Damian Shiels's Blog, page 53

May 13, 2013

Some Reflections On Three Years Writing ‘Irish in the American Civil War’

This past weekend marked the third anniversary of the Irish in the American Civil War blog. Sincerest thanks to all of you who have read articles on the site over that time, to those who have taken the time to comment, contribute and share your knowledge, and also to those who have contributed guest posts. Creating and maintaining this site is one of the most enjoyable experiences I have had, and along the way I have been very fortunate in making some great acquaintances both in the U.S. and Ireland.

Many of you will have noted that I have become consumed- to an ever-increasing degree over recent months- by the lives of the ordinary men, women and children impacted by the war. The poignancy of many of their stories, told through documents such as census returns, widow’s pension files, wartime memoirs and newspaper articles is often very difficult to read and can be even harder to write. I normally spend quite a number of hours each week looking at these cases. I find it hard to do this type of research without being deeply affected by it. Somewhere along the way this has developed into an extremely strong feeling of responsibility, bordering on obligation, to tell as many of these people’s stories as I can. Perhaps this has grown out of the fact that their stories have been largely forgotten in Ireland. Interest in their history was ‘left at the port’ when they emigrated. Many are only represented as numbers used to demonstrate the depopulation of this country during the Famine and it’s aftermath, their later lives are thus decoupled from their experiences in Ireland and by extension become almost an irrelevancy in the story of Ireland’s history. This realisation has grown hand-in-hand with a rising despondency about the continuing failure of the Irish Government to take serious steps to acknowledge the effect of the American Civil War on the hundreds of thousands of Irish people in America (and indeed a wider lack of serious recognition of the history of the Irish diaspora worldwide). It would now seem that the sesquicentennial may slip by with no serious efforts to commemorate any of these people in Ireland. I find this is all the more poignant when one considers that many Civil War soldiers took special efforts not to forget the people at home, even when facing the prospect of imminent death themselves.

The blogging world can take you down some unexpected paths. One the completely unexpected outcomes of setting up the blog was the invitation last year from The History Press Ireland to write a book based on some of the stories covered in it. I was delighted to take them up on the offer, particularly as only a few months previously some portions of the site had been plagiarised, one of the risks inherent in putting research up on the internet. The plagiarism in question appeared in a self published book (which you can see here) that contained a number of posts directly lifted from the site. Everyone who starts publishing material on the internet knows that such an occurrence is a possibility, and there is little that can be done about it- however in my view the rewards of blogging more than outweigh the risk. The work in question is no longer available from the major online bookshops, and in the meantime as a result of that History Press offer I have had an opportunity to publish in book form some of this work myself.

My book, titled the Irish in the American Civil War, came out towards the end of February and I am delighted to say it has already sold out. It is currently the subject of a reprint which will be completed by the end of this month. Many thanks to all of you who have already purchased it (I hope you enjoyed it!). It has received excellent coverage on a number of national radio stations (including RTE Radio One, Newstalk and Today FM) and also positive reviews in national newspapers such as The Sunday Times and The Irish Independent. It seems to be having a positive effect on raising the profile of the conflict in Ireland. One drawback is that the book is not as yet available on bookshelves in the United States; we are currently seeking publication options there and hopefully this can be rectified in the coming months.

The site has also brought me the opportunity to present a number of talks about the American Civil War around the country (you can seen an example of one of these presentations here). As anyone who knows me is aware, I love to prattle on about historic topics, none more so than the Irish in the American Civil War. I find that these talks often present opportunities to reach a different audience to those who read the blog. It also provides a forum to champion the case for greater awareness of the conflict and highlight the huge number of people from individual localities who were affected by the war, which in turn can heighten a sense of connection with those who emigrated in the nineteenth century. This is also something a number of colleagues and I (Robert Doyle, James Doherty and Ian Kenneally) are trying to achieve through the Irish American Civil War Trail initiative.

One other major benefit this site has bestowed on me is an increased knowledge of social media, its applications and its potential. When I sat down at my computer three years ago I had only the vaguest idea of what a blog was. The intervening years have taught me to fully embrace the potential of the internet and social media as an educational tool; it is undoubtedly the most powerful form of mass communication available to us today. I have been able to bring the lessons learned at Irish in the American Civil War to other blog sites I have set up that focus on heritage businesses and community heritage projects (by the way if you are interested in any of them, they are the Rubicon Heritage Blog, Bere Island Heritage Project, Midleton Archaeology & Heritage Project and the Know Thy Place Blog).

Perhaps the most significant lesson of all though is a simple one. I have discovered that I love the writing style that blogging engenders. Blogging can be all things to all people. There are no rules as to how you write, or to how many, or indeed few, writing conventions you choose to adhere to. Having written many papers in refereed and academic publications over the years (and such publications have their value and their place), I have found in blogging an opportunity to try to write in an engaging style for a general audience while still trying to be rigorous in the use of referencing. It is perhaps not the most usual of blogging styles (and can certainly be a bit time-consuming), but I hope it allows the site to stand up more as an educational resource. Blogging also allows you to mix and match; thus I try to combine the personal story aspect of the site with a strong resource component for those interested in the Irish in the American Civil War, with pages providing more detailed information on aspects such as Books, the Medal of Honor, Generals and Regimental Nativity.

Over the past three years this site has been a central part of my life, and I imagine and hope that it (and the Irish experience of the American Civil War in general) will remain so for many years to come. If it were possible I would quite happily spend all of my time researching and telling the stories of the Irish in nineteenth century America, but alas I have to be contented with a few hours at evenings and weekends. For those of you who read this blog, thanks for coming along on the journey so far, and for helping to make it so much fun!

Filed under: Discussion and Debate, Irish in the American Civil War Tagged: Book Review, History Blogging, History Press, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Irish Memory, Social Media

May 11, 2013

The Personal Story of Bernard Quinn: Irish Emigrant, U.S. Soldier

The sheer scale of the American Civil War makes it often impossible to comprehend. The great armies, grand charges and huge casualty figures that typify the conflict make it difficult for us to bridge the gap of time and experience that separates us from those who were there in the 1860s. Narrowing our view to look at the stories of individuals and small groups is one way of getting us closer to understanding the reality of war. It is much easier for us to grasp the impact of momentous events on a single person or family, as it allows us to relate directly to human experience.

I am fascinated by the individual story. They are at once emotive and powerful, and can serve to illustrate wider truths regarding the impact of conflict. They also demonstrate that the American Civil War continued to affect people well beyond 1865. We often forget that the stories of those who survived the conflagration did not end at Appomattox or Bennett Place. We would like to think that the people who had endured four years of war had experienced the worst that life had to throw at them. The reality for some was that the decades after 1865 did not bring the reward and respite they may have deserved. Such was certainly the experience for Bernard Quinn.

Bernard Quinn was born in Co. Monaghan around the year 1835. It is not clear when he emigrated to the United States, but he may be the Bernard Quinn who sailed from Liverpool aboard the Lucy Thompson, anchoring in New York on 26th May 1857. Either before he left Ireland or after his arrival in America Bernard worked as a baker, but he soon decided on a career change. On 12th September 1857 the young man approached Lieutenant Updegraff of the U.S. Army and decided to enlist for a five-year term. Perhaps he wanted financial security or sought adventure- perhaps both; either way his decision began what would be a long association with the military. (1)

Bernard was described in 1857 as 5 feet 8 inches in height, with blue eyes, sandy coloured hair and a fair complexion. He became part of Company H of the 4th United States Infantry, a regiment with a strong Irish contingent. In the years before the outbreak of the Civil War the 4th saw service on San Juan Island and on the west coast. With the coming of hostilities in 1861 they returned to the east, becoming part of Sykes division of regulars in the Army of the Potomac. Their first actions of the war were on the Peninsula, and they played a notable role in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. Bernard served with the regulars up until September of 1862, when his term of enlistment expired on 12th September. The five-year veteran left the ranks just prior to the Battle of Antietam. (2)

The Battle of Gaines’ Mill, 1862, where Bernard Quinn and other U.S. Regulars Excelled (Alfred Waud, Library of Congress)

The Monaghan man did not take long to get back into the fray. On 23rd September 1862, only days after his discharge, Bernard enlisted as a Corporal in the largely Irish 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry. He remained with them for the duration of the war, serving with the Army of the Potomac and in the Valley Campaign before joining up with Sherman for the conflict’s conclusion in North Carolina. He mustered out with his comrades in Philadelphia on 14th July 1865. (3)

For the next ten or so months Bernard tried civilian life in Philadelphia- it may be that he returned to his previous profession as a baker. However, it wasn’t long before he decided on another stint in the military. He was still only 30 years of age when on 18th May 1866 he enlisted again, this time for three years. Although his profession was once more recorded as ‘baker’, in reality by now Bernard Quinn was a soldier through and through. Having already tried the infantry and cavalry, this time he had joined the 1st United States Artillery. The unit spent the majority of the late 1860s on garrison duty, and Bernard eventually rose to the rank of Sergeant. His final term in the military ended on 18th May 1869, when Bernard was discharged and walked out the gates of Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island and into permanent civilian life. (4)

During his time in the military Bernard Quinn had been associated with three branches of the service- infantry, cavalry and artillery. He also chose variety in the cities he lived in; having initially arrived in New York, he had spent time in Philadelphia and eventually decided that his future lay in New Bedford, Massachusetts. It seems probable that he had problems readjusting to civilian life, and that things were never quite the same for Bernard after 1869. The decades passed with little word of Bernard Quinn. However he re-emerges in 1905, when a newspaper article charts the tragedy of the veteran’s final years:

PENSION CAME TOO LATE

Old Ragman Was Drowned When About to Receive It.

New Bedford, Mass., November 5. – One the eve of receiving a fortune that would make him independent for the remainder of his life, Bernard Quinn, 71 years old, was drowned in the Acushnet River. His body was found floating near a wharf by fishermen.

For 15 years the man had been a familiar sight about the streets, and his only visible wealth was two ragbags which were generally filled with assorted rags. The man was to come into possession of a back pension estimated to be at least $5,000 within a few days.

Quinn, who was known in this city as “Old Barney,” was born in Ireland, and enlisted in the Army after coming to this country. He served in Company H, Fourth Infantry, and also in Company K, Thirteenth Pennsylvania Volunteers.

After the Civil War he served a third enlistment in the regular Army, holding the rank of corporal and sergeant. While in this city the old man made his headquarters at the City Mission, and was always in destitute circumstances.

A short time ago Congressman William S. Greene was interested in the man, and through his influence the first payment on a back pension, amounting to thousands of dollars, was to have been paid. (5)

So ended the sad story of Bernard Quinn. His life was far more than simply a record of service between 1861 and 1865, though it seems his years in the military may well have been among his happiest. The image of a young, heroic member of Sykes Regulars at Gaines’ Mill in 1862 contrasts sharply with the destitute ragman floating in the Acushnet River four decades later. But this was the same man, the emigrant baker turned soldier, who ended his days as a ragman. When we look at those who lived through the Civil War we should try to examine their entire life experiences, not just the heady days of their youth on the battlefield. Such poignant stories make it all the more tragic that Ireland does not today do more to remember those born on this island who experienced the American Civil War. The story of Bernard Quinn from Co. Monaghan is just one of hundreds of thousands written by Irish emigrants in the United States. The creation of the Irish diaspora and Irish emigration is a major part of Ireland’s history. We should spend more time exploring them, discussing them, learning from them and remembering them.

(1) New York Passenger Lists, U.S. Army Enlistments; (2) U.S. Army Enlistments; (3) Bates 1870: 1300; (4) U.S. Army Enlistments; (5) Baltimore American;

References & Further Reading

Baltimore American 6th November 1905. Pension Came Too Late Old Ragman Was Drowned When About to Receive It

Bates, Samuel Penniman 1870. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers 1861-5 Volume 3

New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

U.S. Army Register of Enlistments 1798-1914

Civil War Trust Battle of Gaines’ Mill Page

Filed under: 13th Pennsylvania, Monaghan Tagged: 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, 1st US Artillery, 4th US Infantry, Acushnet River, Battle of Gaines' Mill, Emigration, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora

May 10, 2013

Can You Help Find Medal of Honor Recipient Martin McHugh’s Descendants?

A previous post on the site looked at the efforts in 2012 to honour Seaman Martin McHugh in Danville, Illinois. A Medal of Honor recipient for his actions aboard the USS Cincinnati at Vicksburg on 27th May 1863, Martin had lain in an unmarked grave for over 100 years. Machelle Long played a central role in having Martin remembered and has kindly written a guest post on her ongoing work on the Galwegian. She is now seeking assistance from readers of the site in an effort to track down a living relative of Martin.

The grave of Medal of Honor recipient Martin McHugh in Danville, Illinois (Photo: Machelle Long)

As time draws near the 150th anniversary of the brave action for which Irish-born Martin McHugh was awarded the U.S. Medal of Honor during the Civil War, I would like to thank Damian Shiels for inviting me to do this guest post.

I was honored to work with a great group of extremely knowledgeable researchers and historians in the research of Seaman Martin McHugh following initiation of the research in 2010 by the United States Medal of Honor Historical Society. Our research group and the Historical Society were intent on a common goal of preserving the honor of this brave man who, with his wife Catherine, lay in an unmarked grave in Danville, Illinois for 105 years. On April 21, 2012, that unfortunate situation was rectified with a ceremony honoring Seaman McHugh. The highlight of the ceremony was the unveiling of his newly set U.S. government issued Medal of Honor grave marker which also marks the grave of his wife, Catherine.

The grave of Catherine McCue, Danville, Illinois (Photo: Machelle Long)

Seaman McHugh was born in 1837 in County Galway, Ireland. He immigrated to the United States in the early part of the 1850s. His mother (Bridget McHugh) and three sisters (Bridget, Sarah, and Catherine) immigrated at approximately the same time although we have not been able to determine the exact time of his arrival in the United States or if he and all of his family members arrived together or at various times.

Seaman McHugh came to Danville, Illinois as early as 1856 where he worked as a laborer before enlisting in the United States Navy in October of 1862. The climax of his Civil War service was during an engagement with the Vicksburg batteries when, after heavy Confederate fire, the ship on which he was serving sank. Seaman McHugh and four of his shipmates were awarded the Medal of Honor by President Abraham Lincoln on July 17, 1863 for their brave actions during that engagement. Those actions included saving the lives of shipmates and the ship captain who could not swim.

He served in the Navy until June of 1865 when he returned to Danville, Illinois and began a career working in the coal mines which spanned nearly three decades. In October of 1865, he married Catherine Griffin and subsequently had five children. One child died in infancy, however he and Catherine raised four daughters, Mary (b.1866), twin daughters Katherine and Margaret (b.1869), and Sarah (b.1871). Mary later married Ed Rabbeson and eventually moved to Chicago and then on to the state of New York, Margaret (who was also known as Maggie) married Daniel Beam and settled in Bloomington, McLean County, Illinois, and Sarah (who was also known as Sallie) was first married to Walter McElhaney then to Perg Smith and remained in Danville, Illinois. Katherine (who was often called Kate) never married and returned to Danville, Illinois after her father’s death to care for her mother. In the 1940s, she was shown living in Peoria, Illinois. There were known children born to Maggie and Sallie however no further generations could be traced.

Martin McHugh Information Board in Danville, Illinois (Photo: Machelle Long)

Seaman McHugh died at the National Soldier’s Home in Danville, Illinois on February 23, 1905. His funeral was held at St. Patrick’s Church in Danville (of which his sister Bridget and her husband John Flaherty were a founding family) and he was interred at St. Patrick’s Cemetery, now known as Resurrection Cemetery. Martin’s wife Catherine continued to live in Danville, Illinois until her death in December of 1910.

Our final goal and a hope that we have kept alive throughout the research of Seaman McHugh is to locate a living blood relative of Seaman Martin McHugh. Damian has been kind enough to allow me to reach out to his readers through this post in hopes that we might accomplish this. After more than a century of being forgotten, his honor and memory are now kept alive locally with speeches, remembrances, and memorial services. We think it fitting that his honor be shared with his family and we look forward to hearing from anyone who may have information on a family connection to Seaman McHugh.

If you have information that you feel may be of interest to Machelle in her efforts, please leave a comment on this post or email the site directly at irishamericancivilwar@gmail.com.

Filed under: Guest Post, Medal of Honor Tagged: Co. Galway, Danville, Illinois, Irish American Civil War, Martin McHugh, Medal of Honor, USS Cincinnati, Vicksburg

May 6, 2013

A Soldier’s Thoughts turn to Ireland- Petersburg, Virginia, 1864

In 1864 James McDonnell was a 27-year old Irishman serving in the 5th New Hampshire Infantry. His unit would end the war with the dubious distinction of having suffered more battle fatalities than any other Union regiment. James had not been an early volunteer- financially motivated, he enlisted as a draft substitute on 1st October 1863 in Keene, New Hampshire. By September 1864, having endured the Overland Campaign, James found himself part of the forces surrounding Petersburg. His thoughts turned to Ireland, his inability to get paid, and his hopes for a Democratic election victory. (1)

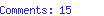

An unidentified soldier of the 5th New Hampshire Infantry (Library of Congress)

Fifth New Hampshire Volunteers

Camp Near Petersburg, Sept. 10th, 1864

To the Editors of the Irish-American:

Gentlemen- Herein you will find inclosed $1.25c. as my subscription for a half year to your paper. It may seem strange to some to see a soldier, whose every moment may be his last, thus contributing for a newspaper as independently as if he possessed a lease of his life; but, gentlemen, I view the matter in a different light; I like to “take time by the forelock,” and while I am alive secure for myself that which I may need shall it be God’s will I should be spared longer; and I know of nothing of which my mind stands more in need while I do live than that paper which furnishes me with news from poor old Ireland- from the land of my birth. Alas! checkered, indeed, has been, and still is, her fate, and it looks almost a mockery to hope for her; but still it may not, with God’s help, be too much for one of her exiles in his sorrow to pray in the fulness of his heart that the dawn of a new era is not far distant, and that he may yet have an opportunity of treading his native hills, free as the sunshine of Heaven which plays upon them, or die struggling to emancipate every blade of grass in his bleeding country to which the tyrant lays claim.

This remittance is not government money; and, I presume, the money which they now hesitate to pay the troops in the field will be turned to good account to pay the expenses of the Fall campaign or hire new recruits in Spring. They give us plenty of time to get slaughtered before they pay us; and if such be the motive, what swindlers they must be. Now, is it right to leave men here six months or more without pay? What right have they to control our money? They make us fulfil, and more than fulfil, our contract with them, and it is, to say the least, and use the mildest term, an injustice to treat us so. Correspondents may tell you the troops are satisfied. I say they are not, and no correspondent knows as well as a private soldier.

The nomination of McClellan is hailed by almost every soldier as the day-star of a glorious peace and prosperity for America; and his election would be in no danger if the votes of the troops could decide it. His name is never out of their mouths, and they trust to the people of the North to unite now and show that no sectional partizan or partizans can lead them on to slaughter and the country to destruction.

I have the honor to remain, gentlemen, your very humble servant,

James McDonnell, Co. B, Fith [sic.] N.H. Vols., 1st Brigade, 1 Division, 2d A.C.

James survived the remainder of the war, and was discharged from service on 2nd June 1865 in Washington D.C. (2)

(1) New York Irish-American, Child 1893: 123; (2) Ibid.

References

New York Irish-American 24th September 1864. Fifth New Hampshire Volunteers

Child, William 1893. A History of the Fifth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers in the American Civil War.

Filed under: Battle of Petersburg Tagged: 5th New Hampshire, Draft Substitute, George McClellan, Irish American Civil War, Irish Emigrant, New York Irish-American, Overland Campaign, Petersburg

May 3, 2013

Medal of Honor: Private Felix Brannigan, 74th New York Infantry

Felix Brannigan was one of a number of Irishmen who were awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Chancellorsville. The circumstances behind Brannigan’s award are surely among the more unusual. A comrade would later claim that one of the reason’s Brannigan received the honour was that he was one of two Yankees actually present when Confederate General Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded, struck by friendly fire on the night of 2nd May, 1863.

Felix Brannigan is a hard man to locate prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Born in Ireland in 1844, it is not known what county he was from or when he emigrated to the United States. A ‘Felix Branagan’ was naturalised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1856 but it is unclear if this is the same individual. Felix was an early volunteer in 1861, enlisting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on 22nd April 1861. Unusually his company became part of a New York regiment, the 74th Infantry, one of the units of the famed Excelsior Brigade. (1)

Felix appears to have been a natural leader of men. He mustered in as a Corporal of Company A in July 1861 before becoming First Sergeant in Company K on 14th June 1862. However an indiscretion led to him being returned to the rank of Private, and back to Company A, on 1st October that year. It was here that he found himself when the Battle of Chancellorsville erupted in May 1863. (2)

The 2nd May had seen Stonewall Jackson launch a ferocious attack against the Army of the Potomac’s right flank, which consisted of the Eleventh Corps. Achieving complete surprise, the Rebels swept all before them. As the day drew to a close it fell to other units of the Northern army, including the Excelsior Brigade of the Third Corps, to hold the line. Private Felix Brannigan and his comrades formed part of Major-General Hiram Berry’s Division, and as night fell they were in position to the north of the Orange Plank Road, facing towards the west, and Stonewall Jackson’s victorious Confederates. (3)

Everyone expected the battle to resume with unrelenting fury on the morning of 3rd May. In the darkness of night the men heard firing to their front, and wondered if some of the Eleventh Corps may still be ahead of them. The confused fighting of the day meant that no-one was sure of exactly what they faced. Captain F.E. Tyler of the 74th New York was with his men when Brigadier-General Joseph Revere, who commanded the Excelsior Brigade, rode up. Tyler remembered their conversation:

‘He then told it me it was of the utmost importance to know what was in front, and ordered me to pick out some trusty men and send them out to get the best information they could. I went to my old company (A), and called for Felix Brannigan, who had been with me all during the war, and whom I knew from long experience to be a cool, courageous, intelligent soldier. I told him what I wanted, gave him my ideas as to how to get out of the lines and what to do, and suggested the other men who he should take along.’ (4)

The four men in the scouting group, all of whom volunteered for the mission, were Sergeant-Major Eugene P. Jacobson, Private Joseph Gion, Private Gotlieb Luty and Private Felix Brannigan. They decided to split into two groups of two to increase their chances of success. Slipping out of the lines, the men set off through their own pickets and into the thickets and swamps where they had to negotiate enemy pickets before hoping to find out what was in front of them. Felix Brannigan and Gotlieb Luty went together. Luty described what happened next:

‘We had advanced about fifty yards beyond the outposts, and were close to the plank road, when we heard horses coming down. We concluded to hide and await developments. A party of horsemen rode to within fifteen yards of us and we discovered by listening to their conversation that it was a body of rebels. Suddenly the firing commenced from all sides at once. There was only one round, and just as the firing ceased, we heard them say that ‘the General’ was shot. The reconnoitering party consisted of General Jackson and his staff.’ (5)

Stonewall Jackson lies mortally wounded. Was Irishman Felix Brannigan present when the famous General was hit? (Currier & Ives)

Luty was admittedly writing after the war, but if his testimony is to be believed than he and Felix Brannigan were present when Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded by his own troops. The two men appeared to have tried to get back to their own lines at this point, but confused by the woods and darkness actually pressed on in the wrong direction. They came upon a large body of enemy troops which they realised were Jackson’s men, who appeared to be in a position to launch an attack against their line at first light. The Yankees successfully retraced their steps back to their own lines, all the while hearing occasional crashes of musketry as nervous soldiers fired at every perceived danger. All four men had returned by daylight, armed with valuable information as to the enemy’s intentions. (6)

The reconnaissance the men had undertaken had ultimately been ordered by Major-General Berry, the men’s divisional commander. When the expected Rebel attack was about to get underway shortly after 7am on 3rd May, Berry was at the front having just delivered orders to one of his brigades. When he moved to return to his headquarters he was struck by a sharpshooter and wounded. He knew it to be mortal, informing his staff: ‘I am dying, carry me to the rear.’ Berry died that morning at the Chancellor House. It was reported that one of his last instructions was that the four men who had reconnoitered the enemy positions the night before be rewarded for their services. (7)

So it was that Private Felix Brannigan and his three comrades received the Medal of Honor. Brannigan’s award was issued on the 29th June 1866. The citation read: ‘Volunteered on a dangerous mission and brought in valuable information.’ The remainder of the war saw Brannigan’s continued rise. He transferred to the 40th New York in August 1864 but soon decided to take the opportunity to become and officer. In December that year he accepted the position of Second Lieutenant with the 32nd United States Colored Troops, and ended the war as First Lieutenant and Adjutant of the 103rd United States Colored Troops, a position he took up in April 1865. (8)

After the war Felix became an attorney and in the 1870s was practicing in Mississippi; he was living in Jackson in 1875. On 4th January 1877 he married Sarah P. Pegram, with whom he had a daughter. Felix Brannigan died on 10th June 1907 of disease of the kidneys. Unfortunately he did not have a significant estate and could afford only limited life insurance, and so his death left his wife destitute. Efforts were made to secure her an increased pension based on her husband’s wartime service, as by this stage in her life she suffered from impaired sight and was unable to work to support herself and her daughter. Sarah followed her husband to the grave in 1913. Their trials in later life behind them, Felix and Sarah today rest together in Section 3, Grave 1642 of Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia. (9)

(1) Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, NY Adjutant General Report; (2) NY Adjutant General Report; (3) Sears 1996: 314; (4) Rodenbough 1893: 29; (5) Beyer & Keydel 1901: 148; (6) Ibid.; (7) Sears 1996: 323; (8) Proft 2002: 807, Felix Brannigan Pension Index Cards; (9) Adjutant-General Letters, Pensions and Increases of Pensions 1908: 17, Find A Grave;

References & Further Reading

Beyer, Walter F. & Keydel, Oscar F. 1901. Deeds of Valor: How America’s Heroes Won The Medal of Honor, Volume 1

Proft, R.J. (ed.), 2002. United States of America’s Congressional Medal of Honor Recipients and their Official Citations, Fourth Edition

Rodenbough, Theophilis F. 1893. Fighting For Honor: A Record of Heroism

Sears, Stephen W. 1996. Chancellorsville

Committee on Pensions 1908. Pensions and Increases of Pensions for Certain Soldiers and Sailors of Civil War, etc. February 24, 1908

Felix Brannigan Pension Index Cards

New York Adjutant General Report Rosters for 40th New York Infantry and 74th New York Infantry

NARA M666. Roll 0241, File 6580. Unbound letters, with their enclosures, received by the Adjutant General, 1871-1880

Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Felix Brannigan Find A Grave Memorial

Civil War Trust Battle of Chancellorsville Page

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

Filed under: Battle of Chancellorsville, Medal of Honor Tagged: Battle of Chancellorsville, Excelsior Brigade, Felix Brannigan, Gotlieb Luty, Irish American Civil War, Medal of Honor, Stonewall Jackson, United States Colored Troops

May 2, 2013

150 Years Ago: The Human Cost of Chancellorsville for two Irish Women

On 2nd May 1863, 150 years ago, hordes of Confederate troops appeared as if from nowhere and descended on the unsuspecting Yankees of the Eleventh Corps in the Virginia Wilderness. The blow Stonewall Jackson’s Rebels delivered to the Federal flank during the Battle of Chancellorsville is remembered as one of the most famous and brilliant actions of the war. But the reality of the grand havoc of battle is very different for those individuals affected by it. For Susan Gallagher and Mary O’Neill, the 2nd May 1863 became memorable for all the wrong reasons.

The Battle of Chancellorsville (Kurz and Allison)

The 31st January 1852 had been a happy day in the village of Knocklong, in the east of Co. Limerick. That was the day local priest Father McGrath presided over the wedding of Maria Heaphy and Richard O’Neill. Maria’s relative Thomas Heaphy and Joanna Connery acted as the couple’s witnesses. The two had not wed in the first flush of youth- Richard was around 30 years of age at the time- and they perhaps seemed unlikely candidates to strike out for a new life in America. However, sometime after 1852 Richard and Mary (as everyone called Maria) decided to move to New York, where they settled in the city of Schenectady. By the time war broke out the O’Neills had no children (or at least none who survived). Richard, now 40 years old, decided to enlist in the 154th New York Infantry, mustering into Company F of the regiment on 25th September 1862. (1)

The marriage of James and Susan Gallagher had also taken place in Ireland, but it had occurred long before Richard and Mary’s ceremony, and at the other end of the country. They were from Co. Derry, and had been married there on 10th May 1834 by the Reverend McLoughlin. Like the O’Neill’s they were in their thirties when they decided to tie the knot. James had been born around 1798 and Susan around 1803, so by the time they emigrated to New York they had already spent many years in Ireland. When the American Civil War arrived the couple were getting on in years, and James in particular began to physically struggle. Sometime around 1860 he was no longer able to properly provide for his family. By April of 1861 the family physician, Felix O’Neill, realised that old age and rheumatism would keep the Derry native permanently out of the workforce. It now fell on the couple’s young bachelor son, Edward, to support his parents. He turned 18 in 1862, and decided that the best way to offer regular financial support for his parents was to enlist. He mustered into Company A of the 119th New York Infantry on 4th September 1862. (2)

Given the circumstances of both Richard O’Neill and Edward Gallagher, it would seem that financial security was a major factor in determining their enlistment. Indeed by May 1863 Edward had already sent $75 home to his mother on 38th Street, between 1st and 2nd Avenues in New York. This enabled her to pay the rent and buy necessaries for herself and her husband. Certainly neither of the men would have been expecting the chaotic scenes they witnessed on 2nd May 1863. Both suddenly found themselves in the midst of a cauldron of death, as Jackson’s imperious Rebels barreled into the positions of the unsuspecting men of the Eleventh Corps. (3)

Caught utterly unawares by the surprise Confederate attack, line after line of Eleventh Corps defenders were turned and routed in turn. Private Edward Gallagher and his comrades in the largely German 119th New York took up position on the Orange Plank Road to try to stem the Rebel tide. Their attempts proved futile. Nine of the twelve men in the regiment’s Color Guard were shot down, and their Colonel, Elias Peissner, killed. The line eventually collapsed and the survivors joined the rout. Edward was one of the men who got away, but he was not one of the unscathed- during the fighting he had taken a bullet in his right arm. (4)

Private Richard O’Neill and the men of the 154th New York went into action soon afterwards. In one of the last lines of defence to be organised, they formed part of a line of some 4,000 men who hoped to stem the Rebel tide in the vicinity of Dowdall’s Tavern. The victorious Confederates emerged into a wall of Federal fire. O’Neill and his comrades ‘would mow a road through them every time but they would close up with a yell…’ but once again the Rebels were able to flank the Yankee line. Having sustained 40% casualties, the 154th New York joined the retreat. Richard O’Neill was not among the lucky few. The Limerick man had been shot in the head, and lay seriously injured on the field. (5)

Neither Edward Gallagher or Richard O’Neill died on the battlefield of Chancellorsville. Edward’s right arm could not be saved, and he suffered amputation. He was sent to the Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, where he died from his wounds on 20th June 1863. By that date Richard O’Neill was already dead. Like Edward he lingered for a long time after the end of the battle; he passed away at Brooks Station, Virginia on 22nd May. (6)

The death of men like Richard O’Neill and Edward Gallagher are the real face of grand strategic strokes such as Jackson’s brilliant attack at Chancellorsville. Their long, lingering death was only the beginning of the suffering for Susan and Mary. Left with no means of support for her and her husband, the elderly Susan Gallagher was left to rely on charity for succour until she was assisted in 1865 by the U.S. Sanitary Commission who helped her secure a pension for herself and her husband in their twilight years. Richard’s death left Mary O’Neill on her own. The final entry in her pension file dates from 23rd November 1885. She hadn’t been heard from since 1883, with her last known address being 35 Hill Street, in Troy, New York. The postmaster was asked to inform the Department of the Interior of her whereabouts. His reply regarding the Limerick woman’s demise was brief:

‘Am unable to find the exact date of death of Mary O’Neill but am informed it was about two and one half years ago.’ (7)

(1) Richard O’Neill Widow’s Pension, NY Adjutant General; (2) Edward Gallagher Widow’s Pension, NY Adjutant General; (3) Ibid. (4) Sears 1996: 276-77, Edward Gallagher Widow’s Pension; (5) Sears 1996: 280, Richard O’Neill Widow’s Pension; (6) Edward Gallagher Widow’s Pension, Richard O’Neill Widow’s Pension; (7)Richard O’Neill Widow’s Pension;

References & Further Reading

Richard O’Neill’s Widow’s Pension File WC36780

Edward Gallagher’s Widow’s Pension File WC87365

Sears, Stephen W. 1996. Chancellorsville

Annual Reports of the Adjutant General for the State of New York

Civil War Trust Battle of Chancellorsville Page

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

Filed under: Battle of Chancellorsville, Derry, Limerick Tagged: 154th New York, Battle of Chancellorsville, Derry, Irish American Civil War, Limerick, Sesquicentennial, Stonewall Jackson, Widows Pension

April 29, 2013

‘Information Wanted’: The Irish Missing and Disappeared of the Civil War

Newspapers that appealed to emigrant populations like the New York Irish-American often ran ‘Information Wanted’ sections, where people could place classified ads. Many are attempts to locate long-lost family, friends or beneficiaries of wills. These advertisements ran for three issues at the cost of $1. Some provide a window into the affect the war had on many families both before and after the conflict- literally ripping them apart. Here are a number of examples.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, April 19, 1862

Information Wanted, Of Patrick McCue, a native of Killrain, parish of Innishkeel or Glenties, county Donegal, Ireland. He is twenty years old, and will be in this country three years next May. He went to peddle with a man of the name of Neal Keeney. When last heard from he was in Missouri, with a farmer by the name of O’Donnell, from the county Donegal; heard since that he enlisted in the Union Army in Missouri. Any information of him, dead or alive, will be thankfully received by his mother, Rose McCue, 126 Mott street, New York. Missouri papers, please copy.

A Patrick McCue is recorded as serving in the 11th Missouri Infantry and the Missouri Marine Brigade. He survived the conflict, passing away in Bismarck, North Dakota on 13th December 1924.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, April 19, 1862

Information Wanted, Of a soldier named John Dunn, son of Mary Dunn, formerly of Clonduff, Queen’s County, Ireland. When last heard from, November 1856, he was in the 6th Regiment of Infantry, U.S.A. Co. H, Captain Henderson, Newport Barracks, Kentucky. Any information concerning him will be thankfully received by his mother, Address Mrs. Mary Dunn, Mecklenberg, Schuyler county, New York.

A John P. Dunn is recorded in the 6th U.S. Infantry as a Sergeant. He died on 10th September 1917 in Bismarck, North Dakota.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, August 2, 1862

Information Wanted, Of Master Walter Dignan, son of Walter Dignan, leader of the Manchester Cornet Band, now with Fourth Regt., N.H.V., stationed at St. Augustine, Fla. He left his home, at Manchester, N.H., Friday, June 6; is 14 years old, light complexion, light brown hair, dark hazel eyes: rather tall and slim of his age. Was dressed when he left in a spencer of drab cloth with a black velvet collar, dark trowsers, small blue and black check, blue cap, Congress boots. Appears when in conversation rather shy and diffident. Any information of him will be gladly received his mother, Eliza Dignan, Laurel St., Manchester, N.H.

Walter survived the war and would later receive a pension for his services in the 4th New Hampshire Infantry.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, August 2, 1862

Information Wanted, Of John Scannel, a native of the parish of Carrigaline, county Cork, Ireland, who left there about twenty years ago. When last heard from he was in Cape Cod, State of Massachusetts; he is now supposed to be in the United States service, in the 9th Massachusetts Regiment. Any information of him will be thankfully received by his brother, Thomas Scannel, Wapella, De Witt county, State of Illinois.

John Scannel, from Carrigaline had been a 26-year-old married shoemaker when he enlisted in 1861. He lived in North Bridgewater. His brother Thomas had not heard from him because John had died of wounds on 1st July 1862, from wounds received at the Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, April 2, 1870

Information Wanted, Of Allen McKenna, of Company L, Seventh New York Heavy Artillery, who was wounded at the Battle of Coal [sic.] Harbour. Any person who can prove the same will be handsomely rewarded by giving information at this office, or by writing to James H. Driscol, Toms River, N.J.

It is not known why James Driscol wanted to get in touch with Allen. Perhaps they had been pre-war friends or one-time comrades. If he ever did receive the relevant information, it would have told him that Allen McKenna had died on 12th June 1864 of the wounds he received at the Battle of Cold Harbor.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, April 2, 1870

Information Wanted, Of Alexander Scarff, a native of Dublin, Ireland, who sailed from Liverpool in the ship Great Western, under the name of Arthur Shaw; arrived at Castle Garden on 5th November 1862; was then 19 years of age; has not since been heard of by his friends or parents; is supposed to have joined the U.S. Army. Any information of him will be thankfully received by his aunt, Mrs. J.D. Clinton, Bath-North, Greenbush, Rensselaer County, N.Y.

No Alexander Scarff appears in Union service, but an Arthur Shaw does, serving with the 174th New York Infantry. The details suggest he was in fact Alexander. He enlisted aged 19 on 6th November 1862 (the day after Alexander had arrived in New York). He mustered in as a Private in Company B on 13th November 1862 for three years. The reason he had not been heard from in seven years is that he had been killed in action on 13th July, 1863 at the Battle of Ascension. It is unknown if his parents at home in Ireland ever learned of his fate.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, December 25, 1875

Information Wanted, Any person who can certify to the death of Edward Sweeny, who was killed in the second battle of Bull Run, will please communicate with James Sweeny, Hunter’s Point, P.O., N.Y.

James was clearly looking for confirmation of Edward’s death, 13 years after it occurred.

New York Irish-American, Saturday, December 25, 1875

Information Wanted, Of Daniel Sullivan, a former inmate of the Soldier’s Home, Washington D.C., who left that place about March 1st, 1875, and when last heard from was living under the care of the Sisters of Charity connected with St. Patrick’s Church, New York city. Any information of him will be thankfully received by John P. McCloskey, P.O. Box 211, Washington D.C.

Daniel Sullivan was presumably a veteran of the war, who had fallen on hard times. There were a large number of Daniel Sullivan’s in the homes, as yet he has bot been firmly identified.

These are just a handful of the classified ads brought out both during the war and in the years that followed. They offer a glimpse of the real cost of war. It illustrates that even where men survived unscathed, families were often separated or estranged for long periods. Mothers such as Eliza Dignan desperately sought news of their sons- presumably some like Walter had run away to enlist. Others spent years trying to find out the ultimate fate of friends or family who had been killed or wounded. Some, like the parents of Alexander Scarff, were still searching for news of their loved one’s fate in the 1870s, no doubt still clinging to hopes that their son was alive and might return to them one day in Dublin.

References

New York Irish-American

New York Regimental Rosters

Union Pension Index Cards and Muster Rolls

Filed under: Irish in the American Civil War Tagged: Battle of Malvern Hill, Disappeared, Irish American, Irish American Civil War, Missing in Action, Missouri, New York, North Dakota

April 20, 2013

A Regimental Child and the Baby Name Civil War

As newly formed regiments left their home states for the seat of war, many wives chose to accompany their men to the front. When the 37th New York ‘Irish Rifles’ settled into their duties around Washington in the summer of 1861, Private John Dooley had his family with him. Waiting in camp was his wife and the unborn child she was carrying. The regiment would soon celebrate the birth of a son, who was given a name that would serve as a reminder of the great conflict.

Although perhaps not an especially frequent occurrence during the American Civil War, the birth of children to camp follower’s had been commonplace in armies such as those the Britain and France in the 18th and 19th centuries. The children were described as ‘born to the regiment’ (‘né au régiment’ in French) and they often went on to serve in the formations into which they were born. In the majority of cases the fathers of these children were professional soldiers, who could expect to spend much of their lives on campaign or fulfilling garrison duties in far-flung parts of the world. John Dooley ‘s case was somewhat different. As a citizen soldier who had recently volunteered, he and his wife made a conscious decision for her to follow him to the front.

John Dooley formed part of Company K, which had been raised around Pulaski, New York. The 24 year-old had enlisted on 25th May 1861 and been mustered in on 7th June, when his wife was already a number of months pregnant. It is not clear if Dooley’s wife left New York with the regiment in late June 1861 or if she joined up with John in camp later. Clearly they felt that they should stay together- perhaps it was a matter of financial necessity, or a wish not to be separated. Whatever the reasons, the occasion of the birth that September was a special occasion and as such was reported to the New York Irish-American:

THE CHILD OF THE REGIMENT

A few nights ago, we had a birth in the 37th, the wife of Private Dooley, of Co. K, bringing him an heir, which the officers forthwith adopted as their protégé, to be the future “child of the regiment”. He was baptised on Sunday, the 15th, by Father Tissot, Col. Burke and Mrs. Lieutenant Barry standing sponsors in behalf of the regiment. As soon as pay-day comes, it is proposed to contribute a handsome sum, which is to be deposited in bank there to accumulate to the credit of the child when he comes of age. Already has been received several presents of clothing, &c., from kind ladies in Washington and the President is expected to contribute his mite, also, towards his namesake, Abraham Lincoln Dooley. (1)

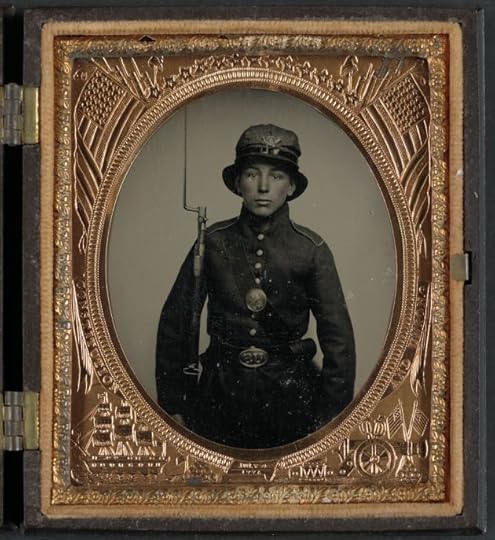

Baby names was perhaps one of the more unlikely arenas where Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis fought it out (New York Historical Society)

Luckily for the family John survived the war and mustered out with the 37th New York in June 1863. He claimed a pension from 1881 and following his death a widow’s pension was paid out to his wife. The family have otherwise proven elusive , and I have as yet found no further details of their post-war life. (2)

The enthusiastic naming of the Dooley’s boy as ‘Abraham Lincoln’ raises the question as to just how common it was during the feverish days of 1861 to name a child for the Northern (or indeed Southern) President. In an effort to get some idea of the prevalence of this practice I decided to examine the 1870 US Federal Census. My aim was to ascertain how many children estimated as being born around 1861 had been christened ‘Abraham’, ‘Abe’ or had ‘Lincoln’ as part of their christian name. Similarly I repeated the search using the same data for ‘Jefferson’, ‘Jeff’ and those who had ‘Davis’ as part of their christian name.

The results are presented in the tables below. They naturally have to be treated with caution, as they do not allow for alternate spellings (e.g. ‘Abram’ or ‘Jeferson’), nor do they include those who were only recorded by initial, or indeed those who had previously died. Neither can it discriminate between those who were named for reasons other than to honour Lincoln and Davis, e.g. as part of family tradition. Therefore the numbers are not absolute, and there is some potential crossover of individuals (notably with regard to the ‘Lincoln’ and ‘Davis’ elements). Nevertheless taken in a general sense it is an interesting reminder of how many people chose to make a marked and permanent statement about just whose side they were on in 1861.

Born c.1861 in United States named ‘Abraham’

1,183

Born c.1861 in United States named ‘Abe’

87

Born c.1861 in United States in which ‘Lincoln’ forms a part of their christian name

1,051

TOTAL

2,321

Table 1. 1870 US Federal Census Data for ‘Abraham’, ‘Abe’, ‘Lincoln’ (Ancestry.com)

Born c.1861 in United States named ‘Jefferson’

1,874

Born c.1861 in United States named ‘Jeff’

860

Born c.1861 in United States in which ‘Davis’ forms a part of their christian name

685

TOTAL

3,419

Table 2. 1870 US Federal Census Data for ‘Jefferson’, ‘Jeff’, ‘Davis’ (Ancestry.com) (3)

That these names increased in popularity as a result of the two men ascending to political power is clear. As a comparative there were 486 children named ‘Abraham’ and 284 named ‘Jefferson’ who were born in c.1851, providing an indication of these name’s pre-war popularity. The fact that thousands of children were named for these men is testament to the strong feelings on both sides at the time. These figures suggests that in the naming stakes at least, Jefferson Davis may have had one over on Abraham Lincoln in the war’s early days. (4)

One individual not represented in these figures is Abraham Lincoln Dooley, as I have been unable to locate him on the 1870 Federal Census, or indeed find any further reference to him beyond the New York Irish-American. Perhaps he chose not to be defined by the name of the sixteenth President, and went by another name in later years. It is also possible that like so many others in this period he did not survive beyond childhood. Hopefully some further information will emerge that will reveal his ultimate fate.

(1) New York Irish American 1861; New York AG Report 1893: 613; (2) John Dooley Pension Index Card; (3) 1870 Federal Census; (4) 1860 Federal Census;

*I am extremely grateful to friend Mark Dunkelman, historian of the 154th New York Infantry, for bringing this account to my attention. Mark has written some exceptional books on different aspects of the 154th’s history and memory- you can find more at his site here.

References & Further Reading

New York Irish-American 28th September 1861. The “Irish Rifles,” 37th Regiment, N.Y. Volunteers

New York A.G. 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York for the Year 1893.

John Dooley Pension Index Card. Application No. 431707, 24th October 1881.

1860 US Federal Census (Ancestry.com)

1870 U.S. Federal Census (Ancestry.com)

Filed under: 37th New York, New York Tagged: 37th New York, Abraham Lincoln,

April 13, 2013

‘Good-By, Good-By’: Richard Byrnes Writes a Final Letter to His Wife

On 17th May 1864, Colonel Richard Byrnes of the 28th Massachusetts Infantry paid an early morning visit to Father William Corby, Chaplain of the Irish Brigade. A regular army officer before the war, the strict disciplinarian had been appointed to command of the 28th in the autumn of 1862. Now, on the bloody battlefield of Spotsylvania Court House, the Cavan native confided in Corby. The veteran officer was sure this day would be his last. As he put it to the Chaplain, he felt he was about to get his ‘discharge.’ (1)

Colonel Richard Byrnes (Donahoe’s Magazine)

Richard asked Father Corby to hear his confession, and afterwards handed the priest a slip of paper. It contained instructions on what he wanted done with his effects following his death. He also asked that the following letter be delivered:

May 17, 1864.

My Dear Ellen,

I am well. No fighting yesterday; but we expect some to-day. Put your trust and confidence in God. Ask His Blessing. Kiss my poor little children for me. You must not give up in despair- all will yet be well. My regiment has suffered much in officers and men. I am in good health and spirits. I am content. I fear nothing, thank Heaven, but my sins. Do not let your spirits sink; we will meet again. I will write you soon again; but we are going to move just now. Good-by, good-by; and that a kind and just God may look to you and your children is my fervent prayer.

Richard. (2)

Richard Byrnes handed the pencil-written letter to Corby, asking him to send to his wife if, as he expected, he fell in the coming battle. But Richard did not die on 17th May. He survived Spotsylvania to take command of the Irish Brigade in time for their next battle, at Cold Harbor, Virginia. Here, just over two weeks after his feeling of impending death, Richard Byrnes was mortally wounded. He was transported to Washington, where Ellen was able to see him before he died a few days later. The correspondence he had handed to Father Corby remained in the Chaplain’s possession- although the foreboding felt by Richard Byrnes had ultimately proved well founded, the need for the letter’s delivery was overtaken by events. (3)

(1) Corby 1893: 237-8 (2) Ibid. (3) Ibid.

References & Further Reading

Corby, William 1893. Memoirs of Chaplain Life: Three Years in the Irish Brigade with the Army of the Potomac

Civil War Trust Battle of Spotsylvania Court House Page

Civil War Trust Battle of Cold Harbor Page

Filed under: 28th Massachusetts, Battle of Cold Harbor, Battle of Spotsylvania, Cavan Tagged: Battle of Cold Harbor, Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Cavan, Civil War Trust, Colonel Richard Byrnes, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, William Corby

April 3, 2013

‘Watch the Man’s Movements’: Illegal Recruitment for the Union in Ireland, Part One

A previous post explored the case of the USS Kearsarge, which caused a major diplomatic incident when she illegally recruited in the port of Queenstown (now Cobh), Co. Cork during the war. It was not the only time when questionable recruitment tactics led to friction between Britain and the United States. In 1864 the actions of a man called Patrick Finney led to a number of Irishmen unexpectedly joining the 20th Maine and 28th Massachusetts Regiments. How did they get to America? In the first of two posts on the story, we explore the methods Patrick Finney used to get perspective recruits from Ireland to the United States.

Colors of the 20th Maine Infantry (Image via Wikipedia)

In 1864 Patrick H. Finney, a native of Loughrea, Co. Galway, arrived in Ireland to work as an agent, ostensibly recruiting men to work on industrial projects in the United States. The authorities quickly began to suspect that this was just a cover story, and that in reality Finney was looking for men to serve in the Union army. That such activities might occur is hardly surprising, given the large bounties available at this point in the war for enlistment- there were potentially big profits to made. Finney was barely off the boat before the police began to monitor him; the Sub-Inspector of the Constabulary in Galway reported that ‘steps have been taken to watch the man’s movements.’ That January he was arrested in Loughrea on suspicion of breaching of the Foreign Enlistments Act, which made it illegal in British territories to recruit for service in foreign armies. However there was not enough evidence to hold the Galway man, and he was soon released. (1)

Unperturbed, Finney continued to travel around Ireland to gain recruits. He remained under suspicion, and somewhat foolishly failed to keep a low profile. On 28th January he was brought to court in Dublin by William Pike, who alleged that Finney owed him money. A Mr. McKenna took the stand as a witness for Pike, and stated that Finney was hoping the men he recruited would join the Union army:

…Finney, after his return from Galway, said he wanted tip-top men…Finney showed him [McKenna] the bounty that was being given for the American army, and from some conversation with him he believed that that was the purpose for which he wanted the men; Finney said he conceived they would all join the army when they saw the amount of wages and the bounty that were being given..’ (2)

Despite this evidence Finney was able to produce documentation which showed he intended to recruit only for businesses, and so he escaped sanction. He continued his work. On 16th February 1864 it was reported to the Dublin Metropolitan Police that he had recruited 70 men around the Loughrea-Galway area. Finney next set up an office in the back room of a cottage on Guild Street in Dublin, where he continued to sign up more men. They had been offered free passage, steady work, and the equivalent of £2 a month with board and two new suits a year. The text of the declaration that each man signed survives, and is worth reproducing in full:

We, the undersigned, hereby agree with Patrick H. Phinney [Finney], that in consideration of the said Patrick H. Phinney advancing the money necessary for the payment of our respective passages to Boston, in the United States of America.- that we, each of us hereto signing our names (or making our marks in presence of witnesses), hereby agree with said P.H. Phinney, that we will on our arrival at Boston aforesaid, commence to labor for said Patrick H. Phinney or his assigns, either on the Charlestown waterworks, in the City of Charlestown, or the Webster and Southbridge Railroad, in the employ of Wall and Lynch; or the Boston, Hartford and Erie Railroad, in the employ of E. Crane, in the State of Massachusetts; or the Pacific Railroad; or the Bear Valley Coal Company, in the employ of George P. Sanger; or the Franklin Coal Company, in the employ of E.C. Bates, in the State of Pennsylvania.

And we hereby agree that we will, each of us hereto signing as aforesaid, continue to labour and work to our best ability for the said P.H. Phinney, or his assigns, for the term of twelve months, from the date of our arrival in said Boston, for and at the rate of ___ dollars per month, in addition to our board and lodging, which is to be furnished to us by the said P.H. Phinney.

And we each of us hereby agree that we will repay to said P.H. Phinney, or to his assigns, the amount which will have been paid by the said P.H. Phinney, or his assigns, for each of our passages to Boston as aforesaid, and also those of us who shall have had our inland passages paid for us by the said P.H. Phinney, or any other advances which may have been made to us by the said P.H. Phinney, or that the same shall be deducted from or repaid from our wages first earned as aforesaid, and paid to said P.H. Phinney or his assigns by our employers.

It is understood that the wages aforesaid of each of us will commence within one week after our arrival in Boston, or as soon as we commence work. (3)

In all 102 men agreed to travel from Dublin. Finney instructed them to proceed to the Office of Mr. Delany at 13, North Wall, where they were given tickets for their passage to the United States via Liverpool. Although suspicious, the authorities were unable to procure enough evidence of Finney’s real intentions to prevent their departure. The men set sail from Liverpool aboard the Nova Scotia bound for Portland in Maine, from where they were to proceed by train to Boston. The Nova Scotia arrived in Portland on 9th March, 1864. Seven of the men got not further, apparently coerced into the ranks of the famous 20th Maine. The majority got as far Boston, where they were soon informed that there was no work to be had. It was put to them that perhaps they might like to enlist in the 28th Massachusetts. The actions in both Portland and Boston caused consternation among the local Irish-American populations, and became a major news story. Part Two of the post will examine the fate of the men after their arrival- particularly those who went to war with the 20th Maine- and the political tug of war that their cause created. (4)

(1) Hernon 1968:31, North American Correspondence 1864: 5 (2) North American Correspondence 1864:6, Hernon 196832; (3) North American Correspondence 1864: 2-3, 13, Sydney Morning Herald; Hernon 1968:32; (4) North American Correspondence 1864:13;

References

Hernon, Joseph Jnr. 1968. Celts, Catholics and Copperheads: Ireland Views the American Civil War.

North American Correspondence N0.8, 1864 Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. Correspondence Respecting Recruitment in Ireland For The Military Service of the United States.

Sydney Morning Herald 23rd June 1864. Recruiting in New York.

Filed under: Discussion and Debate, Recruitment Tagged: 20th Maine, Foreign Enlistment Act, George P. Sanger, Irish American Civil War, Loughrea, Nova Scotia, Pacific Railway, Recruitment