Lucinda Elliot's Blog, page 26

August 6, 2015

Writing and the Unconscious

It’s odd, the way the unconscious works; for all the research on it since the concept was first explored in any depth by Freud in the late nineteenth century, it remains even more an unexplored area than the depths of the ocean.

It’s odd, the way the unconscious works; for all the research on it since the concept was first explored in any depth by Freud in the late nineteenth century, it remains even more an unexplored area than the depths of the ocean.

Yet, writers particularly rely on it even more than artists, I think; I know there are those who dispute the existence of this hidden depths of the mind at all, though how they account for the strangely dream like state in which writers create, I don’t exactly know; possibly a form of madness?

I do know that some complete scenes for books have come to me when playing baroque music –played out like a film in my minds eye, and it is interesting that some sources argue that baroque music does in fact make both sides of the brain (my what?) work in harmony. I can’t find any link on this at the moment, though, which would indicate that at least one side of my brain isn’t working too well…

Some months ago, when writing about writer’s block (ugh!) I came on some intriguing advice on this website, which suggests amongst other things that writers should try to write as early in the morning as possible, as the time when you are closest to sleep is also the time when you are closest to your unconscious, and that this is excellent for creativity. Of course, this isn’t possible for lots of people, and it’s purely impossible for anyone with a small child, unless that child happens to be an angelic sleeper, but I do think that there is something in this; it’s surprising how if you start writing when half asleep, after a truly horrendously bad night, the ideas seem to start to flow almost of their own accord (but not always, of course; and almost certainly not when suffering from a dismal case of writer’s block).

Again, I can’t find that link (indicating that I am particularly poor at finding links in the evening) but I have found some fascinating discussion on this link

https://blog.bufferapp.com/the-best-time-to-write-and-get-ideas

‘As mentioned above, creativity peaks in the morning as the creative connections in our brains are most active. If you believe that creativity is your best source for ideation, then the early morning should be your best time for new thoughts.

The greatest evidence for this effect is with dreams. Science has told us that creativity is a function of connections between many different networks throughout the brain. With that in mind, consider this observation from Tom Stafford, writing for the BBC:

An interesting aspect of the dream world: the creation of connections between things that didn’t seem connected before. When you think about it, this isn’t too unlike a description of what creative people do in their work – connecting ideas and concepts that nobody thought to connect before in a way that appears to make sense.

Try this: Ideas when you’re at your groggiest

If early morning idea sessions aren’t your cup of tea, you might be interested in a study from Mareike Wietha and Rose Zacks that found creative ideas often come at our least optimal times.

Their experiment measured insight ability and analytic ability, two components to the creative idea process. Participants identified themselves as either morning people or evening people and underwent a series of tests at different times of day. The tests for analytic ability revealed no significant findings, but for insight ability, the results were telling:

What Wieth and Zacks found was that strong morning-types were better at solving the more mysterious insight problems in the evening, when they apparently weren’t at their best.

Exactly the same pattern, but in reverse, was seen for people who felt their brightest in the evening: they performed better on the insight task when they were unfocused in the morning.

The theory goes that as our minds tire at our suboptimal times then our focus broadens. We are able to see more opportunities and make connections with an open mind. When we are working in our ideal time of day, our mind’s focus is honed to a far greater degree, potentially limiting our creative options.’

It is interesting that with regard to the unconscious, Freud and Jung fell out over their differing interpretations of it; Jung wished to incorporate an element of what would now be seen as ‘parapsychology’ into his concept of the unconscious, and believed that at their deepest level all our unconscious minds are linked; this all, of course, links in with his ideas about what he called ‘synchronicities’ – the statistically impossible number of strange co-incidences in everyday life.

This concept might explain how it is that two writers can come up with strikingly similar ideas for plots, characters, etc at the same time.

When writing, you are aware of conscious influences to your writing – in my case, for instance, Jane Austen and Patrick Hamilton –but how far are we aware of those unconscious influences? We are most likely being influenced by some event or reading material long forgotten.

For that matter, why do we remember the reading material we do remember? Is this because it has a lingering fascination for us? I think this may be so, however critical we may be of it.

I have written before about the snowed in period in the Clwyd Valley, where I was reduced to reading a good deal of stuff bought as ‘job lots’ in auctions by my parents to fill the innumerable bookshelves in the house. I read several books by Georgette Heyer and ‘The Outcast of the Family’ by Charles Garvice.

I recall, too, the plots of some of the books which I read a couple of years before this, when I started to read adult fiction.

One of these was a grim story of remarkable political incorrectness concerning two men of restricted stature called ‘Me and Victor and Mrs Blanchard’; probably the main reason why I remember that, is the astounding brutality of the scene where another male lodger is terribly beaten during a fight and left half dead on the stairs.

Another was one I have never been able to trace, a short story about a man who did almost nothing, and spent hours sitting with his feet up on the doorknob. Another occupant of the house told him: ‘I hate you because you’re a bum; everyone hates you.’

I don’t, however, remember the ending. Maybe the protagonist became a workaholic whom everyone adored. I have never been able to trace this story, although I’d like to re-read it, as it’s subject matter seems so unusual; but it’s notoriously difficult to trace a short story.

I read another story which a female relative who shall remain nameless had out from the library, a romance by Barbara Cartland. Set in Victorian England, it concerned an very unhealthily overweight girl in the US whose mother forced her to marry an English duke for the title; while he was marrying her for money, and had no plans to see her after the wedding.

She collapsed immediately after the marriage, and her tiara rolled down the aisle; her mother was so outraged that she died of a heart attack. The girl lay in a coma for a year, but during this time, her devoted aunt gave her massage and fed her healthy drinks, so that when she woke up a year later, she weighed seven stone, and her hair had miraculously turned from mousey to silver gilt.

Shortly afterwards, she set off to England to work in some capacity for the duke she had married (I’ve forgotten what job she took up; or why; I do remember the aunt thoroughly approved of the scheme). The rest of the story was predictable, but it took me some time to realise that it wasn’t a spoof, as it could be read as a truly wonderful one.

I wonder what was going on in the unconscious of Barbara Cartland when she wrote that one…

July 31, 2015

Writers’ Terror of Writing a Derivative Novel: Comparing George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ and Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’

I’ve always meant to read ‘Adam Bede’; I don’t know why really, except that I’ve seen it described in various places as one of George Eliot’s best novels, and while I was a little disappointed in ‘Middlemarch’ and ‘The Mill on the Floss’, I’ve always admired her as a woman who defied conventional morality in mid Victorian times. That took some courage indeed.

I’ve always meant to read ‘Adam Bede’; I don’t know why really, except that I’ve seen it described in various places as one of George Eliot’s best novels, and while I was a little disappointed in ‘Middlemarch’ and ‘The Mill on the Floss’, I’ve always admired her as a woman who defied conventional morality in mid Victorian times. That took some courage indeed.

I’m about three quarters of the way through reading it now. It’s a very interesting book, and the historical detail is intriguing; but I can’t take to the rather shadowy heroine, Dinah Shore, at all. She is intended to be the next thing to a saint; I know it is notoriously hard to write about an interesting thoroughly good and unselfish person, and George Eliot deserves credit for trying; this particularly as she is depicting a devoutly religious person, while she herself was agnostic. But I have to say this conventional spirituality is another sticking point for me; oblique references are made to damnation, and the idea of a Creator who is capable of meting out that fate raises my hackles.

Unfortunately, too, the same is true of the eponymous hero; I find his Protestant Ethic type of morality unappealing, even rebarbative; I daresay he is the sole of virtue and totally admirable, but if I find anyone sympathetic in the story, it is the pretty, silly Hetty Sorrel, so tragically deceived by her own hopes regarding the enduring nature of the charming but vain and selfish Arthur Donnithorne’s love for her.

I suspect that this reaction may be fairly typical; I haven’t read any literary criticism of the book yet. Still, it isn’t of this that I wanted to write, but about the influence that this novel so obviously had on Elizabeth Gaskell, and in her writing of a novel about which I have so often bored the reader – that’s right, ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ again!

I was startled when I came across some of the similarities in the character types and also, in incident in the two novels. This in turn led me to think about the modern obsession with avoiding at all costs, writing something ‘derivative’, the dread that so many writers have of being accused of copying some theme or idea.

Elizabeth Gaskell, according to the biography of her by Winifred Gerin, read ‘Adam Bede’ sometime in 1857, and her admiration was complete. She wrote of it: ‘I think I have a feeling that it is not worth while trying to write, while there are such books as Adam Bede’ (I had the same sort of feeling myself after rereading ‘Bodily Harm’ by Margaret Attwood).

Eighteen-fifty-seven was the year in which Elizabeth Gaskell visited Whitby (Yorkshire, UK, for non UK readers of this blog) and decided to write a story about the whaling community there during the French Revolutionary Wars, and the activities of the press gang on a whaling community at that time. ‘Adam Bede’ is also set during the French Revolutionary Wars, and in partly in Yorkshire, but it is focused on in an inland farming community. However, in other ways the influence of George Elliot’s novel on Elizabeth Gaskell is very obvious, and Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel is also partly about the local farming community.

Both novels deal with a rather foolish, very pretty, poorly educated young girl from a farming background who often works as dairymaid and who is loved by a steady admirer whose love she spurs in favour of the love of an unreliable, charming, dashing but superficial one with military connections.

In ‘Adam Bede’ these characters are respectively Hetty Sorrel, Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne, and in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ they are Sylvia Robson, Philip Hepburn and Charley Kinraid.

It is true that ‘Adam Bede’ deals with the then highly popular theme of the innocent girl seduced by the ‘gentleman’ and left pregnant, while ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ deals with the then equally popular story of the ‘returned sailor’ who comes back from years at sea to find he has seemingly been betrayed, his sweetheart having married someone else.

However, in both, besides the threesome of flighty, heedless girl and her two contrasting rival lovers, there is another main female character, a spiritual and deeply religious young woman who comes to love the steady, hard working man.

In ‘Adam Bede’ this is the lay preacher Dinah Shore (who is also very good looking, but indifferent to this and its affect on men) and in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ this role is fulfilled by plain Hester Rose, a Quaker who routinely does good works, and Hepburn’s fellow worker in the haberdashery shop.

I haven’t read to the end of ‘Adam Bede’ yet, but I know that Dinah Shore and Adam Bede finally come together in marital happiness, whereas Hester Rose’s love for Hepburn remains unrequited. Both novels contain comedic elements but an underlying tragic theme.

Both also focus much attention on the views of dissenters and various religious debates in the late eighteenth century; both have human and ineffective vicars.

All sorts of incidental details in Elizabeth Gaskell’s story illustrate the continuing influence of ‘Adam Bede’. For instance, Hetty Sorrel comes from a farming family; so does Sylvia Robson; Hetty often works as dairymaid, and is courted by Arthur Donnithorne in the dairy; the same is true of Sylvia Robson, courted by Charley Kinraid in hers. The intensity of the relationship between Hetty and Arthur is increased when they come together at a party celebrating his twenty-first birthday; Sylvia and Kinraid’s relationship takes a serious turn when they meet again at the Corney’s New Year’s party.

Adam Bede comes to suspect that Hetty has an unknown lover when he sees that she has a locket with someone’s hair in it; Philip Hepburn sees that Sylvia comes out of the room where she has been kissing Kinraid wearing a new ribbon he has given her.

Both women are confronted by their steady and jealous admirers about the unreliability of their preferred lovers; Hetty says to Adam Bede, ‘How durst you say so?’ and Sylvia says to Philip Hepburn, ‘How dare you come here wi’ yo’r backbiting tales?’

In ‘Adam Bede’ a culminating moment of the general merrymaking at Arthur’s coming of age party is the absurd hornpipe danced by Wiry Ben. In ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ the New Year’s party is concluded by Charley Kinraid dancing a hornpipe amongst the platters on the floor.

And so on, even down to the similar use of unusual phrases; for instance, in ‘Adam Bede’ the author writes of Adam’s love for Hetty ‘Tender and deep as his love for Hetty had been, so deep that the roots of it would never be torn away…’ and then we have in ‘Sylvia’s Loves’ of Sylvia’s love for Kinraid, ‘She had torn up her love for him by the roots, but she felt she could never forget that it had been…’

Of course, there are even more dissimilarities between the two novels besides the obvious one of the one being set inland, the other being set in a whaling community; Sylvia Robson may be initially vain and headstrong, but she is not a superficial character, while Hetty Sorrel is; Philip Hepburn gives in to his jealousy and overprotective feelings for Sylvia and acts against his sense of honour, while Adam Bede resists the temptation and so on.

There are, however, numerous other similarities of phrase, incident and character in the novels, and I think I have made the point that two novels can have certain strong similarities without this necessarily being a disgrace. It has often been pointed out that there are only so many plots (in an earlier post, I listed these) and so many types of character (it would be interesting to try and break these down into basic types, and list those).

Just as I said then, I think that modern authors should not allow themselves to become too paranoid about writing something that has certain similarities to something already written, or even to be afraid to explore a different treatment of an idea they come across in any already published book; still, I must admit I have fallen into that error myself.

A couple of years ago, I was fascinated by the idea of writing a dystopia which involved a bad fair warrior, a good dark warrior, a female Amazon type, a society shattered by a series of earthquakes, and various other features. When I came to read Rebecca Lochlann’s brilliant ‘Child of the Erinyes’ series, I found all these features there; in dismay, I broke off from writing any more of the said dystopia (fortunately I had only written about 10,000 words), imagining my cringing embarrassment if readers assumed I had copied the ideas.

I now think that was a mistaken decision, and one of these days I ought to return to the idea (though I make no claims that my series would be as good as ‘Child of the Erinyes); different treatments using partly similar elements in a plot make for vastly different novels; the classics George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ and Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ are encouraging evidence of that.

It is certainly true that some of the contemporary critics did see a similarity between some of the themes in ‘Adam Bede’ and those in ‘Sylvia’s Loves’ ; though I haven’t read any literary criticism of Adam Bede, I have read a fair amount for Gaskell’s novel, and came across some comparisons there.

For instance, a review in ‘the Reader’ of 1863 states of Gaskell’s character Philip Hepburn: ‘the conception is feeble, and the execution indistinct. Philip Hepburn is Sylvia’s lover and nothing more…we cannot help comparing him with Adam Bede, and the difference between the two impressions of character is the difference between one character written in loose sand, and one engraved on a gem…there is a superficial resemblance to George Elliot’s Hetty in the heroine, which is quite lost sight of as we advance.’

Perhaps, in light of such reviews, Elizabeth Gaskell was wise never to read them. Probably, comparisons are inevitable for writers; it is a part of the way the human mind works, even if compariosns are notoriously invidious; but I think it would be unfortunate if writers were put off writing a book because they have come on one with a similar theme, or even, to hesitate in writing a book using a theme they have come across which they would like to treat with a different approach.

July 12, 2015

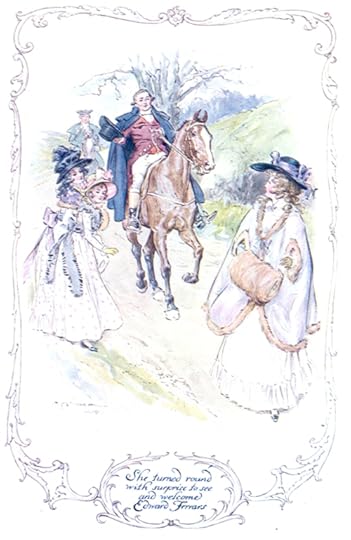

Jane Austen: Not a Writer of Romances

In my last post on Jane Austen, I commented that: –

In my last post on Jane Austen, I commented that: –

‘It is an irony that Jane Austen is seen as a writer of romances, when her own outlook on marriage, and the undesirability of marriage without a comfortable income, was highly practical and very much typical of the era, and the part of society, from which she came. Mr Darcy without at least a competence should have been politely and regretfully dismissed by Elizabeth Bennett.’

Really, I should have expanded on this; the comment on it from stephrozitis sums up my own view tersely: –

‘I think seeing Austen as a writer of “romance” genre is more than ironic- it’s inaccurate and does the writer a huge disservice. As you know she is one of the reputable writers trotted out by romance apologists. I don’t think her agenda is “boy meets girl” it’s more social critique and showing the places of (relatively privileged) women. Marriage is a huge part of that because those women have few options available to them but the interactions and character flaws are what makes the books readable and rereadable …’

I agree with this. Sadly, the romance writers of today who are eager to secure an intellectual and literary respectability for the romance genre by claiming that classic writers of the past were in fact, writers of ‘romance’ are frankly mistaken in Jane Austen’s case (I would argue that they are wrong about Samuel Richardson, Emily Bronte, and various others too; but that is irrelevant here).

As the poster comments, in assuming that because Jane Austen wrote about women finding marriage partners in the late Georgian and Regency era she was committed to modern notions of ‘romance’ , many modern proponents of the Jane Austen as writer of romance argument are underestimating the circumstances in which this most astute of social commentators wrote.

In her era, women from the upper middle class were obliged not to work except, as a last resort, as a governess or a companion. For them to work outside the home was seen as a disgrace on the male members of their family, who should in all honour support them if they did not find a marriage partner. If these women were not sufficiently blasé about social disgrace to become a form of prostitute, therefore, their only other option generally was marriage as the only respectable way to achieve some status in a household of their own.

Jane Austen’s stories, therefore, are not in my opinion romantic novels, but ones which give a social critique through telling a story of a young woman adapting to her environment and the compromises which she must make to function smoothly in it, of which a marriage which will be happy is part of the comedic outcome.

The story of Marianne, for instance, is in fact as strong a criticism of taking ‘romantic’ notions into marriage as I can imagine. This is, of course, a criticism of ‘the romantic’ in the terms in which it was understood in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which included the free and frank expression of the dramatic and the emotional in art and literature.

‘Romantic love’ was a component of this approach, but only a part of it; the modern concept of ‘romance’ is then, unfortunately, a sentimentalised version of a whole approach to life.

Marianne’s infatuation with Willoughy is only partly sentimentalized sexuality in the manner of current definitions of ‘the romantic’. It is also a striving to find another free and fiercely honest spirit in a world where she considers that almost everybody, including her beloved sister, is addicted to compromise in order for polite society to operate smoothly.

I have mentioned before that I do not particularly enjoy Jane Austen’s solution to Marianne’s disillusion with romanticism and her acceptance of the need for compromise in personal and social relations; her taking the sedate Colonel Brandon for a life partner was to me a disappointing solution. As I have said elsewhere, I would rather that Marianne had married a repentant (and partially reformed) Willoughby, and became, as she must, slowly disillusioned with him. Jane Austen, however, clearly considered that such a match would have led to more unhappiness for Marianne than she would have experienced in a rather passionless match with the excellent Colonel.

In that, then, Jane Austen designs her plot in a way quite contrary to those of the typical romantic novel.

Any regulars I might have might remember that this question also arises in ‘Mansfield Park’ where Jane Austen demonstrates Fanny Price obdurate against a charming and unprincipled Henry Crawford who finally disgraces himself, as does his sister, Mary, with whom Fanny’s true love and cousin is infatuated; Fanny then goes on to marry the steady rather than the beguiling man. And like Cassandra Austen, I was dissatisfied at the tameness of the particular happy ending that the writer chose.

Obviously, then, if these two examples are anything to go by, I am affected myself by current romantic notions in a way that Jane Austen clearly was not. My excuse is that I would go for the ‘qualified happy ending’ rather than the supremely happy one of conventional romance.

Even in ‘Pride and Predjudice’, generally seen as the most romantic of Jane Austen’s novels, with Mr Darcy extolled as the most desirable of tall, dark, dashing heroes, it might be noted that the narrator remarks that the development of Elizabeth Bennett’s feelings for him are not the ones associated with romantic infatuation: –

‘If gratitude and esteem are good foundations for affection, Elizabeth’s change of sentiment will be neither improbable nor faulty. But otherwise, – if the regard springing from such sources is unreasonable and unnatural, in comparison of what is so often described as arising on a first interview with its object, and even before two words have been exchanged – nothing can be said in her defence, except that she had given somewhat of a trial to the latter method, in her partiality for Wickham, and that its ill success might, authorize her to seek the other less interesting mode of attachment’.

One of the many things that differentiates Jane Austen’s writing from the rigid requirements of romantic fiction is her interest in social relations; a good deal of the space in her works is taken up, not by dwelling on the developing passions of the main couple, but by engaging in satirical wit at the expense of snobs and fools; sadly, when I last read the guidelines of Mills and Boon, it was emphasized that while a sub plot is permitted some space, the main emphasis must always be on the primary relationship between heroine and hero.

It is rather strange that with so many opportunities open to women that were not open in Jane Austen’s day, the most popular form of fiction amongst women today is one that concentrates mainly on finding life partners.

July 3, 2015

‘Sense and Sensibility’ by Jane Austen: Some Thoughts on the Main Characters

On the characters in ‘Sense  and Sensibility’, I have already commented on my liking for both the primary heroine, Elinor.

and Sensibility’, I have already commented on my liking for both the primary heroine, Elinor.

In some ways I prefer her to ‘Pride and Prejudice’s’ Elizabeth Bennett, as she seems less taken over by Edward than Elizabeth is by Mr Darcy. For instance, towards the end of ‘Pride and Prejudice’ Elizabeth has to remind herself that Mr Darcy ‘has yet to learn to laugh at himself’ and while I have no doubt that Elizabeth does to some extent teach him, it sounds, given his stately airs, something of an uphill task; I always feared that she would lose some of her liveliness in being too dutiful.

Edward Ferrars is a far less overwhelming personality than the imperious Mr Darcy, and is anything but proud; when he escapes the determined clutch of the terrible Lucy Steele, he castigates himself heartily to Elinor for his foolishness in ever becoming engaged to her: – ‘I had nothing in the world to do, but to fancy myself in love; and as my mother did not make my home in every respect comfortable…it was not unnatural for me to be very often at Longstaple, where I always felt myself at home, and was sure of a welcome…Lucy seemed to me then everything that was amiable and obliging. She was pretty, too –at least, I thought so then…’

Edward is a likable enough hero, but sadly, as he had to compete with the witty and showy Willoughby for the reader’s attention, doesn’t shine in comparison. However, I like his blunt remarks, which the more urbane Colonel Brandon would avoid, as when he is responding to Marianne’s enthusiasm over the view of Barton Valley: –

‘Amongst the rest of the objects I see before me, I see a very dirty lane.’

It has sometimes been observed by literary critics that it is difficult to write a character who is good and interesting, but I think Edward Ferrars is an excellent example of how this can be done; his faults of diffidence and shyness, his weakness in continuing to see Elinor, though he knows that he is falling for her and has to honour his engagement to Lucy Steele, make him very human; he is undoubtedly a good character of whom I always wished we had seen more in the story .

Elinor’s quite sense and detached humourous observation (in effect, Jane Austen’s own) are highly admirable, but even given that she is meant to be unusual, she is too mature outlook for nineteen.

Marianne’s opposite qualities, her passionate commitment to emotional honesty and her determined espousal of the romantic in paining, literature and real life are equally appealing, but disgusted by equivocation as she is, she can be unfeeling and even rude ( by the standards of the genteel of the time; compared to our own, she has advanced social skills). The task of placating and listening to people Marianne considers beneath her notice in one way or another usually falls to Elinor. For instance, when Edwrard’s disagreeable mother and sister are making inividoous comparisons between Elinor’s art work and that of an heiress they hope he will court, she exclaims: –

‘This is admiration of a very particular kind!! What is Miss Morton to us? Who knows and who cares for her? It is Elinor of whom we think and speak’.

Marianne at the end of the novel has become too saddened, too sedate as a consequence of her heartbreak by Willoughby for the reader not to feel a sense of loss. As one famous critic has mentioned, even her speech patterns change to the harmonious. It is true that the account of her accepting Colonel Brandon is given indirectly, which, as I have never been able to take to the worthy Colonel, I found a relief.

Everything is cleared up fairly quickly: – ‘Marianne Dashwood was born to an extraordinary fate; she was born to discover the falsehood of her own opinions, and to counteract, by her conduct, her most favourite maxims. She was born to overcome an affection formed so late in life as seventeen, and with no sentiment superior to strong esteem and lively friendship, voluntarily to give her hand to another!…whom, two years before, she had considered too old to be married, — and who still sought the constitutional safeguard of a flannel waistcoat!’

At thirty-five plus, Colonel Brandon would be too old for Marianne even if he was a far livelier character and that flannel waistcoat always just about finishes him as an appealing partner for such a girl for me.

As I have said in a previous post, I consider the ending to the story highly disappointing, as I did with ‘Mansfield Park’. Whether Jane Austen’s sister and confidante Cassandra (who expressed the view of myself and countless others before me, two centuries earlier over the desirability of Fanny Price marrying Henry Crawford, not Edmund Bertram) wished Marianne and a chastened Willoughby in the end to be brought together, I don’t know; but Jane Austen was nothing if not severe about rascals and took the view that they could cause only misery as husbands, not possibly, qualified happiness.

Jane Austen condemns Willoughby to resignation in an unhappy marriage with a bad tempered wife he doesn’t even like; he’s already confessed that he finds the idea of Marianne marrying Brandon : ‘His punishment was soon afterwards complete in the voluntary forgiveness of Mrs Smith, who, by stating his marriage with a woman of character, as the source of her clemency, gave him reason for believing, that had he behaved with honour towards Marianne, he might at once have been happy and rich.’

Jane Austen, with her incomparable irony, suggests as a sop that: ‘his wife was not always out of humour, nor his home always uncomfortable’. In other words, this was the case more often than not.

It is an irony that Jane Austen is seen as a writer of romances, when her own outlook on marriage, and the undesirability of marriage without a comfortable income, was highly practical and very much typical of the era, and the part of society, from which she came. Mr Darcy without at least a competence should have been politely and regretfully dismissed by Elizabeth Bennett.

June 25, 2015

Laughing Out Loud With Jane Austen; ‘Sense and Sensibility’ as Tragi-Comedy…

Recently, I re-read ‘Sense and Sensibility’.

Recently, I re-read ‘Sense and Sensibility’.

That is my favourite Jane Austen novel. The humour is brilliant; it made me laugh out loud a few times, and I can be hard to please.

‘Pride and Prejudice’ is equally funny, of course, and much lighter in overall tone; there is also the happy ending to the love affair of Jane and Bingley which is denied to Marianne and Willoughby. I loved the portrayals of vulgar relatives, the ‘pompous nothings’ of Mr Collins and his self-serving hypocrisy.

But in some ways, because I did ‘Pride and Prejudice’ for ‘A’ level, part of the fun was taken out of it on that first reading, seeing that you have to read with ‘an analytical eye’. You’ve got your notes to hand; look out for such-and-such. It was a wonderful piece of light relief after ‘Samson Agoniste’s’ (a poem I dislike to this day) and all the rest, though, and the first time I had read any Jane Austen.

My own delight in discovering her sense of the absurd, her penetrating exposure of hypocrisy – shared by so many readers over two centuries – was for me as for countless others, accompanied by the feeling that ‘Why didn’t people who recommended it tell me that this classic is so brilliantly funny? Saying, ‘It’s very good,’ means nothing.’

If I’d thought anything in my early teens about Jane Austen, I’d assumed that her novels must be primarily romantic, revolving around improbable love affairs, like those of some of her predecessors like Samuel Richardson, and many of her famous admirers.

And there’s the irony; I’m far from addicted to stories with misty happy endings, but as I have said in previous posts, maybe part of this is that stories with such endings so often are peopled by ‘lay figures’ – cardboard characters with whom it is hard to empathize. Unluckily, writers who are capable of portraying realistic and sympathetic characters tend to write novels where a happy ending – even a qualified one – is not the necessary or even a likely outcome.

Like countless others, I have always wished that a repentant (and unmarried) Willoughby came back to Marianne and that Henry Crawford returned likewise, glowing with new-found resolve of reform, to Fanny Price (who had started to soften towards him). I wouldn’t think it realistic that either couple should be any more than moderately happy for many years, though; the males aren’t sufficiently elevated to make sterling husbands; leave that to the Dull but Worthies…

Jane Austen’s characters are fully believable; they come from an age where terrible social injustice and the existence of servant drudges was necessarily taken for granted; sexual repression runs like an underground current of electricity throughout her novels; but the humour shines clear through all that. The sense of humour of Fanny Burney is crudely snobbish; that of Jane Austen begins to expose such assumptions.

Here we have a wonderful description of Sir John’s household at Barton Park: ‘Sir John was a sportsman; Lady Middleton was a mother. He hunted and shot, and she humoured her children; and these were their only resources. Lady Middleton had the advantage of being able to spoil her children all the year round, while Sir John’s independent employments were in existence only half the time. ‘

Here is Willoughby’s mode of courting Marianne: ‘If their evenings at the Park were concluded with cards, he cheated himself and all the rest of the party to get her a good hand. If dancing formed the amusement of the night, they were partners for half the time; and when obliged to separate for a couple of dances, were careful to stand together, and scarcely spoke to anybody else.’

Here is Willoughby on Colonel Brandon: – ‘”Brandon is just the kind of man,’ Willoughby said, when they were talking of him one day, ‘Whom everybody speaks well of, and nobody cares about; whom all are delighted to see, and none remember to talk to.”

“That is exactly what I think of him,” cried Marianne.

“Do not boast of it, however,” said Elinor, “for it is injustice in both of you. He is highly esteemed by all the family at the Park, and I never see him myself without taking care to converse with him.”

“That he is patronised by you,” replied Willoughby, “Is certainly in his favour; but as for the esteem of the others, it is a reproach in itself. Who would submit to the indignity of being approved by such women as Lady Middleton and Mrs Jennings, that could command the indifference of anybody else?”

“But perhaps the abuse of such people as yourself and Marianne will make amends for the regard of Lady Middleton and her mother. If their praise is censure, your censure may be praise; for they are not more undiscerning than you are prejudiced and unjust’.

“In defence of your protégé, you can even be saucy.”

“My protégé, as you call him, is a sensible man; and sense will always have attractions for me. Yes, Marianne, even in a man between thirty and forty.’

Elinor is a witty and independent minded heroine; not as lively as Elizabeth Bennet, but in some ways more discerning, so it is interesting that this book was the author’s first, initially written under the title of ‘Elinor and Marianne’ and edited and partly re-written in later years under its new title.

When the story moves towards the tragic – which happens all too soon – and Marianne’s inevitable disillusionment with her dashing, handsome admirer, the humour remains; but the tone is now tragic-comic:

There are the good-natured gossip Mrs Jennings attempts to console Marianne after she has learned of Willoughby’s engagement to the plain heiress Miss Grey: –

‘”My dear,” she said, “I have just recollected that I have some of the finest Constantia wine in the house that ever was tasted – so I have brought a glass of it for your sister. My poor husband! How fond he was of it! Whenever he had a touch of the cholicky gout, he said it did him more good than anything else in the world…”

‘Elinor, as she swallowed the chief of it, reflected that though its effects on cholicky gout were at present of little importance to her, its healing powers on a disappointed heart might be as reasonably tried on herself as on her sister…’

Elinor, of course, shares a mutual love with Edward Ferrars, who is being held to his engagement with the unprincipled and manipulative Lucy Steele. The smile that this episode gives us is a temporary respite from the stark tragedy of poor Marianne’s loss of her idol when Willoughby first reveals himself to be capable of acting as a vulgar fortune hunter.

More next time on the characters in ‘Sense and Sensibility’.

June 17, 2015

Classic Novels That Were Initially Rejected

Sometimes I can be a Merry Andrew (or Merry Andrea?). This is a Polyanna Post to encourage fellow self published writers who feel a bit downhearted; cast down by lack of public recognition, perhaps, or dismayed at unimpressive sales figures.

Sometimes I can be a Merry Andrew (or Merry Andrea?). This is a Polyanna Post to encourage fellow self published writers who feel a bit downhearted; cast down by lack of public recognition, perhaps, or dismayed at unimpressive sales figures.

The thing is, if you aim for any sort of originality, if you give reign to the imagination and strain the boundaries of convention and genre, a lot of people are going to be frankly puzzled. They won’t ‘get it’; or if they do, they may hate it.

If you write primarily to create something you believe in, rather than churning out four novels as a month or whatever it is that is recommended to keep you in the best seller lists at Amazon, then you have to run the risk of the work not receiving the recognition, the success of which all writers dream.

That doesn’t mean that it never will be successful; we hear all the time of writers who have broken the rules and made a success of it – and the irony is, that invariably means that they set off a trend. For instance, vampires were long out of fashion until the excellent Anne Rice revived them with ‘Interview with a Vampire’.

We are forever being told that ‘the market’ doesn’t like this or that, as though this said market is some sort of irascible god who must at all costs be appeased; in fact, a separate entity from the readers out there, who all have individual tastes and quirks.

Some of those readers might be the very people who will love what you have written, write rave reviews, set off a trend and lead to that elusive success and recognition.

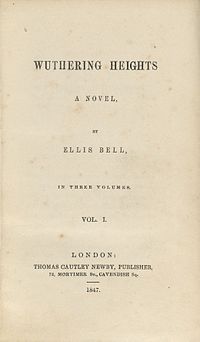

Though writers would rather have recognition in this lifetime, the example of Emily Bronte is still something of a balm.

She died early of ‘consumption’ only a couple of years after writing ‘Wuthering Heights’, with no inkling that her only novel would become a classic. Critical response had generally been hostile; though some acknowledged the power of the writing, all were disgusted with the dark picture of unrestrained destructive passions she depicted. This review from Graham’s ‘Lady’s Magazine’ is fairly typical: –

‘How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery. It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.’

Then, to venture outside the world of writing, Vincent Van Gogh must be the ultimate example of the artist who, commercially an utter failure in his lifetime, now has works that sell for millions.

Perhaps the collectors forget that Van Gogh’s initial reason for wishing to paint was to depict the sufferings of the poor and oppressed.

I always thought he never sold one painting during his lifetime,but here it seems I am wrong. He did sell one, ‘The Red Vineyard’.

However, to return to my main theme.

The website

http://www.literaryrejections.com/best-sellers-initially-rejected/

lists various classics which were initially underestimated by those in the publishing world, including: –

CS Lewis received rejections for ‘The Chronicles of Narnia’ for years, but continued to write.

Mary Shelley received numerous rejections for ‘Frankenstein’ until a small publisher agreed to print five hundred. They book only sold twenty-five in 1818, and it was not until 1831 and a third edition that sales started to improve.

A rejection letter to W Golding states that his book ‘The Lord of the Flies’ was, “An absurd and uninteresting fantasy which was rubbish and dull.’

DH Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chaterley’s Lover’ was rejected by every conceivable publisher in the UK and US, so that he had to self publish.

‘The Time Traveller’s Wife’ by Audrey Niffeneggar was rejected by twenty-five literary agents.

Even those who write more mainstream novels have often received a staggering amount of rejections. Agatha Christie five years worth of them. Stephanie Myers was comparatively lucky with her ‘Twilight’ . It received only 14.

Stephen King became so discouraged by trying to write the later best seller ‘Carrie’ that he threw it in the bin (his wife later rescued it). He went on to receive dozens of rejections by publishers before that final acceptance.

So, there are many indications that writers have much to gain by continuing to write what they love and believe in. whether it meets with rejections from traditional publishers, or commercial failure or not.

However, personally, I am not a purist; I see no reason why one shouldn’t churn out a bit of stuff now and then for fun which you wouldn’t put under your main pen name. That can be enjoyable; it might even meet with commercial success; but it isn’t the same as writing what you are inspired to write, which at those addictive times seems almost to write itself.

Those times of inspiration are priceless.

June 9, 2015

Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ Protagonists and Antagonists and More Farce

Lucinda Elliot, ascending platform:

Lucinda Elliot, ascending platform:

OK, so I am back again after escaping the clutches of that press gang in that time warp occasioned by my last post; here I am, restored to being a blogger sitting at my pc and typing up a geeky post and planning on making a cup of tea…

On protagonists and antagonists in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ then –(glances nervously about; no sign of anyone in old fashioned dress in the cyber hall). I have bored on about this before a fair amount.

Why does Gaskell have two male leads, and unsatisfactory ones at that, both a bit too inclined to the stereotypical, though in opposite ways? Why is one a cardboard hero type, one his shadow image?

It is almost as if Gaskell had drawn up a balance sheet and listed qualities on either side of it for Kinraid (clearly meant to be Sylvia’s notion of her ideal man) and Hepburn, something like this: –

Credit and Debit

Kinraid (credit) Handsome

Hepburn (debit) Plain

Kinraid (credit) Recklessly brave

Hepburn (debit) Cautious

Kinraid (credit) Sociable

Hepburn (debit) Withdrawn

Kinraid (questionable credit) Womaniser

Hepburn (debit) Invisible to women

Kinraid (credit) Jolly life and soul of the party

Hepburn (debit) Wallflower

Kinraid (credit) Raconteur

Hepburn (debit) Can’t tell a tale to

save his life

Philip Hepburn, then, is (in so far as past centuries understood these terms) totally uncool and a complete nerd.

And so on, with Hepburn’s only plus points being:

Kinraid Light minded (debit)

Hepburn Serious and some (questionable credit)

Kinraid Reputation for fickleness (debit)

Hepburn Unswervingly constant (credit)

These latter qualities are the ones that swing it for Hepburn with Sylvia in the end and lead to their reconciliation on his deathbed.

Here, however, I don’t want to explore that (general sighs of relief from small cyber audience impressed into cyber room). I’ve done that often enough in past posts) – but the question of why Gaskell, having posed the problem of having two opposing male leads, then went on to develop Philip Hepburn enough for him to come alive in the reader’s eyes, and left Charley Kinraid an oddly unrealised character.

I personally do not find Hepburn’s protestant ethic oriented, sexually repressed and grimly humourless persona remotely congenial; but I do concede the author makes a good job of bringing the character to life in the author’s eyes. I find his silence about his rival’s impressment, and not passing on his love message to Sylvia, so dismal that I could never bring myself to like him, but again the author does a clever job of providing excuses for him (Kinraid’s reputation as a heartbreaker as related by Coulson, etc; Bessy Corney’s insistence that she was engaged to him at the same time that he became engaged to Syvia, etc).

I personally do not find Hepburn’s protestant ethic oriented, sexually repressed and grimly humourless persona remotely congenial; but I do concede the author makes a good job of bringing the character to life in the author’s eyes. I find his silence about his rival’s impressment, and not passing on his love message to Sylvia, so dismal that I could never bring myself to like him, but again the author does a clever job of providing excuses for him (Kinraid’s reputation as a heartbreaker as related by Coulson, etc; Bessy Corney’s insistence that she was engaged to him at the same time that he became engaged to Syvia, etc).

Graham Handley comments: –

‘Seen in terms of depths and sympathy, Philip is Kinraid’s superior on every count. It must be admitted that the amount of space devoted to each is uneven, and that we know and live with Philip as we do not know and live with Kinraid; we see Kinraid, his tenderness and his heartiness, his stance and his impact, from the outside. We share Philip’s reactions, temptations, frustrations, anguish and later physical agony from the inside.’

This is the crux of the problem. Philip Hepburn is given vivid life through internalisation; Charley Kinraid is not.

This might be because, as Jane Spencer suggests, the whaler is not cerebral or given much to original thought anyway (even if he can spin a fine yarn), so that Gaskell does not think his mental processes would be of much interest to the reader.

Or it may be, as Graham Handley suggests in his excellent ‘Oxford Notes’ on the novel, because mystery, about his motivations, history and his thought processes ends an element of fascination to the character: –

‘His colourful appeal is more important than the qualities of his mind…Gaskell does not give him depth; what she does do, with tamtalizing art, is to leave us always in doubt about him.

Nothing stimulates an interest in character so much as mystery; the mystery of half knowing the characters we meet. Is Kinraid’s reputation justified? Is Sylvia the real love of his life? Is he, in fact, a man whose eye is always on the main chance? His career, and advantageous marriage, would tend to reinforce this view…’

John MacVicar (the literary critic, not the ancient villain) suggests that Charley Kinraid was in fact Elizabeth Gaskell’s original hero, as is indicated by the fact her original title was ‘The Specksioneer’ but that her focus of interest changed over time (especially as it took her an unusually long time to write this novel; perhaps so much as three and a half years) to Philip Hepburn, the original antagonist.

As nobody who reads this blog can fail to know, I find this novel particularly fascinating for many reasons; but it is also intriguing as one where the antagonist has in fact, taken over through having too strong a voice.

I know from my own experience that giving the antagonist too vivid a voice can be a danger.

While I make no claims to have depicted in the antagonist of my spoof historical romance ‘Ravensdale’ as vivid an antagonist as Elizabeth Gaskell’s Philip Hepburn, I did, nevertheless, depict his consciousness.

This was partly because I found the motivation of pure greed of so many of the villains of historical romances using the clichéd theme I satirized – Wild Young Viscount is framed for murderer by machinations of a Conniving Cousin and next in line to an Earldom –-unsatisfactory; why shouldn’t unrequited love play a part, battling with envy?

But, here I encountered a problem; a number of readers tell me that they find my antagonist Edmund Ravensdale, despite his duplicitous behaviour, more sympathetic, precisely because they had access to his thoughts as they did not for those of the frequently insensitive but generally straightforward and open-hearted Reynaud Ravensdale.

There is of course, that cliché , ‘to know all is to forgive all’. This is fascinating food for thought.

End of Sane Bit of Post: Now for some absurdity…

[A familiar figure in eighteenth century naval captain’s uniform enters at the back of the hall.]

Lucinda Elliot [Turns, outraged]: Well, would you credit it! Here’s that Charley Kinraid back again. After I had ripped his character to shreds last week. Some of these fictitious creations have got an incredible nerve!..[waxes thoughtful].But in line with ‘To know all is to forgive all’ come and have that tot of rum…

Charley Kinraid: Now, that is more civil, I’ll take that kindly… And what’s more, so will t’other Seven Most Annoying Heroes you used such hard words of in yon post, namely: – Georgette Heyer’s Marquis Vidal, Mary Renault’s Theseus, James Bond, Heathcliff, Charles Garvice’s Heriot Fayne, Viscount of Somewhere I’ve Forgotten and not forgetting Georgette Heyer’s Ludovic Lavenham, Earl of Somewhere Else…

James Bond: Bond, James Bond, 0000007 [I’m in semi-retirement].

Theseus [strides in, followed by half a dozen adoring war prizes]: By the Great Lord Zeus, not a robber left on the Corinth Peninsula.

Heathcliff [goes over to kick in window to make the decor resemble that at Wuthering Heights] Curse it all, I have no pity! Let the worms writhe!

Vidal: Damme, by Hell and the Devil! A Plague Take Me! What was I saying? Clean forgot what I was saying…Many hands make light work, mayhap?

Ludovic Lavenham: [shoots out lights in chandelier] Whose for a game of cards? [throws down talisman ring]

Heriot Fayne: I’ll play in the dark. Give me a gargle of whisky…What am I saying? I promised What’s-her-name – the heroine in my book, that’s right, Eva –-I’d reform.

Lucinda Elliot [shouting over racket]: I can only apologise to the reader for these continual interruptions; normal service will be resumed as soon as possible.

May 30, 2015

Some Complete Madness: A Post Interrupted by Progatonist(s) and Antagonist(s) from Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’.

Lucinda Elliot: Here I go on to discuss the issue of the role of the ‘Protagonist and Antagonist in Elizaeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’. I warn you, when I get started on one of my favourite topics I go and on, so this post will probably stretch into three…

Lucinda Elliot: Here I go on to discuss the issue of the role of the ‘Protagonist and Antagonist in Elizaeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’. I warn you, when I get started on one of my favourite topics I go and on, so this post will probably stretch into three…

[The last words are shouted above the noise of scraping sounds as cyber chairs are shoved back and not particularly huge group that constitutes the audience votes with their feet.]

Lucinda Elliot: Is anyone still with me?

Reader (pauses in doorway) Nobody sane, anyway (leaves, shaking head in disbelief).

[Lucinda Elliot spies three remaining people in curiously old-fashioned dress at the back of the cyber hall. These are a fine handsome naval officer with dark hair almost in ringlets who flashes his white teeth in a friendly smile, a plain-looking and rather drooping man of the respectable shopkeeper type, and a female figure shrouded in a heavy veil].

Lucinda Elliot: Kinraid, I give you fair notice I won’t speak as your friend any more than as Philip Hepburn’s. By the way, that’s a pinch from Dobbin’s speech to Becky Sharp in ‘Vanity Fair’.

Kinraid (still smiling) I’m well aware of that, Ma’am. You will say that I am a shallow opportunist. You will argue that as a naval captain, I must of necessity have in my later meteoric naval career have colluded with the press-gang, I once so violently opposed.

You will point out that: ‘In the French Revolutionary Wars, as it was often impossible for a ship to leave port without the captain having recourse to the press-gang, and as has been demonstrated by the research done for the ‘Hornblower’ novels it was often equally impossible for the captain to be scrupulous about keeping to its legal requirements.’

You will go on to say that as Speksioneer of the ‘Good Fortune’ , I reputedly shot dead two press-gang members – by the by, that’s reputedly, Ma’am; I made no confession; as you know. You will point out that I only escaped hanging for that through being ‘kicked aside for dead’. (winces at the memory).

You will then say my defenders must admit either that I was right to shoot them then, but wrong to collude with them as a Captain later, or that I was right to collude with them later and wrong to shoot them down then, but I cannot have been right on both occasions, as the press-gang invariably acted outside the terms of it’s legal remit. Am I right?

Lucinda Elliot: You are, mate. Then with regard to your supposed faithfulness to Sylvia during your three years’ absence at sea –

Kinraid: (suddenly notices the woman in veils huddled in the corner). Eh, yon’s not my missus Clarinda?

(The woman throws back her heavy veils.)

Kinraid and Hepburn (speaking for once, as one): Sylvia!!!

Sylvia: I think yon talkative female is right, for all her long words, and you both treated me ill. I didn’t know that about yon naval captain’s winking at the doings of the press-gang, Charley – I mean, Captain Kinraid, and I’m glad as I didn’t marry you to find that out later.

Kinraid (aside) Damn my eyes, but that’s fair saucy.

Hepburn: Ah, Sylvie. I made thee my idol. But thou made yon fickle, false Kinraid thine (glances at his watch). Time to count the takings in yon haberdashery.

Lucinda Elliot: Sit down, now you’re here.

Kinraid: (in a loud whisper) Yon females is main and grouchy. That comes of letting them out from under your thumb (to Sylvia). I don’t see how I used you ill, lass, I was faithful to you for the three years I was at sea after the press-gang took me.

Lucinda Elliot: I can easily disprove that feeble assertion.

Kinraid (starts guiltily) What? Ma’am, you can prove nothing. Yon author Mistress Gaskell wrote my character too fause ever to be tied down, except by the press-gang, never by readers. The evidence about my womanizing is hearsay. The evidence that I’m a murderer is hearsay. I just happened to fall in love with a pretty heiress,but what then? That was just luck, and I made her money as came to me fair and square over to her, so you can’t even prove I’m a fortune hunter. It all comes along o’ being on a whaler called ‘The Good Fortune’ amd gave me t’luck that pulled me though that day I heroically confronted yon press-gang (glances at Sylvia) and twas with me ever after.

Lucinda Elliot: You wouldn’t exactly have had shore leave as an impressed man, in case you made off. After you were promoted to warrant officer for good behaviour, you volunteered to go on that raid with Sir Sidney Smith, were taken prisoner, and kept in a French prison for two years until one Monsieur Phillipeux helped you to escape.

It is true that no sooner had you reached the UK – now promoted to Lieutenant by Smith in gratitude – than you took off to see the girl you had left behind you only to learn you had been deceived and Hepburn, witness to your impressment, had kept it secret (Hepburn sinks his head in his hands) .

Lucinda Elliot (kindly): Well, there’s no need to go through that painful, climatic scene of the novel again…I’ve always wondered, Kinraid; whatever made you think that ‘your Admiral’ could get you a divorce for Sylvia? A few decades later, even King Georges IV failed to get a divorce.

Sylvia (goes from being a ‘pale, tragic figure’ to being ‘as red as any rose’): Yon fause sod was after my body. His face was ‘all crimson with passion’.

Kinraid (clearly mortified): ‘Tis only a man’s nature, and little enough shore leave to socialize with suchlike amenable wenches as Newcastle Bess, Ma’am, if you take my meaning, you having a post Freudian understanding denied to the women of our own age.

Lucinda Eliot: I fully appreciate the extent of your libido…Then, you married the heiress Clarinda Jackson not eight months after this dramatic meeting.

Kinraid (looks intolerably smug) Love at fist sight(glances at Sylvia); on her side, anyway.

Sylvia: You forgot me in no time, for all you said as you’d marry none but me.

Kinraid (said generally) Well, ta has t’give t’lasses a bit o’ nonsense…

Hepburn (raises face from hands) Sylvie, I made thee my idol. If I had my life to live o’er, I’d worship my maker more, and thee less, and never come to sin such a sin against thee.

Lucinda Elliot: I daresay. Well, the poor girl made an idol out of Charley Kinaid. I suppose that’s why she got punished so severely, given Elizabeth Gaskell’s Christian perspective. That and her refusal to forgive Hepburn for so long. You know what I say in my review of the novel –

Hepburn: You were facetious on the topic, and it won’t do. You said, ‘Philip Hepburn worships Sylvia Robson, and finds dishonour; Sylvia Robson worships Charley Kinraid, and finds disillusionment; Charley Kinraid worships himself, and finds wife who agrees with him and a career in the Royal Navy’.

Kinraid (waves finger admonishingly) Naughty, Ma’am. You’ve been serving an honest sailor a scurvy turn in a-going about yon web, spreading lies about me most assiduous.

Lucinda Elliot: Well, I thought it was a good enough way of summing up a plot in a sentence. By the way, I’d like to take this opportunity to express my disgust with the whaling industry and the near extinction of the Greenland whale as a result (the others look uncomprehending).

Kinraid: She speaks more kindly of them savage fish than she does o’me. Typical o’ that sort of female, and no reasoning with them (begins to whistle ‘Wheel May the Keel Row’) Anyone care to watch me doing the hornpipe(begins to dance the hornpipe).

Sylvia: He is in fine spirits; it takes a deal to ruin t’ life of a man, but ah! I was let down by men as I trusted, and had no help for it.

Lucinda Elliot: You must leave Bella with Hester Rose, and go for a sailor, but – (seeing a spark in Kinraid’s eye) not on his ship.

Hepburn: Ignore such ungodly talk. Women was meant to stay at home and wait on us.

Kinraid (still dong hornpipe) :True enough,and it were a fair saucy thing to say out against me, but I don’t care a hang. Ma’am. You can’t pin anything on me, though you did a blog post and had my name down as number six in your ‘Most Annoying Heroes’. Fancy, putting my name down along o’ the likes of Heathcliff.

Lucinda Elliot (struck with an idea) He comes from Yorkshire! You could have one of your press gangs impress him. Now, that would be a fitting fate.

Kinraid (continuing to dance): I wouldn’t have the likes of him on my ship. Thieves and murderers yes, but not that fellow (glances at Sylvia) . Er –and I don’t have to do with them sneaking press gangs, anyhow. I’m the hero who won your love by resisting them, remember, my pretty?

Sylvia (tosses her head with a return of some of her old spirits) I don’t care if you do, Mr Clarinda Jackosn. I see all t’gossip about you was right at the end of t’ day. No doubt it’s true about you jilting Anne Coulson and being troth plighted to Bessy Courney at the same time as me, too.

Kinraid (still dancing): Yon Mistress Elliot has been filling your head with lies about me, and I won’t admit to any of t’ calumny. Vulgar gossip, that’s what it is. I’m boldly defiant, just like I was when I stood over them hatches to protect me crew from press-gang and shot down and near killed. Dost ta not remember how you worshipped me from yon heroic deed? (to Lucinda Elliot) Have you got any rum, Ma’am? I’m getting main and thirsty.

Hepburn: Well, I was heroic too; I saved his life at the Battle of Acre, and then our daughter’s, too. And it wasn’t very nice being blown up in that explosion.

Lucinda Elliot: We must have some order (hears a knock at the door).

Who’s that?

Press gang enter. We’re allowed to take women now,and we’ve come for these two. Mouthy couple of women, let ’em live up to all their talk of going to sea and learn their lesson. And that writer one’s a Jacobin. Ought to be made to serve King and country.

Hepburn: Oh, no, that’s not right, though that Mistress Elliot is fair unwomanly with that outspoken talk. Take me instead, though I’ve taken the King’s Shilling already.

Kinraid (stops dancing): Quick, down cyber hold and I’ll stand over yon cyber hatches and shoot ‘em down if they come near!

Dim witted looking press-gang member: Captain Kinraid, we’ll follow your orders, and only fire blanks at you.

Lucinda Elliot: Well, after this piece of madness, and if I haven’t been impressed into the French Revolutionary Wars through a time warp, my next post will be about the one I intended for this week, on how in Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ the protagonist and antagonist came to swap places…Aagh1! (leaps out of cyber window, followed by press gang).

May 23, 2015

Some More Ramblings About Protagonists and Antagonists

Continuing with my ramblings on the whole issue of protagonists and antagonists and point of view, there is the question of how much of an antagonist’s viewpoint should be revealed to the reader. How much sympathy for him or her can be engaged , before it becomes counter-productive, and the antagonist in fact becomes too much of a threat to the empathy with the ‘main character, the one the reader is supposed to be rooting for’. My apologies that I don’t remember the website on which I found that quote, and so can’t duly acknowledge it with a link.

Continuing with my ramblings on the whole issue of protagonists and antagonists and point of view, there is the question of how much of an antagonist’s viewpoint should be revealed to the reader. How much sympathy for him or her can be engaged , before it becomes counter-productive, and the antagonist in fact becomes too much of a threat to the empathy with the ‘main character, the one the reader is supposed to be rooting for’. My apologies that I don’t remember the website on which I found that quote, and so can’t duly acknowledge it with a link.

On a personal note, someone recently pointed out that I seem to have a natural sympathy for the bad guy, and I thought this unfortunately true; it probably accounts for why I would always like to be given more of the inner workings of the antagonist’s mind in novels. It also accounts for why I’m so often disappointed in these characters as ‘not fully realised ’. It often seems to me that in classic novels especially, they are intriguing but finally disappointing, and could have stronger motivation, and greater depths and complexity.

But perhaps here I am wrong, and the authors knew exactly what they were doing in not revealing too much of the antagonist’s point of view and particular motivations. After all, too empathic an antagonist can detract from sympathy with the protagonist.

I also read somewhere recently words to the affect that ‘the best favour you can do the protagonist is to have a strong antagonist’ (again, I’ve forgotten the name of the link to the website; oh dear; this looks like singular absent mindedness) .

That is true; but it is obviously a question of balance. For instance, with regard to one of the greatest plays of all time, I always found the character of Edmund in ‘King Lear’ fascinating; why is he so scheming and eager to do evil? How much is his treatment of Edgar motivated by jealousy and resentment at being ‘a bastard’ and so debarred from his father’s inheritance, and how much by what might be called ‘inherent badness? Or rather, giving in to the bead side of his nature, the evil streak that we all have?

Of course, the motivation and fascination of Edmund – who ends up being either directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of all three of Lear’s daughters and of King Lear himself, and of the mutilation of his own father – has been discussed at great length. Does he overhear the Duke of Gloucester when he makes purile jokes to the Duke of Kent about Edmund’s mother and the circumstances of his conception? Does he hear the Duke of Gloucester when he says that Edmund will be sent abroad again? This is largely a question of stage direction, and what original directions Shakespeare made which would no doubt clear the matter up have been lost.

But even when the villainies of a antagonist can’t be to some extent explained if not excused through this sort of ambiguity, Shakespeare’s antagonists are still fascinating. For instance, there is Laertes, fond son of that interfering and pompous Polonious, and fond brother of his sister Ophelia. I had to sympathize with him; Hamlet has unintentionally brought about the deaths of both, and Laeertes’ smouldering hatred is fully understandable; Hamlet’s outburst at Ophelia’s funeral, where he accuses Laetrtes of ‘whining’ and stridently insists, ‘I loved Ophelia’ is enough to provoke a frenzy of violent vengefulness in any fond brother.

The infinitely less gifted but still innovative pioneer novelist Samuel Richardson found himself in unforeseen difficulties in his portrayal of his arch villain, Robert Lovelace in ‘Clarissa’.

There is no doubt that the moral (if unconsciously hypocritical) Richardson intended Lovelace to be a complete villain and incorrigibly bad. He is a misogynist, scheming and underhand almost beyond belief and to the point of sabotaging his own self interest and finally, a rapist.

However, Lovelace is presented through his letters as so lively, playful and witty, that it is hard not to enjoy him and his appalling immorality up untitl the point when Clarissa’s sufferings become so severe, his duplicity so pointless and relentless, that the reader is finally disgusted even before the rape.

Here he is, for instance, unkindly singling out another household’s servant for ridicule to beguile the weary hour: –

‘O Lord: said the pollard headed dog, struggling to get his head loose from under my arm, while my other hand was muzzling about his cursed chaps, as I would take his teeth out. ..’

Lovelace’s prose is always racy and vivid; it is impossible not to laugh at his awful antics.

His behaviour, of course, is self defeating; this does make for a weakness in his motivation. After all, as the proud heir of an aristocratic family, he needs an heir. If he constitutionally despises all women, and is motivated by an evil urge to prove that all women are lascivious and fair game, why does he think he can prove it by raping Clarissa when all his attempts at seduction have failed? That is surely an admission of defeat.

In fact, Lovelace admits as much at the end, so the unfortunate Clarissa experiences a moral triumph beyond the grave as he dies in horrible agonies from the wounds inflicted by Captain Morden in the duel she sought so hard to prevent: ‘Blessed …Let this expiate.’

From a practical point of view, Lovelace would have done far better to have married Clarissa after he had tricked her into literally running away with him, and made her life a misery from then with rakish ways and constant unfaithfulness; that seems to me an altogether more satisfactory conclusion to the story than Richardson’ s long drawn out melodrama.

However, this is to wander from the point, which is that in depicting so charming and high-spirited an arch-villain as Lovelace, Richardson encountered unforeseen difficulties. As the volumes were produced, too many of his readers became too fond of Lovelace and insisted on seeing him as treated too harshly by both the author and his virtuous, but unfortunately stiff and humourless heroine, and suggested that the best thing all round would have been for Lovelace to marry Clarissa after the rape, thus ‘making amends’.

Of course, that was the conventional wisdom of the eighteenth century, disgusting as it seems to us, and in having his heroine reject him, Richardson was making a moral stand (as Gaskell was later to do in ‘Ruth) against this view that a rapist or even a mean seducer in marrying his victim somehow put matters right.

Because of the charm of Lovelace’s presentation, many critics and readers ever since have adopted an over sympathetic view towards this arch-villain, and this stimulated Richardson to write indignant prefaces and additions refuting such claims. Yet, however, much Richardson may have told his audience how his novel should be read, many persisted, as he saw it, in wilfully misunderstanding his intention.

And here, as I’ve said before, we come to a problem; as authors we can do our best to portray a character in such a way as to evoke a particular response. But when that book is published, it is finally up the reader to decide. They may find our antagonists altogether more intriguing than our protagonists, and the more human, complex and beguiling we make our antagonists, the greater the danger of that.

In my next post, I’m going back to one of my favourite novels to explore some problems when writing a novel where the antagonist, through sheer force of presentation, takes over from the hero as a protagonist and a main focus of interest – yes, it’s Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lover’s’ so you have been warned.

May 11, 2015

The Inner Life of Characters in Classic Early Novels – Some Musings on Rinaldo Rinaldini and Richardson

Recently, I did some reading, and re-reading of several ‘classic’ novels of varying merit – Joseph Conrad – brilliant, though not to be judged taking into account the awful racist assumptions of his times – Elizabeth Gaskell – generally very good, sometimes brilliant, often uneven, Christian Auguste Vulpius – an early groundbreaking novelist, melodramatic beyond belief, but certainly capable of delivering a stirring read, often of the So Bad It’s Good Variety and also Charles Garvice – vastly inferior to them all, generally purely terrible, though occasionally stirred into delivering a decent passage or two.

Recently, I did some reading, and re-reading of several ‘classic’ novels of varying merit – Joseph Conrad – brilliant, though not to be judged taking into account the awful racist assumptions of his times – Elizabeth Gaskell – generally very good, sometimes brilliant, often uneven, Christian Auguste Vulpius – an early groundbreaking novelist, melodramatic beyond belief, but certainly capable of delivering a stirring read, often of the So Bad It’s Good Variety and also Charles Garvice – vastly inferior to them all, generally purely terrible, though occasionally stirred into delivering a decent passage or two.

This got me on to thinking about the whole issue of what you might call the mental life of characters. Is this a modern phenomenon?

Gaskell, in fact, remarks in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ (Sorry, everyone; here I go again, quoting ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ ; have I got a share in the royalties or something?) that self awareness, self analysis, is a comparatively modern concept (it is also, of course, to some extent connected with personality; but that is a different matter). She was far closer in time to the era of the French Revolutionary Wars in which she sets this novel than we are, of course, and she has some memory of the mindset of the generations who preceded her. Their approach to life was then, markedly different from that of the ‘educated’ people of her own day.

Her character Philip Hepburn, is self-aware – in fact, quite self-conscious in the uncomfortable sense of the word – whereas the other characters in the novel are not.

uncomfortable sense of the word – whereas the other characters in the novel are not.

It is an irony that reflective as he is, Philip Hepburn still behaves dishonourably. That compared to modern people of a comparable intelligence he is on the whole less aware of himself and his motivation probably saves him from less stress and moral conflict than a modern thinking person in the same position would suffer.

She saw this lack of reflectiveness as an aspect of this former age, and suggests that our increasing self-awareness is not necessarily accompanied by a gain in superior moral insight, though it is accompanied by a general decrease in spontaneity, of exuberance, of vivid existence in the present. Presumably Philip Hepburn is meant to be an indication of this. His love interest the unthinking Sylvia, and his bitter rival the exuberant, opportunistic Charley Kinraid, are presumably meant to be of the old, extroverted type of personality.

This is a fascinating insight. When novels began to be written, as often as not in the author offered very little in the way of a character with a mental life. I admit that I haven’t yet read Sterne – but did read somewhere ( as I said earlier, geek or what?) that a lack of consistency of character and internal dialogue are drawbacks to his writing.

For instance, in Vulpius’ sensational story ‘Rinaldo Rinaldini’ (for which he claims a moral basis, which I find questionable or decidedly unexamined) we do not hear much of the hero’s thoughts. We are told that he is anguished by his having drifted into a life as the ‘Captain of Bandits’ (that translation does make me laugh; it sounds like the Captain of the First Eleven!), and that he is given to dismal reflection on it, especially after he meets and falls in love with the virtuous Aurelia (and with good reason; when she finds out who he is, she screams and faints).

He does go in for some moral reflection on his situation – but typically, these are expressed externally, as in the dialogue I quoted in my recent blog post on the novel; for instance, he sings a song, accompanying himself by guitar, about this moral quandary (I assume he is meant to have written this as a lament rather than to clarify his feelings).

Before going on, I have to give a bit of background and say that one of the inconsistencies of this story is the time frame. From the point of view of Rinaldo and his fellow robbers, only a short while has passed between his finding out that Aurelia’s great uncle, alarmed at her having come to know him, has had her sent on her way to join a convent, and his coming on her as a bitterly unhappily married and disillusioned wife to the wicked Count Rozzio. From her point of view, months at least have passed.

Rinaldo had positioned his men to abduct her, but instead they had to fight off encroaching government troops, who decimated the robber band. Shortly after this he took up with the devoted gypsy girl Rosalia and meeting with the few survivors of his old band, set up a new one while continuing to protest that he wished to escape the country and his way of life.

Then finding an unhappily married Aurelia in Baron Rozzio’s nearby castle (there are lots of convenient co-incidences in this tale), he is insulted by the wicked count and his toadies and swears revenge. Although they evidently live in different time schemes, this doesn’t stop Rinaldo from deciding to free Auerelia at once and he sets his men on the castle.

As usual, when the men who have previously treated him with contempt discover who he is, they fall on their knees. Aurelia swoons, and on recovering consciousness, pleads with him to be ‘As kind as you are terrible. Deal with me honourably…Abuse not your power, nor make my yet unspotted name the jest of mankind.’

One assumes from this that she is concerned that Rinaldini might abduct her by force, and one wonders if he did intend that, as his response is to sigh: ‘Now I feel what I am!” Typically, we aren’t told exactly what his plans were, if he, a man of action rather than thought, knows himself.