. In camp and bivouac he was a strict disciplinarian- strict, perhaps, to a fault in the opinion of some; but whatever may be or have been the opinions of a few on this point, none will deny that in Col Mallon were combined the qualities of a true soldier. He was an accomplished scholar, and that, combined with military genius, caused his society to be courted by those within his sphere. In his death the army has sustained an irreparable loss, and old Ireland a true friend and enthusiastic lover. I will not attempt to describe what must have been the feelings of another of Ireland’s valiant and faithful sons , Captain William O’Shea, as he took the dying Colonel from where he had fallen, and had him placed in the rear. Such feelings may be imagined, but cannot be penned. Over the grave of the heroic Mallon let there be an Irish shamrock planted, and let it be strewn with the choicest flowers that will bloom each springtime, in token of the Irish ashes that under them moulders. (8)

The Bristoe Station Battlefield (Jerrye & Roy Klotz)

James Mallon’s remains were removed to his home on Little-Water Street in Brooklyn, from where he was taken for burial on 21st October 1863. He lies in Range 2, Plot 16 of Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn. His widow Anna never remarried. She died at 5am on 14th January 1913 following a long illness, almost 50 years after her husband. She was buried with him in Holy Cross Cemetery. (9)

(1) Irish American Weekly 14th July 1888, New York Death Newspaper Extracts, New York Times 21st October 1863; (2) New York Times 21st October 1863, James E. Mallon Widow’s Pension File; (3) New York Adjutant General Report, Irish American Weekly 14th July 1888; (4) New York Adjutant General Report, James E. Mallon Widow’s Pension File, New York Times 21st October 1863; (5) New York Times 21st October 1863, Irish American Weekly 9th May 1863; (6) New York Times 21st October 1863; (7) Hunt 2003: 184, Irish American Weekly 31st October 1863; (8) Official Records: 283-4, Irish American Weekly 31st October 1863; (9) Hunt 2003: 184, James E, Mallon Widow’s Pension File;

References & Further Reading

Hunt, Roger D. 2003. Colonels in Blue: Union Army Colonels of the Civil War: New York.

New York Irish-American Weekly 9th May 1863. Relief from the Tammany Regiment.

New York Irish-American Weekly 31st October 1863. The Battle of Bristow Station: From The Tammany Regt.- 42d N.Y. Vols.

New York Irish-American Weekly 14th July 1888. Brooklyn Echoes.

New York Times 21st October 1863. Acting Brig.-Gen. James E. Mallon.

New York, Death Newspaper Extracts, 1801-1890 (Barber Collection) for Hugh Mallon.

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 29 (Part 1). Report of Lieut. Col. Ansel D. Wass, Nineteenth Massachusetts Infantry, Commanding Third Brigade.

James E. Mallon Widow’s Pension File (WC25436).

New York Adjutant-General Report 40th New York Infantry.

New York Adjutant-General Report 42nd New York Infantry.

Civil War Trust Battle of Bristoe Station Page

Bristoe Station Battlefield Heritage Park

Filed under: Armagh, Battle of Bristoe Station, Irish Colonels, New York Tagged: 42nd New York Infantry, Armagh Veterans, Battle of Bristoe Station, Colonel James E. Mallon, Irish American Civil War, Mozart Regiment, Relief of the Poor of Ireland, Tammany Regiment

October 5, 2013

Broken Homes: Irish Soldiers’ Attempts to Reunite their Families

Previous posts have looked at the ‘Information Wanted’ ads placed in Irish-American newspapers during the 1860s, where family members sought to discover the fate of soldiers who went missing during the war (see here and here). The conflict split families apart, and papers like the Boston Pilot also carried ads from serving and recently mustered-out soldiers who could not locate their wives and children. For some men, their proximity to death prompted them to try to get in touch with family whom they may not have seen in many years.

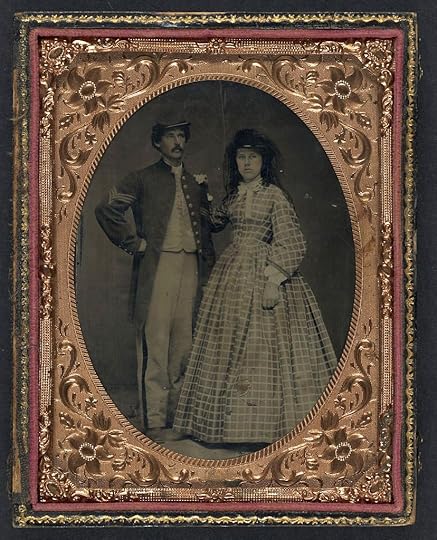

A Union Sergeant and his Wife during the American Civil War (Library of Congress)

Some soldiers had not communicated with their wives since their enlistment, and sought to re-establish contact on their muster out. Such was the case with Bernard Corrigan, who placed his ad in the Pilot on 12th June 1862:

Information Wanted OF CATHERINE ARMSTRONG (husband’s name Bernard Corrigan), who, when last heard from, nine months ago, was in or about South Margin street, Boston, Mass. Her husband, who had enlisted, is now home again, and wants her to come to him. Any information concerning her will be thankfully received by Bernard Corrigan, Savannah, Carroll county, Ill.

It is not clear if Catherine was alive or dead at the time of the ad, but it seems probable that Bernard was not successful in locating her. By 1870 the then 36-year-old Bernard was farming in Mount Carroll, Illinois and had remarried. His second wife, 22-year-old Mary had borne him two sons, four-year-old James and two-year-old Thomas. (1)

Tipperary native William Welch was about to embark on some tough fighting during the Atlanta Campaign when he decided to launch a concerted effort to contact his siblings, wife and children in 1864. He had enlisted at the age of 32 and was described as 5 feet 4 1/2 inches in height, with dark hair, blue eyes and a light complexion. Perhaps fearing that he might not survive the war, he placed the following two ads in July 1864:

Information Wanted OF MARY ELLEN WELCH, before marriage her name was Ryan, together with her children Hugh Jane [Eugene] Welch, Thomas and Michael Welch; when last heard from they were at Helena, Arkansas, about four years ago. I (William Welch) left them in Green [Greene] county, Illinois; since then I have joined the Army of the Cumberland, and can get no information of them. Mary Ellen Welch is my lawful wife, and the above named children are my lawful heirs. Any information respecting them will be thankfully received by William Welch, Co D, 129th Ill Vols, Inf’y, 1st Brigade, 3d Division, 20th Army Corps, Army of the Cumberland, via Chattanooga.

Information Wanted OF JOHN, Thomas, Mary and Margaret WELCH, who left parish of Killskully [Killoscully], county Tipperary, about nine years ago. Any information will be thankfully received by their brother, William Welch, Co D, 129th Ill Vols, Infantry, 1st Brigade, 3d Division, 20th Army Corps, Army of the Cumberland, via Chattanooga.

Thankfully William survived the war and was reunited with his family. The 1870 Census finds him farming in Greene County with his wife Mary and three sons. In 1880 he received an invalid pension based on his service, and after his death Mary received a widow’s pension. (2)

Other men had clearly been separated from their wives and children for a number of years before the war. William Powers had not seen his wife and child for a nearly a decade when he placed an ad in the Pilot on 2nd August 1862. He was then serving at Hilton Head, South Carolina with the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. Perhaps it was the war itself that prompted him to try to get back in touch:

Information Wanted OF the wife and child of WILLIAM POWERS, who went to Canada West in 1853 from Thorndike, Mass. Her father’s name was John Shannon. Any information will be thankfully received by George Bradshaw, Spraguetown, Connecticut, or her husband, William Powers, Co E, Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, Hilton Head, South Carolina.

William survived the war and lived until 1907, although it is unclear if he ever established contact with his family. (3)

James Reily had married Margaret Thornton in Galway City on 27th May 1844 and later emigrated to the United States. As with William Powers, he had not seen his wife and daughter for a number of years before the war. A butcher by trade, James enlisted in the army at the age of 32 in March 1862. He was described as 5 feet 6 inches in height, with brown hair, hazel eyes and a light complexion. It was while stationed in Corinth, Mississippi with the 12th Illinois Infantry that he made the decision to seek out Margaret and his daughter. His ad appeared on 21st March 1863:

Information Wanted OF Mrs MARGARET REILY, and daughter, Bridget, of the town of Galway, Ireland, and Mrs Mary Anderson and husband; when last heard from, December 5th 1856, were living on corner of F and 23d streets, Washington, District of Columbia. Any information of them will be thankfully received by her husband, James Reily, Company K, 12th Regiment Illinois Infantry, Corinth, Mississippi.

The ad James placed in the Pilot seems to have worked and he got back into contact with Margaret. Two months after his appeal appeared in the newspaper the Galwegian was part of a detachment of the 12th Illinois sent to guard the Tuscumbia Bridge on the Hatchie River. The post was described as ‘swampy and sickly’, and after some weeks James contracted chronic diarrhoea. On the 10th September he was granted a 30 day furlough to travel to Washington D.C. and visit his family for the first time in 6 years. The reunion was shortlived- James Reily died from his illness on 2nd October 1862. (4)

Peter Smith’s wife Dora had accompanied him on his way to enlist in the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery, but before they had an opportunity to say goodbye to each other they became separated in Syracuse. Peter had carried on with his enlistment, but placed his ad in order to find Dora on 1st November 1862. The whole affair must have been very upsetting- Peter went so far as to offer a $10 reward for anyone who could help him find his wife:

$10 Reward

Information Wanted OF Mrs DORA SMITH, wife of Peter Smith. They became separated from each other on the cars of Syracuse, NY, on the 28th of last July. He enlisted in the Second New York Artillery, and is now a paroled prisoner at Annapolis, Md. The above reward will be given for information of where she now is. Address Rev J F Bradley, Annapolis, Md, or Peter Smith, 2nd New York Artillery, Com B, Paroled Camp, near Annapolis, Md.

Peter had been 44-years-old when he had joined up on 28th July. He had been captured at Manassas on 27th August 1862 and was paroled three days later. The Irishman was discharged for disability from Fort Corcoran on 22nd February 1864. Peter’s fate after his discharge and whether or not he found Dora are unknown. (5)

Laurence McKey placed his appeal in the Pilot on 5th December 1863. He had been stationed at Fort Leavenworth with the 2nd Kansas Cavalry when he fell ill. His wife Mary grew increasingly distressed about him and eventually decided to set out for Fort Leavenworth from their home in Kansas City. Three months later Laurence was transferred to Kansas City Hospital, only to find his wife missing:

Information Wanted OF MARY McKEY, wife of Laurence McKey, of the Second Kansas Cavalry. She left her home in Kansas City about three months ago, for Fort Leavenworth, and from there she started for Weston, where she was seen; when she left, she had on a purple colored dress, black silk shawl, and small spotted shaker on her head. She was out of her mind when she left. She is a native of Tahart, county Cavan, and is about the medium size. Her husband, Laurence McKey, has been in Benton Barracks Hospital for 9 months and 18 days, but is now in Kansas City Hospital. Any information concerning her will be thankfully received by Laurence McKey, care of Rev. Bernard Donnolly, Kansas City, Missouri.

I have not been able to trace Laurence or Mary after this date or discover if they were reunited. (6)

There must have been many hundreds of Irish families who were separated by the American Civil War. Some men had served in uniform for the duration of the conflict, surviving years of battle and campaigning to eventually end their service by marching in the Grand Review in Washington, D.C. When these soldiers left the capital to return to their homes it should have heralded the start of a new chapter in their lives. Unfortunately for some men, such as William Murphy, their task was instead to locate their family and try to piece their lives back together. He placed his Information Wanted advertisement in the Pilot of 1st July 1865. As with so many of the others, it is unclear if he was ultimately successful:

Information Wanted OF Mrs ELLEN MURPHY, formerly of Cleveland, Ohio, but who left that city for St Louis six years ago and is now supposed to reside there. Any information of her whereabouts will be thankfully received by her husband, who has served four years and a half in the army and has just returned home. Direct to William Murphy, 23 Hope street, Chicago, Illinois.

(1) 1870 US Census, Information Wanted; (2) Illinois Civil War Descriptive and Muster Rolls, 1870 US Census, William Welch Pension Index Card, Information Wanted; (3) William H. Powers Pension Index Card, Information Wanted; (4) Illinois Civil War Descriptive and Muster Rolls, James Reily Widow’s Pension Index, Information Wanted; (5) New York AG Report: 983, Information Wanted; (6)

References

Boston Pilot Information Wanted Database, Boston College

Illinois Civil War Descriptive and Muster Rolls Database

1870 US Federal Census

James Reily Widow’s Pension File WC110993

William H. Powers Pension Index Card

William Welch Pension Index Card

New York Adjutant General Report 2nd New York Heavy Artillery

Filed under: Women Tagged: 12th Illinois Infantry, 3rd Rhode Island, Boston College, Boston Pilot, Information Wanted, Irish American Civil War, Missing of the American Civil War, Widow's Pensions

October 2, 2013

Remembering the Irish of the American Civil War in Tipperary

I had the great privilege at the weekend of being the after-dinner speaker for the Tipperary Remembrance Trust event. The Trust is dedicated to the memory of all Irish men and women who have died worldwide in the cause of peace and freedom. The President of Ireland Mary McAleese dedicated the Trust’s Memorial Arch in Tipperary Town in 2005, and every year since the Trust has held a dinner and lecture, followed the next day by a memorial service in the Garrison Church and a wreath laying ceremony at the Arch. Many Irish veterans attended, as did military representatives from Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Major-General David O’Morchoe was also present, representing the British Legion in Ireland.

I greatly enjoyed sharing the story of the Irish in the American Civil War in a forum of remembrance. I hope it is the first of many opportunities we have to remember the Irish of the conflict in such a setting. The United States was represented by Military Attaché to Ireland Lieutenant-Colonel Sean Cosden, who laid a wreath in memory of all those Irish who have died in the service of America, including those who lost their lives during the Civil War. Enormous credit is due to Mick Haslam and his team for the continued success of this remembrance event. Sara Nylund took some photos to capture the falvour of the event which are shared with you below.

The first time any of my speaking engagements has been announced like this! (Sara Nylund)

Some of the military personnel who attended the dinner and my talk for the Tipperary Remembrance Trust (Sara Nylund)

The Colour-Guard prepare to march through Tipperary town (Sara Nylund)

The military representatives prepare to set off from the Garrison Church to the Remembrance Arch (Sara Nylund)

The procession from the Church through Tipperary to the Remembrance Arch (Sara Nylund)

The Tipperary Remembrance Arch (Sara Nylund)

Major-General David Nial Creagh O’Morchoe lays a wreath on behalf of the Royal British Legion of Ireland (Sara Nylund)

Squadron Leader Susie Barns lays a wreath on behalf of New Zealand (Sara Nylund)

Colonel Sean English lays a wreath on behalf of the United Kingdom (Sara Nylund)

Lieutenant-Colonel Jean Trudel lays a wreath on behalf of the Canadian Defence Forces (Sara Nylund)

A wreath is laid on behalf of the Irish Defence Forces (Sara Nylund)

Group Captain Peter Wood lays a wreath on behalf of the Australian Defence Forces (Sara Nylund)

Lieutenant-Colonel Sean Cosden, US Military Attaché at the Tipperary Remembrance Arch (Sara Nylund)

Lieutenant-Colonel Sean Cosden lays a wreath on behalf of the United States Armed Forces (Sara Nylund)

‘The Last Post’ is played at the Tipperary Remembrance Arch (Sara Nylund)

‘Going Home’ is played by a lone piper at the ceremony (Sara Nylund)

Filed under: Commemoration, Events Tagged: Commemorating Irish Soldiers, David O'Morchoe, Irish American Civil War, Lt. Col. Sean Cosden, Mary McAleese, Tipperary Garrison Church, Tipperary Remembrance Trust, US Military Attache

September 28, 2013

The Sorry End of Catherine Mullens: Famine Emigrant, Mother of Veterans

The American Civil War touched the lives of many Famine-era Irish emigrants with tragedy. Although we frequently discuss the impact of the Famine in Ireland, rarely do we explore how hard the lives of those who escaped it via the emigrant ship could be. Life in the United States brought hope for many, but for many thousands of others the Civil War crushed any hopes they had for a better existence. The 1888 National Tribune tells the tale of one Irish woman for whom that seems true. Having left Ireland following the death of her husband, she would lose both her sons to the war, and die homeless and in ‘abject poverty’ at the age of 70.*

A MOTHER OF VETERANS

She Dies in Abject Poverty

Mrs. Catherine Mullens, 70 years old, and one of the original squatters in lower Jersey City, died in the street Nov. 21. She came from Ireland in 1852 with two grown sons, who were both killed in the first battle of Bull Run. Mrs. Mullens had no money, and was put out of the shanty in which she lived by the owner. She worked and got money enough to buy a few boards and built a hut in the swamp herself, with the assistance of Micky Free, the pedestrian, who had a house on wheels, and whenever the landowner drove him from one part of the dry land above the swamp he would move to another part. Mrs. Mullens lived in the house in the swamp all the time, though sometimes the water would be a foot deep on the floor of the hut. She earned her living by going out washing. She was buried by people for whom she worked. (1)

* I have been able to find much information on the family, perhaps due to the many variants in spelling of the name. Catherine does appear on the 1870 census. I have been unable to confirm if both her sons died at First Bull Run.

(1) The National Tribune

References

The National Tribune, Washington D.C., 29th November 1888. A Mother of Veterans.

Filed under: Women Tagged: First Battle of Bull Run, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Famine Emigrants, Irish in Jersey City, Jersey City, Jersey City History, Lower Jersey City

September 26, 2013

‘So Mote It Be’: A Ramelton, Co. Donegal Mason in the Confederate Army

Surviving the American Civil War was no guarantee of a long and healthy life. Donegal native John Patton had served with distinction throughout the four years of conflict, first with the New Orleans Crescent Rifles and subsequently in the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery. Despite all the hazards he had endured, death came for him at the age of only 33, in 1872. He had been in the United States for a total of fifteen years, but in that time he had become firmly embedded in the New Orleans community. He was also a dedicated member of the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons, a group that accorded him every honour on his death. One of his fellow masons was also a journalist, who penned a heartfelt tribute to his friend in a local newspaper, ending his tribute with the quintessentially masonic phrase ‘So Mote it Be.’

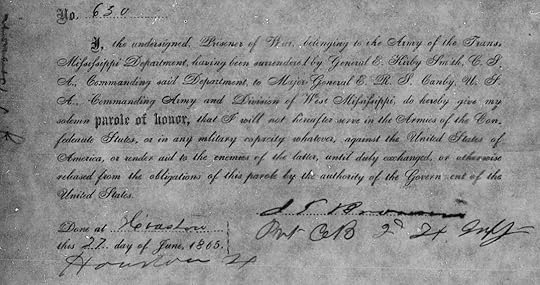

John Patton’s Parole following his capture at Vicksburg in 1863 (Fold3)

Born in Ramelton, Co. Donegal in 1838, John Patton emigrated to New Orleans in 1854 at the age of sixteen. It is probable he was a member of Quitman Lodge No. 76 of the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons prior to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Serving initially in Company A of the New Orleans Crescent Rifles, he joined Company I of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery in Yazoo City on 3rd May 1862, signing on for ‘three years or the war.’ It would appear his service with the Mississippi Light almost ended as soon as it began, as he quickly found himself confined sick in hospital, where he would remain for a number of weeks in the late summer and early autumn. Eventually returning to his command, he and Company I became part of the force tasked with the defence of Vicksburg, the ‘Gibraltar of the Confederacy.’ He fought at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou in late December 1862, helping to defeat the first Federal efforts to gain control of the vital strategic city. During the siege of Vicksburg the following year John played a central role in his company’s activities, particularly after his commanding officer Lieutenant Bowman fell ill. When the city eventually surrendered to Ulysses Grant and the Union on 4th July 1863 John, now a First Sergeant, became a prisoner for the first time. He gave his parole and was eventually exchanged, and after a period as an Orderly Sergeant at Camp Cahaba in Alabama he rejoined his unit in the defences around Mobile. That August his commanding officer, recognising his organisational capabilities, recommended the Ramelton man for the position of Lieutenant and Adjutant, and he was duly appointed in November, 1864. He still held this position in April 1865, when the he was captured for a second time in what was his final action of the war, the campaign against Fort Blakely in April 1865. He was imprisoned for a time on Ship Island before returning to civilian life, having survived the trials of war. When illness eventually took him in 1872, his friends sought to make sure the Irish immigrant would not be forgotten.

The letter recommending that John Patton be promoted to Adjutant of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, August, 1864 (Fold3)

Here is John Patton’s obituary as it appeared in 1872:

Death of Capt. John Patton. In our last issue the following notice appeared:

DIED

In New Orleans on Friday morning, April 12, 1872, at 11 o’clock, of congestion of the brain, JOHN PATTON, aged 33 years 11 months and 8 days, a native of Ireland, and for the last fifteen years a resident of this city.

It was not our intention to pass with so brief a mention the death of a worthy citizen and personal friend, but the lateness of the hour at which the melancholy intelligence was received precluded, until this issue, our paying to his memory an appropriate tribute.

John Patton is dead. We are not often called upon to chronicle the passing away of so bright and noble a spirit as his. In his life there was a much for young men to emulate, much that added beauty to the world’s life. By his death a chord in the great and many toned lyre of nature has been broken. A bud has blossomed forth, and withered, and gone from among us to shine, let us trust, like a star upon the tree of immortal life. A good citizen in time of war and peace, a true friend, a loving brother, a devoted son, a faithful and affectionate husband has been taken from those he loved, and who loved him.He will meet with them around the family circle on this earth no more forever.

Mr. Patton was an Irishman. He was born in Ramelton, Co. Donegal, on the 4th of May, 1838. Fortune did not smile upon his birth, but careing nothing for her frowns he immigrated when sixteen years of age, in 1854, and at the instance of the lamented John McFarland, who sacrificed his life with unselfish devotion upon the altar of Southern independence, John Patton cast his lot with the people of the South. He had qualities that eminently fitted him to hew his pathway through the rocks of life. He was just and true to all with whom he came in contact, and by his integrity, his independence, his manliness and his sterling business qualities, he soon won in his adopted country the confidence of those who knew him. With hundreds of friends he probably had not a single enemy.

When the tocsin of war resounded throughout the length and breadth of the land, he was among the first to volunteer, and upon the 4th of April, 1861, marched as a private soldier with Company A, New Orleans Crescent Rifles, to the battle fields of Virginia. His term of service having expired, he re-enlisted in the 1st Mississippi Artillery Regiment, with which command he participated in the battle of Chickasaw Bayou and the siege of Vicksburg. Being made prisoner, he was for a time in the Federal military prison on Ship Island. After he was exchanged he participated in the desperate and bloody engagement at Blakely, Alabama, just before the surrender of Mobile, and laid down his arms at the general surrender. For his zealous attachment to the Confederate cause and his known gallantry he was promoted through all the non-commissioned grades; and during the last years of service held the rank of Captain and Adjutant of his regiment. No native son of the South put forth his energies in her defence with more earnestness. None gave his service with less thought of personal sacrifice. In all ages Erin has boasted of the bravery of her children; she has cause to be prouder of none more than him. The war being over, he returned to New Orleans with but little more of this world’s goods than were his when, eleven years before, as an immigrant Irish boy, he placed his foot upon American soil. His native energies had not deserted him, and he soon, by his unsurpassed business qualifications, occupied a position among the merchants of that city of which a much older man might well be proud.

On Friday last, the 12th inst., he closed his eyes in that long sleep that knows no earthly waking, and on the succeeding day his remains were escorted to their final resting place by Quitman Lodge, No. 76, A., F. and A. M. (La.), and interred with all the honors and mystic rites of that most honorable and ancient order, there to remain until the general resurrection of the just. With them may we permitted to say: “The will of God is accomplished. So mote it be.” (1)

An 1865 plan of the dispositions at Fort Blakely, Alabama in April 1865, where John Patton was made a prisoner for the last time (Library of Congress)

(1) John Patton Service Record, The Semi-Weekly Citizen 19th April 1862;

*Sincere thanks to friend of the site Jeff Giambrone for bringing this obituary to my attention and for providing a copy of same.

References & Further Reading

John Patton Civil War Service Record, 1st Mississippi Light Artillery.

The Semi-Weekly Citizen (Jackson) 19th April 1872. Death of Capt. John Patton.

Company I, First Mississippi Light Artillery Marker at the Vicksburg Battlefield

Civil War Trust Battle of Vicksburg Page

Civil War Trust Battle of Fort Blakely Page

Vicksburg National Military Park

Filed under: Donegal, Louisiana, Mississippi Tagged: 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons, Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, Donegal Veterans, Irish American Civil War, New Orleans Crescent Rifles, So Mote It Be, Vicksburg National Military Park

September 20, 2013

John Browne of Ballylanders, Co. Limerick: Confederate Veteran, Mayor of Houston, Texas

On 19th August 1941 John T. Browne died in Houston, Texas, having led a most remarkable life. He had been born in Co. Limerick 96 years before and had become one of Ireland’s many Famine emigrants. In his youth he had seen Sam Houston speak, served in the Confederate Army, and eventually embarked on a political career that saw him become Mayor of Houston- a city he watched grow from a small town into one of the largest cities in the South.

John T. Browne, Ballylanders native, Confederate veteran and Mayor of Houston (Portal to Texas History)

John was born in Ballylanders in east Co. Limerick on 23rd March 1845 to Michael and Winnifred Browne. They emigrated from a ravaged Ireland to the United States in 1851, along with their five children. Upon their arrival the family were almost immediately plunged into crisis, as Michael died shortly after they landed in New Orleans. In 1852 Winnifred decided to move with her children to Texas, where they eventually settled in the town of Houston. The 1860 Census finds the Browne’s living in Ward 4 of the town, with 46-year-old Winnifred as head of the household. By this time there were only three children recorded- 17-year-old Johanna who worked a seamstress, 14-year-old Mary and 15-year-old John, who was working as a clerk. John’s other sister Margaret had left home, while his only brother, Thomas, had died at the age of twelve. Winnifred also appears to have been caring for 6-year-old John Turny and his 3-year-old sister Lissy at this time, both of whom had been born in Ohio. (1)

During the 1850s a priest called Father Gunnard played an integral role in changing John Browne’s life. The priest took the Limerick boy and four others from Houston to the Spann family plantation in Washington County, where they spent a number of years being educated. At the age of fourteen John left the plantation and got his first job, in Madison County, where he worked as an off-bearer in a brickyard. He soon decided to return to Houston where he first became a driver of a baggage wagon, then a messenger at the Commercial and Southwestern Express Company and finally a messenger at the Houston & Texas Central Railroad. He was still in this job when the American Civil War broke out in 1861. (2)

During the war John served in Company B of the 2nd Texas Infantry, but rather than accompany it to the front he was kept in the state on detached duty, apparently because he was the main breadwinner in a fatherless family. Among his main duties during the war were acting as a fireman on the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, the company for which he had been a messenger before hostilities began. Towards the end of the conflict he was moved to join the Confederate forces at Galveston, but was back in Houston by the time he gave his parole on 27th June 1865. In later years John was said to have known Dick Dowling, a fellow Irishman and the hero of the 1863 Battle of Sabine Pass. The Limerick man was proud of his Confederate service, and as the ranks of veterans thinned he received significant attention. In 1939 he was appointed commander for life of the Dick Dowling Camp of United Confederate Veterans, while in 1941 he was made an honourary member of the Robert E. Lee Chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. By the time of his death, the Ballylanders native was one of the oldest surviving veterans of the American Civil War in Texas. (3)

The Parole given by John Browne in Houston at the conclusion of the Civil War (Fold3)

At some point during the 1850s John had taken the opportunity to attend a speech at the Old Kelly House, Houston given by the Father of Texas himself, Sam Houston. It is not clear if this had an influence on his later decision to enter politics, but initially at least he returned to what he knew. After the war John became a messenger once more, this time with the Adams Express Company in Houston. After a stint with the Southern Express Company he moved to the grocery business; his education at the Spann Plantation once again proved invaluable as he acted as a bookkeeper and salesman for H.P. Levy, John Collins and Theodore Keller, entering into a brief partnership with the latter in 1870. At the age of 26 John married Mary Bergin of New Orleans, the daughter of Irish emigrant Michael Bergin. They would go on to have eleven surviving children, but John would outlive all but six of them. (4)

The rise in fortunes that would eventually lead John Browne to political office began in 1872. It was in that year that he went into business with Charles Bollfrass, opening the ‘Browne & Bollfrass’ wholesale and retail grocery store. What started with a fund of $500 in 1872 had risen to an enterprise worth $70,000 by 1895. His first foray into the political arena was in 1887, when he represented Houston’s Fifth Ward on the City Council and chaired the Finance Committee. He had also previously acted as Chairman of the School Board. He impressed in these positions, and was asked to consider himself for candidacy as Mayor. He decided to run, and was elected to office in 1892, defeating his opponent by 3,900 votes to 600. John was re-elected in 1894 and ultimately served as Mayor of Houston between 1892 and 1896; among his achievements were establishing the Houston Fire Department as a paid force. He went on to serve in the Texas House of Representatives for three terms, from 1897-99 and again in 1907. One person who didn’t witness his political success was his mother Winnifred; although she had seen him on the road to success, her death in the mid-1880s deprived her of finding out just how far her son would rise. (5)

John T. Browne finally retired from public life in 1909. Throughout his life he seemed to retain a strong affinity for his Irish roots. He was variously known as ‘The Fighting Irishman’ and ‘Honest John’, and was reportedly a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Knights of Columbus. In his later years he was reported to be the ‘delight of Texas historians’ due to his exceptional memory and his stories that often began with ‘I remember the way Houston looked when…’ He was Houston’s oldest living mayor when he contracted pneumonia and died in 1941. John had seen the town grow from a small settlment into a city that was well on its way to becoming the fourth-largest in the United States. On his death the Limerick man left behind six children, thirty-eight grandchildren and twenty-six great-grandchildren. He is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Houston with his wife of 65 years, Mary. (6)

The Arthur B. Cohn House in Houston. Built in 1905, it incorporated elements of the earlier 19th century Browne family home and was originally built on land owned by Winnifred Browne (Ed Uthman)

(1) Lewis Publishing 1895:384, 1860 US Federal Census; (2) Lewis Publishing 1895:384; (3) Dallas Morning News 20th August 1941, John T. Brown Civil War Service Record, Lewis Publishing 1895:384; (4) Lewis Publishing 1895:384-5; (5) Lewis Publishing 1895:385, Dallas Morning News 20th August 1941, Political Graveyard; (6) Dallas Morning News 20th August 1941, John T. Browne Find A Grave Memorial;

References

Dallas Morning News 20th August 1941. J.T. Browne of Houston is Dead at 96.

US Federal Census 1860.

Confederate Service Record John T. Brown.

The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago 1895. History of Texas Together with a Biographical Sketch of the Cities of Houston and Galveston.

Political Graveyard: Texas State House of Representatives

John T. Browne Find A Grave Memorial

Filed under: Limerick, Texas Tagged: Ballylanders History, Dallas Morning News, Irish American Civil War, John T. Browne, Limerick History, Mayor of Houston, Texas Confederates, Texas Veterans

September 18, 2013

‘Touch Her Off Azy!’: An Incident at Chickamauga with Private ‘Buffalo’ Finnell

Thomas Finnell was a 35 year-old Private in Battery I of the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery at the Battle of Chickamauga. During the heat of the fighting on 20th September, his battery was worked especially hard. The stress and confusion of the occasion led to a humourous incident that would be remembered by ‘Buffalo Tom’s’ comrades for many years to come.

A squad of men from Battery A, 1st Illinois Light Artillery and their gun (Library of Congress)

Tom had been 33 when he enlisted in the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery on 25th November 1861. A 5 feet 6 inch tall farmer with gray eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion, he had made his home in Clintonia, deWitt County, Illinois, where he lived with his wife Alice (34 in 1861) and three daughters Margaret (11), Bridget (3), Catherine (1). Tom and Alice had probably been living in the west since soon after their arrival in America- their eldest daughter, Margaret, had been born in Missouri while the youngest children had both been born in Illinois. (1)

Tom would serve for the duration of the war in the 2nd, re-enlisting as a veteran volunteer in Chattanooga on 1st January 1864 before mustering out with the regiment in Springfield, Illinois on 14th June 1865. During his time in the army he was all over the South, fighting at engagements such as Island No.10, Corinth, Perryville and Chickamauga, as well as through the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea and the Carolinas, ending at Bentonville. Throughout the Irishman developed a talent for his ability to seek out whiskey, and also for his use of his ‘favorite expression’ when in action. His comrade W.G. Putney, a former bugler in Battery I, remembered Tom’s participation in the Chickamauga fighting fondly over 20 years later:

Buffalo Tom, an Irishman, whose sense of smell for old rye [whiskey], and whose instinct for finding it under most adverse circumstances was never known to fail, was No. 5 on the gun, it being his duty to carry ammunition from No. 6 at the limber to No. 2, who put it in the muzzle of the gun. In the confusion and excitement of battle he did not notice the gun had been fired twice while he ran for more cartridges. So when he came with the third he did not want to let No. 2 have the charge, because he feared No. 2 had put in two loads that were in the gun yet. After some discussion, Tom gave the last charge to him, but immediately ran off to one side, and, hugging the ground as close as he could, turns to No. 4 and hallowed, using his favorite expression under excitement, “Kristgud! boy! Touch her off azy, or she”ll boorst.” (2)

The long remembered incident (and Tom’s frequent use of the word ‘Kristgud’ in action) clearly stayed with the men of Battery L as a memory of their service long after the war. It also offers us a rare opportunity to glimpse an event in the service of an ordinary Irishman during the conflict, of which there were thousands at Chickamauga. Peter Cozzens, who first identified and sourced this story, suspects that the event may have taken place a few hundred yards from the McDonald House on the battlefield, as the 2nd Illinois Light were engaged late on the 20th September in stemming the Confederate tide. Unfortunately, we are left with no indication as to how Tom, clearly a colourful character, acquired the nickname ‘Buffalo.’ (3)

(1) Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls, 1860 US Federal Census; (2) Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls, National Tribune 24th September 1885; (3) Cozzens 1996: 490;

References & Further Reading

The National Tribune 24th September 1885. Chickamauga. The Bugler of the 2d. Ill. Light Artillery Has His Say.

1860 US Federal Census

Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls Database

Cozzens, Peter 1196. This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga

Civil War Trust Battle of Chickamauga Page

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

Filed under: Battle of Chickamauga, Illinois Tagged: 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, Battle of Chickamauga, Chickamauga 150th, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Illinois Civil War Muster Roll, Irish American Civil War, Irish Artillery, National Tribune

September 15, 2013

Remembering Chickamauga: Researching the Fate of Six 35th Indiana ‘First Irish’ Soldiers and their Families

On 19th and 20th September, 150 years ago, the Battle of Chickamauga was fought. The titanic clash resulted in a resounding Confederate victory, sending William Starke Rosecrans’ Federal troops reeling back to Chattanooga. One of the Union regiments engaged during the fight was the 35th Indiana Infantry, otherwise known as the ‘First Irish.’ The 35th lost five men killed and 23 wounded during the engagement. On top of this they also lost 37 ‘captured or missing’. I have researched the personal stories of six of these missing men- revealing the fatal shadow that Chickamauga cast long after September 1863. (1)

The Battle of Chickamauga by Kurz and Allison (Wikipedia)

Major John Dufficy led the 35th Indiana Infantry onto the field at Chickamauga. Having been involved in some heavy skirmishing on the 18th September, the morning of the 19th found them facing the enemy across Chickamauga Creek near Lee and Gordon’s Mills. The fight started early, at around 8am, but for the first few hours the Irishmen were not seriously engaged. As the day progressed the positions to their left came under severe pressure, and at around 3pm the 35th were ordered to march at the double-quick in line of battle to support their comrades. They were thrown into a desperate fight around the Viniard Farm as they attempted to stem a determined Confederate assault. During the action the first of our six men, Private Thomas Mulcahy of Company A, went down- struck by an enemy bullet. The battle washed over him, and he was taken captive along with many other members of the regiment, particularly men from Company B. For those remaining the struggle continued on into darkness, when the First Irish were instructed to move further to the left, in support of a battery. Their new position exposed them to a vicious crossfire and the men frantically threw up logs and rails in an effort to protect themselves. The position was untenable, and eventually they were forced to withdraw. The long first day’s fight had cost Major Dufficy and the regiment 29 men. (2)

Lee and Gordon’s Mills on the Chickamauga Battlefield. The 35th Indiana began the 19th September located near here (Hal Jespersen)

That night brought little rest. With the Rebels expected to launch another assault the next morning (September 20th), the 35th were once again given orders to move. At 2am they changed position, eventually finding themselves towards the extreme left of the Federal line. Before noon they drove some of the rebels back with a charge through a cornfield, but the tide of battle would quickly turn decisively against the Union troops. To the right a Confederate attack launched by James Longstreet met with complete success, driving large parts of Rosecrans’ army pell mell before them. The left of the army was now isolated and the result of the engagement appeared inevitable. Heavily engaged from around 4pm onwards, the 35th Indiana and those around them were eventually ordered to retreat. With Confederates closing in from seemingly every direction, the withdrawal was in danger of descending into a rout. Eventually the regiment got away, and having initially reformed on a nearby hill they followed the general retreat of the army back to Chattanooga. The two days of fighting finally drew to a close. Many of the 35th Indiana now found themselves prisoners, the majority taken on the first day of fighting. Among this number were Sergeant Michael O’Gara, Private Martin Ryan, Private John Sharkey and Private Luke Dignan of Company B and Private Nicholas Mungin of Company D. (2)

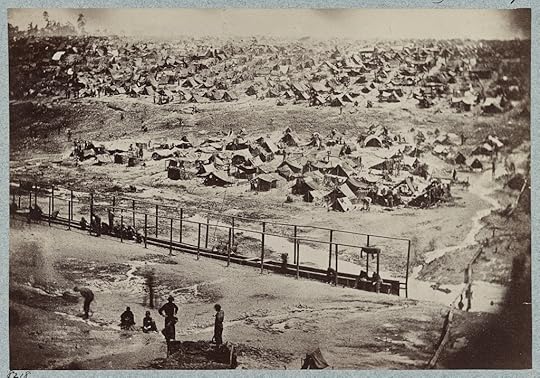

Apart from being members of the 35th Indiana Infantry, these six men had something else in common- all would eventually find themselves prisoners at Andersonville, Georgia, the most notorious POW camp of the Civil War. In its 14 months as an operational prison, 13,000 of the 45,000 men who were held there died- the majority as a result of disease, starvation and exposure. (3)

Martin Ryan had plenty of incentive to try to survive the horrors of Andersonville and return home to Indiana. He had married his sweetheart Eleanor in April of 1861, spending only a few months with her before enlisting in the army. Unable to write himself, he had relied on his friend and mess mate in Company B, John Sharkey, to write home to his wife and his parents on his behalf. Clearly many evenings had been spent around the fire as Martin dictated his feelings to John, who recorded them for his family. Now the two friends were prisoners together in the hellish Georgian stockade. Eventually John was paroled, and in November 1864 sent the following letter to Indiana from Annapolis, Maryland:

Annapolis, Md, November 4, 1864

Mr. Ryan,

Dear Sir I take the privilege of writing these few lines to you by the request of your son Martin the last time I seen him which was the 15th of May last. Sir Martin was my mess mate ever since we have been in the Army and I wrote all his letters for him. Well Sir he entrusted all of his business to me and when he took sick he told me to do this. He took sick about the first of April and he died the 28th of May. I shall come and see you as quick as possible and let you know the particulars of his death.

No more at present,

From a friend of your son,

John Sharkey,

Co. B 35 Ind.

[P.S.] Mr Ryan I am sorry to have to write with such sad news to you and especialy [sic] his wife for I have wrote many a welcome letter to her from him.

Letter written to the father of Martin Ryan by John Sharkey from the Parole Camp in Annapolis, Maryland (Fold3)

John Sharkey had served throughout the war under an alias- his real name was actually John W. Barnes. Aside from the 35th Indiana he had also been in the ranks of the 23rd Illinois Infantry- ‘Mulligan’s Irish Brigade’- and saw later service in the 5th US Infantry. He would outlive his friend Martin by almost 60 years. He passed away in a Soldier’s Home in Illinois on 11th February 1923. (4)

Despite the bullet-wound he had received on 19th September, Thomas Mulcahy managed to survive and at least partially recover. Thomas’s mother Margaret was relying on him- his father had died in Ireland before they had emigrated, and the 67-year-old needed his financial support to get by. Having got through the immediate danger of his wound, Thomas needed the right conditions to rehabilitate. He did not find them at Andersonville. Probably weakened by the injury, he died on 24th July 1864 as a result of chronic diarrhoea. (5)

The capture of Nicholas Mungin at Chickamauga was a disaster for his family, both emotionally and financially. Nicholas lived in Louisville, Kentucky, where since the age of 13 he had found work where he could, usually as a cook on the steam boats plying the Ohio River, or doing odd jobs on the wharf. He had little choice but to work from a young age, as his father had died in 1851, leaving him to support his elderly mother Barbara. They lived in a ‘miserable frame house, illy furnished, and otherwise surrounded by signs of poverty.’ Of his two younger brothers, the elder, Charles was described variously as ‘not of sound mind’ ‘partially idiotic and in very poor health’ and an ‘idiot boy’ who needed constant care. The weight of financial responsibility on Nicholas was clearly huge. In 1861 Nicholas, now 19, had found that the war made work on the Ohio almost impossible to come by. In order to find money he travelled to the Indiana side of the river 60 or 70 miles below Louisville, where he got work on a farm. Not long afterwards he enlisted in the 35th Indiana, undoubtedly seeking a regular wage to help support his family. He consistently sent his pay home, but this stopped after Chickamauga. Nicholas Mungin’s battle to survive Andersonville ended on 27th September 1864- his death as a result of scurvy dooming his mother and younger siblings to a continued struggle with financial penury. (6)

Andersonville POW Camp as it appeared on 17th August 1864 (Library of Congress)

As with Martin Ryan, Company B’s Luke Dignan also had a wife at home- he had been 23 and Ellen 20 when they tied the knot in 1855. They lived in Terre Haute, Indiana, and Luke was to meet many men from that area during his time in Andersonville. One of them was Martin Hogan of the 1st Indiana Cavalry. Hogan had been captured in March 1864 at Stevensville, Virginia during the Dahlgren Raid. In Andersonville the horse-solder served as a hospital steward and got to know Luke Dignan well. Hogan would eventually escape Confederate captivity and return to Indiana. He brought with him a list that he had kept in the camp, which recorded the names of all those who he had witnessed dying. Among the names on it was Luke Dignan, who had died on 6th October 1864 of Dropsy, over a year after his initial capture at Chickamauga. Luke’s wife would follow him into an early grave. She died at the age of just 36 in Providence Hospital, leaving behind no children. She left the remnants of her and Luke’s estate to her brothers children, the Catholic Church, and Providence Hospital which had cared for her. (7)

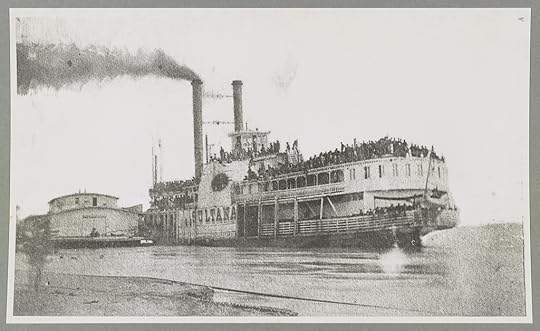

Andersonville was proving far more deadly to the 35th Indiana than the battle of Chickamauga ever was. Of the six men captured on 19th and 20th September 1863 examined in this post, four of them died there. Apart from John Sharkey the only other to survive was Michael O’Gara, also of Company B. Michael had originally lived in New York, where he married his wife Ann in 1846. They had travelled west to make a better life for themselves, until the Civil War intervened. It is likely that on the morning of 20th September 1863 at Chickamauga Michael’s thoughts turned to home, as the second day of fighting was also his eldest daughter Elizabeth’s tenth birthday. His second daughter Honora (Hannah) had been born on Christmas Day 1856. Despite being one of the older men in the group, Michael was clearly a survivor. Having survived all the war had thrown at him, he must have looked forward to a reunion with his wife and daughters as he boarded the steamer at Vicksburg in April 1865 which would take him to Cairo, Illinois and ultimately his Indiana home. He was one of about 2,300 men, mainly former POWs, crowded aboard the vessel as it made its way up the Mississippi on 24th April. They docked at Memphis on the 26th to take on coal and continued their journey up river around midnight. Then, at 2am on the morning of the 27th April, a repaired boiler on the vessel, the SS Sultana, exploded. The blast set off explosions in two other boilers and a combination of fire and boiling steam swept through the stricken ship. Men were catapulted into the river with tremendous force while others were crushed by the falling smokestacks. Hundreds were trapped below decks, while many of those who jumped into the water had sustained horrific burns. Of the c. 2,700 passengers on board, 1,700 died. Up to 200 more later succumbed to their injuries. The explosion of the SS Sultana remains the worst maritime disaster in United States history. One of those who survived was Stephen M. Gaston of the 9th Indiana Cavalry. He later told Michael O’Gara’s family all he knew:

I was a private in Co. K. 9th Ind. Cav. and was on board the Steamer Sultana, on the Mississippi river, Apl. 27. 1865, when said boat blew up, and was burned. I knew well Michael O’Gara, of Co. B. 35th Ind. who was also on said boat, and was lost at said time. I saw said O’Gara on the evening previous, Apl. 26, I never saw him afterwards. I have not the shadow of a doubt but that he was drowned at said time. (8)

A photograph of the SS Sultana taken the day before she blew up. It is likely that Michael O’Gara is one of the men in this image (Library of Congress)

Cruel fate ensured that Michael O’Gara survived the horrors of Chickamauga and Andersonville only to be killed while on the final journey home to his family. His wife Ann never remarried. The widow died 41 years after her husband, on 30th June 1905. As we move towards the 150th anniversary of Chickamauga, it is worth remembering those who survived the initial engagement, but whose death was caused by the battle just as surely as if they had been killed on the field. It is also another opportunity for those in Ireland to remember the many hundreds of Irishmen and their families, fighting for both the North and South, whose lives were altered forever by the colossal clash of arms in north-west Georgia in September 1863. (9)

Monument to the 35th Indiana Infantry, ‘First Irish’, Indianapolis, Indiana (Brian Henry)

The six men who are the subject of this post were far from the only men of the 35th Indiana who found themselves in Andersonville as a result of the fighting at Chickamauga. Among the others were:

Company A

Private Henry Adams, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of diarrhea 23rd September 1864, Andersonville.

Private William Lyons, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of scurvy 2nd August 1864, Andersonville.

Company B

Private Henry Beal, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville and Sultana disaster.

Private Michael Callan, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of diarrhea 14th October 1864, Andersonville.

Corporal John Cody, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville.

Sergeant Charles Devlin, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of pneumonia 26th July 1864, Andersonville.

Private John Dugan, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville.

Private Francis Murphy, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of scurvy 31st October 1864, Andersonville.

Private James Murphy, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of scurvy 13th October 1864, Andersonville.

Company D

Private William Combs, captured 20th September 1863, Chickamauga, reported died at Andersonville.

Private Frederick Frakes, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of diarrhea 30th May 1864, Andersonville.

Company E

Private Daniel McCarty, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville.

Company F

Sergeant Edwin Bolin, captured 20th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of diarrhea 17th August 1864, Andersonville.

Private George W. Bolin, captured 20th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville.

Company G

Private William R. Jerard, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, died of anascara 6th August 1864, Andersonville.

Private Jacob G. Mason, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, fate unknown.

Private Michael McGuire, captured 19th September 1863, survived Andersonville and Sultana disaster.

Company I

Private Patrick Kane, captured 19th September 1863, Chickamauga, survived Andersonville. (10)

(1) OR: 177; (2) OR: 843, Cozzens 1996: 206, 209; OR:844; (3) Andersonville National Park Service Website; (4) Martin Ryan Widow’s Pension File, John Sharkey Pension Index Card; (5) Thomas Mulcahy Widow’s Pension File; (6) Nicholas Mungin Widow’s Pension File; (7) Luke Dignan Widow’s Pension File; (8) Remembering Sultana, Michael O’Gara Widow’s Pension File; (9) Michael O’Gara Widow’s Pension File; (10) Civil War Prisoners

References & Further Reading

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 30 (Part 1). Return of the Casualties in the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, at the Battle of Chickamauga, Ga., September 19 and 20, 1863

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 30 (Part 1). Report of Maj. John P. Dufficy, Thirty-fifth Indiana Infantry

Luke Dignan Widow’s Pension File WC81790

Thomas Mulcahy Widow’s Pension File WC85796

Nicholas Mungin Widow’s Pension File WC88294

Michael O’Gara Widow’s Pension File WC92746

Martin Ryan Widow’s Pension File WC70303

John Sharkey Pension Index Card Application 182286

Cozzens, Peter 1996. This Terrible Sound: The Battle of Chickamauga

National Geographic: Remembering Sultana

Civil War Trust Battle of Chickamauga Page

Andersonville National Historic Site

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

Filed under: Battle of Chickamauga, Women Tagged: 35th Indiana First Irish, Andersonville Irish, Battle of Chickamauga, Chickamauga 150th, Civil War Memory, Irish American Civil War, Sultana Disaster, Widow's Pension Files

September 12, 2013

‘I Have Heard No News From Him’: Catherine Mullen’s Search for her Husband

For women whose husbands went to war, it could often be long months before they heard news of their loved ones. For many the only means they had of gauging the well-being of their men was through the regularity of the letters they received. Of course some soldiers were not good at writing home, while others could not. When letters stopped, wives and mothers were left to agonize over the reasons why, and to wonder if the worst had happened. Sometimes it took years to find out the answer. Such was the fate of Catherine Walsh.

On 30th July 1857 in Holy Cross Church, Brooklyn, Catherine Walsh married Daniel Mullen. They were both in their early twenties at the time. We know little of their pre-war life and occupation, but what is clear is that when war engulfed the United States Daniel was quick to enlist. At the age of 26 he joined what became Company B of the 47th New York Infantry, signing up on 15th July 1861. (1)

Unlike many New York regiments the path of the 47th, also known as the ‘Washington Grays’, did not lead to the Army of the Potomac. Instead they spent much of their war in South Carolina and Florida. Daniel was with his comrades as they fought at the Battle of Secessionville and took part in siege operations such as those on Morris Island. By 1864 the men of the 47th New York, Daniel included, were veterans. It would not be long until their three-year term would expire, and they could decide whether to go home or continue the fight. It was also around this time that Catherine stopped hearing from her husband. (2)

It is unclear when Catherine first realised something was amiss. She may well have been alerted to the fact that something was wrong by Daniel’s failure to answer her letters. As the months passed, Catherine’s desperation grew. Eventually in late 1864 or early 1865 she decided to write to the commanding officer of Daniel’s company, in the hope that he might be able to shed some light on her husband’s whereabouts. Writing from the regiment’s base in North Carolina on 30th March 1865, Lieutenant Crawford T. Newell responded to Catherine’s pleas for information:

Mrs. Catherine Mullen,

Dear Madam,

Your letter of inquiry in regard to your husband, I received this day. I am sorry to say that all the information in my possession in regard to him is that he was wounded and afterwards taken prisoner during the Battle of Olustee, Florida, fought February 20th 1864, since which time I have heard no news from him. I am truly sorry that I cannot give you further intelligence but we have no means of gaining information of the condition or whereabouts of our captured comrades. A general exchange of prisoners has been declared and I hope you will soon again have the proud satisfaction of welcoming Mr. Mullen home again after the long separation endured. With many well wishes for your further happiness,

I remain Madam sincerely yours,

Lieut. Crawford T. Newell,

Commanding Co. “B”, 47 N.Y.Vols. (3)

Federal troops go into action at the Battle of Olustee, 20th February 1864 (History of the 8th USCT)

Whether Catherine knew Daniel had been captured over a year previously is unknown. Regardless, she was still no closer to finding out if her husband was alive or dead; at least Lieutenant Newell’s letter appeared to offer hope. If his words offered her any solace, they would not last long. Soon after this letter, and most probably after the prisoner exchange had taken place, Catherine learned the truth- Daniel had died in captivity. She was aware of his death by May or June of 1865, some 15 months after his initial capture. We know this as it was at this time that she began preparing documentation to apply for a widow’s pension. Still, she was unable to discover where, when or how Daniel had died- some reports said it had been in the notorious Andersonville POW Camp in Georgia, but there was nothing definitive. Without this information her claim for financial aid went unapproved- a situation that was to drag on for years. (4)

The struggle for information on her husband’s death must have kept fresh the pain and heartache Catherine felt. Finally, in May 1867- over three years after her husband had been captured at Olustee- Catherine got the information she needed. A former comrade of Daniel’s in Company B, Patrick Dougherty, agreed to make a statement about his fate. Patrick appears to have been captured with Daniel at Olustee and knew of the circumstances of his death. On 28th May 1867 he said that:

He was late private in Co. B 47 Reg. N.Y. Vols.- That he was well acquainted with Daniel Mullen of the same Co. and Reg. That he was with said Mullen at the Battle of Olustee, Fla on the 20th day of Feb. 1864. That he was wounded by bullets in the hip, in the leg below the knee and in the shoulder. and was with this [illegible] captured by the Rebels and confined at Jackson, Fla. where the said Mullen died of his wounds two or three days after their capture, and that he has no interest in this claim.

Patrick Dougherty. (5)

It seems more probable that Daniel was confined at Lake City, Florida- this is the location that was ultimately stated as his place of death. The examining board dated his passing to August 1864, which contradicts Patrick Dougherty’s information suggesting he died in late February. Either way, Catherine finally had the information she required, both from an emotional and financial perspective. She was granted a pension of $8 a month from 23rd September 1867, back-dated to August 1864. Over 43 months had elapsed since her husband had been riddled with bullets, mortally wounded and made a prisoner of war. It is probable that the $8 per month was scant consolation for the woman who would never, as Lieutenant Newell had earnestly hoped, be ‘welcoming Mr. Mullen home again.’(6)

(1) Widow’s Pension File, AG Report: 800; (2) New York State Military Museum; (3) Widow’s Pension File; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.; (6) ibid.;

References and Further Reading

Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1893

Daniel Mullen Widow’s Pension File WC100483

New York State Military Museum 47th New York Infantry Page

Civil War Trust Battle of Olustee Page

Olustee Battlefield Historic Site

Filed under: Battle of Olustee, New York Tagged: 47th New York Infantry, Battle of Olustee, Battle of Secessionville, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Brooklyn, Irish in the Union Army, Washington Grays, Widow's Pension Files

September 8, 2013

The Last Union Irish Veterans of the American Civil War

The site has previously looked at Limerick man Jeremiah O’Brien, the last known Irish veteran of the American Civil War who died in 1950. He had served as a Confederate, but many thousands of Irishmen who served the Union also lived into the Twentieth century. I have spent some time looking for candidates for the last Irishmen alive who fought under the star-spangled banner. Here are six such Irishmen who lived into the late 1930s and 1940s. There undoubtedly remain many more to be found.

Michael Broderick, 49th Massachusetts Infantry. Died 29th April 1936, Lenox, Massachusetts.

Michael was born in Ireland on 4th April 1839, emigrating to the United States with his parents John and Mary when he was a year old. He spent his entire life in Lenox, and at age thirteen went to work for the Sears family farm. He spent ten years there before enlisting in the nine-month 49th Massachusetts Infantry on 2nd September 1862. The regiment served in Louisiana before their muster out on 1st September 1863. He married in 1872 and moved into a house on East Street in Lenox, where he spent the remaining 64 years of his life. The last Civil War veteran in Lenox, he was an honorary member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. When he died aged 96 he left behind two brothers, William (86) and James (83) as well as his sons Francis (who lived with him) and Harry, daughter Mrs. James Moccio, seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. (1)

Robert H. Keown, 7th Connecticut Infantry. Died 1st March 1937, Renton, Washington.

Reported as being born in the northern part of Ireland on 13th May 1846, he claimed to have traveled to the United States as a stowaway at the age of fourteen, eventually settling in Connecticut. He enlisted in Company D of the 7th Connecticut Infantry on 13th November 1863. He said that he had been captured at Drewry’s Bluff in 1864, ultimately spending nine months in Andersonville. Released on 11th December 1864 he was honorably discharged on 20th July 1865. He moved to the west coast and Washington State in 1882 where he lived in Renton, before relocating to Canada to work on the Canadian Pacific Railroad. He moved back to Renton in the early 1920s, where he worked as a shoemaker. By 1930 he was living in the Soldier’s Home in Pierce, Washington. His death on 1st March 1937 left three daughters- Mrs. Kate White and Miss Shirley Keown of Renton and Mrs. Florence Tvete of Seattle. (2)

Michael Harlow, US Navy. Died 28th February 1939, North Attleboro, Massachusetts.

Born in southern Ireland in 1844 he emigrated with his mother and siblings to the United States in 1849. The family settled in Providence, Rhode Island, where Michael worked as a laborer before the war. He initially tried to enlist in the 3rd Rhode Island Infantry but was rejected due to his youth. He enlisted in the navy in 1863 and served as a Jack for the remainder of the war. Michael was the last surviving member of the Prentiss M. Whiting post of the Grand Army of the Republic. He died aged 96 in the home of his son, James A. Harlow, at 3 Devlin Avenue, North Attleboro. (3)

Union Veteran Orlando Learned shows a flag he obtained at Vicksburg to his Great-Grandson, 1931 (Library of Congress)

Edward Foy, 9th Pennsylvania Infantry?. Died 1939, Portland, Oregon.

Born in Galway in 1846, Edward William Foy went to the United States in 1861. His daughter recounted that he lied about his age to serve in Company G of the 9th Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War (although I have found no record of this, he may have served under an alias). He was naturalized at the age of 21 and after spending a number of years in Iowa he moved to Portland, Oregon in 1910. When he became a US citizen at 21 Edward also became a mason, remaining in the society for the next 74 years. He belonged to Doric lodge No.132 in Portland. Interestingly on 12th April 1939 his lodge held a special gathering attended by Grand Master Franklin C. Howell to honor Foy, who it was claimed was the oldest mason in the United States. Edward Foy died in a veteran’s home in Oregon in 1939. In 1948 his daughter, Miss Nettie Leona Foy, donated two flags to the Rainbow Division veterans of Oregon, Chapter No.1, in memory of her father. (4)

Michael Hearn, US Navy. Died 28th May 1940, Cleveland, Ohio.

Michael Hearn was born in Co. Wexford around 1847 and emigrated to the United States with his family at the age of three. His family settled in Cleveland’s West Side, where he was living at the outbreak of the American Civil War. He traveled to Buffalo to enlist in the Union navy. His family claimed he served aboard the USS Osage, which sank having struck a mine during the Battle of Spanish Fort near Mobile, Alabama on 29th March 1865. Reportedly wounded during the engagement, he was initially reported missing but survived to muster out at Chicago in 1865. Returning to Cleveland he became a shipbuilder, a trade he continued until his retirement in 1923. His wife Mary Walsh predeceased him in 1927. He was 92 years old when he suffered sun stroke while sitting on his front porch at 1418 West 48th Street in Cleveland in May 1940. He died two weeks later, just a week short of his 93rd birthday. Seven of his 12 children survived him- John Hearn, Mrs. E.L. Sherer, Mrs. Loretta Henzey, Mrs. Irene Christner, Mattie Hearn, Mary Hearn and Margaret Hearn. He left 23 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren. He was one of only three remaining members of the Memorial Post of the Grand Army of the Republic at the time of his death, and was the last Union sailor thought to be then alive in the Greater Cleveland area. (5)

John R. Sears, 1st Connecticut Cavalry, 11th Connecticut Infantry. Died 26th July 1941, Greenfield, Massachusetts.

John was born in Ireland on 15th August 1843 and emigrated to the United States with his parents Robert and Elizabeth when he was three years old. The family first settled in Lowell and then Concord, New Hampshire, before moving to Brattleboro, Vermont. At the outbreak of the war Sears enlisted in the 1st Connecticut Cavalry but his parents interceded with the Governor of Vermont to have him discharged due to his young age. He subsequently joined Company E of the 11th Vermont Infantry, fighting through the Overland, Shenandoah and Petersburg campaigns. He was wounded at Spotsylvania. Still only 22 when the war concluded, he married Elizabeth H. Cosgriff and worked as a coal dealer in Greenfield, Massachusetts. The trade he finally settled on was that of a stonemason, an occupation he followed until his retirement in 1923. He was active in the Grand Army of the Republic, and was the last commander of the Day post. In addition he had also been a member of the Greenfield lodge of Elks, Galvin Council, Knights of Columbus, an honorary member of the Galvin post of the American Legion, the United Spanish War Veterans and the Moulton Camp of the Sons of Union Veterans. He died having contracted pneumonia at his home on 26 Beech Street, Greenfield. He was survived by his daughters Miss Anne Sears (with whom he lived) and Mrs. David Corcoran of Belmont, as well as eleven granddaughters, six great-grandsons and numerous nieces and nephews. (6)

(1) Springfield Republican 1936, Pension Index Card, Adjutant General: 484; (2) Seattle Daily Times, Pension Index Card, 1930 US Census; (3) Boston Herald, 1860 US Census, 1930 US Census, Navy Survivor’s Certificate; (4) Oregonian 1948, Oregonian 1939; (5) Plain Dealer; (6) Springfield Republican 1941, Pension Index Card;

References

Adjutant General, 1932. Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War, Vol. 4

Boston Herald 1st March 1939. Michael Harlow Dies in North Attleboro