Damian Shiels's Blog, page 35

August 27, 2015

Tired of the Killing of Men: An Irish Family’s Story of Assisted Emigration, Missing Children & Letters Under Fire

The nature of the Widow’s and Dependent’s Pension Files means that the stories they tell are most usually ones of sorrow. The experiences they relate generally pertain specifically to the Civil War, but on occasions the information within them can be combined with a range of other sources to provide a much wider picture of one family’s 19th century emigrant experience. The file relating to the Carr family is a remarkable case in point, charting as it does their journey from poverty in Ulster to a life of hardship and separation in 1850s New York. It is a story that continues into the American Civil War, as an Irish soldier fights not only to reunite the Union, but also for the right to be reunited with his family. It then carries into the post-war period, as the family tried to forge a new life in the ‘Gateway to the West.’ If you read no other part of this post, read the transcribed letter dated 20th June 1864. Written under fire in Georgia, it is a striking expression of weariness– and hope– imparting something of what it must have been like to have endured the horrors of the Atlanta Campaign.

On 18th August 1860 the following advertisement ran in the ‘Information Wanted’ section of the Boston Pilot:

INFORMATION WANTED OF BERNARD (or Barney) CARR, who left Ireland and landed in New York in 1851, with his mother and her children. Being unable to support them she was obliged to send three of the boys to Ward’s Island, from which place a person named Fenton Goss, from New Jersey, took one of the boys (Bernard, or Barney) to West Liberty, Logan county, Ohio. The unfortunate and disconsolate mother, who is now in certain circumstances, offers a reward of $20 to any person who can give her any information of her son Bernard Carr. Address Mrs. Ann Carr, Walton, Delaware county, N.Y. (1)

Underground lodgings for the poor of New York around 1869. (Library of Congress)

There are hundreds of ads like this scattered across newspapers like the New York Irish-American and the Boston Pilot. They often provide tantalising glimpses into the hardships experienced by many Irish emigrants, but in reading them, we are often left with more questions than answers. Where in Ireland had they come from? Why had they emigrated? Was the advertisement successful? What became of them afterwards? Remarkably, in the case of Ann Carr and her son Barney, we are in a position to answer all of these questions. This has only been possible following analysis of a range of sources, and thanks to the efforts of followers of the site’s Facebook page and Twitter stream. For the first time we can give voice to the Carr family, representatives of Ireland’s poorest emigrant class, and hear from Ann and Barney in their own words.

The starting point for our investigation is an Irish place-name, phonetically transcribed in 1865 by a clerk in Hudson, New York. As he listened to Ann Carr recount details of her family’s past, the clerk did his best to capture where he thought Ann was from. This manifested itself in his notes as the word ‘Belmosgreen’, a location that does not exist in Ireland. In hope rather than expectation, I posted an image of this piece of text on the Irish in the American Civil War Facebook Page and Irish in the American Civil War Twitter Feed in order to get people’s thoughts as to what place he might have meant. Assistance flooded in, with a number of excellent suggestions as to the possible location provided– many of which were subsequently proved correct. Among those who went the extra mile to help with revealing the Carr story was Barbara Harvey Freeburn, who not only suggested a location, but actually discovered what is a likely the marriage record of Ann Carr. Thanks to Barbara and the other readers, we have a commencement point for the Carr’s journey. (2)

The Catholic Parish Registers record the marriage of Arthur Carr and Nancy Mulholland in Ballinascreen, Co. Derry on 10th November 1835. Given that Ballinascreen was the main candidate for ‘Belmosgreen’, that we know Ann’s husband was called Arthur, and that we also know that Ann was variously known as Ann or Nancy throughout her life (which was not uncommon), then there is a strong likelihood that Ballinascreen was the Carr family’s place of origin. Ann would have been around 22-years-old at the time of her marriage. The couple had at least five children prior to Arthur’s death around 1850. Although it is not known what caused Arthur’s death, what is apparent is that it left Ann and the children utterly destitute. They were so poor that they could not have contemplated passage to the United States were it not for the intervention of others. Ann later related that in 1851 ‘I and family were sent to America and our expenses paid by the local authorities in Ireland.’ The family clearly escaped penury in Ireland only to be faced with paupery in New York. The 1860 ad that Ann placed in the Boston Pilot demonstrates this, as she had been forced to place her sons in institutional care as she had been unable to afford their support. (3)

We know that Ann’s 1860 advertisement worked. By 1862 Barney, now 17-years-old, had moved from Ohio to Illinois, where he was working for William Gillis, a farmer in Embarrass, Edgar County. It was around this time that Ann re-established contact with Barney, though they had not yet been re-united face to face. The prospect of them doing so anytime soon seemed remote, particularly as by the end of 1862 Barney’s movements were no longer his own to dictate– he was now a private in the Union Army of the Cumberland. Having found himself with no money, Barney had enlisted in Paris, Illinois on 19th July and mustered into Company C of the 79th Illinois Infantry on 18th August 1862. He was variously described at this time as ‘under 18-years-of-age’ and ‘quite young.’ Nonetheless Barney seemed happy in his new role. He started to correspond with his mother, who was living with his younger brother and two sisters in the village of Walton, Delaware County, New York (there is no mention of his third brother after 1860). In one of his early letters, written in camp near Nashville, Tennessee, he asked his mother to ‘pray for me continually I hope that you and me and the rest of the folks at home…see each other once more before I die. If it is the will of God that he may spare my life to get home to embrace my mother as we haven’t seen each other for about 9 years or more.’ (4)

Chattanooga during the Civil War (Library of Congress)

Barney became a regular correspondent with the mother he had not seen in so long, and his letters reveal much about his character. Despite the fact that he had not seen his family in years, he still managed to have an argument with his younger brother John via their letters. It seems that John (around 15-years-old by 1863) thought that it was not very ‘manly’ of Barney to be sending some of his money to a friend to mind it for him. In a letter written in the Murfressboro fortifications on 31st March 1863, Barney sent some money for his mother and sisters, but raged that ‘John can do very well without any money for what he said in his letter, Sis I want you to tell him that he can keep his pen and paper and I will do the same if he thinks that it don’t look very manly to send money home to a man. I would thank him to keep his mouth shut and I will send my money how I please and if he wants to know the reason of [it] I want to have some money when I get home…’ (5)

As with other Irish soldiers whose primary motivation for enlisting appears to have been economic, Barney nonetheless displayed considerable patriotism in his writings, demonstrating that preserving the Union was a strong motivator for him. However, life’s simple pleasures were important to Barney too- and absolutely nothing seems to have been more important in this regard than tobacco, as his letter to New York from Chattanooga, Tennessee on 14th November 1863 demonstrates. It was written at a time when Union forces in Chattanooga had faced shortages in supply: ‘…Mother I want you to send me by mail one round of fine cut chewing tobacco just as soon as you can send it to me, for that is the only way I can keep from spending my money and if you don’t send me plenty of tobacco, why then you will have to send me my money to buy it [he was sending home $30] for I can’t do without the article in no shape nor form…as for tobacco you can buy me a number one quality there and not cost near so much as it would here, I have to pay $1.00 for one plug of tobacco and it won’t weigh half a pound and it is musty after I get it so that I can’t chew it.’ Barney was also in need of a new uniform cap, and wanted to avoid drawing one from the army stores: ‘send a good soldiers cap…I am out of a hat and I will have to draw from Uncle Sam or else go and pay $7.00 for a hat and I would rather send you the money…the kind of cap that I wanted a soldiers cap one that the top leans over on the bill and the bill sticks straight out.’ Just in case his mother had forgotten his sustained appeals for tobacco, Barney signed of the letter with ‘please don’t forget what I told you and send them all right along.’ (6)

On 18th November Barney wrote a letter from Chattanooga that suggests he was keen (perhaps too keen?) on word play. In describing an early morning skirmish with the Confederates he equated the whole affair to a quest for breakfast, describing artillery fire in the following terms: ‘…this morning directly after I got up our boys and the Rebels had a knock down before breakfast and I think that our fellows gave them a breakfast of hot lead, just all that they could eat for I guess they have not had very much to eat for some time and it took a good deal to fill [?] them for they are big eaters. Any how when they have not had anything to eat for some time I guess that they were a trying to get back across the river to get at our cracker boxes and our fellows are a little hungry this morning and did not like to issue rations before they got what they wanted themselves, and Mister Rebs had to stand back until Yanks got his share for they feed our bull dogs double rations of canister and grape and the Rebs could not eat that when they throwed it across to them, and I guess it was [a] good deal of trouble for them to catch them kind of crackers throwed the distance that our boys had to throw them and that distance was across the river and when they got across they were pretty well scattered and it was a little cold and the Rebels thought that their fingers might [get] cold to pick them up and concluded they had better left that alone…’ (7)

An Artillery Bombardment during the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain by Alfred Waud (Library of Congress)

Although the fighting experienced by Union and Confederate soldiers in the first years of the war was horrendous, it entered a new chapter in May 1864, when Grant’s strategy of applying sustained pressure was implemented. That summer the 79th Illinois marched with Sherman’s army in its long, painful advance towards Atlanta. The 79th took casualties at Rocky Face Ridge on 9th May, at Resaca on 14th May, at New Hope Church on 27th May and at Muddy Creek on 18th June. The Yankees had gradually been forcing the Rebels back towards Atlanta, but now they faced the Confederates most formidable defensive line yet– at Kennesaw Mountain. As the jostling for position around this daunting Confederate fortified line continued, Barney wrote the below letter to his mother on 20th June. It is a remarkable note, and is here reproduced in full. It was not only written under fire, but it expresses sentiments which demonstrate the mental toll that fighting of this nature took on the men:

Headquarters 79 Regt Ills Vols. Camp in the field in front of the enemys breastworks and they are a shooting at us all the time, this date June the 20th 1864.

Dear Parent, once more I take the pleasure [of] writing to you a few lines to let you know that I am still alive yet. As I suppose you are well aware that Shermans army has been a fighting ever since last May and that I am still in his army. So as I have not wrote to you in a good while I thought you would be uneasy about me and thought that I would write you a few and let…[the letter stops at this point, and continues as below]

Dear Mother I have had to stop writing, we are a lying on the line [of] battle and there are 12 pieces of cannons in front of us and they are a shelling the Rebs and that draws the Rebels fire and it is a horrible place to be in. Cannonballs are a flying thick around us and the shells are a screaming in the air and through the woods, cutting the timber and earth in all directions, but thank [God] Mother I am still safe and unhurt, but how long I may still remain so I can’t tell anything about that yet. God only knows how long it may last, I am sure I can’t tell anything about it now that by the grace [of] God I still live yet and am well and hearty in the bargain and I hope that when this few lines reaches you that [they] will find you all well and doing well.

Dear Mother these are hard times nothing but fighting every day and killing of men I am a getting tired of it but then I want to see them keep those Rebels a moving to Atlanta and I guess that it is the only way of putting down this Rebellion and the sooner it is down the better it is for them that lives to see it. But Mother pray for me that I may live to see it over and live to see you all, so Mother I want to see you before I die and I want to see all of the Carr family. (8)

The Illinois Monument at the Dead Angle, Kennesaw Mountain Battlefield (Damian Shiels)

Seven days after Barney wrote this letter, on 27th June 1864, Sherman ordered his men to assault the Confederate line at Kennesaw Mountain. Lieutenant-Colonel Terrence Clark of the 79th Illinois described how the regiment formed ‘in double column at half distance on the third line of battle, Capt. O. O. Bagley temporarily commanding. He advanced the regiment to the front line , when he, on account of the troops on the right falling back, was compelled to retire, losing, in commissioned officers, 1 wounded, 1 enlisted man killed, and 11 enlisted men wounded.’ The Union assault at Kennesaw ended in a bloody repulse. The following day Captain H.C. Beyls of Barney’s company sat down to compose the following letter:

Camp in Field

Near Marietta Geo

June 28 1864

Mrs Nancy Carr

Madam,

I have to report the most painful and sorrowful duty to perform, to notify you that your son Barnard Carr of my company was killed while in the discharge of his duty. On the 27th inst our brigade was ordered in connection [with] others to charge the rebel works. Many were lost– but Barnard was the only one of my company– he [was] a noble, brave and patriotic soldier never flinching from duty but always on hand ever ready to lend a hand to assist me– I sympathize deeply [with] you and his friends

I am with respect

your obedient servant

H.C. Beyls Capt–

Co “C” “79” Ill Infty (9)

Ann Carr would never be reunited with her son. Barney was ultimately interred in Marietta National Cemetery, where his body lies in Plot I, Grave 9311. Back in New York Ann was comforted by her three surviving children, Mary Jane, Ann and John. She would go on to seek a pension based on her son’s service, citing his financial support of her and the fact that her advancing age (she was around 51 years old when Barney died) meant she could not carry out as much work as she used to (she was employed in housework and washing). As additional evidence, Ann included ‘eight letters rec’d from my said son while he was in the army and which will show his feelings towards me.’ She claimed that there had been no time since she had landed from Ireland that she needed the money as much as she did now. Ann had many more years to live. Her pension request granted, in 1865 she moved to Hudson City, New York, before going west and settling in Omaha, Nebraska in 1876 with her three children. The surviving members of the Carr family would all live out their days in the Gateway to the West. Ann’s death was recorded by the Omaha World-Herald on 17th March 1898: Died. CARR– Mrs. Anna Carr, age 90 years, at the residence of her daughter, Mrs. Stephen Rice, 963 N. Twenty-fifth street. Funeral Friday, March 18, at 8.30 a.m. to St. John’s church; services at 9 a.m. She is buried near her three children in Omaha’s Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. (10)

Marietta National Cemetery (HowardSF)

*Barney’s original letters lack punctuation and have frequent mis-spelling. In addition he uses spelling common in 1860s letters (such as ‘they’ for ‘the’) which can confuse modern readers. I have added minor formatting and spelling corrections to his letters for the benefit of readers, but none of the content has been altered in any way. If you would like to read a transcript of the letter as it appears in the original please email me. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Harris et al 1989: 564 (2) Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (3) Catholic Parish Registers, Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (4) 1860 Census, Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (5) Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (6) Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File: (7) Ibid.; (8) Ibid.; (9) Official Records: 364, Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (10) Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File, Omaha World-Herald;

References & Further Reading

Barnard Carr Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC100612.

Ballianscreen Catholic Parish Register Microfilm 05764/07.

1860 Us Federal Census.

Omaha World-Herald 17th March 1898, Volume 33, Issue 168, Page 8.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 38 (Part 1). Report of Lieut. Col. Terrence Clark, Seventy-ninth Illinois Infantry.

Ruth Ann M. Harris, Donald M. Jacobs, B. Emer O’Keeffe (eds.) 1989. Searching for Missing Friends: Irish Immigrant Advertisements Placed in “The Boston Pilot 1831-1920.”

Civil War Trust Battle of Kennesaw Mountain Page.

Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park.

Filed under: Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Derry, Illinois, New York Tagged: 79th Illinois Infantry, Assisted Emigration Derry, Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Information Wanted Advertisements, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Nebraska, Letters Under Fire

August 23, 2015

Book Review: Patrick Henry Jones, Irish American, Civil War General and Gilded Age Politician

In September 2011 I had the great pleasure of meeting Mark Dunkelman and his wife Annette in Cork, Ireland. Many readers will be aware of Mark’s exceptional and inspiring work on the 154th New York Infantry, which is surely unsurpassed by any other regimental scholar of the Civil War. Mark’s incredible grasp of the history of the unit and it’s men has allowed him to repeatedly bring readers beyond purely narrative military history, exploring wider aspects of service such as motivation, morale and memory. I have personally found many of the themes elucidated by Mark highly influential in my own approach to examining the Irish experience of the conflict. To date, his publications on the 154th have included The Hardtack Regiment: An Illustrated History of the 154th Regiment New York State Volunteers (with Michael Winey), Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier: The Life, Death and Celebrity of Amos Humiston, Brothers One and All: Esprit de Corps in a Civil War Regiment, War’s Relentless Hand: Twelve Tales of Civil War Soldiers, and Marching with Sherman: Through Georgia and the Carolinas with the 154th New York. If you are interested in discovering the types of historical examination that are possible at the regimental level, then these works are a must. It was the continuation of such efforts that took Mark and Annette to Ireland in 2011. It was a visit that led to not only an extremely enjoyable night in Cork City, but has, I am pleased to say, also now resulted in another addition to Mark’s corpus on the 154th New York. This latest publication is of special significance for those interested in the Irish experience, as it has as its focus the one-time Colonel of the regiment, Westmeath man Patrick Henry Jones.

Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General and Gilded Age Politician by Mark H. Dunkelman

It is often remarked that there has been more written about the Irish experience of the American Civil War than on any other ethnic group, a statement which is undoubtedly true. However, there remains– to my mind at least– many aspects of the Irish experience that still warrant significant attention. The concentration of effort has largely been focused on military histories of the Irish Brigade, or on certain famed Irish individuals of the era, such as Thomas Francis Meagher and Patrick Cleburne. This is of course an issue that is consistently being addressed, notably by academic scholars in the United States and Britain who are widening our understanding of the Irish experience significantly. Despite this, there is much to be done. As yet (and somewhat surprisingly) we have no history of the Irish Brigade which comprehensively examines that unit’s story beyond its battlefield experiences. We have no history at all of Corcoran’s Irish Legion; little work has been carried out on the overwhelming majority of Irish who served in non-ethnic units; virtually nothing has been done on the Irish in Union Navy, where 1 in 5 Jack Tars were of Irish birth. Another area which would benefit from more attention are examinations of Irishmen who rose to senior rank. Outside of the likes of Meagher and Cleburne, such works are rare (though not wholly absent- for a comprehensive listing see the Biography section on the Books page here). For example, Michael Corcoran has never been the subject of a biography, nor has Thomas Alfred Smyth, regarded as the most effective Union Irish General of the war (though a book on Smyth is in preparation). It is in this context that Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General and Gilded Age Politician has arrived, and it is an exemplar of the potential value of such avenues of research.

Anyone familiar with Mark Dunkelman’s approach to history will not be disappointed with this book. As should be the case, the biography examines Jones’s life in full, placing the Irishman’s Civil War service in the context of his life experience. The first chapter deals with the family story around Clonmellon, Co. Westmeath, where Patrick was born on 18th November 1830, and the circumstances which led the family to emigrate to New York. It was here that Patrick would begin his long-standing connection with Cattaraugus County, a connection that ultimately led him to command of the 154th New York. But much was to happen prior to this.

Upon reaching adulthood, Patrick Henry Jones spent much of the pre-war years working as a journalist for papers such as the Cattaraugus Republican, the Buffalo Republic and the Buffalo Sentinel before eventually settling on a career in the law. On the face of things, Patrick’s ante-bellum career path provides an example of just how far an Irish emigrant could rise in the United States. However, his family experience was significantly more nuanced than this. In fact, the Jones’s faced significant Know-Nothing prejudice in 1850s Cattaraugus, which would ultimately split the family. It led Patrick’s parents and siblings to depart for new prospects in Garryowen, Iowa, an undertaking which is explored is some detail in Dunkelman’s book. In so doing, Patrick was left alone to forge his future in New York, something which he did with ever increasing success. Defying the potential handicap of his origins, he became a mainstay of his local community in Ellicottville, where he combined his professional work with an increased social profile. Then came 1861, and war.

Of the book’s 11 chapters, two are taken up with Jones’s life in Union blue. This began in 1861 as a Second Lieutenant in the Allegany Chamberlain Guards, which by happenstance would end up becoming a part of the 37th New York Infantry, the ‘Irish Rifles’, although Jones’s company was made up of Cattaraugus County men. The sometimes difficult dynamic between the Allegany soldiers and the Irishmen is a fascinating aspect of what followed; one imagines such tensions would have been trying for Jones. The Cattaraugus troops also disliked their ineffective Colonel, John McCunn, an Irishman inculcated in the corruption of Tammany Hall, and a man who one soldier described as “graceless, godless, unmitigated, forward and backward, blarneying, duplicity-dealing McCunn.” The difficulties among elements of the regiment’s leadership in the war’s early days are well assessed by Dunkelman; they would eventually lead to the demise of McCunn and his removal from command. His replacement was the competent regular Samuel Hayman, under whose tutelage Jones military career began to flourish. Patrick Henry Jones’s performance would eventually see him rise to the Colonelcy of the 154th New York Infantry in late 1862, a regiment composed of eight Cattaraugus county and two Chautauqua county companies. It was a further mark of the Irishman’s position within his local New York community. The regiment formed part of the 11th Corps, which had trying times ahead at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Jones missed the clash in Pennsylvania due to being wounded and taken prisoner on the former battlefield. When he returned to his men in late November 1863 they had moved to the Western Theater, and it was in the West during 1864 that Jones would do much sterling service commanding one of Sherman’s brigades, service which would eventually see his promotion to Brigadier-General in 1865.

Dunkelman charts the ups and downs of Jones military career in detail, but for me the most impressive aspects of this book are the chapters that follow 1865, as we discover how self-made Irishmen like Jones could seek to advance their careers in the Gilded Age political arena. Although like most Irishmen he started out as a Democrat, Jones was one of a relative minority among his countrymen who switched allegiance to the Republican party. Jones moved to New York city, and was there selected as the 1865 Republican candidate for Clerk of the Court of Appeals. Such was Jones’s popularity that many of his normally Democratic inclined fellow Irish supported him. The cut-throat political world of patronage and corruption that was the hallmark of New York politics and which Jones sought to navigate are the focus of the subsequent chapters, which effectively chart Jones rise and fall. During his political career the Westmeath native would enjoy much success, which included taking over Charles Graham Halpine’s term as Register and establishing close connections with noted men of the era, such as Horace Greeley. In 1869 President Grant demonstrated just how far Jones had come when he nominated him Postmaster of New York, a position of immense influence, particularly with respect to patronage.

The book not only seeks to demonstrate how Jones navigated the politics of the age, but in the important chapters Irishman and Veteran and Miles O’Reilly’s Halo it examines Jones position as a member of the Irish-American community of New York, as a veteran of the Civil War, and as a bridge to Irish-American support for the Republican party. As someone who for many years pinned his colours to the Republican mast, as opposed to Tammany Hall, these chapters provide a particularly useful insight for those interested in this aspect of the New York Irish experience. It is here we learn of Jones’s efforts to remember Daniel O’Connell, his public interactions with the Fenian movement, his efforts to support Irish cultural events, his support of the New York Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum, and of is role as President of the Irish-American Savings Bank. As has been discussed on this site before, the use of the Irish Brigade’s history as a mechanism for the Irish-American community to demonstrate their contribution to the Civil War and Union was a central facet of how the Irish in the north chose to remember the conflict. Despite never serving with the Brigade, Jones recognised this importance, becoming one of the incorporators of the Irish Brigade Association. These two chapters alone are worth the price of the book for anyone interested in the Irish of New York, particularly given Jones position– navigating as he did his roles as an American, an Irish-American, a Cattaraugus county man and a long-time Republican.

Throughout this book one is increasingly impressed with the character of Patrick Henry Jones, who comes across a likeable, honest and hard-working individual. The final chapters deal with Jones’s gradual embroilment in both financial setbacks and scandals, as well as the bizarre circumstances surrounding his ultimate political decline. The latter centred around his unwished for involvement in one of the most notorious crimes of Gilded-Age New York, namely the 1878 theft by grave-robbers of the body of Alexander T. Stewart, who had been an exceptionally successful Irish-American entrepreneur. A media-frenzy was created when news broke of the removal of the body. It was the misfortune of Patrick Henry Jones to be the man that the body-snatchers wrote to as they sought to receive a ransom for the return of the remains. Although clearly keen not to be involved, Jones felt duty-bound to aid in the recovery in any way he could. Unfortunately his reputation would be forever tainted as a result, with allegations that he was acting as a willing agent of the grave-robbers rather than a reluctant intermediary gaining traction. His connection to the case would dog him for the rest of his days.

Patrick Henry Jones returned to the Democratic party in 1880, but he would never again hold major political office. He maintained his law offices and eventually moved to Staten Island. His final years were characterised by ill-health, financial difficulties and an alcohol problem. A friend visiting in 1888 noted that he was “generous, kind-hearted, and gentle and brave, he was a noble and specimen of a true man– whiskey destroyed him prematurely.” Jones suffered a stroke in 1898 and ultimately died of heart failure of 23rd July 1900, leaving behind a poverty-stricken widow. It proved a sad end for a man who had achieved so much.

Mark Dunkelman’s biography of Patrick Henry Jones has helped to rescue this significant 19th century Irish-American figure from obscurity. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in the Irish-American community of New York or the Irish experience in America generally. I was honoured to be asked to read a preview copy of Mark’s book prior to publication, and to provide my thoughts on it for the dust jacket. Those thoughts succinctly demonstrate my views on the work:

“Mark H. Dunkelman’s Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General, and Gilded Age Politician is an important addition to the body of work on Irish Americans in the Civil War era. Outside of the most celebrated figures, biographies of significant Irish-born leaders who participated in the conflict are relatively sparse, making this study all the more valuable. The author expertly charts the rise and fall of Jones from his native Ireland through his life in America, as he sought to steer a path through the challenges, opportunities, and pitfalls presented to him by the Civil War and subsequently by New York City’s Gilded Age political scene. What emerges is a picture of a likeable, hard-working man, who was ultimately undone by a series of financial setbacks and an unwished-for association with a bizarre grave-robbing scandal. This book takes the reader far beyond Patrick Henry Jones the Civil War brigadier general, placing his service in the broader context of a life filled with accomplishment and, ultimately, disappointment. Dunkelman’s book is an exemplary work, demonstrating the historical dividends that the detailed biographical examination of Irish American figures such as Jones can bring.”

This is an excellent book– buy it! (you can do so here).

*I am grateful to Louisiana State University Press for providing a review copy of this book.

References

Dunkelman, Mark H. 2015. Patrick Henry Jones: Irish American, Civil War General and Gilded Age Politician. 288 pp.

Filed under: Book Review, New York, Westmeath Tagged: 154th New York Infantry, Gilded Age New York, Irish American Civil War, Irish Cattaraugus County, Irish in New York, Irish in Republican Party, Irish-American Politicans, Patrick Henry Jones

August 20, 2015

‘His Death is an Uncertainty:’ Two Irish Women Search for Missing Husbands after Second Bull Run

As I am currently on a few days leave I have been taking the opportunity to catch-up on some reading. A book I am particularly enjoying is John J. Hennessy’s Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas. I was struck by the savage intensity of much of the fighting on 29th August, 1862, when a series of un-coordinated Federal attacks against Jackson’s Confederates resulted in severe casualties. Hennessy vividly describes the see-saw fighting across the woods and unfinished railway cut on this part of the battlefield, as isolated Union assaults often met with initial success, only to be thrown violently back by determined Rebel defenders. The fighting, some of which was hand-to-hand, left large numbers of dead and wounded scattered about the field. I never read such descriptions without thinking about the impact such horrors had on individuals and their families. The confused, intensive nature of the battle on 29th August, coupled with the fact that the victorious Confederates held the field afterwards, meant that many Union men simply disappeared that day. With no corpse as proof of death, what did this mean for the families– were they dead? injured? captured? What did it mean for those in search of a pension? I decided to take a look at a couple of their stories in an effort to find out.

The fighting at Second Bull Run by Edwin Forbes (Library of Congress)

At around 3pm on 29th August, 1862, Brigadier-General Cuvier Grover led an attack towards the enemy on the Bull Run battlefield. Bursting from the woods in front of the Rebel position, his men successfully overran the railway cut, grappling for its possession in a “hand-to-hand melee with bayonets and clubbed muskets.” In so doing Grover’s brigade had driven a dangerous wedge into the Confederate line. They pressed forward, but crucially were left unsupported. The Rebels eventually counter-attacked, with blistering fire seeing “men dropped in scores, writhing and trying to crawl back, or lying immovable and stone-dead where they fell.” Despite incredible effort, after 30 minutes the press of Southern infantry finally forced Grover’s men back, exposing them to yet more galling fire. One recalled that as his regiment “recrossed the railroad bank, they were exposed to a murderous fire from each flank, to say nothing of the very bad language used by the rebels in calling upon them to stop.” One of the men who made the attack that day was Private James Moran of Company B, 11th Massachusetts Infantry. The 11th were Grover’s left-hand unit, and took 112 casualties on 29th August. Was 33-year-old Irishman James Moran one of them? (1)

Danvers currier James Moran had marched off to war a little over eight months before Second Bull Run. He had married Ellen Coughlin on 9th May 1853 at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Salem. They had three living children in August 1862; Michael (b. 22nd July 1859), Ellen (b. 14th January 1861) and James (b. 9th June 1862). James was less than 3 months old the day his father disappeared. The Irish woman knew only that her husband was gone. Her initial efforts to reveal what became of him uncovered little, as this response to one inquiry demonstrates:

Head Quarters 11th Regt. Mass Vols

Sept 13th 1862

Mrs. Moran,

I am unable to give you much information in regard to your husband James Moran. He went in to the fight, Friday Aug 29th and has not since been heard from. If I can get any information in regard to him I shall be glad to impart it to you.

Yours truly,

R.E. Jameson. (2)

Although the balance of probability suggested James Moran many be dead, without sufficient proof Ellen Moran could secure neither closure or a pension. Eventually her agent managed to contact James’s company commander Captain Walter Smith. His reply in March, 1863 seemed to confirm her worst fears:

Capt. W.N. Smith

Head Quarters Co B

11th Regt Mass Vols

March 1st 1863

Mr. A.A. Putnam

Dear Sir,

Your communication in regard to the death of Private James Moran of my company has been received & I hasten to answer it. The facts in the case are these. On the 29th of August last Private Moran with the rest of my command went into the charge on that day in which this Regt., Company, & Brigade suffered most severely. He never came out of the woods with us nor has he ever been heard of since. His death is an uncertainty and I would not wound the feelings of his family by stating such to be the fact though it is too probable. I very much fear he was reported on the list of dead for the muster and pay rolls of my company…it is more than probable then he with others were killed on that fatal day. He was a brave and willing soldier who always did his whole duty and if dead he died as a soldier & a patriot facing his country’s foes. He has been dropped from my rolls since the day of his death (supposed) ample time having been given him to report.

Yours with compassion for his family,

Walter N. Smith

Capt. 11th Mass Vols

Com’dg Co B

P.S. Anything further I can do let me know and I will do it.

W.N.S. (3)

Ellen appears to have never got any further details with respect to her husband’s final moments. He simply never re-emerged from the battlefield of Second Bull Run. Eventually the likelihood of his death was accepted, and on 24th May 1864 her widow’s pension was approved. (4)

A Soldier of the 11th Massachusetts (Library of Congress)

At around 5pm on 29th August 1862– a couple of hours after James Moran’s ordeal– another of the isolated Federal attacks that typified the day was launched under the guidance of Major-General Phil Kearny. The 101st New York Infantry of Brigadier-General David Birney’s brigade were among the troops who supported this attack. Forming in line on the left of the 40th New York, the 101st tramped towards the Rebels, with one remembering that “the ground was literally covered with dead bodies, there being one every few feet and sometimes two or three together.” Driving the Rebel skirmishers back through the woods, the New Yorkers were joined by the 4th Maine as they closed in on the railroad cut. The blueclad infantry unleashed a curtain of fire at the enemy from thirty yards out, charged, and put the enemy to flight. Victory seemed within their grasp as they pressed forward, but as before a Confederate counter-attack eventually proved decisive. After 45 minutes of fighting they had to fall back, retracing their steps over ground so dearly won. By the end of the fighting, the 40th and 101st New York between them could muster only 250 men. Irishman Edward Sweeny, who had gone into the action as a private in Company A of the 101st, was not one of them. Though it was known he had been wounded, no-one seemed to have any idea what became of him. (5)

Catherine Dwyer had been no more than 17-years-old when she married labourer and fellow Irish emigrant Edward Sweeny. He was 15 years Catherine’s senior when the couple were wed in the Catholic Church of Owego, New York on 22nd August 1851. The 1860 Census recorded them living there with their children Michael (8), Edward (4), John (2), Sarah (3 months) and Dan (3 months). Sometime between the census and the Second Battle of Bull Run baby Dan appears to have died. As with Ellen Moran, following the battle Catherine was left with the arduous task of attempting to discover her husband’s fate before she could seek financial aid for her family. Appointing an agent to assist her, their first port of call was the surgeon responsible for the records of the 101st New York, who was contacted via the Sanitary Commission. But the 101st had lost so many men by 1863 that it had to be consolidated, and so the man who wrote back on 26th March was the surgeon of the 37th New York. This is what he had to say:

Edward Sweeny is reported by his comrades and on the regimental books as wounded at the Battle of Groveton near Manassas Plains on the 29th August 1862. Said to have been wounded in the head (the missile fracturing the skull), in the wrist and body (part unknown). My information states that the surgeon who attended him on the field had no hope of his recovery. Informant also states that he saw him at the same time and place (the general depot on the field– a large farm house right in rear of the scene of the engagement) and found him very low. Further information may be offered from Dr. D.B. Van Slyke Oswego N.Y. then surgeon of the 101st Regt since mustered out with the other officers, in consequence of the consolidation with the 37 N.Y. Inf.

I am almost satisfied that Sweeny died on the field, where he was buried subsequently “without note or comment.” Records were not kept at all, I strongly suspect, owing to the lack of system & the dire confusion prevailing at the time.

As far as my own notes go, they are confined to those cases in the hospital at Centreville where I had charge of 3 or 4 wards containing about 80 sick and wounded– a list of whom I furnished at the time to Med. Inspector…also the names of those who died, as far as I could learn. Some were moribund, but in one or two instances I obtained the desired information from letters or pocket books found on their persons.

William O’Meagher

Surgeon 37 NY Rifles (6)

Despite the near certainty that Edward was dead, Catherine needed more proof is she was to get a pension. Taking O’Meagher’s advice, they wrote to Surgeon Van Slyck, though with little result:

Syracuse Apr 21st 1863

Dr Sir,

Yours of the 14th is rec’d & in reply I can only say that Sweeny was reported in the regt as dead on the field. I did not see him after the battle & have heard nothing from him since. If by any possibility he was saved & reached a hospital you can learn of it by writing to the Office of the Sanitary Commission, Washington D.C.

Yours Respectfully

D.B. Van Slyck (7)

Union soldiers find remains of their comrades on the Second Bull Run battlefield, 1863 by Edwin Forbes (Library of Congress)

Of course they had already been in touch with the sanitary commission, so the search for further information continued. 1863 came and went without resolution. By 1864 they were in touch with J.W. Egan, of the 40th New York, with whom the 101st were by then consolidated. Again their queries produced few results:

H.Q. 3rd Brigade 1st Div., 3d Corps

Camp near Brandy Station, Va.,

March 5, 1864

Dear Sir,

Enclosed please find the best certificates procurable, after thorough examination [these state only that Edward had been wounded]. Mr. Sweeny, though mortally wounded, must have died in rebel hands- no man in the 40th saw him die.

The 101st was not then consolidated with my command, & consequently I had no control over its records. It also passed through one consolidation (with the 37th N.Y.) previously, & after the Battle of Manassas.

You now require a surgeon’s certificate or that of someone who saw him die. But this is not necessary if his officers in the 101st have done their duty, and filed his “final statement” in the office of the Adjutant General.

Can you not ascertain who was his company commander in the 101st? He must live in your vicinity, & is the person to give you a certificate.

Truly yours,

J.W. Egan

Col. 40th N.Y.S.V.

Comdg Brigade (8)

Efforts now turned to tracking down Edward’s former Company commander, Captain William C. Allen, as had been suggested. But again, the sheer toll the Second Battle of Bull Run had taken on the 101st New York impeded their efforts, for Allen had himself suffered a wound on 29th August that brought an end to his military service. He wrote the following in May 1864:

63 Bleecker St

New York 28th May 1864

Owego N.Y.

Sir,

Yours of Apl 28th has just come to hand remaining in the P.O. until ad-returned. As regards Sweeny I am sorry to say I have no way of knowing anything more than that he was reported wounded & never been heard from since. I was wounded on the same day & never had command of my Company afterward, however I will try & find my former orderly & perhaps he may know something in regard to Sweeny’s fate.

Respy yours,

W.C. Allen. (9)

There is nothing more on file with respect to the search for information about Edward Sweeny’s fate. Unfortunately for Catherine, she also accidentally provided some incorrect information about one of her children’s birthdates which slowed pension approval still further. Seemingly accepting that Edward must have died and been buried on the field at Bull Run, she was eventually granted a pension in January 1865, nearly 2 and a half years after her husband’s death. The experiences of women like Catherine Sweeny and Ellen Moran demonstrate that who held the field at battle’s end often had wider ramifications than just military pride or tactical advantage. For those who had the misfortune to have “missing” husbands as a result of Federal reversals, it meant the battle would live on for many months or even years into the future, as they sought the answers needed to not only learn their loved ones fate, but also to secure their own financial security. (10)

Clara Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office, Washington DC. She helped many families learn the fate of their loved ones following the Civil War. (Photo by E.L. Malvaney)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Hennessy 1999: 251, 253-4, 256, 257, James Moran Widow’s Pension File; (2) Massachusetts AG 1931: 751, James Moran Widow’s Pension File, 1860 Census; (3) James Moran Widow’s Pension File; (4) Ibid.; (5) Hennessy 1999: 276, 277-8, 284 (6) Edward Sweeny Widow’s Pension File; (7) Ibid.; (8) Ibid.; (9) Ibid.; (10) Ibid.;

References & Further Reading

James Moran Widow’s Pension File WC23725.

Edward Sweeny Widow’s Pension File WC39109.

Hennessy, John J. 1999. Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas.

Massachusetts Adjutant General, 1931. Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War, Volume 1.

Manassas National Battlefield Park.

Civil War Trust Second Manassas Page.

Filed under: Battle of Second Bull Run, Massachusetts, New York Tagged: 101st New York Infantry, 11th Massachusetts Infantry, Civil War Widow's Pension, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Massachusetts, Irish in New York, Missing Soldiers Civil War, Second Bull Run

August 7, 2015

‘The Flag that Has Given Protection to Persecuted Countrymen’: An Irishman’s Service to Union & Parents

Perhaps one of the best known of all Irishmen to serve during the American Civil War was Buster Kilrain of the 20th Maine Infantry. Buster plays a major role in Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels, and was portrayed by actor Kevin Conway in the film Gettysburg. Kilrain, a loyal soldier and confidant of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, died of wounds received during the 20th’s famed actions on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. Of course Buster Kilrain is a fictional character– no one of that name ever served with the 20th Maine. However, real Irishmen were present in the regiment’s ranks. One of them was Tommy Welch, who like his fictional countryman was among the defenders of Little Round Top. Tommy shared other traits with Kilrain; both were among the older men in the regiment, and unfortunately both were destined not to survive the war. The pension file that was created as a result of Tommy Welch’s death reveals much about his pre-war life and circumstances. It includes a letter he wrote home– transcribed below– which not only explains one of his reasons for fighting, but also mentions the 20th Maine’s actions at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Tommy’s character is further revealed thanks to his popularity among the Maine men, which saw him remembered many years later by former comrades such as Theodore Gerrish when they sat down to record their memories of life during the American Civil War.

Buster Kilrain (Kevin Conway) engaging the Confederate on Little Round Top in Ron Maxwell’s ‘Gettysburg’ (Image: Dudster32)

It is not clear when the Welch family emigrated to North America, but they may well have travelled via Canada in the late 1830s or early 1840s. The family group consisted of Robert and Mary Welch, their son Thomas (Tommy), along with a number of other brothers and at least one sister. On the eve of the war Tommy’s parents were ageing; Mary Welch had been born around 1797, while Robert Welch celebrated his 77th birthday in 1860, having been born in 1783. Of their children, it was Tommy who bore chief responsibility for providing for them, foregoing starting a family of his own in order to see to their care. A neigbour in Bangor would later recall that his sister once asked Tommy why he had never married– he replied that he couldn’t, as his father and mother depended on him for their support. Tommy provided this support by working in the woods lumbering during the winter, and at a boom on the Nashwaak river rafting logs during the summer. A boom was a barrier placed in the river to collect timber that had been floated downstream from logging sites. This strenuous (and dangerous) livelihood saw Tommy travel some distance from Bangor; indeed he spent much of his time across the border. The Nashwaak is a Canadian river located in New Brunswick, where the town of Fredericton was home to a number of the extended Welch family. The seasonal nature of Tommy’s work creates problems that were all to common for many Irish laborers- the unpredictability of seasonal wages. While he could hope to earn $25-$30 per month on the river during the summer months, this earning potential fell away to between $15 and $20 a month during the winter. This type of uncertainty and fluctuation in income was a factor that many Irishmen would have taken into consideration when choosing whether or not to don Union blue during the 1860s. (1)

Whatever his ultimate reasons, it can’t have been an easy decision for Tommy to enlist in the Union cause. He told friends that he was going into the army in order to better support his parents, but he was also motivated by a sense of patriotism towards the Union. There is evidence for both economic and patriotic motivations in his subsequent actions, given the views he expressed to his brother in 1863 (below) and the fact that he sent at least $155 in bounty money to his parents. Nonetheless, enlistment meant travelling much further away from his parents than New Brunswick, and this must have been hard for a man so devoted to their welfare. Tommy was probably around 37 or 38 years old when he enlisted at Houlton on 6th August 1862, in what would become Company H of the 20th Maine Infantry. Within a matter of weeks he and his comrades were marching off to war, and their first encounter with the enemy. (2)

A log boom on the St. Croix River, Maine (National Archives)

The 20th Maine Infantry initially became part of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Corps of the Army of the Potomac. They arrived in time for the Battle of Antietam on 17th September 1862, but were kept in reserve and were not engaged. However, the Pine Tree State men were involved in the pursuit of Lee’s army as it made it’s way back across the Potomac. The 20th Maine crossed after them, but soon found that given the number of Rebels they faced on the other bank retreat was necessary. It was an incident that occurred during this re-crossing that remained fresh in the mind of 20th Maine veteran Theodore Gerrish’s many years later:

One very amusing incident occurred in our retreat. In Company H was a man by the name of Tommy Welch, an Irishman about forty years of age, a brave, generous-hearted fellow. He was an old bachelor, and one of those funny, neat, particular men we occasionally meet. He always looked as if he had emerged from a bandbox; and the boys used to say that he would rather sacrifice the whole army of the Potomac, than to have a spot of rust upon his rifle, or dust upon his uniform. He was always making the most laughable blunders, and was usually behind all others in obeying any command. When our regiment went tumbling down over the side of the bluff, to reach the river, the men all got down before Tommy understood what they were doing. Then very slowly he descended, picking his path carefully among the trees and rocks, and did not reach the river until the rear of the regiment was nearly one-half of the way across. The officer who commanded our regiment on that day rode a magnificent horse, and as the regiment recrossed, he sat coolly upon his horse near the Virginia shore, amidst the shots of the enemy, speaking very pleasantly to the men as they passed him. He evidently determined to be the last man of the regiment to leave the post of danger. He saw Uncle Tommy, and although the danger was very great, he kindly waited for him to cross. When the latter reached the water, with great deliberation he sat down upon a rock, and removed his shoes and stockings, and slowly packed them away in his blanket. Then his pant legs must be rolled up, so that they would not come in contact with the water; and all the time the rebels were coming nearer, and the bullets were flying more thickly. At last he was ready for an advance movement, but just as he reached the water, the luckless pant legs slipped down over his knees, and he very quietly retraced his steps to the shore, to roll them up again. This was too much for even the courtesy of the commanding officer, who becoming impatient at the protracted delay, and not relishing the sound of the lead whistling over his head, cried out in a sharp voice: “Come, come, my man, hurry up, hurry up, or we will both be shot.” Tommy looked up with that bewildered, serio-comic gravity of expression for which the Emerald Isle is so noted, and answered in the broadest brogue: “The divil a bit, sur. It is no mark of a gintleman to be in a hurry” The officer waited no longer, but putting spurs to his horse, he dashed across the river while Tommy, carrying his rifle in one hand, and holding up his pant legs in the other, followed after, the bullets flying thickly around him. Poor Tommy Welch, brave, blundering and kind, was a favorite in his company, and his comrades all mourned when he was shot down in the wilderness. He was there taken prisoner, and carried to Andersonville prison, where he died of starvation. (3)

Reunion of veterans of the 20th Maine at Gettysburg in 1889 (www.mainememory.net)

Although Gerrish’s description of the event demonstrates a stereotypical and somewhat racist characterisation of the Irish that was common at this time, it nonetheless demonstrates that there was genuine affection for ‘Uncle Tommy’ within the 20th Maine. The regiment’s first major direct experience of combat would follow a few weeks later at the Battle of Fredericksburg on 13th December 1862. The 20th Maine participated in one of the last attacks against Marye’s Heights, and were forced to stay on the field through the night in front of the Rebel position. More than a month after that battle, on 26th January 1863, Tommy wrote home to his brother Robert. Robert appears to have been in New Brunswick, which caused a delay in his letter to Tommy (to which this letter is responding) reaching the front.

Falmouth VA Jan 26 63

Dear Brother I recived your letter dated Oct 20 a few dayes ago and am glad to hear from you But think you are a little unjust in not writing to me before I have recieved but one letter from you the letter you wrote was delayed in Frederton [Fredericton, New Brunswick] about tow months If you write they [there] will be now [no] trouble but what I shall get them The postage must be paid before they can come

I was very sorry to learn of Brother B. Albert misfortune I hope he will be better in short time you must tell sister Mary to write to me as you can give her the directions I think she is a little ungratefull in not writing me before. I want you to let me now what [you] are doing this pleasant winter and the rest of my Brothers I think I can see the hills all congealed with snow while I am in the sweat suny South

But still I am not without trouble and trials but still I beare them willingly and more because the flag that [sic.] has given protection to [our] persecuted country men We are going to be paid of in a day or so and it will be quite a sum I will send it the same way I did before I am intitled to 55 dollars from the town of Houlton and in case it should be the will of God to call me from this world I oferise [authorise] you to collect it for me they are holden to pay it

[illegibile] is time I should tell you of the Battle of Fredericksburg we cross[ed] the Raperhanock the 13 Dec in the afternoon and marched doble quick into the citty and then we went upon the field and it was a bloody field I was struck with a shell we marched half a mile in front of the Rebles a rifle fire the shell struck me before we got on the field the Capt told me to go back and said I was badly hurt but I puut my trust in God and went forward (4)

Tommy’s letter indicates how his thoughts were turning to home (although there is perhaps a hint of sarcasm with respect to the weather) and also to providing for his parents. Given the horrors he must have gone through at Fredericksburg, his account of the engagement is remarkable in its matter-of-fact nature. Although the 20th Maine were not engaged at Chancellorsville, their finest moment of the war was to come later that summer. We know that Tommy was present with Company H when the 20th Maine became immortal on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. Unfortunately as indicated by Theodore Gerrish, Tommy’s luck, like that of so many others, would run out during the bloody Overland Campaign of 1864. Although Gerrish states that Tommy was wounded and captured at The Wilderness, Tommy became a prisoner on 8th May, which suggests he was likely taken at Laurel Hill on the Spotsylvania Courthouse battlefield. He would ultimately end up in Andersonville POW Camp, where Tommy died of scurvy around the 16th August 1864. He is buried in grave 5942, which you can see here. As might be expected, his death had serious consequences for his parents back in Maine. Before long they were described as being in ‘indigent circumstances’ and had to take drastic steps to survive– in the words of one friend, ‘necessity compelled their separation.’ 67-year-old Mary went to live with her single daughter (also Mary) in Bangor, who supported them through her work as a seamstress, while 81-year-old Robert, who required more care, was compelled to move to relatives in New Brunswick. They appear never to have been reunited. The 1871 Census of Canada records Robert, now 88 years-old, in Fredericton Poor House; by which point he was being described as a widower. (5)

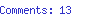

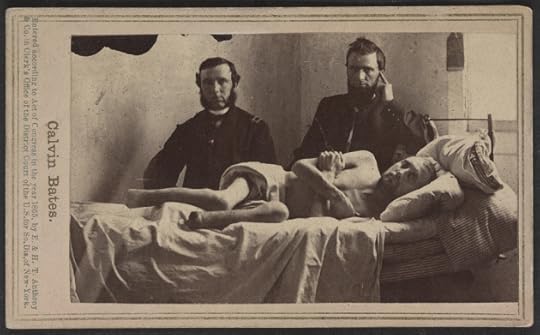

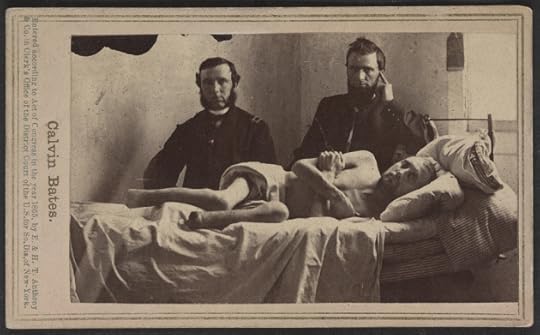

Calvin Bates served in Company E of the 20th Maine. Like Tommy he was captured at around the time of The Wilderness and ended up in Andersonville. He survived, but his ordeal there led ultimately to the amputation of both of his feet (Library of Congress)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Gerrish 1882: 43-44; (4) Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (5) Ibid., Desjardin 2009: 180, 1871 Census of Canada;

References & Further Reading

Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC141783

1871 Census of Canada, City of Fredericton, Carlton Ward, District 179 York, New Brunswick, Roll: C-10381; Page: 73; Family No: 267

Desjardin, Thomas A. 2009. Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign

Gerrish, Theodore 1882. Army Life: A Private’s Reminiscences of the Civil War, Late a Member of the 20th Maine Vols.

Thomas Welch Find A Grave Entry

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park

Gettysburg National Military Park

Andersonville National Historic Site

Filed under: Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Spotsylvania, Maine Tagged: 20th Maine, 20th Maine Andersonville, 20th Maine Fredericksburg, 20th Maine Spotsylvania, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Maine, Irish in New Brunswick, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

‘The Flag that Has Given Protection to Persecuted Countrymen’: One Irishman’s Service to the Union– and his Parents– in the 20th Maine

Perhaps one of the best known of all Irishmen to serve during the American Civil War was Buster Kilrain of the 20th Maine Infantry. Buster plays a major role in Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels, and was portrayed by actor Kevin Conway in the film Gettysburg. Kilrain, a loyal soldier and confidant of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, died of wounds received during the 20th’s famed actions on Little Round Top at Gettysburg. Of course Buster Kilrain is a fictional character– no one of that name ever served with the 20th Maine. However, real Irishmen were present in the regiment’s ranks. One of them was Tommy Welch, who like his fictional countryman was among the defenders of Little Round Top. Tommy shared other traits with Kilrain; both were among the older men in the regiment, and unfortunately both were destined not to survive the war. The pension file that was created as a result of Tommy Welch’s death reveals much about his pre-war life and circumstances. It includes a letter he wrote home– transcribed below– which not only explains one of his reasons for fighting, but also mentions the 20th Maine’s actions at the Battle of Fredericksburg. Tommy’s character is further revealed thanks to his popularity among the Maine men, which saw him remembered many years later by former comrades such as Theodore Gerrish when they sat down to record their memories of life during the American Civil War.

Buster Kilrain (Kevin Conway) engaging the Confederate on Little Round Top in Ron Maxwell’s ‘Gettysburg’ (Image: Dudster32)

It is not clear when the Welch family emigrated to North America, but they may well have travelled via Canada in the late 1830s or early 1840s. The family group consisted of Robert and Mary Welch, their son Thomas (Tommy), along with a number of other brothers and at least one sister. On the eve of the war Tommy’s parents were ageing; Mary Welch had been born around 1797, while Robert Welch celebrated his 77th birthday in 1860, having been born in 1783. Of their children, it was Tommy who bore chief responsibility for providing for them, foregoing starting a family of his own in order to see to their care. A neigbour in Bangor would later recall that his sister once asked Tommy why he had never married– he replied that he couldn’t, as his father and mother depended on him for their support. Tommy provided this support by working in the woods lumbering during the winter, and at a boom on the Nashwaak river rafting logs during the summer. A boom was a barrier placed in the river to collect timber that had been floated downstream from logging sites. This strenuous (and dangerous) livelihood saw Tommy travel some distance from Bangor; indeed he spent much of his time across the border. The Nashwaak is a Canadian river located in New Brunswick, where the town of Fredericton was home to a number of the extended Welch family. The seasonal nature of Tommy’s work creates problems that were all to common for many Irish laborers- the unpredictability of seasonal wages. While he could hope to earn $25-$30 per month on the river during the summer months, this earning potential fell away to between $15 and $20 a month during the winter. This type of uncertainty and fluctuation in income was a factor that many Irishmen would have taken into consideration when choosing whether or not to don Union blue during the 1860s. (1)

Whatever his ultimate reasons, it can’t have been an easy decision for Tommy to enlist in the Union cause. He told friends that he was going into the army in order to better support his parents, but he was also motivated by a sense of patriotism towards the Union. There is evidence for both economic and patriotic motivations in his subsequent actions, given the views he expressed to his brother in 1863 (below) and the fact that he sent at least $155 in bounty money to his parents. Nonetheless, enlistment meant travelling much further away from his parents than New Brunswick, and this must have been hard for a man so devoted to their welfare. Tommy was probably around 37 or 38 years old when he enlisted at Houlton on 6th August 1862, in what would become Company H of the 20th Maine Infantry. Within a matter of weeks he and his comrades were marching off to war, and their first encounter with the enemy. (2)

A log boom on the St. Croix River, Maine (National Archives)

The 20th Maine Infantry initially became part of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Corps of the Army of the Potomac. They arrived in time for the Battle of Antietam on 17th September 1862, but were kept in reserve and were not engaged. However, the Pine Tree State men were involved in the pursuit of Lee’s army as it made it’s way back across the Potomac. The 20th Maine crossed after them, but soon found that given the number of Rebels they faced on the other bank retreat was necessary. It was an incident that occurred during this re-crossing that remained fresh in the mind of 20th Maine veteran Theodore Gerrish’s many years later:

One very amusing incident occurred in our retreat. In Company H was a man by the name of Tommy Welch, an Irishman about forty years of age, a brave, generous-hearted fellow. He was an old bachelor, and one of those funny, neat, particular men we occasionally meet. He always looked as if he had emerged from a bandbox; and the boys used to say that he would rather sacrifice the whole army of the Potomac, than to have a spot of rust upon his rifle, or dust upon his uniform. He was always making the most laughable blunders, and was usually behind all others in obeying any command. When our regiment went tumbling down over the side of the bluff, to reach the river, the men all got down before Tommy understood what they were doing. Then very slowly he descended, picking his path carefully among the trees and rocks, and did not reach the river until the rear of the regiment was nearly one-half of the way across. The officer who commanded our regiment on that day rode a magnificent horse, and as the regiment recrossed, he sat coolly upon his horse near the Virginia shore, amidst the shots of the enemy, speaking very pleasantly to the men as they passed him. He evidently determined to be the last man of the regiment to leave the post of danger. He saw Uncle Tommy, and although the danger was very great, he kindly waited for him to cross. When the latter reached the water, with great deliberation he sat down upon a rock, and removed his shoes and stockings, and slowly packed them away in his blanket. Then his pant legs must be rolled up, so that they would not come in contact with the water; and all the time the rebels were coming nearer, and the bullets were flying more thickly. At last he was ready for an advance movement, but just as he reached the water, the luckless pant legs slipped down over his knees, and he very quietly retraced his steps to the shore, to roll them up again. This was too much for even the courtesy of the commanding officer, who becoming impatient at the protracted delay, and not relishing the sound of the lead whistling over his head, cried out in a sharp voice: “Come, come, my man, hurry up, hurry up, or we will both be shot.” Tommy looked up with that bewildered, serio-comic gravity of expression for which the Emerald Isle is so noted, and answered in the broadest brogue: “The divil a bit, sur. It is no mark of a gintleman to be in a hurry” The officer waited no longer, but putting spurs to his horse, he dashed across the river while Tommy, carrying his rifle in one hand, and holding up his pant legs in the other, followed after, the bullets flying thickly around him. Poor Tommy Welch, brave, blundering and kind, was a favorite in his company, and his comrades all mourned when he was shot down in the wilderness. He was there taken prisoner, and carried to Andersonville prison, where he died of starvation. (3)

Reunion of veterans of the 20th Maine at Gettysburg in 1889 (www.mainememory.net)

Although Gerrish’s description of the event demonstrates a stereotypical and somewhat racist characterisation of the Irish that was common at this time, it nonetheless demonstrates that there was genuine affection for ‘Uncle Tommy’ within the 20th Maine. The regiment’s first major direct experience of combat would follow a few weeks later at the Battle of Fredericksburg on 13th December 1862. The 20th Maine participated in one of the last attacks against Marye’s Heights, and were forced to stay on the field through the night in front of the Rebel position. More than a month after that battle, on 26th January 1863, Tommy wrote home to his brother Robert. Robert appears to have been in New Brunswick, which caused a delay in his letter to Tommy (to which this letter is responding) reaching the front.

Falmouth VA Jan 26 63

Dear Brother I recived your letter dated Oct 20 a few dayes ago and am glad to hear from you But think you are a little unjust in not writing to me before I have recieved but one letter from you the letter you wrote was delayed in Frederton [Fredericton, New Brunswick] about tow months If you write they [there] will be now [no] trouble but what I shall get them The postage must be paid before they can come

I was very sorry to learn of Brother B. Albert misfortune I hope he will be better in short time you must tell sister Mary to write to me as you can give her the directions I think she is a little ungratefull in not writing me before. I want you to let me now what [you] are doing this pleasant winter and the rest of my Brothers I think I can see the hills all congealed with snow while I am in the sweat suny South

But still I am not without trouble and trials but still I beare them willingly and more because the flag that [sic.] has given protection to [our] persecuted country men We are going to be paid of in a day or so and it will be quite a sum I will send it the same way I did before I am intitled to 55 dollars from the town of Houlton and in case it should be the will of God to call me from this world I oferise [authorise] you to collect it for me they are holden to pay it

[illegibile] is time I should tell you of the Battle of Fredericksburg we cross[ed] the Raperhanock the 13 Dec in the afternoon and marched doble quick into the citty and then we went upon the field and it was a bloody field I was struck with a shell we marched half a mile in front of the Rebles a rifle fire the shell struck me before we got on the field the Capt told me to go back and said I was badly hurt but I puut my trust in God and went forward (4)

Tommy’s letter indicates how his thoughts were turning to home (although there is perhaps a hint of sarcasm with respect to the weather) and also to providing for his parents. Given the horrors he must have gone through at Fredericksburg, his account of the engagement is remarkable in its matter-of-fact nature. Although the 20th Maine were not engaged at Chancellorsville, their finest moment of the war was to come later that summer. We know that Tommy was present with Company H when the 20th Maine became immortal on Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. Unfortunately as indicated by Theodore Gerrish, Tommy’s luck, like that of so many others, would run out during the bloody Overland Campaign of 1864. Although Gerrish states that Tommy was wounded and captured at The Wilderness, Tommy became a prisoner on 8th May, which suggests he was likely taken at Laurel Hill on the Spotsylvania Courthouse battlefield. He would ultimately end up in Andersonville POW Camp, where Tommy died of scurvy around the 16th August 1864. He is buried in grave 5942, which you can see here. As might be expected, his death had serious consequences for his parents back in Maine. Before long they were described as being in ‘indigent circumstances’ and had to take drastic steps to survive– in the words of one friend, ‘necessity compelled their separation.’ 67-year-old Mary went to live with her single daughter (also Mary) in Bangor, who supported them through her work as a seamstress, while 81-year-old Robert, who required more care, was compelled to move to relatives in New Brunswick. They appear never to have been reunited. The 1871 Census of Canada records Robert, now 88 years-old, in Fredericton Poor House; by which point he was being described as a widower. (5)

Calvin Bates served in Company E of the 20th Maine. Like Tommy he was captured at around the time of The Wilderness and ended up in Andersonville. He survived, but his ordeal there led ultimately to the amputation of both of his feet (Library of Congress)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Gerrish 1882: 43-44; (4) Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (5) Ibid., Desjardin 2009: 180, 1871 Census of Canada;

References & Further Reading

Thomas Welch Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC141783

1871 Census of Canada, City of Fredericton, Carlton Ward, District 179 York, New Brunswick, Roll: C-10381; Page: 73; Family No: 267

Desjardin, Thomas A. 2009. Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign

Gerrish, Theodore 1882. Army Life: A Private’s Reminiscences of the Civil War, Late a Member of the 20th Maine Vols.

Thomas Welch Find A Grave Entry

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park

Gettysburg National Military Park

Andersonville National Historic Site

Filed under: Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Spotsylvania, Maine Tagged: 20th Maine, 20th Maine Andersonville, 20th Maine Fredericksburg, 20th Maine Spotsylvania, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Maine, Irish in New Brunswick, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain

August 2, 2015

The Irish Brigade at Antietam: A Photographic Tour

Many of the posts on this site explore elements of the Irish experience at the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day of the Civil War, fought on 17th September 1862. Many of the widow’s pension files that I now concentrate on were created as a result of those day’s events. It was also a battle of unprecedented slaughter for the Irish Brigade. They were sent against the strong Confederate positions along the Sunken Lane, forever now remembered as Bloody Lane. In the process they suffered 540 casualties, including 113 killed outright and 422 wounded. Losses were particularly heavy in the 69th New York and 63rd New York. Last year I had an opportunity to visit the battlefield, and to walk some of the ground covered by the Irish Brigade that day. The photo gallery below is an attempt to present readers who may not have had that opportunity with some of the key locations that formed part of the Irish Brigade’s experience of that dreadful battle. You can view the gallery as a slideshow by clicking on any of the images below.

Filed under: 63rd New York, 69th New York, 88th New York, Battle of Antietam, Irish Brigade Tagged: 63rd New York, 69th New York, 88th New York, Battle of Antietam, Bloody Lane, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Antietam, Sunken Lane

August 1, 2015

‘Goodbye For A While’: An Irish Soldier’s Last Letter Home, Found on his Dead Body at Cold Harbor

On the 8th June 1864 Captain Dexter Ludden and his men from the 8th New York Heavy Artillery were picking their way through corpses. They had been assigned the unpleasant task of burying some of the many, many dead who had fallen assaulting the Confederate works at Cold Harbor. By then the bodies they were interring– who were from their own brigade– had lain on the field for five days. As they went about their gruesome work, Ludden’s soldiers checked each of the bodies for anything that might identify them. Turning over one of the lifeless forms, they hunted through the dead man’s pockets. Finding two scraps of paper inside, the burial party alerted the officer to their discovery. Reading through them, Captain Ludden recognised the papers as a hastily penned letter, written by the dead man before the assault. Later, Ludden sat down to sketch a few brief words of his own to add to them, before sending what amounted to the dead soldier’s last words on their way to New York. (1)

Surviving Confederate earthworks at Cold Harbor (Damian Shiels)

This is what Dexter Ludden wrote on the back of one of the pieces of paper recovered from the body:

Battlefield 7 miles from Richmond Va

June 8 1864

Madam,