S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 4

August 31, 2023

The White Savage

The sound of frenzied whooping mixed with shrill screams filled the ears of the three frightenedboys huddled together for safety. Their hands and feet were bound, so they coulddo nothing but stare helplessly through eyes stinging from tears. Soon, the crackling of flames began to compete with the savage whoops ofthe Delaware braves, who became more excited as the burning fires crept up thefigure tied firmly to a pole.

Some of thebraves shouted what could only be taunts and insults, mainly because the old manremained stiff-lipped as his flesh began to sear and burn, emitting a putridstench that nauseated the three youths while exciting the blood lust of theirtormentors. Finally, the fire completely engulfed the old man, whose headslumped as the dark smoke engulfed him.

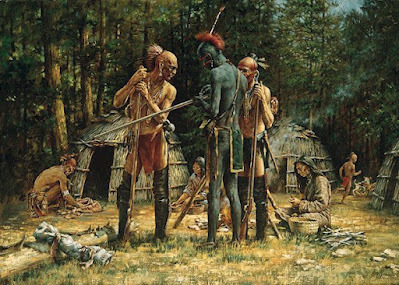

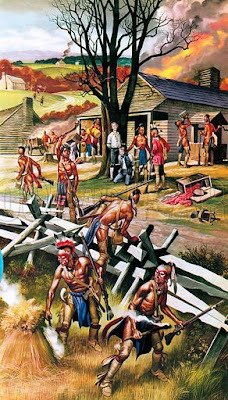

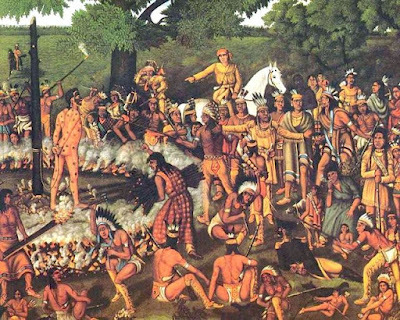

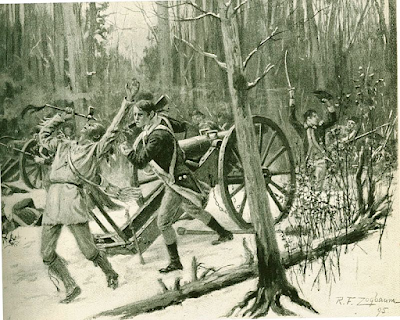

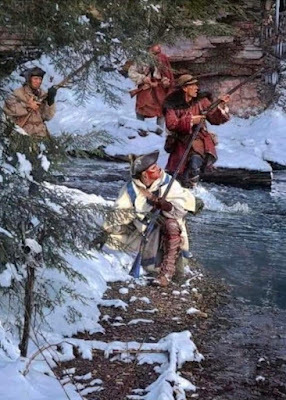

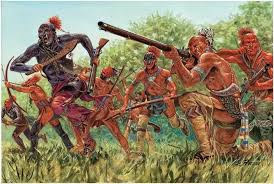

War parties tortured enemies of both races

War parties tortured enemies of both racesOne of theboys shouted when the smoke cleared and the fires subsided, revealing a pile ofcharred wood and bone, "Grandpa!"

"Don'tlet 'em know you're scared," hissed Simon, the oldest. "Never!"

Afterthis, fourteen-year-old Simon Girty and his two brothers were soon parceled outto different tribes as hostages. This was a typical sequence of events forfamilies who settled along the American frontier, a frontier that was Indianterritory.

Simon Girty wasborn in 1741 in ChambersMill, Pennsylvania, a small hamlet near Harrisburg in the middle of the colony.His Scots-Irish family eventually moved to Sherman's Creek, about thirty-fivemiles northwest. In 1751, Girty lost his father, who was killed in aliquor-fueled duel. Girty's grandfather raised the young boys. Girty and hisbrothers grew up illiterate but toughened as the family carved out a living onthe edge of civilization.

Backwoods Homestead

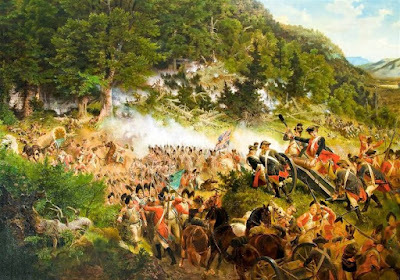

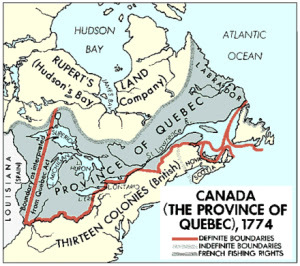

The West AflameIn 1754, warcame to Pennsylvania when France and England engaged in another (final) struggle to control North America. All along the frontier, bands of Indians andtheir French allies raided farms and settlements, unleashing a wave of terror.

French and Indians Attack

French and Indians AttackIn 1756, theGirty family and many others, fearful of falling to the tomahawk, fled to thesafety of Fort Granville, a small stockade some fifty miles northwest ofHarrisburg. A mixedforce of French troops and Native Americans, mostly Lenape warriors, attackedon 2 August. The garrison quickly surrendered, the fort was destroyed, and theGirty's and other settlers were taken captive. But before they trekked off tolive with new masters, they were forced to watch their grandfather burn at thestake.

Indian LifeSimon wastaken by the Delaware tribe but was later passed on to a band of Seneca, who marchedhim to the Ohio Territory, where they "adopted" the young man intothe Seneca nation. As was often the case with white captives, Girty quickly took tolife among the native tribes, learning their language and customs.

He soon began to learn Iroquois and the nuances of tribal life and warfare.

Braves preparing for a hunt

Braves preparing for a hunt

Girty wasfinally released at Fort Pitt in 1759, but by that time, he was fluent in the Seneca and Iroquoislanguages and well-versed in all aspects of tribal life and, most importantly, Indianwarfare — a Seneca in all but skin color.

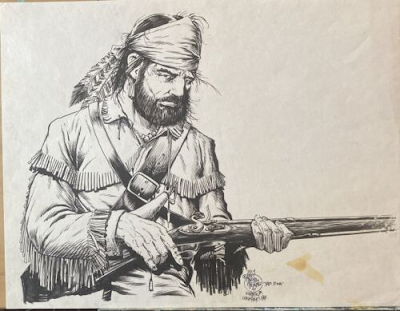

Simon Girty as Scout

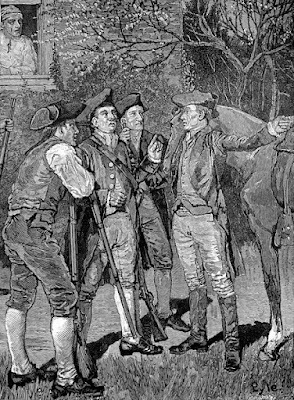

Simon Girty as ScoutGirty returnedto his mother, where he lived as a struggling farmer. He also worked as aninterpreter for fur traders trading with the Delaware Indians in westernPennsylvania. The Britishauthorities also sought his skills and engaged him in negotiating treaties withthe various tribes along the frontier.

Girty served in Lord Dunmore's War

Girty served in Lord Dunmore's WarDuring LordDunmore's War against the Shawnee nation in 1774, Girty became an expert frontier scout. There, he became friends with Simon Kenton, a well-knownfrontier scout.

When war between Britain and her American colonies erupted in 1775, Simon sided with the patriotcause. General James Wood sent him back to the Ohio Territory, where he helpedthe American negotiations with the Shawnee, the Seneca, the Delaware, and theWyandot.

Girty Armed for WarTroublemaker

Girty Armed for WarTroublemakerMilitarydiscipline did not sit well with Girty, who constantly got into trouble with theofficers appointed over him. This came to a head in September 1777, when he wasarrested and put up on treason charges when he was suspected of helping planthe seizure of Fort Pitt.

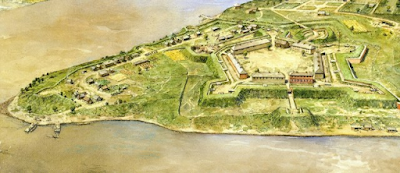

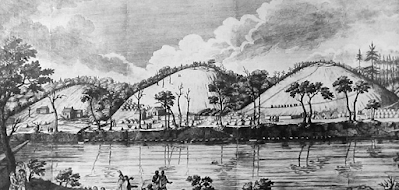

Fort Pitt

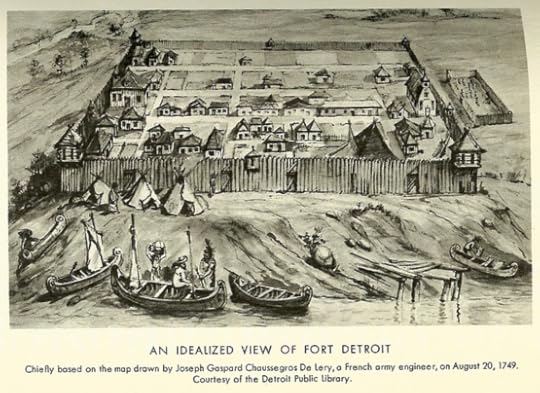

Fort PittLocal Loyalists planned to kill Fort Pitt's occupantsbefore handing it to the British. Girty was acquitted, but the experience lefthim bitter, and he switched allegiance back to the crown. In March 1778, thefrontiersman Girty, accompanied by his brothers James and George, quietlyslipped out of the fort and traveled to Detroit, the main British base in thenorthwest.

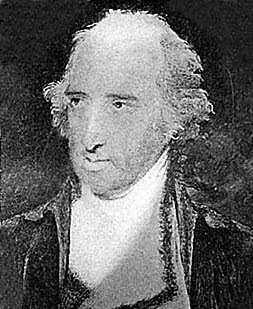

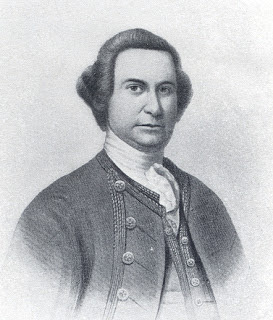

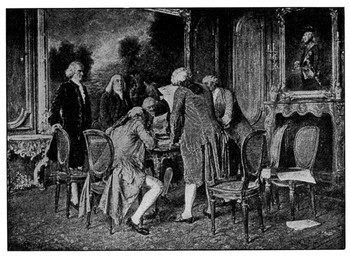

There,British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton recognized the need for Girty'sskills as a linguist and frontiersman and ordered him to be attached to theIndian Department, where he quickly became notorious along the northwest frontier.

Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton

Lieutenant Governor Henry HamiltonBackwoodsPirate

From that timetill the end of the war in 1783, Simon Girty beleaguered the Americans. Hiscultural and linguistic abilities enabled him to recruit many native tribes tothe British cause and equally dissuaded them from supporting the Americans. Heled or directed raids, ambushes, robberies, and outright massacres that madehim the terror of the West. Terrified settlers began calling him The WhiteSavage or The Great Renegade.

Frontier Terror

Frontier TerrorFirst Blood

His realforay into mayhem began in 1779, when Girty, at the head of mixed bands ofLoyalists and Indians, conducted several attacks that left the patriots reeling.He launched Indian war bands against the area around Fort Laurens, Ohio, wherethey massacred several patriot units. His 4 October 1779 ambush of an American columnled by Colonel David Rogers was a master stroke against the cause that leftfifty-seven militiamen dead while taking 600,000 Spanish Dollars.

Ambush

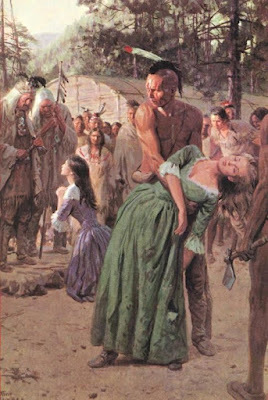

AmbushIn 1780, Girtyhelped British Captain Henry Bird lead a major foray against Americansettlements in Kentucky. The mission resulted in taking a pair of forts and morethan 300 hostages — among whom was his former friend Simon Kenton, whoserelease he arranged.

Taking Hostages

Taking HostagesHe also arrangedto move the pre-patriot Moravian missionaries, David Zeisberger and JohnHeckewelder, with their native parishioners to far reaches of the UpperSandusky River. This enabled the British to monitor their activities better. Itwas not the last time the British would move civilians to control them better —the Boer War comes to mind.

The Great Renegade

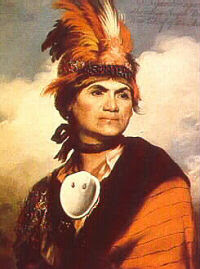

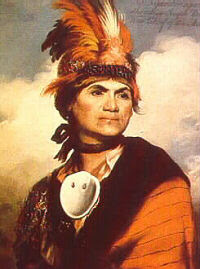

By now, theAmericans had branded Girty a turncoat — placing a reward of 800 dollars forhim, dead or alive. The firebrand Girty even managed to anger arguably the mostpreeminent Loyalists, Iroquois war chief Joseph Brant, getting in Brant's facefor bragging. The equally fiery Brant slashed Girty across the face with hissaber, leaving a wicked Al Capone-like scar. Ironically, the mutilation gaveGirty much prestige among the braves.

Chief Joseph BrantCampaign ofInfamy

Chief Joseph BrantCampaign ofInfamyIn June of1782, Captain William Caldwell and Simon Girty led a party of 400 warriors fromthe Wyandot, Lenape, and Shawnee tribes, along with a detachment of Butler'sRangers, against a column of 500 volunteers under Colonel William Crawford. Theychecked the American advance aimed at destroying Indian enclaves on theSandusky River. Then they surrounded Crawford's command, which retreated in aconfused panic.

Torture and Death of Colonel Crawford

Torture and Death of Colonel CrawfordThey captured many prisoners, including Crawford, who wasbrutally tortured over several days and then burned to death at the stake. Justas with his grandfather, Girty was said to have stood by without interfering, gaininglasting infamy among Americans on the frontier. However, some accounts say hewas threatened with his own scalping if he interfered.

KentuckyKillingCaldwell, Girty,and the mixed band took their mayhem into Kentucky, launching brutal assaults againstthe many defenseless farms and hamlets. This campaign of terror reached itsapogee after their failed 15 August siege of Bryan's Station. When he got wordof an oncoming relief force, Girty and his band decided on a ruse. As thecolumn approached, they faked a retreat.

Siege of Bryan's Station

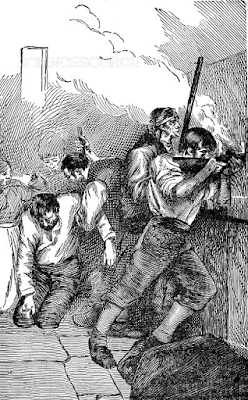

Siege of Bryan's StationGirty positioneda few of his braves along the bluffs overlooking the Blue Licks River. He keptthem in plain sight, hoping to lure the Kentuckians into a kill zone. Caldwellplaced the majority of the rangers and warriors in ravines and behind boulders.The trap was set.

Battle of Blue Licks

Battle of Blue LicksOne of thecolumn's leaders, famed frontiersman Daniel Boone, suspected a trap and urgedcaution, but the column's commander, Major Hugh McGary, led his men headlong acrossthe stream. Boone commented, "They'd all be slaughtered," but led hiscommand to the right side of the McGary's line, which moved directly into adeadly ambush.

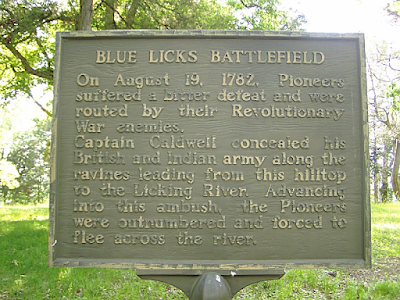

Blue Licks marker

Blue Licks markerTheKentuckians moved up the bluffs in a skirmish line, but once at the heights, Girty'smen opened fire at close range with devastating effect. The relief force wassent reeling back, leaving seventy dead on the field, including the son ofDaniel Boone. Caldwell and Girty's party then withdrew to Detroit. These hit-and-runtactics kept the northwest frontier ablaze throughout the Revolutionary War andbeyond.No Post WarPause

The Treatyof Paris did not dampen the friction between the northwest tribes and the ever-increasingAmerican settlements that began to creep beyond the frontier. And Girty playeda role. For the next ten years, he was a tireless advocate for war against theAmericans at tribal councils. How much was his raw hate for his formercountrymen, revenge for past grievances, or merely him being an agent ofBritish policy, we will never know. But it was likely all the above.

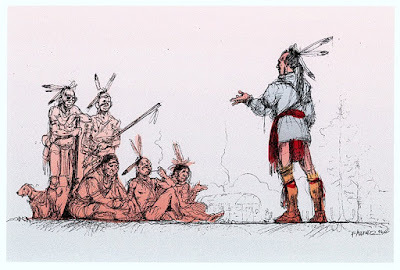

Girty took part in tribal councils

Girty took part in tribal councilsWar DrumsAlong the Miami

By 1791, thetribes of the Ohio country had united into a federation that pledged to checkthe American threat to their lands or die in the effort. The assembled warriorspossessed all the traditional cunning, skill, and bravery of their ancestorsbut had British training and weapons that made them a far more dangerous forcethan any of the Western tribes that rose to fame in the next century. Still,many leaders had decided to settle with the new government, but Americanincursions and the killing of Chief Little Turtle's daughter drove the tribesto war.

Little TurtleAn Army'sDestruction

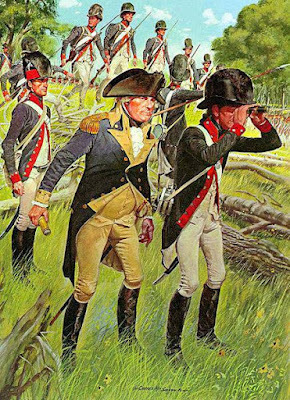

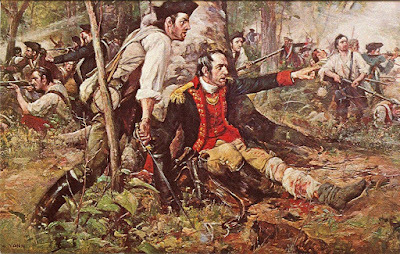

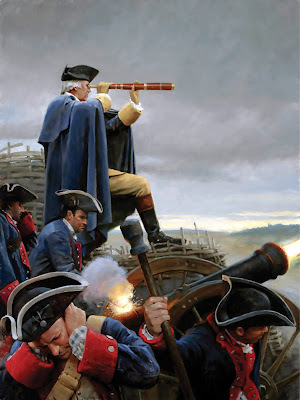

Little TurtleAn Army'sDestructionSimon Girty waswith Chief Little Turtle of the Miami and his war party when they evisceratedan American Army led by Revolutionary War heroes General Arthur St. Clair andRichard Butler at The Battle of the Wabash. The northwest was at the mercy of the war bands. Enraged,President Washington ordered the formation of a new army called The American Legionand placed it under the command of a war hero from eastern Pennsylvania, GeneralAnthony Wayne.

Battle of the WabashFallenTimbers

Battle of the WabashFallenTimbersSimon Girtymarched to face this new army with the War Chief Blue Jacket and his Shawnee, Ottawa, and many othertribes. In August 1794, Blue Jacket and Girty clashed with Wayne's AmericanLegion General Charles Scott's Kentucky Militia at Fallen Timbers. In the shortbut decisive battle of Fallen Timbers, Anthony Wayne crushed Blue Jacket's federation, and the tribesfinally sued for peace — a bitter pill for a noble people.

Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers

Anthony Wayne at Fallen TimbersEscape North

The Britishfinally evacuated Detroit in 1795. The long-held Great Lakes bases foroperations against the new American government were given up to the Americans bythe Jay Treaty. Still a wanted man, Girty was forced to move north to thesafety of Canada and worked for the British Indian Department in Amherstburg,Ontario. The elderly Girty, now borderline depressed and alcoholic, had to fleethe town when the Americans invaded in 1813. He returned after the Americanswithdrew and lived there until his death on 18 February 1818.

What can wemake of this controversial frontiersman? Well, for one thing, he had plenty ofcompany in the pantheon of savagery, of any color and on both sides. Beyondwell-known battles on the Atlantic seaboard, the American War for Independencewas a civil war and a clash of civilizations. The hundreds of raids, ambushes,and small-scale fighting were much more bitter than the European-styleengagements in the east. Simon Girty symbolizes the many men on both sides whoused savagery as a tool of war. Sadly, this pantheon continues to gain newmembers up to this day.

The Pantheon in 1836 by Jakob Alt

The Pantheon in 1836 by Jakob Alt

July 29, 2023

Clan Mother

The challenge with any study of espionage is the shortage of unclassified resources — it is the nature of clandestine work that it be kept secret. This is especially so when looking back to the time of the Yankee Doodle spies when almost all espionage activity was "off the books," with few reports or records kept. Spies were active in all theaters throughout the war, but determining who and what they did is challenging, requiring lots of "fill in the blank" and connect the dots analysis.

Spying on the Spies

Spying on the SpiesSavage War of Peace

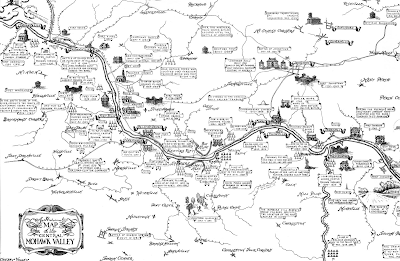

The American Revolution in the Mohawk Valley involved years of internecine conflict and small-scale combat that often reached a fever pitch. Patriot Whigs and Loyalist Tories went nose to nose in battles from a few dozen to a few hundred and rarely involved large-scale combat involving thousands. Throw six Iroquois tribes, Canadians, Continentals, and British regulars into the mix, and you have a bouillabaisse of conflict and turmoil. But unlike many other theaters of the war, the central New York region was never quiet. Instead, a continuous savage war of peace raged.

The Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley

The role of the native tribes added objective complexity to the struggle in New York. The powerful Iroquois nation was mainly in the camp of the British thanks to the excellent work of the Crown's Indian Agent, Sir William Johnson, and his son.

Sir William Johnson

Sir William JohnsonOf the Iroquois nations, the most powerful, warlike, and pro-British were the Mohawks, who controlled the easternmost tranche of the territory. Our subject is one of those Mohawks, a woman born, Konwatsi'tsiaiénni, but now known as Mary or Molly Brant, older sister to Joseph Brant, who became a Mohawk War Chief and British officer during the war for independence.

Youth in Two WorldsMolly Brant was born around 1736 in the Ohio Valley, although her family's ancestral home was the village of Canajoharie, on the upper Mohawk near Little Falls, New York. Her parents were Margaret (Onagsakearat) and Peter (Tehowaghwengaraghkwin), who were Anglicans. When Peter died while the family lived on the Ohio River, Molly's mother returned to Canajoharie with her and her brother Joseph.

Iroquois Village

Iroquois VillageBoth Brant children grew up in two worlds, developing fluency in English and becoming comfortable with English culture. Molly was schooled in the Mohawk Valley and, due to her command of English, accompanied twelve Mohawk tribal elders in a delegation to Philadelphia in 1755. Sometime after that trip, Molly became acquainted with the most powerful man in two worlds, famed British Indian Agent Sir William Johnson — her beauty and grace smote him. Johnson brokered all the deals involving the tribes and proved an honest broker who attended to the needs of the Iroquois and the white settlers in central New York. He was also rich.

Lady of the ManorBy 1759, the twenty-three-year-old Molly was officially listed in Johnson's records as his "housekeeper," but she was, in fact, his common-law wife — perhaps married by Iroquois custom. She would have seven children by him and functioned in all ways as the powerful Johnson's consort.

Molly Brant was the Lady of Johnson Hall

Molly Brant was the Lady of Johnson HallAnglo visitors who visited Johnson's estate, Johnson Hall, remarked on her beauty, delicate features, olive skin, excellent manners, and understated but commanding presence. In all but name, Brant was the Lady of the Johnson Hall estate.

The Clan MotherDuring her time with Johnson, she also rose to be a Clan Mother receiving the Mohawk name Tekonwatonti (Many Opposed to One). Molly led a society of Six Nations (Iroquois Confederacy) matrons. In the matriarchal hierarchy of the Iroquois, Clan Mothers wielded terrific power and influence, traditionally selecting and dismissing leaders. And could veto their decisions.

Clan Mothers wielded significant influence

Sir William died the year before Lexington and Concord erupted and plunged the colonies into open war with the Crown.

Loyal to the CrownMolly Brant and her brother Joseph remained committed Loyalists, devoted to the British cause. Joseph became a renowned Loyalist commander and Mohawk War Chief whose exploits vexed the patriots.

Chief Joseph Brant

Chief Joseph BrantHis sister's role was more ambiguous yet equally important. She provided food and ammunition to nearby Loyalist units. But most significantly — she passed valuable intelligence to her brother and other Loyalist and British leaders in central New York.

SpymasterAlthough little is recorded of this (for reasons mentioned above), she likely received reports on American movements in the Mohawk Valley from travelers, hunters, and traders who passed through her village.

Molly Brant: Mother Clan, Mother.Spy

Molly Brant: Mother Clan, Mother.SpyThe best example of this came in August 1777. British Lieutenant-Colonel Barry St. Leger's force of British, Loyalists, Canadians, and Indians had besieged the American garrison at Fort Stanwix (in today's Rome, NY). When the Tryon County militia learned of this, a brigade-size force marched west along the river to relieve the post.

Battle of Oriskany

Battle of OriskanyWhen Molly got wind of their movement, she sent word to St. Leger, who dispatched a force of Loyalists and Indian allies who set a well-executed ambush in the dense cypress forests near Oriskany. The relief column was sent reeling back with heavy losses, and its commander Colonel Nikolas Herkimer was mortally wounded.

Fort Stanwix

Fort StanwixIn retaliation, American-Allied Oneidas raided her village of Canajoharie, destroying it and nearby Fort Hunter.

On the RoadMolly moved her family to various Loyal Iroquois villages. Brant and her family lost most of their possessions. They took refuge at Onondaga near Syracuse, New York, the capital of the Six Nations Confederacy, first to Syracuse, then Cayuga, and finally Niagara.

Iroquois Village along the Mohawk River

Iroquois Village along the Mohawk RiverAt each of these, she proved a strong and effective proponent for the Loyalist cause, helping keep most of the Iroquois in the British camp. As a result, the British could use the Iroquois war bands to augment dwindling Loyalist and British forces in New York.

Iroquois War Band

Iroquois War BandResilient Leader

As the war dragged on in New York, the British and their Indian allies were gradually pushed west. The British called on Molly Brant to help lead the thousands of starving refugees fleeing the Americans for the protection of Fort Niagara — the last bastion in the state. She proved an able leader, organizer, and spokesperson for the tribes. Her power and influence grew among the tribes and the British authorities.

Fort Niagra: last bastion of British power in New York

Fort Niagra: last bastion of British power in New YorkOne British officer remarked of her influence on the tribes that "their uncommon good behaviour in great measure to be ascribed to Miss Molly Brant's influence over them, which [was] far superior to that of all their Chiefs put together."

A Separate PeaceBut when the Treaty of Paris was signed, the rug was pulled out from under the Iroquois and Loyalists of New York. The British made little effort to protect ancestral lands, leaving the Iroquois alone to deal with their enemies—it did not go well. Many of the Iroquois and all the Loyalists fled to Canada.

Treaty of Paris signing

Treaty of Paris signingA Bitter Nation

The Iroquois who remained turned bitter toward Molly and her British masters. Molly left the home the British had built for her on Carleton Island as it was now on the American side of the border. The Clan Mother moved to a village called Cataraqui and, with other Loyalists, established what became Kingston, Ontario.

A Grateful CrownThe grateful British did award her land and a pension sizeable enough to spurn overtures by the Americans to return to New York. They recognized the need for her leadership. But she was contemptuous of the people who had ravaged the Iroquois lands over eight years of bloody warfare.

Founding CanadianMolly Brant's family became prominent in Upper Canada. Five of six daughters married Canadian men. George, her surviving son, obtained a position in the Indian department. Her older son died fighting for the British.

At age sixty, the Clan Mother died in Brantford, Ontario, in 1796. Her precise burial site is not known, but many believe the good life-long Anglican lies somewhere under St. Paul's Church in today's Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Her legacy is one of a remarkable woman who cared for her family, clan, tribe, and nation in peace and war.

St. Paul's Church and Burial Ground

St. Paul's Church and Burial Ground

June 29, 2023

Yankee Doodle Tradecraft

The past few posts involved discussions of spycraft – general methodologies of intelligence activity. Though roughly synonymous with tradecraft, it is broader in scope than this post. Merriam-Webster defines tradecraft as “the techniques and procedures of espionage.” We will focus on selected techniques for this discussion. None are unique to the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies.

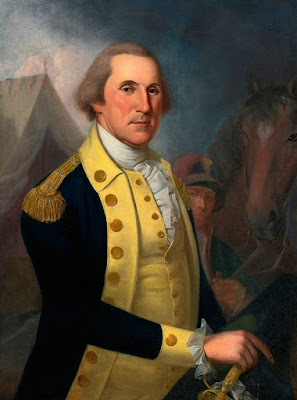

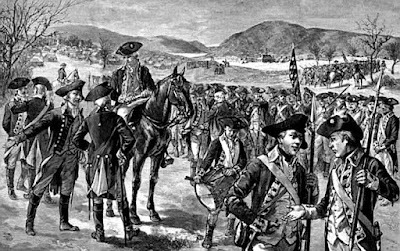

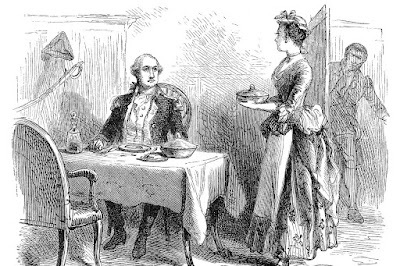

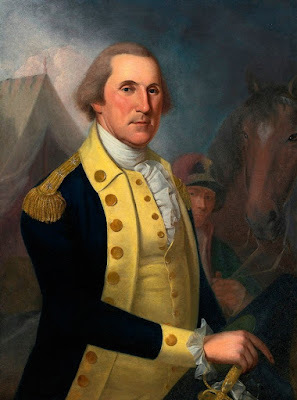

Washington as Spymaster

Washington as SpymasterWorld’s Oldest Profession?

Spying has existed long into antiquity. By the mid-19th century, almost all nations employed tradecraft in their intelligence activities. Formally organized intelligence services operated in the European capitals, especially in the major ones such as Paris, London, and Madrid. But on the battlefields of America, most intelligence activities were ad hoc and usually managed by the commander in loco.

The perfect venue for European espionage

The perfect venue for European espionageGeneral Washington famously took a particular interest in such matters, but nearly all commanders on both sides did as well – dispatching scouts, reconnaissance patrols, and spies. Some appointed officers to manage spy networks made up of one or more agents, sometimes called assets. Benjamin Tallmadge, a major of the Second Continental Dragoons, was one such handler who ran the Culper Ring in New York City and Long Island. During the Philadelphia campaign in late 1777, Washington’s agent handler was another Continental Army officer, Major John Clark.

Benjamin Tallmadge

Benjamin TallmadgeCover

The complexity of today’s high-tech and interconnected world makes cover activities extremely challenging. In the 18th century, when records were not well kept or even existent, a simple “legend” might prove sufficient to protect a spy. A legend refers to a person using a fake identity or credible story to infiltrate a target organization instead of recruiting an agent in place (behind enemy lines). Nathan Hale went behind British lines in New York in 1776 using a traveling schoolmaster as his cover. Both sides used very light cover, primarily by adopting pseudonyms. Records were crudely maintained and identified, other than letters of introduction.

Nathan Hale using schoolmaster cover

Nathan Hale using schoolmaster cover

In 1778, American Captain Allan McLane volunteered to spy on the British garrison at Stony Point, a fort on the Hudson south of West Point. McClane dressed as a “country bumpkin” whose cover was that he was escorting a lady to visit her son at the fort. He returned safely with valuable intelligence for General Washington.

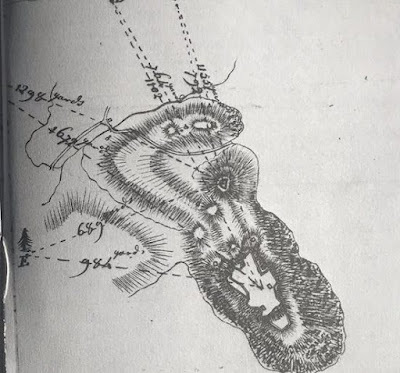

Defense plans for Stony Point

Defense plans for Stony PointReal or Concealed?

Fans of James Bond and other modern spy thrillers are familiar with concealment devices to hide artifacts of espionage, messages, plans, or maps. These include devices such as hollowed-out coins, books, or other items. Revolutionary War devices could be elementary, as manifested by British Major John Andre’s squirreling away plans for West Point’s defense in his shoe.

Major Andre - shoeless spy

Major Andre - shoeless spyA more sophisticated plot by General Henry Clinton failed in 1777 when he dispatched an officer named Daniel Taylor up the North (Hudson) River to inform General John Burgoyne of his plans. The message, written on silk, was hidden in a silver ball made to look like a musket ball. The unlucky Taylor was captured, and he swallowed the ball during questioning. His interrogators caught him in the act, and the application of emetics soon revealed the device.

Messages could be secreted in silver balls Broadcasting

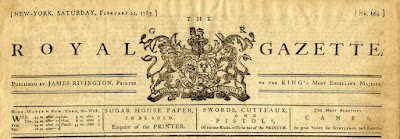

Messages could be secreted in silver balls Broadcasting In the 20th century, spies might be equipped with a one-way voice link, a radio-based communication used to communicate with agents in the field typically (but not exclusively) using shortwave radio frequencies. Newspapers provided a similar capability in the 18th century. Classified ads were an advantageous way of communicating. Newspapers such as New York City’s Rivington’s Gazette served this purpose for the British and Americans.

Rivington's Royal Gazette

Rivington's Royal GazetteCryptography

The use of special techniques for secure communication dates back to antiquity. By the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies, codes and ciphers of various kinds were employed.

Letters of the alphabet replace other letters to hide the message's contents. The sender and receiver must have the same key, which can be used more than once, or for the most enhanced security, a one-time pad, which changes the key with each message. In some cases, a network might have its own template in the form of a book to provide the cipher’s key.

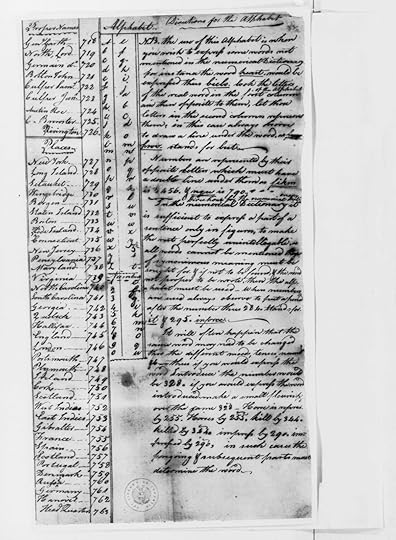

Code of Culper Ring

Code of Culper RingGeneral Washington used a number and letter substitution system made famous by the Culper Ring operating in New York and Long Island. For instance, 38 meant attack, 192 meant fort. New York was 727, etc. Sometimes innocuous words were left in the message, as they could not reveal their true meaning.

Another secret communication method was working off a published book or dictionary, pointing to a word on a page and line to decode the signal. A popular book or dictionary essentially hides in plain sight and poses no threat if it falls into the wrong hands.

SteganographyThe art or practice of concealing a message, image, or file within another message, image, or file is a high-tech endeavor today. But 18th-century intelligence often used hidden messages. Usually, a real message was embedded in a book, newspaper, letter, or some other cover text.

Hidden in a book

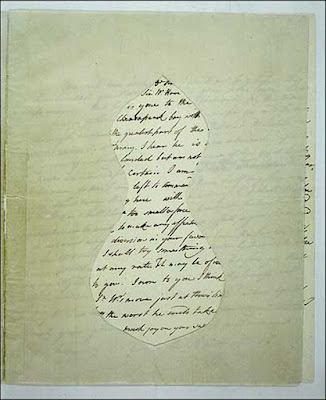

Hidden in a bookThe British used the technique of crafting letters within the text in which the secret message was revealed when a paper template called a “mask” was applied. Within the template, the actual words of the message could be read. The information was written in the shape of an hourglass.

Masked Letter

Masked LetterInvisible ink grew in use. Lemon juice provided the earliest application, but later on, a special liquid called stain enabled secret writing to be made visible only to the recipient who possessed the stain. Sir James Jay, the brother of the Revolutionary leader and head of New York’s Committee for the Detection of Spies, John Jay, invented it in London. Fortunately for the Americans, Sir James secretly shipped a bottle of stain to his brother, who ran counterintelligence activities. Washington made good use of this new “high-tech” ink, usually penned in the open space between the lines of a routine letter or a book.

John Jay

John JayCutouts

Espionage services used cutouts, typically someone not under suspicion, to pass information to and from agents. Cutouts have limited knowledge of the final destination or the spy’s identity, providing added security should the cutout fall under suspicion. Colonial taverns and coffee houses offered ideal venues for this. Other establishments, such as American spy Hercules Mulligan’s tailor shop in New York, may have played such a role.

Tailor Shop or Spy Central?

Tailor Shop or Spy Central?Dead Drop

The dead drop exchange is still a method of espionage tradecraft used to pass items between two individuals using a secret location. Dead drops permit the exchange of information while avoiding a personal meeting. These are usually secret locations at remote sites (sometimes in plain sight )for leaving notes or items for later recovery. The Culper Ring used a box buried on AbrahamWoodhaull’s farm, where Austin Roe would deliver intelligence gained at his New York tavern.

Returning from a dead drop on Long Island

Returning from a dead drop on Long IslandThe flip side is the “live drop,” where two agents meet to exchange items or information. The same ring used Long Island’s north shore coves as dead drops where Caleb Brewster’s whaleboat could slip in, and he would retrieve the messages.

EavesdroppingToday this includes electronic surveillance, wiretaps, and cyber collection. During Revolutionary War times, eavesdropping was secretly listening to the conversation of others without their consent, typically just out of sight or behind closed doors. Lydia Darragh got wind of a British plan for s surprise attack on General Washington’s army, which was “observing” the British garrison in Philadelphia. General Howe was using her home as his headquarters, and her presence gave her the access needed to accomplish this.

Lydia Darragh in action

Lydia Darragh in actionSurveillance

Monitoring behavior, activities, or anomalies is a simple but effective technique. Surveillance was possibly the most often used collection activity during the American Revolution. The pro-British Loyalists and American patriots were often intermixed and kept tabs on each other, watching for suspicious or threatening activities. Scouts and patrols also surveilled enemy forces, always from afar. In 1775, Paul Revere’s spy network, known as the Mechanics, had surveillants throughout Boston and the surrounding area to report on British activities.

The Mechanics reported on the British Boston garrison

The Mechanics reported on the British Boston garrisonFront Organizations

These are entities created and controlled by another organization, such as intelligence agencies. The intent is to avoid attribution to the organizing entity – plausible denial. They can be in the form of a business, a foundation, or another organization. The most famous of these during the Revolutionary War was Rodrigue & Hortalez et. cie, a front company established by Pierre Augustine de Beamarchais, a clockmaker and playwright, who had the ear of the King, as well as France’s Foreign Minister, comte de Vergennes. This trading company shipped surplus French military goods and other critical supplies to the colonies in exchange for American products such as tobacco. The American cause would have likely collapsed without this covert aid.

Beamarchais - playwright and covert action mastermind

Beamarchais - playwright and covert action mastermindAsk Me Anything

Both sides used military interrogation extensively. An interrogation is an interviewing approach employed by police, military, and intelligence agencies to elicit valuable information from an uncooperative suspect. Interrogation involved various techniques, ranging from developing a rapport with the subject to repeated questions, sleep deprivation, or, in some countries, torture. Both sides suffered from deserters who willingly gave up military information during the Revolutionary War. The most ruthless interrogations occurred in the internecine conflict between patriots and Loyalists. This civil war within the American War for Independence was rife with aggressive and brutal interrogation of prisoners.

Interrogations could be brutal

Interrogations could be brutalBlack Chamber Operations

Intercepting diplomatic correspondence originated in Europe in the early 18th century, usually by co-opting a post office. During the American Revolution, both sides employed such covert actions by intercepting mail carried by normal postal means, express riders, or couriers. This was done secretly when possible, with the letter(s) carefully re-sealed and stamped. Washington and the British in New York City used this approach extensively, co-opting couriers and messengers. Since patriots and Loyalists abounded and lived among each other, there was no shortage of people who could be convinced to reengage in such a risky endeavor.

Courier with a message - is it true or false?

Courier with a message - is it true or false?During the onset of the Yorkton campaign in 1781, General Washington exploited the use of intercepted messages by British General Henry Clinton’s New York garrison by planting false information that was allowed to fall into enemy hands. The report helped paint a false story – an upcoming invasion of New York. This operation enabled the French and Americans to steal a march on Clinton as they headed south to Yorktown and victory.

Surveilling Yorktown

May 29, 2023

The Indispensable Spymaster

"There isnothing more necessary than good Intelligence to frustrate a designing Enemy,and nothing requires greater pains to obtain." George Washington

As commander in chief of the Continental Army, GeorgeWashington was much more than a general. He was the undeclared head of theUnited States with concerns beyond the usual man, equip and train mandate ofcommanding generals. He was a figurehead but also influenced the ContinentalCongress and state policies through persuasion. His concerns involved everyaspect of the aforementioned mandates, making him the Army's chief logistician,personnel director, organizer, and trainer in many ways. And he was the chiefstrategist and operational planner for all the Continental Army's departments.

The Indispensable Spymaster

The Indispensable Spymaster

It must be remembered that military staffs were not therobust teams of highly skilled planners and actions officers that developed inthe French and Prussian armies of the next century—just a few aides de camp andorderlies reviewed and prepared correspondence on a day-to-day basis. For bigdecisions, Washington consulted with Congress and senior military officers. Butthe daily management, often via "Orders of the Day" and "GeneralOrders," rested with Washington and a handful of men around him.

Planning operations

Planning operations

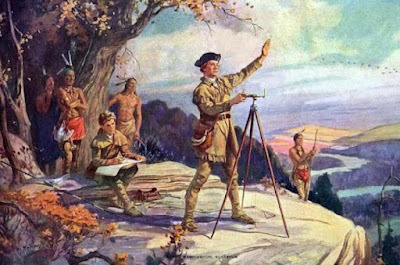

So it is no surprise that Washington added to his burden byserving as the Continental Army's spymaster. It was a job he took mostseriously. And why not? He was a trained and practiced surveyor, a professionrequiring an understanding of terrain – knowing the land, waters, fields,forests, and mountains. He traveled deep into the American frontier andunderstood the time and space considerations needed to plan venturessuccessfully. And most importantly, his career was launched by a spy mission.

Surveying - the handmaiden of intelligence

Surveying - the handmaiden of intelligence

In 1753, Virginia's Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent a youngMajor Washington to spy on the French outposts deep in the upperOhio River valley. Washington honed his recruiting skills by engaging theservices of experienced guides and interpreters, one of whom was an explorernamed Christopher Gist. In the densely forested mountains near the French FortDuquesne (today's Pittsburgh), he met a Seneca chief named Half-King, who guidedWashington to a meeting with the French.

Robert Dinwiddie

Robert Dinwiddie

Washington elicited a trove of data such as fort locations,numbers of canoes and bateaux, etc. But the essential element of information,Dinwiddie's purpose for the expedition, was discovering French intentions. Thesewere to control the entire Ohio Valley and surrounding territory to maintain a monopolywith the tribes in the interior. After eighty days of slogging throughsnow-filled mountains and canoeing along icy rivers with Gist, the young spyarrived in Williamsburg and gave the governor a detailed written report.

Lieutenant Colonel Washington

Lieutenant Colonel Washington

Ironically, his professional work resulted in Dinwiddiesending him back out the following year at the head of a military contingentaimed at buttressing Virginia's claim to the territory. Lieutenant Colonel Washington's second expedition was adisaster that led to the French and Indian War in America and the Seven Years' War in Europe. Indeed, the Frenchand Indian War provided Washington with the springboard to command theContinental Army in 1775.

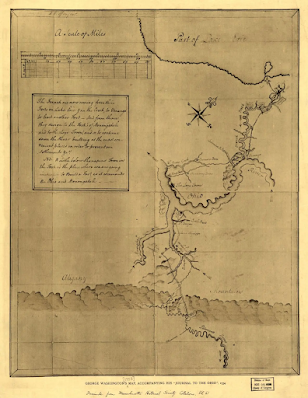

Washington's map of Ohio Valley 1754

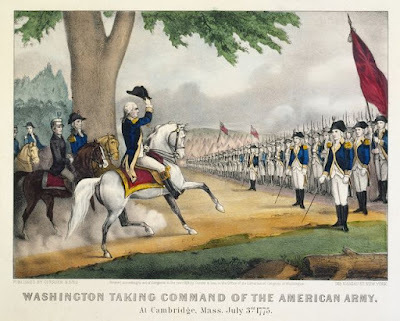

Washington's map of Ohio Valley 1754By the time Washington assumed command at Cambridge, Massachusetts,he had the skills and experience to plan and implement intelligence activities. He spent the latter years of the war commanding the Virginia Militia Regiment, which was charged with protecting the Shenandoah Valley from French-inspired Indianincursions.

The weakness of Washington's Army for most of the war forcedhim to wage a war of so-called Fabian tactics, which relied on accurate intelligence,military security, and tactical deception to level the playing field with the British. The Boston campaign provides a helpful example.

The Continental Army outside Boston was initially weak

The Continental Army outside Boston was initially weak

On taking command, he learned the Continental Army wasdangerously low on gunpowder. Washington employed strict security to protectthe new Army's biggest secret. He took great pains to cloak this from theBritish until he had an adequate supply. He sought intelligence on the Britishactivities in Boston, but his critical knowledge requirement was theirknowledge of the gunpowder problem.

Low supplies of gunpowder threatened the Army

Low supplies of gunpowder threatened the Army

During that period, a spy was discovered at the highestlevels – Doctor Benjamin Church, Chief Surgeon of the American Army. Secretcorrespondence with the British commander, General Gage, revealed Church'sdouble game. Church claimed he was actually trying to convince the British ofthe Americans' large stocks of gunpowder. If true, this might have been anexcellent deception operation. But a military court convicted him. Was that tooa ruse? Church disappeared at sea after his conviction, but many years later,historians discovered secret British files that proved his espionage. But was itespionage or just a good double agent operation? This affair may have promptedhis obsession with enemy spies in his camp, a fixation that continuedthroughout the eight year war.

Doctor Benjamin Church

Doctor Benjamin Church

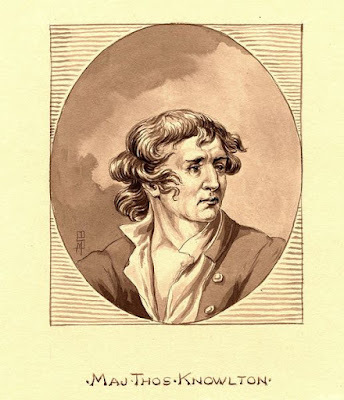

During the remainder of the war, George Washington kept atight hand on the spies and spy networks that swirled around the ContinentalArmy: Nathan Hale's strained mission, the tactical collection activities ofKnowlton's Rangers, and later the 2nd Continental Dragoons. Othersinclude Hercules Mulligan reporting from occupied New York, Lydia Darragh doing the same from Philadelphia,and of course, the Culper Ring in New York City and on Long Island. And therewere many other spies and networks that still go undiscovered.

Counterespionage was another area of Washington's personal attention. He was greatly vexed by Loyalists spying for the British such as New Jersey'sJames Moody. The Sergeant Hickey Affair resulted in the breaking up of a ringand a potential assassination plot. The most notorious espionage challenge wasposed by British Major John Andre's recruiting of arguably America's greatestwar hero- Major General Benedict Arnold. Washington was there when Arnold wasuncovered and personally directed the countermeasures, which included a parleyto exchange Andre for Arnold, dispatching an agent, a Virginia Sergeant namedJohn Champe, to kidnap the treasonous general, and appointing Andre's court martialand approving his death sentence.

The capture of Major Andre

The capture of Major Andre

Washington employed deception and military (or operations)security throughout the war. He had to deceive the British about his Army'sstrength (or lack of it) and its intentions. There were many successes andfailures as both sides engaged in deception and counter-deception. The stakeswere high – the war's outcome could turn on their successful implementation.

Military patrol in winter

Military patrol in winter

The most celebrated of these activities was Washington'sleveraging his well-known and long-standing desire (some might say obsession)to capture New York City. In the summer of 1783, Washington finally agreed toFrench General Rochambeau's plan to join a French fleet on its way to theChesapeake Bay and attack General Charles Cornwallis's Army on Virginia'sYorktown peninsula.

General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau

General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau For it to work, the British needed to be dissuaded from sending aid to Yorktown. He orchestrated a series of intelligence measures toplant the idea of an imminent Franco-American attack on the New York garrison. Feints by bodies of troops, deliberately lost dispatches, and the whispers of spiesconvinced British General Henry Clinton long enough to delay sendingreinforcements to beleaguered Cornwallis in Yorktown.

Spy at work

Spy at work

Even as the French and Americans marched south, their routewas designed to appear like an envelopment of the city until the very lastminute. When Clinton realized he had been humbugged, it was too late to help Cornwallis. By the end of October, the British had surrendered inYorktown. Clinton's military options were dwindling, and the British governmentfell, bringing in an administration more sympathetic to negotiations.

Washington's deception steals a march on Yorktown

Washington's deception steals a march on Yorktown

The great spymaster succeeded in leveraging an early form ofgray zone warfare. Most of these activities were kept secret long after the war,and very few official records were maintained – for obvious reasons. In anation of divided loyalties, the lives of spies are always in peril. The 18th-century zeitgeist that emphasized "honor" held spies in great disdain. YetWashington occasionally mused about those who risked lives and reputations forlittle reward or acclaim. They could not receive pensions or fame. The case ofNathan Hale is a possible exception, and that was for propaganda purposes.

Execution of Nathan Hale

Execution of Nathan Hale

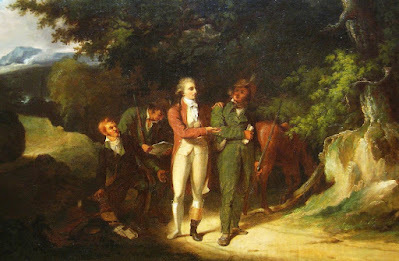

The shadow war waged during the American Revolution was critical to its success. George Washington realized that. It is said he visited random citizensfor some quiet conversation during his post-war travels around the countrywhile President. Ultimately, all he could reward them with was his personalthanks. For the shadow warriors who risked life and honor, a tip of the hatfrom the most extraordinary man of the century was enough.

The Indispensable Man met many of his spies

The Indispensable Man met many of his spies

April 30, 2023

Spycraft and the Road to Rebellion

This blog post might better be called "Back to the Future." Not because it is about the iconic 1980s time travel film and its subsequent franchise but because we are traveling back to the original premise of this blog and the Yankee Doodle Spies book series, espionage.

The American Revolution was, for many years, a war inthe shadows. Since shortly after the 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the French andIndian War, a slow-fused powder keg of resentment, misunderstanding, andill-conceived policies drove a wedge between the North American Englishsettlers and their cousins back home. Disputes over taxation, governance,Indian relations, western settlement, and trade began percolating.

French and Indian War

French and Indian WarThe governance issue, in some ways, was a mirror imageof the Whig–Tory divide in Britain, but it was mostly a uniquely Americanproblem. What should be the relationship between a home country and itscolonized overseas possessions when those possessions had evolved and maturedinto growing and prosperous polities in their own right?

Parliament

ParliamentBy 1775, Great Britain's population is estimated at around8,000,000 people. But the American colonies had grown from a handful ofsettlements clinging to the Atlantic coast in the early 17th centuryto a land of 2.500,000 people, with some frontier settlements over 100 mileswestward.

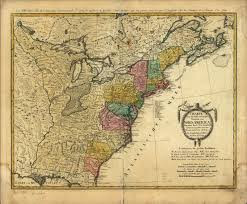

The colonies stretched as far as the Appalachians by mid 18th century

The colonies stretched as far as the Appalachians by mid 18th centuryThe standard of living in the colonies rivaled anyEuropean country. Agriculture was king, but tradesmen and merchants prosperedas maritime commerce grew between the colonies, the West Indies, and someEuropean states.

American colonies were prosperous due to farming and trading

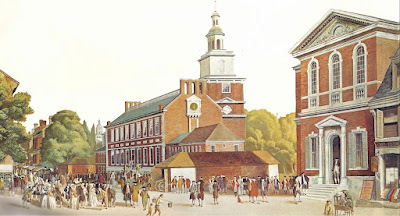

American colonies were prosperous due to farming and trading The cities of Newport, New York, Boston, Philadelphia,and Charleston were increasing in size, wealth, and culture. Philadelphia wasthe third largest city in the British domains after London and Edinburgh. Thegreat distances between these centers made coalescing around shared ideas andaction challenging.

Philadelphia was the third city in the British Empire

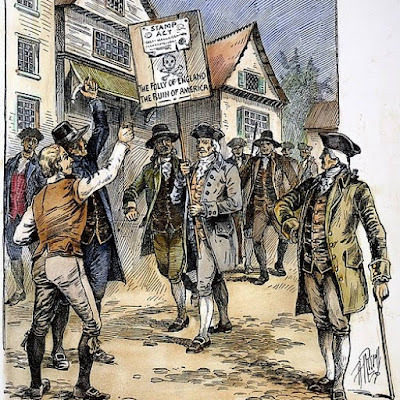

Philadelphia was the third city in the British EmpireA series of British policies beginning in the 1760sstarted to grate on many. Political unrest brewed at first with the educated andbusiness classes, but with each step to quell the unrest, it began to seep intothe rest of the populace. With political turmoil came political organization.

Resistance was secretly organized but openly practiced

Resistance was secretly organized but openly practicedPolitical leaders throughout the colonies secretlystood up committees to avoid action by the royal authorities and their loyalistsupporters. These organizations, which occurred at local, county, and colonylevels, communicated political thought and coordinated activities within andamong the colonies.

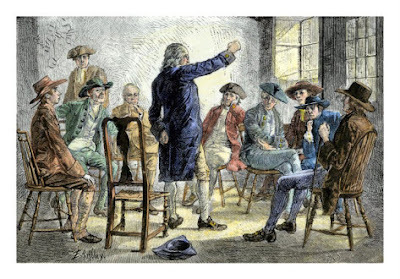

Committees met secretly

Committees met secretlyBy 1775, most colonies had Committees of Correspondence(communications and propaganda), Committees of Safety (local defense andmilitia), and other committees for various purposes. Many later leaders duringthe American Revolution cut their teeth by participating in the committees,which were the precursors to future American governance.

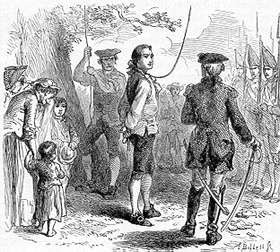

America's future leaders learned their business while organizing resistance

America's future leaders learned their business while organizing resistanceAs the Royal Governors stepped up the enforcement ofBritish policies on the colonies, the committees learned to operate covertlyand sometimes clandestinely. Groups like the Sons of Liberty or The GreenMountain Boys developed. But those with unswerving loyalty to the king, the loyalists,also countered these groups, often reporting on their activity and sometimestaking action.

Sons of Liberty taking action

Sons of Liberty taking actionThe advocates for colonial rights waged a politicalwar, often in secret, sometimes in the open. The committees developed protocolsfor hiding their actions and intentions and identifying those supporting the Crown.Political agitation morphed into armed insurrection (especially inMassachusetts) with the outbreak of combat at Lexington and Concord and thesiege of British-occupied Boston.

Insurrection became open rebellion when the British raided Lexington & Concord

Insurrection became open rebellion when the British raided Lexington & ConcordThe stakes were exceptionally high between the loyalistsand the rebels, whose mutual disdain was far greater than the disdain betweenthe patriots and the British. By then, both sides were using informants againsteach other. They developed techniques for identifying possible spies and forspying.

Spying in a tavern

Spying in a tavernThe covert and clandestine measures that evolved over a decade ofsecret meetings, passing information covertly, and discreetly building up politicalnetworks and organizations, would now be used in an open rebellion and then awar for independence that stretched from the backcountry of the AppalachianMountains to the capitals of Europe.

Secret couriers pass information critical to orchestrating resistance and rebellion

Secret couriers pass information critical to orchestrating resistance and rebellionNext, we will look at some of the tradecraft, which Icall spycraft, used during the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies.

March 31, 2023

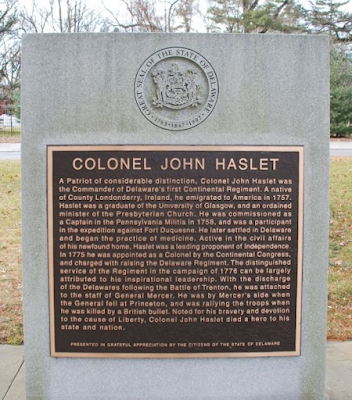

Delaware Patriot

When I began writing the Yankee Doodle Spies Blog sop many years ago, one of the first patriots I wanted to profile was one from Delaware. An immigrant preacher who left his home in Ireland for a better life and fought in two wars, one for and one against Britain, this underrated first patriot is John Haslet.

A Londonderry ManBorn around 1727 in Dungiven, near Londonderry, Ireland, this son of a tenant farmer grew up to be a religious man and, when required, a fiery leader. As a young man, he traveled to Glasgow, Scotland, and studied Divinity. He completed his studies in 1749, sailed home, and soon married. His bride was Shirley Stirling, daughter of a preacher. John was ordained a Presbyterian Minister in 1752 and, later that year, preached his first sermon to his new congregation at Ballykelly. Around that time, the Haslets had their first child, Mary (or Polly).

Preaching

Preaching

The year 1757 was one of tragedy and transformation for Haslet. Shirley lost their second child and died giving birth. Shortly after, Haslet decided to emigrate. In a not-uncommon practice at the time, he left young Polly in the care of his brother and sailed for America and a new life in a place called Delaware. The young widower quickly remarried there, taking Jemima Molleston as his second wife.

Against the French and IndiansHaslet joined the Pennsylvania militia. His University of Glasgow degree and experience speaking and inspiring his congregations marked him a leader, and he attained the rank of captain in short order. The French and Indian War raged when Haslet reached America. The campaign to drive the French from the frontier took Haslet and his militia company to western Pennsylvania, where they fought in the 1758 Battle of Fort Duquesne.

Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne

The war ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Haslet returned with his company to Delaware. He and Jemima settled in Milford, where he established a medical practice and purchased a property called "Longfield." John and Jemima would have four children. In addition, his daughter Polly immigrated to Delaware in 1765. An ideal life as a country doctor and farmer lay ahead.

From Friction to FightingBut the political friction following the war would sizzle into armed resistance, and Haslet was drawn into it, later becoming a proponent for independence from Britain. The Continental Congress appointed him a Colonel and commander of the Delaware Regiment (sometimes called the Delaware Blues), one of the largest (800 men) and the best uniformed and equipped regiment of the Continental Army. Their blue jackets with white waistcoats and breeches set the standard for all the Continental Line regiments.

Haslet's Regiment leaves for war

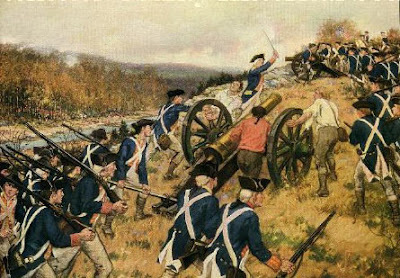

Haslet's Regiment leaves for warValor on Long Island

John Haslet's regiment marched to New York and into the defense works on Long Island in the late summer of 1776. General George Washington had occupied the city, but the British armada under Lord Howe sailed south and descended on Staten Island before invading Long Island at Brooklyn's Gravesend.

When the British surrounded the Americans, Haslet's regiment and First Maryland held firm against the onslaught. At the high point of the slugfest, Lord Stirling, an American General, and Scottish peer named William Alexander took command of the two regiments and led them in a series of gallant charges against British General Cornwallis's regulars.

Haslet's Delaware Regiment faces British regulars on Long Island

Haslet's Delaware Regiment faces British regulars on Long Island

Absorbing volley after volley from the red-coated ranks, the two regiments were torn to shreds. But their discipline and sacrifice allowed the remainder of the American army to flee to the safety of the defense works near Brooklyn Heights. This action is a critical event in my novel, The Patriot Spy. Ironically, Haslet and the Maryland commander, Colonel John Smallwood, were on court martial duty in New York City and only returned as the battle ended.

Colonel John Smallwood

Colonel John Smallwood

Haslet and his regiment served gallantly throughout the following months as the Continentals were driven from New York City. During the retreat, Haslet and his men trounced a corps of Loyalists at Mamaroneck.

At White Plains on 28 October, Haslet and Smallwood stood gallantly with their regiments on Chatterton Hill. When the militia they were sent to reinforce broke and ran, the two Continental regiments stood their ground until enemy numbers and firepower forced a withdrawal. But the stand on Chatterton Hill robbed General Howe of a complete victory, and the Americans would live to fight another day.

Chatterton Hill

Chatterton Hill

General Washington's army was on the run for the next two months. Fort Washington fell, and his men abandoned Fort Lee as they beat feet across New Jersey towards the Delaware and Pennsylvania, where Washington hoped to regroup and make a stand. Haslet and his men fought many small battles - skirmishing during a "fighting retreat" that reduced the Delaware Regiment to no more than 100 "effectives" – men capable of fighting by the time they crossed the Delaware River to join the main army.

War on the Run

War on the Run

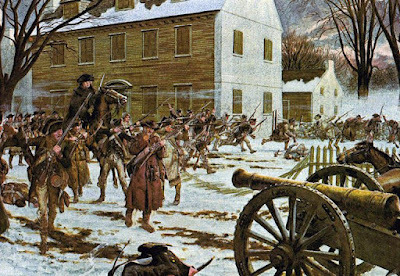

Knowing he needed to strike in days, Washington launched his famous Christmas surprise attack, crossing over the ice-clogged Delaware River on the night of 25 December 1776. The army trudged the nine miles under a black and cold sky to their objective: the over one thousand-string Hessian garrison at Trenton. Although barely two companies strong, Haslet and his men were in the van. After a bitter but short exchange of musket and artillery fire, the garrison surrendered, giving Washington one of the great victories of the war. Before Haslet had time to refit, enlistments were expiring, as was the case throughout the army.

Taking Trenton

Taking Trenton

Days later, the army was back at Trenton, defending a low ridgeline behind a creek south of Trenton and waiting for the British counterstrike of more than 5,000 fresh redcoats under an angry General Cornwallis. A late afternoon firefight on 2 January 1777 caused Cornwallis to stand down and strike with all his force the following day. But Washington stole a march and sent his army on an 18-mile night march around the British to attack their supply base at Princeton.

Holding Assunpink Creek

Holding Assunpink Creek

The dawn of 3 January broke bright but cold with snow covering fields and roads. Colonel Haslet's regiment was now a handful of officers. Months of fighting coupled with expired enlistments had melted his regiment away. But Haslet's experience and capable leadership were vital, so Washington named him second in command to General Hugh Mercer, his best commander.

General Hugh Mercer bayonetted at Princeton

General Hugh Mercer bayonetted at Princeton

Mercer's division was the vanguard and marching through William Clarke's orchard when two crack regiments of British regulars unleashed a horrific series of volleys in which Mercer's horse was shot from under him. Mercer sprung to his feet and drew his saber as the wave of red closed on him. When he refused to be taken prisoner, they clubbed him and then bayonetted him while he lay helpless in the snow. He died of his wounds.

The Field of HonorSeeing Mercer go down, Haslet took command of the remnants. But just moments later, a curtain of lead filled the air, and a musket ball struck him in the head. The remaining troops began to waver, but General Washington rode into their midst and rallied them. Then, combined with reinforcements, they drove the British from the field and took Princeton. The gallant John Haslet died on the field of honor like his commander, Hugh Mercer.

Washington rallying the troops

Washington rallying the troopsWashington's Loss, America's Loss

The history books mark Princeton as a victory. But the loss of Mercer and Haslet robbed Washington of two of his most able lieutenants, whose talents the commander-in-chief would sorely miss over the next five years of war. Mercer is duly honored, but Haslet, being second in command and from a small state, rarely gets much mention. I number John Haslet among the many unsung greats whose early death deprived the Continental Army and the future United States of leadership, integrity, and love of country.

Delaware's SonThe son of Delaware was buried outside his home state and laid to rest in the First Presbyterian Church's graveyard. Not until an Act of the Delaware Assembly was passed in 1841 were his remains transferred to the Presbyterian Cemetery in Dover, Delaware. But it took until 2001 for his state to honor him with his own monument at Princeton.

Haslet Monument at Princeton

Haslet Monument at PrincetonFebruary 26, 2023

Best in Battle

This month I am making another effort to highlight a historical character in my Yankee Doodle Spies novel, The North Spy. The character in question was one of a well, questionable character – Benedict Arnold.

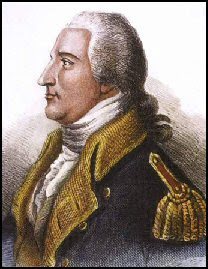

Major General Benedict Arnold

Major General Benedict Arnold

The name, Benedict Arnold, is now synonymous with perfidy and outright treason, and he is the most tragic figure of the American War for Independence. But the story of Benedict Arnold is a tale of two men. His brilliance, iron will, courage, and creative flare for action, combined with an oversized ego, an avaricious streak, an easy-to-anger, and a quick-to-affront personality, led to trouble. But this post will focus on his life, culminating with the battles at Saratoga in 1777, the finale of The North Spy, the turning point of the American War for Independence, and the high water mark of Benedict Arnold’s career.

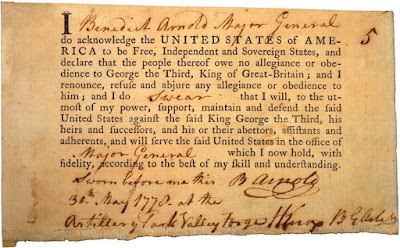

Benedict Arnold's Loyalty Oath

Benedict Arnold's Loyalty Oath

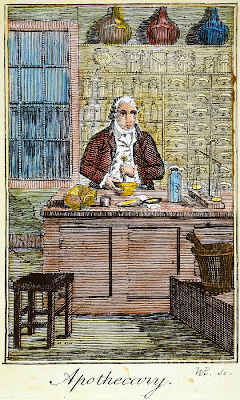

Norwich, Connecticut, begins this tale. Benedict Arnold was born there on 14 January 1754. His early life did not go well. Arnold’s father, Benedict Arnold III, was a successful businessman and descendant of one of Rhode Island’s first governors. Arnold had an excellent early education and was headed for Yale and his father’s mercantile business. But his father became an alcoholic, and things deteriorated in the family, with siblings dying (he was the second of six) and his father ill. But his mother, Hannah (nee Waterman King), connected him with an apprenticeship in her cousin’s apothecary and mercantile business.

The French and Indian War gave the sixteen-year-old a chance to break away. He joined a Connecticut regiment and marched to New York to help fend off the French. He was at Albany but then went north to Lake George. However, after the French seizure of Fort William Henry, the regiment returned south, and Arnold left the unit and the war.

Fort William Henry

Fort William Henry

Things turned around for him in civilian life. By 1762 he had his own pharmacy and bookshop. He proved shrewd and diligent in his business dealings and quickly prospered. Arnold made enough money to buy back the family property his father had lost. Then he resold it for a profit, using his cash to buy an interest in a trading company with three New England schooners plying the West Indies. He had his sister Hannah move to Norwich to manage his shop so he could devote full time to the trade, sailing to Canada and the West Indies as a ship’s master. Arnold’s personal life improved during this period. He married Margaret Mansfield, daughter of the local sheriff, and they had three sons before she died in 1775.

Schooner at Sea

Schooner at Sea

Although not a political polemicist, The Stamp and Sugar acts of the mid-1760s led him to join the Sons of Liberty and turn to smuggling to evade the unjust taxes. When the War broke out in April 1775, he raised his own militia company and marched to join the New England Army assembling outside Boston. He soon convinced the Committee of Safety to promote him to colonel so he could go to Fort Ticonderoga in New York to seize the critical fortress from the British. On the way, he found that Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys were intent on the same objective. The two strong personalities struck an uneasy alliance, and they quickly captured Ticonderoga and its sister fort at Crown Point.

Arnold takes Ticonderoga

Arnold takes Ticonderoga

After Ticonderoga fell, Arnold’s shipmaster instincts kicked in. He commandeered a boat and sailed north up Lake Champlain, where he raided the town of Saint Johns, Quebec. Sensing the defenses in Canada were weak, Arnold suggested a Quebec expedition to General Washington. The commander-in-chief approved Arnold’s plan to lead a division north through the Maine wilderness to strike the city of Quebec from the south.

Rabble in Arms

Only a leader with Arnold’s iron will and ruthless energy could conceive of, much less lead 1,100 men through the vast and desolate wilderness enshrouded in the cold of late winter. Many did not make it. Read Kenneth Roberts’s 1933 novel, Rabble in Arms for a look into the details of the journey. On 7 November 1775, some 700 half-starved and ragged survivors made it to the Plains of Abraham outside the fortified city. Lacking artillery, Colonel Arnold’s men settled in for a siege. Fortunately, another expedition through New York and Montreal, led by General Richard Montgomery, joined Arnold a month later.

Arnold's Expedition through Maine

Arnold's Expedition through Maine

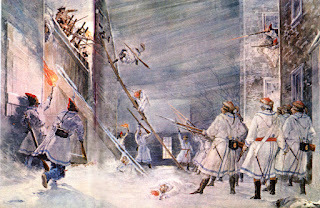

With enlistments expiring the following month, Montgomery and Arnold wasted no time launching an attack. On 31 December, they stormed the city in two columns in blizzard conditions. Montgomery was struck by a blast of grapeshot from the defenders’ guns and later died. Arnold suffered a leg wound. The first such injury would later present him with a limp. The wounded Arnold assumed overall command and maintained the siege, now as a Brigadier General, a rank conferred by Congress before the failed assault.

Storming Quebec in a Storm

Storming Quebec in a Storm

With spring, British reinforcements arrived, and British Governor General Guy Carleton began a series of attacks on the dwindling and undersupplied Americans. Arnold led a gallant retreat south, regrouping forces on the southern shores of Lake Champlain. When he learned Carleton was transhipping warships from the Saint Lawrence to the lake, he began a desperate effort to scrounge and assemble boats of all kinds to meet the naval threat that he knew was coming.

Governor General Guy Carleton

Governor General Guy Carleton

In a tour de force of leadership and resourcefulness, Arnold had a small motley squadron of gunboats ready for Carleton’s October attack, which was stage one in a planned move to Albany aimed at dividing the colonies. The mighty British and desperate Americans clashed at Valcour Island during 11- 13 October. Carelton’s ships smashed the Americans. Although New York and a total victory were at his feet, Arnold’s actions delayed Carleton’s timetable. Rather than risk a supply issue late in the campaign season, he withdrew to the lake’s northern shores until spring, when he planned to finish the job. He would never get the chance. Benedict Arnold had saved the Cause.

Battle of Valcour Island

Battle of Valcour Island

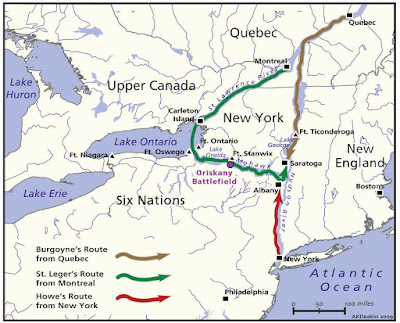

By the following spring, General John Burgoyne had arrived at Quebec with reinforcements and orders, placing him in command of the 1777 offensive to complete Carleton’s failed job. After sweeping south and seizing Crown Point, Fort Ticonderoga, and a series of northern forts, Burgoyne’s 8,000 British and Germans (with a few hundred Canadian and Indian allies) faced off against an American army assembling around Albany.

Saratoga Campaign would Decide the War

Saratoga Campaign would Decide the War

With the fall of the northern forts in the summer, Major General Phillip Schuyler was relieved by Major General Horatio Gates, a former British officer. Although the British had momentum, they were at the end of their supply line. More importantly, British and Indian actions along the way had inflamed New Yorkers and New Englanders alike. Thousands of men had left their farms and shops to confront the threat. Gates’ army began a series of entrenchments and breastworks about thirty miles north of Albany and waited for the British onslaught. Gates had some highly experienced commanders leading the brigades assembling: Enoch Poor, Ebeneezer Learned, John Glover, John Nixon, John Patterson, and Daniel Morgan (who fought with Arnold at Quebec). Brigadier General Arnold commanded the “Left Wing” and was second in command.

Major General Phillip Schuyler

Major General Phillip Schuyler

Earlier that year, Arnold had commanded forces in Rhode Island, where he spent time at home visiting family and socializing in Boston. He was riding to Philadelphia to complain of being passed over for the rank of major general but had to detour to thwart a British raid into his native Connecticut. Arnold received a second leg wound in the action. Congress later promoted him but not with the earlier date of rank. Inflamed by the affront (more junior officers promoted over him), Arnold resigned from the army once more.

Major General Horatio Gates

Major General Horatio Gates

But the British sweep down Lake Champlain, and the fall of Ticonderoga caused General Washington to refuse his letter and order him to the Northern Department. Major General Arnold arrived in time to lead a relief column along the Mohawk River to break up the British siege of Fort Stanwix (today’s Rome, NY). Although the British and Indian allies destroyed an earlier relief column at Oriskany, Arnold’s reputation, combined with a clever ruse amplifying the size of his division, sent Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger’s forces in retreat back to Oswego.

Oriskany

OriskanySaratoga Battles

With the threat from the west gone, the Americans could focus on the juggernaut creeping south toward Albany. Two distinct major actions were fought north of Albany, sometimes called “The Battle of Saratoga.”

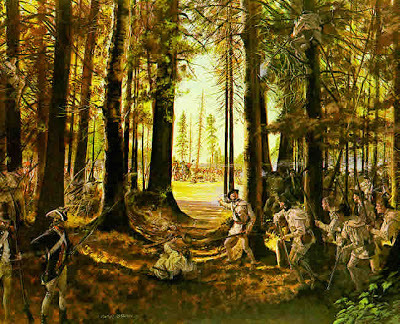

Freeman’s FarmWith Shuyler relieved, Arnold was under a general he neither liked nor respected – Horatio Gates. Arnold did not attempt to hide his feelings, and they soon became mutual. Animous among top leaders is never a good situation in command but one quite common. The first action occurred on 19 September 1777 at Freeman’s Farm, and whether because of or despite his animous, Arnold’s instincts kicked in, and he sprang into action without orders from Gates. Arnold gathered what forces he could to meet the threat to the army’s left wing. Morgan’s Rifles, plus American light infantry and militia regiments, stopped British General Simon Fraser’s elite corps.

Freeman's Farm

Freeman's Farm

But Gates was not impressed. After Freeman’s Farm, he and Arnold had more bad words, and Gates relieved him of duties for exceeding his authority and insubordination. Arnold was confined to quarters when Burgoyne launched his second assault on the Americans on 7 October. Informed of the attack, Arnold broke his confinement and spurred into action. Once again, men eagerly gathered around him. He soon led inspired regiments against the British in a brilliant counterstroke that smashed their advance and took a key redoubt manned by elite German infantry. During the furious fighting, Arnold’s horse was shot from under him. He sustained another leg injury. But his bold action set the British up for the first surrender of a British field army in decades.

Bemis Heights

Bemis Heights

Horatio Gates claimed the victory, but Arnold’s courage under fire and leadership won the day. General Washington saw him as one of his best battlefield commanders and destined for more command responsibility once he recovered from his wounds. But Arnold’s gallantry at Saratoga would be followed by more grievances, perceived and actual, and a series of events that would take him from the pinnacle as the nation’s greatest war hero to the depths of hated ignominy. A tale we shall dive into in a future post.

Arnold Monument at Saratoga

Arnold Monument at Saratoga

January 31, 2023

The Old Wagoner

In my effort to highlight the important (and not-so-important) historical personalities in my fourth Yankee Doodle Spies novel, The North Spy, I must not neglect one who lived about an hour's drive from where I am living in Virginia.

This larger-than-life figure, whose contributions are the stuff of legend, is the only senior American leader who played significant positive contributions in all theaters from Canada to the Carolinas and led troops in The Northern and Southern Departments, as well as the main Continental Army. His role merits more than one blog post, so this edition will survey his background and actions leading up to and through the events in The North Spy. His further exploits will be the subject of a future post.

Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan was born around 1736. He came from a family of Welsh settlers in Pennsylvania, but young Dan Morgan was born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, where his parents, James Morgan and Eleanor Lloyd, had resettled. He was five of seven siblings. When just a teenager, Morgan ran from his home in the Jerseys and settled in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley near Winchester, Virginia. Young Morgan spent these years cutting down trees, establishing a sawmill, and running wagons to haul goods. The latter proved quite lucrative. On the personal side, he soon garnered a reputation as a hard-drinking, quick-to-anger frontier brawler. Dan's six-foot, two-hundred-pound frame made him a powerful and muscular young man well-suited for the back-breaking work of life on the frontier. Due to his size and demeanor, Morgan seemed older than his years and was called "The Old Wagoner."

18th-century frontier wagon

18th-century frontier wagonWhen the French and Indian War erupted, his wagons rolled west with General Edward Braddock in 1755 (See Blog, Road to Destruction). This offered a chance to serve his King while making money and having some excitement. His cousin Daniel Boone was also part of the campaign, as were two of his future commanders, Colonel George Washington and Lieutenant Colonel Horatio Gates (See Blog, What Ho, Horatio).

Morgan's Cousin, Daniel Boone

Morgan's Cousin, Daniel BooneThe way to Fort Duquesne was rough, but Morgan was more than up to guiding wagons pulled by horse teams through heavily wooded mountains, streams, and rivers of northwestern Virginia (today's West Virginia)), western Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Braddock's column was annihilated at The Battle of the Monongahela, where a smaller force of French and Indians cut the redcoats to ribbons in the dense forests around what is today's Pittsburgh.

Battle of Monongahela

Battle of Monongahela"The Old Wagoner" hated the strict regimen of the British regulars, which he resisted and mocked. For their part, Morgan was the kind of rustic American colonial they loathed and put down at every opportunity.

In 1756, while Morgan was hauling supplies to Fort Chiswell, he had a run-in with a British lieutenant, who struck the "Old Wagoner" with the flat of his saber. Morgan exploded with a powerful blow to the subaltern's jaw, knocking him cold. A court-martial sentenced him to 500 lashes. He developed a hatred for the British Army. A properly used leather whip of the day could easily have a man near death or begging for it at ten well-placed stokes. He survived, and his joking about it only enhanced his tough-guy reputation, commenting that the British had miscounted and still owed him one more lash.

The lash did not deter Morgan's defiance of British authority

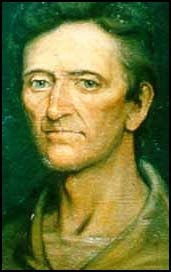

The lash did not deter Morgan's defiance of British authorityMorgan returned to Virginia and served as a rifleman in Virginia's militia assigned to protect the western settlements from the ravages of Indian raids. He led the relief column at Fort Edwards during its siege and took command of its defenses. In 1758, as Morgan was traveling home to Winchester from Fort Edward, a well-aimed ball from a musket-wielding brave near Hanging Rock passed through his cheek, shattering teeth, disfiguring his face, and contributing to an already fearsome demeanor.

Fort Edwards

Fort EdwardsDespite the wounds and struggles with the military hierarchy, Morgan was drawn to campaigning and, in 1753, fought as a ranger in Pontiac's Indian rebellion. And in 1774, Morgan picked up his musket to serve in Lord Dunmore's War between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations.

Virginia militia and Shawnee and Mingo warriors

Virginia militia and Shawnee and Mingo warriorsThe Revolutionary War commenced in April 1775, and the Continental Congress authorized the creation of a 10-company regiment of riflemen. Morgan was selected as a captain of a Virginia company. He led it to Boston and joined the main army gathered under General George Washington.

Joining Washington's Army

Joining Washington's ArmyIn September 1775, Morgan marched with Colonel Benedict Arnold on his punishing expedition to seize Canada from British control. He endured many grueling weeks in the rugged and barren Maine wilderness. On December 3, 1775, Morgan and Arnold joined an army led by General Richard Montgomery (See Blog, First to Fall) outside Quebec.

The Route through Maine

The Route through MaineThe Americans lacked artillery and supplies, so they launched a desperate attack on Governor Guy Carleton's (See Blog, The Governor General) garrison on December 31, 1775, during a blinding snowstorm. What could go wrong? Well, everything. Morgan took command of the surviving Americans after Arnold was wounded and Montgomery cut down in a torrent of grapeshot. The Americans were haggard, cold, tired, hungry, and unable to breach Carleton's defenses. Morgan surrendered.

Storming Quebec in a storm

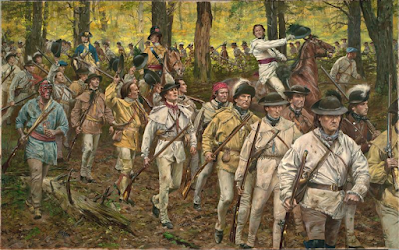

Storming Quebec in a stormMorgan was exchanged after eight months in captivity. He was soon appointed Colonel of the 11th Virginia Continental Infantry. But Washington, sensing the need for able light infantry sharpshooters, directed him to raise a battalion of riflemen. This new battalion would be made up of Virginians, Pennsylvanians, and Marylanders and be known as Morgan's Rifle Corps.

Morgan's Rifle Corps

Morgan's Rifle CorpsAlthough the Continental Army was busy watching General William Howe's forces in New York City, Congress pressured Washington to send part of his forces to reinforce the Northern Department near Albany, New York. Along with Henry Dearborn's Light Infantry and a few other regiments, Morgan joined General Horatio Gates's army and played a pivotal role in the Saratoga campaign against General John Burgoyne (See Blog, Gentleman Johnny).

General John Burgoyne

General John BurgoyneMorgan's Riflemen were used to screen and patrol in the heaviest terrain, on the left flank of Gate's army, defending in farmland and rolling hills about thirty miles north of Albany. The sharpshooters of Morgan's Rifle Corps shot down droves of British officers at the pivotal battles of Freeman's Farm and Bemis Heights and pinned down the cream of Burgoyne's Army in the wooded hills.

Morgan's Rifles holding the right line

Morgan's Rifles holding the right lineOn October 7, 1777, one rifleman, Timothy Murphy (See Blog, Patriot Sniper), fired three lead balls at General Simon Fraser (see Blog, Fighting Fraser)), with two striking and mortally wounding the best British leader on the field. Fraser's death demoralized the British, and Burgoyne later surrendered at Saratoga, New York, when Morgan's Rifles and American militia cut off his supply lines and threatened his line of retreat.

Tim Murphy credited with shooting Simon Fraser

Tim Murphy credited with shooting Simon FraserUsually reserving praise for himself and close confidants, Horatio Gates openly admired Morgan's qualities in his official report and gave him partial credit for Burgoyne's demise. Gates wanted Morgan's Rifle Corps to remain with his Department, but Morgan, who did not like the self-serving Gates, marched his Corps to join General Washington and the main Continental Army in New Jersey.

Morgan right front at Burgoyne's surrender

Morgan right front at Burgoyne's surrender

December 30, 2022

The Baroness