Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 140

February 8, 2021

Homelessness and (un)affordable housing in Nairobi

Photo by bennett tobias on Unsplash

Photo by bennett tobias on Unsplash This post is from our series Capitalism In My City, presented in partnership with the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

Every Sunday morning, while I cycle along Juja Road in Nairobi, I���m reminded of the disparity in our city. There are many faces of despair and hopelessness along the road. On one side, citizens waking up from their shanties, all moving towards different places in search of mostly daily wage casual jobs. On the other are clusters of street and homeless families living along this busy throughfare. They have made the pavements, shop verandas, and walls along this road their home. They wake up every day from their ���homes��� and try their best to meet their basic needs.

In this same city where others spend a fortune to go for vacations to sleep in tents and camping bags, others have been subjected to this kind of life without an alternative. These families are forced to endure the March-May long rains, June-August cold and the short rains in September-November, without any option. Most of the children from these families have never had the luxury of living or sleeping in a house. All they have known are these streets they have been raised in.

I���ve lived a good part of my life in Mathare 4A, part of the larger Mathare slum in Nairobi. The houses on this side of the city tell a sorry tale. By any standards, they are not housing, but shacks made of iron sheets, plywood, mud, and a few bricks. They are built on any space available: over open trenches, piped water passing in the same trenches and illegal electricity connections passing below and over these trenches.

Several years back, open defecation was the norm along the river. This however changed as the community managed to build toilets instead. To date, toilets have been built along the river, emptying their raw waste directly into these natural but polluted water streams.

This is the kind of life I���ve grown up in. When growing up, my siblings and I would take a bath in the open fields at night. The only ���shower room��� for use in our area was a space between two houses with an open trench passing through. The door was a sack, and two stones were right in the middle of the trench: one as a platform for placing your bucket and the other for you to step on. The dangerous part of this community bathroom was that illegal electricity connection were rampant in this area, and so to hide these connections from Kenya Power officials, they had to be passed through this area, dangling dangerously a few centimeters overhead. This posed a significant risk for all households, and fire tragedies were our life in this part of the city���three months without a fire tragedy would be a good reason to thank the Lord. Whenever fire broke out, it relied squarely with the community to put it out, as firefighter engines would take time navigating their way in these areas. That is if they came at all.

In the early 2000s, our shanties were managed by Amani Housing Trust, an organization that had started a program to replace the corrugated iron sheet houses with brick ones. When I was in my lower primary years, I would come home from school only to find nearly all the houses in the neighborhood locked for defaulting on their Ksh 200 monthly rent (currently about 2 USD). To lock more than 3,000 houses in the whole of Mathare 4A would require the same number of padlocks, and maybe a truck to carry them. To avoid this costly approach, Amani Trust Housing operatives used large nails to lock the doors to the frame. As a result of years of this operation, most of the doors were usually tattered. To date, some doors still tell these sad stories of the past.

The issue of decent housing and sanitation are very much intertwined. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the worst that these communities face. It came and complicated an already grave situation in Mathare. Normally residents have to walk several hundred meters, and in some cases more than a kilometer, to access sanitation blocks. The 7 pm curfew came as a punishment by a government that never wanted to listen to the particular conditions the communities living in these areas go through. Police brutality, and in some cases killings, were reported, violence meted out on citizens who had gone to answer the call of nature.

In Mathare Area C (Bondeni area), a homeless man was shot dead for being outside his ���home��� past the curfew time. In Majengo slums, a child was shot in the comfort of their house���a stray bullet ripped through the iron sheet walls where the young one was living. Huruma and Mathare North areas, surrounding Mathare slums, have had their own shares of tragedy. Substandard buildings have collapsed in the past, killing dozens in some instances.

Successive governments have said that they have tried to solve the issue of housing in the capital. Slum upgrading projects started, only to be marred by corruption and a lot of interests and politicking. Recently, the Jubilee Government launched its flagship project: affordable housing under its ���Big 4 Agenda.��� Despite assurances from the government that the issuance of these housing units will be done in a very transparent manner, there have been cases of corruption and favoritism. It has turned out to be the usual scenario: the highest bidders taking the houses and using members of the same family, with different names, to register the units. These units are then sold to others at exorbitant prices, beating the logic of affordable housing. At the same time, the units are still much too expensive for the common citizens from the slum areas, who ought to be the primary beneficiaries of this project. Most of them survive on meagre daily wages which are not even enough to meet their most basic needs.

Growing up in the poorer east side of the city, I���ve always yearned for the good life I see on the more prosperous side���the western side. This is an area that is in stark contrast to our reality: these areas are mostly gated, leafy suburbs, dotted with mansions, bungalows, and high-rise buildings for commercial purposes. These areas have state of the art recreational facilities, access roads for private cars, and golf clubs with beautiful lawns. As a young man, I still fail to understand why many buildings in the business districts and other areas can go without tenants for more than a year, even where there are so many homeless people in the country. I feel the pain when going through the daily newspapers and realizing that the owners of these fine buildings are running into losses for lack of tenants, and yet they are still spending a lot of money on billboards and print media advertisements. And these perfectly good building, with water and services, are not accessible to us.

On the other side of the town, we humans are crammed in tiny, unhygienic areas. When I go through history, I���m reminded of the capitalistic route that we chose as a nation, and which our neighbors, Tanzania, chose to call ���a man eat fellow man society.��� Everything has been commodified for profit making. Fifty-seven years on as an ���independent��� country,�� and we are still grappling with high levels of poverty. Home and land ownership is still a mirage for many including the middle class, which continues to be a very elusive status. A few families in Kenya control large tracts of land, which is a primary means of production. This has over time ensured that these families do business with the government, which they are already a part of. Every project being carried out by the government is viewed from a profit perspective by these families, and if no profits are accrued from it, then it���s as good as dead. This has condemned the majority of city residents to live in shacks, or in sub-standard housing, and the unlucky ones bare the cold of the night. Capitalism entrenched an insatiable greed that never seems to be quenched and has robbed communities in the slums of their dignity. Unless an overhaul of this oppressive system happens, decent housing will remain a pipe dream and a campaigning tool for the next kleptocrats. Unfortunately, in the meantime, I continue to meet the very same families, waking up in the cold on Juja Road.

The miseducation of the Nigerian middle class

Photo by Ovinuchi Ejiohuo on Unsplash

Photo by Ovinuchi Ejiohuo on Unsplash Nigeria���s #EndSARS movement has been hailed as a new generation���s attempt to challenge the status quo. Its ability to transform online disaffection by its youthful population towards offline protests and direct action has resulted in it being treated as the most formidable opposition to the Buhari administration. While this is not the first movement to have transformed online angst into visible activism on the streets of urban centers (there was #OccupyNigeria in 2012 against the petroleum subsidy), the depth and breadth of people and organizations (such as the Feminist Coalition, Gatefield Media, and Amnesty International, among others) that participated in and backed the protests is unrivalled. #EndSARS has mobilized the middle class���a group notably indifferent to Nigeria���s political elites��� machinations or, at worst, active collaborators with them.

Discussions on where #EndSARS could and should go have excited political commentators, members of the movement, and the general public especially after the end of most protests across the country. An interesting suggestion that has gained ground is for the movement to carry out mass education programs to the working class and the urban poor, ostensibly to inform these groups of the repressive nature of the political elite. The reasoning behind this approach is insinuations that these groups are the Achilles heel of efforts to challenge the elite. The belief that members of the working class, urban, and rural poor elect members of the political elite solely because they have been able to mobilize them either on ethnic terms or by financially inducing them has allowed this idea to gain currency. Since the nation���s return to democracy in 1999, the middle class has collectively stepped away from the electoral space. This is evident in its inability to create a party platform that can attract the working classes. The working and urban poor, on the other hand, are more likely to vote, be party members, participate in the democratic process, and to protest injustices that impact them disproportionately.

The purported renaissance of Nigeria���s middle class post-1999 was expected to entrench democratic norms and ideals. The proliferation of local civic society organizations to tackle endemic issues, such as corruption (Budgit, NEITI), the electoral system (YIAGA) and bad governance (EIE), seemed to emphasize the emergent possibilities of citizen action toward creating a more representative governance system.

In reality, Nigeria���s middle class are unwilling to act, despite bearing a significant brunt of the political class���s governance programs that have ensured their decimation and impoverishment���such as those that have reduced public sector spending, results of which are clearly apparent in the nation���s poor healthcare system and substandard educational facilities; others that have sought to perpetuate corruption, such as the security vote system that sees state governors spending public funds that are not subject to legislative oversight or independent audit. The regressive agenda of gender inequality goes beyond mere utterances (the current Nigerian President once stated that his wife belongs in the kitchen and the bedroom in a meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel). Nigerian women suffer some of the highest maternal mortality rates, with legal structures still restricting their basic rights and only four percent of elected officials are women.

Yet, the middle class has imbibed the belief that less government is better and has set out to interact and participate with governance in a ���limited capacity.��� Those that participate appear content to serve as technocrats to provide intellectual backing and lend professional gravitas to the repressive policies pursued by the state. The middle class has championed the status quo by preaching the gospel of economic development in spite of the government by highlighting the various problems that the country faces. They erroneously promote the belief that the country���s economic stakeholders have earned their positions as a result of their business savvy or prowess. Their determination to view the�� country���s dire economy through rose-colored spectacles and dismiss the structural realities of the Nigerian state���where a clear majority of economic activities focuses on seeking to profit from government dysfunction���are upheld. Quite often they go as far as highlighting the various handicaps, but position them as business opportunities that can be solved by foreign direct investment, limiting the role of the government to create an ���enabling environment.���

The refusal of the middle class to tackle the regressive agendas of the ruling elite has led to the latter being let off the hook: The middle class is instead viewed as the tool that functions in the subjugation of the working class. In fact, they are the visible representation of a country that is designed to work for a few at the expense of many. The historian David Motadel rightly notes the activities of American and European middle classes, which have actively championed conservative nationalism and authoritarian leadership over centuries���in essence, positing that middle classes in Africa are also disinclined to push for democratic reform.

Yet, in Nigeria, middle class activist history is a little more complicated. While the nationalist movements resulted in power being handed over to a political elite, the actual struggle comprised of various groups, especially those formed and manned by middle class members who* utilized western social and political ideals in the fight for independence. Coleman���s study of Nigerian nationalism notes that middle class individuals, such as Herbert Macaulay, an engineer and journalist, and Ernest Ikoli, also a journalist, founded and led political organizations and movements while training and mobilizing countrymen around the values of nationalism. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti���s Abeokuta���s Ladies Club (later the Abeokuta���s Women Union) took on the Native Authority System administering British indirect rule. During the struggle for democracy this professional class built linkages with organized labor and provided intellectual support for the movement. Individually and collectively, through groups such as the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) and the Nigeria Bar Association, the middle class worked to reform the electoral process, reform institutions of governance, and build networks to protect these reforms. Some might argue that we owe our fraught but enduring democracy to this iteration of the middle class.

It is clearly in the interests of the middle class to rid the country of a political elite that has shown that itis not only anti-intellectual but also willing to cannibalize the cosmopolitan culture and entrepreneurial economy that the middle class holds dear. The incremental improvement in governance that the middle class considered as fait accompli with the return to democracy in the fourth republic has not occurred. On the contrary, there has been a rotation of vivid and subtle tyranny.

Signs of a middle-class awakening abound. The 2019 elections saw the emergence of ���third party��� candidates to challenge for the presidency. While these efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, they highlighted that a growing number of the middle-class Nigerians are unwilling to endorse the status quo. Organizations such as ASUU, for example, continue to challenge the gravely unjust system, by forcing the government to recognize the need for increased funding in public universities.

So where does the middle class go? Perhaps the #EndSARS protests and even the riots provide lessons for the middle class and offer opportunities for introspection among members. Jamaica and the Rodney Riots provides a vision for a possible future. In 1968, Walter Rodney was banned by the Jamaican government from re-entering the country to continue his teaching and research at the University of West Indies. Rodney, an academic who had pulled no punches in criticizing the middle-class became a symbol for a protest movement that brought together what Klug describes as: young people, middle-class intellectuals, and working class Jamaicans. The Rodney riots and the alliance it birthed is credited with the victory of Michael Manley���s People National Party win in 1972. Could the enduring effects of #EndSARS be the beginning of a broad alliance against an irresponsible political elite that has shirked all pretensions of being responsible to the people?

The focus of political education programs must target the middle class and should be executed in tandem with members of the middle and working classes. Erroneous beliefs, such as the country being solely organized on ethnic or religious lines, must be tackled and the need for an independent media outside the hands of the political elite must be emphasized. We must promote and encourage debates around the pervasive reasoning that the only way to win political elections is by amassing funds from the private sector or by playing groups of the political elite against each other. Finally, and most critical, is the need for organization / mobilization of the middle class in their places of worship, workplaces, professional organizations, and communities.

February 7, 2021

Hamba Kahle Sibongile Khumalo

Winston Mankunku Ngozi, Thandi Klaasen, Sibongile Khumalo and Spencer Mbadu at Manenberg's Jazz Cafe in Cape Town. Credit: Suren Pillay.

Winston Mankunku Ngozi, Thandi Klaasen, Sibongile Khumalo and Spencer Mbadu at Manenberg's Jazz Cafe in Cape Town. Credit: Suren Pillay. On January 28, South Africans mourned the untimely passing of another musical giant, as the voice of Sibongile Khumalo went silent.

Born in Soweto on September 24, 1957, Khumalo grew up surrounded by music. Her father, Khabi Mngoma, led a choir, in which she sang and played the violin. He later established a music department at the University of Zululand and became a professor there.

Interviewed in Afripop! on the occasion of her 60th birthday Khumalo recalled:

Music to me is life. It is an intrinsic part of who I am and what I do, so much so that one almost takes it for granted. I do not know if I would have done anything else with my life, because I was really never exposed to anything else as a child [smiles]. The curious thing is that we never spent family moments making music. It was like breathing ��� pervasive, ever present yet unobtrusive.

In a 2014 interview in the UK Independent she explained: ���Since everything was communal, we all heard each other���s music: some neighbours held church services in their yard, some played drums, some���like my elder brother���played jazz, so I grew up surrounded by myriad sounds.���

At eight years of age Khumalo began learning violin, singing, drama, and dance. She would later train for a career as a music teacher, obtaining a BA in music at the University of Zululand, and a BA Hons from the University of the Witwatersrand.

In the early 1990s she became a full-time artist. Her repertoire was mainly classical music, specialising initially in Lieder by Schubert and Brahms. She made her opera debut in Carmen, and in 1995 she sang in H��ndel���s Messiah under conductor Yehudi Menuhin. At the same time, she was also performing in clubs as a jazz singer. In 1993 she won the prestigious Standard Bank Young Artists Award at the Grahamstown Festival.

Although Western classical music was originally a big influence, African music traditions became increasingly important. In 1996 she released her first album, Ancient Evenings. She told the Independent: ���I knew when I came to record my first album, it wouldn���t be of European art songs, even though I���d studied them and could do them well, because that music didn���t express who I am.���

The record featured African hymns, mainly in indigenous languages, and it became an immediate success. It won the South African Music Awards (SAMAS) for Best Female Vocal Performance and Best Adult Contemporary Performance. Live at the Market Theatre (1998), Immortal Secrets (2000), Quest (2002), and Breath of Life (2016) followed, and Khumalo consolidated her reputation as one of the most influential South African vocalists���trained in the classical genre, but transcending it by fusing elements of jazz and traditional African music to create a special South African brand.

In 2007 Khumalo launched her own label, Magnolia Vision Records. In 2013 she was a soloist in Credo, a multimedia oratorio composed and performed in honor of The Freedom Charter.

Sibongile Khumalo defined herself as a storyteller, a messenger. She was also a strong advocate for the performing arts and for the rights of women. ���I have a greater awareness as a contemporary African woman, of the need to not only speak [as an] African, but to practice and live African. My spirituality is very much an expression of being an African, as I understand it today.���

She was awarded several honorary doctorates for her contributions to music, and in 2008 The Order of Ikhamanga in Silver by the South African Presidency for ���her excellent contribution to the development of South African art and culture in the musical fields of jazz and opera.���

Khumalo���s dedication to her craft was imbued with self-respect, dignity, and pride. As she remarked in her interview with Afripop!: ���We often equate leaving a legacy with putting up physical structures��� yet unless those structures are imbued with a certain quality or value, they will not really mean that much to those for whom they are intended.���

The quality and value of Sibongile Khumalo���s life and artistry is a legacy to be revered and cherished. It will live long in South African music history.

February 5, 2021

Telling stories about Africa

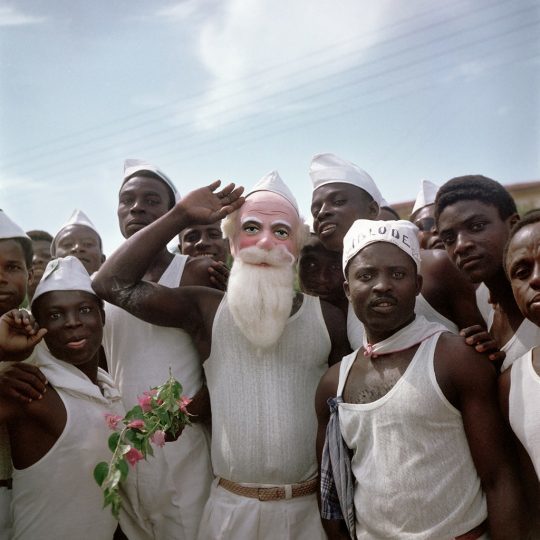

Image credit Todd Webb.

Image credit Todd Webb. On the 16th of January 2020, Uganda���s Electoral Commission declared incumbent Yoweri Museveni the winner of the presidential election, held two days prior. Museveni, who has been in power since 1986, ensured an unfree and unfair election, marred by violence, intimidation, and the harassment of the political opposition, specifically targeting the musician-turned politician, Bobi Wine.

Wine (whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu), has emerged as a fierce challenger to Museveni���s stranglehold on power. Amassing 35% of the vote in what was a credibly stolen election is a serious feat, and Wine���at the helm of the People Power Movement,�� now transformed into the National Unity Platform���is widely recognized as the man most likely to topple Museveni���s government if the opportunity arises. As a representative of Uganda���s urban youth, Wine gives expression to their anger at the increasing joblessness and inequality presided over by a corrupt political class with Museveni as its figurehead.

But who exactly is Bobi Wine? Setting aside the system he rejects, what does he stand for? A new podcast series hosted by the Sudanese-American rapper Bas, and produced by Spotify, Dreamville Studios and Awfully Nice aims to probe exactly these questions. The Messenger follows Bobi Wine���s rise from his upbringing and his artistic career all the way to his political prominence. This week on AIAC Talk we���re joined by two of its producers, Dana Ballout and Adam Sj��berg.�� Dana is a Lebanese-American documentary producer, podcaster and journalist, while Adam is a documentary filmmaker and commercial director based in LA too. We want to ask them what they���re uncovering about Wine, his life story, political influences and worldview. We���d also like to hear about the podcast��� who���s behind it, how it came together, and why podcasting was the chosen medium to tell this ongoing story. And why this story?

And then, from unpacking one medium, we move to another. Next, we���re talking to Aim��e Bessire and Erin Hyde Nolan. Aim��e is an affiliated scholar who teaches African art history and cultural studies at Bates College, and Erin is a visiting assistant professor at Maine College of Art, where she teaches the history of photography, and visual culture, and Islamic art. Both of them, are the authors of Todd Webb in Africa ( Thames & Hudson, 2021),�� a collection of photographs taken in Africa by the renowned photographer Todd Webb. While his shots of everyday life in big, Western cities like Paris and New York are well-known, less so are the ones from his travels in Africa, taken in 1958 across Togo, Ghana, Sudan, Somalia, and what we now know as Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Tanzania. That some of these countries were once known by different names, summarises the period of tremendous change and upheaval that the photographs capture, located at the ���interstices of colonialism and independence��� as the authors write in the book���s introduction. We want to talk about the photographs, the people and places portrayed in them, but we also want to talk about the politics of photography itself��� whose gaze reflects them, what narrative are they trying to push? For example, what are we to make of the fact that Webb���s project was commissioned by the United Nations?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we spoke to Yotam Gidron and Matshidiso Motsoeneng about Israel���s relationship to Africa, what it is its history, and how the apartheid-state is making renewed efforts to court the continent for international legitimacy. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

Portraying a man, portraying a continent

Image credit Todd Webb.

Image credit Todd Webb. On the 16th of January 2020, Uganda���s Electoral Commission declared incumbent Yoweri Museveni the winner of the presidential election, held two days prior. Museveni, who has been in power since 1986, ensured an unfree and unfair election, marred by violence, intimidation, and the harassment of the political opposition, specifically targeting the musician-turned politician, Bobi Wine.

Wine (whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu), has emerged as a fierce challenger to Museveni���s stranglehold on power. Amassing 35% of the vote in what was a credibly stolen election is a serious feat, and Wine��� at the helm of the People Power Movement,�� now transformed into the National Unity Platform��� is widely recognised as the man most likely to topple Museveni���s government if the opportunity arises. As a representative of Uganda���s urban youth, Wine gives expression to their anger at the increasing joblessness and inequality presided over by a corrupt political class with Museveni as its figurehead.

But who exactly is Bobi Wine? Setting aside the system he rejects, what does he stand for? A new podcast series hosted by the Sudanese-American rapper Bas, and produced by Spotify, Dreamville Studios and Awfully Nice aims to probe exactly these questions. The Messenger follows Bobi Wine���s rise from his upbringing and his artistic career all the way to his political prominence. This week on AIAC Talk we���re joined by two of its producers, Dana Ballout and Adam Sj��berg.�� Dana is a Lebanese-American documentary producer, podcaster and journalist, while Adam is a documentary filmmaker and commercial director based in LA too. We want to ask them what they���re uncovering about Wine, his life story, political influences and worldview. We���d also like to hear about the podcast��� who���s behind it, how it came together, and why podcasting was the chosen medium to tell this ongoing story. And why this story?

And then, from unpacking one medium, we move to another. Next, we���re talking to Aim��e Bessire and Erin Hyde Nolan. Aim��e is an affiliated scholar who teaches African art history and cultural studies at Bates College, and Erin is a visiting assistant professor at Maine College of Art, where she teaches the history of photography, and visual culture, and Islamic art. Both of them, are the authors of Todd Webb in Africa ( Thames & Hudson, 2021),�� a collection of photographs taken in Africa by the renowned photographer Todd Webb. While his shots of everyday life in big, Western cities like Paris and New York are well-known, less so are the ones from his travels in Africa, taken in 1958 across Togo, Ghana, Sudan, Somalia, and what we now know as Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Tanzania. That some of these countries were once known by different names, summarises the period of tremendous change and upheaval that the photographs capture, located at the ���interstices of colonialism and independence��� as the authors write in the book���s introduction. We want to talk about the photographs, the people and places portrayed in them, but we also want to talk about the politics of photography itself��� whose gaze reflects them, what narrative are they trying to push? For example, what are we to make of the fact that Webb���s project was commissioned by the United Nations?

Stream the show Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week, we spoke to Yotam Gidron and Matshidiso Motsoeneng about Israel���s relationship to Africa, what it is its history, and how the apartheid-state is making renewed efforts to court the continent for international legitimacy. Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

Black faces in high places

Ngozi Okonjo Iweala speaking at the UK-Africa Investment Summit in London 20 January 2020. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Ngozi Okonjo Iweala speaking at the UK-Africa Investment Summit in London 20 January 2020. Image via Wikimedia Commons. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the former finance and foreign minister of Nigeria, is widely expected to become the next head of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Okonjo-Iweala was in the running for president of the World Bank (WB) in 2012 before the former US President Barack Obama chose an American man, Jim Yong Kim, for the position. During her campaign for president of the World Bank���and now for the WTO���many commentators have heralded the importance of having a Black African woman at the head of a major international financial institution as ���a defining moment for Africa, long under the boot of foreign powers and financial institutions.��� The Pan-African left must, however, reject the politics of representation for representation���s sake. If the point is to have a Black African woman provide cover for the same neoliberal policies that have hindered economic development in Africa, then such representation is counterproductive.

Along with the IMF and World Bank, the WTO forms part of the ���Unholy Trinity��� of international institutions that govern the global trade and financial system to the benefit of major multinational corporations and their shareholders and to the detriment of ecosystems and workers everywhere. The WTO was created in 1995 at the height of post-Cold War neoliberal triumphalism. It replaced the looser General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), with a permanent organization that could more easily sanction countries that tried to restrict foreign trade, most notoriously by giving foreign investors the ability to sue states under an opaque arbitration process. The GATT had allowed Global South governments to implement modest forms of infant industry protection and other trade restrictions for development purposes. The US and European governments sought to weaken these provisions and to extend principles of free trade to services and intellectual property. A global coalition of labor and environmental groups famously stunned the organization with protests that disrupted its annual meeting in Seattle in 1999.

Despite being hailed as a ���development round������ostensibly focused on the needs of the poorest nations���the latest series of global trade negotiations stalled as governments in the Global South, led by India and China, resisted further opening their markets to North American, Western European, and Japanese capital. They also insisted that governments in the Global North open their markets to agricultural exports from the South by reducing trade barriers, especially their massive subsidies to domestic agribusiness.

The question for the next head of the WTO therefore is: whose side are you on? Will Okonjo-Iweala put an African face on the North���s agenda to expand free trade and reinforce the power of major multinationals or fight for the right of Southern governments to subordinate international trade to their own domestic development priorities? While the Nigerian government has a reputation for protectionism���one that proponents of the African Continental Free Trade Area fear may scuttle the project���Okonjo-Iweala is known as an orthodox economist with a decades-long career at the World Bank. Her candidacy for World Bank president was endorsed by the likes of The Economist and The Financial Times, hardly the friends of Africa���s workers and peasants.

Okonjo-Iweala���s record in office has provoked the ire of the Nigerian left. Many opposed her first major act as finance minister: the deal with the Paris Club���a grouping of Western and Japanese official creditors���to restructure Nigeria���s foreign debt in 2003. She negotiated a reduction of Nigeria���s debt from approximately US$35 billion to $17.4 billion, including an immediate payment of $12.4 billion. Many Nigerian progressives argued that since the debt was contracted by corrupt military dictatorships and the lenders knew that the funds would be stolen, the people of Nigeria should not have had to repay a single dollar. The debt was odious and should have been repudiated. The billions in repayments could have paid for teachers, nurses, and infrastructure instead.

In her second stint as finance minister, Okonjo-Iweala became the public face of the deeply unpopular decision to remove the subsidies on fuel in January 2012, which led to a doubling of transport prices overnight and a sharp rise in the cost of living. Millions of Nigerians felt that the fuel subsidy was the only benefit they received from their country���s vast oil wealth and did not trust their political leaders to reallocate funds to social spending as they were promising. The move sparked a national strike and the Occupy Nigeria protests, joined by artists like Seun Kuti, Wole Soyinka, and Chinua Achebe.

In the decades since the end of formal colonialism, many Africans have learned (the hard way) that having leaders that look and sound like you matters little if they pursue policies that hurt most of your fellow citizens. The selection of Okonjo-Iweala���or any other candidate���to head the WTO matters only to the extent that their leadership opens policy space for developing countries to pursue industrial policies. The hope is that a WTO President from the Global South would be more sympathetic to the challenges posed by the global trading system to peripheral economies, but Okonjo-Iweala���s record does not inspire much confidence in this regard. While the ���gentlemen���s agreement��� between the US and European governments whereby the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is always a European and the head of the WB an American is unjustifiable, the Pan-African left should push for a more equitable global economy, not simply more ���black faces in high places.���

February 4, 2021

The business of Black death

Image credit James Oatway for IMF Photo via Flickr CC.

Image credit James Oatway for IMF Photo via Flickr CC. Africa entered the global COVID-19 discussion in typical fashion���shrouded in a discourse of lament and crisis. In April 2020, while New York City held on securely to the title of ���COVID-epicenter��� (after Italy relinquished the title), scholarship and opinion pieces proliferated, predicting that Africa���s demise was on the horizon. A public health expert writing for The World Economic Forum (WEF) warned that Africa had a ���time bomb to diffuse.��� As wealthy countries grappled with their own inundated health systems, more Africans would die because the West could not afford to help. In May, Yale School of Medicine forecasted that by the end of June, 16.3 million Africans could contract the virus���a 135% increase in the number of cases from April to May and 39% increase from May to June. Lack of health infrastructure, high user fees, large refugee populations, high rates of comorbidity indicators, poor governance, corruption, and lack of sanitation were just some of the factors informing the anticipated COVID-related death toll in Africa.

Studies like these were plentiful in the early months of the pandemic. The reality, however, strayed far from the science and expert opinions. By August, the number of COVID cases on the continent remained low in both absolute and proportional terms. This time, the experts began to postulate why Africans were not dying as they had predicted. In the aftermaths of these errant conjectures, headlines like ���Scientists can���t explain puzzling lack of Coronavirus outbreaks in Africa��� dotted the media landscape. Again, public health experts returned to what they had previously adumbrated as exposing the continent to high cases of COVID-19���poverty, population density, demographic structures, co-morbidity factors. Some even suggested that the numbers were a result of low testing, which has since been disproven. What the predictions hadn���t taken into account was how quick to act most African countries would be. Ghana was one of the first countries to close all of its land and sea borders. For nations that had been impacted by Ebola, there was still infrastructure in place to respond to COVID, thus minimizing spread. Senegal and Rwanda also had noteworthy responses characterized by innovative solutions to treatment and contact tracing. The African Union coordinated with other regional partners to establish the African Medical Supplies Platform���a virtual marketplace where governments and health officials can directly purchase essential medical supplies.

What these failed predictions depict is how the global public health industry is complicit in the reproduction of what Malinda Smith calls ���the African tragedy������the uncritical epistemic industry that has long produced knowledge of African development as a monolithic and primordial tragedy. This intellectual space is generally inhabited by development economists giving credence only to internal factors like �����good��� governance and economic institutions. The African tragedy is maintained through a valence of objective and quantifiable science that obscures racists and un-reflexive discourses about the continent. Global health, just like development economists, begin their inquiries and predictions for the dissemination of COVID-19 in Africa with a set of assumptions that rely on an undifferentiated continent with no possible positive attributes to contain the spread of the virus. We saw evidence of this when two French doctors expressed how vaccine trials should take place in Africa because there are ���no masks, no treatments, no ICUs��� and ���they are highly exposed and they don���t protect themselves.���

Outrage ensued from these comments, with the head of the World Health Organization calling it a ���hangover from colonial mentality.��� Yet, how different are these comments from the underlying reasons that informed early predictions that Africa would be ravaged by COVID? When some African countries far exceeded expectations, headlines foreshadowed that the worst was yet to come. The New York Times recently proposed that the ���extra time��� that had been bought by the slow spread of the virus was not enough to bolster weak health care systems, which would soon bring about the originally anticipated number of cases for the continent.��More recently the rise in cases and COVID-related deaths in Africa has been tied to the highly transmissible South African variant of the virus. Here, again, public health officials did not anticipate that the primary factor leading to increased COVID-19 cases in Africa would be a more contagious version of the virus, once again shifting our attention from dilapidated health infrastructure to public health questions that transcend expected disaster. The disaggregated country-level data shows that most African countries continue to control the spread of the virus and mortality rates���still faring better than many wealthier nations.

An appeal to the African tragedy is never about the fundamental causes of poverty, lack of infrastructure, or corruption. These factors cannot be addressed by more aid and development interventions. Solutions to these public health problems demand a fundamental restructuring of the economic and political order. We see steps in this direction with respect to the People���s Vaccine Alliance���a coalition of governments and actors from the Global South demanding that the publicly-funded COVID-19 vaccine be considered a public good. These demands come as wealthier countries comprising only 14% of the global population have purchased 53% of the more promising COVID-19 vaccine. Countries in the Global South have taken to the WTO to demand that the WTO suspend TRIPS (the trade related aspects of intellectual property rights) to ensure that all countries have access to the requisite health resources for controlling the virus.

V.Y. Mudimbe expresses how the othering of Africa is an inexorable feature in the invention of Africa. It sustains the West���s ability to imagine itself as intellectually and morally superior. These delusions of grandeur are maintained through enterprises like global public health that discursively reinforce conditions suggesting the need for Africa to remain financially and epistemically dependent on Western countries. The forecasting of COVID-related deaths was accompanied by a call for the world to ���save Africa.��� Brain drain, land seizures for natural resource extraction, covetous intellectual property rights, and histories of medical racism, have all contributed to the conditions that would have led public health experts to predict that COVID would ravage the continent.

Many West African countries are still rebounding from the effects that the World Bank and IMF-backed Bamako Initiative wrought on their health care systems. To make these issues salient, however, is to share accountability for the African tragedy with the international community.

February 3, 2021

The liberation stories of Guinea Bissau

This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows. Funded by Shuttleworth Foundation, our fellows produce original work. They represent a diversity of regions, backgrounds and are each exploring exciting ideas related to politics, culture, sports or social movements. Siddhartha Mitter is our mentorship coordinator. Our mentors are Aida Alami, Beno��t Challand, Grieve Chelwa, Sean Jacobs, Marissa Moorman, Sisonke Msimang, and Bhakti Shringarpure.

About a dozen teenage girls in camouflage, berets, and determined gazes stand in the black and white photograph. A few of them have large guns readied at their hips. In the center of the group stands Amilcar Cabral, who is 39 at the time.

It is February 1964���one year into the armed struggle for independence in Guinea Bissau against Portuguese colonial rule. Cabral, the independence struggle���s leader, had called a conference in Cassaca for his African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) fighters to re-organize and address inter-party grievances.

The Cabral as seen in this and similar photographs, with his defiant stance, dark glasses, and signature knitted stocking cap in spite of the West African heat, would become the iconic image of the West African country. More than fifty years later, the image is still used to signify both Guinea Bissau���s victory in the 11-year independence struggle and the country���s continued hopes for the future. But what about the faces of the young women surrounding the independence hero? Directly to Cabral���s left in the image stands a round-faced, then 14-year old girl, Joana Gomes.

Today, Joana is a member of Guinea Bissau���s parliament, as a representative from the post-independence PAIGC party. For the past few years, on my frequent trips to Bissau to record the stories of women who contributed to the liberation struggle, I always make sure to pay Joana a visit. Just a couple months after I met Joana in 2018, I brought up the black and white photo on my phone to ask if she knew any of the young women in the image. She burst out loudly in her hearty laugh and said, ���My girl, of course I do. That is me!��� and pointed to herself.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes poses for a portait in front of the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes poses for a portait in front of the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.This visit, I want to ask Joana more about the moment that photo was taken. As I ride to her house in the hot backseat of a bright blue taxi, our car gets stuck in traffic. The hold-up is caused by a funeral procession snaking past the current headquarters of the PAIGC, which is still one of the largest political parties in the country. The taxi driver explains that an important member of the PAIGC and liberation fighter had died that week. I wonder why Joana is meeting me instead of attending the funeral.

Women like Joana and her sister, Teodora Gomes, a celebrated liberation fighter and a PAIGC leader, were crucial figures in the struggle for independence. Some of these women, such as Titina Sil�� and Carmen Pereira (both of whom have passed away), as well as living legends such as Francisa Pereira and Tedora, are remembered as individual heroes. But many of the women who fought during the liberation say the ideals of gender equality that they fought for did not materialize from the battle grounds into independent Guinea Bissau. The work that many of the women championed during the struggle, such as education and healthcare, were essential to winning the liberation fight, but today these services are not accessible to enough people in Guinea Bissau. Even the 2018 passage of a parity law requiring that 36 percent of members of parliament be women has so far not materialized into more formal representation. In the 2019 elections, only 14 of 102 elected members were women.

Today, many of the revolutionary fighters have passed away. But Joana and other women of the movement who are still living have important stories to tell about their contributions to the liberation effort, and their continued struggle to increase women���s political participation. They say their ideas can help bring increased equality to the country, which has had a history since independence of military coups and political instability.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.When our taxi finally makes it out of the traffic and we arrive at Joana���s house, it is mid-afternoon. Joana always (rightfully) insists on catching up on the present over food before diving into the past; today she has prepared a lunch of cafriella.

When we sit down, I show her again a digital copy of the photograph on my phone.

Joana then tells me about the long walk she had marched decades earlier, when she traveled from the rural camps near Can in the region of Quinara to Cassaca, in a liberated zone in the south of the country. The journey on foot took her at least a few days; she can���t remember exactly how many. She does recall marking her 14th birthday along the route, and a PAIGC soldier carrying her on his shoulders when she grew weary. Joana was marching for a pressing and painful reason: She wanted to confront Cabral about the death of her father, who had been shot and killed by a PAIGC soldier. She wanted to know if Cabral had indeed ordered her father���s death, as she had been told at the time, but she also admired the liberation leader and was thrilled to be in his presence.

���For the first time, I had the opportunity to be with our leader, Am��lcar Cabral,��� she said. “Imagine! I was very proud.���

Just before the photograph was taken, Joana recalls, she and the other girls were handed the army fatigues and guns to pose with. ���It was hot,��� she said of the weather. ���At that moment it was the end of the Congress, imagine how many people were inside that bush.���

I ask what she was looking at, what we cannot see on the other side of the lens. ���The future of Guinea-Bissau,��� she said. ���I don’t know if you understand. At that time we were young, with Cabral at our side; we didn’t know where we were going to go. We didn’t know what Guinea-Bissau was going to be like.���

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Women from the PAIGC party in Guinea Bissau gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36% of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Women from the PAIGC party in Guinea Bissau gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36% of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.In the vision he developed for the country, Cabral had made it clear that the fight for independence included the fight for women���s liberation from patriarchal oppression. He insisted that women hold two out of every five political positions in liberated zones; he worked to end child marriage, and increased access to education for girls.

���Cabral was a genius,��� Joana said. ���Cabral admired women a lot. He wanted Guinean women to stand out, that’s why he gave us weapons, and he titled this photo as ‘Women Combatants.’ When you saw the photograph, you saw women as combatants, because of the rifles. Cabral wanted to show that in the national liberation struggle it was not only men, who took part, but also that there were female combatants who remained on the front lines.���

When this photo was taken, neither Joana nor her friends in the photograph had actually shot the guns before. In fact, moments after the photo was taken, she and the others would board a small boat that set off for neighboring Guinea-Conakry, where PAIGC had its headquarters during the liberation struggle, and where the girls would immediately begin their education in a classroom.

���When he gave you a rifle it was not to kill anyone, it was to go into combat,��� she said. ���And that was what we did during the fight, we went to study and went back to the bush on the front line, where we stayed until we gained independence.���

After attending a school set up by PAIGC fighters in Guinea Conakry, Joana went to study nursing in Kiev, in the then-Soviet Union. She then returned to the struggle as a medic on the front lines. ���As a doctor myself, I gave medical assistance to war commanders,��� she said. ���On the front line, there are different ways of fighting.���

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.Her father, she added, would have been proud of the image of Joana in this photograph. Although her journey to Cassaca would result in her enlistment in the struggle, she did not forget the reason that brought her there.

After her father���s death, Joana said, people had told her that Cabral had ordered the killing. ���That anguished me,��� she said. ���My father was killed unjustly. It revolted me because I knew who my father was, and the value of the person he was. So when I had the opportunity to go to the Congress, my concern was to see him [Cabral] and ask him why he had my father killed?���

For several days, Joana worked alongside Titina Sila, making coffee for Cabral and others as they held meetings during the congress. Eventually Joana got her one-on-one audience. Before she could ask her question, Cabral told her that he knew her father, and before Joana could tell Cabral her father had died, Cabral turned to a fellow fighter and said Joana���s father was the country���s “encyclopedia,” and would be very important after the war. ���At that moment I started to realize the value of my father,��� Joana told me. ���Because for Am��lcar Cabral to say that my father was an encyclopedia…? I shut up until he finished. When he finished, I realized that he didn’t know that my father had been killed.���

Joana recalls breaking down crying as she interrogated a surprised Cabral about her father���s death. ���I had wanted for a long time to be in front of the person who they said killed my father,��� she told me. ���While I was crying, he was crying too. We cried together. He took his glasses off, wiped his eyes and had to concentrate, because he wanted to know the truth. So Am��lcar asked: How did he die? Osvaldo (a fellow fighter) told him that he had been murdered, Am��lcar asked him: Murdered by whom? Osvaldo replied that it was Jos�� Sanha.���

At the time, Sahna was another PAIGC fighter, and in fact one reason Cabral had called the Conference at Cassaca was to address allegations of in-fighting in the PAIGC ranks. Cabral asked if Joana had the strength to accuse Sanha to his face, she says.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Bilony Nhama (left, white shirt) is the Secretary General for the Women’s Democratic Union for the PAIGC party. She sits next to Teodora Gomes (far right), who is a hero of the country’s independence war. Here in Guinea Bissau, the women gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36 % of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Bilony Nhama (left, white shirt) is the Secretary General for the Women’s Democratic Union for the PAIGC party. She sits next to Teodora Gomes (far right), who is a hero of the country’s independence war. Here in Guinea Bissau, the women gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36 % of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.���I do,��� she recalls telling him. ���And if he didn���t do it, you will see that I will tremble. But I won���t tremble.��� When Joana first accused him, Sanha had denied killing Joana���s father and said it was his deputy, but the deputy denied that version of the story.

According to Joana, after Cassaca, Sanha, along with others who had been accused of acts of atrocity, was taken into informal custody. He was sent to the northern front, but along the way to the military base they were attacked by Portuguese forces, and the PAIGC fighters freed Sanha and others to help them fight back the attackers. Cabral had said Sanha would face justice from ���the Guinean people after liberation was won,��� said Joana. ���But when the war was finished, they had killed Cabral. And that���s how Jos�� Sanha was saved.���

Post-liberation, Sanha became a high-ranking military official in Guinea Bissau. Sanha, along with others, were able to act with impunity in the country and often used their contribution to liberation as one reason they had the right to overthrow elected leaders. Guinea Bissau has witnessed at least 10 coups or attempted coups since 1974; historians differ on the exact number. In a small country such as Guinea Bissau, Joana along with other relatives of Sanha���s alleged victims, often found themselves at government events together. Joana remembers seeing Sanha at a ceremony at military headquarters, but refusing to greet him. ���I saw him, but I stayed far away from him. I did not even go near where he was. He knew.���

Of course, it now makes sense why Joana had not attended that day���s funeral in Bissau. It was a procession for Jos�� Sanha.

The untold liberation stories of Guinea Bissau

This post forms part of the work by our 2020-2021 class of AIAC Fellows. Funded by Shuttleworth Foundation, our fellows produce original work. They represent a diversity of regions, backgrounds and are each exploring exciting ideas related to politics, culture, sports or social movements. Siddhartha Mitter is our mentorship coordinator. Our mentors are Aida Alami, Beno��t Challand, Grieve Chelwa, Sean Jacobs, Marissa Moorman, Sisonke Msimang, and Bhakti Shringarpure.

About a dozen teenage girls in camouflage, berets, and determined gazes stand in the black and white photograph. A few of them have large guns readied at their hips. In the center of the group stands Amilcar Cabral, who is 39 at the time.

It is February 1964���one year into the armed struggle for independence in Guinea Bissau against Portuguese colonial rule. Cabral, the independence struggle���s leader, had called a conference in Cassaca for his African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) fighters to re-organize and address inter-party grievances.

The Cabral as seen in this and similar photographs, with his defiant stance, dark glasses, and signature knitted stocking cap in spite of the West African heat, would become the iconic image of the West African country. More than fifty years later, the image is still used to signify both Guinea Bissau���s victory in the 11-year independence struggle and the country���s continued hopes for the future. But what about the faces of the young women surrounding the independence hero? Directly to Cabral���s left in the image stands a round-faced, then 14-year old girl, Joana Gomes.

Today, Joana is a member of Guinea Bissau���s parliament, as a representative from the post-independence PAIGC party. For the past few years, on my frequent trips to Bissau to record the stories of women who contributed to the liberation struggle, I always make sure to pay Joana a visit. Just a couple months after I met Joana in 2018, I brought up the black and white photo on my phone to ask if she knew any of the young women in the image. She burst out loudly in her hearty laugh and said, ���My girl, of course I do. That is me!��� and pointed to herself.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes poses for a portait in front of the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes poses for a portait in front of the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.This visit, I want to ask Joana more about the moment that photo was taken. As I ride to her house in the hot backseat of a bright blue taxi, our car gets stuck in traffic. The hold-up is caused by a funeral procession snaking past the current headquarters of the PAIGC, which is still one of the largest political parties in the country. The taxi driver explains that an important member of the PAIGC and liberation fighter had died that week. I wonder why Joana is meeting me instead of attending the funeral.

Women like Joana and her sister, Teodora Gomes, a celebrated liberation fighter and a PAIGC leader, were crucial figures in the struggle for independence. Some of these women, such as Titina Sil�� and Carmen Pereira (both of whom have passed away), as well as living legends such as Francisa Pereira and Tedora, are remembered as individual heroes. But many of the women who fought during the liberation say the ideals of gender equality that they fought for did not materialize from the battle grounds into independent Guinea Bissau. The work that many of the women championed during the struggle, such as education and healthcare, were essential to winning the liberation fight, but today these services are not accessible to enough people in Guinea Bissau. Even the 2018 passage of a parity law requiring that 36 percent of members of parliament be women has so far not materialized into more formal representation. In the 2019 elections, only 14 of 102 elected members were women.

Today, many of the revolutionary fighters have passed away. But Joana and other women of the movement who are still living have important stories to tell about their contributions to the liberation effort, and their continued struggle to increase women���s political participation. They say their ideas can help bring increased equality to the country, which has had a history since independence of military coups and political instability.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.When our taxi finally makes it out of the traffic and we arrive at Joana���s house, it is mid-afternoon. Joana always (rightfully) insists on catching up on the present over food before diving into the past; today she has prepared a lunch of cafriella.

When we sit down, I show her again a digital copy of the photograph on my phone.

Joana then tells me about the long walk she had marched decades earlier, when she traveled from the rural camps near Can in the region of Quinara to Cassaca, in a liberated zone in the south of the country. The journey on foot took her at least a few days; she can���t remember exactly how many. She does recall marking her 14th birthday along the route, and a PAIGC soldier carrying her on his shoulders when she grew weary. Joana was marching for a pressing and painful reason: She wanted to confront Cabral about the death of her father, who had been shot and killed by a PAIGC soldier. She wanted to know if Cabral had indeed ordered her father���s death, as she had been told at the time, but she also admired the liberation leader and was thrilled to be in his presence.

���For the first time, I had the opportunity to be with our leader, Am��lcar Cabral,��� she said. “Imagine! I was very proud.���

Just before the photograph was taken, Joana recalls, she and the other girls were handed the army fatigues and guns to pose with. ���It was hot,��� she said of the weather. ���At that moment it was the end of the Congress, imagine how many people were inside that bush.���

I ask what she was looking at, what we cannot see on the other side of the lens. ���The future of Guinea-Bissau,��� she said. ���I don’t know if you understand. At that time we were young, with Cabral at our side; we didn’t know where we were going to go. We didn’t know what Guinea-Bissau was going to be like.���

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Women from the PAIGC party in Guinea Bissau gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36% of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Women from the PAIGC party in Guinea Bissau gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36% of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.In the vision he developed for the country, Cabral had made it clear that the fight for independence included the fight for women���s liberation from patriarchal oppression. He insisted that women hold two out of every five political positions in liberated zones; he worked to end child marriage, and increased access to education for girls.

���Cabral was a genius,��� Joana said. ���Cabral admired women a lot. He wanted Guinean women to stand out, that’s why he gave us weapons, and he titled this photo as ‘Women Combatants.’ When you saw the photograph, you saw women as combatants, because of the rifles. Cabral wanted to show that in the national liberation struggle it was not only men, who took part, but also that there were female combatants who remained on the front lines.���

When this photo was taken, neither Joana nor her friends in the photograph had actually shot the guns before. In fact, moments after the photo was taken, she and the others would board a small boat that set off for neighboring Guinea-Conakry, where PAIGC had its headquarters during the liberation struggle, and where the girls would immediately begin their education in a classroom.

���When he gave you a rifle it was not to kill anyone, it was to go into combat,��� she said. ���And that was what we did during the fight, we went to study and went back to the bush on the front line, where we stayed until we gained independence.���

After attending a school set up by PAIGC fighters in Guinea Conakry, Joana went to study nursing in Kiev, in the then-Soviet Union. She then returned to the struggle as a medic on the front lines. ���As a doctor myself, I gave medical assistance to war commanders,��� she said. ���On the front line, there are different ways of fighting.���

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau (March 6, 2019) – Joana Gomes (center) instructs women cleaning the local hospital in Fulacunda, Guinea Bissau. Gomes, who was a medic on the frontlines during the independence war, donated beds to the hospital as part of her campaign. Image credit Ricci Shryock.Her father, she added, would have been proud of the image of Joana in this photograph. Although her journey to Cassaca would result in her enlistment in the struggle, she did not forget the reason that brought her there.

After her father���s death, Joana said, people had told her that Cabral had ordered the killing. ���That anguished me,��� she said. ���My father was killed unjustly. It revolted me because I knew who my father was, and the value of the person he was. So when I had the opportunity to go to the Congress, my concern was to see him [Cabral] and ask him why he had my father killed?���

For several days, Joana worked alongside Titina Sila, making coffee for Cabral and others as they held meetings during the congress. Eventually Joana got her one-on-one audience. Before she could ask her question, Cabral told her that he knew her father, and before Joana could tell Cabral her father had died, Cabral turned to a fellow fighter and said Joana���s father was the country���s “encyclopedia,” and would be very important after the war. ���At that moment I started to realize the value of my father,��� Joana told me. ���Because for Am��lcar Cabral to say that my father was an encyclopedia…? I shut up until he finished. When he finished, I realized that he didn’t know that my father had been killed.���

Joana recalls breaking down crying as she interrogated a surprised Cabral about her father���s death. ���I had wanted for a long time to be in front of the person who they said killed my father,��� she told me. ���While I was crying, he was crying too. We cried together. He took his glasses off, wiped his eyes and had to concentrate, because he wanted to know the truth. So Am��lcar asked: How did he die? Osvaldo (a fellow fighter) told him that he had been murdered, Am��lcar asked him: Murdered by whom? Osvaldo replied that it was Jos�� Sanha.���

At the time, Sahna was another PAIGC fighter, and in fact one reason Cabral had called the Conference at Cassaca was to address allegations of in-fighting in the PAIGC ranks. Cabral asked if Joana had the strength to accuse Sanha to his face, she says.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Bilony Nhama (left, white shirt) is the Secretary General for the Women’s Democratic Union for the PAIGC party. She sits next to Teodora Gomes (far right), who is a hero of the country’s independence war. Here in Guinea Bissau, the women gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36 % of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.

Bissau, Guinea Bissau (March 8, 2019) – Bilony Nhama (left, white shirt) is the Secretary General for the Women’s Democratic Union for the PAIGC party. She sits next to Teodora Gomes (far right), who is a hero of the country’s independence war. Here in Guinea Bissau, the women gather for an event on International Women’s Day, two days before legislative elections where a new law required that 36 % of candidates be women. Image credit Ricci Shryock.���I do,��� she recalls telling him. ���And if he didn���t do it, you will see that I will tremble. But I won���t tremble.��� When Joana first accused him, Sanha had denied killing Joana���s father and said it was his deputy, but the deputy denied that version of the story.

According to Joana, after Cassaca, Sanha, along with others who had been accused of acts of atrocity, was taken into informal custody. He was sent to the northern front, but along the way to the military base they were attacked by Portuguese forces, and the PAIGC fighters freed Sanha and others to help them fight back the attackers. Cabral had said Sanha would face justice from ���the Guinean people after liberation was won,��� said Joana. ���But when the war was finished, they had killed Cabral. And that���s how Jos�� Sanha was saved.���

Post-liberation, Sanha became a high-ranking military official in Guinea Bissau. Sanha, along with others, were able to act with impunity in the country and often used their contribution to liberation as one reason they had the right to overthrow elected leaders. Guinea Bissau has witnessed at least 10 coups or attempted coups since 1974; historians differ on the exact number. In a small country such as Guinea Bissau, Joana along with other relatives of Sanha���s alleged victims, often found themselves at government events together. Joana remembers seeing Sanha at a ceremony at military headquarters, but refusing to greet him. ���I saw him, but I stayed far away from him. I did not even go near where he was. He knew.���

Of course, it now makes sense why Joana had not attended that day���s funeral in Bissau. It was a procession for Jos�� Sanha.

Feminism, sovereignty, and the pan-African project

Image via Region Refocus.

Image via Region Refocus. This article is part of our Reclaiming Africa���s Early Post-Independence History series from Post-Colonialisms Today (PCT), a research and advocacy project of activist-intellectuals on the continent recapturing progressive thought and policies from early post-independence Africa to address contemporary development challenges. It is adapted from a webinar of the same name, which you can watch here.

Sara Salem is Assistant Professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science and part of the Post-Colonialisms Today project, for which she undertook research on the linkages between feminism, sovereignty, and the pan-African project. In anticipation of the PCT special issue of CODESRIA next year, she spoke with Anita Nayar about some of her most interesting findings, from the internationalist conceptions of sovereignty in the early post-independence period to the contributions and contestations of African feminists to the pan-African project. Sara also recently released her book, Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt The Politics of Hegemony.

Anita NayarI���m excited to talk with you about the research you���ve undertaken for Post-Colonialisms Today; your analysis explores how sovereignty in Africa���s immediate post-independence period was necessarily conceptualized as a pan-African and internationalist project, which offers many lessons for today. You also trace, through archival materials, the contributions of African and South feminists to the conception of pan-Africanism, breaking with Western feminists to conceptualize national liberation as fundamental to gender justice. Can you begin unpacking this rich analysis with how early post-independence African governments conceptualized sovereignty?

Sara SalemThere are differences among African governments in how they conceptualized sovereignty, but I think we can point to some overlaps in how sovereignty as a whole was thought of and contested. What strikes me is their expansive idea of sovereignty, one that went beyond formal independence or formal decolonization and that included political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions. Sovereignty did not refer to sovereignty over territory alone, but also over economic structures and social life. We can see this expansive definition of sovereignty at play when we look at events like the Afro-Asian Conference at Bandung, during which governments focused on the importance of industrialization and diversifying export trade by processing raw materials before export, which points to an awareness that African countries were in a position of dependency to global capital because of their reliance on exporting of raw materials.

Importantly, sovereignty was not just seen as national, or as a project of decolonizing the nation, but also international. Many states aimed to disrupt the structure of the ���colonial international,��� which is a term Vivienne Jabri coined to describe how the international sphere is still permeated by imperialism and colonial power, and transform what sovereignty meant for all nations everywhere. This is in contrast with the colonial spectrum of sovereignty where some nations were seen as sovereign and others as potentially sovereign. Think here of the categories of mandates or protectorates. As Kwame Nkrumah noted, ���the essence of neo-colonialism is that the state which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.��� So regaining control over the structures of economic and political life meant intervening in and transforming a global arena that was still colonial in nature.

Anita NayarWhat are some of the policies through which post-independence states challenged the ���colonial international��� and secured their sovereignty through regional and international cooperation?

Sara SalemMany of these policies hinged on the belief that regionalism and internationalism were crucial to creating a more just world. Thinking back again to the Afro-Asian Conference at Bandung , we see particular themes emerge that connect economic sovereignty to forms of regional and international connectivity and highlight the urgent need for cooperation within the global South. Policies that reflected this transnational understanding of sovereignty included the creation and sharing of technical expertise, research, and development; the establishment of international bodies to coordinate economic development (for example the Organization of African Unity); and self-determination in terms of economic policy. These policies served to create connections between countries in the Global South, as well as to promote a particular form of independent economic development that came to characterize many post-independence states across Africa. While many of these programs used the language of socialism, they largely implemented what could be called state capitalist policies, but it is still useful to note the underlying ethos of economic sovereignty and the notions of connectivity and cooperation.