Damian Shiels's Blog, page 29

September 1, 2016

‘Ireland at the Diggings’: The Irish of the California Gold Rush Celebrate Home, 1853

This site regularly explores aspects of the 19th century Irish emigrant experience in America beyond the Civil War. One of the most popular themes is the subject of the Irish in the West. Among the many topics touched upon have been The Voices of California’s Irish Pioneers, St. Patrick’s Day in the ‘Wild West’ and the experiences of an Irish Silver Miner in Nevada, 1864. I recently came across a wonderful account of how a group of Irish participants in the California Gold Rush celebrated St. Patrick’s Day, 1853, at their remote mining encampment of Bullard’s Bar on the North Yuba River. The letter describes the day and night’s entertainment, as the all-male community sought to take a break from the hardships associated with prospecting for gold. The account offers an opportunity to explore what it was like to be a miner here during the Gold Rush, and also to ponder just how harmonious relations really were between the different groups– natives and newcomers– who flooded into early California.

A 49er on the American River, California (History of the United States)

The Irish miners who are the subject of the account were working claims at Bullard’s Bar, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. The location had got its name from a New Yorker, Dr. Bullard, who had struck it rich there in 1849, when he and three colleagues dammed up the river and extracted $15,000 of gold in less than two months. Today Bullard’s Bar no longer exists, as the area was inundated by the formation of the New Bullard’s Bar Reservoir, created by the construction of the New Bullard’s Bar Dam that opened in 1969. Although now much changed, it remains possible to gain a sense of what the mining settlement was once like in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Carl Wheat left a description of the challenging terrain these men inhabited in Northeastern Yuba County:

The general contour of the ridges suggests an old plateau, slightly tilted to the west, greatly cut away by erosion during recent geologic times. The Yuba River and its many branches have cut deeply into this old plateau, its gorges being from five hundred to over a thousand feet in depth…The “bars” were located along the rivers, with mountains towering up on both sides. The other towns and “diggins” were generally located on our near the tops of the highest ridges, where the miners discovered the rich, gold-bearing gravels left by the rivers of earlier geologic ages…It is a heavily wooded country, and to become lost was, and is, very easy, if one were to leave the beaten paths… (1)

The New Bullard’s Bar Reservoir, California, which today inundates the 1850s mining settlement (Photo by Justin Smith, Creative Commons)

What of the experiences of the men who worked Bullard’s Bar? One of them was Scottish 49er William Downie, who worked his first gold claim at Bullard’s, and left behind a recollection of his time there:

…we bought a rocker for twelve and one-half ounces [of gold], and now we stood at the gate that should lead us into the promised land. It seems strange now to think back upon our first experience in trying to find gold, and the primitive manner in which we went to work. The three of us divided the labor, so that one worked the rocker, while the other stirred, and the third used the pick and shovel and carried the dirt in a bag, about a panful at a time. I honestly believe that I could now run one day’s work through in one hour, pick, shovel, rocker and all. We used a scoop about the size of a cigar box for wetting the dirt. It had a long handle to it, and when the water was thrown on the dirt it would be stirred up, a process somewhat similar to making mush. (2)

Miner’s could be friendly enough to one other– as evidenced by the letter to come– but gold was gold, and they tended to be extremely secretive about their claims. In his early days, this was something that Downie struggled to understand:

There was one thing…which caused me a good deal of trouble and considerably puzzled my imagination. It was the mystery with which the miners surrounded all matters appertaining to prospecting. One man in particular put my patience to a test in this regard…while he would converse with me freely on all other matters, as soon as I asked him for any information in regard to finding gold, he became as dumb as the proverbial clam… (3)

An 1850 advertisement for passage to California and the Gold Rush (Nesbitt & Co Printers)

This experienced miner went on to give him some Downie some sage advice:

“Look here young fellow,” he said, “if there is a thing a miner don’t care to talk about, it is where he has been, and you might say that it is just as good as law among prospectors, that every man keeps mum. Let me give you a bit of advice: When you get to feel that way yourself; that you have struck it rich in a new prospect, don’t you advertise your good luck and have a band playing outside your tent to celebrate; but after sundown, when everything is settled in camp, and your nearest neighbor is snoring loud enough to compete with a cathedral organ, you just pack up your traps on your back and skip out of camp; and if you should meet anybody on the road, who should ask you where you are going, just tell them that you have had poor luck and are making back for town. But the next morning, bright and early– or as soon as you can reach it– stick your pick into your new claim and work it for all it is worth, before anybody comes to interfere with your happiness.” (4)

This gives some flavour of the environment in which the Irish miners at Bullard’s Bar worked in 1853. However, all potential rivalries were apparently forgotten on St. Patrick’s Day that year, when the small community got together to celebrate the feast day of Ireland’s patron saint in the wilds of California. The events so impressed one participant– apparently a native-born Anglo-American– so intensely, that he took up his pen to write to the New York Irish American Weekly of the occurrences, thus preserving in detail a fragment of these men’s lives.

The North Yuba River at Downieville, as it appeared in the 1930s (Historic American Building Surveys of California)

ST. PATRICK’S DAY IN CALIFORNIA

IRELAND AT THE DIGGINGS

To the Editor of the Irish-American

Bullard’s Bar, Yuba Co., Cal.,

21st March, 1853

MR. EDITOR- By the request of some of the sons of Erin, who have located themselves temporarily in this part of California, I embrace the first leisure I have had to give you some account of St. Patrick’s Day in California. This duty would undoubtedly have been performed by an Irishman, but from the fact that none of them have the same leisure that, on account of the nature of my business, I can command. But though I am an American born, such a task will not be unpleasant to me if I can succeed in doing such justice to the occasion as will satisfy the gentlemen who relieved the monotony of life in the gold mines by kindly permitting me to share with the convivialities of the 17th inst. And if I fail in this, it will not be from any want of sympathy with the occasion, or with the nation to whom that day is sacred.

Yes-sacred. The temptation is strong, for men who know that the loss of a mining day is the loss of no small quantity of gold, to pass by the present observance of such an occasion, and have the celebration of “St. Patrick’s Day” to the expected future, which will permit them to enjoy it among the friends and kindred so many of them have left to make their fortunes out of the golden sands of California rivers. I imagined that the principal difference between St. Patrick’s Day on Bullard’s Bar, and other days, would be that some would have better dinners on that day than usual, and perhaps an additional glass or two of liquor. But I was underrating Irish hearts.

On the morning of the 17th inst,. we were awakened by the early discharge of fire arms, and the tune “St. Patrick’s Day in the morning” played upon every instrument procurable among us. At an early hour those Irishmen who having entire control of “the claims” upon which they work, could do as they chose, might be seen revelling in the luxury of clean shirts (an article somewhat more rare here than with you) and wearing bunches of shamrocks in their hatbands, intent upon the enjoyment of their traditional holiday.

The day passed off quietly and pleasantly. Everywhere the frank good-humored countenances of Irishmen were seen, and their voices were heard in such a way as not only proved their appreciation of fun, but also that the popular faith in Irish wit is no illusion.

Duncan Ross Cameron performs “St. Patrick’s Day”, which sounded around the Sierra Nevada foothills on the North Yuba River on 17th March, 1853

So quickly had all the arrangements for the evening been made, that but few were aware that anything unusual was to take place, and none suspected that it was to prove quite an era in the social history of our little community. But soon after the usual time for supper, notice was given that the anniversary was to be observed in the house of Messrs. McKeon (from the State of Vermont) where men of all lands would find open doors and warm hearts to receive them. A majority of the population of our little place eagerly availed themselves of this general invitation, and soon, in a small room, were assembled the representatives of many countries. Germans, Danes, Norwegians, English, and native-born Americans- united by a common citizenship, forgot, if they had ever known such, all former prejudices, and heartily joined with their generous Irish hosts in everything which was done to make the occasion what it should be.

I wish that I could describe that room so vividly that your readers might see it as in a daguerreotype. I have said that it was small. Its actual dimensions had better not be given, lest it should seem impossible to your city readers that it would contain so many as thirty or thirty-five men, and yet afford spare room for what remains to be described. But the benches around the sides were crowded, the bunks in the corner afforded perching places for more than one would believe- even the large fire-place allowed two or three breathing room, and now and then they could change places with some one more fortunately located. One corner of the room was occupied by a table, upon which was a large supply of eatables and drinkables, free for all to use as they chose. When I entered the room, all of the floor not occupied by what I have named was covered by dancers, who entered into the thing with a spirit which more than atoned for all inconveniences and want of elegance in the room itself. A gayer, happier set of men were never met. (There are no women here). If the gentlemen who lazily daudle through the figures in elegant ball rooms- incapable o being warmed into a hearty activity even by sympathy with their fairer and gayer partners, could have looked on for half an hour, they would have found great reason to doubt the reality of their own existence, and must have envied the men they looked at.

After a little dancing, glasses were filled and toasts were given which did credit to Irish heads, and received in a manner worthy of Irish or of any hearts. I regret that it is impossible for me to repeat these toasts. I have spoken of the contrast between a ball in “high life” and the dancing on Bullard’s Bar, on the evening. I must also speak of the contrast between the sentiments given and the spirit in which they were received, and the same thing as it is “got up” for the great dinners, first heralded, and afterwards ably reported in the newspapers. In cases of the latter kind, more skill and ingenuity may be displayed- but oh, how much less heart! Be it ever so well done the toast of such a dignified occasion smacks of thought and study; and how much the enthusiasm of its reception usually falls short of that of its eloquent manufacturer, who read it over as often in his study the night before, indulging himself in the belief that he would “make a hit” and “call down the house.” Here every toast came gushing from a warm and manly heart- the simple expression of a real feeling which throbbed in the heart, and it would be received in such a way that proved that other hearts were warm and true- full of all manliness. So beautifully was Ireland remembered- so delicately and touchingly spoke on- that he who could listen without feeling sympathy and admiration for Irish character, must have been made of strange material.

Gold Miners in El Dorado, California, during the Gold Rush (Library of Congress)

And our America was toasted. It made my heart beat with gratitude that I was born in a country which had such love from such a people, and such must have been the feeling which dictated a toast offered with evident sincerity from a native American, who gave “The native American Party- let us thank God that it is dead and buried, and pray that it may know no resurrection.”- This toast would scarcely have been relished by the Irish, I think, if it had been given by an Irishman, so carefully did they refrain from anything which by possibility could injure any man’s feelings. But coming from a native it was received with three times three, and cheered as well by natives as by others. Then came a song- Mr. Thomas Drennan sang the adventures of himself and his “beautiful stick” in a glorious style, which made every man laugh until his ribs ached. Again came dancing, better, gayer, livelier than ever. Jigs and waltzes and polkas and cotillions, as the dancers happened to be of one or another nation. An old gentleman, Mr. Sullivan, senior, who had looked quietly on, though evidently enjoying the scene, now rose and claimed a young Irishman for a partner, and fairly outdid him in an Irish dance. It was good to see that venerable old man retaining the enthusiasm of his youth, and forgetting the weight of years under the impulse of patriotism.

Others ought to be mentioned for their contributions to the general enjoyment. Mr. Hugh Shirkland gave a toast, the words of which I cannot quite recall, which claimed for the Irish undying love for their native land, and unswerving attachment to their adopted home. Messrs. Karrigan, McMenymie, Sullivan, jun.; Gillans, (who made a very pretty speech, concluding with appropriate sentiment) McGuire, Sweeney, and others, ought to be mentioned for their several parts in the evening’s history, but to so minute will tax your columns too much.

A Dr. Lippincott–an Illinoian– having engaged quite heartily in the evening’s ceremonies, Mr. Drennan suddenly made it the point of some complimentary remarks, and hoped the company would express some thanks for the kindness and attention which the Dr. had shown. This called forth a burst of applause in the way of cheers for the Dr. which must have gratified any man. Dr. Lippincott hastily threw his cap under a table, and said that he had expected no such tribute, and was unconscious of having deserved it. If he had been able in any degree to contribute to the evening’s enjoyment, he was glad and proud of it–for he would desire to render some small return for the pleasure he had enjoyed. “If” said he, “I were in Ireland with a company of Americans, and if, instead of St. Patrick’s Day, it was the Fourth of July, and our little company should (as they certainly would) try to celebrate that day, it was not credible that we should call in vain for aid or sympathy with Irishmen around us. Believing this, it would indeed be shameful to stand alone when Irishmen who have become my countrymen, attempt to observe a day so dear to every Irish heart. No, gentlemen, when on the 17th day of March an exiled Irishman stops from his customary pursuits to remember the home of his birth, the sadness which must mingle with his memories, shall not, if I am by, be deepened for want of American sympathy. I have read, from my childhood, something of Ireland’s story, and can honor the great men she has produced, whether they have died upon the scaffold like Emmet, or been exiled like Meagher. Let the world remember Ireland, if only in gratitude for the glorious men she has borne– men whose influence could not be confined to Ireland, but extends to every warm, free heart that beats upon the world. There are others here who are far from their native land, and before all, and to all, I say, thank God that you have come. As an American I am more than proud that my native land can cherish the oppressed of all other lands. As an American I rejoice in the belief that from the mingling of so many races will be produced a future generation of American men which will surpass any race which the sun ever shone upon. But to Ireland does this occasion belong, and only Ireland, would I now speak of. America has willingly received her exiled sons– but all over our land are the evidences that they were worthy to become American citizens. Every canal and railroad, every bridge and turnpike is a trophy of Irish industry and monument of Irish worth. The Irish– like all men have their faults, but everywhere, as laborers, as citizens, as congressmen, and as soldiers, they have proved themselves equal to the best and so may God send millions more of them to this country!”

In reply to this came new cheers, and then once more the dancing began. It would be an outrage to protract my letter so long as the festivities were, for day was peeping over the mountain-top before the party separated. When that time came every man was as gay and happy apparently, as in the early part of the evening. Though all night liquors of all kinds were plenty as water, not one man was drunk, and nothing appeared to corroborate the general opinion in regard Irish combativeness.

I reckon St. Patrick’s Day, 1853, as one of the bright days of my life, and indulge the hope that on some return of it I may again be permitted to partake of Irish hospitality.

YUBA. (5)

A Hupa Fisherman in California, photographed in the 20th century. The Hupa were one of the Californian tribes terribly impacted by the Gold Rush (Library of Congress)

‘Yuba’ presents apparently harmonious relations between the men at Bullard’s Bar (at least for a day), but it is worth remembering that this was not necessarily the case when it came to those viewed as others. The Gold Rush had a particularly devastating impact on California’s Native American peoples, whose population was almost wiped out as a result. Other groups such as Mexicans, Chinese and Pacific Islanders were also sometimes targeted. William Downie recalled one occasion at Bullard’s Bar in 1849 which demonstrated how the miners– including Irishmen– were prepared to defend what they had taken:

At Bullard’s Bar some of the singular scenes of miners’ camp life in those days began to unfold themselves to me, and here, for the first time, I saw a party organized for the purpose of driving away “Foreigners”. What was implied by the term “foreigners” was not exactly clear to me at that time, and it would be hard for me to explain it even now. The little company so organized, consisted of from twenty to thirty men. They were armed with pistols, knives, rifles and old shotguns, and I remember distinctly that they were headed by a man who carried the stars and stripes in an edition about the size of an ordinary pocket handkerchief…I took the opportunity to ask one of the men, where they were going, and for what purpose. In reply I was told in tip-top Tipperary brogue, that the expedition had set out for the purpose of exploring the river thirty miles up and down with a view to driving away all “foreigners.” The crowd was a motley one, and as to nationality, somewhat mixed. Irishmen were marching to drive off the Kanakas [Hawaiians], who had assisted brave Captain Sutter…They were joined by Dutchmen and Germans, who could not speak a word of English…Then there were a few New Yorkers…but all joined hands in the alleged common interest or protecting the native soil…against the invasion of “foreigners.”

There are undoubtedly many dark undertones to Irish participation in the march of Manifest Destiny across the United States of America that should be fully acknowledged. However, as I have discussed elsewhere, adopting a nuanced approach to the history of the Irish in the West is also required. ‘Yuba’s’ account provides us with a glimpse of just how important remembering home was to Irish emigrants, even as they followed a harsh lifestyle a world away from the towns and countrysides where they had originated back in Ireland. As ‘St. Patrick’s Day in the Morning’ rang out around the foothills of the Sierra Nevada’s many men’s thoughts must have turned to the country and family they had left behind.

(1) Swindle 2000:41, Douglas 2002: 578; (2) Downie 1893: 19-21; (3) Ibid., 23; (4) Ibid., 24; (5) New York Irish American Weekly; (6) Carrigan and Webb 2013, Downie 1893: 21-22;

References

New York Irish American Weekly 7 May 1853. St. Patrick’s Day in California. Ireland at the Diggings.

Carrigan, William D. and Webb, Clive. 2013. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928.

Downie, William. 1893. Hunting for Gold: Reminiscences of Personal Experience and Research in the Early Days of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to Panama.

Kyle, Douglas E. 2002. Historic Spots in California.

Swindle, Lewis J. 2000. The History of the Gold Discoveries of the Northern Mines of California’s Mother Lode Gold Belt.

Justin Smith Wikipedia Image Page.

Filed under: California Tagged: Bullard's Bar, California Gold Rush, Irish 49ers, Irish American Civil War, Irish in California, Irish in the Gold Rush, Irish in the West, Irish Miners

August 25, 2016

‘Beyond the Power of My Feeble Pen’: The Fate of a Limerick Octogenarian’s Sons in the West, 1862

Limerickman Patrick Vaughan had lived a long life by the 1860s. He was born sometime around 1783, the year that the conflict between the American Colonies and Britain had finally drawn to a close. When rebellion broke out in Ireland and French troops marched to their support in 1798, Patrick was a teenager. He was in his early twenties when Napoleon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor in 1804, and in his thirties by the time the ‘Little Corporal’ had his last hurrah on the battlefield of Waterloo. There are many details we don’t know about Patrick Vaughan’s life, but there is no doubting the momentous times he lived through. However, it seems unlikely that anything impacted him quite like events that took place in Tennessee and Arkansas in the spring and summer of 1862. By then in his eighties, it might have been expected that he had survived the worst life had to throw at him. But he had not reckoned on the escalation of the American Civil War in the Western Theater, and the extreme personal loss the fighting there would bring. (1)

One of Fort Donelson’s River Batteries, Tennessee (Hal Jesperson)

Patrick Vaughan and his family are not easy to track in the historical records, and efforts to locate them in the census and passenger lists have yielded little. Despite this, there are a number of things we know about their story. Patrick married Mary Long in Co. Limerick sometime around the year 1839. Patrick was many years Mary’s senior and was likely in his mid-fifties when they wed. The couple’s sons John and Patrick Junior were both born in Ireland, John around 1842 and Patrick about 1843, and they also had at least two– probably at least three– daughters. Honora appears to have been the youngest in the family, and was still a child under 16 in 1862, by which time Mary was married to a man called Norrish in Pennsylvania. It seems highly likely that the family was in fact much larger– for example, another potential sister, Margaret, is referred to in family correspondence. The date of the Vaughan emigration to the United States is unclear, but was probably in the late 1840s or early 1850s. Mary, the matriarch of the family, died around 1854. This may have occurred after the family came to America, where they seem to have initially settled in Buffalo, New York. It was from there that Patrick’s two sons enlisted in the Union military at the coming of the American Civil War. (2)

The first of the Vaughan boys to march off to the conflict was the elder, John. He was still listed as a resident of Buffalo when he enlisted on 15th July 1861 at Saxon, Illinois. He was described as 19-years-old and 5 feet 10 inches in height with brown hair, blue eyes and a dark complexion. By trade John worked as a printer. On 20th July he mustered in as a private in Company B of the 11th Illinois Infantry at Bird’s Point, Missouri. His younger brother Patrick Junior followed him into the army a few months later. He was 18-years-old when he enlisted in Buffalo on 2nd September 1861, mustering in the following day as a private in Company D of the 49th New York Infantry. Patrick did not remain with the 49th for long, as he was earmarked for service with the Western Gunboat Flotilla. Duly transferred, by 1862 he was serving as Seaman aboard the ironclad gunboat USS Mound City. (3)

The USS Mound City, on which Patrick Vaughan Junior served (Naval History and Heritage Command NH72806)

Meanwhile John had been writing home to his elderly father. The first letter that survives was written on 10th January 1862 from Bird’s Point, Missouri, where the 11th Illinois were encamped. As was (and remains) common, John had accidentally labelled the letter 1861, given how new the year was.

Camp Lyon, Bird’s Point, Mo, January 10th 1861 [sic.]

Dear Father:- I received a letter from Maurice Vaughan last Saturday stating that you were disabled by rheumatism and that you were dependent on the poormaster for support. I have delayed answering it until the present time in the hope that I would get paid off, so that I would be able to relieve your wants. We have not got paid off up to date, and all the troops here, are all fixed up for a march the wagons are all packed, and the boys are all fixed up for it. There is a rumor now in camp that we will get paid before starting. If we do, I will send you ten dollars immediately, and I am going to send the same amount to Margaret as I have received a couple of letters from her. I have written to Patrick requesting him to do all he can for you. I think this expedition is bound to take Columbus as it will compose about 7 seventy five thousand troops. I have been sick for the last two weeks and this morning the doctor told me not to go, but I am bound to go though I have to disobey doctors orders. I will direct the package in care of Maurice Vaughan. I have nothing more to say at present but hope you will enjoy good health.

From your affectionate son,

John Vaughan. (4)

Patrick Vaughan had remained in the workforce despite his advanced age, but bouts of rheumatism were affecting his ability to earn a living, forcing him to rely on charity. With two sons in the army, the erratic nature of their pay must have hampered their efforts to support him, as John’s letter indicates. John’s determination to go on the mission from Bird’s Point also demonstrates a strong motivation for service, reflected in his early enlistment date. Three days after writing, John did indeed move out on an expedition towards Columbus, Kentucky. By the time of his next letter, written ten days later, he was back Bird’s Point:

Camp Lyon, Bird’s Point, Jan 20th/62

Dear Father:- I sent you my likeness a week ago, with ten dollars enclosed in it in care of Maurice Vaughan. I sent you a letter the same day also. I hope you have received them by this time. In the letter I informed you of our going on a march the next day. We went on the march, and returned this afternoon, after an absence of six days. We had a hard time of it, as it was either raining, snowing, or thawing the whole time. We had to march through mud and [illegible] over knee deep, but the boys did not care for that, as we all thought we would have a fight. We were doomed to disappointment however, and the only grumbling the boys done was when we were ordered to return to our old quarters. The expedition went out the Columbus and Bowling Green railroad, burned some bridges, and destroyed several miles of the railroad, so as to keep the enemy from reinforcing them at that latter place, and battle is expected there every day. Before starting, I bought myself a pair of boots for five dollars, an I got my moneys worth out of them on the one trip. I sent twenty dollors to Margaret in a likeness the same day I sent yours. I also sent a likeness to Patrick. I would like to have your likeness as soon as convenient. I will do all I can for the whole of you, and none of you will want to for anything while I have a cent. I have written several letters to Patrick urging him to do all he could for you. I would like to have you write often, as nothing will raise the drooping spirits of a soldier quicker than to receive a letter from those he holds dear to him. We have a good time here, but I hope this war will soon be over, so that I can again go to work at my trade. There is nothing of interest going on here at present, so I will bring my letter to a close as it is now getting late.

From your affectionate son,

John Vaughan.

Direct your letter to,

John Vaughan

Co B, 11th Regt, Ill. Vol.

Bird’s Point, Mo. (5)

John and his comrades went on another brief sortie between 25th and 28th January, before embarking on transports on the 2nd February – twelve days after the above letter– for one of the key campaigns of the war. They were part of the force Ulysses S. Grant was taking to subdue the Confederate positions of Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Fort Henry fell on 6th February without the infantry being seriously engaged, but it would be a different story at Fort Donelson, located twelve miles away. The Union troops moved into position around the Fort on 12th February, with John and the 11th Illinois forming part of W.H.L. Wallace’s Brigade in McClernand’s Division, holding the right of the line. They were still there three days later, when the Confederate defenders in the Fort decided to target their sector in an attempted breakout. The 11th Illinois were attacked from front and flank, and even had to contend with cavalry in their rear. They, like the majority of McClernand’s men, were forced to retreat. Though the route for Confederate escape from Donelson lay open, they inexplicably failed to take it, and retreated back into the Fort, where they would ultimately be forced into an unconditional surrender the next day by Ulysses S. Grant, as he began to build the reputation that would see him become the conflict’s leading General. But it was a victory that had come at a staggering cost to the 11th Illinois. The regiment had brought in the region of 5oo men into the fight at Fort Donelson, suffering a shocking 330 casualties. John Vaughan was one of them, wounded by a gunshot. He died on the hospital transport ship City of Memphis, either on the 18th or 21st February (though one report suggests he may have survived until landing in Paducah, Kentucky). (6)

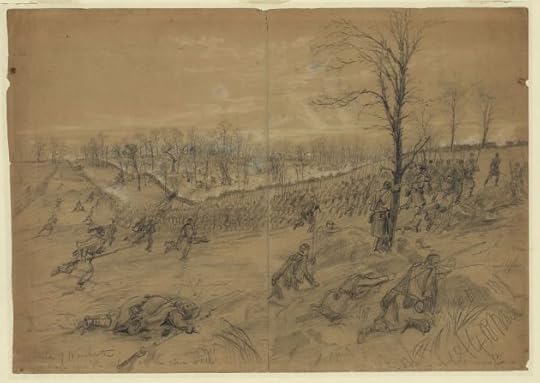

Seeking Union wounded on the field at Fort Donelson. Limerick’s John Vaughan was one of those who fell injured there. (Library of Congress)

Patrick Vaughan had lost his older son. His younger son Patrick Junior–the seaman in the Western Gunboat Flotilla– likely only missed the action in which his brother was mortally wounded because the USS Mound City was not employed with the other boats of the Flotilla in the engagement. He was probably with her at Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River in March, and was heavily engaged at Plum Point Bend on the Mississippi in May, when she was very heavily damaged. The next action for Patrick Junior and the Mound City came as part of the White River expedition in June 1862. The aim of the expedition was to bring support up the White River to Union General Samuel Curtis’s troops operating in Arkansas. On 17th June the expedition encountered Confederate batteries at St. Charles, Arkansas. After disembarking troops to attack the position from land, the USS Mound City and the rest of their flotilla headed upstream to engage from the water side. Lieutenant McGunnegle, of the USS St. Louis, described what happened next:

The moment we discovered the situation of the enemy’s battery the cannonading from our side became terrific. In a few moments the Mound City had advanced to within about 600 yards of the enemy, when a well-directed shot from a new battery situated a little higher up the bluff penetrated her port casemate a little above and forward of the gun port, killing three men in its flight and exploding her steam drum. So soon as this sad accident occurred many of her crew leaped overboard; all boats were instantly sent to her relief…The Mound City drifted down and across the stream. The Conestoga boldly came up and towed her out of action…the enemy shooting all the while at the St. Louis and the wounded of the Mound City struggling in the water…Our victory was a complete one, but the loss of life on board the Mound City by the explosion of the steam drum is frightful…to endeavor to describe the howling of the wounded and the moaning of the dying is far beyond the power of my feeble pen. (7)

The interior of a sanitary steamer, similar to the ‘City of Memphis’ on which John Vaughan breathed his last (Naval History and Heritage Command NH58897)

The horrific scalding death caused by steam explosions aboard Civil War vessels were among the most feared in the naval service. Bearing witnessing to such events also left an indelible mark. Only two of the Mound City officer’s survived unscathed, and it was remarked that one of them– First Master Dominy– had to be sent back to Memphis, as ‘having witnessed the terrible catastrophe, his mind appeared to be greatly exercised.‘ Aside from those who died a horrible death on board, Lieutenant McGunnegle also believed that ‘many, very many, must have been killed by the enemy while struggling in the water.‘ The loss of life was truly astonishing. No fewer than 103 of the crew were killed, with many more severely wounded. Unsurprisingly given their high service rates in the Union Navy, many Irish were among them. One was Patrick Vaughan Junior. Whether he had died in agony engulfed by scalding steam or been shot down while struggling in the river will remain a mystery. (8)

Within the space of four months in 1862, Patrick Vaughan lost both his young sons to the fighting in the Western Theater. Though the two boys had initially enlisted in the army, it seems they were fated to both breath their last aboard ships. The future of the octogenarian once again hung in the balance. In the pension application that followed, he decided to base his claim on John’s service, as his elder son had given more financial aid for his support– between $50 and $60 a year. It did not prove difficult for him to prove his incapacity to earn a living. William Watson, a surgeon in Dubuque, Iowa, examined him in 1869. He recorded that Patrick was ‘entirely incapacitated by old age…he also has a large inguinal hernia of the left side which would disable him if he were many years younger.’ In 1870 Watson was also asked to comment on Patrick’s age, which by this point was said to be 87 years. The surgeon had no doubt this was correct, as ‘his appearance fully justifies its truthfulness.’ Patrick was being examined in Dubuque because he had moved to Ballyclough in Dubuque County, a largely Irish settlement–unsurprising given its name. It is there that he makes the only census appearance I have been able to locate, where he was enumerated as ‘Patrick Baughan’ in 1870. He lived with 55-year-old farmer Michael Nagle, his 54-year-old wife Johanna, both Irish natives, and their 19-year-old Iowa born daughter Philomena. Why he was with them is unknown, but perhaps they were relatives. Both Michael and Johanna gave statements as to their knowledge of his marriage and the support provided by his sons. In an interesting postscript, in 1863 Patrick’s minor daughter Honora was to be found in New Brighton, Beaver County, Pennsylvania, where Moses Knott, an English-born toll clerk, was appointed her legal guardian, seemingly with the support of Honora’s sister Mary. Moses applied for a pension for Honora based on the fact that her brother John had supported her, though this appears to have been unsuccessful. (9)

Patrick Vaughan seems to have lived until around 1877. Though the details on his family, spread across Ireland and the United States, are scant, there is little doubt that the emotional hardship he experienced across those four months in 1862 must have been on a par with the worst days of his already very long life. On the roll call of momentous events that he had lived through across more than nine decades, Fort Donelson and the fate of the USS Mound City must have loomed large.

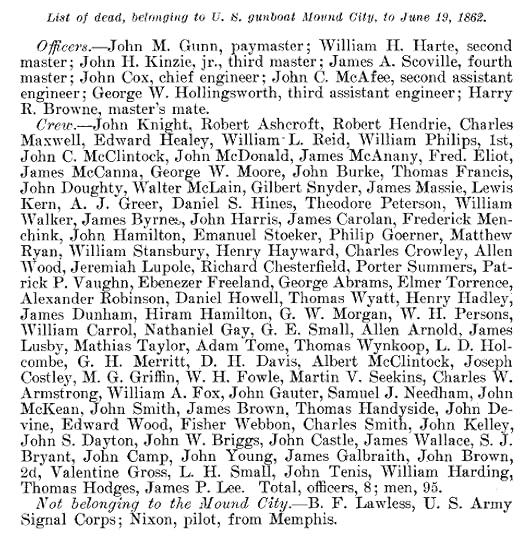

The list of dead from the USS Mound City from the Official Records. Limerick’s Patrick Vaughan is among them. (Official Records)

(1) John Vaughan Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid., Illinois Muster Roll Database, New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (4) John Vaughan Pension File; (5) Illinois Adjutant General Regimental & Unit Histories, John Vaughan Pension File; (6) Illinois Adjutant General Regimental & Unit Histories, Civil War Trust Fort Donelson Page, Official Records Series 1, Vol. 7: 199, 182, John Vaughan Pension File; (7) Official Records Navy Series 1, Vol. 23: 166; (8) Ibid.: 167, 180, John Vaughan Pension File; (9) John Vaughan Pension File, 1870 US Census;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

WC143659. Pension of Patrick Vaughan, Dependent Father of John Vaughan, Company B, 11th Illinois Volunteer Infantry.

John Vaughn: Illinois Muster Roll Database.

Patrick J. Vaughn New York Muster Roll Abstract.

1860 U.S. Federal Census, New Brighton Ward 1, Beaver, Pennsylvania.

1870 U.S. Federal Census, Table Mound, Dubuque, Iowa.

Civil War Trust Battle of Fort Donelson Page .

Illinois Adjutant General Regiment and Unit Histories.

Official Records Series 1, Volume 7. Return of Casualties in the First Division (McClernand’s), at Fort Donelson, Tenn., February 13-15, 1862.

Official Records Series 1, Volume 7. Report of Lieut. Col. T.E.G. Ransom, Eleventh Illinois Infantry.

Official Records Navy, Series 1, Volume 23. Report of Lieutenant McGunnegle, U.S. Navy, commanding U.S.S. St. Louis, regarding the attack on St. Charles batteries and explosion on board the U.S.S. Mound City.

Official Records Navy, Series 1, Volume 23. List of dead belonging to U.S. gunboat Mound City, to June 19, 1862.

Fort Donelson National Battlefield.

Hal Jesperson Photography Wikipedia Page.

Naval History and Heritage Command.

Filed under: Battle of Fort Donelson, Iowa, Limerick, New York Tagged: 11th Illinois Infantry, 49th New York Infantry, Battle of Fort Donelson, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Buffalo, Irish in Iowa, Limerick Emigrants, USS Mound City

August 17, 2016

Irish in the American Civil War Needs Your Votes (Again!)

I am delighted to say that Irish in the American Civil War has been shortlisted for the 2016 Irish Blog Awards in the Arts & Culture category. This is the same category the site was fortunate enough to win in the 2015 Blog Awards, thanks in no small part to the many readers who voted for it. This year, 20% of the judging relies on public vote; if you would like to cast a ballot for the blog (and thanks to everyone who does!) you can do so via the link here: Irish in the American Civil War Vote Page which can also be accessed by clicking the image in the sidebar.

Filed under: Blogs Tagged: Arts & Culture, Blog Awards Ireland, History Blogs, Irish American Civil War

August 14, 2016

Charting Desertion in the Irish Brigade, Part 1

The Irish Brigade is rightly regarded as one of the finest units to take the field during the American Civil War. However, just like all other Union formations, they had their ups and down in battle, and like other formations, they suffered from desertion. In order to examine this in further detail I have taken the Brigade’s 63rd New York Infantry as a case study, compiling desertion data on the 1,528 men who served in the regiment during the conflict. In the first of a series of posts, I have prepared a number of charts that explore different aspects of desertion in the 63rd. Included among them are the monthly desertions rates in the regiment through the war, with a daily focus on desertion in 1861. Also examined are the locations of desertions, and finally a comparative look at the ages of all the men in the 63rd relative to the ages of those who deserted.

The data on which these charts are based was drawn from the New York Adjutant General roster of the 63rd New York Infantry. Of the 1,528 men listed as serving in the regiment, 368 are recorded as having deserted during the conflict, for a total desertion rate of 24%. The first chart represents the numbers of desertions in the 63rd by month throughout their war service. To examine each of these charts in detail click on the images to enlarge them.

Monthly desertion rate in the 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade, from 1861 to 1865– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

What is immediately noticeable is that the overwhelming majority of desertions from the 63rd New York Infantry took place in 1861, before the regiment had seen any active service. The other peaks in desertion were August-September 1862, January 1863, September-October 1863 (these are the only five months outside of 1861 that saw double-figure desertions) and to a lesser extent January-February 1864. There are a number of things to bear in mind when looking at this data. The first is one of scale and proportionality. The 63rd New York was a full-size regiment of nearly 1,000 men in late 1861, yet brought only 75 men into battle at Gettysburg in July 1863. The regiment’s numbers would rise once more in 1864 but would be quickly depleted again. It is nonetheless interesting to note how desertion rates appear to flatten out through 1864 and 1865, at a time when overall desertion averages in the Union army were on the rise. The other point to note is that not all desertions from the regiment actually occurred with the regiment, as will be explored in one of the charts below. Nonetheless, the 1861 figures in particular are interesting, and deserve further examination. The next chart examines desertions by day in the 63rd through 1861– again, click on the image to enlarge it an explore the data in more detail. (1)

Daily desertion rate in the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade for 1861– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

Desertion was fundamentally an act that relied upon opportunity. There were large portions of a regiment’s service where it was difficult for men to desert, particularly if their intent was to go home (as opposed to deserting to the enemy). The best time to desert– for men who were so inclined– was when in camp and close to good lines of communication. Better again was to desert before you ever left home, which is what the majority of those who fled from the 63rd New York chose to do. It is interesting to note that despite the fanfare, pride and patriotism that was a hallmark of the formation of the Irish Brigade in 1861, large numbers of men quickly decided that service in the unit wasn’t for them.

As noted above, 1861 was by far and away the worst year for desertion from the 63rd. There are undoubtedly numerous reasons for this; many men likely found that military life was much more disciplinarian and structured than they had anticipated, while others may have taken the decision to depart due to issues with their officers or comrades. It is instructive to examine the data in closer detail. 156 men deserted the regiment between August and September 1861, with 73 of them in November alone. To put this in perspective, the closest subsequent desertion rates would come to the November 1861 figures was in October 1863, when 25 men deserted. Why was November so bad? One reason was undoubtedly disenchantment. The New York Irish-American reported that at the time there was ‘a good deal of discontent’ among the men of the regiment on their base at David’s Island, because of an ‘unaccountable delay in paying off the men.’ Whatever a soldier’s motivation for enlistment, if they were not getting money with which to provide for themselves or their family, they were going to be more reluctant to stay in service. A closer look at the data also reveals another reason behind the high November figures. The 28th November 1861 was the 63rd New York’s worst day of the war for desertion, when no fewer than 15 men departed. Why? The 28th November was the day the 63rd left New York for the seat of war. When it came to it, some of the men were not willing to leave New York. (2)

Desertions by State location in the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade- Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

The third chart (above) examines the locations of desertions, organised by State (click the image to enlarge). As pointed out, opportunity was a major factor in desertion, and it is no surprise that the vast bulk of men departed from New York. Though some left while recuperating from wounds or on furlough, the majority of New York deserters after 1861 were new recruits, who only had time to be entered on the rolls before leaving, and so never actually saw active service with the regiment at the front.

Desertions by age in the 63rd New York, Irish Brigade– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

Some men deserted because they didn’t like the military life, some because of erratic pay, others because they were no longer able to endure the horrors of conflict. As we have seen in a number of pension files, many men were also put under considerable pressure to desert by those at home, be they dependent parents or wives and children. With that in mind we might expect to see a higher proportion of men of likely married age departing the ranks. The fourth chart (above) looks at the ages of 63rd New York deserters, showing a concentration among those aged between 17 and 28. However, to examine any potential significance in this data it is necessary to also have information on the relative ages of all the men of the regiment, which is the purpose of the fifth chart (below).

63rd New York Regiment by Age– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

The above chart illustrates the ages of all the men who served in the 63rd New York Infantry on enlistment. This chart is of course of significant interest in and of itself; the largest age group we see for soldiers in the regiment is the 26 to 28 bracket, with the majority of soldiers who served in the 63rd during the war aged between 17 and 28. It is nonetheless of note just how many of the regiment were aged between 29 and 44. When the age range of the entire regiment is compared with the age range of those who are known to have deserted, it seems to indicate no distinctions between age-groups when it came to likelihood to desert. To further examine this, we can look at the same data expressed as percentages, as has been done below.

63rd New York soldiers by Age expressed as a percentage– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

This pie chart (above) shows the ages of all the men of the 63rd New York on enlistment expressed as percentages. It excludes those for whom no age was stated in the Adjutant-General report. 59% of those for whom we have figures were aged between 17 and 28. The remainder of the regiment were over this age. The pie chart below shows the deserter age groups as percentages (again excluding those for whom no age was stated). There is a remarkable correlation between the two, indicating that in the 63rd New York at least, age cannot be taken as an indicator of likelihood to desert, and those who were more likely to be married do not appear to have deserted at an appreciably higher rate than those who were not.

63rd New York Deserters by age expressed as a percentage– Click to enlarge (Damian Shiels)

Almost one in four of all the soldiers who served in the 63rd New York Regiment of the Irish Brigade deserted during the American Civil War. The next post will drill further into the data to look at some specific examples and trends, such as the desertion rates of early war volunteers when compared with those who volunteered or were drafted in later years; the men who deserted during battle and campaigns, and those who took the decision to leave having been wounded.

(1) Lonn 1998, 152, 233-235; (2) New York Irish American 7th December 1861;

References

New York Irish American 7th December 1861. Departure of the 3d Irish Regiment, 63rd N.Y.S.V.

Adjutant-General 1901. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1901.

Lonn, Ella 1998. Desertion During the Civil War.

Filed under: 63rd New York, Digital Arts and Humanities, Irish Brigade Tagged: 63rd New York Infantry, Civil War Analysis, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Irish Brigade Desertion, Irish Desertion Rates, New York Irish, Union Army Desertion

August 9, 2016

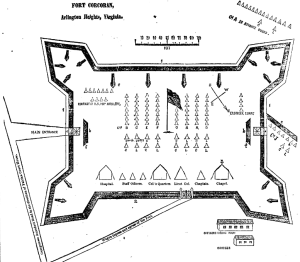

Portraits from the New York Irish-American Weekly: 1861

Every week the New York Irish-American brought it’s news to Irish readers not just in The Empire State, but all over the United States. Many Irish soldiers at the front remained loyal readers of the newspaper throughout the Civil War. From time to time, the Irish-American printed portraits and illustrations of famous Irish-Americans, Catholics and places and objects relating to the Irish, which were carried on the front page of the paper. Some of these images were also available for commercial sale; portraits of famed leaders like Michael Corcoran and Thomas Francis Meagher proved particularly popular. In the first in a series of posts on these images that will cover each year of the American Civil War, we take a look at those that were included on the front page during 1861 (click the images to enlarge and read the captions).

References

New York Irish-American Weekly.

Filed under: Donegal, Fermanagh, New York, Sligo, Waterford Tagged: Fort Corcoran, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, James A. Mulligan, James Haggerty, Michael Corcoran, Terence Bellew McManus, Thomas Francis Meagher

July 23, 2016

Killed By Torture? The Story of an 18-Year-Old Irishman’s Death at the Hands of his Officers, New Orleans, 1865

In May 1860, 47-year-old Bridget Griffin stepped off the boat in the United States. Her husband John had died in their native Athlone in 1859, an event that likely precipitated her departure. With her was her 13-year-old son Patrick, a boy who grew to manhood during the years of the American Civil War. He would serve during that conflict, initially with the 15th Massachusetts Light Artillery and later in the 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery. June 1865 found him with the latter unit in New Orleans; having seemingly made it through the conflict, his mother probably looked forward to having him home. But instead she received a remarkable letter, written– anonymously– by some of Patrick’s comrades. It brought news of her boy’s death, which had come not at the hands of the Rebels, but as part of a particularly savage punishment meted out to the teenager by his own officers. (1)

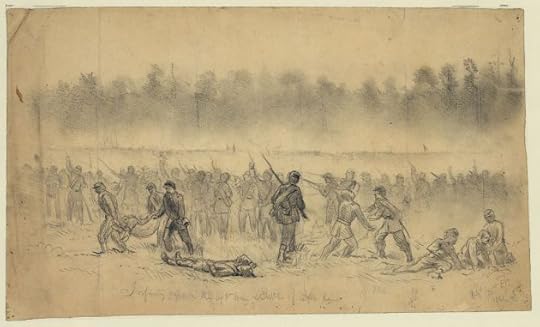

Punishment of Union soldiers, as depicted by Alfred Waud. In the case of Patrick Griffin, he was tied up by the thumbs, with his feet barely touching the ground, and gagged (Library of Congress)

Having arrived in America, the Griffins settled in Lowell, Massachusetts, where they knew many other Athlone emigrants– people like Hannah and Celia Keyes, who had left the midlands town a few years before and worked as mill hands. Patrick first got similar employment, working at manufacturers like the Hamilton Corporation, the Root Corporation and the Carpet Corporation. He also did work for a Mr. Fox, and latterly a wood dealer, taking his pay in wood which helped to provide fuel for his mother. Hannah Keyes moved in with the Griffins on St. Patrick’s Day 1863, but within a few months Patrick was on his way. On 23rd December 1863 he was enrolled in Lowell in the Union Army; his records indicate that he was part of the draft. The night before he left for the army, he told a family friend that he intended to send all he earned home to his mother. Before he departed for the front he had managed to buy her a barrel of flour, and also forwarded her the initial instalment of bounty money which he received. (2)

Patrick commenced his service in the 15th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery. His service record indicates he was born in Co. Roscommon (suggested he was from the western, or Connacht side of Athlone), had blue eyes, light hair and a light complexion, and was 5 feet 3 1/2 inches in height. Patrick formed part of the draft quota from Lowell’s Second Ward. Despite what some of his comrades would later claim, it seems that he may not have been a model soldier. He was listed as having deserted from his unit on 12th May 1864 in New Orleans, and the army advertised a reward of $30 for his apprehension. He was duly captured on 30th May along with two other deserters (Thomas Anderson and Henry Brown), and confined to camp under arrest. The charge of desertion was later removed and changed to one of being absent without leave, as he had been returned to his unit. On 5th January 1865 Patrick was transferred to the 6th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery. Six months later, his mother in Lowell received the anonymous letter.

Receipt for payment of award for the capture of Patrick Griffin in New Orleans (Fold3/NARA)

New Orleans June 26 1865

From a Friend:-

Mrs. Griffin: I take the painful opportunity, of writing you these few lines, letting you know that your son is dead. This Monday morning, the 26th inst., he was sick, and he was ordered out by the second lieutenant and the sargent of his detachment. He told the sargent that he was not able to ride out the horses, and that if he took them out, that he would fall off, for he was not able to hold on to them. The Second Lieutenant also ordered him out, and that he should go out. Then he had to take the horses, and go out. Then we went out, the distance altogether making about three miles, and it was a wasting hot day. When we got about a mile and-a-half he was thrown off the horse, and could not get on them again. Then in a short time after we were to go to camp; and he was not able to walk to camp. So as we were coming along one of the streets, he had to leave us and sit down. Then the Sargeant had to take his horses and fetch them to camp along with him. So when we got to camp he was reported absent; and there was four guards and a corporal sent out after him to fetch him to camp. Which they found him in the same place as we left him. Then the guards fetched hm to camp, and it was as much as they were able to do because he was scarcely able to walk. So when he was fetched to Camp he was ordered to be tied up by the thumbs in which he was standing almost on the tops of his toes. He was not tied up ten minutes, before he commenced crying, and asked three or four times to be taken down. And still he kept a crying, but it was of no use. Even they did not give him no dinner, nor give him time to get it. And still he kept a crying for God’s sake to let him down; then the Captain came out and ordered him to be gagged, in which he was. And he was gagged so tight, that when he was taken down, the stick was covered all over with blood. Then he was taken down, and taken to the rear, and when he was going to the rear he vomited with the dint of weakness. Then when he came back, he was strung up again, and left so until he fainted away. Then he was taken down, and brought to a little, and left so for about an hour, when at the expiration he died. Mrs. Griffin;- There is coming entirely, between three and four hundred dollars to him; in which you ought to see and get it. Write to the Captain of the Battery, and he will let you know all about it.

Direct you letter to

Captain E.K. Russell

6th Mass. Battery.

New Orleans La.

Write as quick as possible

From friends of his. (3)

The first page of the anonymous ‘From A Friend’ letter that informed Bridget Griffin of her son’s death, and how it had occurred (Fold3/NARA)

The impact of this letter on Bridget Griffin is difficult to imagine. Her son had apparently died not at the hands of the enemy, but of his own officers, and she had been spared little detail on the brutality of the incident. This anonymous letter, which had been written on the day of the event, remained unsigned as the men who wrote it feared the consequences should they append their names to the document. It was not long before the incident made the newspapers. Initially reported in the New Orleans Delta, it soon made its way to the North. On 8th July 1865 the Cleveland Daily Leader reported on the ‘Horrible Affair at New Orleans’ concerning the ‘alleged torturing to death’ of Patrick. They quoted from the Delta correspondent:

We saw him in his coffin next Tuesday morning, when he was fast decomposing. His neck was greatly swollen, and blood was oozing from his mouth and nostrils. The case was reported to General Andrews, Chief of General Canby’s staff, who immediately ordered a medical investigation of the corpse. Two or three Surgeons examined the body, and reported that he died from habitual intemperance. The gag used was of hard cyprus, seven or eight inches long, and where it came in Griffin’s mouth was gnawed to the depth of half an inch. It was deeply stained with blood. The examining surgeons say that, had it not been placed loosly in his mouth, he could not have chewed the gag in the manner he did. General Sherman is investigating the matter…His officers state that he was constantly drunk and running away from camp. He yesterday received a list of forty or fifty names of men belonging to the battery who desired to be summoned as witnesses in behalf of what they termed the murder. A statement of the case was sent to Governor Andrew, of Massachusetts, and another to the Boston Journal. (4)

The story was also reported in Patrick’s home town in Lowell. The Lowell Daily Citizen and News actually refers directly to the letter that I have transcribed above:

… A recent letter, received by the mother of the boy from members of the Battery, substantiates the statements of cruelty, but states that young Griffin was sick and not intoxicated…The affair is being investigated, and, if there are guilty parties, they should be brought to severe punishment. (5)

The immediate furore over the incident, combined with the outrage being expressed over it by the men of Patrick’s Company, necessitated a response. The day after the young man’s death, a report on the incident was compiled by the Acting Assistant-Adjutant General for Brevet Major-General Thomas W. Sherman.

Headquarters, Southern Division of Louisiana

Inspector General’s Office

New Orleans, June 27th 1865

Brevet Maj Gen T.W. Sherman

Comg Gen

I have the honor to report that I have investigated the circumstance connected with the death of a private in the 6th Mass Battery who died yesterday and find, 1st. That Private P. Griffin was absent without leave in the morning, that on his return he was ordered to go out where the men were drilling, or exercising the horses, and that after he got on the ground he refused to do duty.

2d. That Captain Russell when he was brought in ordered him tied up by his thumbs and gaged. That some time between 2.30 PM and 3 o’clock he was cut down insensible and that he died about 4 P.M.

2d Lieut Daniel A Shean was officer of the day and his statement and Sergeant of the Guard Young and Corporal of the Guard Parker agree as to the time he was tied up, about 12 m, and the time he was cut down, about 2.30 or 3 P.M. Sergt Young says he was gaged to stop his noise, that when he helped to turn him down he was hanging by his thumbs insensible with his head hanging back and that he remained insensible up to the time of his death. Neither Lt. Shean, Sergt Young or Corporal Parker can tell whether or not the gag remained in his mouth until he was taken down but they think not. Corporal Parker thnks he hung by his thumbs insensible fifteen minuets before he was cut down.

Asst Surg David Stephens 20th USCI was called to see him and I found his certificate that he died of apoplexy. In conversation with me he said that Griffin was insensible when he saw him, had a very hot head was very much exhausted and beyond help. Had [illegible] in his throat and on being turned on his side a fluid ran from his mouth very much mixed with mucous but he discovered no symptoms of liquor. He things his deat was hastened by his punishment, and that was was at first very much reduced by debauchery and that this punishment would increase that weakness, but not knowing the patient before cannot give you an opinion as to how far his death is attributable to the punishment.

Respectfully,

Your Obt Svt

W D Smith Lt Col

110th NYV [Acting Assistant Inspector General]

So Div La (6)

Patrick’s mother Bridget understandably requested that action be taken agains the men she held responsible for her son’s death. She reportedly wrote to Secretary Stanton requesting that Captain Russell not be mustered out of the service until he could be tried for court-martial for ‘causing the death of her son.’ But events had already moved beyond this. On 30th June both Captain Russell and Lieutenant Shean had formally requested a Board of Inquiry to be held to clear their names. In this they appear to have been successful. on 16th August 1865 the Lowell Daily Citizen and News provided it’s readers with the following update:

THE CASE OF PATRICK GRIFFIN. In our issue of July 11th some particulars concerning the treatment of a Lowell soldier, Patrick Griffin, of the 6th Battery, and his subsequent death, were given, chiefly on the authority of the New Orleans True Delta, which paper represented that Griffin had been subjected to barbarous punishment while in feeble health, and that death ensued as a result of the punishment. Since this statement was published, some additional facts have come to our knowledge, which go far to relieve the case of its most revolting features. It now appears that a post-mortem examination was had, by which it appeared that death ensued from other causes than the punishment, the form of which was exaggerated and misstated in material points. It also appears that Capt. Russell of the 6th Battery, who had been accused of the ill-treatment of the soldier, demanded and official inquiry into his conduct, which was accorded to him, Col. Buchanan of 1st U.S. Infantry presiding over the court. The document, showing the result of the inquest, have been shown to us. It is not necessary to go into all the details, but it is proper to state that the finding of the court, which was duly approved, ascribes the soldier’s death to other causes than those alleged in the published accounts, and, though the punishment was pronounced both illegal and severe, Capt. Russell was relieved of further blame, and has since been regularly discharged. (7)

Written appeal of Patrick’s Captain, E.K. Russell, for an inquiry into Patrick’s death (Fold3/NARA)

Patrick’s previous misdemeanours and apparent fondness for alcohol had stood against him. It seems probable that his officers, who may have witnessed Patrick inebriated before, mistook his illness for drunkeness, and sought to teach him a lesson. Rightly or wrongly, the authorities took the decision that his officer’s had no serious case to answer with respect to his death, which was recorded as apoplexy. When Bridget applied for a pension based on her son’s service, she included the anonymous letter she had received from men of the 6th Battery in her claim. By then the war was over, and those who had served in the 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery had been discharged. In consequence of that, in late 1865 and 1866 three of Patrick’s former comrades came forward to swear affidavits as to what they witnessed on the day of Patrick’s death. No longer concerned about what may befall them, Patrick Carey, George Bagshaw and Alfred Hackett made their marks on the statements. Each of these accounts have been transcribed below. The anger they felt about the incident is apparent, and no doubt they did not agree with the conclusion of the inquiry. I leave readers to form their own opinions– whatever the truth of events, the young teenage emigrant surely did not deserve to meet such a horrific end, testament to the harshness of military justice in 1860s America.

Affidavit of Patrick Carey (Provided in August 1866, the Irish laborer had served with Patrick Griffin in the 15th and 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery):

Patrick told me he was sick, too sick to attend the roll-call. I had occupied the same room with him through the night. I went to his bunk to call him for the roll-call, and he said he was sick and could not go down and did not go. I saw no more of [him]…until about ten o’clock A.M. We had been out to exercise the horses about two miles from Camp. On our way back about a mile from Camp we came to Patrick lying by the side of the road having fallen from his horse when we were going out. Sergeant Dodswort spoke to him and told him to get up and get on to his horse– Patrick replied that he was not able. The Sergeant passed on leaving him in the hands of a keeper. When we arrived in Camp a Corporal and two others went after him and carried, or rather brought him to Camp. He went into one of the guard tents and laid down and said he was sick– no one made any reply to what he said– he laid there a while upon the bank. Then the officer of the day Lieut Daniel Shean, the officer of the day, came out and caused…Patrick to be tied up the thumbs with a small cord and tied on to a spike in a post. They kept him there suspended by the thumbs for nearly an hour or two, then they gagged him with a stick of wood…(I did not see that done, being then absent for a short time)…I then came back he then laid in the guard house, was not able to speak and died in some twenty or thirty minutes. No surgeon or doctor was called until he was dying…I heard…Patrick say he was sick, and while they were tying him up, he told, and tried to persuade them, that was sick, and said he could not live to bear it. (8)

Patrick’s Final Statement, which lists his possessions at the time of his death. They were a coat, jacket, trousers, shirt and shoes. He was also recorded as two inches taller than at the time of his enlistment, perhaps an indication he was still growing when he entered service. (Fold3/NARA)

Affidavit of George Bagshaw (A native of Bradford, England, George had served with Patrick in both the 15th and 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery):

I saw him in the morning when he got up– he looked sick– said he did not fel well enough to go out with the horses. He tried to get a man to go out with his horses in his stead but did not succeed. They compelled him to go. I heard him ask a man to go in his place. I was on guard in the camp for that day. He said that morning he wanted a doctor for he was sick. I thought he was sick, [he] showed me his tongue, it was coated with [a] whitish coat. We had no surgeon in the Battery; there was an out-rider that visited us sometimes when we were sick. I don’t remember his name. I saw them tie him up by the thumbs when they brought him in. He declared to them that he was sick, complained of his head, said it ached. After he had been up half or three quarters of an hour he begged them to take him down so that he was sick– that he could not stand it– then he asked to be let down to go to the rear. They did so, and then tied him up again. Then in about twenty minutes he cried out for them to let him go again to the rear, but they would not do it, and did not. He fell upon his thumbs, the cord slipped off, and he dropped upon the ground, and laid motionless. Then Lieut. Shean ordered him to be tied up again, and Corporal Parker tied him up again. He made no resistence but told them he was sick and could not stand it. He began them to cry aloud. Then the Lieut. ordered him gagged, and then Parker gagged him with a stick about 5 inches long and an inch and a half thick, tying it hard into his mouth so that I saw the blood at the corners of the mouth, and I saw the gag was quite bloody when it came from his mouth when he was finally taken down. While he was up there a Sergeant by the name of Young went and told Lieut. Shean that Griffin was dying, and the Lieut. came, put his hand on his forehead, smiled and then went away laughing. Then in about a quarter of an hour afterwards Young went again and told him that he was dying, and then Shean came part way down and told Young to take him down and put him in the guard house, and Young did so. He dropped down, and they carried him in. He told them while he layed there if they would take him out of the guard house into the air he would get well. They did not take him out, then one of the prisoners hollered out that Griffin was dying. Then the Lieut came down and they took him out. They then sent for the Doctor of the Colored Regiment who came. He said the man was too far gone, asked them was [there] any ice in the camp? And the Lieut went and got some, but it was too late he was dying and the Dr did not use it. Said Griffin vomited while they were putting the gag into his mouth, and vomited after the Dr came. The doctor said he did not smell any intoxicating liquor. He had not been drinking any intoxicating liquor that day, I did not smell any– he was sick. I stood by him, was guarding the table on which he layed when he died. He was a very good soldier, he had been constantly on duty at least for several days previous to this time. (9)

Affidavit of Alfred Hackett (A native of Grafton, New Hampshire, Alfred had served with Patrick in the 15th and 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery):

‘On that day…Battery 6th Mass was on what we called police duty, such as cleaning up the yard and taking care of the horses…at about 9 o’clock A.M. the Battery was ordered out about one and a half miles from Camp under the lead of the Sergeant to exercise the horses, that upon this order…Griffin told the Sargents that he was sick and sore and not able to ride so far, but they ordered him to mount…when we got out about half way to the ground of parade…Patrick fell from his horse and we left him there holding his horse he sitting upon the ground. When we came back we took his horse into camp leaving…Griffin there one man staying with him. Then the next that I saw…he was brought into Camp about an hour afterwards under guard, and by order of Capt. Edward K. Russell he was tied up by the thumbs for not coming into camp when the rest did. He was found as I was informed at the time on the same spot where he fell from his horse. After he had been tied up…(to a spike in a post by a cord so that his toes would but just touch the ground) for about ten minutes, he began to cry and beg them to take him down. Upon this the Captain came out and ordered the Corporal of the guard to gage him, so as to stop his noise. This being done, in about twenty minutes or more he fainted then the Corporal went and reported him to the Captain as having fainted, and the Captain them ordered him taken down. The gag was bloody…Griffin did not speak afterwards. He groaned, but remained insensible, and died in about an hour after he was taken down. From what I saw of this transaction I had no doubt that…Griffin was sick that caused him to fall from his horse, and his death was caused by the gag most wrongfully applied to him while sick, and that aside from the officer, who had a hand in that out-rage, more than two thirds of the Company were of the same opinion as I learnt by their conversation…Griffin I should judge to be not far from 18 years of age… (10)

Record of the death and interment of Patrick Griffin (Fold3/NARA)

(1) Griffin Pension File; (2) Griffin Pension File; (3) Griffin Pension File, Patrick Griffin Service Records; (4) Cleveland Daily Leader 8th July 1865; (5) Lowell Daily Citizen and News 11th July 1865; (6) Patrick Griffin Service Record 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery; (7) Ibid., Lowell Daily Citizen and News 16th August 1865; (8) Griffin Pension File; (9) Ibid.; (10) Ibid.;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

Widow’s Certificate 85142, Pension File of Bridget Griffin, Dependent Mother of Patrick Griffin, 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery.

Patrick Griffin Service Record, 15th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery.

Patrick Griffin Service Record, 6th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery.

Boston Traveleer 4th August 1865. Various Items.

Cleveland Daily Leader 8th July 1865. Horrible Affair at New Orleans.

Lowell Daily Citizen and News 11th July 1865. Inhuman Treatment of a Lowell Soldier.

Lowell Daily Citizen and News 16th August 1865. The Case of Patrick Griffin.

Filed under: Massachusetts, Roscommon Tagged: 6th Massachusetts Light Artillery, Athlone Emigration, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Lowell, Lowell Draft, Military Punishment, Reconstruction New Orleans, Union Desertions

July 21, 2016

The Forgotten Irish Book: Cover and Contents

As many of you know, I have spent the majority of my writing time since the 2013 publication of The Irish in the American Civil War concentrating on one major source for the Irish experience of 19th century America, namely the widows and dependent pension files of Union soldiers and sailors. It soon became my intention to develop this material into a book, though I struggled for a long time to develop a structure and layout I was happy with (always the most difficult part of any book project). Having finally overcome “Difficult Second Album Syndrome,” I submitted the manuscript to my publishers a few months ago. This week I received both the final page proofs and the finalised cover art for The Forgotten Irish, which I thought I would share with readers, many of whom have been instrumental in both assisting with my research and in encouraging my endeavours. It is also an opportune time to outline the contents of the book, which is due for release in Ireland around November 2016, and hopefully will become available in the United States not too long after that.

The premise behind the book is to demonstrate how we can use the widows and dependent pension files, in conjunction with other sources such as census, military and emigration records, to build a partial picture of the lives of individual Irish emigrant families. Though the material was created as a consequence of the American Civil War, the focus of many of the chapters is not on the conflict, but other aspects of the lives of those left behind. It is my contention that the files offer us the best opportunity to examine in close detail the experiences of Irish emigrants across the second half of the 19th century (and indeed into the 20th). In many instances, these emigrants describe their lives to us in their own words. Another important element of the book was to demonstrate that the American Civil War had a major impact on people in Ireland; to that end, many of the chapters ‘follow’ families back and forth across the Atlantic, and indeed a number of the pension recipients covered both lived and died in Ireland. To provide readers with some more information, I have included the description on the book cover (the ‘blurb’) below, together with the section and chapter headings, to give a flavour of its contents.

THE FORGOTTEN IRISH

Irish Emigrant Experiences in America

On the eve of the American Civil War, 1.6 million Irish-born people were living in the United States. The majority had emigrated to the major industrialised cities of the North; New York alone was home to more than 200,000 Irish, one in four of the total population. As a result, thousands of Irish emigrants fought for the Union between 1861 and 1865. The research for this book has its origins in the widows and dependent pension records of that conflict, which often included not only letters and private correspondence between family members, but unparalleled accounts of their lives in both Ireland and America. The treasure trove of material made available comes, however, at a cost. In every instance, the file only exists due to the death of a soldier or sailor. From that as its starting point, coloured by sadness, the author has crafted the stories of thirty-five Irish families whose lives were emblematic of the nature of the Irish nineteenth-century emigrant experience.

CONTENTS

Preface

ONE– WIVES AND PARENTS

The death of a spouse or child as a result of military service has a profound impact on all those left behind. For some Irish emigrant families, the loss was an event that irretrievably altered their futures, casting a long and dominant shadow over them in the years to come. For others, it represented another hardship in what was already a struggle for survival. ‘Wives and Parents’ examines the stories of both.

The Garvins: Limerick and New York

The Murphys: Monaghan and Illinois

The Donohoes: Galway and Massachusetts

The Coyles: Donegal and Pennsylvania

The Kennedys: Offaly and Ohio

The Ridgways: Dublin and Washington DC

The Duricks: Tipperary and Vermont

The Galvins and Horans: Roscommon, Kerry and Massachusetts

TWO– COMMUNITY AND SOCIETY