Damian Shiels's Blog, page 43

September 6, 2014

Remembering James Sharkey: The Final Letters of an Irish-American Boy

As regular readers of the blog will know, I spend a lot of time looking through Civil War Widow’s & Dependent’s Pension Files. Many of these files contain original letters written home by soldiers during the war. Having spent a number of months compiling a database of Irish-American letters from men in New York regiments, I am now in the process of transcribing them with a view to future publication. Each of the men whose letters I transcribe have one thing in common- all died as a result of their service. I must admit, I find it extremely difficult to remain detached from the stories that leap from these letters. These men often poured their hopes, their dreams and their fears into them; reading each one in the certain knowledge that their life was extinguished during the conflict is an emotionally charged experience. It has certainly increased my determination to see that they and their families- Ireland’s forgotten emigrants- are finally remembered at home. This weekend I have transcribed three letters relating to Irish-American Private James Sharkey of the 21st New York Cavalry, all of which were written home to his mother in September 1863. Seldom has the character of a man emerged so powerfully from the page; hard-working, jovial, fun, determined, loving- and extremely young. I wanted to share some of his character with you, that he might be remembered.

Staten Island and the Narrows c. 1861. James Sharkey wrote home to Rochester from Staten Island. (Library of Congress)

James Sharkey’s parents Martin and Margaret (née Gibbon) were married in Ireland on 14th December 1837 by Father Peter O’Connor. In the early 1840s they emigrated to Canada, where they settled and where their first two children were born. In a move common for Irish emigrants, after a few years they moved on to the United States, where they decided to live in Rochester, New York. It was in Rochester that their third child James was born, the first of a further six additions to arrive.

James Sharkey was probably seventeen years-old when he enlisted in Rochester, New York on 11th August 1863. He was mustered as a private in Company C of the 21st New York Cavalry on 28th August 1863. That September he sent at least three letters home to let his mother know how he was faring in the army. When he joined up, James was still learning how to write and clearly intended to practice as much as possible while in the military. He proudly proclaimed to his mother that ‘I can spell prety good now and I studing to read every day’.

A number of themes are apparent across James’s letters. He quickly grew fond of the military life, and thought it was good for him. Writing from Camp Sprague, Staten Island on 4th September, a week after he mustered, James told his mother ‘we are having a goodtime here and we are enjoying ourselves fine we have plenty to eat and drink and nothing to do but to drill once a day and parade once a day and that does not amount to over one hours work a day my health is good and I am getting fat as a bear.’ The next couple of weeks didn’t change things, as on 18th September he was ‘engoing [sic.] myself we get plenty to eat I get as fat as a dog’. It wasn’t all plain sailing, though. On the 20th he admitted that ‘we have not hat it very hard yet’ but that ‘once or twice we did not get anough to eat wich I did not like…’.

The strictures of the army were something James was having to get used to. When his mother wrote to tell him of a party that was soon to take place in Rochester, he wasn’t pleased, clearly unhappy at the prospect of missing out: ‘I did not like you have tolt me of that party I would like to be there myself once more but I canot do it as you know’. Perhaps one of the reasons he was sore at missing it was because of a certain young woman- Mary Ann Gilligan. Mary Ann was the daughter of Irish tailor John Gilligan and lived in Rochester’s Sixth Ward. Born in Ireland, she was 20-years-old in 1863 and seems to have been a friend of James’s 21-year-old sister Kate (who had been born in Canada). James had told his mother to be sure and ‘give my love to Mary Ann Giligan and Kate and tell them I want the matching they was going to give me.’ James had left two ‘phortographs‘ he had taken of himself in Rochester, and asked to have Kate write to her ‘with her phortograph I hope that I will get it and Mary Ann Gilligan phortograph I would like to have two.’ Perhaps most telling, on 18th September James asked his mother to ‘tell Mary Ann Gilligan my best respects and tell her that I am very sory that I could not dance the divel out of her [perhaps alluding to the party] tell her that I waiting every day for them phortographs.’

Despite the fact that he was missing many aspects of life at home, the camp at Staten Island held some charms, particularly given its proximity to New York City- a city the size of which James had never seen. On the 20th he wrote ‘this is a nice place I hat a pass to go to New York yesterday and I was lost in the city it is a very large city and I hat a lots of fun there.’ He was also making friends, particularly with one of the other Rochester boys, 20-year-old ‘Jony Lynn’ (probably John Ling on the regimental roster, recorded as deserting on 6th October 1863) who he described as ‘just like a brother to me’. But James knew he wouldn’t be at Camp Sprague forever. Rumours were rife as to the regiment’s ultimate destination, and Texas topped the list. It was not something that he was enthusiastic about: ‘we expect to go to Washington in a few days and then to Texas to fight with the Indians I do not like to go to Texas for it is a prety hard place to go two.’

James’s letters also reveal that money was often tight at the family home in 15 Mount Hope Avenue. His father Martin had been unable to support the family properly since 1857, when a fall from a building during construction work on the 4th November 1854 severely damaged his right hip. From then on, the responsibility for earning enough for the family to survive had fallen on the Sharkey’s eldest children. Prior to his enlistment James had already spent eight years working in the local nursery, run by Patrick Barry (suggesting he started employment there around the age of nine) and giving all his wages to his parents. When he joined up in 1863 he was following in the footsteps of his older brother John, who was already earning a regular wage in the army. The straitened circumstances of the war had meant his father had again had to seek out work, despite his lameness. On 18th September James wrote that he was ‘glad to hear that Father is going to work in the nursery’ (presumably the same nursery where James had been employed). He continued: ‘Dear Mother I think you must be prety hard up for mony but you must not be discuraged for you know if I was home I wuld give you some mony once in wile.’ He promised to send ’60 Dollars wich will come good for you this winter and then Jony will sent you some’ and encouraged her to ‘tell father to work for he knows he has not much help’. James hints at the fact that his father may have struggled with the impact of his disability. It seems his mother wrote to him lamenting that so many of her children were no longer at home, to which James responded: ‘Dear Mother you must have a kind of open Heart to have 4 of us left from home but you cant blame us for Father is so mean to us that we have to leave home. Dear Mother there is no use in crying spoiled milk for we will all be home again for this war will be over before long.’ He added, ‘Dear Mother you have tolt me to trust in god I will do it and I have a prayer book and I say my prayers every night.’

Unfortunately James’s war was over before long. The rumours of the regiment move to Texas had proved false- James and his comrades were instead bound for Washington D.C. and then Virginia. On 26th October 1863- less than two months after James Sharkey had mustered into the 21st New York Cavalry, and only a month after his last letter, his mother Margaret received the following:

Camp Stoneman DC Oct 26/63

Mrs Margaret Sharkey

It is my painful duty to inform you that your son James Sharkey of Co C 21 NY Vol Cavy died on Saturday Evening Oct 24th at the General Hospital of this Camp of Malignant Typhoid fever after an illness of about eight days.

I can assure you that in all the circumstances attending his illness he showed a remarkable patience and in all ways displayed a desire to give but little trouble to those around him. As a soldier, though so young, he was remarkable for his willing and cheerful attendance to duty, and I cannot but sympathise deeply with you in your loss of so good a son.

His death surprised us all. I had no idea that he was so near his end, and had charged the Surgeon on friday to notify me in case he should become dangerous- be promised to do so and seemed much surprised himself at the rapid progress made by the disease, when it was too late to arrest its progress.

The men of Company C have had the body embalmed and sent home for burial, thinking it may be a poor comfort to you his mother to have his body resting near your own- It is all the sympathy they can show you in your sorrow, but it is honest and earnest.

James had not an enemy in the company and altho’ he has not been permitted to yield up his life on the field of honor yet the sacrifice is none the less glorious- His lifes strength has been yielded up in the cause of Humanity, Liberty and Godliness and his reward is reached. Let his memory be kept ever green as one of the patriot martyrs of the day.

His effects have been forwarded to you with his body. Some $75 of Bounty remains sue to him from the Government and pay from the 11th July at $13 per month the Govt therefore owes him $120.00 as follows:

Bounty $75.00

Pay $45.06

Total $120.06

Which you can get by applying thro the Sanitary Commission, without charge- let me advise you to apply thro the agent of that society instead of going to Lawyer agents.

His clothing & c are here they are not worth sending home. Should there be anything amongst his effects worth sending to you it will be forwarded by Express.

Hoping that you may be sustained and comforted in your day of affliction by “He that tempers the wind to the Shorn Lamb” and that you may finally meet those called before in a happier and better Land I remain

Truly Your Friend

John S Jennings

Capt Co C 21 Reg NY Cavy

Washington D.C.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

James Sharkey Widow’s Pension File

1860 US Federal Census

New York Adjutant General Roster of the 21st New York Cavalry

Filed under: New York Tagged: 21st New York Cavalry, Civil War Widow's Pension Files, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Emigrants, Irish History, New York Irish, Rochester Irish

September 4, 2014

Storify: The #ForgottenIrish of Co. Kerry

The second Irish county to be covered as part of the #ForgottenIrish campaign on Twitter was Co. Kerry. This follows on from the first featured county, which was Cork. As promised for those of you not on the platform, I will continue to use Storify to bring together the tweets on each county in one place, and combine them with related images, videos and websites that help to fill out the experiences of some of these Irish people during the period of the Civil War. If you are interested in seeing the Kerry story you can do so by clicking here. The third #ForgottenIrish county, Donegal, was featured on Twitter last night and will be the subject of a Storify post which I will share here in the coming days.

Filed under: Digital Arts and Humanities, Kerry Tagged: Bear Creek Massacre, Boston Pilot, Forgotten Irish, Irish American Civil War, Irish Medal of Honor, Kerry and the American Civil War, Kerry Soldiers, Kerry Veterans

September 1, 2014

Witnesses to History: A Bounty List of the 170th New York, Corcoran’s Irish Legion

This is the first in a new series of posts on the site which seeks to tie surviving American Civil War objects to the stories of those people associated with them. Surviving objects from the Civil War era are tangible links to the past- they served as ‘witnesses to history.’ I have long been fascinated by the ability that objects have to guide our hand in uncovering the stories of past peoples, while simultaneously increasing our affinity and sense of connection with those who came into contact with them. Now, thanks to my good friend and Civil War expert Joe Maghe, we have an opportunity to explore some of the remarkable objects from Joe’s collection on the site. This first instalment examines a document which lists a small group of men in Corcoran’s Irish Legion, providing a snaphshot of the 170th New York Infantry in October 1862 and allowing us to ask, what was their fate?

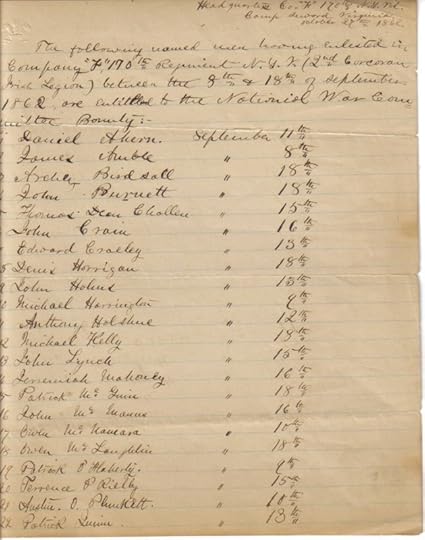

The first page of the 170th New York Infantry Bounty List of October 1862 (Copyright: Joe Maghe Collection)

The document in Joe’s collection is relatively plain- a short list of men across two pages. It is dated October 27th 1862 and relates to men of Company F of the 170th New York. Addressed ‘Camp Seward Virginia’ it introduces itself as follows:

The following named men being enlisted in Company “F” 170th Regiment N.Y.V. (2nd Corcoran Irish Legion) between the 8th & 18th of September 1862 are entitled to the National War Committee Bounty…

There follows a simple list of 27 names with the dates of their enlistment. This document is fascinating, as it captures a single moment in time, a single event in these men’s lives. When it was written, in October 1862, the Legion had yet to see major action- all these men were still alive, still new to soldiering. Indeed it seems probable that for at least some of them this bounty and the steady wage the army offered was a major reason for the decision they had taken only a little over a month before. For others on these pages, ideological reasons may have played a part in them donning Union blue. Whatever their original motivations, by October all were now ‘in it together.’

A document such as this offers us the opportunity to examine what became of each of these men- who survived, who deserted, who was maimed or killed in the years to come? Using a combination of the rosters of the 170th New York, the Civil War Veterans Pension Index Cards, a selection of Widow’s Pension Files and Joe’s previous work on the document, I have sought to flesh out some details of their lives in the army, and for a small number of them reveal something of they and their family’s pre and post-war experiences. Each man is listed below in the same order in which they appear on the original document.

The second page of the 170th New York Infantry Bounty List of October 1862 (Copyright: Joe Maghe Collection)

Daniel Ahern

The 42-year-old enlisted on 11th September 1862, mustering in as a Private in Company F. He was captured at the North Anna on 24th May 1864, dying of diarrhoea on 31st July 1864 at Andersonville, Georgia. Daniel’s widow received a pension for his service from 23rd June 1865.

James Amble (also borne as Ambler)

The 29-year-old enlisted on 8th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. He was wounded in action at the Landron House on 18th May 1864 an engagement in which he lost his arm. He was still absent wounded in Central Park Hospital, New York when the regiment mustered out in 1865.

Archie Birdsall (also borne as Archie L. Birdsall)

The 18-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862, becoming a Private in Company F. He deserted on 1 November 1862 at Camp Seward, Arlington Flats, Virginia.

John Burnett

The 43-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. When he was mustered out on 17th July 1865 he was in hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. John received an invalid pension based on his service from 22nd May 1876 and following his death a pension for a minor child was also claimed.

Thomas Dean Challen

The 23-year-old enlisted on 15th September 1862. Initially a Private in Company F, he was promoted to hospital steward on 24th April 1864, and mustered out with the regiment near Munson’s Hill, Virginia on 15th July 1865.

John Crain (also borne as Crane, Croin and Crean)

The 19-year-old enlisted on 16th September 1862. A Private in Company F, he was wounded on 24th October 1864, but recovered to be mustered out with his company near Washington D.C. on 15th July 1865.

Edward Craely (also born as Crealey, Crawlet, Creally and Crawley)

The 42-year-old enlisted on 13th August 1862. He served as a Private in Company F. When he mustered out on 27th July 1865 he was in Armory Square Hospital, Washington D.C. He sought an invalid pension based on his service on 4th March 1871 but this appears to have been rejected.

Denis Horrigan (also borne as Horigan)

The 28-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862, serving as a Private in Company F. He was mustered out with his company on 15th July 1865 near Washington D.C. He received an invalid pension from 22nd November 1890.

John Holmes (also borne as Holms)

The 40-year-old enlisted on 13th September 1862, and became a Private in Company F. He was listed as a deserter following the expiration of a furlough on 24th March 1864 at Devereaux Station, Virginia.

Michael Harrington

The 36-year-old enlisted on 9th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. He was killed in action at the North Anna on 24th May 1864. Michael’s widow Mary (née Mahon) received a pension from 2nd September 1865. She lived at 57 Baxter Street in New York and listed her age as 50 when she first applied for the pension in 1864. The couple had been married in St. Peter’s Catholic Church, New York on 7th January 1856 by the Reverend Mr. Quinn. When Michael died he left one child, Catherine, who had been born in the late 1850s.

Anthony Holshue (also borne as Holschzhuh)

The 40-year-old enlisted on 12th September 1862 and served as a Private in Company F. He died of paralysis at Suffolk, Virginia on 12th February 1863. He was said to have contracted the paralysis while on picket duty that January, a result of severe hardship and fatigue. Anthony’s widow Sophia (née Bertsch) received a pension dated from 23rd July 1863. Anthony (Anton) was originally from Niederhofen in Württemberg, while Sophia was from Eberstadt, also in Württemberg. His death left the family ‘helpless’, leaving only his ‘old uniform cloths’ and a likeness of his young son behind. The couple had been married on 23rd April 1855 at the German Universial Christian Church in New York; Sophia had travelled from her home in West-Hoboken for the ceremony to marry Anton, who was a widower. It seems likely Anton had lied about his age to enlist in 1862; his marriage record of 1855 records his age as 43, suggesting he was more likely 50-years-old upon enlistment. Sophia was living in Hudson City, New Jersey when she applied for the pension in 1863, at the age of 32. The couple had two surviving children in 1863- Sophia (aged seven and born 31st December 1855 in Hoboken) and John (aged five). John did not long outlive his father, dying in New York on 5th February 1866 at the family home of 261 Avenue A in New York.

Michael Kelly

The 21-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862, becoming a Private in Company F. He was wounded in action at Petersburg on 22nd June 1864 and never returned to his company. He was absent sick when it mustered out in 1865.

John Lynch

The 37-year-old enlisted on 15th September 1862 and initially served as a Private in Company F. He was promoted to First Sergeant on 7th October 1862, Second Lieutenant on 1st February 1863 and First Lieutenant on 10th April 1863. John was discharged from service on 5th October 1863.

Jeremiah Mahoney (also borne as Mohoney)

The 18-year-old enlisted on 16th September 1862, becoming a Private in Company F. He was wounded in action at Petersburg on 16th June 1864, never returning to his company. He was absent in hospital when they mustered out in 1865. He filed for a disability pension resulting from his service on 12th February 1866 which was granted.

Patrick McGuin (also borne as McGinn, McGraw)

The 43-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. He was reported missing in action at the Battle of Ream’s Station on 25th August 1864, returned from hospital and was transferred to the 129th Company, 2nd Battalion of the Veteran Reserve Corp on 1st January 1865. He was discharged for disability at Finley Hospital, Washington D.C. on 3rd March 1865. Patrick died on 14th October 1875 and his widow claimed a pension based on his service from 21st July 1890.

John McManus

The 45-year-old enlisted on 16th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. He was recorded as deserted on 24th March 1864 at Union Mills, Virginia, having never returned at the expiration of a furlough.

Owen McNamara

The 43-year-old enlisted on 10th September 1862 and became a Private in Company I. He deserted on 9th October 1862 at Camp Scott, Staten Island, New York Harbor.

Owen McLoughlin (also borne as McLaughlin and McGlaughlin)

The 31-year-old enlisted on 18th September 1862, becoming a Private in Company F. He was wounded at the Battle of the North Anna on 24th May 1864 and again at the Battle of Ream’s Station on 25th August 1864. He never returned to his Company, and was recorded as absent wounded in hospital at muster out in 1865. However, it appears he had in fact died of his wounds; a widow’s pension was filed but rejected on 14th December 1864 but a subsequent minor child’s application was granted.

Patrick O’Flaherty (also borne as Flaherty)

The 42-year-old enlisted on 9th September 1862. He initially became a Private in Company F but was transferred to Company D of the 14th Veteran Reserve Corps on 7th September 1863. He mustered out with them at Washington D.C. on 20th July 1865

Terrence O’Reilly (also borne as O’Rielly, Reilly)

The 38-year-old enlisted on 15th September 1862, becoming a Private in Company F. He died of cholera on 19th September 1863 at Centreville, Virginia, having first taken sick while on picket duty. His 41-year-old widow Mary (née Cooney) successfully applied for a pension on 19th December 1864 from her home at No. 385, Second Avenue in New York. The couple had been married by the Reverend Matthew McQuade at Kill, Co. Cavan on 17th February 1846. They emigrated soon afterwards, as their daughter Catharine had been born in New York on 10th April 1847, and baptised in the Church of the Nativity on Second Avenue. A second daughter, Mary-Ann, was born around 1852 but did not survive to adulthood. Mary was described as a ‘poor woman with a sick child’ in 1866.

Augustin O. Plunkett (also borne as Austin O. (Oliver) Plunkett)

The 21-year-old enlisted on 10th September 1862, initially becoming a Private in Company F. He was promoted Sergeant to date from 10th September 1862 and Sergeant-Major on 10th June 1864. Augustin actually assisted as a Sergeant in recruiting a number of other men on the list in September 1862, including Terrence O’Reilly. Augustin was wounded at the Battle of Ream’s Station on 25th August 1864, and was retransferred to become a Private on 20th November 1864. He was thereafter absent from his company, serving in the quartermaster’s department at City Point, Virginia from 21st November 1864. Augustin was discharged as a Sergeant-Major on 28th July 1865 in New York City. He applied for pensions on 19th June and 26th February 1907 and was credited with additional service in the Navy. He died on 3rd February 1932.

Patrick Quinn

The 42-year-old enlisted on 13th September 1862 and became a Private in Company F. He was reported missing in action at the Battle of North Anna on 24th May 1864 and was subsequently absent in hospital, where he remained at the muster out of the company in 1865.

John Sheehan

The 43-year-old enlisted on 11th September 1862. A Private in Company F, he was captured in action on 25th August 1864 at the Battle of Ream’s Station. John died while a Prisoner of War on 20th September 1864 at Andersonville, Georgia. A minor pension was granted based on his service following an application by Dennis Sheehan on 25th June 1866 from No. 167, Seventh Avenue, New York. John Sheehan had been married to his wife Ann (née Callaghan) in Co. Limerick by the Reverend Father Burke on 25th November 1835. Ann contracted meningitis and died at the age of 41 in Bellevue Hospital on 21st September 1863, while her husband was in the service. She was buried in Calvary Cemetery. When John died a Confederate POW the following year, it left their children orphaned. Of the couple’s six children (Joseph, Margaret, Mary, Dennis, Anne and Michael) two were minors when John died. These were Michael, born on 28th September 1856, and Anne, born on 31st July 1860. It was their elder brother Dennis, aged 22 in 1866, who took the two minors in and applied for the minor pensions in their name.

Charles Sheridan

The 23-year-old enlisted on 9th September 1862. He was promoted to Corporal in Company F on the same day of his muster in on 7th October 1862, and became a Sergeant on 1st July 1864. He was returned to the ranks on 20th June 1865 prior to mustering out with his company on 15th July 1865 near Washington D.C. He was later granted an invalid pension based on his service, having applied on 17th January 1881.

John Webb

The 26-year-old enlisted on 13th September 1862. A Private in Company F, he was wounded in action on 3rd June 1864 at the Battle of Cold Harbor. John was subsequently transferred to Company F of the 19th Regiment, Veteran Reserve Corps on 24th January 1865. He mustered out on 4th August 1865 at Buffalo, New York.

John Wicks

The 22-year-old enlisted on 8th September 1862. A Private in Company F, he was promoted to Corporal at a date prior to 10th April 1863. John was captured at the Boydton Plank Road on 27th October 1864, and died a Prisoner of War at Richmond, Virginia on 15th February 1865.

John Brown

Three men in the regiment bore the name John Brown, all of whom enlisted in September 1862 and all of whom served in Company F. This one is the 32-year-old John Brown, who deserted on 14th October 1862 from Camp Scott on Staten Island, New York Harbor.

Soldiers of the 170th New York Infantry, Corcoran’s Irish Legion during the Civil War (Library of Congress)

**This series of posts is only possible thanks to the generosity of my good friend Joe Maghe. Joe’s dedication to preserving objects relating to the Irish experience of the American Civil War is exceptional and is matched by his knowledge regarding the men who once possessed them. Thanks to his efforts a huge swathe of material relating to the Irish of the American Civil War has been made available to those researching the conflict.

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

New York Adjutant General, 1905. Roster of the 170th New York Infantry

Civil War Soldiers & Sailors Veteran Pension Index

Civil War Widows & Dependents Pension Files

Filed under: 170th New York, Cavan, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Limerick Tagged: 170th New York Infantry, Civil War Widow's Pensions, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Germans in Irish Regiments, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish-US History, New York Irish

August 23, 2014

Storify: The #ForgottenIrish of Co. Cork

I have been using Twitter quite frequently as part of my efforts to raise awareness in Ireland of Irish participation in the American Civil War. One recent example was the stories of 41 Civil War Pensioners in Ireland which were told using the platform over the course of a weekend. This was recently featured in Civil War Times magazine. I have since developed the #ForgottenIrish hashtag, which I am currently using to highlight the connections of different Irish counties to the Civil War. Conscious that many of my readers do not use Twitter, I am going to regularly ‘Storify’ these tweets; this also allows you to read them and also facilitates the integration of different forms of media relevant to the storyline, such as youtube lectures, images and webpages. The first of these focuses on the #ForgottenIrish of Co. Cork, which you can now view on Storify by clicking here.

Filed under: Cork, Digital Arts and Humanities Tagged: Boston Pilot, Cork Veterans, Forgotten Irish, Information Wanted Advertisements, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Patrick Cleburne, Walter Paye Lane

August 18, 2014

‘The Hard Industry of My Own Hands': Three American Civil War Widows in Ireland Struggle to Survive

On the face of things, Irishwomen Honora Cleary, Eleanor Hogg and Maria Sheppel had little in common. For a start, they were from different parts of Ireland; Honora hailed from Cappoquin, Co. Waterford, Eleanor lived in Boyle, Co. Roscommon and Maria had grown up in Ballinasloe, Co. Galway. Neither did the women share the same religion; Honora and Eleanor were Roman Catholic, while Maria was Church of Ireland. What they did share was that all were married with children, all were illiterate, and all were extremely poor. All three were also specifically referred to in correspondence that U.S. Consul William West sent to America in July 1865. The reason for this was that they had all had suffered the same experience; each of their husband’s had died while in Union service on the other side of the Atlantic.

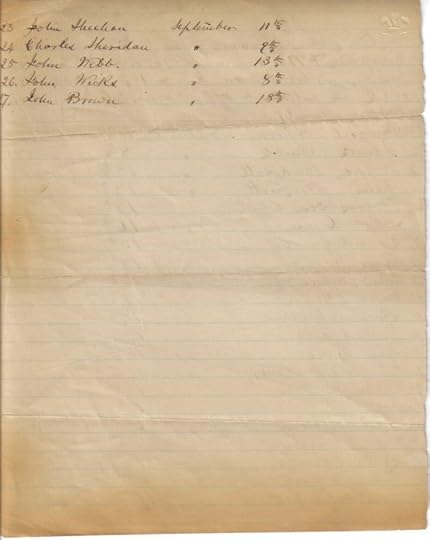

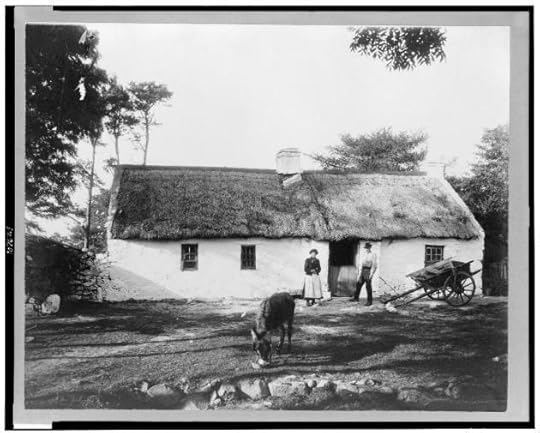

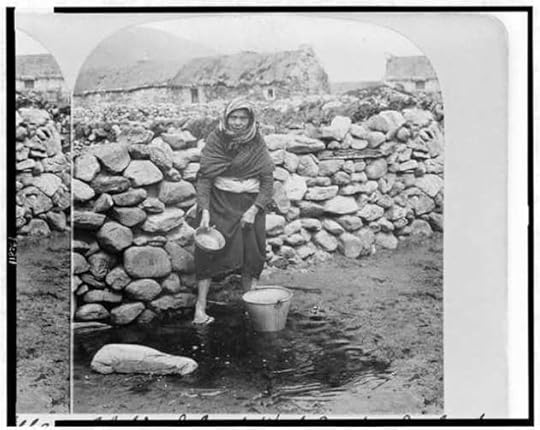

Separation. Many Irish families could not afford to emigrate together. For whatever reason, all three of these women’s husbands left their family’s and home for America, never to return (Library of Congress)

U.S. Consulate Dublin & Galway July 31st 65

The Hon J. H. Barrett

Commr of Pensions

Washington US

Sir

I have the honor to send you herewith the Army Pension Claims of three Widows of our decd soldiers viz Honora Cleary, Eleanor Hogg and Maria Sheppell, none of whom you will perceive can write and being also extremely indigent in fact w.o. be in the Poor House but for the pay due to their husbands which I have obtained & paid to them you can imagine the difficulty in getting the necessary information from such people. I trust therefore you will, if possible, kindly overlook any defects or deficiency in them, which I have done all in my power to avoid, and by advising Mr. Hudson of their rect. You will oblige

yrs Obedly Wm B. West Consul

There is no reason to believe that any of these women ever set foot in the United States. Indeed these Civil War widows were still making their homes in the same localities where they had led most of their lives. Eleanor (née McDonagh) had been the first of the women to marry, when she wed farmer Farrell Hogg of Corskeagh, Co. Sligo at Riverstown Catholic Church on 21st September 1835. Next had been Honora (née Browne) and Francis Michael Cleary, who tied the knot at Cappoquin Catholic Church in Co. Waterford on 21st August 1843. Maria Galvin began her life with whip maker Nicholas Sheppel in the Church of Ireland Church of Ballinasloe, Co. Galway on 5th October 1846.

Not long after their marriages each of the three women had started families. Nicholas and Maria Sheppel had at least six children: Bedelia (1848), Henry (1851), Esther (1854), Catherine (1856), Peter (1858) and Elizabeth (1863). Francis Michael and Honora Cleary had three children who survived infancy: Francis (1844), John (1847) and Thomas (1848). Like the Sheppels, the Hoggs also had six children, although we only have the names of four: Patrick (18??), Catherine (1839), John (1842) and Farrell Jr. (1851).

The Camp of the 6th New York Heavy Artillery at Brandy Station, April 1864. Nicholas Sheppel was in the regiment when this image was exposed (Library of Congress)

Why did their husband’s leave for America? None of the women claimed that they had been deserted; Eleanor Hogg remarked that she got regular correspondence from her husband, who had journeyed to the United States ‘several years’ before 1862. Although Honora Cleary does not specify the reason behind her husband’s departure, he had emigrated by 1858. The only woman whose husband actually traveled to America during the war was Maria Sheppel; the couple’s last child was born in Galway in 1863. Perhaps her husband Nicholas was seeking to take advantage of the late war enlistment bounties, but it seems likely that all three of the men made their choices for economic reasons, and perhaps were hopeful of sending for their wives later on.

Whatever their initial motivations for emigration, each of the women’s husbands ended up in the Union army. Francis Michael Cleary from Cappoquin had chosen the life of a professional U.S. soldier in 1858- he lost his life on 27th June 1862 while serving in Company G of the 10th United States Infantry at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. He was 44-years-old. Only two days later, on 29th June 1862, Sligo farmer Farrell Hogg fell wounded at the Battle of Savage Station. In October 1861 the 40-year-old had enlisted in what became Company D of the 88th New York Infantry, part of the Irish Brigade. Farrell was taken prisoner, but died on 5th August while on his way from Richmond to Washington D.C. having been exchanged. Nicholas Sheppel was the youngest of the men when the Galway whip maker enlisted in Company F of the 6th New York Heavy Artillery, at the age of 35, on 4th February 1864. He had likely only been in the United States a matter of weeks. His military career lasted barely four months- by the 16th June he was dead, succumbing to chronic dysentry at Stanton General Hospital in Washington D.C.

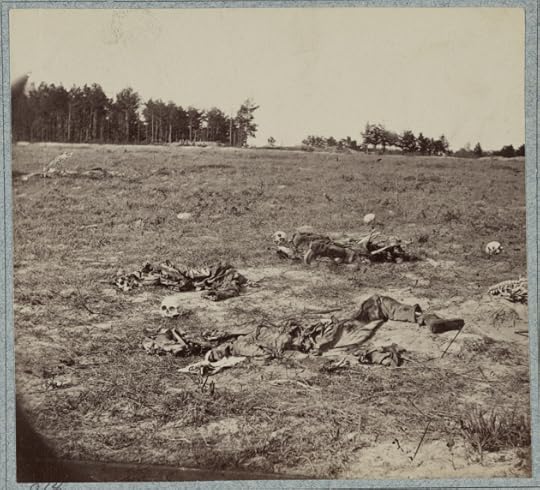

The skeletal remains of the fallen still litter the battlefield of Gaines’ Mill in this image taken later in the war. This was the engagement in which Francis Michael Cleary lost his life (Library of Congress)

We are extremely fortunate that a most remarkable letter relating to one of these families survives. It was written to Eleanor Hogg in September 1862 by her nephew in New York. It is reproduced below as it appears in the original, which highlights the haphazard spelling and punctuation of many emigrant letters from the period (see for example ‘two’, used instead of ‘to’). As Eleanor was illiterate, this must have been read out to her at her home in Ireland, perhaps by one of her children. It is hard to imagine what that experience must have been like, as the letter informed her of not one death, but two. As well as providing her with news of her husband’s fate, it also communicated the death of her son Pat:

New york September 12th 1862

Dear Ant i sit down two write these few lines two you Hoping this will Find you and youre Children in good health As this leaves us all at Present thankes be two god for His Kind Blessence two us all

Dear Aunt i have two Inform you aboute the death Of youre Son patt Hogg he is Dead nine month ago he was Abord of one of the northern vesseles going two orleanes And when he Caim achore Heare in newyorke he got His pay and got thirsti I supose and fell down one Of the Hatchweays of the vessel And teaken away two the Hospitle and died soon After wars i heard nothing of His deathe untill last july Untill i went two his bording Hous two enquire of him his Bording mistrees told me that He was dead

Deare ant i have two inform abaute a worst Newes farrell listed in the Irish brigade that is the 88 regiment newyorke Volenteers he got wond on the 29 of june and died of His wound on the 5 of August He was Captured by ther Enemy when he wir wound Sou the got ther liberty and He died on his way Coming Backe two the Capittel of Washington. Deare ant Farrells his Comrearde wrote a letter Two me after he gitting wonded In cease he would die for me two Cleam his money as i was the nearest reletive two him i wint two head quarters and i steated my Cease two A loyer aboute his mone as i was the neares reletive two him It went in the handes of the Courte Now that the Courte was adgourend unttill i get Answer from this letter

Dear Ant i would have Now delay in getting this money if Patt was living Sou the are Puting me two greate ——– Aboute it. Deare Ant let me Now two the best of your nolege how longe you are marieed and the priests Neam that maried you and Certifie in your letter whiter i can [end of letter]

By the time Eleanor was seeking the Consul’s assistance in securing a pension, in 1865, she was living in Boyle, Co. Roscommon with her remaining children. Maria Sheppel also appears to have moved, leaving Ballinasloe for Galway city. The U.S. Consul described how Maria was ‘in great poverty with sevl young children I have just received a strong appeal from a Banker at Galway on her behalf.’ Honora Cleary was likewise finding times tough for her family in Cappoquin. She later outlined that ‘all this time I had no resource upon with to support these orphans except the hard industry of my own hands.’

Honora Cleary, Eleanor Hogg and Maria Sheppel all ultimately received a Widow’s Pension from the United States government. Their story is another example of the impact this seemingly far away conflict had on people in Ireland, highlighting the fact that the repercussions of the struggle between North and South were not only felt by those Irish who made their homes in America. Unfortunately the heartbreaking experiences of Irishwomen like Honora, Eleanor and Maria- and thousands like them on both sides of the Atlantic- remain all but forgotten in Ireland today.

‘The hard industry of my own hands': Women like Honora Cleary faced a struggle for survival when their husbands died on the other side of the Atlantic (Library of Congress)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

Francis Michael Cleary Widow’s Pension File WC62802

Farrell Hogg Widow’s Pension File WC98727

Nicholas Sheppell Widow’s Pension File WC62799

Filed under: 88th New York, Galway, New York, Pensioners in Ireland, Roscommon, Sligo, Waterford Tagged: 88th New York Infantry, Civil War Widow's Pensions, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Irish Military Pensions, National Archives

August 13, 2014

The Civil War Letters of Captain James Fleming, Part 1: Larne to Canada

In 1832 James Fleming was born to Malcolm and Ann Jane Fleming in Islandbawn, Co. Antrim. The family would later move to nearby Larne when Malcolm established a nursery there, and it was here that James grew up. In 1857 the young man decided to leave Antrim to try his luck in North America. Arriving first in Canada, he eventually made his home in New York. James would go on to serve as an infantry and cavalry officer in the American Civil War- a conflict which ultimately cost him his life. I was recently contacted by one of his descendants, Louise Brown, who has painstakingly transcribed a series of 18 letters written by and regarding James. They offer a remarkable insight into James’s experiences both before and during the war. With Louise’s permission, over the course of the coming a weeks these letters will be shared with you in their entirety.

With the coming of the American Civil War in 1861 26-year-old James Fleming was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the 9th New York Volunteers- Hawkins’ Zouaves. After his two-year term of service expired he was mustered out in May 1863, but he did not spend long out of uniform. On 27th July 1863 James became a First Lieutenant and Quartermaster in the 16th New York Cavalry, subsequently being promoted Captain of Company M. He was killed in action at Fairfax Station, Virginia on 8th August 1864, during an engagement with Mosby’s Rangers. (1)

Provost Guard of the 9th New York Infantry in 1862 (Library of Congress)

James Fleming’s demise did not go unnoticed on either side of the Atlantic. New York newspapers, including the New York Irish-American, carried word of his death, as did the Belfast Newsletter. Neither did his family forget him. The family headstone at the now unused Unitarian Meeting House in Antrim Town bears the following inscription:

Erected by Malcolm Fleming of Larne

For Sara Jane who died in America 1835 aged 33 years.

Also his son James Captain in 16th New York Cavalry who was

Killed at Fairfax by a gang of guerillas 8th Aug 1864

Also Malcolm Fleming 13th Feb 1869 aged 86 years

Also wife Ann Jane died 26th Nov 1869 aged 82 years (2)

Later posts will explore James’s war service through the letters he wrote in 1861, 1862 and 1863. This post contains the first letter in the series, written shortly after James arrived in North America. Dated 29th September 1857, he is writing to let his parents know how his voyage went, what life is like in Canada, and to inquire how everyone is at home:

Post Office

Toronto September 29th/57

Dear Mother

I received your long welcome letter on Saturday last it gives me great pleasure to hear of your all being well as this leaves me quite well at present. You say I gave you no news in my last so I must give you them all this time. When I left Belfast Lough on my outward voyage I felt rather lonely but in a few days I became to like it much better. I assisted the Dr in feeling the old womens pulses and cheering the young ones. My possessions lasted for about 5 weeks there was an old man & his son were in the same place with myself & the young chap cooked for me. I gave away a great deal of my bread to them that I thought required it but Lucky Jim never went hungry to bed for that as I got plenty. The long voyage I need scarce tell you any news concerning it as I could fill a newspaper of my adventures on the voyage but I never had one hours sickness & so I looked after them that was sick. When I got into Quebec I sold Bed & bedding for 6/-. I kept my old Rag a trusty friend I think there were about 6 or 7 nights that it was my Bed & Blanket but that was my own fault. I was counting from Quebec to Toronto – up the canal is most beautiful but indeed I was in no way to enjoy it. I had a very good bed and was very comfortable all the voyage. Sometimes I would have got a tumble out of my birth [sic.] but I had not far to fall as I slept on the bottom birth [sic.]. I am thinking long for such another sail I liked it so well. If I sucede [sic.] here I intend paying Mary Ann a visit in the spring & then my next tour will be to Ould Ireland again the spring following as I am determined on this you will have the satisfaction of seeing me in Larne again. I got a situation in a shop a few days after I arrived but did not get much salary it payed my washing and got me a pair of boots – but I have got a better one in the pantichnetcha [?] same as John Smyth [?]. I have £60 & board but expects to get more after a short time its a sorry place this for young men much worse than Belfast. Canada has not been so dull since it quit sucking or the Christening (I am not sure which) plenty going about doing nothing nor cannot get anything to do of any sort but thank goodness I have had my fill of work since I came here. I am in this place a month its a very comfortable place breakfast at ½ past 7 shop at 8 o’clock get tea fresh meat or eggs, dinner at 1 o’clock tea at 7 shop closes. The grub first rate always 3 or 4 dishes at dinner quite different from home always pies or pudding of some sort or other after dinner. I have a very comfortable bed turns in at 10 o’clock out at 7 aint that good hours never had my health as good. I suppose Alex is quit courting in the Evgs or has he fetched Nancy to the Point yet as Henry says he aught give a chap an invitation if not to the wedding he might to the party in the Evg. If I was there I would give him a hand to beat by Dan yet. I had a paper from Mary Ann that is all as yet she must not have got my letter that I wrote or I would have surely got an answer before this. I am very glad to hear of Thos Luceys as to the increase in his family also his crops doing so well & hopes that Nancy is quite well again. Dear mother you must take better care of yourself for you know that you are not so able to stand the fatigue now as what you were a few years ago. I am glad that my father stands it so well as I suppose he will have the nursery a beautiful place when I come over to see it. You tell me you had a great deal of lightening this summer its myself that sees the lightening one incessant flash for hours its awful in a dark night but we have not much thunder but where it does come it shakes the earth. Fires are very plenty here stunners will burn a whole street before they get it stopped we had a first rate one the other night I had a view of it out of my bedroom window in 3 hours burnt down a whole square of houses. You want to know what sort of churches we have the same as home all sorts there are 2 Unitarians in the city I stroll into some of them sometimes. I am very sorry to hear about Jas Cummings but hopes he will get better. I have not no one that I know from the old Country yet I have not went to see Mr Magee as yet but I heard about him he lives some distance out of the city. I called upon Mrs Renford [?] I dined there a few times she tried to get me into a situation but one must try for themselves when they come to this country. I think I have nothing particular to say we have fine weather at present something like our March weather dry & cold rather warm during midday but cold in the mornings & Evgs, we will have such weather as this to December then frost & snow very severe I believe.

Dear mother I hope you will make Henry take care of himself during this winter if he catches a severe cold it will not be well for him but I hope Andy will look to that as he does in times and not let it settle upon him as it done before. I have had a paper from Malcolm I wrote him but hav not got the answer as yet but hopes to get it soon. Dear mother you can give my kind regards to all inquiring friends as if separately mentioned particularly Mrs Rodgers & Mrs Rankin & sister if you see any one ——– long to hear from tell them I will write them in a few days as yours is the first & then comes the rest as I have time. I must finish my bedfellow is just rolled into bed I am writing this in my bedroom after 10 o’clock. I have nothing now particular to say. Kind love to my father & yourself & hopes you will take care & not slave yourself so much. Kind love to Dunadry folks tell Sally if you see her she might write me a few lines as I have nothing particular or I would write her. I will be writing Andy in a few days I got his & Henry’s letter at the same time as yours & Alex few lines tell Alex to write me a long letter when he gets his harvest saved and let me have all the news. Farewell for the present from your

affectionate Son

James. (3)

*The next set of letters will catch up with James after his move to New York and enlistment in the 9th New York Infantry in 1861. Note that some punctuation has been added to the letter above for ease of reading. Sincere thanks are due to Louise Brown for sharing these letters with readers of Irish in the American Civil War.

(1) New York Adjutant General; (2) Louise Brown Transcription; (3) Louise Brown Transcription;

References

New York State Adjutant General. Rosters of the 9th New York Infantry and 16th New York Cavalry.

Filed under: Antrim, New York Tagged: 16th New York Cavalry, 9th New York Infantry, Antrim Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Mosby Rangers, Ulster Scots Civil War

The Civil War Letters of Captain James Fleming: Part 1

In 1832 James Fleming was born to Malcolm and Ann Jane Fleming in Islandbawn, Co. Antrim. The family would later move to nearby Larne when Malcolm established a nursery there, and it was here that James grew up. In 1857 the young man decided to leave Antrim to try his luck in North America. Arriving first in Canada, he eventually made his home in New York. James would go on to serve as an infantry and cavalry officer in the American Civil War- a conflict which ultimately cost him his life. I was recently contacted by one of his descendants, Louise Brown, who has painstakingly transcribed a series of 18 letters written by and regarding James. They offer a remarkable insight into James’s experiences both before and during the war. With Louise’s permission, over the course of the coming a weeks these letters will be shared with you in their entirety.

With the coming of the American Civil War in 1861 26-year-old James Fleming was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the 9th New York Volunteers- Hawkins’ Zouaves. After his two-year term of service expired he was mustered out in May 1863, but he did not spend long out of uniform. On 27th July 1863 James became a First Lieutenant and Quartermaster in the 16th New York Cavalry, subsequently being promoted Captain of Company M. He was killed in action at Fairfax Station, Virginia on 8th August 1864, during an engagement with Mosby’s Rangers. (1)

Provost Guard of the 9th New York Infantry in 1862 (Library of Congress)

James Fleming’s demise did not go unnoticed on either side of the Atlantic. New York newspapers, including the New York Irish-American, carried word of his death, as did the Belfast Newsletter. Neither did his family forget him. The family headstone at the now unused Unitarian Meeting House in Antrim Town bears the following inscription:

Erected by Malcolm Fleming of Larne

For Sara Jane who died in America 1835 aged 33 years.

Also his son James Captain in 16th New York Cavalry who was

Killed at Fairfax by a gang of guerillas 8th Aug 1863

Also Malcolm Fleming 13th Feb 1869 aged 86 years

Also wife Ann Jane died 26th Nov 1869 aged 82 years (2)

Later posts will explore James’s war service through the letters he wrote in 1861, 1862 and 1863. This post contains the first letter in the series, written shortly after James arrived in North America. Dated 29th September 1857, he is writing to let his parents know how his voyage went, what life is like in Canada, and to inquire how everyone is at home:

Post Office

Toronto September 29th/57

Dear Mother

I received your long welcome letter on Saturday last it gives me great pleasure to hear of your all being well as this leaves me quite well at present. You say I gave you no news in my last so I must give you them all this time. When I left Belfast Lough on my outward voyage I felt rather lonely but in a few days I became to like it much better. I assisted the Dr in feeling the old womens pulses and cheering the young ones. My possessions lasted for about 5 weeks there was an old man & his son were in the same place with myself & the young chap cooked for me. I gave away a great deal of my bread to them that I thought required it but Lucky Jim never went hungry to bed for that as I got plenty. The long voyage I need scarce tell you any news concerning it as I could fill a newspaper of my adventures on the voyage but I never had one hours sickness & so I looked after them that was sick. When I got into Quebec I sold Bed & bedding for 6/-. I kept my old Rag a trusty friend I think there were about 6 or 7 nights that it was my Bed & Blanket but that was my own fault. I was counting from Quebec to Toronto – up the canal is most beautiful but indeed I was in no way to enjoy it. I had a very good bed and was very comfortable all the voyage. Sometimes I would have got a tumble out of my birth [sic.] but I had not far to fall as I slept on the bottom birth [sic.]. I am thinking long for such another sail I liked it so well. If I sucede [sic.] here I intend paying Mary Ann a visit in the spring & then my next tour will be to Ould Ireland again the spring following as I am determined on this you will have the satisfaction of seeing me in Larne again. I got a situation in a shop a few days after I arrived but did not get much salary it payed my washing and got me a pair of boots – but I have got a better one in the pantichnetcha [?] same as John Smyth [?]. I have £60 & board but expects to get more after a short time its a sorry place this for young men much worse than Belfast. Canada has not been so dull since it quit sucking or the Christening (I am not sure which) plenty going about doing nothing nor cannot get anything to do of any sort but thank goodness I have had my fill of work since I came here. I am in this place a month its a very comfortable place breakfast at ½ past 7 shop at 8 o’clock get tea fresh meat or eggs, dinner at 1 o’clock tea at 7 shop closes. The grub first rate always 3 or 4 dishes at dinner quite different from home always pies or pudding of some sort or other after dinner. I have a very comfortable bed turns in at 10 o’clock out at 7 aint that good hours never had my health as good. I suppose Alex is quit courting in the Evgs or has he fetched Nancy to the Point yet as Henry says he aught give a chap an invitation if not to the wedding he might to the party in the Evg. If I was there I would give him a hand to beat by Dan yet. I had a paper from Mary Ann that is all as yet she must not have got my letter that I wrote or I would have surely got an answer before this. I am very glad to hear of Thos Luceys as to the increase in his family also his crops doing so well & hopes that Nancy is quite well again. Dear mother you must take better care of yourself for you know that you are not so able to stand the fatigue now as what you were a few years ago. I am glad that my father stands it so well as I suppose he will have the nursery a beautiful place when I come over to see it. You tell me you had a great deal of lightening this summer its myself that sees the lightening one incessant flash for hours its awful in a dark night but we have not much thunder but where it does come it shakes the earth. Fires are very plenty here stunners will burn a whole street before they get it stopped we had a first rate one the other night I had a view of it out of my bedroom window in 3 hours burnt down a whole square of houses. You want to know what sort of churches we have the same as home all sorts there are 2 Unitarians in the city I stroll into some of them sometimes. I am very sorry to hear about Jas Cummings but hopes he will get better. I have not no one that I know from the old Country yet I have not went to see Mr Magee as yet but I heard about him he lives some distance out of the city. I called upon Mrs Renford [?] I dined there a few times she tried to get me into a situation but one must try for themselves when they come to this country. I think I have nothing particular to say we have fine weather at present something like our March weather dry & cold rather warm during midday but cold in the mornings & Evgs, we will have such weather as this to December then frost & snow very severe I believe.

Dear mother I hope you will make Henry take care of himself during this winter if he catches a severe cold it will not be well for him but I hope Andy will look to that as he does in times and not let it settle upon him as it done before. I have had a paper from Malcolm I wrote him but hav not got the answer as yet but hopes to get it soon. Dear mother you can give my kind regards to all inquiring friends as if separately mentioned particularly Mrs Rodgers & Mrs Rankin & sister if you see any one ——– long to hear from tell them I will write them in a few days as yours is the first & then comes the rest as I have time. I must finish my bedfellow is just rolled into bed I am writing this in my bedroom after 10 o’clock. I have nothing now particular to say. Kind love to my father & yourself & hopes you will take care & not slave yourself so much. Kind love to Dunady folks tell Sally if you see her she might write me a few lines as I have nothing particular or I would write her. I will be writing Andy in a few days I got his & Henry’s letter at the same time as yours & Alex few lines tell Alex to write me a long letter when he gets his harvest saved and let me have all the news. Farewell for the present from your

affectionate Son

James. (3)

*The next set of letters will catch up with James after his move to New York and enlistment in the 9th New York Infantry in 1861. Note that some punctuation has been added to the letter above for ease of reading. Sincere thanks are due to Louise Brown for sharing these letters with readers of Irish in the American Civil War.

(1) New York Adjutant General; (2) Louise Brown Transcription; (3) Louise Brown Transcription;

References

New York State Adjutant General. Rosters of the 9th New York Infantry and 16th New York Cavalry.

Filed under: Antrim, New York Tagged: 16th New York Cavalry, 9th New York Infantry, Antrim Civil War, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Mosby Rangers, Ulster Scots Civil War

August 8, 2014

The 14 Irish Medal of Honor Recipients of the Battle of Mobile Bay, Alabama

On 5th August 1864 a fleet of eighteen Union ships under Rear Admiral David G. Farragut entered Mobile Bay, Alabama on the Confederacy’s Gulf Coast. Their aim was to put the port out of action as a centre for blockade running. The fleet passed under ferocious fire from Forts Gaines and Morgan- and through a minefield- before engaging Confederate vessels, including the ironclad CSS Tennessee. After heavy fighting they won a victory which ultimately led to the closing of Mobile to blockade runners. It also represented an important boost for Abraham Lincoln in the run up to the U.S. Presidential Election. A large number of Union servicemen who participated in the engagement received the Medal of Honor. Among them were 14 Irish-born sailors and marines. The battle, which took place 150 years ago this week, still represents the largest number of Medal of Honor awards to Irishmen for a single action.

The Great Naval Victory at Mobile Bay by Currier & Ives (Library of Congress)

Given that c. 20% of the Union Navy was Irish-born, it is perhaps somewhat surprising how little attention is given to them by those interested in Irish maritime history. Irishmen were spread throughout all the ships of David Farragut’s fleet. The 14 Medal of Honor recipients were likewise positioned on a number of different vessels; they are each recorded below organised by the ship on which they served at Mobile Bay. Where I have been able to locate their original enlistment details I have included physical descriptions of the men. If you would like to read more about the Battle of Mobile Bay itself, see the Civil War Trust page on the engagement here.

U.S.S. LACKAWANNA

USS Lackawanna in action during the Battle of Mobile Bay (Naval Historical Center)

Landsman Michael Cassidy

Born in Ireland in 1837. Formerly a Cook. Blue eyes, brown hair, light complexion, height 5 feet 6 inches. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died in the Soldier’s Home, Hampton, Virginia on 18th March 1908. Buried in Hampton National Cemetery, Hampton, Virginia.

Citation: Served on board the U.S.S. Lackawanna during successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the ram Tennessee, in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Displaying great coolness and exemplary behavior as first sponger of a gun, Cassidy, by his coolness under fire, received the applause of his officers and the guncrew throughout the action which resulted in the capture of the prize ram Tennessee and in the destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.

Landsman Patrick Dougherty

Born Ireland in 1844. Formerly a Cooper. Grey eyes, dark brown hair, florid complexion, height 5 feet 4 1/2 inches. Scar on right middle finger, mole on the right side of neck. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864.

Citation: As a landsman on board the U.S.S. Lackawanna, Dougherty acted gallantly without orders when the powder box at his gun was disabled under the heavy enemy fire, and maintained a supply of powder throughout the prolonged action. Dougherty also aided the attacks on Fort Morgan and in the capture of the prize ram Tennessee.

U.S.S. BROOKLYN

USS Brooklyn (Wikipedia)

Coxswain John Cooper

Born in Co. Dublin, Ireland in 1832. Actual name was John Laver Mather. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on the 22nd August 1891 and is buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

Citation: On board the U.S.S. Brooklyn during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee, in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite severe damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks from stem to stern, Cooper fought his gun with skill and courage throughout the furious battle which resulted in the surrender of the prize rebel ram Tennessee and in the damaging and destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.

John Cooper is one of only nineteen men in the history of the decoration to receive it twice. Cooper’s second medal was presented on 29th June 1865 for the following actions:

Served as quartermaster on Acting Rear Admiral Thatcher’s staff. During the terrific fire at Mobile, on 26 April 1865, at the risk of being blown to pieces by exploding shells, Cooper advanced through the burning locality, rescued a wounded man from certain death, and bore him on his back to a place of safety.

Sergeant Michael Hudson, United States Marine Corps

Born in Co. Sligo, Ireland in 1834. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on 28th December 1891 and is buried at Maple Hill Cemetery, Charlotte, Michigan.

Citation: On board the U.S.S. Brooklyn during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite severe damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked the decks, Sgt. Hudson fought his gun with skill and courage throughout the furious 2-hour battle which resulted in the surrender of the rebel ram Tennessee.

U.S.S. RICHMOND

USS Richmond on blockade duty (Harper’s Weekly via Naval Historical Center)

Coal Heaver William Doolen

Born in Co. Kildare, Ireland in 1841. Blue eyes, brown hair, florid complexion, height 5 feet 4 1/2 inches. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on 14th September 1895 and is buried in Wyoming.

Citation: On board the U.S.S. Richmond during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Although knocked down and seriously wounded in the head, Doolen refused to leave his station as shot and shell passed. Calm and courageous, he rendered gallant service throughout the prolonged battle which resulted in the surrender of the rebel ram Tennessee and in the successful attacks carried out on Fort Morgan despite the enemy’s heavy return fire.

Sergeant James Martin, United States Marines Corps

Born in Co. Derry, Ireland in 1826. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on 29th October 1895 and is buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Citation: As captain of a gun on board the U.S.S. Richmond during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks, Sgt. Martin fought his gun with skill and courage throughout the furious 2-hour battle which resulted in the surrender of the rebel ram Tennessee and in the damaging and destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.

U.S.S. HARTFORD

USS Hartford (Wikipedia)

Coal Heaver Richard D. Dunphy

Born in Ireland, 1840. Blue eyes, black hair, ruddy complexion, height 5 feet 8 1/2 inches. Had smallpox scars. Lost both arms as a result of the engagement. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on 23rd November 1904 and is buried in St. Vincent’s Cemetery, Vallejo, California.

Citation: On board the flagship U.S.S. Hartford during successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the rebel ram Tennessee, Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. With his ship under terrific enemy shellfire, Dunphy performed his duties with skill and courage throughout this fierce engagement which resulted in the capture of the rebel ram Tennessee.

Coal Heaver Thomas O’Connell

Born in Ireland, 1842. Formerly a laborer. Blue eyes, brown curly hair, fair complexion, height 5 feet 8 3/4 inches. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died in New York in 1899.

Citation: On board the flagship U.S.S. Hartford, during successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay on 5 August 1864. Although a patient in the sick bay, O’Connell voluntarily reported at his station at the shell whip and continued to perform his duties with zeal and courage until his right hand was severed by an enemy shellburst.

U.S.S. GALENA

USS Galena cleared for action (Wikipedia)

Seaman William Gardner

Born in Ireland, 1832. A mariner by profession. He had hazel eyes, dark hair and a dark complexion, height 5 feet 9 1/2 inches. Enlisted from New York’s Fourth Congressional district. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Date and place of death unknown.

Citation: As seaman on board the U.S.S. Galena in the engagement at Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Serving gallantly during this fierce battle which resulted in the capture of the rebel ram Tennessee and the damaging of Fort Morgan, Gardner behaved with conspicuous coolness under the fire of the enemy.

Quartermaster Edward S. Martin

Born in Ireland, 1840. Received Medal of Honor on 22nd June 1865. Died on 23rd December 1901 and is buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York.

Citation: On board the U.S.S. Galena during the attack on enemy forts at Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Securely lashed to the side of the Oneida which had suffered the loss of her steering apparatus and an explosion of her boiler from enemy fire, the Galena aided the stricken vessel past the enemy forts to safety. Despite heavy damage to his ship from raking enemy fire, Martin performed his duties with skill and courage throughout the action.

U.S.S. CHICKASAW

USS Chickasaw (Naval Historical Center)

Chief Boatswain’s Mate Andrew Jones

Born in Co. Limerick, Ireland, in 1835. He had hazel eyes, black hair and a dark complexion, 5 feet 5 inches in height. Bore a tattoo with the initials ‘A.J.’ on his left forearm. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Place and date of death unknown.

Citation: Served as chief boatswain’s mate on board the U.S. Ironclad, Chickasaw, Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Although his enlistment was up, Jones volunteered for the battle of Mobile Bay, going on board the Chickasaw from the Vincennes where he then carried out his duties gallantly throughout the engagement with the enemy which resulted in the capture of the rebel ram Tennessee.

U.S.S. METACOMET

The USS Metacomet captures the CSS Selma at the Battle of Mobile (Naval Historical Center)

Boatswain’s Mate Patrick Murphy

Born in Co. Waterford, Ireland in 1823. A long time mariner. He had blue eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion, 5 feet 8 inches in height. Patrick was described as ‘baldheaded’ and ‘corpulent.’ Received Medal of Honor 31st December 1864. Died on 1st December 1896 and is buried in Trinity Cemetery, Erie, Pennsylvania.

Citation: Served as boatswain’s mate on board the U.S.S. Metacomet, during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks, Murphy performed his duties with skill and courage throughout a furious 2-hour battle which resulted in the surrender of the rebel ram Tennessee and in the damaging and destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.

U.S.S. ONEIDA

The USS Oneida portrayed during her sinking off Japan in 1870 (Library of Congress)

Landsman John Preston

Born in Ireland, 1841. Recrding as having no profession on enlistment. He had hazel eyes, black hair and a swarthy complexion, 5 feet 7 3/4 inches in height. Received Medal of Honor 31st December 1864. Date and place of death unknown.

Citation: Served on board the U.S.S. Oneida in the engagement at Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Severely wounded, Preston remained at his gun throughout the engagement which resulted in the capture of the rebel ram Tennessee and the damaging of Fort Morgan, carrying on until obliged to go to the surgeon to whom he reported himself as “only slightly injured.” He then assisted in taking care of the wounded below and wanted to be allowed to return to his battle station on deck. upon close examination it was found that he was wounded quite severely in both eyes.

Sergeant James S. Roantree, United States Marine Corps

Born in Co. Dublin, Ireland in 1835. Received Medal of Honor on 31st December 1864. Died on 24th February 1873 and is buried in Calvary Cemetery, Roslindale, Massachusetts.

Citation: On board the U.S.S. Oneida during action against rebel forts and gunboats and with the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864. Despite damage to his ship and the loss of several men on board as enemy fire raked her decks and penetrated her boilers, Sgt. Roantree performed his duties with skill and courage throughout the furious battle which resulted in the surrender of the rebel ram Tennessee and in the damaging and destruction of batteries at Fort Morgan.

References

US Naval Enlistment Rendezvous, 1855-1891

Lang, G., Collins, R.L., White, G.F. 1995. Medal of Honor Recipients 1863-1995 Volume 1.

Proft, R.J. (ed.), 2002. United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations, Fourth Edition

Civil War Trust Battle of Mobile Bay Page

Filed under: Battle of Mobile Bay, Derry, Dublin, Kildare, Limerick, Medal of Honor, Sligo Tagged: Battle of Mobile Bay, David Farragut, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish in the Navy, Irish Medal of Honor Recipients, Medal of Honor Ireland, Mobile Bay Medal of Honor

August 7, 2014

The Irish Nanny in the (Other) White House

The fundamental purpose of the Irish in the American Civil War site is to engage people with the history of Irish-America, principally through the stories of those who experienced life around the middle of the nineteenth century. I am always delighted to get opportunities to feature guest posts on the blog, which often provide different perspectives on this history. I was recently approached by Frank Burns with the story of the Irish nanny who served the Confederate White House. Frank kindly agreed to share his research on this Irish emigrant, who for the most part stood on the edge of history. Unfortunately for her and the Davis family, in 1864 she would find herself at centre stage- as tragedy unfolded in the Confederate White House. Frank takes up the story:

During the American Civil War there were two Presidents, and two White Houses. The Executive Mansion chosen by the Confederacy was a white, three-storey house in Richmond, Virginia. Not surprisingly, it became known as the White House. When Jefferson Davis moved into the Richmond White House in August 1861 with his second wife Varina, they had three young children, two boys and a girl. They had already lost their first-born, Samuel, who died before his second birthday. A fourth son would be born later that year.

Amongst the twenty White House staff were at least two Irish immigrants. One was Mrs. Mary O’Melia (née Larkin), a widow from Galway. She was the housekeeper for the young First Lady. How she ended up working in the White House is a sad tale. She had left her children at home in Baltimore to visit Richmond in 1861. But she found herself trapped there by the Civil War. She was engaged by the Davises as housekeeper. In time she became a loyal friend to them, and a confidante of Varina. She would live a long, and by all accounts, successful life. After the war, she was re-united with her children in Baltimore where she operated Boarding Houses. Remarkably, a photo of her has recently been discovered. She died in 1907. (1)

The White House of the Confederacy in 1865 (Library of Congress)

But there is less known about the second Irish woman; she shares the fate of so many of her fellow emigrants, absorbed in her new country and forgotten to her native land. Not even her second name in known. She is simply known as Catherine, the Irish nanny. She worked for the Davises from at least 1862 when Varina temporarily re-located to Raleigh, North Carolina, with the children. Never too popular as a First Lady, this was regarded by some as deserting her husband. Catherine Edmondston, in her diary, is scornful of Varina’s Yankee influences and Northern ways- she even employs a nanny who is white! But by all accounts the Irish nanny was a cherished employee, loved by the family. She slept in the nursery with the children, and clearly formed a close loving bond with them. Doubtlessly, she was proud of her position as nanny to the Presidential family, and although the Civil War raged about her, her life must have been relatively comfortable. But the war and defeat were edging closer and closer. (2)

Then tragedy struck the household. Joseph, the second youngest Davis child had just celebrated his fifth birthday when on April 30th, 1864 he fell to his death from a third floor balcony. Little Joe was regarded as the most beautiful, brightest and best behaved of the children. While playing, he apparently climbed out on the balcony. But mystery surrounds the tragedy. There are discrepancies in reports, as if half-hearted attempts were made to cover up aspects to protect the family. Was he in fact pushed by his older brother, Jeff? It happened when both parents were out of the house; but Varina attempts to give the impression that she was present, presumably to avoid any hints of a neglectful parent (she was in fact a devoted mother). And its not clear how long it took to discover Joe- was medical attention fatally delayed? The parents arrived at the scene just in time to hold their dying son. Catherine was utterly distraught. While brother Jeff prays and tries to revive Joe, she is described as lying prone on the floor next to the body, weeping and wailing ‘as only and Irishwoman can.’ (3)

But there is no avoiding the fact that the tragedy occurred while both parents were out so Catherine was responsible for the children at the time. And Joe should not have been playing on the balcony. It seems Catherine left the employment following the tragedy, but why is unclear. Was she simply unable to continue, blaming herself for the event? Or did she suffer some form of breakdown from sheer anguish and, perhaps, guilt? Or was she dismissed by parents who blamed her for the death of their son?

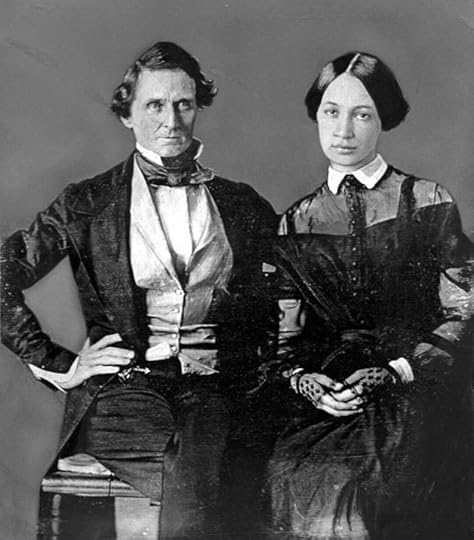

Jefferson and Varina Davis (Wikipedia)

It is not clear what the Davises reaction towards Catherine was. Mary Chesnut, the diarist, was a close friend (‘inseparable’) of Varina’s, and was at hand to console the grieving parents. Her attitude was clear-cut and harsh; she blamed Catherine. She is scornful of Catherine’s ‘Irish howl’ – cheap, she calls it. She goes on to ask; where was Catherine when it all happened? ‘Her place was to have been with the child’ – she then chillingly adds; ‘Whom will they kill next of that devoted household?’ Was Mary Chesnut’s reaction simply reflecting that of Varina? (4)

But there are hints in the Jefferson Davis papers that the Davises remained on good terms with Catherine, and in fact regarded here as one of the loyal friends who stood my them in the horrors that awaited them in defeat. In a letter from prison to his wife, written in September 1865, Davis speaks of Ellen (a ‘mulatto’ maid-servant) and Catherine (and surely this is the Irish nanny!) and their ‘truth and faithfulness.’ He goes on to reflect that not for the first time they fine ‘…our humblest friends, the truest when no longer selfishly prompted.’ There are elsewhere hints that Catherine lived in Baltimore after the war and a tantalising suggestion that she and Mrs. O’Melia remained friends. Perhaps Catherine went to stay with Mrs. O’Melia and maybe even worked for here; it would be nice to think so, but that remains just speculation. (5)

But Catherine is far from forgotten, if you take a tour of the Richmond White House, you won’t see the balcony; Davis had it torn down after the tragedy. But you will see the nursery complete with bed where Catherine slept. And the guide will mention her name and say a few words about her- Catherine, the Irish nanny. And so that will be her memorial.

Postscript. By a strange twist of fate, Lincoln in the other White House would also lose a beloved son during the war. Despite the enmity, both Presidents exchanged heart-felt condolences with each other. The remaining two Davis boys would die young, so the ill-fated Davis’s buried all four of their sons.

Two months after the loss of Joe, Varina gave birth to her final child, Varina Anne, known as Winnie. Catherine and Winnie possibly never met, but Winnie was to go on to write a biography of Robert Emmet, and play a major role in promoting Emmet’s legacy in the U.S. (6)

About Frank: I’m retired with a special interest in the American Civil War. I visit Virginia when I can. I stumbled on the Irish nanny reading Mary Chesnut’s diaries. I knew nothing of the story, but Chesnut’s decrial of the Irish nurse seemed to me unduly harsh- cruel in fact. It stuck in my mind unit I did the White House tour in Richmond. Standing in the little nursery, seeing the bed, imagining the horrors Catherine would have endured so far from home, was a moving experience; heart-breaking in fact.