S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 11

October 14, 2017

Things: Shallow Ford

A Humble Crossing

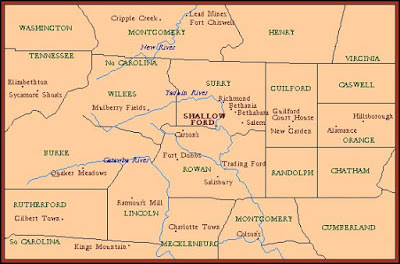

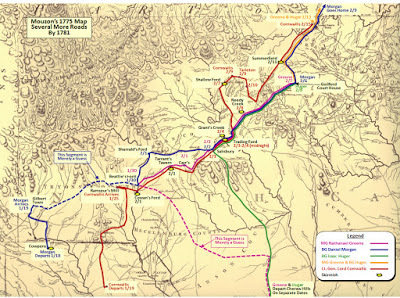

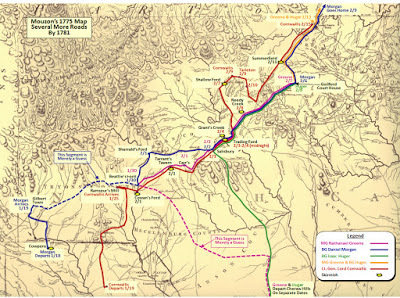

The Shallow Ford, located some 15 miles west of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is,a shallow section of the Yadkin River which, in colonial times, afforded a safe place for travelers to cross. The ford is formed by a sand and gravel bar. Upstream from the ford, a stretch of hard rock crosses the river and below the stretch of rock the gradient decreases, reducing the strength of the current and depositing sediment creating the bar that forms the crossing. It provided a natural game crossing and fish trap, which was used by the Indians. By 1748, six families had settled near the ford. Within two years a ferry and tavern operated there. Soon Moravians settled nearby and cut the first road to the ford and over the years several others were cut, making it a transportation hub of sorts. By the time of the American Revolution, the Shallow Ford was a focal point for travelers. While the Yadkin River could be crossed at other fords and ferries, heavier wagons could cross at only two places: the Trading Ford, near Salisbury (Rowan county), and the Shallow Ford (Surry county). Several roads converged on both sides of the river.That humble crossing would be the instrument of a little heeded but important event in shaping the outcome of the war.

Shallow Ford

Shallow FordA Southern Strategy

Gen Cornwallis

Gen CornwallisThe year 1780 was to be the comeback year for the British in North America with their pivot to a "southern strategy." And a grand and effective strategy it first proved to be. By the fall of 1780, the British commander in the south, General Charles Cornwallis, moved north into North Carolina after subduing most of Georgia and South Carolina. The final phase of the grand strategy of subduing all of the south before moving north into Virginia. He had set up his headquarters in Charlotte where bands of Loyalists rallied to the crown.

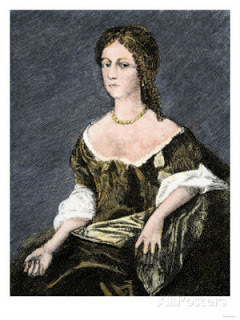

Loyalist Militia gathered with the arrival of Cornwallis

Loyalist Militia gathered with the arrival of CornwallisThe absence of local patriot militia groups who had gone to King's Mountain left a vacuum for Loyalists to rise up and wreak havoc in their prospective counties. In Surry County, local Loyalist brothers Gideon and Hezekiah Wright rallied hundreds of Tories who began exacting revenge on the properties of absent patriots and killing those who opposed them. On October 3rd and 8th, they attacked patriots in Richmond, the county seat, where they killed the county sheriff.

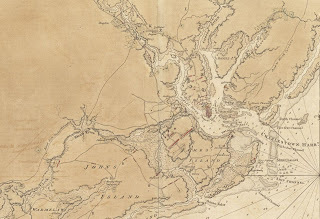

Western NC and Surrey Co in 1780

Western NC and Surrey Co in 1780When news spread of the Loyalist uprising, patriots from nearby areas began to mobilize to stop them. The news of the surprise defeat of the renowned Major Patrick Ferguson at King's Mountain helped electrify the patriots, who had been subdued by Cornwallis's maneuver north. Now things were changing. Patriot militia General William Lee Davidson now believed that the local Tories intended to join Lord Cornwallis' forces in Charlotte. He sent fifty men from Charlotte, along with two companies of patriot militia from Salisbury. They were joined by 160 men from Montgomery County, Virginia, under Major Joseph Cloyd. (who had come to the Carolinas to fight the now dead Ferguson). All of the converging patriots came under the leadership of Cloyd.

A Place of Battle

Competing militias would clash in a small but pivotal battle

Competing militias would clash in a small but pivotal battlealong the Yadkin River at Shallow Ford

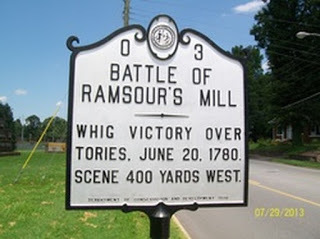

All this activity came to head on 14 October when a band of 600 Loyalists under Colonel Gideon Wright crossed the Yadkin River on their way to join General Cornwallis in Charlotte. On Saturday morning, 14 October, Cloyd's force of 350 men waited on the west side of a small stream near the Shallow Ford crossing of the Yadkin River. About 9:30 they spotted the Loyalist force that terrorized the county for the past weeks. The force numbering between 400 and 900 crossed the Yadkin and were moving westward on the Mulberry Fields Road. A cry of "Tory! Tory!" went out among the patriots. From across the creek they heard similar cries of "Rebel! Rebel!"

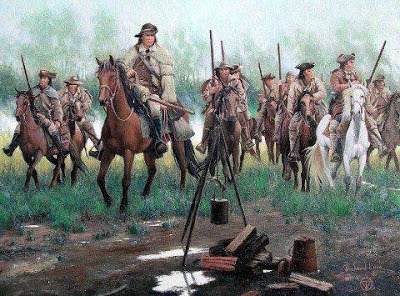

NC patriot militia

NC patriot militiaThe patriots deployed and battle lines soon formed. Volleys were exchanged. One Captain James Bryan, of the notorious Tory Bryan clan, who led the advance element of Loyalist forces, was quickly killed. Five rifle balls passed through him and his horse. The patriots advanced towards the ford as the Loyalists fell back and formed again. Captain Henry Francis of the Virginia militia was shot through the head and fell dead on the ground a few steps from his son, Henry. His other son, John, took careful aim and fired at the Loyalist who had killed his father. Though outnumbered, the patriots soon had the advantage and several more Loyalists fell. After another quick exchange of fire, the Loyalists retreated in disorder across the Yadkin, shouting "we are whipped, we are whipped." Enraged patriots beat the wounded Loyalists to death after their comrades had fled. A black Loyalist named Ball Turner continued to fire at the patriots. An angry party of patriots found his location and riddled him with musket balls. The Loyalists soon made good their escape. Captain Henry Francis of the Whigs lost his life, and four others were wounded. The Loyalists lost some fifteen killed. The engagement took less than an hour.

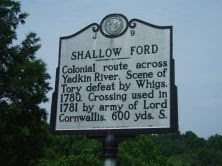

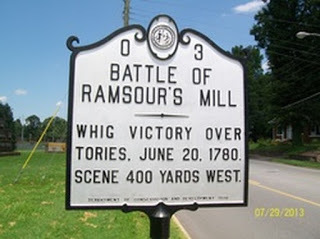

Shallow Ford Battle Marker

Shallow Ford Battle MarkerAftermath

As the engagement ended, a relief party of three hundred militia under Colonel John Peasley arrived, along with Colonel Joseph Williams of Surrey county. Williams had heard the musket fire from his nearby home. The next day, Major General William Smallwood arrived at Salem with about 150 horsemen, thirty infantry, and three wagons. Smallwood, a Marylander, had been put in command of all North Carolina militia. As a colonel in 1776, Smallwood had commanded the famed Maryland Line on Long Island and is featured in my novel of that campaign, The Patriot Spy. Smallwood had left Guilford Courthouse the previous day. Seeing the local force had defeated the Loyalists, he launched his men in pursuit of those who had fled. As a result of Shallow Ford, the Wright brothers' Loyalist forces in Surry County were essentially nullified for the duration of the war. Hezekiah Wright himself was later shot and wounded in his own home. His brother Gideon fled to the safety of Charlestown, where he died on August 9, 1782.

General William Smallwood

General William SmallwoodThe results of the double defeats at King's Mountain and Shallow Ford were a major blow to Cornwallis: patriot morale increased dramatically along with their numbers, while demoralized North Carolina Loyalists were never able to gather such a force again. Cornwallis had to withdraw into South Carolina for the winter. His grand strategy was set back by a year, with even graver implications for any hope of a British victory.

Fittingly, the Shallow Ford played a minor role the following year when on 7 & 8 February Cornwallis's army crossed it in the legendary pursuit of General Nathanael Greene in the maneuvers that led to the Battle of Guilford Court House on 15 March, 1781.

Published on October 14, 2017 10:16

September 16, 2017

Places: Blackstock

A Savage War of Posts

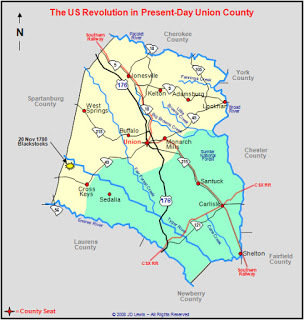

Gen Thomas SumterThe William Blackstock farm became the site of one of those "small" but violent clashes that made up the complex mosaic of the American Revolution in the South. The farm (several tobacco barns) sits just off the Tyger River, at the western edge of Union County, South Carolina. This backwater farm formed the backdrop to one of American General Thomas Sumter's most important battles. In November 1780, Georgia militia under Elijah Clark and John Twiggs reinforced Sumter, whose forces threatened Loyalist outposts north of the famed bastion at Ninety-Six. Sensing a threat to Ninety-Six could become untenable, the British commander in the south, Lord Cornwallis, ordered famed cavalry commander, Banastre Tarleton to break off contact with Francis (Swamp Fox) Marion's militia along the Pee Dee River. Tarleton rushed to his new assignment hoping to pin Sumter's force between him and the British at Ninety-Six. Fortunately, a British deserter gave warning to Sumter, who beat a hasty retreat out of the impending trap. Not to be outdone, the ever aggressive Tarleton pursued hell bent to get the rebel force before it could elude him. To do this, he led his cavalry, leaving infantry and guns to follow.

Gen Thomas SumterThe William Blackstock farm became the site of one of those "small" but violent clashes that made up the complex mosaic of the American Revolution in the South. The farm (several tobacco barns) sits just off the Tyger River, at the western edge of Union County, South Carolina. This backwater farm formed the backdrop to one of American General Thomas Sumter's most important battles. In November 1780, Georgia militia under Elijah Clark and John Twiggs reinforced Sumter, whose forces threatened Loyalist outposts north of the famed bastion at Ninety-Six. Sensing a threat to Ninety-Six could become untenable, the British commander in the south, Lord Cornwallis, ordered famed cavalry commander, Banastre Tarleton to break off contact with Francis (Swamp Fox) Marion's militia along the Pee Dee River. Tarleton rushed to his new assignment hoping to pin Sumter's force between him and the British at Ninety-Six. Fortunately, a British deserter gave warning to Sumter, who beat a hasty retreat out of the impending trap. Not to be outdone, the ever aggressive Tarleton pursued hell bent to get the rebel force before it could elude him. To do this, he led his cavalry, leaving infantry and guns to follow.

A Defense Well Prepared

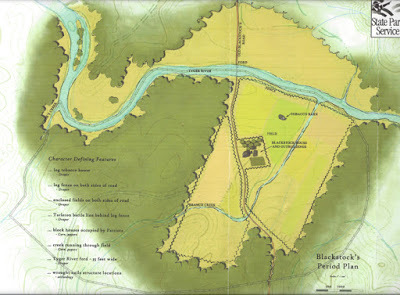

Elijah ClarkeSumter's force reached the Tyger River at dusk on the 20th of November. The canny Sumter realized he had "good ground" and decided to establish defensive positions and frustrate his pursuers with a stout defense of the farm. The famed "Gamecock" distributed his 1,000 men in defensive positions. They did not have long to wait before Tarleton's Legion - 190 dragoons and 80 mounted infantry of

Elijah ClarkeSumter's force reached the Tyger River at dusk on the 20th of November. The canny Sumter realized he had "good ground" and decided to establish defensive positions and frustrate his pursuers with a stout defense of the farm. The famed "Gamecock" distributed his 1,000 men in defensive positions. They did not have long to wait before Tarleton's Legion - 190 dragoons and 80 mounted infantry of

the British 63rd Regiment were observed moving at them. Realizing the rest of Tarleton's force was far behind, Sumter decided to surprise the lead forces with an attack. Sumter left his center to defend the high ground using protection of the five log cabins and a rail fence. He sent Elijah Clark with his 80 Georgians around the advancing Tarleton's right flank to block the British troops coming up. Sumter led the main thrust with 400 militia against 80 regulars of the 63rd who had dismounted and taken up positions to the right of the British advance.

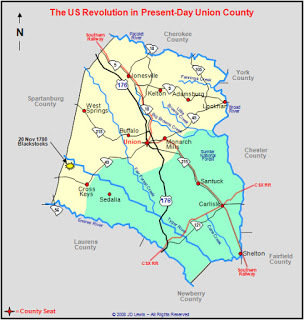

Sketch of the battlefield

Sketch of the battlefield

A Back and Forth Struggle

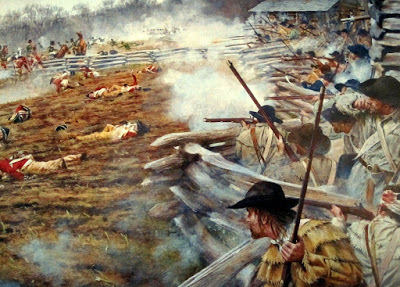

Banastre TarletonSumter's plans turned to dust when the British 63rd repulsed his militia who retreated back through the houses anchoring the center. Not to be undone, Sumter dispatched a force of mounted infantry under Colonel Lacey with orders to strike the British dragoons on the left. Lacey's men surprised the dragoons (who were admiring the work of the 63rd). Lacey's first volley inflicted 20 casualties on the troopers. But they quickly recovered and drove off Lacey's men. Itching to dispatch the rebels, the 80 men of the 63rd attacked the center. A bayonet charge led by Major John Money sought to drive back the rebels but the 63d advanced too close to the farm buildings and came under fire from Colonel Henry Hampton's men inside, as usual aiming "at the epaulets and stripes." Money and two of his lieutenants were killed, and according to an officer of Fraser's Highlanders, a third of the privates as well. Meanwhile, other partisans worked their way around their right flank and attacked Tarleton's dragoons who were in their saddles but only watching the action. Now that Hampton's South Carolina riflemen and some of the Georgia sharpshooters held the line and checked the British, Sumter's men began to rally around them. The British infantry were trapped under the muskets and rifles of an enraged patriot force. Seeing their distress, Tarleton led a desperate charge at the American center. The reckless uphill cavalry charge against riflemen firing from cover did not go well. One report recorded so many dragoons knocked from their horses that the road to the ford was blocked by the bodies of men and fallen chargers, the wounded, still targets, struggling back over their stricken comrades and kicking, screaming horses. Still, the British forces fell back in good order.

Banastre TarletonSumter's plans turned to dust when the British 63rd repulsed his militia who retreated back through the houses anchoring the center. Not to be undone, Sumter dispatched a force of mounted infantry under Colonel Lacey with orders to strike the British dragoons on the left. Lacey's men surprised the dragoons (who were admiring the work of the 63rd). Lacey's first volley inflicted 20 casualties on the troopers. But they quickly recovered and drove off Lacey's men. Itching to dispatch the rebels, the 80 men of the 63rd attacked the center. A bayonet charge led by Major John Money sought to drive back the rebels but the 63d advanced too close to the farm buildings and came under fire from Colonel Henry Hampton's men inside, as usual aiming "at the epaulets and stripes." Money and two of his lieutenants were killed, and according to an officer of Fraser's Highlanders, a third of the privates as well. Meanwhile, other partisans worked their way around their right flank and attacked Tarleton's dragoons who were in their saddles but only watching the action. Now that Hampton's South Carolina riflemen and some of the Georgia sharpshooters held the line and checked the British, Sumter's men began to rally around them. The British infantry were trapped under the muskets and rifles of an enraged patriot force. Seeing their distress, Tarleton led a desperate charge at the American center. The reckless uphill cavalry charge against riflemen firing from cover did not go well. One report recorded so many dragoons knocked from their horses that the road to the ford was blocked by the bodies of men and fallen chargers, the wounded, still targets, struggling back over their stricken comrades and kicking, screaming horses. Still, the British forces fell back in good order.

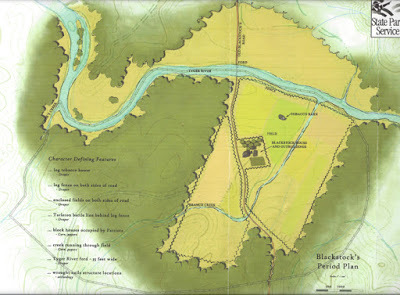

Tarleton's cavalry attack repulsed by intense American fire

Tarleton's cavalry attack repulsed by intense American fire

Change of Command

John TwiggsNot without his own bravado, Sumter rode to the center of his line as the British dragoons were repulsed. As they made their withdrawal, members of the 63d fired a volley at him and his officers. Sumter was severely wounded, taking rounds in the arm and the back, and had to relinquish command to John Twiggs. Realizing he would have no more success that day, Tarleton pulled back and awaited reinforcements hoping to launch another attack the next day. Fearing that troops from Ninety-Six would join with Tarleton to overwhelm them, the Americans retreated. To deceive the British scouts, Twiggs left camp fires burning and withdrew under the cover of night. Tarleton claimed the battlefield, and the battle, the following day. But can sense his frustration as he was forced to bury the dead of both sides. The butcher's bill was lopsided: British casualties: 92 killed and 75-100 wounded.American casualties: 3 killed, 4 wounded, and 50 captured.

John TwiggsNot without his own bravado, Sumter rode to the center of his line as the British dragoons were repulsed. As they made their withdrawal, members of the 63d fired a volley at him and his officers. Sumter was severely wounded, taking rounds in the arm and the back, and had to relinquish command to John Twiggs. Realizing he would have no more success that day, Tarleton pulled back and awaited reinforcements hoping to launch another attack the next day. Fearing that troops from Ninety-Six would join with Tarleton to overwhelm them, the Americans retreated. To deceive the British scouts, Twiggs left camp fires burning and withdrew under the cover of night. Tarleton claimed the battlefield, and the battle, the following day. But can sense his frustration as he was forced to bury the dead of both sides. The butcher's bill was lopsided: British casualties: 92 killed and 75-100 wounded.American casualties: 3 killed, 4 wounded, and 50 captured.

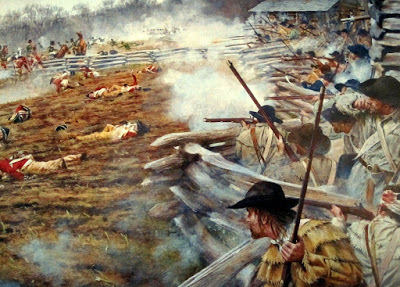

View of American defenses

View of American defenses

After the Battle

The engagement at the Blackstock farm is little known, and for many years nearly forgotten. Tarleton boasted of his victory and the dispatching of the hated Sumter. Yet his regulars had failed to eject the rebel militia from the field and had suffered an unacceptable loss ratio. Moreover, Sumter would be back in action in a few months. Meanwhile, his wounding enabled General George Washington to appoint the New England fighting quaker Nathanael Greene as overall commander of the Southern Department.

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene

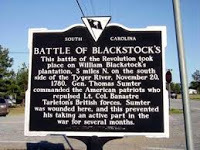

The Battlefield Today

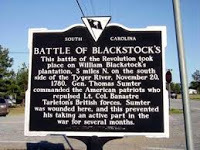

The Blackstock Plantation, once a series of tobacco barns, lies in in a hilly, wooded region. In the eighteenth century much of the land of the battlefield was cleared, but has since overgrown with

The Blackstock Plantation, once a series of tobacco barns, lies in in a hilly, wooded region. In the eighteenth century much of the land of the battlefield was cleared, but has since overgrown with

small pines and brush. No above-the-surface evidence remains of Blackstock’s barn or house, which were located in the area of the historical marker that designates the battle site, and there are no modern buildings in the area of the battlefield. The site has 54 acres preserved with walking trails just south of the Tyger River.

Gen Thomas SumterThe William Blackstock farm became the site of one of those "small" but violent clashes that made up the complex mosaic of the American Revolution in the South. The farm (several tobacco barns) sits just off the Tyger River, at the western edge of Union County, South Carolina. This backwater farm formed the backdrop to one of American General Thomas Sumter's most important battles. In November 1780, Georgia militia under Elijah Clark and John Twiggs reinforced Sumter, whose forces threatened Loyalist outposts north of the famed bastion at Ninety-Six. Sensing a threat to Ninety-Six could become untenable, the British commander in the south, Lord Cornwallis, ordered famed cavalry commander, Banastre Tarleton to break off contact with Francis (Swamp Fox) Marion's militia along the Pee Dee River. Tarleton rushed to his new assignment hoping to pin Sumter's force between him and the British at Ninety-Six. Fortunately, a British deserter gave warning to Sumter, who beat a hasty retreat out of the impending trap. Not to be outdone, the ever aggressive Tarleton pursued hell bent to get the rebel force before it could elude him. To do this, he led his cavalry, leaving infantry and guns to follow.

Gen Thomas SumterThe William Blackstock farm became the site of one of those "small" but violent clashes that made up the complex mosaic of the American Revolution in the South. The farm (several tobacco barns) sits just off the Tyger River, at the western edge of Union County, South Carolina. This backwater farm formed the backdrop to one of American General Thomas Sumter's most important battles. In November 1780, Georgia militia under Elijah Clark and John Twiggs reinforced Sumter, whose forces threatened Loyalist outposts north of the famed bastion at Ninety-Six. Sensing a threat to Ninety-Six could become untenable, the British commander in the south, Lord Cornwallis, ordered famed cavalry commander, Banastre Tarleton to break off contact with Francis (Swamp Fox) Marion's militia along the Pee Dee River. Tarleton rushed to his new assignment hoping to pin Sumter's force between him and the British at Ninety-Six. Fortunately, a British deserter gave warning to Sumter, who beat a hasty retreat out of the impending trap. Not to be outdone, the ever aggressive Tarleton pursued hell bent to get the rebel force before it could elude him. To do this, he led his cavalry, leaving infantry and guns to follow.

A Defense Well Prepared

Elijah ClarkeSumter's force reached the Tyger River at dusk on the 20th of November. The canny Sumter realized he had "good ground" and decided to establish defensive positions and frustrate his pursuers with a stout defense of the farm. The famed "Gamecock" distributed his 1,000 men in defensive positions. They did not have long to wait before Tarleton's Legion - 190 dragoons and 80 mounted infantry of

Elijah ClarkeSumter's force reached the Tyger River at dusk on the 20th of November. The canny Sumter realized he had "good ground" and decided to establish defensive positions and frustrate his pursuers with a stout defense of the farm. The famed "Gamecock" distributed his 1,000 men in defensive positions. They did not have long to wait before Tarleton's Legion - 190 dragoons and 80 mounted infantry of the British 63rd Regiment were observed moving at them. Realizing the rest of Tarleton's force was far behind, Sumter decided to surprise the lead forces with an attack. Sumter left his center to defend the high ground using protection of the five log cabins and a rail fence. He sent Elijah Clark with his 80 Georgians around the advancing Tarleton's right flank to block the British troops coming up. Sumter led the main thrust with 400 militia against 80 regulars of the 63rd who had dismounted and taken up positions to the right of the British advance.

Sketch of the battlefield

Sketch of the battlefieldA Back and Forth Struggle

Banastre TarletonSumter's plans turned to dust when the British 63rd repulsed his militia who retreated back through the houses anchoring the center. Not to be undone, Sumter dispatched a force of mounted infantry under Colonel Lacey with orders to strike the British dragoons on the left. Lacey's men surprised the dragoons (who were admiring the work of the 63rd). Lacey's first volley inflicted 20 casualties on the troopers. But they quickly recovered and drove off Lacey's men. Itching to dispatch the rebels, the 80 men of the 63rd attacked the center. A bayonet charge led by Major John Money sought to drive back the rebels but the 63d advanced too close to the farm buildings and came under fire from Colonel Henry Hampton's men inside, as usual aiming "at the epaulets and stripes." Money and two of his lieutenants were killed, and according to an officer of Fraser's Highlanders, a third of the privates as well. Meanwhile, other partisans worked their way around their right flank and attacked Tarleton's dragoons who were in their saddles but only watching the action. Now that Hampton's South Carolina riflemen and some of the Georgia sharpshooters held the line and checked the British, Sumter's men began to rally around them. The British infantry were trapped under the muskets and rifles of an enraged patriot force. Seeing their distress, Tarleton led a desperate charge at the American center. The reckless uphill cavalry charge against riflemen firing from cover did not go well. One report recorded so many dragoons knocked from their horses that the road to the ford was blocked by the bodies of men and fallen chargers, the wounded, still targets, struggling back over their stricken comrades and kicking, screaming horses. Still, the British forces fell back in good order.

Banastre TarletonSumter's plans turned to dust when the British 63rd repulsed his militia who retreated back through the houses anchoring the center. Not to be undone, Sumter dispatched a force of mounted infantry under Colonel Lacey with orders to strike the British dragoons on the left. Lacey's men surprised the dragoons (who were admiring the work of the 63rd). Lacey's first volley inflicted 20 casualties on the troopers. But they quickly recovered and drove off Lacey's men. Itching to dispatch the rebels, the 80 men of the 63rd attacked the center. A bayonet charge led by Major John Money sought to drive back the rebels but the 63d advanced too close to the farm buildings and came under fire from Colonel Henry Hampton's men inside, as usual aiming "at the epaulets and stripes." Money and two of his lieutenants were killed, and according to an officer of Fraser's Highlanders, a third of the privates as well. Meanwhile, other partisans worked their way around their right flank and attacked Tarleton's dragoons who were in their saddles but only watching the action. Now that Hampton's South Carolina riflemen and some of the Georgia sharpshooters held the line and checked the British, Sumter's men began to rally around them. The British infantry were trapped under the muskets and rifles of an enraged patriot force. Seeing their distress, Tarleton led a desperate charge at the American center. The reckless uphill cavalry charge against riflemen firing from cover did not go well. One report recorded so many dragoons knocked from their horses that the road to the ford was blocked by the bodies of men and fallen chargers, the wounded, still targets, struggling back over their stricken comrades and kicking, screaming horses. Still, the British forces fell back in good order. Tarleton's cavalry attack repulsed by intense American fire

Tarleton's cavalry attack repulsed by intense American fireChange of Command

John TwiggsNot without his own bravado, Sumter rode to the center of his line as the British dragoons were repulsed. As they made their withdrawal, members of the 63d fired a volley at him and his officers. Sumter was severely wounded, taking rounds in the arm and the back, and had to relinquish command to John Twiggs. Realizing he would have no more success that day, Tarleton pulled back and awaited reinforcements hoping to launch another attack the next day. Fearing that troops from Ninety-Six would join with Tarleton to overwhelm them, the Americans retreated. To deceive the British scouts, Twiggs left camp fires burning and withdrew under the cover of night. Tarleton claimed the battlefield, and the battle, the following day. But can sense his frustration as he was forced to bury the dead of both sides. The butcher's bill was lopsided: British casualties: 92 killed and 75-100 wounded.American casualties: 3 killed, 4 wounded, and 50 captured.

John TwiggsNot without his own bravado, Sumter rode to the center of his line as the British dragoons were repulsed. As they made their withdrawal, members of the 63d fired a volley at him and his officers. Sumter was severely wounded, taking rounds in the arm and the back, and had to relinquish command to John Twiggs. Realizing he would have no more success that day, Tarleton pulled back and awaited reinforcements hoping to launch another attack the next day. Fearing that troops from Ninety-Six would join with Tarleton to overwhelm them, the Americans retreated. To deceive the British scouts, Twiggs left camp fires burning and withdrew under the cover of night. Tarleton claimed the battlefield, and the battle, the following day. But can sense his frustration as he was forced to bury the dead of both sides. The butcher's bill was lopsided: British casualties: 92 killed and 75-100 wounded.American casualties: 3 killed, 4 wounded, and 50 captured. View of American defenses

View of American defensesAfter the Battle

The engagement at the Blackstock farm is little known, and for many years nearly forgotten. Tarleton boasted of his victory and the dispatching of the hated Sumter. Yet his regulars had failed to eject the rebel militia from the field and had suffered an unacceptable loss ratio. Moreover, Sumter would be back in action in a few months. Meanwhile, his wounding enabled General George Washington to appoint the New England fighting quaker Nathanael Greene as overall commander of the Southern Department.

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael GreeneThe Battlefield Today

The Blackstock Plantation, once a series of tobacco barns, lies in in a hilly, wooded region. In the eighteenth century much of the land of the battlefield was cleared, but has since overgrown with

The Blackstock Plantation, once a series of tobacco barns, lies in in a hilly, wooded region. In the eighteenth century much of the land of the battlefield was cleared, but has since overgrown with small pines and brush. No above-the-surface evidence remains of Blackstock’s barn or house, which were located in the area of the historical marker that designates the battle site, and there are no modern buildings in the area of the battlefield. The site has 54 acres preserved with walking trails just south of the Tyger River.

Published on September 16, 2017 11:41

August 13, 2017

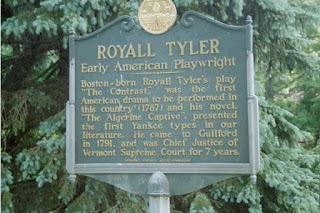

People: The Patriot Playwright

An American First

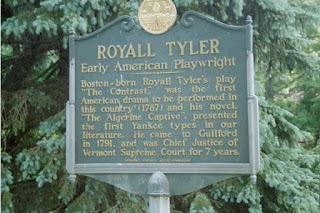

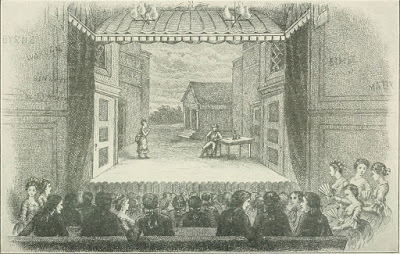

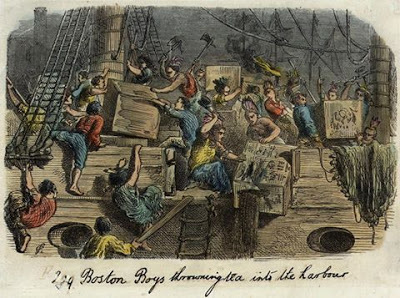

On 16 April 1787 "the first American play" opened at the John Street Theater in New York City. Entitled, The Contrast, it was written by 29-year-old Royall Tyler. It is considered the first American play ever performed in public by a company of professional actors. An American play in the sense it was written by an American, with an American theme, for American audiences.

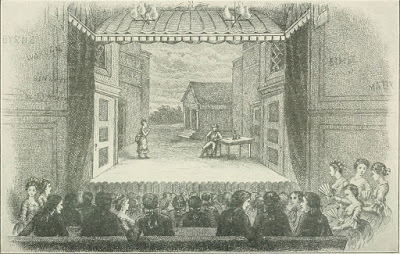

John Street Theater - Birthplace of American Theater would close in 1798

John Street Theater - Birthplace of American Theater would close in 1798

A Playwright Patriot

Royall Tyler was born in Boston on 18 July, 1758. He had a great pedigree, coming from one of the wealthiest and most prominent families in Massachusetts. Tyler received his early education at

the Latin School, in Boston. He then went on to Harvard where he read the law. Along the way he joined the Continental Army where he received a commission and eventually rose to the rank of major. Tyler was admitted to the bar in 1780, and joined the law office of John Adams. Tyler fell in love with the future president's daughter; but the engagement was broken off, reportedly because Adams disapproved of Tyler's "high-spirited temperament." With John's attitude that might have ruled out a whole generation of potential beaus.

General Benjamin Lincoln

General Benjamin Lincoln

Back to the Bar. back to the Army and on to the Theater

The end of the war and the birth of the republic in 1783 did not go long before America had its first crisis. In 1786, Shay's Rebellion broke out in New England. Many veterans felt (rightfully) that the new republic did not pay enough attention to their economic woes and that years of service were held in little regard. A former Massachusetts soldier and down and out farmer, Daniel Shays led a band of disgruntled veterans seeking redress of their grievances. The reaction came quickly as a panicked government put together forces to quell the rebels. In 1787 Tyler once more answered his nation's call. He left the practice of law to take an appointment as the aide de camp to General Benjamin Lincoln, charged with suppressing Daniel Shays and his rebellious ex-soldiers. After Shays left Massachusetts (the heart of the rebellion) for New York, Tyler was sent to New York City to negotiate his capture and return to Massachusetts. And while there, as millions have done over the years,Tyler did something that he had never done - he went to see a play!

Shays Rebellion would set events leading to

Shays Rebellion would set events leading to

the birth of the American stage

That's Entertainment

Theater was slow to take off in America as a popular form of entertainment. There are known performances of Shakespeare in Williamsburg in the early 1700s, and in general the Southern colonies — which were more open to all British customs — were happier to embrace the theater. In the North, it was looked on as a sinful form of entertainment. Massachusetts actually passed a law in 1750 that outlawed theater performances, and by 1760 there were similar laws in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, although performances occasionally snuck through the laws with the special permission of authorities.

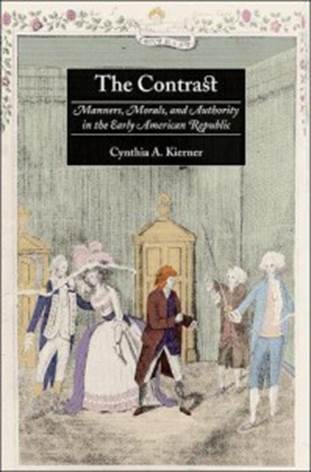

Reprint with comment by modern historian Cynthia Kierner

Reprint with comment by modern historian Cynthia Kierner

illustrates the enduring value of The Contrast as a vehicle

for understanding mores of post Revolutionary America.

A Playwright is Born

In any case, Royall Tyler had never been to the theater before. So on March 12, 1787, he went to see a production of Richard Sheridan's School for Scandal (1777). He was so inspired that in just three weeks he wrote his own play, The Contrast. Barely a month later, The Contrast became the first play by an American writer to be professionally produced. The Contrast was a comedy of manners, poking fun at Americans with European pretensions, and the main character, Jonathan, was the first "Yankee" stock character, a backwoods man who spoke in a distinctive American voice and mannerisms. Mixing such a character with sophisticates is a technique writers use to this day - the traditional "fish out of water." Tyler did not pioneer this. But he did master it. And the results were compelling to late 18th century audiences. The Contrast was a success. It was performed four times that month in New York, which was very unusual. Then it moved on to Baltimore and Philadelphia, where George Washington went to see it. The first citizen's approbation added to the buzz both for the play and the stage in general.

Man of Letters

Tyler went on to be one of the most accomplished men of letters in early America. While he continued to practice law, he wrote six other plays. Only four exist today, three are biblical plays and the fourth another social satire, The Island of Barrataria. Also also produced a number of verse and prose works, including a colorful adventure novel, The Algerine Captive (1797). The plot is the memoir of a young man who has a series of misadventures eventually leading to enslavement by barbary pirates. In addition to being a bit of Americana it ends with a serious call for Americans to unite. The book had more than one printing and is only the second American work to be printed in Britain.

Royall Tyler: jurist and author in late life

Royall Tyler: jurist and author in late life

Author & Attorney

Tyler's literary works were published anonymously. After all, the arts were still considered something beneath the mainstream and he was a serious jurist with a reputation to maintain. His works brought little income. He clearly produced them out of a labor of love. Many modern authors, including this one, can relate to the situation! As a member of the legal profession, he sought to correct those ills and follies which he satirized in his writing. He died in Brattleboro, Vt.

The Seed of Modern Theater Long Forgotten

The success of The Contrast brought contemporary drama and theatrical productions into high favor among all classes. Over a short period of time they went from mild disdain to high regard and sometimes wild popularity. In that sense the "arts" owe him a great deal. Certainly modern stage does. Yet I am sure few in the business know of Royall Tyler the patriot and playwright who birthed their art form. Methinks a new rebellion need take place. A Royall rebellion in fact. Perhaps the "Tony" should be renamed the "Tyler?"

So should Tony become Tyler?

So should Tony become Tyler?

On 16 April 1787 "the first American play" opened at the John Street Theater in New York City. Entitled, The Contrast, it was written by 29-year-old Royall Tyler. It is considered the first American play ever performed in public by a company of professional actors. An American play in the sense it was written by an American, with an American theme, for American audiences.

John Street Theater - Birthplace of American Theater would close in 1798

John Street Theater - Birthplace of American Theater would close in 1798A Playwright Patriot

Royall Tyler was born in Boston on 18 July, 1758. He had a great pedigree, coming from one of the wealthiest and most prominent families in Massachusetts. Tyler received his early education at

the Latin School, in Boston. He then went on to Harvard where he read the law. Along the way he joined the Continental Army where he received a commission and eventually rose to the rank of major. Tyler was admitted to the bar in 1780, and joined the law office of John Adams. Tyler fell in love with the future president's daughter; but the engagement was broken off, reportedly because Adams disapproved of Tyler's "high-spirited temperament." With John's attitude that might have ruled out a whole generation of potential beaus.

General Benjamin Lincoln

General Benjamin LincolnBack to the Bar. back to the Army and on to the Theater

The end of the war and the birth of the republic in 1783 did not go long before America had its first crisis. In 1786, Shay's Rebellion broke out in New England. Many veterans felt (rightfully) that the new republic did not pay enough attention to their economic woes and that years of service were held in little regard. A former Massachusetts soldier and down and out farmer, Daniel Shays led a band of disgruntled veterans seeking redress of their grievances. The reaction came quickly as a panicked government put together forces to quell the rebels. In 1787 Tyler once more answered his nation's call. He left the practice of law to take an appointment as the aide de camp to General Benjamin Lincoln, charged with suppressing Daniel Shays and his rebellious ex-soldiers. After Shays left Massachusetts (the heart of the rebellion) for New York, Tyler was sent to New York City to negotiate his capture and return to Massachusetts. And while there, as millions have done over the years,Tyler did something that he had never done - he went to see a play!

Shays Rebellion would set events leading to

Shays Rebellion would set events leading tothe birth of the American stage

That's Entertainment

Theater was slow to take off in America as a popular form of entertainment. There are known performances of Shakespeare in Williamsburg in the early 1700s, and in general the Southern colonies — which were more open to all British customs — were happier to embrace the theater. In the North, it was looked on as a sinful form of entertainment. Massachusetts actually passed a law in 1750 that outlawed theater performances, and by 1760 there were similar laws in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire, although performances occasionally snuck through the laws with the special permission of authorities.

Reprint with comment by modern historian Cynthia Kierner

Reprint with comment by modern historian Cynthia Kiernerillustrates the enduring value of The Contrast as a vehicle

for understanding mores of post Revolutionary America.

A Playwright is Born

In any case, Royall Tyler had never been to the theater before. So on March 12, 1787, he went to see a production of Richard Sheridan's School for Scandal (1777). He was so inspired that in just three weeks he wrote his own play, The Contrast. Barely a month later, The Contrast became the first play by an American writer to be professionally produced. The Contrast was a comedy of manners, poking fun at Americans with European pretensions, and the main character, Jonathan, was the first "Yankee" stock character, a backwoods man who spoke in a distinctive American voice and mannerisms. Mixing such a character with sophisticates is a technique writers use to this day - the traditional "fish out of water." Tyler did not pioneer this. But he did master it. And the results were compelling to late 18th century audiences. The Contrast was a success. It was performed four times that month in New York, which was very unusual. Then it moved on to Baltimore and Philadelphia, where George Washington went to see it. The first citizen's approbation added to the buzz both for the play and the stage in general.

Man of Letters

Tyler went on to be one of the most accomplished men of letters in early America. While he continued to practice law, he wrote six other plays. Only four exist today, three are biblical plays and the fourth another social satire, The Island of Barrataria. Also also produced a number of verse and prose works, including a colorful adventure novel, The Algerine Captive (1797). The plot is the memoir of a young man who has a series of misadventures eventually leading to enslavement by barbary pirates. In addition to being a bit of Americana it ends with a serious call for Americans to unite. The book had more than one printing and is only the second American work to be printed in Britain.

Royall Tyler: jurist and author in late life

Royall Tyler: jurist and author in late lifeAuthor & Attorney

Tyler's literary works were published anonymously. After all, the arts were still considered something beneath the mainstream and he was a serious jurist with a reputation to maintain. His works brought little income. He clearly produced them out of a labor of love. Many modern authors, including this one, can relate to the situation! As a member of the legal profession, he sought to correct those ills and follies which he satirized in his writing. He died in Brattleboro, Vt.

The Seed of Modern Theater Long Forgotten

The success of The Contrast brought contemporary drama and theatrical productions into high favor among all classes. Over a short period of time they went from mild disdain to high regard and sometimes wild popularity. In that sense the "arts" owe him a great deal. Certainly modern stage does. Yet I am sure few in the business know of Royall Tyler the patriot and playwright who birthed their art form. Methinks a new rebellion need take place. A Royall rebellion in fact. Perhaps the "Tony" should be renamed the "Tyler?"

So should Tony become Tyler?

So should Tony become Tyler?

Published on August 13, 2017 16:46

July 9, 2017

Things: The Road of Destruction

A Prequel

This is a rare Yankee Doodle Spies "prequel" post. In many ways the seeds of the American struggle for independence were watered with the blood of the French and Indian War. And in a bold coincidence George Washington's activities in the western (Virginia- Pennsylvania-Ohio) frontier played a role in its beginning. A young Washington had explored the frontier for the then Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. During one mission, an altercation with a party of French and Indians spurred both nations (and much of Europe) into a long and costly war. As one of the few English who had traversed the wilderness,Washington was appointed a special aide to the commander in chief of British forces in North America, Edward Braddock. Washington did not have a Royal commission, however, and was considered a colonial officer. This was no small factor in Washington's later drift from being English to being American.

Washington became a special assistant

Washington became a special assistant

due to his experience in the west

The Campaign

Gen BraddockBecause the war began over a dispute about the western limits of British North America, Britain's first objective was to secure the French forts near the Ohio River. In the summer of 1755, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock, decided to personally lead the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. He had two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th (about 1,350 men), plus some 500 colonial troops and militiamen. To take the forts he brought some artillery and other support troops (engineers, artificers, etc.). Braddock, a confident if not arrogant Scotsman, was confident he could seize Fort Duquesne (today's Pittsburgh) with little difficulty. He would then move north to capture the other French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. Two other campaigns would push directly north into French Quebec but this was to be the main effort.

Gen BraddockBecause the war began over a dispute about the western limits of British North America, Britain's first objective was to secure the French forts near the Ohio River. In the summer of 1755, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock, decided to personally lead the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. He had two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th (about 1,350 men), plus some 500 colonial troops and militiamen. To take the forts he brought some artillery and other support troops (engineers, artificers, etc.). Braddock, a confident if not arrogant Scotsman, was confident he could seize Fort Duquesne (today's Pittsburgh) with little difficulty. He would then move north to capture the other French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. Two other campaigns would push directly north into French Quebec but this was to be the main effort.

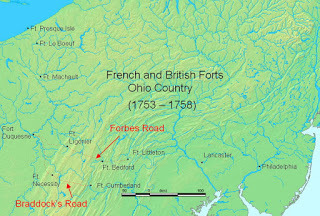

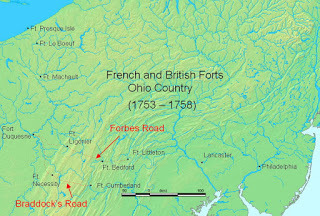

The Western Theater of Operations

The Western Theater of Operations

The Road to Victory

Sketch of Braddock's RouteThere is some controversy as to which direction the British should take. There were two main routes to the west. One to the south traversed Virginia (West Virginia today) while the other went through western Pennsylvania. Washington was connected to the commercial interests that supported using the southern route. The rationale for both parties being that British military improvements to the road chosen would ensure that route became the main British artery to the west. In either case, Braddock chose the southern route, which ran through much more rugged and densely wooded terrain. The march to Fort Duquesne relied on the building of a road that Braddock and his men constructed by using an old Indian path called Nemacolin’s Path, which gave them a route through the Allegheny Mountains. Braddock's troops marched from Alexandria to Winchester to Cumberland (MD), where the road through the wilderness began. It took them a little over a month to build this road, which was 12 feet wide and 110 miles long and 50 years later, financed by Congress as the first National Road. But it never took them to Fort Dusquesne.

Sketch of Braddock's RouteThere is some controversy as to which direction the British should take. There were two main routes to the west. One to the south traversed Virginia (West Virginia today) while the other went through western Pennsylvania. Washington was connected to the commercial interests that supported using the southern route. The rationale for both parties being that British military improvements to the road chosen would ensure that route became the main British artery to the west. In either case, Braddock chose the southern route, which ran through much more rugged and densely wooded terrain. The march to Fort Duquesne relied on the building of a road that Braddock and his men constructed by using an old Indian path called Nemacolin’s Path, which gave them a route through the Allegheny Mountains. Braddock's troops marched from Alexandria to Winchester to Cumberland (MD), where the road through the wilderness began. It took them a little over a month to build this road, which was 12 feet wide and 110 miles long and 50 years later, financed by Congress as the first National Road. But it never took them to Fort Dusquesne.

The thickly forested Allegheny Mountains would

The thickly forested Allegheny Mountains would

prove a formidable obstacle fro Braddock's column

The Road to Destruction

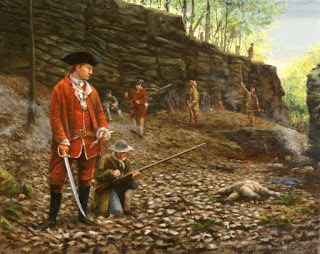

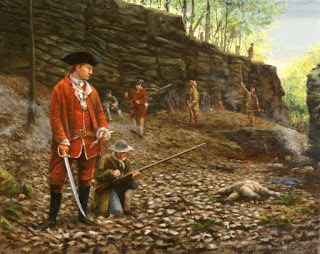

On 9 July 1755, Braddock's force crossed the Monongahela River west of a place called Turtle Creek. Braddock's advance guard of 300 grenadiers and colonials with two cannon under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage (later of Boston infamy) began to move ahead. Washington tried to warn him of the flaws in his plan but Gage ignored him. Confident there were no enemy about, they moved out in column along a narrow path under heavy wooded canopy. Then unexpectedly, Gage's advance guard came upon the French and Indians, who were hurrying to stop the British at the river. But behind schedule and too late to set an ambush, they ran head on into Gage's men. The enemy forces were led by a French Captain named Beaujeu, who fell mortally wounded at the opening of the engagement. The surprise of two forces colliding into each other initially surprised both sides. But the French and Indians rallied quickly and began to pour a murderous fire into the British column. After an exchange of fire, Gage's men fell back. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Indians enveloped them and continued to snipe at the British flanks from the woods on the sides of the road. Musket balls buzzed through the woods, striking tree limbs with a crack and leaves with a zing. But it was the silent rounds that struck man after man. War cries and death from behind the dense undergrowth took also its toll on the British, as did the heat.Then the French regulars began advancing along the road and began to push the British back. The British organized defense collapsed.

Indians ambush the British column

Indians ambush the British column

Despite deadly bullets from seemingly all directions, the British officers tried to rally the men. The British also tried to employ some of their cannon. But again the narrow confines prevented effective use. The colonial militias and troops rallied and engaged the Indians with aimed fire. But some of them received "friendly fire" from panicked British regulars, still attempting to maintain their formations. The fighting lasted several hours. Washington was all over the place, trying to take charge where he could. He rallied small parties and, when Braddock was shot from his horse, he established a rear guard and ensured the wounded commander reached safety. Many other officers died trying to rally and lead their men. The Indians did a good job at picking off the officers, who suffered an extremely high proportion of casualties. Washington himself had two horses shot out from under him and bullets pierced his clothes, but he came out with not one scratch on him. By sunset, the surviving British and colonial forces were fleeing back down the road they had built.

Gen Braddock falls wounded

Gen Braddock falls wounded

The Aftermath

The French won this battle (usually called the Battle of the Monongahela) and suffered 40 casualties - less than 10 percent. The British suffered almost 900 - more than 60 percent. Braddock himself succumbed to his wounds on 13 July. The next day, Washington buried him under the road near the head of the column. The site for his burial was chosen to prevent the French and Indians from desecrating his grave. The outnumbered French did not follow up with a pursuit of the British and the Indians began looting and scalping. These two factors saved the column form further destruction. Hope of a quick British offensive towards the Ohio were decisively crushed on the road of destruction. They would not be revived until three years later, ironically, by use of the northern approach and what became Forbes Road.

This is a rare Yankee Doodle Spies "prequel" post. In many ways the seeds of the American struggle for independence were watered with the blood of the French and Indian War. And in a bold coincidence George Washington's activities in the western (Virginia- Pennsylvania-Ohio) frontier played a role in its beginning. A young Washington had explored the frontier for the then Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. During one mission, an altercation with a party of French and Indians spurred both nations (and much of Europe) into a long and costly war. As one of the few English who had traversed the wilderness,Washington was appointed a special aide to the commander in chief of British forces in North America, Edward Braddock. Washington did not have a Royal commission, however, and was considered a colonial officer. This was no small factor in Washington's later drift from being English to being American.

Washington became a special assistant

Washington became a special assistantdue to his experience in the west

The Campaign

Gen BraddockBecause the war began over a dispute about the western limits of British North America, Britain's first objective was to secure the French forts near the Ohio River. In the summer of 1755, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock, decided to personally lead the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. He had two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th (about 1,350 men), plus some 500 colonial troops and militiamen. To take the forts he brought some artillery and other support troops (engineers, artificers, etc.). Braddock, a confident if not arrogant Scotsman, was confident he could seize Fort Duquesne (today's Pittsburgh) with little difficulty. He would then move north to capture the other French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. Two other campaigns would push directly north into French Quebec but this was to be the main effort.

Gen BraddockBecause the war began over a dispute about the western limits of British North America, Britain's first objective was to secure the French forts near the Ohio River. In the summer of 1755, the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, General Edward Braddock, decided to personally lead the main thrust against the Ohio Country with a column some 2,100 strong. He had two regular line regiments, the 44th and 48th (about 1,350 men), plus some 500 colonial troops and militiamen. To take the forts he brought some artillery and other support troops (engineers, artificers, etc.). Braddock, a confident if not arrogant Scotsman, was confident he could seize Fort Duquesne (today's Pittsburgh) with little difficulty. He would then move north to capture the other French forts, eventually reaching Fort Niagara. Two other campaigns would push directly north into French Quebec but this was to be the main effort. The Western Theater of Operations

The Western Theater of OperationsThe Road to Victory

Sketch of Braddock's RouteThere is some controversy as to which direction the British should take. There were two main routes to the west. One to the south traversed Virginia (West Virginia today) while the other went through western Pennsylvania. Washington was connected to the commercial interests that supported using the southern route. The rationale for both parties being that British military improvements to the road chosen would ensure that route became the main British artery to the west. In either case, Braddock chose the southern route, which ran through much more rugged and densely wooded terrain. The march to Fort Duquesne relied on the building of a road that Braddock and his men constructed by using an old Indian path called Nemacolin’s Path, which gave them a route through the Allegheny Mountains. Braddock's troops marched from Alexandria to Winchester to Cumberland (MD), where the road through the wilderness began. It took them a little over a month to build this road, which was 12 feet wide and 110 miles long and 50 years later, financed by Congress as the first National Road. But it never took them to Fort Dusquesne.

Sketch of Braddock's RouteThere is some controversy as to which direction the British should take. There were two main routes to the west. One to the south traversed Virginia (West Virginia today) while the other went through western Pennsylvania. Washington was connected to the commercial interests that supported using the southern route. The rationale for both parties being that British military improvements to the road chosen would ensure that route became the main British artery to the west. In either case, Braddock chose the southern route, which ran through much more rugged and densely wooded terrain. The march to Fort Duquesne relied on the building of a road that Braddock and his men constructed by using an old Indian path called Nemacolin’s Path, which gave them a route through the Allegheny Mountains. Braddock's troops marched from Alexandria to Winchester to Cumberland (MD), where the road through the wilderness began. It took them a little over a month to build this road, which was 12 feet wide and 110 miles long and 50 years later, financed by Congress as the first National Road. But it never took them to Fort Dusquesne. The thickly forested Allegheny Mountains would

The thickly forested Allegheny Mountains wouldprove a formidable obstacle fro Braddock's column

The Road to Destruction

On 9 July 1755, Braddock's force crossed the Monongahela River west of a place called Turtle Creek. Braddock's advance guard of 300 grenadiers and colonials with two cannon under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage (later of Boston infamy) began to move ahead. Washington tried to warn him of the flaws in his plan but Gage ignored him. Confident there were no enemy about, they moved out in column along a narrow path under heavy wooded canopy. Then unexpectedly, Gage's advance guard came upon the French and Indians, who were hurrying to stop the British at the river. But behind schedule and too late to set an ambush, they ran head on into Gage's men. The enemy forces were led by a French Captain named Beaujeu, who fell mortally wounded at the opening of the engagement. The surprise of two forces colliding into each other initially surprised both sides. But the French and Indians rallied quickly and began to pour a murderous fire into the British column. After an exchange of fire, Gage's men fell back. In the narrow confines of the road, they collided with the main body of Braddock's force, which had advanced rapidly when the shots were heard. The entire column dissolved in disorder as the Canadian militiamen and Indians enveloped them and continued to snipe at the British flanks from the woods on the sides of the road. Musket balls buzzed through the woods, striking tree limbs with a crack and leaves with a zing. But it was the silent rounds that struck man after man. War cries and death from behind the dense undergrowth took also its toll on the British, as did the heat.Then the French regulars began advancing along the road and began to push the British back. The British organized defense collapsed.

Indians ambush the British column

Indians ambush the British columnDespite deadly bullets from seemingly all directions, the British officers tried to rally the men. The British also tried to employ some of their cannon. But again the narrow confines prevented effective use. The colonial militias and troops rallied and engaged the Indians with aimed fire. But some of them received "friendly fire" from panicked British regulars, still attempting to maintain their formations. The fighting lasted several hours. Washington was all over the place, trying to take charge where he could. He rallied small parties and, when Braddock was shot from his horse, he established a rear guard and ensured the wounded commander reached safety. Many other officers died trying to rally and lead their men. The Indians did a good job at picking off the officers, who suffered an extremely high proportion of casualties. Washington himself had two horses shot out from under him and bullets pierced his clothes, but he came out with not one scratch on him. By sunset, the surviving British and colonial forces were fleeing back down the road they had built.

Gen Braddock falls wounded

Gen Braddock falls woundedThe Aftermath

The French won this battle (usually called the Battle of the Monongahela) and suffered 40 casualties - less than 10 percent. The British suffered almost 900 - more than 60 percent. Braddock himself succumbed to his wounds on 13 July. The next day, Washington buried him under the road near the head of the column. The site for his burial was chosen to prevent the French and Indians from desecrating his grave. The outnumbered French did not follow up with a pursuit of the British and the Indians began looting and scalping. These two factors saved the column form further destruction. Hope of a quick British offensive towards the Ohio were decisively crushed on the road of destruction. They would not be revived until three years later, ironically, by use of the northern approach and what became Forbes Road.

Published on July 09, 2017 09:03

June 25, 2017

Things: The Palmetto

A Tour de Force

In the spring of 1776 the British planners in London were intent on turning the stalemate and embarrassing withdrawal from Boston to the cheers and jeers of a rag tag rebel army into a strategic tour de force to end the rebellion that year. With one armada poised to strike the critical port of New York in a right punch, another would make a quick left jab at the equally important port of

Charleston. The latter blow would come first, setting up the rebels for the more powerful knock out in the middle Atlantic colonies. Charleston was the major southern city at the time and had key connections to the important islands in the West Indies, which were always at the forefront f British strategic interests. Dominated by a planter class, South Carolina was not viewed as a particularly rabid rebel stronghold that would succumb quickly. A handful of gallant patriots would show them wrong.

A Last Minute Plan

Lord DartmouthThe British strike at the southern colonies actually began earlier in the year when William Legge, Lord Dartmouth, and Secretary of State for the Colonies ordered General Henry Clinton and Commodore Peter Parker to rendezvous with another armada under General Lord Charles Cornwallis off Cape Fear, North Carolina. Misfortune on land and at sea turned the North Carolina plan to mud. But before Clinton could sail north, Parker reported that a reconnoiter of Charleston indicated the defenses were ill prepared and that a quick strike against Fort Sullivan on Sullivan's Island in the harbor would be successful. After that, the city could be successfully assaulted. Anxious for some "low hanging fruit" after the Tar Heel frustration, Clinton concurred and so they made their way south, anchoring off the city on 7 June 1776.

Lord DartmouthThe British strike at the southern colonies actually began earlier in the year when William Legge, Lord Dartmouth, and Secretary of State for the Colonies ordered General Henry Clinton and Commodore Peter Parker to rendezvous with another armada under General Lord Charles Cornwallis off Cape Fear, North Carolina. Misfortune on land and at sea turned the North Carolina plan to mud. But before Clinton could sail north, Parker reported that a reconnoiter of Charleston indicated the defenses were ill prepared and that a quick strike against Fort Sullivan on Sullivan's Island in the harbor would be successful. After that, the city could be successfully assaulted. Anxious for some "low hanging fruit" after the Tar Heel frustration, Clinton concurred and so they made their way south, anchoring off the city on 7 June 1776.

A City Prepares

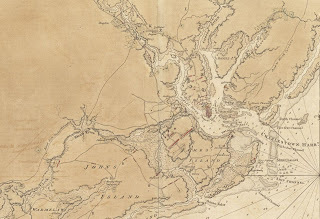

Charleston's waters were treacherous

Charleston's waters were treacherous

as the British would soon discover

But the South Carolinians in Charleston long expected they were a target of the British and feverishly built up the defense works on Sullivan's Island. This was a three sided fort with sixteen foot sand walls bounded by soft wood palmetto logs. The spongy-soft palmetto wood gave way and absorbed the shock of cannon balls - the primary threat to the fort. The fort boasted twenty-five guns of assorted size and caliber with a garrison of over four hundred men. Most importantly, in command of Fort Sullivan was militia Colonel William Moultrie, who would soon prove to be one of the best fighting generals of the war. The city itself had a garrison of over six thousand men - including Continental Line infantry. In command was Major General Charles Lee, a former British officer and widely regarded (especially by himself) as the finest officer in the American cause. Lee's estimate was that Fort Sullivan lay too exposed to the fire of British warships and ordered it abandoned. However, South Carolina Governor John Rutledge overruled Lee, believing it a buffer against a naval onslaught. Geography and hydrography were allies of the defending rebels. The narrow channel into the harbor, with hits commensurate currents and shoals, plagued the British as they plotted where to land and how to position their war ships. It took a month before the were ready to advance on the city that lay just within their grasp.

Colonel William Moultrie's militia

Colonel William Moultrie's militia

staged a gallant defense

Bombs Bursting in Air... Sand.. and Wood

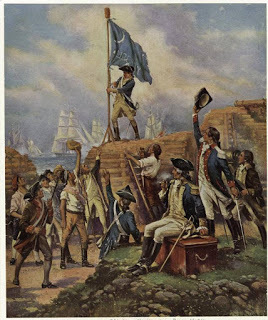

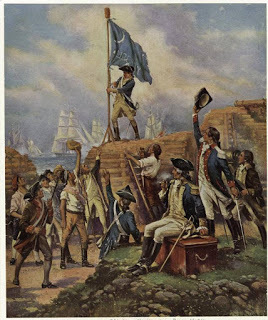

The South Carolina flag hoisted in battle

The South Carolina flag hoisted in battle

boosts morale

On 28 June, a bombardment commenced between Parker's warships aligned off Sullivan Island and Moultrie's raw militia manning the guns protected by sand and palmetto logs. The barrage went on for hours. The British gunners were frustrated that, despite hit after hit, the combination of sand and spongy logs inflicted little damage on the fort. Shot after shot from the warships either bounced off the walls or got absorbed into the soft walls of palmetto. The Americans fired back. But low on gunpowder, Moultrie insisted that each shot be well aimed. In the middle of the hours long engagement a British shot cut down the South Carolina flag. A brave sergeant named William Jasper, in full view of the British and the American, ignored the hail of lead and iron to mount the parapet and restore the flag. The impact on the morale of both sides was telling. As the battle went on, the deliberate fire of the defenders took its toll on the British ships, scoring hit after hit. Things took a final turn against the British when Parker sent three frigates around Sullivan Island to take the defenders in the flank. Unaware of the dangerous waters of the channel, all three suddenly grounded in the shallows. After a struggle, two freed themselves but the third, HMS Acteon remained stuck. The frustrated crew burned it to prevent the rebels taking it.

The savage naval bombardment was decided by shoals, sand and wood

The savage naval bombardment was decided by shoals, sand and wood

Fight on till Dark

Commodore ParkerThe firing continued on both sides. Commodore Parker's flagship had its anchor cable severed by a shot, causing the ship to turn and present its explode stern to American fire. The rounds poured in and one actually passed between Parker's legs as he shouted out commands. The commodore was unhurt but indignant as the shot tore his pants off. When darkness descended on the harbor Parker signaled the fleet to disengage. Exasperated, the British fleet sailed from the harbor. It would be four long years before they would deign to return to face the Carolinians and their palmettos. The next one would end differently, but in 1776, the failed attack presented the British with a near disaster. The Royal Navy incurred well over two hundred casualties - Moultrie's men less than forty. An what of General Clinton? His men had landed on nearby Long Island to prepare for an assault on the mainland once Fort Sullivan fell. With the warships gone this would not be. Instead, they remained exposed there for several weeks before the British transports were able to sail in and they could re-embark.

Commodore ParkerThe firing continued on both sides. Commodore Parker's flagship had its anchor cable severed by a shot, causing the ship to turn and present its explode stern to American fire. The rounds poured in and one actually passed between Parker's legs as he shouted out commands. The commodore was unhurt but indignant as the shot tore his pants off. When darkness descended on the harbor Parker signaled the fleet to disengage. Exasperated, the British fleet sailed from the harbor. It would be four long years before they would deign to return to face the Carolinians and their palmettos. The next one would end differently, but in 1776, the failed attack presented the British with a near disaster. The Royal Navy incurred well over two hundred casualties - Moultrie's men less than forty. An what of General Clinton? His men had landed on nearby Long Island to prepare for an assault on the mainland once Fort Sullivan fell. With the warships gone this would not be. Instead, they remained exposed there for several weeks before the British transports were able to sail in and they could re-embark.

The Result

The British armada returned to New York on the last day of July with ships damaged and sailors and soldiers demoralized. But they soon would get a chance for some sort of retribution when the British launched their massive attack on Long Island in late August. Still, the victory at Fort Sullivan saved the south for four critical years. It introduced the world to a gallant new leader and bolstered morale throughout the Carolinas and the entire rebellion. And in honor of the role of the palmetto in the victory, the noble tree with the soft bark was added to the South Carolina state flag, where it remains to this day.

South Carolina State Flag

South Carolina State Flag

In the spring of 1776 the British planners in London were intent on turning the stalemate and embarrassing withdrawal from Boston to the cheers and jeers of a rag tag rebel army into a strategic tour de force to end the rebellion that year. With one armada poised to strike the critical port of New York in a right punch, another would make a quick left jab at the equally important port of

Charleston. The latter blow would come first, setting up the rebels for the more powerful knock out in the middle Atlantic colonies. Charleston was the major southern city at the time and had key connections to the important islands in the West Indies, which were always at the forefront f British strategic interests. Dominated by a planter class, South Carolina was not viewed as a particularly rabid rebel stronghold that would succumb quickly. A handful of gallant patriots would show them wrong.

A Last Minute Plan

Lord DartmouthThe British strike at the southern colonies actually began earlier in the year when William Legge, Lord Dartmouth, and Secretary of State for the Colonies ordered General Henry Clinton and Commodore Peter Parker to rendezvous with another armada under General Lord Charles Cornwallis off Cape Fear, North Carolina. Misfortune on land and at sea turned the North Carolina plan to mud. But before Clinton could sail north, Parker reported that a reconnoiter of Charleston indicated the defenses were ill prepared and that a quick strike against Fort Sullivan on Sullivan's Island in the harbor would be successful. After that, the city could be successfully assaulted. Anxious for some "low hanging fruit" after the Tar Heel frustration, Clinton concurred and so they made their way south, anchoring off the city on 7 June 1776.

Lord DartmouthThe British strike at the southern colonies actually began earlier in the year when William Legge, Lord Dartmouth, and Secretary of State for the Colonies ordered General Henry Clinton and Commodore Peter Parker to rendezvous with another armada under General Lord Charles Cornwallis off Cape Fear, North Carolina. Misfortune on land and at sea turned the North Carolina plan to mud. But before Clinton could sail north, Parker reported that a reconnoiter of Charleston indicated the defenses were ill prepared and that a quick strike against Fort Sullivan on Sullivan's Island in the harbor would be successful. After that, the city could be successfully assaulted. Anxious for some "low hanging fruit" after the Tar Heel frustration, Clinton concurred and so they made their way south, anchoring off the city on 7 June 1776.A City Prepares

Charleston's waters were treacherous

Charleston's waters were treacherousas the British would soon discover

But the South Carolinians in Charleston long expected they were a target of the British and feverishly built up the defense works on Sullivan's Island. This was a three sided fort with sixteen foot sand walls bounded by soft wood palmetto logs. The spongy-soft palmetto wood gave way and absorbed the shock of cannon balls - the primary threat to the fort. The fort boasted twenty-five guns of assorted size and caliber with a garrison of over four hundred men. Most importantly, in command of Fort Sullivan was militia Colonel William Moultrie, who would soon prove to be one of the best fighting generals of the war. The city itself had a garrison of over six thousand men - including Continental Line infantry. In command was Major General Charles Lee, a former British officer and widely regarded (especially by himself) as the finest officer in the American cause. Lee's estimate was that Fort Sullivan lay too exposed to the fire of British warships and ordered it abandoned. However, South Carolina Governor John Rutledge overruled Lee, believing it a buffer against a naval onslaught. Geography and hydrography were allies of the defending rebels. The narrow channel into the harbor, with hits commensurate currents and shoals, plagued the British as they plotted where to land and how to position their war ships. It took a month before the were ready to advance on the city that lay just within their grasp.

Colonel William Moultrie's militia

Colonel William Moultrie's militiastaged a gallant defense

Bombs Bursting in Air... Sand.. and Wood

The South Carolina flag hoisted in battle

The South Carolina flag hoisted in battleboosts morale

On 28 June, a bombardment commenced between Parker's warships aligned off Sullivan Island and Moultrie's raw militia manning the guns protected by sand and palmetto logs. The barrage went on for hours. The British gunners were frustrated that, despite hit after hit, the combination of sand and spongy logs inflicted little damage on the fort. Shot after shot from the warships either bounced off the walls or got absorbed into the soft walls of palmetto. The Americans fired back. But low on gunpowder, Moultrie insisted that each shot be well aimed. In the middle of the hours long engagement a British shot cut down the South Carolina flag. A brave sergeant named William Jasper, in full view of the British and the American, ignored the hail of lead and iron to mount the parapet and restore the flag. The impact on the morale of both sides was telling. As the battle went on, the deliberate fire of the defenders took its toll on the British ships, scoring hit after hit. Things took a final turn against the British when Parker sent three frigates around Sullivan Island to take the defenders in the flank. Unaware of the dangerous waters of the channel, all three suddenly grounded in the shallows. After a struggle, two freed themselves but the third, HMS Acteon remained stuck. The frustrated crew burned it to prevent the rebels taking it.

The savage naval bombardment was decided by shoals, sand and wood

The savage naval bombardment was decided by shoals, sand and woodFight on till Dark

Commodore ParkerThe firing continued on both sides. Commodore Parker's flagship had its anchor cable severed by a shot, causing the ship to turn and present its explode stern to American fire. The rounds poured in and one actually passed between Parker's legs as he shouted out commands. The commodore was unhurt but indignant as the shot tore his pants off. When darkness descended on the harbor Parker signaled the fleet to disengage. Exasperated, the British fleet sailed from the harbor. It would be four long years before they would deign to return to face the Carolinians and their palmettos. The next one would end differently, but in 1776, the failed attack presented the British with a near disaster. The Royal Navy incurred well over two hundred casualties - Moultrie's men less than forty. An what of General Clinton? His men had landed on nearby Long Island to prepare for an assault on the mainland once Fort Sullivan fell. With the warships gone this would not be. Instead, they remained exposed there for several weeks before the British transports were able to sail in and they could re-embark.

Commodore ParkerThe firing continued on both sides. Commodore Parker's flagship had its anchor cable severed by a shot, causing the ship to turn and present its explode stern to American fire. The rounds poured in and one actually passed between Parker's legs as he shouted out commands. The commodore was unhurt but indignant as the shot tore his pants off. When darkness descended on the harbor Parker signaled the fleet to disengage. Exasperated, the British fleet sailed from the harbor. It would be four long years before they would deign to return to face the Carolinians and their palmettos. The next one would end differently, but in 1776, the failed attack presented the British with a near disaster. The Royal Navy incurred well over two hundred casualties - Moultrie's men less than forty. An what of General Clinton? His men had landed on nearby Long Island to prepare for an assault on the mainland once Fort Sullivan fell. With the warships gone this would not be. Instead, they remained exposed there for several weeks before the British transports were able to sail in and they could re-embark.The Result

The British armada returned to New York on the last day of July with ships damaged and sailors and soldiers demoralized. But they soon would get a chance for some sort of retribution when the British launched their massive attack on Long Island in late August. Still, the victory at Fort Sullivan saved the south for four critical years. It introduced the world to a gallant new leader and bolstered morale throughout the Carolinas and the entire rebellion. And in honor of the role of the palmetto in the victory, the noble tree with the soft bark was added to the South Carolina state flag, where it remains to this day.

South Carolina State Flag

South Carolina State Flag

Published on June 25, 2017 14:28

June 17, 2017

First Fathers

N.B. This is an edited reprise of an earlier post on the subject. With Father's Day tomorrow I decided to revisit the tragic case of the Lynch father - son team.