Damian Shiels's Blog, page 48

January 17, 2014

Looking into the Face of a Dying Irish Soldier

Around late April or early May of 1865 a photographer in Harewood Hospital, Washington D.C. exposed a photograph of a wounded Union soldier. The man, who still wore the beard he favoured on campaign, had been shot through the left shoulder during the fighting around Petersburg. His name was John Ruddy, an Irish farmer and sometime laborer who had been in the army for less than a month when he was hit. The images of Ruddy are testament to the realities of combat in the American Civil War. The effect of wounds such as these could also be long-lasting; the damage caused by the Minié ball that shattered Ruddy’s arm in 1865 would eventually kill him- three years later. (1)

Photograph of John Ruddy taken at Harewood Hospital following his wounding at the South Side Railroad on 2nd April 1865 (National Museum of Health and Medicine)

John Ruddy lived in Albany’s First Ward, making his home at 20 Clinton Street. He lived there with his wife Ann; she had also been born in Ireland and was already once widowed, having been married to Hugh Quinn with whom she had two sons. John and Ann married at St. John’s Catholic Church, Albany on the 6th October 1857. A daughter, Alice, followed on 5th November 1859. The 1860 Census records the family under the name ‘Rhody’. John, at that time working as a laborer, is listed with Ann, her two boys Bernard (10) and Thomas (8), and Alice (2). (2)

Photograph of John Ruddy taken following his operation at Harewood Hospital in 1865 (National Museum of Health and Medicine)

John enlisted in the Union army on 7th March 1865, perhaps motivated by economic factors and the large bounty then available for signing up. In his early thirties, he was a man of above average height, described as being a 6 foot tall former farmer with a light complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. He became a Private in Company A of the 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade, and joined the regiment for the latter stages of the Petersburg Campaign. He was with the 63rd when it was ordered forward as part of the general Union assault of 2nd April 1865. The attack, which ultimately led to the capture of Petersburg and fall of Richmond, required the 63rd New York to advance against the South Side Railroad and capture it. Captain William Terwilliger, who commanded the regiment that day, describing their movements:

At 1 a.m. April 2 moved to left some three miles to join Sheridan’s cavalry. At 7 a.m. resumed the march, moving to the right to White Oak road, where we formed line of battle and moved upon the enemy’s works, finding them evacuated; continuing the march by the flank two miles and a half, reformed line of battle, and participated with the brigade in three charges upon the enemy’s defenses of the South Side Railroad. The losses in this engagement were, 1 commissioned officer killed, 1 commissioned officer and 6 enlisted men wounded, and 2 enlisted men missing in action. (3)

Surgeons and Hospital Stewards at Harewood Hospital, Washington D.C. (Library of Congress)

One of the six enlisted men wounded was John Ruddy. During one of the charges a rebel bullet had struck him in the left shoulder, completely shattering the head of his humerus before passing through his body an exiting his back through the scapula. He was quickly taken to Harewood Hospital in Washington D.C. where an operation removed a portion of his humerus but saved his arm, an achievement that was recorded photographically. He remained at Harewood until he was discharged from the service on 30th July, 1865. (4)

A General view of Harewood Hospital in Washington D.C. where John Ruddy was treated (Library of Congress)

John returned home to Albany, having seemingly come through his brush with death. Although he kept his arm, it was completely useless and he was forced to rely on a modest pension. Given the extent of his disability he decided to seek an increase; he was even able to produce one of the photographs of his wound taken in Harewood, an image that remains part of his pension file to this day. (5)

The image of John Ruddy that he provided when seeking an increase in his pension (Fold3)

Little did John realise that the bullet that struck him in the closing days of the war would ultimately prove fatal. It transpired that the ball had also passed through the upper part of his left lung on its passage through his body. As the months passed he began a long deterioration in health, which his doctor described as the ‘wasting away of his system’. On the 3rd June 1868 John Ruddy died, widowing his wife Ann for the second time and leaving behind an eight-year-old daughter. The photos of him taken in 1865, with what would prove to be his mortal wound, offer a rare opportunity to look into the face of one of the thousands of Irish emigrants who died in the American Civil War. (6)

John Ruddy, like many other Irish emigrants, was illiterate. Here is his mark on one of his pension applications (Fold3)

* Special thanks to Brendan Hamilton for his assistance in tracking down the source for the John Ruddy images.

(1) Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid., 1860 Federal Census; (3) Widow’s Pension File, Official Records: 728; (4) Widow’s Pension File; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid.;

References

1860 Us Federal Census

John Ruddy Civil War Widow’s Pension File WC117333

New York Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901.

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 46 (Part 1). Report of Capt. William H. Terwilliger, Sixty-third New York Infantry.

National Museum of Health and Medicine Flickr Page

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Petersburg, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Albany Irish, CIvil War Medical Photographs, Harewood Hospital, Irish American Civil War, Petersburg Campaign, South Side Railroad

January 11, 2014

Mapping Death in the American Civil War

I have been experimenting recently with different ways of visualizing the impact of the American Civil War. I am interested in how we can combine data recorded in the 19th century with some of the new digital tools available, in an effort to find new ways of engaging with this history and potentially reveal further insights into the war’s consequences and cost. Taking the 63rd New York Infantry of the Irish Brigade as a Case Study, I have been examining ways to visualize a regiment’s experience of the conflict.

Using the roster information of the 63rd from the New York Adjutant General’s report, I first exported the information on each man into a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. It is my intention in the long-term to use more sophisticated database tools, but in these early stages I was keen to find an easy to use program that converted the roster into interrogatable data. The rosters record 1,528 men as having served in the 63rd, with details that include information on aspects such as age at enlistment, date of enlistment as well as aspects such as desertion, wounding, death and discharge.

How then to map this information? For example, is it possible to visualize where the men of the 63rd New York encountered risk of injury and death? The rosters of the 63rd record instances of woundings or death in the regiment a total of 578 times. On 546 occasions this information is accompanied by location information. I decided to marry this data with latitude and longitude coordinates and place it in Google Fusion Tables. Unfortunately WordPress does not currently support embedding Fusion Table maps, so instead I have included some screenshots and supplied links to the full maps on the Google Fusion site.

The first map shows the different locations on the United States east coast where men of the 63rd New York were wounded or died. Some of these locations are battlefields, some the sites of hospitals, while others are Prisoner of War camps. To see the full version click here.

Screenshot of Google Fusion Table for 63rd New York, showing locations where members of the regiment died and were wounded between 1861 and 1865

A detailed view of the area of Virginia, Maryland and around Washington D.C. highlights costly battlefields for the 63rd, such as Antietam, Fredericksburg and The Wilderness, as well as the fighting further south associated with engagements of the Seven Days and at Cold Harbor and Petersburg. Important rear echelon areas such as Alexandria, Washington and Baltimore are also revealed.

Screenshot of Google Fusion Table for 63rd New York, detail of locations in Virginia, Maryland and Washington D.C. where members of the regiment died or were wounded

Although this mapping technique shows the different locations where men were wounded or died, it does not reveal the intensity of their experience at different locations. Using Google Fusion’s Heat Map function, areas where higher numbers of men died or were wounded are scaled by size and light intensity. The Heat Map scale moves from green to red, with the latter colour representing sites with the highest numbers of casualties. Looking at a satellite view of the eastern seaboard the parts of Virginia traversed by the Army of the Potomac during the war are immediately apparent; the green spots in North Carolina and Georgia showing deaths at Salisbury and Andersonville. To see the full version click here.

Screenshot of Google Fusion Table Heat Map, showing locations where members of the 63rd New York died or were wounded between 1861 and 1865, highlighting the intensity of losses in different locations

The regiment’s ordeal at Antietam on 17th September 1862 was far and away their worst experience of the war, when it sustained 202 casualties (183 of whom are recorded in the roster). Many men who were wounded here later died at Frederick, Maryland. A closer view of the Virginia, Maryland, Washington D.C. and southern Pennsylvania area clearly illustrates just how intense the 63rd’s losses were at Antietam, which is an intense red. Gettysburg is faintly visible across the state line in Pennsylvania, as are the battlefields which proved costliest for the regiment- Fredericksburg, The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and around Petersburg. The many who survived long enough to be removed from the field but who subsequently died are represented by the concentrations in cities such as Frederick, Washington D.C. and Alexandria.

Screenshot of Google Fusion Table Heat Map, showing detail of Virginia, Maryland, Washington D.C. and southern Pennsylvania, and highlighting the major battles (notably Antietam) where the 63rd New York suffered significant casualties

I have also mapped the locations where men from the 63rd New York were discharged as a result of wounds and disability, which you can view here. Many other types of data can be mapped in a similar fashion. There are numerous refinements to be carried out in my visualization efforts, but they do offer interesting potential for examining different aspects of the Irish experience of the conflict. Visualizations of data relating to the war and it’s consequences are being used to an ever greater degree; the University of Richmond’s excellent Visualizing Emancipation site is one fine example. When used correctly they can be powerful educational tools- hopefully in the future I will be able to bring you many more that are tailored to the Irish experience.

References

New York Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901.

Filed under: 63rd New York, Irish Brigade, Research Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Adjutant General Reports, American Civil War Casualties, Data Visualization, Digital Humanities, Google Fusion Tables, Irish American Civil War, Mapping the Civil War

January 5, 2014

How ‘Irish’ was Phil Sheridan?

I have had the good fortune to speak about the Irish in the American Civil War in many different parts of Ireland. When it comes to question-time, there is one topic that is almost always guaranteed to come up- General Phil Sheridan. This is unsurprising given his leading role as one of the key players in the conflict. Questions usually revolve around where Little Phil was born, but are there more interesting aspects of Sheridan’s ‘Irishness’ to explore?

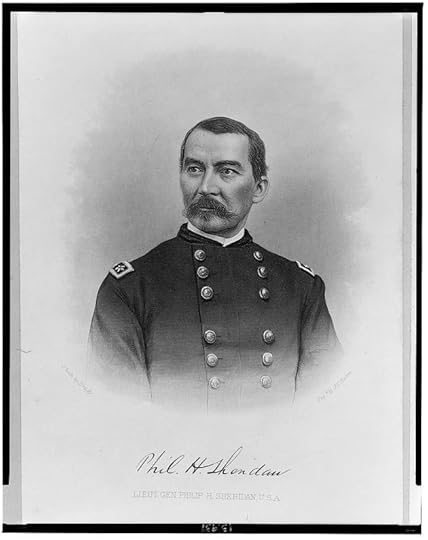

Lieutenant-General Phil Sheridan (Library of Congress)

There has been much debate about Sheridan’s birthplace, with historians divided over the issue. Sheridan himself claimed to have been born in Albany, while others have placed his birthplace at the family residence of Killenkere, Co. Cavan, or aboard the boat that took the Sheridan family to the United States. It seems unlikely that this question will ever be definitively answered. However, I think a focus on the nativity of Sheridan masks a more interesting question- how ‘Irish’ did he consider himself to be?

Regardless of Phil Sheridan’s birthplace, he was undoubtedly of Irish stock. But how much did he associate with the country of his family’s emigration, and what were his thoughts about Ireland and Irish-America? The majority of biographies I have read on Sheridan fail to address this question or to examine his place in Irish-America. Undoubtedly the loss of some of Sheridan’s personal papers in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire has hindered opportunities to examine this aspect of Sheridan’s life, but it does appear that Phil Sheridan regarded himself (and wanted to be regarded) as unambiguously American. This was in an era when many Irish-Americans had no difficulty in expressing a dual allegiance both to the cause of the United States and Ireland, even when they had been born in America. Examples of this include New York born James A. Mulligan, who led ‘Mulligan’s Irish Brigade’, and Peter Welsh of the 28th Massachusetts, who although born on Prince Edward Island imbued his letters with such a sense of ‘Irishness’ that he is sometimes erroneously referred to as Irish-born.

Phil Sheridan appears to have had little interest in portraying himself as an Irish-American. There may have been many reasons for this, such as an attempt to avoid nativist prejudice, or the lack of a political need to identify closely with the Irish community (as he was a career soldier rather than a politician). In his Personal Memoirs, published in 1888, he deals with his Irish ancestry in a single paragraph and elects not to make significant further reference to his ‘Irishness’. This is despite the fact that it must have been a feature of his childhood- for example he was taught by ‘an old time Irish master’ in his village school in Ohio. In later life, Sheridan visited Europe in 1870-1, where he observed the Franco-Prussian war before taking an opportunity to visit England, Scotland and, for the first time, Ireland. His description of his time in the land of his ancestry is dealt with in his memoirs with a single sentence: ‘My journeys through these countries [England, Ireland and Scotland] were full of pleasure and instruction, but as nothing I saw or did was markedly different from what has been so often described by others, I will save the reader this part of my experience.’ (1)

When Sheridan was in Ireland in 1871 he carried out an interview with a Dublin based correspondent of the New York Herald. Sheridan, who was staying in Dublin’s Shelbourne Hotel, was asked about Ireland:

Correspondent: This, I presume, is your first visit to Ireland?

General: My first visit.

And before I could ask another question the General, turning to the window, which looked out on Stephen’s Green,- reputed to be the largest square in the word- said, “What a beautiful country.” And I must say, that in my heart I fully endorsed his words. The Green, at this season, looks peculiarly beautiful. It is encircled with a row of hawthorns, and interspersed with chestnuts, and as both at this time are putting on their coat of green, and bursting into red and white blossoms, its appearance was most striking and beautiful.

Correspondent: Ireland, General, I believe, is the land of your forefathers?

General: It is; but my family emigrated so long ago that I am unable to say whether it belonged to the north or south. It strikes me it came from Westmeath.

Correspondent: That is almost in the centre, General, and, although there is great poverty in that district, a magnificent county it is.

…Correspondent: Have you seen much of Ireland?

General: Well, yes, a good deal. I have been to Punchestown, and got a good wetting. Both days were fearfully wet. This is a damp climate, I think, and I see that it is raining to-day also. Then, I’ve been to the north of Ireland for a short time, which appears to me the most nourishing part of the country.

Correspondent: Belfast is a fine city.

General: A flourishing city; there’s wealth there, and I was greatly pleased with it. It reminded me of an American city. The people are very active, steady and industrious, and I’m sure they’ll make great progress. On the whole, I formed a very favorable impression of Ireland and the Irish people. (2)

The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, c.1900. Sheridan stayed in one of the rooms facing Stephen’s Green during his visit. Ulysses S. Grant also stayed here on his trip to Ireland (Library of Congress)

It seems almost unbelievable that Sheridan would have been unaware when he gave this interview that his parents were from Cavan rather than Westmeath. If the correspondent reported the dialogue correctly, it suggests that Sheridan at this stage of his life was either ignorant of the particulars of his family heritage, or wanted to downplay any significance that heritage had for him to an American audience. While in the Shelbourne, Sheridan was also approached by a delegation of Irish nationalists who wished to meet with him. He refused, on the basis that he felt that he was on semi-official business for the United States and such a meeting could be misconstrued. The refusal was met among the Fenian movement in America with anger and they sought a meeting with Sheridan upon his return to the United States. The General reassured them that no slight had been intended and that he was sympathetic to the Fenian cause. Although willing to voice his general support, Sheridan clearly had no intention of becoming closely identified with the nationalist movement. (3)

Phil Sheridan is a fascinating individual and his interaction with his Irish heritage is a subject worthy of attention. He steered clear of overt declarations or actions that could have been construed as associating him too strongly with the Irish-American community; this is in stark contrast to the actions of many other leading figures of Irish ancestry in the United States. His priority was to first and foremost be seen as an American. What are your thoughts on Sheridan and his ‘Irishness’? I would be keen to hear from readers- are you aware of any sources that shed further light on Sheridan or his family’s interactions with the Irish-American community?

(1) Sheridan 1888, Vol.1: 1, Sheridan 1888, Vo. 2: 452-3; (2) New York Herald 12th May 1871; (3) Ibid.; New York Irish-American 20th May 1871;

References

Sheridan, Philip, 1888. Personal Memoirs of P.H. Sheridan. General United States Army. Volume 1

Sheridan, Philip, 1888. Personal Memoirs of P.H. Sheridan. General United States Army. Volume 2

New York Herald 12th May 1871. Gen. Sheridan’s Visit to Ireland

New York Irish-American 20th May 1871. “Phil Sheridan” in Ireland

Filed under: Cavan, Discussion and Debate Tagged: Cavan American Civil War, Civil War Cavalry, Irish America, Irish American Civil War, Little Phil, New York Herald, New York Irish-American, Phil Sheridan

January 2, 2014

Bowld Soldier Boys: The Return of Irish Brigade Veterans to New York, January 1864

150 years ago, as 1864 dawned, the veteran volunteers of the Irish Brigade came home to New York. These men had come through some of the toughest battles of the war but had taken the decision to carry on the fight. Some were motivated by a desire to see the conflict out, while others were taking the opportunity of a financial bounty and thirty days leave- a chance to visit their loved ones and friends. For some it would be their last January.

Officers of the 63rd New York Infantry with their Colors. This image was likely taken in late 1863 or early 1864 (Library of Congress)

The Irish American reported on the return of the veterans. The first to arrive were the men of the 63rd New York, who came back to the city on 2nd January:

On Saturday, of last week, the remnant of the 63rd Regiment, N.Y. Vols., Irish Brigade, reached this city under command of Col. R.C. Bentley, whose officers are Captains Touhey, Boyle and Brady, Adjutant McDonald, Surgeon Reynolds, and Lieutenants Lee and Chambers. Of the returned, one hundred men are reported as having re-volunteered for the next three years or the war; and besides these, as a nucleus for re-entering on active service, a Company, of over fifty men, has been left in the field on duty with the Army of the Potomac, under command of Captain Boyle.

On Monday the remnant of the 69th reached home, numbering some 75 men, under command of the gallant little Captain Moroney and his excellent assistants, Adjutant J.J. Smith, Lieuts., O’Neill, Mulhall, Brennan, Marser, Quarter Master Sullivan and Surgeon Purcell and were welcomed by Col. Nugent and Capt. McGee.

The 88th regiment (Mrs. General Meagher’s own regiment), may, it is said, be hourly expected, under command of Captain Ryder, of Co. B.

The regiments having re-volunteered for the war were sent home to recruit and reorganize, which their officers expect speedily to accomplish. Colonel Bentley has informed us that, from the success of preliminary steps taken by him throughout the State, he hopes to be very soon again filled up; and from the general popularity of the officers of the entire command, it is hoped an equal success will reward the recruiting officers throughout. (1)

David Power Conyngham related that on their arrival in the city ‘the sparse and grimy columns were escorted by a company or two of the Sixty-ninth militia, and the immediate relatives of the members.’ On Saturday 16th January at Irving Hall, past and present officers of the Brigade held a banquet for the veteran volunteers and disabled soldiers of the regiments. The men first assembled at the City Hall around noon, before marching up Broadway behind a military band and eventually into the banqueting room. Those veterans who had lost limbs and were unable to walk waited for the others in Irving Hall. Around 200 privates were seated at five tables extending down the length of the hall, while the NCOs occupied the top table under the stage, where a band entertained the diners. The flags of the Brigade, both old and new, adorned the walls and a military trophy with the name ‘Gettysburgh’ inscribed on it was placed in the centre of the Ladies’ Gallery. Many of the women in attendance wore ‘mourning weeds’, signifying their attachment to one the Brigade’s dead. Mr. Harrison, the proprietor of Irving Hall, served the dinner which was washed down with ale, cider and whiskey-punch. (2)

Irving Hall where the Irish Brigade Veterans held their Banquet in January 1864 (New York Public Library Record ID: 1788347)

When the meal had progressed sufficiently Sergeant-Major O’Driscoll, who was presiding over the banquet, called in the officers of the Brigade led by it’s former commander, Thomas Francis Meagher. Meagher addressed the men, and his speech was followed by a series of toasts and comments from other officers. Colonel Patrick Kelly of the 88th proposed remembrance of:

‘Our Dead Comrades- Officers and soldiers of the Irish Brigade- Their memory shall remain for life as green in our souls as the emerald flag, under which, doing battle for the United States, they fought and fell.’

This was followed by the playing of a dirge, after which Colonel Nugent of the 69th came forward, promising:

‘No negotiations, no compromises, no truce, no peace, but war to the last dollar and the last man, until every rebel flag be struck between the St. Lawrence and the Gulf, and swept everywhere, the world over, from land and sea.’

More toasts followed, including special mention for the Excelsior Brigade, before Barney Williams sang ‘The Bowld Soldier Boy.’ The Fenian leader John O’Mahony then spoke to the assembled audience, and everyone stood while a dirge was played in memory of the recently deceased General Michael Corcoran. The evening concluded with toasts to the health of Father Corby, the American Press, ‘Private Myles O’Reilly’ and a humorous speech by Captain Gosson. (3)

After the banquet the men returned to their furloughs and their final few days before returning to the war. Over 100 men of the 63rd New York Infantry had re-enlisted as Veteran Volunteers in December 1863. Despite their outward commitment, at least 13 of them chose to desert at the end of their leave period rather than return to the front. For those who did go back some of the hardest fighting of the war lay ahead, as the Irish Brigade went through the meat grinder of the Overland and Petersburg Campaigns. Some would not make it- at least 12 of the men of the 63rd who occupied Irving Hall in January 1864 died, falling in battles such as the Wilderness or in prisons like Libby and Andersonville. By the close of 1864 the Irish Brigade would be unrecognisable, as the horrors of war seemed to drag on and on with no end in sight.

(1) New York Irish-American 9th January 1864; (2) Conyngham 1867:435, New York Times 15th January 1864, New York Irish-American 23rd January 1864; (3) New York Irish-American 23rd January 1864;

References

New York Irish-American 9th January 1864. Return of the Irish Brigade

New York Irish-American 15th January 1864. The Irish Brigade. Banquet to the Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates

New York Times 15th January 1864. Banquet to the Re-Enlisted Veterans and Disabled Soldiers of the Irish Brigade

Conyngham, David Power 1867. The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns

New York Public Library Digital Collection Record ID: 1788347

Filed under: 63rd New York, 69th New York, 88th New York, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 63rd New York, 69th New York, 88th New York, Civil War Bounty, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, New York Irish, Veteran Volunteers

December 28, 2013

The Long Arm of War: The Impact of the American Civil War On A Dublin City Family

We have a tendency to view the American Civil War as a conflict that impacted only the United States and only people who lived there. This was not always true. The long arm of war could be felt with violent effect across oceans and continents. Some of those who had their lives changed utterly by the struggle between blue and gray had never even set foot on American soil. Such was the case with Maria Ridgway, who spent the vast majority of her life living in the city of Dublin- thousands of miles from the seat of the ‘War of 1861.’

Maria McDonald was born in Athlone around the year 1840, the daughter of Edward McDonald, a soldier in the British Army. When she was still a child her family moved to Dublin where they were stationed at Beggar’s Bush Barracks in the city. It was here that a young Maria first met Corporal George Ridgway of the 30th Regiment of Foot. Born in Shropshire, England, George was a career soldier. The couple hit it off and were married in St. Peter’s Church of Ireland parish church, Aungier Street, Dublin on 30th February 1859. (1)

St. Peter’s Church, Aungier Street, Dublin. George and Maria were married here in 1859 (Wikipedia)

The couple did not have to wait long for their first child. Maria Honora was born on the 22nd November 1859; a son Joseph George followed on the 3rd March 1862. Both children were baptised as Roman Catholics in St. James’ Parish Church, Dublin. By the time of their son’s birth George’s term of enlistment in the British Army was up. Rather than re-enlist, he decided to seek new opportunities. The war then raging across the Atlantic seemed to offer promising prospects for someone of George’s expertise and presented a potential way for the family to improve their fortunes. Baby Joseph was not yet 6 months old when George left Dublin for New York.Travelling via Liverpool, his ship, the ‘Edinburgh’, landed in the United States on 17th September 1862. (2)

Men of the 1st US Cavalry in 1864 (Library of Congress)

George did not enlist straight away; perhaps he was looking explore his options before fixing on a return to a military life. He eventually decided on a career in the 1st United States Cavalry, enlisting on 24th February 1863. Mustering in as a Private in Company L, he headed to Virginia, embarking on a path that he no doubt hoped would bring economic security for him and his young family. That June, Maria received a letter through the U.S. Consul in Dublin:

Sanitary Commission

Washington D.C. U.S.A.

June 25th 1863

Mrs. Maria Ridgway

Dublin, Ireland

Madam,

It has become my mournful duty to inform you of the decease [sic.] of your husband George Ridgway U.S. Cavalry 1st Regt. Co. L. He was brought to this hospital from hospital at Aquia Creek very sick of chronic diarrhea on the 15th instant and died on the 19th inst. Was extremely feeble able to say but little. His last words were of you and his children. Tell my wife I die believing in the Lord Jesus. I hope the Lord will be a husband to her. Give my love to my wife and children. He had good care. Died in one of our best hospitals. Religious services were performed by the Chaplain in a grave in the hospital ground. At his burial an escort followed the body which was buried in the National Cemetery provided for soldiers and his graves [sic.] is carefully preserved having an inscribed and numbered head-board so that it can be identified at any future day. May God in his love and mercy minister to you and your children large consolations in Christ Jesus giving you beauty as ashes, the oil of joy for mourning and the garment of praise for the spirit of heaveness. Please accept my very sincere condolence in Christ.

Joseph M. Driver

Chaplain Columbian Hospital

Washington D.C. U.S.A. (3)

The Columbian Hospital where George Ridgway died in 1863 (Library of Congress)

George’s American military career had lasted less than four months. He was buried at what is now the US Soldier’s and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery where his grave can still be seen. Maria was still only in her early twenties. Now a widow, she applied and received a U.S. military pension. It started in 1865 at $8 a month, a sum she collected from her home in Goldenbridge, Dublin. This was later increased to take account of her daughter and son, with the additional monies to be paid until they reached the age of 16. The young woman and her children had never been to the United States, and most likely had never journeyed outside Ireland. Despite this, their entire lives had been turned upside down by the American Civil War. The conflict and her husband’s part in it would continue to be a central element of Maria’s life for decades to come. (4)

Copy of Letter to Maria Ridgway informing her of her husband’s death, 1863 (Fold3)

As the years passed and Maria grew older she continued to receive a U.S. pension and rely on the income it provided. Then, in 1893, a change to the pension system meant that her income stream suddenly came under threat. She was now required to show that her husband had been a naturalised citizen of the United States at the time of his death, something that was virtually impossible for Maria to demonstrate. If she failed to do so her pension might be terminated. Maria decided to embark on a letter writing campaign, first addressing the U.S. Pension Agent:

To the U.S. Pension Agent

Most Honourable Sir,

This humble petition of Maria Ridgway, widow of George Ridgway Pvt. U.S. Cavalry who is interred in the Soldiers burying ground in Washington D.C. with an inscribed and numbered headboard, the Reverend Joshua M. Driver Chaplain to the U.S. Soldiers kindly sent me and my children my husbands dying words and where I could see his grave at any future time. Not having received my pension voucher No. 57226 to sign for the next quarter 4th September I have taken the liberty in addressing you and I knowing how good the Government has been to me all these years, in giving me means to live since the death of my husband who died fighting for them. I am sure so good a Government would not leave the widows of their soldiers dying in a Workhouse. I am now old and unable to earn my bread, with bad eyes and in a very delicate state of health, hoping the U.S. Government would kindly take my case into their kind consideration and grant me for the short time I expect to be in the world what would keep me from the Workhouse. By so doing I shall always think myself as duty bound to pray for my kind benefactors. Sir I have the honour to remain your most humble and obedient servant,

Maria Ridgway

163 Gt. Britain Street [now Parnell St.]

or U.S. Consul

Great Brunswick St.

Dublin. (5)

Just in case this letter did not work, Maria also took the precaution of writing directly to the President of the United States, Grover Cleveland:

To the President of the United States

Most Honourable Sir,

The humble petition of Maria Ridgway widow of George Ridgway who was a private in the 1 U.S. Cavalry and fought under the American Stars and Stripes for the American cause he is buried in the Soldiers burying ground Washington D.C. I his widow and two children was granted a pension on Certificate 57226, Act July 14- 1862 and in March 19-1886 through the goodness of the American Government at which time I think you were President [Cleveland had been serving his first term as President in 1886] I got my increase to 12 dollars per month. Now through an Act of Congress July 1-1893, I am deprived of any means of support in my old age when I am feeble and not able to do anything for myself through rheumatism. Most Honourable Sir through your goodness of heart, should you take my declining years into your kind consideration and grant me a little to keep an American Widow from dying in a Workhouse, and my two orphans shall always think it our duty to pray for you. I have the honour to be Sir your most faithful servant,

Maria Ridgway

c/o Mrs. Alford [her daughter's married name]

6 Florinda Place, North Circular Road,

Dublin

5th March 1894. (6)

Copy of letter from Maria Ridgway to the President of the United States (Fold3)

In other correspondence relating to the suspension of her pension, Maria argued that she did not know if her husband George had been a naturalized citizen of the United States. She explained that in 1863 ‘he wrote to me and said if he got safe through the war America was to be our home, but God had it otherwise.’ Maria then claimed that prior to her husband emigrating in 1862 he had already spent 11 years in the United States, at which time he may well have become a citizen. She enlisted the help of her local priest, Father Bernard Emmett O’Mahony, who wrote to the American authorities on her behalf, asking: ‘Is there any hope that this harsh if not unjust statute will be repealed?’ Maria’s determined efforts eventually paid off, and her pension was reinstated on 4th March 1895. (7)

Despite Maria’s concerns that she may not have had long left to live in the 1890s, she survived well into the 20th century. In 1911 she was still living at 163 Great Britain Street with her son Joseph, who had become a hairdresser, his wife Elizabeth and their eight children. Her daughter Maria had married Cattle Dealer John Alford and they and their nine children were living on Henrietta Street- Maria was now grandmother to a total of 17. (8)

Maria Ridgway’s health finally began to fail in December 1918, with things taking a turn for the worse the following March. She passed away on the afternoon of 8th July 1919 at the home of her daughter, in No.2 Synnott Place, Dublin. The official cause of death was cancer of the liver. Her entire effects, which consisted of ‘a few pieces of old furniture and old clothes’ were left to her daughter. The American Civil War widow’s funeral mass was held at St. Joseph’s Church on Berkeley Road before her remains were laid to rest in St. Bridget’s Section of Prospect Cemetery, Glasnevin, Co. Dublin. In April 1920, almost 57 years after Private George Ridgway’s death in Washington D.C., the U.S. Government made its final pension payment to the Dublin family, when it contributed towards the expenses of Maria’s funeral. (9)

Farrell’s undertakers receipt relating to the funeral of Maria Ridgway (Fold3)

(1) George Ridgway Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; New York Passenger Lists; (3) George Ridgway Widow Pension File; (4) Ibid., Find A Grave Memorial; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; (8) 1911 Census of Ireland; (9) George Ridgway Widow’s Pension File.

References

George Ridgway Widow’s Pension File WC57226

George Ridgway Find A Grave Memorial

New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

Filed under: Dublin, Irish in the American Civil War, Pensioners in Ireland, Research Tagged: 1st U.S. Cavalry, Aquia Creek, Beggars Bush Barracks, Columbian Hospital, Glasnevin Cemetery, Irish American Civil War, Pensioners on the Roll, United States Army

December 22, 2013

‘Our Orphan Children Will Not Soon Forget Him’: The Death of General Michael Corcoran

150 years ago, on the evening of Tuesday 22nd December, 1863, a stunned Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Reed prepared to send a message that promised to send shockwaves through New York City. The commander of the 69th New York National Guard Artillery dictated the following telegram to be immediately communicated to the press:

FAIRFAX COURT-HOUSE , Tuesday, Dec. 22.

To the Associated Press:

Gen. Michael Corcoran died at half-past eight this evening, from injuries received from a fall from his horse.

Thos. M. Reed,

Lieut.-Col. Com’g. 69th Reg., Corcoran Irish Legion. (1)

Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran (Library of Congress)

Michael Corcoran was perhaps the most highly regarded Irishman in New York. A dedicated Fenian, he had been Colonel of the 69th New York State Militia and had achieved notoriety when he refused to parade his men on the occasion of the Prince of Wales’ visit to the city in 1860. His imprisonment following his capture at Bull Run, when he was held under threat of retaliatory execution by the Confederacy, led to him becoming a national hero. His eventual release and triumphant return to New York in 1862 solidified his status, and as a newly minted Brigadier-General he raised a new Union brigade, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, which had a strong Fenian membership. Now, at the age of just 36, the darling of New York’s Irish community was dead. The news was received with the ‘utmost incredulity’ by all who knew him. How did it happen? The Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo native had not died at the head of his troops fighting the Rebels, or given his life heroically in the cause of Ireland. Instead, his death was caused by an accidental fall from a horse. (2)

One of the most detailed accounts of the incident was carried in the New York Irish-American, who blamed the General’s death on an attack of apoplexy. It reported that on the morning of the December 22nd Corcoran had been feeling somewhat unwell, but decided to proceed with the days duties nonetheless. Thomas Francis Meagher, the former commander of the Irish Brigade, had been visiting the Irish Legion for a few days and Corcoran decided to accompany him to Fairfax Station, where Meagher was taking a train to Washington. Meagher was travelling to the capital to meet a group of ladies, including his wife and Corcoran’s mother-in-law, and bring them back with him to spend Christmas with the Legion at Fairfax Court-House. Corcoran set off for the train with Meagher and a small group of officers; he bid his wife farewell, telling her that he would be back for dinner in the afternoon. (3)

Officers of the 69th New York State Militia pose beside one of the guns in Fort Corcoran prior to the Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Michael Corcoran is at extreme left (Library of Congress)

With Meagher seen safely to the train, Corcoran and his party rode on to Sangster’s Station to call on the Legion’s 155th New York Infantry. Here the General left orders regarding the regiment’s dispositions and defences, before turning for home. At this point one of his party, Lieutenant Edmond Connolly, noted that the General’s horse had thrown a shoe. Meagher had left his horse with them, and so Corcoran decided to ride his friend’s mount for the rest of the journey. After travelling only a few yards Corcoran turned to Connolly to tell him how magnificent the horse was, adding: ‘I understand that he is a fast horse when put to it, for he won a race on St. Patrick’s Day at Falmouth; and so let us have a bit of a race and test him.’ Meagher’s grey, Jack Hinton, had won a race during the famous St. Patrick’s Day 1863 celebrations while being ridden by Captain Gosson of the Irish Brigade- it is likely it was this horse that Corcoran was riding that day. His decision to test out the animal’s capabilities would prove a fateful one. (4)

Corcoran and his party broke into a gallop, with the General taking the lead. He appeared to lose control of the animal, an occurrence perhaps influenced by the old-fashioned English saddle that Meagher had on the horse, which provided less support than Corcoran was accustomed to. The horse charged forward, and the General waved at his companions to fall back, presumably in the hope of calming his mount. Disappearing into a dip in the road the party briefly lost sight of their commander. At about this time Corcoran’s horse apparently lunged to the left and the General was spilled to the ground. By the time his men came up the Sligo native was apparently experiencing violent convulsions. The time was a little after four o’clock; the commander of the Irish Legion was carried back to his quarters at the W.P. Gunnell House in Fairfax where he died some four hours later, having never regained consciousness. (5)

The W.P. Gunnell House, Fairfax, Virginia, where Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran died (Photograph Dave Sullivan)

Thomas Francis Meagher returned to find his friend dead. He later described the scene:

‘There, in that very room which I had occupied for several days as his guest…he lay cold and white in death, with the hands which were once so warm in their grasp, and so lavish in their gifts crossed upon his breast, with a crucifix surrounded by lights standing at his head, and the good, dear old priest [Father Paul Gillen], who loved him only as a father can love a son, kneeling, praying, and weeping at the feet of the dead soldier.’ (6)

The men of Corcoran’s Legion, who idolized their General, were given a final opportunity to see him. Meagher continues:

‘One by one, as the sun went down, and the last rays, reflected from those mountains that had been the witness of his first trial under fire, fell upon that pale and tranquil face, the soldiers of the Irish Legion moved in mournful procession around the death-bed, and, as they took their last look at him, I saw many a big heart heave and swell until tears gushed from many an eye and ran down the rough cheek of the roughest veteran.’ (7)

General Setting of the New Marker to Michael Corcoran in Fairfax, Virginia (Photograph Dave Sullivan)

Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran’s remains were taken to New York where they lay in state at the City Hall prior to his burial at Calvary Cemetery. To read more about the funeral service see a previous post here. His loss was keenly felt by the Irish across America, even by some with Confederate sympathies. One Irish Clergyman in Virginia wrote the following letter about his death:

‘…Permit me to sympathize with you in the death of our mutual friend and distinguished countryman, General Michael Corcoran. Though I differed with him on the great subject that now convulses this once happy land, though I could not endorse his acts as a General of the United States Army, still I loved him as an Irishman and a Catholic. I respected him for his devotion to the dear old land of our nativity; and in death I have not forgotten him for obedience to his Mother, the Holy Catholic Church.

I announced his death to my people on Sunday last; I spoke of him as a Christian soldier, and begged them to join their prayers with mine, while I offered the holy Mass for the repose of his soul. I can never forget the visits he paid me during his stay near this city. I needed not his star; I thought not of his rank in the army; but as the Irishman and the Catholic he was always at home with the Priest, and as such always got the “cead failtha” from me.

Our orphan children will not soon forget him: they will pray for him when, perhaps, he is not remembered by the busy world without. Their humble prayer will ascend to the throne of God for mercy on the soul of the generous soldier, who, amid the din and strife of the war, did not forget them in their hour of need…’ (8)

The Marker to Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran in Fairfax, Virginia (Photograph Dave Sullivan)

Michael Corcoran is today remembered by the largest American Civil War memorial in Ireland, in Ballymote, Co. Sligo. On the 19th October 2013 the City of Fairfax unveiled a historical marker dedicated to Corcoran at the site where he died. Michael Corcoran and his Irish Legion have spent much of history in the shadow of Thomas Francis Meagher and the Irish Brigade. Somewhat surprisingly he has never been the subject of a detailed biography, and his Legion have never been the focus of a published brigade history. Important work by historians such as Christopher M. Garcia is helping to redress this imbalance and hopefully will lead to further insights into this important man and his brigade in the future. (9)

* This post would not have been possible without the efforts of Dave Sullivan. Dave originally alerted me to the unveiling of the Corcoran Marker, took the time to visit the site and photograph both it and the Gunnell House for the post and also provided invaluable source material, particularly the Alexandria Gazette account of the accident.

The Memorial to Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran in Ballymote, Co. Sligo. This is the closest village to Carrowkeel where Corcoran was born on 21st September 1827

(1) New York Times 23rd December 1863; (2) New York Irish American 2nd January 1864; (3) Ibid.; (4) New York Irish American 2nd January 1864, Conyngham 1867: 373-379; (5) New York Irish American 2nd January 1864, Alexandria Gazette 1st January 1864; (6) Cavanagh (ed.) 1892: 357; (7) Ibid.; (8) New York Irish American 9th January 1864; (9) Fairfax City Patch 18th October 2013;

References & Further Reading

Alexandria Gazette 1st January 1864. Death of Gen. Corcoran

Fairfax City Patch 18th October 2013. New Historical Marker in Honor of Soldier To Be Unveiled in Oldtown Saturday

New York Times 23rd December 1863. Death of Gen. Corcoran.; He is Killed by a Fall From His Horse

New York Irish-American 2nd January 1864. Death of Brigadier General Michael Corcoran. Arrival of His Remains in New York

New York Irish-American 9th January 1864. General Corcoran. A Noble Tribute

Cavanagh, Michael (ed.) 1892. Memoirs of Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher

Conyngham, David Power 1867. The Irish Brigade and its Campaigns

Michael Corcoran Find A Grave Memorial

Filed under: Corcoran's Irish Legion, Michael Corcoran, New York, Sligo Tagged: Corcoran's Irish Legion, Fairfax Court House, Fenian Brotherhood, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Michael Corcoran, New York Irish-American, Thomas Francis Meagher

December 19, 2013

U.S. Military Pensioners in 19th Century Ireland: A Listing and Appeal

I have been spending an increasing amount of time looking at the records of U.S. military pensioners who lived in Ireland. Of the c. 170,000 Irish who fought in the American Civil War, only a relative handful ever returned to the country of their birth. The 1883 List of Pensioners on the Roll records a total of 220 people who were receiving money in Ireland as a result of services rendered to the United States military. Some were veterans, but the majority were widows, dependent mothers and dependent fathers. There is something remarkable about the image of men who had lost limbs in great battles such as Chancellorsville returning to live out their lives in rural Ireland, travelling to their local Post Office each month to collect their pension, or elderly parents depending on their children’s sacrifice across the Atlantic for support.

Civil War Pensioner O.D. Kinsman in 1920, who Worked in the Pension Bureau (Library of Congress)

Not all of the pensions on the 1883 Roll relate to the Civil War- some of them were given for service before or after that conflict. I have spent a considerable amount of time attempting to identify the name of the associated veteran (where the recipient of the pension was not the soldier or sailor) and the unit in which they served. The table below is based on this work, which derives the names of the pensioners and the reason for the pension from the 1883 Roll. Of course this list does not represent all of the pensions being received in 19th century Ireland for service to the United States. Confederate veterans are not included, and many Union veterans and veterans of conflicts such as the Plains Wars had either not returned to Ireland by 1883 or were not claiming pensions at that point.

I have already delved into the extraordinary personal stories of many of those listed below and I have many more to explore. It is my intention to attempt to develop these stories into book format. However, I am keen to include others, not on this list, who may have been receiving a U.S. military pension for 19th century service or were U.S. military veterans who had returned to Ireland. As a result I want to appeal to readers- if you are aware of anyone who you think might fit this bill I would be very eager to hear from you, and about the pensioner/veteran in question. In the meantime I will be placing the below list on the Resources section of the site in the coming days where it will be available for future reference.

Pensioner Name

Veteran Name

Unit

Reason for Pension

Allen, Catherine

Allen, Michael

10th Tennessee Infantry

Widow

Bane, Bridget

Bane, Patrick

10th Kentucky Infantry

Widow

Baxter, Christiana

Baxter, Robert

11th New York Infantry

Widow

Beatty, Thomas

Beatty, Thomas

4th New York Heavy Artillery

Loss of Left Leg

Beaty, Michael

Beaty, Michael

149th New York Infantry

Loss of Right Leg

Bennet, Alice

Bennett, John

4th New York Heavy Artillery

Widow

Boyle, Hugh

Boyle, Hugh

16th United States Infantry

Disability to Lungs

Brady, Peter

Brady, Peter

3rd United States Artillery

Paralysis to Right Side

Bransfield, John J.

Bransfield, John J.

U.S.S. Brooklyn

Navy

Brien, Eliza

Brien, John J.

69th New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Brooks, Richard

Brooks, Richard

72nd New York Infantry

Loss of Right Thumb

Brown, Mary A.

Brown, John J.

73rd New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Brush, Susan

Brush, Crane

Hospital Steward U.S.A.

Widow

Buckley, Timothy

Buckley, Timothy

?

Wound Left Ankle and Hand

Buird, Michael

Baird, Michael

161st New York Infantry

Total Loss of Sight

Burns, Bridget

Burns, John

116th Pennsylvania Infantry

Dependent Mother

Burns, Mary

Burns, Owen C.

13th Pennsylvania Cavalry

Widow

Butler, Mary (Walshe)

Butler, James

12th New York Cavalry

Widow

Byrne, Andrew J.

Byrne, Andrew J.

42nd New York Infantry

Wound to Left Arm

Byrne, Martin

Byrne, Martin

4th United States Infantry

Wound to Chin

Cain, James

Cain, James

10th Veteran Reserve Corps

Wound to Left Shoulder

Cannavan, Mary

Canavan, Thomas

5th United States Cavalry

Dependent Mother

Cannon, Ann

Cannon, James

U.S.S. Oneida

Widow

Carey, Mary

Carey, Stephen

2nd Delaware Infantry

Widow

Carins, Ann

Cairns, Colin

2nd New Hampshire Infantry

Widow

Carlin, Anna

?

?

Widow

Chestnut, Richard

Chestnut, Richard

3rd Wisconsin Cavalry

Paralysis to Right Side

Church, George

Church, George

17th New York Infantry

Loss of Left Arm

Clancy, Bernard

Clancy, Bernard

1st United States Artillery

Disability Lungs and Heart

Clark, Margaret

Clark, Edward

30th Massachusetts Infantry

Dependent Mother

Cleary, Honora (Browne)

Cleary, Francis M.

10th United States Infantry

Widow

Cochburn, William

Cockburn, William

2nd New Jersey Cavalry

Loss of Left Leg

Cochran, Sarah J.

Cochran, Richard

63rd Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Collins, Peter

Collins, Peter

U.S.S. Worcester

Disability to Lungs

Connelly, Margaret

Conneely, John

10th Tennessee Infantry

Widow

Conner, Ellen

?

?

Dependent Mother

Connolly, Patrick

Connolly, Patrick

70th New York Infantry

Loss of Left Foot

Connor, Bridget

Connor, Patrick

2nd New York Heavy Artillery

Widow

Connor, Patrick

Connor, Patrick

21st United States Infantry

Wound to Left Arm, Disability Brain

Connor, William

Connor, William

6th New York Heavy Artillery

Loss of Left Arm

Corrigan, Philip

Corrigan, Philip

16th United States Infantry

Wound to Left Leg

Costello, Eliza

Costello, James

69th Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Costello, Mary

Costello, Kyran

6th United States Cavalry

Dependent Mother

Courtney, Mary

Courtney, John C.

7th Missouri Infanftry

Dependent Mother

Coyne, Ellen

Coyne, Michael

7th United States Infantry

Widow

Coyne, John

Coyne, John

104th Illinois Infantry

Wound to Right Knee and Disability Lungs

Cranston, Ellen

Cranston, William C.

63rd New York Infantry

Widow

Crawford, James

Crawford, James

U.S.S. Saugus and U.S.S. Powhatan

Navy

Crowe, Sarah (McDonagh)

Crow, John

155th New York Infantry

Widow

Crowley, Catherine

Crowley, Jeremiah

88th New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Crowley, Patrick

Crowley, Dennis

23rd United States Infantry

Dependent Father

Cruise, Mary

?

?

Dependent Mother

Cuniff, James

Cuniff, James

35th New Jersey Infantry

Loss of Left Leg

Cunningham, Phaley

Cunningham, Phaley

83rd Ohio Infantry

Loss of Left Arm

Curran, Margaret

Curran, Thomas

5th Indiana Cavalry

Widow

Daily, William

Daily, William

18th United States Infantry

Paralysis

Daly, Mary

Daly, John (Alias John Ryan)

51st New York Infantry

Widow

Delany, Annie

Delany, Patrick

61st Ohio Infantry

Widow

Devine, Owen

Devine, Owen

37th New York Infantry

Varicose Veins Left Leg

Donnelly, John A.

Donnelly, John A.

3rd New York Cavalry

Disability

Donohoe, Bridget

Donohoe, John

1st United States Artillery

Dependent Mother

Dooley, Mathew

Dooley, Mathew

2nd New York Heavy Artillery

Wound to Right Leg

Doran, Ellen

?

?

Widow

Dorn, Mary T.

Dorin, Lawrence J.

U.S.S. Powhatan

Widow

Dowd, Joseph

Dowd, Joseph

?

Wound to Left Leg

Dowdy, James

Dowd, James (Alias James Dowdy)

6th United States Infantry

Wound to Left Hand

Dowling, Catherine

Dowling, Dennis

15th Connecticut Infantry

Widow

Dowling, Simon

Dowling, Simon

164th New York Infantry

Injury to Abdomen

Dreak, Ellen

Dreak, David

3rd United States Infantry

Dependent Mother

Druitt, Edward alias John Moran

Druitt, Edward (Alias John Moran)

12th New Jersey Infantry

Wound Left Hand and Lower Jaw

Duffy, Thomas

Duffy, Thomas (Alias Thomas Ryan)

2nd New Jersey Cavalry

Loss of Right Arm

Durick, Timothy

Durick, Jeremiah

88th New York Infantry

Dependent Father

Edgeworth, Annie

Edgeworth, Robert L.

7th United States Infantry

Dependent Mother

Farrell, Anne

Farrell, John

173rd New York Infantry

Widow

Flynn, James

Flynn, James

30th United States Infantry

Asthma

Flynn, Mary

Flynn, Patrick

11th? Kansas Cavalry

Widow

Forrester, Patrick

Forrester, Patrick

99th Pennsylvaniva Infantry

Loss of Left Leg

Fox, Eliza

Fox, John

7th Massachusetts Infantry

Widow

Fry, Sarah

Fry, Robert

8th Indiana Infantry

Widow

Gallagher, Mary

Gallagher, Peter

5th United States Infantry

Widow

Galvin, Catherine

Galvin, Willian

11th United States Infantry

Dependent Mother

Gartland, Ann

Gartland, Patrick

5th Pennsylvania Cavalry

Dependent Mother

Gavin, Catherine

Gavin, Cornelius

52nd New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Gilroy, Patrick

Gilroy, Patrick

77th New York Infantry

Dependent Father

Gosselin, Alice M.

Gosselin, Francis J.

7th United States Cavalry

Widow

Graney, Eliza

Graney, Charles

9th Massachusetts Infantry

Dependent Mother

Grogan, Henry

Grogan, Henry

5th New York Heavy Artillery

Wound to Left Shoulder

Groogan, Mary

Groogan, Bernard

90th Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Guiltinane, Catherine

Guiltinane, Michael

16th New York Heavy Artillery

Widow

Hanlon, Francis

?

?

Dependent Father

Harrington, Mary

Harrington, Owen

30th Indiana Infantry

Dependent Mother

Harvey, James

Harvey, James

59th New York Infantry

Wound to Head

Hasler, Nellie

Hasler, Jacob

53rd Kentucky Infantry

Widow

Hayde, William

Hayde, William

Heavy Artillery

Paralyisis of Left Hand

Hazlett, Mary J.

?

?

Widow

Henry, Catherine

Henry, Mathew

72nd New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Herks, James

Herks, James

24th Massachusetts Infantry

Wound to Left Arm

Hickey, Michael

Hickey, Michael

14th United States Infantry

Disability Lungs and Heart

Hoare, David

?

1st United States Infantry

Disability to Lungs and c.

Horan, Mary

Horan, Dennis

8th United States Cavalry

Dependent Mother

Houston, Archie

Houston, Archie

66th Ohio Infantry

Diarhorrea and c.

Humphrey, David H.

Humphrey, David H.

2nd New York Heavy Artillery

Wound Left Hand

Hunter, Frederick

Hunter, Frederick

66th New York Infantry

Rheumatism

Hurd, Kate

Hurd, Charles H.

U.S.S. Itasca

Widow

Johnston, Sarah (Acres?)

Johnston, Charles

139th New York Infantry

Widow

Jones, Margaret

?

?

Widow

Jordan, Mary A.

Jordan, Charles H.

69th New York Infantry

Widow

Kean, John

Kean, Simon

15th New Jersey Infantry

Dependent Father

Keane, Edward

Keane, Edward

1st United States Engineers

Disability to Lungs and c.

Keefe, Peter

Keefe, Peter

U.S. Brig Perry

Exempt Navy

Keily [Kelly], Jane (McAllister)

Kelley, Daniel

141st New York Infantry

Widow

Keily, William

Keily, William

22nd United States Infantry

Fractured Right Leg

Kelly, Margaret

?

?

Dependent Mother

Kelly, Mary A.

Kelly, John

U.S.S. Santiago de Cuba

Widow

Kelly, Thomas

Kelly, Thomas

69th New York Infantry

Loss of Left Arm

Kennedy, Mary

Kennedy, Michael

32nd New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Kennedy, Mary

Kennedy, John

146th New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Kennelly, Mary

Kennelly, Maurice

24th United States Infantry

Dependent Mother

Kenny, Sarah

Kenny, Felix

4th United States Cavalry

Widow

King, Richard

King, Richard

7th Maine Infantry

Wound to Left Leg

Kinney, Bridget

Kenney, Michael

42nd New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Kinney, Michael

Kinney, Michael

?

Loss of Right Leg

Larkin, Catherine

?

?

Widow

Lawler, Michael

Lawler, Michael

22nd Massachusetts Infantry

Injury to Abdomen

Leonard, Patrick

Leonard, Patrick

75th New York Infantry

Injury to Left Side and Injury to Abdomen

Loughland, William

Laughlan, William

74th New York Infantry

Wound to Right Shoulder

Mack, Maurice

Mack, Maurice

?

Wound to Left Leg and ulcers

Maloney, Ellen

Maloney, James

15th Wisconsin Infantry

Widow

Martin, Eliza

Martin, Samuel

113th New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

Martin, Ellen (Baker)

Martin, Patrick

182nd New York Infantry

Widow

McAuley, Patrick

McAuley, Patrick

3rd United States Artillery

Disability of Abdominal Viscera

McCabe, Catherine

McCabe, Michael

170th New York Infantry

Widow

McCann, Patrick

McCann, Patrick

145th Pennsylvania Infantry

Loss of Left Arm

McCarthy, Catherine

McCarthy, Thomas

U.S.S. Housatonic

Widow

McCarthy, Daniel

McCarthy, Daniel

?

Rheumatism

McCausland, Mary

McCausland, William

U.S.S. Yantic

Widow

McCloskey, Frances

?

?

Dependent Mother

McConneghy, Alice

McConneghy, William J.

U.S.S. Albatross

Dependent Mother

McDermott, Edward

McDermott, Edward

8th United States Cavalry

Injury to Right Side

McDermott, Margaret

McDermott, George

7th United States Cavalry

Dependent Mother

McDermott, Patrick

McDermott, Patrick

U.S.S. Omaha

Navy

McDonnell, Maria

?

5th New York Artillery

Widow

McElroy, Henry

McElroy, Henry

34th Massachsetts Infantry

Wound left Leg

McGarity, Bridget

McGarity, Francis

88th New York Infantry

Widow

McGlynn, John

McGlynn, John

11th Massachusetts Infantry

Loss of Right Arm

McGrath, Catherine

McGrath, John (Alias John Brown)

179th New York Infantry

Dependent Mother

McGrath, Henry

McGrath, Henry

96th Pennsylvania Infantry

Rheumatism

McGready, Edward

McGready, Edward

?

Loss of Finger in Left Hand

McGrory, Bridget

McGrory, John Jr.

82nd Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

McHugh, Annie

McHugh, Joseph

69th Pennylvania Infantry

Dependent Mother

McKenna, Mary A.

?

?

Widow

McKinney, John

McKenny, John

5th Connecticut Infantry

Loss of Right Arm

McLaughlin, John

McLaughlin, John

88th Illinois Infantry

Injury to Abdomen

McMahon, Peter

McMahon, Peter

2nd United States Cavalry

Wound to Left Leg

McNale, Mary (McHale)

McHale, Matthew

6th Missouri Infantry

Dependent Mother

McNamara, Bridget

McNamara, Patrick

1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery

Widow

McNaull, Mathew

McNaul, Mathew

U.S.S. Suwanee

Exempt Navy

Mitchell, Catherine A.

Mitchell, Benjamin

1st New York Cavalry

Widow

Moon, Ann

Moon, William

20th Wisconsin Infantry

Widow

Mooney, Esther

?

?

Widow

Mooney, John

Mooney, John

U.S.S. Saugus

Navy

Morris, Patrick

Morris, Patrick

7th Michigan Infantry

Wound to Head

Mulberry, John

Mulberry, John

145th Pennsylvania Infantry

Loss of Right Arm

Murphy, Patrick

Murphy, Patrick

36th New York Infantry

Wound to Left Wrist

Murray, Barbah

Murray, John D.

99th New York Infantry

Widow

Neary, Mary

Neary, Nicholas (Alias Edward Neary)

9th New Jersey Infantry

Widow

Nolan, Ann

Nolan, Peter

Artillery Detail

Dependent Mother

Noonan, John

Noonan, John

88th New York Infantry

Wound to Right Shoulder

O’Brien, Honora

O’Brien, Patrick

U.S.S. Clifton and Mississippi

Dependent Mother

O’Brien, Hugh

O’Brien, Hugh

170th New York Infantry

Loss of Left Leg

O’Brien, William

O’Brien, William

?

Disability to Eyes

O’Connor, Ann

O’Connor, Michael

5th New York Infantry

Widow

O’Leary, John

O’Leary, John

8th United States Infantry

Loss of Left Leg

O’Maley, Bridget

O’Maley, John

53rd Illinois Infantry

Dependent Mother

O’Mara, Alice

O’Mara, Peter (Alias Peter Morrow)

2nd Wisconsin Infantry

Dependent Mother

O’Neill, Dennis

O’Neill, Dennis

10th United States Infantry

Injury to Right Eye

O’Shaughnesey, Edward

O’Shuaghnessey, Edward

69th New York Infantry

Wound to Right Arm

Owens, Mary

?

?

Widow

Path, Alvin

Path, Alvin

?

Rheumatism

Pelein, Eliza

Pelein, Alexander

25th Iowa Infantry

Widow

Pight, John

Pigot, John

42nd New York Infantry

Wound to Right Thigh

Quigley, Bridget

Quigley, Patrick

51st New York Infantry

Widow

Reardon, Catherine (McGuigan)

Reardon, Thomas

107th New York Infantry

Widow

Riddle, James

Riddle, James

8th United States Infantry

Disability of Abdominal Viscera

Ridgway, Maria (McDonald)

Ridgway, George

1st United States Cavalry

Widow

Rignay, Bryan

Rignay, Brian

13th United States Infantry

Disability

Riley, James

Riley, James

4th United States Cavalry

Injury to Head

Russell, Fannie

Russell, Patrick

3rd New Jersey Infantry

Dependent Mother

Ruth, Moses

Ruth, Moses

?

Strain in Back

Ryan, Mary

Ryan, Patrick

5th Rhode Island Infantry

Widow

Ryan, Mary

?

?

Dependent Mother

Seaver, Michael

?

?

Dependent Father

Sheehan, Jane (McClintock)

Sheehan, Michael

150th Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Sowery, Ellen M.

Sowery, Louis

42nd New York Infantry

Widow

Stafford, Jasper

Stafford, Jasper

170th New York Infantry

Loss of Right Arm

Stewart, Mary (Johnston)

Stewart, James

19th Wisconsin Infanftry

Widow

Strawbridge, Margaret

Strawbridge, John

69th New York Infantry

Widow

Sulivan, Cornelius

Sullivan, Cornelius

69th New York Infantry

Wound to Left Leg and Paralysis

Sullivan, Bridget

?

?

Widow

Sullivan, Jeremiah

Sullivan, Jeremiah

69th New York Infantry

Wound to Left Foot

Sullivan, Mary

Sullivan, Michael

69th New York Infantry

Widow

Sullivan, Thomas

Sullivan, Thomas

?

Wound to Left Foot

Tierney, Edward

Tierney, John

U.S.S. Huron

Dependent Father

Tinan, John

Finan, Patrick

U.S.S. Wabash

Dependent Father

Toomey, Mary

Toomey, Robert

176th New York Infantry

Widow

Torrens, Isabella

Torrens, Joseph

78th New York Infantry

Widow

Voss, William

Voss, William

?

Disability Heart

Walls, Bridget (Crilly)

Walls, John

116th Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Walsh, Ellen

Walsh, Patrick

22nd Illinois Infantry

Widow

Ward, Ellen

?

?

Widow

Waters, William

Walters, William

52nd Illinois Infantry

Wound to Head

Webb, Abby

Webb, Thomas Jr.

59th Massachusetts Infanftry

Dependent Mother

Welsh, John

Welsh, John

5th United States Cavalry

Loss of part of Finger

Whelan, Maria

Wheelan, Patrick

1st New York Infantry

Widow

Whelan, Mary

Whelan, Dennis

82nd Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

White, Ann

White, John

7th Wisconsin Infantry

Dependent Mother

White, Mary

White, Edward

4th U.nited States Cavalry

Widow

Wilson, Archibald

Wilsdn, Archibald

25th New York Cavalry

Varicose Veins Left Leg

Wilson, Louis

Wilson, Louis

17th New York Infantry

Loss of Right Thigh

Wilson, Margaret

Wilson, Edward

29th Pennsylvania Infantry

Widow

Table 1. Complete table of Pensioners in Ireland from ‘List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883′ with names of veterans and units added where known.

References

Government Printing Office 1883. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883. Volume 5

Filed under: General, Irish in the American Civil War, Research Tagged: 1883 Pensioners on the Roll, American Civil War and Ireland, Ireland American Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Irish Military Pensions, Irish Veterans, Pensioners on the Roll, United States Veterans

December 13, 2013

Dependent Father: How one Irish Brigade Soldier’s Service Helped an Elderly Man in Rural Tipperary

Each month for much of the 1880s the octogenarian Timothy Durick travelled from his home in Lackamore, Castletownarra, Co. Tipperary to the nearby town of Nenagh. He made the journey to visit the Post Office and collect his pension, which was worth $8 U.S. Dollars. In order to secure the pension the elderly man had made a long journey across the Atlantic; the service which earned it had been that of his son, Jeremiah- a soldier of the Irish Brigade who’s story came to an end on the bloodiest day in American history. (1)

The Irish Brigade Monument at Antietam (Andrew Bossi- Wikimedia Commons)

Timothy Durick had been born around the year 1801. He married Mary Hogan in 1827 and the couple went on to have five children together. The dangers of childbirth were everpresent in this period, and Mary did not long survive the birth of their fifth child- Timothy became a widower at sometime during the early 1840s. The family were poor and there were few prospects in Ireland for the children. Timothy and Mary’s son Jeremiah had been born around 1835, and by the mid-1850s had decided that his future lay in the United States. (2)

As was so often the case with Irish emigrants, when Jeremiah went to America he chose to join people whom he already knew and who were originally from the Nenagh area. He settled in the town of West Rutland, Rutland County, Vermont, where he boarded with John Barrett, who had known him since he was a boy and had attended his mother’s funeral. There Jeremiah worked in the marble quarries, making sure to send his father in Ireland money whenever he could. (3)

Marble Mills in West Rutland, Vermont as they appeared c. 1915 (Wikipedia)

With the outbreak of the war, Jeremiah, who had found work sporadic in Vermont, decided to enlist in army. The regiment he chose was the 88th New York Infantry, one of the units of the Irish Brigade. He mustered in as a Private in Company C on 28th September 1861, aged 26 years. A steady wage seems to have been one of Jeremiah’s key motivating factors in joining up, and his father back in Nenagh remained in his thoughts- at one point he sent $30 of his pay to Ireland via his brother John. (4)

Jeremiah served with the Brigade through the Peninsula before marching onto the field at Antietam on 17th September 1862. Captain William O’Grady of the 88th later described that regiments part in the action:

‘We forded the creek, by General Meagher’s orders, taking off our shoes (those who could, many were barefoot, and some, like the writer, were so footsore that they had not been able to take off their shoes, or what remained of them, for a week), to wring out their socks, so as not to incumber the men in active movements, and every man was required to fill his canteen…The bullets were whistling over us as we hurried past the general in fours, and at the double-quick formed right into line behind a fence. We were ordered to lie down while volunteers tore down the fence…Then, up on our feet, we charged. The Bloody Lane was witness of the efficacy of buck-and-ball at close quarters. We cleared that and away beyond…When our ammunition was exhausted, Caldwell’s Brigade relieved us, the companies breaking into fours for the passage as if on parade…By some misunderstanding, part of the Sixty-third New York with their colors were massed on our right for a few minutes, during which our two right companies, C and F, were simply slaughtered, suffering a third of the entire casualties of the regiment. (5)

Jeremiah Durick was one of the unfortunate members of Company C caught in this exposed position. He was killed on the field, one of 35 men of the regiment who lost their lives as a result of Antietam. Another 67 were wounded as the 88th New York lost, according to Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Kelly, ‘one-third of our men.’ (6)

Confederate Dead in the Bloody Lane, Antietam, the Target of the Irish Brigade Attack (Library of Congress)

In April 1867 Jeremiah’s father Timothy, now 66-years-old, sought to secure a pension based on his son’s service. His previous efforts in this regard had been unsuccessful, and so he made the journey across the Atlantic to Vermont to press his claim. Old friends from Nenagh who lived in Vermont, 40-year-old John Barrett (with whom Jeremiah had boarded) and 50-year-old John Gleason, gave evidence that Timothy had received upwards of $100 a year in financial support from his son. They also revealed that Timothy was very poor, had no property of any kind except his personal clothing and had no income or means of support except what he earned by manual labour. Timothy was reported to be in poor health and was unable to earn a living due to physical disability. A Dr. Backer Haynes in the town of Rutland also provided a statement to say he had examined Timothy, and found that he suffered from long-standing hypertrophy of the heart which had caused rheumatism in the back, right arm and right shoulder. These ailments rendered him ‘entirely incapable of earning a subsistence by manual labor’ and had done so for at least five or six years. Timothy’s pension application was approved in March 1868. (7)

An Extract of the Statements Provided by John Barrett and John Gleason for Timothy Durick (John Barrett could sign his name, John Gleason was illiterate so made his mark- Image via Fold3)

Timothy remained in Vermont for some time after securing his pension, living in Castleton. In November 1868 he sought to have the pension back-dated to the time of his son’s death in 1862, although it is unclear if he was successful. Timothy eventually made the journey back to his home in Tipperary and by 1883 was collecting his pension from Nenagh Post Office. Despite his ailments he lived well into his 80s, eventually passing away near Nenagh in 1887 at the age of 86. His son’s service, which had ended in Maryland on America’s bloodiest day, helped to provide vital financial assistance for an elderly man living out his final years a world away, in rural Co. Tipperary. (8)

Timothy Durick’s Mark from his November 1868 Application (Image via Fold3)

(1) Griffiths Valuation, Pensioners on the Roll:640; (2) Jeremiah Durick Widow’s Pension File; (3) Ibid. (4) Adjutant General Report: 42; Jeremiah Durick Wodow’s Pension File; (5) O’Grady 1902; (6) Phisterer 1912, Official Records: 298; (7) Jeremiah Durick Widow’s Pension File; (8) Ibid., Civil Registrations;

References & Further Reading

Government Printing Office 1883. List of Pensioners on the Roll January 1, 1883. Volume 5

Ireland Civil Registration Deaths Index, 1864-1958; Nenagh Registration District

Ireland Griffith’s Valuation, 1848-1864; Owney and Arra, Co. Tipperary

Jeremiah Durick Widow’s Pension File WC109831

New York Adjutant-General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York, Volume 31

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 19 (Part 1). Report of Lieut. Col. Patrick Kelly, Eighty-eighth New York Infantry, of the battle of Antietam

Phisterer, Frederick 1912. New York in the War of the Rebellion

New York State Military Museum

Civil War Trust Battle of Antietam Page

Antietam National Battlefield Park

Filed under: 88th New York, Irish Brigade, Tipperary, Vermont Tagged: Battle of Antietam, Co. Tipperary, Irish American Civil War, Irish Military Pensions, Nenagh, Nenagh History, Pensioners on the Roll, Widow's Pension Files

December 6, 2013

How To Find American Civil War Veterans from Irish Counties: A Case Study of Mathew Dooley, Roscrea