S.W. O'Connell's Blog, page 5

October 30, 2022

Patriot Scoundrel Part 2

Resignation from the Continental Army did not mean James Wilkinson's military career had ended. Like many of that era and throughout American history, Wilkinson dealt with failure and frustration by going west. In some ways, his resignation was the beginning of a new military career.

Go West, Young ManAfter trading his Continental commission for a state commission, Wilkinson became a brigadier general in the Pennsylvania militia in 1782. The following year, he became a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly. But the canny Wilkinson realized the real potential of developing the new nation's western lands and, in 1784, moved to the Kentucky territory, which was still part of Virginia. Wilkinson immediately got involved in local politics and began advocating for the territory's three counties to separate from the Old Dominion.

Kentucky was claimed by Virginia

Kentucky was claimed by Virginia

Wilkinson's first foray into international affairs occurred a few years later. In April 1787, he traveled to New Orleans, the largest city and capital of the Spanish colony of Louisiana, and met with the Governor, Esteban Rodríguez Miró. The issue was one of the major concerns of Americans living west of the Appalachian Mountains – the hefty tariffs imposed for transiting goods down the Mississippis River. At the time, transporting goods east was economically prohibitive, slow, and physically challenging. This forced the settlers in Kentucky and other western territories to look west, a notion that would draw Wilkinson himself into the embrace of the new lands. The governor agreed to allow Kentucky to have a trading monopoly on the River. How Wilkinson convinced the governor is the genesis of the real controversy that swirled around James Wilkinson. How did this militia general and backwoods envoy of a primitive territory of gringos pull it off?

Agent 13Wilkinson saw the potential of the west linked to the Spanish, who controlled the continent's interior and the lower Mississippi River. It seems Wilkinson engaged in a quid pro quo with the Spanish, offering to represent their interests with the American settlers in the west. In August that year, he swore an affidavit of intent to become a Spanish citizen and swore allegiance to the "Most Catholic King of Spain." Before departing New Orleans for Charleston, SC, he wrote a sort of manifesto in code and cipher, explaining to the Spanish his ideas on "the political future of western settlers" and urging the admission of the western settlers (Kentuckians) as subjects of Spain.

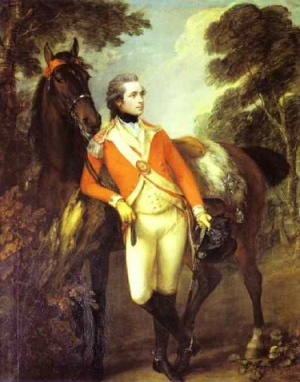

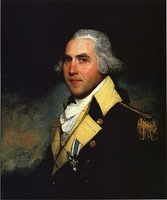

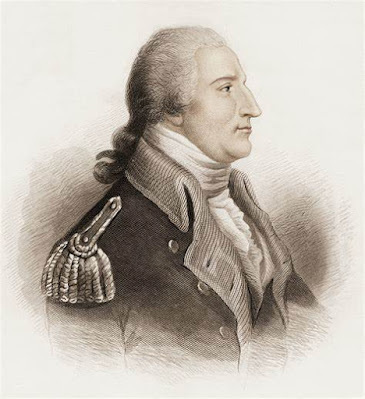

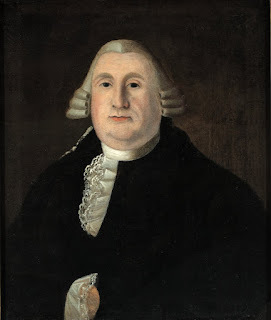

Governor Esteban Rodriquez Miro

Governor Esteban Rodriquez Miro

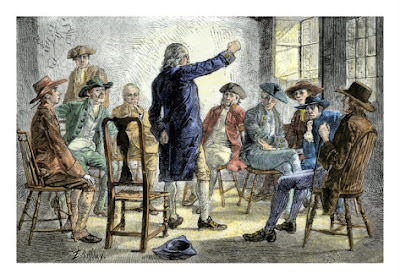

When he returned to Kentucky in early 1788, Agent 13 began a covert campaign to move the sticks in the direction of Spain. He strenuously opposed the proposed US Constitution, the adoption of which would have led to statehood. At a Kentucky convention on the Constitution in November, he schmoozed and charmed many members and got himself named a committee chairman. The canny Wilkinson knew many westerners made joining the Union conditional upon the Union engaging Spain on Mississippi navigation rights. And there was a widespread belief the "easterners" would not go to bat for the over-mountain settlers. Fortunately, Wilkinson's proposal to link separation from Virginia to separation from the United States and a treaty with Spain failed.

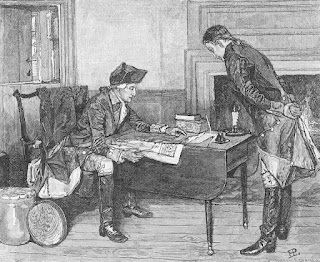

Wilkinson cynically used the Constitutional debate to promote his scheme

Wilkinson cynically used the Constitutional debate to promote his scheme

Wilkinson pivoted from this failure with a new proposal to his Spanish masters. He requested a large tract of land along the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers (today's Vicksburg), a $7,000 pension for himself, and pensions for several prominent Kentuckians. But Madrid did not want complications with the new nation and ordered Miro to break off contact with Agent 13 regarding Kentucky and prohibited any pensions. But, perhaps hedging their bets, Wilkinson continued to receive secret funds.

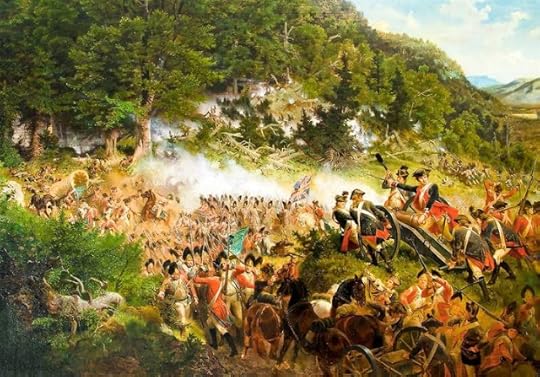

Wilkinson sought thousands of acres near today's Vicksburg

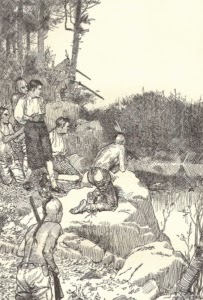

When the Bugle CallsNorth of Kentucky, the Ohio Territory was in flames as the American settlers clashed with the native tribes in a series of savage Indian wars. In 1791, Brigadier General Wilkinson of the Kentucky Militia returned to the new US Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He rose to the rank of brigadier general. At the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, Wilkinson commanded the right wing of Major General Anthony Wayne's newly formed American Legion. The resounding victory broke the back of the Indian tribes and eventually forced the British to abandon their forts on America's northwest frontier. Within two years, Agent 13 was the senior officer in the US Army, but in 1798, Wilkinson was dispatched to the south.

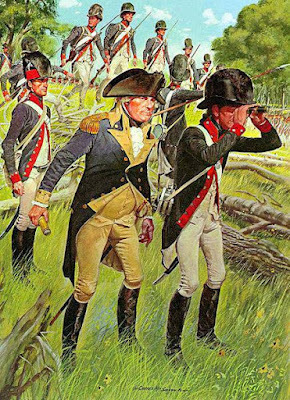

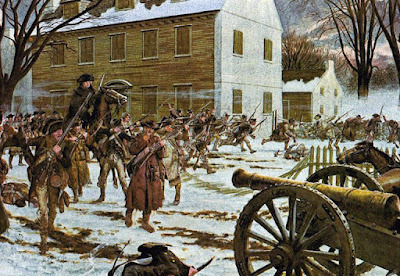

Serving with Mad Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers

Serving with Mad Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers

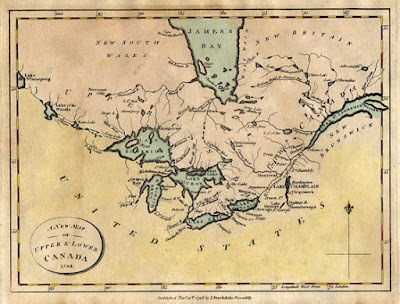

By June 1800, he was again the Army's senior general and, in effect, commander in chief. How such a man could gain those heights is an interesting question. Regardless, he commanded during a critical period in the nation's past – the French Pseudo War, Barbary Pirates, and tensions with Britain. And ironically, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte (Spain had ceded the vast trans-Mississippi region to France) took him back to Louisiana, where he eventually became governor of the vast territory he once conspired with Spain over.

The Louisiana Purchase made America a continental power

The Louisiana Purchase made America a continental power

Now dual-hatted as governor of the Louisiana Territory and commanding officer of the Army, Wilkinson got involved with Aaron Burr. Burr, the disgraced former Vice President and murderer of Alexander Hamilton, had made his way to New Orleans with a vague scheme to seize Mexico from moribund Spain, which was under Napoleon's heel. They hoped to make the territory an independent nation, perhaps with Burr as its President. Wilkinson went so far as to send Zebulon M. Pike to scout the Southwest in preparation for a military venture.

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr

But the British government, which secretly backed Burr's plan, withdrew its support. Now nervous of a failed attempt that would backfire on him, Wilkinson sent a dispatch to President Thomas Jefferson accusing Burr of treason. Burr went on the run but was arrested in Alabama on 19 February 1807 for treason and sent to Richmond, Virginia, for trial. Meanwhile, Wilkinson cut a deal with the Spanish to keep the border with Texas (part of Mexico) neutral while declaring martial law in New Orleans. The audit trail of events is murky, and the details are unprovable, with one side betraying the other (Wilkinson seemingly double-crossing everyone). Burr was acquitted at a treason trial presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall in Richmond, Virginia. The Burr trial did set the legal precedent for future treason trials.

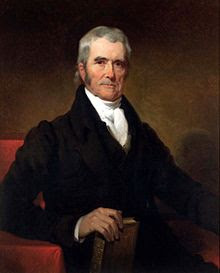

Chief Justice John Marshall

Chief Justice John Marshall

In 1810, Wilkinson took a second wife, Celestine Laveau. Governor Wilkinson got caught up in several other scandals and faced another court-martial in 1811 but was acquitted.

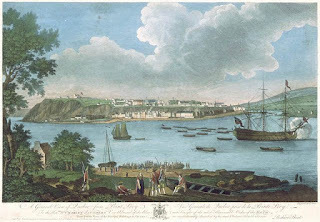

War with Britain, AgainIn 1812, the long-simmering tensions with Great Britain broke into open warfare. In the fall of 1813, newly promoted Major General James Wilkinson took command of the American Northern Army and planned an invasion of Canada. Wilkinson launched a campaign to capture the British naval base at Kingston, sail up the St. Lawrence River, and attack Montreal. This provided a chance for Wilkinson to prove his mettle on the field of battle.

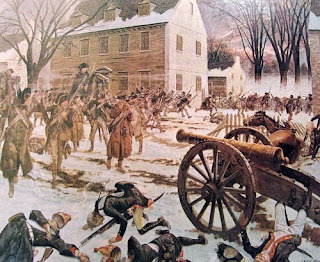

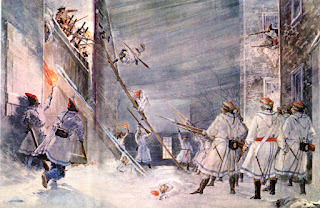

Battle of Chrysler's Farm ended Wilkinson's military career

Battle of Chrysler's Farm ended Wilkinson's military career

Poor coordination and even poorer weather hampered his two-pronged movement, and soon Wilkinson's main column was on its own. Several engagements pushed the Americans back, and a final battle occurred at Chrysler's Farm. The British-Canadian forces soundly beat the Americans in a five-hour fight under snowy conditions.

Final Court MartialWilkinson's invasion had left his base vulnerable to attack. As a result, British and Canadian forces captured Fort George and Fort Niagara in December. His final campaign was over. He faced a court martial for his actions – this time convicted. The patriot scoundrel's conviction finally brought his long and sketchy military career to a dishonorable end.

Major General Wilkinson's career endedwith a final court-martial

Major General Wilkinson's career endedwith a final court-martial

But resilient as ever, Wilkinson wrangled an appointment as America's Envoy to Mexico during the struggle for Independence against Spain. When Mexico won in 1821, Wilkinson leveraged his position to request a land grant in Texas. It was a long wait for the new Mexican government's approval, and the 68-year-old Wilkinson died in Mexico City on 28 December 1825 and was buried there in a vault under Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel - the Church of Saint Michael the Archangel.

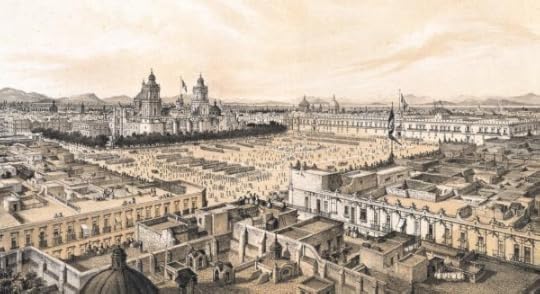

The American scoundrel ended his life in a foreign capital

The American scoundrel ended his life in a foreign capitalAgent 13's Legacy

During his life, many suspected the murky Wilkinson connection to the Spanish. But nothing could be proven. When surveying Missippi's boundary, American cartographer Andrew Ellicot reported his suspicions to President Thomas Jefferson but was rebuffed. One wonders whether Wilkinson was an American double agent, or perhaps the Americans thought he was their double agent. Regardless, James Wilkinson was a proven schemer, mover, and shaker who managed to put himself at the center or, better still, in the shadows of some of the most dramatic touch points in America's early years.

An agent's tools of the trade: the cipher wheel

An agent's tools of the trade: the cipher wheel

September 25, 2022

Patriot Scoundrel

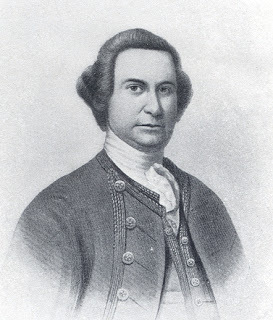

As I continue to profile characters in or mentioned in my upcoming novel, The North Spy, there is one in a cameo role who seemed to be at the periphery of interesting events–– not always in a good way. And that is an understatement. James Wilkinson is one of those enigmatic characters who managed to place himself where he could do the most good for–– himself!

James Wilkinson

James WilkinsonVarious historians and writers use James Wilkinson's own writings, and his account of things, while first-hand, is not unbiased. Wilkinson appears in The Cavalier Spy and The North Spy, and I do not portray him very favorably. He becomes a bit of a foil for my protagonist, Jeremiah Creed, and adds a certain ambiguity to things. This will be part 1 of a 2-part treatment of Wilkinson.

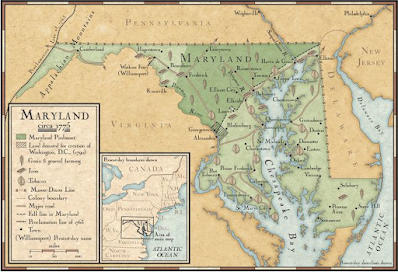

Chesapeake RootsMaryland was the birthplace of James Wilkinson, whose family were mid-level landholders in Calvert County. He was born to Joseph and Althea Wilkinson in Charles County on 24 March 1757. He spent time on the family estate, Stoakely Man, which his father inherited from his grandfather, but by the time James was seven, debt caused his father to lose the estate, which was auctioned off in lots. A small parcel was retained, but James's older brother Joseph inherited it.

Wilkinson hailed from Maryland's Western Shore

Wilkinson hailed from Maryland's Western ShoreA landless second son often had few prospects, but fortunately, his grandmother had enough money and connection to ensure a decent education: first tutoring in his early years and later the study of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. This would have given him a boost in his career, but politics and the struggle with Britain got in the way of his path to becoming a surgeon.

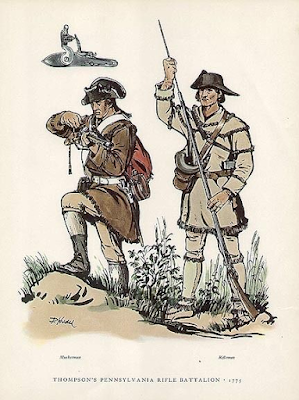

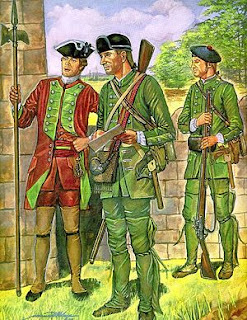

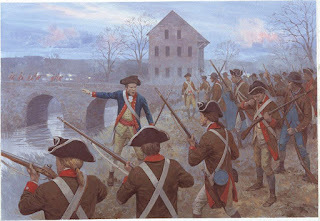

Revolutionary YouthJames Wilkinson was just eighteen when the "Shot Heard Round the World" changed everything and put him on a pathway to potential military glory. He began his service in 1775 with Thompson's Rifle Battalion, where he was promoted to captain that September. The battalion, formed from "Associator" companies, marched to Massachusetts and joined the newly formed army assembling around Boston.

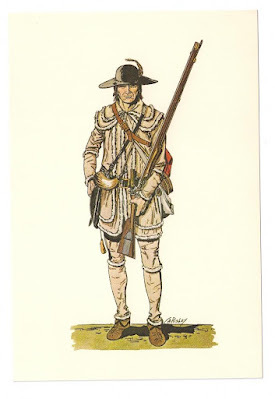

Pennsylvania Infantry

Pennsylvania InfantryNew England Triumph

But Wilkinson, who we'll see was quick to spy opportunity, soon got himself seconded to General Nathanael Greene as an aide–– a role he would often play to his advantage. By his account, he helped lay in the batteries on Dorchester Heights, an act that sent the British packing.

Dorchester Heights

Dorchester Heights

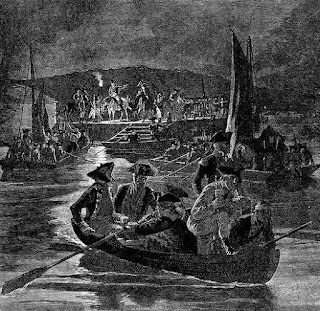

He marched with the Continental Army as it scurried south to defend New York in spring 1776. This time as a company commander in Thompson's battalion, on 1 July 1776, The First Pennsylvania Regiment of the Continental Line would play a role in the brutal fighting on Long Island in August.

Retreat from Long Island

Retreat from Long Island

The campaign to wrest Canada from the British was going badly. While General Washington and Howe danced their armies around New York and across the Jerseys, another front was raging in hot combat but in a much colder climate. Wilkinson went north with reinforcement for Benedict Arnold, who assumed command when the expedition's commander, General Richard Montgomery, was mortally wounded in the assault of Quebec that December. Wilkinson got himself appointed as an aide to Arnold, but the arrival of a relief army under General John Burgoyne sent the Americans into a retreat back to New York.

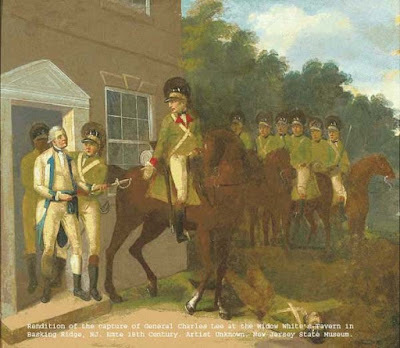

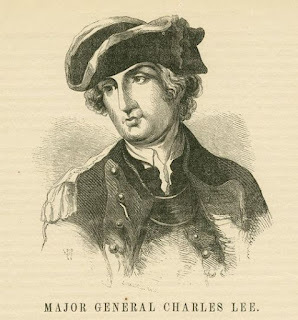

Arnold would soon fight the invading British to a standstill, but by then, the now Major Wilkinson had gotten himself reassigned as an aide to General Charles Lee, second in command of the Continental Army, during Lee's controversial (he lagged) march from the Hudson Highlands to join Washington outside Philadelphia in December 1776. On a cold, snowy morning, Wilkinson was with Lee, who had left his division and ridden to Widow White's Tavern in Basking Ridge, when British dragoons attacked him under Banastre Tarleton. Lee was captured, but Wilkinson escaped. His account of this is self-serving to him and denigrates Lee. My account in The Cavalier Spy tries to even things up a bit.

Wilkinson escaped Lee's fate at Widow White's

Wilkinson escaped Lee's fate at Widow White's

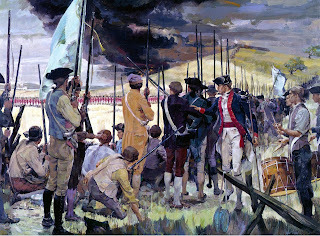

By the summer of 1777, Wilkinson was a Lieutenant Colonel and Assistant Adjutant to the new commander of the Northern Department, Major General Horatio Gates. He played an active staff role in the dramatic battles and the British Army's surrender. In my novel, The North Spy, he appears competent but manipulative in his interactions with Horatio Gates, Benedict Arnold, Dan Morgan, and my fictional protagonist, Jeremiah Creed.

General Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga

General Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga

Wilkinson burst onto the national scene when Gates selected him to ride to Congress with news of the Saratoga victory–– a direct affront to General George Washington and a precursor to upcoming political machinations such as the "Conway Cabal." Wilkinson tarried in his delivery to settle personal matters and, of course, embellished his role. He did this so well that Congress brevetted the twenty-year-old lieutenant colonel a brigadier general even though he had not commanded more than a company of troops. This promotion, and suspicions of his and Gates's connections to the Conway Cabal, caused many officers to turn against him. In fairness, this was a typical reaction among the Continental Army's higher ranks.

Wilkinson's news to Congress bypassed Washington

Wilkinson's news to Congress bypassed Washington

With promotion in November 1777 came a new job–– a seat on the Board of War. Various political intrigues and accusations led to him leaving the prestigious Board, which was charged with overseeing the conduct of the war in the spring of 1778. A year later, Congress found another administrative post for him–– Clothier General of the Army. Clearly, his reputation as a politician, lack of previous command experience, and getting cross with the commander-in-chief precluded a field command. But things did not go well, and he resigned from the position in the spring of 1781.

Wilkinson was an unlikely clothier for the Continental Army

Wilkinson was an unlikely clothier for the Continental Army

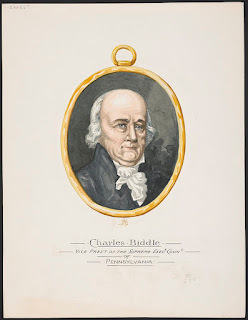

Before we wrap up Wilkinson's Continental Army career, we'll examine his personal life. While stationed around Philadelphia, the newly-breveted general married Ann Biddle. The couple wed on 12 November 1778. Anne was from one of the most prominent families in Philadelphia. Her first cousin was Charles Biddle, who served as a merchant mariner (privateer), a light infantry officer, and a naval officer during the war. Biddle later became highly prominent in Pennsylvania politics and was closely connected to Aaron Burr. These connections would play out in Wilkinson's future in surprising ways as our story shifts to the frontier.

Connection to Biddle would have second-order effects

Connection to Biddle would have second-order effects

August 27, 2022

The Saint

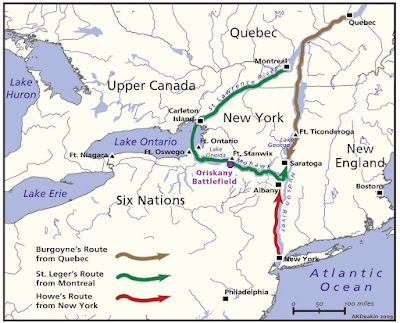

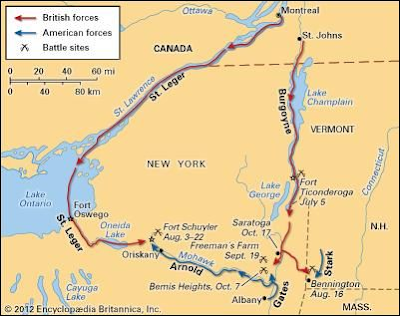

Not the infamous TV Simon Templar portrayed by Roger Moore but a son of County Kildare, a professional British officer and a critical player in the Saratoga Campaign. In fact, Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger’s thrust from the west was the third prong of the triple pincer against Albany in a grand plan to defeat the Americans once and for all. Often portrayed as an afterthought, St. Leger's role was a unique part of a strategy aimed at overwhelming the rebels in New York.

Roger Moore as Simon Templar

Roger Moore as Simon TemplarBorn in the Land of Saints and Scholars

Barrimore Matthew St. Leger was born May 1737 in County Kildare, Ireland, a nephew of the Fourth Viscount Doneraille. This is actually his baptism date, as the Irish tradition was to record those more scrupulously than births in an era when infant mortality was widespread. Barry’s father, Sir John St. Leger, was a leading Irish judge. His brother, Anthony St Leger, variously served in Parliament and the military, achieving the rank of major general.

Anthony St. Leger

Anthony St. LegerSaint to Scholar to Soldier

The high-born St. Leger attended the prestigious halls of Eton and Cambridge before signing on as an ensign with the 28th Regiment in April 1756. His regiment immediately sailed to North America and the French and Indian War. St. Leger served with some distinction under British General James Abercromby.

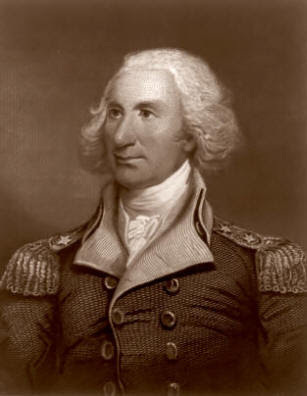

James Abercromby

James Abercromby

By 1758, the young Irishman was a captain of the 48th Regiment and took part in General Jeffery Amherst’s Siege of Louisbourg. St. Leger was appointed brigade major (a staff position, not a rank) during General James Murray’s advance upon Montreal in 1760, and in September 1762, St. Leger was promoted to the rank of major in the 95th Regiment. The French and Indian War had been good to the Viscount’s nephew. The Revolutionary War would prove a mixed bag.

Jeffery Amherst

Jeffery Amherst

When resistance broke out into rebellion and war in 1775, St. Leger was serving as lieutenant colonel of the 34th Regiment. Barry arrived in Canada in the spring of 1776. He and his regiment helped Governor-General Guy Carleton drive out the invading American forces throughout the summer and fall of that year. St. Leger and the 34th recaptured Fort Ticonderoga during the drive south but withdrew when Carleton decided to end the campaign and return north into winter quarters.

Guy Carleton

Guy Carleton

The irrepressible General John Burgoyne arrived from England in early 1777 with reinforcements from Lord Germain, the Minister for Colonies. “Gentleman Johnny” also brought along his bold strategy of a three-pronged move for capturing Albany, New York. His goal was to sever stiff-necked New England from the other colonies. What would happen after that was unclear.

A little regarded but critical part of Burgoyne’s scheme was a supporting move along the Mohawk River to draw off rebel strength, punish rebel farmers, and join his main force near Albany. Burgoyne selected St. Leger to lead the western prong because of his experience and skill in fighting through the northern wilderness.

John Burgoyne

John Burgoyne

On 23 June 1777, St. Leger’s mixed force of some 800 British regulars, Hessians, Loyalists, and Canadians departed Montreal. They comprised Loyalists under Colonel John Johnson and Major Walter Butler, plus some British and Hessians. St. Leger, now breveted a brigadier general for the campaign, wanted speed over firepower, so he decided to leave heavier artillery behind so as not to impede the wilderness march. He did take along a few light guns, but these would prove not up to the task.

Barry St. Leger

Barry St. Leger

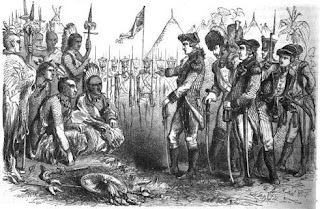

On 25 July, a flotilla of British ships and barges landed St. Leger’s force at Oswego, New York. They were soon joined by 800 native warriors led by Iroquois War Chief Joseph Brant and Seneca War Chief Cornplanter.

Chief Joseph Brant

Chief Joseph Brant

They swiftly marched up the Mohawk River valley according to Burgoyne’s plan, passing friendly Iroquois villages and undefended farmland.

Iroquois village on the Mohawk River

Iroquois village on the Mohawk RiverBut St. Leger soon arrived at his first obstacle – rebel-held Fort Stanwix (today’s Rome, NY), stoutly defending the upper valley from his forward advance. To St. Leger’s consternation – reports by Indian scouts and spies proved true.

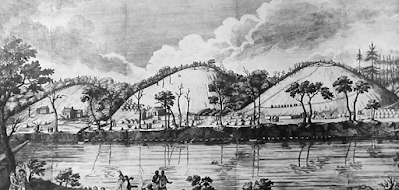

Fort Stanwix

Fort Stanwix

The Continental Army’s Northern Department commander, General Philip Schuyler, recently repaired the fortification and garrisoned it with 750men of the 3rd New York Regiment under Colonel Peter Gansevoort with Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willet as his deputy.

Peter Gansevoort

Peter GansevoortFort Stanwix Besieged

When St. Leger arrived outside Fort Stanwix, he sprang into action, conducting a “leader’s reconnaissance" of the post. He quickly realized he had underestimated the size and strength of the place. Lacking the heavy guns to pound the fort into submission, St. Leger ordered his Indian allies to encircle it in what was a very soft siege.

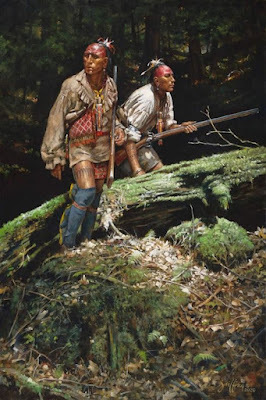

Iroquois Braves surround Fort Stanwix

Iroquois Braves surround Fort Stanwix

He then tried to bluff the defenders into surrender by parading his entire force before them. Ironically, the many native warriors convinced the Americans they would be massacred if they surrendered. St. Leger’s surrender summons fell flat. Frustrated, he ordered a bombardment of the fort, but his small-caliber guns proved ineffective.

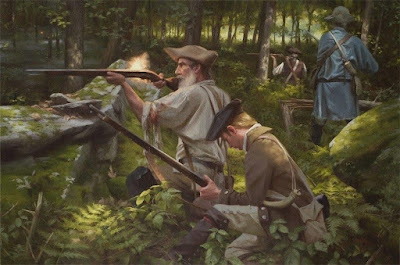

Oriskany AmbushFarther up the valley to the east, the Tryon County militia rallied when word of the British invasion reached them. A column of 800 men under Colonel Nicholas Herkimer marched out of Fort Dayton, intent on relieving Stanwix. But Molly Brant, sister of Chief Joseph Brant, alerted St. Leger of the new threat. He responded by throwing a force of Loyalists and Indians into the dense forest near the village of Oriskany, to the east.

Molly Brant

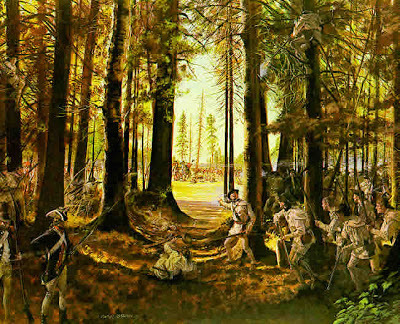

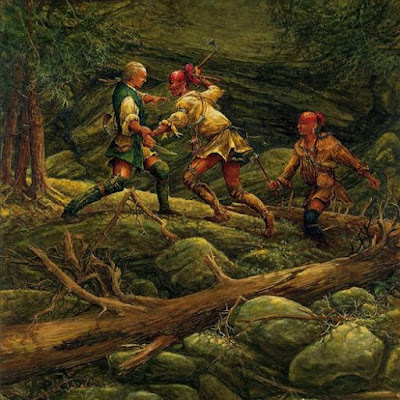

Molly BrantOn 6 August, under a thick canopy of ancient woodland, they sprung a devastating ambush on the militia, which was halfway across a deep gulley. A terrific firefight ensued. Curtains of lead tore chunks of hardwood and scythed down brush and branches. Men fell on both sides, but with so many dead and wounded, including Herkimer, the Tryon County militia withdrew under cover of the dense gun smoke.

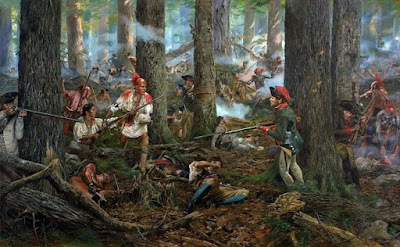

Oriskany Ambush & Firefight

Oriskany Ambush & Firefight

Back at Fort Stanwix, the Americans had a few tricks of their own. With the besiegers reduced to sending forces to Oriskany, Lieutenant Colonel Marinus Willet successfully sortied from the defense works and seized St. Leger’s camp, thoroughly plundering it. The loss of supplies disheartened the tribesmen, and they began abandoning St. Leger’s column.

Marinus Willet

Marinus Willet

Desperate, St. Leger again threatened the defenders with massacre unless they capitulated. Gansevoort agreed to a truce but resolved to defend the post. He sent Willett to ride through British lines to Stillwater, report the situation to General Philip Schuyler, and request he send relief.

Arnold’s DeceptionAnd so, it was. General Benedict Arnold put together a force to drive the British from Stanwix. But Arnold was as cunning as he was brave and bold. He sent a deranged man named Hon Yost to “desert” the British. His rantings of a relief force “more numerous than the leaves on trees” panicked the remaining warriors, who fled west.

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold

Realizing his hopeless situation, St. Leger was forced to give up his siege of Fort Stanwix. On 25 August, his regulars, Hessians, Loyalists, and a few faithful Indian allies, trudged west along the Mohawk and departed for Canada. St. Leger’s failure to reach Albany and support Burgoyne directly contributed to the ultimate capitulation at Saratoga in October 1777.

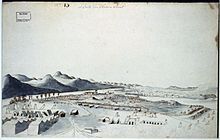

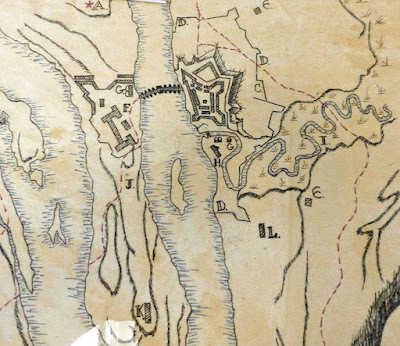

Return to TiconderogaSt. Leger did not mull over his failed campaign. Instead, he sprang into action once back at Montreal, coaxing scarce forces from Governor Guy Carleton. He led his command south to reinforce Burgoyne directly. But they had just arrived at Fort Ticonderoga when word of the Saratoga surrender arrived in October 1777.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga

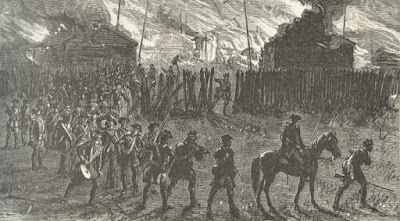

For the remainder of the war, St. Leger stayed in active command and came into his own as an irregular warfare leader. He led several raids against the Americans in upper New York, which became the scene of bloody partisan and guerrilla-style warfare throughout the war. Spying, betrayal, raids, ambushes, assassinations, and torching would devastate upper and central New York.

Loyalist raiders

Loyalist raiders

St. Leger was behind a failed attempt to kidnap General Philip Schuyler. In 1781, the new commander in Canada, General Frederick Haldimand, dispatched him back to Ticonderoga to meet with disaffected rebel leader Ethan Allen. But the scheme to break Vermont from the rebels failed.

Philip Schuyler

Philip Schuyler

Unlike most of his fellow officers, St. Leger did not return to England or sail to another theater after the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Instead, he remained in Canada. In 1784 he was promoted to brigadier general and succeeded Haldimand as commander. But by 1785, poor health from the ravages of campaigning forced him to give up his command and retire from active service. St. Leger died in Worksop, Nottinghamshire, England, on 23 December 1793.

Frederick HaldimandLegacy

Frederick HaldimandLegacySt. leger's legacy is mixed. He was a talented tactical leader of troops who could plan and organize complex operations over great stretches of wilderness. Yet his only major independent command failed through a mix of poor decision-making (remember the heavy guns?), failure to keep his native allies in hand, and unexpected resistance by more robust than anticipated American forces.

But unlike his commander Burgoyne, "The Saint" knew when to quit and extracted his troops from a precarious situation. Facing Fort Stanwix's defenders combined with General Benedict Arnold's relief force would have surely resulted in the annihilation of his force. Instead, his troops would live to fight on and harass and threaten upper New York for the remainder of the war, while Burgoyne’s stubborn refusal to consolidate caused his larger army to march off to rebel prisons.

July 31, 2022

The Old Patroon

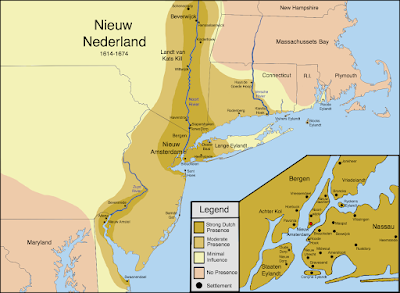

The Dutch settlers of New York and East Jersey were among the most industrious Europeans to settle in North America. Thrifty, ambitious, and organized, they managed to grow their foothold on Manhattan into a range of settlements that dwarfed the tiny homeland they left. They named the colony New Netherlands. It was ruled by a network of exceedingly wealthy landholders, called patroons, who had been granted large tracts of land to cultivate and manage.

The Dutch WayOriginally these patroons had the right to establish courts and taxes. Things changed when the British arrived in the late 17th century, and in 1775 the patroonships were abolished and renamed estates. By that time, a sizeable middle class had blossomed from Long Island and Manhattan, along the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers. Many had spilled across the Hudson and settled along the Hackensack River of East Jersey. The cultural and economic power of the Dutch still permeated the renamed colony of New York, and they played an influential role in the War for Independence.

First FightLike many of his generation, he cut his military teeth during the French and Indian War, where Schuyler served as a captain in the New York militia. His cousin, Lieutenant Governor James Delancey, had commissioned him. His connections indeed ran wide and deep. The wealthy young Schuyler raised a local company. Schuyler took part in some of the key battles of upper New York, including Lake George, Oswego River, Carillon, and Fort Frontenac. At Oswego, he served as a quartermaster until it fell to the French.

Philip Schuyler

Philip Schuyler

Continental Congress

Continental CongressAll InDespite his wartime experience, his appointment was more to secure New York's support for the Cause than to utilize his military potential. This kind of regional quid pro quo was common and engaged in to ensure the disparate colonies were "all in." Virginia's Colonel George Washington had edged out Massachusetts John Hancock as commander-in-chief of the Army for the same reason.

John Hancock

John Hancock

Schuyler leveraged strong Iroquois connections

Schuyler leveraged strong Iroquois connections

Night Assault of Quebec

Night Assault of Quebec

John Sullivan

John Sullivan

Lake Champlain Basin

Lake Champlain Basin

American defeat at Valcour Island

American defeat at Valcour Island

Gibraltar of the North

Gibraltar of the North

Despite Schuyler's measures to blunt another British thrust, General John Burgoyne's 8,000-strong armada sailed down Lake Champlain and marched uncontested into Fort Ticonderoga. Its commandant, General Arthur St. Clair, realizing his under-strength forces would only march off to British prison ships, had evacuated hours before the British arrived – a fateful decision. Schuyler approved St. Clair's move and ordered a "Fabian Defense." The garrison melted into the dense forest, felling trees and building abatis and other obstacles hoping to slow Burgoyne's forces, who were in hot pursuit. The British were being sucked into the wilderness and away from the waterways that provided their route south and supplies.

Arthur St. Clair

Arthur St. Clair

Major General Schuyler

Major General Schuyler

But the blame for Ticonderoga fell on Schuyler's shoulders, and General Horatio Gates once more replaced him. Gates stopped the British in two pitched battles near Saratoga, where he would accept their surrender in October 1777.

Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates

Schuyler demanded and received a court martial in 1778, which cleared him of wrongdoing, but he resigned his commission and returned to Congress in 1779. Philip Schuyler's legacy was to be the only major general in the Continental Army never to fight a pitched battle. He continued to provide advice to his friend, General Washington, as his grasp of strategy and logistics was acknowledged. His understanding of Indian matters also helped Washington, who solicited his counsel during the 1779 campaign against the Iroquois.

General Washington valued Schuyler's counsel

General Washington valued Schuyler's counsel

Despite New England rumors calling him a Tory, Schuyler was a target of the British. He lived under the threat of personal attack. General John Burgoyne's retreating forces burned Schuyler's country home in October 1777. He later rebuilt it, and it is open to the public.

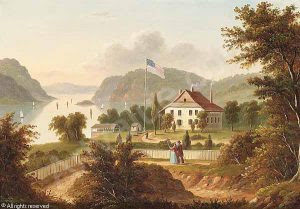

Schuyler's Estate Home rebuilt

Schuyler's Estate Home rebuilt

In another incident in 1780, British agents attacked Schuyler's Albany mansion under cover of darkness. The attempt, whether kidnapping or murder, was thwarted. Following the incident, Schuyler was under the protection of a bodyguard of Continental Army soldiers. But he remained a target. On 7 August 1781, Schuyler foiled a kidnapping plot led by John Walden Meyers. It failed when Schuyler managed to flee his Albany mansion. The Albany mansion variously served as his home, Northern Army headquarters, political center, and business office.

Schuyler Mansion in Albany

Schuyler Mansion in Albany

The old patroon had powerful New York connections, and post-war, he concentrated on local politics by serving in the New York State Senate. He also served as a delegate to the state Constitutional Convention in 1789 and lobbied strongly on behalf of the new American Constitution. Schuyler was a businessman as well as a soldier and politico. He grew the size of his estate near Saratoga after the War, reaching tens of thousands of acres, a score of slaves and tenant farmers, plus a store and mills for flour, flax, and lumber. To move his goods down the Hudson to market, he constructed schooners, naming the first Saratoga.

Schuyler had his own fleetFederalist

Schuyler had his own fleetFederalistUnsurprisingly, Schuyler was one of the first two US Senators appointed to represent the state in the new Congress. Naturally, the long-time ally of George Washington now supported his president as a staunch Federalist. He especially supported the solid economic policies put forth by the Secretary of Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, who had married Schuyler's daughter, Elizabeth (more on her below). The whirl and swirl of New York politics saw him lose his seat in1792 but regain it in 1797. State legislatures, not the people elected senators then – connections got you in or threw you out. Schuyler was the first New Yorker to join the controversial Society of Cincinnati, a fraternity of Revolutionary War officers viewed by some as a burgeoning aristocracy. But most senior officers, including George Washington, had joined the organization.

President George Washington

President George WashingtonDomestic Life

Schuyler had married into the uber-wealthy and powerful Van Rensselaer family when he took the hand of Catherine Van Rensselaer on 7 September 1755 at Albany. They would have a large brood of 15 – eight who lived to adulthood. His second child, Elizabeth, would later marry young Continental Army officer Alexander Hamilton. She would gain modern fame through the musical Hamilton. Still, during her life, she used his legacy and family connections to engage in philanthropic projects, not the least being the first orphanage in New York City.

Schuyler's ill health caused him to resign from political life in 1798. He died at his home in Albany in 1804, leaving a mixed legacy of success and failure. His critics considered him too cautious or reticent to fight. Some called him treasonous – especially his New England enemies – constantly wary of his aristocratic Dutch heritage. And regional strife played a role here. They viewed Schuyler as supporting his own New York's land claims over those of Vermont. Ironically, Schuyler later supported the Vermonters, drawing the ire of influential New York Governor George Clinton. Fame, wealth, and power brought powerful enemies to the Old Patroon.

Schuyler Grave and MemorialAlbany Rural Cemetery

Schuyler Grave and MemorialAlbany Rural Cemetery

June 30, 2022

Forts of the North

Although most of North America was heavily wooded in the 18th century, the vast region of mountainous woodlands that stretch from New England to the Great Lakes along the northern tier of New York made travel a slow, ponderous, and often treacherous affair. For centuries, however, the native tribes of the region, such as the Iroquois, Abenaki, and Huron, traversed the area with little difficulty. Generations of knowledge handed down to the tribes turned the slightest break in the woods, footpath, or deer trail into their highway.

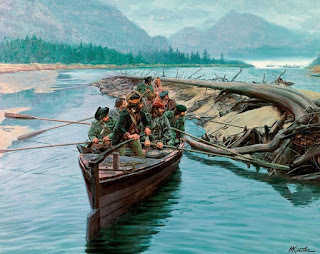

But modern (18th-century modern) travelers, such as explorers, hunters, trappers, and of course, armies, needed a better way to negotiate the wilderness that seemed, at times, overwhelming. And for this, they turned to nature as well. In this case, the excellent network of waterways left by the glaciers, which receded at the end of the last great ice age.

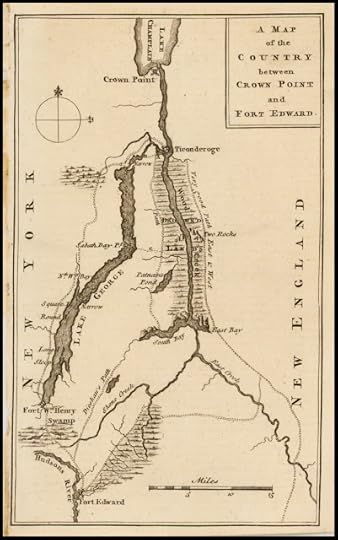

The resulting waterway stretched, with little interruption, from the Saint Lawrence River to the Lower New York harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. For this narration, the northernmost waters of Lake Champlain and Lake George will be the focus. Several forts constructed to defend the waterways played a prominent role in the numerous clashes between the French/Indians and the British in the 18th century.

This is a tale of two forts as Britain and France squared off to control Lake Champlain, the most extensive body of water south of the Great Lakes and west of the Atlantic Ocean. Like an opposed left thumb, a small peninsula just into the lake from Champlain's western shore dominates the approach from either direction. As the first "battlespace" between Canada and the colonies, it would play a pivotal role in the many 18th-century struggles for a North American Empire.

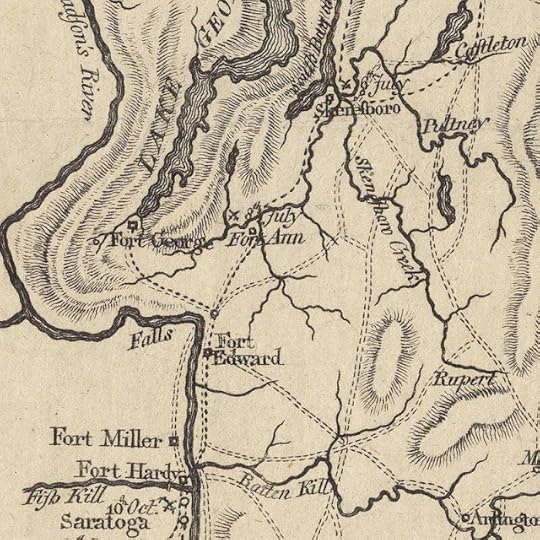

Crown Point and other Forts of the North

Crown Point and other Forts of the North

The French were the first to appreciate the strategic location. In 1734, they began constructing a base they named Fort St. Frederic, which they used to launch raids against the British settlers in central New York and New England (the hated Bostonnais). During the French and Indian War, the British were determined to neutralize the base and finally were able to take it in 1759. They immediately built new defense works on the site, which they dubbed "His Majesty's Fort of Crown Point." The new works at Crown Point spanned more than seven acres – one of the largest in North America.

Between the French and Indian War and the outbreak of the American Revolution, Crown Point (like all the others along the waterway) became less important and was essentially mothballed. However, in 1775 the Americans saw the value in seizing the unmanned cannons and ordnance for the new Continental Army. It served as a base for American forces invading Canada in 1775 and defending New York in 1776. Crown Point fell into British hands once more when General John Burgoyne launched his 1777 campaign to divide the colonies. It remained in British control even after Burgoyne's surrendered in October of that year.

Ruins of the fort at Crown Point

Ruins of the fort at Crown Point

Fort Ti is the big daddy of forts, the big kahuna, The Gibraltar of the North, and figures largely in my novel, The North Spy. The name "Ticonderoga" comes from the Iroquois word tekontaró:ken, meaning "it is at the junction of two waterways" Situated between lakes Champlain and Lake George, the site dominated the transit route between Canada and the American colonies, making it a strategic a place as any in North America. I visited once when I was very young and twice as an adult and have not begun to scratch the surface of its historical and geographic significance.

The Gibraltar of the North

The Gibraltar of the North

Recognizing that strategic significance, the French first fortified the site in 1755 and named it Fort Carillon. It would figure significantly in the upcoming campaigns of The French and Indian War. The power of the place proved itself in 1758 when 4,000 French defeated 16,000 British troops in a bloody battle aptly called The Battle of Carillon. But all forts are meant to be taken, and in 1759, the British returned. This time, they drove out the small French garrison.

Fighting at Fort Carillon

Fighting at Fort Carillon

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, local leaders recognized the importance of the fort and its ordnance. In 1775, the American siege of Boston had the British ringed but lacked guns to conduct a proper siege and the gunpowder to risk an all-out assault.

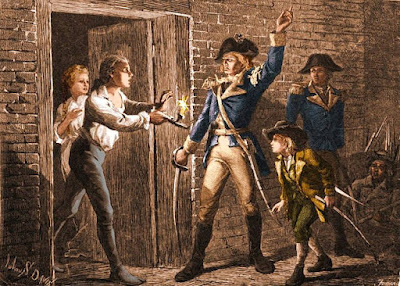

Taking Ticonderoga by surprise

Taking Ticonderoga by surprise

On 10 May 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen led a mix of GreenMountain Boys and other local militia and captured the startled garrison in a coup de main. General George Washington, the new commander in chief of the new Continental Army, dispatched Colonel Henry Knox to Ticonderoga to bring the scores of heavy guns and powder back to Boston. When the captured guns were placed in the battery over the city in March 1776, General William Howe ordered the evacuation of Boston.

Knox dragged Ticonderoga's guns to Boston

Knox dragged Ticonderoga's guns to Boston

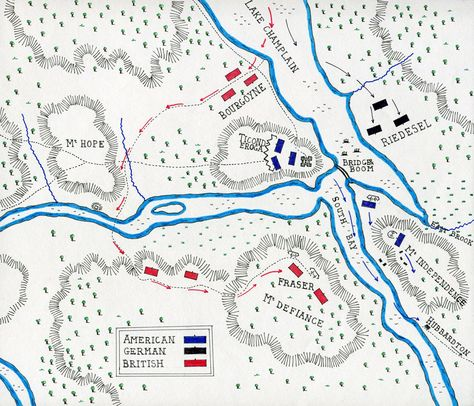

During the summer 1777 campaign led by Brtish General John Burgoyne, Ticonderoga was in the cross hairs. The massive fort was the key to Burgoyne's success as it would provide his logistics base and jump-off point for his final thrust to Albany and a link-up with General Henry Clinton's army in New York City.

General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne

The Americans recognized the threat and the importance of defending the fort, but the defenses had been neglected, and the garrison had insufficient numbers, munitions, and supplies. Ironically, great fortresses suck in resources and are vulnerable if not fully manned. Such was the situation facing the new American commander of the garrison, General Arthur St. Clair. Ticonderoga was surrounded by mountains that, if taken, placed the fort and garrison in jeopardy. St. Clair failed to secure those hills, but the enterprising Brish did – dragging a gun battery to the crest of Mount Defiance. Recognizing the danger, St. Clair ordered a night withdrawal, abandoning The Gibraltar of the North without firing a shot.

St. Clair ordered the surrounded and undermanned fort abandoned

St. Clair ordered the surrounded and undermanned fort abandonedFort Ann

Nestled in the rugged woodland east of the southern tip of Lake George, Fort Ann sits at the edge of the rugged land, and the beginning of the pass into lowland approaches to Fort Edward and the Upper Hudson Valley.

Fort Ann protected the approach to the Hudson

Fort Ann protected the approach to the Hudson

Recognizing its strategic position, the British erected a small fort there in1757. It was here in 1758 that celebrated French and Indian War leaders Israel Putnam and Robert Rogers took a force of 500 men to screen and scout the French at Fort Ticonderoga. On their return, they were attacked, and Israel Putnam was wounded and taken prisoner.

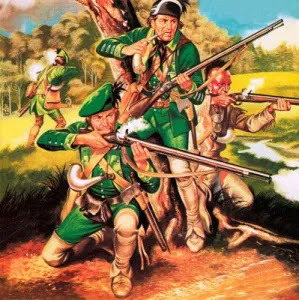

Rogers's Rangers

Rogers's Rangers

Following the fall of Fort Ticonderoga in the summer of 1777, the British General John Burgoyne forced the Continental troops to retreat. They pursued them through the dense, rugged woodlands east of the lakes. The Americans were able to make a fighting withdrawal, felling trees and setting up ambush points, and reconvene in a defensive perimeter near the last defensible position before the defile that led to the lowlands – Fort Ann. The British advance guard was on the move and intent on capturing the fort.

British Advance Guard

British Advance Guard

The Battle of Fort Ann took place here on 9 July 1777. This was another delaying action, one of many, large and small, that characterized the middle phase of the Saratoga Campaign.

Fort Ann Block House

Fort Ann Block House

The British advance guard of some 200 men was met at the gorge about a mile north of Fort Ann by Colonel Pierce Long's rear-guard (150 men) reinforced by 400 New York militia under Colonel Henry van Rennselaer. Long and van Rensselaer attacked in two columns when the British paused to await reinforcements. One swung east and threatened the British flank and rear while the other pushed into the defile.

Gunpowder and War WhoopsThe British withdrew to the high ground, and after two hours of heavy fighting, the Americans broke contact from a lack of ammunition and the sound of approaching British reinforcements. The latter turned out to be a deception – a single British officer mimicking Iroquois war whoops. While a British victory, the action at Fort Ann delayed the progress of the British Saratoga Campaign.

While the Patriots had successfully outnumbered and surrounded the British, they ultimately retreated to Fort Ann and then to Fort Edward when they were deceived into believing that enemy reinforcements were preparing to surround them. Regardless, the Patriots successfully delayed British movements toward Saratoga and ensured an American victory there.

A series of forts were established at the "Great Carrying Place," a portage around the falls on the Hudson, used by local Indians before colonial times. Situated on the "Great War Path," later used by the Iroquois and other tribes, the French and English colonists saw its value and used it during the many wars of the eighteenth century.

Fort Edward and Rogers Island

Fort Edward and Rogers Island

During the French and Indian War, General Phineas Lyman constructed Fort Lyman here in 1755. Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent for Indian Affairs, renamed it Fort Edward in 1756 to honor Prince Edward, a younger brother of the later King George III. After Fort William Henry fell to the French, the famed major Robert Rogers used it as a base for operations conducted by his Rangers. In 1759 General Jeffery Amherst's army assembled at Fort Edward for his attack on Fort Carillon and Fort St. Frederic. After the British took the forts, Fort Edward was significantly reduced as the war moved north.

Sir William Johnson

Sir William Johnson

Fort Edward was razed by the rebels shortly after the Revolutionary War began. It would never serve as a defense work, but the strategic location made it a base for many military officers who passed through. The commander of the Continental Army's Northern Department, General Phillip Schuyler, used it as his headquarters until the British drove him south on their way to Saratoga in the summer of 1777.

General Phillip Schuyler

General Phillip Schuyler

The most infamous event of the 1777 Saratoga campaign, the case of Jane McCrae, took place near the fort. The fiancé (or lover) of a Loyalist officer, Jane was captured by an Indian war party while visiting a house near the fort. Her fiancé sent another Indian war party to parley for her release. When it became clear the fiancé's envoy would not pay a ransom, her captor, a Huron named Wyandott Panther, became enraged. During the argument, he allegedly shot her. Jane's bloody scalp was taken to the British camp, where her fiancé identified it by its stark red hair. The rest of her remains were buried near the fort.

Jane McCrae's tragic death rallied the north

Jane McCrae's tragic death rallied the north

The Americans exploited the incident to arouse innate colonial fear and hatred of the Indians. With the long history of conflict between the tribes (especially the Mohawks) and the settlers, this was pretty easy to achieve. Soon, reluctant farmers and settlers began to rally to the cause in great numbers. By the time General Burgoyne's Army was north of Albany, the angry rebels outnumbered him by two to one.

McCrae's death and fear of the Indians rallied the complacent

McCrae's death and fear of the Indians rallied the complacent

Guns of Ticonderoga

Guns of TiconderogaI will close by recommending anyone interested in the fascinating history of the region visit these locales. They are surrounded by some of the most breathtaking scenery in the United States. Today, the mountains and waterways are home to pleasant villages, picturesque farms, and plenty of activities to enjoy while pondering the bravery and sacrifice of the early Americans, both native and colonists.

May 30, 2022

Bold Dragoon

Bennington, New York (Vermont)

A volley of musket fire suddenly sprayed just over their heads, and, contrary to tradition, training, and inclination, both officers ducked.

His jaw stiff with determination, Friedrich Baum rose to his feet and pointed his saber in the direction of the rebel fire. "The Iroquois must have fled. Why else would we receive rebel fire from there? Move a platoon to the south. Then bring up the cannon and quickly before they overrun us."

"We are already low on ammunition," said Glich.

"Then bring up the last caisson. No sense saving powder now."

Excerpt from The North Spy

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies is another profile of a character from my upcoming novel, The North Spy, Oberstleutnant Friedrich Baum. But because there is so little known of Baum's background, I will have to fill in some blanks with speculation.

Friedrich Baum was commander of a rare commodity in North America, a cavalry regiment. In this case, the Dragoon Regiment Prinz Ludwig, better known as the Brunswick Dragoons. The regiment's name came from its benefactor (the person who raised and equipped it), Prinz Ludwig Ernst, younger brother of Duke Karl, ruler of Brunswick. The Prinz Ludwig regiment was one of seven hired by the King of England from the Duke of Brunswick. The others were infantry: four musketeers, one grenadier, and one jaeger regiment. The Duchy of Brunswick (Braunschweig) is a north German principality that provided a crack professional army to allies like Prussia or friends with hard cash, like Britain.

Prinz Ludwig ErnstA Storied Regiment

Prinz Ludwig ErnstA Storied RegimentThe regiment was raised in 1688 and designated a dragoon regiment in 1772. It consisted of four troops at full strength, totaling 330 officers and other ranks. These imposing horsemen wore bicorne hats and bright blue jackets and carried carbines and sabers. Although they had swords, dragoons were mounted infantry who rode into battle and then dismounted to fight as infantry with light muskets or carbines. It was assumed that the unit would require its mounts while in Canada, but they did not, and later, many exchanged their heavy boots for shoes with black gaiters.

Brunswick Dragoon

Brunswick Dragoon

Typical for the time, the commander was a colonel who did not actually lead the unit – Oberst Friedrich von Riedesel. Instead, the lieutenant colonel (Oberstleutnant) commanded. Von Riedesel would be promoted to major general and given command of the entire Brunswick contingent, which was "leased" to King George to serve as auxiliaries to the British Army during the American Revolutionary War under the treaty of 1776 between Great Britain and the Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.

Vague OriginsFriedrich Baum was born in 1727, but his birthplace is unknown. Little is known of Friedrich Baum's background, but he was a tough, professional officer from the tiny principality ruled by Friedrich Graf zu Schaumburg-Lippe-Bueckeburg. Young Baum rose to captain of the Graf's Carabiner Corps, an elite body of troops. He had fought in some engagements during the Seven Years' War in Europe but had little battlefield command experience before serving in the American Revolution.

Dragoons in the Seven Years' War

Dragoons in the Seven Years' WarA New Allegiance, A New World

Baum switched his service to the Duke of Brunswick in 1762 and, by 1776, had risen to lieutenant colonel. Baum and the Brunswick Dragoon Regiment departed the German duchy in February 1776 as part of two Brunswick divisions hired to fight the United States under the now General Friedrich von Riedesel.

General Friedrich von Riedesel

General Friedrich von RiedeselAfter arriving in Quebec, the Brunswickers helped Governor Guy Carleton police up the Americans struggling to retreat to New York. In the summer of 1777, Baum's regiment was assigned to the army of General John Burgoyne, which was getting ready for a significant campaign in New York's Lake Champlain region.

Northern InvasionThe invasion kicked off in late June and started well with a rapid advance down Lake Champlain, taking the massive Fort Ticonderoga by a coup de main and a pursuit of the rapidly dispersing rebel army. But by August, Burgoyne's forces began to slow and tire in heavily wooded, inhospitable terrain. More urgently, the supply line became overextended, and the army faced shortages. Intelligence reports informed Burgoyne of Loyalists rallying to the king and the availability of livestock and foodstuffs just a few miles away at Bennington in the New Hampshire Grants – a disputed territory straddling New York and New Hampshire that would become Vermont.

The invasion route

The invasion routeA Special Mission

Burgoyne directed Baum to lead 800 men through the Grants, seize cattle and horses, and recruit the numerous Loyalist sympathizers in the region. Baum's men marched east on 11 August 1777. In addition, his more than 374 Brunswick Dragoons, some 50 Jaegers, 30 artillerymen, 300 Loyalists, Canadians, and Indians set off on what was expected to be a simple mission.

Indian allies

Indian allies

True to his Seven Year War experience and European training, Baum proceeded slowly through the rough and wooded terrain. He would occasionally halt the column to dress and realign the ranks. But time was not of the essence as Baum was told. The numerous Loyalists in the region would be rallying to him. Unfortunately, word of the Iroquois depredations against the settlers had the opposite effect. Loyalists did not turn out, but the Patriots were rallying.

Rebel ResistanceThis became obvious the next day when a force of rebels engaged Baum's column in a firefight at Cambridge. His "spider-sense" tingling, the cautious Baum sent Burgoyne a request for reinforcements. He also expressed frustration that Loyalist bands had not rallied to him as expected. What to do? Dig in, of course. He had his men throw up several redoubts east of Bennington and waited for his reinforcements and the situation to develop.

Baum's first contact with militia sent off an alarm

Baum's first contact with militia sent off an alarm

Unfortunately, his redoubts were separated to the point they could not provide mutual support. And although some Loyalists had come into his camp to join his column, there were rebel spies among them. And two American forces were making ready to pounce on Baum's exposed position. The spies soon reported back on details of Baum's defenses. Some 2,000 rebels, mostly New Hampshire militia under John Stark and Seth Warner's Green Mountain Boys, were ready to deploy against Baum's positions. Stark pushed units around Baum's flanks and nearly surrounded him, and on the morning of 16 August, Stark gave the order to attack.

John Stark was the wrong opponent for Baum's first action

John Stark was the wrong opponent for Baum's first action

The veteran Baum was caught off guard by the speed and shock of the rebel attack. The Brunswick Dragoons and other Germans fought back fiercely, expertly using their redoubts. But they fell for a ruse by Stark, who deliberately sent units out to draw the defenders' fire and cause them to waste a scarce powder and ball. When the defenders' volleys began to weaken, the Americans advanced and took the redoubts one at a time.

New Hampshire militia storming Baum's redoubts

New Hampshire militia storming Baum's redoubts

Baum, commanding the last redoubt, assessed his situation. The rebels were swarming and peppering them with constant fire. The air hummed with the sound of musket balls, and the hollering of angry rebels fired up for the final blow. Most of his Loyalist and Indian allies had fled. It was down to him and the dragoons. The professionals who followed him across the deadly battlefields of Europe and a vast ocean now faced a land and a people even more menacing.

One by one, the redoubts fell

One by one, the redoubts fellDesperate Gambit

With ammunition almost depleted, surrounded, and outnumbered three to one, our bold dragoon realized his hopeless position and turned to a desperate measure. His surviving dragoons drew their long sabers. Although they lacked horses, they had gravity! Blades glinting against the sun, the tall, mustached warriors in pale blue charged downhill upon the startled Americans. Seven stout-hearted dragoons slashed their way out and eventually limped into Fort George. Unfortunately, our bold dragoon was not among them. Oberstleutnant Braun took a musket ball, fell into rebel hands, and died in the American camp on 18 August.

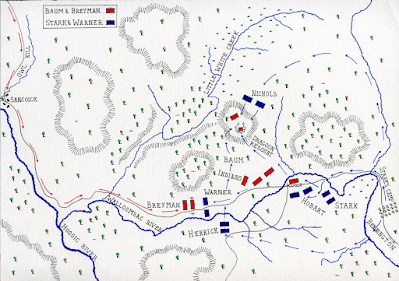

Scheme of battle

Scheme of battleBattle Lost

The final musket shots grew still at dusk. The expected reinforcements, a force of Brunswick jaegers and grenadiers under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann, arrived too late to save the day. Some accounts say Breymann detested Baum and proceeded at a pace of under a mile an hour, but the terrain and other factors might account for this. Breymann himself would fall in battle a few months later - shot by his own men! Yes, "fragging" was a thing in the 18th century and throughout military history.

Campaign LostThe impact of Baum's defeat cannot be overstated. More than 700 soldiers of Baum's command were taken prisoner or missing. Pretty much the whole lot. American casualties were about 70.

Aftermath of battle

Aftermath of battle

The failed expedition meant Burgoyne lacked enough food, supplies, and draft animals for the ongoing struggle at Saratoga – not to mention the lack of a corps of professional soldiers. The Indian allies lost confidence in Burgoyne's chances of success and began to drift away, leaving Burgoyne without native "cavalry" to scout and screen in the vast New York wilderness.

Baum's defeat helped seal Burgoyne's fate

Baum's defeat helped seal Burgoyne's fate

And, of course, Baum's defeat was the precursor to the more significant defeat of Burgoyne's army two months later at Saratoga, turning the tide of war in favor of the Americans.

LegacySo our bold dragoon's legacy is not a good one. Baum's first experience at an independent command became his last. He did his duty, but his mission failed. Yet our bold dragoon gave the last full measure. I believe, in some way, as a professional officer, he may have preferred to give it than face the shame of defeat at the hands of rebels.

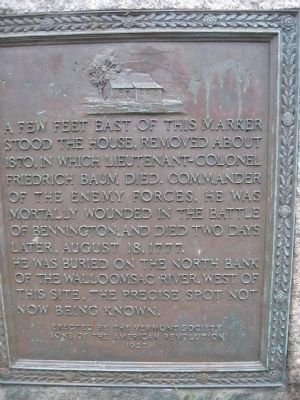

Marker near where Baum died

Marker near where Baum diedThey buried Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum on the north bank of the Walloomsac River, the precise spot unknown. He died in a nearby house, which was razed around 1870. A marker erected at the site of the house in 1927 by the Sons of the American Revolution is the only link to the man whose demise may have meant the beginning of the turning point in the American War for Independence.

Final Epitaph

Final Epitaph

April 30, 2022

The Granite General

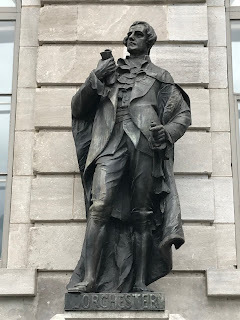

The American War for Independence had a lot of badasses but few senior officers tougher than the Granite State's favorite son, John Stark. Stark was an American cut from the same rough cloth as Anthony Wayne and Daniel Morgan but also had the keen tactical eye of Benedict Arnold and the vision of a Nathanael Greene. Yet John Stark is little known outside his native New Hampshire and even there, primarily for his statue in Manchester.

John Stark statue in Manchester

John Stark statue in Manchester

The son of Scottish immigrants, John Stark, was born on 28 August 1728 in Londonderry, New Hampshire. As a boy, he moved with his family to Derryfield, now called Manchester. It would be Stark's home whenever he was not out hunting or fighting.

Trapping in Deep Forests

Trapping in Deep Forests

In the mid-18th century, much of New Hampshire was a frontier of rugged mountains, dense forests, plenty of game – and native tribes. Stark grew up in this savage wilderness, spending much of his time in the forests hunting, trapping, and developing the skills of a backwoodsman. And he was no stranger to the violence of the region. These would combine to give him the rugged individualism and self-confidence that would later serve him and the nation.

The Hunter or the Hunted?

The Hunter or the Hunted?

On 28 April 1752, a party of Abenaki warriors captured young Stark while he was on an excursion hunting game and trapping fur along the Baker River. One of their party, David Stinson, was killed. Fortunately, Stark was able to warn his brother William, who escaped in a canoe. But the braves took John and his companion, Amos Eastman, to Canada.

Abenaki Hostages

Abenaki Hostages

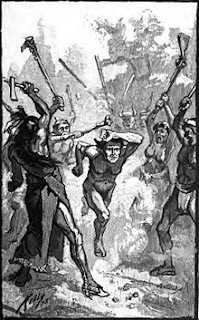

His time as a prisoner toughened him. He and fellow captive Amos were ordered to "run the gauntlet" of braves wielding clubs during their captivity. Few got through the ordeal of the gauntlet without suffering a savage beating, and some succumbed. Stark was not intimidated. Displaying the grit he would later be famous for, the young man sprang on the first warrior, seized his club, and went at the astonished braves.

Running the Gauntlet

Running the Gauntlet

His courage and strength impressed the Abenakis, and the chief adopted Stark, who spent the winter as one of them. The colony later sent representatives to ransom the two captives, with Stark alone setting the treasury back 103 Spanish dollars. Stark returned home but now had a bond with the clan he had lived with.

Let's Go Rangers!In 1755, the simmering conflict over the western frontier exploded in North America. The French and Indian War (Seven Years War in Europe) dragged Stark and his brother William into it. For the British, the war was a fight for empire in North America and worldwide. For the colonials, it was a fight for survival against implacable enemies.

John and William joined Major Robert Rogers's company of rangers. Rogers's Rangers became the most renowned frontier fighting force of its time and the stuff of books and movies. Hardened men, used to the rigors of the frontier, the rangers knew and used every trick in the book to go deep into the forests and wreak havoc on the French and their Indian allies.

Rogers's Rangers

Rogers's Rangers

Young John Stark distinguished himself in the battles at Lake George, Bloody Pond, Halfway Creek, Fort William Henry, the Battle of Snow Shoes, plus the 1758 Battle of Fort Carillion, and the 1759 campaign in which Fort Carillion was abandoned.

In a strange twist, the gritty and hardened Stark faced a unique crisis of conscience in 1759 when British General Jeffery Amherst ordered the rangers to march from Lake George (NY) to the village of St. Francis in Quebec. The town was founded by Jesuit missionaries for converted Indians and was the home of the Abenaki, who had become his foster parents during captivity. Although now a captain and serving as Roger's second in command, the rugged young frontiersman refused to take part in the attack. He soon took leave of the rangers and returned to New Hampshire to spend time with his wife of one year, Molly Page.

Rangers move against St. Francis

Rangers move against St. Francis

When the war ended in 1763, Captain Stark retired and went home to Derryfield to join Molly and raise a family of eleven children. Unlike most of his peers, young John Stark refused to engage in local politics and rejected the call to political meetings, even in the run-up to the American Revolution. However, he overcame his innate rejection of authority when he sensed his country was in danger. In 1774, he joined the local Committee of Safety, the colonies' self-defense organizers and the cornerstone of the resistance to British authority. Local committees of safety prepared the colonies' towns and counties for political action, self-defense, and war.

Committee Meeting

Committee MeetingCall to Arms

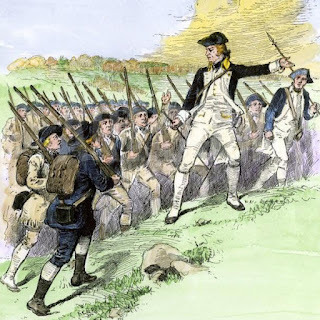

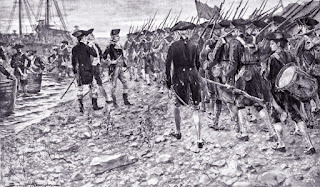

When word of Lexington and Concord reached him, Stark left his farm and sawmill and musket in hand, headed for Boston, where New England was gathering to face the British. Commissioned a colonel, Stark was placed at the head of the regiment he recruited – tough New Hampshire men. He quickly went into action on 27 May 1775, conducting a raid on a British foraging party on Boston harbor's Noodles Island.

Raiding in the Harbor

Raiding in the HarborMystic Beach

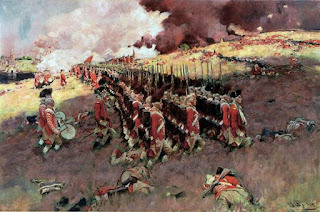

But his real debut came at a place called Bunker (Breed's) Hill on 17 June. Stark's regiment was one of the first to run the gauntlet of British naval fire to seize the critical ground below the crest. Stark now commanded his command plus the Second New Hampshire. The commander on site, Colonel Prescott, told Stark to pick where he wanted his regiments to defend. The former ranger quickly realized the north flank was the weak point of the American position. There, he placed his men behind a rail fence that ran from the hill to the bank of the Mystic River and had them reinforce the rails with straw to deceive the British. He also had the men pile boulders along the exposed beach to form a makeshift wall. Then Stark stepped in front of the works, marked the ground some eighty paces distant, and ordered his men not to fire until the redcoats reached that mark.

Facing the Welch Fusiliers

Facing the Welch FusiliersThe tramp of the advancing elite Welch Fusiliers at the van of the British army had men checking flints as they waited patiently for Stark's command to "aim at their waistbands!" A horrific volley cut down ninety fusiliers, sending the rest in a panicked flight. The next wave fared no better as a second volley blasted them. The final British assault was also repulsed, ending the attack on the American flank.

Bunker Hill: synonymous with Pyrrhic victory

Bunker Hill: synonymous with Pyrrhic victory

Similar results took place on Bunker hill itself until lack of powder forced an American withdrawal, which Starks's men covered with disciplined musket fire. The British took the hill, but with the devastating loss of officers and men. Over 1,000 officers and other ranks were killed or wounded. And so typical of 18th-century war, many wounded would eventually succumb.

Passed OverSadly, many promotions and appointments, especially early in the war, were political. When the post-Bunker Hill round of promotions took place, the Continental Congress overlooked Colonel John Stark for less accomplished officers. This would anger Stark and stoke his resentment toward authority.

Continental LineAfter the battle, Colonel Stark's command was brought into the Continental Army as the 5th New Hampshire Line. The unit served with distinction as part of General George Washington's army in the New York and New Jersey campaigns. Stark's men closely engaged the enemy in several battles, including Trenton, Assenpink Creek (2nd Trenton), and Princeton.

Taking Trenton

Taking TrentonAt Trenton, Washington, recognizing his bravery and abilities as a battle leader, entrusted him with command of the critical right-wing of the Nathanael Greene's advance guard.

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene

In the case of the Assenpink Creek, he famously led a determined and gritty "forward defense" that stalled the British advance on the main army. Stark's actions at Assenpiunk Creek are vividly portrayed in my novel, The Winter Spy.

Stark's defense at Assenpink Creek

Stark's defense at Assenpink Creek

But the headstrong and quick to slight, Stark got his nose out of joint when the Continental Congress promoted Enoch Poor to brigadier general ahead of him. In March 1777, he resigned from the army in a huff, determined to obey neither man nor Congress. But unlike that other famously aggrieved general, Benedict Arnold, Stark's resentment would never turn to treason, only a desire to prove himself.

Stubborn PatriotWhile Stark now simmered at his New Hampshire farm, a new threat emerged in the north – a massive British invasion force under British Major General John Burgoyne. Things in the north were so bleak in the summer of 1777 that the New Hampshire authorities implored him to return to active service in August. He agreed – with the proviso that he held an independent command under no one's control. Then, raising almost 2,000 militia, he took to the field. But true to his independent nature (and stubbornness), he refused a directive from the local commander, General Benjamin Lincoln, and kept his men on the east bank of the Hudson River, separate from the main army in New York.

General Burgoyne

General Burgoyne

Burgoyne's army was moving south, but his supply lines were soon stretched thin. Getting wind of an American supply depot near Bennington, he sent a large force of Germans under the highly experienced Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum east toward what is today Vermont. Getting wind of the move, Stark quickly marched to block the advance. When Seth Warner's 600 men joined him, the combined forces pounced on Baum near Bennington.

Stark's militia would join with Seth Warner's

Stark's militia would join with Seth Warner's

Before the main body commenced its attack, Stark stood before his men as he did at Bunker Hill and exhorted them, "There are the red coats, and they are ours or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow."

Stark leading the attack

Stark leading the attack

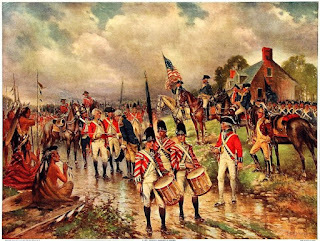

The ensuing battle proved decisive. The American muskets wore down the tired Germans, and soon Stark's men were on the offensive, killing 200 and capturing 700 of the Germans. Baum was among those killed. The victorious Americans suffered just 100 casualties while gaining a tremendous psychological and material victory. John Stark's decisive action at Bennington is an exciting scene in my upcoming novel in the Yankee Doodle Spies series, The North Spy.

Saratoga SunsetIn September, news of the victory rallied more Americans to the ranks – men sorely needed as Burgoyne's final push to Albany collided with General Horatio Gates's army south of Saratoga, New York. After a second clash in October, Burgoyne withdrew around Saratoga as he debated whether to risk another thrust, hold fast, or retreat on his supply line for the winter. When he finally decided to retire, Colonel John Stark had already taken away that option. The Granite General's men swarmed the woods north of the British and cut them off from the safety of Fort Ticonderoga. Burgoyne was forced into a surrender that was the turning point in the struggle.

British troops in captivity

British troops in captivity

In recognition of his distinguished leadership in the campaign that broke the threat from Canada, Congress finally promoted Colonel John Stark to brigadier general. Congress later gave him command of the Northern Department, where he twice assisted General John Sullivan during the Rhode Island campaign of 1778. Ironically, Sullivan was a general promoted over Stark earlier in the war.

Brigadier General Stark

Brigadier General StarkBrigadier General Stark last distinguished himself in combat in June 1780 against General Wilhelm von Knyphausen's Hessians at Springfield, New Jersey. He commanded two New Hampshire regiments that helped check one of the advancing enemy columns. As a result, Knyphausen withdrew, leaving several hundred casualties. This American victory was the last major battle in the north. The British remained holed up in New York City, content to leave major maneuvers the Lord Cornwallis's southern army.

Battle of Springfield

Battle of Springfield

Although not part of major operations during this time, Stark played a role in the most significant espionage case of the war when he was called to serve on the board of generals for the court-martial of British spy Major John Andre. Andre had gone behind American lines in civilian garb to meet the traitor Benedict Arnold. While Arnold escaped, Andre was arrested while trying to return to British lines. Although a sympathetic figure, Andre was nevertheless rightly convicted and received the punishment allotted to spies: death by hanging.

Major John Andre

Major John Andre

Stark finally mustered out of the army in 1783 with a final rank of major general. Since George Washington was a lieutenant general (the army's highest position at the time), Stark had made it to the top tier of serving Continental officers.

Major General Stark

Major General Stark

Unlike so many of his peers, John Stark did not use his wartime patriotism as a platform for political or economic gain. In1809, the state of Vermont asked him to travel to Bennington to speak on the 32nd anniversary of the battle. But Stark was too debilitated from rheumatism to make the journey. Instead, he penned an eloquent letter praising those who served and all who fought, civilian or military, for independence. The old general issued a stern (or perhaps, stark) warning to always be vigilant in the cause of liberty. The stoic general closed his letter in a way only he could, injecting some of his fighting spirit with this warning: "Live free or die—Death is not the worst of evils."

Stark's Monument at Bennington

Stark's Monument at Bennington

Although it should, John Stark's name does not rise to the top when most think of Revolutionary War heroes, even in his native state. Curiously, New Hampshire and Vermont have numerous venues named after Molly Paige Stark, while John has but a handful of monuments. Stark's rousing use of Molly's name before Bennington made his better half more celebrated than him.

Molly Stark statue

Molly Stark statue

John Stark died, the longest living Continental Army general of the war, in Manchester, New Hampshire, on 8 May 1822. John Stark was more than a badass, striking the enemy hard whenever and wherever he could. He lived a life that characterizes ideals held in esteem by all Americans: an independent spirit, rugged individualism, and defiance in the face of unjust authority. These ideals remain the Granite General's legacy.

Stark's grave in Manchester

Stark's grave in Manchester

March 27, 2022

Patriot Sniper

The American War for Independence has numerous iconic warrior-types such as the Minute Men and the Continental Line. Still, the most particular warrior types of the war were those who mastered the Pennsylvania long rifle – the one weapon that struck fear in the hearts of British, Hessians, and their native allies. This edition provides another profile of a character in my upcoming novel, The North Spy. Our American rifleman is famed sniper Timothy Murphy. Although Timothy Murphy receives only a short mention in the book, his role is pivotal.

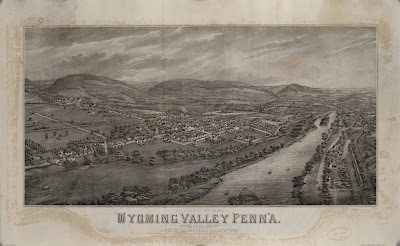

Frontier Youth

Born in 1751 in the Delaware Water Gap region near Minisink, New Jersey, Timothy Murphy was the son of Irish immigrants – most likely hailing from Donegal. His parents moved with eight-year-old Tim to Shamokin Flats, now Sunbury, Pennsylvania, in 1759. Young Murphy apprenticed to a Mr. Van Campen and moved with him to the Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania. The valley was a rugged wilderness region full of hardscrabble backwoods farmers, hunters, trappers, and native tribes. Living among them, the short, dark-haired, but tough Murphy quickly became an expert woodsman and marksman.

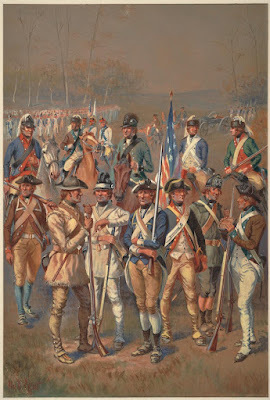

Sometime after the onset of the Revolutionary War, Murphy joined the Pennsylvania Battalion of Riflemen with his brother John and marched to join the main American Army at Boston. As part of this elite band of sharpshooters, he fought at the battles Long Island, Harlem, and White Plains, and he was tested in countless skirmishes in between.

Rifleman of the 1st Penna. Battalion

Rifleman of the 1st Penna. Battalion

Murphy transferred to the 12th Pennsylvania Line, where he was promoted to sergeant. He led his file at the pivotal battles of Trenton and Princeton, gaining particular renown for his shooting and stalking skills. By this time, Murphy was recognized as an expert marksman – able to hit a seven-inch target at 250 yards with his long rifle. Traditional smoothbore muskets could barely hit the mark at less than half that distance.

Murphy served at Trenton

Murphy served at Trenton

In July 1777, Murphy's skills led to his transfer to Colonel Daniel Morgan's Rifle Corps, composed of 500 hand-picked men noted for their marksmanship. Armed with the Pennsylvania long rifle and tomahawk or knife, these riflemen fought from a distance, relying on firepower and avoiding hand-to-hand combat against bayonet-armed regulars. Tim Murphy would emerge as their best sniper.

Daniel Morgan

Daniel MorganWar in the North

With a significant British invasion from Canada threatening the Hudson Valley, Morgan's Rifles were immediately sent to reinforce General Horatio Gates's Northern Department. The rugged hills and thick woods of upper New York were not unlike his home in the Wyoming Valley. Murphy's marksmanship rendered invaluable assistance at the battles of Freeman's Farm and Bemis Heights against British forces commanded by General John Burgoyne.

Morgan's Rifles played a pivotal role at Freeman's Farm

Morgan's Rifles played a pivotal role at Freeman's Farm

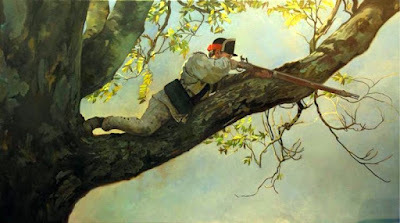

Murphy entered the history books, and American rifleman lore, on 7 October 1777 during the struggle at Bemis Heights. General Benedict Arnold had summoned Dan Morgan to find someone to take out the British officer rallying his troops under the heat of American fire. General Simon Fraser was the best British officer on the field, and Arnold reckoned he was worth a regiment. Morgan tapped Murphy for the grim mission. The area was thick with trees and heavy with smoke so Murphy slung his Dickert rifle on his back and climbed a tree for a better field of fire. Placing his rifle in the fork of a tree, he zeroed in on the general from the extremely long range of 300 yards. Let's pause here to discuss the weapon used by the patriot sniper on that fateful day.

Murphy was tasked with a grim mission at Bemis Heights

Murphy was tasked with a grim mission at Bemis Heights

The Dickert rifle was nicknamed the widow-maker by the British – because of its deadly use against officers. It was also called the long rifle, the American Rifle, the Dickert Rifle, and the Pennsylvania Rifle. But it is curiously and widely known by a designation bestowed considerably later – the Kentucky Rifle. Based on a design by Moravian settler Jakob Dickert, the rifle was some 42 inches long and fired a .50 caliber or larger bullet.

Dickert Rifle

Dickert Rifle