S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 6

December 30, 2021

Hart of the Rebellion

The role of women in the American Revolution is understated and underappreciated. Patriot women were there - whether it was to provide moral and physical support, maintain the family farm or business, spying, or actual fighting. They wove desperately needed clothing for the half-naked American soldiers. They provided foodstuffs to starving columns that passed through towns and farms. And during an eight-year struggle, patriotic mothers sent many a young man or boy to the ranks. In addition to yearning and fighting for liberty, every American soldier yearned to return to their home, family, and wife. One could say these women were the heart of the rebellion.

The distaff side was critical to the war effort.

The distaff side was critical to the war effort.

Ann Hart is one such woman. Born Ann Morgan in 1735, the exact date is unknown. Nor is the exact location, although it is believed somewhere in Pennsylvania or North Carolina.

Ann Morgan Hart

Ann Morgan Hart

Names were tricky back then, and the use of diminutives was widespread. Ann Hart was no exception, sporting the handle "Nancy," a common nickname for Ann at the time. According to accounts by contemporaries, Nancy was an imposing figure over six feet tall, well limbed, and red-headed. She was known for her fearlessness; the local Cherokees even called her Wahatche (war woman).

The Cherokee called her War Woman

The Cherokee called her War Woman

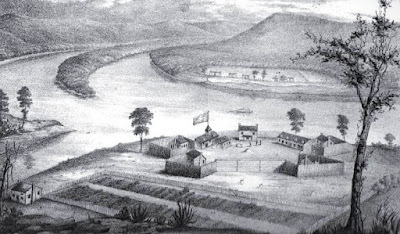

By the run-up to the War for Independence, Ann Morgan had married Benjamin Hart, and the couple settled along the Broad River in Wilkes County, Georgia, where land was fertile, cheap, and available. The year was 1771. Ann was relatively old when they married – thirty-six. Despite that, she gave birth to two daughters and six sons.

The cabin on the Broad River

The cabin on the Broad River

Nancy was a resourceful backcountry woman

Nancy was a resourceful backcountry womanAs rumor and legend will bump up against known facts, I should say Ann is said to be a relative of famed explorer Daniel Boone. And she was a cousin to Daniel Morgan, famed leader of the corps of Virginia and Pennsylvania riflemen and victor of the Battle of the Cowpens (1781).

Colonel Dan Morgan

Colonel Dan Morgan

After they moved to Georgia, Benjamin joined a Georgian militia regiment. Nancy would also become a staunch patriot and wage her own war against Georgia Loyalists.

Benjamin joined the Georgia militia

Benjamin joined the Georgia militia

Nancy was feisty and quick-tempered, according to accounts. And she ran the Hart household with an iron will and an iron fist. So, when Benjamin Hart went off to follow drum, Nancy was the perfect woman to "hold the fort." Ironically, the drum soon would follow her.

The British retook the breakaway colony of Georgia in 1779 as the launching pad of their "Southern Strategy." British occupation did not always mean British control, especially in the northeast backcountry of Georgia, where locals had been squaring off with the Cherokee for years. The American struggle for independence was also a civil war, and unlike the 18th-century wars in Europe, civilians played a role throughout.

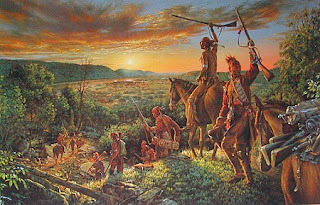

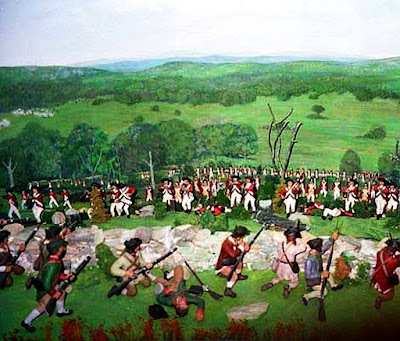

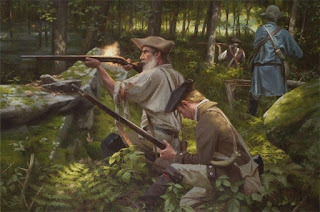

Battle of Kettle Creek by Jeff Trexler

Battle of Kettle Creek by Jeff TrexlerAccording to reports from both first and second sources, Nancy was variously a spy against the British forces in the area, a sniper of the same (she was reputed to be a crack shot), and an occasional combatant. Because of her size, it would have been easy for Nancy to dress in men's clothing and slip into British camps, as is alleged. Pretending to be crazy, she would observe activities and listen to conversations before slipping away and reporting back to local patriot militia leaders.

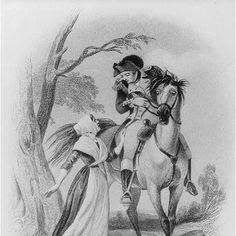

Spying on British

Spying on British

Also reputed to be a sniper, she may have taken long-distance shots at Loyalist and British patrols, couriers, and convoys trying to cross the Broad River. The war in the south had turned vicious, and sniping and ambush so frowned on in 18th-century warfare became common in the Carolinas and Georgia.

Lady sniper

Lady sniper

The British and their supporters must have suspected the strange woman because they took pains to keep their eyes on her activities, often coming by the farm to get food or check up on things. In one incident, Nancy was making soap in their cabin when one of her daughters discovered a Loyalist spying on them through a crack in the wall. When she told Nancy, the fiery redhead threw a ladle of the boiling lye through the gap, burning his eyes. As he howled in pain, the angry farm woman raced out, overpowered him, and tied him up. She eventually turned him over to the local patriot militia.

An account has Nancy carrying grain to the local mill when a gang of cowboys (Loyalist raiders) pulled her from the saddle and tossed her to the earth. As they made off with her horse, Nancy dusted off the dirt and carried her heavy grain bag to the mill on foot.

Cowboys terrorized patriot homesteads

Cowboys terrorized patriot homesteads

Some accounts put our southern hellfire at the 1779 Battle of Kettle Creek, but that is pure speculation. But the most famous of her exploits seems right on target. A half-dozen Loyalist militiamen showed up at her farm, stopping for food while pursuing a rebel. They insisted Nancy prepare a turkey. Since they were armed and ready to mete out punishment on a patriot wife, she had no choice but to submit to their demand.

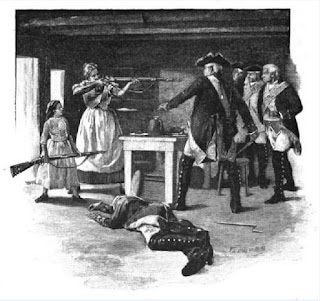

But the Loyalists made one big mistake. They neatly stacked their muskets near the door when they entered the cabin to sit at the dinner table. Nancy went to work with the table set and the food going down in mouthfuls. She slipped some of the muskets through a hole in the cabin wall. Nancy kept the food and drink coming, and once the men were sufficiently lubricated, she seized one of the muskets she left in the cabin and leveled the barrel on her visitors.

Turning muskets on the Loyalists

Turning muskets on the Loyalists

Glaring at them with a Brown Bess at full cock, she ordered them not to move. Refusing to be taken by a woman (and under the influence), one Loyalist made a move on her. That's all it took. Nancy squeezed the trigger, and the hammer slammed into the pan, striking the powder and sending a plug of lead into his chest. Another Loyalist lunged at her, but Nancy had grabbed another musket and blasted him. She had little trouble convincing the remainder to sit quietly at the table until help arrived. When her neighbors and husband appeared, they decided to shoot the prisoners. But Nancy refused. Instead, she demanded they be hung from a nearby tree.

Nancy demanded the Loyalists be hanged

Nancy demanded the Loyalists be hanged

This tale was corroborated in the early 19th century uncovered the remains of a half dozen men were dug up at the farm – four with broken necks.

Like so many Americans, the post-war period was one of transition and movement. In the late 1790s, Nancy and her husband moved the family to Brunswick, Georgia. When Benjamin died there in 1800, Nancy decided to return to her former home on the Broad River. Unfortunately, their cabin had been washed away by a flood.

With the farmhouse gone, she moved in with one of her sons, John Hart, and his family along the Oconee River in Clarke County near Athens, Georgia. In 1803, Nancy moved with John and his family to Henderson County, Kentucky, to live near relatives. The fighting lady spent the remainder of her life in Henderson. When she died in 1830 at 93, they buried Nancy in the family plot.

Nancy's gravestone

Nancy's gravestone

Our "Hart of the South" was commemorated by the state she fought so hard to help liberate. A Georgia highway, city, lake, and county are named after her. And the Daughters of the American Revolution recognized this fighting lady by erecting a replica of her cabin on the Broad River using some of the original stones.

Nancy Hart Monument, Hart Co.,GA

Nancy Hart Monument, Hart Co.,GA

November 30, 2021

The Fighting Fraser

This is the second installment profiling one of the characters in book four of the Yankee Doodle Spies series, The North Spy. due for release next year. As my last profile was a Scotsman who fought for America, it was only fitting that I follow with a Scotsman who fought for England. Not just any Scotsman, but a son of the famed Fraser clan of Highland warriors.

Proud Lineage

Simon Fraser was born into a proud Scots highland lineage at Balnain, Scotland on 26 May 1729. His family and clan were warriors of the first order and as such, many went down at the fateful Battle of Culloden in 1745. Those who did not fall saw their lands and patrimony stripped and were driven into exile.

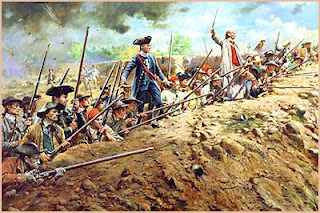

Culloden smashed the Clans - but not the Highland spirit

Culloden smashed the Clans - but not the Highland spiritDutch Service

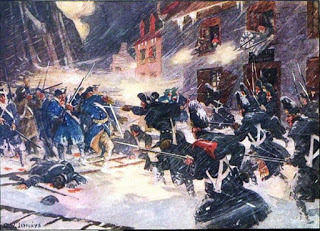

The Scots, like their cousins across the Irish Sea, tend to fight for the English when not actually fighting against them. This the young Fraser did, but beginning with a stint in one of the Scots Brigades in the hire of the Netherlands - the 4th Brigade to be precise. In the waning years of the War of Austrian Succession young Simon fought at the 1747 siege of Bergen-op-Zoom. The attacking French swarmed over the defense works and streamed into the town where savage fighting took place. In the attack and counterattack, Fraser was wounded.

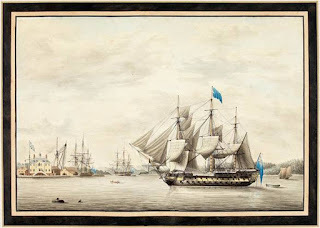

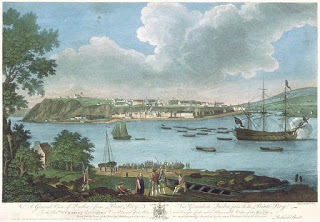

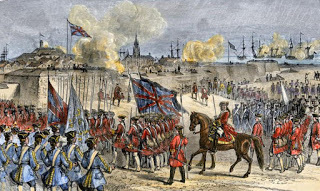

Seige of Bergen-Op-Zoom

Seige of Bergen-Op-ZoomRoyal American

With the end of the war, the Dutch Brigade was reduced to one battalion and Fraser had to seek his laurels elsewhere. The outbreak of the Seven Years war provided a golden opportunity for an eager and now blooded young highlander. In 1756, Fraser joined the British Army’s 62nd Royal American Regiment of Foot. Renumbered as the 60th the following year, it later gained fame as The King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

Back to the Clan

Fraser did not remain with the 60th very long. In January 1757, he took a commission in a newly formed regiment of highlanders, the 63rd Highlander Regiment of Foot. The regiment was commanded by Simon’s cousin, Lord Lovat, also named Simon Fraser. The unit was called Fraser’s Regiment and its ranks were flush with Frasers. This was the likely draw to the unit – fighting with and for kin.

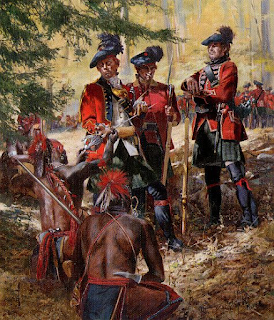

Fighting French & Indians

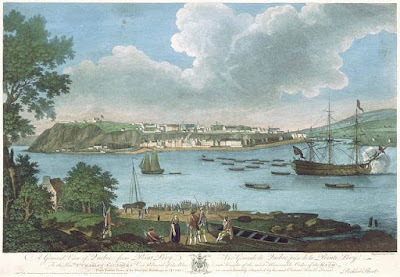

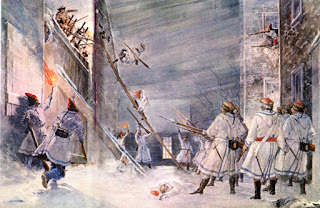

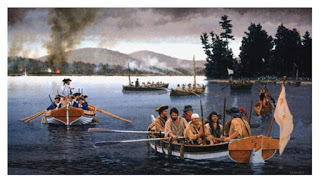

Fraser sailed to America to fight the French, serving at the siege of Louisbourg, the taking of which gave Britain control of the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River. He served under British General James Wolfe during the 1759 attack on Quebec, the decisive battle of the war in America. The 78th climbed the Heights of Abraham with Wolfe and Lieutenant Fraser was wounded in the hard-fought action while Wolfe was mortally wounded in his great victory.

Scaling the Heights of Abraham

Scaling the Heights of AbrahamFraser’s time with the 60th and his service in America with the 78th opened his eyes to the different style of fighting in a woodland wilderness – the need for disciplined troops who could fight outside of massed formations and rely on the terrain and marksmanship to bring down an enemy as the Indian allies of the French could. Following Quebec, Fraser’s unit had garrison duty in the city and spent some time in New York. But the French and Indian part of the war was just about over.

Fraser's Highlanders mingle with Iroquois Braves

Fraser's Highlanders mingle with Iroquois BravesSeven Year Itch

By 1760 Fraser was back in Europe – the seven years of the Seven Years War was not up. This involved another transfer – this time to the 24th Regiment of Foot, which was sent to Germany to serve in Lord Granby’s Corps. In two years, the 24th fought in over a half-dozen sieges and pitched battles against the French. He was cited for heroism at the battle of Wezen in November 1761. Fraser led a hand-picked company of fifty men in an attack that drove off some 400 French troops. He was promoted to major during this time. He also learned a lesson in what hand-picked and specially trained men could do against greater odds.

British infantry in the Seven Years War

British infantry in the Seven Years WarPost-Treaty of Paris

After the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763, Fraser continued with the army – serving in Germany, Ireland, and Gibraltar. From 1763 to 1769, Simon Fraser and the 24th were stationed at Gibraltar. He performed quite well and was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the 24th in 1768. Fraser put the regiment through specialized training, making it one of the first British regiments to specialize in light infantry tactics.

Gibraltar

GibraltarIt was also on Gibraltar that he met Margarita Hendrika Beck Grant, widow of Major Alexander Grant, a fellow Scot. After a period of exchanging letters, they were married. Shortly thereafter, they moved to Ireland when the 24th was transferred there. The couple had no children.

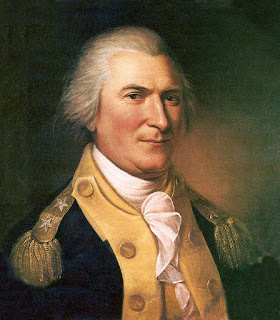

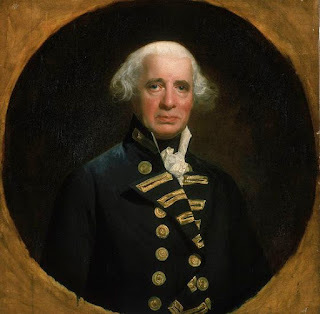

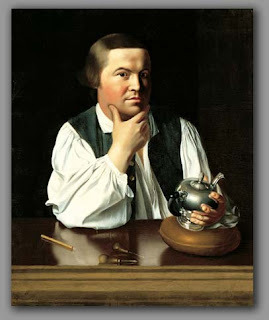

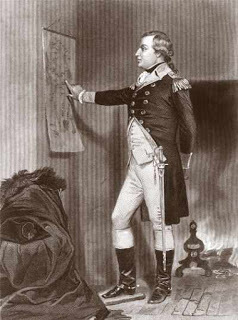

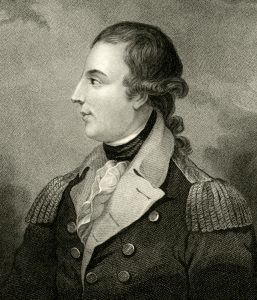

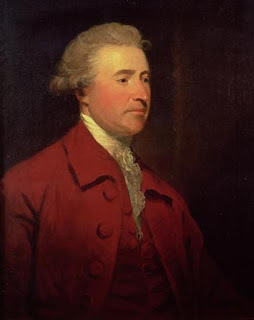

Brigadier General Simon Fraser

War Clouds in AmericaFraser had watched the North American colonies move into rebellion and war. The rebels drove a British Army from Boston in 1775 and invaded Canada. More troops were needed to put down the rebellion. More importantly, Britain needed experienced officers. So it was as commander of a brigade of five battalions Fraser sailed from Ireland and returned to North America in April 1776. He was sent to provide support to the beleaguered Governor-General Guy Carleton who was besieged in Quebec by the American rebels. Carleton had held off the invading army against all odds during a brutal winter campaign. Fraser’s arrival enabled him to go on the offensive.

Governor-General Guy CarletonIn the Vanguard

Governor-General Guy CarletonIn the VanguardFraser wasted no time – he smashed American General William Thompson’s division at Trois Rivieres in June. Named brevet Brigadier General by Carleton, Fraser took command of the Advance Guard of the British counteroffensive into New York’s Champlain Valley. Although Carleton’s campaign proved successful, the stubborn American defense, led by Brigadier General Benedict Arnold took him off his timetable by fighting him at Valcour Island. The battle was won but winter was coming.

Valcour IslandAn Unsavory Pause

Valcour IslandAn Unsavory PauseRather than risk the final plunge to Albany with winter approaching, Carleton withdrew to the northern extreme of Lake Champlain, planning to strike out again the following year. Fraser, like many other officers, was not happy with the cautious approach but things would have to wait for a new season – and a new commander. Fraser used the winter quarters to train his troops in light infantry tactics and prepare them for operations in the rough American wilderness.

The upper end of Lake Champlain

The upper end of Lake ChamplainNew Boss, New Plan

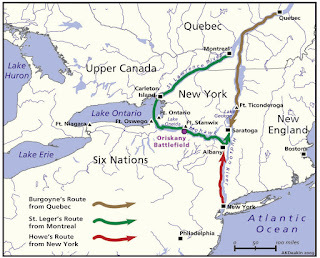

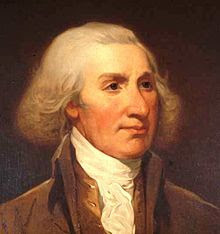

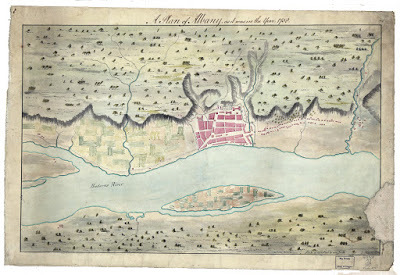

In the spring of 1777, Major General John Burgoyne returned from London with 8,000 British and German reinforcements and a new plan for invasion. The plan called for three separate thrusts from the west, north, and south to converge on Albany. And the plan called for Burgoyne, not Carleton to lead the main thrust from Canada.

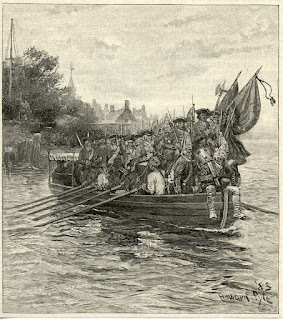

General John BurgoyneAdvance Guard Again

General John BurgoyneAdvance Guard AgainBrigadier General Fraser was put in command of Burgoyne’s advance guard, some 1,200 troops now trained as light infantry. The army launched itself from the mouth of the Richelieu River into Lake Champlain in an armada of Bateaux and canoes. Moving quickly, Fraser’s forces screened the advance on the impregnable Fort Ticonderoga and seized it in a coup de main as the American defenders retreated in the dark of night. Fraser himself led the troops and hoisted up a British flag.

Ticonderoga

TiconderogaA Hot Pursuit

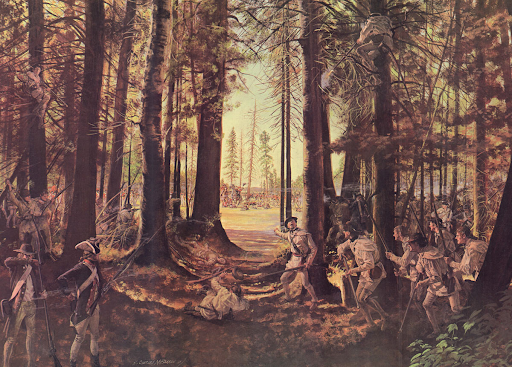

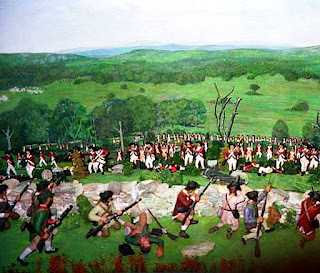

Fraser then launched his advance guard in hot pursuit as the Americans chose to retreat through the dense forests to the south and east rather than take the waterways that led south. The British vanguard stayed on their trail and finally pinned down the American rear guard under Colonel Seth Warner, also an experienced woodland fighter, near Hubbardton. In a back and forth slog the larger American force actually began to have the better of him, but a column of Germans under General von Riedesel helped turn the battle.

The American militia acquitted itself well against the professionals at HubbardtonSupply Chain Blues

The American militia acquitted itself well against the professionals at HubbardtonSupply Chain BluesThe rest of Burgoyne’s army was now moving south again with Fraser’s brigade at the lead. Albany would fall with just a final drive. But Burgoyne now faced a supply chain problem as he was far removed from his base and shortages began to crop up. In addition, Fraser’s scouts (including some Canadians and Iroquois) were reporting on a large concentration of Americans just north of Albany under the command of a former British officer, General Horatio Gates.

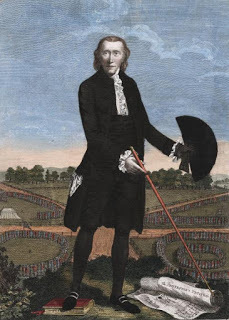

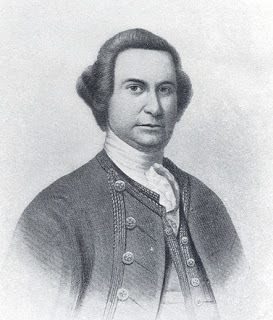

Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates

Burgoyne began to lose his nerve. The other two thrusts had failed and he was on his own. Rather than risk an all-out attack, he launched a reconnaissance in force with Fraser’s commanding the right-wing – through heavily wooded and rugged terrain.

Freeman's Farm

Freeman's FarmClash of Titans

There, Fraser’s elite force ran head-on against their American counterpart, the corps of Virginia and Pennsylvania riflemen under Colonel Daniel Morgan. Morgan’s riflemen sported long rifles with grooved barrels enabling accurate fire well over one hundred yards. Fraser's brigade included the tip marksmen in the British Army. The lead flew as the best of both armies peppered each other and finally, Morgan’s force was driven back, leaving an opportunity to exploit the situation and fight their way around the American flank.

Dan Morgan

Dan Morgan

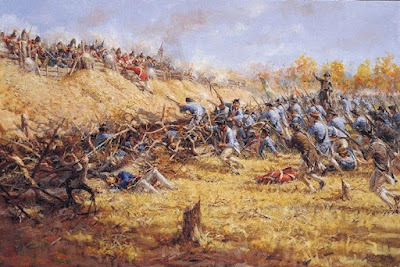

But Burgoyne did not approve and instead withdrew his army back to its camp to figure out the supply situation. That situation only deteriorated and with autumn getting longer in the tooth, Burgoyne was forced into a desperate situation. This time, it was a probing attack. The idea was to feel out the enemy and exploit any weaknesses. He launched his probe on 7 October in what would become the Battle of Bemis Heights.

Bemis HeightsFrenzied Fighting

Bemis HeightsFrenzied FightingFraser was once again in the thick of things with his brigade. But the Americans did not seem to bend and in fact, began to launch savage counterattacks all along the front, led by General Benedict Arnold. British forces stood and then withdrew under the pressure of American volleys and bayonet charges. Fraser time and again rallied units and formed the line. Mounted, despite the sheets of lead humming everywhere, he waved his saber.

Fraser struck on the third shot

Fraser struck on the third shotIn the Crosshairs

From somewhere far off, an American rifleman cocked his hammer and gazed down the long barrel of his rifle, leveling it on a red-coated figure on a horse. Legend has it the sniper was Private Tim Murphy who allegedly said, “That is a gallant officer, but he must die.” He squeezed the trigger, the hammer cracked down, ignited the firing pan, and launched a ball that just missed Fraser. A second shot struck his saddle but Fraser ignored the fire. Ignoring pleas from his aides, he continued until a third shot struck home with a ball into his belly – a mortal wound.

American Riflemen moving into firing positions

American Riflemen moving into firing positionsA Blow to an Army

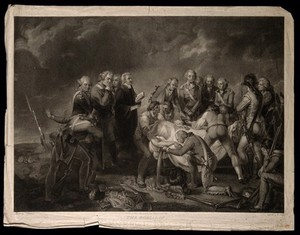

The fall of Fraser sent a wave of shock through the whole British Army – especially Burgoyne, who soon ordered his battered forces back to their encampment to the north near a place called Saratoga.

Baroness Fredericka von Riedesel

Baroness Fredericka von Riedesel

Desperate hands wrangled the dying general to the rear where he was nursed by the wife of von Riedesel, Baroness Fredericka, who had accompanied her husband on the wilderness campaign.

Fraser mourned on the battlefield

Fraser mourned on the battlefieldThe brave highlander died the following day and was buried at the Great Redoubt in a somber ceremony held under the guns and muskets of the encircling rebel army. A stray round from the American artillery nearly disrupted the event. On learning of it, Horatio Gates ordered a gun salute instead. Burgoyne would soon surrender his army, ending the campaign and helping push the indecisive King of France into the arms of the Americans.

The fighting Scot's exact resting place at the Great Redoubt is unknown

The fighting Scot's exact resting place at the Great Redoubt is unknownDeath's Legacy

Fraser’s life of action and service ended in a way any warrior would have chosen. But Britain lost more than a warrior. It lost one of its best generals and one who thoroughly understood the type of fighting, and the type of fighting man, it would take to win the war. Had he not fallen on that October day, he might have emerged as the leader who could have subdued the colonies for the Crown that subdued his own highland clans. Yet, ironically, the gallant Scot who fought for England, Holland, and German Allies never fought for Scotland - and is most remembered in America.

October 30, 2021

Frustrated Founder

Many leaders in the Continental Army had experience in the British Army and some of them proved quite controversial. Foremost of these was Charles Lee (General Washington’s 2nd in command who allowed himself to be captured by the British and was relieved at the Battle of Monmouth. (see blog post A General Disaster). Another was General Horatio Gates, who was victorious at Saratoga but went down in ignominy at the Battle of Camden. And our profiles of Richard Montgomery (see blog post, First to Fall) and Hugh Mercer (see blog post, Surgeon General from Scotland) demonstrate these men had no lack of courage under fire – giving the last full measure.

General Charles Lee - one of many former British officers to serve in the Continental Army

General Charles Lee - one of many former British officers to serve in the Continental Army

But this edition highlights a man whose legacy of service to his new nation is complex and, in some ways, tragic. Arthur St. Clair was a man of intelligence and industry whose uneven military talents cloak a career of dedication, patriotism, and no small amount of frustration.

Born in Truro, Scotland in 1736 to a family of some means, St. Clair attended the University of Edinburgh where he studied medicine. In 1757, St. Clair changed his career path by purchasing a commission as ensign in the 60th Foot (Royal American Regiment) and came to America in 1757 to fight in the French and Indian War.

Private - 60th Regiment of Foot

Private - 60th Regiment of Foot

Ensign St. Clair served under famed General Jeffrey Amherst where he helped in the capture of the massive French fortress at Louisburg in July 1758. The following spring, he was promoted to lieutenant and served under General James Wolfe at Quebec and the fighting on the Plains of Abraham, the decisive battle of the war. Lieutenant St. Clair was mentioned in the dispatches for his heroism there when he seized the regimental colors from a fallen soldier and carried them to victory. No piker in the courage department.

Fall of Louisburg

Fall of Louisburg

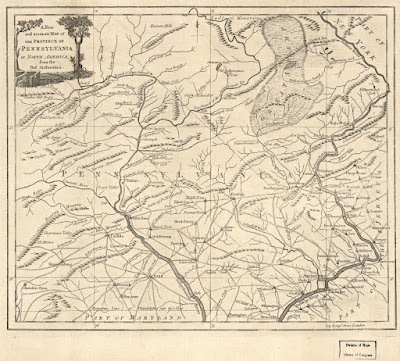

His regiment was later stationed in Boston, where Cupid’s arrow struck deeply. Our lovesick war hero married Phoebe Bayard (of the prominent Bowdoin family) in May 1760. Now ensconced in marriage into a prominent clan, the life of a British officer held less promise. So he resigned his commission in 1762 and moved to Pennsylvania to make his fortune as a surveyor. Two years later he settled permanently in Ligonier Valley in the colony’s western frontier, where land was cheap and easy to acquire. He eventually became the largest landholder and one of the most prominent men in the western part of the colony.

18th Century Pennsylvania

As was typical of prominent men of the time, he began to amass quite a resume of public service to include: surveyor of the district of Cumberland, justice of the court of quarter sessions and of common pleas, member of the proprietary council, recorder, clerk of the orphans’ court, and chief clerk of the courts of Bedford County, which then included the later-day counties of Fayette, Westmoreland, Washington, Greene and parts of Beaver, Allegheny, Indiana, and Armstrong counties. For quite a while, he was the law in a land that was essentially the wild west, overrun with hunters, Indian traders, backcountry settlers, transients, and unsavory characters of all types. He was particularly noteworthy for his fair dealings with the local Indians.

St. Clair was caught up in the territorial disputes between Pennsylvania and Virginia, which claimed a large piece of the western regions of the colony. When Virginian John Connolly seized the area near today’s Pittsburg for Virginia and tried to subvert Pennsylvania’s settlers, St. Clair had him arrested. Virginia’s governor had Pennsylvanians arrested and complained to Governor Penn about St. Clair. The governor backed his magistrate but the border dispute between the two colonies/states was not settled until Congress intervened years later.

As with so many prominent colonial leaders, Arthur St. Clair took a key role in the local militia. In January 1776, he was commissioned a colonel of a regiment, which he raised during the winter and force-marched north to join the invasion of Canada arriving in Quebec on 11 April. But the campaign was already lost with the defeat and death of Montgomery storming Quebec and the American defeat at Chambly. All he could do was help General John Sullivan’s retreat.

The campaign in Canada was lost by the timeSt. Clair arrived at Quebec

The campaign in Canada was lost by the timeSt. Clair arrived at Quebec

But his knowledge of the area from the last war, and his military experience helped save a large portion of the routed army. St. Clair himself was injured and barely made it back after being cut off by advancing British forces.

Major General Arthur St. Clair

Major General Arthur St. Clair

He was recognized for his service and talents by a promotion to Brigadier General in August and was ordered to join General George Washington’s army in New Jersey where he took command of a couple of New Jersey militia regiments. The campaign also turned into a rout and Washington’s forces melted away as they retreated from Brunswick to make a narrow escape across the Delaware River.

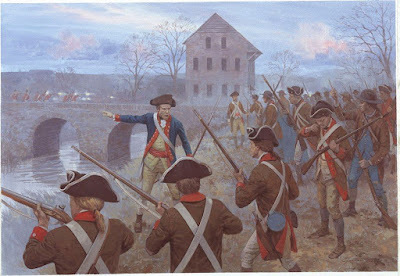

St. Clair went to work recruiting men for the beleaguered Continental Army and was rewarded with a brigade command, which he led ably at the key American victories at Trenton, Assenpink Creek, and Princeton in the whirlwind counterstrike of December 1776 – January 1777. Some accounts report that St. Clair conceived the brilliant night move from the Assenpink to cut off the British and threaten Princeton. Most of the other commanders recommended a retreat. But Washington took St. Clair’s advice, which led to the victory over the British at Princeton and possibly saved the rebellion from collapse. This explains Washington’s support of St. Clair during later times of controversy.

Assenpink Creek

Assenpink Creek

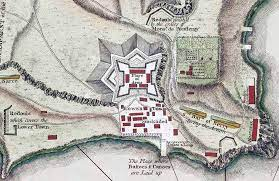

By the spring of 1777, things were heating up once more in the great north. A major army under General John Burgoyne (see blog post, Gentleman Johnny) was marshaling north of Lake Champlain. Continental Congress President John Hancock ordered the newly minted Major General Arthur St, Clair to take command of the strategically placed but undermanned fortress – Fort Ticonderoga. But when St. Clair arrived in early June he found a fort in crisis. Stradling the southern bank of Lake Champlain, the fort was the first objective in a British invasion aimed at taking Albany and dividing the colonies. All had high hopes the fort would be the breakwater to stymie Burgoyne’s red wave.

General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne

But as the Americans should have learned from the debacle at Fort Washington the previous year, a powerful fort that is undermanned is a liability, not an asset. And Ticonderoga was undermanned with men who were ill-fed and ill-equipped. Powder and provisions of all kinds were lacking. Scarcely 2,500 men in a fort requiring 10,000 for a proper garrison. Burgoyne had over 8,000 British and German troops and plenty of artillery and supplies.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort TiconderogaOutflanked and Outgunned

The British soon descended on the area and quickly took control of Mount Defiance, where they hauled up a battery that commanded Ticonderoga. Plunging fire would soon shatter the defenses and blast the defenders with impunity. At a council of war, St. Clair decided to evacuate the post and save the army for another day. A wise but controversial decision.

British guns on Mount Defiance would dominate the areaaround Ticonderoga

British guns on Mount Defiance would dominate the areaaround TiconderogaFlight by Night

The night withdrawal in the face of an overwhelming enemy was a huge risk. St. Clair pulled it off, but not without a major snafu when French-born General Fermoy’s unexplained fire at his quarters alerted the British. With redcoats and Germans hot on their heels, the beleaguered Americans fled through the woods; a water route was eschewed except for the wounded. St. Clair hoped not only to save his army but to lure the British away from their axis of advance, delay their advance, and stretch their supply lines.

Retreat, Divide and Conquer?

He split his forces and the rear guard delayed the British pursuers, who were after them like hounds on a rabbit. St. Clair hoped to divide the British and siphon them into the deep northern woods rather than sail effortlessly down Lake George. They were barely ahead of the enemy. General Simon Fraser’s advance guard – the elite of the British army, collided with some of St. Clair’s forces at Hubbardton. It was a hard-won victory for Fraser. Another British force – Germans actually – went down to defeat when they tried to alleviate a worsening supply situation by taking livestock at Bennington in today's Vermont.

Hubbardton - a defeat, but also a diversion

Hubbardton - a defeat, but also a diversion

Regardless of the wisdom of St. Clair’s successful retrograde: he diverted and slowed the British,

divided their army, extended their supply lines, and kept a valuable field force from marching into captivity, St. Clair was decried from all quarters, but most especially by those who wanted General Horatio Gates to replace Washington as commander in chief. Although the precious 2,500 men he saved provided the core of the forces that General Horatio Gates had on hand to defeat the British as Saratoga, St. Clair was relieved of all command.

General Horatio Gates

General Horatio Gates

Yet General Washington continued to support him and recalled him to the main army, where he stayed at the commander in chief’s side and served as an aide at the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777. At St. Clair's request, a court-martial was held in 1778. St. Clair was acquitted, “with the highest honor, of the charges against him.” But any hope of battlefield command was over.

He continued serving, however, and was at Washington’s side when General Cornwallis’s army grounded muskets at Yorktown in October 1781. The war in the south was still a thing, and St. Clair was given the mission of marching a column of troops into the Carolinas to reinforce General Nathanael Greene, who was trying to mop up British garrisons from Ninety-Six to Charleston and Savannah. St. Clair's Pennsylvania street cred came in handy when a serious mutiny took place among the Pennsylvania Line regiments in 1783. St. Clair was called upon to appeal to his fellow Pennsylvanians, and he helped to calm the mutineers who gave up on plans for an armed march on Congress.

Yorktown surrender

Yorktown surrender

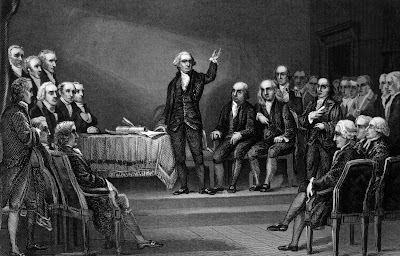

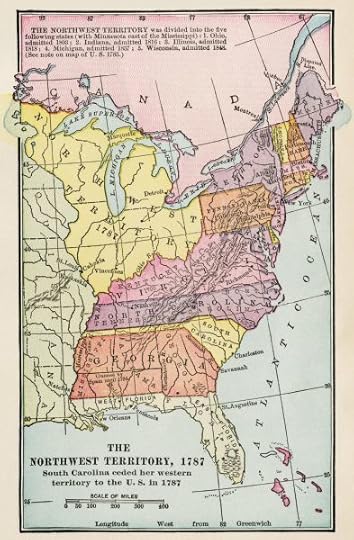

St. Clair returned to Pennsylvania and began a career of distinguished political service to the new nation. He joined the Pennsylvania Council of Censors in 1783. Later, St. Clair was elected a delegate to the Confederation Congress. During his term of office from November 1785 through November 1787, he helped instantiate the new national government. It was a time of firsts and a time of troubles. In February 1787 the members met and elected St. Clair President of the Confederation Congress (essentially leader of the national the Federal level). A lot crossed his plate during his one-year term.

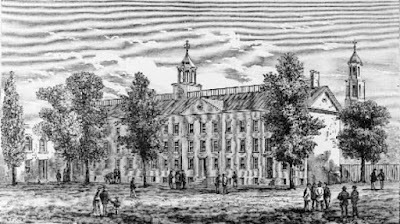

Confederaton Congress

Confederaton Congress

Shays's Rebellion broke out in 1787 over tax disputes. Disgruntled farmers, mostly war veterans marched against their state government. Despite the disruptions caused by the political crisis over Shays's rebellion, Congress managed to pass a seminal piece of legislation during his presidency – the Northwest Ordinance. This would set the template for western expansion and governance and admission of new lands into the United States. And most importantly during St. Clair's presidency, the Philadelphia Convention was drafting a new United States Constitution, which would abolish the old Confederation Congress for a more powerful federal system made up of three branches.

Shays's Rebellion

Shays's Rebellion

With the formation of the new Northwest Territory, congress named Arthur St. Clair the first governor. The Northwest Territory comprised what is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota. Making his seat of government the settlement he named “Cincinnati,” he set to work. His achievements were noteworthy in helping settle and tame the land, as well as preparing it for eventual integration into the United States. As a former magistrate, he gave the territory its first body of laws, called Maxwell’s Code. He invested funds, often personal, in helping clear land for settlement.

St. Clair’s western accomplishments were not without controversy. He began the construction of forts to protect the settlers and fend off the tribes. He negotiated the treaty of Fort Harmar – pushing the Indians from their tribal land. Rather than settling the Indian claims, the treaty provoked them into outright conflict.

Fort Harmar

Fort Harmar

The tribes took up the tomahawk and went on the warpath - sending panic among the western settlers. Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket led the coalition aided by former British Loyalists Alexander McKee and Simon Girty. The tribes defeated a 1,500-strong militia force under General Josiah Harmar in October 1790.

Chief Blue Jacket

Chief Blue Jacket

The following spring, St, Clair was promoted to major general of the army of the United States and led the response himself. Once more in uniform, he took to the field in October 1791 at the head of two Regular Army regiments and militia – a column of 1,400 men who marched deep into the Ohio wilderness to the headwaters of the Wabash River. Meanwhile, thousands of Miami, Delaware, and Shawnee braves were gathered in the dense forests just waiting for a chance to wreak havoc on the hated enemy.

St. Clair was appointed major general a second time

St. Clair was appointed major general a second timeMassacre

The trap was sprung on 4 November – the warriors unleashing terrific sheets of lead into the Americans, who fell in scores. Down to last than half his force, St. Clair led a desperate bayonet attack to hold off the warriors who were closing in for the final kill. He managed to extricate the survivors but at the cost of over 600 killed and 300 wounded. The Battle of the Wabash stands as the greatest disaster in what would become a long series of conflicts between the oncoming Americans and the Indian tribes.

St Clair's defeat at the Wabash

St Clair's defeat at the Wabash

St. Clair was severely condemned by all, including his long-time ally, President Washington who launched an investigation into the causes of the disaster – the first investigation of the executive branch under the new United States Constitution. The inquiry exonerated St. Clair of wrongdoing but he was forced to resign from the army.

President Washington launched an inquiry

President Washington launched an inquiry

St. Clair was able to stay on as governor of the Ohio Territory – a tribute to a mix of politics (he was a staunch Federalist in a Democratic-Republican west) and his acknowledged administrative capacity. The republic had devolved into rabid partisan politics and the frontier was not excluded. St. Clair wanted to carve two Federalist-leaning states out of the Ohio Territory. He hoped that would bolster Federalist power in Congress. To that end he made vast personal investments in the region but the always cash-strapped federal government failed to reimburse him.

Northwest Territory - St. Clair's Legacy

Northwest Territory - St. Clair's Legacy

The Democratic-Republicans in Ohio opposed him and accused him of partisanship, duplicity, and arrogance. He did not help his case – pushing back on direction from the new capital in Washington and its now Democratic-Republican administration. An 1802 statement eschewing Congress’s control over the territory led to President Thomas Jefferson removing St. Clair from the office he held for well over a decade.

President Thomas Jefferson removed St. Clair

President Thomas Jefferson removed St. Clair

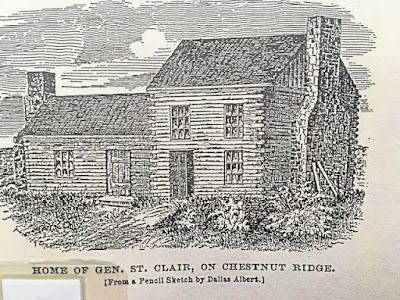

Losing his western investments and bereft of funds, St. Clair retired to western Pennsylvania. He and his wife lived with their daughter, Louisa St. Clair Robb, and her family in a cabin situated between Ligonier and Greensburg. Arthur St. Clair died in poverty in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, on 31 August 1818. He was 81. His wife Phoebe died shortly after and is buried beside him under a Masonic monument in St. Clair Park in downtown Greensburg.

St. Clair's final home

St. Clair's final home

Despite being frustrated by two controversial military defeats, St. Clair was a good officer, a capable general, and most importantly, an adept military thinker. Why else would Washington keep him at his side after Fort Ticonderoga? He was a very good administrator and his efforts helped not just win a nation but build one both at the seat of government and its wild -frontier. This makes the little-known medical student from Scotland among our nation's founders in every sense of the word.

St. Clair's Grave

St. Clair's Grave

September 30, 2021

Gentleman Johnny

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies begins a series of profiles of key historical figures in the next novel in the acclaimed series, The North Spy. In a spoiler alert of sorts, this installment of the adventures of Jeremiah Creed is built around the British invasion of New York from Canada in 1777. No one is more central to that affair than John Burgoyne.

The flamboyant and controversial on his best days, Burgoyne is the archetypal noble cum warrior cum literati-cum celebrity. Archetypal as an extremely unique personality can be… His sobriquet, Gentleman Johnny sums up his soldiers’ view of him – and his view of himself.

Military Brat or Bastard?Burgoyne was born 24 February 1722 in Sutton, to Captain John Burgoyne and his wife Anna Maria, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. Speculation is young John could be a bastard – the illegitimate issue of Lord Bingley. Bingley became John’s “godfather” and put him in his will as his heir if his daughters did not produce male heirs of their own.

There was certainly money to give John a running start in life. So at age 11, Burgoyne began attending the Westminster School in London. There he made some useful friends (always the intent) including Thomas Gage – future General and last Royal Governor of Massachusetts. Another close friend was James Smith-Stanley, aka Lord Strange, son of the wealthy and powerful Lord Derby. At 15, Burgoyne entered the British Army by purchasing a commission in the Horse Guards.

John Burgoyne

John Burgoyne

Since the Guards were stationed in London and his duties were light, he had plenty of time and opportunity to mingle with high society. He soon acquired the nickname, "Gentleman Johnny" for his stylish uniforms and fast living. But he quickly amassed large debts and it is believed he sold his commission in 1741 to settle them.

Return to the ColorsThe War of the Austrian Succession gave the young dilettante a chance to “reinvent” himself, or better yet, resurrect his military career. The British Army was expanding to meet the threat from France and in April 1745, he was commissioned in the newly formed 1st Royal Dragoons. Unlike most “bought” commissions, as a new regiment, Burgoyne received his commission at no charge. Promoted to lieutenant later that year, he served with his regiment at the Battle of Fontenoy where he led troopers in several charges against the French. By 1747, Burgoyne had enough money to purchase a captaincy – a rank that would provide the platform he needed to get noticed but the end of the war in 1748 cut off any prospect of further active service.

Battle of Fontenoy

Battle of FontenoyCupid’s Arrow

After the war, Burgoyne began to court Charlotte Stanley, sister of his close friend at Westminister School, Lord Strange. When Charlotte's father, Lord Derby, disapproved of the match, John and Charlotte eloped – causing scandal and her father to cut her substantial allowance. Since officers on inactive service received no pay, Burgoyne was forced to sell his commission for 2,500 pounds. The young lovebirds began traveling around Europe, mostly in France and Italy. But it was not all about love. During this period Burgoyne became an avid fan of the arts and literature, and this sojourn would help feed his muse. He also began to study treatises on warfare and tour battle sites and fortresses.

Cupid's Arrow

Cupid's Arrow

When his wife gave birth to what would be their only child, Charlotte Elizabeth, they went home to Britain. Arriving in 1755, his former schoolmate Lord Strange helped the couple reconcile with Lord Derby, who in turn helped Burgoyne purchase a captaincy in the 11th Dragoons. In 1758, Burgoyne moved to the elite Coldstream Guards where the ongoing Seven Years War helped rocket him to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In June 1758, he took part in a raid on St. Malo, France, where British forces burned French shipping. This was followed by another raid on Cherbourg under then Captain Richard Howe, who as Admiral would later command the Royal Navy in North America during the American War.

Richard Howe

Richard Howe

But John Burgoyne soon had new ambitions – command of one of the British Army's two new cavalry regiments, the 16th Light Dragoons. The new unit offered John the chance to put some of the ideas he had developed on military science into action. Burgoyne was no dilettante now. Unlike others who did not get directly involved in the administration of their regiments, he directly oversaw the stand-up of his unit and personally recruited officers from the landed gentry in Northamptonshire. He wanted a model unit, organized and equipped around his notions of military service: honorable officers, a firm sense of duty, and well-trained and equipped men who were treated with respect. He did not want his men to be the stereotypical dregs of society. To entice quality recruits, he tried to ensure his men had the finest horses, uniforms, and equipment.

Young Cavalry Commander

Young Cavalry Commander

In contrast to British Army norms and tradition, Burgoyne encouraged his officers to get to know the “other ranks.” His notion of warfare required the men to be free-thinking in combat – not mid-18th century robots a la Frederick the Great. To achieve this, he wrote and published a transformational regimental code of conduct. He expected better-educated officers too – encouraging them to take time each day to read and learn French as some of the best military texts were in French, such as the writings of Marechal Maurice de Saxe.

Marechal Maurice de Saxe

Marechal Maurice de Saxe

Somehow, Burgoyne found time (and money) to get elected to Parliament for Midhurst in 1761. But the next year he was off to Portugal a new brigadier general. He gained laurels for taking Valencia de Alcántara and then defeating the Spanish in the Battle of Vila Velha. During the battle, Burgoyne directed Lieutenant Colonel Charles Lee, future Deputy Commander of the Continental Army, to charge a Spanish artillery battery.

Charles Lee

Charles Lee

Burgoyne returned to Britain at the end of the war. In 1768 was returned to Parliament and got himself appointed governor of Fort William, Scotland. He was outspoken and rather “progressive” in Parliament – speaking for military and colonial reform, particularly in the East India Company. By now he was a major general but a large portion of his time was given over to the arts. He had enough time on his hands to pen plays and poetry. In 1774, his play The Maid of the Oaks was performed at the Drury Lane Theater.

Drury Lane Theater

Drury Lane TheaterMember of the Dream Team

When the American colonial resistance exploded into a war in April 1775, Lord George Germain, Minister for the Colonies, dispatched three of the most promising officers willing to confront the Americans (several others eschewed service against fellow Britons). So the dream team of John Burgoyne, William Howe, and Henry Clinton, all highly experienced and renowned veterans, sailed to Boston. With General Thomas Gage in command, there was a surplus of brass so Burgoyne exercised no field command. However, the debacle at Bunker Hill and the siege gave him ample opportunity to learn from others’ mistakes.

General Thomas Gage

General Thomas GageHome and Back and Home

Frustrated, Burgoyne sailed back to England in November 1775. His wife Charlotte died in February 1776, adding to his heartache. Although Burgoyne never remarried, he would begin a long affair with a married actress, Susan Caulfield, by whom he had four children between 1782 and 1788. The four were brought up in Lord Derby's household, and the eldest became Field Marshal Sir John Fox Burgoyne.

General Sir Guy Carleton

General Sir Guy Carleton

His wife gone and anxious to prove himself, Burgoyne returned to North America in the spring. This time arriving at Quebec, where he served under Governor Sir Guy Carleton, who had just stopped the American invasion. Although Carleton managed to push American forces from Canada – he failed to follow up with a drive on Albany, NY. Burgoyne became critical of Sir Guy’s caution and once more sailed for Britain.

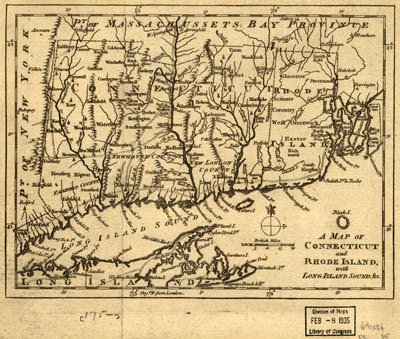

A Brilliant SchemeAmong his other traits, Burgoyne was a smooth talker. Once back in London, he set about pressing the Minister for the Colonies (and point man for defeating the rebellion), Lord Germain, on his plan to win the war in 1777. A three-pronged pincer with a thrust south from Lake Champlain to seize Albany supported by a detachment under Lt. Colonel Barry St. Leger approaching from the west through the Mohawk Valley. A northward advance up the North (Hudson) River from New York led by Sir William Howe would seal the Americans' fate. The objective was to cut off New England from the rest of the American Colonies. Classic divide and conquer. Burgoyne’s scheme would prove brilliant but impractical due to politics and geography.

Lord George Germain

Lord George Germain

Confusion between Germain and Lord Howe, commander-in-chief in North America, would be its undoing. Howe planned to move south on Philadelphia that year. It is unclear when Germain informed Burgoyne his support from New York City would be minor. Still, Burgoyne landed in Canada and assembled more than7,000 men – British regulars, German auxiliaries, as well as some Canadians and Indians.

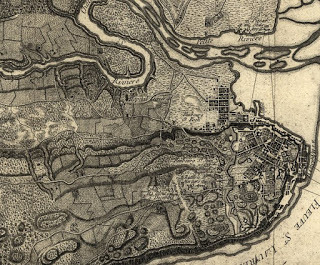

Burgoyne devised a brilliant but complex plan

Burgoyne devised a brilliant but complex planHowe (sic) He Lost

I will not go deeply into this complicated and crucial military event. My future novel, The North Spy, will chronicle most of the major, and some of the minor activities. Burgoyne’s plan was undone by several factors. Time was not on his side as the campaign season in the north was short and he started late and slowly. The terrain was some of the most difficult in Noth America with dense forests and numerous bodies of water and mountains to negotiate. And the Americans rallied most fervently against the incursion, spurred on by atrocities committed by Burgoyne’s Indian allies – both rumored and actual.

Delays & False AssumptionsThe initial delay was gathering enough vessels to exploit the excellent waterways – a virtual superhighway pointing right into the heart of the colonies It was already late June before they arrived on lake Champlain. Burgoyne’s assumption of widespread Loyalist and Indian support gathering around him was immediately dashed. This was a recurring failure in British thinking throughout the war. There was never a large number of Loyal Americans willing to come out and fight – few Native Americans and Loyalists joined his forces. Although Burgoyne took the bastion of the north, Fort Ticonderoga by early July, he made an operational error by pursuing the Americans. He began to stray from his supply line as his men were lured deeper away from the waterways.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga

A minor win at Hubbardton on 7 July only gave him false confidence. And Burgoyne’s advance south towards Forts Anne and Edward was delayed by the retreating Americans who blocked the roads and trails with trees and destroyed any bridges. Around this time he learned Howe was sailing to Philadelphia – the critical thrust from the south would not be. Meanwhile, the supply situation worsened as the army lacked sufficient transport that could traverse the region's primitive roads.

Battle of Hubbardton

Battle of Hubbardton

The need for supplies caused him to send a force of Germans foraging to the east where they stumbled into a hornet’s nest of American militia at Bennington on August 16. The New England militia under John Stark whipped the British, further inspiring men to the cause. Many of Burgoyne’s Indian allies began to sense the changing situation and started to drift off to plunder and go home. To make things worse, Barry St. Leger was turned back at Fort Stanwix. The other leg of the triad was gone. Burgoyne had two choices: consolidate at Fort Ticonderoga and continue the next year – or roll the dice and plunge farther south.

Battle of Bennington The Die is Cast

Battle of Bennington The Die is CastHe took the plunge. Burgoyne decided to abandon his supply lines and try to a “brute squad” push on Albany in time for winter quarters. He crossed to the west bank of the Hudson on 13 September. But just south of Saratoga waited a rapidly growing American army dug defense works designed by famed Polish engineer Thadeuz Kozciusko at a place called Bemis Heights. The weak Major General Horatio Gates commanded the force of mostly New England and New York militia – but he also had some crack continental troops sent north by George Washington. Gates may have been "Granny" (his nickname) but the next line of command had some of the best leaders of the war including, Brigadier General Benedict Arnold, Colonel Dan Morgan, Enoch Poor, Ebenezer Learned, and Benjamin Lincoln.

General Horatio Gates

General Horatio GatesFreeman's Farm

Burgoyne vacillated. His army was weakened and morale waning. And although Gates was himself content to sit behind his works and wait things out (not entirely a bad notion), he allowed Arnold to try a stratagem. On 19 September, Arnold and Morgan struck Burgoyne's men at Freeman's Farm. Fierce fighting ensued. Both sides were mauled but the British withdrew to regroup.

Battle of Freeman's Farm

Battle of Freeman's FarmBemis HeightsWith their supply situation critical, many of the British commanders recommended a retreat. Burgoyne anxiously hoped a small diversion from NYC launched by former dream team member Henry Clinton would draw some of the Americans south of Albany. But Clinton’s move was too little too late. Yet unwilling to fall back to Fort Ticonderoga, Burgoyne tried a last desperate die roll at Bemis Heights on 7 October. A strong column under General Simon Fraser was smashed and Fraser, his best subordinate, was killed by a sniper. So were precious regulars and Germans who would never be replaced. Burgoyne showed personal bravery and was several times nearly shot by American marksmen. When Fraser's column was repulsed, the Americans launched their own attack and punished the British, although they failed to take and hold the British defense works. But Burgoyne had been licked.

Battle of Bemis HeightsAn “Unconventional” Surrender

Battle of Bemis HeightsAn “Unconventional” SurrenderThe British withdrew to their camp near Saratoga. Meanwhile, the Americans had cut off his retreat north and were harassing his lines daily with sniper fire. Stymied in two pitched battles and with no chance now to fall back on his supply lines or smash his way south, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17 at Saratoga. Yet “Gentleman Johnny” tried to make lemonade from lemons in the way of a technical protocol. He managed to convince Gates (a former British officer) to let him sign a “convention” vice a capitulation via unconditional surrender. Also, he and his men were to be returned forthwith to Britain. Congress later set aside the deal. While the British and German officers returned home on parole, the “other ranks” threw down their arms under the watchful American militia and continentals and some 5,800 marched off to captivity in Boston and ultimately Charlottesville, Virginia.

Burgoyne Surrenders at Saratoga

Burgoyne Surrenders at Saratoga

To say Burgoyne returned to Britain in disgrace is an understatement. This was one of the worst defeats in British history – trumping Malplaquet, Fontenoy, or Carillon. The American rabble in arms had destroyed a British army in the field – convincing France to openly ally with the fledgling American nation, later followed by Spain. The impact on world history would be immense.

Burgoyne's demand for a court-martialwas denied

Burgoyne's demand for a court-martialwas deniedAttacked by the government for his failures, Burgoyne attempted to reverse the accusations by blaming Germain for failing to order Howe to support his campaign. He demanded but did not receive a court-martial to him of the disgrace. Instead, King George III stripped him of all titles. Once more Burgoyne was out of the army. But not for long.

Political WindsFrustrated by the lack of support from Lord North’s administration, one he had so strongly supported, Burgoyne switched his political allegiance from the Tories to the Whigs. Soon things turned around for Burgoyne.

Things went South for Lord North -to Burgoyne's advantage

Things went South for Lord North -to Burgoyne's advantage

When Lord North’s cabinet collapsed in 1782 Burgoyne was in favor with the Whigs and his rank of major general was restored, along with a colonelcy in the King’s Own Royal Regiment. Burgoyne wrangled one of the top appointments in the army – commander in chief in Ireland. He also became a privy councilor. But Burgoyne left government when Lord Rockingham’s government fell a year later. However, this gave him time to concentrate on his literary projects – now his only passion besides his mistress.

Burgoyne ReinstatedAcclaimed Playwright

Burgoyne ReinstatedAcclaimed PlaywrightBurgoyne wrote two plays, romantic comedies – Maid of the Oaks, written by 1774, and The Heiress, written in 1786, arguably his best work. He also collaborated with Richard Brinsley Sheridan in the production of The Camp in 1778. In 1780, he wrote the libretto of William Jackson’s The Lord of the Manor. Burgoyne wrote the translated version of Michel-Jean Sediane’s Richard Coeur de lion for a semi-opera production at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1788.

Actress Frances Abington in Maid of the Oaks

Actress Frances Abington in Maid of the Oaks

Despite his failed strategy and campaign at Saratoga, John Burgoyne remained best known for his literary achievements among contemporary and post-Revolutionary War Britons. He was most loved for The Heiress, which proved to be a great success and favorite to many before and after his death. Gentleman John Burgoyne died suddenly at his Mayfair home on June 3, 1792. He was buried at Westminster Abbey.

Burgoyne's Legacy was his plays

Burgoyne's Legacy was his plays

August 31, 2021

The Tailor Spy

The Irish in the American Revolution have their heroes and villains on both sides of the struggle. Although renowned for decades of resisting and fighting their British oppressors, there was no groundswell of Irish sentiment for the colonials fighting the far-off war. The average Irishman was just trying to survive and many were recruited into the British regiments in Ireland. And in America itself, the Irish immigrants, like the rest of the populace, were split in their sympathies. But one such transplanted son of Erin would play a secret role in helping free his adopted nation – and perhaps take some vengeance on the British.

Hercules Mulligan

Hercules MulliganKnown until recently only to historians and a few “buffs” of Revolutionary War skullduggery, the name Hercules Mulligan gained worldwide fame through the hit Broadway musical, “Hamilton.” Indeed, Mulligan’s fate was intertwined with that controversial Revolutionary War officer, political operative, and Founding Father. For Hercules Mulligan and his family, in many ways, gave Alexander Hamilton the boost every new immigrant needs to take things to the next level.

Early DaysHercules Mulligan came to New York City from Coleraine, County Antrim, Ireland, at the age of six, with his parents Hugh and Sarah Mulligan. The year was 1746 – long before the French and Indian War and all the political and economic events that would result in the struggle for America. Hercules's father quickly established himself as a successful New York accountant and the family thrived in the colonies. Along with Hercules came two brothers – of particular interest is his oldest brother Hugh, who became proprietor of an import-export business that took on as a clerk a callow youth from Nevis, one Alexander Hamilton.

King's College

King's CollegeHercules attended King’s College (now Columbia) and became an accountant until he turned to the haberdashery business. His first shop was along Water Street but he later moved to the more fashionable Queen Street in 1773 so he could attract a more affluent and influential clientele. That same year, his brother Hugh introduced him to the young prodigy, Alexander Hamilton. Hercules took Hamilton under his wing. Hamilton even boarded with Mulligan and his family while he attended King’s College.

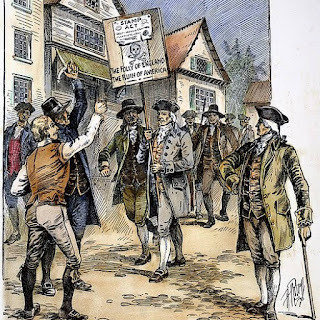

Secret PoliticsWhile Hamilton’s politics were shaped at King’s College, it is unclear when and how Mulligan began to sympathize with the rebel cause. Perhaps latent Irish sympathies and anger at the cruel Penal Laws in his native land? Or was it the course of events that followed the French and Indian War – the same events that pulled over one-third of the king’s loyal subjects towards a different political system? But the connection, the bond, was clearly sealed in those early days of simmering revolutionary fervor.

Stamp Act Protest

Stamp Act ProtestAt some point along the way, probably as early as 1765, Hercules helped pen an anti-Stamp Act underground tabloid called The Constitutional Courant. Mulligan later became a founding member of a radical wing of New York’s Sons of Liberty, organized to defend the colonists’ rights and resist British taxation. He was also was a participant, if not a leader, of the Sons of Liberty-inspired mob that, in 1770, attacked British soldiers in what was called the Battle of Golden Hill.

Battle of Golden HillA Model Citizen

Battle of Golden HillA Model CitizenAlthough he had a secret political life, Hercules outwardly remained a member of the establishment. The young Irishman married well – his wife was Elizabeth Sanders, the niece of a Royal Navy admiral and a well-connected member of New York's elite. The gregarious Irishman utilized his wife's family connections to build his business to cultivate friends and acquaintances among New York’s upper crust – most of whom were staunch Loyalists. Later, when New York was garrisoned by increasing numbers of British regulars, he added a coterie of officers as both clientele and contacts.

British occupied New York

British occupied New YorkThe gregarious haberdasher placed elaborate ads in Rivington's Gazette and other prominent Tory papers - ads that would draw top-tier customers and officers with their descriptions of “superfine cloths, gold and silver lace, fancy buttons, and epaulets replete with heavy bouillon.” If you build it, they will come. And come they did. Selecting, cloth, accouterments, measuring, and fitting all took time. Time that could result in slips of tongue, nuggets, and the knowing winks of a proud and haughty clientele aimed at impressing the popular haberdasher.

Secret RebelMulligan was at the center of an incident on 24 August 1775, an attempt on the HMS Asia, anchored in New York harbor. Under the cover of darkness, a band of New York militiamen, including Mulligan's company known as the "Corsicans," seized control of the artillery battery at the tip of the Island of New York (Manhattan). Hercules and his young boarder, Alexander Hamilton, were among them. But someone had alerted the crew of the HMS Asia and it unleashed its own guns on the rebels.

HMS Asia in New York harbor

Mulligan tossed a rope around one of the guns to pull it to safety. As he struggled, Hamilton approached and, small as he was, dragged the gun away. Hamilton then coolly rejoined the front lines to help move more guns – 20 were taken. Interestingly, one of the shots from the HMS Asia struck the roof of Fraunces Tavern – famed for later hosting General Washington’s farewell in 1783. With the support of Hercules, young Hamilton was promoted to captain and commander of an artillery battery in July the next year – just in time for the British onslaught on New York.

Artillery would team Hercules with Alexander Hamilton

Artillery would team Hercules with Alexander HamiltonIn 1776, Mulligan was one of the Sons of Liberty who tore down a huge statue of King George III in Bowling Green. They later melted down its lead into musket balls for rebel use. He had also joined the New York Committee of Correspondence, a key instrument in rallying support among the populace and keeping the colonies coordinated. An attempt to flee the city failed and Mulligan remained in New York after Washington's army was driven out during the New York campaign of summer 1776. By September of that year, New York was an occupied British city, and the situation called for more than political agitation – it called for espionage. But to do that effectively, Hercules would have to appear a Loyalist. As many flipped their allegiances during this time it did not raise much suspicion.

King George III statue tumbling downTailor Spy

King George III statue tumbling downTailor SpyExactly when our “model citizen” became a spy is still unclear. Fittingly, such things were not made a matter of record and secret agents often worked under a cover name, code name, or number. It is believed Alexander Hamilton suggested him to Washington while serving as aide de camp in 1777. But some sources do not have the haberdasher actually reporting to Washington until 1779. In any event, the transition was smooth, if not inevitable.

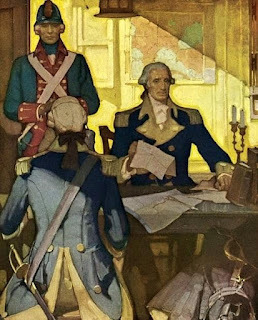

Alexander Hamilton as aide de camp to General Washington

Alexander Hamilton as aide de camp to General WashingtonAt his clothing shop, Mulligan would often measure his clients, chatting them up and picking up nuggets through elicitation. He also was very observant of military and political goings-on in the city. Years waging a secret political war had enabled Mulligan to hone the skills need to be an excellent intelligence operative in the occupied city.

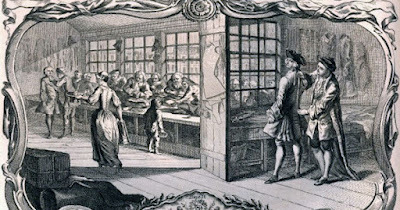

The perfect venue for elicitating nuggets from powerful customers

The perfect venue for elicitating nuggets from powerful customers

As living quarters for men of means became tight in occupied (and fire-ravaged) New York, Hercules opened a few rooms in his home to British officers – an excellent way to avoid suspicion, develop leads, cultivate relationships and elicit intelligence.

There is some belief Mulligan reported through the Culper Ring – the Setauket, Long Island-based spy operation made famous by the fictional TV show, TURN. And he may have done so. The key collector for the ring, Robert Townsend, operated his establishment down the street from Mulligan’s haberdashery. But Hercules used other channels as well. In fact, Washington’s key intelligence officer and spymaster of the Culper Ring, Major Benjamin Tallmadge once queried the commander in chief as to Mulligan’s status and activities. He was concerned Mulligan's activities might pose a threat to his ring. He would not have made the query if Mulligan was one of his assets.

Major Benjamin Tallmadge

Major Benjamin Tallmadge

So how did Mulligan smuggle his intelligence out of the city? One way was through his African American servant, Cato. Cato’s status enabled him to pass through British lines without arousing too much interest as Africans were believed to be pro-British (and most were). It is held by some that Samuel Culper used Mulligan’s servant as an alternate reporting channel on at least one occasion. Cato made many trips across lines but on his last, he aroused enough suspicion to cause his detainers, probably local Loyalist militia, to beat him severely. Despite the brutal treatment, Cato did not give up his mission or his boss. As it was, Mulligan used his high contacts to get Cato released, although his courier days were over.

Fraternal AffairHercules’s older brother Hugh also had a hand in espionage. His import-export firm Kortwright & Company had business dealings with the British military and with many influential Tory merchants in New York. As a shipper, he could visit ships in port, look at facilities and track the movement of supplies – providing valuable information of future British operations.

Hugh Mulligan had access to British shipping plans

Hugh Mulligan had access to British shipping plans

There is little known about the specifics of Hercules Mulligan’s reports but he is credited with reporting intelligence that saved General George Washington’s life on at least two occasions. That alone could make him one of the most important people of the war.

Cato's message from Hercules saved Washington

Cato's message from Hercules saved Washington

On one occasion, a British officer came to Mulligan late in the evening seeking a coat. Hercules began showing him different coats, all the while bantering and questioning his customer, who carelessly spilled the beans – he was setting out to capture George Washington. Mulligan dispatched Cato as soon as the officer left – enabling Washington to move to safety.

The other time, the British learned of Washington’s plan to ride to Rhode Island along the Connecticut shoreline. By pure luck, Hugh Mulligan was contracted to provide supplies for the British vessels. He quickly informed his brother and once more Cato slipped out of the city to warn Washington.

Under SuspicionThe affable and well-connected Mulligan did come under a cloud of suspicion at (at least) one point during the war. Ironically, it came from the notorious traitor himself, Benedict Arnold. Arnold was now in New York with the rank of Brigadier General in the British Army. One of Arnold’s tasks as commander of the West Point garrison had been to help orchestrate collection against the British in and around New York City. In that capacity, he had some inkling the tailor might be one of General Washington's sources.

Benedict Arnold - British Brigadier General

Benedict Arnold - British Brigadier GeneralWashington was very good at “compartmentalizing” operations. Very few of even his closest confidants knew who his spies were and those who did had only the knowledge absolutely necessary.

Hercules under questioning

Hercules under questioning

Arnold had Hercules arrested. Having been interrogated twice previously by the British, Mulligan was able to deflect questioning and maintain his aplomb. These skills – combined with his reputation as a loyal subject and friend of the British, carried him through. And because Arnold had no actual evidence to back up his accusations our tailor-spy was soon released.

Under Suspicion (Again)Hercules was a victim of his own success. Playing the loyal haberdasher to the British and Tories for almost eight years solidified his reputation as a collaborator among his fellow New Yorkers – a cynical lot by nature. Patriots and Whigs fingered him for an active Loyalist and traitor to the cause. After the British departed at the end of 1783, his thriving business and position in New York society were at great risk. Many Tories were run out of town and their properties confiscated. There was no reason this would not be the Irishman’s fate.

British evacuation of NYC

British evacuation of NYCBut the hand of His Excellency, General George Washington intervened. After the war, Washington is known to have quietly reached out to many hitherto unknowns and made it clear they fell under his special approbation. Many of these are believed to have been clandestine intelligence operatives: secret agents, spies, and couriers.

True Friend of Liberty

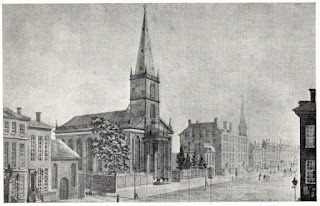

True Friend of LibertySo while in New York City, a grateful George Washington visited Mulligan’s haberdashery, had breakfast with the man to whom his life was owed, and was fitted for a set of new clothes, dubbing the secret patriot “a true friend of liberty.” This act protected Mulligan from being labeled a British sympathizer and collaborator. Beaming with pride, Mulligan commissioned a sign, which he forever proudly displayed outside his 23 Queen Street (today 218 Pearl Street) store: “Clothier to Genl. Washington.”

Queen Street post-war

Queen Street post-war

Although Cato’s fate is unknown, Mulligan struggled for democratic ideals in post-war America and co-founded the New York Manumission Society along with his long-term friend, Alexander Hamilton. Our tailor-spy died in 1825 at age 80 and is buried next to Alexander Hamilton in Trinity Church.

Trinity Church 1776 pre-NYC fire

Trinity Church 1776 pre-NYC fire

July 31, 2021

The Surgeon Spy

Doctor Benjamin Church

Doctor Benjamin Church

Church was a blue-blooded scion of Yankee forbearers who would be the envy of the Colonial Dames. Born 24 August 1734 in Newport, Rhode Island, the son of Benjamin Church, a Boston merchant and deacon of the Hollis Street Church, Church hailed from a family of New England military, civil and religious leaders that stretch back to the Mayflower through his great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Warren Church – daughter of Richard Warren, who arrived on the Mayflower.

Benjamin Church was born in Rhode Island

Benjamin Church was born in Rhode Island

Young Benjamin studied at the Boston Latin School – the typical springboard to Harvard College, from which he graduated in 1754. He then studied medicine under one Dr. Joseph Pynchon. Following this, like so many American surgeons, he finished his studies in London. There he married Hannah Hill. When he returned home it did not take long for him to build a reputation as one of the city’s best young physicians and surgeons, even treating the lawyer and future founder John Adams’s eye problems.

Future president John Adams was Church's patient

Future president John Adams was Church's patient

In the decade-long run-up to the break with Britain, Massachusetts, particularly Boston, was at the center of growing discontent and turmoil. Benjamin Church seemed to be right in the middle of things. Following the Boston Massacre on 5 March 1770, it was he who examined Crispus Attucks’s body. He also treated some of the wounded. This seemed to place him an ardent Whig and in 1773, he was called upon to give the annual “Massacre Day” oration, an annual commemoration used to stir up anti-British sentiment. He proved a gifted orator.

The Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre

Dr. Church became one of the leaders of Boston’s Sons of Liberty, working among the likes of Joseph Warren, Sam Adams, John Adams, and Paul Revere. By 1774, the prominent surgeon was a delegate to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress – later joining its Committee of Safety, the colonial entity responsible for preparing for armed defense.

Our Surgeon Goes to WarApril 1775 marked the formal outbreak of hostilities between the American colonists, particularly the New England colonists and the Royal authorities. Although impendence was not yet the stated goal, the fight for the rights of the Americans had all the trappings of war. And our favorite surgeon was caught up in the middle of it. In May 1775, Church traveled to Philadelphia where he consulted with Congress about the military situation in Massachusetts. As head of the Committee of Safety, he signed the order mandating the building of defense works at Breed's Hill and Prospect Hill.

Breed's Hill defenses

Breed's Hill defensesIn July 1775, he was named Director General and Chief Physician of the newly established Medical Department of the Army making him head of both the hospital department of the first army hospital and of the first headquarters of regimental surgeons. This was a prestigious appointment, essentially putting him at the pinnacle of his profession.

Doctor Gloom?Interestingly, Church proved an indifferent medical administrator and had a barrage of complaints lodged against his medical system management by the army’s regimental surgeons. He pushed back – citing jealousy as the real motivation of his accusers and soon requested to be relieved of his duties. Why would a renowned and highly trained surgeon (18th-century term for a physician) have a hint of failure at what should be a core competency? Perhaps our doctor had other things on his mind.

As chief army surgeon, Church was responsible for medical suppliesOther Things

As chief army surgeon, Church was responsible for medical suppliesOther ThingsAnd other clouds were swirling about the upstanding Whig leader. In the espionage world, these were called anomalies and indicators. And although they were there – it would take an overt event to begin to bring things together. There were suspicions of his allegiance to the cause, especially the cause of independence. At this time there still may prominent Whigs who were ambivalent to a complete break with Britain. But was he one of them?

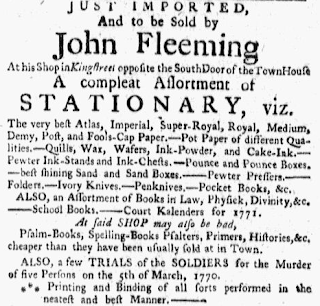

Yes, Church had an English wife and his brother-in-law a prominent Tory printer, John Fleming. But so many had ties to Britain and the Tories that he could not be considered completely abnormal. In the run-up to rebellion, Church developed a reputation as a prominent patriot writer and poet. But as it turns out, he sometimes responded to his own patriotic open letters in the press with “op-ed” pieces taking the Tory side!

Advertisement for John Flemings Printshop

Advertisement for John Flemings Printshop

As it would later turn out, he also had at least one meeting with General Thomas Gage, which was reported, probably by the Mechanics, a spy network run by Paul Revere (see the Yankee Doodle Spies post on them). Church explained it away – as many suspected spies all too easily do. What was then unknown, was Church was in debt, some of which was caused by his keeping a mistress. And she was not his first, as it turned out.

Did Paul Revere's Mechanics have the doctor in their sights?

Did Paul Revere's Mechanics have the doctor in their sights?A House of Cards

In July 1775, Doctor Benjamin Church’s house of cards collapsed when a secret letter was intercepted and decoded. A cipher letter was sent to a British officer in Boston, named Major Cane, through a former mistress. But Eros intervenes in strange ways – the letter was intercepted by another of the woman's ex-lovers, and be sent to the new Continental Army commander-in-chief, General Washington in September. It took some effort to decode it but they were rewarded for their efforts as it contained information about the American forces gathered around Boston. Although little of the information was critical, the missive showed clearly Church’s allegiance to the King and sought instructions for further secret correspondence. A bombshell striking Washington’s headquarters could not have been more explosive than this news!

King George IIIA General Court Martial

King George IIIA General Court MartialAt the court-martial in Cambridge, which immediately followed, Church admitted penning the letter (typical ploy) but declared he intended to impress the British with the Continental Army’s strength to prevent an attack while it was still short of ammunition. And he thought it might help bring about an end to hostilities. Although impressing the British probably helped Washington’s situation, the latter was an indicator of Church’s ambivalence. Because there was no “espionage statute” and America was not yet an independent nation and thus could not be “betrayed,” the court, with Washington presiding, determined Church engaged in a “criminal correspondence with the British.”

General Washington penned a report following Church's court-martialReport to Congress