Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 137

March 1, 2021

Police killings: how does South Africa compare?

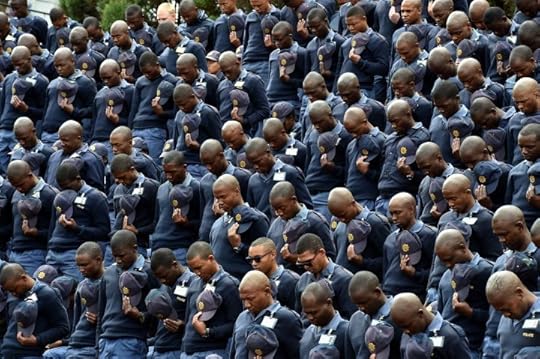

South African Police Service Commemoration Day, Pretoria. Credit GovernmentZA via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

South African Police Service Commemoration Day, Pretoria. Credit GovernmentZA via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. South African police killed someone every 20 hours last year on average, according to statistics released late last year by the South African government���s Independent Police Investigative Directorate (Ipid). The 424 deaths reported represent a slight decrease from 2018/2019 when 440 people died ���as a result of police action.���

Since the killing of Collins Khosa and Nathaniel Julius, there has been increased attention to police violence in South Africa���in particular the often-brutal enforcement of the COVID-19 lockdown. But the report, which covers the 12-month period ending in March 2020, contains little data on police violence during the lockdown which began on March 26th���capturing more-or-less business as usual for South African policing. Ipid���s raw numbers can be useful, but alone they tell us little about how the police compare to their counterparts around the globe. Are South African cops especially murderous or just par for the course?

Back in September 2019, I attempted to provide some comparative perspective on South African police violence. Based on what was then Ipid���s most recent 2017/2018 data alongside data from the Washington Post and independent research initiative Mapping Police Violence (MPV) on US police violence in 2018, I found that South African police killed roughly three times as many people per capita as American police. (If you use the Post���s data, which only counts police shootings, the precise number is 3.25; if you use MPV���s data, the number is 2.95.)

Though at the time I found that number eye-opening, I did not expect the attention it garnered on social media, among activists, and more recently fact-checkers. Realizing the stat had legs and that new Ipid data would be released shortly, it felt like a fitting time to provide a more comprehensive look at more than just at one year of data. So, what do the numbers say?

Between 2014 and 2019, police killed about 452 people each year. Taken over the total population of South Africa, those 452 killings represent an average of 7.96 deaths per one million people. During that same period, US police killed about 1092 people each year for a per capita average of 3.37 deaths per one million people, according to MPV���s dataset. A quick glance at this larger data set reveals that 2017/2018���the year I selected for my original comparison���represents a highwater mark for police killings in South Africa. As such, it is necessary to revise that original claim. Rather than three times, South African police kill on average slightly less than two and a half times (2.36) as many people per capita as American police do.

In the interest of decentering the US, let���s look at how South Africa compares to another country. Data sets from Botswana, Nigeria, and Kenya are unfortunately hard to come by. Brazilian journalists have been working on a national database, but have faced obstacles from state governments. However, after an outcry about police killings of indigenous people, the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) has gathered data on police brutality dating back to 2000. The CBC���s dataset shows that the Canadian police kill about 33 people per year, an average of 0.92 deaths per one million people. In comparison, South African police kill slightly more than eight and a half times (8.64) as many people per capita as Canadian police.

Admittedly, the US and Canada have lower levels of inequality and different histories than South Africa. But neither American nor Canadian police can be said to be paragons of virtue. Both have faced charges of abuse for decades. What does it say about South African society that the police are substantially more violent than those in the US or Canada?

Is it possible to even make compare these contexts? The fact-checkers at Africa Check, a South African version of Snopes, seem to think not. In their look at my original claim, the faithful fact-checkers (with some advice from former SAPS officer, now researcher Andrew Faull) dubbed it ���unproven��� on the grounds that the data sets in question have different methodologies. It is true. Ipid, MPV, and the CBC have different methodologies. Ipid counts deaths as a result of suicide during police confrontations, deaths as a result of injuries suffered during ���attempts to evade the police,��� and deaths as a result of non-police-initiated vehicle collisions. The MPV and the CBC do not. But how much, if at all, do these discrepancies change the overall picture?

The short answer is: not much. Because the vast majority of deaths are a result of police shootings, the number of deaths that would be excluded under MPV���s criteria are few and far between���just over 15 per year. Excluding those incidents causes South Africa���s overall rate of police killings per capita to drop only marginally from 7.96 on average to 7.78. The RSA/US ratio drops from 2.36 to 2.32. The RSA/Canada ratio drops from 8.64 to 8.47. But the overall story remains the same: South African police kill on average slightly less than two and a half times as many people as American police and roughly eight and a half times as many people as Canadian police do.

Those readers who have made it through this morass of numbers and calculations must be wondering: what is the point of this sort of analysis? One might argue that only accurate information can give us a sense of the scale of police brutality. This is true, but we should be cautious about wading too deeply into the statistical weeds. After all, stats are not straightforward vessels of truth, though they often pretend to be. Though Ipid���s statistics provide our best window onto police violence in South Africa, there are serious questions about the directorate���s capacity and independence. The MPV and the CBC have the benefit of being independent, but their methodologies depend on deaths appearing in local media and are not infallible. Rather, Ipid, MPV, and the CBC���s numbers are very likely undercounts.

For those interested in shifting the conversation on policing in South Africa, stats can be fickle tools. There are some who will seize on the gap between stats��� aura of facticity and their actuality to sideline abolitionist arguments without engaging their substance. Stats and comparisons can be useful as interventions into existing narratives about the nature of South African society. But abolitionists should remember that the real challenge lies in re-working those existing narratives through a vision about what South African society could be. Struggles in the US, Canada, Nigeria, Kenya, Brazil, and elsewhere will be useful in developing that vision.

But ultimately, as Sohela Surajpal recently pointed out, the work of re-working those narratives must engage with and draw on the experiences, sensibilities, and philosophies of everyday South Africans. This will take time and considerable collective effort. It is work that begins with the conviction that what was owed to Nathaniel Julius, Collins Khosa, Leo Williams, Petrus Miggels, and thousands of others whose value cannot be reduced to a statistic, was not fulfilled.

The content we crave?

Netflix promo shot.

Netflix promo shot. It���s no surprise that streaming services are growing on the African continent. Although Africa is treated as the final frontier of global internet connectivity, its fortunes are fast changing, indicated by heightening efforts to improve digital infrastructure and make data and broadband more readily available. So, as more Africans become digital denizens, streaming services are taking notice ��� the decision by Netflix in December to appoint Strive Masiyiwa to its board (a�� Zimbabwean businessman who founded of Liquid Telecom, Africa���s largest independent fibre operator), announces their serious intention to gain a foothold on the continent.

This seems like a good thing. Now more than ever, Africans have access to not just content, but also big-budget content that is locally produced. Netflix, for example, is using original programming as a way to attract African audiences, a market which could grow to 13 million subscribers by 2025. Shows like Queen Sono, Blood & Water and recently, Namaste Wahala, have globally trended and made Africans feel like for once, they are the ones exerting cultural influence on the West rather than it being the other way round. But how true is this actually? As an AIAC contributor pointed out in a review of Queen Sono not so long ago, ���Since Hollywood cinematic conventions have been entrenched as hegemonic cinematic conventions, the possibility for international filmmakers to work outside of that mold is almost impossible.���

Consider another recent intervention, this time by the acclaimed American director Martin Scorsese in Harper���s Magazine, suggesting that some artistic integrity can be salvaged through streaming if it���s structured around curation rather than content: ���Curating isn���t undemocratic or ���elitist,��� a term that is now used so often that it���s become meaningless. It���s an act of generosity���you���re sharing what you love and what has inspired you. (The best streaming platforms, such as the Criterion Channel and MUBI and traditional outlets such as TCM, are based on curating���they���re actually curated.) Algorithms, by definition, are based on calculations that treat the viewer as a consumer and nothing��else.���

So joining us on AIAC Talk to discuss how digital technologies are changing African film and TV are Mahen Bonetti, Dylan Valley, Sara Hanaburgh and Tsogo Kupa. First, we���ll be joined by Mahen, a pioneer in bringing contemporary African films to Western audiences. In the early 1990s, Mahen started the New York African Film Festival, which changed the way Americans consumed films from and about Africa.�� Mahen has also firsthand experienced the transformation from primarily offline viewing to being available on streaming services like Netflix, Amazon, Showmax, Iroko TV or Criterion Collection.�� We want to ask, what does the film festival look like in the age of streaming? And what stories are African filmmakers trying to tell, what makes one worthy of being showcased, and who is watching them anyway?

Then, we���ll talk to Dylan, Sara and Tsogo, who all happen to be AIAC contributors, with Dylan also serving on our editorial board. Dylan is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and lecturer at the University of Cape Town, Sara is a scholar of African literatures and cinemas at St John���s University, and Tsogo is a writer and filmmaker based in Johannesburg. It was Tsogo who made the observation about Queen Sono cited above, and with the three of them we���d like to explore the general prospects and limitations of streaming on the continent. While the more popular offerings on streaming platforms could crudely be seen as simply ���candy floss entertainment,��� more ���content��� in the ocean of mass culture���as distribution mechanisms, do they make it possible to, as Sara asks in a recent piece, ���conceive of a future where African auteur films can enjoy shooting and editing on the continent, uninhibited by national and international politics���can African cinema find distribution beyond the festival circuit?���

And actually, what do we make of the category ���African cinema��� to begin with? Monolithic description, or useful shorthand?

Watch the show the show Tuesday at 19:00 CAT, 17:00 GMT, and 12:00 EST on��YouTube,��Facebook, and��Twitter.

Last week���s AIAC Talk was about decolonizing the COVID-19 response. We spoke to Sakiko Fukuda-Parr about how places beyond the West (like say, Bhutan or Vietnam), were able to respond to the virus in a way that didn���t choose between lives or livelihoods, and what lessons we can draw from these experiences.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

February 28, 2021

The Nigerian dream is to leave Nigeria

Lagos airport. Image credit neajjean via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Lagos airport. Image credit neajjean via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. To leave one���s country for another is a usual part of life in today���s world. However, some Nigerians often make news headline for trying to do exactly that. For instance, a 14 year old boy was recently reported to have landed in Spain atop a cargo ship from Lagos. There was also the news about a group of Nigerians who, having been repatriated from Libya, are planning to leave again.

We have become desensitized to the news of illegal Nigerian migrants arriving in Italy on boats and of young Nigerians (or Africans) journeying through the Sahara desert in search of greener pastures in Europe. Interestingly, it is not only poor and uneducated Nigerians who are bent on leaving their country. According to a report on Al Jazeera, wealthy Nigerians are also buying citizenship in places such as Malta and the Caribbean. But the group of Nigerians leaving the country at an alarmingly high rate are young professionals seeking better career opportunities.

For example, as of 2018, the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria reported that there were 72,000 nationally registered Nigerian doctors but only 35,000 practicing in the country. This is also the trend in academia, IT, and financial services among other professions. Data published by the Canadian government in 2019 reveals that the number of Nigerians issued permanent residency there tripled since 2015. In fact, in 2019 alone, more than 12,000 Nigerians emigrated to Canada. Other popular migratory destinations for Nigerians include the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, Germany, and South Africa. Beyond the question of brain drain (which the Nigerian government seems nonchalant about), this mass exodus of Nigerians of all classes invites more reflection on the Nigerian spirit and dream. Is there even a molecule of nationalism left among the Nigerian populace? Are Nigerians still invested in, or protective of, the sanctity of the idea of the nation-state?

While other nations dream of economic equality and happiness for their citizens, the Nigerian dream seems to be anchored in the desire to emigrate. The PEW Research Center published a 2019 study that shows that 45% of Nigerian adults plan to leave the country in the next five years.

The most widely read contemporary Nigerian literary works are those that deal with the experiences of Nigerian migrants. For example, Chimamanda Adichie���s Americanah, a novel that got its title from the honorific given to Nigerians who live or have lived abroad (especially the US). Nollywood, Nigeria���s elephantine movie industry, also makes a lot of profit selling these emigratory aspirations to Nigerians. Recently, the famous and controversial Nigerian musician, Naira Marley, released a song titled Japa (a Yoruba word for ���abscond���), which touches on the issue of emigration. The title of song has now been appropriated as a slang among young Nigerians nursing migratory dreams. There is even a book titled Japa, which purportedly provides guidance for Nigerians who want to emigrate within six months. There is another Nigerian song that went viral precisely because the singer, Bembe Aladisa, begs white people for a visa in the lyrics of the song.

In Nigeria, to be an emigrant is to possess illustrious social capital and a badge of honor that is not only reserved for you, but also for your family. In Nigeria, churches and mosques organize fasting and prayers for people applying for visas. Visa application is a very lucrative business in a place like Lagos and people often get defrauded because of their desperation to get obtain one. Nigerians have created a hierarchy of respectability that hinges on people���s migratory status. Some Nigerians even consider migratory prospects when choosing a marital partner. Nigerian schools and other institutions now take pride in preparing young Nigerians to compete abroad. Even the Nigerian government tends to recognize the achievements of Nigerians abroad more than Nigerians at home. The reason for this, Ima Jackson-Obot notes, is partly because ���the economic future of Nigeria and the success of Nigerians abroad are closely tied.��� The Nigerian economy relies, significantly, on remittances from Nigerians in the diaspora. According to the Outlook for Remittance Flows 2012-14, Nigeria is the seventh biggest recipient of money remitted to the home country by her citizens living abroad.

Aspirations to emigrate have become a Nigerian ideal. The desire to leave Nigeria is now entrenched in the Nigerian psyche. Many of us live to leave, and the essence of our ���Nigerianness��� finds expression in our ability to emigrate. Most young Nigerians desperately pursue the promise of a better life outside of the country, even through illegal means. It does not matter if the migratory destination is a neighboring country. What matters is that you are ���in the abroad��� as Nigerians like to say.

On the one hand, people leave because of their disillusionment with the Nigerian state. The collapse of public service, the rise of ethnocentric politics, and corruption have all contributed to a disintegration of the national ethos. The majority of Nigerians no longer rely on the government for basic amenities such as water, electricity, security, and medical care. Also, due to the high rate of unemployment, poverty, collapsed infrastructure and police brutality, the Nigerian government struggles to prove its legitimacy and credibility to its citizenry. Many Nigerians feel excluded from the country���s cartography of belonging and are unable to imagine a habitable future for themselves there. Hence, despite the travel restrictions brought about by COVID-19, thousands of Nigerians are still leaving the country.

On the other hand, contrary to the belief that emigration is only a recent development in Nigeria, statistics show that Nigerians have been emigrating even before independence. The only difference, in my opinion, is that there are more desperate and irregular movements now than in the past. What this suggests is that emigration has always been part of the Nigerian essence. It is what feeds the spirit of ���Naija-politanism��� as well as the performance of mobile nationalism by Nigerians. Also, emigration has always been behind the Nigerian belief in the un-colonial conquering of the world and the confidence in overlooking barriers (even if that barrier is an impervious migration policy). Therefore, despite the abysmal conditions that inform their emigration, contemporary Nigerian emigres may actually be contributing indirectly to our shifting understandings of the workings of nation-statehood in this era of accelerating globalization. Whatever the case, it is quite clear that Nigerians leave because emigration (and being successful in the diaspora) is a huge part of the Nigerian dream.

February 26, 2021

The death of cities

Empty Nairobi street via the World Bank Photo Collection on Flickr. Credit Sambrian Mbaabu CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Empty Nairobi street via the World Bank Photo Collection on Flickr. Credit Sambrian Mbaabu CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. All over the world, a debate about the future of cities has come up in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. In the United States, cities like New York and San Francisco, that in recent years have hit astronomical peaks in terms of housing prices, have started to see a mass exodus, as local business struggle, and the amenities and conveniences of high density living, that for some justified the high price tag of living there, are uncertain to ever return. In response, aided by the migration of much of the white collar world to remote working, tech oriented and wealthy professionals have set up shop in tropical islands, outer suburbs, or just cities whose housing costs haven’t yet hit their peak. The questions for these places is, what will the future of cities look like if and when these former residents decide to return? What will happen if they don’t?

This week, from our series of reposts from Kenyan publication The Elephant, managing editor Boima Tucker selects a piece that analyzes the situation from the perspective from Nairobi, a former colonial capital in the global South.

��� Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, 2011Cities are the absence of physical space between people and companies. They are proximity, density, closeness. They enable us to work and play together, and their success depends on the demand for physical connection.

In February this year, just before the coronavirus pandemic forced the Kenyan government to impose a partial lockdown in the country, I moved to Kenya���s capital, Nairobi, a city with a population of 4.4 million, from Malindi, a small town along Kenya���s coast with a population of just 120,000. I had been intending to move back home for several years but 2020 seemed an opportune time to do it. I had spent ten long years in Malindi and was ready to get back to the thick of things where the action was.

Now, I know for most people who live in Nairobi, the city is not ���home������the ���true north��� of most Nairobians, as Alexander Ikawah pointed out in a recent article, is their rural home, the place they identify most with. Ikawah says that Nairobi is just a place where ���city villagers��� work; where they have ���houses,��� not ���homes.���

But I am not among these people. I was born in Nairobi, and so was my father and my grandfather. Kenyan Asians don���t typically have a rural home (Asians in Kenya were not encouraged to settle in rural or agricultural land both before and after independence and so are concentrated mainly in urban areas). And even if they have an ancestral home in India or Pakistan, they don���t tend to refer to it as ���home,��� nor does this ancestral home loom large in their imagination. In fact, many Kenyan Asians have never visited their ���motherland.���

I have lived in London in the UK and Boston in the USA, and have traveled to many, many, cities around the world���New York (my favorite city), Istanbul (a cultural delight where East meets West), Mogadishu (a wounded city with nice beaches), Kabul (wounded but with majestic snowy peak backdrops), Havana (a salsa-lover���s dream, arguably the world���s most egalitarian city), Paris (a romantic city with many bridges), Mumbai (a buzzing ���maximum city��� of people, people, and more people), Beijing (interesting but with high levels of air pollution), Cairo (history lives here), Florence (a beautiful outdoor museum), Johannesburg (a legacy of apartheid, not my favorite city), Dar es Salaam (a friendly coastal city with huge potential), to name a few���but for me, Nairobi is not only home, it is also the place where most of my memories reside.

I will not go into the details about my reasons for leaving Nairobi in the first place, but it had a lot to do with trying to regain some perspective on life after having led a busy treadmill-like work existence, where career success depended so much on pleasing a boss and undermining colleagues to move up the career ladder. I was hoping that a break would allow me to do things I hadn���t had time for before, like writing and spending more time with my husband. I dreamed of looking out of the window and seeing palm trees swaying in the wind, and breathing in the salty Indian Ocean breeze. Oh what bliss (and it was) ��� until I discovered that meaningful social interaction was much more important to me than the sounds and smells of nature. Voluntary self-isolation, I discovered, is neither natural nor healthy. Human beings are wired to be social animals���that is how they survived as a species.

While living in a small sleepy town where nothing much happens gave me the freedom to pursue writing (I ended up writing three books during my self-imposed ���exile���) and other interests, I had a gnawing sense that I was in danger of disconnecting and self-isolating myself from all that was meaningful in my life. I yearned for intellectual stimulation and missed cultural and literary events. I longed to go to the cinema and hang out with my family. My social interactions in Malindi were superficial; I was in danger of becoming like the many expatriate (mostly Italian and British) retirees in the town, whose lives revolve around bridge parties and afternoon siestas induced by copious amounts of wine.

The truth is, I was lonely. I had not found my ���tribe��� in Malindi.

Then COVID-19 happened. It is unfortunate that my return to Nairobi coincided with a dusk-to-dawn curfew and partial lockdown, so my intentions of absorbing myself into city life have once again have been put on hold. I am back to self-isolating again.

The coronavirus pandemic has raised questions about whether cities will lose their allure, and whether people will look to leading simpler rural or small town lives. The fact that the virus emanated from the city of Wuhan in China and spread across the world through networks of cities and transport hubs is making people wonder whether we should be seeking more dispersed and less dense forms of settlement.

However, Tomasz Sudra, a former colleague who is now retired from the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat), told me that it was unfair to blame cities for COVID-19 because the virus could have been contained early if the Chinese government had not decided to suppress ���bad news.���

���The medical doctor who blew the whistle on the virus and died from it was forced to confess that he was spreading false news and was arrested,��� he said. ���The epidemic [in China] became a pandemic because the government suppressed the free flow of information.���

Cities have not only been associated with the rapid spread of diseases, but environmental degradation as well. The concentration of human and industrial activity in cities and the over-reliance on motorized forms of transport have been blamed for the air pollution that characterizes so many of the world���s large cities. Images of smog-free cities as a result of lockdowns (especially in China, where air pollution levels are so excessive that city residents routinely wear face masks) have been circulating on social media. People are asking whether the climate crisis could be blamed on cities, and whether COVID-19 will force us to seek alternative lifestyles.

John Gray, writing in the April 3, 2020 issue of the New Statesman, says that the current crisis is a ���turning point��� in history. ���The era of peak globalization is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. A way of life driven by unceasing mobility is shuddering to a stop. Our lives are going to be more physically constrained and more virtual than they were,��� he predicts.

Is the city���itself a product of globalization and the movement of goods and people from one shore or trading route to another���losing its attraction? Will there be a return to the nostalgic longing for rural life popularized by people like Mahatma Gandhi, who said that ���true India��� could only be found in the country���s villages? I don���t think so. The world, including India, is more urban than it was in Gandhi���s time. ���True India��� is no longer only in India���s villages, but in its teeming cities and towns, which currently host 34 percent of the country���s population.

Just over a decade ago, there were more rural folk on this planet than city folk, but that changed around 2007 when the world���s urban population equaled the world���s rural population for the first time. Though some regions of the world, notably Europe, North America, and Latin America, became predominantly urban much earlier (around the 1950s), the rapid urban growth rates in poorer parts of the world in the last fifty years have demonstrated that the pull of the city is stronger than ever. Cities must be offering something that villages don���t, or can���t.

I must confess that I have spent much of my professional life writing about what is wrong with cities and what can be done about it. At UN-Habitat, where I worked as an editor for more than a decade, the emphasis was on urban poverty and all its manifestations, including informal settlements (also known as slums). In 2006, UN-Habitat declared that one out of every three city dwellers lives in a slum, with sub-Saharan Africa having the largest proportion of its urban population living in slum conditions, with little or no access to water, sanitation, electricity, and adequate housing. Asia hosted the largest number of slum dwellers, though some sub-regions in the continent were doing better than others. Slums, warned UN-Habitat, were threatening to become a ���dominant and distinct type of settlement in cities of the developing world.���

This grim assessment was followed by another one in 2008, when UN-Habitat sounded the alarm on rising inequalities in cities, and warned that economic and social inequalities in urban areas had the potential to destabilize countries and make them economically unsustainable. Highly unequal cities���where the rich lead vastly different lives from the poor���are breeding grounds for social unrest, and social unrest disrupts economic activities, went the argument. UN-Habitat stated that pro-poor and inclusive urban development could significantly decrease these inequalities and make cities more sustainable. While the UN agency acknowledged that energy consumption in cities was impacting negatively on the environment, it made a case for mitigating the impact of carbon emissions through solutions such as environmentally-friendly public transport and the use of green energy.

Cities are not the problem; how we plan them is the central issue, said the experts.

Throughout history, cities have a played a central role in creating and sustaining civilizations. Cities are not just places where economic activities are concentrated, they are also crucibles of innovation and culture. The rise and fall of cities has often been associated with the rise and fall of civilizations. Cities such as Rome and Athens had their ���golden ages���; some survived a loss of status; others became relics.

In 2006, I was asked to write a short chapter on the benefits of urban living for UN-Habitat���s State of the World���s Cities report, which focused almost entirely on the gloomy topic of slums. The thinking was that there was a danger that in highlighting the problems in cities and slums, we might inadvertently throw the baby out with the bath water and that as the UN���s ���City Agency,��� it would be counterproductive to focus only on the negative aspects of urban life. In other words, by presenting cities as places where nasty things happen, we might actually be sending an anti-urban message to the general public and to policymakers.

Because cities were���and still are���viewed as the engines of economic development, and economic growth is generally credited for reducing poverty levels (though this has not been the case in some countries), I had to make an argument that made economic sense to governments and the public at large. So I argued that because so much economic activity in a country is concentrated in its cities, ���cities make countries rich.��� I further pointed out that the concentration of populations and enterprises in urban areas greatly reduces the unit cost of piped water, sewerage systems, drains, roads, and other infrastructure. Therefore, the economies of scale that cities offer are not replicable in small, less dense human settlements. Building a hospital or a road in a town or village with a population of just 50,000 is far less efficient per capita than building a hospital or road in a large urban area that hosts a population of 5 million (regardless of the ethics of making such a choice).

The central argument was that rural people don���t just up and move to a city; the main driver of rural-to-urban migration is economic opportunities and the chance to lead a better quality of life. In almost all countries, rural poverty levels are higher than urban poverty levels. (For instance, the poverty rate in rural Kenya is about 40 percent, compared to around 28 percent in peri-urban and urban areas.) Indeed, the data showed that despite the pathetic and hazardous living conditions in slums, people who lived in slums often viewed them as a ���first step��� out of rural poverty. As Edward Glaeser, a Professor of Economics at Harvard University, says in his book, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, ���Cities don���t make people poor; they attract poor people. The flow of less advantaged people into cities from Rio to Rotterdam demonstrates urban strength, not weakness.���

However, villages are not stagnant places either; some, like Mumbai, which was once a fishing village, grow to become megacities (defined as cities with populations of more than 10 million). Some cities, like Nairobi, were not even villages originally; Nairobi literally grew out of nothing except a railway depot built at the beginning of the 20th century. The world���s great cities did not only grow because they were centers of trade and commerce; they also grew because they were religious, political, administrative or cultural centers, and this is what drew���and continues to draw���people to them.

Many rural people move to cities because they believe that they and their families will have better access to health and education. Cities also offer women more opportunities for social and economic mobility. Unrestrained by discriminatory customs and traditions, urban women are more likely than their rural counterparts to have access to property and other assets. Child and maternal mortality rates are also lower in cities, including in slums, compared to rural areas.

The downside is that city life exposes people to hazards such as indoor and outdoor air pollution, congestion, and crime, which significantly impacts the health and lives of urban dwellers. Cities can be incubators of disease, crime and other vices; but these disadvantages have never stopped cities from growing, even when plagues and other health hazards infest cities and kill populations. The 1665 Great Plague of London, for example, killed thousands, but did not diminish London���s stature. COVID-19 has decimated populations in the city of New York���the city with the highest COVID-19-related death rate in the United States���but even images of mass graves of the disease���s victims are unlikely to deter people from moving there.

Safety nets are also weaker in cities, which is one reason why so many people in the developing world (where there are few government-funded welfare systems) identify with their rural homes, where, as Ikawah points out, social capital obtained through filial ties is much stronger (though associational life in slums, through cooperatives and self-help groups, have helped reduce some of this deficit).

Cities have also been derided for promoting mindless consumerism. They have been accused of driving a type of capitalism that encourages people to go on endless shopping expeditions to buy things they might never use or need. Large shopping malls���a distinct feature of modern cities���are filled with products that keep the wheels of capitalism moving. Alain Kamal Martial Henry predicts that the coronavirus will overthrow this ���Western bourgeois model��� imposed by capitalism. And this may lead to the eventual demise of cities and urban living.

I asked Daniel Biau, a former colleague who served as the Deputy Executive Director of UN-Habitat from 1998 to 2005, whether we could from henceforth witness a decline in urban growth levels, and whether people will now seek to move out of large cities to places that are less dense and concentrated.

Biau was not convinced that the coronavirus pandemic will change the way people view cities. ���As usual, a few journalists will write about risky cities but their alarming views will be completely ignored by ordinary people who know very well that cities are, above all, places of job opportunities, social interactions, education and cultural development,��� he said.

He predicts that in the digital age, it is likely that small and medium-sized cities will grow faster than big metropolises because teleworking will become the norm. ���Already in France 40 percent of the working population is currently teleworking,��� he said.

���History has shown that some cities could shrink due to economic or environmental reasons. But cities have never disappeared due to health reasons. This is why the UN should provide guidelines for the promotion of safer and healthier cities as part of the wider sustainable cities development paradigm,��� added Biau in an email exchange.

Cities will exist���and continue to grow���because of human beings��� need for social interaction, physical contact, and collaboration. As Glaeser points out in his book:

The strength that comes from human collaboration is the central truth behind civilization���s success and the primary reason why cities exist. We should eschew the simplistic view that better long-distance communication will reduce our desire and need to be near one another. Above all, we must free ourselves from the tendency to see cities as their buildings, and remember that the real city is made of flesh, not concrete.

However, despite their density and diversity, cities can also be lonely places. The ���little town blues��� that I talked about earlier are also experienced in large cities. People living in high-rise apartment blocks in big cities or in suburbs on the periphery of cities often report not knowing their neighbors and lacking a sense of ���community.���

Some believe that rapid suburbanization since the 1950s, especially in the United States, led to increasing disillusionment among married women, whose isolated lives in well-planned (but boring) suburbs led them to question patriarchal norms and the virtues of being stay-at-home wives and mothers. This angst (described by Betty Friedan as ���the problem that has no name��� in her book, The Feminine Mystique) sowed the seeds of the American women���s movement in the 1960s and ���70s, and led many women to seek careers outside the home.

Some cities are better at fostering human interaction than others through carefully planned urban designs, and more people-friendly infrastructure, such as parks and other public spaces, including pedestrian-only streets. Recently, after a wave of rape cases in India, urban planners have also been thinking about how cities can be made more woman-friendly, with more street lighting and more gender-sensitive public transport. The designers of these cities understand one basic fact: cities are not about buildings and infrastructure; they are about people and communities.

The COVID-19 lockdowns have demonstrated how abnormal and disturbing self-isolation and social distancing can be. The pandemic has underscored the fact that human beings have an inherent need to interact with other human beings, even if it is at a cursory level. This physical connection with a diverse range of people from different backgrounds is what makes cities attractive, and is the reason why the city���in all its beauty and ugliness���is one of humanity���s greatest achievements.

February 25, 2021

The cultural resilience of a creole city

The New Year Carnival in Cape Town. Image credit George Bayliss via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

The New Year Carnival in Cape Town. Image credit George Bayliss via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. So far on this season of Africa Is a Country Radio, we have aimed to contextualize the musical cultures of various port cities on coasts of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In the face of forced migration, forced labor, and territorial imperialism we have seen how cultural hybridity has informed ideas of resistance and resilience in these places, as well as notions of citizenship, belonging and humanity for the peoples inhabiting them. Now we will visit another city that epitomizes these ideas, but one that happens to sit at the nexus between the cultural spheres of both oceans, Cape Town, South Africa.

In 1652, the Dutch East Indies company set up the Cape Colony as a refueling station on the way to its Jakarta colony in Indonesia. A few years later it would become the first settler colony of a vast capitalist trade network that stretched from New York to Brazil to India and Indonesia. With need for labor in its colony, the company would import slaves from the Indian Ocean, and by the time the British took over, a distinct Indian Ocean and Atlantic Ocean influenced creole society had emerged.

Like all settler colonies, a distinct racial hierarchy was put in place. But it wasn’t until South Africa���s official policy of legal apartheid that this social stratification would become so clearly etched onto the face of the city. While the carving up of the city would leave an indelible mark on the culture of the city, the resilience of the people would shine through via culture, particularly music, and would help inform the political resistance during the antiapartheid struggle.

In the post apartheid years, Cape Town has once again become a globally connected city with a multitude of cultural influences. Yet many stains of the white supremacist past remain, along with that legacy of resistance. In this month���s episode of Africa Is a Country Radio we will talk to two Capetonians, who also happen to be key members of the Africa Is a Country team. The website���s founder, New School professor Sean Jacobs and editorial board member and filmmaker Dylan Valley will join us to talk about their musical experiences growing up and living in Cape Town.

To frame the social history of Cape Town, we will also hear clips from an interview with researcher and author, Valmont Layne, that were originally conducted by the To the Best of Our Knowledge podcast, with whom we have recently started partnering with to develop content and cross-pollinate ideas. Layne is interviewed by Anne Strainchamps and Steve Paulson, who graciously let us use unpublished parts of their interview for our episode. You can hear their episode on the global impact of jazz music on their website.

Tune in today, Friday, February 26th from 2pm to 4pm GMT (9am to 11am EST) on Worldwide FM to listen live. After that, visit the show page our subscribe to our Mixcloud for the archived version.

The poet of colouredness and exile

Trade union meeting at a fishery industry in Cape Town in 1985. Credit UN Photo CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Trade union meeting at a fishery industry in Cape Town in 1985. Credit UN Photo CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Some 50 years ago, on a cold December evening in 1970 in Oxford, a brilliant graduate student from South Africa���a prize-winning poet who had already completed undergraduate degrees at both UWC and Oxford and was about to embark upon his doctorate���died from a drug overdose at the age of 27. His name was Arthur Nortje, and his life and work deserve to be remembered and celebrated far more widely than they have been.

The coroner���s inquest into his death returned an ���open��� verdict, and to this day the exact circumstances are unresolved. In fact, conjecture remains as to whether it was an accident or a suicide. What is known is that, returning home to college accommodation after a party, he overdosed on barbiturates and choked to death. The bald, squalid facts of his demise do no justice to Nortje, who strove with a lyrical voice throughout his short life to express truth, freedom, and belonging.

Arthur Nortje was born on�� December 16, 1942 in Oudtshoorn in the Western Cape, and moved with his mother Cecilia to Port Elizabeth, where he was raised in a working-class Colored township. His mother was a Colored domestic worker and his father a white Jewish man called Arthur, thought to be the son of his mother���s employer.

Given his penurious childhood, during which he lived in an iron shack, Nortje���s trajectory was a remarkable one. A gifted and industrious student, in 1961 he received a scholarship to study English at the University of the Western Cape. On completing his degree, he taught briefly in Athlone, a Colored township in Cape Town.

Coloredness was a bedrock of Nortje���s identity, not to mention a source of profound mental anguish, at a time when the concept of race was paramount in South Africa. Writing poetry was his passion; he was published in Black Orpheus magazine in 1961 and won the Mbari Poetry Prize (as did his teacher, mentor, and poet Dennis Brutus) in 1962. In October 1965, he arrived at Oxford to read for a second degree in English, where he remained until 1967. On graduation, he emigrated to Canada, teaching English in Hope, British Columbia, and in Toronto. When his teaching contract was terminated due to ill health, he returned to Oxford in 1970 to start a DPhil.

Life in the UK gave Nortje the freedom, which had been systematically denied to him in South Africa, to be a human being, one who was incidentally Colored. Yet he remained all too aware of the plight of his friends and family back home suffering under an ignoble regime. Nortje���s is an elegiac and harrowing life, in which he was a victim of apartheid���s draconian, de-humanizing laws and their knock on, deleterious effects on the Colored psyche. Both profoundly took their toll on his mental health���as did his copious smoking, drinking, and liberal use of LSD.

His poetry, published posthumously in the collections Dead Roots (London, 1973) and Lonely Against The Light (Grahamstown, 1973), is suffused with meditations on the Colored plight (often deemed ���too black to be white and too white to be black���) and the pain of physical exile from his homeland, probing what it means to be Colored in poems like Dogsbody Half-Breed and My Mother Was A Woman, and the exilic predicament of the self-proclaimed ���dispersed Hotnot��� cast up on foreign shores in Finally Friday, Cosmos in London and Autopsy.

Loss and alienation also permeate his poetic oeuvre (for example, in Waiting and Immigrant), but they are articulated with a lightness of touch that never descends to self-pity. Moreover, his poems are imbued with a powerful combination of existential angst and ontological disorientation, due to the deracination which his Coloredness, and subsequent exile from South Africa engendered. Both a perennial outsider and a nomad, Nortje���s Homeric peregrinations indicate a restless spirit and a reluctant acceptance of his quasi-Dantean exile.

The hybridity, liminality, and ambivalence inherent in Colored identity are all evident in Nortje���s poetry. So too is Fanonian self-hate, as well as a fractured, wounded sense of self and the pathos of never quite belonging. However, there is a more than a touch of Catullus��� amorous passion in his love poems, Baudelaire���s opiate-induced revolt, ennui and debauchery in his London flanerie, and overtones of Rimbaud with regards to his ambiguous sexuality.

While in the UK, Nortje developed friendships with South African poet and playwright Cosmo Pieterse (about whom he wrote Cosmos in London) and novelist Richard Rive. It is also probable that he was in contact with novelist Alex La Guma (who lived in London from December 1966), as well as frequenting a milieu of other South African intellectuals, writers, and activists. However, Nortje���s own role in the politics of exile is unclear. Probably at Brutus’s urging, he read at anti-apartheid rallies in London, and despite evident solidarity with such activism, he seems to have resisted overt membership of political groups. Thus, his limited involvement with South African freedom movements operating in the UK at the time indicates that Nortje was more Larkin than Milton, more Keats than Shelley, intent on courting the poetic muse more than the political one.

Sadly, Nortje did not live to see the end of apartheid. Today he lies buried in Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford, joining a list of illustrious South African writers who died in exile, such as Nat Nakasa (Harlem,1965) and Alex La Guma (Havana, 1985).

Like many consummately talented poets who died prematurely, one wonders tantalizingly what Nortje could have achieved, had he lived longer. But equally, we should rejoice at the poetic legacy he did bequeath us. Half a century has now passed since his death, but his poems and his recalcitrant spirit of Colored introspection and defiance most certainly live on.

In a post-apartheid South Africa in which Colored���s, despite being in the majority in the Western Cape, are still routinely marginalized and disenfranchised���this time not by the Afrikaner regime, but by the ANC government, Nortje���s work is both timely and apposite. His poetry speaks eloquently of the liminal, painful space that the Colored community still occupies in today���s ���Rainbow Nation.���

Moreover, in 2021, post George Floyd and the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movements in the US and Britain, racial injustice and identity dominate our consciousness. As a result, Nortje���s poetry has a striking contemporary relevance.

Ultimately, he was never able to fully reconcile the emotional tensions inherent in his Coloredness or to find peace with an identity fraught with racial ambiguity in a Manichaean world. Nor did he manage to expunge the sense of despair and rootlessness that exile engendered���sentiments he beautifully articulates in All Hungers Pass Away. Yet Nortje left an indelible mark on South African poetry, and Dennis Brutus��� description of him as ���perhaps the best South African poet of our time��� remains the most fitting epitaph for this humane, tortured genius.

February 24, 2021

What is learning for?

Kayamandi High School close to Stellenbosch, Western Cape. Credit Megan Trace via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Kayamandi High School close to Stellenbosch, Western Cape. Credit Megan Trace via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. Every year in early January, South Africans ritualistically take part in unveiling matric results���the exam scores of final year high-schoolers���from both private and public schools. For the most part, it’s a couple of weeks overflowing with feel good stories about the hard work of students. For many private schools, their learners and teachers gleefully grace television screens and newspaper front pages to bask in public praise. In 2020, just over 12, 000 students wrote the Independent Examination Board (IEB) examinations, achieving a 98.82% pass rate.

It���s a mixed narrative for public schools, who fielded 578,468 learners last year to write the government issued National Senior Certificate (NSC) exam, and of which 76.2% passed. While the spotlight tends to hover on feel-good stories about students shackled in adversity who muster their meritocratic will to accomplish impressive results, we are also sorely reminded of the stark differences in performance between private and public schools, and amongst the latter, free and fee paying ones. The recycled talking point is often around sluggish and unsatisfactory improvements, blamed on the government���s mismanagement of the education sector. Opposition parties never fail to hammer in the charge that the dismal state of our public education system forms part of the ruling African National Congress��� long-standing failure to competently deliver public services.

Unlike every other year, this year���s fanfare happened in February owing to how COVID-19 disrupted the academic year, and resulting in a more sombre tone. The class of 2020 spent almost six months of the academic year at home due to lockdown, with public schools having slowed re-openings due to repeated concerns around the appropriate safety measures being in place. By contrast, well-resourced private schools adjusted to the new world of physically-distanced and online learning with few scratches. It���s easy to say that the pandemic has laid bare the extent of inequality in South Africa, but it���s harder to ask what we should do about that. The instinct to point out the profound injustice of some learners moving along the academic year with little disruption while others are at the whim of material circumstances not of their choosing, is the correct one. But the South African public hardly reaches the natural conclusion that we should���which is that private schools should probably not exist to begin with.

The case against private schools has less to do with hoping to fix the dysfunctions of our education system as we currently know it, and more to do with asking the basic question of what an education system is fundamentally for. The prevailing belief is that education is a mere instrument for economic advancement. Acquiring an education is the process of attaining the skills and knowledge valued on a competitive job market, or at the very least amassing the credentials which ���signal��� to employers that you possess traits desirable in employees.

This is how most South Africans think about education, from primary school all the way to university. Following this view, it is rational for parents to strive to provide the best educational opportunities for their children and usually at great cost. But it is also the view which ultimately sustains an attitude of general indifference to the state of public schools on the whole. While there is sporadic outcry, most of that has to do with egregious cases (such as textbooks failing to be delivered en masse to schools), or is usually expressive of other political grievances (a general discontent about the ANC���s incompetence). That most people can���t genuinely be bothered is an outcome built into the logic of our schooling system, one whose premise is preparing individuals to fiercely compete in a society where there is a limited number of decent, well-paying jobs. So, when South Africans view our unemployment crisis as arising because too many people lack a decent education, what is forgotten is that we actually at the same time believe that the successful education of the masses is a dead-end, since there aren���t enough good jobs to go around anyway, and some will get them while others unfortunately won���t.

When poor and working-class children in under-resourced schools predictably fare much worse at school, unable to produce the good grades for which a good job is the reward, the resulting class inequality is legitimized by asserting that each child has the same ability to work hard for better results, as each worker has the same ability to work hard for better pay. Yet, we are all the products of a birth lottery, thrust into this world without choice. At the will and direction of our parents, our lives are dictated by a narrow and predetermined set of values imposed on us by them. As a child, young and malleable, everything that it means to be you is the outcome of chance.

Now of course, abolishing private schools won���t magically eradicate class inequality, nor would it eliminate class distinction. A good example of where that nevertheless persists is in South Africa���s publicly-funded universities. Schools located in urban areas will probably be better off than those in far-flung rural areas, and historically-private and former Model-C schools better off than all the rest. Rather, the case against the existence of private schools is the case for the democratization of the schooling system at large. It is to say that an education should not be thought of as a commodity but as a public good, and that an integrated and socially provisioned education system is a necessary precondition for a thriving democracy beyond a functional one.

Writing last year in the Financial Times, the British journalist Martin Wolf made the basic observation that ���In a democracy, people are not just consumers, workers, business owners, savers or investors. We are citizens. This is the tie that binds people together in a shared endeavor ��� Acting together, within a democracy, means acting and thinking as citizens. If we do not do so, democracy will fail.��� The idea that there are two South Africa���s���one for the rich and one for the poor���is an apt metaphor for understanding a country where not only does your class position indicate the quality of service provision one can access, but also what social world one inhabits. If there ever was such a thing as a South African dream, it would be to opt out of state provision and withdraw from the public sphere���to sign up for private medical aid and to live in fortified gated communities. The ideal South African is not the citizen but the consumer, and this idea is impressed upon children immediately when we send some of them to private schools.

Understandably, some might invoke parental choice arguments. Parents should be able to decide which schools their children go to, and can send them to a private one if they so wish. But if we accept that, we should also accept that parents should be able to refuse the schooling of their children altogether. The fact that education is compulsory in the first place reveals an idea woven into the very notion of society itself��� namely, that our nature as socially dependent beings makes it impossible to have real freedom other than through the collective institutions of our making. Only then, do individuals become truly self-determining.

Describing the evolution of formal schooling from classical antiquity through to its expansion in post-war social democracy (in the West), the political theorist Wendy Brown explains that education meant ���more than class mobility and equality of opportunity���Rather, the ideal of democracy was being realized in a new way insofar as the demos was being prepared through education for a life of freedom, understood as both individual sovereignty (choosing and pursuing one���s ends) and participation in collective self -rule.��� Not ignoring the useful practical skills and knowledge for a life of employment that education imparts, it is foundationally a medium for self-development, attaining membership of a political community, and for participating in civic life.

If education is about developing our capacities as citizens���by making us conscious of the forces shaping our lives and most importantly providing an arena where individuals experience equal standing and become more discerning about the common good���then a segregated schooling system, whether it is explicitly divided across race as during apartheid, or implicitly divided across class is it is now, is inimical to creating common citizenship. If one is a serious believer in cultivating a substantive democratic culture, then that commitment must be rooted in the idea that there must be some realm in which individuals encounter each other and become socialized as fellow citizens. The belief that education is about more than facilitating the production of economic wealth, unites a variety political thinkers throughout history���from Aristotle and Adam Smith, to Karl Marx and Paulo Freire.

Considering last year���s debacle at Brackenfell High School in Cape Town demonstrates the point I���m trying to make. There, a parent-organized matric farewell function was exclusively attended by white students, igniting widespread outrage and allegations that this was racist. Beneath all the drama of the clashes between white parents (supported by South Africa���s second largest party, the Democratic Alliance), and members of South Africa���s third largest party, the Economic Freedom Fighters, is the crude question of why any of this mattered in the first place. (As happens routinely in South Africa, the incident at Brackenfell, where students had already reported experiences of racism, sparked many more revelations of racism at South Africa���s schools, both public and private).

If we buy into an increasingly-popular conception of education as just a terminal passage to prepare students for employment (and where liberal arts subjects like music or history are taught only to strengthen their value as ���human capital���), then we shouldn���t worry so much about student bodies being well-integrated, beyond giving parents their ���money���s worth��� so to speak. But the Brackenfell incident sparked deep concerns precisely because we already think of education as being about more than high-pass rates and admissions into university. We think it outrageous that despite being in a diverse school many years after the formal end of apartheid, a lot of white kids still don���t have black friends! We implicitly think it the purpose of schooling to cultivate relationships that transcend ascriptive identities like race, gender and religion, beyond simply teaching kids mathematics and science. That school is also about learning to belong to a society.

But of course, the long-term trend in education writ large, even up to university, is one of less state investment and more commodification. In South Africa, as is the case in many other places, education is becoming less of a national priority���the government here recently announced that it will discontinue public funding for postgraduate teaching degrees, and as part of a general austerity agenda is planning to cut teaching posts and reduce overall expenditure on education. Yet what ultimately makes this turn possible is an education system that allows privatization from the start, failing to shield itself against market forces. The grand irony of all of this, is that even under the logic of capitalism, the point of education is to escape the coercion of the market���for how else is the long, time-consuming road of getting an education ordinarily justified, other than to say that one should ���work hard now, so that someday, you���ll never have to work another day in your life.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a world-historical event, one prompting many to call for a new social contract for what the future holds. In doing so, some fundamental features of the social order are being called into question. The fast-growing calls for a universal basic income guarantee for example, are not only made necessary by a world of soaring unemployment, but also challenge the idea that one���s survival and happiness be tethered to one���s employment. We should also then challenge the idea that education is merely a tool for entering the job market.

An empowered, thoughtful and active public is what our schooling system should build; one which in spite of inevitable political differences is committed to the highest aspirations of our life in common. It is a good time to start asking, what is learning for?

The African refugee equilibrium

Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya. Image credit Bj��rn Heidenstr��m via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya. Image credit Bj��rn Heidenstr��m via Flickr CC BY 2.0. For far too long, the global refugee situation has been misconstrued as static, with certain parts of the globe generating disproportionate numbers of refugees and others perpetually faced with the burden of hosting displaced peoples. In particular, Africa is seen as a producer rather than a receiver of refugees. To be clear, Africa is not a continent that feeds the world with refugees any less than it hosts them. Although Africa is seen as exceptional in terms of global refugee networks, the factors accounting for refugee crises can bedevil any region at any point in time. These factors include war, natural disasters, political upheavals, military coups, civil strife, religious or cultural persecutions, personal circumstances, economic hardship, terrorist activities, and many more.

African countries, as much as any other, have taken turns in both generating and hosting refugees, and if history is any measuring rod, will continue to do so. It is the African refugee equilibrium, a phenomenon whereby a country that at one moment in its history is feeding its neighbors with refugees can become, at another moment, the receiver of refugees from those same neighbors. Africa isn���t just feeding the world with migrants and refugees but is top on the list of hosts. As per the UNHCR statistics of 2018, 30% of the world���s 25.9 million registered refugees were being hosted in Africa. Yet, the numbers of Africans who make their way to the West as refugees and migrants occupy the headlines of international news, painting the continent and the people as a miserable ���sea of humanity,��� perpetually flooding the rest of the world, especially North America and Europe.

Examples of how Africa has been mutually hosting its own refugees and taking turns are unlimited. The regions of Central and West Africa have particularly exemplified the concept of the African refugee equilibrium, with many nations taking turns in generating and hosting refugees. Even in the days when it suffered refugee and migrant crises, few Equatorial Guineans left the continent; the vast majority fled to nearby Cameroon, Gabon, and Nigeria. During the First World War, the German colony of Kamerun fed the Spanish colony of Guinea with tens of thousands of refugees. But in the 1970s, Cameroon, in turn, hosted about 30,000 refugees from Equatorial Guinea. During the Nigerian Civil War, Nigeria fed several of its West and Central African neighbors with tens of thousands of refugees, including children, who ended up in countries such as Gabon and Ivory Coast. The post-civil war era has seen Nigeria host hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants from its neighbors, even while Nigeria itself simultaneously feeds some of those neighbors with a new category of refugees.

West and Central Africa are not unique in this exchange. Since the 1960s, nations in East and Southern Africa have taken turns between hosting and generating refugees. In East Africa, the Kakuma refugee camp in the northwest of Kenya currently hosts about 200,000 refugees from more than 20�� neighboring countries, including refugees from Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi, to name but a few. Uganda, which has sent refugees to its neighbors, including Kenya, hosts its own refugees and refugees from others. Uganda���s Bidibidi refugee camp currently ranks the second largest in the world.

Perhaps more interestingly is the fact that besides mutually hosting its own refugees, Africa has hosted refugees from other continents, including from Europe. While examples abound, a few here will suffice. During the late 19th century and the 20th century in the midst of anti-Semitism, a significant number of European Jews entered North and Eastern Africa as refugees, with some settling in as far as South Africa. On the eve of the First World War, there were already more than 40,000 Jewish migrants and refugees settled in South Africa. In the 1930s, South Africa again received more than 6,000 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. During the Second World War, in excess of 20,000 Polish refugees, who had been evicted from Russia and Eastern Europe following German invasion, were received and hosted in East and Southern Africa, including in modern day Tanzania, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. In the 1960s, the crisis of war and decolonization in the Congo caused the flight of several thousand whites from the Congo. They were hosted as refugees in a number of African countries, including South Africa, Congo-Brazzaville, Angola, the Central African Republic, Tanganyika, Rwanda, and Burundi.

The examples provided here only scratch the surface of the African refugee equilibrium, but they each demonstrate that we must pay attention to historical antecedents in refugee studies. In other words, we need to historicize African refugee studies. Only by so doing can we fully appreciate the important and diverse role that Africa plays. This approach clearly shows that if our neighbors are currently facing a refugee crisis and turn to us for assistance, we must view them with respect and compassion; it could soon be our turn and we could need them.

There are constant examples across Africa where our lack of knowledge of our own shared refugee experiences or sometimes outright denial of history continues to inform the way we treat fellow Africans with disdain and hostility. Xenophobia (better known as Afrophobia) in South Africa is just one example. The African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) has carefully documented xenophobic attacks against other African refugees and migrants in South Africa since 1994, establishing several cases where in many South African towns and cities, South Africans attacked, injured or even killed African refugees and migrants. If only an average South African knew that not too long ago many African countries were safe havens to many of their countrymen and women during the anti-Apartheid struggle, they would think twice before unleashing xenophobic attacks against other Africans. Even across West and Central Africa, there have been several instances of both civilian African populations and their governments treating other African refugees in their countries with unbelievable hostility. When oil was suddenly discovered in Equatorial Guinea in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Equatoguineans and the government alike, quickly forgot their shared refugee and migrant history with Cameroon, and began a series of hostilities against Cameroonian refugees and migrants who came to Equatorial Guinea for ���greener pastures.��� An informed knowledge about our collective refugee and migrant experiences would go miles in ensuring that Africans and African governments treat other African refugees and migrants in their countries in a friendlier and more accommodative fashion.

There is, however, hope on the horizon. Africanists are increasingly turning their attention to refugee studies and the African refugee equilibrium. Two special issues are forthcoming in the Canadian Journal of African Studies and in Africa Today, both of which showcase Africa���s shared and diverse refugee and migrant experiences. These issues are part of the efforts to redress the image of Africa and the misconceptions surrounding the continent regarding migrants and refugee movements.

What all of these means is that it is only a matter of time before the static image of African refugee dynamics and the African refugee equilibrium will displace these ahistorical ideas.

February 23, 2021

Is the future of African auteur cinema streaming?

Cam��ra d���Afrique (1983), directed by Tunisian pioneer filmmaker and scholar, F��rid Boughedir, is at once an expository presentation of the history of African cinema in terms of who the pioneers were, of how they approached decolonizing the image of the African subject, what their major accomplishments were, and what continuous challenges persisted. The release of the restored documentary in high definition and with a crisper sonic plane, most recently featured through streaming at the New York African Film Festival, at once allows us to revisit those major challenges and compels us to ask: Where are we 60 years hence? What has happened over the past 40 years?

At present, Bough��dir���s documentary remains the most comprehensive yet condensed archive of African cinema in existence. Comprehensive to an extent, since it documents Twenty Years of African Cinema (its English title), from Semb��ne Ousmane���s Borom Sarret (1963) and Black Girl (1966) to Souleymane Ciss�����s Finye (The Wind, 1982) with footage from feature film clips selected among the additional 40 first- and second-generation filmmakers of those years. Condensed, because that span of history of filmmaking is contained in just a frame short of one hour and forty minutes of 15mm reel. The restoration of the documentary seems doubly important considering not only the preservation of the film in and of itself, but also its conservation as digital archive.

Stylistically, the film is more of an audiovisual essay rather than a straight up expository documentary in that it aligns itself with the somewhat recent field of scholarly inquiry at once within and beyond academia, engaging critical inquiry through the use of sound and image. One might say that Bough��dir was ahead of his time in this regard, considering he was at once working as a practitioner of cinema���traversing the Sahara to meet his ���brothers in struggle��� in Carthage and FESPACO to discuss, debate, and show their films while making this documentary���as well as its North African counterpart, Cam��ra arabe, released in 1987���saving his money to buy one reel at a time, and writing his PhD thesis on the same topic. He was determined, literally at any cost and through any means, to record the birth and early development of African cinema, and to make it available to the broadest audience possible and certainly to those he knew would never go digging through the Sorbonne���s archives for his dissertation. Further, his own auteur style���the insertion of one���s own subjective positionality into one���s film and incorporating it into one���s own style���is inscribed in the film���s composition voiceover, direct interviews, archival footage of entire clips of original features and montage techniques which he employs in the service of his thesis that the pioneers of African cinema were Filming Against All Odds.

Few films have continued the work Bough��dir began through documentary filmmaking, although some have certainly focused on certain aspects. Mahamat Saleh Haroun���s docudrama, Bye Bye Africa (1999), for one, directly addresses questions���this time within the national context���including the filmmaker���s responsibilities, the filmmaking process, and an utter lack of cinema industry and infrastructure in Chad. Other films have focused on individual filmmakers, for instance, Laurence Gavron���s Ninki Nanka (1999). In her portrait documentary, Gavron attempts to elucidate some of the mystery around the figure of the great innovative filmmaker Djibril Diop Mamb��ty, as her camera tracks him on set filming Hy��nes (Hyenas, 1992). Unlike Gavron���s biopic approach, Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman pay tribute to the late ���father of African cinema,��� Ousmane Semb��ne, in Semb��ne! (2015). What their documentary shares with Bough��dir���s is an emphasis on the importance of archiving, made explicit in a memorable scene where narrator Gadjigo literally rescues hundreds of reels, which he���s found in the filmmaker���s disheveled and abandoned seaside studio, their metal cases rusty from direct exposure to the salty air.

Whereas this is by no means a call for a sequel to Cam��ra (or for more documentaries on related topics), it is crucial to note that questions around viable production and distribution of African filmmaking persist and are most resounding today. Auteur cinema across the continent remains plagued by a lack of industry���with few exceptions. Certainly, in spite of significant strides taken by the Pan-African Federation of African Filmmakers (FEPACI), including the (albeit short-lived) formation of south-south distribution networks such as the Inter-African Consortium of Cinematographic Distribution (CIDC) in the early 1980s, the most recent generations of African auteur filmmakers still face a nearly total lack of distribution outside a circuit that is dominated by the various lords of economic global imperialism. In other words, with all that digital archiving and streaming can offer���as Cam��ra���s restored re-release highlights���how can we conceive of a future where African auteur films can enjoy shooting and editing on the continent, uninhibited by national and international politics? How can African cinema find distribution beyond the festival circuit? Is the future of African auteur cinema streaming?

Organized interests

Image credit Paul Kagame via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Paul Kagame via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Activists from the Jobless Brotherhood have repeatedly smuggled piglets into the Ugandan parliament. The animals are daubed in yellow and occasionally blue paint, the colors of the ruling and main opposition parties, and wear signs reading, ���M-Pigs.��� ���These MPs are eating us alive,��� one activist commented, adding, ���These are national M-Pigs who are sitting in that house.���

Claiming to represent the millions of unemployed youth in Uganda, the activists denounce disinterested and corrupt MPs. More generally, confidence in parliament as a representative institution is consistently low in Uganda and neighboring countries. The most recent Ugandan elections, marred by ���unprecedented��� violence and rigging, did nothing to restore that low confidence.

How then, if at all, might MPs become more responsive to popular interests? How might they act less like M-Pigs? Much recent academic research and donor spending in Africa and elsewhere has focused on electoral incentives, on how more competitive elections could improve MPs��� accountability to the majority of poorer voters. The assumption is that if elections become more genuinely competitive elected representatives will push for more popular and broadly redistributive policies, improving health services and the like. However, research findings have repeatedly cast doubt on this assumption. While heightened electoral pressures may lead politicians to invest more in localized ���constituency service,��� there is little evidence that this pressure either directly motivates MPs��� legislative work or drives them to pursue more redistributive policy changes.

So, we are left to ask, do MPs at least occasionally support more popular���and generally more redistributive���policy interventions? And if yes, why? I address these questions in a recent article published in the journal Democratization (pre-prints available here). While not dismissing the significance of electoral pressures, I refocus attention on the largely overlooked role of organized interests in shaping legislative action.

Diverging from the more liberal institutionalist analysis, I draw inspiration from political economy and sociological literature, interested in how the distribution of power across organized interests affects who shapes legislative policy interventions and for whom. According to this literature, a concentration of elite power generally favors more regressive policy. However, there are exceptions to the rule, notably when more ���mass-based��� membership organizations���for instance, occupational groups like unions, professional associations, and cooperatives���mobilize and pressure MPs.