Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 141

February 2, 2021

The rise and fall of a Nigerian labor hero

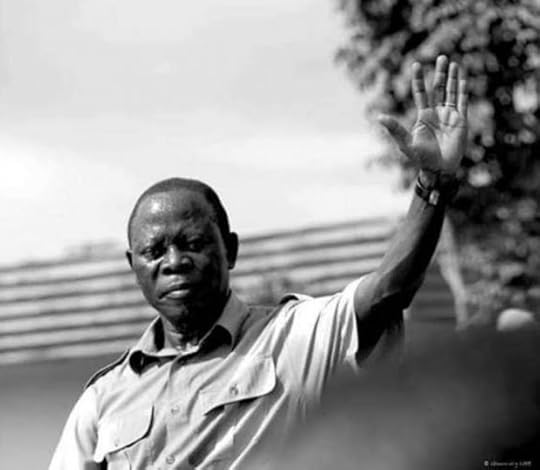

Adams oshiomhole in a rally. Image via Wikimedia Commons CC.

Adams oshiomhole in a rally. Image via Wikimedia Commons CC. Adams Oshiomhole is probably the closest thing to political power Nigeria���s labor movements will ever have. In a remarkable career, over four-and-a-half decades, he rose to the top of both the trade union movement in the country, became a state governor and then national chairperson of the All Progressive Congress (APC), one half of Nigeria���s two-party system. In mid-2000 his political career came to a dramatic end when a court upheld his suspension from the APC. Vibrant and effective, Oshiomhole���s career trajectory in many ways represents the wider political subjugation of Nigeria���s labor movement. How this labor hero was ultimately defeated, is worth a short note.

The 1980s and 1990s marked a decade of turmoil for the Nigerian Labor Congress (NLC), the country���s largest trade union federation. Its troubles were worsened by the military���s repeated attacks on the leftist bastions of the labor movement. However, Oshiomhole���s appointment as NLC president in 1999, after Nigeria’s return to civilian rule, seemed to mark the opening of a new heroic chapter in the development of the movement.

Oshiomhole, now 68, came from a modest background in Edo State in southern Nigeria. He was fortunate to find factory employment with Arewa Textiles in Kaduna, a city in the northwest known as a trade and transformation center. His colleagues soon elected him union secretary. In 1971, responding to bad labor practices at his workplace, he led a shop-floor revolt. Four years later, he had become a full-time trade union organizer. Around this time, he left for the UK to study labor and industrial relations at Ruskin College in Oxford. (Ruskin had developed a reputation as an educational institution providing higher education to workers.) Later, he would also study at the National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPS) in Kuru, Plateau State.

In 1982, Oshiomhole was appointed as the general secretary and chief executive of the��National Union of Textile Garment and Tailoring Workers of Nigeria. As a 2017 report into the union���s fortunes would note: ���At its peak in the 1980s, the textile industry employed up to 500,000 workers directly, making it the second largest employer after the government.��� This made Oshiomhole one of the most powerful trade union leaders in Nigeria.

Oshiomhole���s emergence as a labor and political leader is best understood within the wider historical trajectory of the NLC. From the mid-1980s, the junta of Ibrahim Babangida (1985-1993) clamped down on radical organizations and social movements as part of its imposition of neoliberal structural adjustment programs. The labor movement and the National Association of Nigeria Students (NANS) were hounded by restrictions and state agents at every turn.

In the NLC, the internal rift between progressive and the liberal forces���epitomized by the battle between Jonathan Ihonde of the Academic Staff Union of Universities and Ali Ciroma of the Amalgamated Union (Ciroma was pushed out)���led to the emergence of the charismatic Paschal Bafyau, a moderate, as president of the NLC. Unwilling to kowtow to the radical momentum of the 1990s during which the June 12, 1993 revolts against dictatorship broke-out, Bafyau couldn���t lead a coherent NLC and Babangida intervened again with a caretaker leadership. Oshiomhole, then general secretary of the National Textiles and Garments Union, was chosen to be Paschal Bafyau���s vice president. He immediately hit the ground running imbuing confidence and overseeing the rebuilding of labor���s fighting capacity.

Elected as NLC president in 1999, Oshiomhole became the darling of all workers fighting anti-labor practices and using his oratory prowess in political debates to inspire mass action. The Oshiomhole of this era bore a striking resemblance to Michael Imoudu, the legendary ���Labor leader No 1,��� who led the 1945 Cost of Living Allowances (COLA) strike that lasted for 45 days and shook the foundations of the colonial state.

Oshiomhole had his most heroic moments as NLC president. Under him, workers went on general strikes seven times. These strikes were about salary increases but also fought against the deregulation of the oil sector and the continued implementation of structural adjustment policies.

Oshiomhole understood the power of strikes and mobilized for them with great vigor. He usually relocated NLC structures to Lagos as the commercials center once a strike was to be announced. His bold leadership stirred President Obasanjo to accuse him of running a parallel government in 2004.

However, the tail end of Oshiomhole���s second tenure at the head of the NLC saw the evolution of the labor hero. During this period, the NLC joined the National Privatization Council, which served as the engine room for the destabilization of the Nigerian economy as production-based, marking a clear betrayal of all that labor had been fighting against. This also meant that NLC was part of the council that supervised the sale of government-owned industries, shedding large numbers of jobs while empowering cronies in the private sector. By the end of Oshiomhole���s tenure, the labor movement was left in tatters industrially and politically.

Oshiomhole was drawn into electoral politics, helping to establish the Labor Party in 2007. However, this is where the parallels between Oshiomhole and Imoudu end. While Imoudu was left leaning in practice, Oshiomhole jilted the Labor Party in favor of the bourgeois dominant formation, the Action Congress (AC), in the same year in which the Labor Party was formed. (Oshiomhole only ran a double ticket after union pressure.) The AC ultimately merged with similar parties to form the All Progressives Congress (APC).

Oshiomhole and his allies registered the Labor Party and handed it over to liberal labor leader Dan Nwanyanwu. Under this leadership the party sold frontrunner tickets to the highest bidder while restricting union members from democratic participation. The party has yet to recover from the scars of this experience.

After gaining the governorship seat under the AC banner, Oshiomhole actively worked to prevent workers strikes. In Edo state, workers went on strikes at their union levels, but Oshiomhole violently prevented a general strike. The biggest general strike in Nigeria so far has been the Occupy Nigeria strikes in 2012. Instead of supporting the protests, despite being in the opposition, Oshiomhole helped to break the strike through a negotiation committee of which he was major state actor.

As governor, he also conducted the largest casualization of the work force by any state government thus far.��More than 50,000 workers, employed through the Youth Employment Scheme (YES) in 2009, were sacked in 2015 when Oshiomhole claimed on television that he ���picked them��� from the ���gutters.�����Since this period Oshiomhole has used his overwhelming influence on both the NLC and the Trade Union Council (TUC) to ensure that general strikes are virtually forbidden under the strong-handed rule of the APC.

Oshiomhole gained a popular following in mainstream politics, retaining his characteristic khaki ���comrade���s jacket���, but was increasingly seen through the godfather persona of ���OshioBaba.��� He has sadly also remained an example and a mentor to many in the labor movement, and labor activists are frequently seen in alliances with mainstream politicians in the PDP and APC. Labor bureaucrats have abandoned the Labor Party and like Oshiomhole, openly flirt with the ruling class. This is one reason why the movement lost two general strikes. However, the formation of a cluster of revolutionary organizations has brought new hope to the left and radical working class. Member organizations of the Coalition for Revolution (CORE) have been leading #RevolutionNow; the struggle precursor of the #EndSARS Protests that shook the world in late 2020.

Adams Oshiomhole rose to limelight and greatness while serving the working people as a labor leader. He managed to run Edo state government for two terms playing the devil���s advocate. In power, Oshiomhole denied workers most of what he fought for during much of his tenure at the helm of the NLC. Oshiomhole���s recent rise and fall within the APC is often viewed as the final desecration of a labor icon. Yet, it is evident that the workers movement lost its visionary leadership much earlier.

The missing 27 billion

South Africa���s first consignment of COVID-19 vaccine from the Serum Institute of India (SII). Image via GCIS via Flickr CC.

South Africa���s first consignment of COVID-19 vaccine from the Serum Institute of India (SII). Image via GCIS via Flickr CC. This post is part of our series ���Climate Politricks.���

Africa loses about $27 billion per year – an amount equivalent to about 50% of the continent���s public health budget – due to profit-shifting to tax havens.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented the world with an unprecedented health and economic crisis. The pandemic occurred in the context of already weakened economies in Africa, with high levels of debt and increasing fiscal deficits. Given the present precarious conditions of many developing countries, more and better effective use of Official Development Assistance (ODA) could play a crucial role in addressing the immediate impact of the pandemic. In the medium to long term, however, further increases in the mobilization of domestic revenue are critical for improving health systems and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Over the last two decades, African countries have implemented various tax policy reforms aimed at improving domestic resource mobilization. As a result, tax revenues have increased in absolute terms since 2000 with an average tax-to-GDP ratio of about 17 % between 2000 and 2018. However, the amount is lower than the 20% minimum tax-to-GDP ratio needed to finance the SDGs in developing countries. The financial gap for African countries has been further exacerbated during the current pandemic and is likely to persist. Under different scenarios, the financial gap in Africa is expected to be between $130 billion and $410 billion from 2020���2023, with the debt-to-revenue ratio expected to reach 27 %.

Despite progress, the collection of tax revenue in Africa still faces a number of structural challenges. Large numbers of small-scale informal services and agriculture dominate the majority of African economies, resulting in low effective tax bases and limited tax compliance. The incorporation of small informal sectors into the tax system can be very costly while generating small net revenues. On the other hand, improvements in the efficiency of tax collection can be made in the management of corporate income taxes, and in curbing illicit financial flows and unnecessary tax exemptions. For instance, Africa could bridge half of its SDGs funding gaps by curbing the total annual capital flight of US$88.6 billion per year, which is more than the amount the continent receives in ODA of US$48 billion or foreign direct investment (FDI) of US$54 billion.

In addition to limited local institutional capacity, efforts by African countries to curb illicit financial flows and increase revenue from corporate income taxes has been constantly undermined by weaknesses in international tax rules and profit-shifting strategies by multinational corporations and wealthy individuals. Africa loses about $27 billion per year, an amount equivalent to about 50% of the continent���s public health budget due to profit-shifting to tax havens. Moreover, rich nations often aggressively negotiate with developing countries to ensure reduced withholding tax rates. This essentially means that African governments are providing some of the largest withholding tax cuts for richer nations. Such approaches significantly restrict African countries taxation rights and may further lead to a downward trend in tax rates due to competition between African countries.

Eliminating unnecessary tax exemptions can also significantly increase tax revenues in Africa. In order to attract foreign direct investment, African countries are losing large amounts of tax revenue due to special tax arrangements, such as tax exemptions, reduced rates, tax holidays, and royalty concessions. Tax exemptions for various government-to-government aid-related projects are also very common in Africa. According to a report by the African Tax Administration Forum, more than 95 % of the countries in their sample (including 15 African countries) reported that they had granted various tax exemptions for the foreign aid they received. The estimated tax revenue foregone as a result of aid-related exemptions in most African countries ranges from 1% to 2% of GDP, with the figure being 3% of GDP for Rwanda, Mozambique, and Malawi. For Liberia, one of the most aid-dependent countries on the continent, tax revenue foregone due to aid-related exemptions was as high as 7.5% of the country’s GDP in 2016. The main rationale for aid-related tax exemptions is that taxing aid will reduce the value of aid. However, tax collected on aid-related projects contributes to the national budgets of recipient countries. Therefore, tax exemptions of this nature may contribute to a weakening of the state’s tax collection capacity.

Project aid represents about 70% of all ODAs in most developing countries, and recipient countries need to negotiate tax exemptions for each project. As a result, over and above the state���s revenue losses, tax exemptions significantly increase the workload of the tax and customs administrations in the recipient countries. Furthermore, aid-related tax exemptions can also undermine the perception of fairness in the tax system in recipient countries, while at the same time reducing the tax bases and creating economic distortions. Local suppliers in aid-recipient countries often have to compete with tax-exempted products and services financed by aid projects. This is more problematic when aid is tied���where funds are used for the procurement of goods and services from donor counties, limiting the development of local firms in recipient countries. Although progress has been made in untying more aid in recent years, about 15% of donors��� total bilateral commitments in 2019 were reported as tied aid, with some countries reporting 40% to 70% of their aid as tied.

The current pandemic demonstrates the critical need to strengthen public systems in order to meet basic needs, such as health and food security in developing countries. However, instead of significantly tackling tax issues that limit domestic resource mobilization efforts in developing countries and strengthen their public systems, there is growing pressure to use ODA funds to subsidize private sector involvement through blended financing to finance SDGs. Without improving the capacity of African countries to effectively tax private companies, the use of ODA to subsidize private sectors may lead to additional tax avoidance and evasion by shifting profits to tax havens while increasing debt burdens.

February 1, 2021

The Pearl of the Indian Ocean

Image credit Stuart Price for UN Photo via Flickr CC.

Image credit Stuart Price for UN Photo via Flickr CC. January 26, 2021 marked 30 years since the capture of Mogadishu by opposition forces and their overthrow of the pre-war government at the dawn of Somalia���s civil war. Decades of conflict have left innumerable visible and unseen scars on the city and its inhabitants. An ancient African city once known as the ���Pearl of the Indian Ocean,��� Mogadishu was previously a prosperous part of the many sultanates that burgeoned along the coast of East Africa. Also known as Xamar, for a millennium, the city���s openness, ordinary cosmopolitanism, and lure of opportunities have attracted people from the Somali hinterland and beyond.

Migrants from across the Middle East, particularly southern Yemen, and South Asia added to the cultural richness and unique allure of Mogadishu that distinguished it from other East African cities. Some of those migrants brought with them architectural gifts in the shape of cylindrical minarets that resemble those one may see in Persian cities complimented by the local, white coral stone buildings that dominate the coast of East Africa.

The Ithna Asheri Mosque is one of Muqdisho���s oldest examples of Shi���a Persian architecture and is in the old city of Xamar Weyne. No longer in use as a mosque, it���s now a home for internally displaced families who have fled conflict in other parts of southern Somalia. Credit: Jabril Abdullahi.

The Ithna Asheri Mosque is one of Muqdisho���s oldest examples of Shi���a Persian architecture and is in the old city of Xamar Weyne. No longer in use as a mosque, it���s now a home for internally displaced families who have fled conflict in other parts of southern Somalia. Credit: Jabril Abdullahi.At their height between the 13th and 16th centuries, Arab and Portuguese chroniclers described the cities of the Benadir Coast, particularly Mogadishu, as affluent and powerful centers of trade. In modern times, Mogadishu was occupied by the Italians who colonized southern Somalia during the ���scramble for Africa��� in the late 19th century.

During the golden age of Somali music in the 1970s and 1980s, Mogadishu was renowned as the region���s pre-eminent cultural hub given its roaring nightlife and thriving arts scene. Among many others, this milieu gave rise to the enchanting melodies of the Waaberi and Dur-Dur bands, which were carried to airwaves and audiences near and far. Packed nightly concerts would symbolically unite leisure-seeking Somalis from all walks of life at the iconic Al-Uruba Hotel and other reputed establishments in the old city of Xamar Weyne.

Those histories live not only in the collective memory of Mogadishu���s people but also are edged into the architecture of those bygone eras, especially in the old quarters of Xamar Weyne and Shangani. Pre-war Mogadishu was a diverse city characterized by a confident openness to the world. Two decades of civil war and ongoing insecurity reduced large swathes of the city to rubble and made Mogadishu synonymous with anarchy. However, the delicate stability of the past decade and progress in reconstruction have made life in the city more accommodating for its inhabitants and more attractive to others, including those who once called it home.

Liido Beach on a Saturday afternoon. Credit: Mohamed Duale. A tale of four cities

Liido Beach on a Saturday afternoon. Credit: Mohamed Duale. A tale of four cities Mogadishu, as many of its residents will tell you, is a city of contrasts marked by deepening spatialized inequality as seen by the emergence of four socio-economic sub-cities. There is City 1 in Xalane, the secure ���green zone��� near the airport where the diplomatic, peacekeeping, and humanitarian missions are headquartered. This is a city unto itself, where only a select few may visit or live for security reasons. City 2 is the ���Xamar Cadey��� (Xamar the Beautiful) of gleaming new hotels, and comfortable condos and villas next to an increasing array of shopping malls and souks. This is the breezy city of world class beaches and excellent restaurants serving Italian dishes given a Somali rendition. Then there is City 3, the numerous neighborhoods with difficult living conditions and where the working and lower classes of Mogadishu reside. And further still, there is City 4, the sprawling internally displaced persons (IDP) camps on the outskirts of town where nearly one million IDPs, mostly from the riverine regions of southern Somalia, live. Connecting these four cities within Xamar is a network of roads, sometimes surrounded by blast-proof concrete walls and often plagued by heavy traffic, security closures, and violent attacks.

Dabka neighborhood, between Waaberi and Hodan districts. Credit: Mohamed Duale. Anxieties in an emerging post-conflict city

Dabka neighborhood, between Waaberi and Hodan districts. Credit: Mohamed Duale. Anxieties in an emerging post-conflict city Though many often use the term ���post-conflict��� to refer to the current juncture, the actual socio-political situation in Mogadishu is one of an emerging post-conflict context. For one thing, residents continue to live with insecurity as a result of local, regional, and global contestations over the fate of the city and the country. Sometimes, this creates considerable anxiety not only about one���s personal safety given regular incidence of violence, but also about the ambiguities of a shifting political situation. As a result of clan-based internal regionalization, an incipient question has been whether Mogadishu should be part of a regional state. Other salient questions relate to issues of class and culture. As thousands of diaspora Somalis have returned to the city in recent years, those who have stayed during the civil war have begun to resent their political and economic domination and third culture. The sizeable urban poor also feel left out of the prosperity of City 2, not least by the rising cost of living, and sometimes wonder: whose Mogadishu is it anyway? Moreover, the frantic rebuilding of the last decade has hurt the city���s fragile architectural inheritance, with the demolition of historically significant structures in the old quarters and the construction of a mishmash of taller buildings and shopping centers in their place���a trend that has concerned many. If Somalis want to sustain momentum in national reconstruction, economic development will need to be balanced with careful efforts to build a socially just and durable peace, which includes the upkeep of tangible links to Somalia���s long history.

Resurfacing opennessThroughout the civil war of the 1990s, Mogadishu was divided by a ���green line,��� which separated the south and north of the city. It was the scene of fratricidal clan-based violence that killed and displaced untold thousands and destroyed much of the city���s infrastructure and distinctive openness. In the late 2000s, most of Xamar���s inhabitants fled a brutal Ethiopian occupation that indiscriminately bombarded the city. Since then, Mogadishu has risen from the proverbial ashes of destruction from decades of war. Within the city, you will find people from every region of the Somali territories of the Horn of Africa as well as from the large Somali diaspora. You can hear young people in caf��s speaking different accents and dialects of Somali as well as English, Swedish, Dutch, French, Arabic, and many other languages. In addition, many Somali refugees living in neighboring countries have recently resettled in Mogadishu. As in the past, the city is receiving a small but growing number of refugees from the Middle East���Syria and Yemen, for example���and migrants from parts of South Asia (Bangladesh) and East Africa (Kenya). Today, Xamar is slowly re-emerging as an important commercial center, as well as a meeting place of people, cultures, and ideas in the wider region. Nevertheless, this resurfacing openness is not, as mentioned, without challenges, ambiguities, and anxieties. As an emerging post-conflict city, Mogadishu will need continued dialogue, openness, and hospitality if it is to once more be the ���Pearl of the Indian Ocean.���

January 29, 2021

Israel’s Africa strategy

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash While the world applauds Israel for its ���swift��� vaccine roll-out, not only does the apartheid-state continue to deny responsibility for vaccinating Palestinians, it continues to subject them to utter brutality���in the midst of global pandemic, Israel is still issuing orders for demolitions in the West Bank, and this week ordered the demolition of a local clinic in Hebron. Over in Gaza, Israel���s illegal land, air and sea blockade of the strip enters its fourteenth year, with its two million residents experiencing the heft of an economic and health crisis, collapsing infrastructure, routine power outages, and the constant threat of Israeli airstrikes.

It���s been a year since former US president Donald Trump unveiled his infamous peace plan. The so called ���deal of the century��� was anything but a deal with Palestinians completely excluded from its conception and drafting. While Joe Biden���s administration might reverse the deal, we are unlikely to see the United States depart from its long-standing, pro-Israel stance���vice-president Kamala Harris confirmed last year that the ���Biden-Harris administration will sustain our unbreakable commitment to Israel���s security.���

Whatever happens though, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (aided by Trump) has recently focused his energies on acquiring legitimacy from beyond Washington. In the second half of 2020, Israel partially or fully restored diplomatic ties with the UAE and Bahrain in the Middle East, as well as Sudan and Morocco in Africa. Despite Trump���s exit, Israel���s campaign for normalization is not finished yet, and Africa has always been of particular interest to it for obvious reasons. As Netanyahu told Israeli ambassadors to Africa in 2017:

The automatic majority against Israel at the UN is composed���first and foremost���of African countries. There are 54 countries. If you change the voting pattern of a majority of them you at once bring them from one side to the other. You have changed the balance of votes against us at the UN and the day is not far off when we will have a majority there.

This week on AIAC Talk, we���ll be joined by Yotam Gidron and Matshidiso Motsoeneng to discuss Israel���s scramble for Africa. Yotam is a PhD student in African History at Durham University, and recently authored Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics (2020). We���d like to ask Yotam, why is Israel in Africa? As Yotam clarifies, Israel���s presence on the continent is not just a recent phenomenon������Throughout history, Israeli politicians and pro-Israel organizations and actors saw Israel���s involvement in Africa as a means for reshaping the international narrative around the situation in Israel/Palestine and countering criticism of Israel as a settler-colonial, discriminatory state.��� What is this history, and how can it help us understand present circumstances?

What is especially important to grapple with then, is what this all means for African-Palestinian solidarity. Where Africa was once a reliable supporter of anticolonial resistance everywhere, the economic hardships wrought by a stagnating capitalism, combined with the growing influence of Christian Zionism, have pushed states and citizens closer and closer to Israel. We want to ask Matshidiso, an activist and researcher based at the Afro-Middle East Centre in Johannesburg, what this landscape means for the global movement towards boycotts, divestment and sanctions against Israel. Will South Africa, whose own experience of apartheid makes it more supportive of the Palestinian struggle, have to go it alone on the continent? Is support there also fading?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we spoke to Ant��nio Tom��s and Ricci Shryock about the life, legacy and thought of�� Am��lcar Cabral. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

Israel’s African strategy

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash While the world applauds Israel for its ���swift��� vaccine roll-out, not only does the apartheid-state continue to deny responsibility for vaccinating Palestinians, it continues to subject them to utter brutality���in the midst of global pandemic, Israel is still issuing orders for demolitions in the West Bank, and this week ordered the demolition of a local clinic in Hebron. Over in Gaza, Israel���s illegal land, air and sea blockade of the strip enters its fourteenth year, with its two million residents experiencing the heft of an economic and health crisis, collapsing infrastructure, routine power outages, and the constant threat of Israeli airstrikes.

It���s been a year since former US president Donald Trump unveiled his infamous peace plan. The so called ���deal of the century��� was anything but a deal with Palestinians completely excluded from its conception and drafting. While Joe Biden���s administration might reverse the deal, we are unlikely to see the United States depart from its long-standing, pro-Israel stance���vice-president Kamala Harris confirmed last year that the ���Biden-Harris administration will sustain our unbreakable commitment to Israel���s security.���

Whatever happens though, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (aided by Trump) has recently focused his energies on acquiring legitimacy from beyond Washington. In the second half of 2020, Israel partially or fully restored diplomatic ties with the UAE and Bahrain in the Middle East, as well as Sudan and Morocco in Africa. Despite Trump���s exit, Israel���s campaign for normalization is not finished yet, and Africa has always been of particular interest to it for obvious reasons. As Netanyahu told Israeli ambassadors to Africa in 2017:

The automatic majority against Israel at the UN is composed���first and foremost���of African countries. There are 54 countries. If you change the voting pattern of a majority of them you at once bring them from one side to the other. You have changed the balance of votes against us at the UN and the day is not far off when we will have a majority there.

This week on AIAC Talk, we���ll be joined by Yotam Gidron and Matshidiso Motsoeneng to discuss Israel���s scramble for Africa. Yotam is a PhD student in African History at Durham University, and recently authored Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics (2020). We���d like to ask Yotam, why is Israel in Africa? As Yotam clarifies, Israel���s presence on the continent is not just a recent phenomenon������Throughout history, Israeli politicians and pro-Israel organizations and actors saw Israel���s involvement in Africa as a means for reshaping the international narrative around the situation in Israel/Palestine and countering criticism of Israel as a settler-colonial, discriminatory state.��� What is this history, and how can it help us understand present circumstances?

What is especially important to grapple with then, is what this all means for African-Palestinian solidarity. Where Africa was once a reliable supporter of anticolonial resistance everywhere, the economic hardships wrought by a stagnating capitalism, combined with the growing influence of Christian Zionism, have pushed states and citizens closer and closer to Israel. We want to ask Matshidiso, an activist and researcher based at the Afro-Middle East Centre in Johannesburg, what this landscape means for the global movement towards boycotts, divestment and sanctions against Israel. Will South Africa, whose own experience of apartheid makes it more supportive of the Palestinian struggle, have to go it alone on the continent? Is support there also fading?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we spoke to Ant��nio Tom��s and Ricci Shryock about the life, legacy and thought of�� Am��lcar Cabral. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

On Israel’s strategy in Africa

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash While the world applauds Israel for its ���swift��� vaccine roll-out, not only does the apartheid-state continue to deny responsibility for vaccinating Palestinians, it continues to subject them to utter brutality���in the midst of global pandemic, Israel is still issuing orders for demolitions in the West Bank, and this week ordered the demolition of a local clinic in Hebron. Over in Gaza, Israel���s illegal land, air and sea blockade of the strip enters its fourteenth year, with its two million residents experiencing the heft of an economic and health crisis, collapsing infrastructure, routine power outages, and the constant threat of Israeli airstrikes.

It���s been a year since former US president Donald Trump unveiled his infamous peace plan. The so called ���deal of the century��� was anything but a deal, with Palestinians completely excluded from its conception and drafting. While Joe Biden���s administration might reverse the deal, we are unlikely to see the United States depart from its long-standing, pro-Israel stance���vice-president Kamala Harris confirmed last year that the ���Biden-Harris administration will sustain our unbreakable commitment to Israel���s security.���

Whatever happens though, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (aided by Trump) has recently focused his energies on acquiring legitimacy from beyond Washington. In the second half of 2020, Israel partially or fully restored diplomatic ties with the UAE and Bahrain in the Middle East, as well as Sudan and Morocco in Africa. Despite Trump���s exit, Israel���s campaign for normalization is not finished yet, and Africa has always been of particular interest to it for obvious reasons. As Netanyahu told Israeli ambassadors to Africa in 2017:

The automatic majority against Israel at the UN is composed���first and foremost���of African countries. There are 54 countries. If you change the voting pattern of a majority of them you at once bring them from one side to the other. You have changed the balance of votes against us at the UN and the day is not far off when we will have a majority there.

This week on AIAC Talk, we���ll be joined by Yotam Gidron and Matshidiso Motsoeneng to discuss Israel���s scramble for Africa. Yotam is a PhD student in African History at Durham University, and recently authored Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics (2020). We���d like to ask Yotam, why is Israel in Africa? As Yotam clarifies, Israel���s presence on the continent is not just a recent phenomenon������Throughout history, Israeli politicians and pro-Israel organizations and actors saw Israel���s involvement in Africa as a means for reshaping the international narrative around the situation in Israel/Palestine and countering criticism of Israel as a settler-colonial, discriminatory state.��� What is this history, and how can it help us understand present circumstances?

What is especially important to grapple with then, is what this all means for African-Palestinian solidarity. Where Africa was once a reliable supporter of anticolonial resistance everywhere, the economic hardships wrought by a stagnating capitalism, combined with the growing influence of Christian Zionism, have pushed states and citizens closer and closer to Israel. We want to ask Matshidiso, an activist and researcher based at the Afro-Middle East Centre in Johannesburg, what this landscape means for the global movement towards boycotts, divestment and sanctions against Israel. Will South Africa, whose own experience of apartheid makes it more supportive of the Palestinian struggle, have to go it alone on the continent? Is support there also fading?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 SAST, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we spoke to Ant��nio Tom��s and Ricci Shryock about the life, legacy and thought of�� Am��lcar Cabral. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

January 28, 2021

How Indian cinema shaped East Africa���s urban culture

Photo by Brian McGowan on Unsplash

Photo by Brian McGowan on Unsplash East-African Asian influence on cinema culture in the region is not often recognized, even as Indian movies shaped landscapes, fashion, popular images, and music genres over decades. From Nairobi to Kampala to Zanzibar, Indian films transmitted knowledge and united families, and offered many dreams and escapes, especially during the 60s, 70s and 80s, a period considered the golden age of Indian cinema culture in the region.

This article is part of a series where we republish selected articles from The Elephant. The series is curated by Africa Is a Country editorial board member, Wangui Kimari.

At a time when ���social distancing��� is becoming the norm due to the coronavirus pandemic, it may appear self-indulgent to reminisce about a period when going to the cinema was a regular feature of East African Asians��� lives. But perhaps now that the world is changing���and many more people are watching movies at home on Netflix and other channels���it is important to document the things that have been lost in the war against COVID-19 and with the advent of technology. One of these things is the thrill of going to the cinema with the family.

What has also been lost is an urban culture embedded in East Africa���s South Asian community���a culture where movie-going was an integral part of the social fabric of this economically successful minority.

Those who pass the notorious Globe Cinema roundabout, which is often associated with pickpockets and street children, might be surprised to learn that the Globe Cinema (which no longer shows films but is used for other purposes, such as church prayer meetings) was once��the place to be seen on a Sunday evening among Nairobi���s Asian community. I remember that cinema well because in the 1970s my family used to go there to watch the latest Indian���or to be more specific, Hindi (India also produces films in regional languages like Telegu, Bengali and Punjabi) blockbuster at 6pm on Sundays. Sunday was movie day in my family, and going to the cinema was a ritual we all looked forward to. The Globe Cinema was considered one of the more ���posh��� cinemas in Nairobi; not only was it more luxurious than the others, but it also had better acoustics.

As veteran journalist Kul Bhushan writes in a recent edition of��Awaaz��magazine (which is dedicated entirely to Indian cinema in East Africa from the early 1900s to the 1980s), ���Perched on a hillock overlooking the Ngara roundabout, the Globe became the first choice for cinemagoers for new [Indian] releases as it became the venue to ogle and be ogled by the old and the young.���

Indian movies were���and are���the primary source of knowledge about Indian culture among East Africa���s Asian community. The early Indian migrants had little contact with the motherland, as trips back home were not only expensive but the sea voyage from Mombasa to Bombay or Karachi took weeks. (At independence in 1947, the Indian subcontinent became two countries���India and Pakistan���hence the reference to Indians in East Africa as ���Asians.���) So they relied on Indian films to learn about the customs and traditions of the country they or their ancestors had left behind.

Exposure to Indian languages and culture through films was one way Indians abroad or in the diaspora retained their identity and got to learn about their traditions and customs. I got to learn about the spring festival of Holi and goddesses such as Durga from watching Indian films. I also learnt Hindi, or rather Hindustani���a mix of Hindi (which is Sanskrit-based) and Urdu (which is also Sanskrit-based but which borrows heavily from Persian and Arabic)���which is the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, and which is the language most commonly used in the so-called Hindi cinema.

On the other hand, the sexist culture portrayed in the majority of Indian films also reinforced sexual discrimination among East African Asians. The idea that women are subservient to men, and that it is the woman who must sacrifice her own needs and desires for the ���greater good��� of the family/community, were���and still are���dominant in Indian cinema. Love stories portrayed in films���where young lovebirds defy societal expectations and cross class, religion or caste barriers���were not supposed to be emulated; they were considered pure entertainment and not reflective of a society where arranged marriages were and still are the norm. I heard many stories of how if an Asian woman dared to cross racial, religious, or caste barriers she was severely reprimanded or stigmatized.

Watching Indian movies was also one way of keeping up with the latest fashions. Men and women often tried to copy the hairstyles and clothes of their favorite movie stars. When the hugely successful film��Bobby��was released in 1973, many girls adopted the hairstyle of the lead actress (who was barely 16 when she starred in the film) Dimple Kapadia. (I used to have a blouse at that time that was a replica of the one the actress wore in the film.) When the famous film star Sharmila Tagore dared to wear a revealing swimsuit in the 1967 film��An Evening in Paris, she opened the door for many Indian women to go swimming without covering themselves fully.

Since music often defined the success of a film, top playback singers, such as Lata Mangeshkar, Kishore Kumar and Muhammad Rafi, were held in high regard, and people flocked to watch their live concerts in Nairobi. Wealth and opulence were in full display at these events.

The golden ageThe 60s, 70s and 80s are often described as the Golden Age of Indian/Hindi cinema. Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu, where there were large concentrations of Asians, had many cinemas devoted to showing films made in Bombay (now Mumbai)���often referred to as Bollywood. This was the time when actors and actresses like Rajesh Khanna, Hema Malini, Amitabh Bachchan and Sridevi became superstars.

Cinemas in Nairobi were always full, especially on weekends when Asian families flocked to the dome-like Shan in Ngara, to Liberty in Pangani, or to the Odeon or the Embassy in the city centre. (except for Shan cinema, all the others are no longer cinema halls but are used for other purposes. Shan was rescued from decrepitude by the Sarakasi Trust, which changed its name to The Dome; it is now used for cultural activities.) Over the years, an increasing number of Africans began watching Indian films. Oyunga Pala, the chief curator at��The Elephant,��recalls going to the Tivoli cinema in Kisumu, where he first got to see Amitabh Bachchan in action.

���Right next to the Liberty Cinema was situated the clinic of a very popular Indian doctor,��� recalls Neera Kapur-Dromson in an article published in the Indian cinema edition of��Awaaz. ���The small waiting room was always crammed with patients. But that never deterred him from taking ample breaks to enjoy a few scenes of the film being screened ������

But for Asian teenage girls and boys in Nairobi, the place to be seen on a Sunday evening was the Belle Vue Drive-In cinema on Mombasa Road. Young Asian men would show off their (fathers���) cars and young women would display the latest fashions���all in the hope of catching the attention of a potential mate. Food was shared���and sometimes even cooked���on the gentle slopes of the parking spots. Going to the Drive-In was like going for a picnic. And as the lights dimmed, the large bulky speakers were put on full volume so that everyone (usually father, mother, and three or four kids in the back seat) in the car���and beside it���could hear the dialogues. Fox Drive-In cinema on Thika Road was also a popular joint, but mainly with the younger crowd who preferred watching the Hollywood movies which were a regular feature there.

It was the same in Kampala. Vali Jamal, recalling his youthful days in Uganda���s capital city, says that the Sunday outing to the Drive-In was the only time there was a traffic jam in Kampala. ���Idi Amin got caught in one of them, driving back to Entebbe with his foreign minister Wanume Kibedi,��� he writes. ������Where are we?��� quoth the president, ���In Bombay?��� And the expulsion happened.���

He continues: ���Well, let me not exaggerate, but South Asian wealth was on display on the Sundays accompanied by their notions of exclusion, and let us not forget that those two variables���income inequality and racial arrogance���figured heavily in Amin���s decision to expel us.��� (In August 1972, President Idi Amin expelled more than 70,000 Asians from Uganda.)

Urban conversationsIn her book,��Reel Pleasures:��Cinema Audiences and Entrepreneurs in Twentieth Century Urban Tanzania, Laura Fair describes how the Sunday evening shows became a focal point of urban conversations among Tanzania���s Asian community. They were meeting points, like temples, mosques or churches, where people sought affirmation.

As in Kenya, Sunday shows in Tanzania were family and community bonding events. ���Cinema halls were not lifeless chunks of brick and mortar; they resonated with soul and spirit. They were places that gave individual lives meaning, spaces that gave a town emotional life. Across generations, cinemas were central to community formation,��� says the author. Indian cinema thus played an integral role in the social lives of the South Asian community in East Africa.

It all started in the 1920s when Mohanlal Kala Savani, a textile trader, imported a hand-cranked projector and began showing silent Indian films in a rented warehouse in the coastal town of Mombasa. In 1931, when two brothers, Janmohamed Hasham and Valli Hasham, built the Regal Cinema, he began renting the venue to show Hindi films. Two years later, he built his own 700-seat Majestic Cinema in Mombasa, which showed Indian films and also hosted live shows.

The late Mohanlal Savani was a man of vision, recalls his son Manu Savani in an article chronicling how his father expanded movie-viewing in East Africa. ���As time progressed Majestic became an established cinema on the Kenyan coast. The owners of Majestic also became fully fledged film distributors with links stretching, to start with, to Uganda and [what was then known as] Tanganyika.���

Famous Indian movie stars began gracing these cinemas in order to increase their fan following. Notable among these were the legendary Dilip Kumar, a 1950s heartthrob whose portrayal of jilted lovers set many a heart fluttering, and Asha Parekh, who made her name in tragic love stories such as��Kati Patang.��

Indian cinema had wide appeal not just in Kenya, but also in neighboring Zanzibar, where the urban night life was dominated by Indian movies. Many a��taraab��tune came directly from the hit songs of Indian movies. As opposed to Western movies (often referred to as English movies), Indian films appealed to Swahili sensibilities, with their focus on values such as modesty, respect for elders and morality.

In Zanzibar, Lamu and other coastal areas where segregation between the sexes was strictly observed, there were special��zenana��(women-only) shows, where women dressed up in their finest to join other women in watching Indian and Egyptian films. For many Asian and Swahili women, the��zenana��afternoon show was a rare opportunity to leave their cloistered existence and let their hair down, and also to meet up with friends outside the confines of their homes. (I once went to a women-only show at Nairobi���s Shan cinema on a Wednesday afternoon with my grandmother when I was about eight or nine years old and I can tell you there was less movie-watching and more talking and gossiping going on during the show.)

Unfortunately, the old cinemas in Zanzibar are no more, which is surprising because the island is host to the Zanzibar International Film Festival. Cine Afrique, the only standing cinema in Zanzibar when I visited the island in 2003, was a pale shadow of its former shelf, with its cracked ceiling and broken seats. I believe it has now been demolished to pave way for a mall. The Empire, another famous cinema on the island, is now a supermarket and the once impressive Royal Cinema is in an advanced stage of decay.

The decline of the movie theaterThere are many reasons for the decline of Indian movie theater in East Africa, among them piracy, declining South Asian populations and technologies that allow people to watch movies from the comfort of their homes. The introduction of multiplex cinemas in shopping malls has also lessened the appeal of a stand-alone cinemas, and made movie-going less of an ���event��� and more of something that can be done while doing other things.

Indian cinema has also evolved. Unrequited love, family dramas, good versus evil and the ���angry young man��� genre popularized by Amitabh Bachchan���constant themes in the ���masala��� Indian films of the 70s and 80s���have been replaced by more sophisticated and nuanced plots, perhaps in response to a large Indian diaspora in the West which is more interested in plots that are more realistic and reflective of their own lives. The escapism of the Indian cinema of yesteryear has given way to realism, which makes cinema-going less ���entertaining���.

Indian actors and actresses are also getting more roles in films made in Hollywood, and American and British films are increasingly finding India to be an interesting backdrop or subject for their movies, as evidenced by the huge success of films like��Slumdog Millionaire. This has expanded the scope and definition of what constitutes an ���Indian movie.���

Some would say that Indian cinema has actually deteriorated, with its emphasis on semi-pornographic dance routines and plots revolving around upper class people and their angst. So-called ���art cinema��� produced by award-winning directors like Satyajit Ray and Shyam Benegal, which portrays the lives of the downtrodden and addresses important social issues, or distinctly feminist films like��Parama��(directed by Aparna Sen), which explores the inner worlds of Indian women, are few and far between.

But as any Indian movie buff will tell you (and I include myself in this group), the experience of watching an Indian film in a cinema cannot be matched on a TV or computer screen. Indian cinema in its heyday was a feast for the eyes. If you wanted to enter the magical world of Indian cinema, complete with elaborate and well-choreographed dances, heart-stirring music and emotion, you saw Indian films in a movie theater.

Alas, those days are fast disappearing thanks to terrorism, technology and now COVID-19. And along with this, a distinctly East African urban culture has been lost forever.

The death of an exceptional woman

Sizani Ngubane. Courtesy of Martin Ennals Award.

Sizani Ngubane. Courtesy of Martin Ennals Award. Confirmation of the death at age 74 of Sizani Ngubane���the world-renowned activist for the rights of rural women���on December 23, 2020, sent shock waves through her extensive South African and international networks. When the announcement was made, she had been dead for perhaps a week or more, having suffered a tormented COVID-19 death alone in her Hilton, KwaZulu-Natal home. Fingers are now being pointed at the provincial Department of Health and the local police for their failure to respond to the barrage of pleas from her son, Thulani, who was at the time himself hospitalized seriously ill with COVID-19.

At the end of November, Sizani began showing symptoms of what appeared to be COVID-19.�� On December 3, her son took her to Boom Street Clinic in Pietermaritzburg where, after waiting for a few hours, they were tested. Thulani, who had also developed COVID-19 symptoms, dropped her off at her home in Hilton and returned to his own home at Imbali township in Pietermaritzburg. On December 5, he was notified that he had tested positive. He was worried about his mother but when he tried to call, he could not get through. Thulani���s symptoms worsened and on December 7 he was contacted by a nurse at the Boom Street clinic, who advised that an ambulance would be sent to take him to a local hospital. He pleaded with the nurse to arrange tracking and treatment for his mother who was still at her Hilton home. Thulani waited another three days for the ambulance to arrive to take him to hospital (he complains bitterly about the attendants unhelpful conduct, demanding that he walk to meet them despite the fact he was battling to breath). He was eventually transferred to a facility in Richmond, a town 60km south, where he spent 10 days being treated and quarantined.

On December 14, Thulani again called the clinic and spoke to the same nurse D, asking her what had happened to his mother. She said she would call him back, but he never heard from her. On the same day he also called the Hilton SAPS and asked them to check on his mother. It appears that no proper check was carried out by the SAPS.

Thulani was released from Richmond hospital on December 20 and after arriving home early evening, exhausted, he slept through the whole of Sunday. On December 22, he went to his mother���s Hilton home together with his 23-year-old son, who had been writing exams. They made a gruesome discovery���Sizani���s naked body, in a state of decomposition, on the sofa. There was no sign of forced entry or theft, so there is little doubt that she died alone, an agonizing death from high fever and delirium. When they reported to the Hilton SAPS detachment, the death was recorded as having happened that day, despite clear indications that Sizani had been dead for some time. A series of alleged delays and corruptions by the police, the medical examiner, and the Department of Home Affairs added to the trauma the family experienced in their efforts to finalize a death certificate and funeral arrangements.

The failure of the SAPS to respond to Thulani���s urgent call to do a wellness check on December 14 is currently under investigation by his lawyer. The conduct of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health raises serious questions about its response when people test positive for COVID-19. Sizani���s death suggests it is a futile exercise, since there was no real effort, it seems, to track an elderly woman who tested positive, despite the attempts by her seriously ill son to get a response. Sizani was simply left to die.

Her death leaves a void in her brainchild, the Rural Women���s Movement. A member of the National Women���s Coalition and active in the Association for Rural Advancement in Pietermaritzburg in the 1990s, Sizani was determined to empower rural women in KwaZulu-Natal. In the early 2000s she registered the movement and conducted outreach to the furthest corners of the province.

The Rural Women���s Movement played, and continues to play, an important role in advancing the legal rights of rural women. It made a significant contribution to the 2010 striking down of the Communal Land Rights Act of 2004 by the Constitutional Court, one of the arguments being that the legislation was passed without due input from rural residents. The Rural Women���s Movement, and a number of its members, are also applicants in the pending High Court case against the Ingonyama Trust, its Board, ministers, and others, relating to the imposition of leases by the Trust, and rents to be paid by the rural poor. Tragically, Sizani did not live to see the outcome of this important case.

Through her vision and hard work Sizani was able to obtain support for her work from funders. Many people came from around the world to work with her and learn from her. In 2020 she was among those honored with an award by the Martin Ennals Foundation, a Swiss human rights group, for her achievements in protecting the rights of women.

Her death leaves a leadership vacuum in the Rural Women���s Movement, which must now be filled so that the crucial work continues and expands. In an interview some years before her death, she spoke of her dream to set up a place of healing for abused women. The legacy of distorted customary law in Kwazulu-Natal and the recent passing of the two draconian ���Bantustan Bills��� means it is critical that the dedication and fighting spirit of Sizani Ngubane lives on.

January 27, 2021

The afterlives of indenture

'The look you gave me made flowers grow in my ...' (2020) Alka Dass.

'The look you gave me made flowers grow in my ...' (2020) Alka Dass. This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows. Funded by Shuttleworth Foundation, our fellows produce original work. They represent a diversity of regions, backgrounds and are each exploring exciting ideas related to politics, culture, sports or social movements. Siddhartha Mitter is our mentorship coordinator. Our mentors are Aida Alami, Beno��t Challand, Grieve Chelwa, Sean Jacobs, Marissa Moorman, Sisonke Msimang, and Bhakti Shringarpure. Caitlin Chandler prepares the pieces for publication.

The first time I remember seeing Muruganlakshmi was at the Shree Siva Subramaniar Alayam in Verulam, a town outside the bustling city of Durban. The Drift temple, as the locals call it, is my family���s temple of choice. Our Kavady festivals and weddings take place close to the Umdhloti riverbank. When I was younger the temple was quiet, with the smell of agarbathi filtering onto the street but now, a highway runs right by the temple���and the priest���s invocations fight with long-haul truck horns and aircrafts at the nearby King Shaka airport.

That day, Muruganlakshmi, whose name I have changed to protect her identity, would have sat in the front of the congregation where she was always stationed. She had a long salt and pepper plait and her signature look for Sunday prayer service was a teal chiffon sari. She sang tevarams loudly, teasing out the notes in each ancient praise song from the harmonium at her feet. For more than thirty years, she was Verulam���s go-to harmonium player, making music for at least six different prayer groups well into her 80s.

I grew up in White River, a town almost eight hours away by car, but would often visit Verulam to see family. I enrolled in a masters program in political studies in 2017, and when it was time to pick a thesis topic, I thought back to my childhood.�� My project was on domestic violence and spirituality, and I had heard that Muruganlakshmi had some stories to tell.

When we first sat down for our interview in her kitchen, Muruganlakshmi was forthright and direct with me. I was young enough to be her grand-daughter and she told me:

You know my uncle was in a band? He liked my singing so when he used to go to functions, he called me to sing. My uncle used to play the harmonium but he didn���t teach me. No, nobody taught me. You match it, you match the singing when you play it now. My notes���I will just know. That���s what I am doing in the temple. I look in front. The guru is doing the prayer but I will be playing away for them. I can play without looking. I think of it as a special gift, but yet I had such a terrible, dramatic marriage.

Pumla Gqola, the author of Rape: A South African Nightmare, has argued that South Africans often feign horror when it comes to rape and sexual violence.�� She wonders what it means to be horrified by violence against women when it is in the headlines, as opposed to accepting the reality that women in South Africa are subjected to violence every day. Gqola asks us to think about the quotidian affectual undercurrents of sexual violence and forces us to think about how we care and are careless with each other. She insists that we reckon with memory.

South African Indian families are deeply invested in the avoidance of shame, or as Gqola would put it, in feigning horror. There are things we don���t talk about, memories we would rather bury than speak out loud. But memories don���t die, they rise like specters and haunt the living.

‘Blue sari’ (2020) Alka Dass.

‘Blue sari’ (2020) Alka Dass.Muruganlakshmi���s story answered questions I had not allowed myself to ask. When I began speaking to her in 2017, it became obvious that as I was also the descendant of indentured laborers, I was shaped by the afterlives of this system in ways I cannot yet name. Indeed, in the absence of collective naming, it has been impossible to address our problems.

Patriarchal violence is spoken of in whispers across kitchen tables and normalized as part of a woman���s burden. KwaZulu-Natal���s Premier, Sihle Zikalala, announced last year that the province is one of the country���s epicenters of gender-based violence. Verulam consistently places in sexual crime hotspots in City of Ethekwini statistics. Last year���s South African Police Service crime statistics showed that Phoenix���an area also shaped through displaced South Asian workers and adjacent to Verulam, was a national hotspot for sexual offences (namely sexual assault). Trauma is carried from one generation to the next and women���s memories of assault���and Muruganlakshmi���s in particular���can help my community to navigate contemporary violence.

Muruganlakshmi was born in 1937 in the KwaZulu Natal Midlands, an area known for its dairy farming. Her father���s family were farm workers. It was common practice for indentured laborers to receive a plot of land for subsistence farming, once their indentured contracts were up.

Her family had been part of a great forced migration from South Asia to Africa, part of the history of Colonial Natal, which prospered on sugarcane and used, primarily, Indian labor to cultivate the land. European farmers dispossessed local Zulu people of arable land but believed that they were self-sufficient and unreliable in the fields.

They decided to recruit a migrant worker population they could control, and whose only function was to serve the interests of the burgeoning sugar industry. An important subtext to indentured labor was the absence of family or kinship connections���the ability of a labor force to work without the physical entanglements of home and community was a key selling point.

A small group of European sugarcane planters decided to apply to the British government to bring Indian laborers to make the sugar industry in Colonial Natal. There was some disapproval of the move by the settlers, as they feared being even more outnumbered by ���natives and coolies������but the capital incentive was too enticing, and the British and Indian governments entered into an agreement which saw waves of indentured laborers coming to South Africa from 1860 to 1911.

Gender imbalances were stark in the beginning of the indentured labor migration���more men than women boarded the ships as men were valued more as plantation laborers. Men received rations, and over time women began to receive half rations, but to colonial officials, Indian women were collateral to the indenture system.

When Muruganlakshmi was 17, she got married.�� Her husband was abusive. In the early 1960s, Muruganlakshmi remembers jumping from her window���two stories up���onto a flight of stairs and fracturing her hip.�� She was escaping her husband at the time, who threatened to burn her with their paraffin stove.

He was a notorious alcoholic but ���when he was sober, he was very good, generous and caring for people,��� Muruganlakshmi said. ���Except for me,��� she added.

Muruganlakshmi may not have known the story of Muni, which dates back to 1883. Muni���s husband Ramsamy attacked her, leaving pieces of her vulva on the floor and inducing a miscarriage. When medical assistance arrived two days later, she was alive, barely, and had scorch marks on the bulk of her torso. Her husband was a medical officer himself, and ran away from the scene.

Ten years later in 1893, another Indian woman in Natal, Votti Veeramah Somayya, fought to be moved from her indentureship position in Charlie Nulliah���s estate. Nulliah ���made indecent overtures��� towards Votti, the Indian Protectors��� records show. When she refused his advances, he assaulted her. Even after pleading her case with the Protector, asking for ���another master���, she was told to go back to Nulliah. She refused, and was sent to prison for approximately seven months.

As documented in the Coolie and Wragg Commissions into the conditions of indentured labor in Colonial Natal, Hindu women were thought to be sexually promiscuous and the ���dregs��� of society. Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed explain this in their book, Inside Indian Indenture. They note that while Indian women in India were regarded as ���victims��� of tradition, in South Africa, Indian indentured women were seen as sexually promiscuous���as disorderly troublemakers whose sexuality was difficult to control.

The unique circumstances of indenture meant that indentured women commonly engaged in sex work. The plantation compounds in which they lived were seldom safe���there were very few social safeguards because there were a dearth of laws governing indentured populations marriages and little by the way of cultural support systems in cases of divorce or childcare.

Muruganlakshmi felt this in her own life. Her husband believed she was sleeping with other men. As she was jumping out the window, she remembers her husband saying she was ���jumping to meet another fella,��� and her financial independence was a threat to him. He didn���t want her to make money independently of him. Muruganlakshmi recounted:

I was a dressmaker. And one day he came home, saw the clothing. I wasn’t at home at ������ that time. He took all my customers’ clothing���I’m getting goosebumps now���eh, he cut up everything with the scissors. Cut up! The measurements, the clothing I finished [working on]. When I walked into the house, I was practically walking on clothing that was already cut up. My clothes. Customer’s clothes. I was shocked. That time, I got a breakdown.”

The plantation compounds that indentured women lived in long before Muruganlakshmi���s time were rarely stable spaces for family, and ���was a dangerous site for rupturing the patriarchal order,��� note Desai and Vahed. ���Over time, the story would be of legislation to re-inscribe the gendered patriarchal order, or approximations of it, and re-institute the ���stable��� family.���

Hindu women were seen to be ungovernable���both by indentured men, and colonial officials���and legislation in the early 1900s sought to legalize patriarchal kinship to give indentured men a legal framework to create and maintain control in domestic spaces.

���While official explanations viewed violence against women in ���cultural��� and racist terms, the result of Indian men���s contempt for women and their ���possessiveness���, the reasons for violence were complex,��� writes Goolam Vahed in African Masculinities.

‘Nothing moves, but the shifting tides of salt in your body’ (2020) Alka Dass.

‘Nothing moves, but the shifting tides of salt in your body’ (2020) Alka Dass.Once indenture formally ended in South Africa in 1911, white officials didn���t want the descendants of indentured labor to consider that South Africa might become their permanent home. In the 1920 and 1930s, analogous to legislation that dispossessed Africans of land, voting rights, freedom of movement and more, there was anti-Asiatic legislation that withdrew citizenship, trading and freedom of movement rights from the descendants of indentured labor, as well as Indian traders and shopkeepers.

By the time apartheid was officially instituted in 1948, descendants of indentured labor had already been corralled in segregated communities like Clairwood and Magazine Barracks in Durban, and around sugarcane plantations on the North Coast. As Indian ghettos grew, women���s roles in the community grew both more precarious and more stable. No longer ghosts living in compounds, women were closer to others in community. Still, the shame of indentureship hung over them.

After Muruganlakshmi���s escape, she went to the hospital. After receiving medical care, she returned to her husband, and never reported being abused to the police or social services. She didn���t upset the balance of her relationship as her children grew up, remaining married until his death in the 1970s. Still, it wouldn���t be fair to say that Muruganlakshmi stayed silent.

She was proud of herself and also honest about what she had been through. That combination struck me as profound. Muruganlakshmi wasn���t ashamed of herself.�� Like Votti, who had spoken up in self-defense, and Muni, who fought for herself and her unborn child, Muruganlakshmi���s voice was strong.

The violence that marked each woman���s life was deeply interwoven with the notion that they were transplants. Shorn of connections, living in a lacunae of the law and culture, South African Indian women���s lives echo with the aftershocks of indenture.

Today, although there are promising policies to address gender-based violence on a national level, the everydayness of intimate partner violence needs to be discussed. In my research I turned to the temple as a potentially caring institution���only to discover that it cares for those it deems deserving, which does not include victims of domestic and sexual violence.

Muruganlakshmi lived with very little support from her community, or even acknowledgement of her struggles. Despite her prominent position in the temple as a harmonium player, the temple congregation only reached out sporadically to her���offering commiseration rather than direct action. When we spoke, I asked if she went to a social worker or any organization that helps abused women. Muruganlakshmi said no. ���I made do with self-made support,��� she replied with a dry laugh.

The last time I saw Muruganlakshmi was at my grandfather���s funeral in 2018. At 82, she was unwell, forgetting where and who she was with for a few minutes at a time. Still, she had managed to show up to support another family.

Muruganlakshmi passed away in April 2020 at the beginning of South Africa���s protracted COVID-19 lockdown. We couldn���t say goodbye to her in the usual ways. Following Hindu funeral rites, her body was cremated, and we said farewells from inside our separate homes and the light of our own God lamps.

Water is life

Image credit Sianid Poisen via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit Sianid Poisen via Wikimedia Commons. This post is from our series Capitalism In My City, presented in partnership with the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

The current COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to posing a tremendous risk to the health of the people of Kenya, has vividly exposed the worsening humanitarian crisis facing the informal settlements of Nairobi. Access to essential services and amenities, such as electricity and clean water, has become extremely difficult due to the presence of local cartels and outright inefficiency by the government. The government has failed to implement Article 43 of the Constitution of Kenya from 2010, which gives every Kenyan the right to adequate clean water.

Mukuru is a slum based in Nairobi���s Embakasi South constituency, where residents struggle to access water and electricity on a daily basis. Currently, both clean water and electricity are under the supply of profit-seeking cartels. Shortages of the same are experienced regularly as well. In this area, the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company (NCWSC) supplies water to cartels who then supply it to water vendors who then sell it to residents at very high prices due to the long water supply chain. This arrangement is enabled by the presence of a corrupt group of officials within the county authorities who work in collusion with the cartels at the local level.

Without electricity, people find it difficult to pump water into their households. This makes water all the more inaccessible.

20 liters of water goes for Ksh. 5 ($0.05) in Mukuru. The irony is that Imara Daima, a middle class estate which borders Mukuru, has a constant supply of clean water provided by the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company. Middle class and richer estates in Nairobi, such as Westlands, are supplied water at a rate of between Ksh. 48 – Ksh. 60 ($0.48 ��� 0.60) per unit of water, which is 1000 liters of water. This means that for 1000 liters they pay five times less than slum dwellers.

The inadequate supply of clean water makes Mukuru a hotspot for cholera, typhoid as well as other diseases. The pipes that supply water also pass through sewer lines, making it an extreme health hazard. The lack of water also makes it difficult for young people to have businesses such as car washing stations and others that require water. Has the government intentionally decided to frustrate poor people?

In Mathare, the situation is worse. In 2018, a community report on water access by Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC) showed that water in this community is often contaminated with Escherichia coli, also known as E. Coli, which causes bacterial infections, diarrhea, and fever. A recent news report showed that people in Mathare cannot afford to take a bath daily, but instead have a bath once every 2-3 days (sometimes even only once every five days). It is extremely frustrating for young women on their period to stay hygienic. Water scarcity in Mathare was made worse after the post-election violence in 2007-2008 when water service providers cut the water pipes in almost all wards in the area due to politically driven motives. Now the water is supplied through illicit communal pipes or through water vendors and kiosks.

One household of about five people is expected to pay around Ksh. 900 ($9) in a week for a water supply that is also contaminated. It is too expensive to live in an informal settlement where to afford even Ksh. 200 [($2) to buy food for a day is difficult for a person. How are the people meant to effectively fight COVID-19 in the midst of all these challenges?

The lack of water enslaves people in informal settlements, from Mathare to Mukuru, forcing them to rush to hospitals seeking treatment for water borne diseases. Furthermore, it leaves them completely exposed to infection by corona virus. Healthcare is privatized and expensive, chaining people to private money lending institutions which give loans at high interest rates, causing a vicious cycle of debt slavery and poverty.

Some politicians from the major political parties in Kenya supply water during the campaign period as a tactic to influence poor people to vote for them. For example, Mike Sonko, the current ceremonial governor of Nairobi, anchored his 2017 campaign on voter bribery. His ���Sonko Rescue Team��� supplied Nairobi informal settlements with water, fire-fighting services, free medical care, and other such essential services for several months prior to the election. Interestingly, this is supposed to be the job of the government as our taxes pay for these services. Once he got the seat as governor, he has not once talked about the water crisis. As expected, his free water, medical, and fire-fighting services stopped altogether. And so the crisis that is killing the informal settlements goes on. Clearly, Governor Mike Sonko saw the need for water but remained silent about it ever since he came into power. The reason for the silence is a desire to keep the masses destitute and vulnerable in order to be able to influence them again in future.

The Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company has given water cartels the permission to enrich themselves by frustrating the common person. In Kayole, another group of water cartels dig boreholes to supply salty water to residents at between Ksh 20 – Ksh 25 ($0.20 ��� 25) per 20 liters of water, which translates to 20-25 times the price in better off areas. On the May 6, 2020, community members of Kayole and Komarock, spearheaded by the Kayole Community Justice Centre and Al Qamaar Community Justice Centre, went to the NCWSC branch at Shujaa Mall to demand water as there had been a shortage in these communities for three weeks. Nine members were arrested and threatened with court so as to silence the community demands. It was not until the demand for water was amplified by members of the community that water was availed.

Instead of providing clean water, the Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company recently gave permission to water cartels to supply salty water to households that already had a piped water connection. Houses that didn���t have these connections would continue to buy water from the vendors. Many residents in Kayole have been affected by diseases caused by the consumption of this water. Car washing stations use fresh water to wash cars as salty water is harmful to vehicles. If salty water is harmful to vehicles built by metal, what can it do to the human body? Most children in Kayole are growing up with weak gums, weak bones, and brown teeth due to the consumption of salty water which is corrosive. At some point, some children have to get their teeth removed.

Why do we have a water crisis when people who have much higher incomes live in houses where water flows through their taps like rivers at much lower prices? Are we, the people in the informal settlements, lesser human beings? Why is water a privately sold commodity in a city like Nairobi with millions of low income and poor people who depend on water for survival?

We call upon the government to fully implement Article 43 of Kenyan constitution and provide clean and adequate water to all. We demand that our resources be distributed equally to all people. The question of water scarcity has been an unsolved crisis since Kenya gained its independence, and has to be therefore addressed once and for all. Water must not be viewed as a commodity to be sold in the market for profit, but as an essential service to be provided for survival. Maji ni uhai (water is life) and we should not be begging for it.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers