The Indispensable Spymaster

"There isnothing more necessary than good Intelligence to frustrate a designing Enemy,and nothing requires greater pains to obtain." George Washington

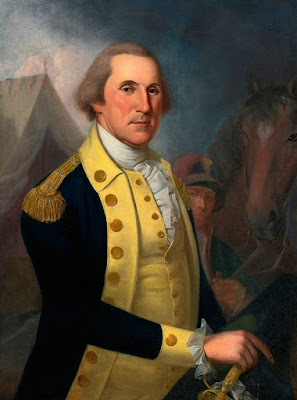

As commander in chief of the Continental Army, GeorgeWashington was much more than a general. He was the undeclared head of theUnited States with concerns beyond the usual man, equip and train mandate ofcommanding generals. He was a figurehead but also influenced the ContinentalCongress and state policies through persuasion. His concerns involved everyaspect of the aforementioned mandates, making him the Army's chief logistician,personnel director, organizer, and trainer in many ways. And he was the chiefstrategist and operational planner for all the Continental Army's departments.

The Indispensable Spymaster

The Indispensable Spymaster

It must be remembered that military staffs were not therobust teams of highly skilled planners and actions officers that developed inthe French and Prussian armies of the next century—just a few aides de camp andorderlies reviewed and prepared correspondence on a day-to-day basis. For bigdecisions, Washington consulted with Congress and senior military officers. Butthe daily management, often via "Orders of the Day" and "GeneralOrders," rested with Washington and a handful of men around him.

Planning operations

Planning operations

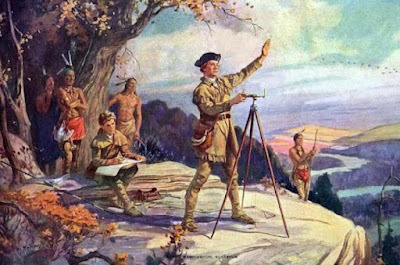

So it is no surprise that Washington added to his burden byserving as the Continental Army's spymaster. It was a job he took mostseriously. And why not? He was a trained and practiced surveyor, a professionrequiring an understanding of terrain – knowing the land, waters, fields,forests, and mountains. He traveled deep into the American frontier andunderstood the time and space considerations needed to plan venturessuccessfully. And most importantly, his career was launched by a spy mission.

Surveying - the handmaiden of intelligence

Surveying - the handmaiden of intelligence

In 1753, Virginia's Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent a youngMajor Washington to spy on the French outposts deep in the upperOhio River valley. Washington honed his recruiting skills by engaging theservices of experienced guides and interpreters, one of whom was an explorernamed Christopher Gist. In the densely forested mountains near the French FortDuquesne (today's Pittsburgh), he met a Seneca chief named Half-King, who guidedWashington to a meeting with the French.

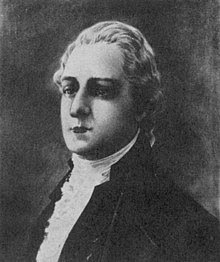

Robert Dinwiddie

Robert Dinwiddie

Washington elicited a trove of data such as fort locations,numbers of canoes and bateaux, etc. But the essential element of information,Dinwiddie's purpose for the expedition, was discovering French intentions. Thesewere to control the entire Ohio Valley and surrounding territory to maintain a monopolywith the tribes in the interior. After eighty days of slogging throughsnow-filled mountains and canoeing along icy rivers with Gist, the young spyarrived in Williamsburg and gave the governor a detailed written report.

Lieutenant Colonel Washington

Lieutenant Colonel Washington

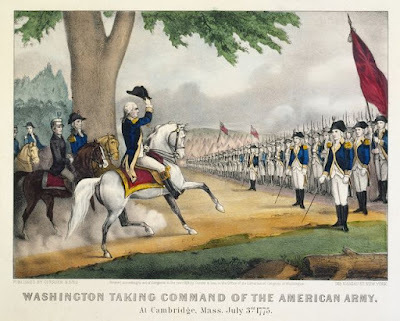

Ironically, his professional work resulted in Dinwiddiesending him back out the following year at the head of a military contingentaimed at buttressing Virginia's claim to the territory. Lieutenant Colonel Washington's second expedition was adisaster that led to the French and Indian War in America and the Seven Years' War in Europe. Indeed, the Frenchand Indian War provided Washington with the springboard to command theContinental Army in 1775.

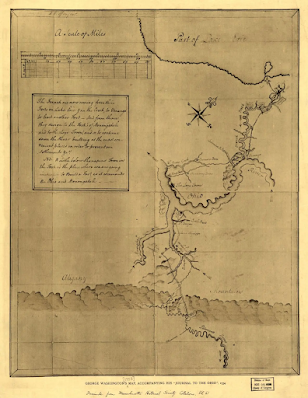

Washington's map of Ohio Valley 1754

Washington's map of Ohio Valley 1754By the time Washington assumed command at Cambridge, Massachusetts,he had the skills and experience to plan and implement intelligence activities. He spent the latter years of the war commanding the Virginia Militia Regiment, which was charged with protecting the Shenandoah Valley from French-inspired Indianincursions.

The weakness of Washington's Army for most of the war forcedhim to wage a war of so-called Fabian tactics, which relied on accurate intelligence,military security, and tactical deception to level the playing field with the British. The Boston campaign provides a helpful example.

The Continental Army outside Boston was initially weak

The Continental Army outside Boston was initially weak

On taking command, he learned the Continental Army wasdangerously low on gunpowder. Washington employed strict security to protectthe new Army's biggest secret. He took great pains to cloak this from theBritish until he had an adequate supply. He sought intelligence on the Britishactivities in Boston, but his critical knowledge requirement was theirknowledge of the gunpowder problem.

Low supplies of gunpowder threatened the Army

Low supplies of gunpowder threatened the Army

During that period, a spy was discovered at the highestlevels – Doctor Benjamin Church, Chief Surgeon of the American Army. Secretcorrespondence with the British commander, General Gage, revealed Church'sdouble game. Church claimed he was actually trying to convince the British ofthe Americans' large stocks of gunpowder. If true, this might have been anexcellent deception operation. But a military court convicted him. Was that tooa ruse? Church disappeared at sea after his conviction, but many years later,historians discovered secret British files that proved his espionage. But was itespionage or just a good double agent operation? This affair may have promptedhis obsession with enemy spies in his camp, a fixation that continuedthroughout the eight year war.

Doctor Benjamin Church

Doctor Benjamin Church

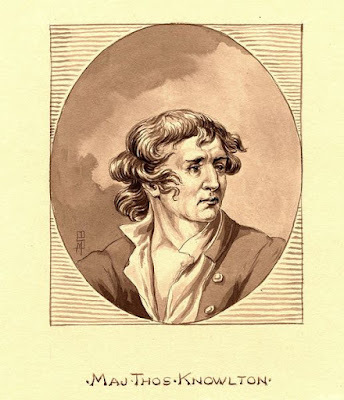

During the remainder of the war, George Washington kept atight hand on the spies and spy networks that swirled around the ContinentalArmy: Nathan Hale's strained mission, the tactical collection activities ofKnowlton's Rangers, and later the 2nd Continental Dragoons. Othersinclude Hercules Mulligan reporting from occupied New York, Lydia Darragh doing the same from Philadelphia,and of course, the Culper Ring in New York City and on Long Island. And therewere many other spies and networks that still go undiscovered.

Counterespionage was another area of Washington's personal attention. He was greatly vexed by Loyalists spying for the British such as New Jersey'sJames Moody. The Sergeant Hickey Affair resulted in the breaking up of a ringand a potential assassination plot. The most notorious espionage challenge wasposed by British Major John Andre's recruiting of arguably America's greatestwar hero- Major General Benedict Arnold. Washington was there when Arnold wasuncovered and personally directed the countermeasures, which included a parleyto exchange Andre for Arnold, dispatching an agent, a Virginia Sergeant namedJohn Champe, to kidnap the treasonous general, and appointing Andre's court martialand approving his death sentence.

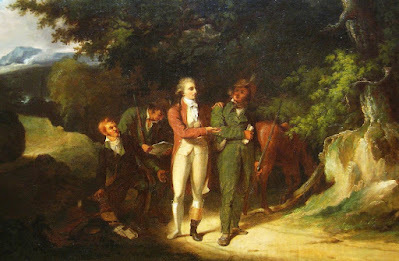

The capture of Major Andre

The capture of Major Andre

Washington employed deception and military (or operations)security throughout the war. He had to deceive the British about his Army'sstrength (or lack of it) and its intentions. There were many successes andfailures as both sides engaged in deception and counter-deception. The stakeswere high – the war's outcome could turn on their successful implementation.

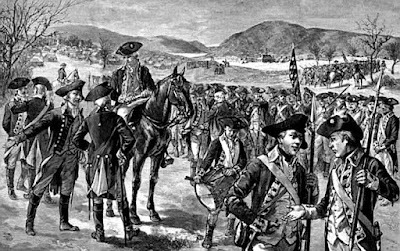

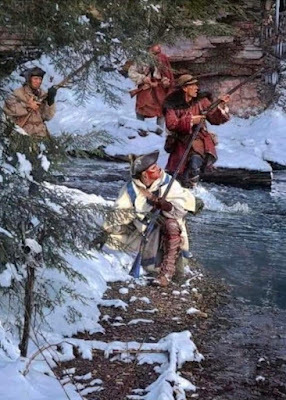

Military patrol in winter

Military patrol in winter

The most celebrated of these activities was Washington'sleveraging his well-known and long-standing desire (some might say obsession)to capture New York City. In the summer of 1783, Washington finally agreed toFrench General Rochambeau's plan to join a French fleet on its way to theChesapeake Bay and attack General Charles Cornwallis's Army on Virginia'sYorktown peninsula.

General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau

General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau For it to work, the British needed to be dissuaded from sending aid to Yorktown. He orchestrated a series of intelligence measures toplant the idea of an imminent Franco-American attack on the New York garrison. Feints by bodies of troops, deliberately lost dispatches, and the whispers of spiesconvinced British General Henry Clinton long enough to delay sendingreinforcements to beleaguered Cornwallis in Yorktown.

Spy at work

Spy at work

Even as the French and Americans marched south, their routewas designed to appear like an envelopment of the city until the very lastminute. When Clinton realized he had been humbugged, it was too late to help Cornwallis. By the end of October, the British had surrendered inYorktown. Clinton's military options were dwindling, and the British governmentfell, bringing in an administration more sympathetic to negotiations.

Washington's deception steals a march on Yorktown

Washington's deception steals a march on Yorktown

The great spymaster succeeded in leveraging an early form ofgray zone warfare. Most of these activities were kept secret long after the war,and very few official records were maintained – for obvious reasons. In anation of divided loyalties, the lives of spies are always in peril. The 18th-century zeitgeist that emphasized "honor" held spies in great disdain. YetWashington occasionally mused about those who risked lives and reputations forlittle reward or acclaim. They could not receive pensions or fame. The case ofNathan Hale is a possible exception, and that was for propaganda purposes.

Execution of Nathan Hale

Execution of Nathan Hale

The shadow war waged during the American Revolution was critical to its success. George Washington realized that. It is said he visited random citizensfor some quiet conversation during his post-war travels around the countrywhile President. Ultimately, all he could reward them with was his personalthanks. For the shadow warriors who risked life and honor, a tip of the hatfrom the most extraordinary man of the century was enough.

The Indispensable Man met many of his spies

The Indispensable Man met many of his spies