S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 3

June 30, 2024

Young Hickory at War

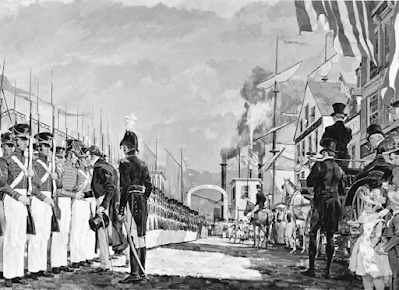

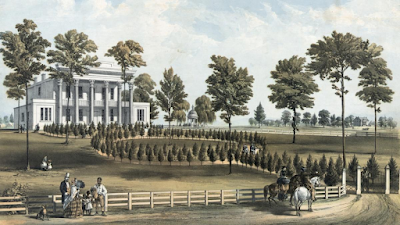

A key event in my historical novel, The Lafayette Circle, is General Lafayette’s visit to The Hermitage plantation home of the War of 1812 and Seminole War leader Andrew Jackson. On 25 May 1825, Jackson meets Lafayette and his entourage at their steamer and escorts them on a tour of his home. While there, Jackson brings out an exquisite pair of matched pistols.

The Hermitage

The Hermitage

“Do you recognize these, sir?”

“Indeed, sir.” Lafayette choked up and warmly embraced his host.

Lafayette had given the two “saddle pistols” to Washington in 1778—during the middle of the American War for Independence.

When Washington died in 1799, his nephew inherited them and later gifted them to William Robinson, who further gifted them to the Indian Wars and War of 1812 hero—Old Hickory.

Washington's Pistols

Washington's Pistols

Young Hickory

Andrew Jackson and his two older brothers grew up on a hard-scrabble piece of land in the Waxhaws region, nestled along the border of the two Carolinas. The family was of the flinty Scots-Irish stock who provided many of the early settlers carving out a living in the New World—stubborn, resourceful, resilient, fearless, and defiant. Sadly, Jackson’s father, Andrew Senior, was killed while felling a tree just three weeks before Andrew’s birth—his mother and two older siblings raised him.

Frontier Farmers

Frontier Farmers

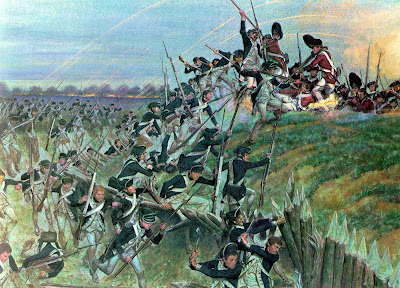

War prodded the Carolinas at first—attempts at naval invasion by the British were thwarted until Savannah fell, opening a southern land and sea approach to Charleston. Militias and Continental troops under American General Benjamin Lincoln resisted a prodding by forces under British General John Maitland in the summer of 1779. And it was during the British rear-guard action at Stono Ferry on 20 June that Andrews’s older brother Hugh, gravely wounded, succumbed to the oppressive heat and died of exhaustion.

Stono Ferry

Stono Ferry

However, within a year, a massive British Army led by Sir Henry Clinton had taken Charleston, and Clinton unleashed General Charles Cornwallis and notorious Colonel Banastre Tarleton to subdue the rest of the state. War was coming to the Waxhaws.

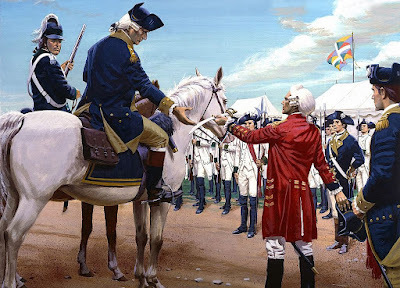

Defiant, the two younger Jacksons joined Colonel William Richardson Davie's regiment, and they served as couriers. As such, they took part in the short but bloody clash against a British outpost at Hanging Rock on the Catawba River on 6 August 1780. Davie made a diversionary attack there, supporting General Thomas Sumter’s larger attack on Rocky Mount, just to the west Davie’s initial assault failed, but Sumter shifted his efforts and launched a more significant attack with several regiments.

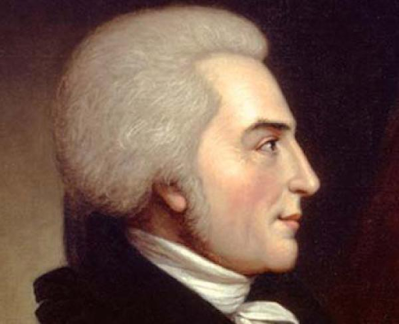

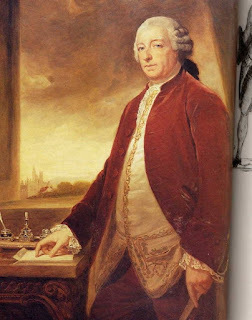

Colonel William Richardson Davie

Colonel William Richardson Davie

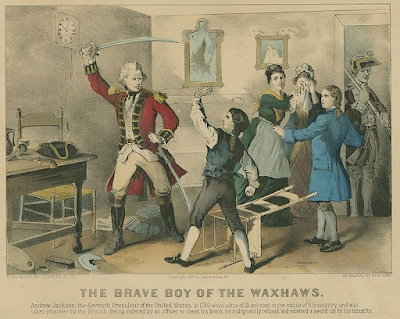

Waxhaws

Waxhaws

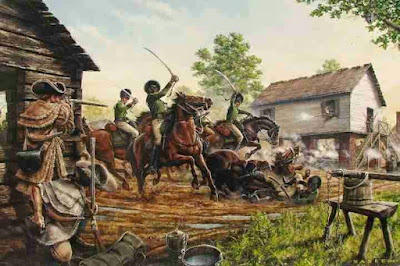

But a year later, 14-year-old Andy and his 15-year-old brother, Robert, were on the run after their unit was surprised and scattered by Tory war parties who joined with the British to stamp out any vestige of resistance. Over a third of their comrades were caught up in the net, but the Jacksons aimed to avoid that fate.

Militia fleeing the British

Militia fleeing the British

However, hunger dictated otherwise. After hiding their horses and weapons in the woods, the boys approached a friendly farmstead, the home of patriot Lieutenant Crawford. Local Tories spotted the horses and warned the British. While supper was on the stove, a party of British soldiers surrounded the Crawford farm and rushed the house.

They searched the house with a fury only imaginable of a violent civil war. Clothes torn from dressers are torn to shreds, furniture is chopped up, and pots and dishes are smashed. Oaths and threats filled the air.

British tore up the Crawford House

British tore up the Crawford HouseBritish commander stomped across the room and accosted younger Jackson. He pointed to his mud-spattered riding boots. “Boy! Clean my boots!”

Andrew straightened and lifted his chin in defiance. “Sir, I am a prisoner of war and should be so treated.”

Defying the Dragoon

Defying the Dragoon

Enraged, the dragoon officer drew his sword and struck a slashing blow that cut the young teenager’s upraised wrist to the bone and slid off the bone, striking his forehead. It would leave a scar that he carried for life. It left an even deeper scar on Andrew’s mind, an indelible hatred of everything British, which was to become one of the leading motivations of his life.

The officer turned on Robert. “Then you clean my boots!"

When he defiantly refused to obey, the blade came down, striking him on the head and sending streams of blood down his face.

The boys, badly wounded and bleeding, were force-marched in oppressive heat to a prison camp at Camden, where they joined some 250 other captured rebels. They were left untreated, given little food, and suffered cramped quarters. Then, disease struck as it usually did in filthy prisons. Andre had to listen to the heart-wrenching moans of men suffering from smallpox. Eventually, the affliction struck Robert. Andy, too, was lying in bed, suffering malnutrition that was sapping his life from him.

During a prisoner exchange, the boys’ mother, Elizabeth, arrived in Camden. She argued for the release of the two sons. As the two appeared near death, her request was granted. With Robert struggling on the one horse, Andrew suffered the forty-five-mile trek home to Waxhaws.

Elizabeth Jackson Monument

Elizabeth Jackson Monument

Back home, Elizabeth struggled to get her boys healthy again, but Robert died within days. Despondent, she worked hard to nurture Andy, and he slowly recovered. His combatant days were over—in this war. Elizabeth and other women began nursing other prisoners and traveled to Charleston to treat those afflicted on prison ships in the harbor. Surrounded by disease, she caught cholera and died just before Charles Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown.

Andy’s wound healed, leaving him a scar across his brow. The cut across his forehead left an even deeper scar on Andrew’s mind, his hatred for all things British. It was also a living memorial to his family, who gave so much to the cause, as well as to the soldiers who suffered and died.

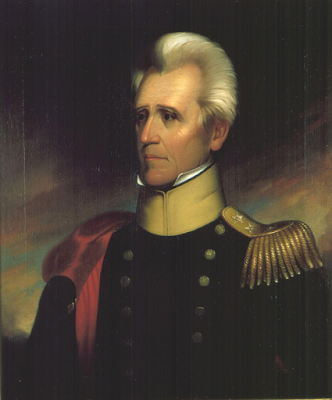

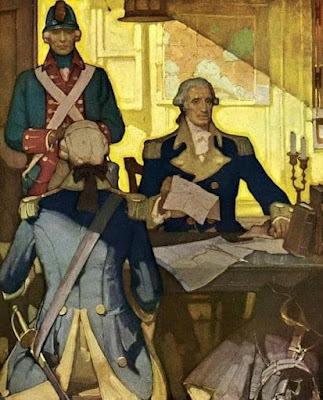

General Andrew Jackson

General Andrew JacksonThe feisty teen Andy Jackson would grow into Andrew Jackson—a man of action who would lead American soldiers to victory over the Creek Indians, the Spanish, and, of course, the British. He would secure large swathes of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi and smash lines of hated redcoats in the Battle of New Orleans, a victory that marked the United States as a nation that could not be ignored.

May 29, 2024

The Enslaved Spy

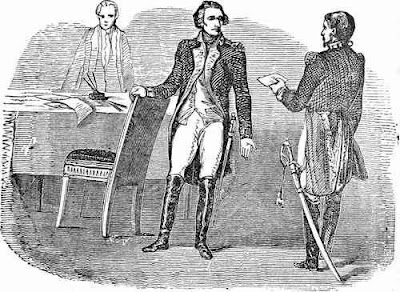

James Armistead stood beforeLafayette in tattered work clothes and a ragged jacket. Months earlier, he hadoffered his services to the Continental Army and became a spy in the traitorousBenedict Arnold’s camp. His secret reports enabled Lafayette to wage abrilliant campaign to check, if not repulse, the renegade Arnold, now a BrevetBrigadier General in British employ.

Lafayette and Armistead

Lafayette and Armistead“Is spying on Lord Cornwallis thesame as spying on Arnold?”

Armistead’s coal-black eyesflashed. “It’s always more satisfying to deceive a deceiver, sir.”

Lafayette smiled mischievously.“Well put, Monsieur Armistead.”

“Sir, it’s better if you justcall me Junius.” His eyes shifted left and right. “You know, just in case.”

The comment impressed Lafayette,and he nodded in agreement. He eyed the papers Armistead had drawn up. Thespy’s reports were always concise and precise. “Are you sure of this, Junius?”

“Indeed, sir. If you move forcesto that position at that time, you will deny General Cornwallis his last chanceof reinforcement and, more importantly, replenishment. His men also suffermiserably from lack of food and other vitals. Even their officers mumble aboutit.”

Lafayette nodded. “How fitting,as the Americans have gone all these years of struggle on empty bellies andwearing….” He paused as he eyed the rags on Armistead’s back. “Insufficientclothing.”

“It will be dark soon. I mustreturn as soon as I have the cover of the night.”

Lafayette eyed the man withwonder. “You have risked your neck for many months. That is commendable enoughfor any man, but for a slave, it is a thing of wonder.”

“I believe in the cause and thatI will justly earn my liberty.”

Lafayette’s head moved slowlyfrom side to side. “I truly hope so.”

Enslaved SpyThe above excerpt from my novel, TheLafayette Circle, is a fictionalized event. Still, it portrays the actualderring-do of a man whose commitment and courage transcended his race, hiswelfare, and his bondage. Just who was this man? James Armistead was a slaveowned by one Wallace Armistead of New Kent County, Virginia. Born on hismaster’s plantation, little is known of Armistead’s early years. Even his birthyear is debated—estimates range anywhere between 1746 and 1760.

Area of Armistead's Birth and Yorktown Campaign

Area of Armistead's Birth and Yorktown CampaignIn 1781, the Marquis de Lafayettewas leading American forces near Yorktown, where the British commander, MajorGeneral Charles Cornwallis, and his Army had dug in. The Franco-American forceswere enroute. It was Lafayette’s task to prevent Cornwallis from escaping thecauldron he was soon to be in. When young James Armistead received permissionfrom Wallace to join the American Army, it was with the proviso he would remaina slave after his service.

Lafayette’s AgentLafayette, a champion ofemancipation, might have had other ideas, but he needed the services of theyoung man who knew the area—he needed a spy. Since the British emancipatedescaped slaves, that became Armistead’s cover story when he entered the Britishcamp as Juniper, the runaway. His task initially was to courier intelligencefrom spies behind British lines. When they learned he belonged to a localplanter, the British took no heed of the young black man.

British camp at Yorktown

British camp at Yorktown

Armistead’s race and status as anenslaved person were perfect—his lowly position enabled him to slip in and outof both sides' camps without drawing attention. His knowledge of the land helpedhim to avoid detection when needed and find the best routes to travel. Theunsuspecting British paid him no heed as he ambled through the camp, listening toconversations.

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold

Slipping out of camp, he wouldbring Lafayette details on British plans, capabilities, and, most of all, thestate of their morale. The British trusted him. At one point, the traitor Benedict Arnold tasked Armistead togather information directly from Lafayette’s headquarters. By the height of theYorktown campaign, Arnold had gone back to New York. Cornwallis was holed up inthe port on the York River, hoping for reinforcements from General HenryClinton, the British commander-in-chief.

Double AgentAs the stakes grew higher,Cornwallis grew desperate and decided to use him to spy on the Americans,tasking him to bring back information on American troop strength and movements.Armistead was now a double agent, playing the dangerous game in the espionagebusiness. Of course, he reported right to Lafayette, who decided to use theopportunity to deceive his opponent—a classic use of a double agent.

Major General Charles CornwallisDeception

Major General Charles CornwallisDeceptionLafayette scribbled a letter toAmerican general Daniel Morgan, citing completely bogus units. After crumplingit up and rubbing some dirt on it, Armistead tucked it in his jacket and tookoff. Once in the British camp, he told the officers questioning him that he hadobserved American regiments marching and was returning with the “intelligence”when he found the paper on the road. Explaining he could not read it but tookit just in case it might prove of value. Upon reading the note, the Britishwere impressed with the intel coup.

Armistead's note fooled the British

Armistead's note fooled the British

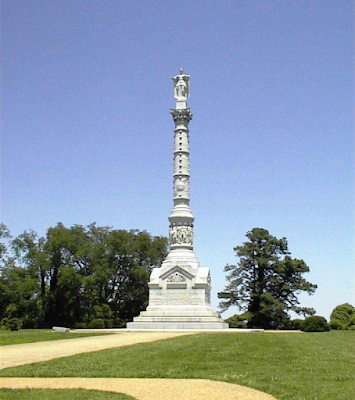

Armistead’s daring had helpedLafayette pull off a high-stakes deception—the appearance of new units keptthem on the defensive. The British would soon face the combined Franco-Americanforces and capitulate at Yorktown on 19 October 1781.

Yorktown Surrender

Yorktown Surrender

An unlikely postscript writtenyears later (in the 19th century, in fact) puts Armitage at apost-surrender dinner where General Washington hosted Cornwallis. Thevanquished British general is said to have remarked. “Ah, you rogue, you havebeen playing me a trick all this time!”

Struggle for FreedomJames Armistead’s post-war fatewas a sad reminder of the cruelty of slavery and the law. The VirginiaEmancipation Act of 1783 granted manumission to slaves who renderedconsiderable military service to the cause. In a cruel twist of fate,Armistead’s service as a spy was not deemed military service, and thus, heremained the property of Wallace. As egregious as this seems, one needs to remember that a spy was considered contemptible and spying dishonorable to theeighteenth-century mind.

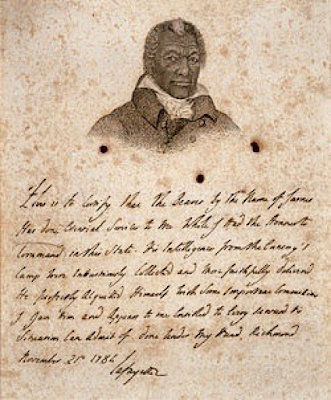

James Lafayette Armistead

James Lafayette ArmisteadHowever, the good angels finallyintervened when General Lafayette endorsed James Armistead’s petition forfreedom to the Virginia Assembly, which they granted in 1787. To honor the manwho came to his aid, James, on manumission, officially changed his name toJames Armistead Lafayette.

Lafayette's letter helped bring freedom

Lafayette's letter helped bring freedomFreedom and Friendship

The freeman James ArmisteadLafayette purchased land in New Kent County. Eventually, he married and hadchildren. Like so many other veterans of war, he fought a long-standing battleto gain a pension, which he finally received in 1819. When General Lafayettemade his celebrated tour of America in 1824, he acknowledged Armistead at theYorktown commemoration. Before the assembled crowd, the spymaster embraced thespy—a unique event and a fitting recognition for the former slave’s bravery andresourceful service to the Glorious Cause.

Yorktown Victory Monument

Yorktown Victory Monument

April 30, 2024

Fallen Founder

For hours, Doctor Joseph Warren had been piecing together reports and rumors from sources close and not so close to Boston’s British occupiers. One of the last of the Committee of Safety left in the city, he served as organizer of spies and reporter of rumor, innuendo, and sometimes—intelligence. He glanced at the Almanack on his desk. It read April 18th,1775.

Joseph Warren remained in occupied Boston

Joseph Warren remained in occupied Boston

The soft rap at the door stirred him from his writing.

“What brings ye here at this early hour?” he asked. The visitor was one of his better sources.

“A column is definitely leaving in the morning. Hoping to seize the rebel leaders, Hancock and Adams. They’ll be traveling over water.”

Warren scratched out the rest of his source’s information. “Thank ye, sir.”

Warren ran sources across Boston

Warren ran sources across Boston

When the informant left, he sent for two of his ablest men. For weeks, his dwindling network had sent him bits and bobs on British activity, but this was a solid warning, and he needed to act. When William Dawes and Paul Revere arrived, he gave them instructions, saying finally, “The good work of patriots have provided enough warning to steal a march on the British, but we must get the word we must take advantage of it. Go now, and Godspeed!”

Nightriders spreading the word

Nightriders spreading the word

The spymaster, whose tireless intelligence work helped launch thousands of farmers and townsfolk against the cream of the British Army, was well-known to the authorities. A farmer, Harvard scholar, schoolmaster, surgeon, and family man, he was a political activist who pushed back against Crown policies.

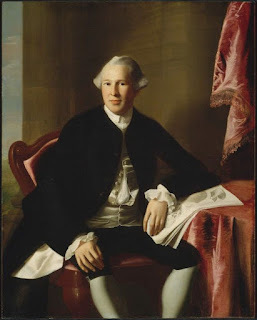

Doctor Joseph Warren

Doctor Joseph WarrenFrom Surgeon to Patriot

Born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1741, young Joseph Warren had risen from a yeoman farmer to part of the colony's landed gentry. After Harvard, he studied medicine under Doctor James Lloyd. Warren became a prominent surgeon and was celebrated for using the new technique of immunization against smallpox during an outbreak that ravaged the community. One of his patients, a lawyer named John Adams, recruited Warren into his circle of political confidants.

Pioneer in smallpox treatment

Pioneer in smallpox treatment

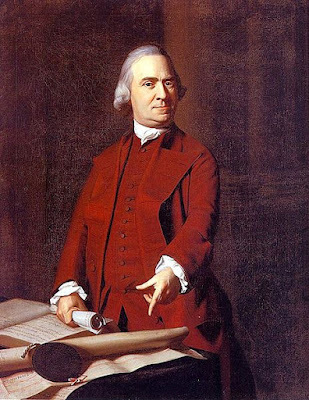

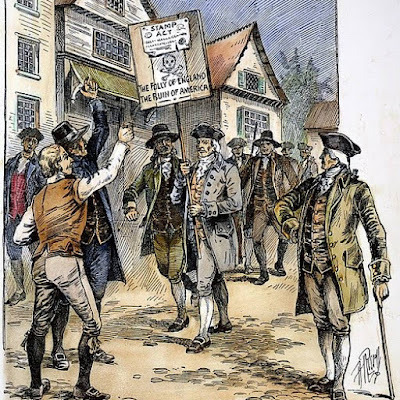

The Stamp Act of 1765 drove Warren from a moderate Whig to a leading radical in Boston politics, placing him in the ranks of Sam Adams, John Hancock, and James Otis. Political gatherings over coffee and raucous protests soon competed with his practice, farm, and family. But the brilliant thinker, organizer, and man of action made time for all. But what set him apart was his leadership by example.

Equally fervent politico Sam Adams Passionate Speaker

Equally fervent politico Sam Adams Passionate SpeakerWarren had a knack for retail politics, penning broadsheets, organizing events, and speaking in an oratory that galvanized crowds. He opposed the barrage of regulations from London and the Royal Governor. The Stamp Act, in particular, aroused his ire. On the second anniversary of The Boston Massacre, Warren gave a fiery tour de force oration as he defiantly eyed the British in the audience.

Defying the Stamp Act

Defying the Stamp Act

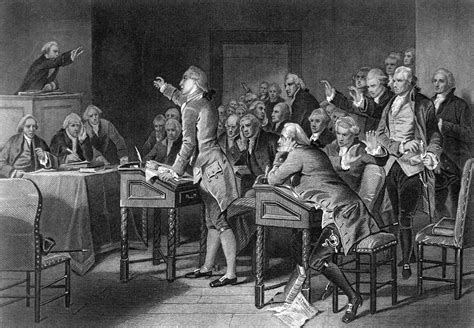

His passionate speech brought him a notoriety across Massachusetts and beyond. Warren gained celebrity throughout the colony for his scorching speech memorializing the second anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Two years later, he was an original member of Boston’s Committee of Correspondence.

Committees of Correspondence drove the Revolutionary agenda

Committees of Correspondence drove the Revolutionary agenda

In 1773, Warren was among the leaders protesting forcefully against the Tea Act imposed by London, and he likely had a hand in planning Sons of Liberty’s famous raid that December on the merchant ships—the Boston Tea Party.

Boston Tea Party Organizer?

Boston Tea Party Organizer?Not content with being the spymaster behind the scenes, Warren saddled up the day after dispatching the night riders and rode out to Concord battlefield, put on his surgeon’s hat, and began treating the wounded militiamen. For the next few months, he was a whirlwind of political leadership and military action.

Riding to the battlefield - rare photo

Riding to the battlefield - rare photo

As president of the Third Massachusetts Provincial Congress, he acted swiftly to spread the word and garner support across the colonies for transitioning from rebellion and insurgency to war. His account of the actions at Lexington and Concord reached readers in England a fortnight before General Thomas Gage’s official dispatch.

Warren's London dispatch scooped General Gage

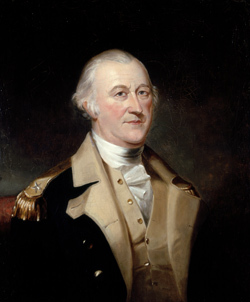

Military LeaderWhile doing all this, he helped General Artemus Ward assemble and shape the militia regiments of the New England Army forming around Boston—soon locking the redcoats in a cauldron from which they would never escape. Warren’s talent and decisive actions gained him an appointment as a major general of the militia on 14 June 1775. Fate and his innate modesty would deny him the assumption of those duties.

First Commander - Artemus Ward

First Commander - Artemus Ward

The rattling of drums meant the British were stirring, and spies reported plans to assault the Americans digging in on Breed’s Hill in Charleston—a town across the water north of Boston. Warren arrived with a musket, pistol, and saber but refused to pull rank and assume command from the commander in loco, French and Indian War veteran General Israel Putnam. Instead, Warren volunteered to fight in the line, serving under Colonel William Prescott.

Israel PutnamBreed's Hill

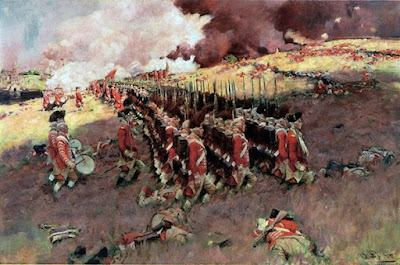

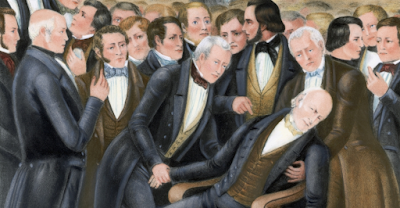

Israel PutnamBreed's HillOn 17 June 1775, the regulars ferried to the neck, and rows of redcoats assembled at the base of the long sloping hill where the rebels waited. The New Englanders were ready in all respects: will, determination, and courage, plus the high ground, prepared breastwork with ample fields of fire. But they lacked an essential of 18th-century warfare—gunpowder. The volunteer Warren fought bravely with his comrades and fellow patriots— who shot two determined British attacks to pieces in volleys that filled the air with lead and smoke.

The Crimson Wave

The Crimson Wave

Warren’s commander, Colonel Richard Prescott’s steely eyes, watched the wave of crimson rumble up the hill one last time—barely enough powder for a volley—not enough to stop them. At the last possible moment, he ordered the fire. The woosh and boom of the volley attested to its weakness. The redcoats dropped but not in the numbers previously. Now, they were coming with their own grim determination.

William Prescott scans the battlefield

William Prescott scans the battlefield

The patriots’ lack of powder now carried the third British charge over the breastworks and into the trenches. A ferocious melee—confused hand-to-hand combat ensued. Warren helped cover the retreat of his comrades but was quickly gunned down. Later, the redcoats, angered over their heavy losses at Breed’s that day, pierced his body with bayonet thrusts. Days later, Warren’s body endured further mutilation and decapitation by a naval officer, Lieutenant James Drew. After these atrocities, the body of one of arguably the most prominent and promising men in America was tossed into an unmarked grave.

Desecration of a Hero

Desecration of a Hero

Joseph Warren’s ravaged remains lay in a shallow grave—discovered some ten months later when the British had, at last, evacuated Boston. His brother and Paul Revere identified the remains through dental forensics. Revere, the tinsmith, had fashioned teeth for the doctor. Doctor Joseph Warren was officially buried at Forrest Hills Cemetery in 1855. One of the first lamented martyrs of the Revolutionary War is commemorated by a statue in the Bunker Hill Monument.

Joseph Warren Statue at Bunker Hill Monument

March 31, 2024

The Once and Future Spy

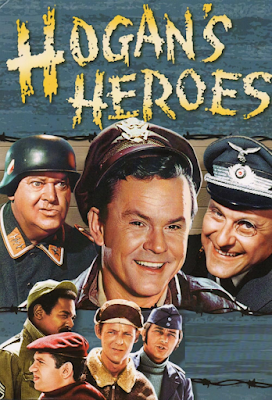

Lovers of TV Land likely recall the hit TV comedy of the 1960s, Hogan’s Heroes. The premise was a team of spies get themselves shot down over Nazi Germany to set up a spy cell operating from a prison camp (Luft Stalag 13) in the heart of Germany. From there, Colonel Hogan and his eclectic band maintained radio contact with “London” while coordinating a host of activities from espionage to sabotage. Much of the show centered on gags at the expense of their hapless captors, Colonel Klink and Sergeant Schultz, but they often slipped out of the prison camp to nearby Hammelberg for clandestine missions. However, unlike other POWs—they would sneak back in.

POWs as Spies - but for laughs

POWs as Spies - but for laughsWinter War

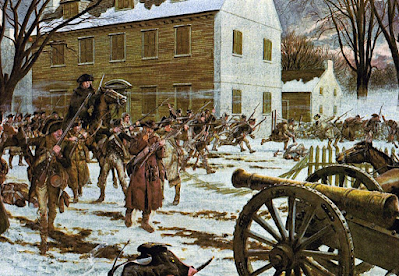

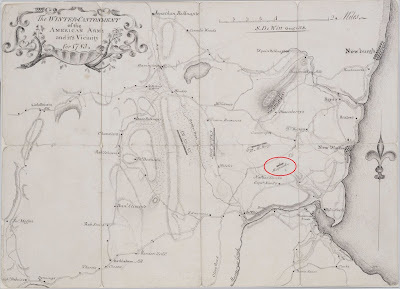

Something like this occurred during the height of the American War for Independence when General Washington needed intelligence following his victory at Trenton. Word had come that General Charles Cornwallis was leading an army south to exact revenge for the embarrassment. Washington ordered that someone be sent to Brunswick to determine the size of British forces, particularly the forces guarding recently captured General Charles Lee. The state of British supply trains was also of interest as Washington had a notion of marching north to seize their baggage and supplies for his under-supplied army.

Christmas 1776 Victory at Trenton

Christmas 1776 Victory at Trenton

Lieutenant Lewis Costigan of the 1st New Jersey Continental Line Regiment volunteered for the task. He was perfect for the mission, as he had been a merchant in that part of New Jersey and was most familiar with the area. Costigan’s mission is reminiscent of Lieutenant Jeremiah Creed’s spying in my novel, The Cavalier Spy. Costigan headed north over icy roads in a bitter-cold winter that chilled the soul. He evaded British patrols, sentries, and Loyalist informers, avoiding scrutiny. Costigan was gathering the intelligence required by Washington when British light dragoons swept in and took him captive. The gutsy officer was in uniform, so his captors did not treat him as a spy.

British dragoons foiled Costigan's first espionage venture

British dragoons foiled Costigan's first espionage venture

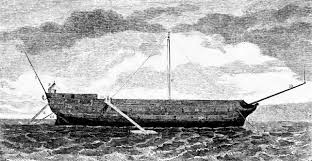

The British sent their new prisoner to New York City, where he was soon given parole, a fairly routine practice that let officers move about freely. Less fortunate prisoners, meaning enlisted men, were sent to the Sugar House or, even worse, the prison hulks (ships) to wither and die. However, with restrictions to which they pledged as gentlemen, officers fared better. Paroled officers were prohibited from involvement in military activity, communication with colleagues, or criticizing the British war effort. Paroled officers agreed to report back to the British if so directed. Costigan led the humdrum life of a parolee, diddling about the garrison city, visiting taverns, and rubbing elbows with the locals. He was formally released as part of an exchange for a British officer in September 1778.

Prison Hulk HMS Jersey

Prison Hulk HMS Jersey

Learning of this, Washington wrote his Commissary General for Prisoners, Colonel John Beatty, the man in charge of handling prisoner affairs, including exchanges. Washington pressed him to get Gostigan out expeditiously but not to appear too anxious to the British. His Excellency had plans for his once and future spy. General William Alexander, who called himself Lord Stirling, was to press Costigan to enter the breach once more. Costigan took a boat to New Brunswick, where he received a new mission from one of Stirling’s subordinates, Colonel Ogden, who pressed the exchanged parolee to return to New York for a few months longer and spy for the Continental Army! Washington must have been desperate for intelligence at the time, for the mission was highly unorthodox and packed with grave risk. For his part, Costigan must have had a brass pair and ice in his veins to agree.

Lord StirlingAgent Z

Lord StirlingAgent ZWhat cover would Costigan use to slip past the British and lurk about a garrison brimming with enemy troops, Loyalists, and the dastardly Provost William Cunningham’s thugs? Why, none, actually. His handlers were betting the British prison bureaucracy would not realize he had returned, nor that they would have alerted the garrison regiments, Loyalist units, and Cunningham’s provosts when they exchanged prisoners. Stirling and Ogden were betting on the stovepipes not joining, and they were wagering Costigan’s life. Costigan was given the code name Agent Z for the unusual mission.

Agent Z would walk among the NY garrison that winter

Agent Z would walk among the NY garrison that winterPrisoner Spy

Cositgan made his way back and took up the subterfuge of hiding in plain sight—living as the prisoner on parole he had been. Since he was legally exchanged, his earlier parole restrictions no longer applied. Curiously, no one seemed to take much notice of Costigan as he roved the city, noting troop movements, living conditions, supply problems, and more. Word of his exchange had clearly not spread among the dockside dives nor the city’s many taverns and coffee houses. To all, he was just another parolee out and about. Using his code name, Agent Z, the volunteer prisoner sent his intelligence reports to Washington through Colonel Ogden and Lord Stirling.

Agent Z had the run of the City

Agent Z had the run of the CityIntelligence

Agent Z managed to get three reports out before he departed New York. The first was dated 7 December 1778. It contained intelligence on troop and ship movements, the whereabouts of the British commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, the state of supply (low on bread), the name of captured prize vessels, and the source of British provisions from sympathizers and profiteers in New Jersey. His correspondence referred to several other reports on troop strength, but it is unknown whether these ever made it through.

Sir Henry Clinton

Sir Henry Clinton

A second report to Washington dated 13 December 1778 had many more details on British activity that amounted to “indications and warning” on British forces sailing south for Georgia. Lord Sackville (George Germain), the British Secretary for the Colonies, had adopted his Southern Strategy, which would begin with seizing Savannah on 29 December. He spotted notorious former Royal Governor William Tryon and reported on the movement and promotion of other senior officers.

Agent Z provided I&W on Germain's Southern Strategy

Agent Z provided I&W on Germain's Southern Strategy

Costigan’s last report of 19 December provided details on British officers who had deserted in Florida and the status and size of “the Jamaica fleet,” which he estimated at 40 or 50 vessels.

The Spy Who Came in from the ColdAgent Z clearly had a knack for observation and elicitation. There is no record of how he got his reports out. Did he coopt legal travelers? Send correspondence under an assumed name? Whatever he used must have hit a snag, for he left New York in mid-January 1779, presumably posing as an exchanged parolee. In March of 1779, General Washington queried Lod Stirling as to his reporting (or lack of). Stirling laconically replied that Agent Z was no longer active and believed to be “out” (presumably of the city and the intel game) and believed to be residing in Brunswick.

Lieutenant Lewis Costigan - Agent Z

Lieutenant Lewis Costigan - Agent Z

Lieutenant Lewis Costigan’s activities show how Washington used multiple channels of collection, as he was not connected to the Culper Ring organized by Major Benjamin Tallmadge but reported through Colonel Ogden to Lord Stirling. His exploits provide a unique glimpse into espionage in the American Revolution. As Agent Z, he played the role destined for the unfortunate Nathan Hale, although his ingenious use of a “non-cover” provided an elegant twist. Hiding in plain sight seems to have been all the tradecraft he needed.

February 29, 2024

Defiant Doyenne

This leap-year edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies highlights the bold and brave housewife who played a hand in saving her home, her state, and her country. Meet the up-country distaff doyenne who stood up to British bullies like few men could.

Martha Bratton was a patriot farmwife

Martha Bratton was a patriot farmwife

Upcountry South Carolina saw some of the most vicious fighting of the American War for Independence. The rugged Scots-Irish settled on the rolling hills and fertile meadows north of Columbia. Among them were William and Martha Bratton, who, in 1766, bought 200 acres along the South Fork of Fishing Creek in what today is York County, South Carolina. William built a rough-hewn log home and, with the help of a few slaves, turned the land into a thriving, if modest, homestead.

The Bratton's built a log farmhouse on the frontier

The Bratton's built a log farmhouse on the frontierThe world changed when the Shot Heard Round the World was fired in April 1775. As South Carolina formed both militia and Continental Line regiments for the upcoming struggle, William Bratton did his bit and marched off to join. Martha was now the head of the household and responsible for keeping their plantation alive.

Shot Heard Round the World - Lexington Green

Shot Heard Round the World - Lexington Green

But in May 1780, the British took Charleston and occupied a string of garrisons from the port city on the low country coast to the famous star fort at Ninety-Six, the last outpost along the South Carolina frontier. The governor of South Carolina had asked William Bratton, a militia commander, to use his house to store some of the patriot gunpowder, which was a precious commodity for both sides but mainly for the patriots. With William away, Martha, as head of the household, had responsibility for securing it.

Ruins of Ninety-Six

Ruins of Ninety-SixThe Whig-Tory struggle in the Carolinas was brutal, with neighbors fighting neighbors and sometimes families being torn apart. Bands from both sides roamed the countryside, either supporting the Continentals and Regulars or acting as independent bands. Spies and traitors lurked everywhere. British gold easily bought information. Exactly how they found out that Martha held a store of the powder is unknown. What is known is they approached her farm to demand she turn it over or face reprisal.

But spies worked both ways, and someone raced to the Bratton farm to warn Martha of the approaching column. She knew she did not have time to move it—it filled a nearby shed. What to do?

Gunpowder was a valuable commodity

Gunpowder was a valuable commodity

Martha ordered one of her slaves, named Watt, to bring her a flaming piece of wood from the kitchen stove. Before the British could arrive, Martha tossed the flaming faggot into the shed, and in seconds it blue sky high with a thunderous boom that sent chunks of burning logs into the air and thumping into the fields around them.

Gunpowder explosion

Gunpowder explosionThe explosion warned the British, who arrived to see the last charred timbers of the shed collapse into a smoking pile. She defiantly told them, "Let the consequence be what it will. I glory in having prevented the mischief contemplated by the cruel enemies of my country."

Martha had foiled them, but she was now marked as a rebel, and they would keep an eye on her and the Bratton farm.

By the summer of 1780, the war was setting York County ablaze. Columns of British Regulars, patrols of mounted dragoons, and bands of Tories and Loyalist Provincials scoured the land. This was the epic struggle between American partisans like Sumter and Marion and the likes of Banastre Tarleton and Patrick Ferguson. But the most hated enemy was the Loyalist officer of the British Legion, the German-born Captain Christian Huck. In a struggle that featured brutality on both sides, Huck stood tall. He rampaged across the state, destroying rebel property, burning homes, and killing his enemies.

Loyalist Dragoons rampaged the Carolinas

Loyalist Dragoons rampaged the CarolinasOn 10 July, Huck set out to arrest rebel leaders in York County at the head of 120 determined men, But word spread like wildfire, sending most scurrying for safety. On Huck's list was the husband of the rebel whose wife had humbugged the British before—William Bratton. As they rode hell-bent for leather toward the plantation, Huck's men, true to form, took foodstuff, horses, and other valuables from the small farms along the way.

Fortunately, Colonel Bratton's militia regiment was on the Catawba River, where it had joined up with General Thomas Sumter's forces. Huck's troops arrived at the Bratton plantation as the sun was setting on 11 July. Knowing the threat Huck and his men posed, Martha Bratton sent Watt to warn her husband of their presence.

Martha sends Watt to warn her husband

Martha sends Watt to warn her husbandEntering her log home, Huck demanded to know her husband's whereabouts.

Notorious Christian Huck

Notorious Christian Huck"You'll have to find him on your own, as I am not privy to his whereabouts, sir," she told the British commander.

An enraged officer reached for a reaping hook dangling from the wall and thrust the cutting edge to her throat. "Madam, you'll tell us what we want, or you'll not say anything again, as your pretty head will be shorn from your shoulders!"

Martha defied all threats

Martha defied all threats

Martha straightened and glared defiantly. "Even if I knew where my husband and the militia were. I would not betray them or my country, sir. Do your worst!"

"Put that thing down," ordered Huck as he drew his saber and slammed its hilt into his hot-tempered officer, sending him tumbling to the heavy plank floor. Frustrated by her refusal, Huck angrily ordered Martha to fix a meal for him and his officers.

Once they had eaten their fill, the officers and their men mounted and rode off for their next destination—the nearby William plantation. The delay gave the patriots time to assemble a force that gathered at the plantation and launched a surprise attack as the sun rose. Lead flew in all directions, but the Loyalists were trapped. Huck leaped on his horse to escape but was struck by a hail of musket balls. The notorious raider fell out of the saddle, dead.

Huck's forces were surprised and destroyed at Williams Plantation

Huck's forces were surprised and destroyed at Williams PlantationIt did not take long to eliminate one of South Carolina's worst scourges. The battle was over in just a quarter-hour. The American Legion lost 30 killed and 50 wounded, with the rest taken prisoner. Almost poetically, some of the gravely injured Legionnaires were taken to the Bratton farm, where Martha herself ministered to their wounds.

Huck's defeat was just a minor skirmish, but it gave a considerable boost to patriot morale in the Carolina backcountry, and more and more men flocked to the cause. From it stemmed a chain of events that included the Overmountain Men crushing Fergusson's Loyalist brigade at King's Mountain and Dan Morgan smashing Tarleton at Cowpens. And finally, Nathanael Greene forced Cornwallis's abandonment of the Carolinas for the safety of Yorktown, Virginia. So, in no small way, Martha Bratton's courage and craftiness played a pivotal role in the ultimate defeat of the British cause in the Carolinas.

The family expanded the farmstead after the war, with their son building a new home, which is now the site of a historic interpretation center called Brattonsville.

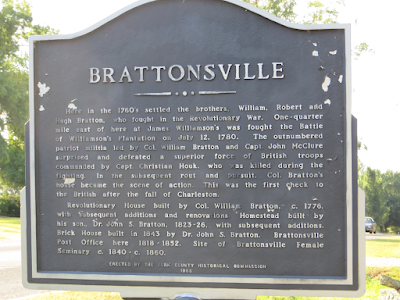

Historic Brattonsvile, South Carolina, commemorates the life and times of William & Martha

Historic Brattonsvile, South Carolina, commemorates the life and times of William & Martha

January 30, 2024

The Lafayette Circle

I have a tradition of producing a blog post on the"back story" of most books I write. With the release of The LafayetteCircle, it is time to do it again.

A Friend in NeedAbout a year ago, a Xavier High School classmate, Peter Reilly,reached out to me with a suggestion that I get involved in helping celebratethe upcoming 200th Anniversary of the Marquis de Lafayette'scelebrated tour of America in 1824. Truth be told, I had never read or heard ofthe event, so I was caught off guard. Peter, a CPA who is a contributor toForbes.com and Think Outside The Tax Box, is also chair of the Massachusettscommittee for the Bicentennial of Lafayette's Farewell Tour 2024-2025. Iwondered how to respond.

Lafayette by Bryon Line

Lafayette by Bryon Line

Maybe I could repost items about the upcoming celebrationon my social media platforms. Or write a book about life in America in 1824?I knew quite a bit about Marie-Jospeh-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, the Marquisde Lafayette, from my study of the American and French Revolutions but littleof events after the fall of Napoleon in 1815. Most of what I remembered fromthat era came from Peter Neary's American History class when I attended XavierHigh School in New York City—Jacksonian Democracy and all that.

Background

When in doubt, do some research. I started by re-reading twolegacy books on Lafayette from my library and engrossing myself in a recentlyreleased biography. I also took the opportunity to join The Friends ofLafayette, and when I did, I got behind their paywall and found a trove ofinformation on Lafayette's trip and the dynamics behind it. A review quicklydrew me to the conclusion that this was more than a feel-good junket—althoughit certainly was that, too.

A World in Upheaval

Although the Congress of Vienna that convened with NapoleonBonaparte's abdication in 1814 set up a framework for a much-needed fifty yearsof peace among the European powers, the world itself was shaking from the movementof the tectonic plates of liberty. The Spanish colonies in America looked toNorth America and, to some extent, to revolutionary France as examples.Liberation movements, some long-simmering, began to erupt into rebellion andwars of liberation.

Congress of Vienna

Congress of ViennaNames like Simon Bolivar and Bernardo O'Higgins would becomeexamples equal to George Washington throughout most of the continent to oursouth. In Spain itself, the newly formed Asturian battalion, one of tenorganized to sail to America to suppress the wars of liberation, revolted, ledby its commander, Rafael del Riego y Flórez.

Rafael del Riego y Flórez

Rafael del Riego y FlórezOther regiments joined. The soldiers demanded a return tothe 1812 constitution. In March 1820, they surrounded the royal palace, and theking capitulated. A junta ruled Spain for several years until the autocrats ofEurope pushed Royalist France to invade and put the king back in his rightfulplace of rule as an absolute monarch. Now, General de Riego was put on trialand hanged for treason.

Entry into GeopoliticsThe long-isolationist United States grew concerned with thepossibility of some European powers stepping into the void of Spanish authorityin the New World. Britain felt the same, especially fearing Russia's incursionsfrom the North and the threats to its holdings in South America and the WestIndies. A suggestion made for a joint declaration of status quo ante in the NewWorld resonated somewhat with President Monroe but not the Secretary of State,John Quincy Adams. After all, two wars were fought against Britain, one quiterecently. America would render its own statement. Adams was the prime drafterof what became, many years later, called The Monroe Doctrine.

James Monroe

James Monroe

Monroe's administration was coming to a close as the nationapproached its 50th Anniversary. He would lawfully be out of officeby April 1825, yet he wanted to do something celebratory prior to hisdeparture. Inviting the last surviving Continental Army general to return tohis adopted land seemed a great way to begin the party on his watch, underscorethe arrival of the young republic on the world stage, and rebuild patrioticfervor. Lafayette was beloved in America and was a world-renowned figure forhis lead role in two revolutionary movements.

Lafayette in Winter

Lafayette in Winter

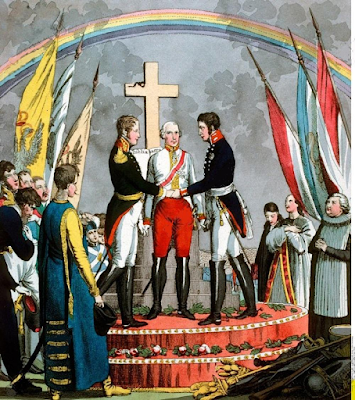

As I learned all this, I realized the tour was more thanjust a feel-good event but a tool to use in both internal and externalpolitics. This was pretty slick. Others thought so, too. Among theothers were the members of the Holy Alliance, a reactionary (and not so holy) pact among the Empire of Austria, the Kingdom of Prussia,and the Empire of Russia aimed at curbing the spread of democracy andbuttressing autocracy.

Holy Alliance?

Holy Alliance?Of course, I built on this by creating the fictionalsubcommittee of the Holy Alliance that I named the Aulic Council. Thehistorical Aulic Council was an executive-judicial council for the Holy Roman Empirethat started during the Late Middle Ages and ended when Napoleon dissolved theHoly Roman Empire in 1806. I spin it into a Spectre-like organization run byvillainous barons who harken to Austen Powers's Mr. Evil.

Mister Evil

Mister EvilProtecting the Man

How does a country with no Secret Service or FBI and a smallmilitary scattered in coastal forts and western outposts protect a dignitaryduring a highly publicized series of events? That's the central theme of thetale. An eclectic mix of characters in and out of government come together withjust minimal help from the Federal and state governments. Catholic monks, diplomats, US naval officers, US Marines, the New York militia, and others all play a role in protecting the general.

They call themselves The Lafayette Circle. New York Militia Guarding Lafayette

New York Militia Guarding LafayetteBoris and Natascha x Three

Three assassin teams, each consisting of one male and onefemale, are dispatched to seek out Lafayette and kill him. This is anothereclectic cast of characters made intentionally evil but like famed "nogoodnik"Boris Badanoff and his sultry sidekick Natasha in the Rocky and BullwinkleShow, not totally unlikeable. Their struggle to "acquire" their target as theyroam early 19th-century America adds to the suspense.

Boris and NatashaWho's Your President?

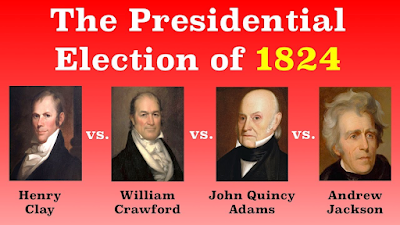

The fact that one of the most controversial presidentialcontests in America's history takes place in the middle of all this provided asubplot I could not resist. The events are proof that the more things change,the more they stay the same with backroom deals, fights for votes, and a"rigged election" that was also, curiously, legitimate. The events thatdeprived Andrew Jackson of the White House in the 1824 election are moreobscure to most Americans than Julius Caesar's assassination, which at leastwas celebrated in a play by the Bard himself.

1824 Election was Controversial

1824 Election was ControversialYet the election took placeduring Lafayette's visit, and he was known by all the principals involved whenthe election was thrown to the House of Representatives for just the secondtime in America's history. Deals were struck, and John Quincy Adams went to the White House. The man with the most electoral votes went home to his estate, The Hermitage, outside Nashville. Lafayette would goout of his way to meet the war hero Jackson while he was home licking hiswounds.

The Hermitage

The HermitageCompanions

Lafayette's journey was captured by his personal secretaryAuguste Levasseur, who penned a personal account of the incredible journey, Lafayetteen Amérique, en 1824 et 1825 ou Journal d'un voyage aux États-Unis. Hisson, Georges Washington Lafayette, also accompanied the general. Both areinvolved in fictionalized scenes meant to move the plot along while exposing usto different sides of the great man. Likewise, Fanny Wright, a socialist activist (and Lafayette's purported mistress) from Scotland and some thirty years younger than Lafayette, accompanies him on part of the trip.

Frances "Fanny" Wright

Frances "Fanny" WrightGlimpses

The novel has several flashback sections—scenes meant to putLafayette back in his youth fighting the American Revolution, leading theFrench Revolution, and dealing with the consequences of both. These areintended to give a bit of historical perspective to those uninformed about hisrole in those earlier significant events that shaped the Western world.

Flashback: Lafayette's wounding at Brandywine 1777

Flashback: Lafayette's wounding at Brandywine 1777The Ordeal

I also attempted to provide a look at America and the worldin 1824. Travel was by wind, steam, and horse. It was slow and steady andalways an ordeal culminating in hundreds of stops across a vast continent. Meetingswith folks from all walks of life. Reminiscing with old comrades. Shakingthousands and thousands of hands around the clock. Lafayette's prodigiousschedule of events and speeches were like MAGA tours of the day and bound totake a toll on a man approaching seventy. Yet he did it with aplomb andgraciousness. One has to ask why, and the answer is simple. Indeed, he lovedAmerica and what it stood for. But even more than that, he loved its people.

The Lafayette Circle is available now!

The Lafayette Circle is available now!

December 30, 2023

The Prodigy

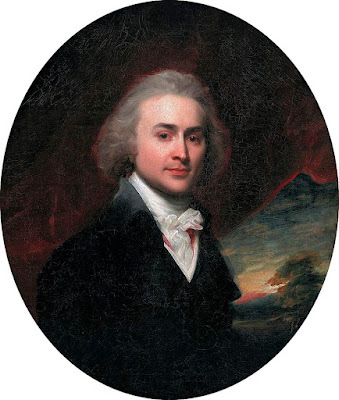

This final post of 2023 will profile another of the historical characters in my novel, The Lafayette Circle. Although John Quincy Adams plays a relatively minor role in this tale of intrigue and mayhem in early 19th century America, he does provide the seed of the ideas that made the Marquis de Lafayette's 1824-1825 visit more than just a celebration of bonhomie between two nations.

John Quincy Adams - the youthful diplomat

John Quincy Adams - the youthful diplomat

John Quincy Adams was fated to grow up and live in the shadow of his father, John, the accomplished lawyer, statesman, and politician who helped engineer the American Revolution and the foundation of America, becoming its second chief executive. Young John Quincy was born on 11 July 1767 at the family home in Braintree, Massachusetts, which is today's Quincy. His intensely patriotic and accomplished parents formed his early upbringing and schooled him in a classical education. The American Revolution seemingly unfolded before his eyes as he was among the many in and around Boston who watched nervously as the patriots battled lines of redcoats at Bunker Hill in 1775.

Watching Bunker HillExchange Student

Watching Bunker HillExchange StudentThree years later, he left his mother to accompany his father on a diplomatic mission to Europe, which was the beginning of his real education. From 1778 to 1779, he studied at a private school in Paris, where he developed his fluency in French, the language of diplomats. Following this, he attended the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, learning some Dutch.

The Boy Prodigy

The Boy Prodigy

By 1781, he was accomplished enough in French for his father to arrange John Quincy a post as private secretary to one of America's foremost diplomats, Francis Dana, who had been named US Envoy to Russia's court at St. Petersburg. When Dana's mission proved unfruitful, he returned to Paris, where he served as a secretary to the American Commissioners during their negotiations with the British.

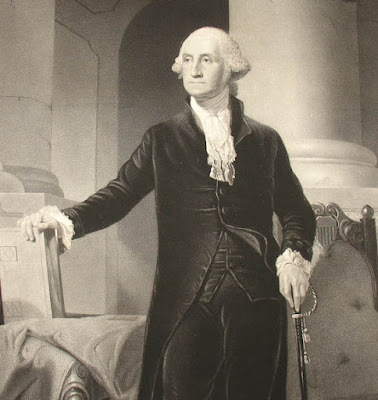

The Law and the HagueWhen the Treaty of Paris was signed, he returned to the US to study at Harvard College and then Newburyport under the tutelage of Theophilus Parsons, where he read the law. By 1790, he was a member of the Bar in Boston. Adams went into private practice but also began penning pamphlets on political doctrine and foreign policy, in the latter case supporting President George Washington's firm stance on neutrality. This gained him an appointment as US minister to the Netherlands in 1794.

President George Washington

President George WashingtonThe wars of the French Revolution were raging, and the Hague was a capital full of diplomatic intrigue. Adams's dispatches and letters provided the Washington administration (which included his dad as Vice President) valuable information. He served a temporary post in London to help bring about the 1794 Jay Treaty—a pivotal and controversial foreign policy initiative.

The DiplomatFor his able service, in 1796, President Washington appointed him US Envoy to Portugal, but when Dad became the nation's second president, he switched his son's assignment to Prussia. But pleasure before business—Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson, a diplomat's daughter whom he met in Paris when he was just twelve. She proved a charming and able partner to the rising young diplomat. They married in London before heading to Berlin, where he negotiated a treaty of amity and commerce with the Prussians. But in 1800, politics flipped on him with the election of Thomas Jefferson, who recalled Adams from his post.

Louisa Catherine Johnson AdamsPolitical Life

Louisa Catherine Johnson AdamsPolitical LifeAdams returned to Boston, where state and federal politics became his new playground. By 1802, he was a member of the Massachusetts State Senate, which elected him a US Senator from Massachusetts in 1803. Battleground is actually a more accurate description. Adams was as acerbic as his father and did not favor "factions." He voted his conscience, and that often put him at odds with one party or the other. He grew estranged from his dad's Federalist Party, which by now had turned on him.

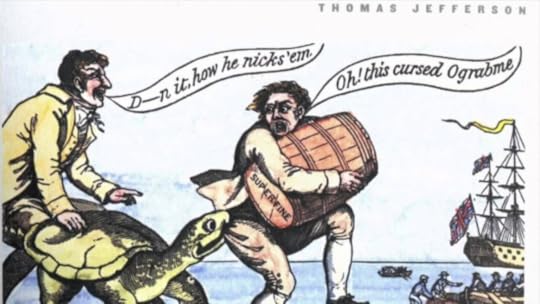

Support for the Embargo Act Cost Adams His Job

Support for the Embargo Act Cost Adams His JobThis all came to a head when he voted in support of Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act, a measure opposed by the New Englanders who valued Brtain as a trading partner. In 1808, the Massachusetts Senate voted him out of office, and he resigned. Adams aligned with the Republicans and took a position as professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard College.

Envoy to RussiaThe world was at war with Napoleonic France, and President Madison needed an A player to sort things out. The highly experienced Adams was the right man, especially as he had broken with the Federalists. From that perch, the astute Adams watched the dissolution of Emporer Napoleon Bonaparte's Army in 1812 and the destruction of his empire over the following two years. Adams was at the Court of St. Petersburg just when Czar Alexander rose in stature as a leader in the coalition against Napoleon.

Czar Alexander I - Power Broker

Czar Alexander I - Power BrokerTreaty of Ghent

Meanwhile, war had broken out between the US and Great Britain, Russia's ally. Adams jumped onCzar Alexander's offer to mediate in the fall of 1812. The initiative, with Adams as one of the lead commissioners, fell through. However, a follow-up attempt in 1814 under Adams's leadership resulted in the Treaty of Ghent. This face-saving status quo ante arrangement changed little diplomatically or politically. Still, it gave the small US the morale-building confidence of having gone toe-to-toe with what was now the world hegemon.

Signing Treaty of Ghent

Signing Treaty of GhentLike Father, Like Son

After a short stint in Paris, which occurred during Napoleon's short return to power in 1815, he followed in Dad's footsteps. He went to London, where he and Henry Clay negotiated a "Convention to Regulate Commerce and Navigation." Soon afterward, he became US minister to Great Britain, as his father had been before him and as his son Charles was to be after him. His stay at the Court of St.James was short, as Adams returned to the United States in the summer of 1817 to become secretary of state in the cabinet of President James Monroe. This appointment was primarily due to his diplomatic experience but also due to the president's desire to have a sectionally well-balanced cabinet in what came to be known as the Era of Good Feelings.

St. James Palace

St. James PalaceManifest Destiny

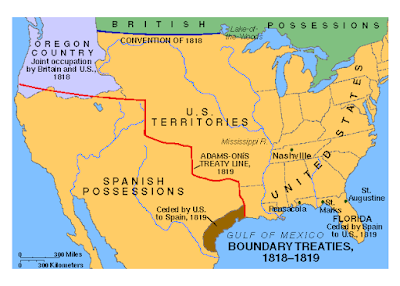

Adams's tenure as Secretary of State was, as one would expect, with someone groomed for the job since the age of fourteen—outstanding. He worked diligently with Spain to resolve the long-term dispute over America's western and southwestern borders. The Spanish Minister Onis agreed Spain would give up its claims to lands east of the Mississippi River. For his part, Adams decided the United States would forgo claims to Texas. The two settled on a boundary drawn from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Years of dispute were settled by the signing of what was called the Adams-Onis Transcontinental Treaty.

In 1818, he also settled the northern frontier dispute with Great Britain, establishing the 49th parallel all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

The Monroe DoctrineAdams was a principal driver of the US policy on foreign interference in the Western Hemisphere. This is his key role in my novel, The Lafayette Circle. Instead of a joint US-British proclamation regarding European powers and the Spanish territories in America, he convinced President James Monroe to go it alone. The letter he helped craft to Congress in late 1823 and promulgated in 1824 was a stern warning to those hoping to pick up some loose change as the former colonies seemed ripe for the picking to certain powers. What later became known as The Monroe Doctrine was intended to protect the newly independent lands from recolonization and became the cornerstone of US foreign policy for more than one hundred years.

James MonroeThe Second President Adams

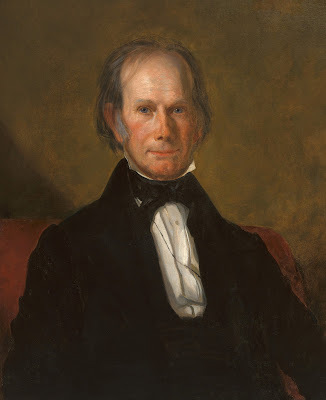

James MonroeThe Second President AdamsThe 1824 election was a scene of chaos and political maneuvering, all within the parameters set forth by the US Constitution. With none of the four candidates (Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William Crawford) receiving the requisite number of electoral votes, the election was thrown to the House of Representatives to select from the top three (Jackson, Adams, Clay) in a one-vote-per-state "play-off." Henry Clay viewed Jackson as a dangerous demagogue and threw his support to Adams, putting him in the Oval Office. The Jacksonians cried foul when Adams later appointed Clay as Secretary of State.

Henry Clay

Henry Clay

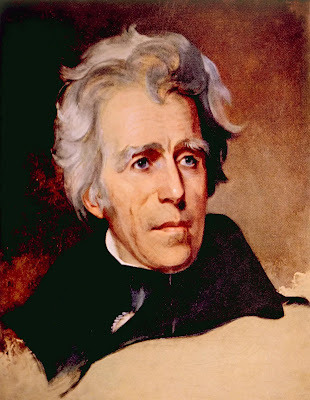

Adams worked long and hard as president, but the anger of the Jacksonians (who suspected a corrupt bargain) hung like a cloud over his term as they opposed him in everything. Adams's hopes of creating a national university and a national astronomical observatory were dashed. His idea that the western territories undergo only gradual development became dead on arrival. Even his infrastructure initiatives—building bridges, ports, and roads with financial aid from the Federal government were stymied. Jackson came back to crush Adams in the 1828 election.

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

In an interesting connection to my novel, The Lafayette Circle, one of Adams's first acts as president was to join General Lafayette on a farewell visit to the former president James Monroe at his Leesburg, Virginia estate.

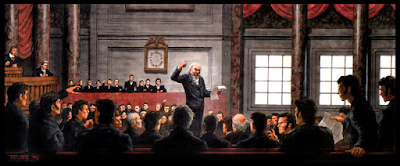

Representative of the PeopleIn a move that stunned many as "degrading to a former president," Adams stood for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1831, responding that serving the people as a representative in Congress was not degrading. He served the people in Congress until he died in 1848. In those years, he fought tirelessly against slavery and its expansion and against the various ploys by the slave block in Congress to expand and maintain their peculiar institution.

President John Quincy Adams

President John Quincy AdamsBold Advocate

When Africans arrested aboard the slave ship Amistad were bound to return to their masters, John Quincy Adams took up their cause, defending them in front of The US Supreme Court—and won their freedom. Adams's entire career had pointed him toward one primary goal—doing the right thing. In this, he had a mic of success and failure, but his undaunting efforts placed him among the best of early America's following (post-founding fathers) generation of leaders.

Defending the Armistead Slaves

Defending the Armistead SlavesThe Lion's Last RoarAdams was in the House of Representatives, battling a bill to honor Mexican War veterans. Adams had vehemently opposed the war as one of aggression partly aimed at expanding slavery. He stood to decry the vote when he collapsed. He was rushed to the Speaker's Room, where he died two days later, on 23 February 1848, from a stroke. The boy prodigy, now the lion of Congress, went down working and fighting at the age of 89 with his wife Louisa at his side. It is alleged that his last words were, "This is the last of earth, but I am composed."

Adams Died a Servant of the People

Adams Died a Servant of the PeopleNovember 28, 2023

The Third Virginian

It is a sad commentary that most Americans are more familiar with Marilyn Monroe than the first patriot with the same last name. And who knows? Maybe the Hollywood type who renamed Norma Jean was a history buff? But I digress. This profile reintroduces one of those nose-to-the-grindstone founders who quietly made his mark on America and the world. The fact that James Monroe is also an important historical figure in my novel, The Lafayette Circle, makes his story even more compelling.

Norma Jean

Norma JeanPlanter Orphan

James Monroe was born at the aptly-named Monroe Hall in Westmorland County, Virginia, on 28 April 1758. James's father was a mildly prosperous planter. Both of his parents died when Monroe was in his teens, and he took over the plantation and care of his siblings under the guidance of his mother's brother, Joseph Jones, a member of the House of Burgesses. Jones took young Monroe to Williamsburg and enrolled him in the College of William and Mary. His uncle also introduced him to the likes of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry—up-and-coming Virginians who would help change the world, as would young James.

Williamsburg

Williamsburg

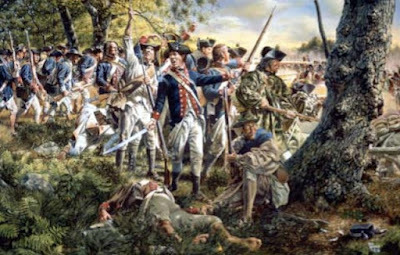

Williamsburg was abuzz with patriotic fervor. Monroe was still attending William and Mary College when the Revolutionary War broke out in April 1775. Eager to get into the fray as so many young Virginians were, he left William and Mary, and on 28 September 1775, Monroe was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Continental Infantry. His first commander was Colonel Hugh Mercer, who would rise to become one of General George Washington's most trusted generals until his untimely death by British bayonets at Princeton. Lieutenant Monroe marched north to New York City with his regiment the following year.

The Virginia Line

The Virginia LineYears of Combat

There, he first saw combat at Harlem Heights on 16 September 1776 and volunteered to accompany the rangers of Major Thomas Knowlton. Knowlton, mortally wounded in the skirmish, became the namesake of the Military Intelligence Corps' honorary award, which bears his name.

After additional fighting at White Plains in October, British General William Howe managed to turn the flank of the Continental Army but allowed it to slip away to New Jersey. Monroe's regiment marched south and west in a series of retreats that saw the Continental Army dwindle and American morale plummet. By late December, Washington's meager force was huddled on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River and in dire straits.

An Army in Retreat

An Army in Retreat

Things changed with the arrival of General John Sullivan at the head of the division of General Charles Lee. Curiously, Lee had allowed himself to get captured at BoskingRidge, New Jersey, by a party of British dragoons, including a young Banastre Tarleton.

John Sullivan

John Sullivan

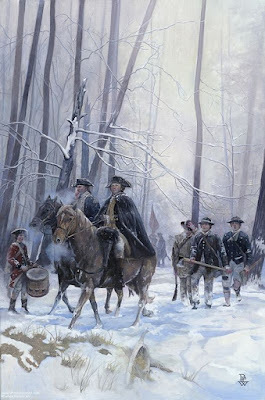

The added troops meant Washington was able to launch the plan he had been deliberating since crossing into Pennsylvania—a return across the Delaware. With Howe's forces controlling New York City and most of the Jerseys, the cause was at its nadir. He needed a bold stroke, so on Christmas night, Lieutenant James Monroe and Captain William Washington's company of Colonel Weedon's Third Virginia were poling their long Durham boats through the ice floes jamming the Delaware River. It was the night of the 25th and about as silent as Washington could hope for as his columns trudged through the blustery cold along icy wooded trails. Monroe had met a man named Riker along the way. He was at first thought a Loyalist, but it turned out he was quite the patriot and joined the ragged force plunging toward the Hessian-occupied town of Trenton.

Crossing the Delaware

Crossing the Delaware

At daylight on the 26th, the Continental forces attacked the sleeping town. Sentries were driven from their posts as the Virginians moved in from the north. Their objective—a two-gun battery manned by Hessians was positioned to blast the advancing Americans of Nathanael Green's brigade. The town was chaotic as sleepy musketeers and grenadiers stumbled from their quarters and shouldered firelocks.

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene

The pop, pop of desultory musket fire filled the chilly morning air. This soon grew in intensity, sending Monroe's company scattering for cover—they were the vanguard of their regiment and brigade. The Americans began to return fire, and more Continentals were arriving down King Street.

The boom of cannon from behind filled them with confidence. General Henry Knox's batteries were in action. Musket fire to the south also meant General Sullivan's brigades were attacking. But ahead lay that pesky Hessian battery, ready to cut down the advancing column and thwart the attack.

American Artillery Opens Fire

American Artillery Opens FireThe order came from Captain Washington, "Forward!" The company rose as one and moved forward at a trot, the men's fingers frozen to the muskets in hand as the icy mix of sleet seared their faces and stung their eyes. The buzz of lead was all around them, and Captain Washington suddenly dropped to a knee, clutching his hands, which streamed blood. Lieutenant Monroe was suddenly in command.

William Washington

William Washington

He charged forward with the company moving at the double, and soon, the Hessian gunners, who were not shot or on the run, were raiding their hands and being marched to captivity. But not before a lead ball tore into Monroe's chest, staggering him and soaking his uniform in blood. Carried to an aid post where Washington was being treated, it was soon evident the ball had torn an artery—a mortal wound.

Monroe led the charge toward the Hessian guns

Monroe led the charge toward the Hessian gunsBut fortune smiled on James Monroe as well as George Washington that morning. As it turned out, Riker, Monroe never learned his first name, was a surgeon. And rare for those times, a very competent surgeon. He was able to close the artery and save the future president from bleeding to death in a battle that had no soldiers killed and just five wounded, including Monroe and Washington. He was promoted to captain for his gallantry.

Battles Lost and WonMonroe recovered fully from his wound and served ably at the Battle of Brandywine and Germantown in the fall of 1777. His performance in those battles gained him a promotion to major and appointment as aide-de-camp to General William Alexander on 20 November 1777. Major Monroe fought at the Battle of Monmouth on 28 June 1778, one of the hardest-fought engagements of the war and the last major battle in the north. But Monroe, who was essentially broke and unable to enlist troops, resigned from the Continental Army on 20 November. This was common. Many Continental Army officers who served honorably left to enter business, return to farming, or engage in politics. Alexander Hamilton is just one example.

Battle of Brandywine

Battle of BrandywineLaw and Politics

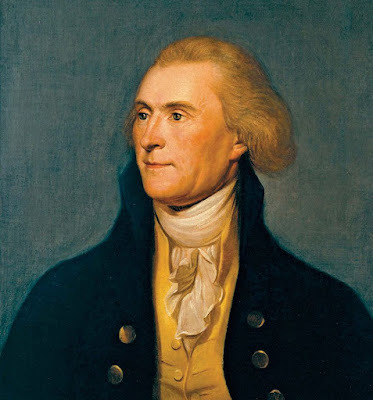

Back in civilian life, Monroe studied law under Governor Thomas Jefferson, a relationship that would impact their lives and the nation's fate. When Charleston fell in 1781, Virginia planned to raise several new regiments, and Monroe was given the rank of lieutenant colonel, although he never served in combat.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

His military career flatlined, but Monroe's political career was on an upward arc—a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, followed by the Confederation Congress. Later, he served in the state constitutional convention. Like many prominent Virginians (Patrick Henry, George Mason), he opposed the proposed constitution for its centralized authority. That did not stop him from taking a seat in the new US Senate in 1790.

DiplomacyMonroe's international and diplomatic career began in 1794 when President George Washington appointed him US Envoy to France. His career in factional politics started three years later when he returned to Virginia and joined the anti-Federalist opposition organized by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. This Virginia triumvirate would profoundly affect US politics and the trajectory of the new nation.

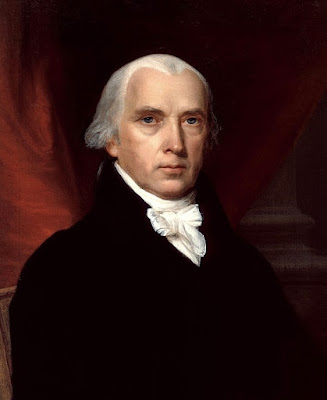

James Madison

James Madison

Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia in 1799. Still, in 1802, President Jefferson appointed him Envoy to France to bolster Robert Livingston's negotiations with Napoleon Bonaparte over the Louisiana Territory, which the US purchased from France the following year for 15 million dollars—doubling the size of the US. Afterward, Monroe served as minister to Great Britain, where he negotiated a commercial treaty in 1806, which the US Senate rejected because it did not address the hot-button topic of the day, impressment.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon BonaparteA Second War with England

After another stint in Virginia politics, Monroe served as President Madison's Secretary of State in 1811. Tensions with Great Britain during that period resulted in the war. The War of 1812 was not going well, so in August 1814, Madison temporarily appointed him Secretary of War. The third member of the Virginia triumvirate, James Monroe, was elected the nation's fifth president in 1816—pretty good teamwork.

British Army Burns Washington in 1814

British Army Burns Washington in 1814Chief Executive

The nation was growing by leaps and bounds when Monroe took office, and a growing sense of American patriotism and exceptionalism, if not nationalism, was everywhere. During this so-called Era of Good Feelings, Monroe and his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, strove to advance America's position on a global stage. A brief war in 1819 against the Florida Seminoles, successfully waged by General Andrew Jackson, led to the Spanish sale of West Florida to the US in 1820, propelling him into a second term.

President James Monroe

President James MonroeThe Era of Good Feelings

In 1819, James Monroe became the first American president since George Washington to travel the nation on a goodwill tour. The nation was expanding west into the Louisiana Territory, the war with Britain was over, and America had stood on its own against the world's only superpower. The Spanish colonies of South America were throwing off the Spanish yoke and forging their own democracies. America seemed the model of the future. With the nation's 50th anniversary just a few years off, the American experiment seemed on a glide path to a prosperous future.

President Washington

President Washington

Not all nations welcomed the success of American democracy and the implosion of the Spanish empire. At the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the autocratic countries Prussia, Austria, and Russia formed a political bond called the Holy Alliance. Holy because they still felt their rulers' authority came from God—the divine right of kings. They now eyed the Spanish colonies. This did not escape the notice of Britain, which had its own interests in the New World and did not welcome intruders.

Congress of Vienna

Congress of ViennaThe Monroe Doctrine

In 1822, Monroe's administration officially recognized the new democracies of America: Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico, after they won independence from Spain. The British approached Monroe with the idea of a joint statement of status quo ante in the New World, but when he ran it by his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, Adams demurred. Why should the US not issue its own policy? After all, Britain was still our rival, and we had just fought a war with them. He offered to help draft a letter to Congress laying out the idea that external powers should not interfere in the affairs of the Americas—no new colonies. Drafted in 1823, it was released in early 1824.

Crafting the Monroe Doctrine

Crafting the Monroe DoctrineVive Lafayette

As all this transpired, Monroe's administration decided to leverage the popularity of the last surviving general of the Continental Army, the Marquis de Lafayette. What better way to highlight American exceptionalism, celebrate the upcoming anniversary, honor a war hero, and send a political shot across the bow of nations like the Holy Alliance? The year-long visit began in August 1824, coinciding with the election of John Quincy Adams, who succeeded Monroe in 1825.

General Lafayette's Visit was a Tour de Force

General Lafayette's Visit was a Tour de Force

The former planter, politician, soldier, and statesman retired to his estate outside Leesburg, Virginia, with his wife, Elizabeth (Kortright) Monroe. President John Quincy Adams and General Lafayette visited the couple just before Lafayette's return to France. They had lots to reminisce over. After all, they were both wounded in service to America—and the young General Lafayette was also present at Trenton, Brandywine, and Monmouth.

Elizabeth (Kortright) Monroe

Elizabeth (Kortright) Monroe

Ironically, the last member of the Virginia triumvirate would move to New York City upon Elizabeth's death in 1830. He resided with his daughter and her family at 63 Prince Street—on Lafayette Square. James Monroe became the third president to die on Independence Day when he succumbed to heart failure and tuberculosis on 4 July 1831.

October 30, 2023

Noble Patriot

The American War for Independence gained the attention of all the European powers, and even the nobility and royalty were, at least initially, enthralled by it as the embodiment of the ideals of The Age of Reason. It did not take long before many of the nobility and upper class were scrambling to join the effort to secure liberty. Soon, names like Steuben, Kosciusko, de Kalb, and Pulaski joined the ranks of the Continental Army. Each made his mark in the Glorious Cause, but none so much as Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Major General Lafayette

Major General Lafayette

Lafayette was born into one of the oldest families in France's aristocracy on 6 September 1757. The young Lafayette had a troubled youth despite a rich lineage, wealth, and privilege. His father, Michel de Lafayette, was struck by a cannonball fighting the British at the Battle of Minden, leaving him an orphan and marquis at two. As was typical of his class, Lafayette was commissioned into a French royal musketeer regiment at thirteen. However, his actual leadership experience was limited to parade and garrison duties when not partaking of the pleasures at court.

Lafayette senior fell at Minden

Lafayette senior fell at MindenHe was early on engaged to Marie Adrienne Françoise, the daughter of a powerful Duc d'Ayen, whom he married at sixteen (she was two years younger). The arranged match also proved a love match, and despite many trials and tribulations, the pair stayed together until she died in 1807. In 1776, the young marquis received a commission as a captain of dragoons, which should have begun his climb up the French military hierarchy, but for events across the ocean.

A Young IdealistLafayette was well-read in the classics and the principles of the Enlightenment, and from an early age, hoped to make a difference for mankind. By 1776, the political friction in America had erupted into open rebellion against the King of England. Like so many others, he followed the events with interest. Unlike so many others, he decided to act on his principles, which he saw enshrined in the sentiments of The Declaration of Independence — he determined to throw his lot in with the Americans and strike a blow for liberty. Equality and fraternity would have to wait, however.

The Declaration of Independence inspired Lafayette

The Declaration of Independence inspired Lafayette

But what to do? Silas Deane, an American politician from Connecticut, represented the American Continental Congress in Paris — in effect, he was an American agent. Many European officers approached Deane to solicit commissions in the Continental Army. Deane's job was to screen them and make referrals of those with bona fide military experience or who provided some other advantage to the American cause. Lafayette's youth and inexperience would have usually precluded a referral, but his pedigree and connections at court, combined with his evident enthusiasm, got him a referral.

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

Lafayette's family, especially his powerful father-in-law, objected to the move. As did his wife. She was pregnant. Influenced by the Duc d'Ayen, the government also refused permission for Lafayette to travel, expressly forbidding it. At the time, Deane was negotiating secret assistance from the French government and overt support. The presence of such a nobleman fighting for America would alarm the British. But the headstrong idealist bucked authority and managed to sneak into Spain, where he eventually boarded the ship Victoire, loaded with ordnance for the American cause. King Louis XVI subsequently declared him an outlaw. How much of this was actual pique at his disobedience or to throw off the British is hard to say, but likely both.

Lafayette escaped France via a subterfugeComing to America

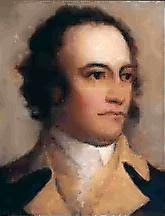

Lafayette escaped France via a subterfugeComing to AmericaThe nineteen-year-old marquis landed in South Carolina in 1777, accompanied by several officers, including Baron Johann de Kalb, a French nobleman who would give his life for the American cause. He then traveled to Philadelphia to claim his promised commission as a major general. Congress hesitated due to his youth and inexperience. Major general was the army's highest rank at the time, and only a few were serving, but because of his connections, they finally appointed him — without command.

Johann de Kalb

Johann de Kalb

Lafayette met Washington for the first time at a reception held in Philadelphia in August 1777 when the commander-in-chief came to the capital to consult with Congress on military matters. The two shook hands in the receiving line and then met privately — bonding almost immediately. Washington was impressed by his enthusiasm and military bearing. He returned to camp with Washington, but his status was still unclear. Lafayette still expected a field command. Was his commission actual or honorary? Washington took him into his "military family" and made him a sort of senior advisor.

Meeting with Washington

Meeting with WashingtonFirst Battle, First Blood, First Winter

The youthful general's mettle was tested the following month at the Battle of Brandywine, where Lafayette received a leg wound while helping rally a regiment fleeing the field. His mentor was pleased. His gallantry earned him a small command. In late November, he led a detachment of 300 infantry in a skirmish against a large force of the vaunted Hessians at Gloucester, New Jersey — repulsing the Germans. His enthusiasm and energy throughout the harsh winter quarters at Valley Forge and his willingness to suffer along with the rest of the army further endeared him to Washington. A father-son relationship had developed. The childless Washington and fatherless Lafayette had a unique bond.

Wounded at Brandywine

Wounded at BrandywineWarmth of Spring