Damian Shiels's Blog, page 36

July 25, 2015

Meagher’s ‘Drunken Freaks’ & Old Abe ‘Astonished’: The Last Letters of John Doherty, 63rd New York, Irish Brigade

Corporal John Doherty of the Irish Brigade wrote a series of letters home to his family from Virginia and Maryland in the summer of 1862. Transcribed here for the first time, the letters detail John’s pride in the Irish Brigade– ‘the envy of the rest of the army’– but likewise suggest that the realities of fighting had cured him of any romance concerning war– soldiering was ‘not what it is cracked up to be.’ Equally they describe his contact and experiences with well-known figures, be it the ‘drunken freaks’ of Thomas Francis Meagher, the call by George B. McClellan to give three cheers for the ‘old green flag’ or the opportunity the Irishmen had to ‘astonish’ President Abraham Lincoln. Described also are the hardships of the march, as the Brigade headed towards the disaster that was befalling their comrades at Second Bull Run, and the strength that religious faith could provide on the battlefield. Ultimately John’s are a sequence of letters that were cut short by what turned out to be the bloodiest day in United States history. (1)

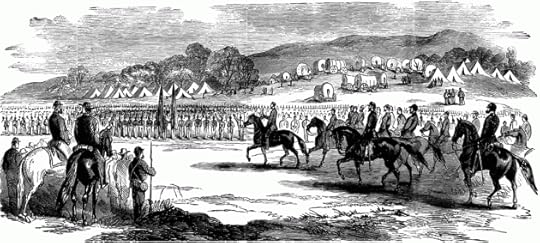

President Lincoln reviewing the troops at Harrison’s Landing, an event which John Doherty witnessed and described (Library of Congress)

John Doherty hailed from Ireland– it has not yet proved possible to establish where. His parents James and Ann had been married there on 25th May 1837, with John being born around the year 1839. At some juncture, probably around 1850, they emigrated to New York, eventually settling in Strattonport (later College Point) in Queens on Long Island. The 1860 Census records the family (in Flushing, Long Island) headed by 50-year-old Ann. John made his living in a local button factory, where he earned between $5 and $12 per week. With his father having passed away not long after the family came to America, John’s earnings were important to his wider family. It seems likely his then 19-year-old brother Patrick worked in the same trade, while his 17-year-old sister Mary is recorded as a ‘Factory girl.’ Their earnings helped to support not only their mother, but also their younger siblings Thomas (14) and James (10). Mary Donohue, a 27-year-old seamstress (possibly a relative of Ann) also lived with the family. All had been born in Ireland. On the 20th February 1862 John decided that his future lay away from the factory, and instead opted for the field of battle. On 3rd April 1862 he mustered in as a private in Company F of the 63rd New York Infantry, part of Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher’s Irish Brigade. (2)

John was soon writing home. His mother Ann was illiterate, but as was common for many, Irish neighbours Thomas Smyth and Patrick Curtin called round to read John’s letters to her when they arrived. The first letter preserved in John’s file was written from Harrison’s Landing, Virginia in late July, McClellan having withdrawn his army to that position following defeat during the Seven Days’ Battles. By this time John appears to have been promoted to Corporal.

July 19th/62

Harrisons Landing Va

Dear Mother,

I got your long looked for but welcome letter it being a month since I got a letter from you, I thought you had forgotten me. I hope you will not be as long without writing any more. I got paid 2 months pay yesterday we got paid to the 1st of May, I hear we will get 2 months more next week. I gave $25.00 to Father Dillon to send to you by Adams Express, my pay came to $29.90. I said in my letter to Pat that Father Dillon was put under arrest, he was released in 2 days after. He said he did not know why he was arrested, I think it was a drunken freak of Genel Meagher. Father Dillon is a very good man he is highly esteemed not only by the Brigade but by all the Irish Regts in this Army. Every place we go he has some kind of a church made of green boughs with the cross on top of it, many of them is scattered all over Virginia yet in the places we passed through. I got a letter from Uncle John a week ago he and family is well he has been long waiting for a letter from you but got none. I got a newspaper with your letter yesterday, you need not send me any more the[y] are too old when I get them, you might send me a weekly paper once in a while. If it would not be too much trouble I would like very much to get [a] box but I am afraid it would hardly come safe. If you would send one you might send 1 cotton pocket handkerchief, 1 towel, 4 sheets writing paper, 6 envelopes a bottle of ink needles and thread and a piece of chees[e] and a box of Ayers Pills. I have diarrhea this week past, I am able to do duty though I don’t feel very well. You need not go to much trouble about the box for it is only a chance whether it would come or not but if you send it send by Adams Express and mark it well– Co. F, 63 Regt., N.Y. Vols ., Haris[s]ons Landing, Va. We have all got knapsacks and every thing we want of clothing since we came here I want you to b[u]y a good dress out of the $25 Dollars and if there is enough left let Mary and Aunt Mary have a dress out of it, that is providing you don’t need it for some other more needful want. I was over with Pat Eagen the other day I saw Tom they are both well, Lieutenant James Smith has returned to his Company he is doing duty though he is a little leam [lame]. I saw Barney Doherty a week ago he is well he sent his best wishes to you all. I hope none of the boys will take it in to their head to list for soldiering is not what it is cracked up to be. I sent a letter to Pat and one to Joe Larkin giving some account of fighting we went through during the week that we changed our position from Fair Oaks to James River, this is a nice place and we don’t have much to do but the we[a]ther is very hot. President Linco[l]n visited us last week he was received with great enthusiasm although the army when passing through McClellan and several other Generals we gave three Cheers for him, Genl McClellan said boys give 3 more for the old green flag, which was given in a style that must have astonished old Abe. Write as soon as you get the money give my best respects to all my friends and my love to Mary and my Aunt and to my Brothers. I conclude with my love to dear Mother in the warmest manner,

Your affectionate son,

John Doherty. (3)

Ayer’s Pills were a popular medication for stomach complaints. This is a post Civil War advertisement for the product (East Carolina University DIgital Collections Image 12.1.23.13)

The Father Dillon referred to was James Dillon, the popular chaplain of the 63rd New York. It is not clear why Meagher had placed the priest under arrest, but John’s reference to a ‘drunken freak’ of General Meagher is interesting. Allegations of excessive drinking were often levelled at Meagher by his enemies, particularly with respect to his battlefield performance. The men of his Brigade never raised such combat-related concerns, and remained extremely loyal to their charismatic commander. However, references such as this (which suggests it may not have been an isolated ‘freak’) and comments on the General’s excessive drinking in private William McCarter’s memoirs do suggest that Meagher had a drink problem. The psychological strain Meagher would have been under from June 1862 onwards– when his Brigade was being exposed to heavy combat– may well have had an impact on his drinking habits. John also bore witness to Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the army at Harrison’s Landing on 8th July, when the President had arrived to meet with George B. McClellan, the army commander. McClellan was virtually idolised by the majority of the Irish Brigade. He was temporarily replaced as the Army of the Potomac’s commander by Lincoln following this visit. Pat and Tom Eagan both served in the 69th New York. Pat had enlisted aged 28 in 1861 and was discharged for disability in December 1862. Tom had been 31 when he enlisted in 1861; he was wounded at Antietam and discharged for disability in 1863. Lieutenant James Smith of the 69th had enlisted aged 27. He was wounded at Ream’s Station in 1864, and would eventually become Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment in 1865. John’s next letter was written at the start of August, with the Brigade still at Harrison’s Landing. (4)

Harrisons Landing August 1st/62

Dear Mother,

I received your letter of the 28th ulto. this morning, I am very glad that you so far recovered from your late illness as to be able to go to Brooklyn. I am glad that my sister and brothers and Aunt is well and I am well to[o] thanks be to God for this goodness to us. I got paid today 2 months pay, I sent you $25.oo by Adams Express Company. I would not have sent it today only that I got your letter and that you got the other without trouble. I wish you had not put yourself to so much [trouble] in sending a box for it is only a chance if I get it and I don’t think we well stop very long here, as we are under marching orders to be ready at a moments notice. Pat and Tom Egan is well I saw them twice since Sunday. I hope my friends in Brooklyn will excuse me for not writing as it is hard to get pens and ink here. As it is such a short time since I wrote to Mary I have nothing new so I will conclude with my love to you and to my brothers and sister and Aunt in the warmest manner,

Your affectionate son,

John Doherty. (5)

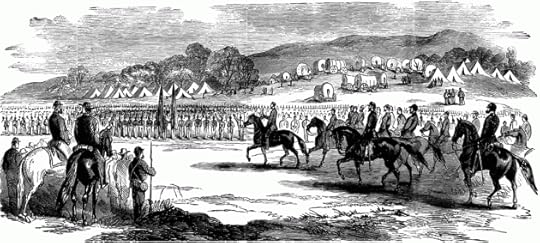

Members of the Irish Brigade at Harrison’s Landing in 1862. The figure seated in the centre is Father James Dillon, who John Doherty discusses in his contemporary letters (Library of Congress)

The final letter in John’s file dates to 4th September and was written from Maryland. The Irish Brigade were among units being withdrawn from the Virginia Peninsula to respond to Confederate movements, which would eventually seen the Rebels score a victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run fought between 28th and 30th of August. The Second Corps and the Irish Brigade arrived too late to assist in the fighting, but did help to cover the retreat of John Pope’s defeated forces:

Tenally Town Md Sept 4th/62

Dear Mother,

I take this opportunity of writing to you to let you know that I enjoy good he[a]lth thanks be to God. I hope this will find you all enjoying good he[a]lth. I rec’d a letter from you before I left Harrisons Landing, I got one from Mary at Newport News and 6 newspapers and a letter two days ago at Centerville. I am glad that you are well, we have had a very hard time of it since we left Harrisons Landing on Saturday the 16th of August. The first day we marched 4 miles, the second we marched 20, the next 5, the next 10, the next 10, the next 21, the next 9. The we[a]ther was very hot and we were almost smothered with dust but the cheerful spirit of the Irish Brigade made the road seem short, the funny joke and merry laugh of the men at all times whether on the battlefield, on the march or in camp makes the Brigade the envy of the rest of the army– the[y] would go along in silence looking sad while the Irish men would be laughing and singing. I began to write a letter to you at Newport News but before I had written two lines the order was given to fall in and I sealed it up and sent it to you we took the boat to Aquia Creek, we went from there to Fredericksburgh, from there back to Aquia Creek, then to Alexandria from there to Camp California, from there back to Alexandria and on to the Chain Bridge above Washington. We were there about 2 hours when we were ordered to fall in again and marched to Centerville near Bull Run without resting, then back to Fairfax. There we were left to cover the retreat of the right wing of the army, the enemy began to shell us there but done us no harm and when all the army had passed we covered their retreat. We then marched back and crossed the Chain Bridge and are now half a day without haveing to march any. We are about 6 miles from Washington through all the marching and fitegues [fatigues] and hunger, for we were six days on two days rations. I have not missed a role call though sometimes there would not be one fourth of [the] company present after a long march. I was offered a s[e]argents place in Company G but I did not like officers and would not take it.

Those small articles that you mention in one of your letters I have them yet and wear them all the time indeed the[y] gave me a feeling of safety in the time of danger when the shells was bursting over us and the bullets flying thick around I felt perfectly safe.

You may do as you please with the money I sent you, send me 2 dollars in your next letter I can get anything I want here as cheap almost as at home, any New York bills is as good here as anything else. I saw Pat and Tom Eagan day before yesterday they are well I saw all the Turners on Monday they are well. Sister Mary’s letter of the 37th ult. gives more Strattonport news than all I got since I left. I shall write to her in a few days, I have not got the box you sent me nor don’t expect to.

Give my respect to all my friends and neighbours and my love to my Aunt and sister and brothers your loving son,

John Doherty

Direct Meaghers Irish Brigade Washington DC

McArdle has not been with us since we were at Fredericksburg. (6)

John’s descriptions of the marching and the straggling that resulted provide a good impression of the physical toll such manoeuvres took on the men, as well as the esprit-de-corps of the Irish Brigade. The ‘small articles’ that John’s mother mentioned are almost certainly scapulars, which were popular among Irish Catholic troops. The same day that John wrote this letter, advance elements of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia moved into Maryland. Within a couple of days the Army of the Potomac, and the Irish Brigade, moved to respond. It was a campaign that culminated less than two weeks after John’s letter on the Antietam battlefield– the bloodiest single day of American history. It was also the worst day of the war for the 63rd New York; they took a total of 202 casualties in front of the Sunken Road– nearly 37.5% of the Brigade’s total. You can see a visualisation of just how devastating Antietam was to the 63rd here. The McArdle who John writes of not having seen since Fredericksburg (presumably a result of straggling), 38-year-old Francis McArdle, was one of those casualties. He made it back to his unit in time to be mortally wounded at Antietam, dying at Frederick on 9th October 1862. Another victim of the costly assault was Corporal John Doherty. In the end his scapulars did not protect him; his promised letter to his sister Mary likely went unwritten, the two dollars his mother sent him unspent. Ann Doherty would outlive her son by more than three and a half decades, passing away on 13th November 1898. She is buried in Mount Saint Mary Cemetery in Flushing. (7)

Antietam Battlefield. The Confederates held the Sunken Lane to the left of the image, with the Irish Brigade advancing from right to left across the field. It was in the vicinity of this field that John Doherty died (Damian Shiels)

*Punctuation and grammatical formatting has been added to the original letter for ease of reading. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid., 1860 Federal Census (the family are erroneously listed under ‘Dchartz’ on ancestry.com), New York Adjutant General 1902a: 42; (3) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (4) New York Adjutant General 1902b: 104, 105, 324; (5) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; Official Records: 192, New York Adjutant General 1902a: 112;

References & Further Reading

John Dougherty Dependent Mother Pension File WC 93207.

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

New York Adjutant General 1901a. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901 (Registers Sixty-Third New York Infantry).

New York Adjutant General 1901b. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901 (Registers Sixty-Ninth New York Infantry).

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 19, Part 1. Returns of Casualties in Union Forces.

East Carolina University Digital Collections.

Civil War Trust Battle of Antietam Page.

The Battle of Antietam on the Web.

Antietam National Battlefield.

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Antietam, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Antietam, Irish Brigade Antietam, Irish Brigade Peninsula, Last Letters Irish Soldier, Long Island Irish, New York Irish

Meagher’s ‘Drunken Freaks’ & Old Abe ‘Astonished': The Last Letters of John Doherty, 63rd New York, Irish Brigade

Corporal John Doherty of the Irish Brigade wrote a series of letters home to his family from Virginia and Maryland in the summer of 1862. Transcribed here for the first time, the letters detail John’s pride in the Irish Brigade– ‘the envy of the rest of the army’– but likewise suggest that the realities of fighting had cured him of any romance concerning war– soldiering was ‘not what it is cracked up to be.’ Equally they describe his contact and experiences with well-known figures, be it the ‘drunken freaks’ of Thomas Francis Meagher, the call by George B. McClellan to give three cheers for the ‘old green flag’ or the opportunity the Irishmen had to ‘astonish’ President Abraham Lincoln. Described also are the hardships of the march, as the Brigade headed towards the disaster that was befalling their comrades at Second Bull Run, and the strength that religious faith could provide on the battlefield. Ultimately John’s are a sequence of letters that were cut short by what turned out to be the bloodiest day in United States history. (1)

President Lincoln reviewing the troops at Harrison’s Landing, an event which John Doherty witnessed and described (Library of Congress)

John Doherty hailed from Ireland– it has not yet proved possible to establish where. His parents James and Ann had been married there on 25th May 1837, with John being born around the year 1839. At some juncture, probably around 1850, they emigrated to New York, eventually settling in Strattonport (later College Point) in Queens on Long Island. The 1860 Census records the family (in Flushing, Long Island) headed by 50-year-old Ann. John made his living in a local button factory, where he earned between $5 and $12 per week. With his father having passed away not long after the family came to America, John’s earnings were important to his wider family. It seems likely his then 19-year-old brother Patrick worked in the same trade, while his 17-year-old sister Mary is recorded as a ‘Factory girl.’ Their earnings helped to support not only their mother, but also their younger siblings Thomas (14) and James (10). Mary Donohue, a 27-year-old seamstress (possibly a relative of Ann) also lived with the family. All had been born in Ireland. On the 20th February 1862 John decided that his future lay away from the factory, and instead opted for the field of battle. On 3rd April 1862 he mustered in as a private in Company F of the 63rd New York Infantry, part of Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher’s Irish Brigade. (2)

John was soon writing home. His mother Ann was illiterate, but as was common for many, Irish neighbours Thomas Smyth and Patrick Curtin called round to read John’s letters to her when they arrived. The first letter preserved in John’s file was written from Harrison’s Landing, Virginia in late July, McClellan having withdrawn his army to that position following defeat during the Seven Days’ Battles. By this time John appears to have been promoted to Corporal.

July 19th/62

Harrisons Landing Va

Dear Mother,

I got your long looked for but welcome letter it being a month since I got a letter from you, I thought you had forgotten me. I hope you will not be as long without writing any more. I got paid 2 months pay yesterday we got paid to the 1st of May, I hear we will get 2 months more next week. I gave $25.00 to Father Dillon to send to you by Adams Express, my pay came to $29.90. I said in my letter to Pat that Father Dillon was put under arrest, he was released in 2 days after. He said he did not know why he was arrested, I think it was a drunken freak of Genel Meagher. Father Dillon is a very good man he is highly esteemed not only by the Brigade but by all the Irish Regts in this Army. Every place we go he has some kind of a church made of green boughs with the cross on top of it, many of them is scattered all over Virginia yet in the places we passed through. I got a letter from Uncle John a week ago he and family is well he has been long waiting for a letter from you but got none. I got a newspaper with your letter yesterday, you need not send me any more the[y] are too old when I get them, you might send me a weekly paper once in a while. If it would not be too much trouble I would like very much to get [a] box but I am afraid it would hardly come safe. If you would send one you might send 1 cotton pocket handkerchief, 1 towel, 4 sheets writing paper, 6 envelopes a bottle of ink needles and thread and a piece of chees[e] and a box of Ayers Pills. I have diarrhea this week past, I am able to do duty though I don’t feel very well. You need not go to much trouble about the box for it is only a chance whether it would come or not but if you send it send by Adams Express and mark it well– Co. F, 63 Regt., N.Y. Vols ., Haris[s]ons Landing, Va. We have all got knapsacks and every thing we want of clothing since we came here I want you to b[u]y a good dress out of the $25 Dollars and if there is enough left let Mary and Aunt Mary have a dress out of it, that is providing you don’t need it for some other more needful want. I was over with Pat Eagen the other day I saw Tom they are both well, Lieutenant James Smith has returned to his Company he is doing duty though he is a little leam [lame]. I saw Barney Doherty a week ago he is well he sent his best wishes to you all. I hope none of the boys will take it in to their head to list for soldiering is not what it is cracked up to be. I sent a letter to Pat and one to Joe Larkin giving some account of fighting we went through during the week that we changed our position from Fair Oaks to James River, this is a nice place and we don’t have much to do but the we[a]ther is very hot. President Linco[l]n visited us last week he was received with great enthusiasm although the army when passing through McClellan and several other Generals we gave three Cheers for him, Genl McClellan said boys give 3 more for the old green flag, which was given in a style that must have astonished old Abe. Write as soon as you get the money give my best respects to all my friends and my love to Mary and my Aunt and to my Brothers. I conclude with my love to dear Mother in the warmest manner,

Your affectionate son,

John Doherty. (3)

Ayer’s Pills were a popular medication for stomach complaints. This is a post Civil War advertisement for the product (East Carolina University DIgital Collections Image 12.1.23.13)

The Father Dillon referred to was James Dillon, the popular chaplain of the 63rd New York. It is not clear why Meagher had placed the priest under arrest, but John’s reference to a ‘drunken freak’ of General Meagher is interesting. Allegations of excessive drinking were often levelled at Meagher by his enemies, particularly with respect to his battlefield performance. The men of his Brigade never raised such combat-related concerns, and remained extremely loyal to their charismatic commander. However, references such as this (which suggests it may not have been an isolated ‘freak’) and comments on the General’s excessive drinking in private William McCarter’s memoirs do suggest that Meagher had a drink problem. The psychological strain Meagher would have been under from June 1862 onwards– when his Brigade was being exposed to heavy combat– may well have had an impact on his drinking habits. John also bore witness to Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the army at Harrison’s Landing on 8th July, when the President had arrived to meet with George B. McClellan, the army commander. McClellan was virtually idolised by the majority of the Irish Brigade. He was temporarily replaced as the Army of the Potomac’s commander by Lincoln following this visit. Pat and Tom Eagan both served in the 69th New York. Pat had enlisted aged 28 in 1861 and was discharged for disability in December 1862. Tom had been 31 when he enlisted in 1861; he was wounded at Antietam and discharged for disability in 1863. Lieutenant James Smith of the 69th had enlisted aged 27. He was wounded at Ream’s Station in 1864, and would eventually become Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment in 1865. John’s next letter was written at the start of August, with the Brigade still at Harrison’s Landing. (4)

Harrisons Landing August 1st/62

Dear Mother,

I received your letter of the 28th ulto. this morning, I am very glad that you so far recovered from your late illness as to be able to go to Brooklyn. I am glad that my sister and brothers and Aunt is well and I am well to[o] thanks be to God for this goodness to us. I got paid today 2 months pay, I sent you $25.oo by Adams Express Company. I would not have sent it today only that I got your letter and that you got the other without trouble. I wish you had not put yourself to so much [trouble] in sending a box for it is only a chance if I get it and I don’t think we well stop very long here, as we are under marching orders to be ready at a moments notice. Pat and Tom Egan is well I saw them twice since Sunday. I hope my friends in Brooklyn will excuse me for not writing as it is hard to get pens and ink here. As it is such a short time since I wrote to Mary I have nothing new so I will conclude with my love to you and to my brothers and sister and Aunt in the warmest manner,

Your affectionate son,

John Doherty. (5)

Members of the Irish Brigade at Harrison’s Landing in 1862. The figure seated in the centre is Father James Dillon, who John Doherty discusses in his contemporary letters (Library of Congress)

The final letter in John’s file dates to 4th September and was written from Maryland. The Irish Brigade were among units being withdrawn from the Virginia Peninsula to respond to Confederate movements, which would eventually seen the Rebels score a victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run fought between 28th and 30th of August. The Second Corps and the Irish Brigade arrived too late to assist in the fighting, but did help to cover the retreat of John Pope’s defeated forces:

Tenally Town Md Sept 4th/62

Dear Mother,

I take this opportunity of writing to you to let you know that I enjoy good he[a]lth thanks be to God. I hope this will find you all enjoying good he[a]lth. I rec’d a letter from you before I left Harrisons Landing, I got one from Mary at Newport News and 6 newspapers and a letter two days ago at Centerville. I am glad that you are well, we have had a very hard time of it since we left Harrisons Landing on Saturday the 16th of August. The first day we marched 4 miles, the second we marched 20, the next 5, the next 10, the next 10, the next 21, the next 9. The we[a]ther was very hot and we were almost smothered with dust but the cheerful spirit of the Irish Brigade made the road seem short, the funny joke and merry laugh of the men at all times whether on the battlefield, on the march or in camp makes the Brigade the envy of the rest of the army– the[y] would go along in silence looking sad while the Irish men would be laughing and singing. I began to write a letter to you at Newport News but before I had written two lines the order was given to fall in and I sealed it up and sent it to you we took the boat to Aquia Creek, we went from there to Fredericksburgh, from there back to Aquia Creek, then to Alexandria from there to Camp California, from there back to Alexandria and on to the Chain Bridge above Washington. We were there about 2 hours when we were ordered to fall in again and marched to Centerville near Bull Run without resting, then back to Fairfax. There we were left to cover the retreat of the right wing of the army, the enemy began to shell us there but done us no harm and when all the army had passed we covered their retreat. We then marched back and crossed the Chain Bridge and are now half a day without haveing to march any. We are about 6 miles from Washington through all the marching and fitegues [fatigues] and hunger, for we were six days on two days rations. I have not missed a role call though sometimes there would not be one fourth of [the] company present after a long march. I was offered a s[e]argents place in Company G but I did not like officers and would not take it.

Those small articles that you mention in one of your letters I have them yet and wear them all the time indeed the[y] gave me a feeling of safety in the time of danger when the shells was bursting over us and the bullets flying thick around I felt perfectly safe.

You may do as you please with the money I sent you, send me 2 dollars in your next letter I can get anything I want here as cheap almost as at home, any New York bills is as good here as anything else. I saw Pat and Tom Eagan day before yesterday they are well I saw all the Turners on Monday they are well. Sister Mary’s letter of the 37th ult. gives more Strattonport news than all I got since I left. I shall write to her in a few days, I have not got the box you sent me nor don’t expect to.

Give my respect to all my friends and neighbours and my love to my Aunt and sister and brothers your loving son,

John Doherty

Direct Meaghers Irish Brigade Washington DC

McArdle has not been with us since we were at Fredericksburg. (6)

John’s descriptions of the marching and the straggling that resulted provide a good impression of the physical toll such manoeuvres took on the men, as well as the esprit-de-corps of the Irish Brigade. The ‘small articles’ that John’s mother mentioned are almost certainly scapulars, which were popular among Irish Catholic troops. The same day that John wrote this letter, advance elements of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia moved into Maryland. Within a couple of days the Army of the Potomac, and the Irish Brigade, moved to respond. It was a campaign that culminated less than two weeks after John’s letter on the Antietam battlefield– the bloodiest single day of American history. It was also the worst day of the war for the 63rd New York; they took a total of 202 casualties in front of the Sunken Road– nearly 37.5% of the Brigade’s total. You can see a visualisation of just how devastating Antietam was to the 63rd here. The McArdle who John writes of not having seen since Fredericksburg (presumably a result of straggling), 38-year-old Francis McArdle, was one of those casualties. He made it back to his unit in time to be mortally wounded at Antietam, dying at Frederick on 9th October 1862. Another victim of the costly assault was Corporal John Doherty. In the end his scapulars did not protect him; his promised letter to his sister Mary likely went unwritten, the two dollars his mother sent him unspent. Ann Doherty would outlive her son by more than three and a half decades, passing away on 13th November 1898. She is buried in Mount Saint Mary Cemetery in Flushing. (7)

Antietam Battlefield. The Confederates held the Sunken Lane to the left of the image, with the Irish Brigade advancing from right to left across the field. It was in the vicinity of this field that John Doherty died (Damian Shiels)

(1) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid., 1860 Federal Census (the family are erroneously listed under ‘Dchartz’ on ancestry.com), New York Adjutant General 1902a: 42; (3) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (4) New York Adjutant General 1902b: 104, 105, 324; (5) John Dougherty Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; Official Records: 192, New York Adjutant General 1902a: 112;

References & Further Reading

John Dougherty Dependent Mother Pension File WC 93207.

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

New York Adjutant General 1901a. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901 (Registers Sixty-Third New York Infantry).

New York Adjutant General 1901b. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901 (Registers Sixty-Ninth New York Infantry).

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 19, Part 1. Returns of Casualties in Union Forces.

East Carolina University Digital Collections.

Civil War Trust Battle of Antietam Page.

The Battle of Antietam on the Web.

Antietam National Battlefield.

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Antietam, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Antietam, Irish Brigade Antietam, Irish Brigade Peninsula, Last Letters Irish Soldier, Long Island Irish, New York Irish

July 20, 2015

‘You Put Your Arm Around My Neck and Kissed Me’: Sex, Love & Duty in the Letters of an Irish Brigade Soldier

Letters included in the pension file often contain some very personal information. Surely few match those written by the Irish Brigade’s Samuel Pearce to his wife Margaret. The correspondence details not only the railroad man’s initial efforts to avoid the draft and use of an alias, but also provides a unique and intimate insight into the couple’s relationship. Samuel candidly discusses his concern for Margaret as she is about to go into labour, fondly recalls his love for her through memories of their first child’s birth, and expresses his disappointment at how she treated him on a visit home. Unusually, he also openly discusses their sex life. Readers should note that the final letter in the sequence contains language and content that some may find offensive. (1)

1864 Advertisement for the Baltimore & Ohio (Wikipedia)

Samuel Pearce worked on the Baltimore & Ohio railroad when he met Margaret McDonald around the year 1857. The couple were married in the English Lutheran Church of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania on 9th October 1859; their first child– William– was born on 2nd October 1860. Samuel did not rush to volunteer at the start of the war. Instead he stayed with what he knew, working under the direction of the U.S. Military Railroads commander, Herman Haupt. It was late 1863 when he wrote the first letter below to his wife. She was due to give birth to their second child at any moment, and Samuel was anxious for her wellbeing. Denied a furlough to go home, Samuel’s worries were exacerbated by news that his name had been drawn in the draft. Hopeful that the railroad authorities would secure an exemption for him, he nonetheless cautioned Margaret not to mention it to the neighbours.

Forgive me for not writing sooner

Sept the 5 1863

Dere Wife

I received your letter on last Tuesday and was very glad that you was still well but I wood feele a great [d]eal better if you ware over your truble and well again and then I wood be contented but now I cant rest at night for thinking about you I think that I can see you laying in bed sick as the night that you had Willia[m] when I com in the roome and stood in front of the bed and you put your arm around my neck and kissed me I shall never forget that time but I hope by the time you receive this you will be over the worst of your trubl and not have as hard a time as when you had Willia[m] and when I get home again I will hug and kiss you for to make up for the last time when I was home But if you get it very sick let me know at once I am still running at night I have not been very well for the last week but I feele a great [d]eal better I did not work for 4 days and I wanted to get a furlow for a five days but thay wood not give me one the superentendent told me that he wanted all of his men that has been drafted to stay at work with him that thare wont be any truble about it if thare is any truble at home about it let me know and I will get a letter frome him dont say anything to the nabors about this if thay ask you tell Genl Haupt has made arrangement with the sectary of war to leve us ware we are for the me[n] on the RR is getting very scarce since the Draft give my best respct to all of my old frends and kiss William for me and I will return it to you again if I can get a place for you in town to stay awile after you get right well again I want you to com down for it wont cost as much for you to come here as it [is] close for me to com home I will bring my letter to a [close] but remane your effectant Husband S.H. Pearce

Write as soon as you receive this and tell me how your belly is. (2)

Herman Haupt overseeing work on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, 1863 (Library of Congress)

As it was, Margaret had given birth three days before Samuel had written the letter. The couple’s second son John had arrived on 2nd September 1863. The next letter in the file is written some 6 months later, on 29th March 1864. By now Samuel’s circumstances had changed considerably. He was in Alexandria, Virginia, a newly recruited member of the 116th Pennsylvania Regiment, Irish Brigade (he had mustered in four days before). His railroad employment had not in the end provided an exemption; arrested by the Provost Marshal, Samuel was allowed his freedom only on the condition that he would enlist. This letter was the first news that Margaret received of his new profession. Samuel wrote home that his enlistment didn’t really matter anyway, as he felt his wife did not think much of him.

march the 29

Deare Wife

I take the presant opportunity of writing you a few lines I am well at presant and hope this will find you and the children the same I supose it will not be very pleasant for you to here whare I am at presant but thay got me at last I was running on the Pittsburgh and Fort Wayne Road and some body found out whare I was and I was arested and the prov[ost] marshall said if I wood enlist in som Penn Reightiment he wood let me go and I thaught that wood be the best thing I could do for I could not com home any how and I was all the time in truble and now thay cant arest me again so I will try it as will for if I did not go now I wood of have to gone some time and I think this is the best time now for thare will [be] a very large army this Spring thare is no end to the troups coming in I joined the 116 Penn R Comp I our Company is doing gard duty at Alexandria I dont know when we will joine the Reightiment I got $300 local bounty and will get $300 more government bounty if I stay long enough I sent you 2.75 dollars by exppress I kept 25 for I had to buy some things when you go for the money as for a bundle for I sent my overcoat and pants home donts wory your self about me for I am not much acount to you any haw I have no more to write this time when you write direckt your letter to Samuel Price Company I 116 Pennsly Volenteers Alexandria Va

Yours Truly

S. H. Pearce

Write as soon as you get this and tell me wether you got the money and bundle

I will write before wee leve Alexandria (3)

A Soldier’s dream of Home (Library of Congress)

Just over a week later Samuel was writing home again. The final letter in the file was clearly penned in reply to Margaret’s response to the previous correspondence. She had not taken the enlistment well and had done nothing but cry since his letter had arrived. Samuel sought to reassure her that he was relatively safe in the pioneer corps, and expressed a hope that if he could get through the summer he would get back to the railroad. He elaborated on his comments of the previous letter (and clearly is also addressing Margaret’s response in which she said she was faithful to him) by explaining how they arose because of the way Margaret treated him when he was last home– a passage which includes unusually explicit references to their sex life. Despite his unhappiness, Samuel reiterated his love for her; he closes by telling Margaret that he had enlisted under the name ‘Price’ instead of ‘Pearce’ to secure the bounty money– he was worried that if he didn’t use an alias the fact that he was drafted might deny it to him.

Camp near Culppeper

April the 8

Dere Wife

I received your letter yesterday and was glad to here that you was well but am sory that you take it so hard about me but try and content your self for the summer and then I will try and get detailed on the R. R. I dont think that I am in much danger for I was detailed out of the Company on monday and put in the Pinere Corps so I wont have any fighting to do as long as I am with it you speak of being true to me I never thaught any thing els of you for I know that you dont like fuckn very well and I dont think that you want any other man to do it for you for I think I alwaise gave you as much as you wanted but I think you apeard very coull [cool] towards me when I was home for I thaught you thaught more of your neabors than you did of me or else you wood [have] stayed up stairs with me more then you did when I asked you to wash my blouse you growld about it and you left me go away [with] dirty draws and stockings I thaught the way you apeared that you did not care wither I went away or not that is all the falt ever I found of you for I love you and all ways thaught that you might of been a little more loving to me when I cam home for it was not often that I cam hom to see you you say you don nothing but cry since you received my letter I have don the same thing about you for thare is hardley a minit that passes over but I think of you and what you wood do if I was kiled but if the war dont wind up this summer I think I can get out of it next winter so keep in good hart and I will do the hest I can and will write when ever I can get a chance we have a good [d]eal of work to do around camp building houses for the officers the resan that I told you to direckt to Price is that I inlisted in that name for I was afraid that thay might find out in the Regihtment that I was drafted and then I wood not get any bounty so when you write direckt Samuel P. Price Company I 116 R P. Volenteers Alexandria Va I wish you wood get me 2 woolen shirts of some kind for I cant ware the government shirts get something that wont shrink and get me 2 0r 3 pair of cottan stockings and some smoking tobacco and send them to me as soon as you can no more at presant but rmane your effectant Husgend S. H. Pearse

write soon

Dont forget and direct any letter to S. H. Price (4)

Samuel Pearce did not stay in the pioneer corps. Two months later he was in the ranks of the 116th Pennsylvania when they found themselves caught in a withering fire during the Battle of Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864. Struck in the lower left thigh by a bullet, he was carried from the field and ultimately to the 3rd Division Hospital in Alexandria. He died there of septicemia on 12th July. Samuel was buried in Alexandria National Cemetery, where he rests in Plot 2934– his headstone bears the alias under which he enlisted.

Despite their extremely personal content, Margaret handed these letters to the pension bureau, as their reference to Samuel’s alias provided evidence that established her as the rightful widow of ‘Samuel Price’. She received a pension for only a short period; her marriage to James Rementer in 1866 saw her lose her entitlement to it. Although her firstborn son William did not survive, her second son John did, joining three half-siblings by Margaret’s second marriage. John, whose imminent birth Samuel wrote of in 1863, would later say regarding him: ‘I do not remember my father. I understood that he was shot at Cold Harbor and died in the hospital from the effects of the wound. I was raised by my mother until I was grown…She re-married James Rementer. I grew up to consider him my father.’ Widowed for a second time in 1876, Margaret did not seek to reactivate her pension until 1911. She passed away at the Philadelphia Home for Veterans of the G.A.R. and Wives in Philadelphia on 3rd December 1924– fully sixty years after her first husband. (5)

Alexandria National Cemetery (Alexander Herring)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Samuel Pearce Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.;

References

Samuel H. Pearce Widow’s Pension File WC63690.

Civil War Trust Battle of Cold Harbor Page.

Richmond National Battlefield Park.

Samuel Price Find A Grave Memorial.

Filed under: 116th Pennsylvania, Battle of Cold Harbor, Irish Brigade Tagged: 116th Pennsylvania, Battle of Cold Harbor, Civil War Draft, Civil War Pregnancy, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Sex and the Civil War, Soldiers Letters Home

‘You Put Your Arm Around My Neck and Kissed Me': Sex, Love & Duty in the Letters of an Irish Brigade Soldier

Letters included in the pension file often contain some very personal information. Surely few match those written by the Irish Brigade’s Samuel Pearce to his wife Margaret. The correspondence details not only the railroad man’s initial efforts to avoid the draft and use of an alias, but also provides a unique and intimate insight into the couple’s relationship. Samuel candidly discusses his concern for Margaret as she is about to go into labour, fondly recalls his love for her through memories of their first child’s birth, and expresses his disappointment at how she treated him on a visit home. Unusually, he also openly discusses their sex life. Readers should note that the final letter in the sequence contains language and content that some may find offensive. (1)

1864 Advertisement for the Baltimore & Ohio (Wikipedia)

Samuel Pearce worked on the Baltimore & Ohio railroad when he met Margaret McDonald around the year 1857. The couple were married in the English Lutheran Church of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania on 9th October 1859; their first child– William– was born on 2nd October 1860. Samuel did not rush to volunteer at the start of the war. Instead he stayed with what he knew, working under the direction of the U.S. Military Railroads commander, Herman Haupt. It was late 1863 when he wrote the first letter below to his wife. She was due to give birth to their second child at any moment, and Samuel was anxious for her wellbeing. Denied a furlough to go home, Samuel’s worries were exacerbated by news that his name had been drawn in the draft. Hopeful that the railroad authorities would secure an exemption for him, he nonetheless cautioned Margaret not to mention it to the neighbours.

Forgive me for not writing sooner

Sept the 5 1863

Dere Wife

I received your letter on last Tuesday and was very glad that you was still well but I wood feele a great [d]eal better if you ware over your truble and well again and then I wood be contented but now I cant rest at night for thinking about you I think that I can see you laying in bed sick as the night that you had Willia[m] when I com in the roome and stood in front of the bed and you put your arm around my neck and kissed me I shall never forget that time but I hope by the time you receive this you will be over the worst of your trubl and not have as hard a time as when you had Willia[m] and when I get home again I will hug and kiss you for to make up for the last time when I was home But if you get it very sick let me know at once I am still running at night I have not been very well for the last week but I feele a great [d]eal better I did not work for 4 days and I wanted to get a furlow for a five days but thay wood not give me one the superentendent told me that he wanted all of his men that has been drafted to stay at work with him that thare wont be any truble about it if thare is any truble at home about it let me know and I will get a letter frome him dont say anything to the nabors about this if thay ask you tell Genl Haupt has made arrangement with the sectary of war to leve us ware we are for the me[n] on the RR is getting very scarce since the Draft give my best respct to all of my old frends and kiss William for me and I will return it to you again if I can get a place for you in town to stay awile after you get right well again I want you to com down for it wont cost as much for you to come here as it [is] close for me to com home I will bring my letter to a [close] but remane your effectant Husband S.H. Pearce

Write as soon as you receive this and tell me how your belly is. (2)

Herman Haupt overseeing work on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, 1863 (Library of Congress)

As it was, Margaret had given birth three days before Samuel had written the letter. The couple’s second son John had arrived on 2nd September 1863. The next letter in the file is written some 6 months later, on 29th March 1864. By now Samuel’s circumstances had changed considerably. He was in Alexandria, Virginia, a newly recruited member of the 116th Pennsylvania Regiment, Irish Brigade (he had mustered in four days before). His railroad employment had not in the end provided an exemption; arrested by the Provost Marshal, Samuel was allowed his freedom only on the condition that he would enlist. This letter was the first news that Margaret received of his new profession. Samuel wrote home that his enlistment didn’t really matter anyway, as he felt his wife did not think much of him.

march the 29

Deare Wife

I take the presant opportunity of writing you a few lines I am well at presant and hope this will find you and the children the same I supose it will not be very pleasant for you to here whare I am at presant but thay got me at last I was running on the Pittsburgh and Fort Wayne Road and some body found out whare I was and I was arested and the prov[ost] marshall said if I wood enlist in som Penn Reightiment he wood let me go and I thaught that wood be the best thing I could do for I could not com home any how and I was all the time in truble and now thay cant arest me again so I will try it as will for if I did not go now I wood of have to gone some time and I think this is the best time now for thare will [be] a very large army this Spring thare is no end to the troups coming in I joined the 116 Penn R Comp I our Company is doing gard duty at Alexandria I dont know when we will joine the Reightiment I got $300 local bounty and will get $300 more government bounty if I stay long enough I sent you 2.75 dollars by exppress I kept 25 for I had to buy some things when you go for the money as for a bundle for I sent my overcoat and pants home donts wory your self about me for I am not much acount to you any haw I have no more to write this time when you write direckt your letter to Samuel Price Company I 116 Pennsly Volenteers Alexandria Va

Yours Truly

S. H. Pearce

Write as soon as you get this and tell me wether you got the money and bundle

I will write before wee leve Alexandria (3)

A Soldier’s dream of Home (Library of Congress)

Just over a week later Samuel was writing home again. The final letter in the file was clearly penned in reply to Margaret’s response to the previous correspondence. She had not taken the enlistment well and had done nothing but cry since his letter had arrived. Samuel sought to reassure her that he was relatively safe in the pioneer corps, and expressed a hope that if he could get through the summer he would get back to the railroad. He elaborated on his comments of the previous letter (and clearly is also addressing Margaret’s response in which she said she was faithful to him) by explaining how they arose because of the way Margaret treated him when he was last home– a passage which includes unusually explicit references to their sex life. Despite his unhappiness, Samuel reiterated his love for her; he closes by telling Margaret that he had enlisted under the name ‘Price’ instead of ‘Pearce’ to secure the bounty money– he was worried that if he didn’t use an alias the fact that he was drafted might deny it to him.

Camp near Culppeper

April the 8

Dere Wife

I received your letter yesterday and was glad to here that you was well but am sory that you take it so hard about me but try and content your self for the summer and then I will try and get detailed on the R. R. I dont think that I am in much danger for I was detailed out of the Company on monday and put in the Pinere Corps so I wont have any fighting to do as long as I am with it you speak of being true to me I never thaught any thing els of you for I know that you dont like fuckn very well and I dont think that you want any other man to do it for you for I think I alwaise gave you as much as you wanted but I think you apeard very coull [cool] towards me when I was home for I thaught you thaught more of your neabors than you did of me or else you wood [have] stayed up stairs with me more then you did when I asked you to wash my blouse you growld about it and you left me go away [with] dirty draws and stockings I thaught the way you apeared that you did not care wither I went away or not that is all the falt ever I found of you for I love you and all ways thaught that you might of been a little more loving to me when I cam home for it was not often that I cam hom to see you you say you don nothing but cry since you received my letter I have don the same thing about you for thare is hardley a minit that passes over but I think of you and what you wood do if I was kiled but if the war dont wind up this summer I think I can get out of it next winter so keep in good hart and I will do the hest I can and will write when ever I can get a chance we have a good [d]eal of work to do around camp building houses for the officers the resan that I told you to direckt to Price is that I inlisted in that name for I was afraid that thay might find out in the Regihtment that I was drafted and then I wood not get any bounty so when you write direckt Samuel P. Price Company I 116 R P. Volenteers Alexandria Va I wish you wood get me 2 woolen shirts of some kind for I cant ware the government shirts get something that wont shrink and get me 2 0r 3 pair of cottan stockings and some smoking tobacco and send them to me as soon as you can no more at presant but rmane your effectant Husgend S. H. Pearse

write soon

Dont forget and direct any letter to S. H. Price (4)

Samuel Pearce did not stay in the pioneer corps. Two months later he was in the ranks of the 116th Pennsylvania when they found themselves caught in a withering fire during the Battle of Cold Harbor on 3rd June 1864. Struck in the lower left thigh by a bullet, he was carried from the field and ultimately to the 3rd Division Hospital in Alexandria. He died there of septicemia on 12th July. Samuel was buried in Alexandria National Cemetery, where he rests in Plot 2934– his headstone bears the alias under which he enlisted.

Despite their extremely personal content, Margaret handed these letters to the pension bureau, as their reference to Samuel’s alias provided evidence that established her as the rightful widow of ‘Samuel Price’. She received a pension for only a short period; her marriage to James Rementer in 1866 saw her lose her entitlement to it. Although her firstborn son William did not survive, her second son John did, joining three half-siblings by Margaret’s second marriage. John, whose imminent birth Samuel wrote of in 1863, would later say regarding him: ‘I do not remember my father. I understood that he was shot at Cold Harbor and died in the hospital from the effects of the wound. I was raised by my mother until I was grown…She re-married James Rementer. I grew up to consider him my father.’ Widowed for a second time in 1876, Margaret did not seek to reactivate her pension until 1911. She passed away at the Philadelphia Home for Veterans of the G.A.R. and Wives in Philadelphia on 3rd December 1924– fully sixty years after her first husband. (5)

Alexandria National Cemetery (Alexander Herring)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Samuel Pearce Widow’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.;

References

Samuel H. Pearce Widow’s Pension File WC63690.

Civil War Trust Battle of Cold Harbor Page.

Richmond National Battlefield Park.

Samuel Price Find A Grave Memorial.

Filed under: 116th Pennsylvania, Battle of Cold Harbor, Irish Brigade Tagged: 116th Pennsylvania, Battle of Cold Harbor, Civil War Draft, Civil War Pregnancy, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Sex and the Civil War, Soldiers Letters Home

July 12, 2015

The Iveagh House Lecture on the Irish of the American Civil War

As I have noted regularly over the last number of years on this site and elsewhere, Ireland has not done enough to remember the impact of the American Civil War on people from the island. Recent months have however seen an increasing effort in this regard, with a number of events taking place which suggest that further recognition and study of this impact in Ireland may be in the offing. One of the most significant of these took place at the Department of Foreign Affairs in Iveagh House, Dublin on Tuesday 9th June last. Since 2012 the Department have held a series of commemorative lectures recalling significant events in Irish history, delivered by noted speakers. They have covered topics such as Irish Unionism, Ireland and America, the Downing Street Declaration and the Christmas Truce of 1914, with lecturers including UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Northern Ireland First Minister Peter Robinson, Governor of Maryland Martin O’Malley, former UK Prime Minister John Major, Congressman John Lewis, former President of Ireland Mary McAleese and Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney (for a full list of the topics and speakers see here). The June lecture was delivered by Professor Patrick Griffin, Madden-Hennebry Professor and Chair of of the Department of History at the University of Notre Dame– his topic was Ireland, the Irish and Civil War America.

Professor Griffin delivering the Iveagh House Lecture (Department of Foreign Affairs)

The decision of the Department of Foreign Affairs to recognise the Irish of the Civil War in this fashion was most welcome. In attendance at the event were Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs Charlie Flanagan T.D., U.S. Ambassador to Ireland Kevin O’Malley and the Papal Nuncio, among others. Minister Flanagan began the evening with some very appropriate opening remarks, which you can read here. Professor Griffin then delivered an excellent lecture on the topic of the Irish and the Civil War; I was privileged to act as one of the official respondents to it, together with Dr. David Gleeson, Professor of American History at the the University of Northumbria. You can read a bit more about the event here and the notes on which I based my response are reproduced in full below. Thanks are due to everyone in the Department of Foreign Affairs for making this event a reality, marking as it does an important step on the road for greater recognition of this important facet of Irish and Irish-American history.

Myself, Professor Griffin, Minister Flanagan & Professor Gleeson at the Iveagh House event (Department of Foreign Affairs)

Response to Iveagh House Lecture, Dublin, 9th June 2015

Minister Flanagan, Ambassador O’Malley, ladies and gentlemen. It is a great honour and privilege for me to have an opportunity to address you as part of this memorial evening. I would also like to congratulate Professor Griffin on what was an excellent lecture. Among the topics he touched upon was the impact of the Famine on emigration to America; it is worth us remembering that for many of our country people, the cataclysm of war that erupted in 1861 was the second great trauma of their lives– all too many had already experienced loss and tragedy during the years of the potato blight. One example of this is the story of one woman I have recently been exploring–Mary Madigan, from Causeway, Co. Kerry. Mary was married in the 1830s, but would lose her husband to dropsy during the Famine, in ‘Black ’47.’ She and her three children subsequently emigrated, becoming part of Ireland’s lost Famine generation. But Mary’s story did not end with her departure from Ireland. Initially settling in New York, she would later remarry and move to Columbus. Unfortunately Mary fell victim to domestic violence; eventually her now grown son facilitated Mary’s escape from her husband and she returned to New York to live with him. In 1861 that son took to the battlefield in the ranks of the 69th New York State Militia, where he was killed at the Battle of Bull Run.

Professor Griffin spoke to us of the Fenians, of connections between Ireland and America, and of the interest Irish-Americans continued to take in their native land. This of course, stretched far beyond support for revolution in Ireland; the 19th century saw millions of dollars remitted to struggling relatives across the Atlantic. Although unremembered today, huge numbers of serving Union soldiers gave thousands of dollars in aid money to Ireland in early 1863, responding to a call to help stave of further Famine in Ireland. Many, like Michael Cuddy and James Cullen of the 42nd New York, gave multiple weeks wages to this fund. Many of these men also gave their lives for the Union– within weeks of their donation both Michael and James were dead, killed in action at Gettysburg.

Professor Griffin brought us through some of the bloodiest encounters experienced during the conflict. Although research has never taken place to establish precise figures, it is likely between 25 and 35,000 Irish-born died in the war. The conflict impacted Irish people everywhere, both in America and in Ireland. A 19th century visitor to Minister Flanagan’s hometown of Mountmellick may well have encountered the Sextoness of Mountmellick Church, Mary Kennedy. Every month Mary left her home in what is now Pearse Square to travel to the town’s post office, and receive her U.S. Government pension of $8 per month. Mary received this money because her son John, a First Sergeant in the 146th New York Infantry, had died a Prisoner of War in Georgia having been captured at the Battle of the Wilderness during the American Civil War. Similarly, Ambassador O’Malley’s grandparents in Westport, Co. Mayo, may well have been acquainted with the son of Mary McHale, who worked as a lawyer’s clerk in the town. Mary’s other son, Matthew, had taken a path that will sound familiar to the Ambassador– he emigrated to St. Louis, Missouri, where he ultimately enlisted in the 6th Missouri Infantry. Some years later, word was brought to his mother in Mayo that her boy had given his life during one of the great engagements of the war, at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Professor Griffin spoke of the long history of Ireland and America being conjoined. There is surely no greater example of this than the American Civil War. The latest estimates suggest that at least 200,000 Irish-born men fought in the conflict. This is to say nothing of American-born members of the Irish community. The first soldier to die in 1861 was Daniel Hough, a former farmer from Co. Tipperary. The last Union General to die in 1865 was also a former farmer, Thomas Smyth of Ballyhooly, Co. Cork. Statistics abound. One in every five Union sailors in the American Civil War was from Ireland. 18 Irishmen became Generals for either North or South–more than any other foreign country. At least 146 Medals of Honor were awarded to Irish born men– more than any other foreign country.

This is a conflict that deserves to get more attention in Ireland, purely because of its significance to our nation’s people. World War One is the only conflict in our history to have seen comparable numbers of Irishmen in service. Indeed, there is a strong possibility that more men from what is now the Republic of Ireland fought and died in the Civil War than in any other that Irish people have ever been involved in. For those counties worst affected by Famine emigration, the American Civil War is far and away the most significant in terms of scale that they have ever faced. Nor is it an event of the far distant past- the last Irish man to claim a pension for American Civil War service was Limerick’s Jeremiah O’Brien, who was still alive in 1950. Indeed a number of grandchildren of American Civil War veterans can still be found in Ireland today.

Tonight’s remembrance event is an occasion of great significance. For too long the story of tens of thousands of Irish people caught up in the great American struggle of 1861 to 1865 has been left in the shadows. I earnestly hope we are now experiencing the beginnings of an increasing focus on this remarkable connection between the United States and Ireland, one that continues to bind us to this day.

Professor Griffin, Ambaassdor O’Malley, MC Carole Coleman & Minister Flanagan at the Iveagh House event (Department of Foreign Affairs)

Filed under: Dublin, Memory Tagged: Charlie Flanagan, Commemoration, Department of Foreign Affairs, Irish American Civil War, Irish in America, Iveagh House Lectures, Kevin O'Malley, Memory

July 8, 2015

The Catholic Parish Registers Online: Revolutionizing the Search for 19th Century Irish Ancestors

Each week I receive correspondence from people with Civil War ancestors in search of their family’s origins in Ireland– something which is unfortunately often extremely difficult to determine. However, today has seen the release of a set of records that promises to open up new avenues for those seeking such information. To much fanfare in Ireland, the National Library of Ireland has made their entire collection of Catholic Parish Register microfilm images available online for the first time– even better, it’s all free. These microfilms contain information on baptisms and marriages for most of the parishes in Ireland up to c. 1880 and are the most important surviving source relating to Irish people in the 19th century. There are some gaps in the collection, both in terms of the parishes available and in the records which survived, but it is nonetheless a groundbreaking resource; over 390,000 digital images cover more than 1,000 Irish parishes. An attractive interface based on a topographical map of Ireland brings you to the scans of the microfilms for each parish. Unfortunately the material is not searchable beyond parish level, so it isn’t possible to search for individuals by name in these records. However, if you suspect your family came from a particular parish or area, you can work your way through the relevant microfilm images to see if their details are recorded. This website will undoubtedly be an important tool in the armoury of everyone looking for the origins of Irish veterans of the American Civil War, and indeed anyone with connections or an interest in 19th century Ireland. You can begin exploring the registers by clicking here.

The National Library of Ireland (YvonneM)

Filed under: Research, Resources, Update Tagged: 19th Century Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, Irish American Civil War, Irish Baptisms, Irish emigration, Irish in America, Irish Marriages, National Library of Ireland

July 4, 2015

‘My Brother! My Dear Brother’: The Extraordinary Encounter of an Irish Redcoat & Rebel During the War of Independence

The 4th of July is Independence Day in the United States, marking the adoption of the Declaration of Independence by the Continental Congress on 4th July 1776. Unsurprisingly given the nature of the conflict between 1775 and 1783, there were many Irish to be found on both sides. Although a departure from the American Civil War focus of the site, given the day that’s in it I wanted to share a brief but remarkable story of the Irish in the American Revolutionary War, the conflict which ultimately won the United States that independence.

The Saratoga Battlefield (Image: Matt Wade, UpstateNYer)

The incident was recorded by Sergeant Roger Lamb, who served in America for eight years. Born in Dublin City on 17th January 1756, Lamb grew up with a strong interest in military service– his brother had died as a result of wounds received on a Royal Naval vessel in 1761. In 1773, when he was 17-years-old, Roger lost all his money gambling. He decided to enlist in the army rather than return home to tell his father of his failing. His military career started as a private in the 9th Regiment of Foot and would take him to America– and service during the Revolutionary War. (1)

The Autumn of 1777 found Lamb and his regiment forming part of General John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga, New York, where they hoped to help end the Rebellion. Instead, they suffered two defeats to American forces under General Horatio Gates. Unable to escape, Burgoyne was forced to surrender his army to Gates on 17th October 1777; it was a victory which would see the French enter the war on the side of the Americans, and is often described as the ‘turning point of the American Revolution.’ During the surrender negotiations that October, British and American soldiers were often in plain sight of each other. It was during this period that Roger witnessed the following, surely one of the great chance encounters of military history:

It is a remark which has been made frequently by foreigners of most countries, that there is a feeling, a sensibility observable in the Irish character, which, if not absolutely peculiar to us, forms a prominent feature in our disposition. The following circumstance, of which many then in British as well as American armies were witnesses, may not be altogether unappropriate, particularly to the native reader.

During the time of the cessation of arms [at Saratoga], while the articles of capitulation were preparing, the soldiers of the two armies often saluted, and discoursed with each other from the opposite banks of the river, (which at Saratoga is about thirty yards wide, and not very deep,) a soldier in the 9th regiment, named Maguire, came down to the bank of the river, with a number of his companions, who engaged in conversation with a party of Americans on the opposite shore. In a short time something was observed very forcibly to strike the mind of Maguire. He suddenly darted like lightning from his companions, and resolutely plunged into the stream. At the very same moment, one of the American soldiers, seized with a similar impulse, resolutely dashed into the water, from the opposite shore. The wondering soldiers on both sides, beheld them eagerly swim towards the middle of the river, where they met; they hung on each others necks and wept; and the loud cries of “my brother! My dear brother” which accompanied the transaction, soon cleared up the mystery, to the astonished spectators. They were both brothers, the first had emigrated from this country, and the other had entered the army; one was in the British and the other in the American service, totally ignorant until that hour that they were engaged in hostile combat against each other’s life. (2)

The British Maguire brother has been identified by Don N. Hagist as Patrick Maguire of the 9th Foot. I have not as yet found a candidate for the American Maguire brother. Roger Lamb’s account of the incident attracted attention soon after he wrote it; the story was reported in a number of 19th century publications as well as his own memoirs. Today, this memorable encounter of America’s Revolutionary war is remembered with this historic marker in Saratoga County. (3)

Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga (Wikipedia)

(1) Hagist (ed.) 2004: 2, 7; (2) Saratoga National Historic Park History & Culture, Hagist (ed.) 2004: 54; (3) Hagist (ed.) 2004: 135;

References & Further Reading

Hagist, Don N. 2004. A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution

Saratoga National Historic Park

Filed under: American War of Independence Tagged: American War of Independence, Battle of Saratoga, Bnjamin Franklin, Horatio Gates, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Revolution, John Burgoyne, Sergeant Roger Lamb

‘My Brother! My Dear Brother': The Extraordinary Encounter of an Irish Redcoat & Rebel During the War of Independence

The 4th of July is Independence Day in the United States, marking the adoption of the Declaration of Independence by the Continental Congress on 4th July 1776. Unsurprisingly given the nature of the conflict between 1775 and 1783, there were many Irish to be found on both sides. Although a departure from the American Civil War focus of the site, given the day that’s in it I wanted to share a brief but remarkable story of the Irish in the American Revolutionary War, the conflict which ultimately won the United States that independence.

The Saratoga Battlefield (Image: Matt Wade, UpstateNYer)

The incident was recorded by Sergeant Roger Lamb, who served in America for eight years. Born in Dublin City on 17th January 1756, Lamb grew up with a strong interest in military service– his brother had died as a result of wounds received on a Royal Naval vessel in 1761. In 1773, when he was 17-years-old, Roger lost all his money gambling. He decided to enlist in the army rather than return home to tell his father of his failing. His military career started as a private in the 9th Regiment of Foot and would take him to America– and service during the Revolutionary War. (1)

The Autumn of 1777 found Lamb and his regiment forming part of General John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga, New York, where they hoped to help end the Rebellion. Instead, they suffered two defeats to American forces under General Horatio Gates. Unable to escape, Burgoyne was forced to surrender his army to Gates on 17th October 1777; it was a victory which would see the French enter the war on the side of the Americans, and is often described as the ‘turning point of the American Revolution.’ During the surrender negotiations that October, British and American soldiers were often in plain sight of each other. It was during this period that Roger witnessed the following, surely one of the great chance encounters of military history:

It is a remark which has been made frequently by foreigners of most countries, that there is a feeling, a sensibility observable in the Irish character, which, if not absolutely peculiar to us, forms a prominent feature in our disposition. The following circumstance, of which many then in British as well as American armies were witnesses, may not be altogether unappropriate, particularly to the native reader.

During the time of the cessation of arms [at Saratoga], while the articles of capitulation were preparing, the soldiers of the two armies often saluted, and discoursed with each other from the opposite banks of the river, (which at Saratoga is about thirty yards wide, and not very deep,) a soldier in the 9th regiment, named Maguire, came down to the bank of the river, with a number of his companions, who engaged in conversation with a party of Americans on the opposite shore. In a short time something was observed very forcibly to strike the mind of Maguire. He suddenly darted like lightning from his companions, and resolutely plunged into the stream. At the very same moment, one of the American soldiers, seized with a similar impulse, resolutely dashed into the water, from the opposite shore. The wondering soldiers on both sides, beheld them eagerly swim towards the middle of the river, where they met; they hung on each others necks and wept; and the loud cries of “my brother! My dear brother” which accompanied the transaction, soon cleared up the mystery, to the astonished spectators. They were both brothers, the first had emigrated from this country, and the other had entered the army; one was in the British and the other in the American service, totally ignorant until that hour that they were engaged in hostile combat against each other’s life. (2)

The British Maguire brother has been identified by Don N. Hagist as Patrick Maguire of the 9th Foot. I have not as yet found a candidate for the American Maguire brother. Roger Lamb’s account of the incident attracted attention soon after he wrote it; the story was reported in a number of 19th century publications as well as his own memoirs. Today, this memorable encounter of America’s Revolutionary war is remembered with this historic marker in Saratoga County. (3)

Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga (Wikipedia)

(1) Hagist (ed.) 2004: 2, 7; (2) Saratoga National Historic Park History & Culture, Hagist (ed.) 2004: 54; (3) Hagist (ed.) 2004: 135;

References & Further Reading

Hagist, Don N. 2004. A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution

Saratoga National Historic Park

Filed under: American War of Independence Tagged: American War of Independence, Battle of Saratoga, Bnjamin Franklin, Horatio Gates, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Revolution, John Burgoyne, Sergeant Roger Lamb

July 3, 2015

‘I Am Confused': The Emotional Shock of Pickett’s Charge as Experienced by a Family & Friend