S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 8

April 30, 2020

The King’s Engineer

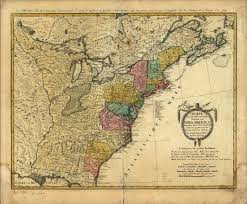

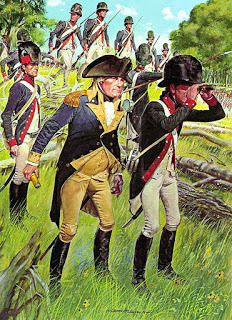

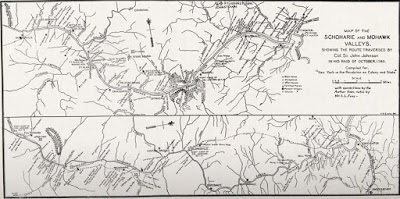

The struggle for North America during the 18th century featured an array of gallant and industrious men from frontier woodsmen, hearty yeoman farmers, professional soldiers, wily politicians as well as the merchants, tradesmen and famers whose industry financed and supplied them. There is another category, one critical to the building of empire, especially an empire carved from wilderness – the engineer. Skilled at planning, surveying, and map-making, engineers connected people to the land. And warfare in North America, was about land and shaped by the land. Geography drives history.

Montresor would spend most of his

Montresor would spend most of hismilitary career in North America

Servant of Empire

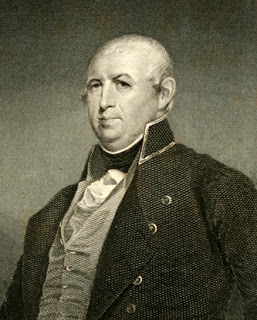

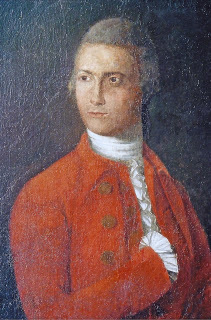

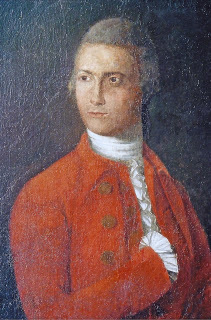

James Montresor

James MontresorOne such engineer was John Montresor. Montresor was the son of a British officer of French Huguenot roots, James Gabriel Montresor. John was born in 1736 on the key British base at Gibraltar. The senior Montresor was chief engineer at the time. John spent four years (1746-1750) at Westminster school in England. When he returned to Gibraltar, his father instructed him in the principles of engineering and took him to North America when he was named chief engineer for General John Braddock.

Fighting the French and Indians

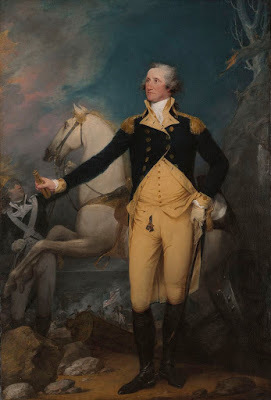

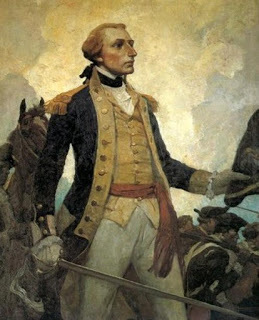

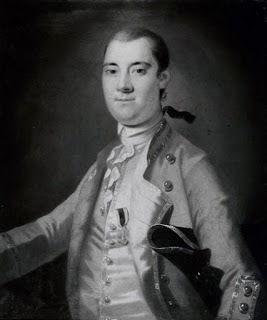

General Braddock

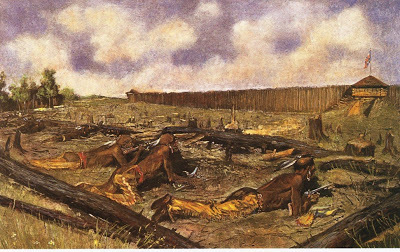

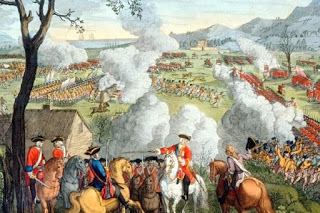

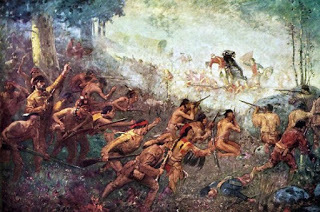

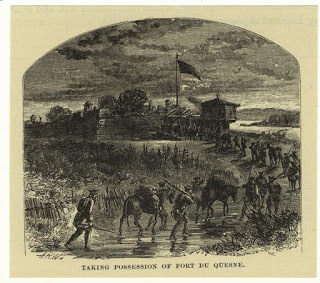

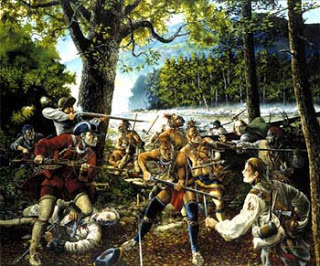

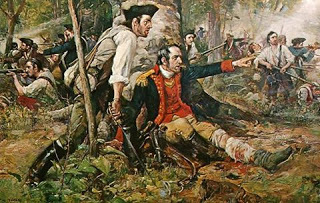

General BraddockJohn Montresor was commissioned an ensign in the 48th Regiment of Foot in March 1755 and was appointed engineer in June. The Braddock campaign against Fort Duquesne is storied (see Yankee Doodle Spies Blog Post: Road of Destruction). The defeat of Braddock’s column by native warriors and French soldiers at the battle of the Monongahela, and the Braddock's death had a chilling affect on the British effort. It also made a hero out of young George Washington. Young ensign Montresor saw action in that battle and was himself wounded during the massacre.

Montresor was wounded at

Montresor was wounded atthe Battle of the Monongahela

Promoted to lieutenant, Montresor was sent to New York, the main theater against the French. His engineering skills were honed by his construction of Fort Edward. In 1757 he served Lord Loudoun (British commander in N.A.) in a failed campaign against the mighty French bastion at Louisbourg. The failure did not put a dent on his career.

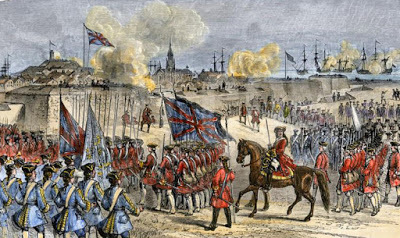

Montresor's engineering skills helped

Montresor's engineering skills helpedsecure the fall of Louisbourg

The following year John received his commission as practitioner engineer and gave up his commission in the infantry. From a career perspective, he took the road least taken. Engineers were critical in modern warfare but rising above major was rare and certainly no path to general. But then as today, engineers favor the work over advancement. That summer he joined General Jeffery Amherst’s army in another go at Louisbourg. As an engineer, he played a key role in the siege of the fortress. Montresor remained in Nova Scotia and in March 1759 performed a reconnaissance around the Bras d’Or lakes.

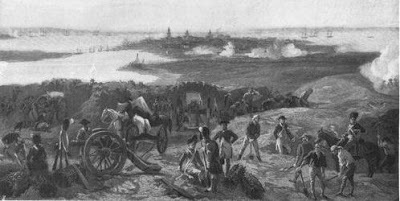

British infantry scaling cliffs to

British infantry scaling cliffs toreach the Plain of Abraham during the

Battle for Quebec

Montresor’s skills were noted, and he was soon sent to join the army forming under General Wolfe in its successful but tragic (commanders on both sides mortally wounded) campaign against the capital of French North America, Quebec.

British General Wolfe died in battle for Quebec,

British General Wolfe died in battle for Quebec, his opponent General Montcalm was also mortally wounded

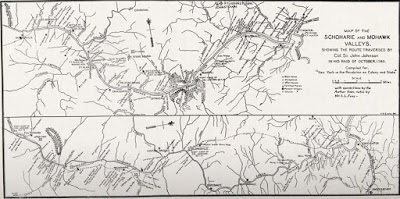

Carving out a New Land

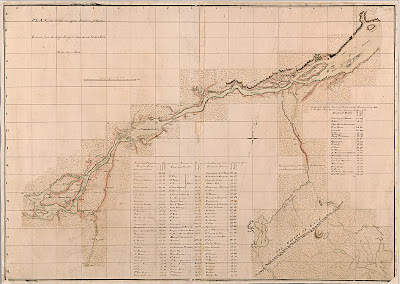

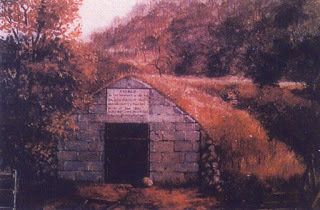

Montresor remained in North America after the Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1763. A rugged new world needed to be mapped and infratstucture of all types need planning and construction - especially forts to protect the newly aquired empire. What better place for an engineer? He stayed with the occupying army, serving newly appointed governor, General James Murray in a series of mapping expeditions of the newly conquered territory. Probably the most important of these was supporting Murray's mapping of the St. Lawrence River. But Montresor was also engaged in constructing forts in the new dominion. Montresor's French language skills also saw him in a pacification role, disarming local militias and ensuring the loyalty of the king’s new subjects.He also found time to explore the wilderness between Quebec and the Kennebec River (Maine). Ironically, his written record would be used by Colonel Benedict Arnold in his campaign against Canada in 1775.

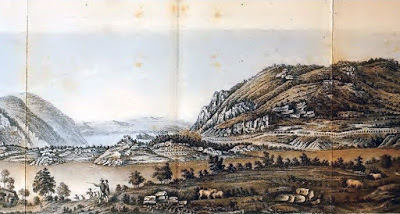

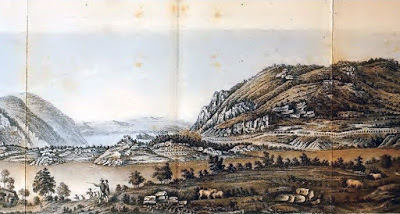

John Murray commissioned a seminal

John Murray commissioned a seminalmap of the Saint Lawrence River

Pontiac's War

In 1763, Montresor was stationed in New York, but the eruption of Pontiac’s Indian rebellion saw him back in Canada. There, General Jeffery Amherst tapped him for a dangerous covert mission: cross hundreds of miles of hostile wilderness to deliver dispatches to the commander of the besieged garrison at Detroit. His knowledge of the land made him the perfect choice to serve as chief engineer for the relief column sent to Detroit the following year. But before heading west, Montresor took the time to constructed forts along the Niagara River.

Montresor braved hostile Indian terrotory

Montresor braved hostile Indian terrotoryto complete his mission to beleagured Detriot

On his return from the Detroit expedition, Montressor was shipwrecked on Lake Erie. Switching to another boat, geek-like the engineer Montressor took the time on his way back to practice a little hydrography, exploring the depth and width of several of the lake’s tributaries along the way.

Montresor made lemonade from lemons

Montresor made lemonade from lemonsusing even a shipwreck to explore Lake Erie

Pause and a Promotion

The arrow of Eros struck him while in New York. Montresor married an American woman, Frances Tucker, in New York City on 1 March 1764. It must have been a good match because they wound up raising six children.

Frances (nee Tucker) Montressor decked out

Frances (nee Tucker) Montressor decked outas Brisih officer.

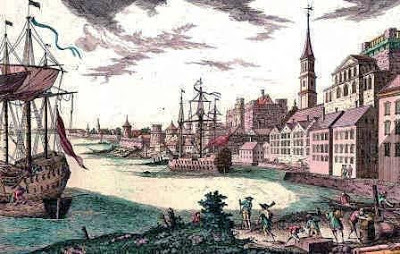

Stationed at Fort George (formerly Fort William Henry) in 1765, he saw the beginnings of the political movement that would eventually lead to insurgency and open rebellion with the rioting in Albany and New York City in in protest to the Stamp Act. Montresor made a voyage to England in 1766. When he returned to America, Montresor was a captain-lieutenant and master of the Ordnance for America. As such, he spent quite some time in the mid-Atlantic region, constructing forts, primarily along waterways such as Boston, New York and Philadelphia. One significant fort guarding Philadelphia on Mud Island would bear his name and be the venue of bloody combat a few years later.

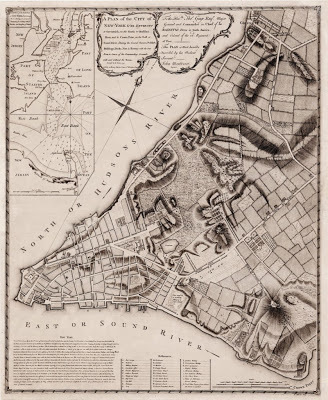

Montresor drew up one of the earlyiest

Montresor drew up one of the earlyiestprofessional maps of The Big Apple

During that inter-war period he managed to find time to survey the boundary between New York and New Jersey and built or upgraded forts and military bases. During his time in New York, he purchased an island in New York’s East River. It was named Montressor’s Island after him but New Yorkers know it as Randall’s Island. Montresor oversaw the devlopment of a map of New York City during his time there.

Chief Engineer

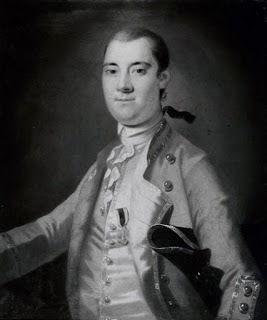

In April 1775 he was in Boston when the outbreak of open war in North America once again changed the trajectory of his career. He was now thrust into the de facto chief engineer for the British forces in America. This resulted in a promotion to captain in January 1776.

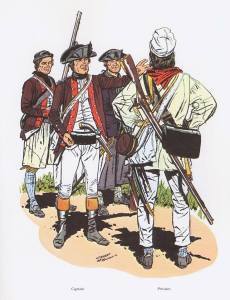

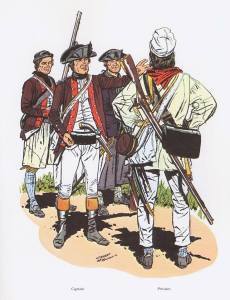

Captain John Montresor

Captain John MontresorFor a while, he seemed to be the Forrest Gump of the British effort – seemingly everywhere and meeting everyone. He secured river crossings for the march on Lexington and Concord and helped relieve the British column skulking back to Boston after being stung by an aroused populace. His engineering skills were put to work in the defense of Boston and he was one of the last officers to leave the beseiged city.

Boston

BostonAs chief engineer during the Battle of Long Island in August 1776, he would have planned the siege works to blast Washington’s beleaguered force out of Brooklyn. Montresor witnessed the execution of Nathan Hale in New York City the following month. He allegedly gave succor to Hale, letting him use his office to write final letters to his family. The British picked him to cross rebel lines to inform the Continental Army of the execution, which is said to have moved him greatly.

Montresor witnessed Nathan Hale's Execution

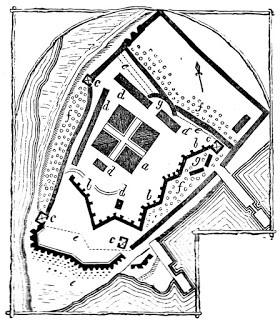

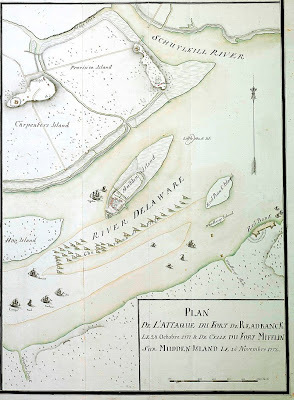

Montresor witnessed Nathan Hale's ExecutionHe gave up his post as chief engineer and served as General William Howe’s aide de camp for a time, but Montressor was later reinstated as chief engineer. When the campaign for Philadelphia was launched in 1777, he was in the thick of operations. He fought during the forage war in New Jersey. He also served at the battle of Brandywine later that year, and accompanied the army to Philadelphia where he rebuilt the garrison's fortifications and later launched the savage series of attacks that destroyed his former Mud Island defenses, which ironically included Fort Mifflin, the fort that once bore his name.

Plans for Fort Mifflin, once known as Fort Montresor

Plans for Fort Mifflin, once known as Fort MontresorWith the British occupation of Philadelphia, he directed the construction of new defenses for the American capital. Montresor also planned the construction of pontoon bridge at Gray's Ferry on the Schuylkill River.

Fort Montressor was renamed Fort Mifflin,

Fort Montressor was renamed Fort Mifflin,giving the King's Engineer the honor of attacking

his own creation

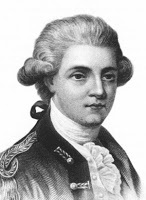

Major AndreA Rapid Closure

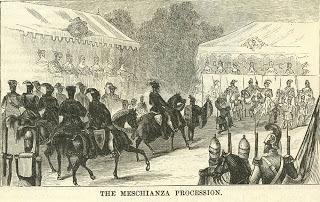

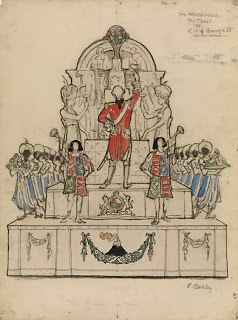

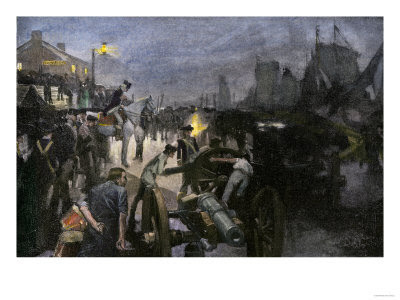

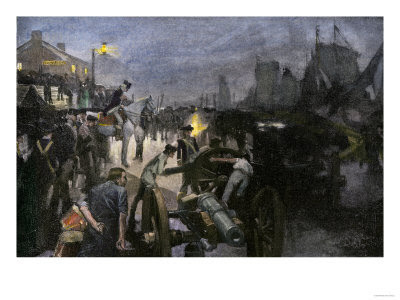

Major AndreA Rapid ClosureAs the British occupation dragged on, the commander in chief, sir William Howe was recalled to England. Montresor, Howe’s former aide, helped Major John Andre (a future spymaster) plan a massive and extravagant farewell celebration called the Meschianza.

The Meschianza included parades

The Meschianza included paradesThis was a series of lavish events with shows, parades, musical concerts and displays, as well as banquets and a ball culminating in a firework show worthy of a Broadway or Hollywood impresario.

Major Andre arranging a Meschianza display

Major Andre arranging a Meschianza displaywith and exotic oriental theme

The spring of 1778 brought a new commander in chief, General Henry Clinton, and at some point that year Montresor was superseded as chief engineer. He returned to England in October where he retired from the army, ending more than twenty years’ service to king and country, albeit a country he spent little time in. But the king’s engineer did not have good time of it in post-army life. Montresor was not happy with his treatment by the army, feeling pique at not receiving a promotion. He blamed the Ordnance office for this and felt his talents and record were unappreciated and unrewarded.

Sir Henry Clinton replaced Howe

Sir Henry Clinton replaced HoweMontresor would follow later that year

It is unclear exactly why he left so abruptly. Perhaps he did not get along with Clinton because of his close association with Howe. But it might have had to do with something more basic – money. There were suspicions he misused his wide discretion in the exercise of his role as engineer. In that position, he controlled considerable funds for the procurement of the equipment, material and manpower for construction projects. The lack of good accounting practices and financial controls may have enabled him to amass a considerable sum of money for his own pockets.

Montresor was a very exacting and demanding engieer, frequentl requisitioning the best materials for his projects. During the construction of the forts around Philadelphia he submitted invoices for extensive materials ultimately denied by the colonial governement. His demading ways may have also crossed him with General Murray at Quebec, and perhaps Henry Clinton.

A Desperate End

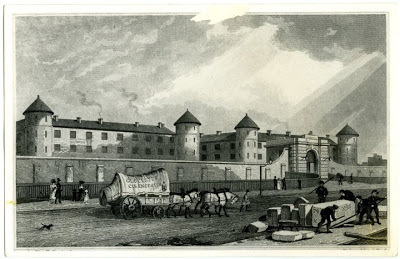

In 1782, his accounts went through scrupulous audit, resulting in him being held liable for £50,000 out some £250,000 in expenses he claimed as chief engineer in America. Despite strenuous appeals by Montresor, he lost. The Exchequer went after his estate, seizing his London residence and property in Kent, ultimately recouping £48,000. Despite his service, Montresor eventually ended up in Maidstone prison, a debtors’ prison, where he tragically died on 26 June 1799.

Debtor's Prisons were the final destination

Debtor's Prisons were the final destinationof the bancrupt in the 18th century

Legacy

Two of Montresor’s sons received commissions in the British Army, despite their father’s difficulties. So the family tradition of service to king and country continued.One is struck by the tremendous contribution Montresor made to the British success in North America in three wars and an inter-war period of consolidation, yet he receives little mention.

This likely was in part due to the relative low regard for the more technical branches in an army drenched with arcane tradition and social stratification. Had he been a man of birth and not merit, or a member of a prestigious regiment, his transgressions might have been overlooked. And of course, as a descendant of French Hugenouts, he was not English. Just saying. This is not to rationalize sloppy accounting or look the other way at embezzlement, merely a period social observation.

Cypher later adopted by

Cypher later adopted bythe Royal Engineers

Montresor, in engineer style, kept a scrupulous journal that pointed out minutiae in day to day operations and conditions. Exact distances and measures were noted. Daily temperatures as well. Those parts of his journal that survive show a man with great attention to detail, but his journal also reveals a bit of hubris as well. Perhaps that hubris led to friction with peers and superiors, and something worse. We will never know.

Surviving Montresor journals

Surviving Montresor journalsprovide a n insight into the man and his times

Published on April 30, 2020 11:04

March 29, 2020

Yankee Doodle Disease

An Age-Old Problem

Throughout the course of history, the bane of most armies was not enemy swords, spears, bayonets, bombs or bullets. Up until at least the second world war, disease and infection killed or disabled more men than battle. Even with today’s Corona Virus Pandemic, there are reports of infections in the military at much higher rates than the regular population. Like so many people around the world, I have been sitting at home and watching a global epidemiological disaster unfold, while trying to ignore the inconvenient fact that I am at the center of it. As are we all. This led me, naturally, to ruminate on the topic in terms of the times of the Yankee Doodle Spies.

The Black Death wreaked havoc and terrorized

The Black Death wreaked havoc and terrorizedover centuries of outbreaks

Disease in War

In a strange irony, war brings people together. Not just the face to face clash of foes but the necessary formation of close—knit units who are thrown together to eat, sleep, train and fight. Camps and garrisons become breeding grounds, especially when hygiene is not maintained. It is that very closeness that makes them so vulnerable when various outbreaks occur.

Gathering of soldiers in military camps was

Gathering of soldiers in military camps wasground-zero for the spread of disease

Epidemics have weakened armies, sometimes rendering them unfit for combat operations, outbreaks have frozen military operations, and of course there is the effect on civilian populations armies come in contact with. Geography plays a role, with both bitter cold and steaming hot climates playing a role in the spread of illness. Swamps, littorals and cities all present environments supportive of various types of disease. And of course, the transports of armies, placing soldiers in strange new lands where they can encounter new diseases and bring their own to impact the locals.

Yankee Doodle Disease

The American Revolution in many ways exemplifies all of these factors. Men from farms and forests thrown together with men from towns and seaports. Undernourished, often poorly dressed and exposed to the elements, these men (and women) often faced a foe worse than any redcoat or Hessian. A foe invisible to the naked eye and who, in most cases, the best medicine of the age did not comprehend and could not combat. Simply put, they faced an array of germs that packed a punch as bad as any .69-inch musket ball or 17-inch bayonet. Diseases such as smallpox, dysentery, and malaria, were commonly suffered by American and British and Hessian soldiers alike. They were an enemy that did not choose sides. Given the close-quarters environments of 18thcentury encampments these diseases would spread through a camp like a windstorm across the high plains.

Disease killed more men than

Disease killed more men thanmusket balls or bayonets

A Different Kind of Battle

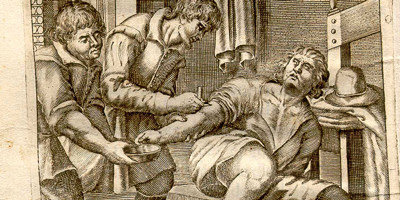

The soldier of the American Revolution faced highly professional armies equipped with the best weapons of the late 18thcentury. But if musket, cannon did kill the soldier, the state-of-the-art treatment for a wound or illness might. Data indicates the typical combatant stood a 98% chance of surviving battle, but around a 75% chance to walk (or limp) from the hospital. Unsanitary conditions, lack of knowledge of vectors, lack of practical remedies combined in a tragically unfair fight for the wounded or sick patriot. No antibiotics, but plenty of bleeding. No anesthetic, but plenty of bullets to bite. And if things really looked serious? Not to worry, there were an abundance of trained surgeons and their assistants who could cut off a limb or bleed the life blood from you.

State of the art medical kit of the Rev War

State of the art medical kit of the Rev WarA Different Kind of Surgeon

During the time of the American Revolution, pretty much anyone could claim to be a doctor and begin practicing medicine as long as they spent a few years of apprenticing with another doctor. Very few were trained surgeons from Edinburgh or London. And even if they were, medical science of the day was based on theories (often bogus) not on real scientific knowledge. This was especially true when it came to illness, especially infectious disease. Doctors of the period thought most illness was brought about by “an imbalance of the humors” -- blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. How to regain the balance in the humors? The typical procedure used was bloodletting or sometimes herbal concoctions to help induce vomiting or bowel movements. Lots of ways to restore the balance.

Bleeding was a common treatment for bad humors

Bleeding was a common treatment for bad humorsA Different Kind of Pharmacist

Medicine in the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies was hard to come by. Prior to the war, medicine, like almost everything else, had to come from England. One reason we rebelled. The war broke that supply chain until the French alliance in 1778. A new supply chain from France brought medicine to America. But even when medicine reached the army camps, most were of limited value, if not dangerous. In a medical field that lacked anesthetics, opiates were the go-to painkillers, followed by hard liquor, and the previously mentioned bullet. For various ailments some surgeons used mercury compounds, lavender spirits, and cream of tartar.

Medicines of the day were, interesting

Medicines of the day were, interestingClimate Change

Disease would strike in any climate. Winter brought seasonal flu and the resultant pneumonia that drowned the soldier in his own lungs. And the years of the American Revolution had some savage winters thanks to a mini-ice age. Many died at Valley Forge, Morristown, Newburgh and other winter cantonments. Summer, especially in the south and in the swamps and low-lying coastal flats, brought the noxious vapors, often malaria but more often the deadly yellow fever. Of course, the vapors, typically called miasmas, were not the vector. Insects provided that. In the case of the latter, the lowly mosquito.

Swamps along the Georgia and Carolina littoral were a breeding ground

Swamps along the Georgia and Carolina littoral were a breeding ground for the"noxious and bilious vapors"that plagued both sides

The war in the south was impacted greatly by disease. It was one of the biggest concerns of the British high command, who had experience sending soldiers into warmer climes. The outbreak of disease chronically weakened General Charles Cornwallis’s army in the Carolinas, impacting battles and strategy. At critical junctures, key lieutenants got ill, as did Cornwallis. When he finally had a reasonably fit and equipped force in hand at Wilmington, he decided to move north to Yorktown and not back into South Carolina in part to get his army into a healthier climate. We know how that turned out.

Disease factored into the strategy

Disease factored into the strategyof Lord Cornwallis, with unpredictable results

Mother of All Maladies

Smallpox was a real killer in the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies. And it could leave permanent scarring when it did not actually kill you. Armies and their camp-followers were very susceptible to the disease and outbreaks threatened both sides. Smallpox in some ways resembles the Corona Virus in its manifestation. It spreads from direct contact, not other vectors such as insects. It can incubate a fortnight before victims are symptomatic. It manifests with some of the similar to Corona and the flu bringing fevers, headaches, and body ache.

But the smallpox piles on with the outbreaks of pustules on the body. Soldiers suffered for about another fortnight before succumbing. It killed one out of three people infected (.3 mortality rate in Dr. Fauci terms) and the survivors take weeks and weeks to recover. Of course, the tell-tale scars make sure you (and those around you) never forget.

The Continental Army suffered outbreaks during the siege of Boston and the defense of New York, again large numbers of soldiers in a relatively confined area. There were two approaches to combating the disease, neither helpful when you are trying to wage a war.

Soldiers from a over a half-dozen states gathered outside

Soldiers from a over a half-dozen states gathered outsideBoston, providing conditions ripe for the spread of disease

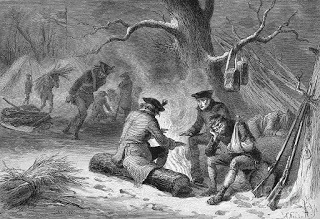

Social Distancing

The first was quarantine, the social distancing of the day. Hard to do when men are organized in unit sets, such as companies, regiments and brigades. Harder to do in winter quarters, where men huddled freezing around smokey camp fires and shared common meals together. Meals often sparse and un-nutritious. The Continental Army could not tele-work. Well, at least not for long.

Winter cantonments such as Valley Forge,Morristown

Winter cantonments such as Valley Forge,Morristownand Newburgh offered little chance for social distancing

Variolation

As controversial in the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies as today, the smallpox was one of the few diseases preventable by inoculation, then called variolation. The variolator used a lancet with fresh matter taken from the pustule of someone with active smallpox. The matter was then scraped on the arms or legs of the recipient, or introduced through the nose. There were risks to this, recipients often developed the symptoms like fever and a rash. But fewer people died from variolation than if they had acquired smallpox naturally. In a study conducted during an outbreak in Boston in 1722, those without variolation died at the rate of 14%, the variolated died at 2% (.14 versus .02 in Dr. Fauci terms). This might have been one of the first instances of data in medical science.

Surgeon-in-Chief

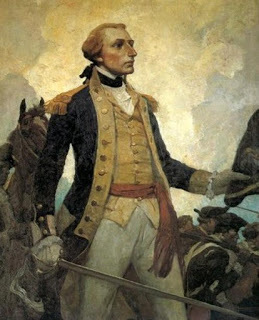

In addition to being commander-in-chief and spymaster-in-chief, General George Washington was the final arbiter on the use of medical procedures to battle outbreaks. He himself had a mild version of the smallpox earlier in life during an expedition to the West Indies. Yet military exigencies in 1775 and 1776 precluded him from ordering wide spread variolation. The British, meanwhile, were using it on any recruit coming to America.

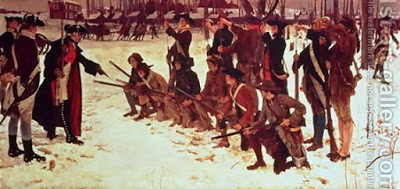

The year 1777 required forced inoculation to

The year 1777 required forced inoculation toprevent the army from wasting away from smallpox

By 1777 the situation changed. A series of outbreaks that year would take as many as 100,00 lives in North America. Only 2.5 million lived in the colonies, not counting the native tribes in the colonies, the Spanish-America and Canada. But a pretty large “numerator” as the good doctor would say. Washington had to take the risk that mass inoculation would not debilitate the Continual Army and finally approved the procedure, beginning with all new recruits. By the following year, however, a considerable number had still somehow avoided the procedure. This time, Washington gave strict instructions that these men would undergo inoculation. Washington made variolation for smallpox "settled science."

Father of Public Health

Just as the ravages of infectious disease helped bring the death knell of the Roman Empire, Medieval Europe and other civilizations, the great outbreaks of smallpox in America during the struggle for independence might well have done what masses of redcoats and Hessians could not do, break the will of the patriots. It is not hyperbole to say that the mass inoculation ordered by Washington saved the army and thus the American cause. And he may be able to add the honorific, the “Father of Public Health” in addition to the “Father of His Country.”

First in War, First in Peace,

First in War, First in Peace,First in Public Health

Published on March 29, 2020 10:45

February 29, 2020

Captain Molly

Female First Patriot

The American War for Independence would not have succeeded without the dedicated efforts of many women, from all walks of life. Besides the obvious morale support women provided the cause, they maintained the farms or ran the shops when the men-folk were with the army or the militia. They raised money and engaged in the day to day commerce that kept the economy going and helped feed the revolution. They organized efforts to sew and knit, providing badly needed garments, blankets and the like for an army poorly served by traditional logistics. Many also followed the gun, joining husbands or sweethearts with the forces as camp-followers. This female first patriot’s service began that way. But it did not end that way. Her name was Mary Chocrane Corbin, and she was indeed, a female bad-ass.

Captain Molly - an original bad-ass

Captain Molly - an original bad-ass

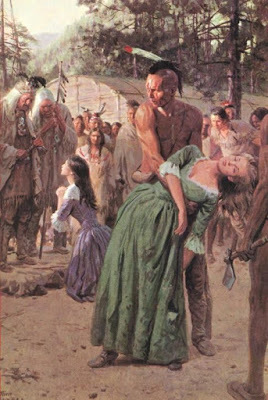

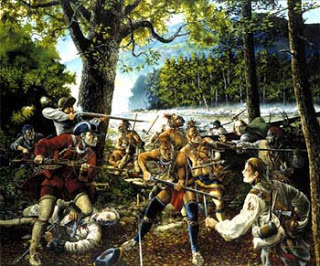

Frontier Orphan

Margaret Chochrane (later changed to Chocran) was born near today’s Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on 12 November, 1751, of Scotch-Irish settlers. Pennsylvania was a battlefront during the French and Indian War, however, and in 1756 and Indian attack changed her life for the worse. In a savage raid so common then, her father was killed and her mother carried off never to be seen again. Margaret escaped but now an orphan, she was raised by an uncle. This was not uncommon in those days. One can only think her hard scrabble youth steeled her for the challenges that lay in store for her.

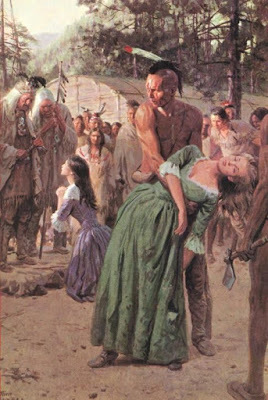

Margaret's mother was carried off in an Indian raid

Margaret's mother was carried off in an Indian raid

Newlywed... New Recruit

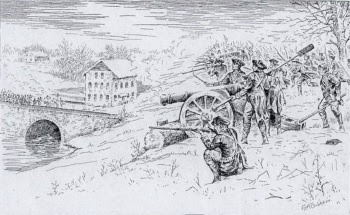

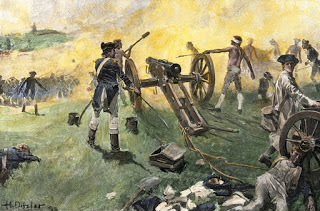

In 1772, at the relatively old age of twenty-one, she married John Corbin, a Virginian who came to Pennsylvania during the war and lingered on. In the run up to the War for Independence John Corbin enlisted in Captain Thomas Proctor’s company of the 1st Continental Artillery. Corbin was a matross, a gunner’s assistant in an artillery crew. As a matross, it was John Corbin’s duty to assist the gunner in loading, firing and sponging the guns.

John Corbin served as a matross, assistant gunner

John Corbin served as a matross, assistant gunner

Follow the Army

Like many women of her day, Margaret joined the army with her husband and served his unit as a camp follower. Camp followers were an essential component of 18th century armies, providing essential services such as cooking, washing clothes and blankets, fetching firewood and water. In combat, they often attended the wounded or carried water for the troops. Without the service of these dedicated women, soldiers of the Revolutionary War would have suffered even more than they did. Especially the Americans, whose logistics often lacked.

Camp Followers were critical to the armies

Camp Followers were critical to the armies

Active Service

Margaret was with the Continental Army in this capacity at New York in 1776. By November of that year General Washington’s army had been driven from Brooklyn, had abandoned most of Manhattan, and had withdrawn to the Jerseys in the face of overwhelming British land and naval power. On Manhattan, the Continental Army was clinging to a small piece of rock at the northern tip of the island. Fort Washington stood high above the North (Hudson) River and the Harlem River, making it a critical piece of land. On November 16, General William Howe ordered a three-pronged bombardment and assault on Washington’s namesake bastion.

Fort Washington

Fort Washington

Captain Molly

The fort’s defenders put up a desperate fight at first, stymieing the efforts of British and Hessian regulars. But soon the endless pounding of guns and determined assaults took its toll on the outnumbered defenders. John was assisting a gunner until the gunner was killed. At this point he took charge of the gun and Margaret stepped in to assist him. Before long, the intense British fire took him down - John Corbin was killed in combat. Undeterred, his wife now stepped in for him.

Margaret was often reported to have a feisty nature. On this day it would serve the forlorn cause at the fort. With no time to grieve her fallen husband, Margaret sprang into action and began serving one of the guns in his place, personally loading and firing round after round at the attackers. But the British soon trained their guns on the belching American cannon. Before long, Margaret herself was struck by a blast of grapeshot from the HMS Pearl firing from the river below the fort. A swarm of lead balls tore her into shoulder, mangled her chest and lacerated her jaw. Several soldiers carried her to the rear where she received what little treatment they could give.

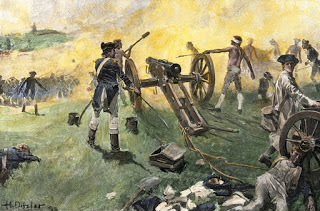

Captain Molly working a cannon at Fort Washington

Captain Molly working a cannon at Fort Washington

Wounded in the Line of Duty

The fort soon surrendered, and thousands of soldiers were marched off to eventual death on prison hulks. But Margaret’s wounds were so severe she was paroled by the fort’s new commandant, Hessian General von Knyphausen. Margaret and the other wounded were ferried across the river to Fort Lee. Bleeding from multiple wounds, and an arm hanging by a thread, Margaret suffered a wagon jolting and bumping along poor roads all the way to Philadelphia. She survived the journey and the wounds, although they would plague her the rest of her life. In addition, she permanently lost the use of her left arm.

Corbin suffered horrific wounds in

Corbin suffered horrific wounds in

the service of her country

Corps of Invalids

In time, Corbin’s condition was made known to the Pennsylvania Executive Council, which granted her a small sum of money and referred her to the Continental Congress. The Board of War, impressed by her reputation as “Captain Molly,” then voted her a soldier’s half-pay for life on July 29 1779. Afterward, Corbin was allowed to join the Corps of Invalids at West Point, New York. Congress created the corps to garrison posts, using soldiers no longer fit for full active service.

Corbin was assigned to the Corps of Invalids

Corbin was assigned to the Corps of Invalids

for the remainder of the war

Honorable Discharge & Second Marriage

She was also allotted one free suit of clothing per year or the equivalent in money. In 1782, Congress allowed her to receive a daily ration of rum due veteran soldiers. As the war drew to a close, she was formally discharged from the military in April 1783. While serving at West Point Margret married again. Her new husband was also an invalid, and the couple lived several years in grinding poverty. When he died, "Captain Molly" lived hand and mouth, often relying on the charity of locals.

The Corps of Invalids garrisoned West Point

The Corps of Invalids garrisoned West Point

Legacy

Our female first patriot died just shy of her 50th birthday at Highland Falls, New York on January 16, 1800 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

The DAR helped move Margaret Corbin's remains to its

The DAR helped move Margaret Corbin's remains to its

final resting place

There she lay until in the early 20th century, Corbin’s remains were subsequently rediscovered and, through the intervention of the daughters of the American revolution (DAR), she was interred at the US Military Academy in 1926 with full military honors. Her grave remains marked by a bronze memorial. Corbin was the first woman of the Revolutionary War to receive disability pension for military service. Ir is fitting that she was finally laid to rest with some of the great military heroes of America's wars.

Margaret Corbin finally laid to rest at West Point's cemetery

Margaret Corbin finally laid to rest at West Point's cemetery

A plaque was erected on the site of Fort Washington in upper Manhattan, in today's Fort Tryon Park.

In an interesting side-note: Mary Corbin’s association with the artillery often causes her to be confused with another gunner, Mary Ludwig Hays, or Molly Pitcher, a common name for camp followers at the time. The other Molly may be the subject of a future Yankee Doodle Spies profile.

The American War for Independence would not have succeeded without the dedicated efforts of many women, from all walks of life. Besides the obvious morale support women provided the cause, they maintained the farms or ran the shops when the men-folk were with the army or the militia. They raised money and engaged in the day to day commerce that kept the economy going and helped feed the revolution. They organized efforts to sew and knit, providing badly needed garments, blankets and the like for an army poorly served by traditional logistics. Many also followed the gun, joining husbands or sweethearts with the forces as camp-followers. This female first patriot’s service began that way. But it did not end that way. Her name was Mary Chocrane Corbin, and she was indeed, a female bad-ass.

Captain Molly - an original bad-ass

Captain Molly - an original bad-assFrontier Orphan

Margaret Chochrane (later changed to Chocran) was born near today’s Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on 12 November, 1751, of Scotch-Irish settlers. Pennsylvania was a battlefront during the French and Indian War, however, and in 1756 and Indian attack changed her life for the worse. In a savage raid so common then, her father was killed and her mother carried off never to be seen again. Margaret escaped but now an orphan, she was raised by an uncle. This was not uncommon in those days. One can only think her hard scrabble youth steeled her for the challenges that lay in store for her.

Margaret's mother was carried off in an Indian raid

Margaret's mother was carried off in an Indian raidNewlywed... New Recruit

In 1772, at the relatively old age of twenty-one, she married John Corbin, a Virginian who came to Pennsylvania during the war and lingered on. In the run up to the War for Independence John Corbin enlisted in Captain Thomas Proctor’s company of the 1st Continental Artillery. Corbin was a matross, a gunner’s assistant in an artillery crew. As a matross, it was John Corbin’s duty to assist the gunner in loading, firing and sponging the guns.

John Corbin served as a matross, assistant gunner

John Corbin served as a matross, assistant gunnerFollow the Army

Like many women of her day, Margaret joined the army with her husband and served his unit as a camp follower. Camp followers were an essential component of 18th century armies, providing essential services such as cooking, washing clothes and blankets, fetching firewood and water. In combat, they often attended the wounded or carried water for the troops. Without the service of these dedicated women, soldiers of the Revolutionary War would have suffered even more than they did. Especially the Americans, whose logistics often lacked.

Camp Followers were critical to the armies

Camp Followers were critical to the armiesActive Service

Margaret was with the Continental Army in this capacity at New York in 1776. By November of that year General Washington’s army had been driven from Brooklyn, had abandoned most of Manhattan, and had withdrawn to the Jerseys in the face of overwhelming British land and naval power. On Manhattan, the Continental Army was clinging to a small piece of rock at the northern tip of the island. Fort Washington stood high above the North (Hudson) River and the Harlem River, making it a critical piece of land. On November 16, General William Howe ordered a three-pronged bombardment and assault on Washington’s namesake bastion.

Fort Washington

Fort WashingtonCaptain Molly

The fort’s defenders put up a desperate fight at first, stymieing the efforts of British and Hessian regulars. But soon the endless pounding of guns and determined assaults took its toll on the outnumbered defenders. John was assisting a gunner until the gunner was killed. At this point he took charge of the gun and Margaret stepped in to assist him. Before long, the intense British fire took him down - John Corbin was killed in combat. Undeterred, his wife now stepped in for him.

Margaret was often reported to have a feisty nature. On this day it would serve the forlorn cause at the fort. With no time to grieve her fallen husband, Margaret sprang into action and began serving one of the guns in his place, personally loading and firing round after round at the attackers. But the British soon trained their guns on the belching American cannon. Before long, Margaret herself was struck by a blast of grapeshot from the HMS Pearl firing from the river below the fort. A swarm of lead balls tore her into shoulder, mangled her chest and lacerated her jaw. Several soldiers carried her to the rear where she received what little treatment they could give.

Captain Molly working a cannon at Fort Washington

Captain Molly working a cannon at Fort WashingtonWounded in the Line of Duty

The fort soon surrendered, and thousands of soldiers were marched off to eventual death on prison hulks. But Margaret’s wounds were so severe she was paroled by the fort’s new commandant, Hessian General von Knyphausen. Margaret and the other wounded were ferried across the river to Fort Lee. Bleeding from multiple wounds, and an arm hanging by a thread, Margaret suffered a wagon jolting and bumping along poor roads all the way to Philadelphia. She survived the journey and the wounds, although they would plague her the rest of her life. In addition, she permanently lost the use of her left arm.

Corbin suffered horrific wounds in

Corbin suffered horrific wounds inthe service of her country

Corps of Invalids

In time, Corbin’s condition was made known to the Pennsylvania Executive Council, which granted her a small sum of money and referred her to the Continental Congress. The Board of War, impressed by her reputation as “Captain Molly,” then voted her a soldier’s half-pay for life on July 29 1779. Afterward, Corbin was allowed to join the Corps of Invalids at West Point, New York. Congress created the corps to garrison posts, using soldiers no longer fit for full active service.

Corbin was assigned to the Corps of Invalids

Corbin was assigned to the Corps of Invalidsfor the remainder of the war

Honorable Discharge & Second Marriage

She was also allotted one free suit of clothing per year or the equivalent in money. In 1782, Congress allowed her to receive a daily ration of rum due veteran soldiers. As the war drew to a close, she was formally discharged from the military in April 1783. While serving at West Point Margret married again. Her new husband was also an invalid, and the couple lived several years in grinding poverty. When he died, "Captain Molly" lived hand and mouth, often relying on the charity of locals.

The Corps of Invalids garrisoned West Point

The Corps of Invalids garrisoned West PointLegacy

Our female first patriot died just shy of her 50th birthday at Highland Falls, New York on January 16, 1800 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

The DAR helped move Margaret Corbin's remains to its

The DAR helped move Margaret Corbin's remains to itsfinal resting place

There she lay until in the early 20th century, Corbin’s remains were subsequently rediscovered and, through the intervention of the daughters of the American revolution (DAR), she was interred at the US Military Academy in 1926 with full military honors. Her grave remains marked by a bronze memorial. Corbin was the first woman of the Revolutionary War to receive disability pension for military service. Ir is fitting that she was finally laid to rest with some of the great military heroes of America's wars.

Margaret Corbin finally laid to rest at West Point's cemetery

Margaret Corbin finally laid to rest at West Point's cemeteryA plaque was erected on the site of Fort Washington in upper Manhattan, in today's Fort Tryon Park.

In an interesting side-note: Mary Corbin’s association with the artillery often causes her to be confused with another gunner, Mary Ludwig Hays, or Molly Pitcher, a common name for camp followers at the time. The other Molly may be the subject of a future Yankee Doodle Spies profile.

Published on February 29, 2020 11:21

January 28, 2020

The Surgeon General from Scotland

Fans of Outlander will immediately see the strange connection this first-patriot has with the main protagonists of the popular books and TV series,. A brawny, hot-headed Scot with a fiery passion meets cool, calculating medical professional who take on the British on two continents. Yet in this case they combined in one person - Hugh Mercer, a man who cut a swathe from the streets of Aberdeen, to the rugged bloody field of Culloden, to the war torn mountains of Pennsylvania and the frozen farmlands of the Jerseys.

General Hugh Mercer

General Hugh MercerThe Streets of Aberdeen

Hugh Mercer was born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, in 1725 to the Reverend William Mercer, a Church of Scotland minister and Ann Monro. He passed through the University of Aberdeen with a medical degree in 1744. That year, he joined the Jacobite army of Prince Charles Edward, the Pretender, and served as assistant surgeon at the disastrous engagement of Culloden in April 1746. He escaped the butchery that followed the battle and after months on the run, fled to America.

Country Doctor

The young surgeon, war-veteran and fugitive settled in present-day Mercerville, Pennsylvania, to ply his profession as a physician. When the French and Indian War broke out in 1755, he set aside his eight years of comfortable medical practice and offered his services to the provincial forces, taking part in several notable actions.

Another Massacre

On the western frontier of Pennsylvania, Mercer helped treat the survivors of General Braddock’s destruction on the Monongahela River. Appalled by the butchery suffered by the wounded, Mercer put aside his disdain for the crown and joined the Britain’s struggle for America.

Punitive Expedition

In September 1756, the newly appointed captain accompanied Colonel John Armstrong on his punitive expedition against the Indian villages at Kittanning and was severely wounded. Cut-off, he survived on his own for two weeks wandering over 100 miles before reaching the friendly outpost at Fort Shirley. His devotion and gallantry were recognized.

Mercer served under Col John Armstrong

Mercer served under Col John Armstrongin western Pennsylvania raid

Fort Duquesne

Two years later he fought as a lieutenant colonel at the capture of Fort Duquesne (renamed Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh) and subsequently commanded there. Mercer's first task was to construct a temporary fort to hold the two forks of the Ohio in case the French returned from the northwest. During this campaign Mercer met and befriended Colonel George Washington of the Virginia regiment. It would be an enduring friendship.

The Old Dominion

The war ended in 1763 and because he had made friends with several Virginians, he decided to settle in a small port town with a small community of Scot expats. Though Mercer arrived in Fredericksburg to establish a medical practice, he found much more. The town filled a void present since fleeing his homeland.

Mercer opened an Apothecary in his

Mercer opened an Apothecary in hisadopted town of Fredericksburg

First Mother's Physician

In addition to practicing medicine, Mercer opened an apothecary in town. Like so many settlers, he bought land. He was physician to George Washington’s mother, Mary Ball Washington and bought the Ferry Farm from her as his family homestead.

One of Mercer's celebrated patients

One of Mercer's celebrated patientswas Mary Ball Washington

Civic Leader

He became active in local issues in town and was a prominent businessman. Along the way he joined the masonic lodge that included Washington and so many other prominent Virginians. To say he was at last comfortable with life is an understatement. But he would soon leave his comfort to follow the drum one last time.

Mercer, George Washington and numerous founders

Mercer, George Washington and numerous foundersbelonged to the Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge

The Minuteman

By 1775 the tensions between Britain and its colonies in North America had morphed from resistance to insurgency and then war. It was only natural the bold freedom-lover Mercer was would throw in his lot with the glorious cause and face his former enemies once more. He became a member of the Fredericksburg Committee of Safety. In September, Mercer was named commander of all minuteman companies in the four counties around Fredericksburg.

Virginia Minutemen

Virginia MinutemenThe Continental

In January 1776 his talents were once more recognized. Virginia’s provincial congress appointed him colonel in the 3rd Virginia Continental Line. He set to work drilling it into a crack unit but that command was short-lived. His old friend and comrade in arms, George Washington, was now commander in chief of the new Continental Army. Mercer enjoyed a fine military reputation, so Washington petitioned the Continental Congress to appoint him brigadier general that June.

Mercer commanded a Continental Line regiment

Mercer commanded a Continental Line regimentbut was quickly promoted to the rank of

Brigadier General

Flying Camp Days

Washington immediately entrusted him to command the so-called Flying Camp, a mobile military reserve. He tried to employ it to support the main army during the New York campaign, but the unit was plagued by desertions, lack of manpower, and supply shortages. The Flying Camp was disbanded that winter.

Fort Lee before evacuation

Fort Lee before evacuationBattle Across the Jerseys

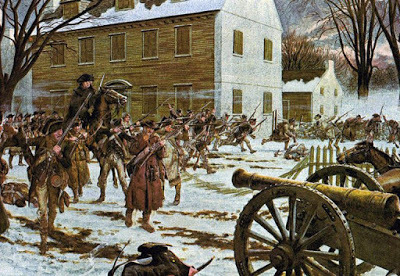

Mercer was also given the task of building what became Fort Lee on the New Jersey side of the North (Hudson) River. Although the fort fell without a fight during the British invasion of the Jerseys in late 1776, Mercer still enjoyed Washington’s complete confidence. He played a prominent role during the daring and masterful counter-stroke at Trenton on 26 December 1776, His brigade played a prominent role in driving the Hessian garrison out of the town where they were forced to surrender in a nearby field.

Mercer commanded a brigade at the crucial

Mercer commanded a brigade at the crucialassault on the Hessian garrison at Trenton

Escape from Assunpink

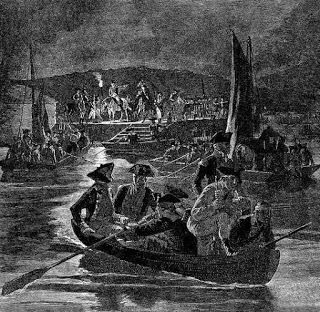

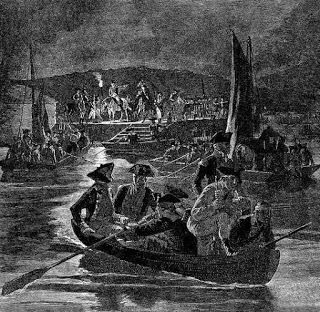

The Americans eventually moved to Assunpink Creek to await the inevitable British counter-stroke by a column of some 5,000 led by Major General Charles Earl Cornwallis. Some say Mercer may have suggested the famous rouse of leaving fires burning. Regardless, the British were duped when the Americans slipped away into the night and got behind Cornwallis’s column and attacked Princeton.

After repulsing Cornwallis's columns at Assunpink Creek

After repulsing Cornwallis's columns at Assunpink Creekthe Americans slipped away in the night

Advance on Princeton

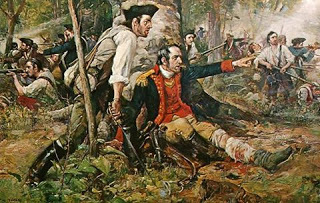

On 3 January 1777, Mercer, leading the advance corps ahead of the main body, ran into a brigade of some 1200 British regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood of the 17th regiment of Foot. A bloody exchange of volleys erupted in the vicinity of Stony Brook Bridge. Rather than retreat under the press of the redcoats, the imposing Scot plunged into battle against the better trained British. But his troops were forced back after stiff fighting.

Mawhood's brigade was all that stood

Mawhood's brigade was all that stoodbetween Mercer and Princeton

Clash and Flurry of Blades

While attempting to rally his men, Mercer was shot off his horse. Refusing to surrender he drew his saber but was overpowered and bayoneted several times by angry British soldiers (who may have thought he was Washington). Fatally wounded, he was then carried to the nearby home of Thomas Clarke, where a British surgeons mate and some local women cared for him. When Washington learned his fate, he reached out to Cornwallis who graciously allowed Washington’s leading physician, Dr. Benjamin Rush, to attend the dying general.

British bayonets mortally wound the gallant Scot turned Yankee

British bayonets mortally wound the gallant Scot turned YankeeFinal Home

The gallant soldier-surgeon Mercer lingered on but finally succumbed to his wounds on 12 January 1776. His body was taken to Philadelphia where he was buried. Had Mercer survived he clearly would have played an even more prominent role in securing America's freedom. But the greater tragedy is this educated and dedicated soldier-surgeon never had the chance to help build the nation whose liberty was paid for by his blood.

Gen Hugh Mercer's grave

Gen Hugh Mercer's grave

Published on January 28, 2020 16:39

December 28, 2019

The Kentuckian

It is time we turn our attention to the south once more. The region is replete with first patriots whose names were legend to the generations following the struggle for independence but are lost in the mists of time. The southern struggle was most remembered by the exploits of Marion and Sumter. But countless others played roles large and small. Not the least of these were those bad asses called the “Over Mountain Men.” Hard-nosed and hard-fisted settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains steeped in hunting, fighting and hard liquor. This edition profiles one of these: Isaac Shelby.

Family of Migrants

Isaac Shelby was born in Hagerstown, Maryland on 11 December 1750. His father, Evan Shelby, hailed from Tregaron, Cardiganshire, Wales, and had come to America in 1734. About 1773, Evan moved his family to the Holston region of what is now upper East Tennessee but was then part Virginia.

In mid 18th century the Alleghenies

In mid 18th century the Alleghenieswere the western frontier

Raised on the Range

Young Isaac grew up steeped in the frontier world of rough and tumble living and fighting. He early learned the use of arms and became accustomed to the rigors of western life. He received a fair education, worked on his father's plantation, occasionally surveyed land, and at age eighteen became a deputy sheriff.

Frontier cabin

Frontier cabinBig Strong Man

Isaac Shelby was a large man, six feet tall, powerful, and well proportioned, with a striking countenance and ruddy complexion. He could endure long hours of work, physical hardship, and great fatigue. Dignified and impressive in bearing, he was nevertheless affable and winning. In short, a natural leader. He was also smart and had obvious executive skills that served him well in peace and war.

Shelby in later life

Shelby in later lifeLord Dunmore's War

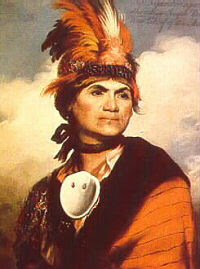

When the Earl of Dunmore, Virginia Royal Governor John Murray. went to war with the Shawnee under Chief Cornstalk, Shelby joined the nearby militia as a lieutenant, serving under his father. On 10 October 1774 young Shelby fought in the Battle of Point Pleasant. He achieved early military success in the battle by charging the high ground on the Indian flank, forcing them to abandon the field. This was just a prelude to things to come.

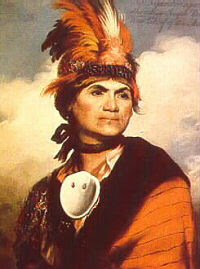

John Murray,Royal Governor of

John Murray,Royal Governor ofVirginia

A Rebel Goes West

The American Revolution went hot in 1775 and by 1776 Shelby had rejoined the militia, this time as a captain. Virginia’s Governor, Patrick Henry, appointed him to a post on Virginia’s western frontier. There he provided direct support to Colonel George Rogers Clark’s thrust into the Illinois Territory. Isaac also played a role in well his father’s victory over the Indian chief Dragging Canoe in a battle on the Tennessee River in 1779.

Shelby provided logistic support to

Shelby provided logistic support toGeorge Rogers Clark's western campaign

Me? A Tar Heel?

Eighteenth century boundaries in this region were advisory at best. When he discovered that his homestead was actually in North Carolina, Isaac became a colonel of militia there. He also won a seat in the state assembly. Although a newly minted Tar Heel, Shelby was in Kentucky when Charleston fell to the British in 1780 and the triumphant and exuberant redcoats began to overrun his state. At word of the new threat he hurried home and raised some 200 men for the cause. He immediately joined forces with Colonel Joseph McDowell to try to block the advance of British General Charles Cornwallis and his Loyalist supporters.

The Fall of Charleston opened up the Carolinas

The Fall of Charleston opened up the Carolinasto the Southern Strategy

Guerrilla Days

His first major test came on 31 July when Shelby and his men managed to surround Thickety Fort on the Pacolet River. His swagger and deception enabled him to bluff the commander to surrender his 94 men. Shelby then joined forces with a band of partisans under Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Clarke. With a combined force of 200 men they attacked a Loyalist outpost at Musgrove Mills. Although outnumbered almost two to one they drove off the Loyalists in a fierce skirmish.

Enter the Counter Guerrilla

These activities posed a threat to Cornwallis’s security, so the British general dispatched perhaps the army’s best guerrilla fighter, Major Patrick Ferguson. But when the patriot army under General Horatio Gates was annihilated at Camden on 16 August 1780, pretty much all resistance collapsed throughout the south. It looked like the British “southern strategy “was going to pay off.

Major Patrick Ferguson

Major Patrick FergusonRun Away

For his part, Shelby withdrew to the west with McDowell and their forces dissolved into the frontier hinterland. There they would wait out events. But local atrocities by Loyalist bands angered the southerners and in a series of partisan and guerrilla actions, they continued resistance.

Partisan militia

Partisan militiaThe Lord's Prayer

Seeking to consolidate the Carolinas under British authority, Lord Cornwallis marched an army into North Carolina in a gambit that would ultimately backfire. With him went Ferguson who issued a bold challenge to the “Over Mountain Men” as the frontier rebels were called. The threat was blunt: submit to the crown, or their homes would be put to the torch. But the men of the west were unimpressed. In fact, this galvanized the frontiersmen.

Major General Charles Cornwallis

Major General Charles CornwallisBand of Bothers, Tough Mothers

Shelby, along with another over mountain man from Tennessee, John Sevier, raised a force of 200 volunteers, rallied at Sycamore Shoals and soon plunged into war torn North Carolina. There they joined forces with Colonel William Campbell. Anxious for revenge, the over mountain men moved hell bent for leather to get Ferguson. The feeling was mutual. The famed counter - guerrilla led a force of some 900 Loyalists itching to subdue the rebels.

John Sevier - another

John Sevier - another Over Mountain Bad Ass

Go Tell it to the Mountain

But the ride was turned on Ferguson, who was surrounded on a stretch of high ground called King’s Mountain (just over the border in South Carolina) and cut off from the main British column under Cornwallis. Withering and accurate fire from the rifles of the westerners devastated the Loyalists. Ferguson was shot trying to rally a defense and soon died. The few who did not taste lead eventually surrendered. Shelby played a conspicuous role in planning and executing the operation and soon became a local hero.

Kings Mountain was a turning point i n the South

Kings Mountain was a turning point i n the SouthDraining the Swamp, with the Swamp Fox

After King’s Mountain, Cornwallis’s strategy began to unravel. But there was more fighting to be done. Shelby joined forces with famed partisan general Francis Marion and assisted in seizing Monk’s Corner. Fighting continued throughout the south even after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in October 1781. But the British and their Loyal allies were beaten.

Francis Marion and his partisan militia

Francis Marion and his partisan militia

The Kentuckian

After the war, Shelby retired to private life, where his wartime heroics resulted in a successful political career. He moved to Kentucky and helped organize the territory, develop infrastructure, improve defenses against the Indians and their British allies. On 19 April 1783, at Boonesboro, he married Susannah Hart, daughter of Captain Nathaniel Hart, one of the earliest settlers of Kentucky. Susannah eventually bore him eleven children.

Susannah Hart Shelby

Susannah Hart ShelbyPolitician, Pundit and Warrior

In 1792 he was elected governor of the recently admitted state. He was a critic of President Washington’s foreign policy. Many westerners wanted a more aggressive stance against the British forts to the west and the Indians. However, he provided unstinting support to Major General Anthony Wayne’s Legion during the Indian campaigns of 1794. In 1812 Shelby was once again elected governor. His military and organizational skills went to work mobilizing Kentucky’s militia for war. In 1813 he personally led a force of 3,500 mounted riflemen north to support General William Henry Harrison’s army near Thames, Ontario. After the war, Congress struck a gold medal in his honor.

Gen Anthony Wayne's American Legion

Diplomat to the Indians

In 1817, he declined President James Madison’s offer to serve as Secretary of War. His last significant contribution to the over mountain region came in 1818 when he, Andrew Jackson, and others negotiated the “Jackson Purchase,” which removed control of the western districts of Kentucky and Tennessee from the Chickasaw Indians. This opened the western region to settlement. To honor this service, the Tennessee General Assembly named Shelby County (Memphis) for him.

President James Madison

President James MadisonA Model for the West

The fighting governor died near Danville, Kentucky in July 1826. He was mourned as a celebrated public servant and soldier. One of the nation’s most remarkable frontiersmen, Shelby provided the model for those later frontiersmen who would forge the Republic of Texas and help solidify America’s western expansion.

Shelby Cemetery is a KY historic site

Shelby Cemetery is a KY historic site

Published on December 28, 2019 09:45

November 3, 2019

The Mechanics

Genesis of Clandestine Warfare

The American War for Independence was the culmination of over a decade of political unrest and discontent with British policies and treatment (real and perceived) of the colonists. Although led by some of the brightest minds of the age, or any age, the movement was also a grass roots movement, which gradually built to a political movement – the idea of the ideas bantered around in taverns, coffee houses, homes and farmsteads.

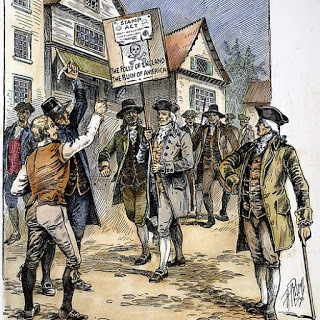

By the early 1770s the movement spurred what was to become an insurgency of sorts. Insurgencies are of their own nature clandestine and they necessitate the development of clandestine activities and the trade-craft (use of spies, secret writing, etc.) necessary for success. As the political side of the patriot movement grew, organizations like “The Sons of Liberty” also sprung up, serving as the action arm.

Boston Ablaze

By the outbreak of rebellion in 1775, the Americans had established organizations necessary to wage the clandestine side of the war as these were already well underway. The British had their counter to this but these activities tended to lag and over time became eclipsed by the Americans’ ability to control the ground in all but those few areas dominated by the British Army and Royal Navy.

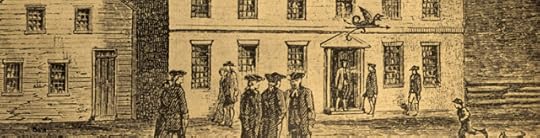

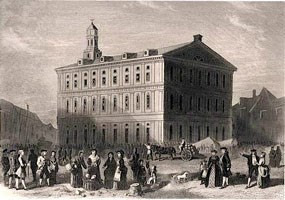

Boston's Fanueil Hall was the site of much

Boston's Fanueil Hall was the site of much

political agitation & intrigue

One of the first clandestine networks established was, of course, in Boston. This was only natural as Boston was the scene of so much political and subversive discourse during the pre- Rev War period. Names like Sam Adams, Paul Revere and John Hancock were legend even then. “Agitprop” became a really effective tool as crowds were whipped up for all sorts of things. In a way, the British missteps in countering all this activity in Boston fueled the flames that eventually burst into a conflagration that scorched the eastern seaboard after April 1775.

Enter the Mechanics

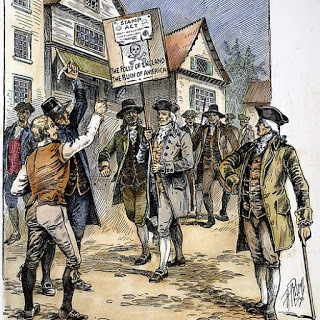

The first patriot intelligence network was a secret group in Boston called the Mechanics. The Mechanics were spawned in Boston from “The Son’s of Liberty" , known famously for their opposition to the Stamp Act and other repressive measures. But the mechanics operated a bit differently. They organized clandestine activities in resistance to British authority. They also gathered intelligence, the lifeblood of the resistance. It began as a group of some thirty “mechanics,” men who worked in hands on trades in and about the city.

Observing counter demonstrators helped

Observing counter demonstrators helped

build situational awareness of British sympathizers

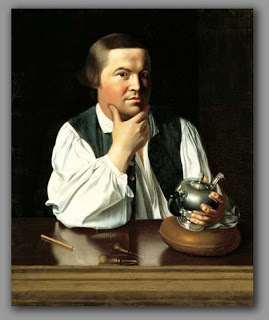

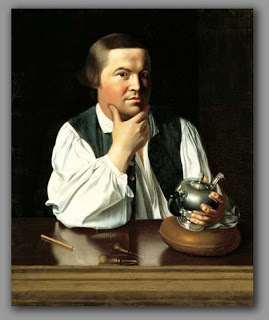

Paul Revere was among the first. By his own words they, “…formed ourselves into a Committee for the purpose of watching British soldiers and gaining every intelligence on the movements of the Tories.”

Paul Revere was one of the craftsmen-spies

Paul Revere was one of the craftsmen-spies

who became know as the Mechanics

The key component is the latter. They realized the key to success was neutralizing British sympathizers early on. Revere further stated, “We frequently took turns, two and two, to watch the soldiers by patrolling the streets at night.” Operating under cover of darkness would be a key component of future clandestine activities right up to today. In addition to observing British soldiers and Tories, Revere and the mechanics served as couriers, the essential oil of any clandestine network. Communications is the Achilles heal of clandestine work so the couriers held a special role. The Mechanics played a key role in countering the efforts to suppress the colonial insurgency.

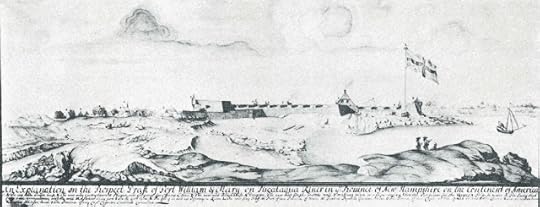

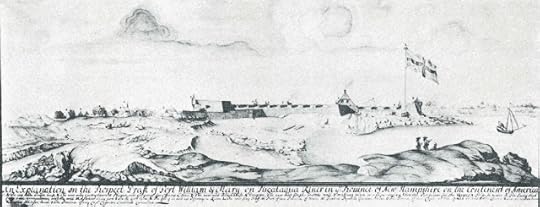

Mechanic Paul Revere alerted General Sullivan of the British intention to seize

Mechanic Paul Revere alerted General Sullivan of the British intention to seize

Fort William and Mary

One of Revere’s first missions as a courier took place in December 1774. He rode to the Oyster River in New Hampshire with a report that General Thomas Gage the British commander and governor, planned to take Fort William and Mary. Alerted by the intelligence delivered by the Mechanics, Major John Sullivan led a colonial militia force of four hundred men in a preemptive raid on the fort. They seized one hundred barrels of gunpowder that were ultimately used by the patriots at Bunker Hill

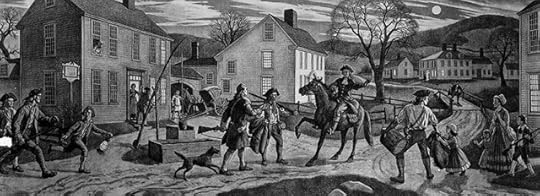

Clandestine Communications

Things really heated up around Boston in early 1775. Both sides became more aggressive and the stakes grew with each month. Through a number of intelligence sources the Mechanics broke the cover established by General Gage for their quick strike on Lexington and Concord. The British counted on secrecy for success. Thanks to the intelligence and warning by the Mechanics, they failed.

The Mechanics' espionage activities

The Mechanics' espionage activities

were a bane to British General Thomas Gage

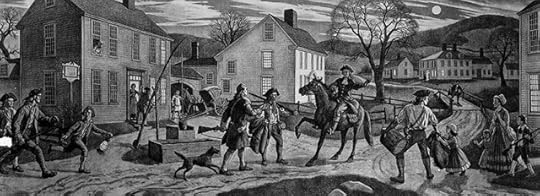

Revere received orders from Dr. Joseph Warren, then head of the local Committee of Safety, directing him with warning the key patriot leaders in the region, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, of the British plan to take them in a secret raid on Lexington. Revere arranged for the signal lanterns at the Old North Church. Working with William Dawes, the two rebel leaders were warned. Riders were sent out to alert the militia and then Revere, Dawes and a Dr. Samuel Prescott went on to warn the militias at Concord of the second phase of the operation – seizing the weapons there.

In addition to Revere, Dawes and Prescott, other secret riders

In addition to Revere, Dawes and Prescott, other secret riders

warned the villages of the approaching British

British capture Revere

British capture Revere

A British patrol at Lincoln almost ended things before they started. During the chase, Dawes was thrown from his horse while fleeing. But Prescott and Revere were taken prisoner. Prescott soon escaped British capture and made his way to Concord, but Revere remained a prisoner. However, the doughty silversmith, resisted interrogation and was soon released and made his way to Lexington where he and John Lowell were dispatched to retrieve a trunk full of incriminating patriot papers at a local tavern.

A Dearth of Knowledge

In a sense, the dearth of recorded knowledge on the Mechanics is a good thing, not for historians but for the nation. Any records kept, were probably very local and perishable. That is, destroyed on completion of the operation. Operations security came naturally to those seeking survival in a clandestine war. But mistakes are made and can be costly. The trunk Revere was sent to retrieve could have provided the British a trove of intelligence that might have snuffed out the flame of rebellion in New England, and thus ended things.

Mechanic reporting intelligence

Mechanic reporting intelligence

on British activities

A curious example of bureaucratic snafu accidentally preventing failure also involves our celebrated Mechanic, Revere. The mechanics evidently received written orders and some sort of remuneration for their expenses. The orders may have been used to get through militia patrols. For whatever reason, Revere only received his orders from Dr. Warren,leader of the local Committee of Correspondence, two weeks after his clandestine ride. Had he had them with him, his role would have been exposed to the British when they searched him. History again might have taken a distinctly different course.

As leader of the Boston Committee of Correspondence

As leader of the Boston Committee of Correspondence

Dr. Joseph Warren leveraged the mechanics to

collect and report intelligence on the British

And for those readers who have served in government bureaucracies or the military, his remuneration was cut from five schillings per day to four.

The American War for Independence was the culmination of over a decade of political unrest and discontent with British policies and treatment (real and perceived) of the colonists. Although led by some of the brightest minds of the age, or any age, the movement was also a grass roots movement, which gradually built to a political movement – the idea of the ideas bantered around in taverns, coffee houses, homes and farmsteads.

By the early 1770s the movement spurred what was to become an insurgency of sorts. Insurgencies are of their own nature clandestine and they necessitate the development of clandestine activities and the trade-craft (use of spies, secret writing, etc.) necessary for success. As the political side of the patriot movement grew, organizations like “The Sons of Liberty” also sprung up, serving as the action arm.

Boston Ablaze

By the outbreak of rebellion in 1775, the Americans had established organizations necessary to wage the clandestine side of the war as these were already well underway. The British had their counter to this but these activities tended to lag and over time became eclipsed by the Americans’ ability to control the ground in all but those few areas dominated by the British Army and Royal Navy.

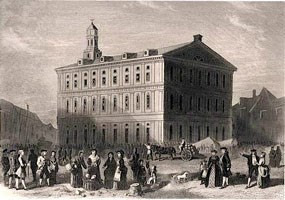

Boston's Fanueil Hall was the site of much

Boston's Fanueil Hall was the site of muchpolitical agitation & intrigue

One of the first clandestine networks established was, of course, in Boston. This was only natural as Boston was the scene of so much political and subversive discourse during the pre- Rev War period. Names like Sam Adams, Paul Revere and John Hancock were legend even then. “Agitprop” became a really effective tool as crowds were whipped up for all sorts of things. In a way, the British missteps in countering all this activity in Boston fueled the flames that eventually burst into a conflagration that scorched the eastern seaboard after April 1775.

Enter the Mechanics

The first patriot intelligence network was a secret group in Boston called the Mechanics. The Mechanics were spawned in Boston from “The Son’s of Liberty" , known famously for their opposition to the Stamp Act and other repressive measures. But the mechanics operated a bit differently. They organized clandestine activities in resistance to British authority. They also gathered intelligence, the lifeblood of the resistance. It began as a group of some thirty “mechanics,” men who worked in hands on trades in and about the city.

Observing counter demonstrators helped

Observing counter demonstrators helpedbuild situational awareness of British sympathizers

Paul Revere was among the first. By his own words they, “…formed ourselves into a Committee for the purpose of watching British soldiers and gaining every intelligence on the movements of the Tories.”

Paul Revere was one of the craftsmen-spies

Paul Revere was one of the craftsmen-spieswho became know as the Mechanics

The key component is the latter. They realized the key to success was neutralizing British sympathizers early on. Revere further stated, “We frequently took turns, two and two, to watch the soldiers by patrolling the streets at night.” Operating under cover of darkness would be a key component of future clandestine activities right up to today. In addition to observing British soldiers and Tories, Revere and the mechanics served as couriers, the essential oil of any clandestine network. Communications is the Achilles heal of clandestine work so the couriers held a special role. The Mechanics played a key role in countering the efforts to suppress the colonial insurgency.

Mechanic Paul Revere alerted General Sullivan of the British intention to seize

Mechanic Paul Revere alerted General Sullivan of the British intention to seizeFort William and Mary

One of Revere’s first missions as a courier took place in December 1774. He rode to the Oyster River in New Hampshire with a report that General Thomas Gage the British commander and governor, planned to take Fort William and Mary. Alerted by the intelligence delivered by the Mechanics, Major John Sullivan led a colonial militia force of four hundred men in a preemptive raid on the fort. They seized one hundred barrels of gunpowder that were ultimately used by the patriots at Bunker Hill

Clandestine Communications

Things really heated up around Boston in early 1775. Both sides became more aggressive and the stakes grew with each month. Through a number of intelligence sources the Mechanics broke the cover established by General Gage for their quick strike on Lexington and Concord. The British counted on secrecy for success. Thanks to the intelligence and warning by the Mechanics, they failed.

The Mechanics' espionage activities

The Mechanics' espionage activitieswere a bane to British General Thomas Gage

Revere received orders from Dr. Joseph Warren, then head of the local Committee of Safety, directing him with warning the key patriot leaders in the region, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, of the British plan to take them in a secret raid on Lexington. Revere arranged for the signal lanterns at the Old North Church. Working with William Dawes, the two rebel leaders were warned. Riders were sent out to alert the militia and then Revere, Dawes and a Dr. Samuel Prescott went on to warn the militias at Concord of the second phase of the operation – seizing the weapons there.

In addition to Revere, Dawes and Prescott, other secret riders

In addition to Revere, Dawes and Prescott, other secret riderswarned the villages of the approaching British

British capture Revere

British capture Revere A British patrol at Lincoln almost ended things before they started. During the chase, Dawes was thrown from his horse while fleeing. But Prescott and Revere were taken prisoner. Prescott soon escaped British capture and made his way to Concord, but Revere remained a prisoner. However, the doughty silversmith, resisted interrogation and was soon released and made his way to Lexington where he and John Lowell were dispatched to retrieve a trunk full of incriminating patriot papers at a local tavern.

A Dearth of Knowledge

In a sense, the dearth of recorded knowledge on the Mechanics is a good thing, not for historians but for the nation. Any records kept, were probably very local and perishable. That is, destroyed on completion of the operation. Operations security came naturally to those seeking survival in a clandestine war. But mistakes are made and can be costly. The trunk Revere was sent to retrieve could have provided the British a trove of intelligence that might have snuffed out the flame of rebellion in New England, and thus ended things.

Mechanic reporting intelligence

Mechanic reporting intelligenceon British activities

A curious example of bureaucratic snafu accidentally preventing failure also involves our celebrated Mechanic, Revere. The mechanics evidently received written orders and some sort of remuneration for their expenses. The orders may have been used to get through militia patrols. For whatever reason, Revere only received his orders from Dr. Warren,leader of the local Committee of Correspondence, two weeks after his clandestine ride. Had he had them with him, his role would have been exposed to the British when they searched him. History again might have taken a distinctly different course.

As leader of the Boston Committee of Correspondence

As leader of the Boston Committee of CorrespondenceDr. Joseph Warren leveraged the mechanics to

collect and report intelligence on the British

And for those readers who have served in government bureaucracies or the military, his remuneration was cut from five schillings per day to four.

Published on November 03, 2019 09:05

September 28, 2019

Tinkerer, Sailor, Soldier, Surgeon

A Connecticut Yankee

So many of our first patriots were accomplished men of letters, lawyers, judges, planters, merchants but relatively few were men of science and technology. David Bushnell falls into the latter category.

Bushnell was born in Saybrook, Connecticut on 30 August 1742, the son of a farmer. He was the first of five children and grew up and worked the family farm near Westbrook. Following the death of his father in 1769, he sold his half interest in the farm to his brother Ezra and entered Yale College in 1771.

David Bushnell

David Bushnell

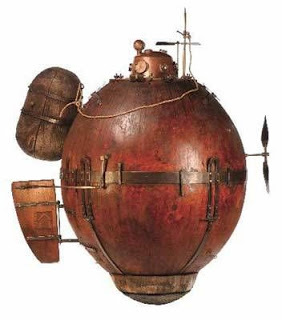

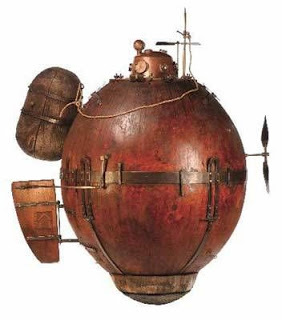

Bombs to Boats

While at Yale he became fascinated by the possibility of underwater explosions. An inventive tinkerer by nature, Bushnell successfully combined a black powder charge with a clockwork timing device, thereby creating the first naval mine. He used this knowledge not only in construction of the underwater mine but later in creating floating torpedoes that exploded on contact. He collaborated with the wealthy New Haven inventor and manufacturer Isaac Doolittle to develop the first mechanically triggered time bomb as well as the first screw propeller. As he set about conceiving a practical delivery system for this unique weapon, the onset of the American War for Independence created a new sense of urgency to his efforts. By the fall of that year he had designed and engineered the American Turtle (better known as Turtle), a primitive submarine. He named it Turtle because it looked like two turtle shells lashed together. Not a thing of beauty, but it worked.

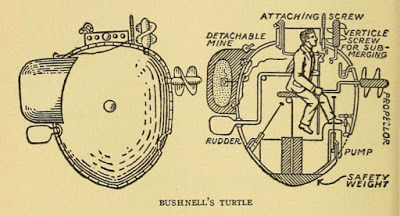

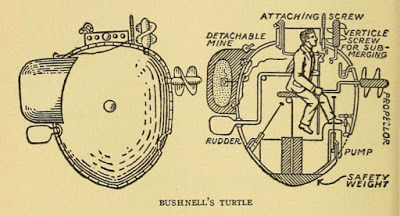

Turtle Design Sketch

Turtle Design Sketch

Test and Evaluation