Damian Shiels's Blog, page 44

July 28, 2014

Gangs of New York: Recruiting the Irish ‘Straight Off the Boat’

One of the best known scenes in Martin Scorcese’s 2002 movie Gangs of New York is that which depicts the enlistment of Irish emigrants ‘straight off the boat’ into the Union army. The seemingly unsuspecting men are quickly dressed in uniform and packed off for the front, even as those unfortunates who have gone before are brought back in coffins. This scene is one of the most influential in dictating modern memory of Irish recruitment into the Union army. The popular image of thousands of Irishmen, ignorant of what they were getting into, joining up the moment they stepped ashore is one I encounter frequently. But how true is it?

Irish emigrants are recruited ‘straight off the boat’ in Gangs of New York

There is little doubt that many Irishmen enlisted in the Union army very shortly after their arrival in the United States. There is even some evidence of illegal recruitment from Ireland itself, although this appears to have been extremely rare. When Irishmen were ‘duped’ into joining the army, it was unfortunately often the case that it was other Irishmen – like Patrick Finney- who were the ones trying to profit from their enlistment. It is also open to question just how unaware the Irish landing in America were of the realities of the American Civil War . The sheer number of Irish in the United States meant that there was a constant flow of information about the conflict crossing the Atlantic. Many of these letters- written before the age of censorship- gave explicit detail of what was occurring in America between 1861 and 1865, and of what service in the Northern armies meant.

The more I investigate the Irish experience, the more apparent it is that the type of incident portrayed in Gangs of New York rarely, if ever, occurred. Far from being duped, it was much more likely that many of these men had travelled to the United States with the express intention of joining the military, in the hope of benefiting from the financial rewards available for doing so. This was the primary motivation for Irish enlistment in the Union Army from at least 1863 onwards. These men were not stupid- they came from a country where enlistment in the British Army for economic reasons was commonplace, and they came informed about the Civil War.

The New York Irish-American Newspaper of 23rd July 1864 presents an interesting counter-point to the scene depicted in Gangs of New York. It outlines that serious consideration had in fact been given to opening a recruiting station at Castle Garden, where Irish and other emigrants arrived in America. However, they decided against it, as it was thought it would ultimately prove counter-productive. The main reason put forward for this was that Irish-American and other communities would quickly inform those at home as to what was going on, discouraging future prospective emigrants. This would impact not only the economy, but ultimately also enlistment into the military. You can read the Irish-American article below.

Gangs of New York Cinematic Poster (Miramax)

NO RECRUITING IN CASTLE GARDEN

The New York County Volunteers Recruiting Committee, presided over by Mr. Orison Blunt, recently applied to the Commissioners of Emigration for permission to establish a recruiting rendezvous within and in connection with the emigration depot at Castle Garden. The Commissioners very properly refused such permission, and authorized their agent to convey such intelligence to the Committee. The following is a copy of the letter of Mr. Casserly:-

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONERS OF EMIGRATION, NEW YORK, JUNE 30

Elijah F. Purdy, Esq.:

Dear Sir- Mr. O. Blunt, the Chairman of the County Recruiting Committee and member of the Board of Supervisors, called here yesterday, and stated that he had conversed relative to a building to be erected on the Battery for recruiting purposes, with some of the Commissioners, and concerning a passage-way opening into and connection Castle Garden with said building, and that he had been sent to me for the purpose of learning if there were any objection to such connection with Castle Garden. In reply I informed him that I had not heard anything about the matter before, and that I believed there were no serious objections; which, however, I did not deem proper to state at that time, but would do so in case the matter came before the Board at the meeting to be held in the afternoon, and my opinion was requested by the Board. To do so sooner, on such an important matter, might have been considered an assumption of authority on my part.

At the meeting to-day, I mentioned the matter to several of the Commissioners, and while on account of their being no quorum, and as no official communication had been received by this Board from the Board of Supervisors or any other body, there could be and was no official action taken on the matter; yet the opinion of the Commissioners was decidedly adverse to granting such a request, on the ground that it would be injurious to the country in interfering with emigration, as would be the case as soon as known in Europe; and would be confirmatory, to a certain extent, of the charges made in the British House of Commons, as well as in France and Germany, by rebel emissaries and sympathizers, that the armies were being filled by the forced enlistments of arriving emigrants. As it is, the resident friends of emigrants expected to arrive are much excited on this very subject at present, and their persuasions and advice, in the form of letters of their friends in Ireland and Germany, as well as other countries from which emigrants come, would be immediately added to keep emigration from the country, and thus an injury inflicted on the industrial prosperity of the country exceeding a thousand fold the increased benefit in the way of additional recruits obtained in the manner proposed by Mr. Blunt.

Being a member of the Board of Supervisors, as well as of this Commission, I have deemed it proper to advise you of what occurred in relation to this matter, to which I have taken the liberty of appending my own views of the application, as the subject appears to me.

Yours respectfully,

Bernard Casserly,

General Agent.

(1) New York Irish American 23rd July 1864;

References

New York Irish American 23rd July 1864. No Recruiting in Castle Garden.

Filed under: Discussion and Debate, New York Tagged: Castle Garden, Five Points, Gangs of New York, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish in the Union Army, Martin Scorcese, Patrick Finney

July 20, 2014

The Creation of an Irish Widow: The 33rd New Jersey at Peachtree Creek, 20th July 1864

On the 20th July 1864, the 33rd New Jersey Infantry of the Army of the Cumberland found themselves at Peachtree Creek, outside Atlanta. They were gathered on a hill some 300 yards in front of the main Union position acting as an outpost for their brigade. Their divisional commander, John White Geary, thought attack unlikely. He was mistaken. Lieutenant-Colonel Enos Fourat of the 33rd gave his version of what happened next:

…the enemy, advancing in mass through the woods, drove back the skirmishers instantly and rushed down upon us with loud yells, pouring in volley after volley. We were without shelter, but my men kept their ground defiantly and returned the fire with vim. Almost immediately another overwhelming force came down upon our right flank. I threw two companies around to protect that flank. They were too weak, and down they came upon us on the double-quick; at the same time still another column came out upon our left flank. Under these circumstances, with such an overwhelming force against us and on three sides of us, with such a withering fire from front, right, and left, and the enemy rapidly gaining our rear, to stand longer was madness, and I reluctantly gave the order to retire fighting. As the men rose and commenced to retire, with a yell of exultation the enemy rushed upon us with his dense masses and pressed so close that he ordered the surrender of our colors. With this order we could not comply. The fire was terrific; the air was literally full of deadly missiles; men dropped upon all sides; none expected to escape. The bearer of our State colors fell; 1 of the color guard was killed and 1 or 2 missing. The enemy were too close upon us to recover the colors; it was simply impossible, and it is with feelings of the deepest sorrow I am compelled to report that our State colors fell into the hands of the enemy, at the same time we feel it to be no fault of ours…(1)

The Peachtree Creek Battlefield in Georgia, with graves of the fallen (Library of Congress)

The veritable destruction of the 33rd New Jersey was one of the major Confederate successes of the Battle of Peachtree Creek. The battle was John Bell Hood’s first as commanding General of the Army of Tennessee, but it ultimately failed to halt the relentless Union drive on Atlanta. A number of men in the unfortunate 33rd that day were Irish. Some would be among the captured, who in the months to come would have to take their chances in the lottery of life and death that was the experience of a being a prisoner of war in the 1864 South. That was not to be the fate of Private Hugh Shields. (2)

Hugh had enlisted in the ranks of the 7th New Jersey Infantry on 2nd September 1861, serving with them in the Army of the Potomac through 1862. His connection with that regiment ended on 26th January 1863, when the rosters show he was discharged for disability. He returned home to Hoboken, New Jersey, where he lived on Court Street, between 2nd and 3rd. The draft registration records for June 1863 show that the 30-year-old laborer was in fact suspected as having deserted from the ranks of the 7th New Jersey. Whatever the reality, on 25th August Hugh decided to go back to war, joining the 33rd on the promise of a bounty of $375. So it was that when the Rebels overran the regiment’s position at Peachtree Creek on 20th July 1864, Hugh Shields was among the Yankees on the exposed hill. He breathed his last there, dying instantly with a bullet wound to the head. Today he rests in Marietta National Cemetery, Grave 7155. (3)

An Alfred Waud sketch of a marriage in the 7th New Jersey Infantry. This took place shortly after Hugh left the regiment (Library of Congress)

Hugh’s 28-year-old wife Margaret, also from Ireland, was widowed by the Battle of Peachtree Creek. Hugh and Margaret (née Gaffney) had been married at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Hoboken on 23rd September 1858. Within two months of Hugh’s death she was seeking the pension she required to help maintain herself- it was granted in April 1865 at a rate of $8 per month, commencing from the date of her husband’s death. (4)

Margaret spent a little over five years as a widow. Eventually she decided to tie the knot with another member of Hoboken’s Irish-American community; on 4th October 1869 Margaret married Peter Smith, an Irish-born plasterer. Peter and Margaret spent over two decades together, but in the 1890s Margaret would find herself once again turning to her first husband’s wartime service in search of financial support. (5)

The grave of Hugh Shields in Marietta National Cemetery, Georgia (Photo: Helen Jeffrey Gaskill)

It seems that by 1893 the couple, then giving their address as 306 Newark Street in Hoboken, had fallen on hard times. Clearly in need of money, on 8th December 1892 Margaret- now in her fifties- submitted a new pension application based on Hugh’s service. Although her entitlements to a pension had ceased following her remarriage, she claimed in 1892 that she had only received a single payment based on her husband’s service, in the month of April 1865. Margaret stated that she had been ignorant about what she could claim in the 1860s, and as a result had received neither Hugh’s bounty money nor any payments between April 1865 and the time of her remarriage in 1869. The subsequent investigation seems to suggest that Margaret had indeed received Hugh’s bounty money as part of an initial lump sum payment in 1865, which included her deceased husband’s back pay. For whatever reason- perhaps it was ignorance of her entitlements as she claimed- it does appear that she neglected to collect her $8 per month for the next four years. (6)

The Bureau of Pensions decided not to approve payment. Their decision was made easier by a letter they received, dated 25th May 1893:

Hoboken May 25th 1893

Commissioner of Pensions

Washington

Sir,

The claimant Margaret Smith, died suddenly- having no issue- but a husband in destitute circumstances and who had to defray all expense of funeral & c. Please inform who and how the claim when awarded claim can be shown, by whom and what proceedings are required by your department.

Respectfully Yours,

Louis Budenbender

Att for claimant (7)

The application was rejected on 8th June 1893. Hugh Shields’s death with the 33rd New Jersey at Peachtree Creek on 20th July 1864 led to the creation of a pension file that allows us to view snippets of his widow’s experiences across the next thirty years. Margaret’s was a life which remained closely tied to Hoboken’s Irish-American community, and one which appears for the most part to have been lived in poverty. The National Archive pension files offer Irish scholars their best opportunity to follow Irish emigrants such as Hugh and Margaret across the Atlantic, as we seek to discover what life held in store for them once they left Ireland for America. For Hugh Shields it was ultimately death; for Margaret Gaffney and Peter Smith it was a tough, hard life among Hoboken’s Irish-American community. (8)

New York, Brooklyn, Jersey City & the Hoboken Waterfront as they appeared in a Currier & Ives sketch of 1877 (Library of Congress)

(1) Castel 1992: 373, OR: 225; (2) Hugh Shields Widow’s Pension File, 1860 US Federal Census; (3) Draft Registration Records, New Jersey AG Vol. 1: 338, New Jersey AG Vol. 2: 989; (4) Hugh Shields Widow’s Pension File; (5) Hugh Shields Widow’s Pension File, 1880 US Federal Census; (6) Hugh Shields Widow’s Pension File; (7) Ibid.;

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

Hugh Shields Widow’s Pension File WC44980.

New Jersey Adjutant General 1876. Record of Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Civil War 1861-1865 Volume 1.

New Jersey Adjutant General 1876. Record of Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Civil War 1861-1865 Volume 2.

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 38, Part 2. Lieutenant-Colonel Enos Fourat Report of the Action of 20th July 1864.

US Civil War Draft Registration Records, New Jersey Fifth Congressional District, Volume 2.

US Federal Census 1860, Hudson, Hoboken 2nd Ward.

US Federal Census 1880, Hudson, Hoboken 4th Ward, 7th Assembly District, 2nd District.

Castel, Albert 1992. Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

Civil War Trust Battle of Peachtree Creek Page

Filed under: Battle of Peachtree Creek, New Jersey Tagged: 33rd New Jersey Infantry, 7th New Jersey Infantry, Battle of Peachtree Creek, Civil War Widow's Pensions, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, National Archives

July 17, 2014

‘Your Likeness Was Buried With Him': A Letter to An Irish Soldier’s Wife After Gettysburg

The second day of the Battle of Gettysburg was a tough one for New York’s Excelsior Brigade. Although not an ethnic Irish formation, many of the brigade’s regiments- such as the 70th New York Infantry- had large contingents of Irishmen in their ranks. The 2nd July at Gettysburg left many of these men dead. In the days after the fighting, officers and acting officers set about the unpleasant task of informing relatives as to their loved ones’ fate. One of them was Thomas J. Chaffer, who sat down on 10th July to write the following letter to Mary McKenna in New York.

The Excelsior Brigade Monument at Gettysburg (Photo: Cory Hartman)

July 10th 1863

Mrs. Mc Kenna this letter just reached here and it pains me to write you these few lines but brace yourself for the worst your Husband was killed on the battle feild of Gettyisburgh on the second day of July he died a brave man and was nobly fighting for his country and its rights you must bear up with his loss as well as you can for there is many left in the same way may God guard and protect you and your little ones through this world of battles as I am in command of this company I had to open seven letters so as to see where to direct this letter to you you have my best wishes yours truly,

Lieut. T.J. Chaffer

In the same letter Lieutenant Chaffer also added the following note:

Your likeness was buried with him your husband had nothing with him of any value no money or any such thing and soon as we get into camp I will see that his effects are made out and the papers sent on to you your husband was buried on the battle feild no more

Yours Truly

Lieut Thomas J Chaffer

Co. C 1st Regt

Excelsior Brigade

Washington D.C. (1)

Thomas Chaffer (borne as Chaffee on the roster) had been a First Sergeant in Company C leading up to Gettysburg, where the 70th New York suffered 117 casualties. In 1864 he was officially promoted First Lieutenant and re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer, but appears to have been wounded in the Overland Campaign, which ended his service. The subject of the letter, John McKenna (or McCanna), had originally served in the 2nd New York Infantry. His death in his early thirties at Gettysburg left four children without a father. John’s remains were later re-interred at Gettysburg National Cemetery where they still rest in Section F, Site 54. It is not known if the photo of his wife, originally buried on the field with him, also made the transition. (2)

(1) John McCanna Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid; New York Adjutant General Roster of the 70th New York Infantry;

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

John McCanna Widow’s Pension File WC88061

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 70th New York Infantry

Gettysburg National Military Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, New York Tagged: 70th New York Infantry, Battle of Gettysburg, Excelsior at Gettysburg, Excelsior Brigade, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration

‘Your Likeness Was Buried With Him’: A Letter to An Irish Soldier’s Wife After Gettysburg

The second day of the Battle of Gettysburg was a tough one for New York’s Excelsior Brigade. Although not an ethnic Irish formation, many of the brigade’s regiments- such as the 70th New York Infantry- had large contingents of Irishmen in their ranks. The 2nd July at Gettysburg left many of these men dead. In the days after the fighting, officers and acting officers set about the unpleasant task of informing relatives as to their loved ones’ fate. One of them was Thomas J. Chaffer, who sat down on 10th July to write the following letter to Mary McKenna in New York.

The Excelsior Brigade Monument at Gettysburg (Photo: Cory Hartman)

July 10th 1863

Mrs. Mc Kenna this letter just reached here and it pains me to write you these few lines but brace yourself for the worst your Husband was killed on the battle feild of Gettyisburgh on the second day of July he died a brave man and was nobly fighting for his country and its rights you must bear up with his loss as well as you can for there is many left in the same way may God guard and protect you and your little ones through this world of battles as I am in command of this company I had to open seven letters so as to see where to direct this letter to you you have my best wishes yours truly,

Lieut. T.J. Chaffer

In the same letter Lieutenant Chaffer also added the following note:

Your likeness was buried with him your husband had nothing with him of any value no money or any such thing and soon as we get into camp I will see that his effects are made out and the papers sent on to you your husband was buried on the battle feild no more

Yours Truly

Lieut Thomas J Chaffer

Co. C 1st Regt

Excelsior Brigade

Washington D.C. (1)

Thomas Chaffer (borne as Chaffee on the roster) had been a First Sergeant in Company C leading up to Gettysburg, where the 70th New York suffered 117 casualties. In 1864 he was officially promoted First Lieutenant and re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer, but appears to have been wounded in the Overland Campaign, which ended his service. The subject of the letter, John McKenna (or McCanna), had originally served in the 2nd New York Infantry. His death in his early thirties at Gettysburg left four children without a father. John’s remains were later re-interred at Gettysburg National Cemetery where they still rest in Section F, Site 54. It is not known if the photo of his wife, originally buried on the field with him, also made the transition. (2)

(1) John McCanna Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid; New York Adjutant General Roster of the 70th New York Infantry;

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

John McCanna Widow’s Pension File WC88061

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 70th New York Infantry

Gettysburg National Military Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, New York Tagged: 70th New York Infantry, Battle of Gettysburg, Excelsior at Gettysburg, Excelsior Brigade, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration

July 15, 2014

‘The Yells of Wild Beasts and Shoshone Indians': An Irish Silver Miner in Nevada, 1864

Though the American Civil War was one of the greatest conflicts in the history of Irish people, the vast majority of Irishmen chose not to fight in Union blue or Confederate gray. Some of them went West, often in the hope of making good in new territories. 150 years ago this month one Irishman wrote back to New York, describing his life as a silver miner in the vast expanse of the Nevada territory.

Silver was first discovered in Nevada at the Comstock Lode in 1858. In 1862 further deposits were discovered in the Reese River district, where ‘Rambler’, the Irish letter writer, penned the description below. He was based in Amador, a town established in 1863 after the discovery of silver there. It reached its peak in 1864, when ‘Rambler’ was present, but the silver was not as extensive as first thought. By 1869 the last resident had left, turning it into a ghost town (you can read more about it here). ‘Rambler’ describes St. Patrick’s Day in Austin, Nevada, a town also founded on the back of the silver rush, in 1862. Although thousands of people lived in the area in the 1860s, today just a few hundred can be found there (you can read more about Austin here). Among the fascinating details of Rambler’s account are the miners relations with Brigham Young and the members of his Latter Day Saint Movement in Utah Territory, who were one of the trading suppliers to the Nevada settlements.

Austin, Nevada as it appeared during the King Survey in 1868. ‘Rambler’ describes the St. Patrick’s Day parade here in 1864. This photograph was taken by famed American Civil War photographer (and Irishman) Timothy O’Sullivan (Smithsonian Institution)www

THE LIFE OF A MINER

Amador, Nevada Territory

June 1 1864

To the Editors of the Irish-American:

Gentlemen- Notwithstanding the far distance and craggy road between here and there, your good and faithful journal pursues its way, and nothing enters to us into this wild country that is received with such welcome as a number of the IRISH-AMERICAN. Doubtless you have a vast number of eager readers and New York and the Eastern States; but I’d venture to say that they don’t prize it as much as we far-off miners.

As a matter of course you have a pretty good idea of what a sailor’s and a soldier’s life is; but very few understand what a miner’s life is, save those who have traveled through some of these mineral countries and experienced a little of the hardships a miner has to undergo in prospecting for both silver and gold. This country differs a great deal from California with regard to prospecting; for in the latter-named place a miner could take his pick, pan and shovel in the morning and have the produce of his day’s work in with him in the evening. But in prospecting the silver mines of this Territory, a man must have the back of a mule and the courage of a lion. He must know how to wash and mend his own clothes; to cook his own beans; to make his own bread; he must learn to sleep in the sage brush, with nothing between him and heaven but one pair of old blankets; he must learn to let snakes and all kinds of obnoxious reptiles crawl around him whilst asleep or awake; he must learn how to drink alcohol, and call it the best of cognac; he must learn to pack his blankets and grub; and he must learn not to growl if he thinks a storekeeper is cheating him, and after that he has to take his sledge, drill, pick, powder and fuse and go dig and blast in the face of the mountain, following a ledge of silver and gold, which he sees in his imagination, and follows for months in the bowels of the mountain. If he is lucky enough he may strike it at a distance of between two and three hundred feet. Not until then does the so-called “capitalist,” or rather the “land shark,” come along and take hold of the lion’s share, and the first thing the poor miner hears of is that there is a freeze-out game aboard; and the next thing he is made to understand is that his ledge has been sold for something; but as a matter of course, he cannot help it. He has not got any money; he lets matters slide, and, going into something in the shape of a bar-room, to sit and chat and smoke, drowns his trouble in a drink or puffs it off in smoke. But to return to the storekeepers. They are the most honest and agreeable creatures in the world. They never charge over two prices for anything, since they have to get everything from California. Flour they sell at $20 per hundred; by we must thank out stars that we have our good friend, Brigham Young, who sends his produce along and underrates our California merchants ten per cent in his flour; and whilst he underrates then fifty per cent in quality. In this our storekeepers make a mistake, but as the poor miner buys a sack of flour, and pays the highest price for it, it is not until he brings it home and makes a loaf of bread out of it that the mistake is found out.

Brigham I have never seen; but folks say that he entertains the greatest welcome for his approaching neighbors, and as a mark of regard he also sends some of the nicest potatoes you ever saw, and only charges 20 cents per pound for them. They look just as if they were made for miners’ use, because he can take a round dozen of them in his jaw, and keep up his corner in telling yarns about his girl in good plain English. Brigham also sends us some very fine eggs, and charges only $1 per dozen. Your humble scribbler, having a hankering for eggs, a few days ago went and bought a dollar’s worth, and, after a close examination, found he had not only a dozen of eggs, but a dozen of live chickens in the bargain.

I see by your good paper that St. Patrick’s Day is still appreciated with the old feelings. You must not think that, although we are in this country, far from friends, we let it pass unnoticed. No, sirs, we had a very pleasant celebration, for the first time in this part of the country. It’s too far gone to state all the proceedings, but I tell you that our firemen’s procession, headed by the Austin brass band, playing the old Irish airs, and our ball in the evening, made the hills around Austin ring, where nothing but the yells of wild beasts and Shoshone Indians and been heard twelve months before.

RAMBLER. (1)

(1) New York Irish-American 9th July 1864

References

New York Irish-American 9th July 1864. The Life of a Miner.

Filed under: Life in America Tagged: Austin, Brigham Young, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Old West, Nevada Silver Rush, Nevada Territory, Shoshone, Utah Territory

‘The Yells of Wild Beasts and Shoshone Indians:’ An Irish Silver Miner in Nevada, 1864

Though the American Civil War was one of the greatest conflicts in the history of Irish people, the vast majority of Irishmen chose not to fight in Union blue or Confederate gray. Some of them went West, often in the hope of making good in new territories. 150 years ago this month one Irishman wrote back to New York, describing his life a silver miner in the vast expanse of the Nevada territory.

Silver was first discovered in Nevada at the Comstock Lode in 1858. In 1862 further deposits were discovered in the Reese River district, where ‘Rambler’, the Irish letter writer, penned the description below. He was based in Amador, a town established in 1863 after the discovery of silver there. It reached its peak in 1864, when ‘Rambler’ was present, but the silver was not as extensive as first thought. By 1869 the last resident had left, turning it into a ghost town (you can read more about it here). ‘Rambler’ describes St. Patrick’s Day in Austin, Nevada, a town also founded on the back of the silver rush, in 1862. Although thousands of people lived in the area in the 1860s, today just a few hundred can be found there (you can read more about Austin here). Among the fascinating details of Rambler’s account are the miners relations with Brigham Young and the members of his Latter Day Saint Movement in Utah Territory, who were one of the trading suppliers to the Nevada settlements.

Austin, Nevada as it appeared during the King Survey in 1868. ‘Rambler’ describes the St. Patrick’s Day parade here in 1864. This photograph was taken by famed American Civil War photographer (and Irishman) Timothy O’Sullivan (Smithsonian Institution)www

THE LIFE OF A MINER

Amador, Nevada Territory

June 1 1864

To the Editors of the Irish-American:

Gentlemen- Notwithstanding the far distance and craggy road between here and there, your good and faithful journal pursues its way, and nothing enters to us into this wild country that is received with such welcome as a number of the IRISH-AMERICAN. Doubtless you have a vast number of eager readers and New York and the Eastern States; but I’d venture to say that they don’t prize it as much as we far-off miners.

As a matter of course you have a pretty good idea of what a sailor’s and a soldier’s life is; but very few understand what a miner’s life is, save those who have traveled through some of these mineral countries and experienced a little of the hardships a miner has to undergo in prospecting for both silver and gold. This country differs a great deal from California with regard to prospecting; for in the latter-named place a miner could take his pick, pan and shovel in the morning and have the produce of his day’s work in with him in the evening. But in prospecting the silver mines of this Territory, a man must have the back of a mule and the courage of a lion. He must know how to wash and mend his own clothes; to cook his own beans; to make his own bread; he must learn to sleep in the sage brush, with nothing between him and heaven but one pair of old blankets; he must learn to let snakes and all kinds of obnoxious reptiles crawl around him whilst asleep or awake; he must learn how to drink alcohol, and call it the best of cognac; he must learn to pack his blankets and grub; and he must learn not to growl if he thinks a storekeeper is cheating him, and after that he has to take his sledge, drill, pick, powder and fuse and go dig and blast in the face of the mountain, following a ledge of silver and gold, which he sees in his imagination, and follows for months in the bowels of the mountain. If he is lucky enough he may strike it at a distance of between two and three hundred feet. Not until then does the so-called “capitalist,” or rather the “land shark,” come along and take hold of the lion’s share, and the first thing the poor miner hears of is that there is a freeze-out game aboard; and the next thing he is made to understand is that his ledge has been sold for something; but as a matter of course, he cannot help it. He has not got any money; he lets matters slide, and, going into something in the shape of a bar-room, to sit and chat and smoke, drowns his trouble in a drink or puffs it off in smoke. But to return to the storekeepers. They are the most honest and agreeable creatures in the world. They never charge over two prices for anything, since they have to get everything from California. Flour they sell at $20 per hundred; by we must thank out stars that we have our good friend, Brigham Young, who sends his produce along and underrates our California merchants ten per cent in his flour; and whilst he underrates then fifty per cent in quality. In this our storekeepers make a mistake, but as the poor miner buys a sack of flour, and pays the highest price for it, it is not until he brings it home and makes a loaf of bread out of it that the mistake is found out.

Brigham I have never seen; but folks say that he entertains the greatest welcome for his approaching neighbors, and as a mark of regard he also sends some of the nicest potatoes you ever saw, and only charges 20 cents per pound for them. They look just as if they were made for miners’ use, because he can take a round dozen of them in his jaw, and keep up his corner in telling yarns about his girl in good plain English. Brigham also sends us some very fine eggs, and charges only $1 per dozen. Your humble scribbler, having a hankering for eggs, a few days ago went and bought a dollar’s worth, and, after a close examination, found he had not only a dozen of eggs, but a dozen of live chickens in the bargain.

I see by your good paper that St. Patrick’s Day is still appreciated with the old feelings. You must not think that, although we are in this country, far from friends, we let it pass unnoticed. No, sirs, we had a very pleasant celebration, for the first time in this part of the country. It’s too far gone to state all the proceedings, but I tell you that our firemen’s procession, headed by the Austin brass band, playing the old Irish airs, and our ball in the evening, made the hills around Austin ring, where nothing but the yells of wild beasts and Shoshone Indians and been heard twelve months before.

RAMBLER. (1)

(1) New York Irish-American 9th July 1864

References

New York Irish-American 9th July 1864. The Life of a Miner.

Filed under: Life in America Tagged: Austin, Brigham Young, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Old West, Nevada Silver Rush, Nevada Territory, Shoshone, Utah Territory

July 5, 2014

‘If You Ever Want To See Him Alive…Come Immediately': A Race Against Time For An Irish Soldier’s Wife

Felix Mooney was 53-years-old when he enlisted in what became Company D of the 61st New York Infantry on 12th August 1861. Wounded at the Battle of Malvern Hill on 1st July 1862, he was taken prisoner and sent to Richmond. By the time he was exchanged on 27th July he had to be sent straight to hospital, having developed chronic diarrhoea. On 11th September his wife of almost six years Mary (née McGinty), received the following extremely concerning note from Felix’s nurse:

Newport News VA Sept 11 ’62

Mrs. Mooney

By request of your husband I write these lines to you he requested that if you ever want to see him alive to come immediately to this place he is very low indeed he says there is over 4 months pay due him so that you can have that to pay all expenses hereafter. I don’t think he can live long at the longest but I will try and do the best I can to keep him alive until you shall see him if it is possible but you will have to come soon as you get this don’t fail to come if posible. No more at present,

From M. O. Sutton the Nurse of Felix

yours truly

Go to Baltimore and procure a pass from Gen. Wool (1)

Felix’s former comrades of Company D, 61st New York Infantry, as they appeared in the Spring of 1863 (Library of Congress)

Only three days before Felix had sent his wife a letter, most probably dictated by him to Nurse Sutton:

Newport News VA Sept 8

Dear Wife,

I now have a few lines written to you to let you know that I have got those things you sent me it was 6 days getting to mee and all was spoiled except the brandy. The chickens milk tobacco all was sented with the chickens so I had to throw them away it was to bad but it can’t be helped. Now I am still pretty low with the dirahea I wish they would send mee to New York Hospital so that you could come and see me before I die. I guess they will send me before long I am very weak indeed dear Wife but I still have hopes of getting well so to join my family once more I want to see you all very bad once more. Give my love to Ann and Patrick. Write after to me I thank you kindly for sending those things to mee although they were spoiled it was not your fault. I don’t think of much to write to day so I will close for to day. Write after,

Yours Truly,

I Remain Until Death,

Your Loving Husband,

Felix Mooney. (2)

On receipt of the note from Nurse Sutton, Mary immediately set out for Newport News in company with her brother. When they reached Washington her brother could not receive a pass to go through the lines, so she was forced to travel on alone. In what must have been exceptional effort Mary arrived in Newport News on 16th September, only five days after the note was sent. Despite her haste, she was too late. Upon arrival she was informed that Felix had died the previous day, and had his body had already been buried. The newly widowed woman left Virginia the same day, for her lonely return to Brooklyn. (3)

(1) AG report 1893, Felix Mooney Pension File; (2) Felix Mooney Pension File; (3) Ibid.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

New York Adjutant General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General for the State of New York.

Felix Mooney’s Widows Pension File WC98996

Civil War Trust Battle of Malvern Hill Page

Filed under: New York Tagged: 61st New York Infantry, Battle of Malvern Hill, Civil War Disease, Civil War Widow's Pensions, Civil War Women, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish in the Union Army

‘If You Ever Want To See Him Alive…Come Immediately’: A Race Against Time For An Irish Soldier’s Wife

Felix Mooney was 53-years-old when he enlisted in what became Company D of the 61st New York Infantry on 12th August 1861. Wounded at the Battle of Malvern Hill on 1st July 1862, he was taken prisoner and sent to Richmond. By the time he was exchanged on 27th July he had to be sent straight to hospital, having developed chronic diarrhoea. On 11th September his wife of almost six years Mary (née McGinty), received the following extremely concerning note from Felix’s nurse:

Newport News VA Sept 11 ’62

Mrs. Mooney

By request of your husband I write these lines to you he requested that if you ever want to see him alive to come immediately to this place he is very low indeed he says there is over 4 months pay due him so that you can have that to pay all expenses hereafter. I don’t think he can live long at the longest but I will try and do the best I can to keep him alive until you shall see him if it is possible but you will have to come soo as you get this don’t fail to come if posible. No more at present,

From M. O. Sutton the Nurse of Felix

yours truly

Go to Baltimore and procure a pass from Gen. Wool (1)

Felix’s former comrades of Company D, 61st New York Infantry, as they appeared in the Spring of 1863 (Library of Congress)

Only three days before Felix had sent his wife a letter, most probably dictated by him to Nurse Sutton:

Newport News VA Sept 8

Dear Wife,

I now have a few lines written to you to let you know that I have got those things you sent me it was 6 days getting to mee and all was spoiled except the brandy. The chickens milk tobacco all was sented with the chickens so I had to throw them away it was to bad but it can’t be helped. Now I am still pretty low with the dirahea I wish they would send mee to New York Hospital so that you could come and see me before I die. I guess they will send me before long I am very weak indeed dear Wife but I still have hopes of getting well so to join my family once more I want to see you all very bad once more. Give my love to Ann and Patrick. Write after to me I thank you kindly for sending those things to mee although they were spoiled it was not your fault. I don’t think of much to write to day so I will close for to day. Write after,

Yours Truly,

I Remain Until Death,

Your Loving Husband,

Felix Mooney. (2)

On receipt of the note from Nurse Sutton, Mary immediately set out for Newport News in company with her brother. When they reached Washington her brother could not receive a pass to go through the lines, so she was forced to travel on alone. In what must have been exceptional effort Mary arrived in Newport News on 16th September, only five days after the note was sent. Despite her haste, she was too late. Upon arrival she was informed that Felix had died the previous day, and had his body had already been buried. The newly widowed woman left Virginia the same day, for her lonely return to Brooklyn. (3)

(1) AG report 1893, Felix Mooney Pension File; (2) Felix Mooney Pension File; (3) Ibid.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

New York Adjutant General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General for the State of New York.

Felix Mooney’s Widows Pension File WC98996

Civil War Trust Battle of Malvern Hill Page

Filed under: Battle of Malvern Hill, New York Tagged: 61st New York Infantry, Battle of Malvern Hill, Civil War Disease, Civil War Widow's Pensions, Civil War Women, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish in the Union Army

July 4, 2014

American Independence Day: Remembering How Ireland Forgets

Today is the 4th July, Independence Day in the United States. Throughout the day there will undoubtedly be a number of Irish-American themed stories and soundbytes in Ireland, as is appropriate given our historic links with the United States. From my own perspective, it is also a day to reflect on just how much Ireland as a nation chooses to neglect that relationship with her diaspora in America. This neglect in memory is becoming starker and starker when remembrance of the American Civil War is measured against the efforts being poured into our only other comparable experience of conflict- World War One. A mere 49 years separate these two events, the only in Irish history where 200,000 + Irishmen marched off to war.

An Taoiseach Enda Kenny with President Barack Obama in The White House (Wikipedia)

With the 100th anniversary of the Great War on the horizon in August, many impressive new memorials have been erected around the country. Irish television and radio have adopted World War One as a major recurring theme, and Irish newspapers consistently return to the topic of personal experiences of the war. Irish Universities are running numerous conferences about the Irish experiences of the war (see examples at UCC, UCD, NUIG, TCD). As someone who is also involved in World War One research, I am delighted to see this program of events. However, the huge divergence in how both conflicts are remembered also tells us much about Ireland, and how we on the island view Irish history. By and large the Irish Government, Media and Educational institutions are overwhelmingly insular when it comes to the history of Ireland and the Irish. The stories of those who emigrated come an extremely poor second to the stories of those who stayed behind. As I have often highlighted on this blog, there is yet to be a single comparable event to those cited above for World War One which relates to the Irish experience of the American Civil War. This is despite the direct causal links that can be drawn between Ireland’s 19th century calamity- The Great Famine- and many Irishmen’s participation in the 1861-65 war.

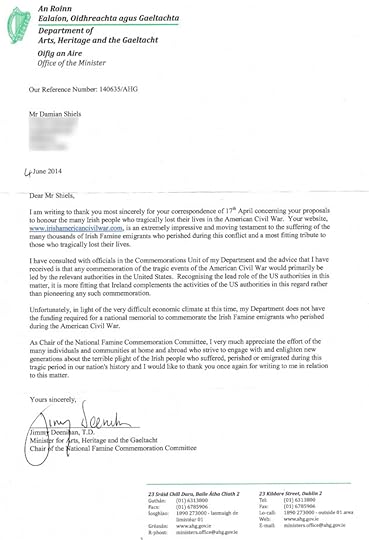

As part of continuing efforts to see some recognition of the impact of the American Civil War on hundreds of thousands of Irish people, I wrote to the Irish Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Jimmy Deenihan TD last April. I did so in his capacity as Chair of the National Famine Commemoration Committee. Despite our annual commemoration of the Famine, we rarely tie this event with the deaths of thousands of Irishmen in the 1860s, many of whom were in the United States as a direct result of that Famine. Having had a number of efforts to have the impact of the American Civil War on Irish people remembered and discussed fail over the course of the 150th, my purpose in writing to the Minister was to see if it would be possible for the State to formally acknowledge the scale of Irish involvement in the conflict as part of the upcoming International Famine Commemoration speech in New Orleans. If you are interested in seeing the letter I provide the full text below. In early June I received a response from Minister Deenihan (also below). The Minister’s reply was extremely gracious. In it he noted that he had consulted the Commemorations Unit of his Department on the topic of the Irish experience of the American Civil War, who advised him that any commemoration of Irish involvement should be primarily led by authorities in the United States. He also pointed out that due to the (very real) economic difficulties being experienced in Ireland at this time, there was no funding for anything such as a memorial to the Irish experience of the conflict.

I greatly appreciate that the Minister took the time to respond to my letter. I was interested to learn that the Irish Government’s position is that any remembrance of the Irish involvement in the Civil War should be driven by the United States. I admit to finding this position somewhat odd- for example Ireland is not taking the view that remembrance of the Irish in World War One should be driven by the British Government. Indeed I imagine such a position would be met with outrage in many quarters. I strongly believe it is Ireland’s responsibility to remember, acknowledge and explore the experiences of Irish people around the world; we should not be waiting for a call from other nations to engage with the history of our diaspora. Neither is it clear what approaches the Irish Government have made to the United States Government with respect to becoming involved in U.S. commemoration of the American Civil War, although it may be that there have been efforts in this direction. I also fully understand the Minister’s position that there is no available funding for a memorial. Again, this would be easier to accept if it were not for the significant financial efforts being made by the State with respect to World War One. I have been unable to locate figures for the Government budget with regard to World War One commemorations, but it is certainly higher than the budget of €0 that has thus far been allocated to the Irish of the American Civil War.

I will take the Minister’s advice and correspond with the U.S. Chargé d’affaires in the Irish embassy, on the basis that Ireland is keen to participate in U.S. led commemoration of the impact of the American Civil War on Irish emigrants. Although the Minister did not address the request to see Irish involvement acknowledged within the New Orleans Famine Commemoration speech, time will tell if that is something that will be highlighted at the event. I will keep readers of the blog updated on both these fronts. All in all- despite the Minister’s kind words- it seems likely that the policy of forgetting these Irish emigrants is set to continue.

LETTER TO MINISTER JIMMY DEENIHAN TD, DEPARTMENT OF ARTS, HERITAGE AND THE GAELTACHT

17th April 2014

Dear Minister Dennihan,

I am writing to you in your capacity as Chair of the National Famine Commemoration Committee. I was delighted to hear that this year’s commemorations will take place in Strokestown and New Orleans respectively. I wanted to request that consideration be given at either or both of these events to officially remember the Irish who were impacted by the American Civil War some 150 years ago. The 150th of this event runs from 2011-2015, but unfortunately as a nation we have yet to make any official statement with regard to the many Irish who lost their lives in this conflict- many thousands of whom were Famine emigrants.

You may not be aware that the American Civil War is the largest conflict in the Irish historical experience alongside World War One. At least 1.6 million Irish-born people lived in the United States in 1861, and some 200,000 fought in the war. Tens of thousands of these men died. Indeed it is likely that more men from what now constitutes the Republic of Ireland fought in the American Civil War than in World War One. Nor is it an event of the distant past; the last known Irish-born veteran was still alive in 1950. Despite this being one of the most seminal moments in the experience of the Irish diaspora, and the second great trauma in many Famine emigrants’ lives, we have yet to officially mark the anniversary in Ireland. We have no national memorial, we have held no commemorative events and had no conferences to discuss this war’s impact on Irish people.

My colleagues and I have made a number of attempts to highlight the scale of Irish participation over recent years, but unfortunately have largely failed. Our most recent effort to see these 200,000 Irishmen marked with a commemorative stamp in 2015 was unfortunately rejected by An Post, and seemingly with that the State’s last opportunity to acknowledge the devastating effect of this war on Irish emigrants 150 years ago has passed. It is my hope that perhaps the inclusion of an official reference to the anniversary of the conflict and its importance and impact on Irish emigrants might be considered as part of the Famine commemorations.

I am aware of your own deep personal interest in history- indeed when I wrote to politicians a number of years ago regarding the Irish Brigade flag in the Dáil I received the most encouraging response from you. I have dedicated much of my time over the past five years to remembering Irish people’s stories on my website www.irishamericancivilwar.com and elsewhere; prior to that I was fortunate to be one of the curatorial team who prepared the Soldiers & Chiefs exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland. I listened with great interest to your recent speech at the World War One Conference in UCC (an event at which I also spoke) and the importance of remembering that event. Thankfully the memory of World War One has been pulled back into the light, and is no longer a forgotten conflict in Ireland. It is my hope that we will at some juncture take the necessary steps to remember our other Great War, fought by our Famine emigrants 150 years ago. I had the good fortune to publish a book on the Irish experience of the American Civil War last year, and I enclose a copy of that for your interest.

Yours Sincerely,

Damian Shiels

The Response of Minister Jimmy Deenihan TD

Filed under: Memory Tagged: American Civil War Commemoration, Civil War Memory, Department of Arts Heritage & The Gaeltacht, Ireland and The Great War, Irish American Civil War, Jimmy Deenihan TD, World War One, World War One Commemoration

July 2, 2014

From Galway to Georgia: B.T. Johnston, Famine Emigrant, Confederate Pensioner

Increasingly many of the personal stories featured on the site are based on the contents of Federal Pension files. Having recently returned from the excellent Ulster-American Heritage Symposium at the University of Georgia, Athens- during which I had the pleasure to visit the Kennesaw Mountain battlefield- I thought it appropriate to have a look at the pension file of an Irishman who had served both Georgia and the Confederacy. It presents as an opportunity to highlight the types of information you can expect from Confederate pension files, and appropriately focuses on a veteran of the Atlanta Campaign.

An example of a Georgia Infantry Regiment (the 4th) in 1861 (Library of Congress)

Unlike their counterparts who served to preserve the Union, Confederate veterans and their dependents did not become eligible for Federal pensions until 1958. However, a number of former Confederate states did offer pensions to former Rebels and their families, dependent on their disability and status as ‘indigent’- effectively someone who was destitute. These pensions were not provided by the state for which you served, but rather by the state in which you lived at the time of your application.

Towards the end of 1914 Benjamin Taylor Johnston- B.T. to all who knew him- was working as a coal miner in Texas. B.T. was just about to turn 69 when an accident in the mine ended his working career. According to the doctor, B.T.’s foot was ‘badly mashed’ in the incident, and given his age and the severity of the break it was deemed unlikely he would ever be entirely well again. The event placed B.T. in dire financial straits, and prompted him to apply to the state of Texas for a pension based on his Confederate service in order to support both himself and his wife Nancy. They had been married in Gordon, Georgia on 20th July 1876, but had been calling Texas home since 1889. In his application based on ‘indigent circumstances’- dated 22nd July 1915 and written from Strawn, Palo Pinto, Texas- he outlined his service as he remembered it, events which had taken place half a century previously:

I was born in Gallwag [Galway] Irland December 17 1845. I was raised in Georgia Hall County. I inlisted in the Confedrete Army in 1862 April 2. Evanes Batallion Sharp Shooter Company after receiving 3 more companys it was orginized in the 64 Regment of Harisons Brigade [64th Georgia Infantry].

I inlisted in Atlata GA. went to the coast of Florida in August in a scirmish near Pencicola I got slightly wounded I was sent to the hospitle at Savana GA. I was discharged there by order of Sectary of War through application of my mother on account of my minority. In Sep the same year I ran away from mother and went to Murphys Burr [Murfreesboro], I inlisted there in Nov. Stanifordsburne Miss Battrey [Stanford's Mississippi Battery] after the Battle of Murphys Dec 31 to Jan 1 1863 at Stone River we fell back to the Tulahoma from there to Chatanooga after we fought the Battle of Chichnauga which was fought Sept. 19 and 20 of the same year. After our misfourtune at Missonary Ridge in Nov we fell back to Dalton GA. We stayed through the winter of 1863 and 1864 we fought Mill Creek Ridge and Rock Face Mountian on May 7 and 8 1864. From there we fell back to Resacca GA on Ostanolla River we fought on the 14 and 15 day of May 1864 late in the evening. On the 15 I was severly wounded in the right knee they sent me to the hospitle at Mongomry Alabama from there I was discharged and went home. On the 14 of July I enlisted in Edmonsons Calvery detach service [Georgia Militia] which was afterwards was Edmonsons Battalion I belong to Co. E of same after orgainising Capt Ramseys Company again. I got slightly wounded while crossing Chathoochie River.

In March 1865 I was detailed not transfered to General Findley escort and surrendered at Kingston Georgia on May 6 1865. Capt Findley had command of the detail which I surrendered with which was noted on my payroll. I was in the fighting from Murphysbur to Resacca Georgia,

Yours, B.T. Johnston (1)

The Battlefield of Resaca (Library of Congress)

B.T. claims to have been wounded while serving with Evans’ Sharpshooters in the five month period before they formed a part of the 64th Georgia Infantry (of which Evans became Colonel). B.T. is recorded as having enlisted in Atlanta on 28th May, becoming entitled to a bounty of $50 Confederate. Some of B.T.’s claims do not seem to be borne out by his surviving records. He is on the regimental roll of the 64th Georgia for July and August 1863, but was not present at the time of the next surviving roll in September and October 1864, having presumably been wounded while the regiment was serving in Florida the previous autumn. His presence with the 64th Georgia at this time would have prevented B.T. from being in many of the actions he describes with Stanford’s Mississippi Battery, such as Stones River. However, he does appear to have served with the Battery, at least for a time. In 1864 he is described on the Mississippian’s rolls as 18-years-old, with light hair, blue eyes and a fair complexion. A farmer by occupation, he was 5 feet 5 inches in height and was from Hall County, Georgia. B.T. was listed as having been absent without leave since 17th May 1864 (the 15th was when B.T. claims he was wounded at the Battle of Resaca), although he again appears on a receipt roll for clothing issued on 30th June 1864. B.T. himself claims that he became a member of Edmondson’s Cavalry on 14th July 1864. (2)

It is not possible to determine if the gaps in B.T.’s story are due to the loss of Confederate records or down to the Galwegian remembering things somewhat differently to how they occurred. Perhaps there were some elements of his time in the army that he wished to gloss over in favour of highlighting others. In anycase, there was little doubt that he was a bone fide Confederate veteran and as such B.T. received a pension from the state of Texas starting in December 1915. B.T.’s adventures were not yet over, however. In 1916 he decided to make his way from Palo Pinto to Birmingham, Alabama to participate in the United Confederate Veterans Reunion. B.T. never made it. On 13th May the Texas Pension Certificate Commissioner received the following somewhat cryptic telegram:

NEW ORLEANS LA 525PM MAY 13th 16

JONES PENSION CERTIFICATE COMMISSIONER

AUSTIN TEXAS

B T JOHNSON NUMBER THREE ONE EIGHT SEVEN FOUR IS HE ALL RIGHT

LARRY J SAVAGE

ANV (3)

B.T.’s fellow veteran Larry Savage was quoting the Irishman’s pension certificate number. The reason behind his concerns were clarified in a follow up letter written by B.T. to the Commissioner of Pensions on 22nd May:

Dear Sir,

One day last week you got a telegram from 1 J Savage of New Orleans making inquiry about my soldure record. Now to explain this matter to you I will say that I was on my way to Birmingham to the reunion and being crippled I stoped at New Orleans and was selling the picture of Lee and his generals and the police arrested me and sayd the city did not allow business of that character carried on in the city hence the telegram of enquiry after they found out that I was an old confederate they wanted me to go to the home there but I did not except their proposition.

Respectfully B.T. Johnston Certificate #31874 (4)

The fact that B.T. was attempting to make some extra money by peddling images of the great Confederate generals speaks much about both his pride and his efforts to leverage his veteran status in order to earn a living. B.T. narrowly escaped the New Orleans home and returned to Strawn, presumably having missed out on the reunion. He died at his home of apoplexy on 6th September 1923 at the age of 77; his widow Nancy subsequently sought financial support. Although far less numerous than the Federal pension files, there is nonetheless much to be learned from analysis of Irishmen and their family’s in the Confederate files- particularly those who fell on hard times. It seems likely given B.T.’s year of birth and the probable date of his emigration to Georgia that he and his family were Famine-era emigrants. The extremely hard life he appears to have led across Georgia and Texas, encompassing his Civil War service, should be regarded as part of a continuation of what is Ireland’s transnational Famine legacy.

(1) B.T. Johnston Pension File; (2) Ibid., B.T. Johnston CSR; (3)B.T. Johnston Pension File; (4) Ibid.

References

B.T. Johnston Texas Pension File #31874

B.T. Johnston Confederate Service Record 64th Georgia Infantry

B.T. Johnston Confederate Service Record Stanford’s Mississippi Battery

Civil War Trust Battle of Resaca Page

Filed under: Galway, General, Georgia Tagged: 64th Georgia Infantry, Atlanta Campaign, Battle of Resaca, Confederate Pensions, Galway Veterans, Great Irish Famine, Irish American Civil War, Stanford's Mississippi Battery