S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 9

April 28, 2019

A Loyal Hillbilly

It has been some time since the Yankee Doodle Spies featured the Loyalists – those very proper Americans who stayed loyal to the King and Britain during the time of political upheaval and blood war. As a rule, these were conservative and very proper folk. But they did have their share of bad asses. One of these was a notorious and stubborn orphan from the back woods of the Carolinas.

Life in the back Hills

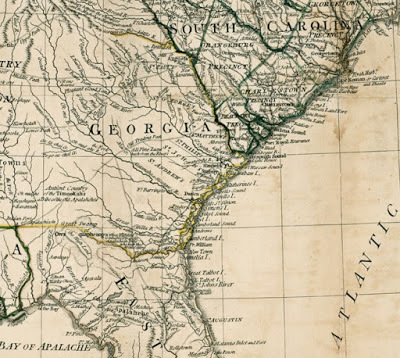

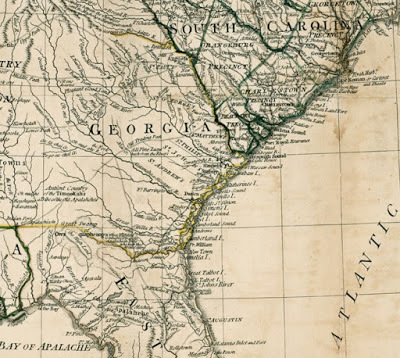

David Fanning was born in Birch Swamp, Amelia County, Virginia in 1755. In July 1764 Fanning was orphaned. As a result the young David was bound to Needham Bryan (Bryant), a county justice in Johnson County, North Carolina. The justice provided for his education but was by Fanning’s account, harsh. Or maybe young David was a bit of handful. So in 1773, when Fanning was 18 and of legal age, he left his guardian and moved to Raeburn’s Creek in the western section of South Carolina. There the young man farmed and traded with the nearby Cherokee Indians. Although life on the frontier was not easy, it was reasonably good for for the enterprising young David Fanning.

Fanning in the back country

Fanning in the back country

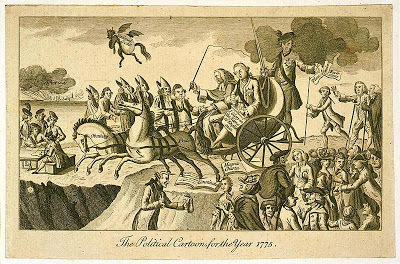

Things began to change when the American Revolution broke out in 1775. At the time, Fanning was a company sergeant in the Upper Saluda militia of South Carolina. Most up country Carolinians were sympathetic to the crown and eyed the lowland planters and merchants with suspicion. There was friction. A delegation from the low lands established a tenuous truce that was broken when a local Loyalist was arrested in November. Soon rumors spread that the rebels were enticing the Indians to their side. That was it. Accosted and robbed by patriot militias, Fanning sided with the local Loyalist faction.

Fighting for the King

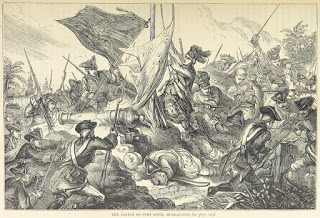

David Fanning served under Major Joseph Robinson in military operations in western South Carolina. He was part of the force that captured a large Patriot garrison at the key Fort Ninety Six in November 1775. But Fanning himself was nearly captured in December that year during the battle at Big Cane Break. Eluding the local patriots, Fanning fled to the Cherokee Indians.

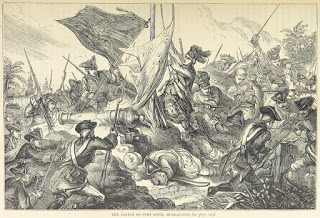

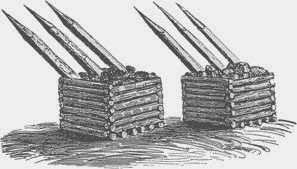

The Fort at Ninety Six

The Fort at Ninety Six

Now wanted as a notorious Loyalist, Fanning was taken prisoner by the rebels in January 1776. This was the first of what be a possible record 14 times during the war! In some of these he was paroled but the cunning and relentless Fanning made numerous harrowing escapes. Between these periods of imprisonment Fanning proved a ruthless, enterprising and aggressive Loyalist officer. He relentlessly led partisan units in almost nonstop skirmishes with the rebel forces in the area. He was a key figure in the little known but decisive back woods civil war that would eventually turn the Carolinians against their British masters and those Loyalist supporters of the crown.

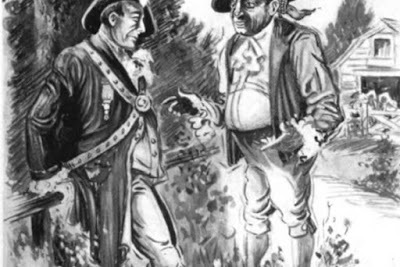

David Fanning made numerous escapes

David Fanning made numerous escapes

The Loyalists take a Knee

But by August 1779, most of the Loyalists were losing heart. They had suffered heavy losses and it looked like the south would be lost to the crown. Many of them, including Fanning, agreed to a conditional pardon by Governor John Rutledge. This kept Fanning out of the fray for several months. Fanning’s numerous escapades had taken a toll on him. By his own admission he was worn out, frazzled and skeletal in appearance. His many wounds and injuries had taken their toll. Fanning had even agreed to guide patriot militia units in the back country as part of his pardon.

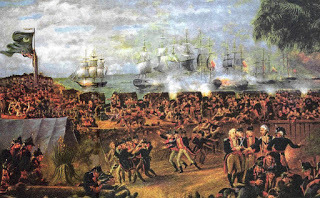

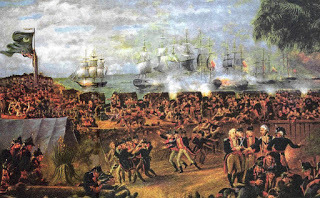

The British capture of Charleston marked a new dynamic in the

The British capture of Charleston marked a new dynamic in the

southern theater of operations

But things changed when the British shifted their strategy to the south. A British force besieged Charleston and its fall and occupation led to a British move to hold all the key positions in the state. The decisive defeat of the Continental forces under General Horatio Gates by British General Lord Cornwallis made it apparent that the British were here to stay.

The South in Flames

These events reignited the ardor of the Loyalists and they flocked to the colors once more – Fanning with them. Bloody civil war once more erupted across the southern backwoods and this time Fanning was at the forefront of the Loyalist cause. With South Carolina under the the British heel and Cornwallis’s army in control, Fanning and other Loyalist partisan leaders now had a steady stream of weapons and other supplies. With things looking dark for the rebels, Loyalist bands were easy to recruit and equip.

The Southern Theater would prove Decisive

The Southern Theater would prove Decisive

and violent

This high water mark of Loyalist ascendancy did not last long. One of the American cause’s best generals was sent south to instill new energy into the southern theater. Nathanael Green proved a

persistent and classic resistance leader. Giving ground when he had to, making stands, successful and not, but keeping his army in the field and active. Cornwallis had to destroy his army. He hurt it. But could not destroy it.

Nathanael Greene's arrival turned the

Nathanael Greene's arrival turned the

tide in the Southern Theater

The West is Lost Cornwallis would fail to destroy

Cornwallis would fail to destroy

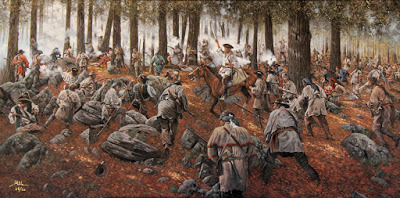

Greene and make a grave mistakeIn his zeal to pursue the resisting rebel army, Cornwallis used Loyalist units to protect his western flank from patriot militias threatening it. He sent a large Loyalist detachment under his most experienced counter guerrilla leader, Major Patrick Ferguson, to disperse the back woods patriots. Ferguson did not know the locals were being reinforced by a large contingent of "Over Mountain men." Ferguson got caught on King's Mountain. Surrounded, he stood and fought the hated rebels. The battle of Kings Mountain was essentially Loyalist versus patriot affair. The crushing of the Loyalists changed the southern theater in the west to the rebel’s advantage.

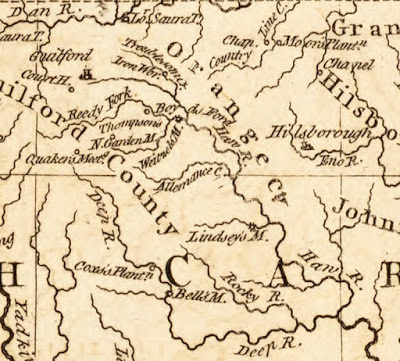

With things looking bleak for Loyalists in the west, Fanning took his band and headed east and north to Deep River North Carolina where he conducted operations against local patriots. His success led to his appointment to Colonel of Loyalist militia of Chatham and Randolph counties. For the next several months Fanning ruthlessly launched raids throughout western North Carolina. He now had become one of the most feared Loyalist partisan commanders in the theater.

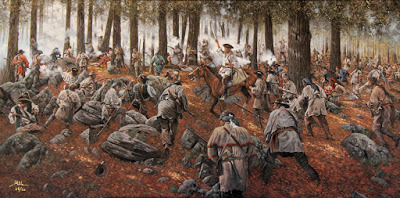

American victory Kings Mountain crushed loyal opposition

American victory Kings Mountain crushed loyal opposition

in the western Carolinas

Guerrilla Days in Carolina

Fanning was a classic guerrilla leader. He would move fast and hit hard, sometimes with as few as 12 men. Many of these raids resulted in the capture and ransom or parole of leading patriot sympathizers and political figures. He was involved in some 36 skirmishes in 1781 alone. One was a raid on a session of court in Chatham County. Fanning’s partisans took 53 prisoners, including court officials, militia officers, and members of the North Carolina General Assembly.

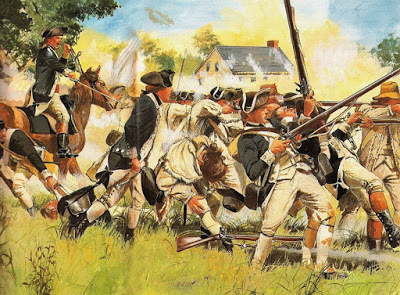

Fanning's Loyalist militia raised Cain among the patriots

Fanning's Loyalist militia raised Cain among the patriots

Fanning led the Loyalist militia at the battle at the House in the Horseshoe in the summer of 1781 where he forced the surrender of a force of patriot militia. By the end of the summer of 1781, Fanning's infamy had attracted a force of approximately 950 Loyalist men to his command. He was ready for the big time.

Conventional War Success… and Failure

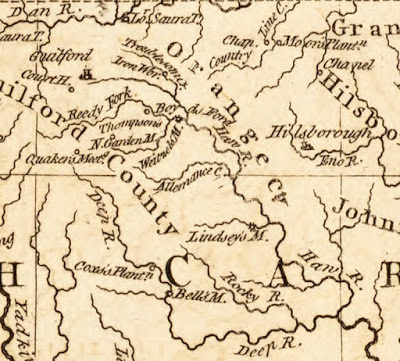

With a large force in hand, Fanning was intent on using it. And he did. On 12 September 1781 he led a force of almost 1,000 Loyalists in a surprise assault against the rebel forces at Hillsboro, North Carolina. Hillsboro at the time was the main patriot base in the region and some time capital. He overwhelmed the patriot defenses and captured 200 prisoners along with Governor Thomas Burke. Hillsboro proved his most notable success in the war.

After victory at Hillsboro Fanning is ambushed

After victory at Hillsboro Fanning is ambushed

at Lindley's Mill

But Fanning’s sweet success as a conventional force commander was not long lived. He led his victorious column, along with prisoners, back to Wilmington. As he reached the area around Lindley’s Mill a rebel force of 400 under Brigadier General John Butler launched a fierce attack on Fanning’s men. The fighting was hard and the surprised Loyalist force would have crumbled but for Fanning’s personal leadership. He fended off Butler’s attacks and managed to get his column to Wilmington but was himself badly wounded. Thanks to Fanning's resolve, the hapless Governor Burke was imprisoned by the British Army on James Island near Charleston, South Carolina.

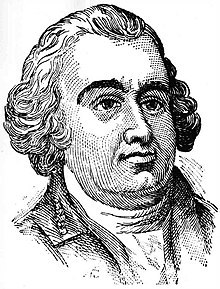

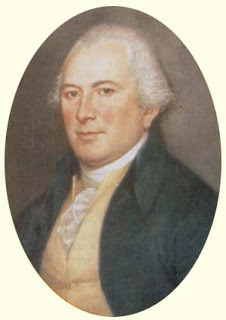

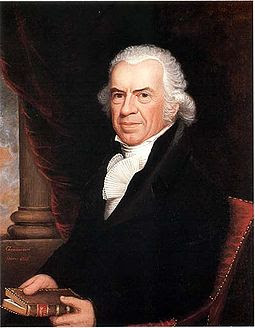

NC Gov Thomas Burke

Decline in Fortunes

In November 1781 the British withdrew from Wilmington on the news of Yorktown. The war seemed over but the Loyalists who remained with the colors would not go down so easily. The bitter civil war left too many desperate for revenge and unwilling to compromise or submit to the rebels they so despised. Fanning was one of them. He continued to lead partisan bands against the patriots. He made a series of bitter attacks on patriot settlements that continued into 1782 – a year that most of us think as one of quiet as the final treaty was negotiate.

Loyalist Provisionals

Loyalist Provisionals

But Fanning was worn and weary. And the canny backwoodsman saw the hand writing on the wall. It was time to return to a normal life. As a first step in attempting to establish that life, he married Sarah Carr, a 16-year-old young woman from the settlement of Deep River, North Carolina.

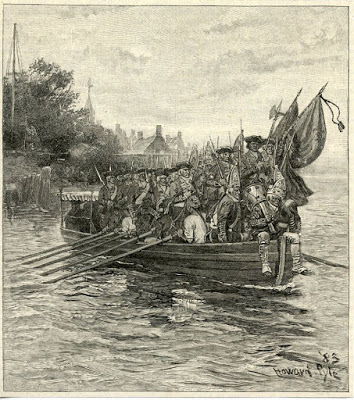

Charleston Harbor would provide many Loyalists'

Charleston Harbor would provide many Loyalists'

final glimpse of the country the fought so hard to keep loyal

Fanning finally accepted a conditional truce from the local American government and agreed to suspend further military action. Now resigned to his fate and that of his cause, Fanning and his young bride went to Charleston where he was deported, with other Loyalists, to British Florida. Fanning’s success against the patriots and his notoriety as a guerrilla caused the North Carolina legislature to ban him from ever entering the state. This seems a bitter memorial to his accomplishments.

Oh Canada!

Like so many other members of the Loyalist diaspora, Fanning did not remain long in his first refuge. After a few months he made his way to New Brunswick, Canada – one of thousands who went there for a better life under the crown. His natural leadership put him in the legislative assembly until he was caught up in a shocking scandal in 1800. Fanning was charged and convicted of rape of 15-year old Sarah London and sentenced to be hanged. The evidence against him was scanty – essentially her testimony, but Fanning had few friends among his Loyalist peers. The combative man from the hills had brought his feisty ways to Canada. He appealed the sentence and was instead of hanging he was banished from New Brunswick.

Canada provided refuge for many Loyalists

Canada provided refuge for many Loyalists

after the American Revolution

Fanning proved resourceful when given a second chance. He moved to the small port town of Digby, Nova Scotia. Fanning spent the remainder of his life in Digby. He built a comfortable house and engaged in farming, fishing, and shipbuilding. He still wanted to return to New Brunswick to settle his financial affairs but his petitions to Thomas Carleton, Provincial Secretary Jonathan Odell, and other officials fell on deaf ears.

Digby, Nova Scotia was one of many

Digby, Nova Scotia was one of many

Loyalist landing places in Canada

In any case, considering his eight years of fighting and mayhem,the staunch and loyal David Fanning, managed to live to a reasonably ripe old age. He died on 14 March 1825.

A Loyal Life well Lived?

The tough and wiry Fanning was stubborn and determined man in war and peace. As a Loyalist militia leader he proved zealous and often brilliantly effective. But he was not gentile nor was he that type of intellectual loyalist, refined and smug, who sat out the war in the secure comforts of New York, Charleston, or England. Instead, Fanning fought tenaciously, fiercely, and occasionally cruelly against ex-friends and neighbors. Rather than endearing him, his successes made him unpopular with the privileged Loyalist gentry of New Brunswick.

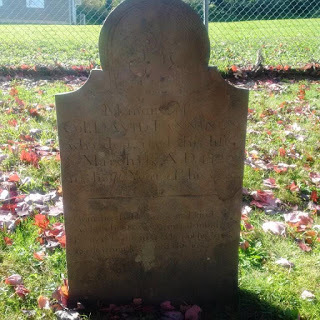

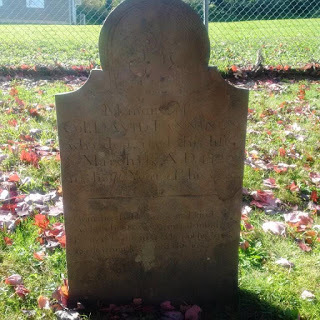

But the last laugh and irony from this angry and combative former hillbilly was his epitaph in the Trinity churchyard at Digby: “Humane, affable, gentle, and kind – A plain honest open moral mind.”

Colonel David Fanning resting place

Colonel David Fanning resting place

in Digby, Nova Scotia

In my take it should have read: “I’m Loyal – Love it or Shove it.”

Life in the back Hills

David Fanning was born in Birch Swamp, Amelia County, Virginia in 1755. In July 1764 Fanning was orphaned. As a result the young David was bound to Needham Bryan (Bryant), a county justice in Johnson County, North Carolina. The justice provided for his education but was by Fanning’s account, harsh. Or maybe young David was a bit of handful. So in 1773, when Fanning was 18 and of legal age, he left his guardian and moved to Raeburn’s Creek in the western section of South Carolina. There the young man farmed and traded with the nearby Cherokee Indians. Although life on the frontier was not easy, it was reasonably good for for the enterprising young David Fanning.

Fanning in the back country

Fanning in the back countryThings began to change when the American Revolution broke out in 1775. At the time, Fanning was a company sergeant in the Upper Saluda militia of South Carolina. Most up country Carolinians were sympathetic to the crown and eyed the lowland planters and merchants with suspicion. There was friction. A delegation from the low lands established a tenuous truce that was broken when a local Loyalist was arrested in November. Soon rumors spread that the rebels were enticing the Indians to their side. That was it. Accosted and robbed by patriot militias, Fanning sided with the local Loyalist faction.

Fighting for the King

David Fanning served under Major Joseph Robinson in military operations in western South Carolina. He was part of the force that captured a large Patriot garrison at the key Fort Ninety Six in November 1775. But Fanning himself was nearly captured in December that year during the battle at Big Cane Break. Eluding the local patriots, Fanning fled to the Cherokee Indians.

The Fort at Ninety Six

The Fort at Ninety SixNow wanted as a notorious Loyalist, Fanning was taken prisoner by the rebels in January 1776. This was the first of what be a possible record 14 times during the war! In some of these he was paroled but the cunning and relentless Fanning made numerous harrowing escapes. Between these periods of imprisonment Fanning proved a ruthless, enterprising and aggressive Loyalist officer. He relentlessly led partisan units in almost nonstop skirmishes with the rebel forces in the area. He was a key figure in the little known but decisive back woods civil war that would eventually turn the Carolinians against their British masters and those Loyalist supporters of the crown.

David Fanning made numerous escapes

David Fanning made numerous escapesThe Loyalists take a Knee

But by August 1779, most of the Loyalists were losing heart. They had suffered heavy losses and it looked like the south would be lost to the crown. Many of them, including Fanning, agreed to a conditional pardon by Governor John Rutledge. This kept Fanning out of the fray for several months. Fanning’s numerous escapades had taken a toll on him. By his own admission he was worn out, frazzled and skeletal in appearance. His many wounds and injuries had taken their toll. Fanning had even agreed to guide patriot militia units in the back country as part of his pardon.

The British capture of Charleston marked a new dynamic in the

The British capture of Charleston marked a new dynamic in thesouthern theater of operations

But things changed when the British shifted their strategy to the south. A British force besieged Charleston and its fall and occupation led to a British move to hold all the key positions in the state. The decisive defeat of the Continental forces under General Horatio Gates by British General Lord Cornwallis made it apparent that the British were here to stay.

The South in Flames

These events reignited the ardor of the Loyalists and they flocked to the colors once more – Fanning with them. Bloody civil war once more erupted across the southern backwoods and this time Fanning was at the forefront of the Loyalist cause. With South Carolina under the the British heel and Cornwallis’s army in control, Fanning and other Loyalist partisan leaders now had a steady stream of weapons and other supplies. With things looking dark for the rebels, Loyalist bands were easy to recruit and equip.

The Southern Theater would prove Decisive

The Southern Theater would prove Decisiveand violent

This high water mark of Loyalist ascendancy did not last long. One of the American cause’s best generals was sent south to instill new energy into the southern theater. Nathanael Green proved a

persistent and classic resistance leader. Giving ground when he had to, making stands, successful and not, but keeping his army in the field and active. Cornwallis had to destroy his army. He hurt it. But could not destroy it.

Nathanael Greene's arrival turned the

Nathanael Greene's arrival turned thetide in the Southern Theater

The West is Lost

Cornwallis would fail to destroy

Cornwallis would fail to destroyGreene and make a grave mistakeIn his zeal to pursue the resisting rebel army, Cornwallis used Loyalist units to protect his western flank from patriot militias threatening it. He sent a large Loyalist detachment under his most experienced counter guerrilla leader, Major Patrick Ferguson, to disperse the back woods patriots. Ferguson did not know the locals were being reinforced by a large contingent of "Over Mountain men." Ferguson got caught on King's Mountain. Surrounded, he stood and fought the hated rebels. The battle of Kings Mountain was essentially Loyalist versus patriot affair. The crushing of the Loyalists changed the southern theater in the west to the rebel’s advantage.

With things looking bleak for Loyalists in the west, Fanning took his band and headed east and north to Deep River North Carolina where he conducted operations against local patriots. His success led to his appointment to Colonel of Loyalist militia of Chatham and Randolph counties. For the next several months Fanning ruthlessly launched raids throughout western North Carolina. He now had become one of the most feared Loyalist partisan commanders in the theater.

American victory Kings Mountain crushed loyal opposition

American victory Kings Mountain crushed loyal oppositionin the western Carolinas

Guerrilla Days in Carolina

Fanning was a classic guerrilla leader. He would move fast and hit hard, sometimes with as few as 12 men. Many of these raids resulted in the capture and ransom or parole of leading patriot sympathizers and political figures. He was involved in some 36 skirmishes in 1781 alone. One was a raid on a session of court in Chatham County. Fanning’s partisans took 53 prisoners, including court officials, militia officers, and members of the North Carolina General Assembly.

Fanning's Loyalist militia raised Cain among the patriots

Fanning's Loyalist militia raised Cain among the patriotsFanning led the Loyalist militia at the battle at the House in the Horseshoe in the summer of 1781 where he forced the surrender of a force of patriot militia. By the end of the summer of 1781, Fanning's infamy had attracted a force of approximately 950 Loyalist men to his command. He was ready for the big time.

Conventional War Success… and Failure

With a large force in hand, Fanning was intent on using it. And he did. On 12 September 1781 he led a force of almost 1,000 Loyalists in a surprise assault against the rebel forces at Hillsboro, North Carolina. Hillsboro at the time was the main patriot base in the region and some time capital. He overwhelmed the patriot defenses and captured 200 prisoners along with Governor Thomas Burke. Hillsboro proved his most notable success in the war.

After victory at Hillsboro Fanning is ambushed

After victory at Hillsboro Fanning is ambushedat Lindley's Mill

But Fanning’s sweet success as a conventional force commander was not long lived. He led his victorious column, along with prisoners, back to Wilmington. As he reached the area around Lindley’s Mill a rebel force of 400 under Brigadier General John Butler launched a fierce attack on Fanning’s men. The fighting was hard and the surprised Loyalist force would have crumbled but for Fanning’s personal leadership. He fended off Butler’s attacks and managed to get his column to Wilmington but was himself badly wounded. Thanks to Fanning's resolve, the hapless Governor Burke was imprisoned by the British Army on James Island near Charleston, South Carolina.

NC Gov Thomas Burke

Decline in Fortunes

In November 1781 the British withdrew from Wilmington on the news of Yorktown. The war seemed over but the Loyalists who remained with the colors would not go down so easily. The bitter civil war left too many desperate for revenge and unwilling to compromise or submit to the rebels they so despised. Fanning was one of them. He continued to lead partisan bands against the patriots. He made a series of bitter attacks on patriot settlements that continued into 1782 – a year that most of us think as one of quiet as the final treaty was negotiate.

Loyalist Provisionals

Loyalist ProvisionalsBut Fanning was worn and weary. And the canny backwoodsman saw the hand writing on the wall. It was time to return to a normal life. As a first step in attempting to establish that life, he married Sarah Carr, a 16-year-old young woman from the settlement of Deep River, North Carolina.

Charleston Harbor would provide many Loyalists'

Charleston Harbor would provide many Loyalists'final glimpse of the country the fought so hard to keep loyal

Fanning finally accepted a conditional truce from the local American government and agreed to suspend further military action. Now resigned to his fate and that of his cause, Fanning and his young bride went to Charleston where he was deported, with other Loyalists, to British Florida. Fanning’s success against the patriots and his notoriety as a guerrilla caused the North Carolina legislature to ban him from ever entering the state. This seems a bitter memorial to his accomplishments.

Oh Canada!

Like so many other members of the Loyalist diaspora, Fanning did not remain long in his first refuge. After a few months he made his way to New Brunswick, Canada – one of thousands who went there for a better life under the crown. His natural leadership put him in the legislative assembly until he was caught up in a shocking scandal in 1800. Fanning was charged and convicted of rape of 15-year old Sarah London and sentenced to be hanged. The evidence against him was scanty – essentially her testimony, but Fanning had few friends among his Loyalist peers. The combative man from the hills had brought his feisty ways to Canada. He appealed the sentence and was instead of hanging he was banished from New Brunswick.

Canada provided refuge for many Loyalists

Canada provided refuge for many Loyalistsafter the American Revolution

Fanning proved resourceful when given a second chance. He moved to the small port town of Digby, Nova Scotia. Fanning spent the remainder of his life in Digby. He built a comfortable house and engaged in farming, fishing, and shipbuilding. He still wanted to return to New Brunswick to settle his financial affairs but his petitions to Thomas Carleton, Provincial Secretary Jonathan Odell, and other officials fell on deaf ears.

Digby, Nova Scotia was one of many

Digby, Nova Scotia was one of manyLoyalist landing places in Canada

In any case, considering his eight years of fighting and mayhem,the staunch and loyal David Fanning, managed to live to a reasonably ripe old age. He died on 14 March 1825.

A Loyal Life well Lived?

The tough and wiry Fanning was stubborn and determined man in war and peace. As a Loyalist militia leader he proved zealous and often brilliantly effective. But he was not gentile nor was he that type of intellectual loyalist, refined and smug, who sat out the war in the secure comforts of New York, Charleston, or England. Instead, Fanning fought tenaciously, fiercely, and occasionally cruelly against ex-friends and neighbors. Rather than endearing him, his successes made him unpopular with the privileged Loyalist gentry of New Brunswick.

But the last laugh and irony from this angry and combative former hillbilly was his epitaph in the Trinity churchyard at Digby: “Humane, affable, gentle, and kind – A plain honest open moral mind.”

Colonel David Fanning resting place

Colonel David Fanning resting placein Digby, Nova Scotia

In my take it should have read: “I’m Loyal – Love it or Shove it.”

Published on April 28, 2019 08:27

March 31, 2019

The Legend and the Legion

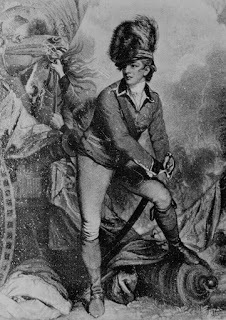

Polish Bad Ass

In a war that saw many "bad asses" serve on both sides, Kasimierz (Casimir) Pulaski has to be ranked near the top. And if not for a stray round of grape, he may have fought his way to the top of the list. He fought for freedom on two continents and remained undaunted throughout a career of professional set backs. Although he never saw his homeland freed, he managed to help nudge a nascent republic to a hard fought freedom. Something tells me he was glad to sacrifice himself in a cause that changed the world.

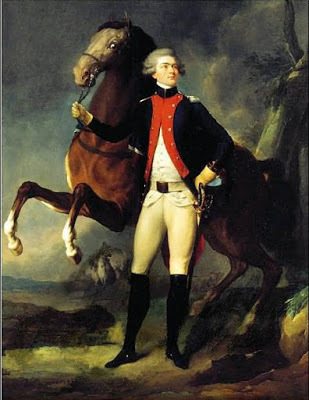

Bad Ass on two continents

Bad Ass on two continents

Lineage

Kasimierz (Casimir) Pulaski was born in Podolia, Poland on 4 March 1747, son of Count Josef Pulaski, a member of the minor Polish gentry. He came from a family of knightly traditions - mostly warfare. Pulaski’s family fought under Poland’s King John III Sobieski against the Turks in the 17th century – a campaign that saved Europe. At the siege of Vienna in September 1683, the decisive battle of the campaign, the famed Polish winged hussars, heavily armored lancers, charged home against a mighty Turkish host and sent it in a retreat that would eventually begin the long decline of the Ottoman Empire. It was from the line of these bold horsemen that Pulaski sprang.

Charge of Winged Hussars at Vienna

Charge of Winged Hussars at Vienna

Fighting For Poland

And Poland needed men of fighting blood. For by the time of Kasimierz’s birth, the once mighty Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth was under intense political pressure from its increasingly powerful neighbors. Austria, Prussia and Russia had managed to manipulate the weak King Stanislaw II. Pulaski was well educated, and in 1768 he joined the Confederation of the Bars, established by his father to fight the Russians. He fought in several successful actions, including the famous defense of the monastery fortress of Czestochowa in 1771, but eventually suffered defeat and was exiled to Turkey. As a result, Poland went through its first partition (of three). Pulaski spent his years in Turkey trying to stir them against their common threat, the Russians. When this failed he sailed for France, now penniless and broken. But then he heard of the American Revolution!

Pulaski leading forces of the Bar Confederation

Pulaski leading forces of the Bar Confederation

at Czestochowa in 1771

Fighting for Freedom

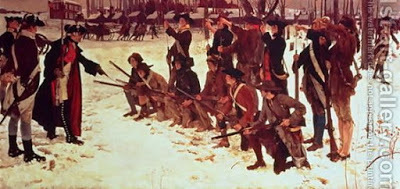

If he could not free Poland, he would offer his sword for a new cause for freedom. Pulaski approached the American agents in France, Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin, seeking a commission in the Continental Army. Franklin provided him a letter of introduction and the excited nobleman sailed for Boston in July 1777. After conferring with members of the Continental Congress, the young Pole volunteered his services to General George Washington as an aide. He served beside Washington at the Battle of Brandywine on 11 September 1777. Although this proved a defeat for the Americans, quick and decisive actions by Pulaski may have saved the Continental Army from complete destruction. He fought at Germantown covering Washington's retreat, patrolled the area around Valley Forge during the winter, moved to Trenton and then, under Gen. Anthony Wayne, he fought the British at Haddersfield, New Jersey.

Pulaski was one of many foreign officers who

Pulaski was one of many foreign officers who

served the cause of freedom

Failure to Communicate

Nobody questioned Pulaski’s heroism under fire, nor his commitment to the Cause, but he was quarrelsome, headstrong and overly sensitive to matters of rank – as were many of the Americans. The difficulties arising from his hot temper were compounded by his lack of English – he used French often to communicate. His feuding and fussing came to a head when he had a falling out in the spring of 1778 with General Anthony Wayne, no slouch himself when came to anger. Pulaski threatened to resign over it. Washington convinced him to stay with the army and petitioned Congress for a separate command for him. This was granted and on 28 March 1778 Congress authorized Kazimierz Pulaski to raise a unit soon to be named the Pulaski Legion.

I am Legion

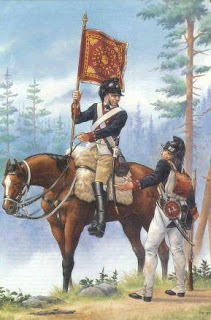

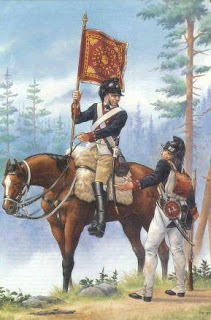

The Legion's BannerA legion is an archaic term for a combined arms force. During the Revolutionary War this usually meant infantry and cavalry – but occasionally some light cannon were in the mix. The Pulaski Legion was recruited around Baltimore and was comprised of Americans, German, Frenchmen, Irishmen, and Poles. It flew a red banner. Pulaski’s unit initially numbered 200 infantry and 68 cavalry armed, wait for it… lances. Polish cavalry were renowned for their lancer units, which usually charged home to victory over Cossacks, Russians, Turks and Germans. No wonder the gallant Pole created his own version.

The Legion's BannerA legion is an archaic term for a combined arms force. During the Revolutionary War this usually meant infantry and cavalry – but occasionally some light cannon were in the mix. The Pulaski Legion was recruited around Baltimore and was comprised of Americans, German, Frenchmen, Irishmen, and Poles. It flew a red banner. Pulaski’s unit initially numbered 200 infantry and 68 cavalry armed, wait for it… lances. Polish cavalry were renowned for their lancer units, which usually charged home to victory over Cossacks, Russians, Turks and Germans. No wonder the gallant Pole created his own version.

The Legion would see immediate action along the New Jersey coast where it tasted first blood at Egg Harbor on 4 October 1778. Unfortunately, it did not cover itself in glory. The famed British Major Patrick Ferguson led his own legion and surprised Pulaski’s force in camp. They took heavy casualties. Turns out one of Pulaski’s men deserted and provided the British intelligence on the unit’s dispositions.

Major Patrick Ferguson

Major Patrick Ferguson

Washington sent Pulaski’s unit to a quiet area to recuperate. The Legion garrisoned the upper Delaware to protect against Indian raids. Pulaski’s honor was affronted and he fumed over the assignment. His flinty ways led to another incident. Pulaski court martialed his subordinate, Major Stephen Moylan over an alleged slight. He also threatened once more to resign. With the patience of Job, General Washington interceded once more. He reassigned the quarrelsome Pole and his Legion to the Southern theater.

Cavalry and Infantry of the Legion

Cavalry and Infantry of the Legion

Since the center of gravity had shifted south, this action both removed Pulaski from under Washington’s direct supervision. But it was sure to give him real fighting to match his combative ways.

For the South

So in the spring of 1779, Pulaski and his Legion joined American forces defending Charleston, South Carolina. He arrived in time for a whirlwind! The British strategy had shifted to the south, hoping an overwhelming show of force would break the will of the patriots in the region. In late 1778 they had taken Savannah, Georgia. Now they aimed to slide north to the Carolinas.

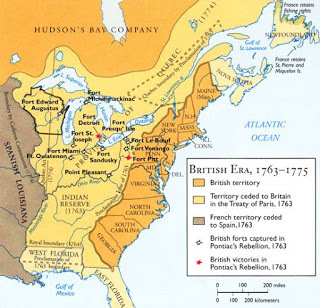

The British Strategy turned South to separate

The British Strategy turned South to separate

the Carolinas and Georgia from the rebellion

The British under General Augustin Prevost threatened the southern capital and threatened a siege. In a bold move, Pulaski attacked the British on 11 May 1779. Greatly outnumbered, the Legion was thrashed and repulsed. When he returned to the city, he learned that morale was low and patriot resolve ebbing. The unflinching Pulaski encouraged the inhabitants not to surrender so easily. They held out long enough for the American southern commander, General Benjamin Lincoln, to arrive with reinforcements. Pulaski frequently suffered from bouts of malaria acquired in the south’s hot swampy coastal lowlands. But the stubborn and proud officer refused to leave active service.

At the beginning of September, General Lincoln prepared to launch an attempt to retake Savannah with long awaited French assistance. Cavalry would play a role and Pulaski was sent to Augusta, Georgia to join General Lachlan McIntosh. Lachlan and Pulaski’s force covered the advance of Lincoln’s offensive. Pulaski captured a British outpost near Ogeechee River. His Legion then acted as an advance guard for the allied French units under Admiral Charles Hector, Comte d'Estaing.

But d’Estaing was on a short timeline. Reliant on his naval support, and with hurricane season fast approaching, he decided to stake everything on a surprise attack on 9 October 1779. Pulaski was given command of the entire combined Franco-American cavalry force. Pulaski, ever impetuous, launched a full scale cavalry charge against heavily defended British fortification. But Pulaski took a ball of grape shot and the assault was soundly defeated.

Pulaski mortally wounded by grape shot

Pulaski mortally wounded by grape shot

Mortally wounded, Pulaski was moved to a transport ship Wasp in the hope of getting him to Charleston. But the gallant Pulaski died two days later – 11 February 1779. They buried him at sea. And his Legion? His men were transferred under Colonel Charles Armand’s legion for the remainder of the war.

Pulaski monument in his native Poland

Pulaski monument in his native Poland

Legacy

Despite his haughty and quarrelsome character, Casimir Pulaski is remembered in many ways. Of course, in Poland, as a man who fought for freedom on two continents and bears the title "Soldier of Liberty." In America, his service and sacrifices are commemorated by the many streets, bridges, counties, and towns that bear his name.

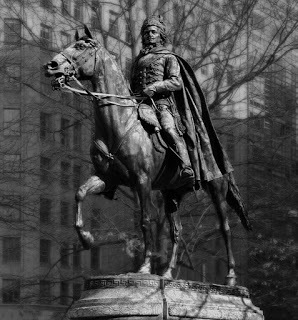

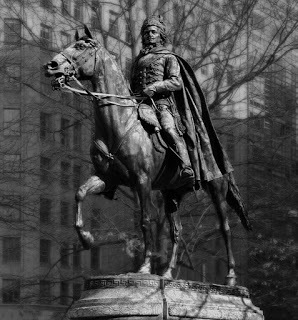

Monument to Pulaski in Washington, DC

Monument to Pulaski in Washington, DC

Pulaski gave the last full measure outside Savannah, Georgia, and there a large monument commemorates his sacrifice fighting for the city during the American Revolution. In 1833, the new fort being constructed on Cockspur Island outside of Savannah was christened Fort Pulaski in honor of Casimir Pulaski.

Fort Pulaski

Fort Pulaski

Above all, he is the man who provided the American colonists with their first true legion on horseback. The US cavalry later adopted its guidons in red and white, the national colors of Poland, to honor the boldest cavalryman of the War for Independence, and forever cementing his place as "The Father of the American Cavalry."

In a war that saw many "bad asses" serve on both sides, Kasimierz (Casimir) Pulaski has to be ranked near the top. And if not for a stray round of grape, he may have fought his way to the top of the list. He fought for freedom on two continents and remained undaunted throughout a career of professional set backs. Although he never saw his homeland freed, he managed to help nudge a nascent republic to a hard fought freedom. Something tells me he was glad to sacrifice himself in a cause that changed the world.

Bad Ass on two continents

Bad Ass on two continentsLineage

Kasimierz (Casimir) Pulaski was born in Podolia, Poland on 4 March 1747, son of Count Josef Pulaski, a member of the minor Polish gentry. He came from a family of knightly traditions - mostly warfare. Pulaski’s family fought under Poland’s King John III Sobieski against the Turks in the 17th century – a campaign that saved Europe. At the siege of Vienna in September 1683, the decisive battle of the campaign, the famed Polish winged hussars, heavily armored lancers, charged home against a mighty Turkish host and sent it in a retreat that would eventually begin the long decline of the Ottoman Empire. It was from the line of these bold horsemen that Pulaski sprang.

Charge of Winged Hussars at Vienna

Charge of Winged Hussars at ViennaFighting For Poland

And Poland needed men of fighting blood. For by the time of Kasimierz’s birth, the once mighty Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth was under intense political pressure from its increasingly powerful neighbors. Austria, Prussia and Russia had managed to manipulate the weak King Stanislaw II. Pulaski was well educated, and in 1768 he joined the Confederation of the Bars, established by his father to fight the Russians. He fought in several successful actions, including the famous defense of the monastery fortress of Czestochowa in 1771, but eventually suffered defeat and was exiled to Turkey. As a result, Poland went through its first partition (of three). Pulaski spent his years in Turkey trying to stir them against their common threat, the Russians. When this failed he sailed for France, now penniless and broken. But then he heard of the American Revolution!

Pulaski leading forces of the Bar Confederation

Pulaski leading forces of the Bar Confederationat Czestochowa in 1771

Fighting for Freedom

If he could not free Poland, he would offer his sword for a new cause for freedom. Pulaski approached the American agents in France, Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin, seeking a commission in the Continental Army. Franklin provided him a letter of introduction and the excited nobleman sailed for Boston in July 1777. After conferring with members of the Continental Congress, the young Pole volunteered his services to General George Washington as an aide. He served beside Washington at the Battle of Brandywine on 11 September 1777. Although this proved a defeat for the Americans, quick and decisive actions by Pulaski may have saved the Continental Army from complete destruction. He fought at Germantown covering Washington's retreat, patrolled the area around Valley Forge during the winter, moved to Trenton and then, under Gen. Anthony Wayne, he fought the British at Haddersfield, New Jersey.

Pulaski was one of many foreign officers who

Pulaski was one of many foreign officers whoserved the cause of freedom

Failure to Communicate

Nobody questioned Pulaski’s heroism under fire, nor his commitment to the Cause, but he was quarrelsome, headstrong and overly sensitive to matters of rank – as were many of the Americans. The difficulties arising from his hot temper were compounded by his lack of English – he used French often to communicate. His feuding and fussing came to a head when he had a falling out in the spring of 1778 with General Anthony Wayne, no slouch himself when came to anger. Pulaski threatened to resign over it. Washington convinced him to stay with the army and petitioned Congress for a separate command for him. This was granted and on 28 March 1778 Congress authorized Kazimierz Pulaski to raise a unit soon to be named the Pulaski Legion.

I am Legion

The Legion's BannerA legion is an archaic term for a combined arms force. During the Revolutionary War this usually meant infantry and cavalry – but occasionally some light cannon were in the mix. The Pulaski Legion was recruited around Baltimore and was comprised of Americans, German, Frenchmen, Irishmen, and Poles. It flew a red banner. Pulaski’s unit initially numbered 200 infantry and 68 cavalry armed, wait for it… lances. Polish cavalry were renowned for their lancer units, which usually charged home to victory over Cossacks, Russians, Turks and Germans. No wonder the gallant Pole created his own version.

The Legion's BannerA legion is an archaic term for a combined arms force. During the Revolutionary War this usually meant infantry and cavalry – but occasionally some light cannon were in the mix. The Pulaski Legion was recruited around Baltimore and was comprised of Americans, German, Frenchmen, Irishmen, and Poles. It flew a red banner. Pulaski’s unit initially numbered 200 infantry and 68 cavalry armed, wait for it… lances. Polish cavalry were renowned for their lancer units, which usually charged home to victory over Cossacks, Russians, Turks and Germans. No wonder the gallant Pole created his own version.The Legion would see immediate action along the New Jersey coast where it tasted first blood at Egg Harbor on 4 October 1778. Unfortunately, it did not cover itself in glory. The famed British Major Patrick Ferguson led his own legion and surprised Pulaski’s force in camp. They took heavy casualties. Turns out one of Pulaski’s men deserted and provided the British intelligence on the unit’s dispositions.

Major Patrick Ferguson

Major Patrick FergusonWashington sent Pulaski’s unit to a quiet area to recuperate. The Legion garrisoned the upper Delaware to protect against Indian raids. Pulaski’s honor was affronted and he fumed over the assignment. His flinty ways led to another incident. Pulaski court martialed his subordinate, Major Stephen Moylan over an alleged slight. He also threatened once more to resign. With the patience of Job, General Washington interceded once more. He reassigned the quarrelsome Pole and his Legion to the Southern theater.

Cavalry and Infantry of the Legion

Cavalry and Infantry of the LegionSince the center of gravity had shifted south, this action both removed Pulaski from under Washington’s direct supervision. But it was sure to give him real fighting to match his combative ways.

For the South

So in the spring of 1779, Pulaski and his Legion joined American forces defending Charleston, South Carolina. He arrived in time for a whirlwind! The British strategy had shifted to the south, hoping an overwhelming show of force would break the will of the patriots in the region. In late 1778 they had taken Savannah, Georgia. Now they aimed to slide north to the Carolinas.

The British Strategy turned South to separate

The British Strategy turned South to separatethe Carolinas and Georgia from the rebellion

The British under General Augustin Prevost threatened the southern capital and threatened a siege. In a bold move, Pulaski attacked the British on 11 May 1779. Greatly outnumbered, the Legion was thrashed and repulsed. When he returned to the city, he learned that morale was low and patriot resolve ebbing. The unflinching Pulaski encouraged the inhabitants not to surrender so easily. They held out long enough for the American southern commander, General Benjamin Lincoln, to arrive with reinforcements. Pulaski frequently suffered from bouts of malaria acquired in the south’s hot swampy coastal lowlands. But the stubborn and proud officer refused to leave active service.

At the beginning of September, General Lincoln prepared to launch an attempt to retake Savannah with long awaited French assistance. Cavalry would play a role and Pulaski was sent to Augusta, Georgia to join General Lachlan McIntosh. Lachlan and Pulaski’s force covered the advance of Lincoln’s offensive. Pulaski captured a British outpost near Ogeechee River. His Legion then acted as an advance guard for the allied French units under Admiral Charles Hector, Comte d'Estaing.

But d’Estaing was on a short timeline. Reliant on his naval support, and with hurricane season fast approaching, he decided to stake everything on a surprise attack on 9 October 1779. Pulaski was given command of the entire combined Franco-American cavalry force. Pulaski, ever impetuous, launched a full scale cavalry charge against heavily defended British fortification. But Pulaski took a ball of grape shot and the assault was soundly defeated.

Pulaski mortally wounded by grape shot

Pulaski mortally wounded by grape shotMortally wounded, Pulaski was moved to a transport ship Wasp in the hope of getting him to Charleston. But the gallant Pulaski died two days later – 11 February 1779. They buried him at sea. And his Legion? His men were transferred under Colonel Charles Armand’s legion for the remainder of the war.

Pulaski monument in his native Poland

Pulaski monument in his native PolandLegacy

Despite his haughty and quarrelsome character, Casimir Pulaski is remembered in many ways. Of course, in Poland, as a man who fought for freedom on two continents and bears the title "Soldier of Liberty." In America, his service and sacrifices are commemorated by the many streets, bridges, counties, and towns that bear his name.

Monument to Pulaski in Washington, DC

Monument to Pulaski in Washington, DCPulaski gave the last full measure outside Savannah, Georgia, and there a large monument commemorates his sacrifice fighting for the city during the American Revolution. In 1833, the new fort being constructed on Cockspur Island outside of Savannah was christened Fort Pulaski in honor of Casimir Pulaski.

Fort Pulaski

Fort PulaskiAbove all, he is the man who provided the American colonists with their first true legion on horseback. The US cavalry later adopted its guidons in red and white, the national colors of Poland, to honor the boldest cavalryman of the War for Independence, and forever cementing his place as "The Father of the American Cavalry."

Published on March 31, 2019 08:05

February 23, 2019

The First Baronet

Who is Peter Parker?

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies will relate the exploits of one Peter Parker. No, not that Peter Parker. Our Peter Parker was not a web crawling teen like his comic book namesake. But before he was a teen, he was skipping along the rigging with a speed and grace that would make even a Spider Man jealous. This is our first naval topic in a while and focuses on a little known British sailor who rose through the ranks through long service, a little patronage, good timing and courage. Sometimes all it takes to rise to the top is just being there.

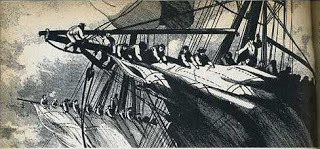

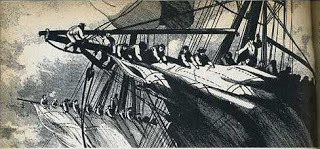

Skipping up the rigging

Skipping up the rigging

Midshipman

Midshipman

Our Peter Parker was born in Ireland in 1721, the son of Vice Admiral Christopher Parker. Like all the legacy officers of the Royal Navy, he started early, serving as a cabin boy and midshipman. In this capacity he served on several vessels under Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon of the West Indies station at the start of the War of Jenkins' Ear.

Vice Adm Sir Edward Vernon

Vice Adm Sir Edward Vernon

War of the Austrian Succession Rear Admiral

Rear Admiral

Sir William Rowley

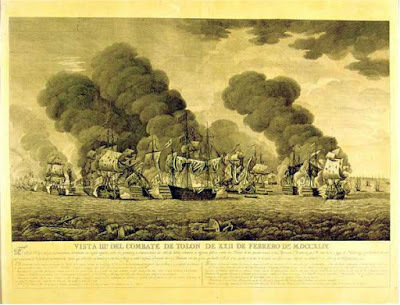

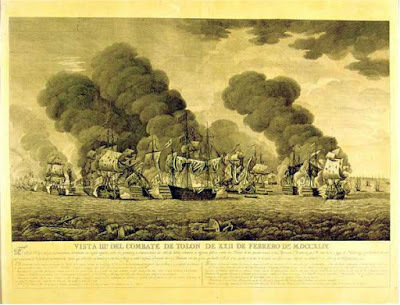

The eight-year War of the Austrian Succession would provide plenty of action for the Royal Navy and lots of opportunities for up and coming young officers like young Peter. Parker received his lieutenant’s commission in the summer of 1743 aboard the HMS Russell, a second rate 80-gun ship of the line. He served on several warships at various stations. Most notably the Mediterranean, where he took part in the battle of Toulon on 11 February 1744 aboard the flagship of Rear-Admiral William Rowley, the 90-gun HMS Barfleur.

In May 1747 he made captain and commissioned a captured French privateer as the 24-gun frigate HMS Margate. Captain Parker commanded this vessel in the Channel, North Sea and the Mediterranean, and when she was paid off in April 1749, he had a short stint aboard the 66-gun HMS Lancaster before going on half-pay with the war’s end. It was common practice to place officers on half pay in between “hot” wars.

Young Lieutenant Parker served at Toulon

Young Lieutenant Parker served at Toulon

Seven Years of War

Captain Parker remained ashore on half-pay for several years while supervising construction of the 44-gun HMS Woolwich at Portsmouth. With the outbreak of the Seven Years’ war, he took to sea on the Woolwich and commanded it on a voyage to the Baltic Sea. But he fell badly ill during the voyage when he caught a fever that swept through the ship.

After he recovered, the navy sent him to the Leeward Islands in December 1756 where in January 1759 he transferred to the 50-gun HMS Bristol. Parker commanded the Bristol in the unsuccessful campaign against Martinique and later in the campaign that took Guadeloupe.

Taking Fort Louis at Guadeloupe was one

Taking Fort Louis at Guadeloupe was one

of many sea-land campaigns in Parker's career

In 1760, he transferred back to home station (the Channel) where he took command of the 64-gun HMS Montague. Parker took several prize-ships while cruising the narrow but deadly waters between Britain and the Continent. His success gained him command of the 70-gun HMS Buckingham and a squadron that reduced French fortifications on the Isle d’Aix. The following year he participated in the assault on a fort at Belle-Isle. This was classic 18th century warfare, reducing posts and gaining chits to negotiate a better peace. But plenty of hot action and naval savvy made this possible. His last wartime command was the 74-gun HMS Terrible just before 1763 Treaty of Paris.

HMS Terrible in action

HMS Terrible in action

Another Half-Pay Hiatus

The 1763 Treaty of Paris consigned Parker and most of his fellow officers on to half-pay. This half pay status was intended to reduce expenses while keeping experienced officers in hand so they could be reactivated for the next war. And in the 18th century Royal Navy, there always was a next war. Parker remained without a command for nearly a decade. But then things got interesting. Knighted in 1772, Sir Peter Parker was given command of the second-rate but heavily armed (90-gun) HMS Barfleur when he rejoined the service in 1773. By 1773 things were heating up in the North America colonies. In 1775 Parker was given command of the fourth rate 50-gun HMS Bristol but more importantly, he would soon receive command of a squadron and promoted to commodore.

Ships returning to Plymouth

Ships returning to Plymouth

War of Rebellion

In February 1776 Captain Peter Parker was named commodore of a small squadron at Plymouth and ordered to transport several Irish regiments under General Charles Cornwallis to America. Destination: the Cape Fear region of North Carolina. This was part of a complex plan in which he would cooperate with North Carolina’s infamous Royal Governor Josiah Martin and General Henry Clinton in an effort to raise Loyalist support in the troubled colony.

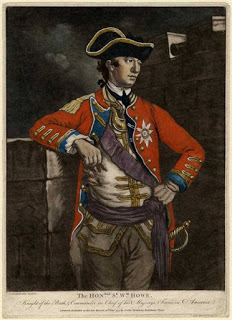

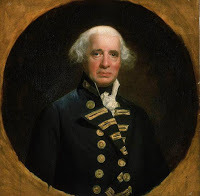

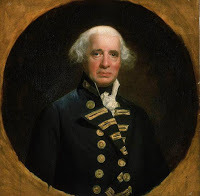

Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet

Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet

Ill-Fated Southern Rendezvous

Bad weather and bad luck would thwart these efforts. A rough Atlantic voyage ensued, and by the time Parker’s armada reached its rendezvous with Clinton, the expected Loyalist uprising they depended on had been crushed. To their chagrin, they learned of the decisive battle at Moores Creek Bridge on 21 February, 1776. The resettled Scots highlanders of the Carolina hill country had agreed to march to the coast in support of the crown. The irony here was that many had been resettled after the disaster at Culloden decades earlier in Scotland. Now they had taken up the claymore on behalf of the crown that vanquished them in 1745. The highlanders’ attack was easily scattered by the rebels from the coastal tidewater - thus, no force to link up with.

Battle at Moores Creek Bridge

Battle at Moores Creek Bridge

But no armada should ever go to waste, so Parker and Clinton shifted their sights south - on Charleston, South Carolina. The town was seen as weakly defended. Quickly seizing it would provide a good naval base in the south and provide a safe haven for Loyalists throughout the region. The idea of winning hearts and minds was still part of the British approach to the war.

Charleston

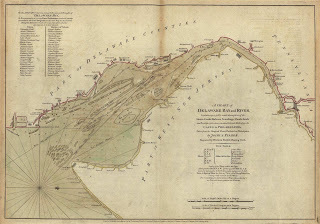

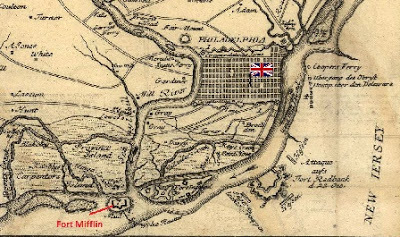

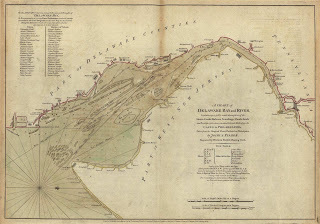

On 1 June, 1776, Parker’s flotilla lay off Charleston but the lack of charts (see the Yankee Doodle Spies Blog Post on hydrography) forced the British to sound the waters while they waited for the tides to favor and attack. A good plan under the conditions, but the delay gave the American commander, Colonel William Moultrie, time to improve the defenses of Fort Sullivan on Sullivan’s Island.

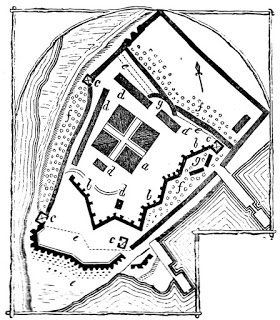

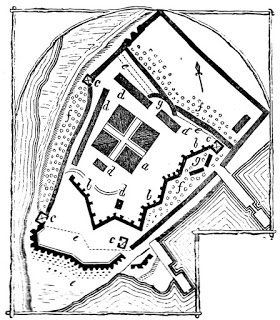

Moultrie's gallant defense of Fort Sullivan

Moultrie's gallant defense of Fort Sullivan

spared the south for a few years

On 28 June, Parker was finally able to land the British troops on Long Island, the island next up the coast to the north-east of Sullivan’s Island, and place ships where they could fire on the island. Despite a horrific bombardment, the defenders held out, protected by Fort Sullivan’s palmetto walls. The spongy bark palmetto logs absorbed cannon fire. The defenders had only a few guns but Moultrie used these to good effect. He concentrated their fire upon Parker’s flag ship, HMS Bristol. In a stroke of ill-luck, the ship’s cable was shot away. Out of control, Bristol swung around, and guns from the fort poured enfilade fire into her.

Our commodore bravely stood his post on the quarterdeck in the finest tradition of the Royal Navy. But a heated cannon ball, deadly red hot shot, seared his pants off his rear end and burned him badly. Meanwhile, things went from bad to worse. To evade capture the frigate HMS Actaeon ran onto shoals and grounded. Under American fire, the savvy British sailors burned their ship to avoid her capture. The intense fighting went on for 10 hours. Finally, with casualties amounting to over 250, Parker signaled the flotilla to break off and they disengaged.

Shoals, palmetto logs and well aimed guns set

Shoals, palmetto logs and well aimed guns set

our commodore's pants afire

Parker’s failure at Charleston saved the south for the glorious cause, at least for a few years. The resultant boost in American morale rallied southern patriots and subdued southern Loyalists. In the kind of war the rebellion was becoming, morale would prove decisive.

True North

With their commodore recovering from his burns, Parker’s flotilla made its way back to New York. There it joined the fleet under Admiral Richard Howe. Commodore Parker recovered enough to command the squadron that captured Long Island in August 1776. There his ships supported the landing of British troops on Long Island, causing the rebel army to be forced from New York City.

Parker's leadership was part of a brilliant sea-land

Parker's leadership was part of a brilliant sea-land

campaign that resulted in victory on

Long Island and New York

In December,1776, Parker was given command of a flotilla that transported an invasion force under Henry Clinton in another successful venture: seizing Newport, Rhode Island. This provided the British an additional base from which to threaten Massachusetts and Connecticut. More sea-land success for the commodore that would not go unnoticed.

Sir Henry Clinton

Sir Henry Clinton

Commodore Parker remained on station at Rhode Island for almost a year with two 50-gun war ships and several frigates under his command. Despite the seemingly apparent back water assignment, his career was about to pivot him in a higher trajectory: flag rank!

A Flag Officer

Comte de Grasse Parker was promoted to rear admiral on 28 April 1777. He was soon named commander of the Jamaica Station (not the subway stop). By that time the British strategy had shifted its efforts in securing as much of the West Indies. The remainder of the war was taken with supporting efforts there against the French and Spanish. He executed his duties proficiently and received promotion to rear admiral in March 1779.

Comte de Grasse Parker was promoted to rear admiral on 28 April 1777. He was soon named commander of the Jamaica Station (not the subway stop). By that time the British strategy had shifted its efforts in securing as much of the West Indies. The remainder of the war was taken with supporting efforts there against the French and Spanish. He executed his duties proficiently and received promotion to rear admiral in March 1779.

His time in America came to a close in 1782. Parker returned to England in August of that year. But he had the distinct privilege of carrying the captured French admiral, Francois-Joseph-Paul, Comte de Grasse, and his staff as prisoners from the Battle of the Saintes. Despite defeat at the Saintes, de Grasse gained honors for his victory at the Battle of the Chesapeake in 1781-a rare defeat of the Royal Navy that set the stage for American victory. One can only wonder about the sea stories they shared over wine during the voyage back! In London, de Grasse would set the stage for negotiations leading to the Treaty of Paris ending the American War for Independence.

High Command

Service in American waters brought Parker great distinction, despite Charleston. He was elevated to a baronetcy in 1783, and given command of Portsmouth harbor, home port of the Royal Navy. During that time he met and mentored a young Lieutenant Horatio Nelson, future victor of Trafalgar. Parker facilitated his early career and for that, if nothing else, the British should hold him in esteem. Parker was named admiral of the fleet in September 1799 upon the death of Admiral Lord Howe. He was also named a general of marines. Sadly, one of Parker’s last official acts was to serve as the chief mourner at Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson’s funeral on 9 January 1806.

Parker would mentor a young Horatio Nelson

Parker would mentor a young Horatio Nelson

and sadly preside at his funeral

An MP

Not uncommon for military officers at the time, Parker served in parliament as MP for Seaford from 1784-6 In 1787, he became M.P. for Malden, which he held until 1790. Parker’s West Indian prize-money allowed him to build an estate in Essex, although during his parliamentary years his address was given as Basingbourn in Cambridgeshire. He supported the government but only made two speeches during his time in the House of Commons. . As a member of Parliament, Parker was a pro-slaver, stating that “the abolition of the Africa Trade would, in my opinion, cause a general despondency amongst the Negroes and gradually decrease their population and consequently the produce of our islands, and must in time destroy near half our commerce and take from Great Britain all the pretensions to the rank she now holds as the First Maritime power in the World.”

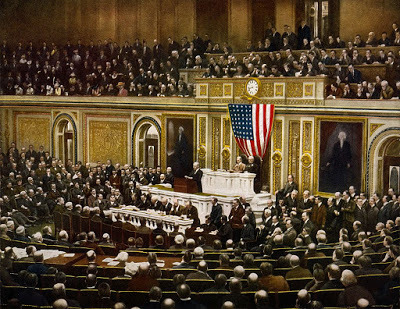

Parliament

Parliament

Family Life

True to his class and position, Parker made a good match in his family life. Parker married Margaret Nugent. They had two sons and two daughters. One son, Christopher, would rise to Vice admiral.

Admiral Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet was viewed as tough and opinionated, and well regarded for his composure and coolness in action. After all, how many admirals continued to fight with their pants seared off? Although he was considered cantankerous, he met his match with Margaret. His wife was of a very strong personality, and during his period of command at Jamaica was almost his equal in the management of the station. He died in London, on 21 December 1811 and was buried at St Margaret's, Westminster.

Peter Parker's resting place at

Peter Parker's resting place at

St. Margaret's Church

Legacy

Peter Parker's Forest Gump like career, spanning decades, continents, battles and interaction with a who's who of the 18th century Royal Navy was not uncommon. After all, forging an empire requires such men to put themselves in strange places, often for years at a time. Naval officers often sprang from a line of naval officers. As we can see, Parker's line was pretty darned accomplished. In addition to being the son and father of an admiral, he was also the grandfather of an admiral. Parker's use of patronage rose his son Christopher (who served under him) to captain and then admiral at a very early age. Christopher's son Captain Peter, the celebrated 2d Baronet, also served under his grandfather as well as Horatio Nelson. The second Peter Parker fought in America as did his father and grandfather. This time in the War of 1812, where during combat near Baltimore in 1814, he was shot in the pants like the first Sir Peter. Unfortunately this would was mortal. He too was buried at St. Margaret's.

Captain Peter Parker, 2nd Baronet

Captain Peter Parker, 2nd Baronet

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies will relate the exploits of one Peter Parker. No, not that Peter Parker. Our Peter Parker was not a web crawling teen like his comic book namesake. But before he was a teen, he was skipping along the rigging with a speed and grace that would make even a Spider Man jealous. This is our first naval topic in a while and focuses on a little known British sailor who rose through the ranks through long service, a little patronage, good timing and courage. Sometimes all it takes to rise to the top is just being there.

Skipping up the rigging

Skipping up the rigging Midshipman

MidshipmanOur Peter Parker was born in Ireland in 1721, the son of Vice Admiral Christopher Parker. Like all the legacy officers of the Royal Navy, he started early, serving as a cabin boy and midshipman. In this capacity he served on several vessels under Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon of the West Indies station at the start of the War of Jenkins' Ear.

Vice Adm Sir Edward Vernon

Vice Adm Sir Edward VernonWar of the Austrian Succession

Rear Admiral

Rear Admiral Sir William Rowley

The eight-year War of the Austrian Succession would provide plenty of action for the Royal Navy and lots of opportunities for up and coming young officers like young Peter. Parker received his lieutenant’s commission in the summer of 1743 aboard the HMS Russell, a second rate 80-gun ship of the line. He served on several warships at various stations. Most notably the Mediterranean, where he took part in the battle of Toulon on 11 February 1744 aboard the flagship of Rear-Admiral William Rowley, the 90-gun HMS Barfleur.

In May 1747 he made captain and commissioned a captured French privateer as the 24-gun frigate HMS Margate. Captain Parker commanded this vessel in the Channel, North Sea and the Mediterranean, and when she was paid off in April 1749, he had a short stint aboard the 66-gun HMS Lancaster before going on half-pay with the war’s end. It was common practice to place officers on half pay in between “hot” wars.

Young Lieutenant Parker served at Toulon

Young Lieutenant Parker served at ToulonSeven Years of War

Captain Parker remained ashore on half-pay for several years while supervising construction of the 44-gun HMS Woolwich at Portsmouth. With the outbreak of the Seven Years’ war, he took to sea on the Woolwich and commanded it on a voyage to the Baltic Sea. But he fell badly ill during the voyage when he caught a fever that swept through the ship.

After he recovered, the navy sent him to the Leeward Islands in December 1756 where in January 1759 he transferred to the 50-gun HMS Bristol. Parker commanded the Bristol in the unsuccessful campaign against Martinique and later in the campaign that took Guadeloupe.

Taking Fort Louis at Guadeloupe was one

Taking Fort Louis at Guadeloupe was oneof many sea-land campaigns in Parker's career

In 1760, he transferred back to home station (the Channel) where he took command of the 64-gun HMS Montague. Parker took several prize-ships while cruising the narrow but deadly waters between Britain and the Continent. His success gained him command of the 70-gun HMS Buckingham and a squadron that reduced French fortifications on the Isle d’Aix. The following year he participated in the assault on a fort at Belle-Isle. This was classic 18th century warfare, reducing posts and gaining chits to negotiate a better peace. But plenty of hot action and naval savvy made this possible. His last wartime command was the 74-gun HMS Terrible just before 1763 Treaty of Paris.

HMS Terrible in action

HMS Terrible in actionAnother Half-Pay Hiatus

The 1763 Treaty of Paris consigned Parker and most of his fellow officers on to half-pay. This half pay status was intended to reduce expenses while keeping experienced officers in hand so they could be reactivated for the next war. And in the 18th century Royal Navy, there always was a next war. Parker remained without a command for nearly a decade. But then things got interesting. Knighted in 1772, Sir Peter Parker was given command of the second-rate but heavily armed (90-gun) HMS Barfleur when he rejoined the service in 1773. By 1773 things were heating up in the North America colonies. In 1775 Parker was given command of the fourth rate 50-gun HMS Bristol but more importantly, he would soon receive command of a squadron and promoted to commodore.

Ships returning to Plymouth

Ships returning to PlymouthWar of Rebellion

In February 1776 Captain Peter Parker was named commodore of a small squadron at Plymouth and ordered to transport several Irish regiments under General Charles Cornwallis to America. Destination: the Cape Fear region of North Carolina. This was part of a complex plan in which he would cooperate with North Carolina’s infamous Royal Governor Josiah Martin and General Henry Clinton in an effort to raise Loyalist support in the troubled colony.

Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet

Sir Peter Parker, 1st BaronetIll-Fated Southern Rendezvous

Bad weather and bad luck would thwart these efforts. A rough Atlantic voyage ensued, and by the time Parker’s armada reached its rendezvous with Clinton, the expected Loyalist uprising they depended on had been crushed. To their chagrin, they learned of the decisive battle at Moores Creek Bridge on 21 February, 1776. The resettled Scots highlanders of the Carolina hill country had agreed to march to the coast in support of the crown. The irony here was that many had been resettled after the disaster at Culloden decades earlier in Scotland. Now they had taken up the claymore on behalf of the crown that vanquished them in 1745. The highlanders’ attack was easily scattered by the rebels from the coastal tidewater - thus, no force to link up with.

Battle at Moores Creek Bridge

Battle at Moores Creek BridgeBut no armada should ever go to waste, so Parker and Clinton shifted their sights south - on Charleston, South Carolina. The town was seen as weakly defended. Quickly seizing it would provide a good naval base in the south and provide a safe haven for Loyalists throughout the region. The idea of winning hearts and minds was still part of the British approach to the war.

Charleston

On 1 June, 1776, Parker’s flotilla lay off Charleston but the lack of charts (see the Yankee Doodle Spies Blog Post on hydrography) forced the British to sound the waters while they waited for the tides to favor and attack. A good plan under the conditions, but the delay gave the American commander, Colonel William Moultrie, time to improve the defenses of Fort Sullivan on Sullivan’s Island.

Moultrie's gallant defense of Fort Sullivan

Moultrie's gallant defense of Fort Sullivanspared the south for a few years

On 28 June, Parker was finally able to land the British troops on Long Island, the island next up the coast to the north-east of Sullivan’s Island, and place ships where they could fire on the island. Despite a horrific bombardment, the defenders held out, protected by Fort Sullivan’s palmetto walls. The spongy bark palmetto logs absorbed cannon fire. The defenders had only a few guns but Moultrie used these to good effect. He concentrated their fire upon Parker’s flag ship, HMS Bristol. In a stroke of ill-luck, the ship’s cable was shot away. Out of control, Bristol swung around, and guns from the fort poured enfilade fire into her.

Our commodore bravely stood his post on the quarterdeck in the finest tradition of the Royal Navy. But a heated cannon ball, deadly red hot shot, seared his pants off his rear end and burned him badly. Meanwhile, things went from bad to worse. To evade capture the frigate HMS Actaeon ran onto shoals and grounded. Under American fire, the savvy British sailors burned their ship to avoid her capture. The intense fighting went on for 10 hours. Finally, with casualties amounting to over 250, Parker signaled the flotilla to break off and they disengaged.

Shoals, palmetto logs and well aimed guns set

Shoals, palmetto logs and well aimed guns setour commodore's pants afire

Parker’s failure at Charleston saved the south for the glorious cause, at least for a few years. The resultant boost in American morale rallied southern patriots and subdued southern Loyalists. In the kind of war the rebellion was becoming, morale would prove decisive.

True North

With their commodore recovering from his burns, Parker’s flotilla made its way back to New York. There it joined the fleet under Admiral Richard Howe. Commodore Parker recovered enough to command the squadron that captured Long Island in August 1776. There his ships supported the landing of British troops on Long Island, causing the rebel army to be forced from New York City.

Parker's leadership was part of a brilliant sea-land

Parker's leadership was part of a brilliant sea-land campaign that resulted in victory on

Long Island and New York

In December,1776, Parker was given command of a flotilla that transported an invasion force under Henry Clinton in another successful venture: seizing Newport, Rhode Island. This provided the British an additional base from which to threaten Massachusetts and Connecticut. More sea-land success for the commodore that would not go unnoticed.

Sir Henry Clinton

Sir Henry ClintonCommodore Parker remained on station at Rhode Island for almost a year with two 50-gun war ships and several frigates under his command. Despite the seemingly apparent back water assignment, his career was about to pivot him in a higher trajectory: flag rank!

A Flag Officer

Comte de Grasse Parker was promoted to rear admiral on 28 April 1777. He was soon named commander of the Jamaica Station (not the subway stop). By that time the British strategy had shifted its efforts in securing as much of the West Indies. The remainder of the war was taken with supporting efforts there against the French and Spanish. He executed his duties proficiently and received promotion to rear admiral in March 1779.

Comte de Grasse Parker was promoted to rear admiral on 28 April 1777. He was soon named commander of the Jamaica Station (not the subway stop). By that time the British strategy had shifted its efforts in securing as much of the West Indies. The remainder of the war was taken with supporting efforts there against the French and Spanish. He executed his duties proficiently and received promotion to rear admiral in March 1779.His time in America came to a close in 1782. Parker returned to England in August of that year. But he had the distinct privilege of carrying the captured French admiral, Francois-Joseph-Paul, Comte de Grasse, and his staff as prisoners from the Battle of the Saintes. Despite defeat at the Saintes, de Grasse gained honors for his victory at the Battle of the Chesapeake in 1781-a rare defeat of the Royal Navy that set the stage for American victory. One can only wonder about the sea stories they shared over wine during the voyage back! In London, de Grasse would set the stage for negotiations leading to the Treaty of Paris ending the American War for Independence.

High Command

Service in American waters brought Parker great distinction, despite Charleston. He was elevated to a baronetcy in 1783, and given command of Portsmouth harbor, home port of the Royal Navy. During that time he met and mentored a young Lieutenant Horatio Nelson, future victor of Trafalgar. Parker facilitated his early career and for that, if nothing else, the British should hold him in esteem. Parker was named admiral of the fleet in September 1799 upon the death of Admiral Lord Howe. He was also named a general of marines. Sadly, one of Parker’s last official acts was to serve as the chief mourner at Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson’s funeral on 9 January 1806.

Parker would mentor a young Horatio Nelson

Parker would mentor a young Horatio Nelsonand sadly preside at his funeral

An MP

Not uncommon for military officers at the time, Parker served in parliament as MP for Seaford from 1784-6 In 1787, he became M.P. for Malden, which he held until 1790. Parker’s West Indian prize-money allowed him to build an estate in Essex, although during his parliamentary years his address was given as Basingbourn in Cambridgeshire. He supported the government but only made two speeches during his time in the House of Commons. . As a member of Parliament, Parker was a pro-slaver, stating that “the abolition of the Africa Trade would, in my opinion, cause a general despondency amongst the Negroes and gradually decrease their population and consequently the produce of our islands, and must in time destroy near half our commerce and take from Great Britain all the pretensions to the rank she now holds as the First Maritime power in the World.”

Parliament

ParliamentFamily Life

True to his class and position, Parker made a good match in his family life. Parker married Margaret Nugent. They had two sons and two daughters. One son, Christopher, would rise to Vice admiral.

Admiral Sir Peter Parker, 1st Baronet was viewed as tough and opinionated, and well regarded for his composure and coolness in action. After all, how many admirals continued to fight with their pants seared off? Although he was considered cantankerous, he met his match with Margaret. His wife was of a very strong personality, and during his period of command at Jamaica was almost his equal in the management of the station. He died in London, on 21 December 1811 and was buried at St Margaret's, Westminster.

Peter Parker's resting place at

Peter Parker's resting place atSt. Margaret's Church

Legacy

Peter Parker's Forest Gump like career, spanning decades, continents, battles and interaction with a who's who of the 18th century Royal Navy was not uncommon. After all, forging an empire requires such men to put themselves in strange places, often for years at a time. Naval officers often sprang from a line of naval officers. As we can see, Parker's line was pretty darned accomplished. In addition to being the son and father of an admiral, he was also the grandfather of an admiral. Parker's use of patronage rose his son Christopher (who served under him) to captain and then admiral at a very early age. Christopher's son Captain Peter, the celebrated 2d Baronet, also served under his grandfather as well as Horatio Nelson. The second Peter Parker fought in America as did his father and grandfather. This time in the War of 1812, where during combat near Baltimore in 1814, he was shot in the pants like the first Sir Peter. Unfortunately this would was mortal. He too was buried at St. Margaret's.

Captain Peter Parker, 2nd Baronet

Captain Peter Parker, 2nd Baronet

Published on February 23, 2019 10:46

January 27, 2019

The Militia General

The Militia General: Philemon Dickinson

The role of the militia during the struggle for independence can best be described as uneven. For a variety of reason militias were unreliable and often ill equipped. But mostly they were poorly led. But in Philemon Dickinson they had a leader any Continental soldier would be proud to follow. Like the militia, Dickinson is a mix of understated service and quiet achievement. Unlike many militia units, Dickinson was always reliable. Like the militias he led, Dickinson always had one eye on the home front.

Philemon Dickinson

Philemon DickinsonThe Making of a Citizen

Philemon Dickinson was born at "Crosiadore”, in Talbot County, Maryland on 5 April 1739. The son of a local judge, Philemon was also the younger brother of fellow first-patriot and signer John Dickinson. Following his graduation from the College of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1759 the younger Dickinson clerked briefly at his brother John’s law office. But Dickinson abandoned the profession shortly after and began to manage their father’s estates. In 1767 he married, Mary Cadwalader, member of one of the area's most prominent families. The couple moved to a farm just outside Trenton, New Jersey.

Dickinson attended the College of Pennsylvania

Dickinson attended the College of PennsylvaniaA Call to Arms

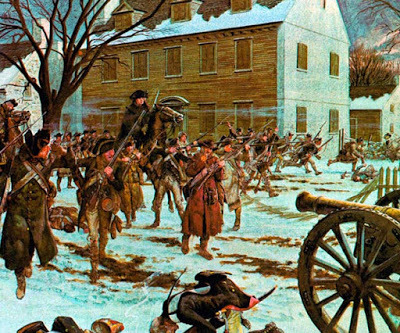

With a family caught up in revolutionary politics, it was natural that Philemon would eventually play a role along with big brother John. In 1775 he was offered a colonelcy in the Hunterdon County militia. This first patriot quickly accepted. By October the following year he had risen to the rank of brigadier general – he also held a seat in the state’s provincial congress. During the Continental Army’s retreat across the Jerseys in 1776, Dickinson proved a valuable asset to the beleaguered George Washington. Dickinson’s performance under fire at Trenton in December 1776 was most noteworthy. There the sturdy militia general ordered his own home shelled in the heat of battle after he learned it was an enemy command post!

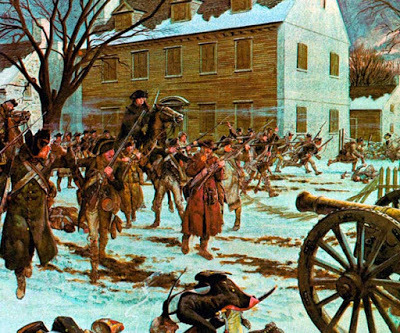

The American attack on Trenton

The American attack on TrentonKicking Off the Forage War