Sean Jacobs's Blog

November 28, 2025

Trump’s beef with Nigeria

Presidents Trump and Buhari at the White House in 2018. Official White House photo credit Andrea Hanks via Flickr CC0.

Presidents Trump and Buhari at the White House in 2018. Official White House photo credit Andrea Hanks via Flickr CC0.The widely circulated article in Global Geopolitics, ���America���s Hypocrisy as Policy,��� offers a thoughtful reaction to US President Donald Trump���s insane but self-serving threat to invade Nigeria under the pretext of stopping a so-called Christian genocide. Trump tweeted on 31 October 31 and November 1st 2025 that ���Christianity is facing an existential threat in Nigeria,��� named Nigeria as ���a country of particular concern,��� and announced that the US was ���ready, willing and able to save our Great Christian population around the World.��� He also ordered the military to prepare to intervene in Nigeria and boasted that ���if we attack, it will be fast, vicious and sweet.���

Trump has often been described as a narcissist���someone who is deeply self-infatuated and impulsively seeks attention and adulation. Earlier this year, John MacArthur, the publisher of Harper���s magazine, writing in The Guardian, described him instead as a solipsist���a word he borrowed from the investigative psychiatrist Robert Lifton. A solipsist is someone who makes no attempt to court or please others, since the only point of reference is himself. Solipsists revel in making outrageous statements because they love being attacked to draw attention to themselves.

It is easy to dismiss Trump���s inflamed anti-Nigeria rhetoric as the rants of a narcissist or solipsist, since anyone who is familiar with Nigeria knows that the violence in that country affects both Christians and Muslims. ���He cannot be serious,��� some have argued. However, his insanity or wild outbursts may not be without material foundation. Trump often follows through on his rants if he does not face stiff resistance���especially when his anger is directed at groups, individuals or institutions he considers weak.

There are always interests and a method in his madness or egotistical rants. As the Global Geopolitics article notes, Nigeria is located within a resource-rich region that is important to the supply chains of US hi-tech companies and defense industries. That region stretches from Nigeria through Niger and Chad to Sudan and is endowed with vast amounts of rare earth minerals.

Apart from oil, Nigeria has enormous reserves of lithium, cobalt, nickel and other rare earths, which are embedded in solid rock and heavy mineral sands. It is ranked fifth globally in the production of rare earth elements���behind China, the US, Myanmar and Australia. Segun Adeyemi recently reported in Business Insider Africa that Chinese companies have invested more than USD 1.3 billion in Nigeria���s fast-growing lithium-processing industry. Combined with the leverage that Russia now wields in the mineral-rich Sahel states of Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali, China���s growing economic influence in West Africa���s regional power, Nigeria, should be of serious concern to the US, since China already dominates the global rare earths industry.

The US has been strategizing about how to end its high level of dependence on China for rare earths, which are essential for clean energy, such as electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines, and in electronic consumer products, such as LED television screens, computers and smart phones. These minerals are also required to produce jet engines, missile guidance and defense systems, satellites and GPS equipment.

After threatening China with a 140 per cent tariff when China imposed restrictions on the global supply of rare earths, Trump quickly made a U-turn in his recent meeting with China���s president, Xi. He realized that a trade war with China on rare earths would profoundly hurt the US economy. Under the deal he struck with Xi, Trump agreed to end the tariff threat and lift the ban on Chinese companies��� access to US chips, while Xi agreed to restart China���s supply of rare earths and purchase US soybeans for one year. Trump praised Xi as a great leader when he returned to the US.

The US is in panic mode in the geopolitics of rare earths trade. On his recent visit to Southeast Asia, Trump signed a raft of agreements with several countries in the region to beef up the production and processing of rare earths and exports to the US.

Various reports by experts in geopolitics indicate that the Trump administration sees Africa as an important source of critical minerals that will help wean the US off China. The administration brokered a peace deal between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda in June 2025, which included an investment agreement that allows the US to invest in DRC���s minerals.

Deals with other countries, such as Kenya, Tanzania, Angola, Malawi and Namibia are being discussed or supported. In 2022, the US and other Western countries launched a fourteen-member minerals security partnership (MSP) to boost the production and supply of critical minerals that will benefit member states. The MSP works with the multilateral financial institutions and export credit agencies to provide finance for specific projects. It holds forums with a number of countries that produce rare earths, including the DRC, Botswana and Zambia.

What does the US really want?The history of the US���s quest for foreign resources indicates that it uses multiple strategies, such as coercion, war, bribery and diplomacy, to achieve its goals. Coercion involves suspending aid or other economic benefits and political support to compel an adversary to bend to the will of the US.

When Trump suspended the US���s aid program and declared a trade war with the rest of the world in April 2025, several African and other leaders rushed to make deals with him. Global Witness revealed in July 2025, that seventeen countries (including six from Africa���i.e Angola, DRC, Liberia, Mozambique, Rwanda and Somalia) have hired Trump loyalists as lobbyists to help broker deals, ���with many bartering key resources including minerals in exchange for humanitarian or military support.���

The use of war to pursue US strategic and economic interests is well documented in the field of geopolitics and international political economy. During the Cold War, the US and other Western countries simply intervened in countries that threatened their vital interests without bothering to disguise their actions with lofty humanitarian objectives.

One of the most famous cases was the US invasion of Guatemala in 1954 to stop the land reform programme by Jacobo Arbenz Guzman���s leftist government that threatened the land holdings of the United Fruit Company���a US multinational with considerable power and interests in Central America. The brazen Anglo-French invasion of Egypt in 1956 when Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal is another well-known case.

Often, when US interests were threatened, rather than go to war US leaders relied on the CIA to work with local disaffected elements in the military to engineer a change of government or kill the incumbent president. The cases are overwhelming���such as the murder of Congo���s Patrice Lumumba in 1961 and Salvador Allende of Chile in 1973, and the overthrow of Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran in 1953. All these countries had huge mineral resources.

The rationale used by the US and its Western allies for invading countries changed when the Cold War ended in the 1990s and the US emerged as the sole superpower. The concept of humanitarian intervention gained ground within the United Nations system. This involved the US and other Western powers working through the UN to end wars and rebuild war-battered societies.

During that period, the US felt it did not face any existential threat, like communism, and could act as a moral force or policeman of the world while hiding its real interests. That posture rhymed with the values of the unipolar world: the spread of democracy, human rights and economic or market liberalism.

The US, however, faced strong resistance from most countries when it tried to use humanitarianism to overthrow governments it did not like without evidence to support its claims. Matters came to a head in 2003 over Iraq, which the US invaded under the humanitarian pretext of disarming it of weapons of mass destruction. It turned out that there were no such weapons. The US was simply after Iraq���s oil and helping to dismember a formidable foe of Israel.

As the Global Geopolitics article demonstrates, US interventions under the pretext of humanitarianism have always been catastrophic for those who live in the affected countries. After the old regime has been dislodged, the US often leaves the shattered countries to sort out the mess while it retains control of the resources that are the hidden but real reason for the interventions.

Understanding the violence in NigeriaNumerous reports and studies have shown that Nigeria���s violence affects Christians and Muslims. No group is insulated from it. I can think of six types of violence in the country. The first three are the Boko Haram, Islamist-inspired violence in the Northeast, whose main victims are Muslims who reject the group���s Islamist ideology; banditry in the Northwest, which affects Muslims and Christians in equal measure; and the ���herder-farmer��� conflict in the Middle Belt, which affects Christians and Muslims, although reports indicate that Christians are the main victims of that violence.

The other three types of violence are the ���herder-farmer��� violence in the Northwest, in which Fulani herders are reportedly pitched against Hausa farmers (both groups are Muslim); the violence inflicted by the Indigenous People of Biafra and bandits in the East against their own people, Igbos, who are Christian; and general banditry in large parts of the country, which has rendered traveling by road between cities risky.

The Nigerian state has been terribly negligent in its duty to protect the lives of Nigerians. And its poor record of economic management, corruption and poverty has driven many people to the edge. However, as can be seen from the above review, the state itself is not the key actor generating the violence. Non-state actors actively drive it.

If Christians and Muslims are equally affected by Nigeria���s multilayered violence, how did the narrative of Christian genocide emerge? A narrative of Christian genocide and Fulanisation has been developing among some groups in Nigeria who feel helpless as raw terror takes hold of their lives and communities, especially during the administration of Muhammadu Buhari, a Fulani, who was accused of being soft on Fulani herders when they committed wanton atrocities against other ethnic communities in the Middle Belt. That narrative feeds into Nigeria���s often toxic ethnic and religious discourse on domination and marginalisation. Lately, some of these groups have intensified their narrative to win support from powerful Western constituencies. These groups have mastered the techniques of misinformation through various social media outlets, networking and lobbying to insert their grievances into the politics of far-right movements in the US. Having a president like Trump who thrives on culture wars is seen as a boon.

White far-right groups in South Africa provided the road map. When, in February 2025, Trump accused the South African government of genocide against white farmers and condemned that country���s new land ownership law as racist, it was the post-apartheid discourse of white victimhood and lobbying activities of a right-wing Afrikaner pressure group, AfriForum, that got the Christian Right in the US, Republican policymakers and Trump to adopt the narrative of white genocide.

Some disaffected groups in Nigeria have copied from the playbook of AfriForum by drumming up the rhetoric of Christian genocide. Phillip van Niekerk reports in the Daily Maverick that diaspora ���Biafran separatists��� have ���repackaged��� their secessionist grievance as a struggle to save ���persecuted Christians������ and have been engaged in a lobbying campaign in Washington in partnership with Mercury Public Affairs, BW Global Group and Daniel Golden.

There is also a video circulating on WhatsApp, which shows a Catholic Bishop of Makurdi Diocese in Benue State in Nigeria, Wilfred Anagbe, addressing an audience in the US, in which he paints a dire picture of the fate of Nigerian Christians, alleging that Nigeria is being turned into an Islamic state and Christians are being wiped out. And in a letter signed by the president and vice president of the American Veterans of Igbo Descent to Trump, the organization declared that they ���are ready and willing to assist in any efforts aimed at the liberation and protection of Christians in Nigeria.���

These campaigns have resonated with American Christian nationalists, whose politics is driven by the notion of Christian civilisation under siege and the imperative of defending it. Hard-right politicians in the Republican Party, such as Ted Cruz, conservative political commentator, Bill Maher, Black corporate democrats and corporate journalists, such as New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Van Jones, and many others in Trump���s MAGA base, have jumped on the bandwagon. Cruz introduced a bill in the US Senate in September 2025 that designated Nigeria as a ���country of particular concern��� and imposed sanctions on Nigerian officials who are perceived as facilitating ������Islamist jihadist violence��� and blasphemy laws.

Does Trump have beef with Tinubu?Why didn���t Trump try to discuss his alleged grievances with Tinubu instead of threatening him with war? Where a vassal relationship exists between a great power and a weak state, recourse to war is never the first option in making demands. The great power can use various methods, including coercion, to get the vassal state to do its bidding. This is what Trump has done in Ukraine and the DRC. He has been able to gain access to the mineral wealth of those two countries without declaring war on them.

Recent developments suggest that relations between Trump and Tinubu may not be that cordial. Trump has been unable to get Tinubu and his government to support several of his pet projects in the foreign policy field. We could start with the Niger-ECOWAS conflict, which Trump inherited from Biden. Just after taking office in 2023, Tinubu gave the impression in the eyes of many that he had signed up to the project of policing the West African region on behalf of Western interests. As Chair of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), he issued an ultimatum to the military leader of Niger, General Abdourahamane Tchiani, who had staged a coup, to hand power back to the deposed leader, Mohammed Bazoum or face military intervention. Some of the most draconian sanctions in Africa were imposed on Niger, including cutting off the electricity supply and trade relations, and blocking financial transactions between ECOWAS and Niger.

It seemed that Tinubu, who had just won a highly disputed election and seemed unaware of Nigeria���s core strategic interests, was being egged on by Alassane Ouattara of C��te D���Ivoire and Macky Sall of Senegal���both regarded as client leaders of the French president, Emmanuel Macron���to reverse the coup in Niger by military force. France, supported by the EU and the US, was not willing to lose control of Niger���s rich deposits of uranium and its military base. The US was also worried about its drone base in the south of Niger, which served as part of its counterterrorism activities.

However, Tinubu faced significant opposition from Nigerians, especially Northern clerics, civil society activists and the National Assembly. He huffed and puffed but failed to pull the trigger. His abrupt climb down bolstered the confidence of the military leaders of Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali to withdraw from ECOWAS, which they described as a neocolonial instrument of Western powers; they formed an alternative organization���the Alliance of Sahel States.

The failure of ECOWAS under Tinubu to reverse Niger���s military coup may have convinced Trump that he could not be relied on to carry out the West���s agenda in West Africa, even though he continues to maintain cordial relations with Macron in France. The US may also have faced a rebuff from the Tinubu administration to relocate its Niger base to Nigeria when Niger���s military leader ordered the US to shut down its base in Niger. Civil society activists raised the alarm that there were active discussions between the US and the Tinubu administration to relocate the base to Nigeria. Growing opposition to the idea forced the US and Nigerian authorities to deny the allegations.

Two other areas of conflict are worth highlighting to underscore the strained relations between Trump and Tinubu. The first is Nigeria���s emphatic rejection of Trump���s request to accept Venezuelan deportees or third-party prisoners from the US. Adding insult to injury, Tinubu���s foreign minister, Yusuf Tuggar, evoked a famous remark from the US rap group Public Enemy in rejecting the request: ���In the words of the famous US rap group Public Enemy ��� You���ll remember a line from Flav Flav���a member of the group���who said: ���Flav Flav has problems of his own. I cannot do nothin��� for you man,���.��� This must have rankled Trump, especially as other African countries, such as Ghana, Rwanda, Eswatini, South Sudan and Uganda, had agreed to accept his deportees.

It is important to note that Trump has a dystopian view of Africa, which he described during his first term in office as a continent of ���shithole countries.��� John McDermott, Chief Africa correspondent at The Economist, highlighted comments made by Trump about Africa on Air Force One, which reveal his ���generally apocalyptic assumptions about Africa.��� As McDermott reported, Trump said, ���[In Africa] They have other countries, very bad also, you know that part of the world, very bad ������ With these kinds of views, Trump would not expect an African leader to turn down his request for help. Such a leader should be taught a lesson, he would imagine.

Then there is Nigeria���s decision to stick to its longstanding policy of supporting a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Tinubu���s foreign minister, Tuggar, has also been clear and forthright in condemning Israel���s genocidal carnage in Gaza. He described the violence as ���something every human being should stand up and oppose.��� Nigeria was part of 119 states that voted for immediate ceasefire in Gaza when the violence first erupted in 2023. It also voted, in 2024, against Israel���s occupation of Gaza.

So, what we have is a confluence of interests���local and foreign, and economic and ethnoreligious���as well as personal grievances and a warped view of Africa that have shaped Trump���s decision to threaten military action in Nigeria. However, no great power threatens war to save the souls of foreign people it despises or with whom it shares no strong bonds. History suggests that lurking behind every US intervention is the pursuit of economic and geopolitical interests.

I have tried to imagine what the US would do if it were to carry out its military threat. Would it bomb the Tinubu government out of existence, which would lead it to confront the real terror groups? Or would it ignore the Tinubu government and conduct a bombing campaign against the terrorists, who operate clandestinely in small groups? Either way, the US would be involved in a messy and costly guerrilla war that it will have no stomach to fight.

It is important to note that the US has never been successful in defeating terrorist groups in their own countries. It lacks the zeal, commitment and technique to sustain a long-drawn-out war. The US history of intervention to save humanity is littered with abject failures: Iraq, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia hold sobering lessons. However, the chaos of intervention may not prevent the US from trying to control Nigeria���s rich resources. Mining companies have a reputation of thriving in conflict zones by striking deals with local militias.

Tinubu has released a press statement in which he highlighted his government���s policy of engagement with Christian and Muslim leaders since 2023, to address security challenges that affect ���citizens across faiths and regions.��� He affirmed that Nigeria is not a religiously intolerant country and opposes ���religious persecution.��� He has followed this up with a twenty-four-page document on ���Nigeria and Religious Persecution: Deconstructing a Linear Narrative,��� prepared by the Office of the Minister of Foreign Affairs (2025), which challenges in substantial depth the narrative of a Christian genocide.

However, Tinubu���s conclusion in his press release that his ���administration is committed to working with the United States government and the international community to deepen understanding and cooperation on protection of communities of all faiths��� has raised eyebrows.

Could this be what Trump really wants to achieve with his military threat? Get the Tinubu administration to open talks with the US, which will then try to introduce the issue of rare earths and other economic and strategic issues in the negotiations, and force a deal?

November 27, 2025

Davido’s jacket

Davido in concert 2022. Image via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA-4.0.

Davido in concert 2022. Image via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA-4.0.If you listened to the crowd���s reaction as he made his way to the main stage at the Scorpio Kings and Friends Live concert at Loftus Stadium in South Africa���s capital, Pretoria, you���d be forgiven for mistaking the Nigerian Afrobeats star David Adedeji Adeleke (Davido) for a local. That���s because in a country where immigration discourse now turns on how carefully we tiptoe around ultranationalist anxieties���and where Afrophobia has become a social currency used to revive fading political careers���a 50,000-seat stadium doesn���t usually erupt in cheers for a Nigerian, no matter how famous. The violent history of being an African immigrant in post-apartheid South Africa certainly wouldn���t suggest such a welcome.

In the years of state failure and the disappointment that followed the country���s first democratic elections in 1994, nationalists have come to see African migrants���particularly Nigerians, navigating the chaos of South Africa���s urban inequality and deindustrialization���as the embodiment of all that���s gone wrong with the sociopolitical order. Culture has become the definitive battleground for this conflict, and as some of the most visible symbols of immigrant resilience, it was inevitable that Nigerian Afrobeats stars would become targets of South African ultranationalist ire. What really has nationalists in a knot is the suggestion that Amapiano owes its success in the West to the collaborative reach and popularity of Afrobeats artists. What began as a debate over class and regional roots (which part of South Africa gets credit for popularizing the genre) has since been overtaken by nationalism.

Yet, any sincere Amapiano fan will tell you that Adeleke, a Nigerian, has long been a North Star for the genre���one of its most consistent champions as it rises in global prominence. It made perfect sense, then, that what was dubbed ���Amapiano���s biggest concert��� would center on his appearance. He has embraced the genre sincerely, but unlike many of his Afrobeats contemporaries���who, on their path to Western success, often tested their sound in South African cities before reaching international resonance���there���s little to suggest that South Africa���s cultural scene was ever critical to Adeleke���s ascent. It���s only after hitting a creative ceiling in Afrobeats, following a string of underwhelming albums, that he began looking south to expand his sound.

Nationalists have tried to portray the ���Lagos-to-the-West via Johannesburg��� pipeline as some kind of foundational influence on West African Afrobeats. It���s true that Amapiano has left a lasting mark���some would even say it has become a vital organ of the West African sound. But Adeleke���s rise tells a different story: Afrobeats was already making headway in the West before Amapiano had even entered its infancy. In many ways, it is West African Afrobeats that has shaped the global reception of Amapiano, more than the other way around.

Scorpio Kings and Friends Live wasn���t Adeleke���s first major South African performance. He���d recently supported controversial US singer Chris Brown on the second leg of his South African tour in December last year. But Loftus was different. This time, Adeleke wasn���t a supporting act���he was central to the point the organizers were trying to make: Amapiano was now global enough to summon any star to its cause.

Part of the crisis besetting the genre since it began gaining traction in the West has been a lingering anxiety about its appeal and staying power. Can it command a following across the diaspora the way Afrobeats has? Can it stand on its own as an African sound with international authority? These questions haunt the genre���s rise. They also explain why Amapiano attracts nationalists so easily���people who have no qualms draping it in national colors, even as it stretches beyond South African borders.

That crisis is rooted in the genre���s cardinal ingredient: anarchy. Amapiano was born from the desire to rewrite the rules of South Africa���s exploitative music industry. And though it rarely offers a direct critique of the social conditions that shaped it, its stars have mastered the art of distilling the disappointments of democracy into sound. It���s the most disruptive cultural phenomenon since kwaito in the late 1990s. But as the genre goes global, growing calls for it to become more structured and professional have come to clash with the anarchic spirit at its core.

This contradiction shows up in everything from public frustration over artists missing shows or arriving late, to behind-the-scenes disarray around contracts and payments. The demand for coherence���reliability, branding, management���is in part a response to the polished success of Afrobeats. While Afrobeats stars sign lucrative deals with Western record labels and sell out stadiums abroad, Amapiano artists are still negotiating their way out of the genre���s domestic roots.

In that light, Adeleke���s appearance was more critical to the genre than many Amapiano fans might be willing to concede. His presence contradicted the creeping nationalism that now threatens to erode the genre���s anarchist ethos���and the progressive interior of its fan base. As Afrobeats has steadily claimed its place as the sound of the diaspora, Amapiano���s fans and pioneers have struggled to articulate a coherent critique of why it hasn���t matched that rise. Lacking clear answers, many have turned instead to populism and nationalism.

Nationalism may be useful as a geographical or archival marker���but it cannot explain Amapiano as a phenomenon, and it certainly can���t contain its cultural influence. What frustrates nationalists is Afrobeats��� indifference to the colonial boundaries they still hold dear. For them, the West African genre represents a dangerous idea: that immigration is an inevitable part of African life, not a crisis to be solved, but a flow to be embraced. The resentment about Afrobeats��� influence on Amapiano���and the attempts to rewrite the genre���s history through nationalist or regionalist frames���come from this discomfort. Amapiano refuses to tell the story that nationalists want to hear about post-apartheid South Africa.

They want the genre to reflect a socially coherent country, supported by a functional state. They want to plaster its success over the failures of neoliberal governance. But Amapiano insists otherwise. It is not the soundtrack of a triumphant nation���it is the exception that proves the rule. A byproduct of neglect and exploitation. A sound that exists despite the state, not because of it.

As Amapiano continues to leave its imprint on Afrobeats, nationalists have started treating it as an endangered national treasure���projecting the fantasies of the nation-state onto a genre. They see Afrobeats as a parasite threatening to absorb Amapiano whole. Because Afrobeats is more structurally advanced, they say, it will inevitably erase Amapiano���s local distinctiveness. But this isn���t a concern about artistic integrity or the exploitation of working-class musicians. It���s not even a critique of how neoliberalism commodifies and betrays cultural possibility. What nationalists fear is the loss of control over the genre���s narrative���especially if Amapiano is placed within a properly pan-African context.

And if it���s pan-Africanism they fear, then that future has already arrived���quietly, like a thief in the night. Amapiano is in the midst of an unambiguous pan-Africanist phase. Weekly collaborations between Afrobeats and Amapiano artists continue to defy nationalist arguments and deepen the genres��� mutual dependence. As I write this, Amapiano pioneer Themba Sekowe (DJ Maphorisa), Afrobeats icon Ayodeji Balogun (Wizkid), and Nigerian producer Michael Adeyinka (DJ Tunez) have just released ���Money Constant��� from the South Gidi EP���a collection of sounds that forcefully demonstrate the absurdity of trying to box a genre within the colonial fiction of the nation-state. On the track, South African and West African influences collide seamlessly.

Those who want to draw borders around Amapiano might accuse Sekowe and others of dragging the genre toward an abyss. But they would struggle to explain the 50,000-strong crowd at Loftus Stadium erupting as Adeleke, the living embodiment of the Afrobeats���Amapiano fusion, made his entrance. That moment may go down as the most important in the genre���s brief history. And the clearest evidence yet that Amapiano cannot be contained���by nation, region, or ideology.

Its significance had less to do with defying nationalism and more to do with what the genre makes possible. It was a celebration of what Afrophobic South Africans often vilify: Nigerian migrants carving out a life in Johannesburg. For nationalists, these migrants are not the promise of a society seeking justice beyond colonial borders. They are symptoms of a liberal state high on its own supply. They argue that South Africa, as the poster child of the post���Cold War liberal order, has paid a steep price for its commitment to human rights. But the irony is this: the very nation-state they claim is under threat is itself a product of that same liberal order they now despise.

The last time a Nigerian artist tried to sell out a South African stadium was in 2023, when Damini Ebunoluwa Ogulu (Burna Boy) was forced to cancel his scheduled FNB Stadium concert in Johannesburg. A lack of ticket sales and production issues were cited as reasons for the cancellation. But on social media, nationalists proudly claimed credit. They had actively campaigned for the concert to fail���as payback for Ogulu���s 2019 protest against Afrophobia in South Africa, where he went so far as to vow never to return until the issue was addressed.

It wasn���t na��ve for Ogulu to think he could sell out a 90,000-seater stadium. More than any other Afrobeats artist, he���s enjoyed consistent success in South Africa. He was topping local charts long before Amapiano or even Afrobeats had become global mainstream genres. In 2015, it was impossible to go anywhere in South Africa without hearing ���Soke��� from his breakout album On a Spaceship. His popularity wasn���t an anomaly. Zimbabwean folk legend Oliver ���Tuku��� Mtukudzi had found similar success in the late 1990s and early 2000s, especially after the resurgence of his song ���Neria,��� the soundtrack to Godwin Mawuru���s 1991 film of the same name. But Ogulu miscalculated the extent to which nationalism now shapes South Africa���s cultural scene���and how unforgiving it can be when an artist refuses to play along.

Adeleke���s South African experience has been notably different. His unambiguous embrace of Amapiano has helped propel the genre���s westward march, turning him into one of its most visible champions. That embrace has made South African crowds more receptive to his music and presence. But if someone of Ogulu���s stature can be punished for speaking out against the treatment of immigrants, it would be dishonest to suggest that Adeleke���s silence���or, at best, his ambiguity���on the same issue doesn���t help endear him to South African audiences.

Some Nigerian fans see his silence as strategic. They interpret it as part of a subtle rivalry with Ogulu: that an Amapiano fan base hostile to Burna Boy ultimately benefits Davido. To them, Adeleke has compromised principles of solidarity in order to sell music and appease South African nationalists. His turn to Amapiano is not always viewed as a genuine creative move, but as a calculated reinvention. Having hit a ceiling in the saturated Western Afrobeats market���and watched his contemporaries like Ogulu eclipse him���Adeleke looked south. And in Amapiano, he found his salvation.

That salvation became Timeless, his fourth studio album���an overt pivot to Amapiano, anchored by collaborations with South African producer Musa Makamu (Musa Keys) and artist Lethabo Sebetso (Focalistic). If there���s a price for that embrace, it���s indifference���the indifference that comes when solidarity is seen as optional, not necessary.

But Afrobeats is not as vulnerable to nationalism as Amapiano is. The border is far less consequential to its identity. It���s a sound shaped by a different genealogy���where Amapiano emerges from a domestic class struggle, Afrobeats, like much of Nigeria���s cultural industry, is what filmmaker Biyi Bandele once called ���the child of necessity.��� Nigerian artists understand they are cultural beggars of a sort���products of a weak postcolonial state with limited support systems, making art in the belly of a hostile global empire.

South Africans have been slower to read the writing on the wall���that the curtains are slowly falling on Africa���s most industrialized economy. The attempt to draw borders around Amapiano is, in part, a refusal to confront that reality. Amapiano���s pioneers are the anarchist children of South African neoliberalism. Where Afrobeats artists see opportunity in structure, Amapiano artists see exploitation and the theft of creative freedom. As I���ve argued, nationalism might be useful as a branding tool in the genre���s pursuit of Western success���but it runs against the very spirit of Amapiano.

As Adeleke belted out the songs that made him beloved among Amapiano fans, I couldn���t shake the irony: here was a Nigerian artist commanding a sold-out South African crowd at a time of hyper-nationalism. And then there was the jacket.

On stage, Adeleke wore a custom piece by HollyAndroo���a US-based Liberian���Sierra Leonean designer���styled after the South African flag, with its five colors, and stitched with the words ���Biko ��� Mandela��� under the left breast. These are the names that immigrants in South Africa often invoke when confronted by violence: Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko, the two political figures most associated with Black solidarity and liberation.

It was a striking image. The contradictions of that moment were so glaring, I assumed it would make headlines. But Afrophobes like Gayton McKenzie���South Africa���s Minister of Arts, Sports, and Culture, who built his political profile by encouraging violence against ���illegal immigrants������said nothing. McKenzie had boasted online about the success of the concert and his ministry���s involvement. Yet he saw nothing strange, let alone subversive, in Adeleke���s performance. For nationalists, the presence of a Nigerian artist on South Africa���s biggest Amapiano stage was not a contradiction. It was confirmation. In their eyes, Adeleke was ���kissing the ring.��� He was proof that immigration should be measured not by solidarity or justice, but by utility: by how much labor the state can extract. The South African flag was stitched across his chest, but it was the state that ended up wearing him.

November 26, 2025

Empty riddles

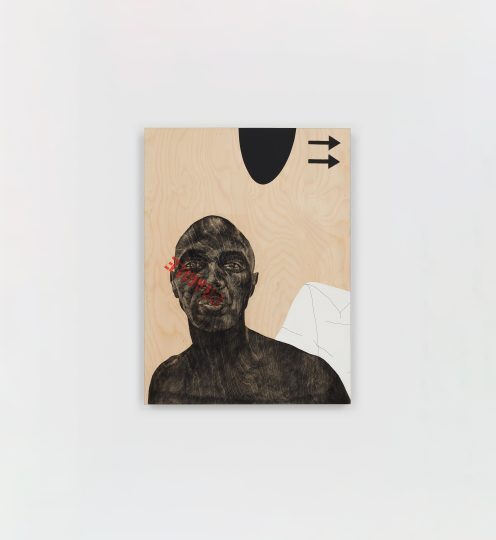

"Identity is Fragile V," Serge Alain Nitegeka (2021). Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

"Identity is Fragile V," Serge Alain Nitegeka (2021). Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.Objects can change as a reflection of how circumstances of the people who carry them do so too. In cases of forced migration, the load is at once physical and psychological. Backpacks, plastic sheets, and duffel bags stretch and take on new forms and textures. These modified objects become adequate to carry personal belongings over long distances. As refugees deal with the immediacy of the journey, negotiate the differences in language, food, weather and the different kinds of obstacles encountered along the way, a sense of uncertainty prevails. It is a labyrinth in which the exit moves all the time, an unstable ground that requires constant adjustment. There is the trauma of the journey, and there is the trauma that led to forcibly leaving in the first place. For artist Serge Alain Nitegeka, who had to flee Rwanda at a young age during the genocide (April ��� July 1994) first to Democratic Republic of Congo, then Zaire, on foot, ���you look at what you can carry and sort of get rid of things you don’t need. It’s a very small list you have to deal with…you know? You have to cut off the excess. And it’s not like you have a lot to cut off, but [you ask yourself]�� ‘what can I carry with me forever, indefinitely?��� ���

After leaving Rwanda, Nitegeka and his family first stayed in a refugee camp in Goma, then moved to Kenya, and eventually settled in South Africa in 2003, where he studied Fine Arts at Wits University. I had a conversation with him that oscillated between reflections of his recent solo exhibition Black Subjects at the Wits Art Museum (WAM) in Johannesburg, his last fifteen years of practice and what mechanisms he has found to cope with trauma.

Installation at WAM depicting “Fragile Cargo” (2010) and “Fragile Cargo VI: Studio Study I” (2012) by Serge Alain Nitegeka. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Installation at WAM depicting “Fragile Cargo” (2010) and “Fragile Cargo VI: Studio Study I” (2012) by Serge Alain Nitegeka. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.Owing to his own life experiences and the effects this continues to have in his creative decisions, Nitegeka believes a lot lies in ���dealing with trauma (���) dealing with the experience of having it and having to carry it because it’s one that doesn’t let go of you. It’s something you live with every day. It’s learning how to look at it, configure it to your own personal physique, your own personal abilities.��� Something salient was his view on how abstraction and minimalist design can counter the mind clutter as a sanitised language that ���denies everything, admits nothing (…) You don���t deal with anything directly. You express yourself in riddles, empty riddles, and you as the author are the one who has the breakdown of what certain forms mean to you.��� In essence, abstraction becoming a shield of sorts, an antithesis to exposure.

But no matter how shielded a person is, identity needs work too, because as abstract as this construct might be, it is fragile, it needs maintenance and, the artist argues, vigilance. This is explicitly posed in the self-portrait Identity is Fragile V (2021), but unravelled most interestingly in one of Nitegeka���s most unassuming pieces titled Fragile Cargo from 2010. In our conversation, we spoke extensively about this work; a small sculpture with a piece of bent plywood tightly fitted in a black frame. The three-dimensional frame stands for the conditions that need to happen for something to keep its shape, to be in a particular way. The containment is visible and there is a balanced tension in how the plywood is delicately fitted. ���It is about identity over material: how it changes, how it’s forced, how it’s molded, how the environment shapes it��� (…) But then that abstraction of identity, how it’s made and how it needs to be maintained was surprisingly very touching to a lot of people that have attended my walkabouts [at WAM]���, shared Nitegeka.

He hadn���t seen the sculpture in more than ten years, and was reunited with it in Johannesburg this year where he ���saw it unravelling in front of my eyes the periods I was going there [to WAM]. I had to go and fix it a bit more, sort of put back, because it’s quite resistant. I put it in that sort of cage to keep it the way it was because, on its own, it kept on wanting to snap back into the plywood it was.���

“Structural Response V,” Serge Alain Nitegeka (2025). Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

“Structural Response V,” Serge Alain Nitegeka (2025). Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.Structural Response V is the latest iteration of Nitegeka���s iconic large scale all-black wooden plank installations that have been widely exhibited in South Africa and overseas. In these installations, visitors are immersed and made to feel small in relation to the scale of the beams that cross above and around them at sharp angles. There is a sense of danger for those who visit the installation. Movement is difficult, but not impossible, echoing the hurdles migrants have to go through as they move from country to country. At WAM, the Structural Response V had a new addition in between the wooden beams: tents lit with a warm light from the inside, giving the impression of occupied spaces. The tents had been previously shown as Camp, a standalone outdoor installation at Nirox Sculpture Park (2025) and Spier Light Art Festival (2025), but never shown as part of the Structural Response. The contrast between the softness of the tents and the hostility of the beams is not only material, it is conceptual. That is, while the beams signal to the hardships of forced migration, the tents point towards a private moment of leisure and rest. These temporary shelters evoke the existence of scenes that the audience does not, cannot, access. Visitors can, however, get close enough to witness that fictional intimacy inside the tents and be part of it as observers.

The artist shared that the tents function as a tool to create a bridge with the audience, as these structures not only refer to the precarity experienced by refugees, but they also signal to other, more joyful, associations with tents: travel, childhood, family holidays, camping and so on. Nitegeka experiments with that overlap between precarity and play in order to get closer to visitors and create what he calls an ���audience relatability.��� He expanded:

So the idea of camping and its associations in South Africa is a relatable experience. So to have that experience of, you know, joy, relaxation, vacation, family, togetherness (…) and you juxtapose that with displaced people. [You] have a situation whereby you reduce the gap of ���the other���, ���the displaced���, ���the asylum seeker���, ���the refugee���… You sort of shorten the gap between the host country and the displaced people (…)�� we all have a kind of common, shared, appreciation to camping or shelter that is a necessity. So on one level, there is an association that’s made, and I think all that goes a long way towards an understanding of tolerance, if you might.

Nitegeka���s “Black Subjects” exhibition at WAM. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Nitegeka���s “Black Subjects” exhibition at WAM. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.For years, Nitegeka only used black in his work, as this related with central themes in his work such as the uncertainty of the future and the void, but also to his identity as a black man. His choice of materials was intentional from the get go, as he mostly worked with found materials and crates because ���they’ve lived in the world, they’ve done things.��� Although most of Nitegeka���s works aren���t figurative, the figures that do appear are always the same ones covered in all-black suits. The suits strip away physical features, past experiences and individual identities, rendering the figures anonymous and equal within their shared circumstances. The ���subjects��� Nitegeka depicts struggling through uneasy paths, pushing against walls, and lifting mended objects could be anyone. As characters of an unfinished story, these figures could be spotted at WAM in the film Black Subjects (2012) and in large scale paintings like Displaced Peoples in Situ: Studio Study XXXVIII (2025). He explained that ���the reason for that conceptually, is to put the same people in different environments… that they are moving. There’s this movement: today there are in this painting, then they’re going to end up in a different painting, and they’re going to be in a different environment and landscape. They’re going to be figuring out and in this mess where they, you know, pushing things, they’re trying to organize, and this perpetual, never ending exercise that they���re involved in. They’re in this liminal space indefinitely������

In 2008, while he was in his third year of Fine Arts at Wits University, Nitegeka rubbed himself with a mix of Vaseline and crushed charcoal. Once fully covered, he jumped inside a crate, closed the lid, hammered himself in and then tried to get out. Because of the charcoal, as he attempted to get out, he left traces of his frantic efforts on the wood. What was later exhibited in the student show were broken crate pieces with imprints of his body, remnants of that performance nobody witnessed. Back then, Serge deliberately subjected himself to difficulty in producing that work, pursuing a type of permanent ���readiness��� ��� an impossible task that continues to obsess him. He shared about his rationale:

���The mindset is to be ready, physically, mentally and constantly put myself into the unknown and uncertain positions and see how I respond to sort of learn something about myself���Some of it is quite labor intensive and physically demanding. I think the idea is to have that chosen suffering to prepare myself�� for the unchosen suffering. I think it’s a counter trauma, sort of self generated response to that. I’ve read up quite a bit about trauma and how different people deal with it, but the one I relate to is the one of physical exhaustion, exertion is a way of living with something. Momentarily check out, but it’s also an affirmation that you’re strong, you know, that you’re not as vulnerable, and that you’re gonna be ready for the next thing.���

Nitegeka���s “Black Subjects” exhibition at WAM. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Nitegeka���s “Black Subjects” exhibition at WAM. Photo Nina Lieska. Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.In the liminal space between the known and the unknown, adaptability emerges as a necessity. People change in the movement across countries because they have to, and traces of that history are visible: in the body, in the adoption of new cultures and languages, and sometimes even in weary rehearsals of ���readiness��� for whatever might come. There is also nostalgia in the pain that accompanies the journey, as the artist described on his Instagram: ���Getting caught up in the reordering of perceptions amid frequent repetitions, failures and triumphs builds character. One endures, whatever it takes. However, one never gets quite there. There is history in the way. You look back, indulgent of the past, to a time when things were a bit more settled.���

Serge has never gone back to Rwanda, though he says he would like to. He mentioned he often thinks about his work as a celebration of the endurance of the human body and the human mind. His art speaks about a series of experiences, some very private, which most of the audience will never decipher because it is posed as a riddle that can���t be solved. The point being that, to build that ���audience relatability��� Nitegeka speaks about, it is not necessary for the�� people engaging with his work to know about the exact intention or experience behind it, but rather to have an openness to the various social and emotional associations objects might carry. For some, a tent may relate to joy; for others, it may evoke memories of displacement. The key is if such differing responses can find room beside each other. If an artwork���be it through a piece of plywood or a lit tent���can prompt that, and if it can resist evolving meanings in time, then part of the empty riddle���s work is already done.

November 25, 2025

Heritage on horseback

Horsemen (Mahayan Doki) raging out of the palace to clear a path for the Emir���s procession at the Durbar Festival, 2025. ��Dave Alao for Cultural Canvas.

Horsemen (Mahayan Doki) raging out of the palace to clear a path for the Emir���s procession at the Durbar Festival, 2025. ��Dave Alao for Cultural Canvas.What is a Durbar?

According to the Oxford Dictionary, a Durbar refers to the court of an Indian ruler or a ceremonial reception held by an Indian prince or British governor. However, in Nigeria, a durbar is much more than a colonial holdover; it is a vibrant expression of cultural identity, Islamic tradition, and royal heritage.

Most famously celebrated in the ancient city of Kano, the Durbar has been observed for more than five centuries. The Kano Durbar is a spectacular showcase of horsemanship, regal pageantry, and cultural performance. Held annually during the Islamic holidays of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, the festival features grand processions of horses, musicians, and dignitaries, culminating in a ceremonial display of power and allegiance to the Emir of Kano.

The Durbar festival is a dazzling display of northern Nigeria���s regal heritage, celebrated in Kano, Ilorin, Jigawa, and other northern states. Though rooted in Islamic tradition and royal pageantry, each region brings its own historical, sociopolitical, and cultural nuances to the celebration.

Kano remains the most prominent stage for the Durbar. The city���s version is widely regarded as the most elaborate, visually intense, and well-attended durbar in Nigeria���and arguably Africa. This multi-day event, steeped in military symbolism, features synchronized processions of royal guards, the Hawan Daushe and Hawan Nassarawa parades, intricately dressed titleholders, and a dazzling array of horsemen from across the emirate.

Unique to Kano are awe-inspiring side shows such as the Hyena Man���s daring street performance, horses adorned in full royal regalia, and majestic drums played atop dromedaries���reserved solely for the presence of the Emir. These elements blend mystique with ceremonial formality. The Durbar also transcends spectacle, serving as a platform for the Emir to raise important community issues, including erosion control and police infrastructure.

The Ilorin Durbar offers a markedly different but equally powerful cultural experience. Ilorin, the capital of Kwara State, is predominantly Yoruba with a strong Fulani presence. Like Kano, the Durbar here centers around the Emir, Alhaji Ibrahim Sulu-Gambari, and is held during the Eid festivities.

In Ilorin, the Durbar emphasizes cultural fusion and social harmony, reflecting the city’s unique identity as a meeting point of Yoruba, Fulani, and other ethnic groups. The Emir���s procession is understated yet symbolic: no armed security, only a traditional whip-bearing entourage weaving through a historic town square rich with faith and festivity.

Families and community groups dressed in matching Aso Ebi (coordinated attire) add a celebratory, grassroots dimension. Notably, Ilorin���s youth play a vital role���capturing and livestreaming the events, turning the Durbar into a global digital showcase while preserving its sacred nature.

With the Kano Durbar suspended in 2024 and 2025 due to the ongoing royal dispute between Muhammadu Sanusi II and Aminu Ado Bayero, attention has shifted to lesser-known but equally rich traditions in states like Jigawa.

Although Jigawa���s Durbar is newer in public perception, it is deeply rooted in history. Although not as structurally elaborate as Kano���s, the event is rich in symbolism and local loyalty. Governor Umar Namadi personally received the Emir of Dutse, Hameem Nuhu Sunusi, along with his 26 district heads���each of whom knelt in royal obeisance, symbolizing respect and unity.

Beyond celebration, the Emir���s speech tackled community challenges such as erosion and flooding, urging state-led solutions. Each district presented uniquely decorated horses, showcasing the emirate���s internal cultural diversity. Crowds of children, women, and elders filled rooftops and balconies, demonstrating a deep, unfiltered connection between the people and their heritage.

The Ojude Oba Festival in Ijebu Ode, Ogun State, deserves special mention. Rooted in Yoruba tradition, Ojude Oba shares some parallels with the northern Durbar, particularly its equestrian parades and celebration of royal leadership.

Held during Eid al-Adha in honor of the Awujale (king) of Ijebuland, Ojude Oba emphasizes social hierarchy, fashion, and diaspora involvement. Unlike the aristocratic tone of northern Durbars, Ojude Oba embraces democratic pride in cultural heritage, welcoming both Muslims and Christians in a colorful, inclusive celebration.

Equestrian parades, coordinated dances, rich textiles, and historical reenactments led by Balogun families and community organizations create a vibrant cultural identity that resonates both locally and internationally.

Notwithstanding regional differences, all Durbar festivals and Ojude Oba share several unifying elements, including: regal equestrian displays (horseback riding remains central, symbolizing strength, dignity, and royal prestige); cultural embellishments (music, ancestral chants, and intricately adorned regalia elevate both the spiritual and aesthetic dimensions of the events); leadership and symbolism (the presence of Emirs and kings reasserts the enduring relevance of traditional authority in civic life); and community participation (from elders to tech-savvy youth, intergenerational involvement fuels the festivals��� ongoing vibrancy and mass appeal). Kano���s royal grandeur, Ilorin���s harmonious fusion, Jigawa���s grassroots revival, and Ijebu Ode���s communal pride highlight a powerful truth: while Nigeria is a tapestry of cultures, tradition continues to be a unifying force. The Durbar, in its various forms, reaffirms the authority of heritage and the evolving dialogue between history, leadership, and the people. In an era often defined by fragmentation, the Durbar remains a cultural beacon, reminding Nigerians and the world that identity can be both richly diverse and beautifully shared.

November 24, 2025

When Moscow looked to the horn

Small boats in Berbera, Somaliland. Image credit Matyas Rehak via Shutterstock �� 2022.

Small boats in Berbera, Somaliland. Image credit Matyas Rehak via Shutterstock �� 2022.During a hot sunny day in Berbera, the American delegation led by Senator Dewey F. Bartlett arrived. It was in 1975, and the port city, a sleepy coastal city-turned-Soviet outpost, found itself at the center of a tug-of-war. As the American senators followed the Somali military officer giving them a tour, they observed and noted any signs that confirmed the allegations that Somalia is hosting a missile center owned by the Soviets. The visit, referred to in the US diplomatic cables as the ���Berbera Affair,��� became important for various actors to present a geopolitical narrative suited to their interests. The US secretary of defense at the time, James Schlesinger, claimed that the Soviets had built a missile storage facility and presented pictures. It was followed by the American lawmakers using this issue as a justification for opening a military base in Diego Garcia; the Soviet Union didn���t miss the opportunity to paint the visit as another American imperialist expansion in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. For Somalia, though, President Siad Barre juggled loyalties to Moscow, to Washington, and above all, himself. He used the visit to project an image of independence from Soviet influence in Somalia, as the latter had enjoyed strong relations with Moscow.

Berbera again finds itself entangled with a geopolitical competition whose main actors include not only the US but also China and the middle powers of the Middle East.�� Somaliland, which formally reclaimed its sovereignty from Somalia in 1991, is bargaining Berbera���s strategic value to gain something it has craved for so long: international acceptance and recognition. This piece draws parallels from historical events of the Cold War to help us understand the significance of this part of the world and why the world needs to understand what���s at stake. Berbera���s location is key to securing global shipments passing by the Gulf of Aden, one of the world���s busiest maritime corridors, a gateway to landlocked Ethiopia and South Sudan. As Houthis��� attacks on international shipments escalate as a result of Israel���s war in Gaza, this maritime route is increasingly getting the attention of major powers.

Berbera lies in the Gulf of Aden, facing the Yemeni coast in the north. For centuries, ships from Arabia, Asia, and beyond have stopped there to trade salt, goods, and hides. When British colonialism arrived, they found Berbera as a strategic location, basing their governor there before moving their administration to Hargeisa, Somaliland���s capital.

Decades later, a global power saw the same strategic promise. In 1962, the Soviets secured an agreement to build a deep seaport in Berbera, a project that was concluded in 1969, the same year the military leader, Mohamed Siad Barre, staged a military coup. By the 1970s the Soviets completed the long runway in Berbera���s airport, long enough that the Americans suspected it was serving military purposes for Moscow.

Relations with Moscow remained intact, even stronger, as the military regime decreed scientific socialism as the state ideology, a break from the multiparty democracy the civilian government had adopted. A treaty of friendship and fraternity was signed in 1974, the first of its kind that Moscow signed with an African state after Egypt. This opened the fledgling postcolonial state with much-needed support in infrastructure, military assistance, and technical expertise. For Moscow, it presented an opportunity to project power and influence in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean, something Barre agreed to as a fellow socialist comrade.

The Soviets slowly built a naval base in Berbera. Radoslav A. Yordanov wrote in his doctoral research on the Soviet Union���s relations with Ethiopia and Somalia that the Soviet construction of a missile storage site in Berbera was conducted without the knowledge or even understanding of the Somali military government. He refers to US delegation reports of perceived lack of knowledge of the Somali officers of Moscow���s activities in Berbera.

Meanwhile, the US government kept expanding its security and diplomatic relations in Africa. It remained an ally to Ethiopia, Somalia���s regional nemesis, and maintained a CIA listening station in Kagnew, in modern-day Eritrea. Washington saw an ally in Ethiopia in containing the spread of communist reach in Eastern Africa by propping up the imperial government of Ethiopia militarily and economically.

However, this did not last long. A wave of changes rocked the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea. Ethiopia���s emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown by a Marxist military regime in 1974, and seeing the fragile Ethiopia, Somalia launched a major war to annex the Somali region under Ethiopian control. The Soviets were unhappy about the two communist allies in the Horn fighting, tried to mediate first, but eventually sided with Ethiopia. At the time, The New York Times reported the expulsion of Soviet military advisors from Somalia, who numbered around 6,000 people. For long, the Soviet Union was perplexed by the territorial dispute between the two countries. Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader from 1953 to 1964, noted how challenging it was for him to deal with this situation in his memoir.

Berbera again became the center of this relationship as the Carter administration suspended aid to Ethiopia. Somalia sought to align itself with America���s allies���namely, Egypt, under Anwar Sadat, and the Shah of Iran, who both promised assistance to Somalia against Ethiopia.

Half a century later, flags have changed, but the scripts remain the same. Where the Soviets operated facilities in Berbera, now it���s Emirati contractors who are paving the runways. Chinese investors were eyeing the Port of Berbera as an export point for the oil and gas from Ethiopia, and Somaliland���s leaders are playing all these cards against one another in an attempt to secure recognition. The Emirati-owned company DP World has developed the Port of Berbera into a massive project, one of the several ports DP World is managing in Africa. In today���s Horn and Eastern Africa, leaders aren���t calling Washington or Moscow in times of emergencies, but they���re calling Abu Dhabi, Ankara, and Doha, shifting the change in geopolitical order in the region. For instance,�� when the Ethiopian government was embroiled in a bitter civil war in the Tigray region, it was the UAE, Turkey, and Iran that came to Ethiopia���s aid, not the US or the Russians.

Although the Emirates abandoned their base project in Berbera as their calculations in the Yemeni war changed, the base, which was initially built by the Soviets, remains up for the highest bidder. The US government expressed an interest and sent an AFRICOM delegation in what many speculate is the great American return to Berbera. The US today is not fighting a major power in the Red Sea but rather a non-state actor group in Yemen, the Houthis, who are threatening the global shipments as their conflict with Israel escalates.

Contestation for legitimacy is at the heart of Somaliland���s geopolitical calculation. As the West championed democracy promotion globally, Somaliland successfully implemented multiparty democracy with a good record of electoral success. Now, as the language of politics intensifies around great power competition, Hargeisa is aligning its narrative around geopolitics. As Bruno Ma����es notes, ���The case of Somaliland is really illustrative of what the US order has become.��� Ten years ago, it was trying to get recognition, arguing that it had a vibrant democracy. Then it realized the US cares nothing about this, so it started arguing it could help counter China in the Red Sea and the Horn. In 2020, Somaliland formed diplomatic ties with Taiwan to the displeasure of China. As the Asian power tried to dissuade Somaliland from this, the latter seemed locked into furthering this agenda for greater cooperation with the US, and now conservative figures in the Congress and the Senate are calling on President Trump to seek deeper cooperation with Somaliland.

Russia under Vladimir Putin is also expanding its network in the African continent. As the Crisis Group recently noted, the Russian state-affiliated Africa Corps (formerly known as the Wagner Group) is currently active in multiple conflict sites in Burkina Faso, Mali, and the Central African Republic. Sudan, which was caught up in a brutal (uncivil) war, has reportedly been courted by Putin for access to a base in the Red Sea. Its foreign minister, Ali Youssouef, said that there are no obstacles to a Russian Red Sea base.

But most importantly, Russia seems not to abandon its former Soviet outpost in Berbera. In October 2017, the Russian delegation arrived in Somaliland to discuss deepening ties, and in 2025, a letter surfaced online from the Russian embassy in Ethiopia reaching out to the Somaliland government to schedule a visit. Social media users speculated about the purpose of that planned visit and the details involved, but I wouldn���t rule out the Russian glory of seeing Berbera���s base back in their fold.

November 21, 2025

How much does a Nigerian intellectual cost?

Lagos. Image credit Tolu Owoeye via Shutterstock �� 2023

Lagos. Image credit Tolu Owoeye via Shutterstock �� 2023In the early 2000s, during one of the prolonged strikes of the Academic Staff Union of Universities that shuttered Nigerian campuses for months, I encountered an essay in the Nigerian Tribune that challenged my understanding of literature’s place in the world and the mediating power of language. The article, written by the late Abubakar Gimba, examined the government���s criminal neglect of the education sector while also appealing to striking academics to consider the children caught in the crossfire of institutional failure.

I was deeply drawn by the architecture of his argument. The way his prose moved from indictment to appeal without sacrificing its intellectual honesty; literature as a kind of surgery on the body politic, painful but necessary, demanding that we confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and our society.

I came to literature through writers who understood that in societies still bleeding from the wounds of colonial extraction, one of the writer���s key obligations was to serve as witness, agitator, and keeper of the collective memory, a generation of intellectuals who refused to accept that independence had been achieved merely by the lowering of one flag and the raising of another.

From the anti-colonial pamphleteers of the 1940s to the Newswatch generation, Nigeria���s intellectuals once stood between citizen and state like unpaid sentries. Dele���Giwa lost his life to a parcel bomb in 1986; Ken���Saro���Wiwa lost his to Abacha���s hangman in 1995. Between 1994 and 1998, hundreds of writers, editors, and organisers slipped through the borders to escape Abacha���s bloodlust. The National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), formed in May 1994, was the fulcrum of exile politics. Wole Soyinka, Anthony Enahoro, Ayo Opadokun, and others carried the struggle from London basements to Capitol Hill hearing rooms. Within this matrix was Bola Ahmed Tinubu, a fugitive senator with deep pockets and deeper ambitions.

Depending on who���s telling it, Tinubu was either a hero of Nigeria���s democratic struggle or a successful Third Republic politician whose financial contributions earned him proximity to the moral glow of exile politics and helped launder his credentials.

According to NADECO lore, Tinubu, who had fled Nigeria through a hospital window in those heady days, became a source of financial succor to the movement���s exiled group of intellectuals and activists: trading rice with Taiwan to support the cause, in Soyinka���s telling; contributing to the purchase of the transmitter that powered Radio Kudirat, the pirate station that rattled the junta at large. Political exile makes for complicated bedfellows: Trotsky once found himself dependent on the hospitality of bourgeois democracies he had spent his life denouncing; the ANC in exile accepted funds from Scandinavian governments and multinational unions with their own interests to protect; Ho Chi Minh collaborated briefly with the American OSS against Japan. Sometimes the geography of the struggle blurs conviction and convenience.

Tinubu returned to Nigeria following the restoration of democracy in the late 1990s as a hero, Saul among the prophets. His NADECO aura played no small part in his ascension to the governorship of Lagos State. When Chief Anthony Enahoro returned from exile in 2000 to a reception hosted in Lagos, Frank Kokori, the respected unionist and stalwart of the pro-democracy struggle, remarked:

What I told Pa Enahoro in America has today come to pass. Revolutionaries must have a base. We don���t just boycott the political process. If Tinubu does not reign (as governor) in Lagos today, we would not have been able to give Pa Enahoro this kind of rousing welcome���

More than two decades later, when Tinubu was elected President after the 2023 elections, a columnist writing for the Vanguard described it as, ���a reward for NADECO, June 12 struggles.���

Yet the story of NADECO reveals the deeper pathology that would eventually consume Nigeria’s oppositional culture. The same individuals who once organized against military dictatorship would later become architects of the very system they had once opposed: radicals turned governors, columnists turned presidential advisers. Reuben���Abati swapped The Guardian���s back page for Aso���Rock���s briefing room; Femi���Adesina would do the same under Buhari. The title ���Special Adviser on Media and Communication��� became Abuja���s gilded quarantine for former scolds.

Meanwhile, the lecture halls that produced earlier generations of intellectuals and visionaries have progressively declined. Over the last quarter-century, Nigerian universities have been closed for nearly 1,600 days, equivalent to more than four academic years, due to ASUU strikes. Even when classrooms reopen, they do so on starvation rations: the 2024 federal budget allotted barely 7% to education, less than half of UNESCO���s recommended floor.

Tinubu���s evolution, from NADECO financier to one of Nigeria���s most powerful political godfathers, represents the systematic and structural transformation of opposition into complicity. More than any of his contemporaries, he grasped the psychological economy of power and had a practised instinct for making even his opponents dependent on his largesse. What has emerged under his watch is a sophisticated system in which intellectuals, clergy, thugs, and politicians alike have been drawn into a single patronage network whose gravitational pull is so strong it now defines the political horizon itself. At least five governors from the opposition party and a retinue of state and federal legislators have recently defected to the ruling APC, marking a near-perfect consolidation of a decades-long project of converting dissent into property. The Nigerian state, having learned from the Abacha years that direct repression generated too much international attention, developed more sophisticated methods for neutralizing opposition. Instead of killing intellectuals, it began buying them.

Still, for clarity, we must expand our lens beyond individuals and consider structure. That the post-colonial state in Africa inherited its colonial borders along with the colonizer’s extractive psychology has been rigorously observed. The unfortunate archetype of nationalist intellectuals, who once promised liberation, has been thoughtfully drawn out, separately, by Fanon and Cabral, as the transmission line between the nation-state and a predatory bourgeoisie. Yet Nigeria���s variant of this tragedy is intensified by its peculiar history of dehumanisation.

The British did not so much govern Nigeria as manage its competing interests and contradictions. To the colonial authorities, Nigerians were resources, measurable in tonnage, taxation, and labor. The moral questions of citizenship and belonging were ceded to the new political elite who inherited the machine. What ensued, predictably, was an existential scramble for positioning. The government became a factory for privilege, and ordinary Nigerians were the raw material it consumed.

The deeper tragedy lies in how this extractive order deformed the moral imagination. Few governments in human history have treated their citizens with as much disdain as the Nigerian government. The people have been literally made to eat shit and say thank you while at it. In a society where the state���s primary function is predation over protection, the people have learned to survive through mimicry: by bending rules and currying favour, shamelessly cultivating proximity to power, a Darwinian survivalism that has since hardened into culture.

This is why the Nigerian obsession with status and the bloated sense of self-importance should not be mistaken for mere vanity. It is a kind of self-defence, a desperate performance of worth in a system that recognizes only power and indexes your humanity to wealth. To be poor is to be invisible. And so, every act of corruption, every betrayal of principle, every silence purchased with a contract or appointment, is animated by a quiet terror: the fear of returning to nothingness.

It is from this context that the contemporary Nigerian intellectual class emerges, more mirror than counterforce, fluent in critique, yet complicit in the very hierarchies they diagnose. To speak truth to power has become less a civic duty than a career strategy. Nigeria���s sheer size, its violent fusions of ethnicity and religion, and its oil wealth have all intensified the collapse of trust between citizen and state. The result is a moral economy where the vocabulary of value has been inverted: wealth without work, faith without ethics, intellect without integrity.

Under this dispensation, the intellectual who maintains principled opposition to corruption is seen as naive or, worse, unsuccessful. The writer or journalist who refuses to sell their platform to the highest bidder is viewed as lacking business acumen. The academic who turns down lucrative government consultancies to maintain their independence is considered foolish rather than principled.

Nowhere are these issues more evident than in the approach to political engagement. What was once a testing ground for ideas and ideals has since degenerated into another avenue for personal advancement. The phrase ���politics is not a do-or-die affair��� has been weaponised to justify the most cynical forms of opportunism, as if treating politics as a matter of life and death were somehow primitive rather than an appropriate response to systems that literally determine who lives and dies.

When former critics become government apologists, the very language of accountability becomes corrupted. Citizens lose the ability to distinguish between propaganda and analysis, between genuine reform and cosmetic changes designed to manage public perception. This has created more than a crisis of interpretation in Nigerian public life.

The absence of intellectuals capable of articulating a hope grounded in serious analysis and concrete possibilities has left Nigerians vulnerable to both despair and false prophets. Within a single generation, a tradition that had produced some of the world���s most powerful voices for justice and human dignity has been largely destroyed. The country that gave the world Achebe���s moral clarity and Soyinka���s righteous fury now struggles to produce intellectuals capable of sustained critique of even the most obvious failures.

The digital revolution, which might have democratized access to information and expanded platforms for dissent, has, instead, accelerated the degradation of public discourse. Social media platforms that could have served as modern equivalents of the newspaper columns where intellectuals once published their critiques have become echo chambers of misinformation and tribal antagonism.

The Occupy Nigeria crowd of social media agitators, who contributed significantly to hounding Goodluck Jonathan out of office, have also found plush jobs in government or found themselves close enough to leverage influence for personal ends. The space that figures like Abubakar Gimba once occupied, characterized by thoughtful, nuanced, and morally serious engagement with public issues, has been replaced by performative outrage and simplified sloganeering that digital platforms reward.

Any counteracting effort, beyond nostalgia for a golden age that may have been less golden than memory suggests, must begin with a recognition that intellectual independence cannot be sustained in conditions of economic desperation. Where rent is unpaid and children go hungry, the space for moral courage inevitably collapses into the daily arithmetic of survival. Nothing that can be said about integrity will hold if the social structure rewards sycophancy and punishes honesty. Nigeria���s unending cycle of poverty and precarity can be effectively seen as an instrument of control that renders citizens docile through exhaustion.

But what is made can be unmade. The search for a just society has not been abandoned. The moral voice has become itinerant, diffused into new forms across non-traditional routes; data collectives pushing for transparency, feminist movements with unrelenting civic courage, satirists, independent presses, and citizen archives. A new civic imagination is struggling to assert itself. It is imperfect, fragmented, and often co-opted, but the work of re-establishing a baseline for shared ethical imagination continues. The #EndSARS protests revealed a generation���s rage and its longing for dignity, a demand for accountability rooted in the simplest of civic rights: that a citizen���s life should count. Despite the fresh wave of migration it triggered after it was crushed by the Nigerian military, ghosts of its discontent still linger.

Yet moral renewal cannot rely on outrage alone. It will require the deliberate rebuilding of the intellectual and imaginative infrastructure that allows a people to see themselves truthfully. For all the failures of the state, the imagination remains the one institution the powerful cannot fully capture. It is there, in the stubborn work of writing, teaching, organizing, and making, of refusing to be silenced or bought, that moral authority can be rebuilt. In classrooms kept alive by teachers who refuse despair; in newsrooms that still risk integrity for accuracy; in reading collectives, film labs, community libraries, and digital platforms that prize inquiry over impression.

As with everything else that ensures their continued survival, Nigerians must, on their own, continue the slow restoration of conditions in which knowledge can exist for its own sake, untethered from the demand for utility. They must lean further into new forms of patronage and community, networks of solidarity that enlarge interiority: citizen-funded art spaces, regional residencies, literary festivals, and community gatherings that nurture the life of the mind. These are the laboratories where the moral imagination must again come alive.