S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 2

March 16, 2025

The Sailing Irishman

This special Saint Patrick's Day installment celebrates Commodore John Barry: The Irish lad who became the father of the US Navy.

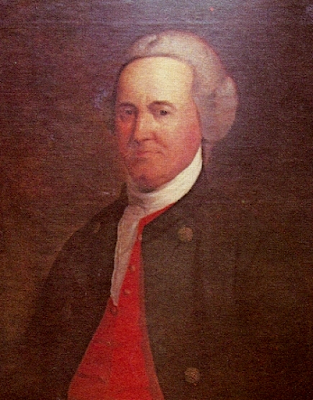

John Barry

John Barry

1745—Ireland. In a small tenant farm along a windswept coastline in County Wexford, a boy named John Barry is born into a family of poor Catholic farmers. Life under the English penal laws ground Irish spirits into the sod. Like many Irish families, the threat of eviction always loomed, and one day, the landlord forced them off their meager piece of land. Homeless, the Barrys moved to the rugged seaside village of Rosslare. The luck of the Irish—hardly, but it did offer young Barry a way out. He learned the ropes on his uncle’s fishing skiff, and sailing it through choppy waves was the lad’s first call of the sea. Who could predict that someday he’d make the Royal Navy tremble at his name and build what would eventually become the world’s most powerful navy?

Cabin Boy to CaptainBarry’s no stranger to hard knocks. As a lad, he barely had shoes, but he’s got grit. By his teens, he was aboard ships, starting as a cabin boy—fetching water, scrubbing decks, and dodging the mate’s boot. The sea is a brutal school, but Barry is a quick study. With broad shoulders and a cool head that marked him as a natural leader, he quickly climbed the ranks. The 1760s found him in Philadelphia, a bustling port on the Delaware River, becoming wealthy through trade. By twenty-one, Barry was a merchant shipmaster, captaining vessels for big names like Reese Meredith. With his impressive height—over six feet—he was burly, yet calm and composed even in raging storms and churning seas. Soon, he was in high demand as a skipper. “Big John” Barry was the man owners wanted at the helm of their ships.

Citizen of Philadelphia

Citizen of Philadelphia

He spends years hauling cargo across the Atlantic, dodging icebergs and setting speed records—such as the fastest day of sailing in the century aboard the prestigious Black Prince. By the 1770s, John Barry had reached the pinnacle of his fortunes. However, storm clouds were gathering on the horizon—tension between the colonies and British authorities. Soon, Barry would exchange merchant manifests for cannonballs.

Merchant Captain at Sea

Merchant Captain at SeaFrom Merchant Navy to theContinental Navy

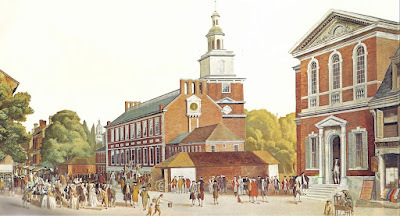

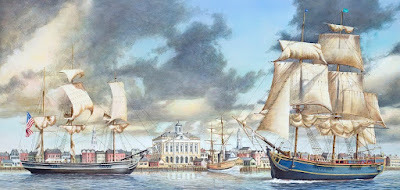

When the First Continental Congress gathered in 1774, Barry was already friends with future Revolutionary War financier Robert Morris. When the Second Continental Congress opted to create a navy in 1775 using merchant vessels, Barry’s Black Prince was transformed into the USS Alfred, which raised the Grand Union flag—America’s first naval ensign. Barry advocated for a naval command and was appointed captain of the USS Lexington, a 14-gun brig, that December.

Command of USS Lexington

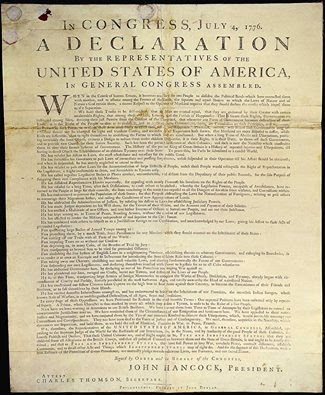

Command of USS LexingtonHe was the first army or navy officer to receive a Continental commission, signed by none other than John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress, on March 14, 1776. History is about to be made!

First FightBarry’s first action occurs on April 7, 1776, off the Virginia Capes. Barry proves his resolve. The Lexington engages with the British tender Edward, a spirited ship serving HMS Liverpool. Broadsides are exchanged—cannonballs flying, wood splintering—for an hour and twenty minutes. Cool as ever, Barry shows his fortitude, issuing orders, and when the smoke clears, Edward strikes her colors—the first British ship captured by a Continental vessel. Barry sails his prize into Philadelphia—the American navy’s first!

Fighting Captain

Fighting CaptainWarrior on Land and Sea

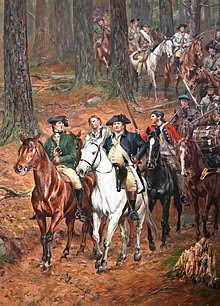

By late 1776, the Cause was at its lowest point. Washington’s dwindling army was reeling from New York, retreating through New Jersey. What could Barry do? His next assigned ship, the frigate Effingham, was still in the shipyard. Eager to join the fight, he gathers sailors, marines, and heavy artillery, forms an ad hoc naval brigade, and marches to Washington’s aid. At Trenton, his crew transports artillery through snow and ice, pounding the Hessian lines. His brigade performs again at Princeton. Washington personally thanked Barry before charging him with escorting wounded prisoners to British General Cornwallis under a flag of truce. A fighting Irishman on land or sea!

Commanding Guns at Trenton

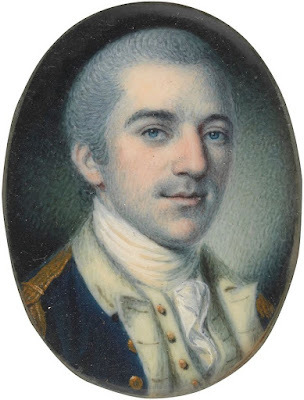

Commanding Guns at TrentonBack on the water in 1777, Barry commanded the brig USS Delaware and began raiding British shipping in the river of the same name. Like shooting ducks in a barrel for the seasoned naval leader, he took over twenty prizes, including the armed schooner Kitty. In 1778, Barry took command of the frigate Raleigh, seizing three more prizes before she ran aground during a skirmish with British warships. Barry was forced to scuttle his ship but quickly took command of another vessel, the USS Alliance, the fleet’s fastest ship. In 1780, he was given a secret mission: to take Colonel John Laurens to France. That mission—obtaining loans and supplies—helped secure Washington’s victory at Yorktown in October 1781. To top it off, Barry captured a few British prizes on the return trip—just because he could.

Secret Mission to France

Secret Mission to FranceThe Final Fights

Barry’s most brutal fight occurred on 29 May 1781. Standing tall on the quarterdeck of the Alliance, he faced the struggle of his life. Two British sloops, the HMS Atalanta and HMS Trepassey, pounced on him. All hell broke loose as they closed in—broadsides shredding sails, grapeshot tearing through flesh. Barry sustained an awful wound when a piece of grapeshot tore through his shoulder. He remained at his station, rallying his crew and shouting commands, but the "effusion" of blood eventually forced him below deck. Ultimately, both British warships struck their colors—a double surrender. Now, even British captains concede that he’s an American sea captain to reckon with.

Taking on a Brace of Warships

Taking on a Brace of WarshipsFittingly, on 10 March 1783,Barry fought the war’s last naval battle off Cape Canaveral. His Alliance squaredoff against HMS Sybille and a squadron. Barry is in a bind as he is convoyingthe , loaded with cash andsupplies from the West Indies. Barry outguns Sybille, but the rest ofthe squadron is on him. He abandons this newly won prize, Sybille, opting tosave the convoy and get Duc de Lauzane safely to port. With the warcoming to a close, Barry had made his mark as a fighting captain.

Final Fight

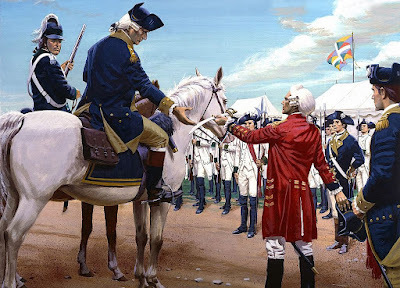

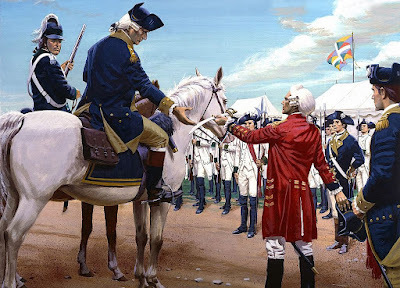

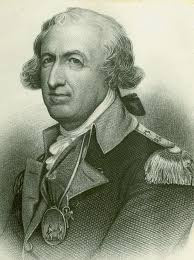

Final FightFather of the Navy

Our Celtic commodore quickly returned tomerchant sailing, making a historic voyage to China in 1787—opening trade withthe “reclusive empire.” However, in 1794, with the U.S. Navy forming under theNaval Act, Barry was asked to serve his nation once more—as its firstcommodore! President Washington himself presented Barry Naval Commission NumberOne. Barry began overseeing the construction of the 44-gun frigate USS UnitedStates, his flagship.

USS United States

USS United StatesDuring the Quasi-War with France(1798–1801), Barry returned to work, capturing French merchantmen in the WestIndies while training the next generation of naval leaders—future legends like Stephen Decatur and Richard Dale.

The Final WatchDespite increasingly worseningasthma, Barry continued to sail. But on 6 March 1803, United States slidesinto port with Barry on the quarterdeck for the last time—his sea duty done. He may have given up his ship, but not theNavy, staying on as its head until he died on 13 September 1803 at hisStrawberry Hill home near Philadelphia. The first commodore was buried with fullhonors at St. Mary’s Churchyard. While happily married, Barry died childless.But his legacy lives in the Navy he shaped and with the men hementored.

John Barry Gravesite

John Barry GravesiteLegacy of a Legend

Some random shots about JohnBarry: Author of a signal book for better fleet communication, early advocatefor a standalone Navy Department (it happened in 1798). Barry was a man of God—he began each day with a Bible reading. He was a brilliant leader of men—he cared for his crew, keeping them fed and fit. Wise practitioner of discipline— quelled three mutinies with a firm hand and afair heart, earning lasting loyalty from his men.

Barry's Advocacy Paid Off in 1798

Barry's Advocacy Paid Off in 1798Many tributes came: fourdestroyers were named USS Barry, Barry statues stand in Wexford and D.C., and the CommodoreBarry Bridge. Rhode Island celebrates September 13 as “Commodore John BarryDay.”

John Barry statue in Wexford, Ireland

John Barry statue in Wexford, IrelandWho's the Best?

Though not as well-known as John Paul Jones, Barry excelled in war and peace. Starting as an Irish cabin boy and rising to American commodore, he fought on land and sea, built a navy from the ground up, and created a blueprint for courage. Historians often refer to John Barry as the “Father of the American Navy,” a title many attribute to John Paul Jones. Jones's post-Rev War contributions were uneven, with him accepting a commission in Czarina Catherine the Great's navy (see my blog, Yankee Doodle in the Crimea). However, unlike Jones, Barry's legacy includes longevity and institution-building. Jones had flair, while Barry made a lasting impact.

John Paul Jones as Russian Admiral

John Paul Jones as Russian Admiral

Next time you hear “I have not yet begun to fight,” tip your hat to Jones—but raise a glass to the quiet giant who led the Revolution to victory and beyond. Fair winds to you, Commodore Barry.

John Barry in His Office

John Barry in His OfficeFebruary 21, 2025

Book Review: Gone for A Soldier

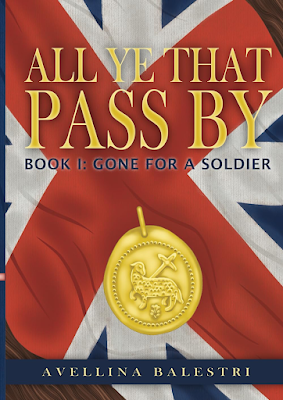

Avellina Balestri's "All Ye That Pass By: Book 1: Gone for a Soldier" is a significant addition to historical fiction. It focuses not merely on facts, deeds, and battles but also on the nuanced interplay between faith, identity, and the tumult of war in the late 18th century.

With the backdrop of the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, "Gone for a Soldier" brings to life the lesser-told stories of British Loyalists and the Catholic recusants in England. The novel's protagonist, Edmund Southworth, is a Catholic in a time when his faith could lead to ostracism or worse, providing a unique perspective on the conflict between personal belief and societal expectations. Balestri uses this setting to delve into the complexities of identity during a time of upheaval, where allegiances were often torn between country, faith, and family. All this is set against the vast canvas of Canada and New York during the failed British Saratoga campaign.

The Players

The fictional English Catholic Edmund Southworth stands at the heart of the narrative, embodying the conflict of his era. His journey from a boy intrigued by military life to a man grappling with the contradictions of his Catholic faith and his duty as a soldier is portrayed with depth and sensitivity. Balestri's character development shows Edmund's internal conflicts, moments of doubt, and eventual growth into a figure of moral strength. Generals John Burgoyne, Simon Fraser, and other key officers interact across the vast canvas of this work, and the author catches their personalities just right. Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne has a unique role as Edmund's mentor.

General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne

Other characters, such as Edmund's Protestant friends, military figures from the British army, and even historical personalities such as King George III, are made real, building a grand and intimate narrative. Her characters serve not just as foils to Edmund but also as mirrors to society's varied perspectives on religion, politics, and war.

The novel explores several themes, with faith and loyalty being central. Balestri examines how these concepts intersect with personal identity and societal roles. Edmund's Catholic faith is a constant undercurrent, influencing his decisions, interactions, and perception of the war. This exploration of faith in a time of conflict adds a layer of philosophical inquiry to the narrative, questioning how one reconciles personal beliefs with the demands of war.

Death of Simon Fraser

Death of Simon Fraser

Loyalty is another theme intricately woven into the plot. Edmund's loyalty to his faith, king, and comrades in arms often clashes, providing a rich ground for character development and ethical discourse. The novel also subtly critiques the notion of loyalty to a nation or cause when that loyalty might conflict with one's moral or spiritual beliefs.

Balestri's prose is both lyrical and precise, capturing the essence of the 18th-century setting while maintaining a pace that keeps the reader engaged. The narrative style is reflective, often pausing to ponder the implications of actions and the nature of human endeavor, which suits the novel's introspective themes. Readers who demand rich historical detail with engaging character interactions and plot developments will enjoy this. As John Burgoyne was a playwright himself, there are many references to Shakespeare's work.

The Bard

The Bard

"All Ye That Pass By: Book 1: Gone for a Soldier" does not just entertain; it educates. Besides being a significant Revolutionary War tale, by focusing on a Catholic perspective during a pivotal time in British and American history, Balestri fills a gap in historical fiction where religious minorities' experiences during colonial conflicts are often overlooked. This novel is a valuable resource for educators looking to give students a more rounded view of the historical period.

Burgoyne Surrenders at Saratoga

Burgoyne Surrenders at Saratoga

"All Ye That Pass By: Book 1: Gone for a Soldier" is a commendable piece of historical fiction that combines a passion for history with a profound understanding of the human condition. It challenges readers to think about loyalty, faith, and identity in ways that are still relevant today. This work gives readers a rich tapestry of historical events viewed through an intensely personal narrative lens, compellingly exploring human resilience, loyalty, and the quest for spiritual and personal truth.

This book is for anyone interested in the intersection of faith and war (and who isn't?) or readers seeking a different perspective on the Revolutionary War period. It is a testament to Balestri's skill in weaving history into a compelling narrative, making readers not just spectators but participants in Edmund Southworth's moral and spiritual journey. We await a future book to learn where his journey takes him.

January 30, 2025

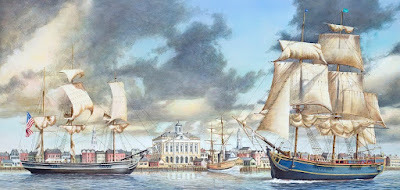

Island in the Sun

Large puffs of white moving casually with the trade windshighlighted the bright blue November sky over Oranje Bay. Isaiah Robinson,captain of the 14-gun brig Andrea Doria, put his spyglass to his eye.Ahead were the twin peaks with verdant sides that rose rapidly from the sandyshore, on which stood the Dutch trading port city of Oranjestad. He shifted hisglass to the large stone fort that sat astride the bluffs overlooking the fortand anchorage that was his destination.

“How will they receive us, sir?” asked a young midshipmanstanding at his side. The United States declared independence from Britainearlier that summer but had not received diplomatic recognition.

“We shall know soon enough, Mister Sewall,” repliedRobinson.

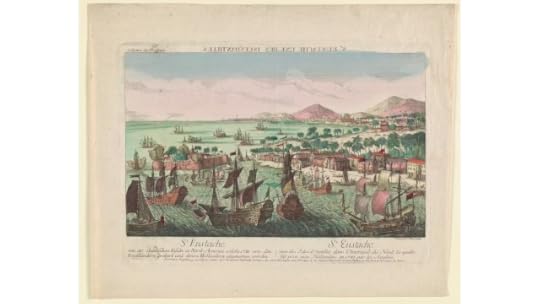

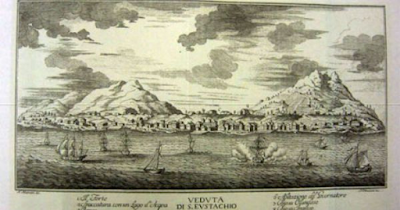

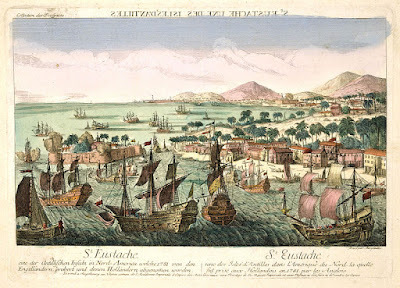

Entering the Harbor at Sint Eustatius

Entering the Harbor at Sint EustatiusThe First Salute

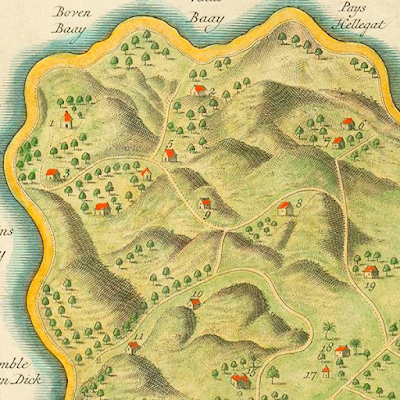

The Andrea Doria sailed briskly and then lazilytoward the harbor, cluttered with trading ships throughout the New World andEurope. Sint Eustatius, part of the Dutch Antilles, was a duty-free port that,since its occupation by the Dutch West Indies Trading Company in the early 17thcentury, was a hub for maritime trade—both legal and illicit. Tobacco, rice,cotton, and rum passed through her, as she was the hub of a global supply chainthat served two hemispheres. But the port was sadly the transit point for theworst kind of trade, human chattel.

Robinson snapped his glass shut and nodded to the GunnersMate. “Fire the salute!”

Thirteen of the fourteen barrels flashed and belchedsmoke—one for each state. Andrea Doria had formally announced her arrival.Robinson wondered, What will be their reply?

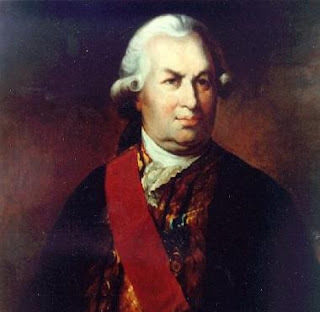

From his perch at the fort, the governor of the island,Johannes de Graaf, watched the salvo fired by the brig below. He turned to thebattery commander and doffed his plumed hat. A salvo of eleven guns erupted,belching a cloud of gun smoke above the harbor.

Captain Robinson smiled in satisfaction. “The signal of a returnedsalute is two guns less than the saluted.”

“What does it mean, sir?” asked Sewall.

Robinson did not reply to the young officer but turned tothe entire crew. “The United Netherlands recognizes us as a sovereign nation!”

The crew erupted in a long round of “Huzzahs” as the AndreaDoria made its way to safe harbor.

The First Salute - Andrea Doria

The First Salute - Andrea DoriaIsland in the Sun

I slightly changed my promise to dedicate the next feweditions of the Yankee Doodle Spies blog to characters in the series’ nextnovel, The Reluctant Spy. Instead, we will profile a place thatplays a significant role in the unfolding of this adventure tale. This uniqueplace is an island set in the West Indies. An island that played an essentialpart throughout the American Revolution and an important part in the fifth bookin the Yankee Doodle Spies series, The Cavalier Spy. And as those whoread it are aware—this island is Sint (Saint) Eustatius, sometimescalled Statia.

Governor Johannes de Graaf

Governor Johannes de GraafRevolutionary Role

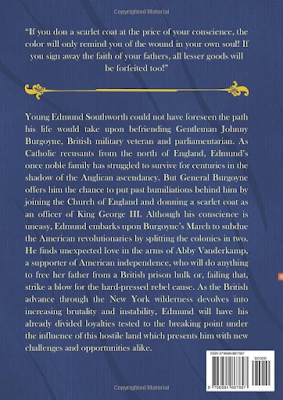

Sint Eustatius’s role in the American struggle forindependence did not end with that “first salute.” In fact, Governor de Graafwelcomed the crew, and Robinson provided him a copy of the Declaration ofIndependence and a letter written in Hebrew, destined for the Jewish merchantsin the Netherlands. Sint Eustatius had many Jewish settlers who helped make theisland the trading and banking hub that connected the Old World with the New.

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence

When Robinson and his crew took to shore, they found athriving port town with hundreds of storehouses, shops, inns, taverns, and bordellos.The storehouses were jammed with goods from the region’s islands – coffee,cocoa, and rice plus rice, tobacco, and wood from North America and finishedproducts from Europe. The bay was jammed with ships from every corner of theworld, waiting to unload or take cargo on board. The little island, a “duty-free”port, was as busy as Amsterdam’s, taking in 3,000 ships a year.

Port of Amsterdam

Port of AmsterdamThe Jewish Community

The large Jewish population was the lifeblood of the island’s prosperity. In the early 18th century, Sephardic Jews immigrated to Sint Eustatius from the Netherlands, bringing entrepreneurial skills and talent and establishing financial relations with their brethren in Europe and elsewhere. The population eventually comprised one-tenth of the island. These tradesmen became prosperous enough to build the largest synagogue in the New World, Honen Dalim. Stone bricks were brought in from Europe to build the massive structure.

Many Trading Houses Jewish Owned

Many Trading Houses Jewish Owned

Though short on natural resources, the little island in thesun boasted a global web of traders and maritime concerns. The Jewish settlerson St. Eustatius made up a large proportion of those merchants who were also“illegal” sellers of war materials and supplies to the Americans. Couple thatwith the banking interests in Amsterdam, and you had the makings of a systemthat had some refer to the island as the “Armory of the American Revolution.”

Prosperous Trading Hub

Prosperous Trading HubRobinson would meet with some of the local Jewish businessmen and purchase munitions. This was the beginning of a covert (or not so covert) trade that exchanged American cash crops, such as tobacco, for the necessities of war. This was a crucial pipeline during the early years of the struggle for independence.

Smugglers HubBut the pesky island that flaunted the rules of maritime tradewas in the crosshairs of the empire that policed maritime trade—at leastwherever the navy sailed. However, political and diplomatic niceties preventedthe British government from doing much to stop the clandestine trade thatprovided the American rebels their lifeblood. As long as the Netherlands andFrance were not open allies of America, the better policy was to sendoccasional squadrons to police the waters. But stamping out the nest of smugglersand (to the British) illicit traders) would have to wait.

Smugglers Avoided Tariffs - But Also Supplied the American Revolution

Smugglers Avoided Tariffs - But Also Supplied the American Revolution

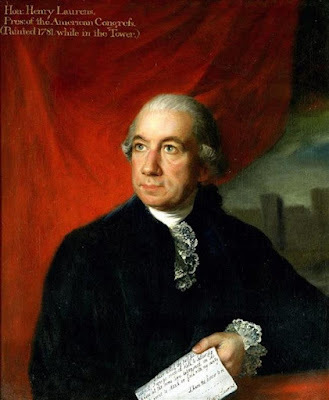

A few years into the war, London realized that the threatposed by the little island needed addressing. By 1780, the Admiralty felt thetime was ripening for action. France and Spain were in the war, and followingthe revelations captured along with American emissary Henry Laurens, the focushad turned to the West Indies, where the British felt their greater economic interestlay. With the Southern strategy in play, everything lined up for a reckoning.

The Admiralty

The AdmiraltySend Rodney

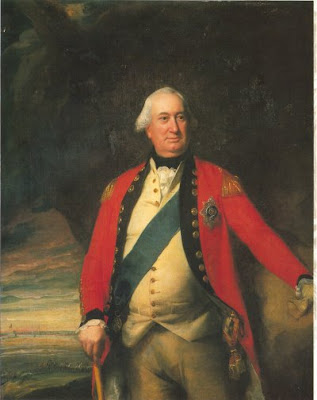

British Admiral George Rodney, a competent and well-thought navalveteran, was given the task. In late 1780, he sailed with a fleet of fifteenships of the line, numerous support ships and transports, and some 3,000 men todeal with the “nest of vipers” once and for all. Arriving at the harbor entrance on 3 February1781, the arrayed ships posed an impressive site. With some 1,000 naval guns, Governorde Graaf could only look down in dismay as he had only a dozen cannons andfifty men. He accepted Rodney’s offer of surrender.

Admiral George Rodney

Admiral George RodneyWorse Than Thought

The British admiral was stunned by the cornucopia ofsupplies and munitions on the island and the number of vessels laden with goodsin the American trade. Beaches were lined with warehouses brimming with goods,primarily sugar and tobacco. Others were crammed with naval stores—the timber, resin,tar, and hemp rope needed for ships. The magnitude of the island's contributionto the American war was further evinced by the number of munitions taken that belongedto the Royal Navy—sold by British merchants on nearby St. Kitts!

Full Storehouses and Magazines

Full Storehouses and Magazines

Rodney set to work confiscating whatever had value. Withlarge gambling debts, the more he could seize for Britain, the larger his shareof the spoils. The admiral torched, dumped, or looted what he could. The islandwas sacked like a medieval city. His disdain for the Jews was manifest—hebelieved many prosperous merchants were mainly responsible for the support ofthe Americans. In an act reminiscent of later Boer war tactics, Rodney had manyof the island’s prominent Jewish leaders rounded up and packed them off to St.Kitts. While now destitute families watched in horror, he had all their possessionsseized.

The British Take Sint Eustatius

The British Take Sint Eustatius

Meanwhile, Rodney took his eye off the ball. He violated hisorders to destroy the supplies meant for the American forces and shadow aFrench fleet bound for North America under Rear Admiral Francois Joseph Paul deGrasse. As he tarried on Sint Eustatius to continue his plundering, the Frencharrived in American waters and set sail for the Chesapeake. Rodney sent part ofhis fleet to join Admiral Hood while he, now ailing, sailed for England. DeGrasse and Hood squared off at the Battle of the Chesapeake, where the Frenchdrove off the British. They then bottled British General Charles Cornwallis’sarmy at Yorktown, sealing the fate of Britain in North America.

Admiral de Grasse

Admiral de Grasse

The British occupation of Sint Eustatius did not last long. Monthslater, a French fleet recaptured it and was returned to Dutch control in 1784.But the island in the sun was a shell of its former self. Months of destructionand plundering by Hood bankrupted the locals, and the population of around8,000 began to dwindle. With the war over and the former British colonies nowfree to trade at will, its importance dwindled.

Statius Contemporary Map

Statius Contemporary MapDuring the Napoleonic Wars, the French and British clashedover it (the Netherlands was made a client and then absorbed by France). TheCongress of Vienna returned Sint Eustatius to the Netherlands in 1816. But the“Golden Island” would never be the same as it was during its halcyon days ofthe late 18th century.

The Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna

The tale of the island in the sun has two “what ifs.”

The first is obvious. What if Rodney had not bent to his avariciousside and followed his orders instead of spending months looting andexpropriating but pivoted toward the French threat after taking the island?Would America’s fate, and that of the world, have gone differently?

The second is more obtuse. But what if the Jewish populationhad been left untouched and not gone into a diaspora? Would their trade andfinance know-how have grown Eustatius an even greater regional magnet for tradeand finance, leading the entire West Indies to prosperity?

Visitors to the island today could scarcely imagine its briefbut essential role in events that shaped the course of history. But the island inthe sun did have its role—and it is one we should never forget.

December 31, 2024

Palmetto Patriot

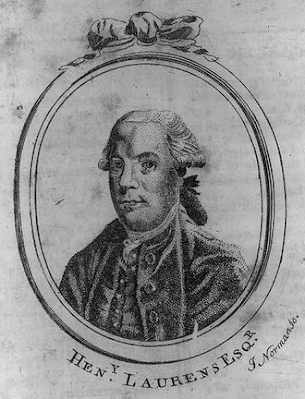

This edition begins a series ofprofiles to introduce some of the historical characters readers will meet whenthe fifth historical novel in the Yankee Doodle Spies series is released in2025. One of the first historical characters the reader will encounter is HenryLaurens, a little-known but essential South Carolina founder who became the Continental Congress's president.

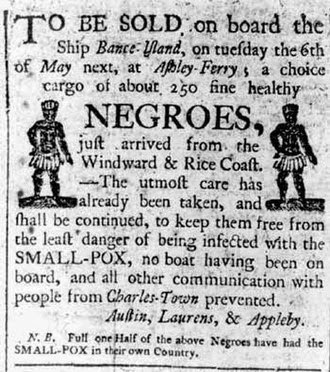

Man of Means

Laurens was born the son of awealthy Huguenot businessman, John Laurens, in 1724. After receiving his earlyeducation in South Carolina, his father sent him to Britain, where he cut histeeth on managing money and accounts. His experience in England served him wellon his return to South Carolina a few years later and, combined with his strongwork ethic, launched him on the path to great prosperity as one of the mostpowerful merchants in the colony. In just a few years, Laurens expanded hisinterests by purchasing plantations and expanding his interests in the ricetrade, but sadly, his big bucks were made in the slave trade.

Laurens's Company Advertisement

Laurens's Company Advertisement

In 1750, Laurens married thedaughter of a wealthy South Carolina rice planter. Eleanor Ball would bearthirteen children, dying in 1770 right after her last child's birth. Most ofhis children died young, but at least four grew to adulthood, and one, JohnLaurens, would reach prominence during the American Revolution.

John Laurens

John Laurens

Laurens joined the South Carolinamilitia and rose to lieutenant colonel while serving in warsagainst the Cherokee and the French and Indian War. Like many of the wealthyplanter class, he also served in the colonial assembly, where he was deemed aconservative and leaned Tory.

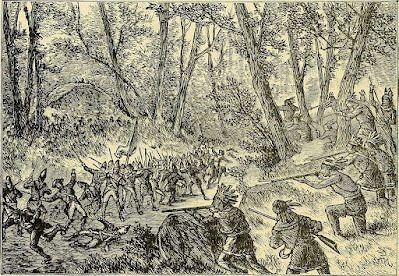

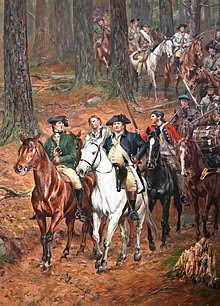

Militia Fighting the Cherokees

Militia Fighting the Cherokees

As the political situationbetween Britain and the colonies worsened, Laurens was drawn to the Whigs—but sufferedattacks from both sides. A mob of radicals stormed into his house and tore itapart in the search for stamped products. However, British Customs officialsconfiscated three of Laurens's merchant ships during the Townshend Acts. Thismade him more sympathetic to the Whigs, and he published a letter calling outthe British for their restrictions on American trade. Still, he remained apartfrom those advocating direct action or independence.

Laurens's Ships Seized by British

Laurens's Ships Seized by British

A 1771 trip to London to check his sons' education changed things. Incensed by the corruption in British society, Laurens became closer to the Whigs. Three years later, when he returned to America, he supported independence.

Carolina PoliticsBy 1775, the rebellion was infull swing, and the cautious Laurens fully committed to the cause. He thrusthimself into active politics and was elected to South Carolina's ProvincialCongress—an illegal body that soon replaced royal authority. Laurens ran theSouth Carolina Committee of Safety, a critical post as the colonies preparedfor armed conflict with Britain. He clashed with some of the more radicalpoliticos in the state when he championed property rights in the state's newconstitution to the extent of safeguarding the property of Loyalists fromconfiscation. Laurens served as the vice president of the new government of SouthCarolina from March 1776 to June 1777.

South Carolina Provincial Congress

South Carolina Provincial Congress

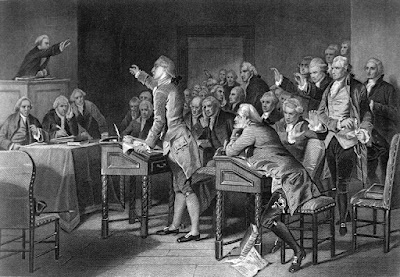

Although long a fixture in hishome state, Henry Laurens entered the national stage in June 1777 when hejoined the Second Continental Congress as a South Carolina delegate. The next November,he followed John Hancock as president of the Congress—a sort of speaker of thehouse. He introduced many vital bills, heading the often contentious factionsduring his tenure. His most notableachievements were the Articles of Confederation and the American alliance withFrance. It is as president of Congress that we meet Laurens in my novel, TheReluctant Spy.

Henry Laurens, President of the Continental CongressPresident of Congress

Henry Laurens, President of the Continental CongressPresident of CongressThe South Carolina nativedisplayed the typical Southern aristocratic sense of honor. This, coupled witha scrupulous attention to detail and an uncompromising view of corruption,actual or perceived, rubbed many of his peers the wrong way. President Laurens was highlyrespected but never loved. He would take on anyone, including Robert Morris. The mighty Morris influenced many against Laurens when he pushed for aninvestigation into his actions as the financier of the American Revolution. Laurens's role in the corruption accusations against the American agent inParis, Silas Deane, also rankled many. By December 1778, Laurens had enough andresigned as president to be replaced by fellow Huguenot John Jay—the father ofAmerican counterintelligence.

Financier Robert Morris

A year later, Laurens went frombeing a controversial figure on the national scene to a controversial one on theinternational scene when he gave up his Congressional seat to serve as Americancommissioner to the Netherlands. However, the British intercepted his ship offthe coast of Newfoundland. The canny Laurens quickly dumped the trunk full ofofficial dispatches into the ocean, but the Royal Navy salvaged them. TheNetherlands' role in aiding America was exposed, giving London a casus belli.

Laurens was taken to London,charged with treason, and thrown into the Tower of London to rot withoutadequate food or medical care until December 1781, when he was exchanged for BritishGeneral Charles, Lord Cornwallis, who had been captured at Yorktown theprevious October.

The Tower of London

The Tower of London

But there was no rest for thesick and weary ex-prisoner. Upon release, he sailed to Amsterdam to finish hisbusiness with the Dutch. Then Congress directed Laurens to Paris, where hejoined Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and now former Congressional presidentJohn Jay in negotiating a peace treaty. He missed the final negotiation andofficial signing as he was sent back to London to address business matters, andwhen peace came, the two nations would turn back to trading. He remained inLondon as an ex officio representative until formal diplomatic relationswere established. One wonders how envoy Laurens felt engaging with his former jailers andtormentors—or how they felt dealing with the traitor and former prisoner!

Signing the Treaty of Paris

Up from the AshesBy 1784, John Laurens was back inSouth Carolina. But he returned to a state devastated by years of ruthlesswarfare and British occupation. His mansion in Charleston had been destroyed,and his businesses were likewise in ruins—he had lost the equivalent of manymillions of dollars in service to his country. He spent his remaining yearsrebuilding the family fortune, turning down public offices of all kinds. Heeven refused to represent South Carolina at the Constitutional Convention.

Charleston

Charleston

Laurens had his reasons. He was aging, and his health was not good. But the likely cause was the blow he suffered when he learned his son, Colonel John Laurens (a staunch opponent of slavery), had died of wounds sustained in a minor skirmish in 1782. So, the elder Laurens remained in his native state, rebuilding his holdings until his death on 8 December 1792.

Although tarnished by his deepinvolvement in the slave trade, the former militia leader, businessman, slavetrader, planter, politician, and statesman's contributions to the nation'sfounding were many—as were his sacrifices. He should be remembered for both butcelebrated for his dedicated service to his country.

November 30, 2024

Bold Breton

The American Revolution had morethan its share of bold warriors and badasses—tough men who, once committed toa Cause, remained undaunted and steadfast. This first patriot is unique amongthem as he fought for two causes, although he would only succeed with one. ArmandCharles Tuffin, Marquis , was a son of Brittany, that ocean-washed corner of France that shared its heritage with theBritons across the sea.

Young BloodBorn to a noble Breton family in1750, the Marquis went to Versailles at an early age and became an Ensign inthe elite Garde Francaise, the Horse Guards, and earned a reputationas impetuous and hot-tempered nobleman—this among a society of impetuous andhot-tempered noblemen. His exploits included wooing a notorious young actress(unsuccessfully) and dueling (successfully) with the comte de Bourbon-Besset, acousin of King Louis XVI, in 1775. The latter was, of course, over a woman andgot him cashiered in disgrace (the Code Duello was forbidden).

King Louis XVI A New Cause

King Louis XVI A New CauseHis opponent lived and the youngMarquis fled to an abbey in Brittany where he sought solace among the Trappistmonks. At one point he tried to poison himself. Talked out of it by friends, hedid the next best thing. He abandoned France for the American cause, which hehad admired from afar. His journey began in a tempest when his ship, Morris,was pursued by three British frigates. Armand and the other officers and menfought their way into Chesapeake Bay. Rather than provide a prize ship to theBritish, they ran Morris aground, torched the vessel, and fled inland. Afiery start for a firebrand. It was April 1777.

Chesapeake Flight

Chesapeake FlightA New Commission

Founder Robert Morris had penneda letter of recommendation to George Washington. The desperate nobleman trekkedon foot to Philadelphia to deliver it and other correspondence from France tothe Continental Congress. The Marquis deLa Rouërie was commissioned under the name Armand—the name he was known by tothe Americans. He soon came to General George Washington’s notice and wasauthorized to raise a corps of eighty riflemen who would function as rangers.Most of the contingent were Germans, and Armand led them in their first combat at Short Hills, New Jersey, in June 1777. Armand’s rangers took horrificcasualties, some thirty men, but boldly retrieved a captured cannon from theenemy. He was promoted to colonel for his exploits and proved his mettle afew months later at the Battle ofBrandywine, where he took some sixty Hessian infantry prisoners.

Armand's Germans captured Hessian Infantry

Armand's Germans captured Hessian InfantryRaising a Legion

His success granted him authorityto raise a legion—independent units with a mix of infantry and cavalry calledthe “Free and Independent Chasseurs.”. Chasseur was the French word forhunter—something similar to riflemen or rangers in French military parlance. Armandwas soon deploying his Chasseurs in guerilla warfare around New York City.

Armand's Legion

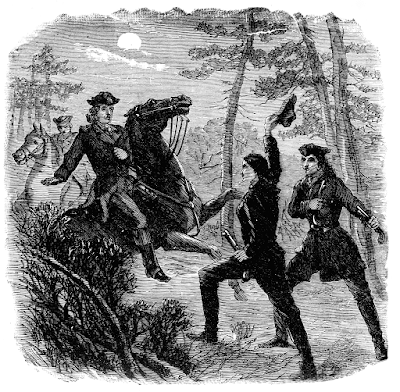

Armand's LegionNight Raid in New York

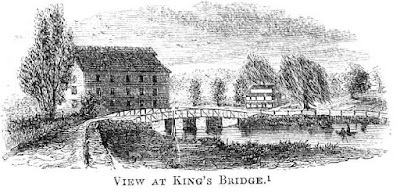

One of Colonel Armand’s mostsignificant exploits during this time was a daring night raid. His target, a notoriousLoyalist officer Major Bearmore. A member of Delancey’s brigade, Bearmore wasknown for his harsh treatment of Whigs in Westchester. Working his way throughWestchester and around the King’s Bridge, with 100 infantry and thirty horsemen,his “hunters” reached William’s Bridge undetected by a nearby regiment of Hessians.He left his infantry to provide security for their withdrawal and led twenty dragoons to Bearmore’s headquarters three miles south. At around nine o’clock, his men swept in, seizing Bearman and five others. Armand is said to have thrown Bearman’s six-foot frame across hissaddle and galloped off with him. The legion returned with no losses.

New Theater, New Command

Upon the death of Continentalcavalry commander General Count Casimir Pulaski at Savannah in October 1779, Armand’sChasseurs were transferred to the Southern Department and merged with the remnantsof Pulaski’s Legion aptly renamed Armand’s Legion. The year 1780 saw Armand’sLegion in action, notably at Camden, where he helped cover what he could of GeneralHoratio Gates’s Army when it routed.

Casimir Pulaski

Casimir Pulaski

Armand sailed back to France inearly 1781, where he received King Louis’s forgiveness and the Order of St.Louis. He used his time in France to support the Cause by raising funds andgathering supplies. Although brooding over the lack of promotion in the ContinentalArmy, he returned to America in time to partake in the final major campaignagainst the British.

Order of St. LouisThe Road to Yorktown

Order of St. LouisThe Road to YorktownWhile he was in France Armand’s Legion hadbeen sent north to Virginia where it was employed trying to check General (andtraitor) Benedict Arnold’s raids across the Old Dominion. Although whittleddown in number through battle losses and illness, Colonel Armand took commandof the Legion as it entered the siege works around General Charles Cornwallis’sArmy at Yorktown. Not wanting to be denied glory, he and a handful of his Legion joined Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton’s storming party at Redoubt Number 10. Armandwas the first officer to breach the parapet and helped force the defenders to surrender.Commended for his bravery, Congress finally promoted Armand to brigadiergeneral in 1782.

Storming Redoubt 10

Storming Redoubt 10Cavalry Commander

The war did not end for Armand withYorktown’s fall in October 1781. Instead, he rode south at the head of the newly named 1st Partisan Corps to assist GeneralNathanael Greene’s campaign to sweep the British from South Carolina andGeorgia. Forcing outposts into surrender and seizing towns and territory wascrucial as the British strategy in Paris to bargain for possession of what theyheld. To that end, they failed, although it took scores of small engagementsand lots of hard riding and marching to foil them.

Colonel ArmandLaurels at War’s End

Colonel ArmandLaurels at War’s EndArmand and his Legion were sentnorth and reached the New York area in December 1782. In March of the followingyear, Congress promoted the bold Breton to brigadier general. Brigadier GeneralArmand was also named chief of all the Continental Army’s cavalry—a title thatonce belonged to Casimir Pulaski. The two would share the honorific, “Father ofthe Cavalry.”

Continental Dragoon

Continental Dragoon

Brigadier General Armandreturned home a hero in 1784—not of the Lafayette caliber but highly celebrated. Settling back home in Brittany, he married a noblewoman (who gotill and died soon after) and threw himself into local politics—championing theliberties of his fellow Bretons. He joined several other Breton noblemen in a petitionof Breton grievances to the King in 1787. He turned down a military command to protest the loss of Breton liberties. This snub of the monarch got him tossedfrom the Army and into the Bastille, the notorious prison whose storming was one of the sparks of the violence that would come during the French Revolution.

Storming the Bastille

Storming the BastilleFrench Revolution

He was released from prison andlater attended the Estates General but soon became disenchanted as he saw even a revolutionary France as a threat to Breton rights. When France broke intorevolution and chaos. Armand tried to stay above the fray. Most of it concernedParis, not his home in Brittany. However, as the Jacobins seized power and began their excesses and repression, the Royalist and conservative Catholicwestern France rebelled against the rebellion. This area, known as the Vendee, stoodup the revolutionaries of Paris and their anti-Catholic policies. Armand formedthe Breton Association, which raised troops. When the Austrians and Prussians declared war on France in 1792, they were ready to join them with 10,000 men.

Vendee Resistance was Determined

Vendee Resistance was DeterminedDefiant Fugitive

But the French victory at Valmysent the Austrians and Prussians reeling, and the French central governmentturned on the Vendee. Armand went on the run when revolutionary dragoons raidedhis estate. He wandered Brittany accompanied by a few faithful companions for thenext year. One of his companions caught a fever, and it eventually spread to Armand, who died of pneumonia on 30 January 1793, right after reading of the executionof King Louis XVI by the revolutionary government.

Armand as Marquis de Rouërie in the Vendee

Armand as Marquis de Rouërie in the Vendee

October 30, 2024

The 2nd Duke

It has been some time since we have profiled a British Armyofficer, so I picked one whose understated but valuable contribution to theCrown, a chap with the very likely and straight-out-of-central casting name ofHugh Percy. Raised in a powerful family (his father was the First Earl ofNorthumberland), young Percy overcame a series of childhood maladies to enterinto a military career, a career he would himself essentially terminate just ashe reached the peak of success.

Hugh Percy

Hugh Percy

Percy joined the 24th Regiment of Foot in 1759 asan ensign. Like so many from prominent and connected families, young Hughmanaged to obtain a lieutenant colonelcy and position as aide de camp toFerdinand of Brunswick. Also, like so many of his peers, The Seven Years' Warprovided the opportunity to garnish laurels in combat at the battles of Bergenand Linden.

Battle of Minden

PoliticianBy 1762, he was a lieutenant colonel in the GrenadierGuards, arguably the most elite unit in the Royal Army and guardian of thesovereign. He stunned many when he declined to serve as aide de camp to KingGeorge III. Instead, he stood for Parliament, earning a seat in the House ofCommons as a Whig. His politics put him at odds with the Crown, particularlywhen it came to colonial policy. Ironically, Percy still maintained a tightconnection to the King. He married the daughter of George III's tutor and mentor,Lord Bute.

Percy as Politico

Percy as Politico

In 1768, Percy bought a colonelcy in the NorthumberlandFusiliers. He proved to be a very liberal and forward-thinking colonel. He tooka different approach to leadership, treating his men with kindness and rejectingthe traditional harsh discipline of the Army. He banned flogging and otherharsh disciplinary measures. Percy also saw to their financial needs and those oftheir families, often providing funds to those in need. Rather than lead byfiat, he led by example. His actions quickly won the affection and trust of hissoldiers. His approach resulted in a highly effective unit of men fiercelydevoted to their commanding officer.

Northumberland Fusilier

Northumberland FusilierBoston Bound

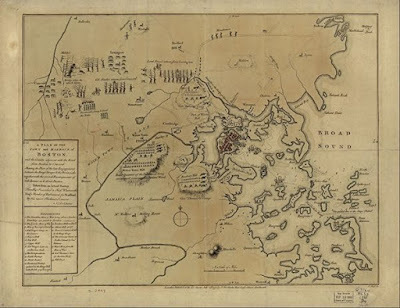

The political situation in North America continued todeteriorate over the next few years. Despite, or perhaps because of, hissympathies for the Americans, Colonel Hugh Percy received orders in 1774 tosail to America, where his regiment joined General Thomas Gage's garrison inBoston. Gage appointed him a brevet brigadier general and commandant of theBritish camp. Things continued to simmer in and around Boston, and in thefollowing year, Gage began a series of pre-emptive strikes—punitive actions toreduce the power and threat from the militia.

Boston and Environs

Boston and Environs

Things came to a head in April 1775 when Gage sentLieutenant Colonel Francis Smith at the head of a column of some 800 regularsto seize militia gunpowder and arms thought to be at Concord. On 19 April, oneof Smith's units, under the command of Major John Pitcairn, encountered amilitia unit on Lexington Green. The short exchange, the so-called "ShotHeard Round the World," was followed by a larger firefight aroundCambridge.

The Column Reaches ConcordColumn in Chaos

Things went badly for the British, who began a retreat toBoston as thousands of locals grabbed their muskets and began to harass thecolumn, cutting down many officers with aimed fire. Near Lexington, Smith'stroops were reinforced by a brigade of some 1,400 men under Hugh Percy. Percyused cannon and volley fire to keep the militia (by now, we can call themrebels) at bay and brought Smith's demoralized men into some sort of order.

Percy guides the column home

Percy guides the column home

Throughout the long march back, under relentless andpunishing fire from the rebel militia, Percy kept the British column together,maintaining discipline to prevent a disaster. When they reached Menotomy, Percymade a decision that likely saved the Army. Instead of pushing towardCambridge, he changed their route of return and marched to Charlestown. Thisroute had fewer rebels. The column arrived back in Boston. In July, Gagepromoted Percy to Major General for his cool actions under duress. No smallirony that an officer sympathetic to the rebels thwarted their best efforts to wipeout the column.

General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage

Percy missed the Battle of Bunker Hill due to illness. Tohis chagrin, his Northumberland Fusiliers were cut to pieces under theheavy-handed command of General William Howe. True to his philosophy of command,Percy funded the return voyage of all the widows and arranged a small stipendfor those in need. The British evacuated Boston in March 1776 and recuperated in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Gagehad been recalled, and William Howe was now commander in chief.

Battles for New York

In July, the reinforced British Army landed on Staten Islandin New York harbor. Weeks later, a whirlwind campaign was launched on LongIsland. Here, on 27 August, Percy distinguished himself by helping lead a nightmarch that cut off a third of the Continental Army. In November, Percy led aBritish force that drew fire from the defenders at Fort Washington, allowingHessian General von Knyphausen's men to overrun the garrison and force itssurrender.

Percy led regulars in action on Long Island

Percy led regulars in action on Long Island

The following month, Percy and General Henry Clinton led aBritish expedition that seized Newport, Rhode Island. When Henry Clintonreturned to Britain, Percy was made commander of the Newport garrison. Thingswere not all rosy, however. Percy was critical of Howe's strategy and hisconduct of the war. He also suffered from ill health. This combination caused himto request relief from his command and a return to Britain. General Howepromptly granted it, and Hugh Percy left America forever in May 1777.

Sir Henry Clinton

Sir Henry ClintonThe 2nd Duke

In 1779, Percy divorced his wife on the grounds of adultery but soon remarried and had nine children with his second wife. Upon the death of his father in 1784, Percy became the 2nd Duke ofNorthumberland. He spent the next several decades in various military postingsin Britain, dabbling again in politics and tending to his estates. He was abenevolent landlord who took care of the farm folk who worked on his lands. Hewas a rare lord who had the esteem of his people. Hugh Percy died on his estatein July 1817. His years of poor health finally caught up with him.

2nd Duke of Northumberland

Liberal LegacyOne has to wonder how the course of the war in America wouldhave gone for the British had Percy remained, possibly even rising to supremecommand. His benign ways might have rallied more Americans to the Crown, andhis ability to inspire troops and his coolness under fire might have been thedifference in the campaigns that followed. One interesting nugget—Percy had an illegitimatehalf-brother, James Smithson. The same James Smithson who bequeathed the fundsused to establish what became known as The Smithsonian Institution—the world'slargest museum and research complex.

The Smithsonian

The SmithsonianSeptember 30, 2024

Loyalist on Two Continents

Time to take another look into the experiences of those forgotten participants (along with the Indians and slaves ) of the American War for Independence—the Loyalists. The story of young Alexander Chesney is, in some ways, very typical of the experience of these British subjects who did not buy into the dream of independence and liberty. We will delve into his Revolutionary War escapades and take a peek at his post-war challenges—and challenges he had.

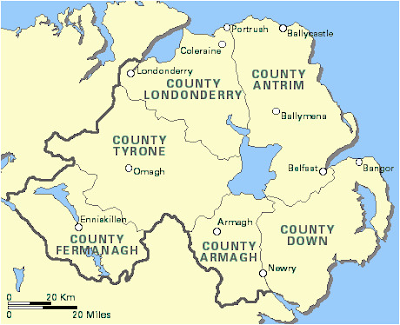

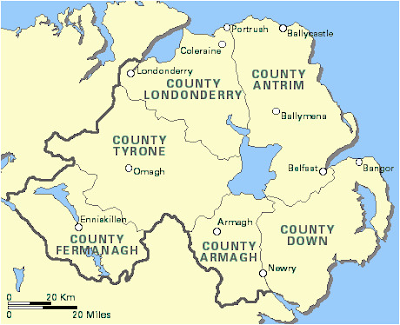

From Antrim to AmericaThe fourteen-year-old Alexander emigrated with his parents from County Antrim to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1772. By then, the colonists' dispute with the Crown was in full swing, so the Scots-Irish family had placed themselves in a land that would soon be torn asunder by insurrection and rebellion, which for them would also become a civil war.

He married Margaret Hodges around the time of the "Shot Heard Round the World—a marriage to be marked by hardship and sacrifice.

Tory GuideIn the early years of the war, the Carolinas remained firmly under patriot control, although many remained loyal, either openly or silently. These Loyalists were deemed a threat and were ruthlessly suppressed and oppressed. Young Chesney threw his hat in the ring and began helping loyalists, guiding them to safety through a maze of patriot militias.

FugitiveEventually, his actions made him a target, and patriot militia Colonel Richard Richardson's men apprehended him in the spring of 1776. The militia ransacked his home and imprisoned him in Snowy Camp on the Reedy River in northwestern South Carolina. Richardson made him an offer he couldn't refuse: stand trial for assisting Loyalists and likely hang or join the patriot militia.

Richard Richardson

Richard RichardsonYankee Doodle Days

The young Chesney enlisted as a private and spent the next few years marching with the hated Yankee Doodles. Why? Seems his father, Robert, was imprisoned as a suspected Tory. The younger Chesney's service helped to keep him alive. Private Chesney served in campaigns against the Creek and Cherokee. Between these expeditions, he was a teamster bringing produce to Charleston, South Carolina, which was then in the possession of the patriots.

Militia Campaigns Against Creeks and Cherokees

Militia Campaigns Against Creeks and Cherokees

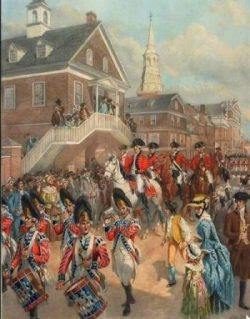

Things changed in May 1780 when the British returned (they had been repulsed in 1776) to Charleston and soon overran the state. When the British commander in chief, General Henry Clinton, issued his proclamation calling all loyal subjects to arms, Chesny came out of the patriot closet and joined one of the militia units raised by the renowned "counter guerilla," Major Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson's regiments racked up a string of victories in the bitter in-country fighting between Loyalist and patriot rebels.

Fall of Charleston

Fall of CharlestonChesney rose from lieutenant to captain over the next few months. But his fortunes took a turn for the worse in early October of that year. Ferguson, hot on the trail of patriots and hot to recruit new men for the Crown, marched his brigade away from General Cornwallis's main body and managed to get surrounded by a corps of back-country militia—some of the most experienced frontier Indian fighters and angry for revenge against Ferguson, who had threatened to hang them all.

Parick Ferguson

Parick Ferguson

Ferguson made his stand on a piece of wooded high ground called King's Mountain. The "Over Mountain Men," led by a bunch of tough hombres that included such legends as colonels John Sevier, Benjamin Cleveland, and Isaac Shelby, quickly encircled the Loyalists and started up the hill. The battle saw lead slam into tree trunks, leafy branches, and the hapless Tories as the rebel militia came at them firing, Indian-style, from tree to tree. Loyalists dropped like turkeys under unrelenting fire. Ferguson fell mortally wounded trying to rally his men.

Over Mountain Attack on King's Mountain

Over Mountain Attack on King's Mountain

Captain Alexander Cheney was also wounded and taken prisoner along with some 668 others. The Loyalists also suffered 290 killed and 163 wounded. According to his account, Chesney later watched as the prisoners underwent a mock trial, with many sentenced to death. One of the American commanders, Colonel Benjamin Cleveland, offered him parole if he provided them with Ferguson's battle tactics. But the tough Irishman would not betray his cause.

Colonel Cleveland Leading Prisoners

Colonel Cleveland Leading Prisoners

With shoes taken and without coats to protect against the worsening weather, he and the others marched off into captivity under brutal conditions and threats of beating and shooting through the rugged hills toward the Yadkin River and prison in Salem, North Carolina. Chesney escaped along the way and hid in a nearby cave but was later captured and held until released in a prisoner exchange.

Joining the LegionHe soon joined the only Loyalist unit with an even more terrible reputation among the rebels—Tarleton's Legion! He raised a mounted Loyalist company and served Colonel Banastre Tarleton as a guide, helping the Legion negotiate the back roads and woods as they marched from Fort Ninety-Six in a search and destroy mission. Their prey—famed rifleman Daniel Morgan and his Army.

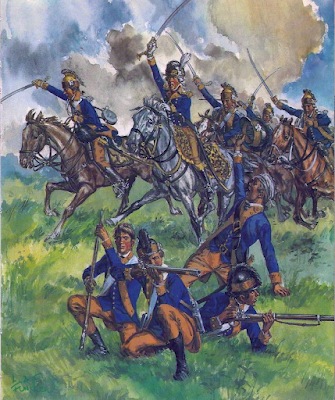

Tarleton's Legion in Action

Tarleton's Legion in Action

Ironically, Morgan's forces occupied Chesney's farm at Grindal Shoals just days before Tarleton caught him at a place called the Cow Pens in January 1781. There, the reckless Tarleton launched headlong against his prey. After all, just a few lines of militia blocked the way.

Witness to a DebacleBut Morgan was ready, with stout lines of Continentals behind the militia and dragoons hidden from sight. In one of the most impressive showings of the war, Tarleton's elite force was stopped cold, then cut off and crushed. Chesney led his men in the battle and managed to flee to the safety of the British garrison in Charleston. Tarleton escaped, but his Legion suffered over 80% casualties.

American Dragoons at Cow Pens

American Dragoons at Cow PensEmbittered by what he viewed as poor management at Cowpens, he moved his family from his despoiled farm to the protection of the British near Charleston and tried to reestablish a small plantation, which included some slaves.

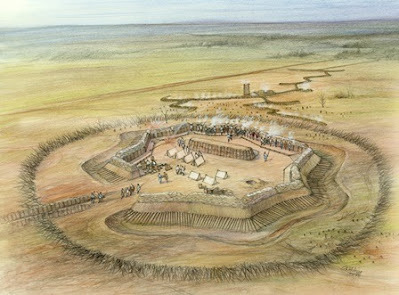

Guiding Lord RawdonBut with war raging through South Carolina, Chesney soon took the field at the head of various Loyalist units. He operated along the Edisto River, often skirmishing with the hated rebels. His mounted company scouted for Lord Rawdon as he fought the last engagements in the state. Chesney was wounded again during a skirmish near the critical outpost at Fort Ninety-Six.

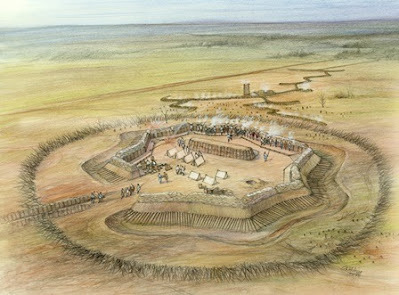

Fort Ninety-Six

Fort Ninety-Six Crumbling Fortunes

October 1781 brought General Charles Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, serious negotiations in Paris, and what were likely bitter months for the Ulsterman.

Yorktown Surrender

Yorktown Surrender

Presumably not fit for the field, he was appointed Superintendent of Woodcutting to support Charleston's fuel needs, as it was the last rebel bastion. He hired displaced Loyalists and did what he could, but the Americans were closing in. Things got even worse when his wife Margaret died in December 1781. The new year proved no better. Chesney became sick and could not care for his son William, so he had to send the lad to live with relatives. His farm was destroyed, and as a veteran of two of the most feared and hated Brtissh contingents, he would get little quarter.

Charleston Harbor

Charleston Harbor

Once the British Army left America, he would face a grim future. Although the last British soldier left the former colonies in December, Chesney decided to return to Ireland, arriving in Castle Haven in May of 1782.

Loyalist Recompense?Normally, this would end the tale of Alexander Chesney. But in a sense, his life had only just begun despite the darkness of defeat and loss. Over the next several decades, he fought hard to rebuild his life. He went to England, where he sought to make his claim to the British government, and became a leader among the Loyalists there. He met with other key members of the Association of American Loyalists in London., where a petition was drawn for just compensation for their service to the Crown and the loss of property and land.

As with most of the Loyalist refugees, things came hard. Reaching out to former commanders such as Cornwallis and Rawdon did not help get through the British bureaucracy. While waiting on his claim, the doughty Chesney struck in a different direction. He sought and received an appointment as an Irish Customs Officer, specifically a coastal inspector.

Lord Francis Rawdon

Lord Francis Rawdon

Despite numerous petitions and a few trips back and forth across the Irish Sea, he was disappointed. His final compensation amounted to less than a quarter of his claim. What is the price of Loyalty? Undaunted, he went to work as a Coast Officer, chasing down smugglers along the northern coast of Ireland. He was highly effective at this.

Another RebellionBut in the late 1790s, Ireland broke out in its rebellion, with the Irish patriots hoping to capitalize on events in France.

United Irishman Hanged

United Irishman HangedBy the autumn of 1796, the Association of United Irishmen in County Down and several neighboring counties were prepping for revolt. Possibly drawing on his American experience, Chesney got wind of this. He got a captain's commission and formed the Mourne Infantry in early 1797. His Irish Yeomanry company was the first formed in County Down. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, none other than General Charles Cornwallis, put down the rebellion and crushed the French invasion in 1798, ending the so-called "Year of the French."

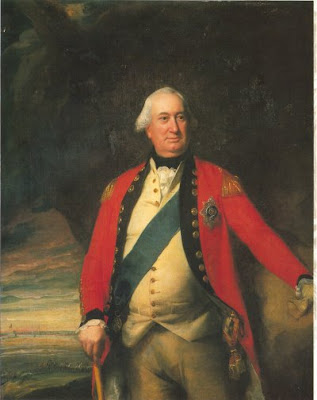

:Lord Cornwallis

:Lord CornwallisCustoms ServiceChesney's work as a customs official kept him busy. The Napoleonic Wars saw much illegal trade, and Chesney was on the move—suppressing smugglers and illegal shippers seeking to profit from the war. Along the way, he started another family and had several children. Two of his sons later received commissions in the Army, and his surviving daughter had a successful marriage to a clergyman.

Chesney vs. Smugglers

Chesney vs. SmugglersLetter from America

In February 1818, a great shock came. Chesney received a letter from his eldest son, William, whom he had left with relatives in America. The stunned Chesney thought he had died! But William Chesney was alive and in Tennessee. However, his son was not well off. William revealed that Chesney's father, Robert, was also alive. Chesney did not offer to bring him to Ireland. They were never reunited.

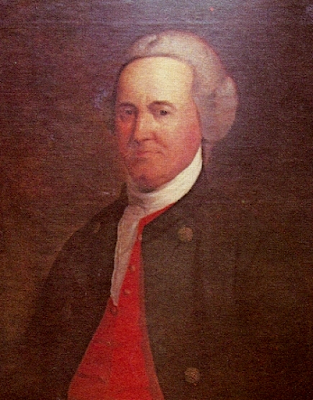

Alexander Chesney

Alexander ChesneyLife and Legacy

Chesney penned a journal of his Revolutionary War exploits, documenting the savage combat in the Carolinas. The Ulsterman spared no one in his account. But, of course, through decades of struggle, he never really spared himself. Against all odds, and as a testament to his basic toughness, this Loyalist on two continents, the survivor of two pitched battles and numerous skirmishes, imprisonment, and deprivations, lived to the ripe old age of 83, dying on 12 January 1843.

Chesney Grave

Loyalist and Irish Yeomanry leader Captain Alexander Chesney is buried in the Mourne Presbyterian Churchyard in Kilkeel, County Down, Northern Ireland.

A Loyalist on Two Continents

Time to take another look into the experiences of those forgotten participants (along with the Indians and slaves ) of the American War for Independence—the Loyalists. The story of young Alexander Chesney is, in some ways, very typical of the experience of these British subjects who did not buy into the dream of independence and liberty. We will delve into his Revolutionary War escapades and take a peek at his post-war challenges—and challenges he had.

From Antrim to AmericaThe fourteen-year-old Alexander emigrated with his parents from County Antrim to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1772. By then, the colonists' dispute with the Crown was in full swing, so the Scots-Irish family had placed themselves in a land that would soon be torn asunder by insurrection and rebellion, which for them would also become a civil war.

He married Margaret Hodges around the time of the "Shot Heard Round the World—a marriage to be marked by hardship and sacrifice.

Tory GuideIn the early years of the war, the Carolinas remained firmly under patriot control, although many remained loyal, either openly or silently. These Loyalists were deemed a threat and were ruthlessly suppressed and oppressed. Young Chesney threw his hat in the ring and began helping loyalists, guiding them to safety through a maze of patriot militias.

FugitiveEventually, his actions made him a target, and patriot militia Colonel Richard Richardson's men apprehended him in the spring of 1776. The militia ransacked his home and imprisoned him in Snowy Camp on the Reedy River in northwestern South Carolina. Richardson made him an offer he couldn't refuse: stand trial for assisting Loyalists and likely hang or join the patriot militia.

Richard Richardson

Richard RichardsonYankee Doodle Days

The young Chesney enlisted as a private and spent the next few years marching with the hated Yankee Doodles. Why? Seems his father, Robert, was imprisoned as a suspected Tory. The younger Chesney's service helped to keep him alive. Private Chesney served in campaigns against the Creek and Cherokee. Between these expeditions, he was a teamster bringing produce to Charleston, South Carolina, which was then in the possession of the patriots.

Militia Campaigns Against Creeks and Cherokees

Militia Campaigns Against Creeks and Cherokees

Things changed in May 1780 when the British returned (they had been repulsed in 1776) to Charleston and soon overran the state. When the British commander in chief, General Henry Clinton, issued his proclamation calling all loyal subjects to arms, Chesny came out of the patriot closet and joined one of the militia units raised by the renowned "counter guerilla," Major Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson's regiments racked up a string of victories in the bitter in-country fighting between Loyalist and patriot rebels.

Fall of Charleston

Fall of CharlestonChesney rose from lieutenant to captain over the next few months. But his fortunes took a turn for the worse in early October of that year. Ferguson, hot on the trail of patriots and hot to recruit new men for the Crown, marched his brigade away from General Cornwallis's main body and managed to get surrounded by a corps of back-country militia—some of the most experienced frontier Indian fighters and angry for revenge against Ferguson, who had threatened to hang them all.

Parick Ferguson

Parick Ferguson

Ferguson made his stand on a piece of wooded high ground called King's Mountain. The "Over Mountain Men," led by a bunch of tough hombres that included such legends as colonels John Sevier, Benjamin Cleveland, and Isaac Shelby, quickly encircled the Loyalists and started up the hill. The battle saw lead slam into tree trunks, leafy branches, and the hapless Tories as the rebel militia came at them firing, Indian-style, from tree to tree. Loyalists dropped like turkeys under unrelenting fire. Ferguson fell mortally wounded trying to rally his men.

Over Mountain Attack on King's Mountain

Over Mountain Attack on King's Mountain

Captain Alexander Cheney was also wounded and taken prisoner along with some 668 others. The Loyalists also suffered 290 killed and 163 wounded. According to his account, Chesney later watched as the prisoners underwent a mock trial, with many sentenced to death. One of the American commanders, Colonel Benjamin Cleveland, offered him parole if he provided them with Ferguson's battle tactics. But the tough Irishman would not betray his cause.

Colonel Cleveland Leading Prisoners

Colonel Cleveland Leading Prisoners

With shoes taken and without coats to protect against the worsening weather, he and the others marched off into captivity under brutal conditions and threats of beating and shooting through the rugged hills toward the Yadkin River and prison in Salem, North Carolina. Chesney escaped along the way and hid in a nearby cave but was later captured and held until released in a prisoner exchange.

Joining the LegionHe soon joined the only Loyalist unit with an even more terrible reputation among the rebels—Tarleton's Legion! He raised a mounted Loyalist company and served Colonel Banastre Tarleton as a guide, helping the Legion negotiate the back roads and woods as they marched from Fort Ninety-Six in a search and destroy mission. Their prey—famed rifleman Daniel Morgan and his Army.

Tarleton's Legion in Action

Tarleton's Legion in Action

Ironically, Morgan's forces occupied Chesney's farm at Grindal Shoals just days before Tarleton caught him at a place called the Cow Pens in January 1781. There, the reckless Tarleton launched headlong against his prey. After all, just a few lines of militia blocked the way.

Witness to a DebacleBut Morgan was ready, with stout lines of Continentals behind the militia and dragoons hidden from sight. In one of the most impressive showings of the war, Tarleton's elite force was stopped cold, then cut off and crushed. Chesney led his men in the battle and managed to flee to the safety of the British garrison in Charleston. Tarleton escaped, but his Legion suffered over 80% casualties.

American Dragoons at Cow Pens

American Dragoons at Cow PensEmbittered by what he viewed as poor management at Cowpens, he moved his family from his despoiled farm to the protection of the British near Charleston and tried to reestablish a small plantation, which included some slaves.

Guiding Lord RawdonBut with war raging through South Carolina, Chesney soon took the field at the head of various Loyalist units. He operated along the Edisto River, often skirmishing with the hated rebels. His mounted company scouted for Lord Rawdon as he fought the last engagements in the state. Chesney was wounded again during a skirmish near the critical outpost at Fort Ninety-Six.

Fort Ninety-Six

Fort Ninety-Six Crumbling Fortunes

October 1781 brought General Charles Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, serious negotiations in Paris, and what were likely bitter months for the Ulsterman.

Yorktown Surrender

Yorktown Surrender

Presumably not fit for the field, he was appointed Superintendent of Woodcutting to support Charleston's fuel needs, as it was the last rebel bastion. He hired displaced Loyalists and did what he could, but the Americans were closing in. Things got even worse when his wife Margaret died in December 1781. The new year proved no better. Chesney became sick and could not care for his son William, so he had to send the lad to live with relatives. His farm was destroyed, and as a veteran of two of the most feared and hated Brtissh contingents, he would get little quarter.

Charleston Harbor

Charleston Harbor

Once the British Army left America, he would face a grim future. Although the last British soldier left the former colonies in December, Chesney decided to return to Ireland, arriving in Castle Haven in May of 1782.

Loyalist Recompense?Normally, this would end the tale of Alexander Chesney. But in a sense, his life had only just begun despite the darkness of defeat and loss. Over the next several decades, he fought hard to rebuild his life. He went to England, where he sought to make his claim to the British government, and became a leader among the Loyalists there. He met with other key members of the Association of American Loyalists in London., where a petition was drawn for just compensation for their service to the Crown and the loss of property and land.

As with most of the Loyalist refugees, things came hard. Reaching out to former commanders such as Cornwallis and Rawdon did not help get through the British bureaucracy. While waiting on his claim, the doughty Chesney struck in a different direction. He sought and received an appointment as an Irish Customs Officer, specifically a coastal inspector.

Lord Francis Rawdon

Lord Francis Rawdon

Despite numerous petitions and a few trips back and forth across the Irish Sea, he was disappointed. His final compensation amounted to less than a quarter of his claim. What is the price of Loyalty? Undaunted, he went to work as a Coast Officer, chasing down smugglers along the northern coast of Ireland. He was highly effective at this.

Another RebellionBut in the late 1790s, Ireland broke out in its rebellion, with the Irish patriots hoping to capitalize on events in France.

United Irishman Hanged

United Irishman HangedBy the autumn of 1796, the Association of United Irishmen in County Down and several neighboring counties were prepping for revolt. Possibly drawing on his American experience, Chesney got wind of this. He got a captain's commission and formed the Mourne Infantry in early 1797. His Irish Yeomanry company was the first formed in County Down. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, none other than General Charles Cornwallis, put down the rebellion and crushed the French invasion in 1798, ending the so-called "Year of the French."

:Lord Cornwallis

:Lord CornwallisCustoms ServiceChesney's work as a customs official kept him busy. The Napoleonic Wars saw much illegal trade, and Chesney was on the move—suppressing smugglers and illegal shippers seeking to profit from the war. Along the way, he started another family and had several children. Two of his sons later received commissions in the Army, and his surviving daughter had a successful marriage to a clergyman.

Chesney vs. Smugglers

Chesney vs. SmugglersLetter from America

In February 1818, a great shock came. Chesney received a letter from his eldest son, William, whom he had left with relatives in America. The stunned Chesney thought he had died! But William Chesney was alive and in Tennessee. However, his son was not well off. William revealed that Chesney's father, Robert, was also alive. Chesney did not offer to bring him to Ireland. They were never reunited.

Alexander Chesney

Alexander ChesneyLife and Legacy

Chesney penned a journal of his Revolutionary War exploits, documenting the savage combat in the Carolinas. The Ulsterman spared no one in his account. But, of course, through decades of struggle, he never really spared himself. Against all odds, and as a testament to his basic toughness, this Loyalist on two continents, the survivor of two pitched battles and numerous skirmishes, imprisonment, and deprivations, lived to the ripe old age of 83, dying on 12 January 1843.

Chesney Grave

Loyalist and Irish Yeomanry leader Captain Alexander Chesney is buried in the Mourne Presbyterian Churchyard in Kilkeel, County Down, Northern Ireland.

August 30, 2024

Tradesman Spy

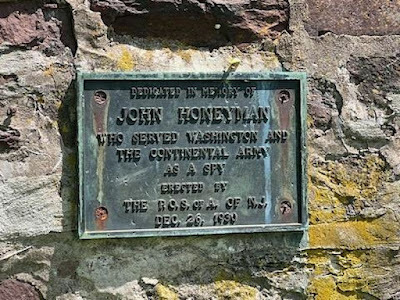

Patriotic Sons of the American Revolution marker near Trenton, New Jersey

Patriotic Sons of the American Revolution marker near Trenton, New Jersey

Fort Lee, New Jersey, November 1776. The tall soldier in ablue jacket opened the door. "Your visitor is here, Your Excellency."

General George Washington wiped the dark liquid from his pentip and nodded. A nondescript man in farmer clothes stepped in. Washingtonmotioned toward a seat. "Thank you for coming, sir. I hope the journey didnot discommode you."

"Not at all, sir. When we last met I gave you my word thatI was at your service."

"Your nation thanks you for it. Our situation is bleak.The British regulars will be here within forty-eight hours. But the Army is tooweak to make another stand."

"What will you do, Your Excellency?"

"Better you not know. Suffice it to say this state willbe under British occupation for some time. That's where you come in."

"Me?"

Washington nodded. "I must trouble you to proceed toTrenton and its environs. Establish yourself there as a Loyal Tory. You are ahero of the last war—service under the great General Wolfe."

"He was a great man. As are you, Your Excellency. Now,what are your orders?"

"I need a spy in their midst."

The Spy?

Washington's visitor was one of the most enigmatic figuresin the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies. An Irishman born in Scotland, JohnHoneyman became a key agent when the American cause was at its lowest. Hischameleon ways, hiding in plain sight, may have inspired the protagonist HarveyBirch in James Fenimore Cooper's seminal work, The Spy, although mostconnect New Yorker Enoch Crosby to that role.

James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper

Historians clash over Honeyman's role as his narrative waswritten in the following century by a grandchild. But this is the fate of manysecret soldiers whose deeds, for reasons of secrecy and security, wentundocumented. Retired CIA Case Officer and Revolutionary War Historian KennethDaigler built a case for Honeyman's being one of Washington's operatives.

Honeyman hailed from County Armagh, born to thrifty Scottishparents. Although his father was a hardscrabble farmer who could afford littleeducation, Honeyman managed to learn to read and write. He had a knack fortrades, such as weaving. But at age twenty-nine, Honeyman went in a differentdirection, joining the British Army and sailing to America to fight the Frenchand Indians.

Honorable Service

At sea, he came to the attention of General Wolfe and becamehis servant and bodyguard. Action at Louisburg greeted him, but his militarycareer ended tragically. Private Honeyman was at the side of Wolfe when thebold general was struck down in his moment of triumph on the Plains of Abrahamoutside Quebec.

Death of Wolfe at Quebec

Death of Wolfe at Quebec

His officer gone, Honeyman mustered out a sort of hero witha letter vouching for his service with and for Wolfe, who became a belovedfigure among all Britons, especially those in America.

Tradesman and Family Man

Honeyman made his way to Pennsylvania, where he set himselfup as a butcher and weaver and married a girl from Ireland named Mary Henry inSeptember 1764. Around the time of Shot Heard Round the World, Honeyman hadmoved to Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress and a hotbed ofpolitical discussion and intrigue. Around that time, he may have come to theattention of George Washington. Some accounts say he offered the soon-to-becommander-in-chief his services.

A Spy Among Them

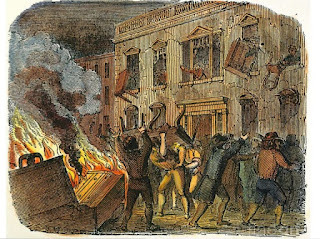

Honeyman left Fort Lee and arrived at Trenton. He had littletrouble falling in among the local Tories—his letter from the late Wolfe anddischarge made him a respected Briton and servant of the King. He set up hisbutcher and weaving enterprises with the British and soon came to theirattention as a Loyal Briton. His home was behind rebel lines at Griggstown,and John Honeyman avowed Tory (as part of Washington's scheme) traveled backand forth in trade while collecting intelligence. Sometimes, plans can work toowell. With tensions high that fateful year in the Jerseys, a patriot mob attackedhis home. His family escaped unharmed, although it took a note from Washingtonto allow the Tory family safe passage to Trenton, now garrisoned by ColonelJohann Rall's brigade of Hessians.

Violence was not confined to the battlefield

Violence was not confined to the battlefield

Great Scheme Hits Paydirt

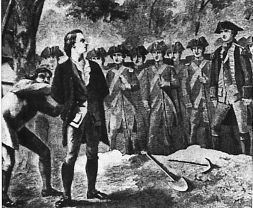

Using Trenton as his base for business and espionage, Honeymanwas able to collect intelligence on the garrison's strength, morale, defenses,and other activities. A plan was concocted to give him cover—Honeyman allowedhimself to be captured by a rebel patrol that had orders to take him to Washington'sheadquarters.

Washington meeting a spy

Washington meeting a spy

The commander in chief personally "interrogated" the"prisoner." Afterward, he ordered the notorious Tory to be throwninto a jail cell. Washington arranged a diversionary fire that allowed the Toryto escape. The skilled line crosser made his way past guards and sentries fromboth sides and reached the safety of Trenton. There, the loyal Tory dutifully reportedhis capture and escape. Under Johann Rall's questioning, he was able to plant asignificant piece of disinformation—the rebels were in such a low state ofmorale and equipment the Hessian commander did not need to fear an attack.

Johann Rall

Johann Rall

Deception Brings Defeat

Even though the Hessians had been on heightened alert forthe past two weeks, Rall believed Honeyman's story and so felt confident enoughto relax security on the nights of 25-26 December. The deception gave Washington just enoughof an edge—his Army recrossed the Delaware River and marched through the snowynight to surprise the garrison, which soon surrendered. His victory saved thecause from inevitable collapse and perhaps turned the tide of the war.

Attack on Trenton

Attack on Trenton

The Spy Who Stayed Out in the Cold