Lucinda Elliot's Blog, page 30

September 19, 2014

Review of ‘The Moon Casts a Spell’ by Rebecca Lochlann

I’ve really been taking a geekish delight in my reading these last couple of weeks particularly, reading out in the garden with a pot of tea, making the most of the last of the warmth before autumn sets in.

I’ve been reading a wonderful fairy tale I hope will be published in the not to distant future by my writing partner. Besides that, I’m re-reading King Lear for a group discussion – I love the attack on tyranny, hypocritical flattery and public displays of false emotion besides the minor matter of the poetry and dramatic tension.

Besides this, Rebecca Lochlann has just brought out her brilliant new novella addition to the ‘Child of the Erinyes’ series out on amazon.

Being hoooked on her amazingly strong writing and the excitement of this series, I rushed to download it, and here’s my review and the link. I recommend it, though I warn potential readers that they’ll almost certainly be hooked too and end up reading the whole series so far instead of doing the dishes, making that appointment with the dentist, tidying up the garden in readiness for winter etc etc.

This novella continues the stirring adventures of the Goddess Athene’s chosen human instruments, the triad of a woman and two men whose fate it is to be born and reborn to shape the course of history.

Readers of the Bronze Age section of this riveting series will know that these three people, the one time Aridela, Queen of Crete, lovely, brave and loyal, the wicked swaggering Chrysaleon, King of Mycanae, and his bastard brother, the tough but tender Menoetius ,are fated to be reborn, to meet, to sense their old connection and to struggle together, until their conflicts are reconciled.

It is the early Victorian era on the barren, remote island of Barra in the outer Hebrides off the coast of Scotland, the time of the infamous clearances where rapacious landlords from the mainland forced whole communities from their homes. Lilith, a servant in the household of the steward to the new landlord of Barra, is secretly engaged to Daniel, a strange boy who her parents took in and raised as one of the family, with whom she has always felt an unaccountable tie. Lilith, a fiercely independent minded girl, has always been thought strange by the other islanders herself.

But when Aodhan McKinnon, the selfish and arrogant but mysterious and intriguing son to the steward comes to the island, she is disturbed to feel a similar bond with him, plus an almost irresistible physical attraction which she knows must be apparent not only to him, but to her scheming, unsentimental mother, who is housekeeper to the household.

In this continuation the author’s characters are as lively, as believable, the writing as strong and evocative and the historical research as impressive as ever. There is a stark tragedy to this story, but also, touches of wry humour; the historical period is invoked effortlessly and the whole complex story of the history of the triad is hinted at, but never thrust on the reader’s attention.

As with the others, I was so caught up in the action that I spent time reading this when I should have been getting on with other things. My only complaint is that as it was a novella, it ended too soon!

September 9, 2014

Combining Popular Taste and Literary Merit

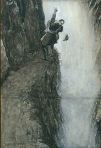

The arrogant Chrysaleon, the anti hero of Rebecca Lochlann’s brilliant series ‘Child of the Erinyes’ is headed for such a fate as this in his defiance of Athene’s curse..

The gifted writer Mari Biella wrote two interesting posts recently about the decline in publishing opportunities for what was once classified as the ‘mid list’ authors and books not easily classifiable.

Here’s the link to the second post:

http://maribiella.wordpress.com/2014/03/14/whatever-happened-to-the-mid-list-part-2/#comment-815

This issue, of course, raises questions about traditional and self publishing that must concern every author.

Here’s the off the top of my head response I posted (ignore the later one where I mixed up Kobo and Smashwords!).

Though I am not as kind as you about traditional publishers – I still think that they don’t deserve to make a profit if they won’t take risks – that being the traditional political economics justification for an entrepreneur’s making money after all – they are only part of the problem as you say.

‘On niche writing particularly, a problem has always been unfortunately that the majority of readers have frankly tacky taste – romantic fantasies for women and He Man Action stuff for men. Escapism always seems to have been the essence of it.

‘As you know, I have been exploring the appalling works of that Victorian best seller of sloppy trash Charles Garvice, who aimed to please a ‘newly literate’ class of readership, servant girls and nursemaids, etc,(though I believe during World War One ordinary soldiers in the trenches started to read his stuff, too). It’s a sorry comment on the continuing sexism and violence of our society that these tastes still should go on today.

There was a time in the eighties (here I go: ‘In my young days we…’) when educated women didn’t admit to reading romance, but now its made a great resurgence, the only difference being it’s more sexually explicit. It can sell very well on Amazon, and in catering to this less than elevated taste, an unknown can make writing profitable. I know intelligent, witty, feminist thinking women writers who write far beneath the level to which they could aspire and never venture outside their chosen genre – because they want their writing to be profitable, and the chances of doing that through producing something outside mainstream taste are dismally slim.

I don’t want to give the impression that I’m in any way condemning authors for making these choices (though for me any author who panders to regressive rape fantasies is another thing entirely!) Nevertheless it is a shame that the need to conform to public demand reduces these writers’ choice of subject matter, style, portrayal of character, etc.

As far back as 1833 Aleksandr Pushkin saw the problems of the two trends in literature – popular taste and literary merit, and tried to combine popular appeal, with a stirring, romantic storyline with literary merit in ‘Dubrovsky’. (There I go again; I’ll be on to Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ next). I thought he did a good job of it, but I’ve only been able to find one piece of literary criticism on it, and the opinion of that author on the romantic aspect of that robber novel was scathing. Combining the two SEEMS to be the obvious solution, but is very difficult.’

This is, of course, only one aspect of a complex problem, but one by which I am particularly fascinated and on which I have posted before (Regular readers can hardly fail to have noticed that I’ve posted a lot on Pushkin’s attempt to combine the popular and a work of literary merit in his robber novel ‘Dubrovsky’, one of my favourite novellas, too!).

Writing work which hopefully has some literary merit but which has a popular appeal remains my ambition. Many insist that you can’t combine the two. I don’t see why; maybe I’m being obtuse (waves long ears and says ‘Hee Haw!’) but I don’t see why this is presupposed at all.

There does seem to be a certain distaste for genre fiction amongst readers and writers of literary fiction – it’s seen as rather tacky, somehow, indicative of bad taste, like preferring tinned peaches to the real thing, say, or being shameless enough to say you think some distorted Hollywood version of a classic work far better than the original.

This attitude may be changing, and I hope it is. I admit at once that I haven’t had the time I’d like to have to read up on much recent discussion of the matter on the web.

I have been looking for serious (in so far as I can be serious about anything!) discussion of the feminist issues in historical romance, particularly the most famous authors, ie, Georgette Heyer and Barbara Cartland, and that is quite thin on the ground. I haven’t been able to find any books specifically dealing with it, though I even started a thread on Goodreads asking for recommendations (I still haven’t got any). Germaine Greer’s ‘The Female Eunuch’ does touch upon the matter in one chapter, and her acid ridicule of a couple of Cartland and Heyer’s heroines still outrages historical romance lovers today – but that was four decades ago.

I have heard it claimed that in genre fiction, the plot is everything: in literary fiction style is predominate.

To suggest that they are mutually exclusive seems to me mistaken.

After all, wasn’t there a certain playwright of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (they didn’t have novels then) who made quite a thing out of combining popular taste and literary merit?

Shakespeare had to ‘write for the market’. He was in it to make money as well as, no doubt, a desire to write good plays. I don’t think many people would argue that this generally affected the merit of his work.

For sure, he was a genius: but while we almost certainly won’t be able to come near his stature as a writer, that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t do our level best.

I know of a number of talented women writers who limit their style to that of popular romance. This isn’t because they have limited imaginations, are uncritical of the relations between men and women in our current society, lack wit, or are incapable of appreciating good literature or writing it themselves.

I want to make it clear that I am not attacking these writers, or anyone, (except pedlars of rape fantasies) for writing for the market .

What I am saying is that it is a shame that many writers give up on the idea of experimentation because it is so difficult to escape what might be called the Genre Trap.

They write genre fiction which tends not to experimental in tone because they want to be successful writers and to make a profit out of writing. In this era, escapist fantasies of various sorts seem to be particularly popular.

There seems to be something about the current decade which encourages escapism – it’s rather as if people have lost faith in the ability of ordinary people to change unpleasant things about our current society, or as if in an atmosphere of economic uncertainty people have lowered their eagerness to experiment and opt for adventure in real life.

Continuing sex role differentiation has led to women going on, or going back, to reading romantic fantasies and men reading adventure ones (though it’s worth noting that some modern fiction seeks to combine the two for women more than has been the case in the past).

This reading matter being largely escapism, the question is, is it impossible to combine it with literary merit?

Again, why is this so often assumed to be the case?

Think about Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ or Emily Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ (for all it’s faults, undeniably a brilliant work). These classic novels were both written as Gothic entertainment (with a serious underlying purpose).

I have quoted before the scathing remarks by Paul Debreczeny in ‘The Other Pushkin’ on Aleksandr Pushkin’s attempt to combine adventure and romance with fine writing in his robber novella ‘Dubrovsky’.

In this project, Pushkin encountered problems that all ‘serious’ (or comically serious) writers who aspire to produce well written genre material must encounter.

The critic points out, for instance, that while young Dubrovsky is at first introduced with the same ironic distancing used with regard to his father and the tyrannical landlord Trokurov, soon this is abandoned and what follows is ‘the unhumorous stock-in-trade of romantic literature’. The romantic scenes between Dubrovsky and his love interest Maria are ‘thrown in with the utmost crudity’ (of writing style, that is, lol, not sexual explicitness depicted vulgarly: poor Dubrovsky gets no closer to Maria than kissing her hand).

Then, Debreczeny complains that while combining ‘a serious novel of social protest’ with a robber theme could be done, Pushkin fails to make the connections.

That it was rather difficult to write a ‘social protest novel’ that could bypass the censorship of Tsar Nicholas’ notorious Third Section is an additional complication not, thankfully, suffered by most modern authors in the US and Europe and which Debreczeny perhaps might have taken more into account; the criticism about an increasing lack of humour in the depiction of the love affair between the young brigand and his enemy’s daughter is valid.

Pushkin was clearly aware of the difficulties of his project and while he could have largely removed these by revising the work, instead he seems to have lost his faith in his ability to resolve the contradictions and with numerous excuses, abandoned it never to return to it.

This was a pity, as a successful attempt to combine a novel appealing to popular taste and literary merit was lost. Even unfinished as it is, I find it an excellent read which does, even in translation, combine the excitement of popular appeal (it’s a robber novel with a romantic theme) with literary merit.

A lack of ironic distance, of humorous observation, is often a fault of romantic stories generally and I think a quite unnecessary one. Pushkin, unused to writing romantic fiction, fell into the typical style of an uncritical presentation of the handsome, dashing, wronged hero, and it does detract from the style of the later chapters of ‘Dubrovsky’.

This was surely unnecessary; a certain measure of ironic distance from the author needn’t ruin the emotional strength of romantic episodes.

There have been some recent attempts made to bridge the gap between work of the standard of literary fiction and genre fiction, and one excellent example is the brilliant self published author Rebecca Lochlann in her series ‘The Child of the Erinyes’: ‘The Year God’s Daugher’ ‘The Thinara King’ and ‘In the Mood of Asterion’.

I’ve been completely drawn in to this series, combining as it does the level of research of Mary Renault with a feminist interpretation of history. They are exciting, thought-provoking, expertly written page turners. I can never put them down.

Here’s the link, and I envy you starting on this treat:

http://rebeccalochlann.wordpress.com

August 18, 2014

A Short Rant About A Rapist Hero and Some Musings on Characters’ Appearances

A while ago I was kept waiting for an hour in a doctor’s surgery, and started leafing through a pre World War Two historical romance someone had left on the table.

A while ago I was kept waiting for an hour in a doctor’s surgery, and started leafing through a pre World War Two historical romance someone had left on the table.

Soon, I felt as if steam was about to burst from my ears. This would seem to have been the author’s intention, but in my case, it wasn’t because of the hero’s cynical, world-weary, supercilious look – rendered all the more telling by his heavy eyelids and ‘Devil’s eyebrows’ (I assume by this the author meant ones that taper upwards at the corners) – but because he was a rapist jerk. Not content with half throttling the heroine at one point, he also threatens to rape her on another two occasions. Despite this, she is happy to marry him at the end, though I couldn’t find so much as an apology from him for his little lapses in taste, save the implication that he usually saved such behaviour for ‘women of easy virtue’…

To be fair to this author, this book was written before World War 2, and even up to the nineteen-seventies the attitude towards rape was much more lenient than it generally is today, with the view taken that ‘it’s only a man’s nature, they can’t help it..

I’ll rant elsewhere about how disturbing it is that women should still be reading such romances and admitting to ‘rape fantasies’. Here, I wanted to comment on how I suspected the author felt obliged to stress this abuser’s physical assets because he was somewhat lacking in any other charm – was obliged to do so really, so that the harping on his appearance became dull rather than intriguing.

This leads me on to reflect on how difficult it is to strike a balance between boring the reader with too explicit descriptions of characters and frustrating her with not enough.

I do yawn through books which aren’t intended to be erotica but which have the hero’s ‘rippling torso’ stressed at every other page – fair enough, when he’s taking his shirt off, or if some aspect of the plot makes it necessary to stress that feature – but otherwise…

I remember reading another historical romance (I blame these doctor’s surgeries and periods of being snowed in when a youngster) where the heroine’s golden hair was mentioned several hundred times in the text.

Interestingly, classic writers are more sparing in their descriptions of their characters’ physical appearances. Jane Austen, that model of conciseness, gives us only the vaguest notion of Elizabeth Bennet’s looks.

We know that Darcy on first seeing her was ungallant enough to say that she is ‘tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me…I am in no mood to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men’ (Elizabeth has to sit out a dance). Ouch. No wonder she detests him for so long.

In the second half of the novel, Miss Bingley has a jealous outburst about Elizabeth’s appearance, during which she jeers at her ‘too thin’ face, her ‘sharp shrewish’ eyes and interestingly, uses the word ‘tolerable’ herself about her teeth, and sneers at the lack of ‘brilliance’ in her complexion (in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, a high colour was considered indispensable for either men or women, hence the rouging). She has already jeered at the sun tan Elizabeth has got traveling n the summer, so that ironically, through her spite, we end up with a more minute description of how Elizabeth looks than we otherwise would.

It seems to be Elizabeth’s misfortune to have her looks picked to pieces; earlier, Mr Darcy,now outraged at the attack on his idol, did just the same when he was eager to point out to his friends at Netherfield that she had no good features at all.

It’s a commonplace that Richardson was a great influence on Jane Austen and her concise novels are the greatest contrast to his wordy volumes. Therefore, it’s an irony that in fact Richardson’ doesn’t describe any of his characters save for an aside here and there .

We know that Clarissa is fair, and looks healthy until her decline (despite hardly eating) and we know that Lovelace has that much admired high colour and is tall above average. As he is an expert swordsman and survives nights spent pacing out in the frost covered grounds, scribbling love letters beneath his dripping periwig , we may assume he is very fit, but we know nothing of his hair and eye colour, or his features, and as he is meant to be outstandingly handsome, this does tease the reader.

This, if intentional, was a clever move on Richardson’s part. A character who has any element of mystery attached to him or her is the more intriguing.

In another, less well-known classic, ‘Sylvia’s Lovers) (here I go again, I know) we have the three main characters described in some detail. Sylvia Robson has chestnut hair and great grey eyes, a high colour until her heart is broken, when, rather like Clarissa, she becomes pale, and is fairly slim (by Victorian standards, that is, which wouldn’t be ours) and vigorous (I always maintain that if only she could have gone to sea herself, it would have suited her admirably and solved her problems).

Philip Hepburn and Charley Kinraid, the two rival lovers, are oddly like two halves of the same incomplete character, both physically and mentally, This is reflected in the fact that both are tall and dark, but while Philip Hepburn is drooping and out of condition, Kinraid is stalwart and athletic, Hepburn has drooping hair to match his character while the flashy sailor Kinraid’s curly hair is in ringlets, the one has a long, sad face with a long upper lip, the other a short, broad one with a sun tan, etc.

But, frustratingly, we never hear what the heiress the ‘fause’ Kinraid marries so soon after his dramatic parting with Sylvia looks like, merely that she is ‘very pretty’ and oddly, is described as a ‘joyous little bird of a woman’ (does this mean flashy plumage?). Whether Mrs Gaskell, who surprisingly, rarely edited her work and finished this novel in a rush, intended to go back and fill in this detail, we don’t know, but the whole effect makes one want to know more about this sup[erficail heiress..

So, I really have no idea which is the best approach and try to aim for somewhere in the middle, myself (I may not succeed and I may have emphasized once too often that Aleks Sager has Pushkin’s wildly curly hair and piercing light blue eyes, or that Sophie is blonde and has a full hour glass figure, with a large bottom).

Like the issue of descriptions of places, those regarding physical descriptions of characters is complex. Everyone sees the same person differently, for instance, a fact that some writers seem at times to overlook. People can look strikingly different at different times depending on state of mind and health, etc – Mrs Gaskell is very good at depicting this and Jane Austen nearly as good – Richardson again provokingly vague.

Ah, an unknown visitor with drooping supercillious eyelids has just knocked at the door, hoping to sell life insurance specifically aimed at women. I could swear I’ve come across him somewhere before…

August 9, 2014

Moral Complexities and Good and Bad Characters

Francis Franklin’s intriguing and disturbing book ’’’Suzy and the Monsters’, which is about a predatory lesbian vampire who routinely abuses women, and her war on a far worse group of abusers, human traffickers, examines the moral complexities in this vendetta where Suzy displays ‘the rage of Artemis’. No punches are pulled in describing Suzy’s own awareness of her particular capacity for cruelty, or that of her hateful opponents.

Francis Franklin’s intriguing and disturbing book ’’’Suzy and the Monsters’, which is about a predatory lesbian vampire who routinely abuses women, and her war on a far worse group of abusers, human traffickers, examines the moral complexities in this vendetta where Suzy displays ‘the rage of Artemis’. No punches are pulled in describing Suzy’s own awareness of her particular capacity for cruelty, or that of her hateful opponents.

This contrasted strikingly with the book I was previously reading where the moral boundaries between good and bad people are generally clearly if simplistically, drawn and where notions of good and evil, abuse and abuser are clear-cut – that is in Samuel Richardson’s ‘Clarissa’.

As I don’ t myself share Richardson’s orthodox religious views, with hellfire and damnation awaiting the wicked and eternal bliss for the virtuous, or his system of morality, it might be seem surprising that I agree with his definition of Lovelace as a wicked man. However, I do, because he is a rapist., and not only that, but a serial abuser of women who thinks that their moral worth can be equated with their so-called physical virtue.

Richardson, it seems, took the view that if the repentant Belford and the incorrigibly scheming and immoral Lovelace had not been ostensibly believers, then their correspondence would have been ‘truly demonic’.

I’m far from believing this myself – it seems to me that Lovelace’s hypocritical refusal to listen to blasphemy, whist showing no mercy to so many of his fellow creatures makes him seem far worse. He also comes across as a fool, for if he believes in damnation but works diligently for his admission to hell, he seems to me almost to suffer from some mental condition in which the sufferer can’t relate cause and effect.

Another writer whose attitude towards moral conflict is within the straightforward one of Christian morality is Elizabeth Gaskell. As such, one would rather expect her moral scheme to include a scenario where the wicked flourish in this world and the good and morally scrupulous lose out, looking forward to a reward in the next.

Sometimes in her stories, as in various short stories, for instance, ‘The Sexton’s Hero’ and ‘Half a Lifetime Ago’ this is clearly her thinking on this point, but in various of her novels she seems to be distracted by the conventional novelists’ need for a happy ending in this world, regardless of theology; for instance, in ‘North and South’ the happy reconciliation of the hero and heroine seems contrived to say the least, and comes about through a whole series of people conveniently dying or changing their accustomed patterns of behaviour.

In ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ as I have often said before in this blog, the author gets into difficulties of another sort, caused through her softness towards a morally questionable main character. She ends up by having two out of three very faulty characters suffer a dismal fate in this world, while the third seems to have an improbably charmed life.

The dishonest Philip Hepburn, who conceals from his idol Sylvia Robson that he knows that her preferred admirer Charley Kinraid has been taken by a press gang rather than having been drowned, suffers a miserable fate (and it is hard not to believe, deservedly). Rejected by Sylvia in front of the returned Kinraid, he goes to expiate his sins by enlisting as a marine. Horribly disfigured in an explosion, he comes home a beggar and finally dies dramatically in the arms of a repentant Sylvia, whose punishment as surely follows; tormented by guilt at her godless rejection of the man she married, she drags on a few more years before dying early herself.

Meanwhile, the thoughtless womanizer Charley Kinrad (who is blamed by Hepburn’s business partner William Coulson for causing the death through a broken heart of Coulson’s sister Annie, and who has beguiled his cousin Bessy into believing that she is engaged to him at the same time that he is courting Sylvia) makes a brilliant match with a pretty heiress only months after he finds out that he has come back to find Sylvia married.

Not only that, but he has a glowing career in the Royal Navy open to him.

In the gun battle on his whaler through which he becomes Sylvia’s hero, he has shot dead two press-gang members, and it is only through being shot down and mistaken for dead himself that he escapes what would have been his punishment had it been known he had survived – hanging for mutiny.

This opposition to press gangs doesn’t prevent him from going in for heroics – this time on the Royal Navy’s side – when he is later captured by a press-gang. This is turn leads to his promotion to officer rank, and after some more heroics being promoted again to Captain.

As an officer, this opportunist would be expected to use press gangs routinely to get enough men (never mind the regulations governing impressments) but we don’t hear about this sordid side to his glittering career as a Naval hero and we may assume that he and the woman who has replaced the unlucky Sylvia in his gadfly affections go on from strength to strength.

As I have also said elsewhere, I think this strange contrast between the dismal fates of two of the three main characters in this novel, and the improbable luck of the third, is very likely due to Elizabeth Gaskell’s identifying all her sailor characters with her beloved lost brother John . The theme of the Returning Sailor is one of the landmarks of her work, and while she probably planned a less glowing fate for the caddish Charley Kinraid, sisterly affection must have taken over from authorial detachment.

Of course, I may be wrong. Elizabeth Gaskell was as frequently as subtle a writer as she could be one given to melodrama and even sentimentality, and it is possible that Kinraid’s good luck (the whaler on which we first encounter him is called the ‘Good Fortune’) is intended as a lesson on how the emotionally superficial and unscrupulous flourish in this world. One of the reasons this novel is one that I find particularly intriguing is because the moral lessons are far from as clear-cut as perhaps Elizabeth Gaskell intended them to be. Some people, for instance, read this and assume that Kinraid is meant to be regarded uncritically as a hero – but given the author was he devout wife of a minister I find this hard to believe.

This unintentional ambiguity in the moral message of this novel, where two characters are punished for their wrong doings in this world and another comes up smelling of roses, makes me less amazed at the absurd amount of time that Richardson devoted to writing appendices and footnotes to his works – and to ‘Clarissa’ in particular – explaining to his readers exactly what moral point he wished to make, exactly how he was trying to portray a character.

But from Richardson’s day to ours, unfortunately, there are those who continue to admire Lovelace and despise Clarissa. Whatever our spiritual beliefs, whatever point, moral or otherwise, we may wish to make in telling our story and portraying our characters in a certain way, once we publish the reader is free to make up her own mind.

July 27, 2014

Strong or Sentimental Writing

Surprisingly, a couple of years ago a teenager asked me to recommend some ‘strong writing’ (She even read them too, but that’s irrelevant here).

Surprisingly, a couple of years ago a teenager asked me to recommend some ‘strong writing’ (She even read them too, but that’s irrelevant here).

I assumed she meant writing that grips, and doesn’t pull punches, because come to think of it, I wasn’t quite sure what is meant by ‘strong writing’ – like intelligence, I only recognize it when I come across it.

I recommended two classics – ‘The Heart of Darkness’ by Joseph Conrad and the long short stories by Laurens Van Der Post collected under the title ’The Seed and the Sower (probably better known as the film ‘Merry Christmas Mr Laurens’).

Then, I realized that I had been guilty of unconsciously going along with sexist groupings as I hadn’t recommended a women writer, and red-faced I added that by way of gothic melodrama with a truly foul male protagonist, ‘Wuthering Heights’is brilliantly done for all its flaws. Then, there’s Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’.

But it’s interesting – while there are some books that maintain strong writing throughout, most books rise to it now and then,even ones that are sentimental in tone, promoting an ‘All’s Right in a Pretty World’ (at least for the Important Characters in this, anyway, and that’s all that matters really) approach.

I have even found this to be true in places in the writing of that most sentimental and embarrassingly emotional of all writers, the late Victorian and Edwardian novelist Charles Garvice.

Here we are with a paragraph where he stops telling us that his hero Lord Fayne has admirable traits, and just shows them.

This protagonist, a wild young Viscount who has gone to bad, and devotes his time assiduously to causing disgrace to his stately family dressing as a costermonger, squandering the fortune he inherited from a relative by getting hammered and brawling in music halls., is meant to have many sterling traits nevertheless, including a native sense of honour and a disgust with petty minded spite and cowardice or underhand behaviour in general. This will all make him, of course, a perfect future Earl once he stops dressing as a member of the lower orders and associating with shameless floozies at the Frivolity Music Hall.

Here he hears that the woman he worships from afar (not, of course, one who would set foot in a music hall) is engaged to his cousin and rival, who is called the wonderful name of Marshbank, which sums up his slippery nature -

‘”Yes,” he said, “He is a favourite of fortune. He has stepped into my place., he has got my father’s goodwill –that’s all right enough. And now he has won you! Oh yes, it’s all right! I’m paying the penalty; I’m reaping the harvest that I have sown. But oh God! It’s hard to hear.”

Despite the melodramatic language, I found that there was something moving about this, though I remained unmoved through pages of purple prose depicting this character’s desperate love of his Eva, his reformation and the opening of his heart to the ways of the simple country folk amongst whom he wanders as a sort of nineteenth century minstrel or busker, his tenderness to a little girl etc etc.

By contrast, here we have Lord Fayne declaring his love for Eva: -

‘”Forgive me, forgive me!” He whispered, brokenly, hoarsely. “I did not know what I was doing. I –“ he stopped, his dark eyes fixed on her imploringly., as a man pleading for his life might look. If she had met his eyes with a cold, angry stare, all might have been well; but there was something in her gazed which seemed to woo his next words, to draw them out of his heart.: “I love you!”.

Eva drew a long breath, and sat like a statue…He stood looking at her in awe and fear..They neared Endell Square, then he spoke. “I will not ask you to forgive me (I thought he already had) he said, hoarsely, ‘I do not deserve it. What can I say? Only this; that – that you shall not see me again…”

Then it seems he changes his mind about this, too, for, “…Perhaps – perhaps some day, if I win the fight,; if I am less unworthy to be near you, I may come – to ask your forgiveness for – for – what I have said today…”

Yes, well…Lord Fayne rides off to be a Better Man, leaving Eva in a dream of virginal shock and romance: – “…Was it real, or only a dream? The world seemed slipping away from under her feet.”’

Then again, Mrs Humphrey Ward in ‘Marcella’ (an anti socialist tract on how women shouldn’t meddle in politics) is unsparing in some of her details of the suffering of a wretched poacher’s family in a Buckinghamshire village. For instance:-

‘The cottage was thick with smoke. The chimney only drew when the door was left open. But the wind today was so bitter that mother and children preferred the smoke to the draught. Marcella soon made out the poor little bronchitic boy, sitting coughing by the fire….”Hmm! Give him two months or thereabouts,’ thought Wharton. ‘What a beastly hole! –on e room up, and one down, like the other, only a shade larger. Damp, insanitary, cold – bad water, bad drainage, I’ll be bound – bad everything…’

This is excellently and effortlessly done. But sentimentality will out in Mrs Humphrey Ward. This liberal politician and rival for the rebellious Marcella’s hand to the sterling Tory candidate Mr Aldous Raeburn reveals himself to be a cad by stealing a kiss from Marcella and engaging in financial chicanery over his newspaper, and all ends as it should: -

‘’Forgive?’ he (Aldous Raeburn) said to her, scorning her for the first and only time n their history. “Does a man forgive the hand that sets him free, the voice that recreates him? Choose some better word – my wife!”

Advice I would someone had given to the author about the whole paragraph. Meanwhile, in line with the sentimental tone of the novel, Henry Wharton (no relative of Harry Wharton, I assume) is obliged to marry a woman shockingly, ten years older than himself, and notoriously cruel to her servants, to recoup his finances…

I think that these brief extracts from a couple of late Victorian is fascinating evidence that even writers who choose to go in for melodrama and to pander to superficial emotions can write strongly enough when they choose – they just choose not to.

July 9, 2014

A Despised Classic

It is interesting that authors who produce a remarkable work can regard it as of no particular importance and value something else.

It is interesting that authors who produce a remarkable work can regard it as of no particular importance and value something else.

The classic case of this if, of course, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and his view that the Sherlock Holmes stories were work ‘of a low order’ which, not being morally improving, had none of the merit of his historical and other works.

After the sensational success of the Holmes stories, that author gave up his occulist’s room in Wimpole Street and ‘Settled down to do some literary work worthy of the name’. ‘It did not take me long to write ‘The Refugees’.

Yet, the author remarks rather sourly, ‘It was still the Sherlock Holmes stories for which the public clamoured, and these from time to time I endeavoured to supply. At last, after two series of them, I saw that I was in danger of having my hand forced and being identified with what I regarded as a lower stratum of literary achievement. Therefore, as a sign of my resolution, I decided to end the life of my hero…’

So, Conan Doyle created the Napolean of crime, Dr Moriarty, and had Sherlock Holmes plunge to his death with him over the Reichenbach Falls, locked in an unrelenting embrace.

‘I was amazed at the concern expressed by the public…I heard of many who wept. I fear I was utterly callous myself.’

Conan Doyle ignored the pleas of his reading public for twenty years, but in the end, brought Holmes back from the grave in ‘The Adventure of the Empty House’ which features as the first story in the collection, ‘The Return of Sherlock Holmes’.

I have to admit that when younger I never got round to doing more than glancing through the works that Conan Doyle considered of greater literary value than his Sherlock Holmes stories – I believe, ‘The White Company’ was one of these – and now they are hard to get hold of.

I did, however, read a book which was one of the many my mother got accidentally as job lots in auctions – ‘A Duet with Chorus’, which recounts the experiences of a newly married couple.

Needless to say, no Naughty Naughty Tut Tut stuff forms part of these experiences. It is all highly proper and suitably moralistic. Even the story featuring the wife going into labour and her trick to spare her husband’s feelings by sending him off on a jaunt for the day – so that he finds on his return with a new-born baby and a newly installed nurse – is told very politely.

The same is true of a visit from a – horrors – resentful former mistress who plots to spoil the couple’s happiness. She is won over by the bride’s innocent sweetness, and leaves, without stating the purpose of her visit, but not before giving a speech on the horrors that follow on from the loss of a woman’s reputation, accompanied by some tears.

I don’t know what Conan Doyle thought of the literary merit of this collection of stories. I have glanced through a couple of biographies of the author and they never seem to bother mentioning this book. I found it of considerably less interest than the Holmes stories, and only intriguing form the point of view of casting yet another light on the difficult and frustrating roles that wives were expected to perform in the Victorian age as a ‘domestic angel’.

However, I enjoyed the Professor Challanger stories – I’m sure Conan Doyle regarded them as of the lowest order – especially ‘The Lost World’. Like countless other people, though, I’m a Sherlock Holmes addict. I’ve read the stories three times over, watched all the television series, visited the Sherlock Holmes museum in Baker Street, and never cease to revel in the atmosphere.

Conan Doyle had a genius, in the Sherlock Holmes tales especially, to tell a good yarn. He could draw you in and keep you engrossed. He could sum up atmosphere in a few terse words, for instance, this, from one of my favourites, ‘The Speckled Band’: -

‘How shall I ever forget that dreadful vigil?…The shutters cut of the least ray of light, and we waited in absolute darkness. From outside came the occasional cry of a night-bird, and once at our very window, a long drawn, cat-like whine, which told us that the cheetah was indeed at liberty. Far away we could hear the deep tones of the parish clock, which boomed out every quarter of an hour…’

Conan Doyle would have been highly dismayed to discover that his other works are largely unknown, while the despised Sherlock Holmes stories remain world-famous to this day, with some people from abroad even believing that the great detective actually existed in Victorian London. He couldn’t accept that in writing of his despised Sherlock Holmes he had created the famous classic he always sought to create in those works he considered to be of so much more literary worth.

This makes me wonder how many other writers have created classics which they despised? I know that Enid Nesbit wrote stories for adults as well as for children, yet it is for her children’s magical stories – ‘Five Children and It’ and others, that she is famous.

Louisa M Allcott – an early feminist – created the somewhat morbid story of self-abnegation in ‘Little Women’ with its tomboy heroine Jo, and it’s sequels.

It is less well-known that she wrote lurid and melodramatic stories with almost gothic overtones. I read one, the name of which I have forgotten, but I do know that it was a wonderfully over-the-top read of purple prose.

The female protagonist is a femme fatale of mediocre physical attributes but great charm, who pretends to be ten years younger than her age. With the help of slot-in false teeth and a wig, she steals the fiance of the daughter of the house. Safely married to him, she stands at the end of the novel, daring the family to do their worst.

I found this a far more compelling read than the dismal taming of the fiery Jo that features in ‘Little Woman’ and rather regret that if this tale is typical, it isn’t these adult novels which became classics.

June 30, 2014

To Write from the First, Third or even, the Second Person Point of View?

I’ve posted before on the whole issue of how much of a character’s thoughts, feelings, and general inner life to reveal in a book – is it more intriguing to have one laid bare – or one who retains an element of mystery?

I’ve posted before on the whole issue of how much of a character’s thoughts, feelings, and general inner life to reveal in a book – is it more intriguing to have one laid bare – or one who retains an element of mystery?

However much of the character one chooses to reveal is all, of course, inextricably bound up with the point of view the author chooses to use – third person, first person, the rare second person – or even some variant.

I wrote the first draft of ‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’ in two first person’s – Sophie and Emile’s – and it was only because I was intrigued by the idea of having Emile only seen from the outside – and therefore, remaining to some extent throughout, and particularly during his monster stage, inscrutable – that I finally went over to the third person point of view. He had to be seen by other people throughout, Sophie, Lord Ynyr, Georges, etc.

Previously, I did enjoy portraying events from that scoundrel’s light hearted, rascally viewpoint; I was reminded of that when I recently read the letters of the villain Lovelace in Samuel Richardson’s ‘Clarissa’. I recalled how intriguing it was to use that particular version of the first person also, when I read an excellent YA book in the spring, Kate Haney’s ‘Someone Different’, strongly written from the point of view of the two main characters.

This inspired me to go back to it in the novel I haven’t been long at work on – called tentatively, ‘The Villainous Viscount or The Victims’ a return to a Gothic theme.

The main male character in this is an anti hero for sure – the complicated villain I have recently become interested in portraying.

I did read somewhere – and typically forgot where – that a recipe for failure is writing about an unsympathetic character in the first person. Mind you, according to some ‘How To’ books on writing, any sort of innovation is a guarantee of failure. I’ve read some works where the author has used this technique, though, and think it has a lot going for it (she said arrogantly, facing the prospect of disastrous sales). The lame self-justification, the insensetivities of a wicked character can make for intriguing or grimly amusing reading, and a lively, charming wicked character who must nevertheless be seen as too bad to be capable of reformation (unlike my previous lovable rogues Emile and Reynaud) is a real challenge.

I hope I’m not speaking too soon about this intriguing project. Trust me to do that. I’ve had a few weeks of the dreaded writer’s block, of starting projects that foundered, and churning out those Early Morning Tea Four Hundred Words in longhand only to look at them later with disgust – ‘What made me think that was any good?!’

I remember how in an excellent ‘How To’ book on writing, James N Frey’s ‘How to Write a Damn Good Novel’ he points out that it isn’t necessary to use the first person to get inside a character’s head.

Instructively, he quotes one of the earliest Stephen King novels as evidence, rewriting a scene from Carrie’s first person as distinct form third person point of view, and it isn’t any more telling. I wish I had the book to hand as this is impressive evidence of Stephen King’s skill. For all that, it is easier, somehow, to take on the mood, the persona, the language of a character when you actively get into his or her viewpoint.

The first person point of view can also make for particularly lively reading; I am sure I must have said a good few times before how much I dislike that arch patriarch, the matriarchy destroying Theseus, in Mary Renault’s book ‘The King Must Die; – but he is, if obnoxious to me, the liveliest of narrators, until taken over by premature aging and bitterness in ‘The Bull from the Sea’,when he becomes a bore. For instance: -

‘I met no monsters, nor did I kill a giant with a cudgel; a fool’s weapon for a man with a spear and sword. I kept my arms;, though more than one tried to have them off me; I had no need of monsters, with the men I met. It is rocky country, where the road tracks about, and you can never see far ahead. Among the rocks by the road, the robbers lie up.’

This is, of course, the Corinth Peninsula (down which I have ridden in a prosaic coach, encountering only hazardous bends and noting all the rubbish strewn about) and vividly recreated as it would have been in the Bronze Age, when Theseus of legend made his way from Troezan to Athens.

The first person point of view, of course, presents notorious difficulties. We don’t get an objective view of the narrator if things are told from only one point of view. Instead, the author must rely to some extent, on the perception of the reader. She has to make enough hints to guide that readers’ judgement about how far this point of view is valid, fair, honest, etc,etc.

I had some evidence of that over on Amazon com on the topic of that very Theseus I have just quoted. While Mary Renault, though gay, didn’t have the highest regard for women in general, I am sure she didn’t intend her insensitive, violent and war prize taking Theseus to be a glowing example of manhood for her own age. Yet, I was disturbed to come across reviews – and by persons going out of their way to dub themselves as Christians – which hold him up as a role model for early twenty first century young males. As in Renault’s reworking of the myth Theseus ends up murdering his wife Phaedra, not the best idea.

I remember enrolling for a course on short story writing for ‘The Writer’s News’. One of the projects was a ghost story. I wrote an absurd one from the point of view of the ghost, a pretentious, narrow minded, snobbish, prudish, and self righteous individual, who ranted unappealingly, in verbose style. The tutor’s comment? That I really must try and make my style more fluid, cut down on the use of cliché and adjective, and try and make my characters more sympathetic…

The first person point of view used to depict an unsympathetic character failed there with a vengeance. No doubt a lot of that could be put down to inexperience on my part, and having a project over ambitious for a 2,000 word limit.

Frances Burney’s ‘Evelina’ uses the epistolary method, and the letters are from other people besides the naïve heroine, presumably to give some objective balance in the story. Nevertheless, a fault that can arise in this method is revealed in the heroine’s own letters, which give an unfortunate impression of vanity as she recounts compliment after compliment.

An interesting variant on the first person point of view is to be found in another story featuring Theseus – this time as the villain of the piece in June Rachuy Brindel’s brilliant and underestimated novel ‘Ariadne’ , another story telling the overthrow of matriarchy in the Bronze Age.

This story is told from the point of view of Ariadne herself, the Queen of Crete, and intriguingly enough, from that of the unappealing opportunist Daedalus, her one time tutor, and the father of her late lover Icarus. Daedalus betrays Ariadne to her scheming lover Theseus – not warning her of his evil intentions - in exchange for a passage to Athens. Though contemptible, he seemingly retains a lively sense of humour, witness his description of the boastful and drunken Theseus: -

‘It was a braggart’s tale, enlivened with much muscle flexing, swinging of arms, demonstrations of wrestling holds, fighters tricks…The way he told it, he had cleansed the countryside between Troezon and Athens of thieves, murderers, and monstrous beasts…But as I questioned him more closely, it appeared that some of them might have been described in another way….This honking gander was my only hope of transport. I nodded…’

A fascinating aspect of third person narration is whether or not to be an omnipotent or an only partly informed narrator, or one who is sometimes all-knowing, sometimes ill-informed.

Interestingly, for instance, in Pushkin’s robber novella ‘Durbrovsky’ this is what happens – the narrator knows what is going on in the heads of the main characters, and of what is happening in the area generally for the first part of the novel, but then seems to be as unaware of the identity of the mysterious tutor who turns up at Kirol Petrovitch’s house as the reader is supposed to be until he unmasks himself: -

‘Anton Pafnutyevich opened his eyes, and by the pale light of an autumn morning saw Deforges standing over him. The Frenchman held a pistol n one hand, and with the other was unfastening the precious leather pouch.’

‘Qu’est ce que c’est, monsieur, qu’est ce que c’est ?’ He brought out in a trembling voice.

‘Sssh! Be quiet!’ the tutor replied in the purest Russian. ‘Be quiet, or you are lost. I am Dubrovsky.’’

The second person point of view I have only read in two short stories, neither of which, I’m sorry to say, impressed me. These were both in the same woman’s magazine, but several months apart, and highly emotional in tone. Both, for some reason, were goodbye letters.

One was an explanation by a teenage single mother for her unborn baby as to why she couldn’t keep him or her, and one was written to a husband by a wife during a ‘difficult period’ in a marriage, explaining why she couldn’t stay with him.

Both writers reversed their decisions during the course of the letters, which I gather was meant to astonish the reader, although the magazine in question being so family oriented and conventional, I couldn’t imagine any other outcome from the first sentence. I’ sure they evoked many a sigh and a tear; as for me, I’m sorry to say, I was merely irritated.

However, I’m sure there are excellent examples of the use of the second person point of view which I may come across in the future.

Perhaps a second person plural point of view novel written to a whole group of accusers would be particularly fascinating…But no wandering from the present project for me!

I’ve posted before on the whole issue of how much of a ch...

I’ve posted before on the whole issue of how much of a character’s thoughts, feelings, and general inner life to reveal in a book – is it more intriguing to have one laid bare – or one who retains an element of mystery?

I’ve posted before on the whole issue of how much of a character’s thoughts, feelings, and general inner life to reveal in a book – is it more intriguing to have one laid bare – or one who retains an element of mystery?

However much of the character one chooses to reveal is all, of course, inextricably bound up with the point of view the author chooses to use – third person, first person, second person – or even some variant.

I wrote the first draft of ‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’ in two first person’s – Sophie and Emile’s – and it was only because I was intrigued by the idea of having Emile only seen from the outside – and therefore, remaining to some extent throughout, smf particularly during his monster stage, inscrutable – that I finally went over to the third person point of view. He had to be seen by other people throughout, Sophie, Lord Ynyr, Georges, etc.

Previously, I did enjoy portraying events from his light hearted, rascally viewpoint; I was reminded of that when I recently read the letters of the villain Lovelace in Samuel Richardson’s ‘Clarissa’. I recalled how intriguing it was to use that particular version of the first person also when I read an excellent YA book in the spring, Kate Haney’s ‘Someone Different’, also written from the point of view of the two main characters.

This inspired me to go back to it in the novel I haven’t been long at work on – called tentatively, ‘The Villainous Viscount or The Victims’ a return to a Gothic theme.

The main male character in this is an anti hero for sure – the complicated villain I have recently become interested in portraying; .

I did read somewhere – and typically forgot where – that a recipe for failure is writing about an unsympathetic character in the first person. Mind you, according to some ‘How To’ books on writing, any sort of innovation is a guarantee of failure. I personally think it idea has a lot going for it (she said arrogantly, facing the prospect of disastrous sales). The lame self-justification, the insensitivities of a wicked character can make for intriguing or grimly amusing reading, and a lively, charming wicked character who must nevertheless be seen as too bad to be capable of reformation (unlike my previous lovable rogues Emile and Reynaud) is a real challange.

I hope I’m not speaking too soon. Trust me to do that. I’ve had a few weeks of the dreaded writer’s block, of starting projects that foundered, and churning out those Early Morning Tea Four Hundred Words in longhand only to look at them later with disgust – ‘What made me think that was any good?!’

I remember how in an excellent ‘How To’ book on writing, James N Frey’s ‘How to Write a Damn Good Novel’ he points out that it isn’t necessary to use the first person to get inside a character’s head.

Instructively, he quotes one of the earliest Stephan King novels as evidence, rewriting a scene from Carrie’s first person as distinct form third person point of view, and it isn’t any more telling. I wish I had the book to hand as this is impressive evidence of Stephan King’s skill. For all that, it is easier, somehow, to take on the mood, the persona, the language of a character when you actively get into his or her viewpoint.

The first person point of view can also make for particularly lively reading; I am sure I must have said a good few times before how much I dislike that arch patriarch, the matriarchy destroying Theseus, in Mary Renault’s book ‘The King Must Die; – but he is, if obnoxious to me, the livliest of narrators, until taken over by premature aging and bitterness. For instance: -

‘I met no monsters, nor did I kill a giant with a cudgel; a fool’s weapon for a man with a spear and sword. I kept my arms;, though more than one tried to have them off me; I had no need of monsters, with the men I met. It is rocky country, where the road tracks about, and you can never see far ahead. Among the rocks by the road, the robbers lie up.’

This is, of course, the Corinth Peninsula (down which I have ridden in a prosaic coach, encountering only hazardous bends and noting all the rubbish strewn about) and vividly recreated as it would have been in the Bronze Age, when Theseus of legend made his way from Troezan to Athens.

The first person point of view, of course, presents notorious difficulties. We don’t get an objective view of the narrator if things are told from only one point of view. Instead, the author must rely to some extent, on the perception of the reader. She has to make enough hints to guide that readers’ judgement about how far this point of view is valid, fair, honest, etc,etc.

I had some evidence of that over on Amazon com on the topic of that very Theseus I have just quoted. While Mary Renault, though gay, didn’t have the highest regard for women in general, I am sure she didn’t intend her insensitive, violent and war prize taking Theseus to be a glowing example of manhood for her own age. Yet, I was disturbed to come across reviews – and by persons going out of their way to dub themselves as Christians – which hold him up as a role model for early twenty first century young males. As Theseus ends up murdering his wife Phaedra, not the best idea.

I remember enrolling for a course on short story writing for ‘The Writer’s News’. One of the projects was a ghost story. I wrote an absurd one from the point of view of the ghost, a pretentious, narrow minded, snobbish, prudish, and self righteous individual, who ranted unappealingly. The tutor’s comment? That I really must try and make my style more fluid, cut down on the use of cliché and adjective, and try and make my characters more sympathetic…The first person point of view used to depict an unsympathetic character failed there with a vengeance. No doubt a lot of that could be put down to inexperience on my part, and having a project over ambitious for a 2,000 word limit.

Frances Burney’s ‘Evelina’ uses the epistolary method, and the letters are from other people besides the naïve heroine, presumably to give some objective balance in the story. Nevertheless, a fault that can arise in this method is revealed in the heroine’s own letters, which give an unfortunate impression of vanity as she heroine recounts compliment after compliment.

An interesting variant on the first person point of view is to be found in another story featuring Theseus – this time as the villain of the piece in June Rachuy Brindel’s brilliant and underestimated novel ‘Ariadne’ , another story telling the overthrow of matriarchy in the Bronze Age.

This story is told from the point of view of Ariadne herself, the Queen of Crete, and intriguingly enough, from that of the unappealing opportunist Daedalus, her one time tutor, and the father of her late lover Icarus. Daedalus betrays Ariadne to her scheming lover Theseus – not warning her of his evil intentions - in exchange for a passage to Athens. Though contemptible, he seemingly retains a lively sense of humour, witness his description of the boastful and drunken Theseus: -

‘It was a braggart’s tale, enlivened with much muscle flexing, swinging of arms, demonstrations of wrestling holds, fighters tricks…The way he told it, he had cleansed the countryside between Troezon and Athens of thieves, murderers, and monstrous beasts…But as I questioned him more closely, it appeared that some of them might have been described in another way….This honking gander was my only hope of transport. I nodded…’

A fascinating aspect of third person narration is whether or not to be an omnipotent or an only partly informed narrator, or one who is sometimes all-knowing, sometimes ill-informed.

Interestingly, for instance, in Pushkin’s robber novella ‘Durbrovsky’ this is what happens – the narrator knows what is going on in the heads of the main characters, and of what is happening in the area generally for the first part of the novel, but then seems as unaware of the identity of the mysterious tutor who turns up at Kirol Petrovitch’s house as the reader is supposed to be until he unmasks himself: -

Anton Pafnutyevich opened his eyes, and by the pale light of an autumn morning saw Deforges standing over him. The Frenchman held a pistol n one hand, and with the other was unfastening the precious leather pouch.’

‘Qu’est ce que c’est, monsieur, qu’est ce que c’est ?’ He brought out in a trembling voice.

‘Sssh! Be quiet!’ the tutor replied in the purest Russian. ‘Be quiet, or you are lost. I am Dubrovsky.’

The second person point of view I have only read in two short stories, neither of which, I’m sorry to say, impressed me. These were both in the same woman’s magazine, but several months apart, and highly emotional in tone. Both, for some reason, were goodbye letters.

One was an explanation by a teenage single mother for her unborn baby as to why she couldn’t keep him or her, and one was written to a husband by a wife during a ‘difficult period’ in a marriage, explaining why she couldn’t stay with him.

Both writers reversed their decisions during the course of the letters, which I gather was meant to astonish the reader, although the magazine in question being so family oriented and conventional, I couldn’t imagine any other outcome from the first sentence.

However, I’m sure there are excellent examples of the use of the second person point of view which I may come across in the future.

Perhaps a second person point of view novel written to a whole lot of people would be particularly fascinating…But no wandering from the present project for me!

June 26, 2014

Review of Sameul Richardson’s Clarissa

I finally finished ‘Clarissa’ a couple of weeks ago.

I finally finished ‘Clarissa’ a couple of weeks ago.

It’s an incredibly long read, and sometimes a tedious one. Richardson never writes fifty words when five hundred will do,and he just loved to tell not show.

His moral expostulations that so amused Coleridge are even more in evidence here than in Pamela: the moral conflict between Lovelace and Clarissa has more at stake than the one between Mr B and Pamela, because finally Lovelace is shown to be too wicked to be capable of reformation.

In Richardson’s earlier novel, Mr B does, after his outrageous attempts on Pamela in the first half of the story, have a (somewhat unconvincing) moral turnabout and offers Pamela the marriage which, it seems, makes all these earlier, shabby attempts on a servant’s maid’s body all right.

To be fair to Richardson, Mr B supposedly clears himself of charges of attempted rape in ‘Pamela in Her Exalted Condition’ (one of the dullest books I have ever read), explaining away his dramatic leaps from cupboards and pinning her down with the help of the brutal Mrs Jewkes as apparent misunderstandings (!!!). Mr B, though debauched enough to be a seducer, is not finally to be seen as a rapist.

Lovelace was almost certainly a rapist before he ravishes the drugged Clarissa – (an act he blames on the prostitutes in the brothel, two of them girls he has debauched himself). We hear of his abducting a woman he admired before, and when he got her to the inn, as he blithely admits to his tool Joseph Leman, ‘It’s true I didn’t ask her for her permission. It’s cruel to ask a virtuous woman’.

He schemes to kidnap and rape Clarissa’s friend, his opponent Anna Howe, in a maritme raid in which he hopes to include his group of fellow debauchees, but this idea comes to nothing as his obsession with Clarissa leads to her own desctruction at his hands.

He also casually suggests drowning a treacherous mistress of his dying friend Belton, along with the two boys of doubtful paternity (it’s hard to tell from the context if he is serious or not).

The style of this shameless brute is throughout lively and amusing enough sometimes to beguile the reader almost into warming to him at times – until you remember his disgusting history of abuse of women based solely on one disappointment in love, and an apparent conviction (shared with Richardson) that a woman’s ‘chastity’ is her only honour. He is a great believer in the rakes’ code that the only women worthy of respect are the ones who will reject his advances.

We see him being charming to his cousin Charlotte, winning her over with kisses, and entertaining his rakish friends. We see him scheming diabolically, excusing himself inadequately, and finally, being destroyed by Clarissa’s avenger Colonel Morden. His final words during his death throes are ‘Let this expiate!’ Presumably, this is addessed to Clarissa herself. What can expiate his behaviour to his other victims, and those he has made into brutes themselves, isn’t a question Richardson addresses.

His scheming is sometimes ludicrous – for instance, wishing to test Clarissa’s feelings for him, he doses himself with the emetic ipecacuanha and he sends out for blood from the butchers to mix the vomit to convince Clarissa that he is dangerously ill ( of course, she is duly compassionate).

Lovelace can’t explain away his diabolical machinations when Clarissa comes to believe in them; the reader has access to them from the beginning through his detailed correspondence with his friend Belford, who later goes over to the Clarissa camp and lets her see his friend’s letters, thereby exposing the full extent of his pointless and elaborate schemes against her virtue.

I don’t believe anyone – even at the time – could possibly really have thought of this novel as true to life. There are domestic details which are, obviously, for Richardson, ever a vivid and lively writer when not launched on a moral homily, can bring his imaginative world to life admirably. His depictions of life in great houses, in a brothel and in eighteenth century shop, are colourful and interesting; still, his story is in no way believable and most of his characters and their relationships are improbable, whether they are virtuous or debauched.

Clarissa is an impossible seventeen year old ( the more extraordinary as she ages two years in eight months and is nineteen at the time of her death). She is always virtuous and dutiful.

She does appear to give way, very early in the novel, to one fit of spite when she describes her sister Bella as having ‘a high fed face’ but even this may be a fault in his ‘epistolary method’. This remark is more suited to the acid pen of Anna Howe than that of the high-minded Clarissa. Her purity is such that nothing can soil even to her ruffles – these remain unsoiled in the grubby ‘spunging house’.

I don’t wish to give the impression that I in any way am decrying Richardson’s massive achievement as a man who was interested through portraying the conflict between a virtuous woman and a rake, to warn ‘the inconsiderate and thoughtless of the one sex against the base arts and designs of specious contrivers of the other- to caution parents against the undue exercise of their natural authority over their children in the great article of marriage’.

In showing the lurid and almost insane scheming of Lovelace to overcome Clarissa’s resistance to his seduction attempts after he has lured her away, helped massively by her family’s horrible insistence that she make an advantageous match with a man she finds physically repulsive, and after he has trapped her in a brothel – Richardson was faithful to his scheme. He used an exciting, if incredible story, and vivid, if over the top characters, to make his points.

While this novel has many weaknesses quite apart from the ones I have mentioned - for instance, Lovelace’s scheme to try Clarissa’s virtue to the point that he does doesn’t even make sense within his own frame of reference – having given her a short ‘trial’ instead of becoming embroiled in schemes that made acting honourably by her impossible, he should have married her and calmly refused to reform – it is still, particularly given the undeveloped state of the novel in this era, an impressive achievement.

He did what James N Frey calls ‘following through’ with admirable consistency, killing off Clarissa through a decline and causing Lovelace’s own death in a duel later on. We are left with little doubt of Lovelace’s final destination.

I’m glad to say I don’t believe in hell and damnation, but Richardson clearly did, and makes it obvious that Colonel Morden feels a good deal of guilt for having dispatched such a villain before he had time to repent, as Clarissa pleaded for him not to do in her posthumous letter.

While Richardson’s heroine and embodiment of virtue has become an anochronism, his dated but complex villain still gives inspiration and food for thought.

June 19, 2014

My Family’s Herat Book Tour and Extract from ‘Ravensdale’

My Family’s Heart Book Reviews are running a book tour for my book ‘Ravensdale’ this week. I’d like to thank Tonya and Everyone.

Here’s an extract from ‘Ravensdale’.

Mr Fox stole towards a back garden separated from the park by a ha-ha*. Jumping the ditch, he vanished amongst the shrubs and bushes. Longface, following more cautiously, nearly twisted his ankle.

Suddenly, Mr Fox sprang behind a bush. Longface leapt behind a lilac tree. The strapping wench who’d floored Filthy Fred came round the side of the house, holding a pair of pistols, and made for a target fixed to one of the shrubs.

She wore a pale lemon dress with matching floppy bonnet contrasting with her dark mane of carelessly piled up black hair. Longface supposed that she looked quite pretty. The sight of her had an astounding effect on his companion, who reeled on his feet and ogled like a madman.

She went over to a bench, and began to load the pistols. Longface shuddered. She got into difficulty with the wadding in the first, and after struggling for a while, shocking Longface with her language, threw it on the bench and marched about the rose garden in her rage.

Here Mr Fox showed the full extent of his madness. He stole up to the bench, and using a stone, hammered the wadding securely into place, darting back as the girl turned.

Longface awaited detection. On seeing that the pistol had been loaded, the girl merely raised her eyebrows, smiled, and moved towards the target. Longface, behind a bush nearby, threw himself to the ground, covering his head with his arms. The shot rang out. Looking up, he saw that she had shot through the centre of the target and was smiling happily.

Longface, startled at how charming her smile was, dreaded its affect on the deranged Mr Fox, who quivered and seemed about to have a fit.

The next hour was both dull and nerve racking. The besotted outlaw dodged from bush to shrub, yearning eyes fixed on the hoyden, while she practiced her shooting, singing happily as she loaded the pistol, swearing savagely when she bungled her aim.

Longface dreaded that she must see one of them, but Mr Fox was good at concealing himself. Once he sprang behind a bush at the back of which Longface had already rolled. One of his booted feet came down on Longface’s favourite neck cloth. Longface felt at his last gasp when his tormentor finally moved, tearing it and leaving Longface panting.

At last, a maid came out to speak to the girl. In frozen horror, Longface heard the words, ‘Mr Ravensdale’. Could this be the cousin whom the rumour went had been involved in the then Viscount’s disgrace?

Miss Isabella agreed to be led in, the maid fussing about her heavy dark hair tumbling down, one piece having snaked as far as her waist. On her way into the house, Mr Fox’s goddess dropped a lace edged handkerchief. Of course, as soon as she had gone in, he darted to snatch it up, sniffing it ecstatically and fondling it as if it were the girls’ own flesh.

Then he staggered over to a tree, and beating his head on it, muttered of ‘Outlaw’ ‘Cozened, by Hell and the Devil!’ ‘Brigandage’ and ‘Disgrace’. Longface’s embarrassment at this display was swept away in fear that the Young Hothead might do himself an injury.

He also wondered vaguely if he was Disgraced himself. The emotional effect was the same, but as after his father’s ruin his goods amounted to half a donkey and a pound in silver, the practical effects weren’t. Meggie was lucky to have had any solvent man offer for her after it, even if her husband was a misery.

He started forward to stop Fox just as the outcast pulled away from the tree. Then he stole round the side of the house. Here great windows opened on to a long terrace. With bleeding forehead and wild eyes, he hid behind one of the rhododendrons, staring across at the windows, one being that of a drawing room. Longface feared even more for his sanity, wondering if they would ever leave.

After a while, the Disgraced Earl’s patience was rewarded. Several family members came into the room, including the hoyden, now dressed for dinner in ivory silk, her hair up again. She did look well, and the outcast groaned aloud. Longface’s fears were confirmed at the appearance of an upright, tall, vigorous young man with bright brown hair and handsome features who could almost have been the outlaw’s twin.

A woman’s voice came stridently over the lawn, repeating, ‘Mr Ravensdale’ as if she could never say it often enough. Soon, this other Ravensdale came up to the piano near the window and Miss Isabella sat down to accompany him while he sang in a fine baritone:

‘Where’er you walk, cool glades shall fan the glade;

Trees, where you sit, shall crowd into a shade;

Where’er you tread, the blushing flowers shall rise,

And all things flourish, where you turn your eyes…’*

Mr Fox writhed. Longface felt his pain. Miss Isabella laughed with his cousin as they finished the song, and so the outlaw’s torment wore on.

Then Edmund Ravensdale came out onto the terrace to take a turn in the air alone.

Now the outlaw’s hand crept to this pistol, and he took aim. The only thing that stopped Longface from throwing himself on him was a strange sense, he knew not from where – that something of the sort had happened before with Reynaud Ravensdale and turned out badly. He stared frozen instead.

Then his chief put his hand on the rumpskuttle’s handkerchief and thrust his pistol back into his belt. His cousin went back in. The robber turned away hunched. On his way back towards his horse, he murmured once:

‘Ye Gods, and is there no relief from Love?…

On me love’s fiercer flames forever prey,

By night he scorches, as he burns by day.’

Longface, dolefully chewing on a piece of grass, muttered, ‘He’s gone fairly off his chump.”

After a few more steps, Mr Fox stopped. So did Longface, but the other, without troubling to turn round, called him.

Sheepishly, Longface approached. He was astounded that his chief had seen him when he had been hiding so skillfully. Still, Mr Fox had sharp eyes, so needed in their trade.

Fox was too distracted even to be angry. He swallowed. “Now you know.”

Longface met his eyes, and turned away. “I’m sorry,” he offered. He had once known the torments of love himself.

On their long, silent ride back to the inn, Longface tried to think of some comforting words to say, but found none. Perhaps, ‘There must be other strapping wenches with gipsyish looks and a liking for fisticuffs and shooting,’ wasn’t tactful. To suggest Kate’s cure might spark off a fit of rage. So, he kept a discreet silence, fingering his torn neck cloth.

As they drew into the inn yard, Longface’s chief spoke. “We’ve got our prize; Jack is to Town. Now is your chance to retire into respectability, Longface, as I’m going for a respectable occupation myself.” To Longface’s amazement, he grinned.

Late that night, when all was still in The Huntsman, Reynaud Ravensdale appeared downstairs, light in hand, looking for something. He searched first in the bar, then in the kitchen. At last his eyes fell on the brown bottle of the pedlar’s cure, also known as The Famed and Marvellous Elixir, which stood next to the teapot. Finding a big spoon, he gulped down a large dose. Then he stood, waiting for the result.

This came speedily. His eyes widened, his face drained of colour, his breathing quickened and he swallowed and looked very ill for the next five minutes. Finally, recovering enough to speak, he swore heartily, poured the bottle down the sink, and trudged back to bed.