Damian Shiels's Blog, page 31

April 15, 2016

The Famine Irish: Emigration and The Great Hunger

Back in 2013 I was privileged to speak at the Third Annual International Famine Conference at Strokestown Park House, Co. Roscommon. The theme of the event was The Famine Irish: Emigration and New Lives, and it was an excellent couple of days. The focus of my paper was to examine the impact of the American Civil War on female Famine survivors, something I sought to achieve largely through the Widows & Dependent Pension Files. Following an invitation to work the paper up for a future publication based around the Conference, I decided to look broadly at the value of these files as a resource for those interested in the social history of 19th century Irish people. Thanks to the encouragement and hard work of leading Famine scholar Dr. Ciarán Reilly, that volume has now been published. Edited by Ciarán, it contains a number of papers that readers of Irish in the American Civil War might find of interest. A full table of contents is provided below. If you are interested in purchasing a copy you can do so here.

The Famine Irish

THE FAMINE IRISH: EMIGRATION AND THE GREAT HUNGER

Edited by Dr. Ciarán Reilly (Postgraduate Research Fellow, Centre for the Study of Historic Houses & Estates, Maynooth University)

‘Shovelling out the Paupers’: The Irish Poor Law and Assisted Emigration during the Great Famine

Dr. Gerard Moran (Coordinator of History, European School, Lacken, Brussels)

The Mechanics of Assisted Emigration: From the Fitzwilliam Estate in Wicklow to Canada

Fidelma Byrne (Irish Research Council Postgraduate Scholar, Maynooth University)

The Experience of Irish Women Transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) during the Famine

Dr. Bláthnaid Nolan (Professional Historian, Honorary Associate University of Tasmania)

Reporting the Irish Famine in America: Images of ‘Suffering Ireland’ in the American Press, 1845-1848

Professor James M. Farrell (Professor of Rhetoric and Chairperson in the Department of Communication, University of New Hampshire)

Widows’ and Dependent Parents’ American Civil War Pension Files: A New Source for the Irish Emigrant Experience

Damian Shiels

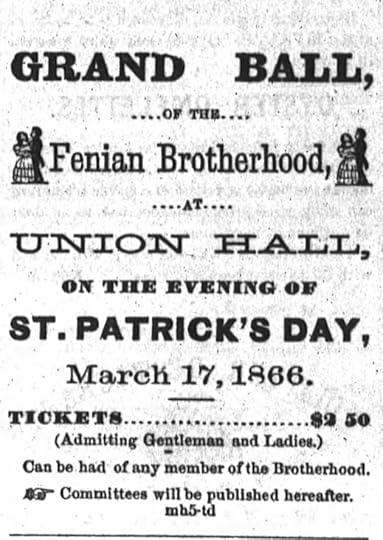

From Emigrant to Fenian: Patrick A. Collins and the Boston Irish

Professor Lawrence W. Kennedy (Professor of History, University of Scranton)

The Women of Ballykilcline, County Roscommon: Claiming New Ground

Mary Lee Dunn (Independent Scholar, Founder of the Ballykilcline Society)

Constructing an Immigrant Profile: Using Statistics to Identify Famine Immigrants in Toledo, Ohio, 1850-1900

Dr. Regina Donlon (Irish Research Council Postdoctoral Research Fellow, National University of Ireland, Galway)

‘The Chained Wolves’: Young Ireland in Exile

Professor Christine Kinealy (Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, Quinnipiac University)

‘There is No Person Starving Here’: Australia and the Great Famine

Dr. Richard Reid (Senior Curator of National Museum of Australia Exhibition on the Irish in Australia)

The Irish in Australia: Remembering and Commemorating the Great Famine

Dr. Perry McIntyre (Adjunct Lecturer, University of New South Wales)

‘Une Voix d’Irlande’: Integration, Migration, and Travelling Nationalism between Famine Ireland and Quebec

Dr. Jason King (Irish Research Council Postdoctoral Research Fellow, National University of Ireland, Galway)

Languages of Memory: Jeremiah Gallagher and the Grosse Île Famine Monument

Dr. Michael Quigley (Editor, Canadian Association for Irish Studies Newsletter, former Action Grosse Île Historian)

Filed under: Publication Tagged: Dependent Pension Files, Dr Ciaran Reilly, Famine Publication, Historical Research, History Press, Irish American Civil War, The Famine Irish Emigration and the Great Hunger, Widow's Pension Files

April 12, 2016

“The Lives of Her Exiled Children Will be Offered in Thousands”: Edward Gallway, Fort Sumter & Foreseeing the Cost of Civil War

The first soldier to lose his life in the American Civil War was Daniel Hough, a former farmer from Co. Tipperary. The unfortunate man died following an accidental explosion that took place while the Fort Sumter garrison fired a salute to the flag following their surrender. That explosion wounded a number of other men, and within days Hough was joined in death by another Irishman- Edward Gallway– the second soldier to lose his life in the Civil War. The fact that the first two men to die both hailed from Ireland was perhaps unsurprising, given that there were more Irish-born than American-born troops in the Sumter garrison. It was news of Gallway’s death that appears to have reached Ireland first. At a time when few envisaged the slaughter to come, one Irish newspaper, in reporting his fate, was remarkably prescient about what the conflict would cost not just America, but Ireland. Their prediction that “the lives of her exiled children will be offered in thousands”, proved remarkably accurate. Unhappily, so did their warning that “many a fireside…will be filled with mourning as each American mail arrives.” That certainly proved the case for the Gallways, who would experience it for a second time before the guns fell silent.

The Bombardment of Fort Sumter on 12th April 1861 (Library of Congress)

Edward Gallway (there a number of variants of his surname, including Gallwey and Galway) was not a typical Irish soldier. He was well-educated, and prior to his enlistment had worked as a clerk. He enlisted on 23rd November 1859 in Moultrieville, South Carolina, at the age of 20 and was described as 5 feet 9 inches tall, with grey eyes, fair hair and a fair complexion. The register of enlistments records that the 1st United States Artilleryman “died Apr. 14 ’61 accidental explosion of gunpowder while firing salute after bombdt at Ft. Sumter S.C.” His death prompted the below piece in the Dublin Nation, which was later carried in the Weekly Wisconsin Patriot on 20th July 1861. (1)

THE IRISH ON THE DEATH-ROLL

Of five thousand men who marched from New York in one week for the war in the South, three thousand were Irish. From nearly every city in America, the scene of similar departures, we hear of like proportion of the Irish element in battalions; for whenever there is danger to be braved or courage to be displayed, the Celtic exile is found in the foremost ranks. Let England be troubled as she may for her cotton bales, it may be truly stated that Ireland will be more deeply, more mournfully, affected by the disasters in America, than any other country in the world. The lives of her exiled children will be offered in thousands. Many a mother’s heart in Ireland, long cheered by the affectionate and dutiful letter and the generous offerings of filial love, will be left lone and widowed by the red bolts of war. Many a fireside from Dunluce to Castlehaven will be filled with mourning as each American mail arrives. Even already it has begun. Already, light as is the reckoning of dead, Ireland has paid the largest penalty. It was only a day ago we were told that three young men had been killed by the bursting of a gun at Fort Sumter. We now find that, of the whole garrison which defended the fort, the greater, part were Irish; while of the three killed at the sallyport, two were Irishmen! One of these was Edward Galway, of Skibbereen, in Cork county, as brave a young Irishman as ever stood on a tented field; and higher tribute still, as affectionate and dutiful a son as ever cheered a parent’s heart. In his native town where he and his honored parents were known but to be respected and loved by all, the news has caused a gloom and sorrow- the utterance of earnest sympathy and the presage of dark fear that threaten many a parent’s heart besides the on thus stricken now. Each one begins to realize the horrors of such a war as that now enveloping America; a war threatening as much sorrow, widowhood and affliction to the home of Ireland, as of America itself.– To the families of our fallen countrymen it must, however, be a proud feeling that they have fallen nobly, attesting the gratitude and fidelity of Irishmen to the homes of their adoption. Yet for us, as we behold this mournful spectacle of valor and devotion in such a cause– our brothers falling in a strife that never should have been waged– we cannot restrain the death-cry of Sarsfield, on Landenalion:– “Oh that it were for Ireland!” (2)

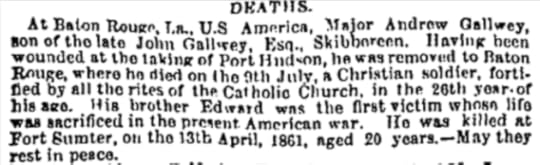

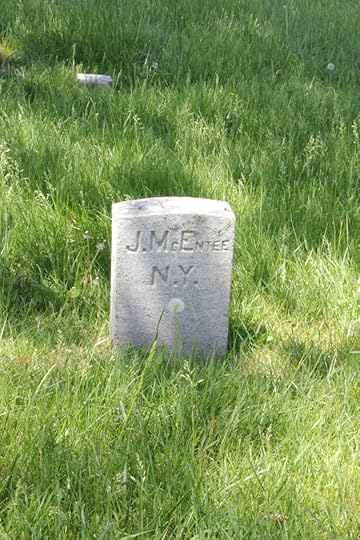

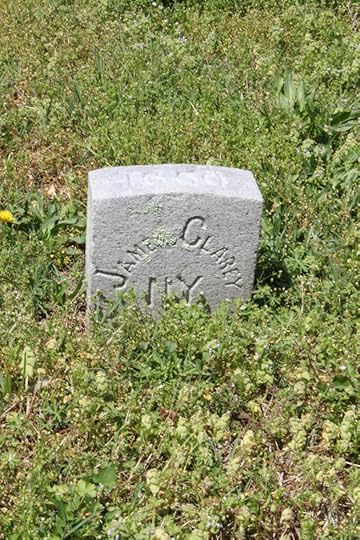

Although lacking in accuracy in some detail (e.g. the proportional number of Irish, and the fact that three Irish were killed at Fort Sumter), much of the piece accurately foresaw what was to come. For the Gallway family in Skibbereen, that included the death of a second son. His name was Andrew Power Gallway, a Major in the 173rd New York Infantry, often referred to as the 4th Metropolitan (Brooklyn) Regiment. He had enrolled at the age of 25 on 13th September 1862. His obituary in the Cork Examiner of 10th August 1863 is shown below, as is his obituary, which accompanies his muster roll abstract and identifies his nativity precisely to Greenpark, Skibbereen. (3)

The obituary of Andrew Power Gallwey carried in the Cork Examiner on 10th August 1863

Another gallant soldier and gentleman has been taken to a better world. A. POWER GALLWEY came to the United States from Ireland about six years ago. He was a son of the late Andrew Gallwey, Esq., of Greenpark, and was related to the Powers’ and other ancient families of the county Cork. He entered the banking house of his cousin, Mr. Gebhard, of the firm of Schuchard & Gebhard, soon after his arrival in New York, and continued to reside there until the present war broke out. His honest, jolly face, graceful manner and lively conversation will long be remembered by the habitues of the opera and those who were in society at that period. Gen. Meagher having selected him, together with the late Temple Emmet, as members of his staff, he was with the Irish Brigade until the close of General McClellan’s campaign on the Peninsula. Last summer he was appointed by Governor Morgan, Major of the 173d Regiment, N. Y. S. V., and served with his regiment under Gen. Banks.—He was acting as Colonel of his regiment at the time of the attack on Port Hudson, and was shot through the right lung while leading his men in the charge on that place. His wound was not considered fatal, yet he only lingered till July the 8th, when he died. He was well educated, of a refined nature, with which was combined deep religions feeling, and by his kindness of heart and open frankness, had made many warm friends in this country. He was fond of open air exercise, field sports and feats of horsemanship, and was perfectly familiar with the use of the gun and the rod. Many in N. York will remember the songs he wrote and sung and the many stories, some merry, some pathetic, which he was accustomed to tell. The news of his death will produce a sad feeling in the hearts of all who ever knew him. May heaven support his widowed mother in another country in this irreparable loss of her darling son. W. (4)

If you would like to read more about the Irish in Fort Sumter, there is a section dedicated to it in my book, but you can also learn of the experiences of Dubliner Commander Stephen Rowan, who attempted to relieve the Fort, here, musings regarding the nativity of the first fatality, Tipperary’s Daniel Hough, here, and the claims of Galwegian James Gibbon to have been the man who fired the first Federal shot of the war here.

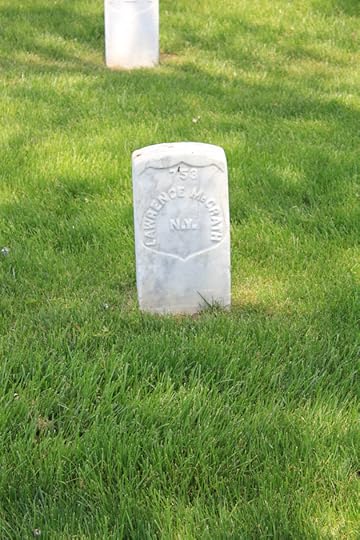

The grave of Andrew Power Gallway at Saint Joseph Catholic Cemetery, Baton Rouge, Louisiana (Diane, Find A Grave)

(1) U.S. Army Register of Enlistments; (2) Weekly Wisconsin Patriot; (3) New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (4) New York State Military Museum;

References & Further Reading

Weekly Wisconsin Patriot 20th July 1861

Cork Examiner 10th August 1863

U.S. Army Register of Enlistments (NARA)

New York Muster Roll Abstracts (New York State Archives)

New York State Military Museum. 173rd Regiment Newspaper Clippings

Andrew Power Gallway Find A Grave Memorial

Filed under: Battle of Fort Sumter, Cork Tagged: Cork Emigrants, Cork in America, Daniel Hough, Edward Gallway, Fort Sumter, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Skibbereen Emigrants

April 9, 2016

“I Saw San Francisco When it Was Only a Village”: The Voices of California’s Irish Pioneers

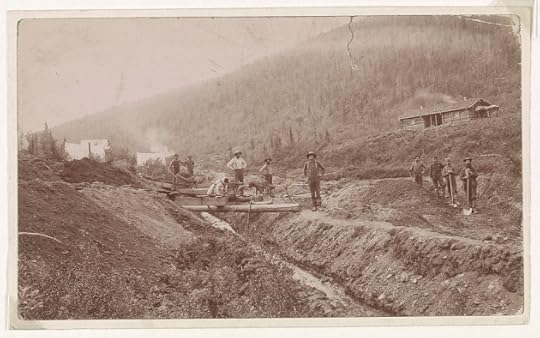

Laurence Macken was born in Slane, Co. Meath on 12th May 1828. In 1850 he was a young man just three days shy of his 22nd birthday when he landed in the California Territory, one of the thousands of emigrants and natives alike who had been infected by the gold fever that had spread like wildfire throughout the United States after 1848. The men who left their old lives behind to head West in pursuit of the precious metal would be immortalised as the “49ers”, and though most failed to find their fortune, they changed California forever. Laurence was one of those who never left. The Meath man– who remained a miner until 1871– died in Napa on 20th July 1907, having been a resident of The Golden State for nearly six decades. To mark his death that year, a relative recounted the story of Laurence’s journey to California, as part of a company of Massachusetts gold-seekers:

He came to Boston at the age of 19 and lived on the island of Nantucket until the old excitement broke out in Calif. [the California Gold Rush] With others he formed a company in Nov. 1849 and manned the whaling bark Powhattan and came around the Horn arriving in S.F. [San Francisco] in May 1850. They then continued on to Sacramento towing the bark by hand up the Sacramento River and were a month in making the trip from S.F. to Sacramento. The company then proceeded to a point on the middle fork of the American River, then known as “Spanish Bar” and began mining operations. After working in common for several months, the company dispersed. Mr. M then prospected at Sonora, Poverty Hill, Don Pedro’s Bar and on into Mariposa County where he engaged in pocket mining for a number of years.

Gold miners in California in the late 1840s or early 1850s. Irish flocked from not only the United States but also from Ireland and Australia to participate (Library of Congress)

Laurence Macken’s death warranted an obituary in the local Napa press, which recounted the story of his company of Bostonians and their journey with the Powhatan. Aside from telling his tale as a pioneer, it also noted his contribution to the later development of California, notably the fact that he spent many years as Superintendent of the Napa State Hospital grounds.

Laurence’s story is one of those that form part of the collection known as the Pioneer Index Files in California State Library. It was started in the early years of the early 20th century, in order to record something of the lives of pioneers who arrived in the territory and state before 1860. As with Laurence’s file, much of the biographical information was provided by the children or later descendants of these pioneers, and sometimes included additions such as newspaper clippings. Well over 100 of the files relate specifically to people who had been born in Ireland. In a number of cases, it was actually the aged California pioneer themselves who recounted the basics of their story. I have gone through a small number of the files in search of the voices of some of these original Irish pioneers in California. Some travelled to their new home in covered wagons across the Plains, while more took to steam and sail to arrive at their destination. They witnessed the development of San Francisco, worked gold mines along the American River, and were part of the famed enterprise that was the Central Pacific Railroad. We hear from nine of them below.

William Barry, Rochfortbridge, Co. Westmeath, 1906

William was born on 2nd October 1831 to Edward Barry and Jane (née O’Byrne). He had arrived in California on 1st May 1852, via a sailing vessel which came from Australia around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope (many of the California Irish pioneers arrived via Australia). During his time in California he had lived in Niles, Centerville and Mission San Jose in Alameda County, and San Juan in Monterey County. He had worked as an orchardist and from 1885 had been employed by the Horticultural Commission of Alameda County. A Republican in politics, he had received his early education in Ireland. When he gave his statement he was living in Niles, Alameda County. He described how he arrived in California thus:

Left Liverpool Eng. April 2nd 1851, a sailor on the ship Satellite bound with passengers for Port Phillip (now Melbourne) Australia arriving there in July, being the first ship to enter that harbor after the gold was discovered in Australia. Thence we sailed for Port Adelaide Australia, thence to Valparaiso, Chile, South America, arriving in San Francisco May 1st 1852 being one month lacking one day on the voyage. With the exception of 2 years in Monterey Co. I have been a resident of Alameda Co. for 54 years.

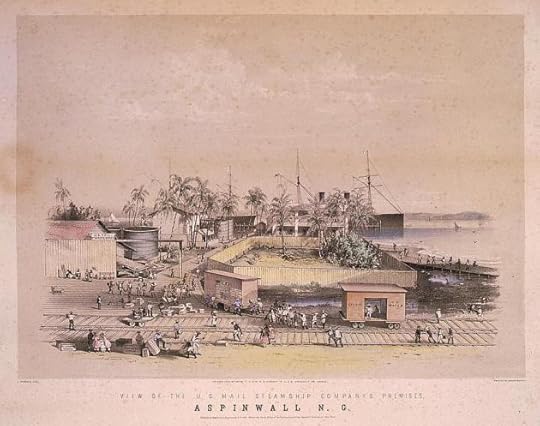

Aspinwall New Granada (Panama), an important stop for many passengers en-route to San Francisco, such as Michael Calhoun Dufficy (Library of Congress)

Michael Calhoun Dufficy, Strokestown, Co. Roscommon, 1906 & 1919

Michael was born on 31st December 1839 to Francis Dufficy and Alicia (née Jones). He had married Edwina O’Brien in Marysville, California on 2nd February 1863. Edwina had come to California across the Plains with her father in 1849, and the couple would go on to have nine children. Michael had arrived in California in December 1852. He had taken the steamer Falcon to Aspinwall, crossing the Panamanian isthmus before taking the Northerner from Panama to San Francisco. Prior to that he had made his home in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he had lived between 1846 and 1852 and where he had been educated. In California Michael had first made his home in San Francisco before moving to Marysville. He was an Attorney, and in 1894 was admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of California. He served two terms as the Justice of the Peace for San Rafael, and was by politics a Democrat. A candidate for the assembly for Yuba County in 1873 and for Superior Judge in Marin County in 1898, Michael died in 1919.

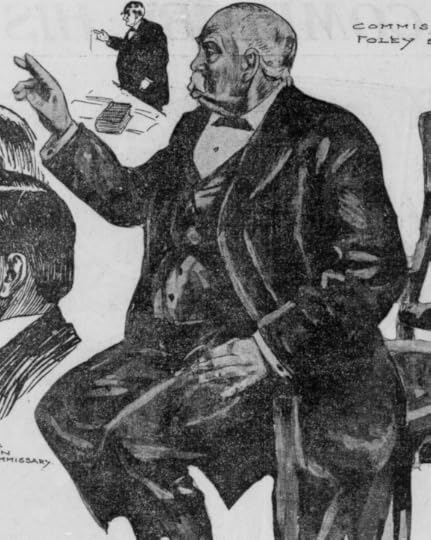

Francis Foley, Fermoy, Co. Cork, no date

Francis was born on 3rd December 1827 to John Foley and Bridget (née Birmingham). He was educated in Ireland, where he was apparently intended for the priesthood. After emigration he spent a short time in New York, before journeying overland across the Plains to California, arriving on 25th August 1849. Francis was twice married, first in San Francisco in 1852 and again in San Juan in 1859. He took great pride in the fact that he had held the position of Commissary at San Quentin Prison under Governor Gage; in politics he related that he had been a Democrat, “but free trade changed me into [a] thorough Republican.” Both of his marriages produced children, and one of his son’s by his first marriage was the law partner of Governor Gage.

Francis Foley in later life, as depicted in his role as Commissary of San Quentin in the San Francisco Call, 29th August 1902 (California Digital Newspaper Collection)

Robert Gordon, Co. Monaghan, 1906

Robert was born in September 1823 to James Gordon and Jane (née Harbison). Educated in Ireland, he had first landed in New York before taking a steamer to California, arriving on 9th January 1852. He married on 26th February 1866 in Bloomfield, and made his home near Petaluma, where he made a living as a farmer and stockraiser. The highest office he had held was as a school trustee, and he was by politics a Republican. He felt that among his most notable achievements was that he had “raised as high as sixty bushels of wheat per acre and ten tons of potatoes.” He went on:

These rich and productive lands are pastureing stock at present after we spoiled it; plou[gh]ing the ground up spoiled the pasture age, the farmers now are living by stock with a few hundred hens to a few thousand hens…

John Sarsfield Gorman, Ireland, 1909

Born in Ireland on 8th May 1846 to Martin Gorman and Margaret (née Byron). Prior to moving West he lived in New York and Rhode Island, where he was educated, and ultimately landed in California via the steamers Nebraska and Nevada in the Autumn of 1867. He married Mary Louise Levine in San Francisco on 11th October 1881. He worked in Camp Independence and Darwin in Inyo County, as well as “all the early mining camps around Nevada.” This was unsurprising given his trade as a Master Smelter; he also spent time as a “mining expert” and rancher. In terms of public office, he served as Sheriff and tax collector in Inyo County, and was Chairman of the Republican County Central Committee for Inyo across two terms. He remembered that he was “in Darwin when Vasquez [a notorious bandido] was robbing people…and helped to guard the camp when a raid from his band was looked for.” He also noted that in 1895 he made a stand as Sheriff “to prevent white men from selling liquor to Indians.”

The bandido Tiburcio Vasquez, who John Sarsfield Gorman remembered operating in California (Santa Cruz Public Library via Wikipedia)

Jerome Madden, Clonakilty, Co. Cork, 1906

Jerome thought he was born around 5th March 1829, though his only record of it was burnt in the Sacramento Fire of 1852. His father had been John Madden, his mother Catharine (née Fitzpatrick). He had married Margaret Eveline Evans on 9th June 1869 in the Congregational Church in Sacramento. Jerome remembered that he had emigrated in 1842 and spent two years in New York, before living in Canada between 1844 and 1846. Returning to New York from 1846 to 1849, he journeyed to California that year via the sailing packet South Carolina around the Cape, making landfall in San Francisco on 30th June 1849. Jerome was a 49er– he recalled making his home at “mines in various counties” between 1849 and 1854 (he became a naturalised citizen in 1853). He moved on to Sacramento between 1854 and 1873, and then to San Francisco and San Mateo from 1873 to 1906. After his five years as a miner, Jerome had worked variously as a searcher of records and land titles, country recorder and auditor, and county clerk and recorder until 1865, when he became an assistant to an attorney working for the Central Pacific Railroad. He spent ten years connected to the famed company, before moving on to the Southern Pacific Railroad where he was employed until 1903. He described himself as a “strong Unionist in 1862 to 1865 and a member of Union League of Sacramento.” Jerome was also a member of the Washington No. 20 Sacramento City Masonic Lodge from 1854 through to 1906, and was living in Berkeley when he gave his account.

John Wallace McBride, Ireland, 1909

Born on 6th May 1836 to Owen McBride and Ann (née Goldrick). He was married in California on 13th February 1866. Having first arrived in New York, J.W. spent time in Missouri and South Carolina before taking the overland route into California, arriving on 1st October 1852. He recalled his early years as follows:

Left Ireland very young– landed in New York. Visited various cities in the U.S. Left St. Louis May 5th 1852 with my father. Crossed the Truckee dessert and came through the Beckwith [Beckwourth] Pass. Before reaching our destination supply exhausted. We landed on the North Yuba in a rich missionary camp.

John said he had been educated in St. Louis and the Plains. During his working career he spent time as a miner and a farmer, and had lived in Forbestown, Sacramento, the Salmon River and Callahan since he had been in The Golden State. In terms of public offices, J.W. had been County Supervisor of Siskiyou County, a member of the board, and a member of the State Legislature as a Democrat.

The Beckwourth Pass, the lowest pass in the Sierra Nevadas, and an overland route for settlers on their way to California, including John Wallace McBride (Moabdave via Wikipedia)

Patrick McErlane, Lisnagrot, Co. Derry, 1906

Born on 16th March 1822 to Michael McErlane and Mary (née Scullon). He had married Margaret Cronin in San Francisco in November 1855, but by the time he gave his account he had been a widower for 34 years. Having initially emigrated to New York, it took him three attempts to get to California, eventually landing on 23rd August 1852, having left New York in February. He initially lived in Bolinas for 10 years, where he helped to build the first sawmill constructed there. He then moved to San Francisco and finally to Petaluma in April 1868. When he first arrived in the state he worked as a carpenter, but latterly became a fruit grower. Patrick recalled that he had been educated in Ireland, and by politics was a Democrat or Independent. He died on 23rd February 1908, and his nieces sent in his obituary from the Petaluma Argus Courier which added more detail with regards to his initial efforts to reach California:

…May 12th, 1847, having left England he arrived at New York. In New Hamburg, New York State, he worked for his cousin in a large grocery and dry goods store. Next he decided to reach California. He sailed to Panama and found that his ticket from that region to this State was a fake. At Panama he secured a passage to San Francisco for $130. After being out 60 days in an unfavorable wind– they could not get passage on the regular steamer– the captain made for San Blas on the Mexican coast which they reached 5 days later. Next they were obliged to put in at Honolulu…At Honolulu about 50 passengers, among whom was Mr. McErlane, chartered a vessel for San Francisco. After being out fifty-one days they sighted Bolinas in Marin county as the ship was in some danger the first officer, Mr. McErlane and others, took a small boat and landed at Bolinas. They walked ten miles to Olema where Mr. McErlane got employment at a sawmill.

James Hill, Corr Hill, Co. Cavan, 1906

Born on 17th April 1834 to Bernard Morris and Annie (née Tully). Educated in Ireland and Santa Clara College, he was married to Miss M. Colbert on 22nd May 1866 in Weaversville. Before heading to California he had lived in Albany and Congress Hall for six years. He arrived in March 1852 via steamer and sailing ship, recalling his journey as follows:

Left New York on Steamer U.S. States her first trip– bought a through ticket to San Francisco was swindled as they had nothing on this side to take us up. Sta[y]ed 3 weeks in Panama and then agent…charted English Brig…to take us to S.F. [the subsequent journey took weeks, with harsh rationing of supplies becoming necessary]

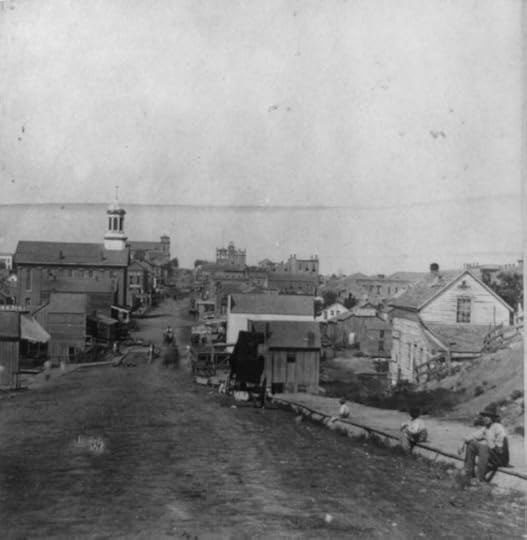

By August 1852 he had move to Weaversville, where he settled for good, engaging in activities such as livestock and sawmilling. He became Director of the County Fairs in Trinity and Shasta Counties and was Chairman of the local Republican committee. Looking back, he recalled that he “saw San Francisco when it was only a village. Oriental Hotel best in the city [was] only a two story frame building.”

The Pioneer Index Files are a fascinating resource, which offer yet another opportunity to explore the individual Irish experience of 19th century immigrant life in the United States. Each of these stories was compiled from scans of the original files on http://www.ancestry.com, and it is hoped to return to them in a future post on the site.

San Francisco in 1851 (Library of Congress)

References

California State Library – Sacramento Co, Sacramento, California, Pioneer Index File (1906–1934). Scans of original index cards accessed via Ancestry.com

California Digital Newspaper Collection. San Francisco Call Volume 87, Number 90, 29th August 1902.

Filed under: Life in America Tagged: 49ers, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish in California, Irish in the California Gold Rush, Irish in the Old West, Irish on the Central Pacific Railroad, Irish Pioneers in America

April 6, 2016

“I was Forewarned by a Dream”: 1860s Emigrant Letters between Kansas & Kerry

On 3rd September 1863 Private John Shea of the 1st Kansas Infantry, Company B, died of Chronic Diarrhoea at Natchez General Hospital in Mississippi, having fallen sick just over a week before. The pension file his mother subsequently claimed based on his death centres around a series of letters written home to Ireland by John during the war, which proved her financial dependence on him. These letters provide fascinating insight into Irish emigrant life, particularly the sense of duty that many of the Irish in America felt toward those they had left behind. The file also has a very rare inclusion– a letter written to America from Ireland– which describes a premonition of John’s death. (1)

Fifth Street, Leavenworth, Kansas as it appeared in 1867. Dennis Shea from Caherciveen, Co. Kerry enlisted here (Library of Congress).

When John’s 60-year-old mother Mary applied for her pension in Worcester, Massachusetts on 22nd January 1864, she recalled that she had been married to Dennis Shea in Caherciveen, Co. Kerry around the year 1833. The couple had seven children, but by 1864 only one was left alive. That child’s name was also Mary, who had been born on Christmas Day, 1846. John’s mother had no certificate to prove her marriage, but as was typical for Irish applicants, she was able to draw on a close network of Kerry relatives and friends in America to assist her. Both Dennis Shea and Dennis Murphy accompanied her that January, to swear that they had attended her wedding ceremony back in Ireland. (2)

Though there is no detailed affidavit from Mary Shea in the file, the letters of her son sufficed to prove her entitlement to a pension. John had enlisted in Leavenworth City, Kansas, on 3rd June 1861. His mother was still in Caherciveen at the time, and the letters he wrote to her travelled across the Atlantic. There are three contained in the application; the first written from Tipton, Kansas on 6th October 1861, the second from Memphis, Tennessee on 11th January 1863 and the third from Louisiana on 20th April 1863. Rather than look at the letters in chronological order, I decided to instead explore a number of themes within them. (3)

Communications & Remittance

It is apparent from the letters that the extended Shea family were spread out across both the United States and Ireland. Based on Mary’s 1864 application, it seems probable that a group of the Caherciveen emigrants were based in Massachusetts, while John, and perhaps others, were as far west as Kansas. At least some of John’s letters home to Ireland relied on this network, as he sent and received letters from his mother through a U.S. based relative who was in a more permanent address. This is evidenced a number of times. In his October 1861 letter John asked his mother to:

…excuse me for not writing to you before now the reason why I did not write is that I was not in anny perminant place that I might expect an answer from you…

The fact that he was not communicating directly with her is again highlighted in his January 1863 letter, when he indicated he had sent money through a relative, who was in turn to send it to her:

…I did not get any money in a long time. The last money I got I sint it to Ann Donely’s husband for him to sind to you…

Ann Donnelly appears to have been a cousin, and was evidently a vital link in John’s chain of remitting money to Ireland. John was later able to confirm to his mother that:

…Ann Donely’s husband wrote to me and he told me that you received the money he sint to you…

Just as John was often on the move, his mother also seems to have moved around in Kerry– again clearly suggesting his letters home were being passed through intermediaries who had more up-to-date information as to addresses. In October 1861 he asked his mother to:

…Let me know who you are stopping with now and how you are doing…

Similarly, his mother served as a hub of information about the whereabouts of other family members, some of them likely in the United States. In his April 1863 letter John reminded his mother:

…dont forget to send me my brother Patrick’s adress…

Among his siblings, John had apparently taken on most of the major burden of financially providing for his mother (and sister). Much of what he wrote illustrates just how responsible he felt for her, despite a distance over 4,000 miles. It is also apparent that he felt others in the family could contribute more to her support, particularly “Tom”, who seems to have been another brother. From his October 1861 letter:

…let me know whether Tom wrote any letter to you of late (I could do better for you if Tom helped me). Let me know if Patrick find’s you anny money or not…

The erratic nature of payment in the army during the Civil War played havoc with many men’s efforts to send money home, and it was not always possible for them to do so. In April 1863, while in Louisiana, John had to apologise for the lack of funds he was remitting:

…I hope you will excuse me I am doing my best and if I could do more I would do it…

John’s disappointment with Tom had not dissipated by January 1863, when John wrote from Memphis:

Dear Mother I received two letter of yours some time ago. One of them was the letter you told me sind to Tom. I sint him the letter but he did not answer it. There is no uce in you to sind his letter to me because he wonte answer them. I did not hear from him since last Summer so I dont know where he is…

While clearly nonplussed with Tom’s lack of commitment to his family, John was keen to help another of his siblings– his sister Mary– who was still with her mother in Kerry. In his 1861 letter he declared his intention to help her emigrate, a pattern of chain-migration that was typical of Irish emigrants:

…keep my sister to school and if I can I will soon sind for her…Let me know whether you let my sister come or not, as I donte want to be sinding for her if you donte let her come… (4)

Faith & Family

Perhaps the most common theme in emigrants letters relates to family; be it relating news about fellow family emigrants or seeking details about those at home. In 1861 John asked his mother to:

…let me know how are all the friends and acquaintances. Dinnis Shea got married and his wife died last September, Ann Shea got married I mean Michael Shea’s daughter. Catherine Shea is in good health and is living with her daughter Ann Donnely.

Despite the fact that so few Irish emigrants ever returned home, many retained a deep interest in the goings on in their homeland, particularly at a local level. In his 1861 letter, John sought to find out how things were around Caherciveen:

…Let me know how times are in the old Country at present…

Many letters of Roman Catholic Irish emigrants make reference to their religious faith, and in the case of Irish soldiers the devotional objects they wore. These were sometimes handed out to the men by chaplains, but were more commonly sent from home. They usually took the form of either Scapulars or Agnus Dei, and many thousands of Irish soldiers in the American Civil War wore then around their neck. In January 1863 John told his mother that:

…The Agnes dia you sint me I got and I think a good deal of it… (5)

Military Service

John’s letters provide a clear indication of the toll the war took on the enthusiasm of volunteers as the conflict dragged on. His October 1861 letter from Tipton spoke of how happy he was with his situation, comparing the American service favourably with that of the British military. In what was an almost universal staple of letters home written before the summer of 1862, he predicted the war would soon be over:

…I listed last may and I like it well. Sogers in this Country has good terms. I only joined for 3 years or during the war. I expect the war wonte last more than a year at most.

By 11th January 1863 in Memphis his view had changed. The hard campaigning of 1862 had made it apparent that there were many tough days still to come:

The war still holdes out as hard as it ever did and god only knows when it will end. There is hardly a day but there is a big battle fought and thousands killed and wonded. We whiped the enemy in two big battles lately and if we only could whip them in a couple of other fights I think that we would have peace… (6)

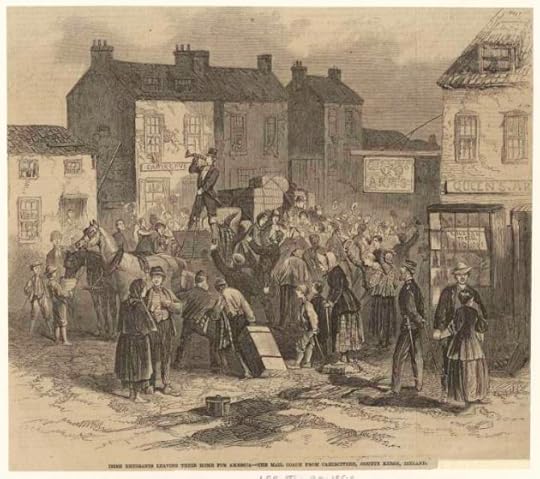

Irish Emigrants Leaving for America from Caherciveen, Co. Kerry, 1866 (New York Public Library Image ID 833634)

A Letter from Ireland

John’s letter of 20th April 1863 from Louisiana was the last prior to his death the following September. The final letter in the file was written that November, from Caherciveen, Co. Kerry. The author was a cousin of the Shea family, Daniel Clifford. It is unusual to find contemporary correspondence written from Ireland to America in the files (the more usual occurrence would be letters from Civil War soldiers to relatives in Ireland). It is difficult to piece together the sequence of events described in the letter; neither is it apparent if the letter was written to John’s mother or sister, but the latter is perhaps more likely. What the letter does ably demonstrate is how convoluted the process of written communication could be. As we saw earlier, the Sheas relied on a network of linked individuals in order to correspond with each other, and here it seems to have broken down. From the tenet of the letter, it seems that Mary was waiting to sail to the United States, perhaps to join John, but did not receive word of his death before her departure, though she apparently should have.

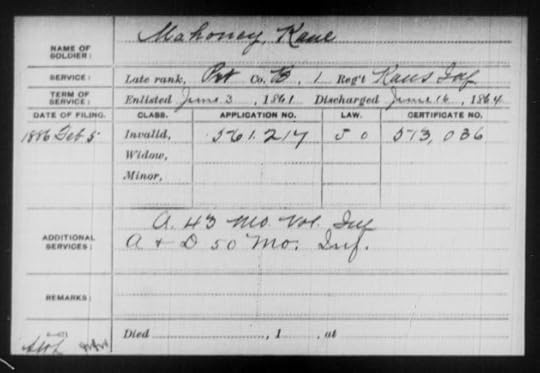

Aside from highlighting the often intricate network of individuals on which family communications relied, the letter also provides further evidence of how the American Civil War impacted Ireland. It was through the letter home of Kean [Cian] Mahony, a native of nearby Valentia Island, that news of John’s death reached Kerry. When one considers that both men were serving in a non-ethnic Irish unit, organised far beyond the densely Irish-populated hubs of the east, it gives a measure of how familiar both emigration and the war were to people in this part of the country, and how keenly the loss of those who died was felt there. The letter also has a fascinating reference to a premonition of misfortune that Daniel Clifford experienced, in a dream where the ghost of Mary’s father appeared “in great grief.” (7)

Caherciveen Nov 8th 1863

Dear Mary,

The pleasure which we experienced on receiving your welcome letter of the 1st last is beyond my power to describe.

I hope you will hold me excused when I state the circumstances under which I have incurred so much of your blame. The letter which you sent John Bourke for Cathy Coffey was missed by him in consequence of him not knowing who Cathy Coffey was but on further enquiry after the lapse of a fortnight’s he on discovering who Miss Coffey was gave her the letter which you ordered to be transmitted to her. We had afterwards some delay in getting it from her after she examining its details, so that the result proved that you were after sailing before we got any account of your letter. The only means we had to appeal to in order to respond to your calling was to enclose a note to you in a letter which was sent to Dan Shea by his brother Larry, we having placed implicite confidence in him to execute the desired duty was utterly disappointed at finding that he did not enclose the note in his brother’s letter.

I intended to let you know several things in this letter but the grief with which I am overburdened on hearing of John Shea’s death causes me to remain silent for the present a comrade of John Shea’s a young man named Kean Mahony of Valentia mentions in a letter that he died about a month ago. He also states that he sent 30 dollars to his mother, and he says that there are about 30 dollars more of his money on another man’s hand, which he says will soon be sent to here. This Kean Mahony’s address is

Kean Mahony, First Regiment

Kansas Vol Co. B

via Mimphis Tennisee

United States

Write immediately to Kean Mahony and if you get no satisfactory account from him write soon to me and let me know all about it. There were £8 came to a woman named Mary Shea in the top of the street of Caherciveen but there was no writing[?] came with it but we claimed it as being sent to Mary Shea my sister in law.

We have not words sufficient to express our grief on this melancholy occasion.

About a month ago I was forewarned by a dream I had about your father that there was something the matter. He appeared to me as it were in great grief. The only inference I drew therefrom was that your mother was dead or that there was something the matter.

Our friend Dan Sullivan John Sullivan’s son of Garranebawn died about 2 months ago you would not easily conceive the sadness which was caused by his death

We all join in sending you all our best love and blessing which we have at all times manifested and with which we shall ever remain dear Mary

You affectionate friend and cousin

Daniel Clifford. (8)

Cian Mahony of Valentia Island survived his service, which also included stints in the 43rd and 50th Missouri Infantry. He went on to claim a pension based on his time in the army. (Fold3/NARA)

The letters of John Shea and Daniel Clifford are a fine example of what such correspondence can tell us abut the networks of communication that Irish emigrants maintained with different members of their extended families, both in Ireland and America. They also offer a range of brief insights into other aspects of the Irish emigrant experience, from chain migration, to religion, to superstition. As it would appear from subsequent events, John’s death had a major impact on his mother and sister, both of whom ultimately left Kerry for the United States. I hope in the future to bring many of these pension files letters together for a major analytical study of their content, to discover what more they can teach us about the Irish emigrant experience in the 19th century.

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) John Shea Pension File; (2) Ibid. (3) Ibid. (4) Ibid. (5) Ibid. (6) Ibid. (7) Ibid. (8) Ibid.

References

Dependent Mother’s Pension File for John Shea, WC 15721.

Filed under: Kansas, Kerry Tagged: 1st Kansas Infantry, Caherciveen Emigrants, Irish American Civil War, Irish Emigrant Letters, Irish in Kansas, Kerry & America, Kerry Emigrants, Valentia Emigrants

April 3, 2016

“A Few Spoke Nothing But Gaelic”: In Search of the Irish Language in the American Civil War

In Philadelphia on 13th February 1868, Owen Curren and Mary Curren gave an affidvait relating to the case of Farrigle Gallagher. Gallagher, a member of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, had died a Prisoner of War at Andersonville. His wife Anne survived him by less than 6 months, dying– likely of T.B.– in December 1864. The Currens were giving evidence in 1868 in an effort to secure a pension on behalf of the Gallagher’s three minor children. However, the Pensions Bureau were concerned that this “Farrigle” Gallagher was not the same man as the “Frederick” Gallagher of Philadelphia they had recorded. The Currens, who had been acquainted with Farrigle for 25 and 30 years respectively, explained the reason behind the confusion:

That Frederick and Farrigle are the one and the same person. That in Ireland, where the said soldier was born and raised, he was called Farrigle which is the same as Frederick. That deceased was born in the County Donegal Ireland and that deponents lived in the same neighborhood with him and that deceased was called by his parents Farrigle. That they were acquainted with the deceased soldier in this country and heard him called Frederick, which (in the language spoken by his parents and inhabitants of the part of Ireland in which he was born) is the same as Farrigle. (1)

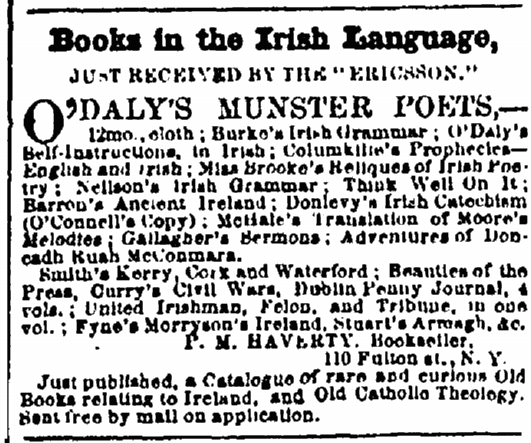

Advertisement for Books in the Irish Language, New York Irish-American Weekly, 29th August 1857. Evidence that there was demand among members of the Irish community in the United States for writings in their native-tongue in the immediate Antebellum era (GenealogyBank).

Accepting this explanation, the Pension Bureau approved the claim, noting that “Testimony of witnesses show identity of “Frederick” + “Farrigle” names are same in Irish language.” Despite having spent a number of years looking through the Widow’s Pension Files of Irish-American soldiers, this is the only direct reference to the Irish language I have yet come across, despite the fact that many of them must have been native speakers. Hundreds of thousands of those Irish who emigrated following the Great Famine had Irish, not English, as their first language. Kerby Miller estimates that anything up to 27% of Irish emigrants to the United States between 1851 and 1855 spoke Gaelic– over 200,000 people. On the eve of the American Civil War, New York alone may have been home to anything up to 73,000 native Irish speakers. As the vast majority of these people were illiterate and among the poorest members of society, they left behind very little trace in the historical record. Despite this, there seems little doubt that some thousands of those Irish who donned uniform during the Civil War were Irish speakers, and among them were those for whom English was at best poorly understood. (2)

The strength of the Irish language in certain enclaves like New York is evidenced by stories like that of P.J. Kenedy, an American-born member of the Irish community. He was born in 1842 on Mott Street in the Five Points, but despite the fact that he had never been to Ireland, Irish was the language of his home, and he learned it by the fireside with his parents in the heart of Manhattan. In 1857 the literate Irish-speakers of New York received a major boon, when the New York Irish-American Weekly newspaper secured “Irish type” for the first time, specially made in a New York foundry:

Our Irish Type

We have just received, from the celebrated type foundry of Messrs. Conner & Sons, the font of IRISH TYPE which we ordered some time since to be cast specially for this paper…The face of the letter is the same as adopted by the Irish Archaeological Society for their publications; and it has been cast in a manner that reflects much credit on the eminent firm to whom the order was entrusted. (3)

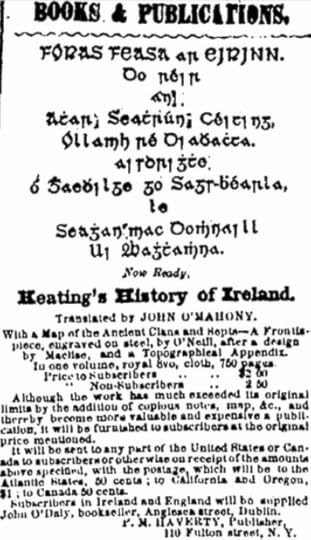

An advertisement for John O’Mahony’s translation of Keating’s History of Ireland from the New York Irish-American on 29th August 1857, the first year in which Gaelic typescript was used in an American newspaper (GenealogyBank).

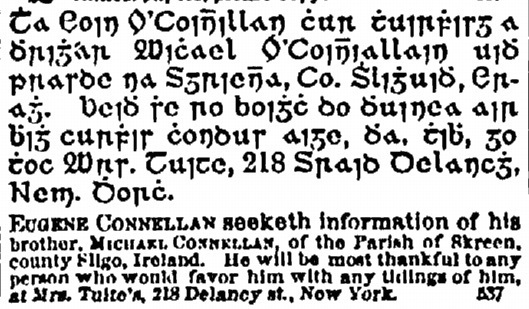

This type allowed the Irish-American to produce articles in Irish script, and they also began a long-standing series aimed at teaching interested readers the language. Much of what was written came from well known figures such as Michael Doheny and John O’Mahony, and their promotion of the language was often closely tied to their wider political goals with respect to Irish independence. Though much of the Irish language content that appeared in the Irish-American during the war years may not have been aimed at the “ordinary” Irish speaker, there is evidence that such people did make use of it. An “Information Wanted” advertisement of 28th February 1863 seeking news of Eugene Connellan, from Skreen, Co. Sligo, was printed in both English and Irish, suggesting not only that the Connellans were native speakers, but also that there were those in the city who preferred (or found it easier?) to communicate through Irish. This strong Irish-speaking community was apparently still going strong in 1865 when the Irish-American advertised a “Lecture in the Irish Language” to take place in the Church of the Transfiguration in Five Points, on the topic of the “Infallibility of the Church.” They confidently asserted that “the Irish-speaking population of this city is large; and an opportunity like the present is seldom afforded of hearing a sermon in our native tongue…” (4)

The bilingual “Information Wanted” advertisement seeking details of Eugene Connellan (Eoin O’Coińillan) from Sligo. New York Irish-American Weekly, 28th February 1863. Evidence that many of the ordinary New York Irish preferred to communicate in their native tongue (GenealogyBank).

Though there is evidence for Gaelic among the communities from which Irish soldiers were drawn, direct references to them speaking it during the conflict itself are comparatively rare. That at least some did so was attested by William O’Grady, a former British army officer and subsequently a member of the 88th New York Infantry, Irish Brigade. In describing the make up of the 88th, he remarked that:

It may be mentioned that the regiment was practically as alien as the old Irish Brigade in the French Service, comparatively few being citizens [of the United States] by birth. Fully a third were old British soldiers, many of whom had seen service in the Crimean War and the Indian mutiny. One private had been a British officer, and a few spoke nothing but Gaelic when they enlisted from the very gates of Castle Garden. (5)

The fact that at least some of the Irish officers who fought in the conflict could speak Irish was demonstrated by Kenneth E. Nilsen in his analysis of the Irish language in New York. He quotes from an 1878 letter written by David O’Keeffe, describing the demise of the New York branch of the Irish literary Ossianic Society, many of whom were Irish speakers:

In the Fall of 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected, the South seceded; Mr. O’Mahony [John O’Mahony] went to Ireland…Nearly all our members went to the war, and many never came back. As a matter of course, our society got broken up… (6)

Captain Thomas David Norris, 170th New York Infantry, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, and veteran of the 69th New York State Militia at the First Battle of Bull Run. Perhaps the most major advocate of the Irish language to serve during the American Civil War (New York State Military Museum).

Whereas the ordinary native-Irish speaking soldier of the American Civil War remains elusive, that is not the case with perhaps the most notable Irish-speaker to serve during the conflict. Thomas D. Norris was born near Killarney, Co. Kerry in 1827, and reportedly emigrated to the United States around 1851. A member of the 69th New York State Militia, he fought with them at First Bull Run (see his letter on that engagement at Bull Runnings here), and like may others of that regiment he elected to wait until Michael Corcoran’s release from Confederate prison before re-enlisting for service in Corcoran’s Irish Legion. He enrolled in the 170th New York Infantry on 28th January 1862, becoming a Lieutenant in Company H, a formation which he had helped to raise. He became Captain of that company on 1st February 1863, was wounded at Petersburg on 16th June 1864, and was discharged from the service on 22nd May 1865. After the war he stayed active in veteran’s affairs, being a member of the Mansfield Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. Immediately after the conflict he opened a Saloon at 362 Cherry Street in New York, but afterwards went to work with the Bonded Warehouse in the city. Of all his accomplishments, Norris was best known for his skills with the Irish language; the Irish-American described how he was:

…one of the most enthusiastic advocates of the Irish language renaisance, and was prominent in the starting of the Bowery Irish Language School of New York. His contributions in the old language, have been, for many years, familiar to our readers, since the starting of the “Gaelic Department,” in the IRISH-AMERICAN, in 1857. The action of our people, here, in this direction, compelled the Irish scholars, at home, to take the steps that led to the establishment of the “Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language;” and in the attainment of that result Captain Norris,– by his writings and his generous personal contributions, financially and otherwise, – was one of the leading efficients. (7)

Cherry Street, Manhattan, as it appears today. In 1865 Thomas Norris opened a Saloon here, presumably a location where hearing the Irish language spoken was commonplace.

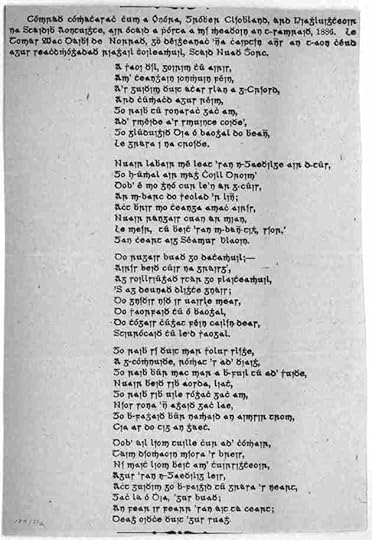

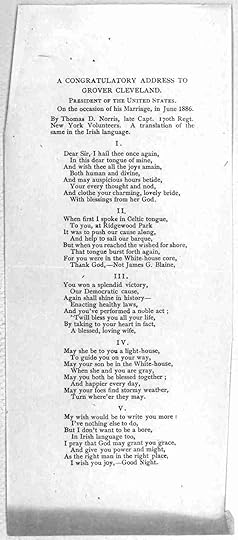

Norris, who “taught the Irish language whenever he could,” was a prominent voice in many Irish publications in the latter part of the 19th century, particularly with respect to the promotion of his native tongue. Many of his writings addressed issues such as the appropriate grammar to be utilised when speaking or writing as-Gaeilge. Perhaps the most remarkable is the address that Norris wrote for Democratic President Grover Cleveland. Norris presented it to the President in person at The White House on 6th March 1885, the day following his inauguration. It demonstrated, according to the Irish-American, how “the Old Tongue of the Gael” was being kept “in the front of the march of nations.” When President Cleveland was married in 1886, Norris again took up his pen to write a congratulatory address in Irish, which survives as a broadside. (8)

The address presented by Captain Norris to President Cleveland at The White House on the day following his inauguration. Reproduced in the New York Irish-American on 21st March 1885 (GenealogyBank).

Thomas D. Norris passed away in Brooklyn in January 1900, and was buried in Calvary Cemetery. The extent to which he used his language skills during the course of the American Civil War is a matter of conjecture, but he surely commanded a number of men who were native speakers, and with whom it would have been natural for him to converse with in Irish. Despite the paucity of evidence, the sheer number of native speakers present in the United States in 1861 means there can be little doubt that Irish was heard on many of the battlefields of the war, from Gettysburg to Chickamauga. Indeed it was perhaps in the red-hot heat of battle that one was most likely to hear Irish, as native speakers fell back on their native tongue during times of great stress. For some it may have been the last language to emanate from their lips. I am interested to hear from readers who may have come across other references to the use of Irish during the Civil War, if you have, please feel free to share them with us in the comments section. (9)

The broadside prepared by Captain Norris for President Cleveland on the occasion of his wedding (Library of Congress)

The English translation of Captain Norris’s address on the occasion of President Cleveland’s marriage (Library of Congress)

(1) Gallagher Pension File; (2) Miller 1985, 580; Nilsen 1996, 254; (3) Nilsen 1996, 258; New York Irish-American 18th July 1857; (4) Nilsen 1996, 263; New York Irish-American 28th February 1863; New York Irish-American 22nd April 1865; (5) O’Grady 1902, 511; (6) Nilsen 1996, 265; (7) New York Irish-American 20th January 1900; New York Irish World 27th January 1900; New York Irish American 19th August 1865; 170th New York Roster; (8) New York Irish World 27th January 1900, New York Irish-American 4th February 1888; New York Irish-American 21st March 1885; Library of Congress American Memory: Congratulatory Address to Grover Cleveland; (9) New York Irish-American 20th January 1900; New York Irish World 27th January 1900.

References

Dependent Children’s Pension File of Farrigle Gallagher, 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Company B, WC109448.

New York Irish American Weekly.

New York Irish World.

Roster of the 170th New York Infantry.

A Congratulatory Address to Grover Cleveland President of the United States. On the occasion of his marriage, in June, 1886, By Thomas D. Norris, late Capt. 170th Regt. New York Volunteers. Library of Congress Printed Ephemera Collection, Portfolio 129, Folder 31.

Miller, Kerby A. 1985. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America.

Nilsen, Kenneth E. 1996. “The Irish Language in New York, 1850-1900” in Ronald H. Bayor & Timothy J. Meagher (eds.) The New York Irish, 252-274.

O’Grady, W.L.D. 1902. “88th Regiment Infantry” in New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga, Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, Volume 2, 510-516.

New York State Military Museum Carte de Visite for Captain Thomas Norris.

Filed under: 170th New York, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Discussion and Debate, Kerry, New York Tagged: 19th Century Irish Speakers, Foreign Language in the Civil War, Gaelic Irish in America, Irish American Civil War, Irish Language in America, Irish Language in New York, Kerry in America, New York Irish American Weekly

April 2, 2016

War Prices! War Prices! Advertisements Aimed at Irish Soldiers & their Families from the American Civil War

We live in an age of seemingly incessant and increasingly intrusive advertising. In a world where algorithms monitor our online browsing to offer us individually tailored ads, it is easy to consider opportunistic advertisement as a relatively modern phenomenon. Of course that is not necessarily the case. A review of advertisements from periods like the 1860s demonstrates just how clued in those creating them were to the needs and concerns of their target audience. I decided to take a look at a number of ads aimed specifically at Irish soldiers and their families during the war, largely from the New York Irish-American Weekly. In them we find everything from the practicalities of how to get packages to and from the front to where you could buy presents for the soldier in your life. The 1860s equivalent of “celebrity culture” is represented in the sale of images and memoirs of and by the most popular members of Irish-American society. For the families of those who never came home, solicitors were on hand to offer their services, some with specific reference to recent bloody engagements. Meanwhile, and perhaps most insidiously, the medicine salesmen pulled at the heartstrings of those whose loved ones’ were still alive, by offering remedies for every conceivable ailment connected with military service.

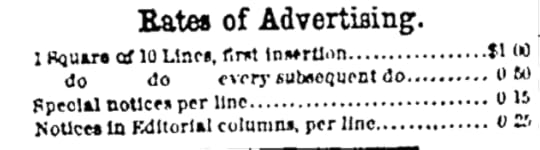

In the 1860s, as now, advertisement was a major source of finance for many newspapers. Each issue of the New York Irish-American Weekly contained large numbers of them, many specifically targeting the Irish community. This ad lists the paper’s advertising rates as published on 8th March 1862.

Shipping to the Front

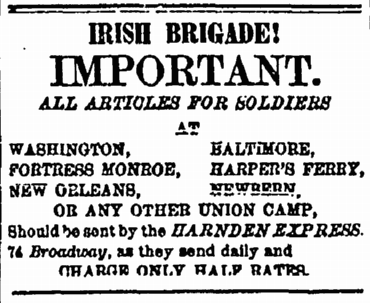

Getting money and packages safely to and from the front was a major consideration of practically every soldier in the service. In this Harnden Express advertisement from the New York Irish-American Weekly of 9th May 1863, those with family in the Irish Brigade were specifically targeted.

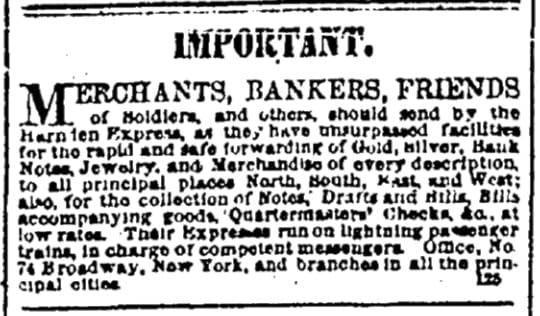

Another Harnden Express Advertisement, showing the main articles they were willing to transport. New York Irish-American Weekly, 9th April 1862.

The Adams’ Express were unrivalled in their role of getting material to and from the Army of the Potomac, and are mentioned in hundreds of Irish-American letters. This advertisement ran in the New York Irish-American Weekly of 31st January 1863, a few weeks after the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Food, Clothing & Accoutrements

Food, clothing and accoutrements were often the subject of ads. This is a section of an advertisement for Tiffany’s, run in the New York Irish-American Weekly on 3rd January 1863, highlighting their “Military Departmen” where there were many potential “gifts for the Union Soldier.”

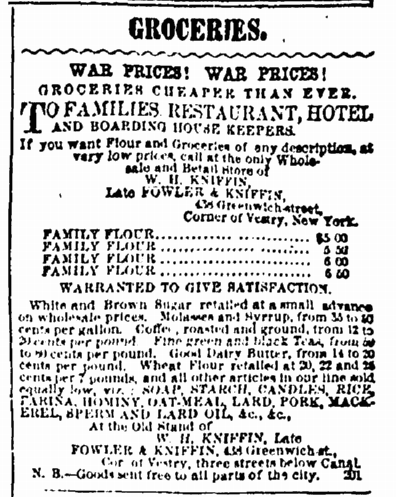

Advertisement for Fowler & Griffin of Greenwich Street, highlighting their War Prices for groceries. Advertisement run in the New York Irish-American Weekly, 5th July 1862.

Advertisement for Benedict Brothers of Broadway, suggesting that soldiers provide themselves with an “American Watch” before returning home. Advertisement from the New York Irish-American Weekly, 29th June 1865.

Publications

The concept of commemorative posters or pull-outs was alive and well in the 19th century, and appealing to the celebrity of Irish leaders was big business. This advertisement of an upcoming portrait of Michael Corcoran in the New York Illustrated News ran in the New York Irish-American Weekly on 23rd August 1862.

General Corcoran’s popularity was an opportunity to make money, particularly given the increase in his fame following his capture at First Bull Run and subsequent imprisonment. Following his release, his account of his time in Southern prison was in huge demand. Advertisement from the New York Irish-American Weekly on 18th July 1863.

This publication targeted both soldiers and those at home who wanted to read accounts of the late battles of the war. It also appeals to the strong support for General McClellan among the Irish-American community by highlighting that each copy contained an “autograph letter” from him. Advertisement from the New York Irish-American Weekly of 9th May 1863.

Death & Entitlements

From the summer of 1862 onwards both disabled veterans and the widows and dependents of deceased soldiers became eligible for U.S. pensions. In addition family often needed to access back-pay and bounties to which they were entitled. This became major business for solicitors, who took to running advertisements offering their services to the bereaved. This ad for R.S. Davis of Louisiana Avenue was specifically targeting Irish New Yorkers who had lost loved ones at the Second Battle of Bull Run, fought a few weeks previously. New York Irish-American Weekly, 22nd November 1862.

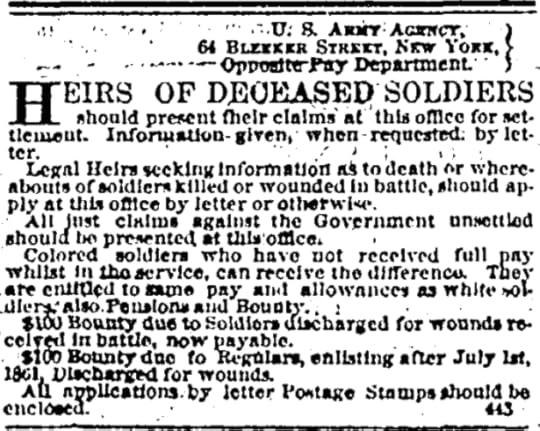

The U.S. Army Agency at 64 Bleeker Street must have been a busy place. This advertisement from the New York Irish-American Weekly of 20th August 1864 instructed people how they could go about lodging their claims.

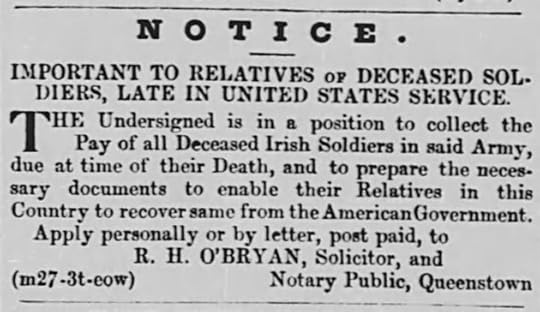

The entitlement to pensions based on Civil War service was not restricted to the Irish in America. There were also opportunities for the legal profession in Ireland as a result of the war. This advertisement for R.H. O’Bryan of Queenstown (now Cobh) in Co. Cork is testament to the number of families in Ireland who lost loved ones during the conflict. The Waterford News, 24th April 1863.

Medicines

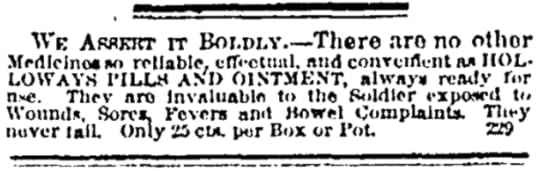

Throughout the war all sorts of remedies were offered for the assistance of soldier’s at the front. The majority almost certainly provided little benefit. A popular ad targeting not only the soldier’s but their loved ones at home was for Loway’s Pills, which offered to stave of the impact of sickness in the army. This advertisement ran in the New York Irish-American on 31st May 1862.

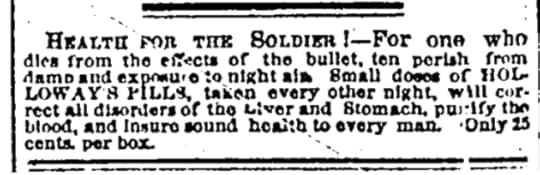

Another advertisement expounds the benefits of Loway’s Pills for the troops, this time from the New York Irish-American of 18th July 1863.

A rival to Loway’s was “Radway’s Ready Relief.” This ad from the New York Irish-American Weekly of 4th April 1863 was specifically targeting those with “friends in the army” so that they might buy their product and thus “protect soldiers against sickness.”

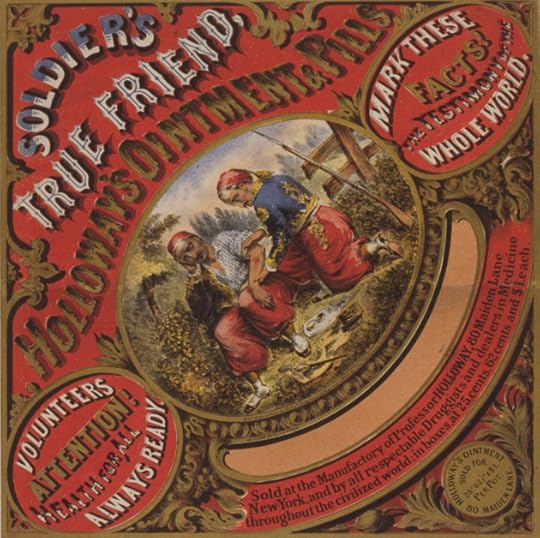

Holloway’s- Masters of Advertising

Off all the remedies on offer during this period, none rivalled the success of Holloway’s. The company, established in Britain by Thomas Holloway, became famous for driving their sales through advertisement and endorsements. Holloway himself became an extremely wealthy man as a result (money he bequeathed in his will led to the establishment of Royal Holloway College in London). They ran dozens of advertisements through the war in newspapers like the New York Irish-American, offering their product as a cure for every imaginable soldierly-related ailment. This from the Irish-American of 31st October 1863.

Off all the remedies on offer during this period, none rivalled the success of Holloway’s. The company, established in Britain by Thomas Holloway, became famous for driving their sales through advertisement and endorsements. Holloway himself became an extremely wealthy man as a result (money he bequeathed in his will led to the establishment of Royal Holloway College in London). They ran dozens of advertisements through the war in newspapers like the New York Irish-American, offering their product as a cure for every imaginable soldierly-related ailment. This from the Irish-American of 31st October 1863.

, Civil War Advertisements, Civil War Medicine, Holloway's Pills, Irish American Civil War, New York Irish, New York Irish American Weekly

, Civil War Advertisements, Civil War Medicine, Holloway's Pills, Irish American Civil War, New York Irish, New York Irish American Weekly

March 19, 2016

A Song For Mother: Last Letters of A 16-Year-Old Wisconsin Irish Immigrant

Some Irish soldiers of the American Civil War were little more than boys. Despite their youth, they often fervently supported the cause for which they fought. Timothy Dougherty was one such emigrant soldier. His antebellum family story is one of hardship and hard work– typical of that of many Irish immigrants in America. During the war, he took the opportunity of his final letters home to display his fervent belief in the war effort, not only in words, but also in lyrics.

Not all Federal soldiers spent their service fighting Confederates. Timothy Dougherty was sent west, to Kansas and Missouri, where he spent more time encountering hostile Native Americans than Rebels. Nevertheless, Timothy was a believer in the cause of Union. Though his adoptive state of Wisconsin had witnessed significant wartime disturbances in opposition to the draft, Timothy clearly had little time for those who opposed the conflict, as his letters reveal. He had grown into a young man during the early war years, and had sought to enlist while still little more than a boy– he was only 16-years-old when his mother (then only 33 herself) had given her consent to his enlistment in 1864. (1)

Milwaukee in the 1850s, as the Doughertys would have known it (Library of Congress)

Timothy was the eldest child of Denis and Catharine Dougherty. The family had emigrated to the United States around 1854; Denis and Catharine arrived in America with three sons in tow– Timothy, John and Jeremiah (Jerry). They initially settled in New York, where a fourth child, Margaret, was born. It was not long before they followed the well-worn path of many Irish immigrants and headed west. The family set out for Wisconsin around 1857, where another son, Michael, arrived. But it wasn’t long before their future well being was put in jeopardy. Denis passed away from a fever in Cairo, Illinois in November 1858, leaving Catharine to fend for their young family on her own. The 1860 Census records the 29-year-old widow living in Milwaukee’s Third Ward with Timothy (12), John (10), Jerry (7), Margaret (5) and Michael (2). A 29-year-old Irish laborer named Patrick Murphy also appears to have been living with the family at this time. Though still only a child, Timothy had to help his mother earn a living. Catharine kept two jobs to maintain her family, working as both a servant and a washerwoman. Timothy helped her with this, cutting wood and fetching water for his mother, as well as going out to collect the clothes from her patrons and returning them when she was finished. The young boy also worked various odd jobs, but by all accounts seems to have excelled as a fisherman, operating along the Milwaukee River and the shores of Lake Michigan. He used his catch not only to help feed the family, but to turn a profit at the local market when the opportunity presented itself, often earning between $1 and $3 per day. However, the extra money lasted only as long as the fishing season, and all too quickly each year the family’s earnings would once again diminish. (2)Motivated by both economics and patriotism, Timothy enlisted in the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry in late February 1864. He soon received a bounty of $200 for joining up, which he passed to his mother. Despite his enlistment, Timothy’s muster in was delayed due to illness. He came down with measles and had to be hospitalized, a situation which also meant that when Catharine came to see him before his departure she couldn’t find him, and to return home disappointed. Timothy recovered to muster in at Madison in early March, and wrote home on the 27th of the month to let Catharine know he was ok. (3)

A trooper of the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry in Fort Scott during the Civil War (Kansas Memory)

Timothy was sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas along with another young Irish recruit, Michael Cantwell. They both initially did service with Company C, but in the Autumn of 1864 they were assigned to a detachment under Captain Theodore Conkey. From there they were ordered to Fort Riley, where they formed part of the forces of Major-General James Gilpatrick Blunt, commander of the District of the Upper Arkansas. Their job was to protect settlers on the frontiers in Kansas and Southwestern Missouri from Native Americans and Confederate raiders alike, and to expel any Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers they came across. Michael Cantwell later recalled that they spent the majority of their time “engaged in fighting the Indians and protecting the settlements from their ravages.” Their isolated position meant that there was little news available on the wider war. On 17th August 1864 Timothy wrote home from Fort Scott:Dear Mother what do the peppol of the North think about this war but I think it wont be over this Summer I think I will have a chanch to reinlist after my time is out what time I have been in the army dont seam long to me. Dear Mother I would like to have you send me the Daily Scentenel [The Milwaukee Daily Sentinel] about once a week if it dont cost to much to scend it to me fore we dont here any thing about the war only whats going on in Kansas. (4)

That summer a new outpost– Fort Zarah– had been established where the Santa Fe trail crossed Walnut Creek, due to the propensity of Native American attacks there. Timothy and Michael were part of a 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry detachment sent to the Fort that autumn under the command of Captain Conkey. Typical of the actions the men were engaged in were those of early December. On the 4th of the month an ammunition wagon with a driver and four-man escort was making for Fort Zarah when they were attacked by Native American warriors at Cow Creek, some 15 miles east of the post. The men were eating supper when arrows began to rain down on them, killing the driver and wounding one of the escorts. Timothy may well have been a member of one of the two parties that Captain Conkey later sent from Fort Zarah to recover what was left of the ammunition, much of which had by then been taken. Despite their position in hostile territory, ordinary life went on. Shortly after the Cow Creek incident Captain Conkey received a letter from an upset Catharine back in Milwaukee, who was worried that Timothy wasn’t writing home. His officer wrote back on 12th December:

…Your son Timothy Dougherty is with me, doing duty at this Post– I have lectured him severely for not writing to his mother oftener. He says he has written frequently and thinks the letters must have miscarried– Timothy is well and a good boy, he makes a fine soldier– I shall try to persuade him to send his money all home to his mother when he is paid off. (5)

The Santa Fe Trail. Timothy and the men at Fort Zarah were responsible for defending a portion of it (National Park Service via Wikipedia)

Perhaps chastened by the rebuke from home, Timothy did write to his mother from Fort Zarah on 19th December. He described the post as a:…Camp out on the plaines on a little stream call the Walnut creak…we live in little houses in the bank cover over with poles and durt and a fireplace in it. We are not truble anything but indian[s] we are not truble much… (6)

Despite the fact that he was spending most of his time in frontier operations against Native Americans, the young emigrant had no doubt why he was fighting. He had strong opinions about the anti-war Democrats (Copperheads) back in Wisconsin, and what he would do to any he met who might cause him trouble when he went home:

…we are now expecting to go home this Winter the Coperhead[s] might as well be in hell as to abuse the soldiers whin will they go home this Winter for I am going [to] cary a pair of revovers [revolvers] home with me this Winter…have you heard anything about going home this Winter but we are [illegible] to see home once more before we die… (7)

Perhaps the most intriguing element of Timothy’s letter home is the song lyrics he included for his mother, presumably because it was popular among the troops at Fort Zarah. With the brief introduction “hear is song”, the soldier went straight into relating the verses:

So let the cannons boom as they will

We’ll be gay and happy still

Gay and happy gay and happy

We’ll be gay and happy still

Friends at home be gay and happy

Never blush to speak our name

Should our comrades fall in battle

They shall share A soldiers fame

Girls at home be gay and happy

Show that you have womans pride

Never wed A homesick coward

Wait and be a soldiers bride

Chorus

gay and happy sweet they answer

None but fools get married now

valliant men have all enlisted

unto cowards we’ll not bow

We’re the girls thats gay and happy

Waiting for the end of strife

Sooner share a soldiers rations

Than to live a cowards wife

For the gay and soldiers

We’re contented as the dove

But the man who dare not soldier

Never can obtain our love

Chorus

So let the conscripts woe[?] ar they

We’ll be free and happy still

Free and happy free and happy

We’ll be free and happy still (8)

Part of the original letter by Timothy to his mother from Fort Zarah, with the verses of the song separated by lines (Fold3/National Archives)

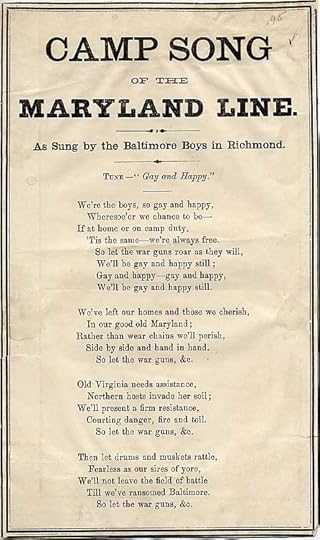

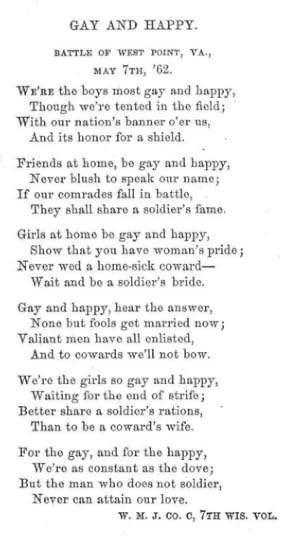

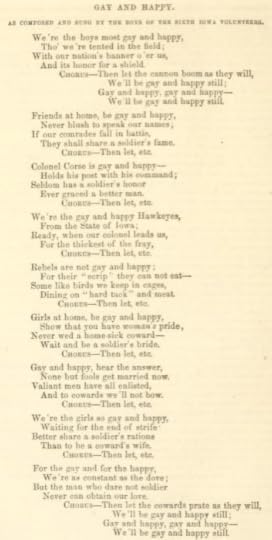

This is the first full song I have come across in my research into the pension file letters of Irish soldiers. It is a version of the wartime song Gay and Happy, which is generally credited to Anne Rush, “The Philadelphia Vocalist.” Various versions sprang up, both North and South; among the notable Southern efforts was the Camp Song of the Maryland Line. But by far the closest versions to Timothy’s I was able to locate are associated with troops from Wisconsin and Iowa. The 1864 publication Poetical Pen-Pictures of the War: Selected from Our Union Poets includes a variation of Gay and Happy that is broadly similar to that given by Timothy, and had been submitted by “W.M.J.” of Company C, 7th Wisconsin Infantry. It was ascribed to the Battle of West Point, Virginia on 7th May 1862. The Times of the Rebellion in the West: A Collection of Miscellanies published in 1867 also contains a close variant, and one that was popular among the 6th Iowa Infantry. The song resonated with some veterans for many decades after the conflict. A Union veteran in Florida quoted the third verse [“Never wed a homesick coward”] in a piece to The National Tribune in 1910, noting that it was “a verse ‘our girls we left behind us’ used to repeat when we were in the army, and they have made good.” The same verse was also quoted in the Chicago Daily Herald in 1924, again with reference to women singing it as soldiers marched off to war. (9)Original Gay and Happy Lyrics (Levy Sheet Music Collection)

Camp Song of the Maryland Line, a Confederate adaption of Gay and Happy (ZSR Library)

7th Wisconsin Infantry version of Gay and Happy (Poetical Pen-Pictures of the War)

6th Iowa Infantry version of Gay and Happy (The Times of the Rebellion in the West)

Passing on the song was the last correspondence Timothy Dougherty ever had with his mother. That January Captain Conkey and his men were ordered to make the long journey back to Lawrence, Kansas. The officer remembered the weather as cold, rainy and snowy. The cold and exposure caused a “violent fever” to take hold of the boy by the time of their arrival, and he was admitted to the Post Hospital at Lawrence on 11th February. Timothy was suffering from pneumonia, and it took his life on 13th February 1865. He was at most 17-years-old. (10)A lack of proof of her marriage delayed Catharine’s pension for a number of years, but the payments were eventually approved in 1868. By then Catharine must surely have been in desperate need of them. Described as very poor and “living in a rented shanty”, her eldest surviving child John had left for Tennessee and had not been heard from since– Catharine suspected he may have been dead. Her other Irish-born son, Jerry, was unable to work as he was a “chronic invalid.” She would receive payments based on her boy’s service until her own death in July 1893 at Plover, Wisconsin. (11)

(1) Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid., 1860 Census. (3) Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (4) Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File, 1860 Census, Nye 1968:15; (5) Nye 1968:12, Michno 2003:160, Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (6) Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (7) Ibid.; (8) Ibid.; (9) Levy Sheet Music Collection, ZSR Library Hayward 1864: 264, Howe 1867: 208, The National Tribune 3rd February 1910, The Daily Herald 30th May 1924; (10) Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (11) Ibid.;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

Timothy Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC115555.

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

The National Tribune 3rd February 1910. Glad of St. Cloud.

The Daily Herald 30th May 1924. Observer’s Notes.

Hayward, J Henry 1864. Poetical Pen-Pictures of the War: Selected from Our Union Poets.

Howe, Henry 1867. The Times of the Rebellion in the West: A Collection of Miscellanies.

Michno, Gregory F. 2003. Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes, 1850-1890.

Nye, Wilbur Sturtevant 1968. Plains Indian Raiders: The Final Phases of Warfare from The Arkansas to The Red River.

John Hopkins. Levy Sheet Music Collection. Gay and Happy.

ZSR Library. Camp Song of the Maryland Line.

Filed under: Wisconsin Tagged: 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry, Civil War in Kansas, Fort Zarah, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Milwaukee, Irish in the West, Irish in Wisconsin

March 17, 2016