S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 7

February 28, 2021

Shores of Tripoli

This is a rare and unusual Yankee Doodle Spies sequel segment. Although it is a stretch, I felt the need to review this board game because it portrays events that have some surprising connections to the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies. What spurs me to review this game? In a word, fun. Shores of Tripoli provides an entertaining and fascinating look at this seminal period in United States national security policy. Players learn while playing, and interact while learning. And they have fun. But I think I mentioned that.

Poster of the 1950s Action Flick

Poster of the 1950s Action Flick

The designer and owner of Fort Circle Games, Kevin Bertram, writes of his inspiration for the game – Brian Kilmeade’s book on the subject, which is the American effort to suppress the Barbary (North African) States and their corsairs (pirates) at the dawn of the 19th century. I confess - I have not read the book, although I have read others on the topic and had seen the John Payne film, Tripoli as a youngster. In his designer notes, Kevin mentions he developed the game when he learned no one had done anything on the subject. I myself started playing board wargames when I was in 3rd grade. The first I recall was named Tactics II. I continued wargaming for decades and even dabbled in miniatures. As I read Kevin’s words, I realized he was right. So the game is groundbreaking for that little-known conflict.

Box CoverThe Mechanics

Box CoverThe MechanicsI am not referring to Paul Revere’s spy network, but how the game is played. I will leave it for others to do a play-by-play on the rules. And you can find many YouTube clips on the rules by Kevin and many players who enjoy the game.

The game is first a board game, with a map of north Africa that is simple and quite easy on the eyes. Key ports, such as Gibraltar (British held and neutral), Malta, Tripoli, Alexandria, and Derne are displayed. They are where most of the action takes place. You move ship markers, such as American, Swedish and Tripolitan frigates; American cutters, and Tripolitan and allied corsairs. You also have soldier markers: US marines, Hamet’s (deposed older brother and rival to Tripolitan ruler Yusuf Karamanli) mercenaries, and Barbary pirates.

Pieces, Dice & Board

Pieces, Dice & BoardCombat is via die rolling. This game has lots of die rolling. Luck trumps everything. I think Napoleon once remarked he would rather have a lucky general than a good one. But the game is really driven by card play. Players draw cards from a deck each turn. You can discard any card to make a move or play select cards to bring on reinforcements or implement several other procedural things. But the secret sauce is the Event Cards. They drive the game - setting up movement, combat, political action, and more. Players are constantly picking up, discarding, or playing cards as the game moves across four seasons a year over the years 1801 – 1806. They provide surprises, both good and bad. How a player uses the cards he or she is dealt can make up for bad dice and bad decisions. So keep an eye on them. And may the odds ever be in your favor.

American Frigate takes on a Barbary Corsair

American Frigate takes on a Barbary Corsair

The game gives players (it is a two-player game with a solitaire option that is cool) about an hour of fun and frustration. The American has lots of advantages such as big ships (frigates), US Marines, and Swedish allies. Yeah -Sweden! But the American has a lot to lose and closing the deal, which is assaulting and taking Tripoli, can produce a Ragnarök-like end to the game. The American player starts slowly as he builds up firepower by bringing on frigates and gunboats while those pesky pirates go on raids.

The Cards make the Game

The Cards make the GameThe Barbary player has less firepower but more flexibility. He can run out the clock. If the American player is too cautious, the barbary player may have time to launch enough raids to win by capturing treasure (gold-colored coins). Or he can win if the American fails to combine the right mix of naval and land power to take Tripoli. And though the American frigates are powerful, they are also an Achilles heel: losing four of them wins the game for the Tripolitan cause. This simulates the impact of American and European public opinion for suffering unacceptable losses. A draw is a win for the Barbary States but the Americans can use cards and shrewd maneuvers to force a treaty and win.

USS Philadelphia under attack

USS Philadelphia under attack

Either way, both sides have fun and learn a lot about this important but little-known event in American history.

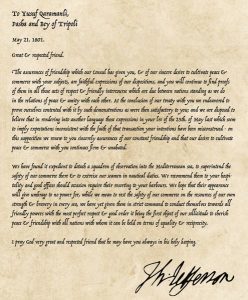

Jefferson's Letter to the Bey

Jefferson's Letter to the BeyThe game comes with a very smart-looking historical supplement and designer notes that complement the rules quite nicely. The design, artwork, and layout are top quality. A fun feature is the “mock-up” of the 21 May 1801 letter to the Pasha and Bey of Tripoli, Yusuf Karamanli, explaining the reason for the friendly visit of the American squadron to the Mediterranean waters. Nice scene-setter providing atmospherics as you read President Jefferson’s assuring words.

Yankee Doodle Spies Sequel?The war against the Barbary States was the first American attempt at overseas force projection. One of the consequences of the American War for Independence and American sovereignty was losing the protection of the mighty British Navy. This was clear during the undeclared naval war with France, an event that brought the rebirth of an American naval force centered around a small force of "super-frigates," which functioned as small and swift ships-of-the-line.

Key figures – Rev War ConnectionsI will now circle back to the American Revolution with some interesting connections between the Tripoli affair and the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies.

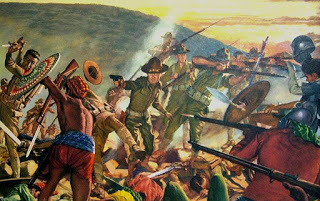

1st Lt Presley O'Bannon raises American flag over Derna

1st Lt Presley O'Bannon raises American flag over Derna

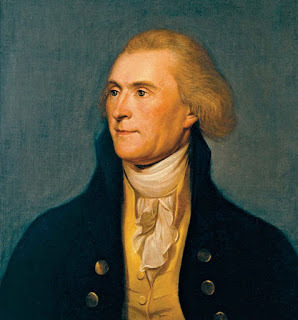

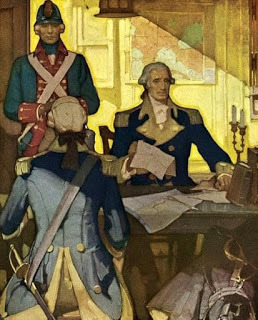

The most obvious is President Thomas Jefferson, the central figure in the event. The founding father and first Secretary of State tried to navigate a peaceful approach to the Barbary States’ demands for tribute - short of actually paying it. This was driven by the national pride of a newly independent and still insecure republic and the paucity of funds. His 21 May 1801 letter was his last-ditch attempt to negotiate. But the Bey of Tripoli had decided on war, declaring it on 14 May.

President Thomas Jefferson

President Thomas Jefferson

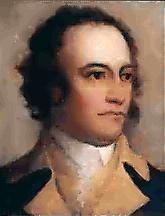

William Eaton is one of those badass historical figures who played a large role in a key event. Son of a middle-class New England farmer, young Eaton served in the Continental Army from 1780-1783, ending with the rank of sergeant at the age of 19. He got some schooling after the war and later became a captain in the new American Legion under famed Revolutionary War hero, Major General “Mad” Anthony Wayne in the war against the western Indian nations. There he faced some controversy and a court-martial for war profiteering and busting a prisoner from the goal. He received a 2-month “suspended commission.” In the whacky world of Federalist-era bureaucracy, he stayed on in the army and was appointed US Consul to Tunis in 1797. That made Eaton the point man for the US in the region. In 1804 he convinced the administration to conduct a special operation to bring Yusuf’s brother Hamet into the war. It was approved and Eaton led a small expeditionary force to Alexandria where they hooked up with Hamet and his motley mercenary army. With the marines and a few sailors as the core of the fore, they marched west to Derna and in a desperate struggle, took the city. But Hamet’s unreliability coupled with peace overtures scotched any further effort. Eaton would return to America heralded, but bitter.

William Eaton

William Eaton

Arguably the biggest badass of the war (and the US Navy had substantial numbers of these) was a United States Marine officer, Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon. A native of Virginia and son of a Revolutionary War officer. O’Bannon entered the Marines in 1801 as a 2nd Lieutenant and was promoted to 1st Lieutenant the following year. He held a variety of commands aboard ship and off, and during the Derna operation, commanded a squad of 8 marines and a naval ensign. O’Bannon’s bravery and daring were demonstrated on 27 April 1804, at Derna. O'Bannon led the marines, some Greek mercenaries, and a few artillery gunners in a hell-raising charge through a deluge enemy musketry. Ignoring the buzz of lead about him, he seized an enemy battery and hoisted the American flag on the city’s walls. He then turned the captured cannons on the enemy. After two hours of hand-to-hand fighting, the fortress was taken. This was the first time the stars and stripes flew over a fortress of the old world in a time of war. O’Bannon received a jeweled Mameluke scimitar as his reward for his valor, and when he returned to Virginia, his home state presented him a commemorative one as well. To this day, marine officers wear a similar sword. After the war, he resigned his commission and moved his family west, settling in the bluegrass of Kentucky. Interesting Revolutionary connection: badass O’Bannon had married the granddaughter of the ultimate Revolutionary War badass – famed rifleman and General Daniel Morgan, of Winchester, Virginia.

1st Lieutenant Presley O'BannonTobias Lear

1st Lieutenant Presley O'BannonTobias LearAnother interesting Revolutionary War connection was Tobias Lear. The New Hampshire native was conspicuous in not serving in the Revolutionary War but attended Harvard from 1779-83. Lear was an ambitious but capable player who worked his way up from tutor of Martha Washington’s grandchildren to become George Washington’s secretary and right-hand man. He was visiting his old boss at Mount Vernon when Washington died. Lear eventually worked his way into the graces of President Thomas Jefferson and in 1801 Jefferson appointed Lear Consul-General to the North African coast. In that capacity, Lear on June 4, 1805, negotiated a "Treaty of Peace and Amity" with Yusuf. It was a bitter pill for many Americans. Lear negotiated a ransom of $60,000 (equal to $1,024,400 today) that paid for the release of sailors from the USS Philadelphia and some American merchant ships. Ironically, the Philadelphia was to be the ship transporting him to the region but a delay to get married (to a Washington/Custis girl) had him sail on the Enterprise.

Tobias Lear

Tobias Lear

January 31, 2021

The Fighting Judge

If you ride up I 79 from Pittsburgh to Erie, Pennsylvania the third to last exit is for a town named McKean, a small borough of some 300 residents. After many rides through the place, I decided to find out who this unassuming town was named for. Well, some quick research took me into the world of a first patriot, and founder, who helped frame two states, a nation, and even a system of law. And he was not averse to some combat along the way.

Son of a TavernkeeperThomas McKean was born, some twenty miles west of Wilmington, Delaware in New London, Pennsylvania on 19 March 1734. The connection is important in that in many ways, McKean’s future was woven into both Pennsylvania and the future state of Delaware, then known as the lower counties of the keystone state. His parents were William McKean, a tavern-keeper, and Letitia Finney. They had immigrated to Pennsylvania from Ballymoney, County Antrim, Ireland, when they were youngsters, so McKean was another first patriot son of Ireland.

McKean's youth probably saw him working in one of his father's taverns

McKean's youth probably saw him working in one of his father's tavernsReading the Law

The younger McKean would not become a tavernkeeper. Instead, he received an excellent education, beginning at the New London Academy and later at New Castle, Delaware he read the law under David Finney, a cousin. His “dual-jurisdiction” career began when he was admitted to the bar in 1755 in both The Lower Counties (Delaware) and Pennsylvania. A year later he was appointed deputy attorney general for Sussex County. Political life quickly mixed with law, and McKean served several terms in the General Assembly of the Lower Counties in the 1760s and 1770s, including a stint as Speaker. His intellectual bona fides were certified when, in 1768, the talented jurist was elected to the American Philosophical Society. Not to be idle during this same period, he also served as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas and in 1771 was appointed Customs Collector in New Castle. An impressive resume and the road to rebellion had not reached its apex. But things were heating up.

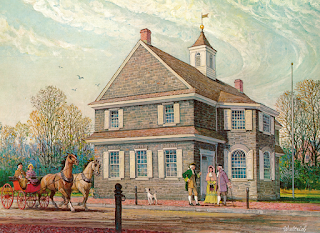

Colonial Court House

Colonial Court HouseThe Lower Counties Splinter

Politically, the Lower Counties were divided into an Anglican pro- British faction, the Court Party, and a Scots-Irish patriot faction, the Country Party. The majority of counties were Court Party. New Castle was Scots-Irish and patriot and McKean soon emerged its leader. He first gained political renown outside of Delaware when he represented the Lower Counties at the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 and helped draft the petition to Parliament and called out the opposition, Timothy Ruggles on the open floor, almost engaging in a duel.

The Stamp Act Congres met at Federal Hall in NYC

The Stamp Act Congres met at Federal Hall in NYC

When the First Continental Congress was called in 1774, McKean, along with Caesar Rodney and George Read, represented Delaware. He would return in the same capacity for the Second Continental Congress in 1775 and 1776. It was in the latter where he advocated passionately for independence. When he and Read split the Delaware vote, Caesar Rodney was not present., McKean called for Rodney’s return and the famous midnight ride of Caesar Rodney resulted in Delaware going 2-1 for independence. The Declaration was approved.

Caesar Rodney's all-night ride would usher independence

Caesar Rodney's all-night ride would usher independenceFollowing the Drum

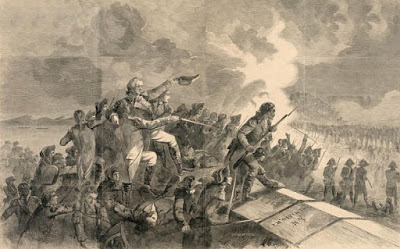

The ink was not dry on the Declaration when McKean suddenly left Philadelphia to assume command as colonel of the Fourth Battalion of the Pennsylvania Associators, a militia unit. The battalion took part in the desperate campaign to defend New York City in the summer and autumn of 1776. It was then given the role of defending Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Because of his active military service, McKean missed signing the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776, and his signature was not on the printed copy that was authenticated on January 17, 1777. But he did sign the “death warrant” sometime later and some believe he was the “last signer.”.

McKean commanded one of the famed Associator Battalions

McKean commanded one of the famed Associator BattalionsWartime Politico

Curiously, the Delaware Assembly elected neither Rodney nor McKean to Congress in October 1776. The firebrands had made some enemies and many were still wobbly on full independence. But the British victory at Brandywine in September 1777 hit too close to home for comfort, and the two ardent patriots were returned in October. Despite being pursued relentlessly by the British and Loyalists, McKean served in Congress for the rest of the war. He helped draft the Articles of Confederation and was elected President of the Confederation Congress and served from July through November 1781.

McKean was active in national as well asPA & DE politics

McKean was active in national as well asPA & DE politicsFirst Son of Delaware

McKean was active in Lower County politics throughout the run-up to war and beyond. He was often active at the national and local levels. He spearheaded the movement to make the Lower Counties a separate state and in August 1776, the assembly chose him to attend a convention aimed at writing a new state constitution. McKean left his command and rode to Dover, Delaware like a hellion, and in one night, produced the first draft of a Delaware Constitution which the assembly adopted in September. This was the first state constitution to be drafted after the Declaration of Independence. He stayed active in the Delaware Assembly throughout the mid and late 1770s even as he served in the Congress. The British occupied Philadelphia and controlled the Delaware River from October 1777 through June of 1778. During this period both he and his family were at risk of capture by the British, and he was forced to change his residence some five times.

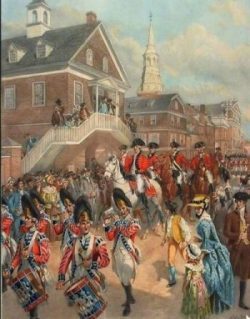

British occupied Philadelphia

British occupied PhiladelphiaKeystone Judge

While still active in Delaware politics, McKean had the unusual situation of being appointed a judge in Pennsylvania, serving as Chief Justice from1777 until 1799. McKean was a leading proponent of a judiciary, with the power to overturn a state law, if needed, as unconstitutional He was a very aggressive jurist and established judicial review, the power of a court to strike down laws before John Marshal established it for the US Supreme Court. His influential 22 years on the bench established precedents adopted by all the state courts in the nation.

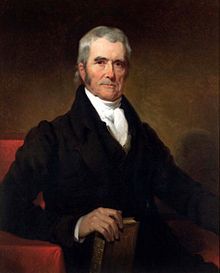

McKean set precedents in jurisprudence before John Marshal

McKean set precedents in jurisprudence before John Marshal

During this time, he served in the convention of Pennsylvania, helping ratify the new Constitution of the United States. Interesting, since he helped draft the Articles of Confederation, which were overturned. In the Pennsylvania State Constitutional Convention of 1789-90, he argued for a strong executive and sided with the Federalists until 1796, when he became an outspoken Democratic-Republican. He was dissatisfied with Federalist policies. As supreme justice of Pennsylvania, he sided with suppressing the Whiskey Rebellion.

The Whiskey Rebellion pose legal as well as security issues

The Whiskey Rebellion pose legal as well as security issuesChief Executive

McKean’s life on the bench ended when he was elected Governor of Pennsylvania in 1799. In his first term, he entered office as a partisan zealot, ousting Federalists from positions – the spoils system. By his third term, he was at odds with his party and allied with the Federalists to fend off a challenge from a fellow Republican. He then ousted the republican officeholders and replaced them with Federalists. McKean’s combative nature, championing a strong state executive, and willingness to turn on his opposition led the Pennsylvania House of Representatives to impeach him in 1807, but he remained in office until his term expired.

Lancaster was the Pennsylvania capital during McKean's tenure as governor

Lancaster was the Pennsylvania capital during McKean's tenure as governorThe Man

McKean was over six feet tall. He dressed fashionably in a cocked hat and gold-knobbed cane. . He had a quick temper, a thin face, with a hawk-like nose and flaming eyes. He could be aloof and antagonistic and was by all accounts, a solitary man. Only socializing on public occasions. But he was indisputably brilliant and tireless.

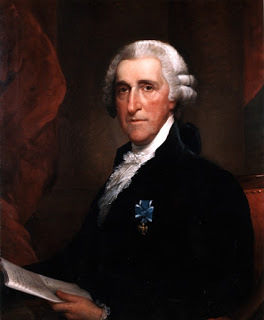

Mckean as Governor of Pennsylvania

Mckean as Governor of Pennsylvania

In his correspondence the not-so-liked himself John Adams paid him tribute, describing McKean as “one of the three men in the Continental Congress who appeared to me to see more clearly to the end of the business than any others in the body.”

The Family ManThe brilliant, active, but often acerbic McKean did find time to have a family life. He married Mary Borden in 1763 and had six children with her: Joseph, Robert, Elizabeth, Letitia, Mary, and Anne. Mary died in 1773 and a year later McKean married Sarah Armitage. He set up his new household in Philadelphia and they had four children, Sarah, Thomas, Sophia, and Maria. McKean and both his wives were members of the Presbyterian Church.

Sarah Armitage McKean

Sarah Armitage McKeanRetirement and Legacy

He spent his retirement in Philadelphia, writing, discussing political affairs, and enjoying the considerable wealth he had earned through investments and real estate. In 1790 he co-published "Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States." McKean was a plank holder in the politically controversial (too aristocratic) Society of the Cincinnati in 1785 and even its vice-president. He had many accolades. He received an LLD from Princeton in 1781, from Dartmouth in 1782, and the University of Pennsylvania in 1785. When a second war with Britain threatened in 1812 the eighty-something, McKean led a Philadelphia citizens group to organize a strong defense during the War of 1812.

Mckean with son Thomas

Mckean with son Thomas

McKean died in Philadelphia and was buried in the First Presbyterian Church Cemetery there. In 1843, his body was moved to Laurel Hill Cemetery. McKean was a man of the law who worked tirelessly, often multi-tasking, for his community, his state(s), and his nation – in war and peace. This son of Irish immigrants set precedence for the future laws and governance of the United States and governance of all the states that would join the union.

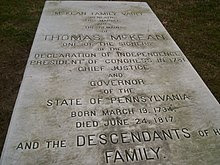

The McKean Grave at Laurel Hill

The McKean Grave at Laurel Hill

December 28, 2020

Committee of Secrets

War in the Shadows

Students of insurgencies have long understood the need to deprive the insurgents of external support. In the course of history, few insurgencies or rebellions have succeeded without outside help, which could take the form of moral support, funding, training, weapons, equipment, supplies, political support, and military forces.

Moro insurgents vs US Army in Philipines

Moro insurgents vs US Army in PhilipinesEarly on in the insurgency that would explode into rebellion after Lexington and Concord, the Americans established a means to maintain dialogue and coordination among the colonies and later states. It soon became clear America would need to reach across the Atlantic as well. Winning over Americans were just one piece of the complex struggle now underway. Tapping support in Britain, building alliances with sympathetic countrymen, would also be an important component in gaining recognition for the new nation. And the European powers would also provide a fertile ground for support, if properly “tilled.”

Burning of Revenue Cutter, Gaspee at Warwick, RI early act of Insurgency

Burning of Revenue Cutter, Gaspee at Warwick, RI early act of InsurgencyA Secret Committee

By the time the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in 1775, this need for international support resulted in the formation of the Committee of Secret Correspondence via two resolutions of 29 November:

RESOLVED, That a committee...would be appointed for the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain, and other parts of the world, and that they lay their correspondence before Congress when directed.

RESOLVED, That this Congress will make provision to defray all such expenses as they may arise by carrying on such correspondence, and for the payment of such agents as the said Committee may send on this service.

Due to the secret nature of the work involved, the members soon added the word “Secret” to its name. The committee received considerable authority from Congress to perform multiple functions: public and secret diplomacy, intelligence gathering, and public relations/influencing opinion. In many ways, it operated as a State Department and CIA. It was the Continental Congress’s eyes and ears in Europe and would soon become its arm in Europe.

Extract of Committee's Secret Instructions

Extract of Committee's Secret Instructions

First Members

Congress did a good job selecting the initial members of the committee, coming up with such luminaries as Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Johnson, John Dickinson, John Jay, and Robert Morris. Others were added later, including James Lovell, former schoolmaster, Bunker Hill veteran (arrested by the British for spying), and member of Congress, who developed the committee’s first codes and ciphers. One must surmise Dr. Benjamin Franklin, who for many years represented the American colonies with the British government, provided a trove of ideas and actions based on his experience abroad. John Jay and likely the others had experience organizing secret meetings and activities along the road to rebellion while surrounded by rings of Tories anxious to root them out.

The Committee at Work

Tactics and Tradecraft

It is a tribute to the American leaders of the age that they were so quick to learn and adopt the most sophisticated techniques and practices so long employed by the great powers of Europe. They used clandestine agents overseas, employed covert actions, created codes and ciphers, employed propaganda, and conducted covert postal surveillance of official and private mail. They employed open-source intelligence by purchasing foreign publications, which they analyzed. Most significantly, they put in place an elaborate communication system, using a variety of couriers. Another critical innovation was establishing a maritime capability separate from the Continental Navy, for purposes of smuggling, moving agents, and correspondence and interdicting British ships.

Secure communications were essential

Secure communications were essential

First Actions

The committee moved quickly. They initiated regular correspondence with English Whigs and Scots who supported the ideas if not all the actions, of the Americans. The experienced and worldly Benjamin Franklin was the most active, initiating correspondence with a wide array of contacts he had developed in Britain and Europe in a sophisticated campaign to build sympathy for the patriot cause.

Dr. Franklin's experience in London proved invaluable to the new committee

Dr. Franklin's experience in London proved invaluable to the new committeeFranklin initiated secret correspondence with Spain, via Don Gabriel de Bourbon, a member of the Spanish royal family and an associate of Franklin. Franklin gave not so subtle reference to advantages to Spain, an American alliance might yield.

Don Gabriel de Bourbon one of Franklin's A-List contacts

Don Gabriel de Bourbon one of Franklin's A-List contactsAgents at Home

But curiously, it was France who reached out first dispatching Julien Alexandre Achard de Bonvouloir to Philadelphia to examine the feasibility of covert aid and political support.

Achard de Bonvouloir

Achard de BonvouloirIn December 1775, the committee members Benjamin Franklin and John Jay staged a secret meeting with the French intelligence agent, de Bonvouloir, who was using the cover of a Flemish merchant.

Franklin and Jay wanted to know if France would aid America, and at what price. They stressed an urgent need for arms and munitions, which would be exchanged for American tobacco, rice, and other crops. De Bonvouloir advised the French government eschewed any role in transactions with the rebels. Instead, private merchants would be used.

Father of American Counterintelligence - John Jay

Franklin assured de Bonvouloir America would not reconcile with Britain and that once it declared independence, France should form an alliance. This was the beginning of a long term campaign to bring not only French aid but also French arms into the struggle.

Silas Deane

Silas DeaneAgents Abroad

Franklin and Jay were heartened by French interest in the American cause. In early March 1776, the Secret Committee appointed Connecticut lawyer Silas Deane as a special envoy to negotiate in Paris with the French government. His mission was to establish covert aid and gain political support through Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, Louis XVI’s Foreign Minister. Vergennes was a master of public and secret diplomacy for the French king and ran both with a steady hand.

Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes

Charles Gravier, Comte de VergennesThe committee eventually included an American living in London. Arthur Lee, a member of the famed Lee family of Virginia. Lee had contact with the French playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a polymath, playwright, clockmaker, and diplomat who was also a secret French agent. Using a letter sent by the committee, Lee provided Beaumarchais with information about American successes – much of which was propaganda to influence French thinking. As an interesting aside, people today might recognize Beaumarchais, not for his devotion to freedom (and money-making) but for his composing the Figaro plays Le Barbier de Séville, Le Mariage de Figaro, and La Mère coupable. These later became adapted as operas that are still enjoyed today.

Arthur Lee

Arthur LeeBut Beaumarchais was a champion of the American cause and needed no puffed-up reports to stir his passion for freedom. Working with Deane back in Paris, he helped influence French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, and King Louis XVI to provide the colonies with clandestine shipments of gunpowder and war material. Support critical in the early years of what was now, a war. The vehicle was the front company Rodrigue y Hortalez (R&H), chartered as a Spanish trading company. R&H was the vehicle for shipping surplus French arms and munitions to the West Indies (primarily the Dutch colony Saint Eustatius), where American agricultural products were exchanged for the war goods.

Beaumarchais: Polymath and Freedom-Lover

Beaumarchais: Polymath and Freedom-LoverDeane was responsible for the earliest aid to America’s struggling army resulted from his efforts. Besides arranging for clandestine shipments (R&H was just one covert operation), he recruited French officers, made introductions, sought out ships for privateering, and touted the American cause with the French cognoscenti. Some of the officers recruited by Deane included the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron Johann de Kalb, Thomas Conway, Casimir Pulaski, and Baron von Steuben. A who's who of ex-pat freedom fighters.

Marquis de Lafayette

Marquis de LafayetteThe American commissioners in Paris rode a whirlwind of intrigue as they wooed and seduced the French and fended off Sir William Eden’s British secret service. Eden had dispatched an American named Paul Wentworth to Paris when Silas Deane arrived. Deane was acquainted with Wentworth and soon he was reporting on Deane’s activities and later, Franklin’s. Wentworth also recruited the American Commission's secretary, Edward Bancroft.

William Eden,1st Baron Auckland & British Spymaster

William Eden,1st Baron Auckland & British SpymasterBut Lee was now in Paris. So was Benjamin Franklin himself, who sailed for France in December 1776. Throughout 1777 the full-court (sic) press was on. The British and French were opening the American commission's mail in a variety of clandestine operations. Servants and friends were recruited to spy, influence, and report. Bancroft provided inside reporting to Wentworth and Eden. And so it went. Meanwhile, Franklin charmed all men and women in sight, was the toast of Paris and continued to influence. He knew his every word and gesture were reaching Versailles and London and every step he took had that in mind.

Franklin's every move and comment were tracked, and he acted accordingly

Franklin's every move and comment were tracked, and he acted accordinglyWhat's in Name?

The Committee of Secret Correspondence became the Committee of Foreign Affairs in April 1777 but retained its intelligence functions. As the first American government agency for both foreign intelligence and diplomatic representation, it was essentially the forerunner of both the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency, as well as today's Congressional intelligence oversight committees. Despite the name change, the Foreign Affairs Committee still served an essential and critical function for Congress, as the eyes and ears of the country in Europe.

Note: Perhaps to confuse the British, Congress created a separate "Secret Committee" in 1775 to obtain supplies, which by its nature needed cloaking from British eyes and British ships. Many of its members also served on the Committee of Secret Correspondence. It became the Committee of Commerce around the same time as its 'sister" committee became the Committee of Foreign Affairs.

The Committee of Foreign Affairs combined the roles of State and CIA, plus "Oversight"

The Committee of Foreign Affairs combined the roles of State and CIA, plus "Oversight"Payoff

The Committee of Secret Correspondence/Secret/Foreign Affairs Committee’s efforts paid off in a big way when an American army, using arms and munitions covertly provided by France forced the surrender of a British army at Saratoga in October 1777. No one in France could recall the last time a British army surrendered to the French. The long and winding road to a treaty with France was now a superhighway. But the committee was not done. The details of an alliance, future loans to America, the basis for negotiations and peace, were all work to be accomplished by the committee. The capitals of Europe were also a target as the commission sought to bring Netherlands, Prussia, Spain, and Russia to the side of the cause. But these are tales for another time.

November 29, 2020

The Queen’s Ranger

This profile is truly one of THE badasses of the American Revolution, a struggle that had more than its share of badasses. But John Graves Simcoe was not the usual badass, fueled by testosterone and a lust for blood – although the (very excellent) TV series TURN might have you think he was that and more – psychopath comes to mind.

Simcoe as played by actor Samuel Roukin

Simcoe as played by actor Samuel RoukinBut the real John Graves Simcoe was anything but. He was, in fact, a well educated professional officer, liked by his troops and superiors, and respected, and sometimes feared, by his adversaries. Born in Cotterstock, England on 25 February 1752, he was the son of a Royal naval officer who received a classical education at Eton and Oxford. But in 1771, Simcoe left school at 19 and purchased an ensign’s commission with the 35th Regiment. His education would place him above most of his peers as he had a thorough knowledge of classical Greek and Roman military tracts. He would soon get to put theory into practice in the dark woods and green fields of America.

Simcoe took a commission at 19

Simcoe took a commission at 19Off to America

Simcoe was delayed in sailing to America and arrived after his 35th Regiment was devastated in the bloodbath that was Breed’s Hill. So during the American siege that followed, he purchased a captaincy in the grenadier company of the 40th Regiment where he fought in several of the engagements in New York and New Jersey. Ambitious, he had sought command of the Queen's Rangers as early as the summer of 1776, when the army was on Staten Island. But it was not offered to him.

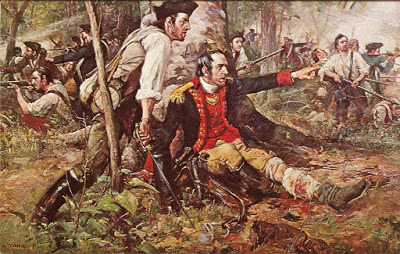

Brandywine

BrandywineSimcoe fought gallantly at the Battle of Brandywine in September of 1777, suffering major wounds during the British triumph. While recuperating, things went into play that would shift the trajectory of his career, snatching him from the humdrum career of a line officer. Simcoe was an outspoken critic of military tactics and had opined to his leadership that the British needed a light infantry force to counter the skirmishing tactics of the Americans.

New Kind of Unit

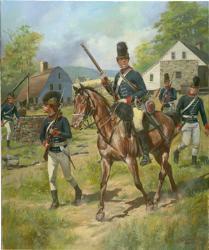

He must have impressed his commander In chief, Lieutenant General William Howe, who promoted him to major in October and gave him command of the Queen’s Rangers. The Rangers were once a storied unit formed by the even more storied hero of the French and Indian War, Major Robert Rogers. The unit’s star had faded along with that of Rogers, who had left the army. Simcoe went right to work drilling it in the unorthodox tactics he knew the American war demanded. Outfitted in green uniforms and tirelessly drilled to fight as skirmishers in deep woods, patrol dense forests, and conduct raids and ambushes, they would eventually strike fear in all they faced. He eventually raised the unit to around 11 companies of some 30 men each. One was a “hussar” (light cavalry) company. He also added a light infantry and a grenadier company.

Queens Rangers were trained for strength and skirmishingNew Kind of Action

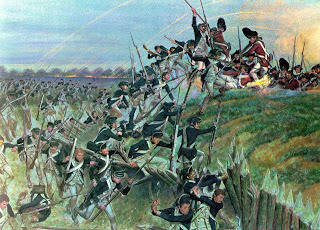

Queens Rangers were trained for strength and skirmishingNew Kind of ActionWith the coming of the spring campaign in March 1778, Simcoe’s new unit had its first action. The Queen’s Rangers squared off against two American militia detachments in actions at Quinton’s and Hancock’s bridges, in New Jersey. The Americans were thrashed by the aggressive actions of Simcoe and his men. A few months later the rangers gave a sound drubbing to General John Lacey’s boys at Crooked Billet, Pennsylvania on 1 May. Less successful was the attempt to trap a reconnaissance detachment led by the Marquis de Lafayette at the end of May. But things were shifting in the middle Atlantic. The new commander in chief, Sir Henry Clinton, was directed to abandon the American capital at Philadelphia and march his army to the secure base of New York City. With the replenished and newly trained Continental Army hovering in nearby Pennsylvania, Clinton knew the move posed risks. So, he called on Simcoe to help screen the force.

Rare photo of Queens Rangers screening

Rare photo of Queens Rangers screeningThe Queens Rangers were in their element and performed well at their task, covering the withdrawal through the hot, humid fields and woods of New Jersey. In June 1778, Simcoe received word of his promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, a meteoric rise for a British officer and a sign of more to come. The year 1779 would see Simcoe, the Queen’s Rangers, and the kind of warfare they were made for, come to the fore. A series of small actions and skirmishes took place throughout the New York region, but mostly along the North (Hudson) River. On 31 August 1778, he led a massacre of forty members of the Stockbridge Militia, Indians allied with the Continental Army, in what is today the Bronx. His men were known to burn houses, barns, and stores - all actions not unknown to American units in a war that had become one of fire and smoke.

Simcoe employed his rangers aggressively

Simcoe employed his rangers aggressivelyIn June 1779 his rangers successfully spearheaded the capture of Stony Point and Verplank’s Point on the North River. Simcoe’s men soon joined Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion in a successful foray against rebels at Pound Ridge, New Jersey. With two of the top three British badasses commanding, it was hard for the defenders. A series of small actions followed raids, ambushes, skirmishes, and patrols. During one foray, on 17 October 1779, Simcoe himself was ambushed and taken by the New Jersey militia. He was briefly interred and finally exchanged on 31 December. The Queen’s Ranger returned just as General Clinton’s amphibious expedition against South Carolina was commencing.

Rangers go SouthIn the spring of 1780, Simcoe sailed south to support the British siege of Charleston. After a brief siege, the city surrendered in May. In what may have proved an eventful blunder, Simcoe was returned north with Clinton and was soon dispatched to help Hessian General von Knyphausen conduct large-scale thrusts in the Jerseys. His talents and his rangers would have proved more useful in helping subdue the south, as would Clinton’s presence. Instead, after a remarkable start, the southern strategy would begin to unravel in the kind of warfare that demanded Simcoe and his men.

Seige of Charleston

Seige of CharlestonTraitor’s Partner

In another curious turn (sic), in December 1780 Simcoe was assigned to support traitor in chief, British General Benedict Arnold’s powerfully destructive raid through Virginia. He was in-part placed at Arnold’s side to keep a close eye on him. But the two talented leaders and co-bad asses actually got along well together. Brigaded with hessian Jaegers under major Johann Ewald, Simcoe’s command thrashed the hapless Virginia militia in several bold attacks around Richmond. At a place called Point of Forks, Simcoe deceived former General Wilhelm von Steuben and seized a trove of valuable supplies.

Benedict Arnold as a British general

Benedict Arnold as a British general

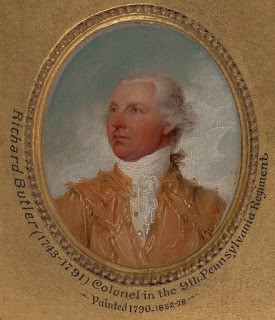

As luck would have it, Simcoe was in the right place, but at the wrong time. Britain’s eight-year effort to maintain its hold on the 13 colonies would end, for all purposes, in the Old Dominion. Frustrated at every turn in the Carolinas, British General Charles Cornwallis marched his depleted and tired army north into Virginia. There, Simcoe and his queen’s Rangers joined him as part of the advance guard. As battle-hardened as the rangers were, they, like so many British units, were finding the rebels reaching parity. Things were definitely “going south.” One example is the 26 June 1781 engagement at Spencer’s Ordinary. There, in an unlikely turn of events, the Queen's Rangers were hotly engaged by Pennsylvania riflemen under Colonel Richard Butler. The precise adversaries they were created to defeat. The rangers abandoned the field, and their wounded, and made a hurried march to Yorktown and the main army.

Colonel Richard Butler

Colonel Richard ButlerWhen they arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis sent them across the York River to secure Gloucester Point. During the summer, the rangers were on a quiet front. This worked well for Simcoe, who had suffered several bouts of illness during the war, exacerbated by his wounding. His health was in decline.

Yorktown under Seige

Yorktown under SeigeWhile ill with a fever, the French blockaded the York River. A week later, the French Admiral Comte de Grasse defeated Simcoe's godfather, Admiral Thomas Graves, and the British fleet in the Chesapeake. Cornwallis's army was trapped. In September the American-French army arrived at Yorktown. Not long after some 1,000 French troops cut off Gloucester Point. The siege was on.

Chesapeake: French fleet drives off British fleet under Simcoe's godfather

Chesapeake: French fleet drives off British fleet under Simcoe's godfatherBut Simcoe was too ill to be of service and his rangers fell under Tarleton’s command. Simcoe was not expected to live. Still, in mid-October, he requested permission to escape with his men on boats to Maryland and fight his way through to New York. He feared many of his men, being deserters, would hang if taken prisoner. But Cornwallis insisted the entire army share its fate. Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe did not die but suffered the ignominy of surrender on the field of Yorktown on 17 October 1781. He was soon paroled and sailed to New York with his unit. The Queens Rangers ultimately went to New Brunswick, Canada, and disbanded in October 1783.

Surrender at YorktownConvalescent and Cupid

Surrender at YorktownConvalescent and CupidIn 1782, the still ailing Simcoe returned home to Devon, England to convalesce. There, he met and married Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim, a wealthy heiress. Her adopted mother, Margaret, had married Admiral Samuel Graves, Simcoe's godfather. So it was a family affair. They had four daughters and a son. By all accounts, he was a devoted family man. Venus, it turns out, was better to him than Mars.

Elizabeth SimcoeAuthor, Author

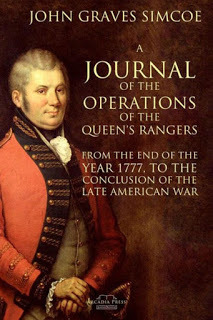

Elizabeth SimcoeAuthor, AuthorIt is beyond the scope of this blog to give details of Simcoe’s post-war life in England. He entered Parliament briefly and offered to raise a ranger unit to fight the French. Simcoe wrote a book on his experiences with the Rangers, titled "A Journal of the Operations of the Queen's Rangers" from the end of the year 1777 to the conclusion of the late American War, self-published in 1787 for distribution to his friends.

Simcoe added Author to his other accomplishments

Simcoe added Author to his other accomplishmentsLieutenant Governor

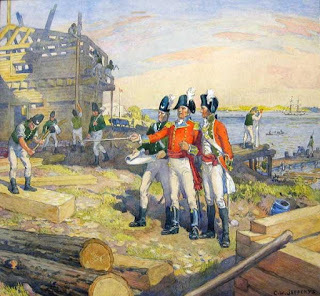

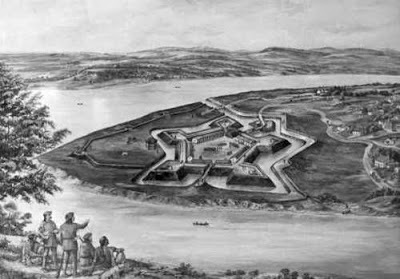

Simcoe returned to North America when he resigned from Parliament in 1792 to accept the post of Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) under Governor-General Guy Carleton. His tenacious personality, so suited to combat, kept him at odds with London. But Simcoe proved a remarkably effective and visionary leader. His ideas were progressive for the period. While cherishing and promoting British institutions, he also promoted American style economics and self-reliance. He promoted agriculture, property rights, and settlement of what was then the Canadian frontier. He built roads.

As Lieut. Gov. Simcoe was a builder

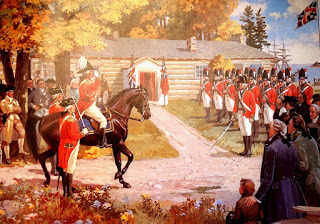

As Lieut. Gov. Simcoe was a builderHe was even-handed with the Indians, supported the loyalists, and pushed for education and culture. He was anti-slavery when slavery was still a thing in the British Empire. Fearing a war with America, he moved the capital from Newark to York on the north shore of Lake Ontario - today's Toronto. To help defend Upper Canada from possible American encroachment or invasion, Simcoe raised a Canadian version of the Queen's Rangers, with himself as its colonel. But illness would once more strike. In 1796, neuralgia and gout spurred a leave of absence to England. Simcoe resigned from his post in 1798 and did not return to Canada.

Simcoe as colonel of the Queen's Rangers in CanadaWar with France

Simcoe as colonel of the Queen's Rangers in CanadaWar with FranceBy 1797, war with France was on again and Simcoe was made governor of Santo Domingo. Simcoe faced a slave revolt with French Republican and Spanish support. He was also promoted to Lieutenant General (the highest rank in the army at the time). Illness again cut his time short. Simcoe returned to England to prepare the defenses of Plymouth against possible French invasion. Simcoe accepted command of the Western District but did not receive another active field command from the Pitt government. When the British were putting together a coalition against Napoleon in 1806, General Simcoe sailed to Portugal as part of a military mission. But his old illnesses caught up with him for the last time. He was forced to return home, where he learned of his appointment as commander in chief of British forces in India.

Governor of Santo Domingo

Governor of Santo DomingoLost Opportunity

India was arguably the most prestigious and challenging overseas appointment for any British military office or administrator. And Simcoe excelled at both. There is no telling how the future of the subcontinent might have fared with him at the helm. But it was not to be. He succumbed to his illness on 26 October 1806 in Devonshire. Lieutenant General John Graves Simcoe was just 54. Simcoe was not the crazed character portrayed on television. Quite the opposite, Simcoe proved himself to be a learned and scholarly warrior and aggressive leader of partisan forces, among the best serving in the Revolutionary War. And a genuine man of peace who helped make Canada one of the best-governed provinces, and nations, on earth. And he might have done the same for India.

Simcoe monument in Toronto

Simcoe monument in Toronto

October 31, 2020

Noble Warrior of Peace

Clash of Empires

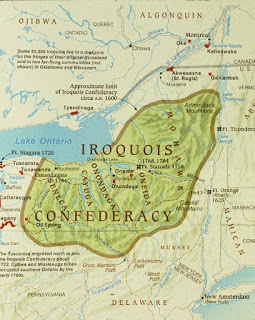

The Native American tribes played an interesting role in the American War for Independence. In some ways, the friction caused by the westward push of European settlers contributed to the friction between the colonists and the British authorities in London, who viewed the Indian Territory west of the Alleghanies as a buffer against Spain. Americans settling the west posed a risk as possible future allies of Spain or a potential cause of war with Spain. The tribes were caught in the middle, especially in the Carolinas and western New York.

In New York, the British had forged strong trade and political alliances with the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederation, who were strong military allies during the French and Indian War. Most of the tribes aligned with the British. Among these was the Seneca nation. And among these proud people arose a leader who would garner laurels in war and praise in peace. His name was Gyantwakia, which in English was Cornplanter.

Seneca Chief

Cornplanter was born in 1740 to a Dutch trader named John Abeel and a Seneca woman in the village of Conawagaus, current Avon, New York. He grew up a Seneca, living among his mother’s prominent family, the Wolf Clan, which was a warrior clan. He led a war party in support of the British in the French and Indian War and by the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, was an established war chief, having made his bones as a young warrior. The Iroquois were among the most capable warriors of all the native tribes and both sides sought their support. Cornplanter, showing remarkable caution, urged neutrality in the white civil war.

Gyantwakia aka Cornplanter

Gyantwakia aka Cornplanter

Raising the Tomahawk

However, as the struggle grew more bitter, he could not keep the Seneca on the sidelines. In August 1777 the Seneca took up the tomahawk on the side of their former allies, the British. By then, the war in New York was at its most intense with General John Burgoyne’s three-pronged campaign to seize New York well underway. It would be a campaign that in many ways would decide the course of the war.

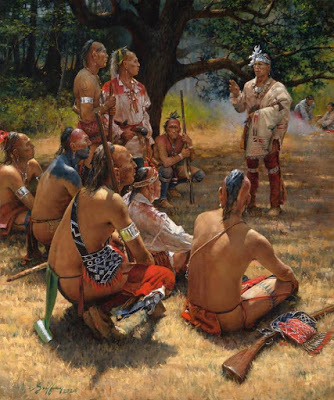

The War Chief addresses the Wolf Clan

The War Chief addresses the Wolf Clan

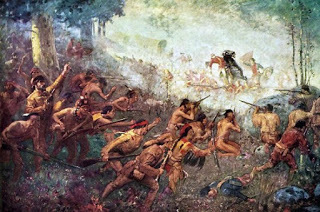

Valley of Death

Once committed, Cornplanter was all-in. He soon led a Seneca war party in support of the expedition of Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger’s thrust east through the Mohawk Valley. Standing between him and his objective, Albany, was the tiny bastion known as Fort Stanwix. In this capacity, he participated in the siege of Fort Stanwix, New York, and then helped plan the ambush of Colonel Nicholas Herkimer’s relief column in the dense woods near Oriskany on 6 August 1777. The ambush was classic Indian-warfare. Cornplanter’s braves surprised destroyed the column and mortally wounded Herkimer. But the approach of another column under Benedict Arnold forced the British to withdraw their regular forces from New York and resorted to hit and run guerrilla raids against frontier settlements.

Seneca ambush at Oriskany mortally wounds Col Herkimer

Seneca ambush at Oriskany mortally wounds Col Herkimer

Frontier on Fire

Cornplanter led many raids against American settlements, particularly at Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania, where on 3 July 1778, his braves ambushed and wiped out a pursuit-force of 400 militia led by Colonel Zebulon Butler. In November, his Seneca supported Loyalist Captain Walter Butler (no relation to Zebulon) in a brutal attack upon Cherry Valley, New York. The Indian and Loyalist raids were so devastating to American lives, property, and morale, that General George Washington ordered a punitive campaign against the Six Nations the following year.

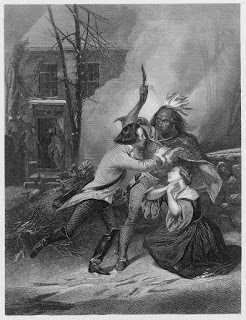

Cherry Valley Massacre

Cherry Valley Massacre

Yankee Retribution

American retribution came with the 1779-expedition led by General John Sullivan, who launched a punishing attack on 28 August defeating the Iroquois and Loyalists at Newtown (Elmira), New York. Sullivan then launched a scorched earth campaign to punish Iroquois villages in the region. Under pressure, he Seneca stood-down for the winter, but the next summer Cornplanter was back on the warpath with raids against the Canajoharie and the Schoharie Valley, New York. At Canajoharie, his band took his father John Abeel prisoner. Cornplanter offered to make him a guest of his clan, but Abeel declined, so the dutiful son released him.

Wolf Clan attacks

Wolf Clan attacksSmoking the Peace Pipe

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, things became complicated for the Iroquois as they struggled to come to terms with the new American government. Cornplanter participated in the many treaty signings, that slowly resulted in the loss of his people’s land. The Iroquois had little leverage against the triumphant Americans, who did not forget their depravations in support of the British. Cornplanter argued in defense of his nation and clan with poise and determination. This caused the more bellicose leaders like Red Jacket to denounce him and forcefully oppose land sales hoping to boost his own standing among the clans.

The Senecas and the rest of the Six Nations stood-down

The Senecas and the rest of the Six Nations stood-downA Moderate Influence

The Ohio (Northwest) Territory burst into flames as tribes along the Ohio River began to chafe at American encroachment and British manipulation. The tribes formed a Great Confederation under such leaders as Little Turtle and had initial success, destroying an American army under Revolutionary War General Arthur St. Clair, in 1791. Because of his bearing and fame as a warrior, the new American government appointed him to represent them with the warring tribes at a great peace conference known as the Council on the Auglaize. But Cornplanter and other moderate native leaders proved unsuccessful. The bitter war continued until former Revolutionary War leader Anthony Wayne broke the back of the confederation at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the Ohio tribes made peace at the Treaty of Greeneville. For his services in attempting to reconcile the western tribes, the state of Pennsylvania granted Cornplanter a large tract of land on the Allegheny River.

Treaty of Greeneville settled Indian Affairs in the Northwest Territory

Treaty of Greeneville settled Indian Affairs in the Northwest Territory

Smoking the War Pipe

With the coming of war with Britain in 1812, the now aged chief Cornplanter offered his services to the United States, but was turned down. However, his son, Henry O’Bail served with some distinction. Cornplanter, one of the fiercest Seneca warriors, now lived peacefully on his land grant for two more decades.

Monument to Chief of the Wolf Clan

Monument to Chief of the Wolf ClanWhen he died on 18 February 1836, the great war chief was widely mourned as a man of peace. Many decades later, in 1871, Pennsylvania decided to honor the noble Seneca and erected a marble shrine on his grave as a symbol of respect and appreciation.

September 28, 2020

The Winter Spy

“I shall constantly bear in Mind, that as the Sword was the last Resort for the preservation of our Liberties, so it ought to be the first thing laid aside, when those Liberties are firmly established.”

Letter from General George Washington to the Executive Committee of the Continental Congress, January 1, 1777

Washington's pen was as mighty as his sword

Washington's pen was as mighty as his sword

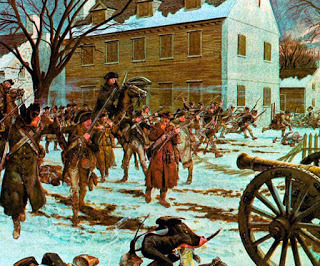

January 1777

The Jerseys are aflame in a deep winter-war!

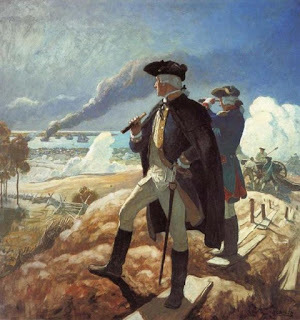

Backs against a frozen river and facing a column of crack redcoats intent on their destruction, George Washington’s army has a serious gut-check. They must outfight or outwit the British to preserve the faltering struggle for independence. With the help of the winter spy, General Washington intends to do both…

Back cover of The Winter Spy, Legatum Books, June 2020

The Winter Spy

The Genesis

This is a book I never intended to write. But as I finished book two in the Yankee Doodle Spies series my research and interest took me the obvious question: what did Washington do AFTER he crossed the Delaware? Quite a lot, as it turns out. So much I became intrigued and crafted a follow-on story to capture the feel and the action of this critical, but little-understood chapter in the American War for Independence.

What did Washington do, after he crossed the Delaware?

What did Washington do, after he crossed the Delaware?

Winter Quarters

In the 18thcentury, armies traditionally did their fighting from late April/early May through Novemberish. In between campaign seasons, some soldiers and officers were sent home on furlough, but most just tried to survive the winter while the armies were replenished and outfitted for the next season of marching and fighting. The British had the luxury of quartering many of their forces in towns and cities, utilizing stores, shops, stables, public buildings, and private dwellings.

Gen Steuben drilling American troops at Valley Forge

Gen Steuben drilling American troops at Valley Forge

For the Americans, winter quarters were usually a painful ordeal of cold, disease, and starvation. For the British, a time of relative comfort in between numbing military chores. Of course, both sides would have to mount guards and sentries. Some patrols were sent out. And during the Valley Forge encampment in 1778, winter quarters became a training ground with the arrival of General Steuben as Inspector-General und Drillmeister.

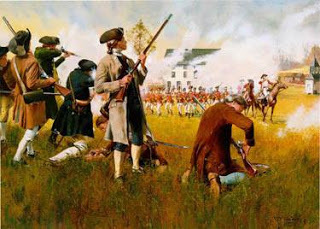

Winter Action

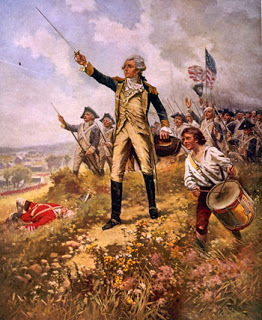

My readings for my second novel, The Cavalier Spy opened my eyes to the actions General George Washington took following the Battle of Trenton: two pitched battles (2nd Trenton, Princeton), plus lots of skirmishing, marching, and suffering before his ever-dwindling army reached its final destination at Morristown, New Jersey. And that choice was very strategic. His actions forced the British to withdraw most of their outposts in the Jerseys, leaving them clinging to the area around Brunswick, the Paulhus Hook (Jersey City) as well as their main strongholds in Staten Island, Long Island, and the Island of New York. With the British in winter quarters, most armies would have hunkered down, licked their wounds, and reoutfitted. The selection was strategic because Washington could observe enemy activities with his forces safely ensconced behind the Watchung Hills, prepared to move in whatever direction the British marched in the spring. That was the original plan.

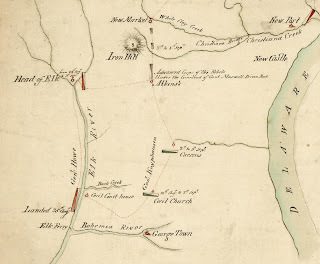

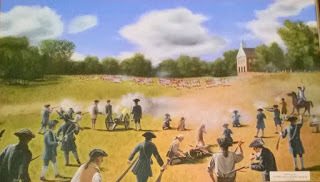

Princeton was one of two actions fought in a many days

Princeton was one of two actions fought in a many daysBut as the British launched foraging parties into the Jerseys to purchase or requisition foodstuffs, the Jersey militia took action. Small parties were ambushed, engendering larger foraging parties and larger ambushes. The numbers grew to the point where Washington allowed some of his Continental regiments under the likes of Generals Philemon Dickinson, William Alexander (Lord Stirling -an American who claimed a Scots peerage) and Ulster-born William “Scotch Willie” Maxell. By the end of this winter of discontent, the British had lost about as many men killed or wounded during “winter quarters” as they did in the previous three pitched battles. Losses British commander-in-chief, General William Howe could not afford.

Gen William Alexander - Lord Stirling

Gen William Alexander - Lord StirlingThe Plot

No spoiler alerts here – read the book! But needless to say, Lieutenant Jeremiah Creed and his White Knights are thrown into action once more, operating in and out of the Continental Army. They again clash with the ruthless British dragoon, Major Sandy Drummond, who continues to leverage his intelligence network to break the rebellion. Along the way, a variety of soldiers and citizens clash, make friends, make enemies, fall in love, and struggle to stay sane during the time that tried men’s souls. Woven into the plot are two themes: the bonding of men in conflict and the war’s impact on families. And, there is always the weather. Winds that can cut a man in two, frigid temperatures, and ice-covered roads and rivers play a significant role in a story that, after all, was named for them.

The Book

All three books in the Yankee Doodle Spies series are published by Legatum Books.

The Winter Spy can be found at Amazon in Paperback or Kindle.

August 30, 2020

Matriarch of Spies

Immigrant Patriot

Like so many of our first patriots, Lydia Barrington was born in Ireland, specifically Dublin, in 1729. At the age of 24, she met and married William Darragh, the tutor son of a clergyman. Not long after the couple emigrated and landed in Philadelphia where they became respected members of the local Quaker community. Although somewhat petite and frail, Lydia took up the trade of mid-wife and, as was common with many women of the time, did sewing on the side. Lydia and her husband led a prosperous and comfortable life in Philadelphia, and their large family five of nine children surviving childbirth) attests to it. The steady Quaker, Darragh became alarmed when one of her sons turned from the Friends to join the Continental Army with a commission as a lieutenant in the Second Pennsylvania Line. The Society eschewed any member who took an active role on either side, especially a military role.

Philadelphia in the 1700s

Philadelphia in the 1700sAn Occupied City

As with so many Americans, life changed when the war came to Philadelphia. In October 1777, the British army under General William Howe occupied the erstwhile American capital. By chance, Lord Howe established his headquarters in the home of the patriot rebel leader, John Cadwalader, just across the street from the Darragh residence at 177 South Second Street. At some point, Howe demanded use of the Darragh parlor for staff councils and private meetings. Most war plans of the age were developed by “councils of war,” so this was a big deal. And a big opportunity.

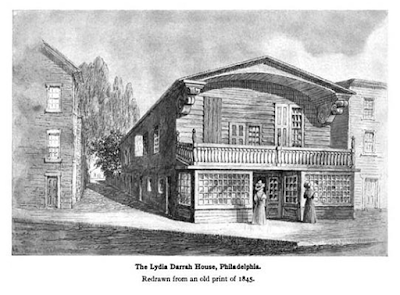

Darragh's House

Darragh's HouseMaking of a Spy

Just who recruited Lydia to espionage and how, is uncertain. What was her motivation? Her son’s military service? Concealed patriotism? Anger at the British occupation? Whether volunteer or recruit to espionage, she clearly became part of an established network. Despite lack of formal education, Lydia had a brilliant mind and was incisive politically and perceptive to things going on around her. She was gifted with a remarkable memory as well. Perhaps her greatest asset, at least for the service she would do for her country, was her unassuming demeanor. The ability to hide in place.

Lydia's family operated at the center of

Lydia's family operated at the center of British occupied Philadelphia

Family of Spies

During the period of occupation, Lydia’s nurse activities enabled her to move freely through British lines. But soon her growing family was involved in helping the cause by providing intelligence from the very center of the British high command in North America. During the winter of 1777 – 1778, the occupation of the rebel capital gave the appearance of British ascendancy and the inevitable destruction of the rebellion. After all, Washington’s pitiable army was holed up on the frozen plains of Valley Forge. While the British had a surfeit of everything, the rebel army was withering away from lack of food, clothing, medicine, and other supplies. The British let their guard down, holding their meetings with the diminutive nurse in the background. And of course, they knew that the Darragh’s, as practicing Quakers, could not, would not support either side in the war nor take part in any acts contributing to the war. Lydia was able to listen in on most of the meetings and discussion that took place in her parlor. Then she quickly dictated what she heard to her husband William, who carefully recorded the information in special shorthand on small strips of paper. Her seamstress skills were a critical piece of her tradecraft. Lydia would stitch the thin strips of paper into buttons on her 14-year-old son John’s coat. That done, she dispatched John as a courier. John would steal through the British lines and rendezvous with his older brother Charles, who was with Washington’s army. Charles understood the shorthand and transcribed the pieces and turned them into intelligence.

Lydia Darragh: Nurse, Seamstress, Spy

Lydia Darragh: Nurse, Seamstress, SpySecret Mission

But the spy ring’s MO and tradecraft would not play a part in what is considered Lydia Darragh’s boldest achievement. On 2 December, Lydia and her family were suddenly ordered to their rooms while an important meeting took place. An emergency council of war took place. This was before the Continental Army had settled in Valley Forge. Washington was still lingering near the capital hoping for an opportunity to take some action before both sides settled in to “winter quarters.” Undeterred, and perhaps stirred, by the urgency of the British, Lydia put her ear to a keyhole and listened in as General Howe gave detailed instructions to his commanders. She overheard the British commander in chief give orders for a multi-column movement against General Washington. The date for the planned ambush was 4 December. The strike was to catch the rebels unaware and disperse their army and perhaps nab Washington in the attempt.

General Howe's secret plans to surprise and destroy

General Howe's secret plans to surprise and destroy the Continental Army would spur a bold gambit

She would not leave this critical mission to her young son. Instead, she developed a quick “cover for action” and slipped out of town on 3 December with sacks hoping to replenish them with flour at a mill near Frankford, which was between the opposing army lines. The risk was great as patrols by both sides roamed the area. And it was a 13-mile trek in winter. Undeterred, she indeed went to Pearson’s Mill and left the empty sacks for the owner to fill. She would pick them up on her return. Her cover thus established, Lydia continued on her real mission: deliver the British plans to the American forces.

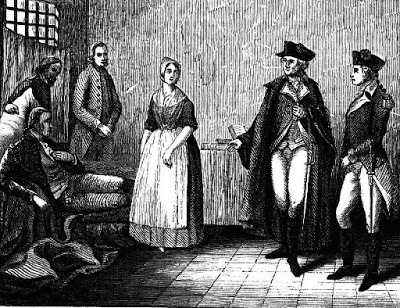

Clandestine Meeting

There are two versions of what happened next. In one, by happenstance encounters a friend, Colonel Thomas Craig, along the road, she told him what she had learned and he galloped off to report to Washington. Lydia then, secured her flour and made her way home. In the other version, Lydia makes her way to a tavern called, The Rising Sun. There, she met with Colonel Elias Boudinot, Commissary-General of Prisoners, but who also operated as an intelligence officer. Allegedly, Lydia walked into the pub and handed him an old tattered needlebook and left. When he searched the book, Boudinot found a roll of paper in one of the pockets. The paper indicated General Howe was going to attack Whitemarsh the next morning with 5,000 men, 13 cannons, and 11 boats on wheels. Boudinot mounted his horse and galloped to Washington’s headquarters. He provided her report to Washington but protected Lydia’s cover by naming “captured prisoners” as his source. This is evidence of the critical role Lydia and the Darragh family played in providing intelligence from Philadelphia. The fact that Lydia knew Boudinot might be at the tavern is a further indicator of the sophisticated nature of the spy ring. I tend to favor the latter version.

Darragh at The Rising Sun

Darragh at The Rising SunAn Army Saved

The intelligence brought by Lydia, really a form of indications and warning (I&W), enabled Washington to prepare the Continental Army, which repulsed General Howe’s “surprise” attack at White Marsh. The multi-day battle saved the army and the cause, enabling it to eventually settle at Valley Forge. The British returned to Philadelphia in disgust.

The series of skirmishes at White Marsh

The series of skirmishes at White Marshended the 1777 campaign with a modest

American victory

A Critical Source

Upon her return, Darragh was questioned by the British who suspected treachery. She was able to disarm them and convince them she was not aware of their plans. But Lydia and her family continued to pump information from the heart of the British high command throughout the winter. As Washington trained the army at Valley Forge, reports from the capital were critical as he prepared for the spring campaign he knew was coming. So the commander in chief was not caught off guard when Howe was relieved of command in the spring and the British Army left Philadelphia on 18 June of 1778. The departure of the British ended the need for the spy ring and Lydia and her family’s service faded into the shadows like so many effective clandestine operations.

Darragh's espionage continued into 1778

Darragh's espionage continued into 1778Banned by The Friends

In June 1783, William Darragh died. The Society of Friends was not so friendly when rumors of the Darragh family’s role began to circulate. The Friends expelled Lydia later that year. Her oldest son John had already been expelled in 1781. In 1786, Lydia moved from South second Street into a new house and with her children ran a store there until her death in 1789. She was laid to rest with other family members in a Quaker cemetery not far from where she lived out her post-wat life.

Lydia returned to a "normal" life after

Lydia returned to a "normal" life afterthe war, but lost her standing with her "Friends"

Shadow Heroes

As with so many of the espionage and covert actions of the American Revolution, Lydia Darragh's tale came under scrutiny. Darragh’s daughter Ann published the story of her mother’s spy work in 1827. But many were suspicious of the tale and discounted the veracity. Speculation subsided in 1909 when Elias Boudinot’s memoirs were published, corroborating Darragh’s role. In the memoir, he wrote of a woman who fit Darragh’s profile although he, for obvious reasons, did not mention her by name. And General Washington himself often lamented the inability to reveal and properly thank all those first patriots who served in the shadow war, unable to gain recognition or recompense for their risks. I for one think Lydia Darragh and her family are among those shadow heroes.

Elias Boudinot's memoirs pointed a light

Elias Boudinot's memoirs pointed a lighton Lydia Darragh's wartime espionage

July 31, 2020

Right Hand Man

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies will continue with the theme of profiling Revolutionary War personalities who play a role in my upcoming novel, The Winter Spy. Coincidentally, we will once more profile a native of Ireland, this time our first-patriot is from the south.

School and Service

Edward Hand was born into a prominent Anglo-Irish family in King’s County (now Offaly), Ireland, on December 31, 1744. His family was able to send him to Dublin’s Trinity College, where he studied medicine and received a surgeon’s certificate in 1766.

Trinity College

Trinity CollegeTrue to the Irish way, rather than a 5-yeart apprenticeship, young Edward joined the 18th Regiment of Foot (later known as the Royal Irish Regiment) of the British Army, as a surgeon’s mate. In 1767, his regiment sailed from Cobh (Cork) to the colony of Pennsylvania. The regiment was quickly marched west to garrison the area around Fort Pitt ( today's Pittsburgh). On the road they passed through Lancaster, in the heart of today’s Amish country. Hand was impressed with the beauty and promise of the region and it would play a role later in his life.

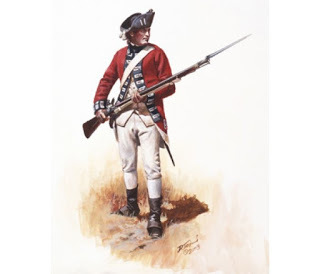

Private of the 18th Regiment of Foot

Private of the 18th Regiment of FootFrontier Doctor

Edward Hand the surgeon’s mate took an interest in some of the local native tribes, particularly their use of plants for medicine. Surgeon duties must have not been too taxing as Hand became interested in land speculation. He also made the acquaintance of a Virginia planter named George Washington, who visited Fort Pitt as colonel of the Virginia militia in 1770. The two hit it off and bonded, which would have a positive impact on young Hand’s future. As tensions grew between the Americans and the British government, the 18th was pulled back east to Philadelphia. Here, Hand witnessed the buildup of resentment and the growing calls for liberty among the people of Philadelphia. As with many British officers, he evinced some sympathy for the growing cause.

Ft Pitt was the key British bastion in the west

Ft Pitt was the key British bastion in the westDomestic Tranquility

Although Hand was able to afford an ensign’s commission by 1772, he did not hold it long. He sold off his commission for some 400 pounds in 1774 and moved to Lancaster, where he set up a private practice. He quickly assimilated into the local community. His medical practice took off, and he was financially set, as his land investments on the frontier had paid off. He was welcomed into Lancaster society, and through a local judge met 23-year-old Katharine (Kitty) Ewing. Kitty’s parents, Captain John Ewing and Sarah Yeates, were one of Lancaster’s most prestigious families. She and Hand married in March, 1775. Events of the next month would soon take him far from his new bride.

Lancaster

LancasterThe Surgeon Rebel

Over the previous year, Hand had become involved with the local patriot cause. So when the call to arms went out after Lexington and Concord, Doctor Hand was named a lieutenant colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles. This band of crack shots marched with other regiments gathering from throughout the colonies to face the British ensconced in Boston. Hand quickly developed a reputation for working directly with his men, making him well-liked by the soldiers he led. Colonel Hand’s riflemen soon gained a reputation as expert marksmen but wildly undisciplined. Hand nevertheless performed capably and eventually smoothed out the rough edges of the troops. Ironically, Hand's old regiment, the 18th, was part of the British garrison that abandoned Boston to the rebel beseigers. In March 1776, he was appointed colonel in command of the regiment when it was re-designated the 1st Continental Line.

Colonel Hand's Pennsylvania Rifles sniping skills were put to

Colonel Hand's Pennsylvania Rifles sniping skills were put togood use during the seige of Boston

Stopping Cornwallis

Hand and his men served well during the New York campaign of 1776. But his hallmark achievement of the campaign was his masterful handling of his troops and canny use of the ground near Pell's Point at Throg’s Neck on October 12, which helped prevent disaster. Under his steady hand (sic), his riflemen coolly shot up the advancing British, completely thwarting a landing by General Charles Cornwallis. Hand’s men moved quickly, torching the bridge over a small creek and placing themselves behind a wood stack. From this vantage position, Hand’s riflemen sniped at the regulars marching steadily into their field of fire and successfully held off a vast force until more Americans came up. Hand’s measured application of firepower allowed Washington’s main army to escape. After similar good service at White Plains, Hand’s regiment retreated with the dwindling Continental Army across New Jersey that winter.

Hand's Pennsylvanians stymied Lord Cornwallis's

Hand's Pennsylvanians stymied Lord Cornwallis'sBritish regulars and Hessians at Pell's Point

His next battlefield masterpiece would soon come, and again at the expense of Lord Cornwallis. On the cold day of 2 January 1777, Hand again stymied Cornwallis’s advance, this time at Assunpink Creek, near Trenton. This action is where Edward Hand appears in The Winter Spy. His masterful handling of several regiments thrown together to slow the British column enabled his friend, General George Washington, escape a British trap and take Princeton. Hand’s performance was noted and Washington soon recommended him for promotion to brigadier general, which was approved on 1 April, 1777. At the time, that made Edward Hand the youngest general in the Continental Army.

Hand's delaying action helped Washington's army

Hand's delaying action helped Washington's armydefend Assunpink Creek from another onslaught

by Lord Cornwallis

A New General, an Old Doctor

What to do with a new general? Well, since he had knowledge of the west, Washington soon dispatched Hand to the place they first met. Brigadier General Hand reported for duty at his old post, Fort Pitt, where he had a challenge protecting western Pennsylvania from pro-British Indians and Loyalists. But Hand was immediately faced with something more dangerous than the marauding tribes and Loyalists - an outbreak of smallpox. Switching hats from General Hand to Doctor Hand, he had a hospital built to quarantine and treat the afflicted. Hand even donated six acres of a 331-acre plot of his own land in Westmoreland County for the site. The “smallpox hospital” was a log building, two stories high and three rooms on each level, guarded by ten surrounding blockhouses for its defense.

Hand's organizational skills garnered support

Hand's organizational skills garnered supportfor Colonel George Rogers Clark's campaign

Hoping to take the offensive against the hostile British allies, he attempted to send expeditions against the tribes in the Ohio River. However, he could never muster enough men and supplies until February 1778. In the dead of winter Hand assembled 500 men, but the column was doomed to failure. But Hand was able to provide critically needed assistance to Colonel George Rogers Clark whose campaign in the Illinois territory was instrumental in breaking British power in the west.

Returning East

Frustrated in the western backwater, Hand requested and received a reassignment back east. Along the way he found time to visit Kitty in Lancaster. From there Hand travelled to Albany, New York where he assumed command of the Northern Department. As such, he provided support to General John Sullivan’s punitive expedition and conquest of the Iroquois heartland in 1779, a more successful but no less tragic foray against the natives of New York.

Sullivan's campaign against the Iroquois was as tragic

Sullivan's campaign against the Iroquois was as tragicas it was successful

Spy Catcher

No, he was not really a spy-catcher. But Hand was selected by General Washington to be part of the “blue ribbon” assembly of officers assigned to sit on the court martial of British Major John Andre, the officer who recruited American traitor Benedict Arnold. Hand was in the company of such luminaries as Nathanael Greene, Arthur St. Clair, Steuben, Lafayette, Henry Knox, John Glover, and others. On 29 September 1780, they held André as guilty of being behind American lines "under a feigned name and in a disguised habit" and ordered that "Major André, Adjutant-General to the British Army, ought to be considered as a Spy from the enemy, and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations, it is their opinion, he ought to suffer death."

Major John Andre's court martial had an all-star

Major John Andre's court martial had an all-starcast of jurors, including Edward Hand

The Right Hand