Damian Shiels's Blog, page 45

June 22, 2014

The Americanist Independent- A New Journal of American History

Many of you will be familiar with historian Keith Harris who runs the excellent Keith Harris History blog. A number of months ago I was delighted to hear that Keith was embarking on a new project to produce an online journal, specifically aimed at providing a publishing opportunity to undergraduates, graduate students and independent scholars. It is a project Keith is extremely passionate about and I was delighted to contribute a paper for Volume 1, Issue 1 of the result- The Americanist Independent- A Monthly Journal of United States History. My paper is titled ‘Explorations in Visualizing the Irish of the American Civil War.’ The other contributors are Keith McCall, who looks at the development of slavery databases using 20th century slave narratives; Samantha Upton who examines elite women in Boydton, Virginia during the era of Reconstruction, and Damien Drago who discusses innovative approaches to teaching history and engaging fourth and fifth graders through the use of music in the classroom.

The Journal is a monthly publication and is available at a Charter Member subscription of $4.97, which sounds a pretty good deal! If you are interested in subscribing (and reading my paper in Volume 1!) you can do so by clicking here or on the image below.

The Americanist Independent (Keith Harris)

Filed under: Research, Update Tagged: American Civil War Visualization, Digital Humanities, Irish American Civil War, Irish History, Journal of American History, Keith Harris History, Online History Journal, The Americanist Independent

June 21, 2014

Visualizing One Irishwoman’s Experience of the American Civil War Using StoryMap JS

As most of you are aware by now, I am constantly looking at new techniques to visualize the Irish experience of the American Civil War. My latest foray into this area has been with StoryMap JS, a free tool developed by Knightlab at Northwestern University. StoryMap is designed to allow you to tell stories with maps, facilitating the integration of multimedia such as images, Wikipedia entries, videos and audio clips into the storyline. At the suggestion of Shawn Day (thanks Shawn for pointing me in its direction!) I have used StoryMap to examine one individuals experience of the American Civil War. It concentrates on Sarah Jane Cochrane of Limavady, Co. Londonderry. You can see her StoryMap by clicking here or on the image below. It works in a similar fashion to a slideshow, so when you are finished with a page click on the right or left arrow to advance or move back in the storyline. Let me know what you think!

Sarah Jane Cochran: Irish Pensioner of the American Civil War (StoryMap)

Filed under: Derry, Media, Research Tagged: 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry, Digital Arts & Humanities, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, KnightLab, Northwestern University, StoryMap JS, Visualization Tools

June 16, 2014

The Forgotten Sixty-Ninth: A Thesis on the 69th New York National Guard Artillery

Although a significant amount has been written about the wartime exploits of the Irish Brigade, particularly between 1861 and 1863, very little ink has been spilt on the other Irish brigade formation- Corcoran’s Irish Legion. This is a serious anomaly given their significance with respect to both Irish-American attitudes towards the Civil War and also their extremely close ties to the Fenian movement. Longtime friend of the site Christopher Garcia is an expert on the Legion, particularly on its most famous unit, the 69th New York National Guard Artillery (also designated the 182nd New York). Christopher completed his Masters on that regiment in 2012, and I am delighted to say that he has generously made it available through the New York State Military Museum website. It is an extremely interesting read and well worth checking out- you can access it here.

Aside from Christopher’s work there are a number of other Masters and PhD theses of which I am aware that are now available online, and I include links to some of these below. I will shortly add them to the Resources section of the site- in the meantime if you are aware of any other relevant titles of this ilk please let me know!

Selected Masters and PhD Theses Available Online

Garcia, Christopher 2012. The Forgotten Sixty-Ninth: The Sixty Ninth New York National Guard Artillery Regiment in the American Civil War

Gillespie, William T. 2001. The United States Civil War: Causal Agent for Irish Assimilation and Acceptance in US Society

Myers, Kaitlyn 2013. “Walking with Our Ancestors”: Music and Constructions of Irish-American Identities at Civil War Re-enactments

Truslow, Marion A. 1994. Peasants into Patriots: The New York Irish Brigade Recruits and Their Families in the Civil War Era, 1850-1890

Vaticano, Patricia 2009. A Defense of the 63rd New York State Volunteer Regiment of the Irish Brigade

Filed under: 69th New York National Guard, Corcoran's Irish Legion Tagged: 182nd New York Infantry, 69th New York National Guard Artillery, Christopher Garcia, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Fenian Movement, Irish American Civil War, Irish in New York, Michael Corcoran

June 14, 2014

150 Years Ago: Dipping Handkerchiefs in the Blood of General Polk

150 years ago today the Confederate Bishop General- Leonidas Polk- a Corps commander in the Army of Tennessee, lost his life when he was struck by a Union shell on Pine Mountain, Georgia during the Atlanta Campaign. David Power Conyngham, a journalist from Corhane, Killenaule, Co. Tipperary, was one of the first Union men to see the site of Polk’s death. He would later describe the rather macabre activities carried out by both he and other men at the spot, perhaps providing a glimpse of the toll the war had taken on these men by 1864.

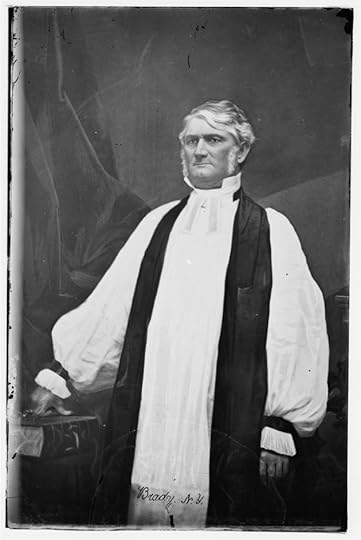

Bishop and Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (Library of Congress)

On 14th June Polk was in company with Generals Johnston, Hardee, Jackson and their staffs as they observed Federal movements in front of their position atop Pine Mountain. Patrick Cleburne’s Adjutant, Irving Buck, outlined the events that followed, as he later heard them:

‘General Johnston mounted Beauregard’s works and turned his field glasses to the left, when a shot directed at him came directly from the front. He immediately turned his glasses upon the battery firing, at the same time directing the staff and escort to disperse. General Polk moved off by himself, walking thoughtfully along, his hands folded behind his back, his left side towards the enemy, when a second came, then a third, the last of which- a Parrott shell- struck him, entering his left arm, passing through his body, emerging from his right arm, then struck a tree and exploded.’ (1)

Pine Mountain, Georgia, where Gen. Polk was Killed (Library of Congress)

David Power Conyngham was following Sherman’s advance towards Atlanta as a correspondent for the New York Herald and for a time as a member of Brigadier-General Henry M. Judah’s staff. He had previously spent time as a volunteer aide with the Irish Brigade, and after the conflict would pen the most famous account of that unit, The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns. He also recorded his experiences with Sherman, in his 1865 book Sherman’s March through the South. Conyngham credits Sherman himself with directing the fire on the Confederate officers which led to Polk’s death. The Tipperary man later saw the spot where Polk fell, and describes the activity that he and others engaged in at the site:

‘When we took that hill [Pine Mountain], two artillerists, who had concealed themselves until we had come up, and then came within our lines, showed us where his [Polk's] body lay after being hit. There was one pool of clotted gore there, as if an animal had been bled. The shell had passed through his body from the left side, tearing the limbs and body to pieces. Doctor M—- and myself searched that mass of blood, and discovering pieces of the ribs and arm bones, which we kept as souvenirs. The men dipped their handkerchiefs in it too, whether as a sacred relic, or to remind them of a traitor, I do not know.’ (2)

Conyngham’s is a fascinating account of the supposed actions of Union soldiers at the site where and enemy General fell. The idea of keeping fragmented parts of the body as souvenirs and dipping handkerchiefs in the blood of their fallen enemy is one I have not come across before- have any reader’s encountered any similar accounts from the Civil War?

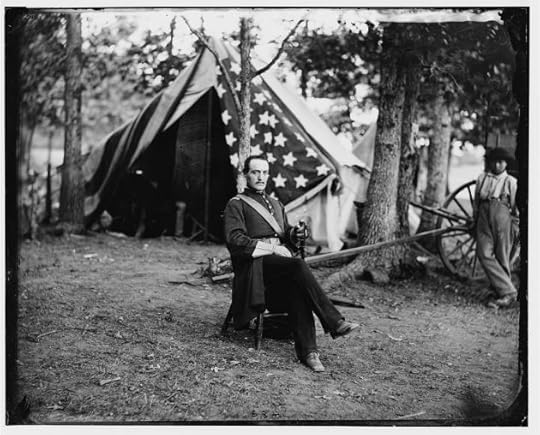

Captain David Power Conyngham while serving with the Irish Brigade (Library of Congress)

(1) Buck 1908: 223; (2) Kohl (ed.) 1994: xviii-xxi, Conyngham 1865: 112;

References

Buck, Irving Ashby 1908. Cleburne and His Command

Conyngham, David Power 1865. Sherman’s March Through the South

Kohl, Lawrence (ed.) 1994. Conyngham, David Power. The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns (1st Edition 1867)

Filed under: Atlanta, Tipperary Tagged: Atlanta Campaign, David Power Conyngham, Death of General Polk, Irish American Civil War, Irving A Buck, Leonidas Polk, Patrick Cleburne, Pine Mountain

June 12, 2014

‘I Hope Soon To Be With You’: The Civil War in Texas and Cork, 1866

We tend to view the surrenders of Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston in April 1865 as marking the end of the American Civil War, but for many thousands of volunteer Federal soldiers their time in uniform still had many months to run. Even after the official end of the conflict, death could still find these men at the end of a bullet. Equally, the war retained its potential to alter the course of people’s lives after 1865; thousands of miles away, it even forced some elderly Irish men and women to seek out the emigrant’s boat.

Kennedy and Mary O’Brien had been married in Cork. Two of their children, one son and one daughter, survived to adulthood. Kennedy died in London sometime in the mid-1840s; the family, already poor, now found themselves on the breadline. In the 1850s as their son John grew older he decided to seek out the stability of a military career and joined the British Army. He spent a number of years as a redcoat before the war raging between North and South, which presented a tempting economic opportunity, drew him to America. (1)

John O’Brien was recorded as enlisting as a Private in the 18th New York Cavalry at Watertown on 1st February 1864. Although listed as 21-years-old, it seems probable he may have been slightly older. Initially assigned to the defences of Washington D.C., John would travel with the regiment to the Department of the Gulf and service in Louisiana as the war drew to a close. It was from here that he wrote home to Ireland in May 1865:

Greenville La. May 18th 1865

Dear Mother,

I write you these few lines hoping you are in good health as this leaves me at present. The war is nearly at a close and we are mounted and waiting orders. We expect it will be for New York as the army is being reduced. I hope our regiment will be one of the lucky ones. I sent you Five Pound English money by Adams Express from New Orleans which I hope you will receive. You will write me and let me know as soon as you receive it and let me know how you are getting along and how Sister is and I could not get the ear-rings but I will recollect her and perhaps bring them to her myself. I will send my own ring in this letter for Sister and she will keep it and remember me. No more at present. I hope soon to be with you by the help of God and be able to do something for you. God help and preserve you is the sincere prayer of your,

Affectionate Son,

John O’Brien

I am sorry I can not send anything? for Mother and Mrs O’Keef but I will try to send in my next letter I have heard nothing of Brother Patrick I got a letter from Cousin Mat he is well and working at harness making in West Troy. As soon as you receive this write as soon as you as can as I will be anxious to know you get it safe. (2)

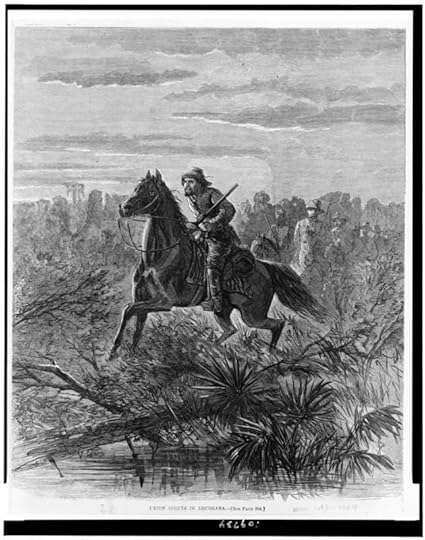

Union scouts operating in Louisiana in 1864 (Library of Congress)

Two days after John wrote to his mother he was promoted to Sergeant, but his hopes of returning to New York went unfulfilled. The regiment was instead sent to Western Mississippi before being assigned to Texas that November. Texas was a lawless place in the immediate post-war period, with feuds and bands of ‘Jayhawkers’ presenting a constant threat. On 23rd April 1866 Sergeant O’Brien was one of a number of men of the regiment travelling between San Antonio and Yorktown when they were set upon at a place called Kelly’s Station. During the fight that followed, the Corkman was shot and killed- his file records that he was ‘murdered by Jayhawkers.’ Likely candidates for his killers would appear to be the Taylor Gang, pro-Confederates who were operating in the area at this time and who were suspected of shooting a number of soldiers and freedmen that year. (3)

Less than a month after John was killed the 18th New York Cavalry were mustered out of service. Back in Ireland, his mother Mary must have been shocked to learn of his death in combat, so long after the end of the war. She now faced the added prospect of complete destitution, having relied on money from her son for the essentials of life. She successfully received John’s arrears of pay in 1867 following representations to the American consul in Ireland, but in order to secure a permanent pension she decided to make her away across the Atlantic. Her daughter was already in New York, eking out a living with her laborer husband. So it was that at the age of 65 Mary took ship, and in 1868 applied for a dependent mother’s pension. It was granted- she would receive it each month for almost twenty years before her death in 1887. (4)

The experience of the O’Brien’s illustrates the inherent dangers of military service in the 19th century, even after the majority of guns fell silent. John’s mother Mary was far from the only elderly Irish parent who travelled to America in search of financial security following 1865- their’s was a type of emigration forced upon them in the winter of life- a result of the terrible death toll that the American Civil War had exacted.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Widow’s Pension File; (2) A-G Report, Widow’s Pension File; (3) Freedman’s Bureau, Widow’s Pension File; (4) Ibid.;

References

John O’Brien Widow’s Pension File WC129249

New York Adjutant General Report 18th New York Cavalry Roster

Filed under: Cork, Pensioners in Ireland Tagged: 18th New York Cavalry, Civil War Texas, Cork Veterans, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Jayhawkers, New York Irish, Widow's Pensions

June 8, 2014

An Appearance in Civil War Times Magazine

Each month Professor Susannah Ural of The University of Southern Mississippi runs the ‘Ural on URLs’ feature in Civil War Times magazine, exploring the Civil War on the internet. Many readers of this site will be familiar with Professor Ural’s work through publications such as The Harp and the Eagle and Civil War Citizens. I was honoured that this month she chose as her focus my recent efforts to tell the stories of 41 Civil War pensioners in Ireland through the use of Twitter and Storify. For those who missed it, you can read more about that project and find a link to the Storify article here. In the Civil War Times piece Professor Ural provides more detail on the story of Cornelius Garvin and his mother Catherine from Bruff, Co. Limerick. Cornelius was killed in action with the 52nd New York Infantry at Spotsylvania in 1864- he and his mother’s story remains one of the most remarkable I have come across. To find out more about it be sure to check out the Civil War Times!

Civil War Times August 2014 (Civil War Times)

Filed under: Pensioners in Ireland, Update Tagged: Battle of Spotsylvania, Bruff, Civil War Times, Co. Limerick, Irish American Civil War, Military Pensions, National Archives, Professor Susannah Ural, Widow's Pension Files

June 4, 2014

Speaking Engagement: Ulster-American Heritage Symposium, Athens, Georgia, June 26-28

I am delighted to announce that I will be speaking as part of the Ulster-American Heritage Symposium, taking place in Athens, Georgia from June 26–28. This is the 20th occurrence of the biennial Symposium and is titled ‘Contacts, Contests, and Contributions: Ulster-Americans in War and Society.’ The event, which takes place in the University of Georgia Richard B. Russell Building Special Collections Libraries, is sponsored by the T.R.R. Cobb House, the Scotch-Irish Society of the USA, the Georgia Humanities Council, the UGA Department of History and the Willson Center. The aim of the symposium is to explore transatlantic emigration, settlement, and continued experience of people from the north of Ireland. The keynote speaker is Dr. David Gleeson, author of The Green and the Gray: The Irish in the Confederate States of America (see review here) and The Irish in the South 1815-1877. I will be speaking on my work on pension files, with a particular focus on both visualisation techniques and Civil War pensioners who returned to Ulster. Registration for the three days is $110 and is open to all- if you are interested in checking it out you can get further details on the program by clicking here. I hope some of you may be able to join me for what promises to be an extremely interesting few days!

Cobb’s and Kershaw’s Troops Behind the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg, by Allen Christian Redwood c. 1894 (Library of Congress)

Filed under: Events, Research, Update Tagged: Georgia Humanities Council, Irish American Civil War, Scotch-Irish Society of the USA, TRR Cobb House, UGA Department of History, ulster-American Heritage Symposium, University of Georgia, Willson Center

June 3, 2014

‘God Help Her’: The Emotional Impact of Cold Harbor, 3rd June 1864, On Two Irish Women

150 years ago today one of the bloodiest and costliest assaults of the American Civil War was underway at Cold Harbor. The Union attackers were slaughtered in droves. Few suffered as much as the men of Corcoran’s Irish Legion. Among their brigade were the Zouaves of the 164th New York Infantry, who suffered a staggering 154 casualties on 3rd June. Most of the deaths that day impacted on someone at home. Below are accounts from two Company B survivors of the 164th’s attack, provided to the wives of some of their less fortunate comrades. They bring forcefully home the emotional and social impact of that 3rd June in Virginia, 150 years ago. (1)

The Charge of the 164th New York at Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864 by Alfred Waud (Library of Congress)

Robert and Agnes Boyle were married in 1845 by the Reverend Mr. White in the Presbyterian Church at Portadown, Co. Armagh. They emigrated to Lockport, New York, where on 28th September 1862 Robert, at the age of 38, was enrolled as a First Lieutenant. It was a rank he still held on 3rd June 1864 at Cold Harbor. Agnes received the following letter relating to her husband’s fate on 18th March 1865:

Officer’s Hospital

Annapolis, Md. Mch 18 ’65

Mrs. Lieut Boyle.

Dear Madam,

I have received your letter of the 14th inquiring after your husbands will. In reply I will make the following statement.

Your husband was wounded and taken prisoner with me at Cold Harbor on the morning of the 3rd of June 1864 we were afterwards taken to Libby Prison Hospital in Richmond Va. where he died on the 1st of July 1864. I seen him every day untill he died. When the doctor tole me that there was no hope of his recovery I asked him how he intended to dispose of his property. He told me that he had a house and lot in Lockport and that it was yours also what money was due to him. He gave me his watch and told me to give it to you and to tell you that Capt. Burke owed him $5.00 Lieut. Lynch $5.00 and Lieut. Callanan $10.oo all of them belongs to the 164. Regt. N.Y.S.V. he told me how much he owed the sutler of the Regt. I told him not to mind that as the sutler would collect his bill from the War Department.

He said several times God help her (meaning you) I am sorry I have not more to leave her. I sent you his watch by Doctor Regan. If Capt. Murroney’s brother got the Captains watch you will find the key of your husbands watch on the Captains chain. It is a large gold key. He told me he lent it to the Captain before we left Sangsters Station and the Captain didn’t give it back to him. The Lieut. that Capt. Murroney gave his watch to would not give the key to your husband that is the reason you didn’t receive it with the watch.

Lieut. Boyle was severely wounded in the right hip. After he was some days in Hospital he took fever of which he died on the evening of the 1st July 1864. I was by his bedside when he died. He retained his senses to the last and died so quietly that you would think he was going to sleep. A head board marks his grave so that when we take Richmond you can have his remains taken home if you wish to do so.

By writing to these officers whose names I have given I know they will send you what money they owe to your husband and by making application to the War Department you can obtain his back pay also a pension.

Hoping that this statement will be satisfactory and if you wish for further information direct to the Regt. as I intend leaving here in a few days to join my Regt.

I am yours,

most Respectfully,

David J. Beattie

Direct

Capt. David J. Beattie

Co. I 164. N.Y.S.V.

2nd Brig. 2nd Division, 2nd Corps.

Petersburgh, Va. (2)

David Beattie had enlisted as a 27-year-old in August 1862. He had been wounded and captured in action at Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864 and mustered out with his Company on 15th July 1865. Captain Murroney was William Moroney, who had enlisted aged 27 in September 1862. He was wounded and captured at Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864, presumably while in possession of Lieutenant Boyle’s watch key. Moroney died of his wounds in Richmond on 20th June 1864. Of the men who owed money to Boyle, Timothy Burke and Stephen Callanan were mustered out with their Companys on 15th July 1865 and John Lynch was dismissed on 12th August 1864. Agnes received a pension for her husband’s sacrifice- she died in 1903. (3)

Patrick Byrne and Catherine Eagan also made their home in Lockport. They met and were married in the town’s Catholic Church by the Reverend McMullen on 6th September 1848. Their first daughter Mary was born on 15th June 1850, followed by Ann on the 27th March 1853, Catherine on the 21st February 1855 and finally John on 4th December 1857. Patrick enlisted on the 29th August 1862 at Lockport. It had initially been thought he had been captured in action on 3rd June, but this statement given by his comrade Daniel Connolly on 16th February 1865 revealed his true fate:

Daniel Connolly of Rochester City Hospital being duly sworn says that he is now an invalid in the said hospital in the City of Rochester N.Y. that this deponent was a Private of Company B of the 164 Regt. of N.Y. Vols at the Battle of Cold Harbor in the State of Virginia on the third day of June in the year 1864, that this deponent was wounded by a shell and lost a leg at said Battle and was compelled to lay upon said battlefield for about eight hours. That this deponent was well acquainted with Patrick Burns or Byrnes who was a Private of Company B of the 155 now 164 Regt N.Y. Vols, and that said patrick Burns was engaged at said Battle of Cold Harbor and said Burns was wounded at said Battle on said third day of June 1864 and lay but a short distance from this deponent. That this deponent conversed with said Burns on said Battlefield while he was wounded as said Battle. That the said Patrick Burns died on the said third day of June 1864 on said Battlefield. That this deponent saw said Burns after he was dead. That the said Burns died in consequence of a wound received by the enemy at said Battle, and that said Burns was in the line of his duty as a soldier when he was wounded by the enemy as aforesaid. That said Burns was wounded by a rifle ball in the breast. That this deponent has no interest in the application of Mrs. Catherine Burns for a pension on account of the death of her said husband. (4)

Daniel Connolly had enlisted as a 21-year-old on 1st September 1862. A Corporal when he was wounded and captured at Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864, he was still absent in hospital at the muster out of his company in July 1865. Catherine received her pension for Daniel’s service- she died on 10th September 1904. These are just two of the stories -from a single company- relating to events at Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864. One North Carolinian who had repulsed the attack of the 164th New York that day remembered that so many had fallen in front of their works ‘that one could have walked on their bodies its whole extent.’ The personal stories behind the majority of these Irishmen will never be known. (5)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Rhea 2002: 336; (2) Robert Boyle Widow’s Pension File, New York Adjutant General Report; (3) Ibid.; (4) Patrick Byrne’s Widow’s Pension File, New York Adjutant General Report; (5) Ibid.; Rhea 2002: 336;

References & Further Reading

Robert Boyle Widow’s Pension File WC49639

Patrick Byrne Widow’s Pension File WC66941

New York Adjutant General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General for the State of New York.

Rhea, Gordon 2002. Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee May 26- June 3, 1864.

Richmond National Battlefield Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Cold Harbor Page

Filed under: 164th New York, Armagh, Battle of Cold Harbor, Corcoran's Irish Legion Tagged: 164th New York Infantry, Armagh Veterans, Battle of Cold Harbor, Civil War Pensions, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Irish American Civil War, Irish American Civil War Veterans, Soldiers Last Letters

June 2, 2014

‘Tell Him I Am A Soger’: Lyrics, Loyalty and Family in the Letters of an Irish Brigade Faugh

Patrick Kelly emigrated from Co. Galway to Boston with his parents. In 1861 he enlisted in the 28th Massachusetts Infantry, an Irish regiment that ultimately served in the Irish Brigade. During his service he wrote frequently to his parents at home in Boston; the letters portray a young man who was a lover of music and reading, a volunteer soldier fiercely proud of his regiment and its Irish affiliations. Thanks to work currently underway at the National Archives to scan pension files*, it is now possible for us to hear the voice of this young Galwegian across 150 years of history. (1)

Martin and Mary Kelly were married in Ballinasloe, Co. Galway on 29th November 1840. Their son Patrick was born in Ireland soon afterwards, and was followed by at least one younger brother, John. The family made their home in Boston’s 7th Ward and in the 1860s lived at 3 Sturgis Place in the city. By 1860 Patrick had followed the path many of his countrymen had taken in Massachusetts, entering the leather working trade by becoming an apprentice shoemaker. His parents would come to rely on him for support; Patrick’s father Martin, a fruit dealer by trade, had suffered an injury that left him with a severe limp. Although only in his early forties by the outbreak of war, Martin was restricted to selling apples on the street during fine weather- pain in his leg brought on by inclement conditions drove him inside for much of the year. (2)

With the outbreak of war Patrick had his first opportunity to contribute a meaningful amount of money to his parents upkeep (having been an apprentice prior to 1861). He did this by enlisting in the army. Clearly he was also eager to do his bit to preserve the Union. Patrick enlisted in the army on 16th November 1861- although he was recorded as 22-years-of-age, he was undoubtedly somewhat younger. On 13th December 1861 Patrick Kelly mustered into Federal service as part of Company G, 28th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. Less than a month later he was writing to his parents from the regiment’s training camp at Fort Columbus, New York. (3)

An aerial view of Fort Jay, formerly Fort Columbus, where Patrick Kelly was training with the 28th Massachusetts Infantry (Library of Congress)

Head Quarters 28th Regim.

Fort Columbus Jan 15th ’61 [sic.]

Dear Parents,

I now take the opportunity off letting you know that I arrived safe at my port of destination and had as pleasant a pasage as circumstances allowed. We got payed off the day after coming to Fort Columbus. I got $19.50 cts. we did not get payed for this month at all. So I enclose $15 in this letter as that is as much as I can send now. Next I [will] send all my pay as I will not need it after this. This time I owed the sutler 1.25 and then we were asked to give as much as we pleased to the Captain and the Lieutenants to buy revolvers so I gave 1$ as well as the rest. We have easy times in our knew quarters but we are poorly accomadated as our quarters are too small but we expect to be better fixed by and by. The Colonel said when we came here and said he would bring his men back to Boston again so we expect better room, we are too crowded that[s] all the matter with us. We are in good has [health?] an appetite that would eat a horse. Jimy Naphin is the Corporal off our mess Jim has to do all the jawing for his mess. He is the best one in the place we have plenty and [in] our mess when others are fighting for theirs. Time is precious at present while I write I send my love to John and tell him I am a soger. Tell him I may be home before him. Send my best respects to Mr and Mrs Burns and the children and tell Lary O Gaff I will shoot Jeff Davis on a sour apple tell send my bests respects to Mrs [and] Mr Guinen and to Hubert and to all enquiring friends no more at present from your affectionate son,

Patrick Kelly.

Direct your letter to Patrick Kelly Compy G 28th Regiment

Fort Columbus NY (4)

‘Jimy Naphin’ was a close friend of Patrick’s in the company. Recorded as ‘James Naphan’, he enlisted as a 22-year-old shoemaker on 3rd October 1861, mustering in on 13th December 1861. He was discharged on 18th December 1864 and later served in the 2nd Battery Massachusetts Light Artillery where he is listed as ‘James Maphin.’ The Massachusetts State Census of 1865 shows that the Guinens lived beside the Kellys. In 1865 the family included Stephen, a 47-year-old tailor, his 40-year-old wife Mary and their children Hubert, a 17-year-old shoemaker and Elizabeth, a 20-year-old with no stated profession. It is unclear if ‘Larry O’Gaff’ refers to an actual individual or a song- it was the name of a popular comic tune at the time that charts Larry’s adventures working in England and during the Napoleonic Wars- for a sample of some of the lyrics see here. The reference to shooting ‘Jeff Davis on a sour apple’ refers to the lyrics ‘We’ll hang Jeff Davis from a Sour Apple Tree’ which were often sung as a verse in the famous song ‘John Brown’s Body’ (see the lyrics of that version here). (5)

Jefferson Davis shown hanging from a ‘Sour Apple Tree’ in Harper’s Weekly (Library of Congress)

Head Quarters 28th Regim,

Fort Columbus N.Y. Januy. 19 1862

Dear Parents,

I received the letter you wrote and it gave me great pleasure to know that you received it. I hope that you are better off that cold you had if not before now I hope you will be. I am still in good health at present you asked me how long we would be on the island, thats a thing I can’t say but I don’t think we will leave it before April so Pat Hoben says, he is one off our teamsters. You need not be in a wory about coming out to see me i’ll be back in Boston after the war with the help off God. So you need not [be] foolish spending money. The next time you write let me know if you receive any money from the State I don’t need much at present but you can send that box iff you want to and I should like you would [send] a guitar and some song books if you can get the guitar cheap. I will send $20 home the first off March iff we get payed. We have good easy times at present nothing to do and plenty to eat. I tell you what it is a fine thing to be a Faugh for they are bound to clear the way. Jeff Davis clear the way as the crazy sargent sung the other night. The fire that blazed from Emmets Patriotic eye shall lead us to our victory. So said the bard when Cass left for the seat off war. I can’t think off anything else only that [the] boys are all well. O’Brien and Kileen and Jimmy sends their best respects to you send my love to Mr and Mrs Gafney and to all the neigbors and tell Tom I won’t get shot in the back.

No more at present from your ever affectionate Son,

Patrick Kelly.

Just as I was writing this letter the Pilot you sent came in.

You do not direct the letter right our Company is not H it is G then direct it to Compy G. (6)

24-year-old Pat Hoben enlisted on 7th December 1861 when he was working as a teamster. Mustered into service on 13th December 1861, he was killed in action on 30th August 1862 at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Patrick O’Brien was a 24-year-old shoemaker who enlisted on 1st October 1861 and mustered into service on 13th December 1861. He died of disease at Beaufort, South Carolina on 8th July 1862. Patrick Killian had enlisted as a 30-year-old shoemaker on 30th December 1861, he was discharged for disability on 29th June 1863. The reference to State aid is the financial support promised by Massachusetts to the dependent family’s of those who had enlisted. The reference to being a ‘Faugh’ relates to the motto ‘Faugh A Ballagh’ meaning ‘Clear the Way.’ Originally the motto of the Royal Irish Fusiliers, it was used in reference to numerous Irish regiments and was also adopted by the 28th Massachusetts Infantry. The song sung by the crazy Sergeant containing the lyrics ‘Jeff Davis Clear the Way’ and ‘The fire that blazed from Emmets Patriotic Eye’ is the song Fág an Bealac which was written for the 28th Massachusetts. You can listen to a version of this song below. The Cass referred to in the letter is Colonel Thomas Cass, commander of the first Irish Massachusetts regiment raised, the 9th Infantry. The Boston Pilot was the leading Irish-American newspaper in the city. (7)

A version of the song Fág an Bealac that Patrick Kelly remembered being sung in the camp of the 28th Massachusetts in early 1862.

Hilton Head

South Carolina

Feb 26th 1862

Dear Parents,

I now take my pen in hand to let ye know that I am in good health and arrived safe at my port of destination we have good health and good weather, we were 8 days on the boat let me know if you get State aid and how much. I want for nothing we expect to get payed next week I have very little time to write, this this climate agrees with me. Farewell for a while no more at present from your Aff. Son,

Patrick Kelly.

Direct your letter to me Hilton Head, South Carolina, 28 Regt., Company G (8)

Hilton Head May 1st 1862

Dear Parents,

I now take the opportunity of writing to you hoping these few lines will find you in good health. I send home 15$ to you ,the State treasurer will notify you of it I have not much time to write now but I am in good health so is all the boys. I would like your likeness mother, remember me to all the neighbors. No more at present from your Aff. Son,

Patrick Kelly. (9)

The Army Wharf at Hilton Head, South Carolina as it appeared in 1862 (Library of Congress)

July 18th 1862

New Port News Virginia

Dear Parents,

I received your letter which gave me great pleasure to hear from you. I got your likeness the same day I got the letter and I got the other things you sent. When we came to Hilton Head after the battle the Regt got payed on the way here and I went and put mine in a tin box I had in my packed [sic.]. I was waiting for the crowd to clear away so that I could give it to the Major to send home before any temptation might cross me on land. Well I went aloft on the ships mast and sat down their [sic.], well I was sitting their about 5 minits when I took out my pocket handkerchief to wipe my face never thinking of the box, when I suppose I puled it out and that was the last I seen of the $26 since then. I know no one I keep by myself. Let me know if you got the 15$ I sent home in a letter. I have no more time to write now. No more at present,

From your son,

Patrick Kelly. (10)

The battle that Patrick is referring to is Secessionville, South Carolina (you can read about it here). He wrote this on the day the 28th docked at Newport News on their return from the Deep South.

Camp 28th Regt. Mass. Vol. Irish Brigade near Falmouth Va. Nov. 27th 1862

Dear Parents,

I now take the opportunity of writing to you hoping to find you in good health as these few lines leaves me in at present thank God. I received your letter and although I am hard up for writing material I cannot send for them now, for I would never get them for we are always on the march. We now lay opposite Fredericksburg, the rebels hold the city and we are on the other side. We don’t know the minuet [sic.] we will be called on to cross the river or start off some way else. We joined the Irish Brigade about one week ago, the Brigade gets as much beef as the [w]hole corps. Faugh a Ballagh is the war cry and no turn back. Of course we will cross the river first but no mater trust to Irelands bold Brigade to clear the road. We did not get payed yet I think we soon will. To day is thanksgiving I hope we will be in winters quarters before Christmas so that you can send me a Christmas dinner. Patrick Killeen is tip top he is driving a team now and gets 25 cts a day extra but he will soon be back again, for we left the 9th army corps so all the detailed men had to come back. Me and him slept together and fought side by side and he never got a scratch. Mike Ney was taken prisoner at Bull Run. The first voley that was fired at us he ran away and hid in the woods so when the army left he was caught, I don’t know how true well thats what some of the boys said. He is now at Camp Chase Ohio. The last time we were here we left our knapsacks behind us so we never got one of them and I left Longfellows works in the knapsack. The government would not make the articles good except the overcoat. I want Father the next letter he writes to write off the song called Mary Le More I want to learn it. I have the same prayer book I carried from home I will carry that home safe. If their is any signs of going in to winter quarters I will let you know. Let me know how times is and how dear is things I will send home 45$ when I get payed that is 4 months pay if they dont pay us untill January I will send home 70$ let me know if you got the State aid yet.

Give my love to all the neighbors,

Direct your letter to me Compy G 28th Regt Mass Vol

Washington D.C.

2d Army Corps

No more at present from

Your Aff. Son,

Patrick Kelly. (11)

The 28th Massachusetts had originally been intended to form one of the Irish Brigade’s regiments from the outset, but in the end did not join Meagher’s formation until November 1862. Mike Ney had enlisted as a 30-year-old teamster on 4th November 1861 and was mustered into service on 13th December 1861. He was reported missing at the Battle of Chantilly, Virginia on 1st September 1862. Later he would be captured at Bristoe Station, Virginia on 14th October 1863, being exchanged on 26th November 1864. He mustered out of service on 19th December 1864. Soldiers were ordered to leave their knapsacks behind upon going into action, and often lost everything in them as a result. The book Patrick mourns was the works of famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The song ‘Mary Le More’ was an Irish eviction song about an encounter with a mad woman- you can read the lyrics of the song here. (12)

Patrick was writing from the Union army camp at Falmouth Virginia, probably from quarters not dissimilar to these of the 110th Pennsylvania Infantry (Library of Congress)

Camp near Falmouth Va Jan 24th 1863

Dear Parents,

I now take the opportunity of writing to you hopping to find ye in good health as this leaves me in at present thanks be to God for his mercy. I received the letter you sent me and I sent you $40 by the paymaster he will give it to the adams express and they will forward it to you. I did not pay the express as the paymaster would not take any it is in an envelope. I am very sory for Lizzie Murray the 37th N.Y. ain’t near us so me nor Terry Mitchell can’t see Kervan?. Terry wants to know if it was in Boston you seen Mike Murray. Well I have to write a letter to Maggie Burns so I will finish by sending all the neighbors my best respects.

No more at present,

From your Aff. Son,

Patrick Kelly. (13)

The Adams Express Company was a common way of sending money home during the Civil War. Terry Mitchell had enlisted and mustered on 5th January 1862 at the age of 38, he had been a carpenter before the war. He was promoted Corporal in May/June 1862, Sergeant on 1st January 1863 and was mustered out on 19th December 1864. The 37th New York were another Irish regiment, the ‘Irish Rifles’. It is unclear who is being referred to here. (14)

Falmouth Va. April 27th 1863

Dear Parents,

I received the letter which ye sent me I am glad to hear that ye are all well as these few lines leaves me in at present thanks be to God for his mercy to me. I sent $30 home by the priest you will get by Adams ex. you muse excuse me for not sending home as much as I did before, but our clothing money for the year was stopped. What was stoped from me was nothing in comparison to others and we raised a subscription for the relief of Ireland and sent it to Donahoe. Killeen is gone to the Lincoln hospital Washington. 4 Regts of the Brigade is gone to Kelly Ford to relieve some of the 5th Corps and our Regt is gone down to the river to do picket duty I think we will go to the rear yet but if we don’t we are able to do our duty in the field as we have always done it. Yes I get [got] the papers ye sent I hope this summer will end the war I will go see Mr Murphy in Co. I but he is on picket now. So I have no more at present only give my best respects to all the neighbors.

No more at present,

From your Aff. Son,

Patrick Kelly.

PS I sent my likeness yeasterday. (15)

The Mr. Murphy is possibly Martin Murphy, who enlisted as a 42-year-old teamster on 26th November 1861. Wounded at Fredericksburg he was discharged for wounds on 2nd May 1863. The Relief Fund efforts of 1863 have been the topic of numerous posts on the site and you can read more about them here.

Sketch of an engagement at Kelly’s Ford in November 1863. Patrick Kelly would be on picket duty here the following month with the 28th Massachusetts (Library of Congress)

Patrick Kelly was a Corporal at the Battle of Fredericksburg, and although he makes no mention of it in these letters he was reportedly wounded there. The young Galwegian presumably fought at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg with the 28th Massachusetts, but his promise to send his likeness to his family is the last letter in his file. A few months later, on 3rd December 1863, Patrick was on picket duty at Kelly’s Ford when he was shot and killed. Tragically it would appear that his brother John had predeceased him. These letters were included in his mother Mary’s pension application file in 1864, in order to prove that Patrick had regularly sent her money. She received a pension until her death in 1894- her husband Martin had predeceased her. The letters she saved now provide an insight into the character and experiences of her young son during the conflict.

Note re Letter Transcription: I have kept the spelling in the letters largely as it appears in the originals, with some slight adjustments to avoid any confusion on the part of the reader. Punctuation and paragraphs were largely absent from the originals and in most instances have been added for ease of reading by a modern audience.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Patrick Kelly Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid.; Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines: 242; (4) Patrick Kelly’s Widow’s Pension File; (5) Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines: 243, 1865 Massachusetts Census, Williams 1996: 73; (6) Patrick Kelly’s Widow’s Pension File, Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines: 241-43; (8) Patrick Kelly’s Widow’s Pension File; (9) Ibid.; (10) Ibid.; (11) Ibid.; (12) Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines: 243; (13) Patrick Kelly’s Widow’s Pension File; (14) Patrick Kelly’s Widow’s Pension File; (15) (16) Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines: 257;

References

Patrick Kelley Widow’s Pension File WC22521

Massachusetts State Census 1865

Massachusetts Adjutant General’s Office 1932. Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War. Volume 3.

Williams, W.H.A. 1996. ‘Twas Only an Irishman’s Dream: The Image of Ireland and the Irish in Popular American Song Lyrics, 1800-1920.

Filed under: 28th Massachusetts, Galway, Irish Brigade, Massachusetts Tagged: 28th Massachusetts, Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Secessionville, Civil War Pensions, Galway Veteran, Ireland American Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade

May 31, 2014

Visualising the Impact of the American Civil War in Ireland with Palladio

I have been building a database of information relating to the 219 U.S. military pensioners who were recorded as living in Ireland in 1883. These pensioners and their families have been the topic of numerous posts on the site and I hope in the future will form the basis for a book recounting their stories. The group represents an ideal sample with which to attempt to ‘visualise’ the impact of the American Civil War on Irish people. Recently I took to the web-based platform Palladio, developed by the Humanities & Design Research Lab at the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis, Stanford University, in order to explore the types of visualisations possible with this data.

Palladio was developed for the visualisation of complex, multi-dimensional data. It is free to use- all that is required is having the information to upload and the time to prepare it appropriately. For that purpose I developed three tables based around the Irish pensions. The information contained within the tables was gleaned from a variety of sources. Details on which pensions were being paid in Ireland was taken from the 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll; this was supplemented with additional data drawn from the marvellous online resources that have been made available by the National Archives via the Fold3 website. These included the Pension Numerical Index, the Civil War and Later Veterans Pension Index, the Civil War “Widow’s Pensions”, Navy Widows Certificates and Navy Survivors Certificates. In addition to gathering baseline data on each of the 219 pensioners a further 65 pension files were examined in detail, revealing further details on aspects of the pensioners life, such as marriage details and death location.

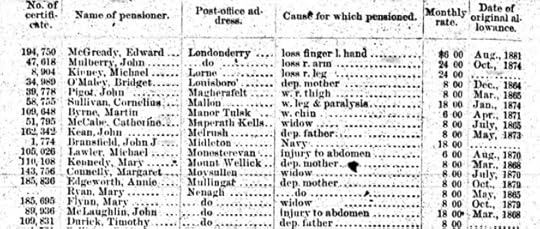

An extract from the 1883 Pensioners on the Roll which shows how the information was presented in that list

The first table I prepared contained details of the pensions themselves and (where the information was available) included the name of the pension recipient, the name of the veteran, the state for which they served if in a volunteer unit, the veteran’s place of death, the veteran’s cause of death, the year of the veteran’s death, the post office location in Ireland where the pension was received, the year of death of the pensioner, marriage location, marriage year, U.S. habitation location of the pensioner and the year in which the pension was awarded.

The second table contained the full name of every pensioner and veteran, and their relationship. All of the Irish pensions were being claimed by one of four groups- the veteran themselves, the widow of a veteran, the dependent mother of a veteran or the dependent father of a veteran. The final table listed the locations in the United States and Ireland associated with the pension, with coordinates for each added using Google Maps. These three tables were then uploaded to Palladio and linked together, creating an opportunity to interrogate the data visually. To gain the full benefit of Palladio you need to upload the data and view it at their website in realtime. I hope to make the tables readily accessible in the future- in the meantime if any reader is particularly interested in viewing the full results themselves, I would be happy to make a copy of the .json Palladio file for the project available, so you can view it and interrogate it for yourself at the Palladio site. In order to bring a flavour of its use to readers of the blog, I have captured a number of screenshots of the visualisations from Palladio to share here (Note: to see the images at full size click directly on them).

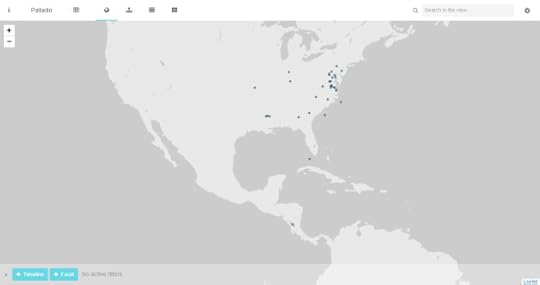

The post offices in Ireland where U.S- military pensions were being collected in 1883. The points are scaled to highlight areas with multiple pensioners, notably Dublin, Belfast and Londonderry. What is apparent is the coverage of the entire country. Some of the pensions were being collected for pre-Civil War and post Civil War service, but the vast majority relate to service between 1861-65. (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

In the majority of cases it was possible to discover the unit in which a veteran had served. For those not in regular army or naval service this allowed for a ‘state of service’ to be assigned. I selected the capital of each state as the representative point for illustrative purposes in the visualisation. This map shows these different states, with the points scaled to highlight states which had multiple individuals. Unsurprisingly New York dominates. (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

The locations where veterans died. Some of these locations are battlefields, some hospitals, some POW camps. Note that one (a young man from Tralee, Co. Kerry) died in Nicaragua, while others died at sea off the Carolinas. Each of these deaths related directly to the award of a pension across the Atlantic in Ireland (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

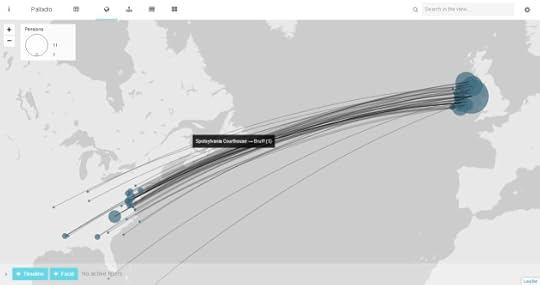

The long arm of war. This visualisation links the death locations of servicemen with the localities where pensions were received in Ireland as a result. This visualisation shows the global impact of the American Civil War. It is also striking how Ireland ‘disappears’ under a sea of dots. Only 219 pensions were being claimed in Ireland in 1883, indicating that few people came back after emigration. When one considers that well in excess of 150,000 Irishmen served the Union in the war (with a further 20,000 in the Confederate military), the true figures of tens of thousands of Irishmen from up and down the island who lost their lives is difficult to comprehend. Each line carries behind it the information relating to specific soldiers- that highlighted is the link between the death of a young man at the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse 150 years ago and the pension his mother received as a result in Bruff, Co. Limerick (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

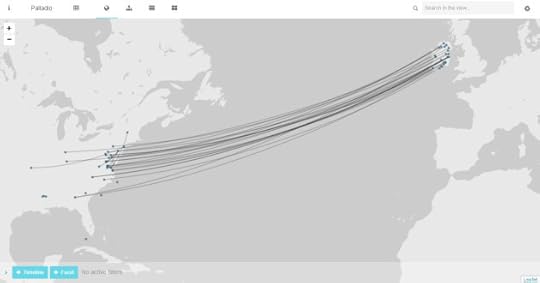

Till Death Do Us Part. This visualisation links the locations where couples were married in Ireland (or in some cases the United States), usually in the 1840s or 1850s, with the locations where the man died during the American Civil War. Widows often recorded this information in their Widow’s pension applications. It charts visually the start and end of their time together as husband and wife, and is another reminder of the long reach of the American Civil War (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

The March to War. The state for which the veteran served linked to the location in North America where they died. The highlighted link is a man who served in a New York regiment, who died as a POW in Camp Lawton, Georgia. This event later resulted in the award of a pension in Ireland (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

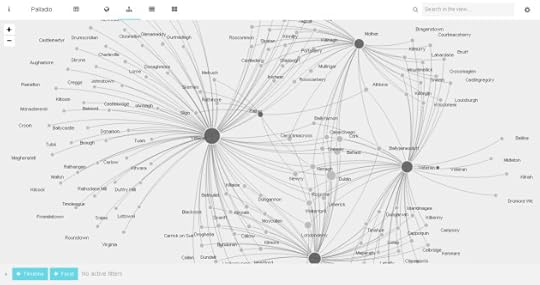

Palladio also allows information to be visualised in other ways. This example is a portion of a diagram which links each Post Office where pensions were received in Ireland with the relationship the pensioner had to the veteran (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

It is similarly possible to look at just the pensioners from one location- this graph shows the people who were in receipt of U.S. military pensions in Dublin in 1883 (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

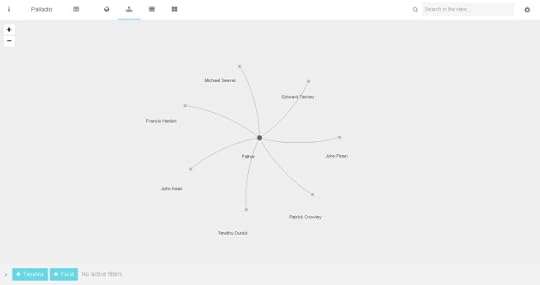

Fathers. This graph shows the men identified as receiving pensions as dependent fathers due to the loss of their sons, Ireland, 1883 (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

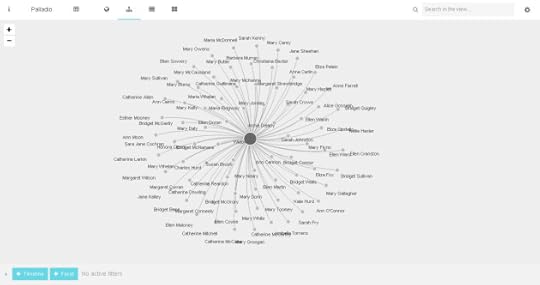

Mothers. The dependent mothers who had lost sons in United States service, for which they received pensions in Ireland, 1883. Although some had spent time in the United States, many of the dependent parents had never been outside of Ireland, yet were nonetheless dramatically impacted by the Civil War. (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

Widows. The widows who were in receipt of U.S. pensions in Ireland, 1883. Behind the names lie a multitude of stories; women who had been abandoned by husbands who emigrated, women who’s husbands had gone ahead to the United States to ‘clear the way’ for their family only to die before they could be reunited, women who had made their home in the United States but who were forced to return with their children to Ireland and the support of family after their husband’s death (Damian Shiels/Palladio)

The visualisation of data in this form allows us to see the impact of the American Civil War in different ways, beyond simply casualty figures from the battlefield. It is also a stark reminder that the misery the war inflicted was not restricted to the United States. Similarly, it highlights that the benefits and supports of the pension system introduced in 1862 could be felt thousands of miles away, even by people who had never set foot in America. For me, seeing the tendrils of impact spread far and wide, touching so many individuals and places- based on just 219 pensioners- tells us much about the colossal effect of the war on the hundreds of thousands of Irish emigrants who experienced it.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

Filed under: Pensioners in Ireland, Research, Resources Tagged: American Civil War Pensions, Digital Humanities, Ireland Military Pensions, Irish American Civil War, List of Pensioners on the Roll, Palladio Stanford, Visualisations, Widows Pension File