Lucinda Elliot's Blog, page 25

November 12, 2015

Rules Writers Must Not Break and What Do J S Bach, Margaret Mitchell, Zane Grey and Louis L’amour Have in Common?

There’s a few things I’ve been wanting to say as part of some post, but I can’t think of any suitable one, so I’ll just mix them together in a miscellaneous post about market trends and rejections.

There’s a few things I’ve been wanting to say as part of some post, but I can’t think of any suitable one, so I’ll just mix them together in a miscellaneous post about market trends and rejections.

The first thing is a story to encourage those who are trying to create something special, and meet with incomprehension/dismissal/harsh criticism.

It’s about the baroque composer, J S Bach himself and ‘The Brandenburg Concertos’ (well, they weren’t known as that at the time). They’re regarded as masterpieces today, of course. They’re among the pieces I play for inspiration – on the off-chance that anyone’s interested – ( the sixth is particularly good for inspiring a high minded sort of detachment) but I don’t think that latter recommendation would particularly impress Bach.

Anyway, when he sent them off to the Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg, along with a fashionable French dedication in 1721, the Margrave neither acknowledged their receipt, nor ever had them played.

It seems that there is some excuse to be made for this lack of appreciation of this presentation with such exceptional pieces of music. Bach had promised to give him a piece of music demonstrating his talent when they met two years previously, and had taken long enough to get round to it. He may even have sent the pieces as a sort of eighteenth century CV, as he was looking for another post at the time.

Another reason for the lack of appreciation may have been that these pieces were designed to suit the versatility of the orchestra which Bach had in Clothen rather than that of the Margrave. It seems the pieces were unusually diverse for the orchestras of those times.

However, for anyone who has had the deflating experience of having that cherished creation dismissed or frankly ignored, that is an encouraging story.

Has anyone heard of J S Bach and his ‘Brandenburg Concertos’?

Has anyone heard of the Margrave of Brandenburg or does anyone now care two hoots about his view of the worth of what are now called as the Brandenburg Concertos? (here’s a picture of him, anyway).

The other story must have been incredibly deflating for the author in the receiving end, but is horribly funny.

A publisher wrote in response to Zane Grey: ‘You have no business in trying to write and should give up’.

Almost as discouraging must have been Margaret Mitchell’s 38 rejection letters for ‘Gone With the Wind’…

But that is not quite as bad for the 200 received by Louis l’Amour (I didn’t know there were that many publishing houses even in the US, and decades ago; but perhaps they were for several different books).

I personally am not a great admirer of westerns, or for that matter, of ‘Gone With the Wind’, which was one of the many novels I found on that Aladdin’s cave of a maze of bookshelves back in that great isolated house in the Clwyd Valley, into which I used to delve on winter’s evenings.  But the point I am making here is that a lot of people do admire the work of these writers; they may not be comparable to the great JS Bach as regards originality or mastery of their craft; but they had a vision and they stuck to it in the face of all discouragement; and that takes commitment.

But the point I am making here is that a lot of people do admire the work of these writers; they may not be comparable to the great JS Bach as regards originality or mastery of their craft; but they had a vision and they stuck to it in the face of all discouragement; and that takes commitment.

I have said before that too many author’s websites seem to give facile, bland advice: anodyne advice, in fact. Do your market research, and write for a particular type of ‘average’ reader (ie, six foot, hairs on the back of his hands, reclusive castle dweller in Transylvania; likes stories about his ancestors) and write accordingly.

Above all, do not break the rules.

It’s these supposedly hard and fast rules that I object to (and yes, I did write a post on this very point not so long ago). The supreme irony is, that the successful authors you are advised to imitate on these How To sites, DID break the rules (and I’ve just broken one myself; never write in capital letters to emphasize a point; people will think that you are semi literate).

Nobody wrote about dystopias when George Orwell wrote ‘1984”; nobody wrote about boarding schools when a certain best-selling children’s writer decided to give a new slant on one; vampires were old hat when Anne Rice decided to write a new take on them.

If they had ‘properly researched the market’ they wouldn’t have written what they did (and so set new trends) at all; they would have played safe, and possibly lost their vision and written something derivative.

Someone in the writing business warned me some time ago on the hazards of having multiple points of view (as I tend to in my novels), let alone having more than one ‘main character’ on the grounds that ‘these days, people only want limited points of view and they want to know who the main character is, and who to root for, early on’.

This advice was constructive, and based on her best information; but I disagree with it. I think it is too restrictive. And given those writers who broke certain hard and fast rules and so set new trends, isn’t it quite likely that someone will come along and flout those particular rules and write something original that also sells well, so that suddenly everyone will be breaking them?

Suddenly, having a restricted point of view may be ‘totally outmoded’.

I came across a How To book on writing recently, published in the eighties. It fell open at this page. ‘Please don’t give your characters names that reveal something of their characters; that’s pathetically old-fashioned.’

And so it was, back in 1985. That was another trend overthrown by that nameless writer of children’s fantasy.

In case any regulars get a feeling of déjà vu, yes, some months ago, I did publish two posts that touched on different points covered in this one, but I wanted to approach the topic from a slightly different angle.

Dracula climbing down the wall of his castle, from a 1916 edition of the work.

Got to go now. I’ve just got a communication from that lonely soul in Transylvania, saying he offers residential courses for writers. He says that ‘Time wasters need not apply. Must be free of blood disease; testing obligatory’. He offers spectacular views and the course is for health fanatics, and culminates in an exciting climbing excursion, of the sort pioneered, he says, by Jonathan Harker. He promises: ‘This is not just another writing course; this one will transform your whole existence and view of life’.

Hmm. I had glandular fever as a youngster; would that disqualify me? He says I can have a discount. Should I apply?

I have always wanted to go to Transylvania….

November 5, 2015

‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ by Anne Bronte; Structure and the Role of the Antagonist

When re-reading ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ I was struck by many things. I hope I don’t annoy the spirit of Anne Bronte by making a comparison with the structure of ‘Wuthering Heights’ as a beginning, though this is not the invidious comparison of the sort that were until recently usually made between her work and that of both her sisters’.

When re-reading ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ I was struck by many things. I hope I don’t annoy the spirit of Anne Bronte by making a comparison with the structure of ‘Wuthering Heights’ as a beginning, though this is not the invidious comparison of the sort that were until recently usually made between her work and that of both her sisters’.

What I want to say is that I had forgotten it was a story within a story. I remembered that it contains a story within a story, just like ‘Wuthering Heights’.

The tale starts with Gilbert Markham, a young man who is a gentleman farmer and wishes he was destined for a less earthy occupation, who is vain and infatuated with the even more vain coquette Eliza Millward, the local vicar’s daughter.

When the mysterious young widow Helen Graham comes to the area, he is at first repelled by her cold, discouraging manner and refusal to reveal much of her personal history.

She even flies into a temper when he discovers a portrait of a handsome, sensual looking young man, whose chestnut curls tumbling over his forehead lead Gilbert to conclude that ‘he thought more of his beauty than his intellect.’ The bright blue eyes show a glint of mischief.

Of course, the reader guesses who this must be long before Gilbert…

The story within a story is the tale that Gilbert reads in Helen’s journal, when after many misunderstandings she at last confides in him.

It recounts the tale of Helen’s disasterous marriage to the charming, lively and enticingly attractive Arthur Huntingdon. This match, based mainly on their mutual physical attraction, is, as Josephine Macdonaugh comments in my Oxford World Classics edition, is as doomed to unhappiness as would be Gilbert’s to Eliza, should he marry her.

Some readers and editors claim that the ‘epistolary method’ creates a distance between the narrator and the reader. I can’t say I have ever found that myself. I found the account of Helen’s disillusionment with Arthur and the failure of their marriage as he gives way to the temptations of alcohol and philandering, recounted as it is in occasional journal entries, tinged with a sense of tragic inevitability precisely because the reader already knows that it ended in Helen’s flight from the marital home.

The second feature that struck me most was a dissimilarity with ‘Wuthering Heights’ in the striking contrast between the appearance of their antagonists—Heathcliff and Arthur Huntingdon.

These are almost completely opposite. Heathcliff is, quite frankly, a miserable so-and-so, so self-pitying that I have always been completely at a loss as to how any reader can find him appealing or sympathetic (and that is leaving aside his unfortunate habit of bullying women and children). Although he has cheated the Earnshaws and the Lintons out of their inheritances, he can find no pleasure in the money he has come by. Instead of dining well, this miser takes porridge for dinner and begrudges offierng a cup of tea to visitors so that the young Cathy hesitates to offer a cup.

He is wholly anti social and we never hear that he drinks or indulges himself in any way; his existence is as Spartan and joyless as a doctrinaire puritan’s.

I’ve written just what I think about Heathcliff as a romantic hero before on this blog and discussed it on a Goodreads thread, and there’s no need for me to repeat myself here.

Here it is, for anybody reading this who might be interested:

https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/1019195

Here, I want to point out that Arthur Huntingdon is his complete polar opposite. He is the life and soul of the party, full of blithe mischief. He does much harm, but this is through carelessness, vanity, self-indulgence and a lack of moral values rather than through active malevolence of Heathcliff.

Arthur at ‘Wuthering Heights’ would be about as out of place as a doormat that played a jolly tune of welcome.

He betrays almost everyone he knows – Helen and his unfortunate friend Lord Loughborough, whose life he embitters through seducing his wife – more than anyone. Yet, as Marianne Thormalen comments in her intriguing article, ‘The Villain of Wildfell Hall; Aspects and Prospects of Arhtur Huntingdon’ the long term consequences of his destructive life, are, like those of Heathcliff, short lasting. Once these two antagonists have gone, peace and normality is soon restored.

While they are alive, they determine the action through force of character; but their lives are short and their reign of influence transitory.

Heathcliff corrupts by hatred and fear; Arthur through wicked charm and careless indifference to the moral consequences of his wrongdoing.

Anne Bronte was, of course, her sister’s chief confidante in their weaving of the fantasy world of Gondal. I think it very likely that they discussed, not only the fate of non repentant sinners – neither, clearly, believed in damnation – and the long term earthly consequences of their wrongdoing. Certainly, the poetry of each notoriously touches on these points, as does the text of ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’(but more about Anne Bronte’s beliefs about Arthur Huntingdon’s final destination next week.)

Another thing that struck me was, yet again, how great a role unconscious influences play a role in our writing and in our creation of characters.

The characteristics of Arthur Huntingdon had largely slipped my mind in the years since I read ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’. When I decided that I wanted to create in ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’ not a brooding, savage vampire but a jolly, sociable one, I did not consciously think about Arthur Huntingdon, or draw on his characteristics; but the similarities are strongly marked, down to the ‘mischievous twinkle in the eyes’ and the habit of drinking to excess.

I am pleased by that; it’s a fine thing to be influenced by classic English Literature; however, I do have to say that there is a strong resemblance also, to Disney’s John Smith in ‘Pocohontas’. That swagger and gallows humour…Yes, well, we see our characters everywhere…

As Monsieur Gilles, Émile starts each day with ‘a good swill of red wine even before he chewed a piece of bread’ to make himself face each hateful day.

Like Arthur Huntingdon, the wicked and godless Émile Dubois wishes to marry a ‘good angel’ whom he hopes will convert him to good behaviour without too much effort for himself.

But Émile is far more cerebral than Arthur Huntingdon and has a serious-minded streak. His desire to reform is a little more serious, and his love for the innocent and devout girl he marries a good deal deeper than Arthur Huntingdon’s for his.

In the sequel I am s-l-o-w-l-y writing, I plan to return to this theme, apart from introducing some rubber monster men, Kenrick and his right hand man Arthur Williams return, and some more of Émile’s cousin Reynaud Ravensdale.

October 30, 2015

A Real Life Haunted House

Last year I swore I’d do an Halloween post next autumn, as appropriate to a blog on Gothic.

Last year I swore I’d do an Halloween post next autumn, as appropriate to a blog on Gothic.

This year I’ve had some nice conjunctivitis; that’s put me behind a bit, what with flinching away from the brightness of the pc screen as from an instrument of torture, but I’ll do a quick one now, as it has occurred to me; I can recount an entirely appropriate story just by drawing on my family of origin’s experiences in one of the isolated great old houses my parents used to renovate, back in the days before it became fashionable.

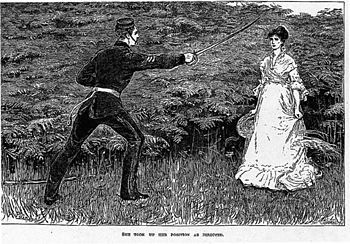

The most Gothic of the lot had to be the now demolished Plas Isaf near Llangynhafal in the Clwyd Valley, North Wales (demolished not because of the ghosts, but because a philistine builder wished to put some new build homes on the site; these have yet to be built, as he ran into difficulties with planning permission). All that remains is a empty site with an oddly cold draught coming out of it, even in the heat of a summer’s day.

The pretentious part of the house was not that old; the grand part was Victorian Gothic. This had been added to the remains of an eighteenth century foursquare type of structure. I personally found the grandiose aspirations of the architecture of the one clashed with the solid functional appearance of the other. However, I can only suppose the original architects thought otherwise.

This house was nothing like as isolated as the previous one we had lived at, seven miles from Barnstaple in the then entirely cut off North Devon. But that was a beautiful Regency Rectory complete with long windows that would have baffled any ghost.

Plas Isaf, my comparison, was gloomy inside despite the size of the windows. The most piled up fires blazing in the fireplaces never seemed to make any impression on the chill of the rooms. As twilight fell, and the song of the birds silenced, and the owls began to cry and the tickings and stirrings and the sounds of the night took over, it always began to seem most isolated indeed.

It had a suitably melodramatic history, certainly. An older ‘substantial’ house had been built on the site, and subsequently largely burnt down, with only a part of it used in the creation of the modern building. The family of Leicester, who commissioned the building, had subsequently gone bankrupt, and the property had been betted away, reputedly at a railway station.

A son of the family had died of ‘consumption’ in a sort of Victorian one storey villa with a steep red tiled roof next door. It was connected to the main house by an ornamental conservatory (one of the finest features of the house). My parents let that out as one of the holiday cottages.

For some reason, the people who came to stay in that particular one, at first full of enthusiasm for its striking architecture, generally had to cut their holiday short, with tales of births and sickly grandmothers.

I can’t say I liked the atmosphere of that place myself. There were a lot of carved woodwork screens, and I always had the impression that someone was observing me from behind them…

When we first moved there, often, when my father and sister were out of the house, I would leave my mother in the kitchens and run down to the other end of the house to get something. As I stopped to collect whatever it was, I was puzzled to hear the sound of the footsteps of a woman in heels walking briskly upstairs. For a long time, I was foolishly puzzled as to how my mother, who struck me as slow moving in the manner of all adults, had reached that part of the house only a few moments after me.

It took me some time to work out that those footsteps were, quite simply, not my mother…

My parents were committed atheists; they were quite religious about not attending church. They didn’t believe in ghosts as a matter of principle, but my mother was forced to admit that some strange things happened. For instance, there was the tendency of the upstairs front bedroom to light up in the middle of the night.

She ascribed the cries of ‘fire!’ she occasionally heard to jackdaws, and the semi transparent form of woman she saw near the old kitchen quarters as a trick of the light. She said that the disembodied footsteps we all regularly heard were echoes caused by something or other (I forget what).

The same with the disembodied voices.

My father laughed aloud at the horror that my sister and I had over strange, dragging, whirring noises that regularly sounded in the middle of the night along the main corridor in the older part of the house.

At first, I put it down to my clock. Then I realised that it was coming from outside the room. Not only that, but it seemed to have come to a stop outside my door. It took some time for me to work up the courage to look out; however, being more scared of being a coward than of ghosts (which I was sternly told did not exist), I finally forced myself to get up, switch on the light and go to open the door.

Of course, there was nothing to be seen; the noises stopped as by magic. All was still. I went back to bed, and the noises began again at once, seemingly moving to pause by the door of my sister’s bedroom, and move on again.

If possible, we liked to avoid having a bath in the bathroom under the tower. There, you would be lying still, and the water would start, unaccountably, to move, to slosh up and down with increasing violence, until you were sitting in a bath with the effects of a wave machine.

‘Vibrations,’ said my parents….

The haunted lavatory next door to that bathroom really was taking it too far. You always felt eyes on you in there, which seemed to indicate a sordid type of spectre.

Those were a few of my impressions of the ghost life at Plas Isaf

I have to say that the combination of reading ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’ by Gaskell while sitting up late by the dying fire in the old library so unnerved me that I ran through the house at top speed to bed.

So, this Halloween, I am quite grateful to be living in a prosaic house.

October 14, 2015

‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ by Anne Bronte; An Underestimated Classic

A reader of this blog was flattering enough to want my opinion of Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’. I was delighted, as that was a novel that fascinated me, and it gave me a reason to bring it up on my long and dusty reading list ( a second attempt at ‘Moby Dick’ was supposed to be next).

A reader of this blog was flattering enough to want my opinion of Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’. I was delighted, as that was a novel that fascinated me, and it gave me a reason to bring it up on my long and dusty reading list ( a second attempt at ‘Moby Dick’ was supposed to be next).

I first read this longer ago than I care to admit, when I was in my early twenties. I remember being impressed with it then, and thinking that for powerful writing, and Gothic effects, it is easily the equal of either ‘Wuthering Heights’ or ‘Jane Eyre’; why was Anne Bronte so underestimated as the least gifted of the Bronte sisters?

I think the introduction of the edition I am reading 2008 by Oxford World Classics by Josephine McDonagh, gives one very good reason. Anne Bronte was the youngest child in the family. Older siblings are not exactly notorious for giving a fair estimation of the capacities of the youngest, not as a conscious piece of injustice, but through an unquestioned attitude which never concedes that youngest sibling can be anything but comparatively undeveloped, and can often fail to take into account the age of the youngest when certain remembered events took place (I couldn’t possibly have experienced the position of youngest sibling myself, by any chance?).

There is an anecdote about the reactions of the young Bronte’s when each chose one of Bramwell’s set of toy soldiers, the imaginary adventures of whom would lead to the construction of the fantasy worlds of ‘Gondal for Anne and Emily, while Bramwell and Charlotte created ‘Angria’. Charlotte and Emily chose fairly striking figures; Anne selected a little, unremarkable one; this seems to be taken to indicate generally less striking taste on Anne Bronte’s part and perhaps a wish to take the place of a follower in life. Ms McDonagh points out that Anne was six years old at the time.

Little is known about Anne’s life; the little we do know of her is often from the recollections of her fond but condescending older sister Charlotte, and it seems that she has been judged accordingly as a writer of works less strong, as something of an afterthought amongst critic s of the Bronte’s.

More recently this has been belatedly challenged, and now I come to the second reason why I think that Anne Bronte’s work has been underestimated. ‘Agnes Grey’ her first published work ,was a short, vivid and painfully believable (because based on personal experience) account of a sheltered young girl’s short career as a governess. It was not a ‘romantic’ novel (in the old sense) with a gothic hero, but a realistic one.

It is shocking in its depiction of dismally indulged, unfeeling children and astoundingly insensitive parents who saw a governess as a drudge devoid of human feeling; but it is not gothic in tone. There are no rambling, derelict mansions, brooding anti heroes or haunted attics, wild passions or captive maidens such as one encounters in ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Jane Eyre’. It is a sobering (if you’ll forgive the expression, in the light of what is to come) tale, and one with a strong moral point (all the Bronte sisters were strongly moral in their differing ways).

But ‘Agnes Grey’ could not have the impact on the critics in the manner of Charlotte and Emily Bronte’s Gothic novels which were also published in 1847, and Anne Bronte was accordingly seen as the more conventional, milder and narrower writer.

‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ was thought by critics to veer in the opposite direction. ‘Acton Bell’ was fated as a writer to fail to please. Critics, though retaining the belief that she was still the least gifted Bronte, were disgusted at the depictions of the wild drunkenness and moral degeneracy depicted within, and in general took a low view of the literary merit of the novel.

Anne Bronte here depicts the life of a devout but healthily sensual girl from the gentry who in the late 1820’s falls for the charming and high spirited, hard drinking Regency rake Arthur Huntingdon. She marries him against the advice of the aunt who has raised her. This aunt, embittered by her own experience as the wife of an unprincipled man, urges Helen to marry the appropriately dubbed Mr Boarham and live an existence of dull respectability. Anne Bronte makes an excellent job of managing to portray Helen’s physical attraction to the wicked Arthur for all the limits of Victorian text.

Helen believes that she can use her influence to reform Arthur; this scheme will, of course, only work if Arthur truly wishes to change his lifestyle himself, particularly as Helen in marrying him gives up all her legal rights.

She underestimates the hold that drink and his egotistical joy in his libertine conquests has over him, and unlike the outcome apparently foreseen by many a romantic historical novelist who blithely marries off a heroine to a Regency rake who claims that he will change now that he has met the love of his life, Helen gradually loses her respect for Arthur as he sinks into drunken debauchery, while what he sees as her joyless hectoring quickly extinguishes his passion for her.

The disgust that the critics felt for the brutality of some of the scenes of riotous drunkenness in the novel seem to me to indicate Victorian repression. They seem as appalled as much as anything by the preoccupation that the author might possibly be a woman, and if so, what sort of a woman could witness, let alone reproduce in a novel, such appalling excess?

Of course, Anne Bronte herself is appalled by drunkenness and squalid debauchery; while her (startlingly modern) ‘Universalist’ outlook was that of an enlightened Christian who had no belief in eternal damnation, through the lips of her heroine, she expresses the strongest moral disapprobation of such brutal excesses; but for the critics, the unimpeachable Christian moral of the story was nto sufficient to make up for its shocking content.

Charlotte Bronte herself did not consider ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’ worthy of publication and excluded it from the posthumus editions of the novels of her sisters’ which she subsequently to bring out.

I am one of a growing number of modern readers who consider that Anne Bronte was generally underestimated author of strong and impressive texts and fully the equal of her more celebrated sisters.

I hope to write more of this in subsequent posts as I read through the novel, but for now, I would like to remark that the note of startled horror which Anne Bronte brings to the drunkenness of Arthur Huntingdon and his friends was to some extent the product of her own age.

Views on how far it is socially acceptable to be obviously drunk in public vary between ages. In the eighteenth century, members of both houses of parliament were sometimes so drunk that they would vomit, and I gather that across the classes, drunkenness was far more socially acceptable up until well into the nineteenth century.

A great many long suffering female relatives of all classes accepted that frequently male family members would drink until ‘their ideas became confused’ (to quote Elizabeth Gaskell). Beer (and rather stronger beer than is sold nowadays) was commonly taken instead of the unsafe water, and while the upper classes took port and brandy the lower classes drank gin.

Helen is in many ways a delightful heroine, spirited and compassionate, lively and opinionated; Ms McDonough quotes the remarks of an early critic, who comments that Helen, with her modern disgust at drunkenness, is slightly incongruous amongst the Regency rakes. The critic comments that it is as if Jane Austen had entered into an earlier, coarser age. I think that this critic to some extent has a point; a woman from their era would have been too familiar with male drunkenness to be shocked at encountering it. Anne Bronte probably was incorrect in dismissing the more tolerant views of the earlier age towards excess. However, that would not mean that a wife of spirit would necessarily find it acceptable as a regular habit in a spouse, and Helen is every bit a woman of spirit.

Clarissa, Richardson’s heroine of a hundred years earlier, does not have to struggle against drunkenness in Lovelace, because drunkenness is not one of the excesses in which he indulges, but given the sharp homilies she repeatedly gives him on all his other failings, we may be sure that had it been one, that most thoroughly Georgian of heroines would have taken him to task for that too.

And on the sheltered gentility of Jane Austen’s heroines, that can be overestimated; they too, were from the Regency age. Elinor from ‘Sense and Sensibility’, though decidedly from the respectable gentry, assumes when she meets an incoherent and emotional Willoughby that he must be drunk. She calmly advises him, ‘Your errand will more properly be conducted tomorrow’.

Next week: More reflections on ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’.

October 6, 2015

More Thoughts on Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

Having finished Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’, I still find myself puzzled by exactly what the author was trying to achieve, and feel more then ever convinced that in the nineteenth century, authors often started writing a novel unsure what they were trying to accomplish, and often ended up with something else.

Having finished Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’, I still find myself puzzled by exactly what the author was trying to achieve, and feel more then ever convinced that in the nineteenth century, authors often started writing a novel unsure what they were trying to accomplish, and often ended up with something else.

Not as if I’m saying that in this century, authors always know what they intend to achieve when they start out, or that the work doesn’t change in emphasis, or even the importance of characters alter, as the story develops; but no modern author would get away with the ambiguity of theme and content which does seem to characterise so many Victorian classics in particular, and I find this fascinating.

I assume Hardly wished to depict two things; how a noble character could rise above adversity, and also, how leading a secluded life, one in fact, in ‘idyllic’ rural surroundings, might not preclude a man or woman from tragedy and intense passions.

He does this; but with uneven emphasis and success in depicting the said passions, and their changing nature, and with rather a lot of set comic pieces to offset the tragedy, which carry on too long, at least for modern taste.

The four main characters – Gabriel Oak, Bathsheba Everdene, Sergeant Frank Troy and Boldwood (I’m not sure his first name is ever given; anyway, I didn’t feel on first name terms with him) are involved in melodramatic relations which seem all the more striking for being set against a peaceful, traditional rural background some time between 1815 and 1875 (the date of the publication of the book).

It is an interesting read; as I have said, I like the character of the heroine, who dares to try to be a woman farmer in Victorian times. The weaknesses in her character that enable the story to take place are fully believable in a pretty and spirited young woman, and don’t detract from the heroine’s general appeal for the reader (or this one, anyway). The main one is her vanity, which is an aspect of her valuing too highly superficial attractions to the detriment of placing a true value on sterling qualities which may be hidden. Accordingly, her inability to see the worth of Gabriel Oak, and her corresponding inability to perceive the worthlessness of Troy as a potential husband to a hard working farmer, is well thought out.

Gabriel Oak is an admirable, if not especially interesting, character, and is well drawn, though I would have liked to know more of his fluctuating emotional states. Sergeant Frank Troy is an intriguing example of a superficially attractive and charming but unscrupulous and highly unreliable man, and Boldwood is an equally interesting example of a dangerously repressed and potentially violent and obsessive man. The minor characters are adequate for the roles they play, but rather in the nature of stereotypes.

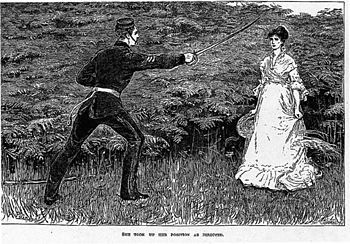

The structure is also good. There are two climatic scenes in the novel. The first, which is very successful, comes about two thirds of the way through. Here, Bathsheba and Troy stand looking at the corpses of the girl he has seduced and deserted, Fanny Robbin, and her newborn baby.

This is tellingly depicted:

’He was gradually sinking forwards. The lines of his features softened and dismay modulated to illimitable sadness. He sank on his knees, with an indefinable union of remorse and reverence on his face, and bending over Fanny Robbin, gently kissed her.’

Bathsheba’s jealousy and anguish overcome her pride and pity for ‘your other victim’ and she hysterically demands that Troy kiss her too. Brutally, he refuses; ‘You are nothing to me – nothing.’

At this, Bathsheba rushes out of the house, and Troy soon goes himself. Their very short marriage (it lasts about three months) is at an end.

This scene is vividly portrayed and dramatically effective.

The second climatic scene , which in fact constitutes the chapter which decides the fate of the characters in the whole novel, is a good deal less satisfactory. It’s recounted in a flat, cursory way (rather like the writing I was doing this morning, sigh) and fails to bring a sense of dramatic satisfaction to the reader.

The obsessive and reclusive Boldwood has become fixated with the notion of marrying Bathsheba after she sent him a facetious valentine. Troy’s whirlwind courtship of her frustrated his previous plans to marry her, but after it is wrongly assumed that Troy has been drowned, Boldwood hopes that he might persuade Bathsheba to marry him when Troy can be presumed dead after seven years.

Over a year passes. Oak is now working for Boldwood as well as Bathsheba, and shows no jealousy of his employer when he finds out that he plans to marry her. This seems to demonstrate remarkable self-restraint. Oak is depicted as fairly devout, and one assumes his praying helps him to overcome feelings of resentment and envy of Boldwood. He accepts, it seems, that having lost his former social status, he no longer is in a position to pay court to her, and whether he regrets the unimaginative and unromantic way in which he originally paid suit to her in the comic scene of his proposal, is not revealed.

The uneven access the narrator has to Oak’s various moods and attitudes towards the other characters in the book is one of the main weaknesses in the story. We are told in some detail how Oak is able to accept his loss of his status with stoicism, but not how he is able to bring himself to accept that Boldwood ‘deserves’ Bathsheba. I assume the first is meant to be a pointer to the second. Also, he approves of Boldwood as a suitor for her, while he does not approve of Troy, whom he rightly considers to be immoral and unreliable. He does not, however, seem to notice that Boldwood is potentially dangerously obsessive.

The mirthless Boldwood holds a Christmas party. Despite the ample food, music, and roaring fires, nobody enjoys it. Things are made worse by the fact that Troy has been seen in the area, and Bathsheba doesn’t know it. Bathsheba is hectored by Boldwood into agreeing to marry him in nearly six years’ time, on the grounds that in sending him that Valentine in the wrong spirit, she has inflicted misery on him.

The unlucky girl is in the hall when it finally dawns on Boldwood that his guests look at him oddly. As he demands the reason, Troy arrives. He has been living an itinerant life since he left her, and is fed up with it. He orders her to come home with him.

Seemingly horrified (we never are told just what her feelings are at this point) Bathsheba shrinks away:

‘The scream had been heard a few seconds when it was followed by a sudden deafening report that rang through the room and stupefied them all. When B had cried out in her husband’s grasp, Boldwood’s face of ghastly despair had changed. The veins had swollen and a frenzied look had gleamed in his eye.’

Troy ‘Uttered a long and guttural sigh; there was a contraction, an extension, his muscles relaxed, and he was still’.

The very brevity of this depiction in the second sentence has a good deal of skill, but it cannot make up for the moment of high drama being recounted largely in the passive and in the perfect tense (to be pedantic). This has a distancing effect and much of the drama is dispersed. It would have been a good way for a novelist to recount something really distressing, as the sudden death of the unpleasant Troy is not, but leaves the reader unsatisfied in this, the climatic scene of the whole novel.

The very brevity of this depiction in the second sentence has a good deal of skill, but it cannot make up for the moment of high drama being recounted largely in the passive and in the perfect tense (to be pedantic). This has a distancing effect and much of the drama is dispersed. It would have been a good way for a novelist to recount something really distressing, as the sudden death of the unpleasant Troy is not, but leaves the reader unsatisfied in this, the climatic scene of the whole novel.

After this, the novel does rather peter out. Bodlwood is discovered to be mad, and the death penalty in his case is commuted. Troy’s widow and Gabriel Oak’s wedding seems inevitable, and the delays before it happens, with Oak threatening to leave the country (presumably in order to escape his seemingly hopeless passion for Bathsheba) did not make it seem any less likely to me.

I liked the fact that in putting up a memorial for her errant husband, Bathsheba demonstrates that she has acquired the very quality she has admired in Oak before, a stoic ability to endure life’s injustices without engaging in self pity or low minded acts of retaliation to those who have frustrated our personal desires. She buries him with Fanny Robbin, and the tombstone he erected for her commemorates them both. Bathsheba was earlier the one who replanted the flowers on Fanny’s grave, when a downpour had washed away Troy’s handiwork. She has matured and grown in emotional stature to become the worthy mate for Gabriel Oak that she was not before.

I just hope that Bathsheba finds him physically attractive; that she obviously did not at the beginning, is shown by how she does not even acknowledge him when he gives her money to pay at the toll gate where he first sees her. However, he is described as ‘a fine young man’ and we gather he is well made enough, so I assume that though the Victorian author could not make any direct statements about such a matter, that he has come to appeal to her physically too.

I saw various resemblances to George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ in some of the themes in this novel, including that of a seduced and pregnant unmarried girl, a young woman mistakenly choosing a dashing and unreliable admirer rather than the steady and less glamorous one, the stoic, hard working and devout hero, the depiction of ‘traditional’ rural life and traditions, and the contrast between the ‘peaceful’ countryside surroundings and the strong passions of the main characters.

Would I recommend it? Yes, as I say, it’s an interesting read, and I found the plot far more believable than, say, ‘Tess of d’Ubervilles’ or ‘Judge the Obscure’. Still, the somewhat sketchy depiction of Troy, who is after all, a character central to the novel, and the equally threadbare depiction of Bathsheba’s growing passion for him and her quick disillusionment with him (she says ‘I may die soon’ implying a general weariness with life only weeks after she marries him) make for weaknesses in the development of the plot (even the wedding takes place ‘offstage’ in ‘Casterbridge’(Oxford?) .

There are circumstances where a writer leaving a character’s mental life unknowable to the reader, or perhaps only partly known, can make him or her all the more intriguing to the reader, but I didn’t find this to be so with Troy, for the simple reason that Hardy devotes a whole chapter to revealing Troy to the reader through ‘tell not show.’

Next Week: Beginning on my re-read of Anne Bronte’s ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’.

September 19, 2015

Some Thoughts on Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

Recently, I’ve been reading another classic I have been intending to get down to for years; Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

Recently, I’ve been reading another classic I have been intending to get down to for years; Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far From the Madding Crowd’

To be unsparingly honest, I don’t know what I think of it; my feelings are mixed. I fid the style convoluted, but some of the descriptions are highly evocative, the characters are individual, and it’s a generally interesting theme – that of a young woman who wants to be an independent farmer at some point in that most patriarchal of environments, some time in the earlier part of the nineteenth century England (the precise date is never given, but it was published in 1875, and the writer refers the events as taking place in a former age.

I assume it is post the time of the massive enclosures of the common land and the unrest caused by those, but even this isn’t clear, though they are never mentioned. The image is of an essentially unchanging, insular community, and the title, I assume (again, I haven’t read any of the literary criticism) is meant to be ironical in that intense passions and violent deeds, seductions and betrayals form a large part of the story (I duly note that it is a quote from ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’; I remember ‘doing’ that at seventeen in English Literature; I thought the first four verses inspired; the rest dull).

In fact, the passions and betrayals – with the exception of the unlucky seduced maidservant, Fanny Robbin – are largely confined to the four main characters, three men and a woman, who are not really typical of the rest of the community, being set above them either by natural talents (Gabriel Oak, who anyway comes from another village) and the oddly named Bathsheba Everdene, or social position ‘Farmer’ Boldwood, or both – Sergeant Frank Troy.

The rest of the cast are, it is true, motivated by the normal human passions, and fairly unheroic in general, although not invariably mean spirited. I vaguely remember hearing that Hardy was a great exponent of the simple virtues of country life (he must have found a willing acolyte in the later Charles Garvice, who thought it was a cure for wild young men, rather like a stint in the army).

Life for the people in this rural community in ‘Wessex’ is generally depicted as reasonably pleasant, if labour is hard, and the discomforts of life in a cramped, damp cottage without proper sanitation receive no notice (Gabriel Oak is presumably able to rise above such inconveniences as having no proper lavatory; after all, he is able to surmount most things, including losing his beloved to a man who doesn’t value her, and losing his former status as a farmer; Stoicism is his second name, and Steadiness his third).

In some ways, I preferred the extreme picture painted by Zola in his depiction of rural life around the same period in central France, ‘The Earth’.

There, passions run riot; greed is the order of he day, and the pastor has been driven out because the godless peasants refuse to pay their tithes. Lust, cruelty and incest are part of everyday life, and I have to say that in an extreme way it rang true for me of country life in highly isolated areas in England in the late twentieth century. It made me laugh, as it reminded me of a certain area in North Devonshire in which I spent some years during my childhood, where the vicar had indeed been driven out by the locals (I played a prank in naming this village in the title of a book in the library in my own novel, ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois).

This, however, is meandering from the point; Zola made a thing of writing contentious novels that attacked religion and treasured illusions generally, and exploding the traditional French admiration of the stolid, worthy peasant, ‘Jacques Bonhomme’ was just a part of it. Hardy was fired by no such motives; it seems to me, by contrast, he wished in part to portray the delights of farming life in an age when it was under threat from growing industrialisation.

Bathsheba, then, is an unusual heroine by Victorian standards; she is an independent heroine who wants to make her own way in life. When her uncle takes the unprecedented step of bequeathing his farm to her, she runs the farm by herself. She does, through inexperience, run into some difficulties, but she is helped by the devoted Gabriel Oak, who in the former village where they both lived, before he lost his flock and his independence, was her rejected suitor.

Trouble arrives the shape of the dashing, handsome, philandering and unreliable Sergeant Troy, who courts Bathsheba with displays of sword play and gallantry. Bathsheba is soon hopelessly infatuated with him, and ready to jeopardise her future independence to make him hers (marriage in early nineteenth century England deprived a woman of all legal rights and all her properly became her husband’s on marriage).

The author remarks: ‘When a strong woman recklessly throws away her strength, she is worse than a weak woman who has never had any strength to throw away’.

I can’t take exception to that; it’s still horribly true today; it is an unusual woman, who, once she succumbs to romantic attachment to a man, can see him or her circumstances objectively at all, this inevitably being bound up by the notions of romantic love and emotional dependency which woman are encouraged to cultivate.

There is more excuse for Bathsheba for adopting this course than many a woman in our own age. As a woman living in a small rural community in an age of unquestioned notions of female virtue and before effective birth control, she cannot indulge her passion for Troy outside marriage. In that case, when due disillusionment came, she could suggest a parting of the ways. Instead, she marries him.

I haven’t finished the book, but I can see that Sergeant Troy is destined to come to a bad end; he proves himself a ne’er do well, and refuses to take the sensible counsel of Gabriel Oak and so risks the harvest while engaging in a drinking spree with the labourers at the Harvest Festival.

We have seen nothing of Bathsheba and Tory’s married life, but we gather from her hint to Gabriel Oak at this time, ‘I may soon die’ that she is already, a few weeks after the ceremony, very unhappy and sees that she has made a fatal error.

A few weeks later, the run away servant maid Fanny Robbin turns up again, and dies in childbirth in a local warehouse. The reader, unlike the heroine, knows that Troy is her seducer, and that he would have married her except that she went to the wrong church, after which he left in a rage.

Troy is a strange character. Seemingly happy to forget Fanny Robbin before (one assumes he didn’t know that she was pregnant, as the dates would make it very early for him to do so at that time of their proposed wedding) , he undergoes a violent reaction of grief and remorse.

When by a series of unfortunate co-incidences, the poor girl’s body is taken to Bathsheba and Troy’s farmhouse, the superficial Troy furiously rejects the woman he has married in favour of his dead former love.

Reverentially kissing the dead girl’s face, he exclaims: ‘That woman is more to me, dead as she is, than you were, or are, or can ever be…You are nothing to me.”

He then spends all his (really, Bathsheba’s) money on a headstone for Fanny Robbin and leaves the area. Circumstances combine to give the impression that he has been drowned, and he stays away for many months. Meanwhile, the strangely obsessive Farmer Boldwood has resumed the persistent courtship of Bathsheba that Troy’s advent interrupted, and the faithful and steady Gabriel Oak continues to be just that, now employed as bailiff by both the traumatised Bathsheba and Boldwood.

This former dramatic scene, though extremely well depicted in Hardy’s usual melodramatic style, is unfortunately detracted from by the fact that we haven’t seen enough of Troy’s impulsive and superficial nature, or his quick boredom with life as a farmer and Bathsheba’s husband, to make it fully convincing. True, we have seen him desert Fanny Robbin after she failed to turn up at the ceremony, and we have seen him neglect the harvest, but the progress of the theme is too abrupt. More hints of the diverse and finally incompatible natures of the fickle Troy and the intense and loyal Bathsheba are needed to make it as dramatically effective as it could be.

Hardy is a great one for telling not showing. and he does this with a whole chapter devoted to Troy’s character, where we are told just what he is. This was probably in line with Victorian taste, but is considered inadequate in our own age, where readers want Troy to show them what he is.

Well, that’s my opinion of this climatic scene; what the general one is, I don’t know, because I’ve been lazy and left the literary criticism unread

(I haven’t even seen the recent film).

As I say, I have only read three quarters of the novel. In part it seems to be covering a theme to be found in various novels of both the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries (and also the twenty-first) that of an attractive young woman who has tow admirers, one of whom is steady and lacking in obvious charm, the other of whom is flashily charming, but unreliable.

Examples of this I’ve read include George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ and of course (sorry everyone, for mentioning it again) Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’.

Hardy’s novel is complicated; of course, by the presence of a third admirer, and this is an original stroke. He is neither flashily attractive, nor steady but lacking in dash. Boldwood is handsome, but withdrawn; intense, but repressed. He is obviously a walking time bomb.

Next post; Some More Meandering Meditations on Thomas Hardy’s ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’.

September 4, 2015

Writing the Unusual, the Innovative, and INCA

This will be an unusually short post; real life commitments and all that sort of thing.

This will be an unusually short post; real life commitments and all that sort of thing.

To bore on about my own experience for a minute; I usually seem to end up writing cross genre stuff (swear box for agents and publishers).

I try not to; these days, I do try to force my mind to concentrate on the target audience, on where the book would be shelved, how I will categorize it, and so on.

Obviously, I don’t try hard enough to keep my mind on the market, is all I can say, because somehow — those goals seem to go by the wayside when I see the possibilities of a plot.

I can see this problem being addressed with a simple answer in the style of one of those cartoon style advertisements I remember from my distant childhood. Highly unsophisticated line drawings, a troubled person (usually female) asking a wiser, smiling older confidant (again usually female) what to do:

Anxious Looking Indie Writer: ‘Clarinda, I just have such trouble. I always end up writing cross genre stuff, and I’m sure it reduces marketability.

Clarinda, the Smiling Confidant (looking detestably smug) My dear,what you need to do is to read my new book ‘How to Churn ‘Em Out Without Thinking’. It’s got a ten point plan (out Stalin-ing Stalin, you might say). Rule number one is don’t ever venture outside genres; you know what’s outside there. Dangerous marshes and swamps; wild, snapping animals,loneliness, ostracism from Facebook communities…’

Anxious Looking Indie Writer: Clarinda, you are so right. Can I have a copy?

Clarinda: £2.99 from Amazon, dear. You can upload a free sample…

Yes, well, anyway, enough madness. I was pleased to encounter a group called ‘INCA’ which has a different ethos. INCA encourages writers aiming for the innovative and the unusual and I have joined them.

Here’s the link. There’s some fascinating looking reads on there.

I’ll leave you with a quote from Barbara Cartland, author of 700 books (seriously!). Would I imply for a moment that in her later novels, she wrote the same plot over and again? But I was fascinated to learn that when younger, she wrote risqué plays, one of which, ‘Blood Money’ was apparently banned by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. What was that? It doesn’t seem to do much banning any more…

August 28, 2015

Complex Villains and Samuel Richardson’s Robert Lovelace from ‘Clarrissa’

Complicated characters , whether heroes or villains (I’m applying the terms to both sexes) or a bit of both, are always fascinating.

Complicated characters , whether heroes or villains (I’m applying the terms to both sexes) or a bit of both, are always fascinating.

As I see it, there’s only two problems with complex characters , good and bad: one is that they take so much work to envisage and the other is that, portaying them adequately will necessarily involve a bit more of a word count – and in this age of hurry where every minute is counted, that may be resented by readers.

To name only two examples from classic literature – Shakespeare’s Mark Anthony is intriguing, and so is Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. Both combine admirable qualities with very inadmirable ones, a capacity for feeling, for magnanimity, mixed with an equal capacity for cold indifference.

I am particularly fascinated by the depiction of the wicked Robert Lovelace by Samuel Richardson. He is meant, of course, to be an arch-villain. I think, like some writers today, Richardson was dismayed, even shocked, when he found that too many readers – particularly women – found Lovelace so charming that they were prepared to fall over backwards and make excuses for the rape and even apportioned some of the blame to Clarissa herself.

I might not agree about many things with Richardson – as much an arch patriarch in his own way as the rakish Lovelace – but I do about this; there’s never any excuse for rape.

Still, I can see how the readership became fascinated by Lovelace. His letters do make fascinating reading; witty and debonair, his fiendish delight in his own machinations is often amusing. Sometimes the reader has to laugh along with him. He manipulates others as if they were, in his own words, ‘just so many puppets dancing on my wires’.

This man is subtle and conniving; he’s got a flashy charm, and he’s clever enough to appear ingenuous; in fact, he’s always declaring how ingenuous he is and how he gets carried away by his natural ‘warmth of temper’ (or words to that effect). After a time, the astute and sharp-tongued Anna Howe begins to see through him; Clarissa, so honourable herself that she finds it hard to discern underhand, manipulative behaviour in others, takes longer. Without Ms Howe’s letters, she would soon be overwhelmed by Lovelace’s connivances and her own over fine moral scruples.

This man is subtle and conniving; he’s got a flashy charm, and he’s clever enough to appear ingenuous; in fact, he’s always declaring how ingenuous he is and how he gets carried away by his natural ‘warmth of temper’ (or words to that effect). After a time, the astute and sharp-tongued Anna Howe begins to see through him; Clarissa, so honourable herself that she finds it hard to discern underhand, manipulative behaviour in others, takes longer. Without Ms Howe’s letters, she would soon be overwhelmed by Lovelace’s connivances and her own over fine moral scruples.

A lot of this is purely calculated; he has anger fits when he wishes to intimidate – he has something of the bully in him, as he can keep the said passions in check as well as anybody when he chooses to.

This is a point that ought to be bourne in mind in view of his later rape of the unlucky Clarissa, who has allowed herself to be drawn in by him and thrown into his protection, believing in his honour: if Lovelace has any honour, he has none towards women. They are to pay forever for his earlier betrayal by his first love. This is insane; Lovelace’s egotism and misogyny often border on the deranged.

This calculating rogue, who defines himself as ‘as michevous as a monkey’ who ‘would have been a rogue, had I been a ploughboy’ loves bribery and corruption; he’s got a conniving tool in the hostile Harlowe’s manservant, his double agent Leman (wonderful name; I think it means ‘lover’ in old English) . He spins a complicated web to surround his victim, because he likes to make a woman fall into his trap, so he can look down at her and say: – ‘Aha, my charmer! How came you there?’ (Lovelace is often rather a stagey sort of villain: I believe he was based n the character Lothario in the play ‘The Fair Penitent’ and he often has the speech patterns and mannerisms of this stage villain).

This is the more fascinating, because the puritanical, diligent Samuel Richardson obviously had hidden depths in his psyche – we all have, of course, but rarely is there such a huge divide between the character depicted and the superficial personality of the writer. Richardson’s imagination must have been incredibly fertile, and I would love to hear what a post Freudian analysis of his psyche would make of his apparent sexual repressions.

Did Richardson’s model hero, Sir Charles Grandison, lock himself in his closet, concoct some noxious brew, and turn into Robert Lovelace on the sly? I wouldn’t put it past him at all. I never trust these too-good-to-be-true types.

Overall, the challenge of a creating a complex character, particularly a complex villain, or a complex anti-hero, is a tempting one for any writer. I’m tempted to delve further into it myself in due course.

My own Émile Dubois is a fairly complex character. He is apparently straightforward, and he doesn’t usually tell people lies (apart from the forces of law and order, that is) . His intentions towards Sophie are honourable and his courtship of her straightforward until he mistakenly believes that she is lying to him.

Still, neither does it always suit him to tell people quite the whole truth. He appears to be open-hearted – but he can outwit both the Committee of Public Safety over in Paris, living under an assumed identity for upwards of three years – and he is fully able to second guess the underhand machinations of Goronwy Kenrick. Bribing Kenrick’s servant comes as second nature to him, just as it does to Kenrick. This was all part of the eighteenth century aristocratic mentality, of course, particularly of those who had been connected with that hotbed of conspiracy Versailles.

This slightly tricky quality, demonstrated by his skill at chess, is lurking in readiness to come to the surface when he starts to turn into a monster. One part of him always remains as a tender lover, but another, the increasingly prominent monstrous side, revels in surrounding Sophie and driving into a corner just as he does in a chess game.

Émile, however, is – as his human self – generally a nice enough scoundrel despite this slight trickiness in his make up; he is extremely gallant to women generally, and has a sense of honour, being almost fanatically loyal to his friends. He is also shown – I’d like to emphasize here – as disgusted by the idea of rape.

Reading Clarissa has certainly tempted me to write about an out-and -out scoundrel without moral scruples – and just like Richardson, I won’t dream of letting him off; he’ll get the come uppance he deserves at the end.

August 21, 2015

A Round Robin from Kenrick

Dracula climbing down the wall of his castle, from a 1916 edition of the work.

I, Goronwy Kenrick, receive so much of what you moderns call in your rebarbative parlance ‘fan mail’ that I feel I must reply ; yet, having no spare time (and that in itself is ironic, in view of my experiments with time, ha, ha!) I am taking advantage of another vulgar modern idea – the Round Robin. Humph!

I will discount the absurd prejudices of some of my correspondents , who have accepted, unquestioningly, the lurid and prejudiced account of my activities to be found in the guise of sensationalist literature – ‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’ by some insolent and frankly immodest female called Lucinda Elliot (really, we kept the matters of the bedroom shrouded in discreet silence in my day).

Yes, if some female readers are so sadly misguided as to regard that French ruffian Dubois as some sort of heroic figure – I have only to say that it was dire necessity alone which compelled me to usher through my front doors a former cut throat from the gutters of Paris.

A disgusting fellow, I assure you, fond of a vulgar brawl and loutishly blunt, accusing me of practicing blackmail upon him – and unable – Heh Heh – as I have had occasion to remark elsewhere, to keep his hands for long either off the public’s pockets or off their wives, either. His boor of a lackey was even worse – my own milling manservant Arthur Williams being an upright citizen in comparison.

What was I saying, my good people? Ah, yes, fan mail. I have just accidentally read a communication that has put me out of temper – an insolent scrawl referring to me, if you please, as ‘creepy’ and ‘flesh crawling’.

It even goes on to suggest that I am ‘dirty minded’.

I, ever the prize romantic ? I would have the writer of that contemptible missive know, that I only ever loved one woman – my wife!

Yes, that parvenu Heathcliff – created, I believe, circa 1848 – cannot compete with me as a Byronic hero. No, indeed. I not only loved one woman, and mourned her death with passionate devotion, but I have tried to subvert time to achieve reunion. Did that vulgar, porridge eating Yorkshire farmer stretch his imagination so far?

Oh yes, it is true, I remarried – but love was never in question in that match. We both wanted the same thing – reunion with a lost loved one; I knew Madam Ceridwen would be useful in furthering my aims. further, I will admit, I do enjoy watching the effect of the second Mrs Kenrick’s beauty on foolish young males (like Dubois, only a month married, dear me!).

Heh, Heh.

Dubois’ little wife was something of a peach – blonde and curvaceous as she was. I cannot imagine what she saw in the ruffian, apart from as a means of escape from her tedious life as a Dowager’s companion.

I once found myself having arrived quite by accident in her bedroom. Well, not quite by accident – I had heard she had a sore throat that day, and I had just remembered an infallible cure for the same – but that foolish Earl of Ruthin had made her drink some – some – a drink made of – gar – garlic, that most disgusting of herbs. Weak at the knees, I had to retreat, my handsome face haggard with distress.

Sophie found the house Emile rented near Llandyrnog perfect – but he thought it very small.

I make no doubt even that fleeting glimpse of me, my well modelled mouth ready for a kiss, roused a flutter in her tender bosom, though.

Damn me, I am called away. I must needs ask my many admirers to wait until the next post – Ha! Ha! – to satisfy their longing to hear more from me and to sign off as your own

Goronwy Kenrick

Vampire, Inventor and Mathematical Genius

August 15, 2015

Those Dreaded Discrepancies: A Writer’s Bane

Firstly, I want to apologise to Susan Hill by mentioning her work in the same post as that late Victorian and Edwardian writer of best selling twaddle, Charles Garvice…

Firstly, I want to apologise to Susan Hill by mentioning her work in the same post as that late Victorian and Edwardian writer of best selling twaddle, Charles Garvice…

Mari Biella’s recent intriguing recent post on anachronisms

https://maribiella.wordpress.com/

set me thinking recently about general discrepancies in stories. Then, in a fine piece of synchrnonicity, I came across at least two when reading George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’.

This in turn brought to mind several I’ve come across in recent years, from a whole spectrum of writers, from the brilliant Susan Hill to that churner out of Victorian best selling romantic melodrama Charles Garvice.

That so polished a writer as Susan Hill could make a mistake of this type is guaranteed to make any writer wonder, with a shudder, if there is something she has overlooked in turn in her own stories; some howler, which makes the plot impossible, or at least, in need of revision.

Or –nearly as bad – but, our egotism being what it is, not quite so bad – have we let down the friends for whom we have done Beta reads, and left one in? Maybe an anachronism of the sort mentioned by Mari Biella, for instance, potato stew served in the UK of the Middle Ages.

On anachronisms – in true geek fashion – I want to say something irrelevant here. I was dismayed to learn that people who write children’s novels set in the Middle Ages are often advised to fudge the issue that for approximately three hundred years after the Norman Conquest, the upper class spoke Norman French, while the ordinary people spoke Anglo Saxon. Talk about re-writing history!

All writers surely go in dread of such mishaps as publishing a book with discrepancies. They are so easy to do, particularly in historical novels. It is so easy to get those wretched travelling times wrong, through a lack of information about which roads there were; so easy to make the post more efficient than it was, so that a letter arrives too early.

The Susan Hill discrepancy – and I hasten to add, this is the only one I have ever come across in all her books, all of which I greatly admire – is to do with the decade in which the otherwise brilliant (and terrifying) story ‘The Man in the Picture’ is set.

It seems to originate in a few sentences overlooked in the editing, which possibly relate to an earlier version (and don’t we all have so many earlier versions of our stories, where we hadn’t developed this or that theme).

The story begins with a man visiting his old friend, an academic at in Cambridge, where ‘there were still real fires in those days, the coals brought up by the servant in huge brass scuttles.’ Some years later, again in Cambridge, the porter has ‘a fire in the grate’ and there is ‘a solitary policeman on his beat’. This policeman is seen ‘trying the doors of the shops to see that they were secure’.

All this seems redolent of the 1930’s. Yet, only a few months pass, and suddenly, we are in the age of mobile phones, the narrator marries a female barrister and they fly to Venice for their honeymoon.

This inconsistency, by the way, didn’t at all detract from my pleasure in the story, and so far as I know, only a couple of reviewers have picked up on it; it is nearly as good a sinister read as ‘The Woman in Black’.

The discrepancies in George Elliot’s ‘Adam Bede’ come much later in the story, and revolve around the fact that while the fact that while Adam guesses who fathered Hetty Sorrel’s poor baby, and confides in the vicar Mr Irwine, these two, who wish to talk of the matter as little as possible, are the only ones who do. Despite this, shortly afterwards, by some strange process of clairvoyance, all the servants in the hall know that it is Arthur , and this detracts from their enthusiasm when they welcome him home as the new master.

A smaller error concerns a minor character, Bessy, who is described as married to Wiry Ben in the beginning, with two children. At the fete where he dances, they suddenly both become single again, the children disappear, and he hints that he wants to marry her. A time warp has clearly been in operation…

Thackeray went one better. His dull hero, Dobbin, appears in England when the reader has been told that he is serving in the army in India; a clear case of teleportation, and typically, his astral self does nothing but the sort of dull but worthy stuff he always does. Apart Amelia’s mother changing her name from Betsy to Mary, though, mistakes in a very long novel which I believe was first published in serial format are very few.

Elizabeth Gaskell rarely edited her works, so that the standard of writing is all the more impressive; still, in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’, as Graham Handley has pointed out, the timing doesn’t make sense if the reader accepts the action as starting in 1795, the date she gives; the timetable is out of kilter unless the action starts in 1793.

There are other discrepancies; Philip Hepburn’s age, and Charley Kinraid’s financial position are but two, but overall, the degree of consistency in the plot in a writer who rarely re-read her work is quite astonishing.

Finally, to Charles Garvice. I am sure the modern readers of ‘The Outcast of the Family Or a Battle Between Love and Pride’ can be counted on one hand, so almost certainly nobody will have any idea what I am talking about here. But what I have to say is instructive, because it shows, if nothing else, how sloppily his editor performed.

Finally, to Charles Garvice. I am sure the modern readers of ‘The Outcast of the Family Or a Battle Between Love and Pride’ can be counted on one hand, so almost certainly nobody will have any idea what I am talking about here. But what I have to say is instructive, because it shows, if nothing else, how sloppily his editor performed.

Because this novel is so bad, I have remained fascinated with it (perhaps I would have been equally fascinated by whichever Charles Garvice novel I read, as Laura Sewell Mater was intrigued by ‘Verdict of the Heart’ for more or less the same reasons. Therefore, I’ll give some background to it.

The hero of that melodrama, Lord Fayne, is a bad man who turns into a good man because an innocent young girl tells him he should (he also goes busking in the country, and that does the trick). He’s a viscount, but goes round dressed as a coster monger, and getting into fights in music halls. He does this primarily to annoy his relatives, as his politics are anything but radical.

The hero of that melodrama, Lord Fayne, is a bad man who turns into a good man because an innocent young girl tells him he should (he also goes busking in the country, and that does the trick). He’s a viscount, but goes round dressed as a coster monger, and getting into fights in music halls. He does this primarily to annoy his relatives, as his politics are anything but radical.

During one such fight in a music hall, he is hit on the head by a decanter and only comes to himself with a bleeding head some time towards dawn. No mention is made of a headache or such sissy symptoms of concussion as nausea.

He goes on to run into a homeless girl who just happens to have been seduced by the villain of the story, gives her his golden cuff links and buys her some food at a stall, giving over his watch as security. His friends are still drinking in his house when he arrives home at some time in the morning. Having shown some anti Semitism by threatening to throw a Jewish moneylender out of the window for requesting his bill, gives his friends a brilliant performance by singing and playing the piano and violin, and then kicks the lot of them out with his ‘air of indefinable command’ and falls asleep with his head among the dirty glasses.

He goes on to run into a homeless girl who just happens to have been seduced by the villain of the story, gives her his golden cuff links and buys her some food at a stall, giving over his watch as security. His friends are still drinking in his house when he arrives home at some time in the morning. Having shown some anti Semitism by threatening to throw a Jewish moneylender out of the window for requesting his bill, gives his friends a brilliant performance by singing and playing the piano and violin, and then kicks the lot of them out with his ‘air of indefinable command’ and falls asleep with his head among the dirty glasses.

When next we see him, he is asleep outside the gates of his parents mansion. The heroine mistakes him for a tramp and adjusts his cap over his injured head (this isn’t portrayed humorously, unfortunately). He tells her he has walked from London and goes on to sleep some more a bit further off, where he sees her pony bolting and through a desperate sprint, saves her from a terrible death in a disused copper mine.

He remains incognito throughout, but her father has read of the brawl in the music hall in his paper, and mentions that Lord Fayne appeared ‘in a police court’ and was fined £5.00 (a hefty fine in 1894).

There appear to be all sorts of weird discrepancies in the time frame here. When did Lord Fayne appear in court? How long did it take the papers to report it, and how come it only seems to take even the athletic Lord Fayne a day or so to walk from London to what appears, from the topography, to be Devonshire, particularly if he is suffering from concussion? Perhaps he (horrors!) lies to the heroine, and he took a train. Certainly, though, when she demands to see how much money he has in his pockets, he only has some silver.

But from someone who is concussed, he gives a sprint worthy of a gold medal. Presumably he has come to apologise to his parents, but after being conveniently by to save the heroine’s life, he seemingly wamders off again, and when next we see him, it is in London, where he seems once more to be in funds…

Garvice’s novels are no doubt peppered with such contradictions, and it is only because of my interest in the history of the development of the romantic novel that I have have read this twice. I am sure almost nobody else could endure such entertainment twice over, and most people would say, and rightly, that such twaddle is unworthy of any analysis whatsoever, and Garvice only made the roughest attempts to provide some sort of basic coherence to his plots.

Still, he had, supposedly, an excellent secretary, and I am surprised she didn’t pick up on these contradictions; maybe it was more than her job was worth to pick holes in the novels her pipe puffing, complacent employer dictated. Perhaps his editor could not bear to read his stories through…

However that may be, such discrepancies as the ones above are one of the banes of a writer’s life.