Damian Shiels's Blog, page 30

July 4, 2016

Celebrating American Independence in Cork Harbour, 4th July 1862

Just as Americans today celebrate 4th of July–their Independence Day– wherever they find themselves around the World, such was also the case in foreign climes during the American Civil War. Cork Harbour has long had strong connections with North America, and in 1862 many U.S. nationals found themselves there on their national day. Efforts to celebrate the 4th in the Harbour centred around the U.S. Consul in Queenstown (now Cobh). He was joined by many other Americans, British and Irish aboard the steamer Black Eagle, as they set off on an excursion about the area. The Cork Examiner reported on the occasion, a piece that was later picked up by the New York Irish American.

“The boat steamed out beyond the light-house” Roche’s Point Lighthouse, at the entrance to Cork Harbour (Photo Copyright Charles W. Bash)

THE FOURTH OF JULY IN QUEENSTOWN

This great American festival, the anniversary of the independence of the United States, was celebrated yesterday in Cork Harbour, by an aquatic excursion and pic-nic, at which the United States’ Consul, Mr. P.J. Devine, and the Captain of all the American ships in the harbour, were present, as well as the consular representatives of several other powers, and a large party of ladies and getlemen. Mr. Dawson, of Queenstown, was the host on the occasion, and his steamer, the Black Eagle, having been put in readiness for the trip, was furnished with a plentiful store of viands, with which to satidfy the sharp calls of appetite that it was anticipated would be evoked by the sea breezes. About twelve o’clock, the party were on board, consisting of, besides Mr. Dawson and family, a large number of gentlemen and ladies from Queenstown, Passage, and their neighborhoods, and the following American gentlemen, besides the American Consul: Capt. Lovel, ship Ortolan, Ellsworth, Maine; Capt. Chipman, Harry Booth, New York; Capt. Gilmore, Lillias, Belfast, Maine; Capt. Chiney, H.D. Brookman, New York; Capt. Hungerford, Mary McRae, New York; Capt. Little, William Creevy, Philadelphia; Capt. Little, C.D. Mervin, New York; Capt. Haskell, Charles and Jane, Boston. The Italian and Greek Consuls were also present, and the Austrian Consul was represented in the person of his son.

The morning was very well suited for an aquatic excursion, being bright, clear, and warm, and the appearance of the sky giving every promise of a continuance of the same weather. The waters were ruffled by a light breeze, which tempered what might otherwise have been the oppressive heat of the sun, and the spacious harbour, with its many ships lying scattered over its bosom, as well as the beautiful scenery surrounding it on every side, looked to the best advantage. The steamer left the quay at twelve o’clock, and steamed out towards the harbour’s mouth, with the Stars and Stripes flying, saluting as she passed the several American vessels that lay on her way out, all of which, having their flags flying in honor of the day, returned the compliment. The boat steamed out beyond the light-house, and the party landed by permission at Trabolgan, where they walked about for some time, enjoying the vast prospect of the boundless ocean that lay before them, and admiring the many beauties of the Trabolgan domain. Dinner having been served and done full justice to, Mr. Devine, the American Consul, who occupied the chair, proceeded to propose the toasts and sentiments which had been prepared for the occasion. Unfortunately, however, a change very much for the worse had taken place in the aspect of the weather shortly before; the rain had begun to come down unpleasantly thick, and a general disposition was manifested towards a retreat on board the steamer, which necessarily obliged the proceedings to be cut short. The Consul, therefore, after expressing the high honor he felt at having such a distinguished company assembled to commemorate what in America was proudly called “Independence Day,” proposed, without any further remark the following toasts and sentiments, each of which, as he read it, was warmly received and drunk with due honors:-

1st. The day we celebrate- May it be our happiness, on its anniversary next recurring, to commemorate the reunited consolidation of the Great Republic.

2d. The President of the United States- As a statesman and patriot he has shown himself faithful to the high trust reposed in him by the people.

3d. The Queen of Great Britain- May her reign continue to be prosperous and glorious.

4th. The United States- The home of the oppressed of all nations, especially so of the sons of Ireland.

5th. Ireland- Faithful and true now as heretofore to the United States.

6th. The friends and promoters of trade and commerce in Queenstown.

Mr. John Dawson responded briefly. The next toast was;

The consular representatives of other nations who have favored us this day with their presence and sympathy.

Mr. Malori, on behalf of the consular body, briefly returned thanks.

“The Ladies” was next given and received with the enthusiasm due to the sentiment. It was responded to by Mr. Page, after which “The Press” was give and duly responded to, when the party re-embarked on board the steamer and returned to Queenstown, arriving there shortly after seven o’clock.

Trabolgan beach, where the 4th of July revellers spent much of their day in 1862. If you zoom out from this Google Maps view you will be able to see Cork Harbour and Cobh, from where the party set off.

References

New York Irish American Weekly 2nd August 1862. The Fourth of July in Queenstown

Filed under: Cork, Ireland Tagged: 4th of July in Ireland, Americans in Cork, Americans in Ireland, Independence Day, Irish American Civil War, Roche's Point, Trabolgan Beach, U.S. Consul Cork

June 30, 2016

“My Own Dearest Maggie”: The Last Letters of a Scottish Soldier of the American Civil War

My work on the widows and dependent pension files of American Civil War soldiers has revealed many hundreds of letters relating to Irish emigrants in the Union military. During the course of my research I have also come across files relating to other immigrant groups. Among them are many Scottish soldiers, whose dependents– like those of their Irish counterparts– often included letters written by their loved ones from the front in their pension applications. In future I hope to occasionally explore the stories of some of these non-Irish immigrants on the site. The first is the revealing and heartfelt correspondence of Corporal Frank Stewart Graham, written to his wife Maggie in 1863.

The frontispiece of the 165th New York’s History, demonstrating the coloured uniform which Frank and his comrades wore (History of the Second Battalion)

On 9th June 1854 Frank Stewart Graham and Maggie Smith were married in the parish church of Helensburgh– a town on the north shore of the Firth of Clyde in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. The couple made their home at 39 High Street in Ayr, where Frank worked as a painter. On 28th October 1855 the Grahams celebrated the birth of their first child, Martha, who was baptised in Ayr’s Trinity Episcopal Church on 6th January 1856. Shortly thereafter, for reasons unknown, the young family determined to emigrate to the United States. There they settled in Harlem– specifically in the 3rd District of the 12th Ward. Before long their first son, William, arrived, born in New York in the Autumn of 1859. The 1860 Census found 26-year-old Frank still following his trade as a painter, with a personal estate worth $100. A second boy, Robert, was born later the same year. Interestingly, unlike their sister, both boys were baptised in a Roman Catholic Church, namely St. Andrew’s on Manhattan. (1)

On 25th July 1862 Frank took the decision to enlist in the Union army, becoming a member of the 165th New York Infantry. Initially a member of Company B, he was transferred to Company E in December and would stay with them for the remainder of his service. Interestingly another Graham, 18-year-old Hugh, also joined Company B of the regiment. His birthplace was recorded as Glasgow, and it may well be that they were relatives, perhaps even brothers. When Frank eventually marched off to war he certainly looked the part. The 165th were intended to be a 2nd Battalion of Duryée’s Zouaves (the 1st Battalion being the famed 5th New York Infantry). They wore striking blue and red uniforms, adorned with sashes and topped off with blue-tasseled fezzes. Frank and his comrades left New York on 2nd December 1862 bound for the New Orleans and the Department of the Gulf, where they would serve as part of Brigadier-General Thomas Sherman’s division. It was from here that Francis would write home. (2)

Hugh Graham of the 165th New York in 1862. From Glasgow, he may have been a relative of Frank (Album of the Second Battalion)

Frank was stationed in Camp Parapet just outside New Orleans, when he wrote the first letter. In a theme common to many Civil War soldiers, he was impatient to receive letters from home, and was not shy in saying so. What is striking is Frank’s above average writing ability; he is particularly eloquent when expressing his affection for his wife and how much he wishes he could kiss her once more. Equally notable is Frank’s fervent support for the Union war effort, and contempt for those who were not giving their all at the front. Not only was Frank fighting for Union, he indicates that he was also fighting to advance the cause of emancipation. Strong support for the Union is a common theme throughout many immigrant soldier’s letters, even where, like Frank, they had only been in North America for a short period of time. In most instances, they had committed to their new home, and this was now their “Country.” Frank’s letter also provides an interesting description of New Orleans, and of his treatment by Confederate women– evidence of how strong support for the war effort was on the Home Front at this time. (3)

Camp Parapet

Near New Orleans

12 March 1863

My Own Dearest Maggie

The mail steamer which left New York on the 26th February and by which I expected a letter from you has arrived- and brought letters to Gelston- Owens- Tower and Baldwin, but none for me. What Maggie can be your reason for this long silence I am at a loss to conceive as since I left New York I have received but one from you and that was written on the 2nd Feby, just one month and ten days ago. I would liked to have known whether you received the $45-00 I sent you or not. Gelstons and Baldwins wives have received their they say- and surely to God you have received yours- If you have why not write me to make my mind easy, as you must know I do feel very uneasy until I am certain whether or not. Gelstons wife mention in her letter that you had written and sent your portrait. If so, I have not received it yet but perhaps it missed the last mail and will arrive with the next. I hope it may, and that it may be a good one, so that when I feel weary and drooping in spirits I can take it out of my bosom and press it to my lips, and think it is my own dear wife I am kissing. Oh Maggie how much would I give this moment to press you in my arms and imprint one kiss on your lips- but it cannot be until we have conquered the foe, which I hope to God will not be long. If once Vicksburg and Charleston was ours then the day would be won, but until then you need not believe any stories you hear about us coming home in May, or that peace will be proclaimed- it is all nonsense, started by cowardly hearted cravens who after 3 or four months soldiering would like to get home, and blow about being soldiers, instead of fighting as men and soldiers until the rebellion is put down once and forever, and then returning home as soldiers and heros with the conscious pride of having fought their country’s battles and conquered their country’s foes. I tell you Maggie from the depth of my heart, that if I was offered my discharge today I would not accept it, nor ever will until the rebellion is put down, no matter when that may be. Since I have enlisted in the cause of freedom I will stay until that cause is triumphant.

On last Tuesday the 10th we marched to New Orleans 8 miles and paraded the City and were received my Major General Sherman and returned in the evening, having marched about 20 miles. You will scarce believe me when I tell you that as passed along the streets and square the ladies closed their window blinds to show their spite. In front of one house where we rested for a few minets, they actually locked the gate to keep us from geting water to drink, and the sun raging high and hot. But our Col. got and give each man to drink a half gill of good whiskey, and then we did not care a fig for their water. I forgot to mention in my last 2 letters that I had been promoted to be color Corporal, that is to form one of the colour Guard composed of 8 corporal and 2 Sergts, whose only duty is to defend and protect the colours- it is no more extra pay, but only a little honour.

In the meantime Maggie I must close by wishing you good night. I hope Martha is a good girl and the 2 little fellows good boys to their Ma. I hope you make them say their prayers for their Father every night.

Your Affectionate Husband,

Frank S. Graham. (4)

Frank’s promotion to Color Corporal was an honour, but would also place him in one of the most dangerous parts of the field during any future assault. Of the soldiers Frank mentions in his letter, Samuel Gelston was a 27-year-old Philadelphia bricklayer who was transferred to the navy in 1864, while William Baldwin was a 35-year-old New York carpenter who mustered out with the unit in 1865. The next letter in the file was written just over two months later, from the Levee Steam Cotton Press building in New Orleans. Again, Frank expresses his dedication to the war effort, but also his love, care and desire to support his family. As he wrote, he witnessed a squad going to collect one of the regiment who had died of typhoid fever. His letter also captures a moment that would have long-term consequences for the 165th, and for Frank. Hastily scribbled in pencil is a postscript, dated 6 o’clock on 19th May 1863. Frank records that the regiment has just been ordered up the Mississippi, to join in the major efforts to secure Port Hudson. (5)

Frank’s friend Samuel Gelston of the 165th New York in 1862 (Album of the Second Battalion)

Levee Steam Cotton Press

Sunday 17 May 1863

New Orleans

Louisiana

No.9

My Dear Maggie,

My last letter written on the 10th was No 8. I forgot to number it. In your letters always mention the number of the last letter you received. Last Thursday I received your letter of the 26 April with the fifty cents inclosed. It was a glad sight, I had just been out marching and was pretty well worn out, with the sweat pouring down in streams when I opened the letter and seen it. I can assure you I was not long in getting the Captain to pass me out the gate, where I soon found means to get a rousing glass of good whiskey which done me a deal of good. Nor did I forget to wish you long life and many happy days for your thoughtfulness in sending it. I now receive all your letter and papers regularly and it gives me a great deal of pleasure when I now am certain of having a letter every week, so that I know how matters are get on with you and the children. I hope by this time you have received the eighteen dollars I sent by the Express to you on the 29 of last month, you say in your last for me not to be angry with you for spending the money, I sent it to you for to keep yourself and the children comfortable and I want you to do it, but Maggie I not want you to be noble hearted but I want you to keep yourself and the children as comfortable as possible until my return. I am enjoying as good health as I ever done in all my life. The weather is now geting pretty warm, but our barracks are nice and shady and cool. We are now geting better and more food than we have ever got since we left Staten Island- Frank Gray is cook again so I fare pretty well, but indeed we have all more than we can eat and plenty to spare.

Dear Maggie, there is a great many rumors around camp every day- some may be true but the most are lies. One day, Col. Hull is going to take command, another day the Secretary of War has ordered all the old 5th men shall be sent on to New York to join the regiment and go to Verginy, another day the regiment is going to be joined in with some other regiment, and all the Corporals and Sergants that pleases can go home for good and be mustered out the service, and every other sort of rumor. If you hear any such news in Harlem you will know what they are worth- nothing.

I can tell you Maggie when we will be home, just when the war is over, not a day sooner, and for my part I do not want to go to the old 5th [5th New York Infantry] over to Virginny either. I am perfectly satisfied and happy where I am, and proud of the regiment for it is the best drilled and disciplined regiment in the Deparment of the Gulph, and the healthest, although Maggie we have deaths occasionally from typhod fever. Just as I am writing this a squad is marching out of the gate for the Hospital to get the remains of their comrade who died last night, to lay him this morning in his narrow bed, over two thousand miles away from his home and friends- poor fellow. his marching days are over. He belonged to Co. B.

The Steamer that sailed from New York on the 6th with mails for here has not yet arrived, although the one that left on the 7th has arrived 3 days ago. We are afraid something has happened her. With the mail I send you a newspaper. It contains some very fine poetry- which I am sure you will admire- the one “After Taps” where at night in his tent, he thinks on his wife at home with the little one on her knee, and little Willie his 2nd oldest by at her side. I like it very much, and I sure you will, you will make Martha learn it. I hope she is still a good girl– she will soon get her necklace. Tell Sonney I want him to be a good boy and keep out of the mud, and when I come home I will drill him for to be a soldier, if ever war should break out again, so that he can go with his father the next time. And the little fellow, God bless him, I hope his little jolly face will always keep his mother’s heart glad until his father returns. I hope they will all have luck with their eggs, although I think you should not have let them until you moved into your new house. On the 10th I sent a letter to the Mercury, on the 21st I will send another so look out.

[in pencil]

Tuesday evening 6 o clock 19th May

My Own Dear Maggie,

We have received orders to go up the river to the battle field where General Banks is playing hell with the rebels- may God bless and protect you and the children- pray for my safety

God watch over you is my prayer,

your affectionate husband,

Frank S. Graham

The men are all in good spirits

[ in pen] All the Harlem men are well Billy Wheat has sent some newspapers and 2 letters. James Riley has written 1 letter, indeed they have all written with this mail. The next one sails on the 29th, 8 days from now. (6)

Again, Frank mentions a number of soldiers in his letter. Frank Gray (Grey) was a 39-year-old Rensselaer County carpenter. He would be captured in 1864 but was exchanged and mustered out in 1865. Billy Wheat was a 28-year-old New York painter who was wounded, but would survive the war. James Riley (Reilly) was a 21-year-old Irish plumber who was wounded and captured in 1864, but survived to be discharged. (7)

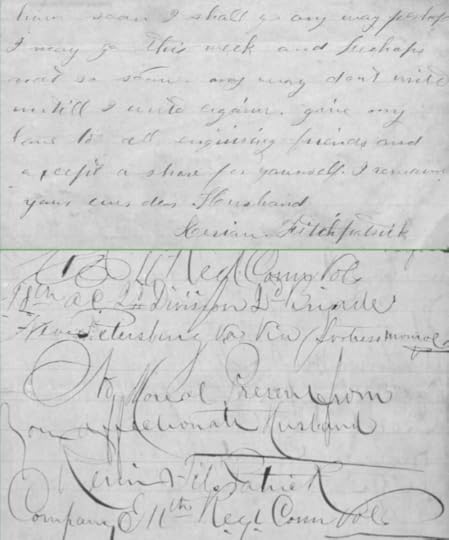

The rushed note Frank Graham added to his letter when he discovered he would be moving out to Port Hudson (NARA/Fold 3)

Frank mentions writing letters to the Mercury, a New York newspaper (it would be interesting to discover if these letters were ever printed). Evidently he had been greatly taken by the poem “After Taps” which he had sent to his wife. He clearly felt the soldier in the verse was someone he could identify with, and it impressed him so greatly that he instructed Maggie to have their daughter learn it by heart. The poem was written by Union soldier Colonel H.B. Sargent, and was published in The Atlantic Monthly in May 1863. It is here reproduced in full:

AFTER “TAPS.”

TRAMP! Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!

As I lay with my blanket on,

By the dim fire-light, in the moonlit night,

When the skirmishing fight was done.

The measured beat of the sentry’s feet,

With the jingling scabbard’s ring!

Tramp! Tramp! in my meadow-camp

By the Shenandoah’s spring.

The moonlight seems to shed cold beams

On a row of pale gravestones:

Give the bugle breath, and that image of Death

Will fly from the reveille’s tones.

By each tented roof, a charger’s hoof

Makes the frosty hill-side ring:

Give the bugle breath, and a spirit of Death

To each horse’s girth will spring.

Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!

The sentry, before my tent,

Guards, in gloom, his chief, for whom

Its shelter to-night is lent.

I am not there. On the hill-side bare

I think of the ghost within;

Of the brave who died at my sword-hand side,

To-day, ‘mid the horrible din

Of shot and shell and the infantry yell,

As we charged with the sabre drawn.

To my heart I said, “Who shall be the dead

In my tent, at another dawn?”

I thought of a blossoming almond-tree,

The stateliest tree that I know;

Of a golden bowl; of a parted soul;

And a lamp that is burning low.

Confederate earthworks at Port Hudson, the 165th New York’s destination (Library of Congress)

Oh, thoughts that kill! I thought of the hill

In the far-off Jura chain;

Of the two, the three, o’er the wide salt sea,

Whose hearts would break with pain;

Of my pride and joy, – my eldest boy;

Of my darling, the second– in years;

Of Willie, whose face, with its pure, mild grace,

Melts memory into tears;

Of their mother, my bride, by the Alpine lake’s side,

And the angel asleep in her arms;

Love, Beauty, and Truth, which she brought to my youth,

In that sweet April day of her charms.

“HALT! Who comes there?`’ The cold midnight air

And the challenging word chill me through.

The ghost of a fear whispers, close to my ear,

“Is peril, love, coming to you?”

The hoarse answer, “RELIEF,” makes the shade of a grief

Die away, with the step on the sod.

A kiss melts in air, while a tear and a prayer

Confide my beloved to God.

Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!

With a solemn, pendulum-swing!

Though I slumber all night, the fire burns bright,

And my sentinels’ scabbards ring.

“Boot and saddle!” is sounding. Our pulses are bounding.

“To horse!” And I touch with my heel

Black Gray in the flanks, and ride down the ranks,

With my heart, like my sabre, of steel. (8)

The final line of Frank’s letter was written on 21st May. Six days later, on 27th May, the Union military launched a frontal assault against Port Hudson’s Confederate works. A member of the 165th described the attack:

Early in the morning we were informed that there was to be an assault on the works…[that afternoon] our regiment…was designated to lead the brigade in the assault; as we advanced through the woods, coming to a clearing, we found trees for several hundred feet felled in all manner of directions; as we emerged from the woods the enemy opened on us with infantry and artillery; we manage to get through the fallen timber, but hardly a man had a decent pair of pants on him; our Colonel formed in division front on color division; this was done under constant fire; as soon as we formed the men were ordered to lie down in their positions, waiting for the rest of the brigade to come up; they did not get up to our line, so the Colonel ordered the charge; when about 150 yards from the works the enemy gave us grape and canister at short range; I never saw anything like it; our men were mowed down; the firing was terrific…the men by natural instinct deployed as skirmishers taking to whatever protection they could; we finally fell back the best we could. Such a sight; the dead and wounded lay thick; the wounded groaning and calling for water (of which we had little to give) and calling upon us not to desert them…(9)

The ground over which the 165th New York attacked at Port Hudson on the 27th May 1863 (History of the Second Battalion)

Among the dead was Frank Graham. The following year his widow Maggie, now living at 8 Mulberry Street in the notorious Five Points district of Manhattan, successfully applied for a widows pension for herself and her three small children. It is not known what became of her two boys, but when she was again in correspondence with the pension bureau in April 1867, neither of them were mentioned as minor dependents. By then Maggie had moved again, this time to 89 Cliff Street in Manhattan. Whether her two sons had died may be unknown, but the fate of the Grahams eldest daughter was recorded. Martha died on 11th October 1867, just two weeks short of her twelfth birthday. The Graham family futures had all been irrevocably altered by the decision to emigrate, and by Frank’s death at Port Hudson. His letters are just one of many Scottish examples in the files, which offer us an insight into what life was like for these Scots immigrants. On the occasion of the 41st anniversary of the 165th New York’s fateful assault, Joseph Mills Hanson, a nephew of one of the regiment’s officers, wrote a poem about the attack. One of the verses (Verse 17) mentions Frank Graham by name, and stands as a lasting memorial to his death, given for a cause in which he fervently believed.

THE ASSAULT

Dedicated to the Veterans of the One Hundred and Sixty-Fifth Regiment New York Volunteers (2d Duryee Zouaves) on the Forty-First Anniversary of Their Assault upon the Intrenchments of Port Hudson, La., May 27th, 1863.

Ho! comrades, drain a bumper and fling the cups away!

We drink to long-past glories; to buried friends to-day;

And, as those friends were gallant, those glories dearly gained,

See that the cup be brimming, the last red drop be drained!

Our ranks are sadly broken since forty years ago–

When, dressed in full battalion front, we marched to meet the foe.

From some, old age and illness have claimed the mortal price,

But the bullets of the Southron reaped the richest sacrifice.

Let’s roll the dead years back to-night and stand with them again

Upon the field where last we met, the living and the slain,

While mem’ry conjures up once more that bloody morn in May,

When grim Port Hudson’s booming guns announced the coming fray.

Far roll the lines of battle, o’er swamp and vale and height,

And, far and near, the battle-flags toss in the morning light;

A brave array is spread to-day to joust with waiting Death

And fan the face of Destiny with sacrificial breath!

For there is stretching, wide and deep, across our chosen way,

With giant trunk and pointed branch, the tangled abatis,

And reared beyond like headlands that guard a rock-fanged coast,

The heaving, yellow earthworks where waits the rebel host.

All silent lie those earthworks, as our futile field-guns play

Upon their mightly ramparts of stiff, unyielding clay;

But we know the siege-guns lurking in the redoubt’s curtained slits

And well we know the Enfields that will greet us from the pits!

But, hark! The cannon-fire is slacking to its close,

As down our serried columns, the word of caution goes.

Are any here to falter? Are there any laggards now,

Who tramped the long, forced, midnight march with Nickerson and Dow?

Come breathe a prayer to Heaven; cast terror to the wind,

For Sherman’s galloped out in front, with all his staff behind!

Our gallant Colonel’s in the van; his sword points out the way

Duryee’s Zouaves must follow in Glory’s path to-day!

Forward! The brazen bugle its stirring challenge flings

And forth into the open the line of battle swings;

Straight forth into the open, with measured tread and slow,

The Stars and Stripes above us, the burnished steel below;

Six hundred forms that stride as one, six hundred guns that shine,

Six hundred faces sternly set toward the far rebel line,

And, right and left, the regiments, steady as on parade,

That march with us to hazard the deadly escalade.

One moment yet, in silence redoubt and fieldtrench bide,

As if the foe gaze, spell-bound, upon the coming tide,

Then, like the livid lightning that frees the storm-cloud’s ire,

All down the close-embrasured line, leaps forth the siege-gun’s fire!

Have you heard the wind’s wild clamor when the midnight typhoon broke?

Have you timed the lightning’s measure as it rends the forest oak?

Such sounds will seem but music, sleep-wooing to your bed,

When you’ve harked to the yell of the ten-inch shell as it hurtles overhead?

They come, those sightless reapers; front, flank and rear they strike,

With sickening thud and spirting blood, smite high and low alike;

But our steady ranks close smoothly o’er each ragged fissure torn,

As the sea fills up the furrow that the passing prow has shorn.

We leave the open cornfields; unbroken, hold our way

Till we breast the leveled timber of the bristling abatis;

And, though the files break distance in the labyrinthian net,

There is neither halt nor tremor; we are rolling forward yet!

But see! along the trenches, below the foeman’s guns,

Yellow and swift and spiteful, a line of fire runs!

And, e’en as we hear the volley and the storm of rebel yells,

The abatis breaks forth in flame, lit by the bursting shells!

Come, cheer, Zouaves! No fear, Zouaves! We’re leading the brigade!

The men who fall but bid us all press onward, undismayed.

The men who fall! Dear God above, have pity on their souls!

They fall amid the burning trees, in pits of glowing coals!

Fosdick is down– the gallant lad whose guidon led the right;

No more we’ll see his brave young face, flushed with the battle-light.

Carville and Gatz and Graham are numbered with the slain

And D’Eschambault has fallen, never to rise again.

Extract of the New York Herald casualty list for the 165th New York at Port Hudson, printed on 4th July 18363. Frank’s name is listed among the dead (GenealogyBank)

Yet still, unchecked unconquered, the Zouaves strain ahead

With muskets clutched in bleeding hands, leaving a trail of dead.

While higher still the choking flames, roll like a furnace blast,

And, fast blown, with whirr and moan, the bullets whistle past!

More loudly swells the tumult; across the quaking plain,

Smoke-wreathed the tossing battle-flags rise, sink and rise again;

While, northward, crash the volleys, lashed out by shrapnel’s goad,

Of Augur’s fiery Irishmen, sweeping the Plain’s Store Road.

Inwood, the dashing captain, reels with a bitter wound;

Torn by an iron fragment, Vance totters to the ground;

But, Agnus, strong and eager, holds still the desperate path.

With Morris, French and Hoffman, on, on, through the gates of wrath!

Our shatter ranks are pausing upon the brink of doom;

Can human courage win to where those thund’ring breastworks loom?

See! far ahead, the flashing blade of Abel Smith still shines

And onward waves to soldiers’ graves or through the rebel lines!

One moment more his falchion its dauntless sign proclaims;

One moment more his Zouaves follow through shot and flames,

Then, like some forest monarch, crushed down before the storm,

With bleeding breast and nerveless hand, sinks that heroic form!

Ah, grim-faced War, one victim more your authors must atone!

Ah, Freedom, weep! Your wound is deep, for Abel Smith lies prone!

‘Reft of our chief, our columns pause in the scathing fire,

As paused the marching waters before the walls of Tyre.

The pause; then, slow, reluctant to quit the fatal spot,

With many a short-lived rally and many a backward shot,

The riven ranks, the tattered flags, the wounded and the whole

Back from that pit of Hades in sullen billows roll.

Crippled but not defeated; checked– but with bosoms steeled

To vengeance for the comrades lost upon that bloody field.

Ere cease the foeman’s volleys; ere yet the silence falls

The regiments are rearing the breaching-batteries’ walls.

‘Tis past and gone long years ago; we boys in blue to-day

Give cordial hands, not bullets, to the men who wore the gray;

To-day, across the pastures where we charged on that May morn,

The summer breezes whisper through ranks of growing corn.

The blackbird whistles from the fence, the sweet clematis vine

Tangles the earth where stretched but now the smoking fieldtrench line;

And o’er the fragrant grass-lands stand shocks of new-mown hay,

Where swept the Zouaves, cheering, through the burning abatis.

One starry banner flutters from Georgia’s storied ground

To where the snow-capped Cascades stand guard o’er Puget Sound;

Reared by the hands of heroes; guarded by freemen’s shields;

Saved by the men who perished on Southern battle-fields.

To-night, a grizzled remnant of those gallant hosts, we stand,

Dreaming old battles o’er again amid a peaceful land;

Proud that we once were of them; glad that our toil and pain

Helped to restore that banner, undimmed, to it’s place again.

But the thought most proud and tender is of those who have gone before,

And we trust to the Lord Jehovah, who rules both peace and war,

That again we may meet comrades, when, too, we are called away,

Who fell before Port Hudson’s guns, that bloody morn in May.

So drink the bumper roundly and toss the glasses clear!

To comrades sleeping soundly who would bid us drink in cheer,

As they, smiling, went from battle to the judgement of their God,

Let us, smiling, pledge their slumbers in their tents beneath the sod! (10)

The Brierwood Pipe by Winslow Homer, 1864. This depicts the 165th New York’s sister regiment, the 5th New York, but their uniforms were almost identical (Cleveland Museum of Art CVL491292)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Francis Graham Widow’s Pension File, 1860 Federal Census; (2) Roster of the 165th New York Infantry, New York Muster Roll Abstracts, New York State Military Museum, Troiani et a. 2002: 34; (3) Francis Graham Widow’s Pension File; (4) Ibid.; (5) New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (6) Francis Graham Widow’s Pension File; (7) New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (8) The Atlantic Monthly May 1863; (9) History of the Second Battalion Duryee Zouaves 1905: 17-18; (10) Ibid., 52-54;

References & Further Reading

Widow’s Certificate 33677 of Margaret Graham, widow of Corporal Francis Stewart Graham, 165th New York Infantry.

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

New York Herald 4th July 1863.

The Atlantic Monthly May 1863. “After Taps.”

New York State Military Museum: 165th New York.

New York Muster Roll Abstracts.

Roster of the 165th New York Infantry.

Anon,, 1905. History of the Second Battalion Duryee Zouaves: One Hundred and Sixty-fifth Regt. New York Volunteer Infantry.

Anon., 1906. Album of the Second Battalion Duryee Zouaves: One Hundred and Sixty-fifth Regt. New York Volunteer Infantry.

Troiani Don, Coates Earl J., McAfee Michael J. 2002. Don Troiani’s Civil War: Zouaves, Chasseurs, Special Branches & Officers.

Civil War Trust Siege of Port Hudson Page.

Filed under: Battle of Port Hudson, Scotland Tagged: 165th New York Infantry, Civil War Letters, Civil War Widows, Department of the Gulf, Duryees Zouaves, Irish American Civil War, Scotland American Civil War, Siege of Port Hudson

June 25, 2016

“I want to see you before I die”: Last Letters of Ulster Emigrants in American Civil War Pension Files

Two years ago I had the great pleasure of speaking at the Ulster-American Heritage Symposium in Athens, Georgia. The Symposium alternates between Ireland and North America every two years, and this year was back at its spiritual home, the Mellon Centre for Migration Studies at the Ulster-American Folk Park outside Omagh, Co. Tyrone. I was pleased to get an opportunity to speak again at this years event, which took place between 22-25 June. The Symposium also gave me a long awaited opportunity to explore the Folk Park, which is well worth a visit, and includes gems like the house in which John Hughes, the first Catholic Archbishop of New York, grew up. I spoke specifically on letters I have identified in the widows and dependent pension files that relate to Ulster families, both Catholic and Protestant. For the benefit of those of you who may be interested in the presentation, I have reproduced it in full below, together with the powerpoint slides that accompanied it.

The house in which John Hughes, first Catholic Archbishop of New York, grew up. “Dagger John” was an important figure during the period of the Civil War, and was instrumental in getting former Papal Officers like Myles Walter Keogh positions in the U.S. Army (Damian Shiels)

In an Irish context, the American Civil War is this island’s great forgotten conflict. At the outbreak of the fighting in 1861, 1.6 million people of Irish-birth resided in the United States. This is a figure that does not include the hundreds of thousands of Irish-Americans born into Irish communities in the United States, Canada and Britain, who often regarded themselves as much a part of the Irish community as those native to Ireland. By my estimates, some 200,000 Irish-born men served in Federal or Confederate uniform between 1861 and 1865. The vast majority- perhaps 180,000- did so wearing Union blue. Of them, tens of thousands were from Ulster.

In an Irish context, the American Civil War is this island’s great forgotten conflict. At the outbreak of the fighting in 1861, 1.6 million people of Irish-birth resided in the United States. This is a figure that does not include the hundreds of thousands of Irish-Americans born into Irish communities in the United States, Canada and Britain, who often regarded themselves as much a part of the Irish community as those native to Ireland. By my estimates, some 200,000 Irish-born men served in Federal or Confederate uniform between 1861 and 1865. The vast majority- perhaps 180,000- did so wearing Union blue. Of them, tens of thousands were from Ulster.

As I noted at the 2014 Symposium in Athens, and in my subsequent paper for the Irish Hunger and Migration volume, our failure to appreciate the scale of Irish involvement in the conflict- and more significantly our comparative neglect of its study in Ireland, North and South- has caused us to overlook one of the major sources relating to 19th century Irish emigration. These are the widows and dependent pension files of men who died as a result of their Civil War service in the Union military. The National Archives in Washington D.C. houses some 1.28 million such files, tens of thousands of which relate to Irish emigrants- and thousands of them to people from Ulster. I will not revisit today the background or overall content these files, which is a topic covered in the Irish Hunger and Migration volume. Suffice is to say that these files are filled with vast amounts of social data relating to Irish emigrants, which together constitute perhaps the greatest body of social information on Irish people in the 19th century United States.

As I noted at the 2014 Symposium in Athens, and in my subsequent paper for the Irish Hunger and Migration volume, our failure to appreciate the scale of Irish involvement in the conflict- and more significantly our comparative neglect of its study in Ireland, North and South- has caused us to overlook one of the major sources relating to 19th century Irish emigration. These are the widows and dependent pension files of men who died as a result of their Civil War service in the Union military. The National Archives in Washington D.C. houses some 1.28 million such files, tens of thousands of which relate to Irish emigrants- and thousands of them to people from Ulster. I will not revisit today the background or overall content these files, which is a topic covered in the Irish Hunger and Migration volume. Suffice is to say that these files are filled with vast amounts of social data relating to Irish emigrants, which together constitute perhaps the greatest body of social information on Irish people in the 19th century United States.

In order to be successful with their application, each prospective pensioner- be they a widow, a dependent parent, a dependent sibling, or a minor child- had to prove their relationship with, and often their financial dependence on, a deceased soldier. One way in which they did this was to include original letters written by the man in question, and it is on that particular source which we are concentrating today. Over recent years I have been systematically working my way through the c. 11% of the widows and dependents pension files that have been scanned, searching within each one to determine if they have an Irish connection, and if they contain such letters. To date, I have identified letters in the files of well in excess of 250 Irish and probable Irish-American soldiers, constituting in the region of 1,800 pages of letters. Most of these were written by soldiers and sailors during the war, though there are also some which were penned before the conflict, and a number which were written to soldiers by those on the Home Front. Unsurprisingly, these contain a wealth of insights into the Irish experience of both the American Civil War and America in general. For the remainder of the talk I want to explore some of what these letters have to say, with specific reference to the correspondence of Ulster emigrants.

In order to be successful with their application, each prospective pensioner- be they a widow, a dependent parent, a dependent sibling, or a minor child- had to prove their relationship with, and often their financial dependence on, a deceased soldier. One way in which they did this was to include original letters written by the man in question, and it is on that particular source which we are concentrating today. Over recent years I have been systematically working my way through the c. 11% of the widows and dependents pension files that have been scanned, searching within each one to determine if they have an Irish connection, and if they contain such letters. To date, I have identified letters in the files of well in excess of 250 Irish and probable Irish-American soldiers, constituting in the region of 1,800 pages of letters. Most of these were written by soldiers and sailors during the war, though there are also some which were penned before the conflict, and a number which were written to soldiers by those on the Home Front. Unsurprisingly, these contain a wealth of insights into the Irish experience of both the American Civil War and America in general. For the remainder of the talk I want to explore some of what these letters have to say, with specific reference to the correspondence of Ulster emigrants.

At the outset, it is worth noting that the existence of letters does not necessarily indicate literacy- indeed many of the soldiers who caused them to be composed were either illiterate or semi-literate. It was not unusual for correspondents to dictate their letters to a literate friend or companion, who would then also read aloud any return correspondence to the recipient. In this respect letters often constituted a more public or communal experience than we might expect, one that was shared between groups of trusted individuals. We must imagine many of these letters arriving home from the front, being read aloud to multiple family members around the table.

What then of their content? Unsurprisingly given the context of their survival, many of the letters make specific reference to finances, and of the efforts of Ulster soldiers to support those at home during the war. This often proved difficult given the erratic nature of wartime pay, which often came many months late. Soldiers also made efforts to see that their family were able to avail of relief monies made available to the dependents of those in the military. What is apparent is the intense pressure that many men were under to provide for those at home while at the front. For example, let’s hear from Bernard Curry, a native of Co. Armagh in the 182nd New York Infantry, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, who wrote home from the trenches outside Petersburg in 1864 to let his mother know that:

What then of their content? Unsurprisingly given the context of their survival, many of the letters make specific reference to finances, and of the efforts of Ulster soldiers to support those at home during the war. This often proved difficult given the erratic nature of wartime pay, which often came many months late. Soldiers also made efforts to see that their family were able to avail of relief monies made available to the dependents of those in the military. What is apparent is the intense pressure that many men were under to provide for those at home while at the front. For example, let’s hear from Bernard Curry, a native of Co. Armagh in the 182nd New York Infantry, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, who wrote home from the trenches outside Petersburg in 1864 to let his mother know that:

the paymaster come to us last night and paid us off so I am sending you 40 dollars with this letter. I am sending it by express, the way we have to do [it] is to give the money to the priest and he will send it for us.

Bernard survived his war service, only to be murdered by a fugitive in Texas while serving in the regulars. Terrence McFarland, from Newry, Co. Down, was also a member of the 182nd New York, and had similar financial concerns. In December 1862 he heard his mother had lost the relief ticket which would have allowed her to get support:

Dear mother I am very sorry that you lost that relief ticket that I gave to you but I am going to see can I get another on this day…I will look after it and as soon as I get it I will send it to you.

Terrence was later killed in action outside Petersburg on 16 June 1864.

Winter in the 1860s always brought increased financial pressures, given the necessity of purchasing fuel for heating. On 1 February 1862 James McGaffigan, a native of Clonmany, Co. Donegal, wrote home to his wife from the camp of the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade, in Virginia:

Winter in the 1860s always brought increased financial pressures, given the necessity of purchasing fuel for heating. On 1 February 1862 James McGaffigan, a native of Clonmany, Co. Donegal, wrote home to his wife from the camp of the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade, in Virginia:

I see by the newspapers that the winter is pretty cold and stormy all along the northern states, so I am glad that the relief I sent you arrived in such good season…I hope you will make yourself as comfortable as possible and at the same time be as economical as possible, for it may be a good length of time before I have it in my power to send you another money letter, for it is uncertain if we will be paid regularly or not.

James was killed in action at Antietam, America’s bloodiest day, a little over 7 months later.

William McCollister from Co. Antrim, a trooper in the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was among many to explicitly express his desire to take care of his family. Writing from Virginia in 1863 he remarked that:

one of the things that occupies my mind the most is the welfare of my good old mother that has taken care of me from my helpless moments up to the present time…it is my desire that I may comfort her in her old age and I had rather suffer all the privations incident to human nature than to hear of her suffering for the want of one of the necessaries of life.

William would ultimately die of complications relating to an early war wound.

Lieutenant Hugh McGraw of the 140th New York Infantry wrote to his mother from Virginia in May 1863 that he:

Lieutenant Hugh McGraw of the 140th New York Infantry wrote to his mother from Virginia in May 1863 that he:

was rather grieved and disappointed…to find that your health was rather poor, but I hope ere this reaches you that you will have recovered your former strength, and that God in his infinite mercy will be around you and bring you safe through your sickness… Knowing that I am necessarily absent and that there is none of the other members of the family near enough to pay any attention to you but I trust you will be able to get along…till I can again seek shelter under the old roof. If God in his divine Providence has so willed it that I again return to my home.

Hugh was mortally wounded on Little Round Top in Gettysburg.

Despite the worries of those at home, many Ulster soldiers found that army life agreed with them. Thomas McCready of the 74th New York Infantry, a native of Stranorlar, Co. Donegal, told his mother in November 1861 that:

Despite the worries of those at home, many Ulster soldiers found that army life agreed with them. Thomas McCready of the 74th New York Infantry, a native of Stranorlar, Co. Donegal, told his mother in November 1861 that:

I like soldiering as good now as I did the first day because I have a chance of seeing the country now.

He added:

I feel as happy now as I ever was, we have a good tent and a good bed that [holds] seven of us, also a good log chimney and a good comfortable fire.

This outlook didn’t prevent his mother from literally becoming sick with worry. In another letter Thomas wrote:

I am sorry that you took sick on my account. I have not been in any battle since I left home. Keep up good courage and do not believe everything that you hear, for I never felt better in my life.

His mother wanted him to come home for Christmas, but Thomas had to the news that:

I can’t be home at Christmas but I expect to be home shortly after it…there is nothing you [can] do for me to make me comfortable and the best you can do for me is to answer my letter and not to be grieving about me.

Thomas was killed in the 74th New York’s first major engagement of the war, at Williamsburg, Virginia, the following May.

For the most part the men were keen to reassure those at home they were safe and there was no need to worry. Many letters make reference to the likelihood that the war would hopefully soon end. John Monaghan, of Monaghan town and the 165th New York, wrote home from New Orleans, Louisiana telling his mother to:

For the most part the men were keen to reassure those at home they were safe and there was no need to worry. Many letters make reference to the likelihood that the war would hopefully soon end. John Monaghan, of Monaghan town and the 165th New York, wrote home from New Orleans, Louisiana telling his mother to:

not worry atall about me, I am in hope that the war will soon be at an end and that I may soon return home.

John was mortally wounded at Port Hudson, Louisiana in June 1863.

Expressions as to motivations or political viewpoints are relatively rare in the letters, but we do get occasional glimpses at how fervently many of these men supported the cause of Union. To turn once again to Antrim’s William McCollister, writing in 1862:

there has been a great many young fellows killed at this last battle that I was acquainted with, but we must not think hard of that. I am as liable to be killed as any one at present but I am just as willing for to die for my country as any white boy living.

While the majority of men stayed away from topics that might worry those at home, some letters indicate the impact that the sights, sounds and stresses of war had on these Ulstermen. Patrick Carney of Fintona, Co. Tyrone, was experiencing his first campaign on the Virginia Peninsula when he described the Fair Oaks battlefield to his mother:

While the majority of men stayed away from topics that might worry those at home, some letters indicate the impact that the sights, sounds and stresses of war had on these Ulstermen. Patrick Carney of Fintona, Co. Tyrone, was experiencing his first campaign on the Virginia Peninsula when he described the Fair Oaks battlefield to his mother:

I never saw in my lifetime the sight I saw. Our Company was sent out yesterday afternoon to berry the dead and we ware ought 2 hours and we berried 46 Rebles. We are encamp[ed] on the battle ground.

Patrick died facing Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg a year later. Another man who died in that regiment at that battle was James Hand. His friend, Derry native Charles McAnally- a future Medal of Honor recipient- broke news of his death to his widow:

Patrick died facing Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg a year later. Another man who died in that regiment at that battle was James Hand. His friend, Derry native Charles McAnally- a future Medal of Honor recipient- broke news of his death to his widow:

It is a painfull task for me to communicate the sad fate of your husband (my own comrade)…he received a ball through the breast & one through the heart & never spoke after. I was in command of the skirmishers about one mile to the front & every inch of the ground was well contested untill I reached our Regt. The Rebels made the attack in 3 lines of Battle, as soon as I reached our line I met James he ran & met me with a canteen of watter. I was near palayed [played] he said I was foolish [I] dident let them come at once that the ‘ol 69th was waiting for them. I threw off my coat & in 2 minuets we were at it hand to hand. They charged on us twice & we repulsed them they then tryed the Regt on our right & drove them, which caused us to swing back our right, then we charged them on their left flank & in the charge James fell, may the Lord have mercy on his soul. He never flinched from his post & was loved by all who knew him.

Sickness and disease killed more men than combat, and was a constant worry for both the troops and those at home. James McGinness, from Kill, Co. Cavan, was serving in the 90th New York Infantry when he wrote to his wife on 5 September 1862:

Thanks be to God my health is as good as it ever was and if you saw the hard life that we have to go through you would be astonished to think that men could live atall , but thanks be to God the whole Camp is in pretty good health, Still there are a good many encampments around here that have quite a number of deaths

Before long James’s encampment was also struck down- he died of yellow fever at Key West, Florida, less than a month after writing this letter, widowing his wife, who would also bury at least 7 of the couple’s 15 children.

Robert Boyle from Portadown, Co. Armagh, was serving in the 164th New York, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, when he was severely wounded at Cold Harbor in June 1864. Writing to his wife as a prisoner from Libby Prison in Richmond he told her:

Robert Boyle from Portadown, Co. Armagh, was serving in the 164th New York, Corcoran’s Irish Legion, when he was severely wounded at Cold Harbor in June 1864. Writing to his wife as a prisoner from Libby Prison in Richmond he told her:

My dear wife, I was captured on yesterday morning the 3rd near this place I am severely wounded through my right thigh. The surgeon has not yet examined my wound and I cant tell whether the leg will have to be amputated or not, I fear that it cant be done with safety…My dear wife I do not know what will be the result of this wound but hope for the best…With much love I remain your loving husband.

Robert died of his wounds while still a prisoner a little under a month later.

Such is the richness of some of the letters that we can combine them with other sources to build a much fuller picture of the lives of individual emigrant families, and I want to spend the remainder of the talk exploring two examples of this. The first is the story of James Kerr, from Co. Tyrone, a soldier in the 26th Pennsylvania Infantry.

We first encounter James at the First United Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, on 14 March 1857, where he married Jane Kennedy. James, who worked as a laborer, was 5 feet 7 ½ inches tall, with brown hair, grey eyes and a fair complexion. The couple made their home in Rodman Street, six doors below 13th street on the south side, south of Lombard. It was there that their first child, Agnes- known to all as Aggy- was born at 10pm on 8 April 1858. The difficulties inherent with childbirth so prevalent in the 19th century were visited on the family the following year. At 3am on the morning of 29 October 1859 their first son was stillborn, a result of his being born in the breech presentation. Thankfully, all went well with their third child, Samuel, who was born hale and healthy at 6.30pm on 3 January 1861.

James, who for reasons unknown decided to serve under the alias of “John Kerr”, first enlisted in the 26th Pennsylvania at the age of 22 on 5 May 1861. However, this first stint in the army appears to have been short-lived, as he was discharged due to “great deafness.” Further heartache became the Kerrs’ lot on 8 August 1862, when James’s wife Jane died. Apparently sparked by a need to obtain a regular income, James again sought to enlist that December, and was this time accepted back into his old regiment, apparently with no questions asked. It is in this context that we first encounter his letters, written to the Robb family, where his children were boarding. [SLIDE 14] On 31 January 1863 he wrote from Falmouth, Virginia:

James, who for reasons unknown decided to serve under the alias of “John Kerr”, first enlisted in the 26th Pennsylvania at the age of 22 on 5 May 1861. However, this first stint in the army appears to have been short-lived, as he was discharged due to “great deafness.” Further heartache became the Kerrs’ lot on 8 August 1862, when James’s wife Jane died. Apparently sparked by a need to obtain a regular income, James again sought to enlist that December, and was this time accepted back into his old regiment, apparently with no questions asked. It is in this context that we first encounter his letters, written to the Robb family, where his children were boarding. [SLIDE 14] On 31 January 1863 he wrote from Falmouth, Virginia:

Dear Friends,

Your kind letter of 27th came to hand this morning. I was glad to know you got the money, as I was much afraid from the delay you would not get it…as it regards those 29 dollars, if I live to put my time in it will be sure for me then along with my Bounty…Always remember me to the children also to your own family. All is quiet here at present we have snow a foot & half deep … Excuse the paper I have written this on it got dirty in my pocket.

The next letter was written on 28 March 1863. It would appear that his sister-in-law Margaret Kennedy and a Mrs Major were accusing James of not paying all the funeral expenses following his wife’s death, and their accusations were impeding the flow of relief money to his children. John wrote to the Robbs:

The next letter was written on 28 March 1863. It would appear that his sister-in-law Margaret Kennedy and a Mrs Major were accusing James of not paying all the funeral expenses following his wife’s death, and their accusations were impeding the flow of relief money to his children. John wrote to the Robbs:

I am very sorry you have so much trouble about the relief money. If I was able to pay for my children’s board without it I should not ask it at all, but this I am not able to do. I think it very hard for my children to be kept from getting what is their right, through the stories of persons who may wish to do me injury… it grieves me to think that any of them should try to injure either your character or mine. I would wish from my heart that this matter could be arranged, I have enough to perplex my mind without it, the duties of a soldier battling for his Country’s rights who knows not the day he may have to march on the enemy and face the music of the rifle and cannon…it is my wish that you should draw the relief money until I return again if I have the good fortune to escape the rebels ball & steel… Always remember me to the children. I hope Aggy is a good girl and has not forgotten me, tell me if she speaks as little as [she] used to do next time you write.

Access to the relief money still dominated James’s thoughts when he next wrote to the Robbs, on 18 April:

I am somewhat surprised you did not answer my last letter- It makes me fear you have not been successful in getting the relief money. Enclosed is a receipt for twenty dollars which you can receive on account for the children’s board, the Chaplin Mr. Beck will hand it over to you. We are about moving on the enemy we are each to carry eight days rations. We have been under marching orders for three days, we expect hot work before us, plenty of marching and fighting both…I am in good health and hope this may find my dear little children together with yourself & family well…please write soon when this comes to hand and give me all the news you can…

The movement he was referring to were the beginnings of a major campaign. Just over two weeks after writing, James Kerr was killed by a bullet at the Battle of Chancellorsville. His orphaned children would receive a minor’s pension based on his service, and their futures passed into the guardianship of their aunt Margaret.

The next letter-based story relates to the Carr family. They were natives of Ballinascreen, Co. Derry, where Arthur Carr and his wife Nancy lived with their five children. In 1850 Arthur died, leaving the family destitute and with few options. Nancy would later recall that in 1851:

The next letter-based story relates to the Carr family. They were natives of Ballinascreen, Co. Derry, where Arthur Carr and his wife Nancy lived with their five children. In 1850 Arthur died, leaving the family destitute and with few options. Nancy would later recall that in 1851:

“I and family were sent to America and our expenses paid by the local authorities in Ireland”

The family escaped penury in Ireland only to face paupery in New York. Not long after their arrival, Nancy was forced to place her children in institutional care due to an inability to afford their support. Improving circumstances eventually meant that she was able to reunite most of her family, but not all. An August 1860 “Information Wanted” advertisement placed in the Boston Pilot explained what happened:

INFORMATION WANTED OF BERNARD (or Barney) CARR, who left Ireland and landed in New York in 1851, with his mother and her children. Being unable to support them she was obliged to send three of the boys to Ward’s Island, from which place a person named Fenton Goss, from New Jersey, took one of the boys (Bernard, or Barney) to West Liberty, Logan county, Ohio. The unfortunate and disconsolate mother, who is now in certain circumstances, offers a reward of $20 to any person who can give her any information of her son Bernard Carr. Address Mrs. Ann Carr, Walton, Delaware county, N.Y.

Ann’s advertisement worked, but she did not reunite with Barney before the onset of war. By 1862, Barney, then 17-years-old, had made the decision to enlist. Almost certainly underage, he became a private in Company C of the 79th Illinois Infantry, and it is from here that we pick up his correspondence with his mother in New York. In an early letter, written in camp near Nashville, Tennessee, Barney asked his mother to:

pray for me continually I hope that you and me and the rest of the folks at home…see each other once more before I die. If it is the will of God that he may spare my life to get home to embrace my mother as we haven’t seen each other for about 9 years or more.

Life’s simple pleasures were important to Barney. This is demonstrated in a letter he wrote from Chattanooga, Tennessee on 14 November 1863:

Life’s simple pleasures were important to Barney. This is demonstrated in a letter he wrote from Chattanooga, Tennessee on 14 November 1863:

…Mother I want you to send me by mail one round of fine cut chewing tobacco just as soon as you can send it to me, for that is the only way I can keep from spending my money and if you don’t send me plenty of tobacco, why then you will have to send me my money to buy it [he was sending home $30] for I can’t do without the article in no shape nor form…as for tobacco you can buy me a number one quality there and not cost near so much as it would here, I have to pay $1.00 for one plug of tobacco and it won’t weigh half a pound and it is musty after I get it so that I can’t chew it.

The following summer saw the onset of the combined Union offensives which sparked some of the most horrendous fighting of the war. Barney and the 79th Illinois were involved in Sherman’s push towards Atlanta, which saw the regiment engaged in heavy fighting through May and June. On 20 June Barney wrote the following letter, penned while under Confederate fire at Kennesaw, Georgia:

Dear Parent, once more I take the pleasure [of] writing to you a few lines to let you know that I am still alive yet. As I suppose you are well aware that Sherman’s army has been a fighting ever since last May and that I am still in his army. So as I have not wrote to you in a good while I thought you would be uneasy about me and thought that I would write you a few and let…[the letter stops at this point, and continues as below]

Dear Mother I have had to stop writing, we are a lying on the line [of] battle and there are 12 pieces of cannons in front of us and they are a shelling the Rebs and that draws the Rebels fire and it is a horrible place to be in. Cannonballs are a flying thick around us and the shells are a screaming in the air and through the woods, cutting the timber and earth in all directions, but thank [God] Mother I am still safe and unhurt, but how long I may still remain so I can’t tell anything about that yet. God only knows how long it may last, I am sure I can’t tell anything about it now, that by the grace [of] God I still live yet and am well and hearty in the bargain…I hope that when this few lines reaches you that [they] will find you all well and doing well.

Dear Mother these are hard times nothing but fighting every day and killing of men. I am a getting tired of it but then I want to see them keep those Rebels a moving to Atlanta and I guess that it is the only way of putting down this Rebellion and the sooner it is down the better it is for them that lives to see it. But Mother pray for me that I may live to see it over and live to see you all. So Mother I want to see you before I die and I want to see all of the Carr family.

Seven days after Barney Carr wrote this letter, on 27 June 1864, Sherman ordered his men to assault the Confederate line at Kennesaw Mountain. In the bloody repulse that followed, the assisted-emigrant from Ballinascreen was killed.

The story of the Carr family is one of a number from Ulster that will feature in my new book, The Forgotten Irish, which is due out this November. Each of those stories draws on the incredible information contained within the widows and dependent pension files to try and reconstruct the Irish emigrant experience at the level of the individual family. This is something that is possible with thousands of Ulster files. Heretofore, we have spent too long concentrating on the ins-and-outs of questions such as the location of Phil Sheridan’s birth, or the degree of Stonewall Jackson’s Ulster-Scots identity. The real story of Ulster in the American Civil War is one for which we have barely scratched the surface. It is the story of ordinary emigrants like James Kerr and Barney Carr, and the tens of thousands of other Ulster families who were irreparably touched by this conflict.

The story of the Carr family is one of a number from Ulster that will feature in my new book, The Forgotten Irish, which is due out this November. Each of those stories draws on the incredible information contained within the widows and dependent pension files to try and reconstruct the Irish emigrant experience at the level of the individual family. This is something that is possible with thousands of Ulster files. Heretofore, we have spent too long concentrating on the ins-and-outs of questions such as the location of Phil Sheridan’s birth, or the degree of Stonewall Jackson’s Ulster-Scots identity. The real story of Ulster in the American Civil War is one for which we have barely scratched the surface. It is the story of ordinary emigrants like James Kerr and Barney Carr, and the tens of thousands of other Ulster families who were irreparably touched by this conflict.

Filed under: Antrim, Armagh, Cavan, Derry, Donegal, Down, Fermanagh, Monaghan, Tyrone Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Mellon Centre Migration Studies, Scots Irish Emigration, Ulster American Folk Park, Ulster Catholic Emigration, Ulster Emigration, Ulster Presbyterian Emigration, ulster-American Heritage Symposium

June 16, 2016

“I Sprung from A Kindred Race”: George McClellan Cultivates the Irish Vote, 1863

The Irish of the North overwhelmingly supported the Democratic Party during the period of the American Civil War. Many had little time for Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans, and in the 1864 Presidential Election most rowed behind George McClellan– the former commander of the Army of the Potomac– who was hugely popular among the Irish. Though his Democratic affiliations made him the natural choice for many Irish, McClellan nonetheless had put work into endearing himself to them. One such occasion was his appearance at a meeting in 1863, organised to raise funds for the relief of the poor of Ireland. McClellan no doubt saw this as an ideal opportunity to garner significant Irish support. His speech that evening is reproduced in full below, as is an explanation from one Irish Legion voter as to why he intended to support McClellan in the 1864 Election.

George McClellan and his wife during the Civil War (Library of Congress)

The speech below was given at the Academy of Music in New York on 7th April 1863. The event had been organised in an effort to raise funds for the relief of the poor of Ireland (to read more on these efforts, see posts here and here). The New York Times described the event as follows:

At half-past 7 o’clock the entire edifice was filled with beauty and fashion. On the stage were the officers of the Society known as the Knights of St. Patrick; Mayor Opdycke, who presided over the meeting; His Grace Archbishop Hughes; Rev. Messrs. O’Reilly, Mooney, Schneider, Hon. Judge Daly, Hon. Recorder Hoffman, Brig. Gen. Meagher, Very Rev. Dr. Starrs, Vicar General;Rev. Thomas Quinn, of Rhode Island, Rev. Mr. Moran, of Newark, Mator Kalbfleisch, of Brooklyn, and several other distinguished gentlemen, both of the lay and clerical orders. (1)

The evening wasn’t just for Democrats– Mayor Opdyke, who was also in attendance, was a staunch anti-slavery Republican. Among the other speakers was Thomas Francis Meagher, who although a Democrat, would ultimately support Abraham Lincoln in 1864. Though “Little Mac” protested that he had not intended to speak at the event, he had undoubtedly intended to do exactly that. His speech, which by all accounts was extremely well received, was calculated to link himself still further to the Irish. McClellan spoke of springing from a “kindred race,” and of witnessing the bravery of Irish soldiers on the battlefields of Mexico and the Civil War. He went as far as could reasonably be expected in condemning the British position in Ireland, pointing out that the Irish were little represented in the Government of Ireland and had no influence on the laws of the land. One can imagine what the expression of such views meant for those in the crowd with designs on gaining American support for Irish independence. He accentuated the idea that the United States had become a refuge for Irish exiles, stoking Irish pride by noting what a boon this had been for America. He closed by taking the opportunity to espouse the cause of Union, and the importance of the current fight. It would be more than a year before “Little Mac” would receive the Democratic nomination to challenge Abraham Lincoln, but, as his speech below demonstrates, he was already preparing the groundwork for Irish support in his future political career.

The Academy of Music was an impressive venue. This was the Russian Ball held there, only a few months after McClellan’s speech, in November 1863 (Library of Congress)

MY FRIENDS: I came here to-night as a listener and spectator, not as a participant in the proceedings of the evening. I came to hear the ablest and best of the friends and sons of Ireland plead her cause to-night. I have departed from my usual rule to avoid large assemblies, because I knew that this meeting had neither partisan nor political purpose. [Cheers.]

I knew that you had assembled for the noblest of all purposes– that of charity towards suffering brethren in a distant land. I came here simply to evince my sympathy in your cause; for I have strong and peculiar reasons for feeling an intense sympathy for and interest in all that relates to Ireland and the Irish [great applause.] I sprung myself from a kindred race. I have often seen the loyalty of the Irish to their Government and to their General proved. I have seen the green flag of Erin borne side by side with our own Stars and Stripes through the din of battle [Cheers.] I have witnessed the bravery, the chivalry, the devotion of the Irish race, while I was a boy, on the fields of Mexico, and in maturer years on the fields of Maryland and Virginia [Loud cheers] It has often been my sad lot, pleasant withal, to watch the cheering, smiling patience of the Irish soldier while suffering from disease or ghastly wounds; and I have ever found the Irish heart warm and true. [Cheers]

I feel, then, that I have a right to sympathize with your cause to night. It is most unfortunate that there are so many in Ireland who need our sympathy; but at least we should thank our God that He has given us the means to extend our hands to them. [Enthusiastic cheering.] It is perhaps unfortunate for Ireland that laws, in the making of which the Irish have had but little to do- that a Government in which perhaps they been but little represented- should have induced so many to have left their native land and sought foreign climes. But what has been the loss of Ireland has been the gain of America [Cheers] It has given us some of the proudest intellects that have adorned our history, countless strong arms who have developed our resources, and soldiers innumerable, who, on every field, from those of the Revolution to those of the present sad rebellion, have upheld the honor of their adopted country. [Wild Cheers] And so, I repeated, we have gained what Ireland has lost. [Continued cheers]

One thing more before I close. Although, as I said before, we have come here to-night for no political purpose, yet no true friend of his country, in the present crisis, can repress altogether the thoughts that will crowd upon his brain. What is it that enables us now to extend our hands in succor to your brethren across the Atlantic? What is it that our fathers worked for, and for which we too worked, and are working now? It was to establish on this broad continent one nation, one free Government, that might be a refuge for all from foreign lands. I know, then, that I express the sentiments of all who listen to me when I say that all oue energies, all our thoughts, all our means, and, if necessary, the last drop of our blood, must be given to uphold that unity, that nationality. [Great cheering]

I did not rise to make a speech, but simply to express my warm and most cordial thanks for the greeting with which I have been honored. I will therefore thank you again, and then make way for abler and more eloquent men who will plead the cause of your country to-night. (2)

‘Irish Brigade Giving to the Cause of Ireland’, for which McClellan was speaking. Detail from New York ‘Irish World’, 1903

When the election finally did arrive in 1864, many Irish were extremely vocal in their support for McClellan’s efforts. This widespread support is borne out among the private letters of soldiers I have been studying in the widow’s and dependent pension files. To gain a sense of some Irish views you can see previous posts here and here. A letter published in the Irish-American of 22nd October 1864 is illustrative of Irish backing for McClellan. It was written by Captain Thomas Norris of the 170th New York Infantry, part of Corcoran’s Irish Legion. At the time of his writing the Killarney, Co. Kerry native was in hospital in Annapolis, recovering from a wound received at Petersburg on 16th June 1864. Norris was best known in later years for his efforts to preserve the Irish language, which have been featured in a previous post here. Norris was replying to a letter from a (presumably Irish) Sergeant about the election, and particularly to a comment that all of the officers would vote for “Old Abe and the niggers”, highlighting how many Irish felt about Lincoln, African-Americans, and emancipation. It is worth noting that these views did not prevent men like this unnamed Sergeant from wanting to return to his regiment, and to fight for a Government which by this date had made clear its intent with respect to emancipation. Like many Irish troops, he likely felt emancipation was a means to an end in the goal of preserving the Union, which was the strongest ideological motivational factor for Irish (as for native-born) troops. (3)

Democratic Party Poster for the 1864 election supporting McClellan and Pendleton (Image via Wikipedia)

OFFICER’S HOSPITAL, MIDDLE DEPARTMENT, ANNAPOLIS, MD., Oct. 4, 1864.