Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 138

February 22, 2021

Decolonizing the COVID-19 response

Shinuya, Japan. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Shinuya, Japan. Image via Wikimedia Commons. The campaign for global immunization against the SARS-CoV-2 virus is proving tougher than everyone anticipated. The simple reason is that the world was never prepared for something like this. A combination of underfunded and disjointed health systems, dwindling vaccine supplies, and emerging variants compromising the efficacy of the available vaccines have complicated the roll-out for most countries, with many others being unable to even begin as the richest horde stock.

A key question that will be answered in the coming months is just how well the available vaccines work in the real world. Clinical trials are one thing, but gauging efficacy in the ordinary course of life (where it���s hoped that some degree of social mixing will now be restored), is another. An additional question, is how long does immunity actually last? In all this uncertainty, it���s increasingly looking like COVID-19 is here for the long-haul���which is perhaps only just a more solemn outlook on things. Managing it in the long-term would therefore require regular vaccination (and updated vaccines), at least to the extent that every country can be in a position where controlling outbreaks and developing vaccine-induced herd immunity is a feasible strategy. The ultimate question then, is whether the public health systems have the capacity for this new world.

This is a world where not only COVID-19 will linger, but where new pathogens are likely to emerge. The heightened occurrence of viruses worldwide is linked to corporate-led ecological destruction, and short of far-reaching systemic change, we will see more of them. It is therefore crucial that as we hope for the best and prepare for the worst, we draw from the experience of those administrations that have proven themselves capable of managing disease spread, but in a manner sensitive to the circumstances of their citizens. As was written by Vikram Patel and Richard Cash in The Lancet a while back: ���Context is central to the control of any epidemic, a truism we���ve known for centuries but that we seem to have overlooked in this pandemic ��� The key principles of global health are context and equity. We urge less-resourced countries to devise policies that speak to their unique demographics, diverse social conditions and cultures, precarious livelihoods, and constrained infrastructure and resources.���

This week on AIAC Talk, we���re looking at both the successes (and shortcomings) of how places in Asia and the Pacific (like Bhutan, Vietnam, Japan and the Indian state of Kerala) responded to COVID-19, widely praised as avoiding the false dichotomy of saving lives or saving livelihoods. We are interested in developing a comparative perspective that refrains from oversimplifying it to a single factor. To help us assess these countries varied efforts we���ll be joined Sakiko Fukuda-Parr, a development economist and a�� professor of International Affairs at The New School, where her teaching and research have focused on human rights and development as well as global health.

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST.

On last week���s AIAC talk, we were joined by Derek Hook, Precious Bikitsha and Phethani Madzivandhila to explore the life, thought and legacy of anti-apartheid revolutionary and Pan-Africanist Robert Sobukwe. Clips from that episode are available on our YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our Patreon along with all the episodes from our archive.

A special type of political personality

Photo by Ayoola Salako on Unsplash

Photo by Ayoola Salako on Unsplash Nigerians old and young received the news of the death of Lateef Kay���de Jakande on Thursday February 11, 2021 with a near-universal outpouring of positive grief. At just six months shy of his 92nd birthday, the first civilian governor of Lagos State lived to a graceful old age.

With the death three months earlier of Abdulkadir Balarabe Musa, his counterpart in the old Kaduna State, Jakande���s demise marked the passing of the era of a special type of political personality. The truly progressive office-holder, well-spoken and well-informed, invested in politics as public service, heroically championing social democracy without losing sight of personal probity.

The impulse that motivated his generation of politicians found an outlet in public service only as a re-dedication to the social experiment that an earlier generation of African political figures, the likes of Kwame Nkrumah, Ahmed Ben Bella, Oginga Odinga, and Mamadou Dia had failed to pull off. The dark patch in his career���serving as a minister under military dictator General Sani Abacha (1993-1998)���was the kind of choice a politician would make. The tragedy was that Jakande took that decision at a time he���d attained the rank of a statesman.

Born in ���p���t���do, on Lagos Island, on July 23, 1929, Jakande was a preternatural intellectual, and he chose journalism as his primary vocation. Coming of age in the 1950s, he entered the anti-colonial fray as a reporter with the Daily Service. In a few years, he caught the attention of ���baf���mi Awol���w���, the rising central political figure in Western Nigeria and leader of the Action Group (AG), a political party with perhaps the most forward-looking understanding of social democracy.

In 1953, the year after Awol���w��� became premier of the region, Jakande joined The Nigerian Tribune, the newspaper Awol���w��� had established four years prior. He rose quickly to become the editor-in-chief and stayed on the masthead through the 1960s. In an age when nationalist enthusiasm blurred the lines between professionalism and political gamesmanship, Jakande���s writings, under the pen-name John West, stood out for their forthrightness. It was a trait that stuck to him throughout his life, in public and private.

It was the fashion of the time, too, that the forthright journalist wrote with an eye on political career. Through his association with Awol���w���, Jakande became a suspect in the treasonable felony trials of 1963, and was sentenced to a term of imprisonment. While serving time, he narrowed his focus to a problem close to his heart: the status of Lagos as a metropolitan city. Lagos was often a bargaining chip in the struggle for power among the country���s political elites. Culturally and geographically of the Western region, it also functioned as the federal capital, and it seemed politically expedient to maintain its neutral place in the interest of national cohesion. Parts of the mainland fell under the regional government, but the island, the traditional Lagos, also known as the Crown Colony, had elected representatives who lacked the legal powers of accountability.

Jakande wrote to question the city���s nebulous status. ���The Minister for Lagos Affairs, who has never been a Lagosian,��� he noted in the pamphlet The Case for a Lagos State, ���is for all practical purposes the ruler of Lagos. This means that Lagos is being governed by one who is not responsible to the people, who does not understand them, and who is unknown to the Lagos electorate, while the elected representatives of the people in the City Council are rendered impotent to fulfill their election pledges.”

This was in 1964.

Two years later, the military government of Col. Yakubu Gowon came to power as a result of a counter-coup of July that year, and set about averting the looming political crisis. Jakande and other prisoners were freed, and he promptly published his pamphlet. As fate would have it, that dream became a reality the following year, although Jakande got to rule it only 12 years later. (State creation did not resolve the crisis. Within weeks of the birth of Lagos state, the country commenced a war with secessionist Biafra.)

Running on the platform of the Unity Party of Nigeria, the Second Republic party formed by Awol���w���, his old political associate, Jakande was popularly elected the first civilian governor of Lagos and took office in October 1979.�� His tenure marked the beginning of unprecedented social programs in the state, executing his party���s famous ���four cardinal programs��� beyond the call of duty. Setting up low-cost housing schemes, new school buildings to accommodate the brimming-over student population, and the ambitious Metro Plan earned Jakande the moniker ���Action Governor.��� The durability of those school buildings worried many, other than his political detractors; those who approved of his commitment to social equality did not stint on criticisms of his doing things on the cheap.

Lagos being the seat of the federal government, all eyes were on the governor, and Jakande rose to the challenge. Political aspirants of all kinds often held him up as the only exemplary governor. He had a successful first term, and his re-election was a resounding success.

A politician must politick. Determined to stay relevant, and in a calculated attempt to checkmate some of his rivals in the Awol���w��� camp, Jakande agreed to serve as the minister for works and housing under Abacha. It could have been just another job, except that most people did not expect Jakande to be just another jobber. He never regained the shine of his ���Action��� years.

His personal style was simple. Usually dressed in sharp-cut lace bu��ba�� and pants, with the trademark golden cap of embroidered wool, he carried a flywhisk. For many years, even after leaving office, he owned only an old Toyota, according to Lai Olurode, his biographer. He lived in a house he built for himself at Ilupeju, in central Lagos, having sold an older house from his journalism days, unwilling to own two houses. A workaholic, he was reportedly at his office poring over files when news of the military coup that ousted him and others broke on December 31, 1983.

His achievements in office loomed large, still. In fact, his real disposition was an intellectual���s; seriously populist. It is more accurate to put him in the company of committed social reformers like the educationist Tai ���olarin and Aminu Kano (of the People’s Redemption Party) than with his party allies like B���la Ige.

It is the passage of that age of high idealism that Nigerians mourned in the outpouring of grief that followed his death.

February 21, 2021

Upsetting color and its representations

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia.

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. This post is part of a series of interviews with African artists from across the diaspora.

The Colombia-born photographer Juan Orrantia has lived in Johannesburg, South Africa for the past 12 years. His practice and career as a photographer have gone through many iterations. He was fully aware of South Africa���s history of documentary photography and complicated history with apartheid before relocating there. However, he never could have expected the uncertainty and self-doubt that would grip his practice after arriving, and lead him to not take pictures. Traveling to central and southern Mozambique offered him an opportunity to further develop his photographic interests in the affective qualities of landscapes. It would take him several years before he published the handmade diary-like photobook titled There was heat that smelled of bread and dead fish, an exploration of sites of anti-colonial struggle and civil war in Mozambique, and the varied ways in which inhabitants of these landscapes continually live within these histories of war and displacement.

While completing this project, Orrantia taught at the Wits School of Arts and pursed an MFA in Photography at the Hartford Art School. Since then, he has dedicated himself full-time to photography and distanced himself in a formal and conceptual sense from his doctoral training as a visual anthropologist. Like Stains of Red Dirt, the title of his latest photobook project and recipient of 2019 Fiebre Dummy Award, takes its name from the color of dirt in South Africa and is a metaphor for how the place of South Africa has literally stained him and his photographic practice. In the featured body of work, Orrantia photographs life from inside his family���s Johannesburg apartment, positioning intimate scenes of cohabitation at the center of questions about what it means to see history photographically and in color. Africa Is a Country contributor Drew Thompson spoke with Orrantia regarding his longstanding interest in making photobooks, and what it means to think about photography a place like South Africa.

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson You are a photographer who invests in photobooks and the making of photobooks specifically. For you, are photobooks an important mode for exhibiting and engaging with photographs?

Juan OrrantiaThe way I transitioned into still photography years ago was through the idea of the essay film. I was interested in the essay film as a form and concept, but not in making films. My first approach was to make still photographs, and I would mix them with audio and soundtracks that I recorded. Taking the elements of an essay film, breaking them apart, and putting them together in some way, I discovered as an approach to photobooks, or [at the very least] a way of thinking about them. The photobook, from the way I see, is an interesting space or form where you can ask questions. I like non-linearity. At the beginning I would add text, and it would support all of these other elements in the form of a book but without the restrictions of a film. The book has certain freedoms that the film does not have. Also, I was never a darkroom photographer. I was not the one who was there [in the darkroom] for hours making photographs, even though it was a way of connecting with the materiality of the photograph. So, when I started to make books, I felt that I was making something instead of taking photographs or making photographs for a screen.

Drew ThompsonIn Southern Africa there is a rich history of photobooks. Can you elaborate on the types of choices you confront when editing your photographs in a photobook context?

Juan OrrantiaOne of the things I like about photobooks is that the meaning of photographs can change completely. There are a lot of possibilities. If you want to tell a super linear kind of traditional story, you can do it. If you want to completely mess it up and do something very random, where each image is questioned by the next one, or by the one next to it, or by the one on top of it, or by a paper that suddenly shows up in the middle of the signature. Those are the possibilities I like. Because of the way I have been working as of late, I am interested in questioning that initial idea of an image, what we see in an image. I know that someone who works in exhibition style or installation will say you can do that in an exhibition. But, for me, there is a personal choice, [and] I feel like I can do a lot of that with the book. At the beginning I thought it was because I could add text to it, and the text, like in an essay film, would be something very different from the image. [The text] would not be related, creating a new meaning by association or montage. However, the whole effect is to put them together, or cross them, or read them in some way. Now, I have gone to try and take the text out and see what those possibilities are with the images themselves and with the elements of the book itself, adding a particular paper or cover in a certain way, or even the threads that can allow me to disrupt the meanings of the images as you go back and forth. The book is something that helps me explore what I am trying to work out photographically.

Drew ThompsonIn (your recent book), Like Stains of Red Dirt, you speak of how your work explores the outside world from interior spaces. How has the pandemic forced you to rethink this dichotomy of inside and outside?

Juan OrrantiaWhen the pandemic started, I was like ���The book is going to come out now and it is totally going to look like a pandemic book.��� Pre-pandemic I was already discovering the pleasures of making things at home and creating my own photographs within my own enclosed space and with the elements I had available in my immediate space. So, it was both a way of playing with a different way of making my photographs, but also of using the elements within my own environment to make those photographs as well. Photographing inside was a way of approaching the way I could bring myself closer to the work that I was producing. That project basically taught me to take the pressure off from trying to ���find��� what I was looking for ���outside.��� It forced me to think from within, both conceptually and materially.

Drew ThompsonAs you were taking these photographs what kinds of choices were you facing? There are no images of inside your house looking to the outside world. Such a view is largely conveyed through the way you engage with light.

Juan OrrantiaInitially I tried to take a lot of photographs outside, thinking that it was going to be about ���South Africa.��� I photographed a lot and they really were not working. So, I started to think how the outside suddenly becomes part of the inside: metaphorically, historically, and to translate that photographically. I started to think about it through my daughter. A lot of that history [outside of my house] came in through her, literally to my life through her. That idea expanded into how this place has come into me, into forming a relationship, into my space in different ways. I was asking myself how do I look for, or how do I engage with, those traces from this place that I am inhabiting? I started to take seriously the light coming into the house, which is why I started to think about color much more.

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson Maybe this is a good place to shift to color. What is your relationship to color photography in the context of Southern Africa?

Juan OrrantiaMy initial approach to black-and-white was specific. I wanted to photograph in black-and-white because I wanted the possibilities of things that were more poetic, that could take the image that I was making into something less real. [Poetic for me] was something that would have more leeway with what we were seeing. A lot of the [new] documentary work that was coming out of South Africa was made in color. I wanted to photograph in much more of an ambivalent, ambiguous way. The grain, the tones of black-and-white, playing with blurriness would make things less defined. When I switched to color, I was really just exploring how to work with color. Fast forward a few years to when I get to do the work here in the flat, and I was really looking for the light, for those colors and their changes. I asked: What is color really doing for me? Then I started to think critically, conceptually, and metaphorically about color per se. So, that tied in one of my interests with the work, which has to do with the representation of the continent. In Binyavanga Wainaina���s piece ���How to Write About Africa,��� he talks about light. I wanted to use tropes prevalent in representations of the continent in order to upset them, [which was] when I started to upset the colors. But color was also a metaphor about race [and] how race is spoken about here in South Africa. People talk about color. Everything is described in the colors of racialized categories. Color was thus both a metaphor and reality. Then, this whole other world opened���of transforming or upsetting the images I was making through color manipulations.

Drew ThompsonI really like this word ���upset.��� How technically and conceptual did you find yourself upsetting color?

Juan OrrantiaIt was really using color to make an image that you know is very banal but that also tells you there is something not completely truthful, or right with it. There is something more to it in a way. Conceptually, for me, that was a way of talking about representation. For example, what is South Africa if you see an aloe plant completely in purples and pinks. Why is that not true? Why is it that pictures of the continent, say like those complicated ones made by Leni Riefenstahl, are believed to be more true? To me it was a way of opening up the question: What is one particular place when represented photographically? I am not photographing the light of Southern Africa; I don���t want to essentialize that. I upset the color. That meant literally putting these papers on the flash and changing the image that I was seeing. I would also get surprised by what I thought I was seeing. I wanted to have that element of surprise be part of my own process. Suddenly I am seeing the image I just composed but it is completely changed because it is all purple, or half of it is purple and half of it is green.

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson When we speak about upsetting color, the image that comes to mind is of the watermelon and cellophane paper. Your work challenges commonly held views on the everyday and the artificiality that we ascribe to the everyday through photography.

Juan OrrantiaArtificiality was something that was very important to me. Some of them [the photographs] are in natural light, and some of them are in artificial light. What happens when you mix the two? I think questioning what is artificial and what is not artificial ties a lot to the history of South Africa, where [there���s] an ambivalence about race. Something that [is] so natural becomes something artificial through the way [that] it is completely manipulated by history, laws, and regimes. Categories and identities are fluid, but we tend to read them as givens (natural or artificial) depending on where we stand, or how we look.

It also was related to my thinking back to those ideas from the film essay. For example, when they start to include the tripods in the frame to make the point that what you are producing is obviously a construction. It was important for me to reinforce that we live with constructed categories, and fluid, shifting meanings. That is why in some of the images I leave the pieces of the cellophane hanging out or they become part of the frame. And, in others, they become the photograph itself. In those I am photographing the artificiality itself; it becomes my subject by photographing the means that I am using to transform the color of the photographs themselves. That image of the watermelon, for me, points to how these ideas and practices are literally embedded in the banality of our everyday lives.

Drew ThompsonPaging through the Like Stains of Red Dirt, I get the sense that the photographs are particularly constructed images, and they are precisely what you want to show. You force us to engage with critical concepts of photography, like what is the documentary, what is seriality, or what is color?

Juan OrrantiaI���m trying to create images that can make us think what an image of something is. Is this really what Y or X place looks, or is supposed to look like? According to whom? Because that deals with questions in the first place which interest me, about how people and places have been defined. To me these are questions tied to notions of photographic truth and its limits. I want a fluid engagement with both real histories that produce very real effects for people���s lives, but also to remind us that things aren���t necessarily what we are told they are. When I was making the book, I was adamant about not having a linear narrative. Precisely the way I had made those images, they were moments and fragments. There was not one story I wanted to tell. I don���t want to ���capture��� any particular one story to tell in any particular way. I am exploring this relationship with all of these trajectories, undercurrents, and all of these come in different ways. For me, a relationship is basically moments tied together. What I have after 12 years living here is an accumulation of moments, feelings, etc. In its most basic way, that also is what photography is: a bunch of moments and fragments that suddenly transform into ���narratives��� and ���stories.��� I wanted to go to the fragmentary nature of it, to how (photographic) fragments get tied together by histories and choices. That is why I started and finished the book with a fragment of a Shirley card, because that���s also part of this representational reality.

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson

From Like Stains of Red Dirt by Juan Orrantia. Drew Thompson We can talk about the Shirley card in terms of racializing photography. In your project, there are elements of engaging and questioning race and it���s artificiality and how it reveals itself through color. How did the Shirley card emerge in your work and inform how you were seeing light? How did the Shirley card factor into your technical practice?

Juan OrrantiaTechnically, if anything, the Shirley card is tied to ideas of balancing and creating some sense of norm about ���natural��� color. The idea of a natural color is itself racialized and literally embedded in photographic technology. I wanted to deal with this problematic history through my own disruption of color [and] color correcting images. If I were a�����proper�����photographer I would have color corrected the images and have them in their�����true�����natural colors. That became a problem for me because that was not what I wanted to do. In a way, the Shirley card is part of that history. In the last couple of years, people have started to talk about the Shirley card much more. There is the Broomberg and Chanarin piece�����To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light��� or Daniel Blight���s book��The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization. There is also the approach by the filmmaker John Akomfrah about recognizing these inherent problems and what forms of agency they have produced. I am not discovering anything new; it [the Shirley card and its history] is something that I can rely on to make the point of color being manipulated historically, racialized, and contested. I think it is a good referent to this history that people are recognizing now about the problematic relationship between photography, particularly through color, to photography in Africa and representations of the African continent and also of the possibilities of fighting it from within. The Shirley card is a referent to this history [and] also tied to the way I was working. To wanting to question definitions or assumptions of ���normal��� in how we see or recognize places, histories, etc. At the beginning I color corrected a lot. In the end, I would color correct, then I would upset it, and then play with both in the making of the final image.

Drew ThompsonHow do you place Like Stains of Red Dirt in relation to your work, and what comes next?

Juan OrrantiaThis work really pushed me to work much more photographically and to think about how I can use the medium and its limits for questions I have about the medium and my relationship to it. When I talk about the medium, I mean photography���s relationship to colonialism, to the effects of European reason in how we see and are seen. On the one hand, the work was the hardest I made as I had to confront something that in a way I had avoided. I had to confront the if and how I was going to photograph here in South Africa. Twelve years had passed [since I arrived in South Africa] and I hadn���t really photographed here. After such time I think it is fair to ask whether you are going to photograph or not. It was hard to think through why and how I was going to do it because it also meant thinking about choices over the last 10 years of my life. That has expanded into rethinking other bodies of work that I have done and messing with them. I am basically working with color and thinking about what I want color to do in relation to questions of representation and history. That expanded my interest in color itself, color���s relationship to colonialism or masculinity, for example, which are basically questions tied to the medium I chose to work with.

February 19, 2021

The politics of blessings

Photo by John Price on Unsplash. Parts of this text are adapted from��

Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics

,��published by Zed Books.

Photo by John Price on Unsplash. Parts of this text are adapted from��

Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics

,��published by Zed Books. On a sunny morning in early January 2016, a motorboat was making its way through Lake Victoria to Bussi, a small island situated a few kilometers west of Entebbe. On board were two foreign visitors: Deputy Ambassador Nadav Peldman from the Israeli embassy in Kenya, and Jos van Westing, the Fundraising and Development manager of the Evangelical Zionist organization Christians for Israel International. The two were traveling to Bussi to attend a five-day ���repentance conference��� for officers of the Uganda People���s Defense Force (UPDF), organized by Christians for Israel���s Ugandan branch.

Christians for Israel���s office in Uganda was established in 2009 by Drake Kanaabo, a known evangelist from one of the most popular and oldest Pentecostal churches in Uganda, the Redeemed of the Lord Evangelistic Church. The organization���s offices are conveniently located in central Kampala, close to the Ugandan Parliament, and its members have been participating on a regular basis in ���prayer breakfasts��� in this institution and organizing various outreach events among Ugandan churches, government officials, and political elites. They also run pilgrimage tours to the Holy Land and host Israeli Independence Day celebrations.

The 2016 conference in Bussi was organized by Kanaabo in cooperation with several high-ranking UPDF officers. It brought together more than 150 Christian military men who gathered to pray and fast in order to repent, as members of the Ugandan military, for their country���s mistreatment of Israel during the period of Idi Amin���s rule. ���These people, when they knelt down to confess, all of them burst into tears,��� one volunteer of Christians for Israel later described the event, in which the officers pleaded with Peldman to forgive Uganda on behalf of the Jewish Nation. ���It was historical. And we believe God forgave us, forgave our military.���

There is a long history of Western Evangelical support of Zionism and Israel, particularly, since the 1970s, from Christian groups in the US. Over the past decade, such support has become an increasingly dominant force in Israel���s relationships with African leaders and peoples as well. The Evangelical theological justifications for support of Israel mean little to Jewish Israelis, and Israeli diplomats also often stress the importance of establishing Israel���s image in Africa as a modern, tech-savvy nation and not only as the ancient Holy Land many Africans know from the Bible. And yet the pro-Israel messages Evangelicals promote, their suspicion of Islam, their urge to express unconditional support of Israeli policies, and their expanding influence on public life in many parts of Africa render them invaluable allies of the Jewish state.

Support for Israel comes from various Christian movements in Africa, but the most dominant among them are the Pentecostal (or ���neo-charismatic���) churches that have emerged in West Africa since the 1980s and have gained immense popularity across the continent, influencing the doctrines and practices of other denominations as well. Supporting the spread of Evangelical Zionist theologies among these churches, however, are also a host of foreign groups. The Africa���Israel Initiative, a Norwegian organization that seeks to create ���a highway of blessings from Israel to Africa and from Africa to Israel,��� is one of them. Christians United for Israel (CUFI)���America���s largest Christian pro-Israel lobby���is another.

Although Christian Zionist theologies and practices vary widely, the fascination of different conservative Evangelical groups with the Jewish People and Israel is commonly grounded in their literal interpretation of the Bible. Most fundamentally, Christian Zionists reject what they call ���replacement theology,��� that is, the notion that the Jews have lost their significance as God���s chosen after rejecting the messiahship of Jesus and were ���replaced��� by the church. This interpretation of the New Testament has been propagated by Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant churches for centuries. But a close reading of the scriptures, many Evangelicals argue, indicates that it is false. God���s covenant with the people of Israel is still valid.

This conviction has several implications of political significance. One is that whoever ���blesses��� the Jewish people���and by implication, the modern state of Israel���is believed to be rewarded with divine blessings. This is based on God���s promise to Abraham in Genesis 12:3 to bless whoever blesses him and curse whoever curses him. Another implication of the rejection of ���replacement theology��� is that the Jews are understood to have a central role to play in bringing about the end times and the Millennial Kingdom. Evangelicals thus often view Israel���s wealth, military prowess, and developmental achievements as clear indications of blessings and righteousness, and its ongoing conflicts as the fulfilment of biblical prophesies.

There are good reasons, therefore, that African Pentecostal churches have found Christian Zionist theologies persuasive and appealing. The notion that pro-Israel activism can have positive consequences resonates strongly with the Pentecostal emphasis on healing, entrepreneurship, prosperity, and the favorable powers of the Holy Spirit. The rejection of mainstream ���replacement theology������portrayed as a misleading doctrine implanted in people���s minds by foreign missionary churches���similarly resonates with the born-again concern with biblical authenticity. For spiritual movements relentlessly preoccupied with the uncovering of falsities and the clearing of doubts, the state of Israel is increasingly becoming an undisputed index of divine truth and revelation.

These trends, of course, have not gone unnoticed in Jerusalem. ���We are interested in ties with any religious, ethnic and political group, and it doesn���t matter whether it is Muslim, Evangelical or Catholic or anything else,��� Gideon Behar, previously the head of the Africa Bureau at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, explained. ���But the fact that there are Evangelical communities that are becoming larger and stronger everywhere in Africa��� these communities naturally have a stronger connection with Israel, and a stronger urge to have links with us, and they are certainly a factor that is increasingly encouraging African countries to strengthen their ties with Israel.���

Consider, for example, Nigeria���the epicenter of Africa���s ���Pentecostal revolution.��� Members of Nigeria���s Pentecostal elite, such as Chris Oyakhilome, TB Joshua, and Enoch Adeboye��� celebrity preachers with a high-profile media presence, representing churches with branches across the world and influencing millions of believers���have visited the Holy Land in recent years. Some returned, multiple times, accompanied by hundreds of pilgrims, regularly sharing impressive footage from their trips on social media and their popular TV channels. Prophet TB Joshua, founder of the Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos, was recently named ���Tourism Goodwill Ambassador��� by the Israeli Minister of Tourism after holding a two-day mass prayer event in Nazareth.

Zionist rhetoric is prevalent in these circles, and hence the warm welcome from Israeli officials. ���The problems that we are seeing between the Jews and the rest of the world, is because they are the favorites of God,��� Nigerian mega-pastor Enoch Adeboye of the Redeemed Christian Church of God explained in 2011 while visiting Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. ���When you are special to God, then automatically the devil wouldn���t like you either.��� In line with the imperative to bless Israel, in his regular pilgrimage tours to Israel in recent years, Adeboye also donated several ambulances to the Israeli national emergency service and disaster recovery organizations.

Pentecostal elites like Adeboye, as Ebenezer Obadare shows, are powerful actors in the country���s political landscape. President Goodluck Jonathan (2010���2015), a Christian from the country���s south-east, ���wore his supposed Christian and Pentecostalist credentials on his sleeve��� and strategically courted the nation���s most influential Pentecostal pastors and tapped into their powerful public influence. Among other things, he repeatedly visited Israel on pilgrimage tours���once as vice-president in 2007 and then twice during his presidency���each time traveling with an entourage of high-profile officials and pastors. In 2014, months before the elections that he eventually lost, he visited Israel accompanied by Bishop David Oyedepo, the founder of one of Africa���s largest Pentecostal movements, Winners��� Chapel.

As part of Jonathan���s branding of himself as Nigeria���s Pentecostal president, pilgrimage tours doubled as friendly formal visits and relations with Israel improved. To Israel���s benefit, Nigeria was a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2014���2015. In December 2014, when the council voted on a resolution calling for Israel to withdraw from the Occupied Palestinian Territories within three years, Nigeria (with Rwanda) abstained, though reportedly only after a last-minute personal phone call from Netanyahu to Jonathan. The abstention surprised many observers and allowed the US to avoid using its veto power.

A similar manifestation of the politics of blessings can be identified in Ghana. Though an Israeli embassy was only opened in Accra in 2011, ties between Israeli businesses and Ghanaian Evangelicals had developed earlier. Since its re-establishment, the Israeli embassy openly supported the activities of the local branch of the Africa���Israel Initiative, hosted its leaders at the ambassador���s residency, participated in their religious conferences and in recent years even organized its own prayer events. A regular attendee of the Israeli embassy���s events is Archbishop Nicolas Duncan-Williams, the founder of the Christian Action Faith Ministries and one of the most influential religious figures in Africa.

As faith-based organizations increasingly extend their spiritual and material influence into spheres that are commonly perceived as ���secular������electoral politics, business, education, popular culture���their impact on Israel���s standing is multi-layered. ���Our main objective as an embassy of the State of Israel is to strengthen the ties between Israel and Ghana. And we do this on three levels: ��� government-to-government ��� business-to-business ��� and people-to-people,��� Shani Cooper-Zubida, Israel���s ambassador to Ghana, explained. ���These churches are integrated in all three fields.��� Not only do they influence the media, public opinion, and governments, but they are also important economic actors. Indeed, Archbishop Duncan-Williams is also the ���Patron��� of the Ghana���Israel Business Chamber, inaugurated in 2016.

Ghana, Nigeria, and Uganda are not the only examples of such dynamics. The more public life and politics take an explicitly Pentecostal tone, across Africa, the more frequent such engagements become. Under the leadership of Lazarus Chakwera, an Evangelical Christian and former pastor, Malawi recently announced its intention to open an embassy in Jerusalem. In March 2020, Democratic Republic of Congo President Felix Tshisekedi, addressing the pro-Israel lobby AIPAC and his ���Evangelical Christian brothers and sisters��� in Washington, promised to open an embassy to Israel with an economic section in Jerusalem as well. ���I want to build strong connections with Israel and an alliance in which my country will be a blessing for the nation of Israel, in accordance with the promise of the Almighty God,��� Tshisekedi explained, citing Genesis 12:3.

In South Africa, meanwhile, Israel and the local South African Zionist Federation (SAZF) have long partnered with a host of born-again groups as well as the older Zion Christian Church (ZCC) to counter the pro-Palestinian stance of political leaders and curb popular support for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. ���Help us push back this scourge and this obsession that has captured the ruling party,��� SAZF chair Ben Swartz passionately pleaded with the attendees of a 2018 pro-Israel conference organized in Johannesburg in cooperation with the Israeli Ministry of Strategic Affairs. ���For we do not wish to bring upon us the curse associated with these actions. We wish to bring upon South Africa the blessings that South Africa so rightfully deserves.���

It is important to see these discourses and dynamics within a broader context. From Ghana, through Nigeria, Zambia, Uganda, Kenya, and all the way to Ethiopia, the rise of born-again Christianity in recent decades has transformed not only Africa���s religious landscape but also its politics. The aesthetics, truth claims, and practices associated with this faith are altering the very nature of citizenship, statehood, political action, and public life in many parts of the continent. The embracing of Christian Zionist theologies and the impact of these theologies on Israel���s standing in Africa are only some of the secondary consequences of this process, but they testify well for the anxieties and hopes that underly it, the multiple transnational actors and forces that shape its course, and its potential implications.

Israel and its supporters around the world are clearly grateful for these developments. For now, the Evangelical politics of blessings help legitimize apartheid and further suppress calls for accountability, justice, and democratization in Israel-Palestine. But the rise of born-again Christianity is ultimately entangled in much wider epistemological crises and political trends, which might be acutely felt in Africa but are hardly limited to it. Critics who hope to meaningfully intervene in the conversation will need to appreciate, at the very least, not only the changing circumstances, but also the new ways of knowing, speaking, and acting that are commanded by the Spirit.

February 18, 2021

Telling Nigerian stories

Still from In Ibadan courtesy Taiwo Egunjobi.

Still from In Ibadan courtesy Taiwo Egunjobi. Lagos is Nollywood���s hub.�� However, every day, films continue to be shot across other Nigerian cities such as Asaba, Enugu, Ibadan, and Abuja. These films may fit outside mainstream Nollywood, that is, films shot in Lagos for theatrical release, but they are equally watched and are even more reflective of the lives of the better percentage of Nigerians than the cinema films that mostly romanticize wealth and luxury living. Nollywood is typically sub-categorized into other branches like Asaba Nollywood (films shot in the less bustling city of Asaba or other parts of southeastern Nigeria) and Yoruba Nollywood (the Yoruba-language film industry), known for the less ���artistic��� films that are still released straight-to-video (the method of film distribution that birthed the industry) and, recently, on YouTube.

The industry is, however, quite de-structured. Sporadically, independent filmmakers outside of these industry divides, with a keen attention to both the technicality and art of filmmaking, spring up to tell quintessential Nigerian stories. For��In Ibadan, first-time feature film director Taiwo Egunjobi disavows Nollywood���s penchant for crass comedies and maudlin dramas, offering instead a simple yet heartfelt story about love and forgiveness set in the ancient city of Ibadan.

Former Lovers, Ewa (Goodness Emmanuel) and Obafemi (Temilolu Fosudo), are reunited in their hometown of Ibadan, years after their breakup, which was partly a consequence of Ewa���s relocation to Lagos. They confront the issues that caused their separation and attempt closure. The story is inspired not just by the life of the director, but also other members of the cast and crew domiciled in Ibadan, who have had to juggle relationships and career opportunities between the ancient city and Lagos, the city of dreams.

Taiwo Egunjobi and I conversed about the making of In Ibadan and Nigerian cinema.

Dika OfomaIn Ibadan��isn���t your first film. For a few years now, you���ve been writing scripts for other directors and have made a couple of shorts. Many see short films as a journey into learning filmmaking and fully developing into a filmmaker. What convinced you that the time was right for you to make a feature?

Taiwo EgunjobiGreat question. I think it was a sudden realization that the Calvary wasn���t coming, I wasn’t going to be handed the kind of money I needed to make the kind of films I wanted to make. But more importantly, I felt making a feature film was the right step in my education as a filmmaker. You need to put out your art and keep honing it.

Taiwo Egunjobi, Dika Ofoma

Taiwo Egunjobi, Dika Ofoma It means then, that part of your hesitation was seeking perfection. Instead of continuing in that, you finally found courage to allow yourself to evolve.

Taiwo EgunjobiExactly. Every filmmaker begins at that mental point. You always start with a lot of dreams: you want to make the next classic, have a big cinema run, go to Cannes, and win all the Oscars. If you���re not really honest with yourself, that could just be a prison.

Dika OfomaSomething striking about��In Ibadan��is that you stayed true to your style. You still play with colors and with music like in your shorts. (You previously made an experimental film about music, Musomania). I���d like to hear about the thought process of creating the sequence of scenes where there���s a band just playing music, interspersed with flashbacks of our protagonists��� past love lives. It���s almost as though the music was a voice over narration replacement for those scenes.

Taiwo EgunjobiWell, I guess it���s how I was educated in film and the things that I���ve come to love in cinema. Music is a big part of film and I���ve always been inspired by great performances in films and how to employ them in telling the story. Especially the films of Tunde Kelani. So yes, we wanted the music��In Ibadan��to be a part of the story and not simply for the fun of it. And we were lucky to find amazing musicians.

Dika OfomaI was coming to Tunde Kelani. The film also employed a comic style that seems to have been inherited from him. He is one of your influences. Are there other influences, especially from Nigeria and the rest of Africa?

Taiwo EgunjobiInteresting. And that���s the funny thing about influences, I guess they creep into your work somehow.��I���ve been influenced by a lot of filmmakers. In Nigeria, Femi Odugbemi, and there���s Djibril Diop Mamb��ty, the legendary Senegalese filmmaker. But my influences extend beyond the continent���I’m big on Yasujuro Ozu and Yorgos Lanthimos. I just resonate deeply with a lot of what I���ve seen or read from these people.

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma These are all interesting filmmakers. Sticking to your style also means that you did not compromise for commerciality.��In Ibadan��is calm and quiet���a slow burn. The storytelling is nonlinear. Something else very unconventional about the film was the open-ended conclusion. One of your experimental short films, aptly titled Don���t be a Nollywood Stereotype, ridiculed certain Nollywood tropes. Were you trying to hold yourself to your word when making this film? How deliberate were you on working at not making the conventional Nollywood film?

Taiwo EgunjobiWell, it���s all about the story. A simple, honest tale set in Ibadan. I think the slow, contemplative style just felt right for the story, the world, and the resources we had to tell it. Yes, there are lots of languages a director can employ to tell a story, and yes, there are also directorial styles: commercial or art. To me, it���s a bit of both, staying true to the story and staying true to myself and also my language. And I think it just points to what everyone has been saying, Nigeria has a lot going right now in film, call it the new wave or neo-Nollywood; a lot of filmmakers are emerging and becoming a part of the global Nollywood experience.

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma I like this thought. Someone unfamiliar with your works might pin the choice of relatively unknown casts for the film on budget constraints. While this could be true, actors such as Temilolu Fosudo and Simisola Olatunji have featured recurringly in your films. How important was it for you to work with a familiar crew and cast to actualize your vision for the film? And when you were making the film, were you thinking cinema? How did you hope to sell the film and recoup investments?

Taiwo EgunjobiWow. Well, I just happen to know these actors from way back and we’ve grown together. They know and understand our process and how we like to work. It was a lot of fun on set. We were a family, and I will continue making stuff with them.��In Ibadan��required very honest performances and I was able to get that from them with no hassles.

Honestly, we didn’t think a lot about distribution, we didn’t even consider theatrical distribution. We took a leap of faith and we are learning a lot about the market. We all know what the cinema business so no use stressing there. We are quite pleased with being on AfrolandTV though.

Dika OfomaHow did you get it on AfrolandTV?

Taiwo EgunjobiMy friend Damola Layonu told me about the platform. I reached out and they got back in about a week. Pretty simple.

Dika OfomaThe three women who exist in your film, happen to be thorns in the life of the protagonist or have hurt him in some way. Two had sexually harassed him, even. There���s a way the world today seems to have cast women as the better of the sexes in terms of morality. In flipping the script, were you trying to make conversation?

Taiwo EgunjobiWell, we just told the story, in a lot of ways, inspired by events in my life, in Temi (Fosudo)���s life. I���m sure there are aspects that are interesting to discuss, but that didn���t play on my mind. I must say though, life happens to both men and women, mistakes happen all the time and we learn from them. Love needs a lot of sacrifice and forgiveness to work, from both men and women.

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma

Still from In Ibadan. Dika Ofoma In��In Ibadan, Ibadan is breathtakingly photographed. In a sense, Ibadan became one of the characters. The movie explored our protagonists’ relationship with the city���Ewa relives her memories in Ibadan and wishes she never left for Lagos. Lagos is the land of opportunities, hopes, and dreams for Nigerians. The consensus is that the better pastures, better jobs, and opportunities are there. Year in and year out, young Nigerians in their multitude leave their smaller cities and towns for Lagos, hence the overpopulation of the city. Aspiring filmmakers and actors are not exempt. Despite the difficulties of shooting in Lagos, it has remained Nollywood���s hub for years. Did you consciously attempt to make a case for Ibadan with the cinematography?

Taiwo EgunjobiGreat question. Ibadan has been perceived in a way and by extension, photographed in a way, with a lot of clich��s. So, like you said, Ibadan was a key character in this story. We wanted to do better, and really romanticize the city in a different way. You know the deal with the famed brown roofs, the amala, the gruff etiquette of the people, we didn���t want to fixate on that. But instead, find the beauty in the simple things.

Dika OfomaThere was this shot at the start of the film that juxtaposed the brown roof with the skyscrapers/tall buildings. And I thought that was brilliant.

Taiwo EgunjobiYeah. That���s Ibadan in transition. Old and new.

Dika OfomaAt the start of our interview, you acknowledged that part of your delay in making a feature film was seeking perfection. I am curious to know if there are parts of��In Ibadan��you think you could have done some things differently or even better.

Taiwo EgunjobiSure, there are aspects of the plot I felt we could have tightened and handled better, especially the third act. And I wasn���t too pleased with the quality of the sound at times, I felt we could have done better. But water under the bridge now. You can always get better.

February 17, 2021

The life and times of Trevor Madondo

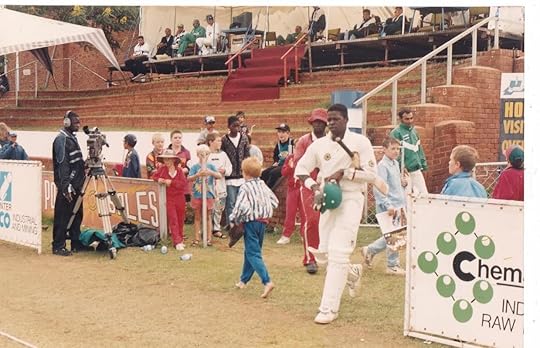

Trevor Madondo. Image credit Richard Harrison.

Trevor Madondo. Image credit Richard Harrison. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows.

��� Dambudzo Marechera, The House of HungerIn a sense I am the fiction I choose to be. At the same time, I am the ghoul or the harmless young man others take me for. I am what the rock dropping on my head makes me. I am my lungs breathing. My memory remembering. My desires reaching. My audience responding with an impatient sneer. I am all those things. Are they illusions? I do not know. And I think that is the point.

Zimbabwe was once famous for its schools. There���s a particularly prestigious boarding school in Esigodini, 55 kilometers southeast of Bulawayo near the old Bushtick Mine, called Falcon College. It was founded in 1954, and finds its motto in the work of the Roman poet Virgil: Sic itur ad astra, meaning literally ���thus one goes to the stars���, and more generally ���such is the way to immortality.���

In 1990, a student named Trevor Madondo arrived at Falcon College. During his time there he was to grow an unparalleled reputation as the next big thing in Zimbabwean cricket. In a strange way, Trevor���s short life, and his lasting impact, have come to embody the school���s maxim.

Or perhaps it���s not that strange at all. There���s an old game called sortes vergilianae. The gist is that it���s a sort of bibliomancy, or divination, by way of Virgil���s poems. Open any page of the Aeneid at random, pick a passage, and you���ll learn your fate. This was the method by which, legend has it, Hadrian���s ascent to the Roman emperorship was foretold, while King Charles 1 is said to have happened upon a passage that predicted his own execution by beheading. In the works of Dante, Virgil is the author���s guide to the underworld. In the medieval period, Virgil was thought of as a pagan prophet who had foretold the birth of Christ.

Needless to say, this arcane pastime has long fallen out of popularity. But Virgil still pops up in odd places. There is, for instance, a line from the Aeneid at the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York. And, of course, at Falcon College in Esigodini. But there is a bittersweet irony in these words as they relate to Trevor.

Bittersweet because he died before leaving much more than hints of what he may have been capable of achieving at the sport���s highest level. Ironic because the Aeneid was, to many, a celebration of imperial dominance and indigenous subjugation, while Trevor achieved a certain immortality in Zimbabwean cricketing lore precisely for the way in which he confronted cricket���s history as an instrument of empire.

Trevor is born in Mount Darwin, a small town 160 kilometers northeast of Harare, on November 22, 1976. It���s an area of both agricultural and mining interests not far from the border with Mozambique. Harare is still called Salisbury, and Mount Darwin is one of the epicenters of the battle for Zimbabwe���s liberation, being smack-bang in the middle of the northeastern operational area known as ���Hurricane.��� There is a major military base in the town, and it is here that the Rhodesians first implement ���Protected Villages��� and the ���Fire Force��� counter-insurgency strategy.

The war has been ongoing for over a decade and is deep into its second phase when Trevor comes into the world at the beginning of the rainy season. The doomed Geneva Conference (mediated by the British and involving both the Rhodesians and Black nationalists) is ongoing, compulsory military service has just been extended to 18 months, and none other than Henry Kissinger, his hour come round at last, slouches forth to involve himself in Rhodesia���s affairs. Kissinger attempts to engineer a post-Rhodesian government sympathetic to US interests but despite (or perhaps because of) his machinations the war only intensifies.

This is the fractious and uncertain milieu of Trevor���s birth. Holding their infant child, his parents can surely not imagine the career their son will choose, nor the mark it will leave on his country. In those circumstances, he had as much chance to walk on the moon as he had to represent, in cricket, that quintessentially English game, a nation that did not yet exist, but in the hearts and minds of revolutionaries.

Image credit Richard Harrison.

Image credit Richard Harrison. First years in the world. From crying toddler to smiling child. Born a Rhodesian, now a Zimbabwean. A younger brother, Tafadzwa, is born in a newly independent Zimbabwe in February 1981. Trevor is six years old when the family leaves Mount Darwin the following year. They move around the country for a while, following his father���s work as an Agritex Officer. Zimbabwe���s renowned agricultural extension service is probably the best in Africa at the time, with skilled extension workers and agronomists such as Madondo Sr. working throughout the countryside, offering expert training and advice.

When the growing Madondo family do eventually settle down again, it is in Mutare, a city nestled in a nook within the undulating mountains of the Eastern Highlands. Yet Trevor remains unsettled, even at this young age. He is sent to boarding school at Lilfordia, 20 kilometers west of Harare. It is here that he finds the sport that will change his life.

Lilfordia is a beautiful farm school with an odd history. Agnes and Atherton Lilford open the school in 1909 as a way of easing their financial troubles. Leaving those early money worries well behind, their son Douglas ���Boss��� Lilford goes on to become something of a financial tycoon, with mining, farming, and industrial concerns. He plays a key role in the formation of the Rhodesian Front in the 1960s, helping to mastermind the Unilateral Declaration of Independence, Rhodesia���s first attempt at thwarting majority rule, in 1965.

���Boss��� Lilford is murdered in what appears to be a robbery at his Doornfontein farm in 1985, at around the same time Trevor is first enrolled at Lilfordia. (Ian Smith calls Lilford ���my closest and greatest friend��� upon hearing of his death). One can only speculate as to what Lilford made of the increasingly progressive and multi-racial character of the school, but as Lilfordia���s own online history notes: ���With the coming of Independence the pendulum swung spectacularly.���

The school is by this stage run by Iain and Letitia Campbell, Iain being particularly keen on cricket in addition to his duties as headmaster. Indeed, the Campbell family are something akin to royalty in Zimbabwean cricketing circles, with Iain���s son Alistair going on to captain the country in the late 1990s, and Lilfordia���s alumni includes several national cricketers. Iain takes one look at the young Trevor Madondo and knows a cricketer when he sees one.

���Trevor grew up under the guidance of one of the most brilliant cricketing brains in this country,��� explains veteran Zimbabwean journalist Enock Muchinjo. ���One of the most humble, but knowledgeable, cricket minds. Iain was mesmerized by Trevor. He took him under his wing.���

Iain Campbell passes away in 2008, shortly before Lilfordia���s centenary, but his son Alistair is still involved in the running of the school, and in cricket in Zimbabwe. ���I remember him well,��� Alistair says of Trevor. ���My first memories of him are of my old man saying ���you���ve just gotta look at this guy, we���ve got this guy who���s really good, come and have a look at him bat���.���

���He really did have something special. And not only in cricket, just sports in general. Anything he turned his hand to, whether it be cricket, athletics, rugby, hockey. At junior school he was an absolute standout. A prodigy. You���d say this guy is destined for greater glory.���

The glories are not long in coming. Trevor is inducted into the school���s cricket set-up when he is in Grade 3 and by the time he is in Grade 5 he is already playing in the school���s first team with children a year or two older than him. He opens the bowling and bats at No. 4��� the prime batting slot in any team. In Grade 6 he is selected for the Partridges, the national primary schools cricket team, and in 1989 he is part of the Mashonaland Country Districts primary schools select team that tours England. In Grade 7 he averages an incredible 84.00 with the bat, scoring five centuries including 108 against Rydings School. A destiny in cricket seems already to be calling him, and his parents��� choice of high school is tailormade to fulfill it: Falcon College has produced two national Test captains, and numerous Test cricketers. Word soon begins to spread of his talent, and by the time Trevor gets to Falcon College in 1990, though he is over-age and distinctly under-sized, his star is well on the rise.

It is not uncommon, in the 1980s and 1990s, to find foreign teachers in Zimbabwean schools. Indeed, there is something of an influx of young teaching professionals into the country at this time, partly as a result of the government���s commitment to expanding access to education across the country. Zimbabwe���s education system is much lauded, and many Zimbabweans still boast of the country���s extraordinarily high literacy rates���though such a brag is at best only a half truth these days. Many of the expat teachers will flee Zimbabwe���s economic and sociopolitical woes in the 2000s, but a handful stick around, and one such example is Richard Harrison. He arrives at Falcon College fresh from Durham University in September 1986, thinking he is coming for a couple of years, and never leaves. And from that day to this, he���s coached cricket at Falcon too.

���I can remember the very first practice session Trevor came to,��� he says. ���I���d heard all about this hot-shot cricketer who was going to join and transform my team. And then this tiny little fellow appeared on the field the first day. I thought: really? But as it turned out, he did know exactly what to do.���

It is not only at Falcon College that Trevor���s cricketing prowess begins to precede him. Word is also spreading in his hometown of Mutare. Baynham Goredema is a Mutare-born graphic designer, creative, and social commentator. He is also a keen follower of Zimbabwean cricket, and was a handy player in his youth. ���When I was in Grade 6 I was chosen amongst players from our school to play in the Casuals Cricket Festival held every year at Mutare Sports Club where boys from around the country were selected and placed into four different teams,��� Goredema explains.

���Before the cricket started, there was already a buzz around the ground, whispers of ���Trevor Madondo is here���. So I wanted to see this guy. I eventually saw him when he went out to bat. They would call out the incoming batsmen on the PA. He definitely was special as he was hitting all the bowlers around the park. And he had a captive audience. It seemed all the older guys knew who he was. That day when he was walking around you could see that he commanded a lot of respect. He seemed like a quiet person.���

Trevor breathes rarified air into the small Mutare sporting scene as a young, black batsman. This is the fourth-largest city in Zimbabwe, with a population of around 150,000 in the 1990s. The sporting community is small but passionate, and cricket is at this time run largely by whites.

���Word just spread around the city that there was this prodigious talent who was going to be the greatest ever to come from Zimbabwe,��� says Muchinjo, who is also from Mutare. ���He���d come back on school holidays and play for the local club, Mutare Sports Club. Some of my earliest memories are of going to watch Trevor bat. I���d walk from our family home, a distance of about five or six kilometers, just to see him practice with the seniors. Quite a few of the senior players in the white community also really took to him. Every time he came back home during the holidays, they would immediately, even when he was as young as 15 or 16, draft him into the first team.

���What was also amazing was the foresightedness of people like Mark Burmester, who was the captain of Mutare Sports Club. He took Trevor through the paces, guided him. I think he saw that for cricket in Zimbabwe to have a future, it needed to grow. It needed to change. And people like Trevor represented that future.���

Cricket is an aesthetic game, and one obsessed with numbers and technique. Other games have rules. Cricket has laws. It is recognized that there is a certain ���correct��� way to play, yet no two cricketers are exactly alike. Each plays the game in their own way. As a teenager, this is Trevor���s way: to see the technical nuances others can���t. To play the shots others won���t. To take on the biggest and baddest among the opposition. It���s a style that leads to moments of brilliance and frustration in equal measure.

Amid formative years and teenage frivolity, Trevor starts to find his way. He makes friends. Brighton Watambwa, who had also been at Lilfordia and will also play Test cricket for Zimbabwe, is one. Qhubekani ���Q��� Nkala is another. ���Trevor was one of the most talented cricketers I met and played with,��� says Nkala. ���If we were playing a team and everyone was scared of a fast bowler, Trevor would be like: ���no, that���s the one I want���. And he���d try and hook him. Or pull him. Because he was that confident. And, technically, I don���t know any schoolboy who was his equal.���

Trevor and Qhubekani on the field, on some hazy afternoon in the long ago. An opposition batsman bullying their team. Trevor with his arm around Q���s shoulder, a word in his ear: ���He would look at a batsman and say Q we can work this guy out like this,��� Nkala says. ���Drop your mid on. Look at how this guy holds his bat. How he stands. This guy is bottom-handed, so put someone at midwicket, toss it up outside off stump, he���s going to try drag it across. That���s how we get him. He had such a wealth of knowledge about the game at such a young age.���

He is a natural. Cricket comes easily. Too easily? He begins to display some of that impatience particular to those endowed with exceptional talent. A sort of boredom at being that much better than everyone else. His coach is frustrated by Trevor finding ways to get himself out even if the bowlers can���t. He wants more runs from the young batsman. He knows he���s good enough.

Yet he is not arrogant, and he doesn���t like arrogance in others. ���If there was someone walking around all cock-a-hoop and big boots, Trevor would be like, ���ja today I���m going to take this guy to the cleaners and put him in his place on the field���,��� says Nkala. ���On the cricket field, he���d naturally come into his own, simply because he was so good. But he didn���t talk it up. It was in the way he played his cricket.���

But now also a stubborn streak, a strong will, begins to show itself. Trevor does not fit neatly into the strict hierarchies of a traditional boarding school. He talks back. He goes his own way.

���The coach would be like, ���you know Trev, as an opening batsman you can���t try and hit the opening bowler back over his head���,��� says Nkala. ���But Trev would want to do that. Because, I think, he was confident in his own ability, and he never liked to be dominated on the cricket field. He did have quite a strong, stubborn streak. It���s a thread that you���d pick up if you were close to him.���

Harrison, his coach, goes further: ���He irritated me, and I suspect that I irritated him, and Trevor was never one to hide his views if he didn���t particularly like someone.��� But they will work it out in the end. In 1992 Trevor is selected for the Fawns���the national Under-15 age-group team���that tours Namibia. Though their relationship is still prickly, Harrison helps him to organize everything he needs for the trip. ���After that I seem to have finally convinced him of something. We didn���t look back. He was a schoolboy who became a friend.���

Image credit Richard Harrison.

Image credit Richard Harrison. It is 1995. Trevor is 18, has grown several feet, and added kilograms of muscle. He is still at school when, in April of that year, he is picked to play for Matabeleland, a senior provincial team, against a touring Glamorgan county side���his First Class debut. Molded into a wicketkeeper via Harrison���s attentions, he marches out in floppy hat and flannels to bat at no. 9 in Matabeleland���s innings, and promptly cracks 48 against a team that includes two bowlers to have played Test cricket for England. He adds 36 more in the second innings, along with three catches in the match, and Matabeleland win by 159 runs.

The following year he enrolls at Rhodes University in South Africa to study for a Bachelor of Commerce degree, entering straight into the university���s 1st XI. He plays regularly for the Zimbabwe Board XI in the UCBSA Bowl, a competition administered by South Africa���s national cricket board, scoring 86 against Transvaal B, 77 against a visiting Durham University side, and generally earning himself a reputation as a confident player of fast bowling.

But another sort of reputation also starts to build. One night he falls drunkenly from the third floor of his halls of residence, saved from serious injury only by luck. He lands in a bush that breaks his fall. After less than two years, he drops out of university and returns home to Zimbabwe to concentrate on his cricket.

He���s still scoring runs, but now it is his after-hours behavior, rather than his batting skills, that people are talking about. The occasion of his 21st birthday falls the day before a Zimbabwe Board XI game against Northern Transvaal.

���We went out and hit it really, really hard the night before that game,��� admits Darlington Matambanadzo, Trevor���s friend and club team-mate at Universals CC. ���I think we got back into the hotel at around five in the morning. And then transport comes to pick him up at about six-thirty. And then the whole time he���s like, man, if we have to bat first, I���m in so much shit.���

Moments later, the Board XI captain wins the toss and���of course���decides to bat. Far from being incapacitated, Trevor takes on the opposition fast bowlers and races to 98 not out, scoring almost half of the entire team���s total as wickets tumble at the other end and the Board XI is skittled for just over 200.

���Honestly, if they had bowled straight and full at him, they would have knocked him over,��� says Matambanadzo. ���But they were bowling in the channel outside off, and that gave him half an hour to shake off the cobwebs. And that was a top class attack. They had Chris van Noordwyk, who was quick. Another guy called Rudi Bryson, who was quick. And then there was Andre van Troost, who played for the Netherlands. And during the Dutch off-season he���d play a lot of provincial cricket in South Africa. So they had three really good quick bowlers.

You hear the word ���talent��� thrown around so much when you play any kind of sport, but that was the first time in my life that I really understood what talent is. Because there was no way in hell that he should have made those runs. And it���s great that he made those runs, but at the same time ��� you know, people don���t remember that kind of thing. They remember the other times when you don���t make a score and you���d been out all night. And once you get a reputation like that, it can actually end up stalling your career. He didn���t know how to manage it. There was a level at which he was responsible for those outcomes. And everybody drank. We were young. Earning a bit of money playing cricket. I don���t want to make it sound like Trevor used to drink alone. Because he didn���t. I was there. A lot of people were there. But he just couldn���t manage those perceptions correctly.���

Matambanadzo believes���as does Campbell, as does Muchinjo, Nkala, Burmester and anyone else you might speak to���that a lot of his troubles could have been avoided if there was a support structure around Trevor. If he had a mentor. But there are all sorts of factors working against him. Zimbabwean cricket is still in the first throes of professionalism, and such structures simply do not yet exist. Campbell also speaks about the lack of openness around personal mental health struggles among Zimbabwean athletes at the time.

���We just didn���t have that in our day. It was ���suck it up and get on with it.��� If you had a problem, and you delved into the bottle to deal with the problem, it was considered normal. It was just one of those things. Everyone���s got their own crosses to bear. Their own issues. And you don���t really want to get involved in other people���s issues. And then that person doesn���t really have anyone to turn to. It became a very dark space for some guys.���

Trevor also isn���t one to go and ask for help. Campbell does once try to talk to him about the need to focus, the need to slow down off the field. But he doesn���t press the issue. ���Having known his family for so long, that is something I regret,��� he says. ���Maybe I should have stepped up a bit more. Someone should have stepped up.���

A mentorship vacuum is something that many of that first generation of black Zimbabwean cricketers struggle with. The first black cricketer to be picked for Zimbabwe is Henry Olonga, in 1996. Players like Henry, and Trevor, are very much pioneers in a sport that is changing rapidly.

���A lot of the black kids had to figure it out for themselves, so they made mistakes that they didn���t have to,��� says Matambanadzo. ���I did it as well. We were immature. Trevor was immature. A lot of it I place at his own feet. He made a lot of mistakes. It was just dumb, young stuff. But if you have people you can trust who can tell you this is dumb, young stuff and you shouldn���t be doing this as regularly as you���re doing it, that might have made a difference.���

Despite the off-field distractions, Trevor���s batting performances are impossible to ignore and soon there is talk of a national call-up. One day, a few months before his debut for the national team, Trevor bumps into an old friend in downtown Harare. It is Qhubekani Nkala. The two have not seen each other since high school. But what should have been a happy reunion is now a sad memory for Nkala.

���I���ll tell you the saddest story for me,��� he says. ���It was probably about two or three months before he made his debut. I was walking downtown, and I see this black guy, slightly above average height, but muscled, hey. Muscled. And I���m like ���wow, look at that guy. He���s got muscles���. And this guy was carrying a bottle wrapped in brown paper. Not exactly the best way of concealing alcohol, right. Anyway, I walk past and then turn around and I���m like, ���Trevor, that���s you?���

���I���m not sure why he started having these problems. But I did speak to him, and the honest truth, I think, is that at the time, for a young black aspiring player, it was tough. It was hard to break in and be part of the inner circle. And I think Trevor just felt that pressure, and I think he never pulled himself towards himself, and probably didn���t have an appropriate role model. It was about three months after I met him that day in town, he debuted in a Test match against Pakistan.���

On the eve of his national debut, Trevor sits down with Zimbabwe���s coach, Dave Houghton. The coach is not convinced that Trevor is ready for the highest level. His reputation as a batsman who thrives under the challenge of facing down quick bowlers has brought him this far, but Pakistan���s bowling attack is unlike anything he���s experienced before. ���These guys know you���re on debut,��� Houghton says to Trevor, ���so whoever is bowling when you go in is going to try and knock your head off first to see if you���ve got any courage. Then when he sees that he���s going to try and break your toes.���

Pakistan is a mercurial team, and one that has always been known for its fearsome fast bowlers. They have in their XI Waqar Younis, perhaps the world���s best exponent of a toe-crushing, reverse-swinging bowling delivery called a yorker, and Shoaib Akhtar, almost certainly the fastest bowler to have ever played the game, clocking truly terrifying speeds in excess of 100mph.

Trevor receives his Test cap in a small ceremony on the edge of the field just before play starts on a late summer���s day in March 1998. The venue is Queens Sports Club in central Bulawayo, a majestic tree-lined throwback of a cricket ground. Trevor walks out to bat with the match in the balance: Zimbabwe five down with just 123 on the board. His heart thumps in his chest. His parents are watching. His high school coach Richard Harrison is watching. Having ducked and weaved past the inevitable bouncers, he is off the mark with a crunchy checked drive for three. He is hit on the toe by a Waqar yorker, but follows that up by punching a full toss straight back past the bowler to the sightscreen. Then he unfurls a fierce pull to smash offspinner Saqlain Mushtaq to the midwicket boundary, before bad light stops play.

���I take my hat off to him, because he batted about 45 minutes,��� says Houghton. ���He came into the changing room and I went in to try and talk to him, but he couldn���t speak. He chain-smoked about 10 cigarettes, one after the other, before he could get his words out.���

Trevor plays in the next game, in Harare, but he is run out without facing a ball in the first innings, and then grits his way through half an hour of obdurate batting before nicking off in the second. It will be two years before he can once again force his way into the Test side, this time in New Zealand.