Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 136

March 8, 2021

Bill Gates and his technofix dream for the planet

Image credit Jean-Marc Ferr�� for UN Photo via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Jean-Marc Ferr�� for UN Photo via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. This post is part of our series ���Climate Politricks.���

On February 16, mega billionaire Bill Gates appeared on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah to discuss his forthcoming book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, launched on the same day. In it, Gates claims to describe the technologies that are already helping to reduce emissions, which ���breakthrough technologies��� may be needed for the climate crisis, who is working on them, and what kind of plan we will need to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions. Fresh from being ���Mr Fix-It��� for the COVID-19 pandemic, the world���s most visible philanthropist is now offering an encore performance for the climate catastrophe.

In the interview with Noah, Gates emphasized that the solution for the climate crisis is to drive ���innovation faster than it would normally take place,��� and to have the involvement of ���more high-risk companies.��� Indeed, when it comes to problems like climate change, the COVID pandemic, global health or pretty much anything, Gates seems to believe that technology fixes will offer magic bullet solutions. This ideology���it is indeed an ideology���is termed ���solutionism��� by Evgeny Morozov. In its simplest form, Morozov writes, solutionism ���holds that because there is no alternative (or time or funding), the best we can do is to apply digital plasters to the damage. Solutionists deploy technology to avoid politics; they advocate ���post-ideological��� measures that keep the wheels of global capitalism turning.���

In the area of climate change, one suite of such proposals that will keep the wheels of global capitalism turning���and in which Gates has enthusiastically been investing���is geoengineering. Geoengineering comprises of large-scale controversial schemes to intervene in the earth���s oceans, soils, and atmosphere in attempts to manage the effects of climate change. Many of these schemes are extraordinary���such as blocking the sun to stop temperature increases, increasing the whiteness of clouds to reflect sunlight back into space, and sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere with industrial-scale fans. In order to have any impact on the climate, they would have to be done on a planetary scale so the potential risks are many: they range from destabilizing weather patterns, creating droughts and floods in Africa and South America, and acidifying the ocean, to polluting the atmosphere and locking the world into unstoppable management of the atmosphere. Many proposals for removing CO2 from the skies require huge amounts of energy, chemicals, infrastructure, and land in size equivalent to several countries. Yet crazy, inequitable, and dangerous as geoengineering may seem, it is currently been embraced by polluting industries and increasingly some governments as a supposed ���solution��� to an off-kilter warming world.

Gates has poured many millions of dollars in funding into geoengineering research. As Dru Jay and Silvia Ribeiro from the ETC Group have written, he is a major investor in Carbon Engineering (CE), a Canada-based direct air capture firm. He has also channeled funds from his personal fortune into the Fund for Innovative Climate and Energy Research (FICER), which supports research into solar geoengineering���schemes to block sunlight from reaching earth or reflect it back into space. Notably he bankrolls David Keith, a scientist who is proposing to spray tens of thousands of aerosols such as sulfur dioxide, into the stratosphere, to block sunlight before it reaches the earth. Keith���s current research project is the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx), an attempt to conduct an open-air test of solar geoengineering technology by spraying various aerosols into the stratosphere from a balloon. A first experimental test of equipment related to this project has been proposed in northern Sweden, and an advisory group to SCoPEx is currently ruling on whether to approve of the balloon test while major Swedish�� (and international) environmental groups and Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg have voiced their opposition. Scientific climate modelling has shown that injecting aerosols into the stratosphere on a large scale may disrupt the ozone layer and ecosystems. As Thunberg tweeted about the wrong-headedness of the Gates-backed balloon experiment, ���A crisis created by lack of respect for nature will most likely not be solved by taking that lack of respect to the next level.���

In addition to its obviously dangerous effects, what is important to know about geoengineering is that those most invested in its development are the very companies responsible for causing the climate crisis: fossil fuel companies and those who invest in them. According to a report from The Centre for International Environmental Law (CIEL), oil companies have been investing in and supporting geoengineering since the 1970s. Along with Gates, the oil company Chevron and Murray Edwards, a financier of the Canadian tar sands, are also investors in Carbon Engineering. That is not all: Gates himself has investments in fossil fuels. As Silvia Ribeiro and Dru Jay write, when Gates gave a talk about solutions to climate change in 2010, he had been a major shareholder in Canadian National (CN) Railroads for at least four years, shipping crude oil from Canada���s tar sands. Tar sands operations are among the dirtiest and most environmentally destructive forms of fossil fuel extraction in the world. They generate 17 percent more carbon emissions than conventional oil. Through Cascadia Investment Fund, which Gates controls, and through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates has gradually increased his holdings of CN stock to 16.7% of the company. According to Ribeiro and Jay, That means that in 2019, Gates��� Cascadia and the Foundation received around US$190 million in dividends alone. His shares in CN Rail alone are worth US$10.9 billion.

Then there is Microsoft, the company Gates founded and in which he has still has about US$70 billion in stock. Microsoft has also invested heavily in oil companies, including Exxon Mobil, Shell, Chevron, and BP. Despite a recent pledge to be ���carbon negative by 2030,��� the company���s cloud services web site advertises ���oil and gas solutions��� that will ���increase drilling hit rates,��� ���improve reservoir production��� and ���extend asset life cycles.��� Ribeiro and Jay note that the company is in fact enabling oil companies to extract more oil.

It therefore comes as no surprise that Gates��� approach to climate change is to champion the technofixes that will enable the fossil fuel machine to continue pumping more oil. He is after all personally invested in the infrastructure that relies on their success. It is also unsurprising given the pervasive technophilia of our time, that even influential personalities like Trevor Noah whom many look to for critical analysis on global issues, would so willingly engage with Gates, offering him a platform for his climate solutionism. It would do well for us to remember that Gates is not a scientist, or a public health expert. He is a mega-billionaire who made his fortune avoiding government regulations and dominating competitors with monopolistic practices. His money is now being channeled toward a wide range of projects that are deeply unpopular among many in the global South. Beyond climate technologies, Gates is investing in controversial ���extinction��� technologies of gene drives, a biotechnology tool to re-engineer natural populations. This is ostensibly being developed for malaria prevention, but is being vehemently resisted by social movements in West Africa where a Gates funded project wants to test out their tools. He has also been the principal funder of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, an agricultural program started in 2006 which claims to be working for small-scale farmers but, in fact, promotes high-tech market-based industrial agriculture in Africa. A report in 2020 revealed that the program had failed in a number of ways. Rather than improving farmer���s livelihoods, many went into debt in order to pay for the high costs of commercial seeds and synthetic fertilizer. In response to Noah���s query about the injustice of Africans having to suffer the impact of the West���s production of climate crisis, Gates suggests they grow seeds that ���can grow in the hotter temperatures and that are more productive.��� The seeds he proposes are not the seeds that farmers are already using, but genetically modified seeds and hybrids, such as those provided by agribusiness giant Bayer-Monsanto under the Water Efficient Maize for Africa project that pushes agribusiness interests into African farming. Groups like the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa have been fighting against the growing corporatization of agriculture and for people���s alternatives, such as agroecology.

Mainstream media has been all too willing to uncritically engage Bill Gates��� preferred image as a well-meaning nerdy philanthropist in a cuddly sweater���offering him countless opportunities to share his ���expertise��� and promote his technofixes. It���s time to look beyond the rhetoric of this billionaire philanthrocapitalist and listen to those who realize that climate change will only be ���solved��� when we begin by identifying its primary cause: capitalism.

For more information about geoengineering, please visit: https://www.geoengineeringmonitor.org/

Beware of martyrs

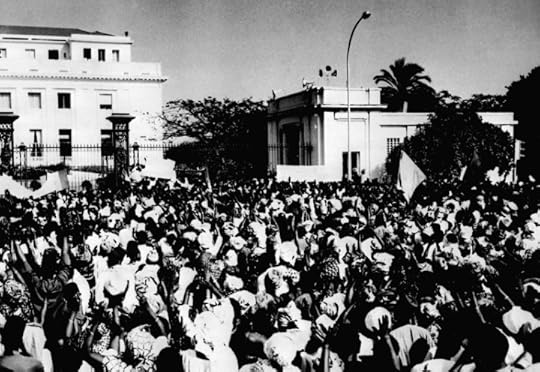

Protesters in front of the presidential palace in Dakar, 1968.

Protesters in front of the presidential palace in Dakar, 1968. In these early days of March 2021, there is a sense of d��j�� vu in Senegal���bringing us back to a time when the single-party rule was enshrined in the law.

Throughout the country, not a day has gone by since February, without the police raiding activists from the PASTEF-Patriots opposition party, members of the Front for a Popular Anti-imperialist and Pan-African Revolution (FRAPP) movement, and various citizens engaged in the struggle against Macky Sall���s authoritative regime.

Ousmane Sonko, Senegal���s leading opposition figure and head of PASTEF, recently lost his parliamentary immunity after an ad-hoc commission composed almost exclusively of government majority MPs voted for its lifting on February 26. Earlier in the month, a beauty salon employee had accused him of ���rape and death threats.��� On March 3, while on his way to court to answer the investigating judge���s summons, Sonko was arrested on and placed in police custody for ���disturbing public order.���

That was the last straw setting the country ablaze. Despite the curfew imposed for the past two months, clashes between demonstrators and the police continued late into the night. The Dakar police prefect, Alioune Badara Samb, was caught on camera calling to charge ���everyone,��� including the press.

It feels like a 50-year leap back. To a time when, to ���crush the opposition to its most elementary expression,��� in President Macky Sall���s words, was a matter of absorbing into the government coalition the most moderate opponents or plotting against the most recalcitrant. To a time when President Leopold Sedar Senghor called upon the army and the ruling single party���s militias (���heavy lifters��� in plainclothes backing up the police) to subdue demonstrators.

Reading historian and former student leader Abdoulaye Bathily describing the May 1968 mobilization appears as relevant as ever:

Tear gas bombs and truncheons got the better of the boldest workers. In response to police brutality, the workers, along with students and the lumpenproletariat, attacked vehicles and stores, many of which were set on fire. The clashes with the police were particularly intense in working-class neighbourhoods.

In addition to the hundreds of wounded, and Senegalese and international students excluded or expelled from the country, the May-June 1968 repression led to the death of several young people, including Hanna Salomon Khoury at Dakar University and Moumar Sy at Pikine High School. Forced into the army following the 1971 student demonstrations, student Al Ousseynou Ciss�� was killed by Portuguese colonial troops at the border with Guinea-Bissau.

Two years later, in May 1973, the revolutionary philosopher Omar Blondin Diop, sentenced for ���undermining state security��� to three years in prison in March 1972, was murdered in Gor��e prison. For the more significant part of their days, detainees could not leave their cells for more than an hour a day, and regularly subjected to arbitrary solitary confinement. Blondin Diop was found dead after a month spent in the ���disciplinary dungeon.��� The investigating judge in charge of the case, Moustapha Tour��, discovered in the prison register that the activist had fainted the week before the announcement of his death. He indicted two suspects, but before he had time to arrest a third was replaced by another judge who closed the case.

Simultaneously, the Senegalese government launched a major media campaign to make this state crime look like a ���suicide by hanging������in the press first, before publishing the White Book on the Suicide of Oumar Blondin Diop, a document claiming to ���set the record straight��� yet riddled with historical approximations and untruths. Only a minority believed the official thesis. Blondin Diop���s death sparked riots, recalling the insurrectional climate of May 1968. Then-all-powerful Minister of the Interior, Jean Collin, quickly summoned the deceased���s father. ���I cannot return your son���s body to you,��� he confided. ���Otherwise, there will be blood. So, my men are going to bury him.��� The burial was expeditious, in the sole presence of Blondin Diop���s father and younger brother. For a year, armed forces would surround the philosopher-militant���s grave to prevent any gathering in his memory���a tradition maintained every May 11th until the 1990s.

In this perspective, recent statements from Cape Manuel prison director Khadidiatou Ndiouck Faye are extremely worrying. Commenting on activist Guy Marius Sagna���s detention conditions, she affirmed that ���he called them thieves and a gang of scoundrels.��� She added, ���I then asked my men to take him to solitary confinement���There, the rule is that the inmate commits suicide.��� In the absence of irrefutable evidence proving the contrary, any political prisoner who dies in custody must be considered a victim of murder. Several young Senegalese have already fallen prey to bullets of the state.

Beware of martyrs. A regime that blows on the embers fans the flames.

March 5, 2021

Feminism(s) in Africa

Girls walking together outside Yomelela Primary School, Khayalitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. Image credit Karin Schermbrucker for UN Women via Flickr CC.

Girls walking together outside Yomelela Primary School, Khayalitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. Image credit Karin Schermbrucker for UN Women via Flickr CC. On Monday, the 8th of March, International Women���s Day is set to be celebrated across the globe. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has announced its 2021 theme as ���Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world.��� Declaring that the world has to end the marginalisation of women and girls, UNDP administrator Achim Steiner writes that to do so, ���we must break down the deep-seated historic, cultural, and socio-economic barriers that prevent women from taking their seat at the decision-making table to make sure that resources and power are more equitably distributed.���

The tricky thing about commemorative periods centred around an ongoing cause for justice and liberation���whether it���s something like a black history month, women���s month, or Pride month���is that the interests, politics and concerns of the affected groups are usually presented as being uniform and without contradiction. Steiner���s statement is a good way to illustrate the internal tension within the movement for women���s liberation���there are those who think that female representation in decision-making authorities (through individuals) is significant enough for effecting change, and there are those who think that the fundamental change comes by challenging those power structures from the outset.

It is the women belonging to the latter, more radical tradition, who actually paved the way for International Women���s Day to be observed in the first place. Its roots originate from the Socialist Party of America organizing a “National Women���s Day” in 1909 to honor a 1908 garment workers strike, and inspired by this, at the International Socialist Women���s Conference the following year, a group of German socialists (including Clara Zetkin, Luise Ziets, Paula Thiede and K��te Duncker) proposed an International Women���s Day. As Cinta Frencia and Daniel Gaido note for Jacobin, for these women, the adoption of the day ���meant promoting not just female suffrage, but labor legislation for working women, social assistance for mothers and children, equal treatment of single mothers, provision of nurseries��and kindergartens, distribution of free meals and free educational facilities in schools, and international solidarity.���

But, as women continue to wage these struggles, it is important to look beyond the North American and European history, and to recognize the contributions of feminists from elsewhere since as Rama Salla Dieng emphasizes for Africa Is a Country series ���Talking back: African feminisms in dialogue���: ���There has been a deliberate erasure of generations of women from Africa, The Caribbean, India and Latin America because they contest mainstream feminism so their voices should also be heard, the specificities and nuances of their diverse struggles acknowledged.��� So this week on AIAC Talk, we���re interviewing�� Professor Shireen Hassim, Rosebell Kagumire and Rama Salla Dieng. Shireen, a South African academic, is the Canada 150 Research Chair in Gender and African Politics at Carleton University, Rosebell is a Ugandan writer, award-winning blogger and pan-African feminist, and Rama is a Senegalese writer, activist and lecturer in African and International Development at the Centre of African studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Recognizing that feminist theory and practice on the continent is varied and multivocal, we would like to talk to each of them about their experience working through different topics and issues, whether its exploring how women���s liberation organization���s in South Africa become co-opted into the ruling power structure, the intersection of land rights struggles and gender rights struggles in Francophone Africa, or how women across the continent are using digital platforms to organize. What are the connections between these different fronts of struggle? How are women making them? And what would an African feminist agenda include for the world being remade in the time of COVID-19?

Catch the show the show on Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week���s episode explored African film and TV in the age of streaming. For that one, we had Dylan Valley, Sara Hanaburgh and Tsogo Kupa talk to us about how big streaming platforms like Netflix are trying to gain a foothold on the continent, and with Mahen Bonetti we discussed the African film festival in the digital age.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but as usual, best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

The fight against descent-based slavery in Mali

Image credit Direct Relief on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Direct Relief on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. On September 1, 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, four anti-slavery activists were murdered in western Mali for their work against descent-based slavery���a form of slavery considered hereditary, which in its worst forms manifests in forced labor without pay, denial of education, and civil rights abuses. This practice has a long history in colonial and contemporary Mali and West Africa where people with alleged ���enslaved ancestors��� live at the bottom of the social ladder, facing discrimination and social exclusion on a daily basis. As forced migrants and newcomers escaping wars or economic deprivation, having been sold into slavery or not, their ancestors were ascribed the status to be treated as a slave by those in power.

In 2017, the anti-slavery group, Gambana, was formed to fight systematic discrimination and violence mainly among the Soninke, an ethnic group in several West African countries. Activists denounce the anachronistic and demeaning use of the word ���kome��� (slave) and the worst forms of exploitation this gives way to in some settings. Their protest generated a violent backlash: since 2018 more than 3,000 Malians with ascribed ���slave status��� have fled slavery-related violence in the Kayes region. Activists and members of the movement have also been attacked and are threatened in several localities in the Kayes region and beyond, yet the state and global community have remained largely silent.

Slavery existed in the Sahel before the Transatlantic Slave Trade and endured beyond its abolitions. In the 19th century, Kayes was a major transit zone of slave caravans and experienced an expansion of internal slavery through war and conflict. French colonial authorities abolished the internal slave trade in 1905 as they searched to recruit liberated slaves for forced labor. They soon turned a blind eye on the continuation of what they called ���domestic slavery,��� pretending it had simply transformed into salary contract work thanks to the colonial legislation. Indeed, they feared that true abolition would destabilize local slavery-based economies and prevent full colonial control of labor and taxation. Thus, descendants of those enslaved continued to inherit ���slave status��� and their labor continued to be controlled by the local historical ruling class with the complicity of the colonial state, a system that allowed historical hierarchies to persist to present day.

Despite the lack of implementation of the 1905 abolition decree on the ground, some formerly enslaved managed to take their destinies into their own hands, escaping a violent institution to live freely in independent communities. Although the region experienced successive waves of emancipation in the colonial and postcolonial era, descent-based slavery continued under disguised forms of kinship, marriage, and adoption/fosterage. Today, poverty and discrimination continue to exclude Malians with ascribed ���slave status��� from social mobility, as highlighted by the Benbere blog campaign #MaliSansEsclaves. Both past and present, some victims of descent-based slavery have found in migration a way of escaping slavery.

Whether living in France or Mali, as first, second, or third generation immigrants, transnationally imposed social ���embargos��� are used to punish those who try to change this social order. For example, when youth in the diaspora want to marry outside of the ���right��� social group, their relatives back home can be punished severely for such a transgression and will very likely be denied access to vital village resources (water, land, market, shops, etc.), which can lead to forced displacement.

Slavery has never been criminalized in postcolonial Mali. In 2012, Mali passed a law criminalizing human trafficking. However, plans to pass a law criminalizing descent-based slavery in 2016 failed to materialize; the Malian government appears unable or unwilling to act in support of those affected by descent-based slavery. Many officials claim that victims are not ���slaves,��� but participants in ���traditional��� practices. As long as descent-based slavery is not criminalized in Mali, prosecuting slavery-related abuses will prove difficult.

A protective legal framework and awareness campaigns are also crucial to support these communities to escape the vicious cycle of poverty and exploitation. Forced displacement and re-settlement are onerous processes which may increase the vulnerability of already vulnerable populations, especially girls and women. In such cases, new forms of servitude strongly overlap with the legacies of historical slavery. These displaced populations often live in precarious conditions because of marginalization and stigmatization in new host communities. This precarity is amplified by the politics of land access as managed by local elite groups, but also the degradation of land in the fragile ecological Sahel zone particularly affected by climate change.

Our research on Slavery and Forced Migration (SlaFMig) in the Kayes region will analyze and map the history of slavery-related protracted displacements as strategies of resistance. We propose concrete measures to redress this long-term crisis by training legal professionals and advocating for the passage of a law that criminalizes descent-based slavery, as well as informing local and national government how to efficiently manage protracted displacements of people with ascribed ���slave status.��� We also campaign for more education aimed at the younger generation on the history of and resistance to slavery in Mali. Finally, the project aims at supporting displaced communities to achieve sustainable living by identifying their specific needs and helping them to access aid for microcredit projects.

March 4, 2021

A female Secretary-General will not change how the UN works

Photo by Matthew TenBruggencate on Unsplash

Photo by Matthew TenBruggencate on Unsplash There has been a lot of talk within civil society organizations about why the next Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN) should be a woman. Their argument is that since the UN was formed 75 years ago, and there has not been a single female Secretary-General, it does not augur well for an organization that is committed to gender equality and that purports to represent all of the world���s people.

The first term of the current Secretary-General, Ant��nio Guterres, ends this year. Simone Filippini, the president of the Netherlands-based non-profit Leadership4SDGs, who has been campaigning for a woman to succeed Guterres, says that the race to have a female at the helm of the UN ���is not about achievements or the possible lack thereof of Guterres��� but is about ���the principle that deep into the 21st century, it is unacceptable to have a few member states wheel and deal to pick one of the most important jobs in the world.”

Filippini is referring to the fact that the selection of the UN Secretary-General is carried out by only the five permanent members of the UN Security Council: the US, Britain, France, Russia, and China. This means that the person chosen as Secretary-General is usually one who will serve the interests of these five permanent members���someone who will not openly defy their policies, even if they go against the ideals of the UN or if they contravene international law. This explains, for example, why the UN Security Council can impose sanctions on a tiny country like Eritrea but did not impose any sanctions on the US or Britain for waging a war in Iraq in 2003.

UN Secretary-Generals are typically selected from countries that are viewed as economically or politically weak���countries that do not have a big say in the running or funding of the UN and that will not pose a significant threat to the US, the biggest contributor (22 percent) to the UN���s budget, or to the four other permanent members of the UN Security Council and their allies.�� Typically, they come from small countries with little political muscle or military might. (The current UN Secretary-General is from Portugal; his two predecessors were from South Korea and Ghana.) Hence it is unlikely that we will see any time soon a UN Secretary-General from a country like Iran or even from the world���s second most populous country, India.

Given the current geopolitics, where power and wealth are concentrated in a few countries, both male and female UN bosses have limited space to push forward their agenda. Even if a woman is nominated and appointed as the UN Secretary-General, we are not likely to see significant reforms in the gender arena because such a woman would be reluctant to bring about major reforms for fear of being labelled too feminist or losing the support of influential UN member states. Being a political appointment, she is not likely to offend her own government or governments that supported her appointment. She is not likely to introduce major shifts in the work culture of the organization either. Hence, the mere presence of more women at the top of the UN hierarchy will not automatically make the UN a more woman-friendly environment.

Most female UN bosses do not come into the organization with strong activist or feminist credentials; most are selected because they appeal to certain member states of the UN, particularly the five permanent members of the Security Council.�� These ���political appointments,��� like that of the former head of the UN Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat), Anna Tibaijuka, an agricultural economist whose appointment was supported by Sweden and other Northern European countries (even though she is Tanzanian), are, therefore, constrained by how many feathers they can ruffle within and outside the UN, where consensus is often required to bring about change, and where taking hard line positions is viewed as undiplomatic. It would, for example, be considered extremely undiplomatic and impolite for a female head of a UN agency to urge a Saudi Arabian leader to give women in his country more freedom or to remind the president of US, the so-called ���leader of the free world,��� that weapons he sold to a certain country had been used to kill innocent women and children.

Secretary-Generals who take strong positions on certain issues do so only after they have the nod and approval of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. One would be hard-pressed to find a UN Secretary-General condemning Russia or China for human rights violations or condemning the US for failing to prevent the spread of COVID-19. To survive in this male-dominated bureaucracy, female heads of agencies try hard not to be seen as having an agenda or to be too vocal about issues that might offend certain powerful or influential countries. Some try even harder not to be seen at all, preferring to keep a low profile until their term ends. Then there is also the fact that female bosses are held at a higher standard than male bosses. The UN is full of highly incompetent male managers, but one does not get to hear about their failures.

The most notable exception was Mary Robinson, the former Irish president who served as the UN���s High Commissioner for Human Rights between 1997 and 2002. As high commissioner, Robinson made an official visit to Tibet in 1998, which was probably not viewed kindly by China, an influential member of the UN Security Council that has been resisting Tibetans��� calls for autonomy from China for decades. She also criticised the US for its continuous use of capital punishment, and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, she accused the George Bush administration of violating human rights in its so-called ���war on terror.��� Robinson had been an unconventional leader even when she was president; she was the first head of state to visit Rwanda after the genocide there in 1994 and also visited conflict-ridden Somalia in 1992 during its civil war, at a time when the country was considered a ���no-go-zone.���

However, Robinson���s fiercely independent���some might say defiant���posture worked against her in 2001, when she was condemned for allowing some Arab delegations at the World Conference Against Racism, held in Durban, South Africa, which she presided, to equate Zionism with racism. As a result of this and her other actions perceived to be against US, Israeli and other Western interests, she was eventually forced out of her UN job, most likely because of pressure from the US government, and replaced with the much more ���diplomatic��� Sergio Vieira de Mello, who later served as Kofi Annan���s special representative in Iraq, where, unfortunately, he was killed in a bomb attack shortly after his appointment.

Yet, no other global body has worked as hard to ensure gender equality globally. After the UN was founded, it established a Commission on the Status of Women that is dedicated exclusively to gender equality and the advancement of women. And in 1979, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women. The UN also has an entire agency���UN Women���devoted to women. UN Secretary-Generals have also pushed the gender agenda on the world stage. In 2008, at the launch of a global UN campaign to end violence against women, the then Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, stated: ���There is one universal truth, applicable in all countries, cultures and communities: violence against women is never acceptable, never excusable, never tolerable.���

Yet, despite the gender-sensitive rhetoric, gender equality within the corridors of the UN remains a mirage, and sexual and other types of harassment of women are rampant. An internal UN survey in 2018 found that one-third of the UN staff members surveyed had been sexually harassed, and only one out of every three employees who were harassed took any action against the perpetrator for fear of retaliation. About one in 10 women reported being touched inappropriately; a similar number said they had witnessed crude sexual gestures.

Another survey by the UN Staff Union found that sexual harassment was one among many abuses of authority that take place at the UN. Results from the survey, which were released in January 2019, showed that sexual harassment made up about 16 percent of all forms of harassment. Forty-four percent of those surveyed said that they had experienced abuse of authority; of these, 87 percent said that the person who had abused his or her authority was a supervisor. Twenty percent felt that they had experienced retaliation after reporting misconduct.

Despite anti-sexual harassment and whistleblower protection policies, the UN does little to protect victims of sexual harassment or those who blow the whistle on wrongdoing. In a recent case at UNAIDS, a woman was fired after she went public with her sexual harassment case against the deputy head of the organization. In her case, the head of the UN agency failed to protect her.

My own experience at UN-Habitat showed me that it matters little in the UN if the head of an agency is a woman; in fact, it was the female head of the agency who failed to protect me when I made a complaint about being bullied and intimidated by my male supervisors. When I was eventually forced out of the organization, I knew then that women who take principled stands against corruption, harassment, bullying, and other forms of misconduct will not be protected, not even by their female bosses. My subsequent attempts to have my case resolved by the next female Executive Director of UN-Habitat hit a similar brick wall. There was virtually no attempt to look into my complaints; on the contrary, the people I had accused were given promotions, and my case was filed and forgotten. I suppose I naively expected a female head of a UN agency to be more sympathetic to my case, but as I found out, the UN is structurally built in such a way that the unhealthy and extremely hierarchical and competitive (male) culture of not tolerating dissent prevails.

The UN need not be a hostile place for women, but given its structural inadequacies, including an all-powerful Security Council that makes decisions based on the whims of its permanent members, and its misogynistic work culture that punishes competent and diligent women, it is unlikely that a female head will be able to go against the grain. For the UN to become more inclusive and gender-sensitive, it must change its work culture, and correct the power imbalances among UN member states that dictate whose voices and opinions matter. This is an extremely tall order that no woman���or man���at the helm of the UN can change overnight.

Vaccine apartheid

Nurse Nosipho Khanyile speaks with a patient inside the "Red Zone" at the special COVID-19 Field Hospital in Nasrec, Johannesburg. Image credit James Oatway for IMF Photo on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Nurse Nosipho Khanyile speaks with a patient inside the "Red Zone" at the special COVID-19 Field Hospital in Nasrec, Johannesburg. Image credit James Oatway for IMF Photo on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The coronavirus crisis in South Africa is far from over despite falling case numbers in recent weeks. The virus has claimed more than 50,000 lives, and many health experts predict a devastating third wave. Complicating matters is a new coronavirus mutation known as n501, which threatens to upend South Africa���s vaccination plans.

Unprecedented scientific collaboration has expedited the development of the new vaccine candidates, but patents protecting the bottom lines of the pharmaceutical companies have hampered efforts to manufacture vaccines at scale. Meanwhile, the US and Western Europe have hoarded limited supplies through bilateral negotiations with Big Pharma. Developing nations in the Global South have been left behind.

The vaccination gap between rich and poor nations grows starker by the day. According to Global Justice Now, a grassroots campaign in the UK that focuses on justice and development in the Global South, 10 countries account for approximately 75% of the COVID-19 vaccines administered worldwide. About 130 countries���accounting for about 2.5 billion people���are yet to administer a single dose. This artificial scarcity creates another global crisis, making room for the virus to mutate and potentially grow more contagious and vaccine-resistant.

As Anna Marriott, a health policy manager at the global anti-poverty organization Oxfam, argued this month:

South Africa has been here beforeThe world is in a race to reach herd immunity to get this disease under control, save millions of lives and get our economy going again. This is a race we have to win before new mutations render our existing vaccines obsolete. Yet the pursuit of profits and monopolies means we are losing that race���We urgently need to lift the veil of corporate secrecy and instead have open-source vaccines, mass produced by as many vaccine players as possible, including crucially those in developing countries.������

In 2001, the Treatment Action Campaign and the Congress of South African Trade Unions called for worldwide protest against pharmaceutical companies; drug patents were barring the South African government from importing low-cost, generic, HIV medications. While litigation held up acquisition of cheap medicines, hundreds of thousands of South Africans died of AIDS-related illnesses. A report by the Medical Research Council found that, in the year 2000, 40% of the deaths of people age 15-49 in South Africa were related to HIV.

Activists in South Africa organized for years against pharmaceutical profiteering and their own government���s HIV-denialism, ushering in new local and global policy to allow for a broad introduction of antiretroviral therapy.

Now, with the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in South Africa nearing 1.5 million, some of these same networks and organizations are fighting for access to coronavirus medications. Their contentions remain largely the same as they were in 2001: price gouging, internationally enforced Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (known as TRIPS), the backing of pharmaceutical companies by wealthy nations, and a weak public healthcare system that lacks government transparency and accountability.

Fatima Hassan is a social justice activist in South Africa. She worked as a human rights lawyer in the 1990s, litigating against the government and pharmaceutical companies on behalf of people with HIV/AIDS. In July 2020, as history began to repeat itself, Hassan founded the Health Justice Initiative to address inequity in health and medicine access.

���It���s playing out again,��� she says. ���A lot of us who were in the access to medicines movement then are now trying to get people to understand what���s at stake and the gravity of the situation.���

Hassan continues:

The road to a global disasterNever trust drug companies��� benevolence. So that ”no profit pledge” by AstraZeneca, we said: ”Interrogate that. Look at the sublicensing agreements. Make sure there���s data transparency.” We said: ”You���re going to have price variations, you���re going to segment markets��� . They���re not going to respond to this from a public health [or] epidemiological perspective. The vaccines will go to the people who are the wealthiest. They���ll test vaccines in our country but decide if they���ll come into our country or not���” This is exactly what happened with HIV/AIDS.

In an open letter to world health officials���including Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to President Joe Biden���Cape Town Archbishop Thabo Makgoba and the People���s Vaccine Campaign of South Africa warn ���we are on the road to a global disaster.���

The letter argues:

[The] dire shortage of vaccine supplies is not due to any inherent technological limitation in scaling up production, but rather a seemingly deliberate decision to not allow production scale up to what the global pandemic requires���And while we acknowledge that there is insufficient manufacturing capacity, right now, in the world, a combination of investment in immediate capacity scale up ��� and a concerted effort to facilitate technology transfer could help rapidly solve this problem.

The broader Southern Africa region is battling a new and highly contagious strain of the coronavirus. Health workers, reports M��decins Sans Fronti��res (MSF), ���are currently struggling to treat escalating numbers of patients with little prospect of receiving a vaccine to protect themselves or others from the virus.��� According to Christine Jamet, MSF���s director of operations, ���While many wealthy countries started vaccinating their health workers and other groups nearly two months ago, countries such as Eswatini, Malawi, and Mozambique���which are struggling to respond to this pandemic���have not received a single dose of vaccine to protect the most at-risk people, including frontline health staff.���

But no country on the African continent has been hit harder by the pandemic than South Africa. The South African economy is more stable than that of Malawi or Mozambique, which allows South Africa to buy vaccines directly from the pharmaceutical companies. But it has done so in a market system that prices these medicines exorbitantly.

South Africa���s healthcare system is also stronger than the rest of the region, but doctors, nurses, and other care workers have been pushed to their breaking point. Sasha Stevenson is the head of health at Section27, a South African public interest law center and social justice organization:

Our health system is already creaking under the weight of COVID, because it was creaking under the weight of HIV and [tuberculosis] beforehand. And we���ve now got TB numbers going through the roof, because we can���t maintain all of these programs at once. And we���re being asked to pay huge sums of money for vaccines that are needed to keep us and the rest of the world safe.

We have a health system that���s [been] struggling for a long time. So, the idea of a rollout that requires everyone in the country to register on an electronic database, and then potentially come back for two shots when sometimes clinics are far away from people, and we struggle to get ambulances to rural areas in life-or-death emergencies, is very daunting.

Claire Waterhouse, MSF���s regional advocacy coordinator, explains: ���healthcare workers are exhausted. There was just significantly less human resource capacity to deal with the second wave when it did arrive. A lot of them had been sick in the first wave.��� Meanwhile, MSF is working to dispatch mobile units of doctors and nurses to coronavirus hot spots to ensure the sick receive the medical attention they need. But with frontline healthcare workers������rom physicians to ambulance drivers to clinic cleaners���denied access to vaccines, that job has become much more difficult.

���It���s really hard here right now to see developed countries being able to roll out these vaccines and people getting vaccinated before we���ve even managed to put one needle in one arm,��� Waterhouse says. ���And it���s so frustrating and so heartbreaking for our healthcare workers, who [just want] some protection. We���re really hoping that when the vaccines roll out, that will give them a layer of confidence, which will hopefully help them to deal with what is frankly an inevitable third wave.���

Hassan puts things more bluntly: ���Everybody���s bullshitting us.���

Pharma in the driver’s seat���The research and development of this vaccine was publicly funded and conducted at Oxford University,��� Global Justice Now says in a statement: ���The vaccine should have been a global public good���openly licensed to allow as many manufacturers as possible to make it.���

But the (often secret) agreements between pharmaceutical companies and a particular country allow Big Pharma to set different prices for different markets. AstraZeneca, despite claiming a ���no-profit��� pledge during the pandemic, is charging South Africa $5.25 per dose and Uganda $7 per dose. The European Union, by contrast, has paid just $2.16 per dose.

South Africa, meanwhile, received its first vaccine supply of 1 million AstraZeneca shots February 1, and it may already be too late to use them, amid concerns the vaccine is ineffective against the new n501 strain of virus.

With the rollout of AstraZeneca stalled, South Africa is turning to Johnson & Johnson, which signed an agreement with Aspen Pharmacare���s South African subsidiary in November 2020 to produce up to 300 million doses. Those doses, however,���despite being manufactured in South Africa, will primarily be exported as part of Johnson & Johnson���s global inventory.

Initially, South Africa wasn���t going to receive any of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, but Johnson & Johnson has now agreed to secure nine million doses for the country. This deal may include an agreement by South Africa to speed up regulatory approval as well as a no-fault compensation scheme in which South Africa, rather than the pharmaceutical company, takes responsibility for any vaccine-related damages.

South Africa has been the site of clinical trials for numerous vaccine candidates, including AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and Novavax, sharing its data with the international community. Despite this collaboration, Hassan says that the pharmaceutical companies ���are in the driver���s seat��� when it comes to dictating the terms of the sale of the vaccines and any partnerships with local drug manufacturers to scale up production.

Your life or their patentsFor years, South African civil society has been pushing to overhaul of South Africa���s patent system to make use of the legal safeguards available through TRIPS. Waterhouse explains:

Intellectual property and patents are not new topics in South Africa. We don���t want to repeat the same kinds of issues that we had with [antiretroviral drug treatment for HIV] and which we are now seeing with the pandemic. It���s depressing that we���re still fighting this fight, and really concerning that access to medicine has not evolved beyond who can afford them. Because that���s really what it boils down to. It���s that old line of profits over people, profits over patients.

While activists organize locally to revamp South Africa���s patent laws, the governments of wealthy nations could reprioritize global health over the profits of pharmaceutical companies. As Stevenson observes, ���Governments have power over pharmaceutical companies that they don���t often exercise. And now is the time to exercise that power. Now is the time to stop being beholden to pharmaceutical companies, particularly given the really enormous levels of public funding.���

To ensure profits are not prioritized over public health, activists are organizing on several fronts, pushing for local reforms while supporting calls for a TRIPS waiver at the World Trade Organization (WTO). South Africa and India have proposed waiving patents and other intellectual property (IP) restrictions related to COVID-19 drugs and vaccines for the duration of the pandemic. Internationally, these steps could be critical for generic drug manufacturers to scale up vaccine production.

A small group of wealthy nations���including the EU, the UK, the US, Japan, Canada, and Australia���has blocked the waiver proposal so far, claiming that limiting the patents would stifle future innovation. Research by Public Citizen, however, indicates most of the leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates are ���using a spike protein technology developed by the US government��� through grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Indeed, most medical innovations are taxpayer-funded collaborations between the public and private sectors, with pharmaceutical companies typically spending 20% or less of their revenues on research and development.

���It���s really interesting the way that the scientists have been talking for the last year about how wonderful it���s been to collaborate on development and share information and to move as quickly as possible,��� Stevenson points out. ���The moment that it comes to production, and there���s billions of dollars in profits to be made, there���s suddenly no such collaboration���Instead, these manufacturing companies are twiddling their thumbs.���

As the open letter to Fauci makes clear, healthcare advocates are also calling on the US and the UK to pressure pharmaceuticals to share their technology and know-how, commit to low pricing and break open manufacturing capacity to scale up production of the vaccine. Because the US is a co-owner of the vaccine co-developed by Moderna and the NIH, it has significant legal rights to make those demands. The Biden administration could also utilize the Defense Production Act to increase vaccine manufacturing.

Activists in the US and other wealthy nations could help force governments to support mass vaccine production and distribution. While Biden has reversed the course of the previous administration by reengaging with the World Health Organization and the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access initiative (known as Covax, a voluntary, if insufficient, project to buy vaccines for developing countries), he has not backed the waiver request from South Africa and India, nor has he made any promises to use the US government���s leverage with Moderna to share its science and technology.

As a matter of global solidarity, the US has a responsibility to support an equitable production and distribution of vaccines. But as the virus mutates in frightening ways, it is also in our self-interest.

As WHO cautions: None of us will be safe until everyone is safe.

March 3, 2021

The political economy of biofuels in Mozambique

Moses Siambi looks at sweet sorghum varieties being tested for biofuel production by Eco-Energia at Ocua, Mozambique. Credit Swathi Sridharan (ICRISAT) CC BY-SA 2.0.

Moses Siambi looks at sweet sorghum varieties being tested for biofuel production by Eco-Energia at Ocua, Mozambique. Credit Swathi Sridharan (ICRISAT) CC BY-SA 2.0. This post is part of our series ���Climate Politricks.���

Mozambique has been labeled by pro-capitalist actors as one of the most ���promising��� African countries for an economically successful biofuels sector. The country���s apparent underutilization of its agricultural landscape, and combined abundance of low-cost labor, aligns perfectly with the biofuels investment profile devised by international institutions such as the World Bank. Since the global financial crash of 2007, Mozambique���s biofuels industry has rapidly grown, a trajectory received enthusiastically by political leaders, development agencies and corporate actors.

European governments are largely responsible for the global spread of the biofuels industry in the past decade, having set ambitious mandated targets for renewable energy to tackle crises surrounding climate, food, energy, and development. The politically loaded term ���agrofuel,��� however, has surfaced referencing the intense social and political relations arising in biofuel production. With voluminous evidence demonstrating the various harms of industrialized biofuel production, it would seem that the purpose of this ���green��� fuel, first and foremost, is to purify the collective conscience of the West.

Broadly, the dominant narrative justifies sustainability assertions by incorporating crops��� end use only, ignoring the aggregate climate impact that occurs in the production process. This generates new frontiers for capitalist expansion through the ���fa��ade of market environmentalism.��� The primary environmental consequence of biofuels presented by academics is the increase in greenhouse gases, that is the carbon debt, that occurs through several avenues during generation, such as lost carbon sequestration potential of original forestry cleared, and carbon leaks upon decaying of wood products. Although these insights are significant, the prevailing preoccupation with greenhouse gas emissions inadvertently succumbs to Western-centric macro concerns���it is consumers in the global North that have been promised carbon reductions from switching to renewables. While this outcome does affect the population globally, albeit rather disproportionately, it is local biodiversity loss and degradation of resources that will have the greatest effect on communities in regions of biofuel expansion.

Large-scale land acquisitions are justified through assertions that only ���marginal,��� ���idle,��� or ���unused��� areas will be allocated to biofuel production. Yet, it has been exposed that land is flippantly deemed marginal if it is not utilized in a neoliberal sense (exploited for commercial profit). Under the current system, top-down, constructivist categorizations intentionally simplify landed social relations, through the ���invisiblization��� of local perceptions of communal land. In Mozambique, consistent with other African contexts, most lands classified as idle actually are being used, but in more traditional ways. Further to this, it is often the most vulnerable of groups, such as women and refugees, that rely on these lands to grow crops and graze cattle. The biofuels industry thus legitimizes and greenwashes acts of land-grabbing, to the detriment of some of the most marginalized in society.

Massive tracks of land are handed to corporations, causing entire communities to be displaced, leading to food insecurity, resource deprivation, social polarization, and political instability. Through ���publicly-sponsored private accumulation,��� financially elite actors enhance their control over global resources, transforming socio-ecological elements with deep-seated cultural and symbolic value, into one-dimensional commodities defined by exchange value only. Given the foundational role of ancestral agricultural land in many civilizations, these practices constitute vast spiritual and cultural loss. The displacement process has been aptly labelled ���accumulation by dispossession,��� highlighting how the needs of capital are met by disrupting local communities. Awareness of nation states��� facilitative role in these processes is vital. The Mozambican state consistently fails to uphold its proclaimed sovereignty, cultivating enabling conditions for elitist interests, enjoying close relationships with external investors, and acting as broker in transactions.

Biofuel projects are publicized as positively contributing to consumption of local goods and services, income, employment, productivity, and technological transfer. Exemplifying the extent that job creation is overestimated and/or overplayed, one project in Mozambique had pledged a generation of 2,600 jobs, yet created fewer than 40 full-time positions. Highly asymmetric power relations supplant the need to adhere to any such promises. This causes many to be pushed out of legitimate employment and toward the informal economy, where rights, conditions, and opportunities are bleaker. The capital-intensity of corporate, mass-scale biofuel production means that many of Africa���s investor hotspots are unable to organically absorb labor expelled from the land���s original use, creating societies of so-called ���surplus people.���

Land tenure historically tells us that the likelihood of communities economically benefiting from these opportunities is limited. Although contracted work is desirable for some, on occasions where job creation does materialize, it is often seasonal, unreliable, involves lower wages, and poor conditions. The more fundamental matter, though, is the subordinate position that workers (the ���lucky ones��� in the biofuels landscape) will find themselves in, through their subjection to wage labor relations and production requirements. That employment can be used as a legitimation tactic for biofuels projects, despite such a dismal track record in this area, is indicative of a distinct lack of accountability, attributable once again to the distorted power relations in the industry.

Increasingly aware of biofuels��� socially destructive path, many have advocated for normative solutions to address these challenges. These include the development of social frameworks and adaptation strategies, intensification of production, or the adoption of technical interventions such as accountability, transparency, and free, prior, and informed consent. However, change advocated without any fundamental paradigmatic alterations will necessarily be inadequate. Such positions are consistent with powerful orthodox actors, who regard native systems as backward, and continue to reject any philosophy of social reproduction that is not underpinned by accumulation and private property. To insist that rural populations should acquiesce to the current system of global, commercialized, agricultural production crucially forecloses the opportunity for the self-determination and political autonomy of rural groups.

The win-win narrative upheld by mainstream actors, who claim that biofuels can green Western consumption habits and simultaneously assist development efforts in the global South, must be scrutinized. Far more work is needed to identify the cultural, spiritual, ecological, and social ramifications as the industry burgeons into unprecedented territory, and these investigations must place rural communities at their center.

Wangari Maathai���s environmental Bible

Image via the Center for Neighborhood Technology on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Image via the Center for Neighborhood Technology on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. March 3 marks the celebration of Africa Environment Day. Since 2012, this day is jointly commemorated with Wangari Maathai Day, in recognition of the life and legacy of the late Professor Wangari Maathai (1940���2011). With relentless energy and great vision, she devoted her life to protecting the natural environment and promoting sustainable development. Among many other accolades, in 2004 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of her trailblazing work.

Maathai is widely recognized as a hugely influential environmental, political, and women���s rights activist. The Green Belt movement, which she founded, works with local communities, especially women, to conserve the environment and improve livelihoods. Since its foundation in 1977, the movement has planted over 51 million trees in Kenya alone.

Maathai also was a scientist���the first woman to gain a PhD (in veterinary anatomy) in East and Central Africa, and the first female chair of a department at the University of Nairobi. In 1982 she was forced to leave the university. She was welcomed back only in the final stage of her life and was appointed as chair of the newly founded Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies.

For Maathai, activism and academic work were not separate worlds. A recent book about her, Radical Utu, by Besi Brillian Muhonja, demonstrates that she was an organic intellectual and thinker, who developed critical ideas about indigenous African knowledges, democracy, gender equality, development, and social justice.

A part of her work, often overlooked, was how she creatively engaged with religious traditions, including Christianity and the Bible. Admittedly, her stance was somewhat complex. On the one hand, Maathai was critical of Christianity for its connection to colonialism, and for its continuing negative environmental impact. Christian mission, in her words, performed ���acts of sacred vandalism��� through which the sacred groves and trees of African communities were desacralized. This has allowed for a culture of exploitation of natural resources, resulting in soil erosion and environmental devastation. Maathai sought to reclaim and promote the worldview and spirituality of her own Kikuyu people and of other African indigenous traditions in which nature is considered sacred.

On the other hand, Maathai was and remained a Catholic, who claimed to believe in God and to be ���a good student of Jesus Christ.��� Among the inspirations of her faith were the American civil rights movement with its prophetic black Christian leadership, Latin American liberation theology with its radical support for those who are marginalized, and Christian environmental initiatives. The Bible was not only a source of personal inspiration but also a resource for enhancing environmental awareness. Doing so, Maathai recognized that most Kenyans, and indeed many Africans, today are Christian; they are familiar with the Bible and ascribe authority to it. Thus, in the Green Belt movement���s workshops with local communities, Maathai used many stories from the Bible that offer guidance on the way in which humankind is supposed to treat the earth and its resources.

Maathai���s book Replenishing the Earth is full of references to biblical texts, ranging from Genesis to Revelations. She creatively weaves them into her argument for a spirituality that helps humans to live in harmony with the natural world. The book also narrates an anecdote about Maathai preaching at a church. At that occasion, she used the symbol of the cross to encourage the congregation to plant trees. After all, she suggested, the cross was made of wood���a tree had been cut in order for Christ to bring salvation. Planting a tree was a way for Christians to express their gratitude to God.

For Maathai, identifying as Christian and reading the Bible was not at odds with reclaiming African indigenous religions and cultures. She considered these traditions to be compatible, as they both offered ���spiritual values for healing ourselves and the world.��� However, she does suggest that this requires a re-reading of the Bible and the Christian tradition, dissociating them from their colonizing and exploitative elements. In that sense, Maathai makes an important contribution to current debates about decolonizing Christianity in Africa.

Foregrounding Maathai���s use of the Bible as part of her community activism is of critical importance today. Kenya, Africa, and the world at large are facing huge environmental challenges. Maathai presents a model of creatively using faith-based resources to engage religious communities in protecting the environment. With about 60% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa identifying as Christian, Maathai���s environmental Bible can be an effective resource for promoting environmental respect and stewardship.

March 2, 2021

The Xhosa literary revival

Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash

Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash When cooped-up critics and writers connect on social media, their conversations often demand more room. Such was the case in my correspondence with Mphuthumi ���Mpush��� Ntabeni, which migrated to various messenger platforms before finding its stride on email. We read each other���s books; we related them to other books; we grew an unlikely discussion of Catholic conversion narratives from a deep love of South African intellectual history. Talking to Ntabeni, it is anyone���s guess how one body of texts will lead to another. He is a literary wanderer par excellence, and yet he is far from unmoored. Born and raised in Queenstown, in South Africa���s Eastern Cape, he now resides in Cape Town, where he has continued to nurture a far-ranging knowledge of Xhosa history and culture. His first novel, The Broken River Tent, reconstitutes the perspective of a real-life 19th-century chief named Maqoma, of the amaRharhabe branch of amaXhosa who lived west of the Kei River, and were thus among the first African people to encounter white settlers when they arrived on the Cape���s Eastern shores. Ntabeni���s book uses retrospective narration framed by present-day dialogue to offer a Xhosa point of view on that violent encounter, which gave rise to the century-long period of the Xhosa or Cape Frontier Wars (1779-1970) against the British and the Boers.

Published by South Africa���s Blackbird Books imprint in 2018, The Broken River Tent won the debut category of the University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English the following year. It is not an easy book to slip into: more of a series of conversational and historical collisions than a self-propelling plot, it pairs Maqoma with a contemporary figure named Phila to parse topics ranging from the relevance of psychoanalysis for Africans to the structure and material composition of frontier wagons. One could be forgiven here for recalling fellow South African J.M. Coetzee���s early novels (In the Heart of the Country, especially), owing not least to Phila���s ���hyperanalytical��� disposition. Ntabeni���s style, however, is marked not by the stymying force of endless self-reflection, but by the exuberance of a mind eager to unfurl its abundant stores. A single paragraph of the book moves rapidly from Steve Biko to Soren Kierkegaard to the biblical Job, with its dialogue lubricated by cheap whiskey. This is Ntabeni���s approach to fiction in a nutshell: high-octane and expansively informed.

This interview took place on Google Docs between Baltimore and Johannesburg, where Ntabeni has just settled into a four-month writer���s fellowship at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study, housed at the University of Johannesburg. With lockdowns still in place internationally and his work on a third novel beginning in earnest, it seemed like the perfect time to present his ideas to the AIAC readership. What follows has been edited for clarity and flow.

Jeanne-Marie JacksonI���m glad we are finally getting around to this, Mpush���your novel was one of the first I read when the pandemic lockdowns started. I know that it���s intended to be part of a trilogy, so I���ll jump right in by asking you what it is that appeals to you about that format for this project. Are you intentionally in dialogue with other famous African trilogies? (Achebe, Mahfouz, and Dangarembga all come to mind, though Okri is perhaps the closest to The Broken River Tent in its merging of spiritual and historical concerns). Or is there some intrinsic quality of the trilogy that you see your story as making use of?

Mphuthumi NtabeniWell, I���m happy to be here and finally do this with you. Thanks for inviting me. The trilogy was not my original idea. Come to think of it, even writing a book was never my original intention. I was just eager to know about my own history and so I started researching it on my own. I knew very little about it because we had not really been taught it at school or at home. When I thought I had done enough and was even beginning to form my own opinions about it, I started asking myself how I could make other people aware of it, especially the ones directly affected by it, like myself. That is when the idea of the book came to mind. I didn���t want to just translate the material I found in the archives. I wanted to find a way of making that history live, resurrect it if you like, so that non-professional historians like myself would also be interested in it. There was also the issue of gaps in historical facts I found and wished to fill by what I call an ���informed imagination,��� that is, by inserting psychological and emotional energy into known or unknown historical facts without betraying their true spirit. In that way the genre of historical fiction chose me.

As for why this became a plan for a trilogy in particular, I realized at some point that I had accumulated too much historical data in my research. The task of tackling it through a narrative form became formidable. Then, one cold December day, while we were walking on the High Street of Edinburgh, my wife wanted to feed our daughter who was only a month old then. So, we left the snowy streets and quickly dashed into a restaurant for a meal, to give my wife also a chance to breastfeed the baby. As we sat there, looking through the window, I realized that we were sitting across from one of the places Tiyo Zisani Soga used to stay in while studying at the University of Edinburgh. (Note to readers: Tiyo Soga was a 19th-century South African intellectual best remembered for translating the bible and John Bunyan���s Pilgrim���s Progress into isiXhosa). Then the format of how to handle my research material came as a bolt of lightning to me. I would need to divide it into three thematic units: war, religion, and politics. The protagonist for the war section became obvious to me when I recalled that out of nine wars the amaXhosa fought with the British colonial government over 100 years, at least four of them were led by Maqoma, and he was physically present in five. This is why I used his biographical facts as the skeleton of my first book. Soga, the first Xhosa person to be educated in what we call Western education as a reverend, was also the obvious candidate for the religious section, which I���m currently busy with. And S.E.K Mqhayi (1875-1945), the poet, essayist, biographer, and newspaper editor during the foundations of political resistance that led to the foundation of the ANC, also became an obvious choice for me. I wish to call the trilogy ���The River People,��� and The Broken River Tent is its first installment.

My writing influences are myriad. In fact, I still consider myself an avid reader who acquired an opinion about the events of our history more than I consider myself to be a writer. I like that it is mostly my readers who make me aware of the literary influences on my writing, more than I do myself. I recall being surprised when a brilliant interviewer asked me if I considered The Broken River Tent to be magic realism. I honestly had never thought of it that way, but as I began doing so I saw her point, especially in the section when Maqoma gets a visit from Nxele in Robben Island. I suspect it is also the reason why you see Ben Okri’s influences on my writing, perhaps more with The Famished Road than any other of his works. The Chinua Achebe reference is understandable since we both write about the impact of colonialism on native culture and history. I also learnt a wonderful trick from him of titling books with lines from popular poets.

Jeanne-Marie JacksonI want to get back to Soga, so hold that thought. First, though, it also strikes me that you try, in The Broken River Tent, to approximate the cadences and ���feel��� of Xhosa speech as well as including passages of isiXhosa. This deliberate Africanization of English is often cited as one of Achebe���s key postcolonial innovations. Can you say a bit more about what this technique entailed, for you?

Mphuthumi NtabeniI guess no one can bring forth an African voice in literature without adopting the African traditional style of speaking in proverbs and all. I don���t know how Achebe wrote his characters in his head, but I was deliberate in hearing Maqoma���s voice in Xhosa in mine, before translating it into English. This is why his English is different to that of other people in the novel, like Phila who has been educated in Western ways. I wanted Maqoma���s voice to have raw Xhosa intonations. I felt lucky in the sense that Xhosa is a singing language, so I wanted to translate that for non-Xhosa speakers so that they might be able to understand how the language, like most ancient and classical languages, sings. My sister says I Xhosalized English, and I find this phrase endearing. I was also happy that someone at least noticed the effort I tried to make with Maqoma���s voice. Much of it is acquired from a Xhosa imbongi style of praise singing. Mqhayi has been very helpful in my learning to acquire that voice. I also learn a lot from the Gaelic ancient languages, like Irish shamans and Scottish Picts, my other learning obsessions. I find a lot of commonality in how they infuse English with traits of their traditional languages, which is what gives them distinct and unique ways of speaking English mixed with their mother tongues. I���m afraid I���ll never stop bragging about the richness of the Xhosa language if you don���t stop me���

Jeanne-Marie JacksonBrag away! You fill me with regret that I didn���t stick with Xhosa beyond an intro course. And I think that you are onto something important, here, about the significance of your role as a specifically Xhosa novelist to the fractious tradition of South African literature broadly. Black South African writing is most often associated with the urban, the cosmopolitan, and the ���modern,��� from the trope of ���Jim Comes to Joburg��� in the mid-20th-century; through the ���Drum generation��� as it flourished in the 1960s; to the Soweto novels of the 1970s and 1980s; and right up to post-apartheid figures like Phaswane Mpe and K. Sello Duiker. And yet, as you suggest with your reference to Tiyo Soga, there is a much longer and less widely read history of culturally differentiated South African writing; it isn���t simply ���English,��� ���Afrikaans,��� and ���Black,��� as one often hears. I am thinking even of A.C. Jordan here, whose 1940 novel Wrath of the Ancestors, as you well know, deals not so much with overt questions of racial or national identity but with intra-cultural dynamics. The historical tensions within ���Xhosaness��� are also something you explore in The Broken River Tent. My question, then, is this: has South African literature reached a point where there is room for more prominent literary experimentation in a wider range of constituent traditions? What, in other words, is the relationship between Mpush Ntabeni the Xhosa novelist and Mpush Ntabeni the South African one?

Mphuthumi NtabeniThis is an interesting question that I doubt I���ll be able to answer, but I���m going to give it a go. I think all writing cultures that write in English, not as a mother tongue, or perhaps it is better to say those whose background is not necessarily Anglo-Saxon, have a love/hate relationship with the language. Though they understand its usefulness as a lingua franca, they tug on the leash of its dominance and hegemony. They also sometimes find it to be an insufficient means to express their own philological roots. I am not even talking about the language politics here, which Ng��g�� wa Thiong���o argues convincingly even though proper solutions still elude him also. I am talking about the sheer frustration of someone who has been raised and nurtured in say, German or Xhosa, with a much more comprehensive variety of words and phrases to transmit the spirit of their thoughts precisely and succinctly in their own language, and which often are not translatable to English. (Note to readers: The character of Phila in TBRT was educated in South Africa and Germany.) When writing The Broken River Tent, whenever I encountered that challenge, I chose to use the Xhosa or German phrase alongside what I regarded as a weak explanation of its meaning in English. I don���t see why I should rob words/phrases of the richness of their meaning just to serve the monolinguist.

To answer your question properly, though, the genius of the English language, why it became so popular, I think, is because it is adaptable. It gleans words from various languages to enrich its vocabulary. There���s no reason why that adaptability should only be limited to Germanic, Frank, and Latin languages when English is also spoken in Africa and Asia. South African literature therefore has no choice but to adapt also, it must grow its African roots, and those cannot only be limited to Afrikaans when this country has 11 official languages. Of course, the attitude of some gatekeepers within the publishing industry is not completely convinced about this. They still come with tendencies of recognizing only occidental trends as seeds of progress. But they���ll be compelled by the ruthless hand of necessity.