Lucinda Elliot's Blog, page 27

May 3, 2015

Escapism and Empowerment

Today, I���m going to rant a bit (did I hear you say ���So what���s new?)

Today, I���m going to rant a bit (did I hear you say ���So what���s new?)

I came across some low criticism in a feminist ezine that really dismayed me.

As this remark ��� which seems to have gone unchallenged for two years ��� is part of a criticism of some opinions about literature expressed by Germaine Greer in ���The Female Eunuch���, published some forty-five years ago, no less, I���d better explain why I think it matters, and the background to my interest in the issue.

http://theladiesfinger.com/why-georgette-heyers-alpha-males-are-people-too/

I���ve been doing some research on romance reading and women���s oppression. I���m sure regulars will have noted that my own view is steadily moving towards a conviction that it is a contributory factor.

Now, when I get into something, I out-Geek all Geekishness. I go into things deeply, even if it���s torture (and believe me, some of the reading I���ve had to for this has been; still, it���s self inflicted; I���ve only myself to blame).

So, I began my background research by reading some of the late Victorian and Edwardian romances of Charles Garvice. Virtually forgotten today, he was a best seller in his time. I remembered him initially because, when snow bound in the Clwyd Valley for some weeks in my teens, I ransacked the bookshelves in the house, and came across a copy of a melodramatic romance ���The Outcast of the Family Or A Battle Between Love and Pride��� (1894) which my mother had acquired as part of a job lot in an auction. I read it and never forgot the sheer badness of the writing. About a year ago, I got through five of his.

I then moved on to Georgette Heyer. I���d read several of these during the same snow bound period, including, ���Powder and Patch��� ���Devils��� Cub��� ���The Convenient Marriage��� ���The Talisman Ring��� (the subject of my last post) ���The Toll Gate��� ���Friday���s Child��� and ���The Foundling��� so I only needed to refresh the remains of what was once a good memory regarding those, and to read a few more, to have a fair working knowledge of Heyer.

Literary criticism of romantic novels is decidedly thin on the ground. This is unfortunate, as the few books I have come across on it seem to be recent, and are often�� somewhat abrasive defences of the genre by its proponents rather than anything in the nature of an objective analysis. Some even claim that romantic novels have a long and respectable history going back to Jane Austen; I���d dispute myself that Jane Austen was in any way a writer of romance. Few seem eager to claim the obvious influence of Charles Garvice.

In plodding about the web (I don���t regard it as surfing) I came on an article in an ezine with the startling name of ���The Ladies Finger��� which a couple of years ago published an article on Germain Greer’s well-known discussion of romantic literature, and of Barbara Cartland and Georgette Heyer in particular, in ���The Female Eunuch���.

The author, who thinks that Heyer is ���the best writer in the world��� (or in the next?) and has read each of her novels no less than five times, takes great exception to Ms Greer���s satirical treatment of Heyer���s 1935 novel, ���Regency Buck���.

Greer says of the heroine, who is spirited within strict limits of ladylike behaviour: ���Her intelligence and resolution remain happily confined to her eyes and the curve of her mouth, but they provide the excuse for her naughty behaviour toward Lord Worth, who turns out to be that most titillating of all titillating relations, her young guardian, by an ingeniously contrived mistake.���

She mocks the ���Alpha male��� hero: –

���Nothing such a creature would do could ever be corny. With such world-weary lids! With the features and aristocratic contempt which opened the doors of polite society to Childe Harold, and the titillating threat of unexpected strength! Principally, we might notice, he exists through his immaculate dressing���Beau Brummell is one of his friends������

n this part of her ground breaking book on female oppression, Germaine Greer is investigating the masochistic, sublimating and passive elements of women���s romantic fantasies that are catered for in novels with ���Alpha��� males who define the female leads��� destiny.

With acid wit, she analyses a story published in the teenage girls��� magazine ���Jackie���, a novel by Barbara Cartland, and the one by Georgette Heyer.

The blogger in the ���Ladies Finger��� article – who protests that she becomes impatient with theoretical debate because she ���doesn���t have a college education��� takes the view that all opinions of romantic novels must be fueled purely by personal taste rather than any objective analysis, and writes: –

���When I read Greer���s criticism I���m reminded of my second-wave self at 17, and I feel kind of sorry for her. The ���ingeniously contrived mistake��� is called a plot device, you! And it sounds perfectly natural! And now I���m going to say something more offensive than the entire genre put together: This scale and breadth of offense (sic) at the sexual fantasy reeks of deep and unwilling arousal������

This is descending to the level often adopted by openly sexist men, and explaining any objection to sexual stereotypes by slighting references to the protestor���s psyche and supposed sexual orientation or frustrations.

While this can be a piece of fun with characters in books (as in my post touching on the unconscious passions of Sir Tristram Shield and Ludovic Lavenham in ���The Talisman Ring���) for an article published by a feminist ezine to make such comments about another woman,and a bold feminist innovator at that, gave me a highly unpleasant surprise. I was the more dismayed by it, as it was published without a disclaimer from the editorial board.

Earlier in the piece, the writer of the article complains that Ms Greer���s research appears not to have gone beyond reading one book by either Heyer or Cartland, and that she would have changed her mind had she read more.

While it is true that Ms Greer only mentions one book, it isn���t clear how many she had in fact read, and going purely on anecdotal evidence, most women of that generation seem to have read more than one novel by Heyer at least. To object to only one book by each author being analysed is reasonable, though as ���The Female Enuch��� is not primarily a work of literary criticism, this was presumably done through lack of space.

Now, as I have ploughed through a dozen novels by Georgette Heyer, I can hardly be accused of sketchy research. I was open to be persuaded that they have a feminist slant, as some argue, but I have yet to find it. I have to agree with all of Germaine Greer���s analysis in ���The Female Eunuch��� (for all I know, she may have modified her position since).

I began my researches on women and romance literature with far more of an open mind on the issue than I could have had a couple of decades ago. Sadly, I am coming increasingly back to the conclusion that romantic fantasies to be found in the works of historical and other romantic novelists such as Heyer do serve to keep a significant element of women���s energies focused on fantasy rather than action, escapism rather than the will to implement change, and therefore play a part in women���s (sadly, often partly self-inflicted) oppression. especially as part of this fictive dream is a wish to be taken care of, to have one’s destiny controlled by, a man.

The vague talk of ���empowerment��� through female fantasy I have come across in several books and articles strikes me as nonsensical; nobody ever challenged the status quo by indulging in escapist dreams.

I would say that at the moment there is a significant reaction against the strong line of ���Second Wave Feminism���. To some extent, this is understandable.

As a young girl I often fell out with purists who objected to my refusing to kit myself out in dungarees, a cropped haircut and pebble rim glasses, as ���good��� feminists of the eighties so often did. I pointed out that the image of feminism they projected was one which the majority of the female population would find highly unappealing, and so it has proved.

Some of their ideas were simplistic, others extreme; as with all revolutionary movements, humourless fanatics were often in the forefront.

Yet, these forebears gave modern-day feminists insights and a theoretical groundwork on which to build. It is impossible to explore, let alone to challenge, the mechanics of oppression unless one is able to define it.

To dismiss all of the ideas of ���Second Wave Feminism��� as outdated or in any way superseded is premature and foolish. Advanced patriarchal capitalism has a habit of incorporating all rebellious social protest movements into its status quo. Rather than hang on gibbets, it absorbs.

I remarked (under my real name) on that post in ���The Ladies Finger���: ���Do I normally have a sense of humour? Well, I think it sometimes wobbles under patriarchal advanced capitalism’s ability to transmute all threatening social movements into window dressing and vague talk of ’empowerment’.

I���m concerned that this is increasingly what is happening to a feminist movement which embraces sex roles, girly toys, pornography and pole dancing, and that this post on a feminist ezine has aroused so little contention (I was one of four women to comment) serves to strengthen my concern.

April 24, 2015

A Successful Cross-Genre Novel Without a Clear Protagonist; Georgette Heyer’s ‘The Talisman Ring’

O In the last post I was waffling on about protagonists and main characters. I gather that according to some writing advice, it���s meant to be fatal not to have a clear protagonist. What a tiresome man I know calls an ���Absolute No-No.���

In the last post I was waffling on about protagonists and main characters. I gather that according to some writing advice, it���s meant to be fatal not to have a clear protagonist. What a tiresome man I know calls an ���Absolute No-No.���

I rambled on to points of view, remarking that�� some writing advice insists that there is a shift to writing from one person���s point of view, following YA novels (goodness knows why adult novels are following YA novels, but���).

I also commented that a fair number of classic novels, notably ���A Tale of Two Cities��� don���t have a clear protagonist and depict multiple viewpoints.

Now I���d like to analyze a highly successful and enduringly popular novel that breaks all the rules above, besides the slight matter of being cross genre. Admittedly, it���s old, published in 1936, though it doesn���t count as classic English Literature unless you are a romance addict.

It���s by an author I���ve mentioned before in a post about authors who didn���t believe in what they wrote, yet who made a massive success of writing it anyway.

That���s right ��� it���s by none other than Georgette Heyer and I���ve mentioned before in this blog how I read it at fourteen, and re-read it when I was doing research on traditional historical romances that use the theme of Disgraced Earl, Framed for Murder by Conniving Cousin, Turns Outlaw.

I didn���t enjoy it myself, but I gather that ���The Talisman Ring��� is a great favourite among Heyer fans. I couldn���t be drawn into the plot, though I admired the slickness of execution, because I still found the romantic pair, though I could see that they were meant to be something of a spoof, downright annoying.

I found the Earl turned outlaw, Ludovic Lavenham, infuriatingly stupid and arrogant and his love interest Eustacie de Vauban must be the silliest heroine I have ever encountered, and that���s in competition with Charles Garvice���s female leads.

However, that is irrelevant; the point is that this enduringly successful novel has no clear protagonist and has in fact, what would be seen today as structural faults with points of view.

Purists about the need for a clear protagonist might argue that it is only because Heyer is so famous, and because it was written decades before these rigid requirements come into fashion, that this book is as popular as it is, and it wouldn���t be if it was published now.

I���m far from sure, myself.

Now I���ll do some geeky analysis (those who have no interest in analyzing light novels are entirely welcome to sneak off or go to sleep).

The action begins with a man with a truly amazing name ��� Sir Tristram Shield, no less- arriving at the Sussex castle of Sylvester, Lord Lavenham, who���s eighty and dying without an obvious heir, as his grandson is living abroad in exile in disgrace. Sir Tristram is his great-nephew; Sylvester���s got an heir presumptive, the effete Basil ���Beau��� Lavenham, another great-nephew, but he doesn���t like him for sporting lilac pantaloons with ribbons, and a quizzing glass (not politically correct, the old lord).

His grandson is the equally astoundingly named Ludovic Lavenham, a wild youngster who had to be rushed abroad two years since, suspected of murdering a dishonourable fellow gambler in order to get his prized ring back.

This bounder had taken this priceless talisman ring as surety at a gaming table, wouldn���t give it back, and was in the ill-advised habit of wandering at night in deserted spinneys, though he knew that Ludovic was a hot-tempered crack shot, full of vengeful spirits and regularly three parts drunk on the other sort of spirits.

Tristram Shield was in the spinney too and heard a shot ten minutes after he���d last seen his enraged cousin. The cheat���s body was found the next day, minus the ring and complete with a handkerchief of the heir to the earldom���s.

Tristram Shield and his grandfather hurried the miscreant out of the country. Basil Lavenham, despite the damning evidence against him, advised him to stay and stand trial. Now why might that be?

Sylvester is eager for Sir Tristram to marry his other grandchild, a girl he���s taken out of France because its 1794. She���s a great romantic and doesn���t think much of the acid and prosaic Sir Tristram, who���s thirty-one besides, even if he is muscular. After Sylvester duly passes away, she decides to run off to be a governess rather than marry him on the grounds that if she is a governess, there is bound to be a grown-up son in the household who will fall in love with her (that���s the way her mind works). Inevitably,on her setting off through the snowy night, she runs into a group of smugglers who are led by her exiled cousin Ludovic Lavenham. He insists she has to accompany him; they are chased by Excise men, Ludovic is shot and they end up hiding in an inn run by a friend of the Lavenham family.

Inevitably,on her setting off through the snowy night, she runs into a group of smugglers who are led by her exiled cousin Ludovic Lavenham. He insists she has to accompany him; they are chased by Excise men, Ludovic is shot and they end up hiding in an inn run by a friend of the Lavenham family.

Here, a woman called Sarah Thane, staying there with her bizarrely self-absorbed brother, and clearly meant to be highly sensible, comes on the scene of their arrival and helps them, taking an immediate and intense liking to the pair, and resolving at once to assist them in clearing Ludovic���s name.

He and Eustacie have already fallen in love, needless to say.

They suspect the jewellery collector Sir Tristram (who incidentally, is supposed to have a sour view of women, having been disappointed in love many years ago) as the villain of the piece. But, when he turns up he protects Ludovic from law enforcers, and says that he suspects none other than Basil Lavenham as the murderer. Well, he���s a second cousin, after all.

The rest of the story is taken up with the attempts to evade incompetent thief takers and the machinations of Basil Lavenham, who has the ring (possession of which will show he is the murderer) concealed in his house.

As there are only approximately six or seven pages of love scenes in a novel of nearly three hundred, as regards genre, this seems more of a mystery story than an historical romance.

Also, if Ludovic and Eustacie are meant to be the hero and heroine, then the romance between them is singularly devoid of the plot driving conflict romance writers insist is indispensable. He says he wants to marry her ��� she���s quite agreeable – the morning after they meet. The only conflict is that provided by external forces, which doesn���t make for much interest in the relationship.

It is arguable that they are not in fact the hero and heroine, but the ���romantic��� foils to the down-to-earth and bantering Sir Tristram and Sarah Thane.

Certainly, Tristram Shield has the hallmarks of a Heyer hero; he���s dark, saturnine, skilled at the manly arts of boxing, shooting and riding, and carries with him scars of an emotional nature.

Yet, it is also true that Heyer does have another, less frequently used sort of hero, a callow young man with the right ideas but who needs to mature, who is wild, thoughtless, headstrong, and generally tall and athletic, with fair hair and blue eyes. He is to be found as Sherry in�� another of her novels ‘Friday���s Child’. Ludovic is more or less the same character as this one, save he���s quicker on the draw.

Then again, with regard to heroines, Sarah and Eustacie conform to the types Heyer often uses, the witty, independent, slightly older, tall and statuesque woman, and the spirited ing��nue of few inches. What we seem to have is a set of two possible heroes and heroines.

So, then, ���Spot the Protagonist���: whoever is that?

It might appear to be Sir Tristram, who is the one who solves the mystery and traps the villain. But this can���t be so according to the most popular definitions, as the story is not bound up with his fate, unless that is, to clear himself of the others��� suspicions that he is the thief and murderer. Yet after all, his fellow conspirators quickly acquit him of that when he sets about trying to expose the real villain.

As Tristram doesn���t deny that he has never liked Ludovic (they are reconciled two-thirds of the way into the novel), it is certainly to his credit that he exerts himself so determinedly to clear his name. It is never made clear why he does this so determinedly, except possibly through a sense of justice and a desire to clear the family name. There does, however, seem to be an strong bond between the two male and rivalrous cousins, all the more smouldering for being unstated.

In fact, if there is emotional intensity in this novel, it is not between the opposite sex couples, but between Tristram Shield and Ludovic, a passionate sort of love hate relationship: –

������Damn you, take your hands off me,��� Ludovic whispered.

Sir Tristram paid no heed to this, but obliged him to drink some of the water. He laid him down again, and handed the glass to Miss Thane. ���Listen to me,��� he said, standing over Ludovic, ���I never had your ring in my hands in my life. Until this moment I would have sworn that it was in your possession.���

Ludovic had averted his face, but he turned his head at that. ���If you have not got it, who has?��� he said wearily.

���I don���t know, but I���ll do my best to find out,��� replied Shield.

When he does find the famous talisman ring – in Basil���s quizzing glass, where else-

Shield���s graceless younger cousin breaks into an emotional speech of thanks intriguing in its implications: –

���There is nothing I can say to you, Tristram, except that I could kiss your feet for what you have done for me.���

As Ludovic Lavenham���s fate is what the story is about, he must surely be the protagonist, according to common definitions of that role. But he is a singularly thinly drawn main character. He is roughly sketched in as a reckless young man, supposedly charming and handsome with ���a commanding air��� (shades of Heriot Fayne in Garvice���s The Outcast of the Family). We don���t even know the names of his late parents or what his relations with them were (for convenience, all the parental generation in this story have been killed off save Tristram���s widowed mother). The reader is clearly intended to find him charming, just as she is meant to find Eustacie sweetly ingenuous, but that requires much patience.

The reader is clearly intended to find him charming, just as she is meant to find Eustacie sweetly ingenuous, but that requires much patience.

For instance, the Conniving Cousin obligingly tells Tristram Shield that his house will be empty on a certain day, and that the library window needs fixing. Tristram laughs at the crudity of this ploy, but Ludovic rushes into the trap, with his protector close on his heels to rescue him.

Again, protagonist or otherwise, at the climax of the story Ludovic is locked in the cellar in a sort of symbolic imprisonment (where for his security the landlord and Sir Tristram have insisted on keeping him for several days), and in fact the story ends before he even emerges.

All this seems odd in a protagonist, when the Wicki definition assures us that we must empathize deeply with one, while the main character is intended to provide mainly interest and excitement.

Again, he is the only character who is purely ���seen from outside���. Although it is certainly true that we have little access to the inner lives of any of the characters in this book, we have some insights into the thoughts of the other three main characters (though mercifully few in the case of Eustacie). Still, we are never told what is taking place in Ludovic���s head at all.

Of course, it is perfectly possible to draw a main character and not to give any access to his or her mental processes, thereby enhancing mystery, but there is nothing mysterious about Ludovic, and one is forced to conclude that Heyer wisely refrains from giving the reader access to the inside of his head largely because it is empty.

The reader, however, is clearly meant to sympathize with him and Eustacie, and to care about their fate; how far this is true for most readers I don’t know, but I found myself unequal to that.

Sir Tristram, then, seems to be the hero ��� not the ���False Hero��� I have read of, but a ���False Villain���. We never get to know him particularly well, partly because some of his actions are designed to take the reader by surprise.

We are not told, in fact, what the unromantic pair makes of each other until the end, although of course, the reader is lead to guess.

These, then, are some of the issues that intrigue me about this perennially popular ���Regency��� (in fact, late Georgian) romance. The peculiarities of the plot, the confusing combination of seemingly two heroes and two heroines, the high proportion of mystery to the romantic detail, all seem to indicate something shocking ��� dare I say it of so polished, professional and detached a writer as Georgette Heyer ��� that she had done what is regarded as literary critics as ���An Absolute No No��� and ���Lost Control of Her Material���.

This is, of course, practically a literary equivalent to losing control of one���s bowels. Still, Heyer is in distinguished company. The charge has been leveled at Elizabeth Gaskell in the melodramatic third volume of ���Sylvia���s Lovers��� and at Pushkin in the second half of his robber novel ���Dubrovsky���.

To me this seems the only explanation for the strangely unsatisfactory balance in this story; it is as if Heyer set out to write a vaguely Gothic spoof of romantic themes (both romantic in the modern sense of he word and the eighteenth century one which incorporates adventure). Perhaps, Jane Austen admirer as she was, in the contrasting two pairs of lovers she envisaged a sort of adventurous equivalent to ���Sense and Sensibility���. Possibly she started the novel intending to focus most of her attention on the romantic couple, but subsequently lost interest in them, and allowed the down to earth ones to take over the action and resolve the plot.

I found these issues a far more interesting mystery than the one concerning the whereabouts of talisman ring.

One thing is certain; despite the lack of a clear protagonist, and whatever might be seen by modern literary pundits as structural faults, ���The Talisman Ring���, at seventy-nine years old,�� is number fifty in the historical romance category on Amazon.co.uk.

April 17, 2015

The Vexed Issue of Protagonists and Main Characters

I���ve been reading a bit about protagonists recently.

I���ve been reading a bit about protagonists recently.

I have to say, that while I should have learnt a lot, in some ways I���m none the wiser. Lets start with the ���Wickipedia��� definition:

The protagonist (from �������������������������� (protagonistes), meaning “player of the first part, chief actor”) or main character is a novel or drama’s central or primary personal figure, who comes into conflict with an opposing major character or force (called the antagonist).[ The reader is intended to mostly identify with the protagonist���

The terms protagonist and main character are variously explained and depending on the source, may denote different concepts. In fiction, the story of the protagonist can be told from the perspective of a different character (who may also but not necessarily, be the narraotor). An example would be a narrator who relates the fate of several protagonists – perhaps as prominent figures recalled in a biographical perspective.

Aspects

Sometimes, antagonists and protagonists may overlap, depending on what their ultimate objectives are considered to be. Often, the protagonist in a narrative is also the same person as the focal character though the two terms are distinct. Excitement and intrigue alone is what the audience feels toward a focal character, while a sense of empathy about the character’s objectives and emotions is what the audience feels toward the protagonist. Although the protagonist is often referred to as the “good guy”, it is entirely possible for a story’s protagonist to be the clear villain, or antihero, of the piece.

The principal opponent of the protagonist is a character known as the antagonist, who represents or creates obstacles that the protagonist must overcome. As with protagonists, there may be more than one antagonist in a story. The antagonist may be the story’s hero; for example, where the protagonist is a criminal, the antagonist could be a law enforcement agent that tries to capture him.

Sometimes, a work will offer a particular character as the protagonist, only to dispose of that character unexpectedly, as a dramatic device. Such a character is called a false protagonist. Marion in Alfred Hitchcock���s Pscyho 1960) is a famous example.

When the work contains subplots, these may have different protagonists from the main plot. In some novels, the protagonists may be impossible to identify, because multiple plots in the novel do not permit clear identification of one as the main plot, such as in���Leo Tolstoy���s War and Peace depicting fifteen major characters involved in or affected by a war.

I may be particularly obtuse, but all this didn���t seem to gell with the punchy advice given on an interesting blog Advanced Fiction Writing by ���America���s Mad Professor of Fiction Writing���.

ww.advancedfictionwriting.com/blog/20...

A follower asks:

Can your novel have more than one protagonist? If so, can they be enemies? Is doing that a no-no, a may-be, or a why-not?

Randy sez: You can do anything you want in a novel. However, you can���t make a publisher buy your book and you can���t make readers care. Those pesky publishers will buy what they think the public will buy. And the public will only buy books they like.

Here���s the thing: Readers want to know who to root for. When you give them two people to root for, you cut the emotional impact in half.

This is a case where 1 + 1 = 1/2.

When you give your reader two people to root for, and they���re enemies, then things are even worse. Now your reader is confused. Is it good that the bomb blew up Reginald���s helicopter, or is it bad? Is it bad that Reginald wasn���t in it, or is it good?

This is a case where 1 ��� 1 = 0.

It���s like trying to drive with your foot jammed down hard on both the gas and the brakes.

If you���re reading a novel or watching a movie, you want to root for one character or at least one group of characters who are all on the same side. Treat your reader like you want to be treated. Choose one protagonist. Choose one antagonist. Make them duke it out. Make them keep duking until there���s a clear winner.

The alternative is to have no readers and get no publishing contracts.

Oh, dear. Doesn���t sound good. We���d better avoid that at all costs. Certainly, this is about as succinct as could be, and seems to bear out what I���ve heard on the grapevine, that there is a trend towards readers, following the influence of fairly simple YA plots, not wanting the ���big picture��� and multiple POV���s of classic novels, where sometimes exactly who was the protagonist wasn���t at all clear.

For instance, on these, I���m sure I don���t know who is the protagonist of Dickens’ ���A Tale of Two Cities���. Is it Dr Manette? He, a slightly unbalanced middle aged man, is hardly the ideal type of hero, whatever his moral qualities of magnanimity and courage. Neither does he act very decisively in the main part of the story.But is the colourless Charles Darnay – who as one critic comments, only comes to life when he���s on trial and in danger of being executed – the protagonist? Again, it���s hard to believe that Dickens intended the protagonist to be the drunken, debauched and hopeless Sidney Carton (why he is so hopeless is never made clear to the reader). As we may be sure it is not the female lead, Lucie Manette, who is if anything even more insipid than Charles Darnay, we are left with a puzzle.

Hamlet is an obvious protagonist, and one who has multiple antagonists, including the weaknesses in his own personality. I admit that I seem to be unusual in finding him decidedly unsympathetic; perhaps it���s partly because the play was one of the set texts at ���A��� level, but for a Shakespeare geek I never have been able to appreciate this great work properly through my resentment of Hamlet���s foul treatment of Ophelia, followed by his hysterical behaviour at her graveside. On the whole, my sympathies were for some reason with the treacherous Laertes.

There is the whole question of the fact that a protagonist does not have to be admirable, though surely this main character has to generate interest if not sympathy, or nobody would bother continuing with the story.

For instance, another website comments on a disgusting protagonist, Humbert Humbert from Vladimir Nabakov���s Lolita (as I���ve never been able to bring myself to read this, I have to rely on a quote from a site of literary criticism here): –

Humbert Humbert is an example of a truly despicable protagonist, as well as an unreliable narrator. The middle-aged literature professor tells the story of his obsession with his 12-year-old stepdaughter, with whom he becomes sexually involved after the death of her mother. Knowing that he will be judged harshly for his actions, Humbert Humbert appeals to the empathy of his readers, though Nabakov makes no such attempt to portray him as a likeable character. He is a relatively unusual protagonist for whom the audience has almost no sympathy.

I seem to be floundering into deeper and murkier waters here; hopefully, few people would be likely to wish to write such a novel from the point of view of the abuser these days, and would also hopefully have great difficulty getting it accepted by publishers or allowed on self publishing sites if they did; but that is quoted to show how varying are the views about what constitutes the protagonist of a novel…

Yuk, all this is so convoluted, and for once, I can���t quote James N Frey for the simple reason that my notes on his excellent works on writing novels don���t have any reference to creating protagonists; I must have mislaid that bit…

Finally (sorry, everyone for a blog post as long and indecisive as one of Hamlets soliloquies, and less philosophically intriguing) I liked this advice on this website: –

http://thewritepractice.com/protagonist/

The protagonist can also be called the hero or main character, but these terms are imprecise, and for some stories, plainly false. The protagonist of Macbeth, for example, is clearly not a hero. Nick Carraway is the main character of The Great Gatsby but he is not the protagonist.My favorite definition of the protagonist is from Stephen Koch���s Writer���s Workshop:

The protagonist is the character whose fate matters most to the story.

The protagonist centers the story. She defines the plot and moves it forward. Her fate determines whether the story is a tragedy or comedy.

You may not know who your protagonist is until you are halfway through writing your novel. You may think your protagonist is one character, only to find out your villain is actually your protagonist. You do not need to know who your protagonist is before you begin writing, but as you look at your work in progress, ask ���Whose future is most important to this story, to the other characters in this story? Whose future is most important to me?��� If you can answer these questions, you have found your protagonist.

How to Characterize a Protagonist

How do you make a protagonist more interesting? How do you bring depth to the protagonist���s personality?

The best way to characterize the protagonist is through an antagonist. An antagonist, or villain, is not necessarily evil or ���the bad guy.��� Instead, the antagonist is the protagonist���s opposite, their shadow or mirror.

The human mind loves to compare. It especially loves to compare people, and by characterizing your antagonist, you naturally create a comparison that characterizes your protagonist.

Here���s a trick:���The stronger you make the antagonist, the better your protagonist will look when he wins. The more you increase the values of your antagonist, the more interesting your protagonist becomes.

Is There Only One Protagonist?

While there is usually only one protagonist in a story, this isn���t always true. In romantic comedies and ���buddy stories,��� there can be two protagonists. For example, in Romeo and Juliet it is the fate of both characters, not just one of them, that matters to the story. Same with Lethal Weapon and The Odd Couple.

I love stories with multiple viewpoint characters��� which have multiple characters who could be protagonists, but while the stories begin with several possible protagonists, by the end, the author has led you to just one or two.

The Most Important Requirement for the Protagonist

This is the single most important element of your protagonist, and thus one of the most important of your novel as a whole. If your protagonist fails to do this, your story will fail. Seriously.

Your protagonist must choose.

A character who does not choose her own fate, and thus suffer the consequences of her choice, is not a protagonist. She is, at best, a background character.

Donald Miller says story is, ���A character who wants something and is willing to go through conflict to get it.��� If your character does not want something enough to choose to go through conflict to get it, your reader will walk away disappointed.

Your protagonist may reject the choice at first. She may debate back and forth between which option to choose. She may spend a hundred pages waffling. This can actually be a good thing. Choice is hard! However, she must choose.

Readers will bear with a protagonist who isn���t very likable. They will endure selfishness, pride, and even cowardice in a character. However, readers will not endure a protagonist who does not decide.

I think that���s enough for me on this, at lest for today, and I haven���t even explored the concept of the anti-hero(ine), the false protagonist, the issue of multiple points of view and all the rest of it.

(Exit, burbling of definitions and literary theory���)

April 8, 2015

The Brilliant ‘Bodily Harm’ by Margaret Atwood Revisited

Recently, I broke off from my ongoing good old independent research into romantic novels (and if anyone reading this has read anything recent on the topic of women���s escapism and reading romances, do let me know). Finding Margaret Atwood���s Bodily Harm on the shelves of someone I was visiting, I pounced on it and re-read it in a couple of days.

Recently, I broke off from my ongoing good old independent research into romantic novels (and if anyone reading this has read anything recent on the topic of women���s escapism and reading romances, do let me know). Finding Margaret Atwood���s Bodily Harm on the shelves of someone I was visiting, I pounced on it and re-read it in a couple of days.

Now, I���m going to indulge myself and write a review of it.

It���s a funny thing; it���s much easier to write a review of a book of which you have some criticisms ��� but one which you regard as astoundingly well crafted leaves you almost wordless, or it does with me, anyway.

At the end, I just put the book down and used an expression I hate and despise: I said, ���Wow!���

Of course, it does happen to be a book raising themes about which I obsess ��� political corruption on a global scale, lives spent in vapid preoccupation with superficial concerns and consumerism, and how the sexual abuse of women fits into these areas.

That all sounds very high falutin���. But in fact, these weighty issues are introduced

with so skilful and light a touch that you are hardly aware of their intrusion as the scene is set out, until you see the protagonist, the young Canadian���lifestyle��� journalist Rennie Wilford suspected by the CIA of being involved in a failed coup on a little known Carribean island, served salted tea and made to defecate n a bucket while her fellow prisoner allowing herself to be sexually abused by the guards in returns for news of her lover.

I was puzzled, the first time, why the story begins with the words: – This is how I got here, says Rennie. Then the account starts: It was the day after Jake left���

Rennie returns home to find the police in the flat where she has lived alone since the break up with her lover (he���s been unable to cope with her loss of part of her breast through a cancer operation) . A man has broken in, and sat drinking ovaltine while waiting with a rope. He escaped the police, who warn Rennie about bringing men back and closing the curtains when she undresses, etc.

The horror of what might have happened – Rennie thinks of it in terms of a game of Cludo, not remembering if you use the killer or the victim���s name in that: – Miss Wilford, in the bedroom, with a rope�� – drives her to ask the magazine she works for a travel assignment somewhere abroad.

Rennie doesn���t want to face her pain; she���s lost part of her breast, her lover, and her confidence that she can lead a life apart from responsibility and suffering; these were the defining features of her unlucky mother���s wasted life spent in a religion obsessed small town in Ontario, deserted by her husband and caring for a mother suffering from early onset dementia.

She avoids deep feelings:- Falling in love was a bit like running barefoot down a street covered with broken bottles and it is partly this which she finds so appealing in a love affair with the attractive, sophisticated successful young entrepreneur Jake, who will not tell her what���s going on in his head, but who worships her bottom. They don���t talk of love, but they fall in love anyway.

She was warned about him on the day she met him by a jaded photographer: – A prick���There���s only two kinds of guys, a prick and not a prick���You���re just jealous, Rennie said. You wish you had teeth like that. He���s good at what he does.

Jake calls Rennie his ���golden shiska��� but once she has part of her breast removed, he becomes impotent and she can���t bear to be touched. Yet she feels a desperate longing for the unglamorous doctor who did the operation, who won���t have a physical relationship with her either, in his case through scruples about his married status.

Yet, Rennie and Jake’s sexual problems pre-date this; Jake likes to act out rape scenarios, leaping on Rennie from behind doors when she comes into the flat. Rennie goes along with these as harmless fantasies by which a sophisticated woman need not be troubled. Then,�� when as part of an assignment on pornography as art she has to view a collection of pornographic articles and films seized by the police, she becomes uneasy.

I wondered, as I read through this book, whether the unknown intruder was in fact Jake; Rennie never suspects him, and we are never told; but with typical Atwood understatement, the idea lurks unexpressed in the background of the story.

On the island of St Antoine (the name, of course, of one of the most militant sectors of Paris during the French Revolution) Rennie meets another reserved and ungiving man, Paul, enigmatic and with the shadiest connections and addicted to danger, with whom she starts a ���holiday affair���.

Don���t expect too much, he tells her.

Strangely enough, Paul, who seems unlikely to give Rennie anything but the ability to enjoy her body again (which is after all, not such a little thing) gives her the ultimate gift; he dies in trying to rescue her from hostile forces in the web of insurrection and intrigue

into which she has been pulled:- She can hear the sound of the motor launch receding, no more significant than the drone of a summer insect. Then there���s another sound, too loud, like a television with a cop show on it heard through a hotel wall. Rennie puts her hands over her ears���

Paul���s attempt to get Rennie to safety has failed; along with the girlfriend of the leader of the doomed and naive insurrection, she���s arrested, suspected of gun running. In the filthy conditions of the prison, she and Lora begin to talk, and this is why the novel is told in retrospective accounts by Rennie, who is talking to stave off her terror, her fear that she will never get out.

She tells Lora of the break-in by the pervert. Lora���s response shocks her: I���d rather be plain old raped; as long as there���s nothing violent. She comes from a background of sexual abuse and places no value on giving her body to men. She disgusts Rennie by allowing the guards sex in the hope of getting news of her lover, the leader of this hopeless insurrection,�� that has beenmonitored by the CIA from the beginning.

On finding out that the guards have been lying to her, and that ���The Prince of Peace��� is already dead, Lora attacks the guards in hysterical fury, threatening to denounce them for their own corruption. They beat her to death: – After the first minute, she���s silent, more or less, the two of them are silent as well, they don���t say anything at all. They go for the breasts and the buttocks, the stomach, the crotch, the head, jumping, my God, Morton���s got the gun out and he���s hitting her with it, he���ll break her so that she never makes another sound. Lora still twists on the floor of the corridor, surely she can���t feel it any more but she still twists, like a worm that���s been cut in half, trying to avoid the feet, they have shoes on, there���s nothing she can avoid.

When they���ve finished, when Lora is no longer moving, they push open the grated door and heave her in. Rennie backs out of the way, into a dry corner���There���s a smell of shit, it���s on the skirt too, that���s what you do���The older one throws something over her, through the bars, from the red plastic bucket. She dirt herself, he says, possibly to Rennie, possibly to no-one. That clean her off. They both laugh.

Hands, and their uses, play a large part of the imagery in this book. Rennie���s confused grandmother feared that she���d lost her hands somewhere. Now, in this climax of the novel, the once detached writer of articles on fashion and furniture, almost as bemused by horror as her grandmother once was by brain deterioration, believes she can use hers to bring Lora back to life: –

She���s holding Lora���s left hand, between both of her own, perfectly still, nothing is moving, and yet she knows she is pulling on the hand, as hard as she can, there���s an invisible hole in the air, Lora is on the other side of it, and she has to pull her through���

Rennie is released. A man from the Canadian embassy has negotiated her release. He asks her not to write anything about her experiences on the island or in the prison as the situation on the island, which is ���still volatile���.

Rennie agrees; now she sits on the plane going home. A middle-aged man tries to pick her up, asking her about her holiday, commenting on her lack of a suntan. She tells him nothing, of course: –

She knows when she will not be believed. In any case, she is a subversive. She was not one once, but now she is. A reporter; she will pick her time; then she will report.

For the first time in her life, she can���t think of a title.

Now Rennie knows that she both has been rescued, and never will be. She will no longer try and believe that she is exempt from life���s pain; instead she sees herself as lucky and buoyed up with this new luck.

I may have written a complete spoiler in trying to depict the brilliance of the powerful writing in this disturbing, bitterly funny, expertly crafted and terribly believable novel. However, as it was first published in 1981, it surely counts among Margaret Atwood���s collection of classics.

I deliberately didn���t read any of the literary criticism or general reviews on it while writing this post, but now I���ve glanced at some of the reviews on Amazon. They average at 3.2 stars, with more purchasers awarding a one star review than those giving a five star.

I had very little respect for Amazon���s star rating system for books before; now I don���t have any.

However, the comment of the woman to whom I gave the book as a present when I first read it, is unfortunately instructive ���Too stark���.

Realism doesn���t generally make for a popular read.�� Well, back to my research on women’s escapism and romances…

March 30, 2015

Plasticity and Evolving Characters

Originally posted on Sophie de Courcy and More:

Originally posted on Sophie de Courcy and More:

A year or so ago I took some time off from reading a selection of the classic robber novels -ie ���Rinaldo Rinaldini��� and ���Rob Roy��� ��� for a change of genre with Elizabeth Gaskell���s ���North and South���.

A year or so ago I took some time off from reading a selection of the classic robber novels -ie ���Rinaldo Rinaldini��� and ���Rob Roy��� ��� for a change of genre with Elizabeth Gaskell���s ���North and South���.

What interested me particularly about this book ��� though it���s a good read anyway, all about the terrible conditions in cotton manufacturing in mid Victorian Manchester ��� was how it illustrated how character types can be used and reused by the author.

They are an awkward lot, these characters! Quite apart from the fact that they take on a life of their own in one story (I don���t mean in the Aleks Sager���s Demon sense, Aagh! I mean within the pages of the novel) they can resemble viruses ��� they can mutate, and split into many.

I recognized two types in this book which Elizabeth Gaskell was to use again.

The first is���

View original 925 more words

March 23, 2015

A Yuk, Yuk Topic – Writer’s Block

The dreaded Writer’s Block. That’s a Yuk, Yuk topic indeed.

The dreaded Writer’s Block. That’s a Yuk, Yuk topic indeed.

All writers dread it. It���s supposed to happen to every writer ��� but many seem as reluctant to admit to it as they are to having sweaty feet or sending round robins at Christmas. Well, I’ve been known to have sweaty feet,but may the day never come when I send out a round robin…

There are a number of posts about writers��� block.

How do I know ��� well, I er ��� a friend of mine had it, that���s it���

No actually, I had it myself (general exodus in case it���s catching).

I had it for weeks. (Shouts defiantly) I had it for weeks! And most of these posts assume you’ll only have it for days.

Perhaps it partly depends on what you call writer’s block. I was writing stuff, but it didn’t serve to forward the plot properly; it wasn’t compelling; the creative urge never took over, making me write something that seemed to come from nowhere; generally, it felt flat, and contrived.

A writer friend was suffering from terrible editing difficulties at the time, and said it was nearly as bad, but I couldn���t agree; at least she���d written stuff that forwarded the plot. I couldn���t.

I���ve had it before. I had it with both ‘Scoundrel’ and ‘Ravensdale’ tantalizingly near the end, when I couldn���t work out how to bring all the main players together for the grande finale. I went on for maybe two weeks, and then I woke up one day with it all so clear to me and so obvious that I marveled that I hadn’t been able to work it out before.

But that was when I was ninety per cent done. Here I was only halfway through a novel, with the greatest dramas to come and the resolution nowhere in sight.

I���ve just had a quick look at the cures recommended. Now, all the things that they recommend, I tried: –

Walking and Exercising (I���m a goody-goody; I do both every day). Didn���t do any good.

Making a cup of tea/coffee (I���m too addicted to tea not to make it constantly anyway). Had no effect,and I made enough cups of tea to fill a swimming pool.

Playing music: I do that every day anyway, too, and often baroque, which is meant to make the two sides of the brain (my what?) work together. Didn���t work.

Indulging n a treat like a fudge sundae:�� I do that too often anyway, and sorry to sound self-righteous, but I don’t think comfort eating is a way out of creative blocks. If I’d had a fudge sundae every day I was uninspired, I’d have ended up not only with writer’s block, but a fat bum to make life perfect. Still, my mother always said of my father and I that we wouldn’t turn a hair about most forms of over indulgence or debauchery, but when it came to someone overeating –�� now that would provoke a storm of disgusted condemnation with some amateur Freudian talk about repression thrown in.

Keep on trying to write through it; write anyway; just write: I did, and what I churned out didn���t further the plot. It was just so much padding, which would have been fine in the days of those Victorian three volumes but no good now.

…And all the rest of it. One writer even suggested affirmations. Now, I know that you don���t have to be a follower of New Age thought to believe in affirmations, and that athletes routinely use them (and I can see, looking back, that I even used visualisation myself in my long ago days as an athlete of sorts); after all, they are supposed to work directly on the uncritical but highly powerful unconscious. Still, that I didn���t try; I just can���t take standing there coming out with them seriously.

One writer remarks that you won���t overcome writer���s block by reading posts about overcoming writers��� block; well, I���d followed that advice before I even knew about it.

In the end, I had to admit it. My problem was partly a loss of faith in the work. It was a problem with the whole structure of the story and my ambiguous feelings towards it.�� My topic is a ���difficult one to write tastefully��� and a real minefield anyway, and I���d gone wrong somewhere earlier on, and the whole thing needed re-writng. On the excellent advice of my ever brilliant writing partner, Jo Danilo, it���s gone in a drawer for year for my old unconscious to mull over.

The Villainous Venn has been left frozen in time as he rushes off with a savage laugh and Clarinda’s godmother’s all revealing magic mirror in his hands, one of the ubiquitous bribed servants at his heels… Yes, it’s a gothic with strong elements of satire.

After fifty thousand words, admitting to temporary defeat is a little tiresome, but there we are.

However, I���ve returned to sequel to ���That Scoundrel ��mile Dubois��� which I���d abandoned after 7,000 words in my eagerness to start on this new project. Whispers: the writer���s block has lifted ��� for the present.

(Hectoring voice of internalized conscience: That comes of chopping and changing. See where it leads you ��� to so much wasted time).

Ah, and I thought there was some excellent advice on a blog I found on writer’s block

http://goinswriter.com/how-to-overcome-writers-block/

Finally, if all else fails, the only thing you can do really is keep on writing. One way or another, that will solve the problem over time (if only, as in my case, through your realizing that the whole story needs a rethink and a rewrite).

Ah, and I did like another piece of advice from the post where the recommendation for comfort eating�� brought out my shocked disapproval; to write something ridiculously incongruous about your characters; in my case, perhaps the villainous Venn losing his wiry frame to the charms of fudge sundaes (if they had them in the eighteenth century). Well, after all, I have said in a previous post, someone ought to start writing those romances about BBM’s (Big Beautiful Males) to complement the BBW’s (Big Beautiful Women).

March 16, 2015

‘The Lament of Sky’ by BB Wynter review

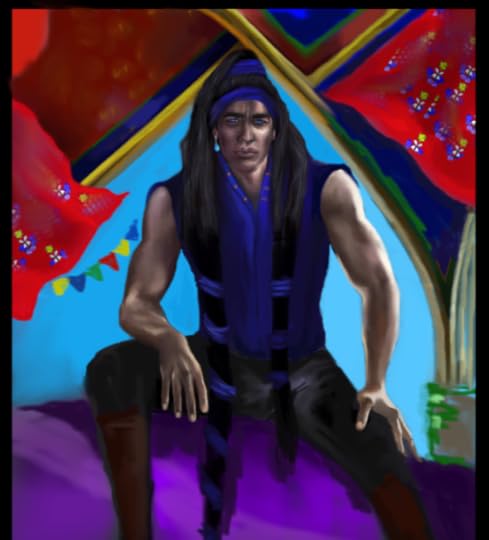

Here’s a portrait of Sky, one of the main characters in BB Wynter’s intriguing fantasy, ‘The Lament of Sky’.�� I’m envious, as it was painted by the author. I’ve always longed to paint my characters, but I lack the talent.

I hardly read any fantasy; I know I should, especially the dystopian stuff, as I’ve heard there is some brilliant work out there with strong female leads if you look about. I came on the novel almost by accident, and I was fascinated, particularly as the writer is so young, with a whole lifetime ahead of her to extend her already remarkable talent further.

I found this dystopian fantasy enthralling, and I’m not exactly easy to enthrall.

The setting is an alternate reality which depicts an environment of forests surrounding industrialized cities with an approximately late nineteenth century stage of technological development. Here a regime of insane viciousness indulges in tyranny over a brainwashed population; criticizing the great Fhyniix is punishable by death ��� and a horrible one at that: –

���The profuse smog cast a sickness upon the cornflower buildings and the sky had forfeited its colour to a repugnant, dreary grey���’

A public announcement blares out: – “All must drop every task and pray in servitude to the Vildarii. Give thanks for the freedom bestowed on you���A very, very naughty citizen, the writer Frederick Widaston, was found with a piece of paper on his person, which speaks words against the third Valdarii Marko. Why insult our holy lord gods? It is malicious bullying and persecution against our beliefs ��� beliefs that preach only peace and love��� The execution will be in two hours; that���s two hours, folks! Don���t miss it; refreshments will be available, free of charge. Now isn���t that nice!���

Of the ruling Vildarii, Marko is elusive, but hideously powerful. We meet the sadistic, golden eyed Fhyniix, whose posters are plastered throughout the cities. William, the sole surviving (and now deranged) Duwaiu, explains to Lilyth, the last remaining member of the tribe of the Amazonian Rhai Angoff, whom he has rescued from an amnesic existence trapped on a hell plain, how it is Fhyniix���s goal to draw enough evil energy from tyranny and suffering to draw the world and all the spiritual realms into an eternal hell plain.

The unknown first Vildarii? Ah, he���s the most intriguing of them all, and we certainly meet him, but I can���t describe him, because that would be to write a spoiler. I���ll just say that he is a totally unexpected and wonderful creation too.

This story is full of tension and fearsome desolation, both emotional and physical, of fearsome battles with psychic entities, of visions of a world become deranged, of grotesquely funny incidents and larger than life characters. The prose style is, I think, the most original I���ve come across; like Dylan Thomas, the writer often flouts the conventional grammatical rules and makes it a strength and not a weakness.

Lilyth, the female lead (she isn���t quite human) is a wonderful creation, strong and independent, brave and honourable, witty and a huge relief after too many hours spent reading about women who leave the battling to the men. She���s very distinctive looking, possessing both silver hair and eyes, and a very pale face, and has to go disguised, as her wanted poster is everywhere.

William, who runs his subterranean revolutionary ���Clandestine��� with astounding savagery, is an equally arresting figure, with his massive build, strange tattooed almost maroon skin, jutting cheekbones, beady black eyes and mane of auburn hair, plaited with ornaments.

He also possesses some truly disgusting rugs: –

���A litter of distasteful patterns between vibrant green pillows that were scattered alongside covers exploding with heavy embroidery. Vomit could only improve his choice of interior decoration.���

That was one of the things I enjoyed most about this book; the wonderful humour; Lilyth, on seeing some dilapidated tree houses belonging to a group of people turned cannibal in the forest, remarks succinctly, ���What a load of crap���, and that���s typical of the wonderfully debunking style that runs throughout. Typically, too, she nicknames the magic being whom she meets in the forest a ���cabbage fairy��� a title he doesn���t much appreciate.

I haven���t yet mentioned the jester Vergo, with his wildly uncontrolled libido and pervasive streak of cowardice, but remarkable loyalty. Lilyth first meets him getting drunk in a tavern, which is his favourite activity besides the inevitable one; he sometimes sleeps in bins; he���s always getting into trouble, and he���s madly jealous of the ���cabbage fairy���.

This fantasy is anything but happy-ever-after stuff. It���s a strongly written, uncompromising tale of a battle between good and evil, but with both sides getting dirty hands in the process. Beneath the fantastical images, it makes serious points about political and religious indoctrination, freedom and tyranny.

Highly recommended by sourpuss.

Here’s the links

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Lament-Sky-BB-Wynter-ebook/

March 10, 2015

Tantalizing Tasters and Sizzling Starts

A writer friend commented apropos the current demand for a fast start and quick moving action how, ���These days we���re all expected to write penny dreadfuls.���

Those Sizzling Starts, those Tantalizing Tasters, are surely far worse than the endings as a source of torment to the writer. After all, they are your hook to draw the reader in.

James N Frey is as down to earth as ever on this, advising that you must start the story where the main action begins and not before (though you can have an exciting fast forward by way of allure, you must remember that the reader doesn���t know the characters yet, and won���t feel for them in their moments of crises, though hopefully s/he may be curious).

But where dos the main action begin, exactly, I have often asked stupidly? At the bus stop where Zerina thinks she sees a wolf, or when it starts to follow her home, or when she offers it a bowl of chappie, or when with a bitter howl and a flash of thunder, it turns into lean and hungry looking man who seizes her shoulders with taloned hands to say that he has watched her at the local Adopt-A-Wolf society meetings?

(Does anyone care to write then next bit? No? Whyever not?)

Thinking about all the pitfalls of those beginnings, and about the classics that I���ve read or re-read over the past year or so, naturally enough of those the original ���penny dreadful��� comes to mind, the classic robber novel, ���The History of Rinaldo Rinaldini, Captain of Banditti��� (1798) by Christian August Vulpius.

This surely must be one which gets right into the action at once.

This book is described on Wickipedia as: – ���A typical “penny dreadful��� of the period, it was often translated and much imitated, but unrivaled in its bad eminence.���

That���s a wonderful way of putting it.

This stirring tale begins with Rinaldo Rinaldini, with typical histrionics, lamenting his fate in becoming an outlaw to one of his fellow brigands: –

���The boisterous winds rolled over the Appenines like the mountain waves of the ocean; and the aged oaks bowed their lofty heads to the storm; the night was dark, thick clouds concealed the moon and no cheering star twinkled in the heavens.

Altaverde: This stormy night exceeds everything that I have ever witnessed!

Rinaldo, are you not asleep?

Rinaldo: I sleep! I like such weather; it rages here and there, around us, close to us, in this breast of mine and everywhere!

Altaverde: Captain, you are no longer the man you were.

Rinaldo: ���Tis true. Once I was an innocent boy, but now ���

Altaverde: You are in love���.���

This certainly is getting straight to the heart of the matter ��� if you���ll forgive the pun ��� and we are to learn that Rinaldo hopes to delude the innocent young girl he���s fallen for by hiding his outlaw status from her.

Incongruously, the narrative pauses immediately after this scene setting, and there follows a moral debate between Rinaldo and his follower that is probably too extended for modern taste, lasting for three pages and concerning the hero���s feeling that he can do no good even as a morally scrupulous outlaw.

This moral digression is, I am sure, unusual in a penny dreadful, though I have only read extracts of others, and was probably inserted by the author as an attempt to raise the moral tone of the novel and so give it a place amongst ���superior��� literature. It is rather out of place at the beginning, where we are only just getting to know the hero, and would certainly have been erased by a modern (and morally oblivious) editor.

After this, the action picks up quickly, as Rinaldo hears that his men have taken some mules from a traveller on his way to a local hermitage. This turns out to be none other than the grandfather of Aurelia, the girl with whom he has fallen in love. At once, a female member of the band (it seems they did have women) confesses her former love for Rinaldo himself, advising him that he can overcome his obsession with a love object. He then pays the hermitage a visit, and when some of his men break his rules to rob the place, he saves the old man���s life and has them executed.

The ingrate won���t hear of a bandit for a son-in-law and plans to send Aurelia to a convent, so Rinaldo in turn schemes to prevent this by having his men intercept Aurelia���s carriage, but this plot fails when army troops attack and decimate his hand���All this happens within forty-eight pages, so Vulpius can certainly maintain a quick pace when he has a mind, lavishing on the reader battles, love intrigues, magical appearances, ruined castles, captive maidens and secret passages. It even features a group of rival brigands who escort about with them a group of skeletons by way of display.

I complained in a last post on satisfying and dramatically effective endings about�� my disappointment with the ending of another novel ��� gothic but written with infinitely more skill ��� ���Wuthering Heights���. It���s only fair to emphasize here how impressed I have always been ��� along with countless others – with the beginning, which takes us so effortlessly into the story and introduces a main character at once: –

���I have just returned from a visit to my landlord, the solitary neighbour I shall be troubled with���

���Mr Healthcliff?��� I said.

A nod was the answer������

We are introduced at once to Heathcliff and the forbidding household of Wuthering Heights. This gothic story, then, begins as quickly as any penny dreadful, though the writing is of course, far superior, and the evocation of atmosphere, the depiction of character and conflict and the understanding of the spiritual issues involved, naturally far deeper.

���Frankenstein��� (1817), too, starts with a very stirring scene: –

���August 5th 17..

To Mrs Saville, England:

So strange an accident has happened to us that I cannot forebear recording, it, although it is probable that you will see me before these papers can come into your possession.

Last Monday (Julyh 31st) we were nearly surrounded by ice, which closed in on the ship on all sides, scarcely leaving her the sea room n which she floated. The situation was somewhat dangerous, especially as we were encompassed round by a thick fog We accordingly lay to, hoping that some change would take place in either our situation or the weather.

About two o��� clock the mist cleared away, and we beheld in every direction, vast and irregular plains of ice, that seemed to have no end. Some of my comrades groaned, and my own mind began to grow watchful with anxious thoughts, when a strange sight attracted out attention and diverted our solicitude from our own situation. We perceived a low carriage, fixed on a sledge and drawn by dogs, pass on towards the north at the distance of perhaps half a mile; a being which had the shape of a man,but apparently of giant stature, sat in the sledge and guided the dogs������

This brilliant word picture forms such a striking image that it is quite unforgettable and certainly draws the reader in at once. In another few paragraphs, we meet with the unfortunate Frankenstein too, half dead from cold, emaciated, and hunted down by his monster. Soon he begins to tell the sympathetic Captain his awful story.

The other classic novel I mentioned in my post on endings, ���Vanity Fair��� as having an ending which I found a general let down, has one of the beginnings so beloved by Victorians, and is in fact, a classic example of ���Tell Not Show��� where the author informs us all about the two female leads and what they are like. They are shown leaving their boarding school, where sweet-natured Amelia Sedley, who has everything that she wants in life including indulgent merchant parents and a marriage arranged with the handsome, dashing young officer George Osborn, has typically been the only girl to offer friendship to the socially inferior and rebellious Becky Sharp.

This first introduction to their background and characters ends with Becky throwing back the dictionary that has been given to her as a leaving present, and cursing the school heartily.; she also mentions Napoleon Boneparte favourably, and is altogether outrageous:

������Miss Rebecca, then, was not in the least kind or placable. All the world used her ill, said this young misanthropist, and we may be pretty certain that persons whom all the world treats ill deserve entirely the treatment they get���This is certain; that if the world in general neglected Miss Sharp, she was never known to have done a good action in behalf of anybody������

This paragraph reads rather like some modern say treatise on ���positive thinking��� and ���the laws of attraction���, though Thackeray���s point is intended to be a conventionally religious one; he joins with Vulpius, then, in adopting a tone of moral instruction very early in the tale.

Ironically, the rebellious and outspoken Becky Sharp soon ceases to be either; she continues to be self-serving, but metamorphosis���s within a chapter or so, the hated school behind her, into an accomplished flatterer who is ���almost always good-natured��� and never expresses an opinion that might hinder her social-climbing, admiration of Napoleon Boneparte included. She is a determined hypocrite, the sort of person who is likely to flourish in Thackeray���s world of ���Vanity Fair���.

Of course, later on there are some very stirring chapters, including a depiction of the Battle of Waterloo. These contain some of Thackeray���s strongest writing, as against the prosy tone adopted here, besides a good deal of emotional drama.

This slow starts does make me feel a bit wistful, oddly enough,and even envious, for an age that demanded a thorough introduction to each character and situation in its ���worthwhile��� literature (yes; I know such reading matter as was available to the majority through being read out to them by the literate, wasn���t of such a type). In search of those Tempting Tasters of beginnings, modern writers miss that opportunity to build up a convincing background over pages ��� now it has to be done in a few terse sentences. And as for that dreaded Tell Not Show: –

���Zarina was a nice girl, kind-hearted and with a love of animals. She cared about the environment, had a feeling for all living things, and was involved in conservation. Since her first picture book of Little Red Riding Hood she had always worn red coats; she had one on now as she glanced at the desperate eyes of the hungry wolf���. ���

March 2, 2015

Those Elusive Endings

Those ���How To��� books on writing seem generally to lay less emphasis on endings than on beginnings; of their advice about endings, I can only remember that they said that you should resolve the conflict that drives the plot and leave the reader feeling satisfied.�� James N Frey in ���How to Write a Damn Good Novel��� says that you ���must have the good climax and resolution to the story that you hinted you would deliver earlier���. That about sums it up; James N Frey���s brilliant at that.

While by definition you won���t lose the reader of that particular book by having an unsatisfactory ending, you may well for future books; he also warns against ���playing tricks with the reader���; I haven���t come across such an ending in ages, but I suppose they would be of the ���and it was all a dream��� variety.

He points out that playing ‘clever tricks’ on a reader will only annoy the reader, and it’s true. A few years ago, I read a really infuriating story that kept giving false dramatic resolutions which were then explained away as fantasies in the protagonist���s mind; after about two of these I threw the book in the charity shop box, and it was only innate meanness that prevented me from hurling it into the recycling. As I���m so stupidly stubborn it usually takes a lot to make me leave a book unfinished, I see what he means about avoiding at all costs that trick ending; the reader won���t appreciate your cleverness; the reader will feel cheated.

There���s also a problem, of course, with books that only form part of a series; the reader always feels slightly cheated here, too, in that the resolution of the main conflict hasn���t happened – yet again;�� although the author will have explained that this is in fact a series, this still remains true; and the longer the series continues, it seems to me, the greater this sense of frustration becomes. Minor conflicts driving the plot are variously resolved, but that final resolution is kept on hold; that tantalizing of the reader requires a lot of skill, like a coquette of olden times keeping an admirer on a string for months or years���

Then, there���s the whole question of the nature of that satisfactory resolution; it���s here that we see how much the imaginative world we create is just that ��� artificially constructed. After all, in real life, there are rarely satisfactory conclusions of any sort; evil doers go to their graves unpunished, at least as far as this world is concerned (the case of the infamous Jimmy Saville in he UK is a recent example); unselfish people go unrecognized; people who share true love are separated; and as often as not, wildly dramatic situations sometimes just fizzle out and defuse over time.

However much we may be prepared to accept that this is so of real life (and a lot of people aren���t) we don���t want to come across it too much in stories. We want a clear and satisfactory resolution of some sort and we don’t want our sense of justice to be too outraged; to deliver this resolution may be quite a complex matter, as these days we don���t quite believe in the same divisions between ���good��� and ���bad��� characters that seemed so clear to earlier writers (as always, Shakespeare is an exception).

Generally, though, the modern reader still doesn���t want evil doers to get off scot-free, or heroics to go totally unrecognized, or for virtue to have no sort of reward at all (even if it���s only hinted that this reward will come in the next world). There are, of course, huge differences between comedy and tragedy regarding the outcome of stories, and tragic outcomes unfortunately often come across as a lot more realistic in tone than the happy endings, which so often seem rather contrived.

Thinking back on various classic novels that I���ve read or re-read or partially revisited over the last few years, it occurs to me that in fact a number of these don���t have endings which are generally regarded as satisfactory. This is interesting; they have their supporters; but the resolution to the basic moral conflict in some of these stories is sketchy, and in other���s it is arguable that the author has made one of those seven deadly mistakes about which James N Frey warns and ���not followed through���, either through softening towards the character who has served the part of the villain of the piece, or possibly through a misguided wish to introduce an element of realism in a story not strictly speaking realistic.

I’ve said too often to need to need to repeat what I think of the unjustly good fate meted out by Elizabeth Gaskell to the unscrupulous opportunist Charley Kinraid in ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’, and I’ll go on to ‘Vanity Fair’ and ‘Wuthering Heights’).

For instance, the fate of Becky Sharp in ���Vantiy Fair��� is wholly unsatisfactory; whatever moral Thackeray wished to point in making her thrive, while most of her victims come to fairly dismal ends, one leaves the story with a sense of jaded weariness, or anyway, I did. This all seems to be in line with the strange combination of sentimentality and cynicism which characterize Thackeray���s writing, and make his general depiction of characters and the relations between them unsatisfactory, too; his good characters are for the most part lacking in any capacity to learn, it seems, from unpleasant experiences or to discriminate between admirable and contemptible love objects, while his ���bad��� characters almost invariably remain just that ��� mean and exploitative; the result is that his world is oddly static, his ‘vanity fair’ and his characters very much the theatre and puppets which he dubs it in the last sentence of the book.

A great many people admire Becky Sharp as some sort of feminist heroine ��� and while I see her as admirably independent and endowed with a justifiable contempt for the absurd injustices of the world in which she lives, I personally find her repellent, treacherous and incapable of love or loyalty as she is. We leave her living a life of smug respectability on the money she has stolen from her last victim Joseph Sedley, the one who would have been her first, had it not been for the interference of George Osbourn.

Amelia having been brutally disillusioned about her former idol Osbourn, and having found a safe haven in the arms of the Dobbin, surely one of the most boring male leads ever in literature (I can���t call him a hero as this book is sub-titled ���a novel without a hero���) all supposedly ends happily (it is only to be hoped that she doesn���t find him as physically unappealing as one might expect from her indifference to him for the previous 550 pages). After the drama in much of the previous story, I found it an anti climax.

If Becky���s fate is meant to demonstrate that ���the wicked thrive in this vale of tears��� then this is hardly reflected in the fate of a lot of other less than admirable characters, many of them quite astute citizens of vanity fair themselves, who come to dismal ends. The old lecher Sir Pitt Crawley is reduced to idiocy and tormented by callous nurses after a stroke, his sister the pseudo revolutionary Miss Crawley is only saved from pathetic loneliness in her last months by the kindness of her niece by marriage Jane, while the wretched older Sedleys eke out an existence of penury and misery. Becky���s estranged husband Rawdon  Crawley, a professinal gambler and rascal himself,�� humiliated by Becky���s betrayal, succumbs to yellow fever in a tropical island, while after his son���s death at Waterloo, the older Osborn leads a life of joyless bitterness.

Crawley, a professinal gambler and rascal himself,�� humiliated by Becky���s betrayal, succumbs to yellow fever in a tropical island, while after his son���s death at Waterloo, the older Osborn leads a life of joyless bitterness.

Perhaps Thackeray was advocating the necessity of religion to add meaning to wordly sufferings, but it has been pointed out before that all of his characters ��� even Becky ��� do in fact, profess religion.

I felt the same way about ���Wuthering Heights���; the ending doesn’t leave the reader with a sense of satisfaction. Whatever one may think about this book, it can���t possibly be said to lack excitement, drama or larger than life characters. But again, I found the conclusion to the conflict and moral issues raised lacking in any satisfactory sense of resolution. While the conflict between the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange finds a happy resolution in the love between the Hindley���s son Hareton (raised and even regarded with affection by Heathcliff, and so in many ways, his son too) and the younger Cathy, the issue of Heathcliff���s malevolence and wrong doing is never properly addressed.