Damian Shiels's Blog, page 46

May 25, 2014

Memorial Day: The Irish-American Dead of Cold Harbor National Cemetery

During my recent trip to the United States I visited a number of National Cemeteries, including Glendale, Fredericksburg, Antietam, Cold Harbor and Arlington. Many of the headstones in these cemeteries stand as testament to the extent of Irish and Irish-American involvement in the American Civil War. In each cemetery I photographed many graves where ‘Irish’ surnames were in evidence- a random sample based upon where I wandered. The numbers were staggering. Worse still these are only the small percentage lucky enough to be identified. Although we have largely forgotten these men in Ireland, thankfully they are well-remembered in the United States. To mark Memorial Day weekend in America, I am sharing the images from one of the smaller cemeteries- Cold Harbor. Behind every headstone lies a personal story- behind every cemetery an army of friends and relatives who mourned these men’s loss. Behind some is undoubtedly the tragic end to what many emigrants hoped would be a better life than the one they had left in Ireland.

I have not researched these men beyond their entries on Find A Grave, but if you have information on any of them please do share it in the comments section.

Filed under: Memory Tagged: 69th Pennsylvania Infantry, Battle of Cold Harbor, Cold Harbor National Cemetery, Cold Harbor National Military Park, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Irish American Civil War, Irish-American Soldiers, Memorial Day

May 21, 2014

Timothy O’Sullivan Captures an Image to ‘Live in History’, 150 Years Ago Today

150 years ago today Irish photographer Timothy O’Sullivan struggled up the stairs of Massaponax Church, Virginia with his equipment. Time was of the essence as he sought to capitalise on a fantastic opportunity to expose what he must have hoped would be an image to remember. As it transpired, the series of photographs he created that day remain well known to all with an interest in the Civil War. Union Generals Ulysses Grant and George Meade were frozen in time, sitting on pews outside the Church as they consulted with their staff, while Union troops continued their relentless advance in the background. The occasion allowed O’Sullivan to move beyond the carefully posed images we most often associate with these men, capturing a very real moment at a critical juncture in the campaign. His achievement was instantly recognised- within weeks O’Sullivan’s images were being described as depictions that would ‘live in history.’ I took the opportunity during my recent trip to Virginia to visit the site where these very special photographs were created.

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park Historian Eric Mink has carried out some excellent research on these images, most interestingly identifying a later Medal of Honor recipient from the 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry who can be seen in the background of one of the scenes. You can read his post on the Mysteries & Conundrums blog here. During his research he came across an account of the moment when the photographs were taken, which appeared in The Huntingdon Globe (Pennsylvania) on 29th June 1864:

‘Under the shade of some noble trees in front of Massaponax church, I was permitted to look upon a number of our generals in council, consulting some maps of the region through which we were moving. A crowd of curious eyes gathered around to look upon the noted faces for a moment, while from the gallery windows of the church I observed a photographic instrument seizing the rare chance.’ (to read the full quote visit the Mysteries & Conundrums post linked above). (1)

The images captured by O’Sullivan were quickly reproduced as engravings and magazines, and as Professor Brooks Simpson highlights in his post on the topic (which you can read here), has more recently inspired a recreation using model soldiers! One of the earliest examples of the images being reproduced I have come across are as a sketch on the front page of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper for 16th July 1864- less than a month after the photographs were exposed. Even so soon after they were captured, their special nature was recognised. Leslie’s described just how they felt about them:

GEN. GRANT IN A COUNCIL OF WAR

At Massaponax Church.

There have been few mere groupings in the illustrations of the present war. The public calls for action, and our battle scenes cannot be painted in the stereotyped fashion of European art, where a group of mounted officers, glass in hand, overlook, from a rising ground, the work of death below. Even Meissonier, free by his reputation to carve out a new path, durst not depart from the old idea in his Battle of Solferino.

Our illustrated papers have opened a new path, and its influence is felt in Europe. It has been remarked, and justly, that the recent illustrations in the foreign papers of the Danish war resemble our American battles. The scenery is given truthfully, the moving masses of men, the steady progress of the shot and shell of the great guns, with the cloud of the volleys of small arms, the rising dust, all are now given. Formerly a few officers made a battle, now we see armies contending, and recognise the spot.

Yet, perhaps, we overdo this. The sketch which we give of Gen. Grant at Massaponax Church deserves to live in history. Spottsylvania had been left and the Mattapony crossed. At Massaponax Church Gen. Grant stopped with his staff and Gen. Meade did the same. Warren came up with his staff, and under the trees, on the church benches, a council of war was held. The fine spirited grouping of men, who 100 years hence will be the heroes of American enthusiasm, inspired the photographer, and his success in producing a fine picture cannot be denied. At the foot of the two trees sat Grant, and beside him the more towering form of Meade. Rawlins lies studying the map on the right, and Warren, who was the last comer, seems similarly engaged. On the bench to the left Burnside will easily be detected, and on the bench to the right we cannot guess far astray in placing Sheridan and Pleasanton. How many a deed of fame, how many a battlefield won with glory come up to the mind as we gaze on these men! Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Newberne, South Mountain, Antietam, with the varied scenes of two months’ battle still going on, come to our lips and minds. In these careless hats, these scare military dresses, devoid of all but the faintest show of rank, are the true heroes of a republic. (2)

Although the writer appears to have overestimated the number of Generals in the picture, it is nonetheless apparent just how unusual and special an image they considered it. They are undoubtedly special. Even though General Grant was unquestionably aware that O’Sullivan was exposing images of the event, he and his men appear to carry on with their routine in a fashion unusual in Civil war images. This allows to view these photographs as a rare insight into this ‘real’ moment in time. Timothy O’Sullivan left us with a series of pictures that continue to fascinate, even 150 years later.

Massaponax Church, Virginia, surrounded by soldiers (Library of Congress)

A similar view of Massaponax Church today (Damian Shiels)

Grant leans over Meade as they consult a map at Massaponax (Library of Congress)

The area in the foreground is the approximate location of Grant, Meade and his staff when they were photographed in 1864. Timothy O’Sullivan was positioned in the upper part of the church looking down (Damian Shiels)

Grant now sitting on the bench under at the base of the trees (at the left of the bench from the viewer’s perspective) as he writes a note (Library of Congress)

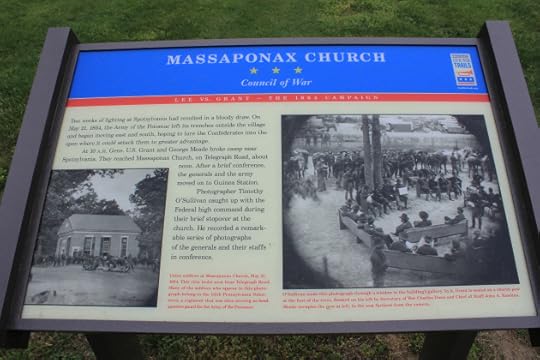

Information panel at Massaponax Church (Damian Shiels)

Grant, now at second from left on the bench, relaxes for a few moments with a cigar. This is the image that was reproduced in Leslie’s (Library of Congress)

The sketch based on Timothy O’Sullivan’s photograph which appeared only a few weeks after it was taken in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News. Note the changes made by the artist. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News)

(1) Mink 2011, The Huntingdon Globe; (2) Simpson 2014, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper;

References & Further Reading

Mink, Eric 2011. Medal of Honor Recipient Caught Straggling on the March. Mysteries & Conundrums.

Simpson, Brooks 2014. May 21 1864, Grant Moves South. Crossroads.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 16th July 1864

The Huntingdon Globe 29th June 1864

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

Filed under: Cork, Virginia Tagged: Civil War Photographs, Civil War Photography, Cork Civil War, George Gordon Meade, Irish American Civil War, Massaponax Church, Timothy O'Sullivan, Ulysses S. Grant

May 2, 2014

150 Years Ago: An Irish Photographer Captures the Overland Campaign

As I head to Virginia to visit some of the sites relating to the start of the 1864 Overland Campaign, I have been looking again at the contemporary photographs captured during that momentous summer. Irishmen were not just present among the fighting men of the two opposing forces, they were also there to document the Union push to neutralize Robert E. Lee’s army. One of the best known was photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, an individual who has been the topic of a previous post and is also featured in my book. Some of O’Sullivan’s images from around May 1864 are among the most famous of any taken at this time; they include his exposures of Confederate dead at the Widow Alsop’s Farm in Spotsylvania, and his remarkable images of Ulysses S. Grant and his officers in the midst of the campaign at Massaponax Church. Here are some of the images credited to Timothy O’Sullivan and taken during that month available through the wonderful online collections of the Library of Congress.

Build up. Vicinity of Brandy Station, Virginia. Large Wagon Park, May 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

The campaign begins. Germanna Ford, Rapidan River, Virginia. Ruins of bridge at Germanna Ford, where the troops under General Grant crossed, May 4, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

The campaign begins. Germanna Ford, Rapidan River, Virginia. Artillery crossing pontoon bridges, May 4, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

The campaign begins. Germanna Ford, Rapidan River, Virginia. Grant’s troops crossing Germanna Ford, May 4, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

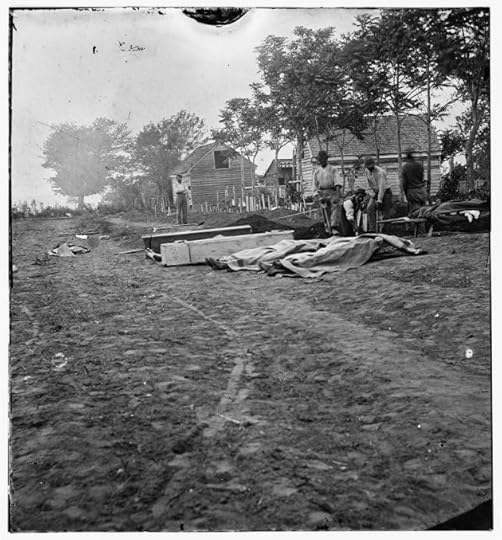

Aftermath of battle. Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. Burial of soldier by Mrs. Alsop’s house, near which Ewell’s Corps attacked the Federal right on May 19, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

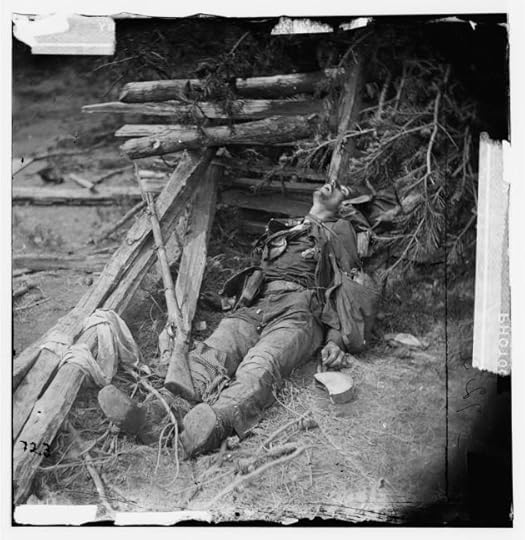

Aftermath of battle. One of Ewell’s Confederate Corps as he lay on the field, after the battle of May 19, 1864, Spotsylvania (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

The campaign continues. Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, vicinity. View from Beverly House looking towards Spotsylvania Court House, May 19, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

The mortally wounded. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Burial of Federal Dead, May 19/20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Aftermath of battle. Dead of Ewell’s Confederate Corps, laid out for burial near Mrs. Alsop’s House, Spotsylvania, May 20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Aftermath of battle. Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. Body of a Confederate soldier near Mrs. Alsop’s house, May 20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Aftermath of battle. Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. Bodies of Confederate soldiers near Mrs. Alsop’s house, May 20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Aftermath of battle. Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. Body of another Confederate soldier near Mrs. Alsop’s house, May 20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. Spotsylvania Court House, vicinity. Beverly House, headquarters of General Gouverneur Warren, 5th Corps, May 20, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. Massaponax Church, Virginia. View of the church, temporary headquarters of General Ulysses S. Grant, surrounded by soldiers, May 21, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. Massaponax Church, Virginia. ‘Council of War’, General Ulysses S. Grant examines a map held by General George Gordon Meade, May 21, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. Massaponax Church, Virginia. ‘Council of War’, General Ulysses S. Grant (left end of bench nearest tree) writing a dispatch, May 21, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. North Anna River, Virginia. Quarles Mill on North Anna where a portion of the 5th Corps under General Warren crossed, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. North Anna River, Virginia. Pontoon bridges constructed by the 50th New York Volunteer Engineers. Where a portion of the 2nd Corps under General Hancock crossed, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. North Anna River, Virginia. Pontoon bridges across the North Anna, below railroad bridge, where a portion of the 2nd Corps under General Hancock crossed, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. Bethel Church, Virginia. View of the church, temporary headquarters of General Ambrose E. Burnside, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Enemy Fortifications. North Anna River, Virginia. Interior view of a Confederate redoubt commanding Chesterfield Bridge. Captured by the 2nd Corps under General Hancock, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. North Anna River, Virginia. Chesterfield Bridge with Confederate redoubt in the distance, carried by the 2nd Corps under General Hancock, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Chesterfield Bridge, North Anna River, Virginia, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Jericho Mills, Virginia. Canvas pontoon bridge across the North Anna, constructed by the 50th New York Engineers; the 5th Corps under General Gouverneur K. Warren crossed here on the 23rd. View from north bank, May 23, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Jericho Mills, Virginia. Looking up the North Anna river from the south bank, with a canvas pontoon bridge and pontoon train on the opposite bank, May 24, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Jericho Mills, Virginia. 5th Corps ammunition train crossing North Anna River, on canvas pontoon bridge constructed by 50th New York Volunteer Engineers May 24, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

A Vital Support. Jericho Mills, Virginia. Party of the 50th New York Engineers building a road on the south bank of the North Anna, with a general headquarters wagon train crossing the pontoon bridge, May 24, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Dug In. North Anna River, Virginia. Federal troops occupying a line of breastworks on the north bank, May 25, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Hindering the Advance. North Anna River, Virginia. Destroyed bridge of the Richmond and Fredericksburg Railroad, May 25, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. North Anna River, Virginia. Cavalry crossing Chesterfield Bridge, May 25, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Taking a Break. Soldiers bathing, North Anna River, Virginia. Ruins of railroad bridge in background, May 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Vital Support. North Anna River, Virginia. Grant’s engineers building a bridge, May 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

High Command. North Anna River, Virginia. View of log bridge at Quarles Mill from south side. Camp of general headquarters in the distance, May 26, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Hanovertown Ferry, Virginia. Canvas pontoon bridges at Hanovertown Ferry, constructed by the 50th New York Volunteer Engineers, May 28, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Fording the Rivers. Hanovertown Ferry, Virginia. Pontoon bridges across the Pamunkey, with wagons, May 28, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Impediment to the Advance. Mrs. Nelson’s Crossing, Virginia. Ruins of the Richmond and York River Railroad bridge across the Pamunkey, above White House, May 28, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

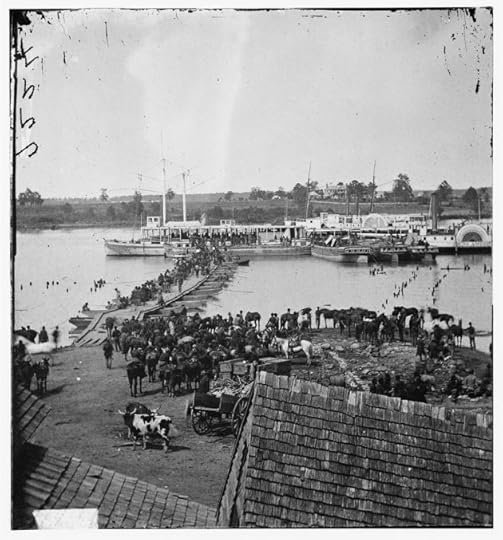

Change of Base. Port Royal, Virginia. The Rappahannock River front during the evacuation, May 30, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

Change of Base. Port Royal, Virginia. Transports being loaded from a pontoon bridge during the evacuation, May 30, 1864 (Timothy O’Sullivan/ Library of Congress)

References & Further Reading

Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog: Civil War

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

Civil War Trust: The Overland Campaign of 1864

Filed under: Battle of North Anna, Battle of Spotsylvania, Battle of The Wilderness, Cork, Virginia Tagged: Battle of North Anna, Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Battle of the Wilderness, Irish American Civil War, Overland 150th, Robert E. Lee, Timothy O'Sullivan, Ulysses S. Grant

April 30, 2014

Heading Overseas to Remember the Overland

On Saturday I will be heading to the U.S. for two weeks, so in that period things may be a bit quiet on the blog. For much of the trip I will be based in Fredericksburg as I attend the 150th commemorations at The Wilderness and Spotsylvania battlefields. Despite the time I have spent working on the Irish experience of the American Civil War, this trip represents my first opportunity to visit some of the conflict’s battlefields. I am greatly looking forward to participating in some of the NPS events, particularly the walking tours. Having spent a lot of time with American Civil War pension files of late, it is striking just how often Irish deaths in combat occurred during the carnage of 1864′s summer. The horrendous experience of the 9th Massachusetts over just a few minutes in Saunder’s Field on 5th May 1864 is one of the stories I concentrate on in my book, and I now have a privileged opportunity to stand on the same ground 150 years later. This will be just one of what I hope will be a number of highlights of my time in America, during which I hope to amass significant blog post material!

Apart from The Wilderness and Spotsylvania I will also be visiting (at a minimum) the Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Antietam and Seven Days battlefields, as well as spending some time in Willliamsburg, Jamestown, Harper’s Ferry and Washington D.C. If any of you are attending any of the events, and happen across an out-of-place Irishman, be sure to come and say hello! The National Park Service have produced an excellent booklet on their 150th Overland events which you can view here and you can check out the Spotsylvania, Virginia- Crossroads of the Civil War events here.

Filed under: Update Tagged: American Civil War 150th, Battle of Spotsylvania, Battle of the Wilderness, Colonial Willliamsburg, Fredericksburg, Historic Jamestown, Irish American Civil War, Sesquicentennial

April 23, 2014

‘I Feel Very Lonely and Downhearted’: Isolation, Idealism and Kindred in the Letters of an Irish Emigrant

Widow’s Pension Files are among the most remarkable records that survive relating to the American Civil War. Filled with fascinating social information, they often also contain primary sources from 1861-1865- such as wartime letters- that have lain unread for over a century. Many thousands of these files relate to Irish people, and contain important details about life in Ireland and among Irish emigrants in the middle of the 19th century. The importance of these files as a historic resource remains unrecognised in Ireland, which is unfortunate given that many Irish records from this period were destroyed during the Irish Civil War. The letters below relate to one such remarkable pension record. Contained within Navy Dependent File 2867 are three poignant letters from Second Class Fireman Patrick Finan of Sligo town, written to his father from the decks of USS Wabash. Transcribed here for the first time, they have much to teach us about emigration, community, life on the Union blockade, loss and loneliness. They are well worth taking the time to read.

A sketch of the USS Wabash on which Patrick Finan served during the American Civil War (Library of Congress)

Patrick Finan first enlisted in the Union Navy in New York on 29th April 1861, signing on as a Coal Heaver. His place of birth was incorrectly inputted as Brooklyn. He was 23-years-old and was recorded as having no profession. Patrick was 5 feet 6 1/2 inches tall with blue eyes, light hair and a light complexion. This is his physical description- to gain an insight into his character and emotions, read on. (1)

Hilton Head, Port Royal S.C.

October the 23th [sic.], 1862

Dear Father,

I take the liberty of writing these few lines to you hoping to find you brother and sister in good health as this leaves me in at present thanks be to God for it.

Dear Father you must excuse me for not answering your letter sooner than this but I was waiting for the ship to go to New York until I would send you all particulars, but when the time came to go home I was disappointed, for in place of going to New York we were sent to Philadelphia and we received one weeks liberty on shore. I was thinking of going to New York from there but I changed my mind for I thought I might as well spend my time there as in New York. So you may think what a week I spent after being fifteen months at sea but I got sick of it at the latter end and I was glad to get on board the ship again, but we only remained fifteen days in Philadelphia until we left for Port Royal on the first of August again and to make my liberty better I got sick on the passage out and I had to go into hospital on board the ship for two months before I got better, but I am quite well again and at my duty. Dear Father we expect to make an attack on Charleston very soon for we are to have a fleet of iron clad vessels as soon as our Admiral comes back, for they would sink all the wooden vessels that ever was built but our ship is too large to get in close on the Bar but I hope it is all for the better, for I don’t want to be under the fire of them guns that is on them Forts but our iron clad vessels can stand anything so I think our vessel will have to remain outside the Bar and look on at the sport and I hope we will come out victorious.

Dear Father I have not heard one word from Patt Keen since he came out here or from Bartly Burns or the wife, but I expected Patt Keen would write and let me know how he was getting on but out of sight out of mind with them all, for they knew very well where to write to me, but I hope I will live to return them the compliment they have shown me since I left New York, but a stranger will think more of you here than your one friend. Well Dear Father I received a letter from one of Mrs. Short’s sons that lived in Manchester and he is in the Navy about the same time as myself, his mother and brothers and sisters is living in Fall River where James Tindell was living, and he told me that Michael Flanigan [en]listed in the Irish Brigade under General Francis Magher, eight thousand strong, and he went into the battle that was at Richmond about a month ago and all the men he brought out alive was five hundred, so I suppose Michael Flanigan was killed in that battle.*

Dear Father you must excuse me for not having something to send to you in this letter but you may expect it in the next, I will send to you in January next so try and do the best you can until then, for there is no money to be got in this ship at the present time. Dear Father you will make it your business to see Mr. Coggans and ask him if he has heard anything from his son Michael, for I was told by a prisoner we got on board our ship that come from Charleston and he told me he knew Michael Coggans, and that he got married and shortly after he [en]listed in Charleston and is now stationed in James Island the very place we are going to make an attack on, and give my respects to him and his daughter Margaret.** Dear Father if I remain twelve months more in the navy you may expect me home for a few months as soon as I get paid off, for I never can let home out of my mind I am always thinking of home, I don’t know the reason of it for when I was in England I never used to think half so much of home as I do now, but I am not the same since my Mother died. I feel very lonely and down hearted.

Dear Father you will be kind enough to tell John Gannon not to be uneasy a [small portion of letter missing] Michael has the [small portion of letter missing] present time for they are pressing men to [en]list all over the States but as soon as Rebellion is over we will have a good country here again and I expect this winter will finish it all. Give my love to my brother Michael and wife and child, and my sister Mary Ann, and to Martin Conlin wife and family, and tell little Patt Conlon I will bring him home a suit of Man O’ War clothes and make a regular Jack Tar of him. Give my love to Johnney Mulrouney wife and family and to my [sic.] daughter Anney and Patt Kerins and children and John Mulrouney wife and family, Dan Riley and family and to Mrs Rees? and to Thomas Mulrouney and James Hennesy, and give my love to the two Miss Mullins, father and mother and to all loving friends and neighbours and to my aunt Peggy, and [I] was very near forgetting her. So I bid you all goodbye for the present but I remain your truly son Patrick Finan, until death.

When you receive this letter write by the return of post and let me know how you are getting on and how Michael is doing.*** (2)

The Confederate ironcald ram CSS Chicora. Patrick Finan’s friend from Sligo, Michael Coggins, may have served against him aboard this vessel (Photographic History of the Civil War)

Hilton Head

Port Royal S.C.

January the 25th 1863

Dear Father,

I take the liberty of addressing these few lines to you to inform you that I received your kind and welcome letter on the 20th, and I am happy to hear that you are all in good health as this leaves me in at present thanks be to God for it. Dear Father I am sorry to inform you that it is impossible for me to send you the money home or I should feel very happy in doing so, for the money we get here that it is no use out of the country, for every pound in gold I would get here to send you I would have to pay two dollars discount on it so you see now how much it would take to send as much as would bring you all out here. Dear Father I am willing to pay your three passages in [to] New York, yours Mary Ann and Johnsey Mullrooney if you are willing for me to do so, for I don’t know any other way in bringing you out here at the present time. I have the money on hand these three months and could not get no way of sending it to you. Dear Father when you receive this letter write as much as possible and let me know what you intend to do and tell Johnney Mullroony that if he is willing to come out here I will pay his passage along with yours, that is if his wife is willing to let him come here, but on no other condition. I would like to bring him out here.

Father it grieves me to say that it was the first? in the January? to make a settlement on it, and when you and Mary Ann leaves we will be well divided, and if Michael had taken my advice when I was leaving Liverpool I would have him out here long ago but he has taken his own or else yours and let him abide by it, for I am sure he was time enough to get married these five years to come. Let me know how you stand, that is to say if you have got as much money as will bring you as far as Liverpool, and if not let me know in your letter and the sum you think will do you, and I will send it to you, I don’t care how much I have to pay for sending it for I don’t want you to be in debt to any man leaving Sligo, and for my part I am willing to do all that ever a son can do for you and more perhaps than them you thought more of. But at the same time it is no more than anybody to a Father and all I am waiting for now is the answer of this letter and if you are willing to come that way let me know and I will pay yours, Mary Ann and Johnney Mullrooneys passage as quick as possible. Dear Father I intended to go to Sligo when I got paid off but all my hopes is blasted for the future of ever seeing Sligo again? [portion of letter blotted out] When you come out and I hope your uncle Daniel? [portion of letter blotted out] will be along with you and Mrs. Keen and children [portion of letter blotted out] is one that lies cold in the clay that I would give all the world she was alive to be with you until I would see her face again but alas that day will never come in this world, and may the Lord have mercy on her soul, Amen. [It seems likely that Patrick is here referring to his mother].

Dear Father I have not received a letter from Brooklyn this twelve months, and I can’t say how Bartly Burns and the family is getting along for like all the rest of them that is here he soon forgot me. But I hope I will live to return to New York to pay them back with the same coin, and I was greatly surprised when I herd Thomas Mullroony was married, but I suppose he took a foolish notion like all the rest of the Sligo boys. Let me know what young woman he got married to, Sligo can’t be so bad when the young boys can support wives, and as for this country the widows and girls are going mad for men and can’t get them, for the war has all the young men in the country away and any young man that comes home safe out of the war the young girls will be giving any amount of money to get a man, and plenty of money they have got. [It] is now is the time for the young men of Sligo to come to this country, any of them that is able, for this will be a fine country when this war is over and as it is I hear they can’t get men enough to do the work for them in New York. There is very few men in the citys at all but what is a way in the army and navy. Dear Father there is nothing thought of a man here if he is not either in the army and navy fighting for his country. I have received a few letters from Patt Short since I come in the navy he is living in Fall River and his mother and brother and sisters sends their love to you and they wish to see you out here. Tell Johnney Michael Flanigan is still a prisoner in Richmond.

Dear Father I intend to be in a hot battle very soon, I expected it sooner than this but the weather kept the vessels from coming down here but the most of them arrived here this week, and we expect the rest of them here soon, all iron clads vessels and we expect to make and attack on Charleston, [in] the next month and I hope that will be our last. Dear Father give my love to my sister and brother, [his] wife and child and to my aunt Mary and family and Thomas Mullroony and wife, John Mulrooney and family, Patrick Kearns and family, Patrick Flynn and family, Patt Hughes and family and my Godfather Johnney Mulrooney and family, Michael O’Hara and family, Patrick Feenney and family, Dan Riley and family, Mrs Phur? and children and my aunt Peggy and give my compliments to John Muligan and wife, give my love to James and Patt Kerns and to John and Edward, wife and sister, and all my old comrade boys of Sligo and not forgetting the young girls [portion illegible] and [portion illegible]…Captain Steward and [portion illegible]… old sailors of the Shamrock**** and give my love to Francis? Duffy and Edward Moran, and all inquiring friend and neighbours home at present, but I remain yours truly Patrick Finan and I bid you all goodbye and old Sligo for now and ever more,

Yours Respectfully, Patrick Finan

Send your letter for Patrick Finan U.S. Navy Ship Wabash Port Royal S.C. New York America and send me Mary Ann’s age.*****(3)

The USS Wabash in action at Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina, in 1861. She is the largest vessel, second from the right (Library of Congress)

Port Royal S.C.

June the 24th 1863

Father I take the liberty of writing these few lines to you hoping to find you in good health as this leaves me in at present thanks be to God for it.

Dear Father I received your kind and welcome letter on the 20th and I am very happy to hear that you are enjoying good health and I am also very sorry to hear that Johnney Mulrooney is lying very bad, but I hope he will soon recover his health again and be able to come to see me in the land of liberty. Dear Father I am surprised at you for to sell all your things in such a hurry before you received your passage ticket, for I am sure you would have time enough to sell them after you received the order, and on the other hand you wanted me to pay your passage on a steamer but the passage is too high, it is 32 dollars in gold and 48 dollars in the U.S. currency, so you must know how much it would be to bring you out on a steamer and to send you money home also, for I know you can’t come out without sending you some money home and I think it would be very good on my part to be able to bring you out on a sailing ship, the same way as I come myself, not that I would think it too much to bring you out on a steamer, but for the way times is here at present that if a man wants a dollar in gold he has to pay one dollar and a half before he can get it, and that is what is keeping you in Sligo so long, for I think it very hard to lose so much money for nothing for it is my intention to save all the money I can while I am in the service, that I can be able to start you in business as soon as you come here. Dear Father it would take very near forty pounds to bring you and Mary Ann out at the present time so with the blessing of God remain where you are until the times takes a turn here for the better, and I hope that won’t be long and I think you can’t starve in Sligo as bad as you say it is.

Dear Father I wonder how the young men of Sligo that is coming out here will like to be drafted as soon as they land for they have passed a law here to draft all the young and married men from 25 to 45 years of age after they are thirty days in this country, or else they will have to leave the country again and I am very glad of it for there is a lot of young fellows around New York that won’t fight for their country and they ought to be made fight or else clear out. But I wish to God it was for the freedom of Ireland I was fighting for in the place of what we are fighting for. Dear Father I wrote to Patt Short in Fall River to let me know of the first chance he can see that I can send for you, and I am very much surprised at you for not sending some account of John Gannon in your letter to his brother Michael for he was waiting to hear from him in your letter and he was greatly disappointed when he heard his name was not mentioned, and I felt ashamed myself when you did not send some news about him for I am sure you had plenty of place [space] in your letter. Dear Father I have ten months more to serve before my time is up but that won’t be long passing, we are expecting our ships to go home very soon we are waiting for a ship to relive us and as soon as she comes we start for home. Dear Father you have liberty to do as you wish with the pictures when you get them but be sure and give Mrs. Flynn her pictures and tell her to receive them as a favour from me for her kindness to my mother, but you could not expect to receive them as quick as the letter for there will be a delay on them before you receive them. Dear Father tell Mary Finan I received her brothers likeness last week in a letter and I [am] going to send him my likeness this week. I receive a letter from him every week and he is getting along very well.

Dear Father we are making up a great deal of money in this country for the Poor of Ireland and on board our ships we made up near twelve hundred dollars on board this ship, you can see it in the last two papers I sent you [for more on these fund raising efforts in 1863 see a previous post by clicking here]. And I had to laugh the other day when I read in the papers about Patrick Davey getting eleven sheep killed on him with some of your mad dogs and about Patrick Kearns in Pound Street turning bankrupt, there is not a thing done in Sligo but I hear of it in one of your Irish papers. Dear Father cheer up and make out the best way you can until such times as I can bring you out, I am sure you would not know me if you seen me for my hair is getting grey. I am greatly changed since you last seen me, this is the country to take the blush off your cheeks. Dear Father when you write again you need not put yourself to the expense of paying the postage for I can pay for it here better than you can, let me know in your next letter if you received the pictures all right for I feel uneasy until they go to hand, be sure and let me know how Johnny Mulroony is getting along for I feel uneasy for fear anything would happen to him.

Dear Father give my respects to Patrick Flannery wife and family and tell him I feel very thankful to him for his kindness towards you, give my compliments to Patt Flynn wife and family and to Patt Feeney wife and family and give my love to my sister and brother, [his] wife and child, give my love to my uncle Johnney wife and family and to my aunt Mary and Martin Conlon and family and my aunt Peggey give my respects to John Mulrooney wife and family, Patrick Kearns and family, Dan Riley wife and family and to Mrs Keen and tell her I never heard one word from Patt since he landed, give my love to James Hennesy and James Mulroony and to Bridget Mulroony. Give my respects to Michael O’Hara wife and family and to Patt his wife and family and to my good Father.

No more at present but I remain your most respectfully Patrick Finan. Good Bye.

Direct your letter as before: Mr. Patrick Finan U.S. Flag Ship Wabash Port Royal S.C. America (4)

Photograph of the USS Wabash at Port Royal, South Carolina, taken from the deck of the monitor USS Weehawken in 1863. Patrick Finan would have been aboard the vessel when this image was exposed (U.S. Naval Historical Center)

Just a few months after this letter was written Patrick Finan was dead. On the 21st March 1864 the 27-year-old Sligo man, who was serving as a Second Class Fireman, was examining water-cocks beneath the boilers of the USS Wabash which was still stationed off Port Royal, South Carolina. An accidental discharge of hot water from the boilers caught Patrick and severely scalded him on the body and limbs. During the first days after his horrific injury it seemed like he might pull through, but on the night of 5th April an effusion of the brain occurred, and he died on the night of 6th April. It is because of Patrick’s death that his remarkable letters survive. Years later his now incapacitated father John, who had never made it to a new life in the United States, sought a pension in Sligo based on his son’s service. He had to prove that his son had helped to support him when he was alive, so he included these three letters of Patrick’s as they refer to his son helping him financially. 65-year-old John prepared an affidavit to accompany his claim on 12th May 1880, giving his post office address as West Garden Lane, Sligo, Ireland and outlining his sad circumstances:

I John Finan say I am a working butcher by trade but am now prevented by infirmity and ill health from earning my support by labouring at my trade. I was married in the month of July 1835 to Bridget Mulrooney but the Roman Catholic Register of the Parish of Sligo has been mislaid and I am unable to produce the certificate of my marriage. I say I had 7 children, but all are dead save two, one daughter living in the United States, of whom I have not heard for 5 years last past and one son in Australia, of whom I have not heard for the last 10 years- my son Patrick Finan was my eldest child and he left Ireland about the year 1859, and after residing some years in United States enlisted in the Navy of the United States and died on board the United States ship the Wabash until the year 1864 having been scalded to death by an accidental escape of steam- my said son Patrick Finan previous to his enlisting in said navy constantly remitted to me sums of money for my support, and I received from him in the year previous to his enlisting ten pounds sterling for my support, but in consequence of his being out at sea whilst on board the Wabash he was unable to remit money at regular or fixed times. I refer to his letter marked A dated 23d January 1863 and the letter marked B dated 24th June 1863, stating he had money for me, but was unable to remit same. My said son Patk. Finan whilst he lived afforded me my only means of support and was the only person on whom I could rely for support. From his death to the present time I have had no other means of support, than the sum of £90 the arrears of his pay and a subscription raised for me, which fund is now exhausted and which was remitted to me. I say I am incapacitated from work and am now trusting to the charity of my friends and neighbours for my support. I say my wife Bridget Mulrooney died 21 years ago and I remained since her death unmarried- I say my said son Patrick Finan never married. (5)

John Finan received a pension for the service of his son. The former butcher passed away in West Garden Lane on 20th December 1890- he had married again, as his widow Sarah was recorded as being present at his death. Despite his age being given as 65 in 1880, it was recorded as only 66 in 1890, a differential that is not unusual when dealing with 19th century records. (6)

These letters are extremely revealing regarding emigration and community in 19th century Ireland. It is also of interest to note just how many of the people in Sligo town had family who emigrated; included amongst Patrick’s circle were at least two others who fought in the Civil War, one in the Irish Brigade and one for the Confederacy- the latter of whom, Michael Coggins, seems to have literally been facing his former friend in the battle for Charleston (see notes below). Letters such as these open up a window on the strong ties between Ireland and the United States in the 1860s and the impact of the American Civil War on Irish people. Sources such as these, and the experiences of men such as Patrick Finan, are worthy of considerably more attention and study here in Ireland than they currently receive.

Walsh’s Royal Mail and Day Car, Corcoran’s Mall, Sligo, c. 1885. This scene would have been familiar to John Finan, who was still alive when it was taken (National Library of Ireland)

Notes

*A Michael Flannigan aged 27 years enlisted in the 88th New York Infantry on 3rd March 1862 and was assigned to Company F. He was captured in action at Chancellorsville on 3rd May 1863 and paroled, and transferred to Company A on 12th June 1863. Transferred to the 114th Company of the 1st Battalion, VRC, he was re-transferred to Company A of the 88th New York on 19th February 1864. He re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer on 22nd March 1864 but deserted on 30th May 1864 on the expiration of his veteran furlough. (7)

**Patrick’s information here may be surprisingly accurate. A Michael Coggins served as a Private in Company D of the 3rd Palmetto Battalion, South Carolina Light Artillery. He enlisted aged 23 in Charleston on 14th November 1861. He was sentenced to forfeit two weeks pay by order of court-martial in June 1862 and in July of the same year was listed as absent without leave, sick in the city (Charleston). On 4th October 1862 he was transferred to the Naval service. An ‘M. Coggins’ is recorded as an Ordinary Seaman on the crew of the C.S.S. Chicora for late 1863 and early 1864, and this may be the same man. Chicora was an ironclad ram built in Charleston in 1862- it was volunteers from her crew that became the first to serve on the submarine Hunley.(8)

*** Patrick’s mother was a Mulrooney so it is likely that all those of that name referred to in the letters are family relations.

****It is unclear what vessel the Shamrock was, and if Patrick had served on it in Ireland (it is clear he also spent time in England before his emigration). There were a number of ships of that name operating in 19th century Ireland, more work is required to ascertain if none had particular connections to Sligo.

*****The USS Wabash on which Patrick served for most of the war and on which he died was a steam-screw frigate. She spent most of the Civil War on blockading duty as part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Members of her crew participated in actions against positions such as Fort Pulaski, Georgia and while in Port Royal a detachment of her crew were captured by a Confederate steamer. She took a number of prizes, including the Wonder on 13th May 1863.

Note re Letter Transcription: Patrick Finan’s letters have been transcribed here to make them as readable as possible. The originals contain extremely varied spelling and no paragraph formatting or punctuation (e.g. ‘the’ is frequently used for ‘they’). As an example here is the passage relating to the draft as it appears in Patrick’s hand:

‘…Dear Father I wonder how the young men of Sligo that is coming out hear will like to bee drafted as soone as the land for the have past a law hear to draft all the young and married men from 25 to 45 years of age after the are thurty days in this country or els the will have to lave the country a gine and I am verrey glad of it for thear is a lot of young fellows a round New York that wont fight for thear country and the ought to Bee made fight or els clear out but I wish to God it was for the freedom of Ireland I was fighting for in the place of what we are fighting for…’

The original transcriptions do give more of an impression of Patrick’s Irish accent, with many words spelt phonetically. If you would like to see any of the original transcripts please let me know.

Market Street Sligo c. 1899. Aside from the new 1798 memorial in the foreground this streetscape would probably have been familiar to both Patrick and John Finan (National Library of Ireland)

(1) Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns; (2) Patrick Finan Widow’s Pension File; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid.; (7) New York Adjutant General: 51 (8) Confederate Civil war Service Records, Confederate Muster Rolls of Ships and Stations;

References

Confederate Civil War Service Records.

Confederate Muster Rolls of Ships and Stations (in Confederate Navy Subject File).

Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns, New York Rendezvous, April 1861.

New York Adjutant-General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York, Volume 31.

Patrick Finan Widow’s Pension File Certificate 2867.

US Naval Historical Center Photographs.

Filed under: Navy, New York, Sligo Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Navy Pension Files, Sligo History, Sligo Veterans, USS Wabash, Widow's Pensions Files

April 17, 2014

United States Release for Irish in the American Civil War Book

I am delighted to announce that my book, The Irish in the American Civil War, will officially become available in the United States from the 1st May. Originally published for the Irish market last year, you can already order it online from vendors such as amazon.com. When it first came out I provided a brief overview of its contents, which I recap on below, in case you want to find out whats in it!

The Irish in the American Civil War (History Press)

THE IRISH IN THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

Introduction

Looks at the scale of Irish participation in the American Civil War, its links to the Famine generation, and why it is not better remembered in Ireland.

BEGINNINGS

The duel that almost changed history

The story of James Shields and the duel he challenged Abraham Lincoln to in 1842.

Witness to the first shots

The story of Commander Stephen Rowan and his ship the USS Pawnee at Fort Sumter in 1861.

The Irish at Sumter

Explores Irish involvement in the army before the war and in events such as John Browns Raid, before looking at the Irish who were in the Sumter garrison in 1861.

Facing the first battle

The story of three Irishmen and their different experiences of First Bull Run, and the subsequent effect it had on them and their families.

Recruiting for the Irish Brigade

Why would the Irish fight for the Union? Examining the motivations of Irishmen in New York through a speech given by Thomas Francis Meagher at the Academy of Music in 1861.

Following them home

Who made up green-flag regiments? This chapter looks at that question, using the 23rd Illinois Infantry as a case study.

REALITIES

A Yankee and Rebel at Antietam

Two Irishmen led their regiments towards the Cornfield at Antietam. Both Irish, one was a Yankee and one a Rebel- neither would survive the experience.

Slaughter in Saunders’ Field

The American Civil War presented an opportunity for industrial killing on a frightening scale, where large numbers of men could be wiped out in moments. This was what the Irish 9th Massachusetts experienced at Saunders’ Field, The Wilderness in May 1864.

Blood on the Banner

The story of Thomas Plunkett of the 21st Massachusetts, grievously wounded at Fredericksburg, but who went on to become an important symbol of the Massachusetts war effort.

Death of a General

Patrick Cleburne remains largely unknown in Ireland. This tells the story of his final moments, when he lost his life at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee in November 1864.

The last to fall

No less a person than George Meade held Thomas Alfred Smyth as one of his finest Generals. This briefly tells his story, and how he became the last Union General to die in the American Civil War.

An Irishman in Andersonville

The story of Michael Dougherty, later a Medal of Honor recipient, who kept a diary in Andersonville and also survived the Sultana disaster.

THE WIDER WAR

Killed by his Own

Looks at the reasons behind the New York Draft Riots, Irish involvement, and the death of one Irishman, Colonel Henry O’Brien, in horrendous circumstances.

Confederates in Ireland

The Confederate government sent a number of agents to operate in Ireland to prevent recruitment into the Union army. This looks at their efforts, techniques and the men involved.

The Queenstown Affair

When the USS Kearsarge anchored in Queenstown (now Cobh), Co. Cork in 1863, she sparked a diplomatic incident through allegations of illegal recruitment. For one Irishman the visit would change the course of his life.

The Civil War with Canvas and Camera

Not all Irishmen at the front were combatants. This tells the story of photographer Timothy O’Sullivan and Special Artist Arthur Lumley who used their talents to bring the war to the Home Front.

Jennie Hodgers and Albert Cashier

The remarkable story of Jennie Hodgers, who served as Albert Cashier in the 95th Illinois and kept up her male identity until well into the twentieth century.

The Irish ‘Florence Nightingales’

Looks at some of the Irish laywomen who went to the front to help with the war effort, such as Bridget Diver of Custer’s Wolverines, and Mary Sophia Hill of the Louisiana brigade.

AFTERMATH

Mingle my Tears

The cost of the war for many families at home was huge. This looks at how a number of families sought to cope with the loss of their loved ones at the front and the effect it had on their lives.

The price of gallantry

The consequences of the war could last for decades. This looks at wounded veterans, both physically and mentally, and the pain that the war could still cause long after the guns fell silent.

Hunting Lincoln’s Killer

Roscommon man Jame Rowan O’Beirne was in the room when Lincoln died, and was charged with hunting down John Wilkes Booth, a job he carried out diligently. This is his story.

The passage of years

How did old veterans remember the war as the years passed? How did the Irish community seek to remember these honoured veterans? This looks at these efforts as the numbers of veterans dwindled into the twentieth century.

Back to the stone wall

24 years after their heroic defence of the stone wall at Gettysburg, the 69th Pennsylvania returned to erect a memorial to their fallen comrades, and to meet some of their former foes. This is the story of that occasion.

Epilogue

Looks at JFK’s presentation of an Irish Brigade flag to the Irish people in 1963, and the future of remembrance of the American Civil War in Ireland.

Filed under: Media, Update Tagged: Book Publication, Great Irish Famine, Irish American Civil War, James Rowan O'Beirne, Patrick Cleburne, The History Press, The Irish in the American Civil War, Thomas Francis Meagher

April 13, 2014

A 150 Year Old Missing Persons Case- In Search of a 19-Year-Old Irishman

On 5th November 1862 ‘Arthur Shaw’, a 19-year-old Dubliner, stepped off the decks of the Great Western and into the hustle and bustle of New York City. From that day forward, his family never heard from him again. I have spent considerable time trying to piece together some elements of this boy’s story, aiming to uncover just who he was- and ultimately what became of him. (1)

Whatever happened to ‘Arthur’ in the months that followed his arrival in the United States, his family remained completely in the dark as to his movements. His parents were still at home in Ireland, and although he had family in America, it quickly became clear that he was not making his way to them. On 18th April 1863, some five months after he was last seen, his family placed an ad seeking information on him in the Boston Pilot. It transpired that ‘Arthur Shaw’ was not the boy’s real identity name at all- his actual name was Alexander Scarff:

INFORMATION WANTED OF ALEXANDER SCARFF who left his home on the 1st October last, in the steamer Great Western. Any person knowing of his whereabouts will confer great favor by communicating the information to his aunt, Mrs J D Clinton, Cincinnati P O, Ohio, or to his uncle Mr J P Clinton, Detroit P O, Michigan. (2)

The ad did not produce any results. A second effort published in the same paper on 2nd May that year included further detail, highlighting that Alexander was a native of Dublin, and his uncle’s full name was John P. Clinton. But the months turned to years and no word came. Fully seven years after these ads in the Pilot- on the 2nd April 1870- the New York Irish-American carried the following:

INFORMATION WANTED OF ALEXANDER SCARFF a native of Dublin who sailed from Liverpool in the ship Great Western, under the name of Arthur Shaw; arrived at Castle Garden on 5th November 1862; was then 19 years of age; has not since been heard of by his friends or parents; is supposed to have joined the U.S. Army. Any information of him will be thankfully received by his aunt, Mrs. J.D. Clinton, Bath-North, Greenbush, Rensselaer County, N. Y. (3)

Why had Alexander Scarff left his home in Dublin? Had his parents known of his intention to travel to the United States? Why did he travel under an assumed name- was he younger than the 19 years he proclaimed himself to be? Between his disappearance in 1862 and the 1870 ad his family had managed to piece together only scant additional information. It is impossible to comprehend the anguish that must have been felt by all concerned, no doubt greatly exacerbated by the lack of answers to their inquires.

Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office, Washington DC. She helped many families learn the fate of their loved ones following the Civil War, but unfortunately Alexander Scarff’s parents were not among them. (Photo by E.L. Malvaney)

On the 6th November 1862, one day after the Great Western had sailed into New York Harbor, a 19-year-old Irish-born clerk enlisted in the Union Army. Standing six feet tall, with dark hair, dark eyes and a dark complexion, Private Arthur Shaw would eventually muster in as a member of Company B, 174th New York Infantry Regiment. That December the regiment sailed for Louisiana, where it participated in the successful siege of Port Hudson. In the middle of July 1863, the New Yorkers found themselves engaged in an action that would become known as the Battle of Kock’s Plantation. It was an action where the Union forces and the 174th New York were badly mauled. Among the fallen was Private Arthur Shaw, who was killed in action on 13th July 1863. (4)

The balance of probability strongly suggests that the young Irishman who died at the Battle of Kock’s Plantation, Louisiana was Alexander Scarff. The soldier used the same name, was from the same country, was stated as being the same age and perhaps most convincingly enlisted in New York only a single day after the Great Western had docked in 1862.Why had he gone to America? Had he argued with his family? Had he been tempted across the Atlantic by the prospect of a large bounty, or was it intended he join those relatives already in America? Had he always planned to enlist, or was he convinced to join up just after his arrival? We will never know, but his adoption of a false name implies that he did not want his family to be able to track his journey.

Whatever the circumstances, Alexander’s parents and relatives clearly made desperate efforts- across many years- to learn his fate. Perhaps they suspected the worst. Although there are many questions we can’t answer about Alexander Scarff, we do have the answer to the one question that was most important to his family, a question for which they most probably never had an explanation. Thanks to the modern research tools available to us, it becomes possible for us to suggest the answer to the mystery of Alexander Scarff’s disappearance, albeit over 150 years too late for his family.

*The story of Alexander Scarff is one I have touched on before in this post, but which I felt deserved a more concentrated focus.

(1) New York Passenger Lists 1820-1957; (2) Harris et al: 186; (3) Ibid., New York Irish American 2nd April 1870; (4) Civil War Muster Roll Extracts, New York Adjutant General Report;

References

New York State Archives, Cultural Education Center, Albany, New York; New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900; Archive Collection #:13775-83; Box #:662; Roll #:318

New York Passenger Lists 1820-1957. Year: 1862; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 224; Line 25; List Number: 1092.

New York Irish American 2nd April 1870.

Adjutant General’s Office. Annual report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York for the year 1905.

Harris, Ruth-Ann M., Donald M. Jacobs, and B. Emer O’Keeffe, (eds.) Searching for Missing Friends: Irish Immigrant Advertisements Placed in “The Boston Pilot” 1831–1920. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1989.

E.L. Malvaney Flickr Photo Stream

Filed under: Dublin, New York Tagged: 174th New York Infantry, Battle of Kock's Plantation, Boston Pilot, Dublin History, Information Wanted, Irish American Civil War, Missing and Disappeared, New York Irish-American

April 7, 2014

Midleton’s Most Famous Forgotten Son? General John Joseph Coppinger

I am involved in a number of other blogs aside from the Irish in the American Civil War. One of these is the Midleton Archaeology & Heritage Project, based around the area where I live. Sometimes I can combine interests; the most recent post to the Midleton Heritage site is a piece on local man John Joseph Coppinger, who served in the Papal Wars, American Civil War, Indian Wars and Spanish-American War, ending his career as a General.

Originally posted on The Midleton Archaeology & Heritage Project:

Originally posted on The Midleton Archaeology & Heritage Project:

Many of Midleton’s men and women have emigrated down through the years, settling all over the globe and becoming part of the Irish diaspora. Some went on to become relatively famous abroad- for example Nellie Cashman- a woman who will be the topic a future post. However one man, although his family name remains closely associated with Midleton, is not well-known in the town of his birth. This is despite the fact that he is undoubtedly one of the town’s most successful and colourful emigrants. His name was John Joseph Coppinger.

Coppinger was born in Midleton on 11th October 1834, into the powerful Catholic landowning family. He was one of six children of William Joseph Coppinger and Margaret O’Brien. We don’t know much about John’s early life, until he begins his first associations with the military- associations that would continue across more than half a century. He first tested out the military…

View original 1,086 more words

Filed under: Cork Tagged: Cork American Civil War, Cork History, Indian Wars, Irish American Civil War, John Joseph Coppinger, Midleton History, Rubicon Heritage Services, Spanish-American War

April 3, 2014

Telling the Personal Stories of 41 Civil War Pensioners on Storify

For a number of months I have been researching the personal stories of US military pensioners who were living in Ireland in 1883. The vast majority of these men and women were Civil War pensioners, and it is my hope that I can publish a book in the future on their many and varied experiences.

As part of my ongoing commitment to digital engagement I decided that last weekend I would share some of these stories, originally researched and previously untold, on twitter. This took the form of a ‘tweetathon’- where a large number of tweets are focused on a single issue. Across two days I provided an introduction to the pension system and subsequently told the stories of 41 widows, dependent mothers and dependent fathers, broken up into byte-size 144 character chunks.

The reason I choose to engage in this way is because of the reach of these social media tools. My ultimate goal is to help develop a greater understanding in Ireland of the huge number of people from the island impacted by the American Civil War, and this is just one more tool to achieve that. However, I am also aware that many people do not like (or are not on) twitter, and may not have the opportunity to share in these stories. In order to rectify this I used the Storify service to create a readable and coherent ‘story’ of all the weekend’s tweets. Here each pensioner’s story can be read in sequence, with headings inserted to alert the reader to the specific individual they are reading about. In addition I have broken up the tweets with relevant videos and images that describe both the pension files and some of the locations and fates mentioned within the stories. If would like to see what this looks like, and read some of the 41 stories, you can do so by clicking this link: Storify- American Pensioners in Ireland.

I am interested to know what you think!

Filed under: Digital Arts and Humanities, Pensioners in Ireland Tagged: Dependent Fathers, Dependent Mothers, Irish American Civil War, Pensioners in Ireland, Storify Civil War, Twitter Civil War, US Military Pensions, Widow's Pension Files

March 26, 2014

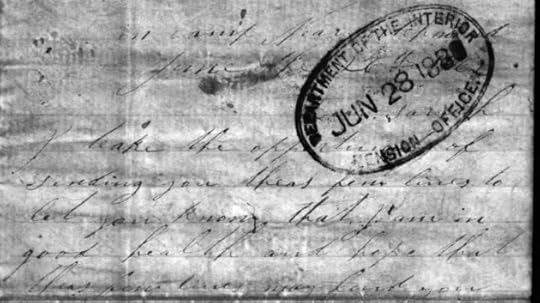

‘Remember me to all the folks’: The Last Letter to a Limavady Woman from her Husband

Widow’s Pension Files often contain extremely poignant information. As women sought to prove their connections to their deceased spouse, they sometimes had to submit what must have been extremely treasured possessions to the Pension Agency. For Sarah Jane Cochran of Limavady, Co. Londonderry, this meant handing over the last letter ever written to her by her husband Richey. This letter, penned only three days before his death, offers an insight into Richey’s experiences during what became known as the Seven Days Battles- the series of engagements that would ultimately kill him. Today the letter remains in Sarah Jane’s pension file in Washington D.C., and is here transcribed to be read for what is likely one of the first times in 130 years.

A Philadelphia street in the 1850s, when Richey and Sarah Jane Cochran lived there (Library of Congress)

Sarah Jane Smith and Richard (Richey) Cochran were married in the 9th Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia on 25th June 1856. At the time Sarah was about 27, while Richard, a teamster, was 26. The couple initially made their home on Rhoads Street in the city. It was there that they celebrated the birth of their first child, Jane, on 16th April 1857. On the 22nd March of 1861 the couple’s second child, William Richard, arrived. By now the family had moved to 42 Virgin Alley in Pittsburgh- the boy would be only 5 months old when his father marched off to war. (1)

With the outbreak of the conflict Richey decided to enlist, joining up on the 6th August 1861. His company of mainly Pittsburgh men would become Company H of the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry, under the command Colonel Alexander Hays. Although it seems Sarah may have been illiterate (she signed all her correspondence with an ‘x’), Richey wrote regularly to her- perhaps the letters were read to her by a friend. When Richey and his comrades went to Virginia’s Peninsula in the summer of 1862 as part of the Union drive towards Richmond, he made sure to keep her regularly up to date with his experiences.

Colonel Alexander Hays of the 63rd Pennsylvania, here shown as a Brigadier-General later in the war (Library of Congress)

In Camp Near Richmond

June the 26th 1862

Sarah,

I take the opportunity of sending you these few lines to let you know that I am in good health and hope that this few lines may find you all enjoying the same. I forgot to date the last letter I left it to the last and then forgot it. We have had a fairly hard time of it since. We have been fairly busy we moved our camp the day before yesterday and yesterday morning we left camp about 6 o’clock and went out to the outside picket line and our regiment was detailed for skirmishing the woods in front and it was a very unpleasant job the brush was so thick some pleases [places] that we could not see a man 5 yards from us and some pleases [places] we could not go thrugh in line but we got thrugh the best way we could and drove in their pickets and their reserves to we came to their main lines and then we stopt to the rest came up and formed in line and drove in their whole line and took their rifil pitts [rifle pits] from them and a redout but our regiment was not engaged only with the pickets when we were in line of battle the [there] were no attack maid on our front the the [sic.] regiments on our right and left had it very hard we lost no men only when we were skirmishing our company had 5 wounded I am not certain how many the other companys lost yet the [there] were some killed and last night the line behind us fired on us through mistake and killed 2 and wounded 3 or 4 but none in our company. We were in line all night till 6 o clock this morning it was about 11 o clock that the mistake hapened the [there] were fairly sharp firing of musketry all night now and then but it has been fairly quiet all day in this part of the line but how long it may continue I canot say. The [There] are some heavy fireing on the right this evening. [See Note 1]

June the 27th we were called out last night before I got finishing but we got in again soon the [there] were great cheering last night along all our lines and heavy fireing on our right the reports was here that the [they] were driving them on the right and some of our bands played till 12 o clock but the real cause I canot say we [were] all called out this morning ready to march and the fireing is still going on on our right but you will hear the results in the papers before this reaches you. I have not time to write much more as our guns is stacked and we have to fall in at any time. I was at the hospital a few days ago to see crampton he is geting better. I seen the 2 Mc Lelarns [?] and the [they] are both geting better so I will have to finish this time till I get more time. Remember me to all the folks. [See Note 2]

So no more for now at present

but remains your

husband

Richey Cochrans (2)

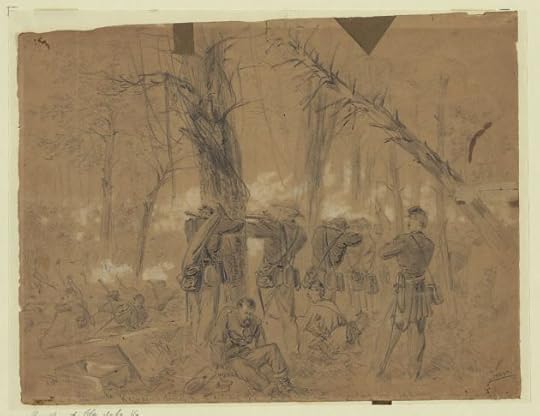

This sketch by Alfred Waud shows men of Kearney’s division in action during the Battle of Glendale, June 30th, 1862 (Library of Congress)

Almost exactly three days after Richey finished this letter to his wife, he found himself crouching behind an improvised breastwork of fence-rails with the rest of his regiment. Looking out across an open field towards woods some 300 yards away, he and his comrades awaited a Confederate attack they knew was coming. Before that though they had endure an artillery barrage, and watch helplessly as the Rebels unleashed a furious assault on the Pennsylvania Reserves to their left. They gazed on as the Reserves were driven back, all the time knowing their turn to face the onslaught was coming. As the artillery fire intensified on their position, Richey watched as a group of terrified slaves fled from a slave cabin midway between the lines. Not long afterwards, the slaves were followed across the fields by a veritable tide of men in gray. General Kearney remembered that the enemy came on ‘in such masses as I had never witnessed’. Richey, his regiment and his division watched as the Federal batteries to their front met the Rebels with a hail of fire. The cannon poured shot into the advancing Southerners, mowing them down by the dozen. But no matter how many gaps they tore in the advancing lines, more Confederates constantly seemed on hand to fill them. With the Union artillery to their front seemingly doomed, the men of the 63rd Pennsylvania were ordered forward to their support. With a cry of “Up! up! boys! charge!” the men broke cover and entered the field with a yell, surging past their threatened guns and forcing the Confederates back. Fighting at one point broke out in relatively close quarters around the slave cabin, but eventually the horrific cost exacted on the attacking waves forced the Confederates to retire. The men of the 63rd pulled back to their guns, where they lay low in front of them, firing towards the enemy for the rest of the afternoon and repulsing the enemy a further three times. General Kearney noted of Richey and his comrades that ‘the Sixty-third has won for Pennsylvania the laurels of fame.’ The Battle of Nelson’s Farm, or Glendale, was over- the Union army continued its march towards Harrison’s Landing, and the Seven Days battles would continue. Company H recorded the loss of five men wounded and two killed in the engagement. One of those left dead on the field was Richey Cochran, killed by a gunshot wound. (3)

Tragically for Sarah Jane, her hardships did not end with the death of Richey. On the 31st March 1864 their son, William, also died, just a few days after his third birthday. He was buried in grave 3, lot 14 of Mount Union Cemetery in Pittsburgh. It seems to have been this second tragic event that inspired Sarah Jane to give up on the United States and return home to Limavady, Co. Londonderry. Although she had initially received a pension in 1863, by the early 1880s she was seeking the retrospective payment of support for her daughter Jane for the period of time when she had been under 16. In order to prove who she was to the U.S. authorities, both she and her daughter had to make a statement as to their identity. In addition Sarah Jane asked her first cousins- William McCloskey (a grocer) and Jane McCloskey of Drumagosker, near Limavady, to swear as to her bone fides. A friend who had lived nearby in Philadelphia and had also returned to Ireland- Mathilda Lindsay of Coleraine- also gave evidence on her behalf. (4)

Sarah Jane Cochran received a widow’s pension for her husband’s service until her death in March 1905- she had outlived her husband by almost 43 years. In 1880, when seeking her additional payments, Sarah Jane had to give up what was surely one of her most treasured possessions- the last letter she had received from her husband in 1862. (5)

The first page of the last letter written by Richey Cochran to Sarah Jane in June 1862, stamped with June 1880 when it was received by the Pension Office (Fold3)

Note 1: Richey is here describing the 63rd Pennsylvania’s actions of June 24th, 25th and 26th as what became known as the Seven Days’ Battles around Richmond were commencing. His regiment served in the 1st Brigade of the Third Division (Brigadier-General Philip Kearney’s), part of Major-General Samuel P. Heintzelman’s Third Corps. The skirmishing Richey recounts on June 25th was the regiment’s part in the Union attack that became known as the Battle of Oak Grove, the first of the Seven Days battles, which started with Union forces taking the offensive. The heavy firing on the right that Richey heard on the evening of June 26th was likely fighting that was part of the Battle of Beaver Dam Creek (or Mechanicsville) as the Confederates began to launch their counterstrokes to drive the Federals back, under their new commander, Robert E. Lee.

Note 2: The reason for the cheering Richey recorded on the night of June 26th was due to an announcement made by the 63rd’s adjutant regarding the fighting that day at Beaver Dam Creek. He had told the men: “General Porter attacked the enemy today at Beaver Dam, and has beaten them at every point. The rebels are in full retreat.” [p.114] Although the battle had been a tactical victory for the Union, the Rebels had no intention of retreating. Lee would keep hammering at the Federals with the ultimate intention of forcing the Yankees away from Richmond. The firing that Richie heard while writing the next day, June 27th, was the opening stages of the Battle of Gaines’s Mill, as the Confederates launched a huge assault on the Union right. He writes that ‘we have to fall in at any time’- as the situation worsened during the day his regiment did get orders to move- at about 6 o’clock that evening- but were halted before 10 o’clock as the fighting had died down; the day had ended in Confederate victory. Richey mentions going to see ‘Crampton’- this was Thomas Crampton, also of Company H. Thomas would be wounded at the Second Battle of Bull Run on 29th August 1862 and was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate on 31st December 1862 (roster p.516). It has not been established who the ‘McLelarns’ were- they do not appear to have served in Richey’s company but presumably were friends from Pennsylvania.

Note 3: Although original spellings have been kept in the letter some punctuation has been added for ease of reading.

(1) Richard Cochran Widow’s Pension File, US Federal Census 1860; (2) Bates 1869: 516,Richard Cochran Widow’s Pension File; (3) Hays 1908: 123-9, 133-4; (4) Richard Cochran Widow’s Pension File; (5) Ibid.;

References & Further Reading

Richard Cochran Widow’s Pension File WC14220.

1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll.

US Federal Census 1860.

Bates, Samuel P. 1869. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861-5. Volume 2.

Hays, Gilbert Adams 1908. Under the Red Patch: Story of the The Sixty Third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861- 1864.

Civil War Trust Seven Days Battles Page

Civil War Trust Battle of Glendale Page

Richmond National Battlefield Park

Filed under: Derry, Londonderry, Pennsylvania, Pensioners in Ireland Tagged: 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Derry/Londonderry, Irish American Civil War, Irish Veterans, Limavady History, Seven Days Battles, Soldiers Last Letter, Widow's Pension Files