Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 134

March 23, 2021

Reading List: Kwasi Konadu

Photo by Efe Kurnaz on Unsplash

Photo by Efe Kurnaz on Unsplash In my most recent book, Our Own Way in This Part of the World: Biography of an African Community, Culture, and Nation, I used the optics provided by one Kofi D���nk��� and his community-cum-nation to challenge standard accounts of Ghana���s modern history and to reimagine the histories, politics, and cultures of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Africa. I had set out to narrate the story of this healer, blacksmith, farmer, drummer, and family head during shifting periods of the ���colonial��� and ���postcolonial��� world, but through the lens and interlaced evolution of kin, community, and culture. Kofi D���nk��� was versatile, operating fluidly as custodian and interpreter of shared values, facilitator of spiritual renewal, promoter of social cohesion, settler of disputes, and assessor and planner of the community���s growth. But he was also a marginal peasant farmer whose fortune and misfortune rode the tides of the cocoa boom, an everyday person who offered us a multiangled window into the social lives and networks of rural dwellers, and an intellectual who articulated a profound understanding of disease and therapeutics to those in West Africa and the African diaspora as well as to a group of notable scholars.

Location and an integral cultural heritage stand out among several factors that shaped the life of Kofi D��nk�� and his polity���a region that fell under the Asante empire and then the British empire, forming a dual colonialism. Situated in the crossroad polity of Takyiman, between the northern and southern halves of the nation, he and his polity���s positionality invite scholars to think of interior Africa���rather than solely its coastal littoral���as a gateway for cultural contact and the making of intra-African histories, and as a counterpoint to evangelical perspectives. Indeed, it is precisely Kofi D���nk������s deep devotion to his craft, his culture, his community that framed his life and that makes him a significant figure in African and world history. Through this figure, Ghana appears less a nation-state defined by homogeneity and a citizenry of ���one nation��� than it is a geography populated by kin, strangers, and antagonists, all of whom are connected to communities and locations and to internal and external diasporic formations. Rather than solely consider how Kofi D��nk�����s life story maps onto major themes in twentieth-century Ghana/Africa/world, I was careful to specify what Kofi D��nk�� and his community���s lived experiences and ideas revealed about colonial rule, missionary religions, diseases, political independence, decolonization, global war, and human culture.

Through an approach I call communography, in that my concern is not with the individual life story but rather with the thousands of kin, community members, and strangers who knew, interacted with, and lived during historic moments Kofi D��nk�� shared. I choose to tell this story through the evocative and varied moments in which humans live, rather than through

the predictable and artificial plots historians devise. Of primary importance was interweaving D���nk���’s life and community with the tripartite history of the Gold Coast/Ghana and broader patterns in world history. Shaped by historical forces from the colonial cocoa boom to decolonization and political and religious parochialism, the story of D���nk���’s community provides a non-national, decolonized example of social organization structured around spiritual forces and humanistic values that serves as a powerful alternative to nationalist statemen and as an important reminder that scholars take their cues from the lived experiences and ideas of the people they study.

As a study that began at a ground zero, in terms of published materials, I spent a decade making my way through missionary, imperial, multinational, hospital, regional, and national archives in Ghana, looking for bits and pieces of Kofi D���nk��� and his world. My guide, at least conceptually, was Ayi Kwei Armah���s The Healers. Armah���s historical fiction explored the fall of the Asante empire, under whose immediate hegemony Kofi D���nk��� and Takyiman, and the emergence of British rule over the tripartite colony. Evocatively, in the mouth of Armah���s main character who chooses to become a healer, the author asked:

What really is a healer’s work? You may say it’s seeing. And hearing. Knowing… Men walk through the forest. They see leaves, trees, insects, sometimes a small animal, perhaps a snake. They see many things. But they see little. They hear many forest sounds. But they hear little … A healer sees differently. He hears differently… Yes, he hears and sees more.��� Armah���s expectation that ���healer must first have a healer’s nature,��� and that ���the healing work that cures a whole people is the highest work, far higher than the cure of single individuals,��� aminated the book.

Though there were no models for the study I envisioned, I drew much inspiration from T. C. McCaskie���s Asante Identities: History and Modernity in an African Village, 1850-1950.

McCaskie���s microhistory of the Asante village of Ade��beba, between 1850 to 1950, narrative in rich details the ordinary lives of African men and women in a period of social change, led as they were by a remarkable woman named Amma Kyirimaa. More than Kofi D���nk������s counterpart, Kyirimaa was also a healer and custodian for Ade��beba���s Taa Kwabena Bena, an ���bosom (spiritual force) that paralleled his Asub���nten Kwabena in Takyiman. As I have tried to do with Kofi D���nk���, McCaskie details the larger implications of Ade��beba for the understanding of Asante culture and identities against the backdrop of colonial rule and modernity. More important, McCaskie and I both place African voices at the center of their histories.

Knowing that Kofi D���nk��� lived in a part of Africa, in a part of the world, I found it fruitful to draw on comparative studies, if only to sharpen my own, and found Karen E. Flint���s Healing Traditions: African Medicine, Cultural Exchange, and Competition in South Africa, 1820-1948, and Abena Dove Osseo-Asare���s Bitter Roots: The Search for Healing Plants in Africa well-crafted sounding boards. Like me, Flint focused on the nineteenth and twentieth century but in southern Africa, historicizing the interaction between indigenous and biomedicine and how so-called ���traditional��� healers in Natal, South Africa, transformed themselves from politically powerful men and women who challenged colonial rule and law into successful entrepreneurs who competed for turf and patients with white biomedical workers. Kofi D���nk��� was a master herbalist (���dunsinni) and so Osseo-Asare���s examination of the transformation of healing plants in Ghana, Madagascar, and South Africa into pharmaceuticals as well as how African scientists and healers, rural communities, and drug companies develop drugs from medicinal plants since the late nineteenth century provided necessary global context for Kofi D���nk������s healing work. And it was precisely through healing, through training other healers, through nurturing scholars with his intellectual that this local figure became regional, national, and then global.

March 22, 2021

Why the tree is producing bad apples

Cyril Ramaphosa visits Cuba in 2015. Image via Government of South Africa on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Cyril Ramaphosa visits Cuba in 2015. Image via Government of South Africa on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. Every week in South Africa, corruption dominates the headlines���with new arrests or scandals ranging from dysfunctional local government right up to the presidency.

A case in point is Makhanda, my hometown in the Eastern Cape. Makhanda is located in Makana municipality, where service delivery has collapsed due to corruption prompting the Unemployed Peoples��� Movement (UPM) to launch a successful court challenge against the municipality for its failure to meet constitutional obligations to provide sustainable services. Both the municipality and the Premier of the Eastern Cape, Oscar Mabuyane, have appealed and the case is now being heard in the Supreme Court of Appeal. Entrenched in the appeal are the culture of entitlement and self-enrichment.

Myriad reports on the extent of corruption in South Africa���from state capture to municipal malfeasance���have flooded print and broadcast media for the past decade. There has been a tendency to reduce the crisis of governance in South Africa to bad leadership and questionable ethics, and to suggest that getting rid of the people in charge will solve the problem. For example, the ascendency of Ace Magashule to the position of Secretary of the African National Congress (ANC) encompasses what has become of the predatory political elite. In his recent book, Gangster State: Unravelling Ace Magashule���s Web of Capture, Pieter-Louis Myburgh shows how Magashule, in his previous capacity as Premier of Free State, drained the coffers of the provincial government to buy his political career while impoverishing and diminishing the people he was supposed to represent. Meanwhile, the ���new dawn��� of economic growth and moral regeneration under the leadership of current State President Cyril Ramaphosa has come to little. The expanded unemployment rate is over 40% and the black working class is drowning in a sea of hopelessness and despair (more so during the COVID-19 pandemic), while corrupt practices by political elites and their beneficiaries continue to be exposed.

Corruption in South Africa is systemic and must be placed in its historical context. Corruption is certainly not limited to the activities of post-apartheid political elites. Although perhaps different in form, it was inherited from the apartheid-era, particularly in regional administrations that were spawned from bureaucracies of the former network of Bantustan (���homelands���) administrations across the country. In 1984 the prominent opposition politician Frederik van Zyl Slabbert called the homelands policy nothing but ���a multiplication of bureaucratic disaster areas, consuming vast amounts of capital���to serve the wants and needs of small, privileged bureaucratic elites in seas of poverty and underdevelopment.���

Prior to the political settlement of 1994 at the core of public service was the corrupt public service. Louis Picard, in his book State of the State, writes, ���By 1994 the South African government had become ensnared in its own bureaucracy, and an entitlement mentality had developed in the country. This culture of entitlement would be particularly strong at the provincial level where most homeland administrators ended up working.���

Yet, as author Hennie van Vuuren notes in his book, Apartheid, Guns and Money:

In South Africa, the issue of grand corruption under apartheid has been the source of comparatively little public debate. Since the advent of democratic rule scant attention has been paid to the possibility that leading apartheid-era functionaries (in government and business) may have used the cover of authoritarian rule to illegally acquire vast sums of wealth in defiance even of the legal ���norms��� of that time.

Thus, the culture of entitlement among the political elite and in the bloated civil services was embedded in the system and continued through the transition from apartheid. Due to decades of socioeconomic oppression, the majority of aspirant black bourgeoisie had no access to capital. The ANC prioritized the development of a black capitalist class to deracialize industrial capital. Black economic empowerment (BEE) initiatives flourished as did the entrenchment of a politically connected kleptocracy���from infamous arms deals to procurement and tendering irregularities at all levels of government. The new political dispensation, through the transition, prioritized the assimilation of the black political elite, rather than changing society and reorganizing the structural foundations of South Africa that would seek to minimize the weaponization of the state. And as Van Vuuren writes:

Individuals who entered the public and private sector after 1994 and were motivated by greed to act corruptly were likely to welcome the opportunity to work through, and with, influential people, often well networked, who had escaped criminal prosecution under apartheid for similar activity.

In South Africa, political connectedness and loyalty to the ruling party appear as pathways to the accumulation of wealth for Black people. Rising up the ranks of the party is not achieved through good work, commitment, or capacity, but through concealing or being part of corrupt activities and showing loyalty to the party above all else. This is evident particularly at municipal level, where the appointment of officials is not based on competency and merit, and factionalism is endemic promoting abuses of power, while undermining access to and delivery of resources and services.

Frantz Fanon���s is prophetic in The Wretched of the Earth about the potential of a national bourgeoisie to appropriate liberatory movements for their own gains, and of the possibility of liberation leaders succumbing to the corrupt and exploitative practices of colonial regimes:

There exists inside the new regime, however, an inequality in the acquisition of wealth and in monopolization. Some have a double source of income and demonstrate that they are specialized in opportunism. Privileges multiply and corruption triumphs, while morality declines���The party, a true instrument of power in the hands of the bourgeoisie, reinforces the machine and ensures that the people are hemmed in and immobilized. The party helps the government to hold the people down.

And as Van Vuuren echoes:

Access to power (and a monopoly over it) provides the elite in the public and private sectors with a unique opportunity to line their pockets. In so doing, the defenders of an illegitimate and corrupt system start to defy their own rules and laws that criminalize such behavior.

To radically change our society was not on the agenda during the negotiations for a transition to democracy in the lead up to 1994. The arms deal of the Mandela era was the baptism of our political elite, many who became millionaires and profited through their connections to the white business class.

To claim that corruption is the fault of individual leaders means that we will continue to pick the bad apples off the tree, but not diagnose why the tree is producing bad apples. Corruption is South Africa���s pandemic���one that has been disenfranchising and killing people long before our transition to democracy. To claim that corruption is systemic in South Africa is to assert that until we challenge the established order, it is business as usual.

March 20, 2021

Lay him down on a high mountain

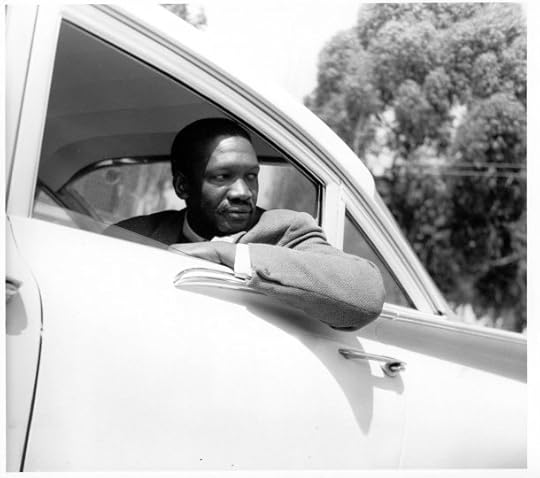

Robert Sobukwe. Image via Twitter.

Robert Sobukwe. Image via Twitter. Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe took his final breath on February 27, 1978 in Kimberley, South Africa. Sobukwe was a man on a divine mission, one whose uncompromising dedication to the liberation of the African people shook the racist state of apartheid South Africa to the core in March 1960. Sobukwe organized one simple action: He mobilized the oppressed and dispossessed African masses to leave their dompasses (the colloquial name for the internal passports black Africans had to carry to access white-only areas and to justify their presence in urban areas) at home and present themselves for arrest at their nearest police station. Police responded by shooting to death 49 protesters and wounding hundreds.

The international condemnation against white South Africa was swift; Sharpeville represented a turning point in the struggle against apartheid. Sobukwe had catapulted his movement, the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), to the forefront of the resistance. (One year earlier, he had formed the PAC after breaking away from the African National Congress.) For Sharpeville, Sobukwe was sentenced to three years in prison. At the end of his sentence, he was interned on Robben Island for a further six years, under the unprecedented Sobukwe clause which was passed to keep him in prison indefinitely. On his release, he was banished to Kimberley, where a decade later, stricken with cancer, he died.

But if Sobukwe had lived, what would his future have been? And what might South Africa look like, had we followed his political principles and ideals?

After leaving the University of Fort Hare where he cut his teeth politically, Sobukwe became a teacher in Standerton, in what is now Mpumalanga province, and later taught African languages at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. In April 1959 he was elected president of the PAC at its founding.

At his trial post-Sharpesville, Sobukwe told the judge that he ���felt no moral obligation to obey the laws that have been made by a minority in this country ��� An unjust law cannot be justly applied.��� Sobukwe simplified a problem that eluded many in the political climate of racist and racialized South Africa: African freedom fighters worried themselves about accusations from whites that they were also ���racist���, because whites only ���meant well.��� ���If whites believe that Africans hate them, it behooves them to remove the source of or the reason for the hatred,��� Sobukwe said.

What is not well known of Sobukwe was that in his prison letter and correspondences, Sobukwe displayed the opposite of what many of his political foes had accused him of being���anti-white. From his close friendship with journalist Benjamin (���Benji���) Pogrund, who would later write Sobukwe���s biography, and prominent white liberals like Leo and Nellie Marquard whom he would frequently write to and engage on a wide range of topics from politics, literature, and theology and about their personal lives. Officially, the PAC was fiercely critical of white liberals, so one would expect Sobukwe to not engage with them, but he did the opposite: He was gracious and kind in line with his political principles that Africans do not hate white people solely because they are white, but that they identify them with their oppression.

In outlining the position of the Africanists in their disagreement with the leadership of the ANC,�� Sobukwe described the Freedom Charter (the document adopted as a manifesto by the ANC and its allies in 1955) as “a colossal fraud ever perpetrated upon the oppressed, exploited and degraded people. It clearly bears the stamp of its origin. It is a product of the slave colonial mentality and colonialist orientation.” Sobukwe believed that instead of replicating an already existing democratic structure of decision-making copied from the West, change in South Africa required the re-constitution of the already established norms and a complete overhaul of the oppressive capitalist system. This included the restoration of the land to its rightful owners���the Africans. The only economically just thing to do in a post-apartheid South Africa would first be the “establishment of an economic equilibrium by downsizing the top and uplifting the below so that all meet at the equilibrium from which all will grow.”

Politics in post-1994 South Africa have become a politics of dishonesty, as they were in the past when a social contract had been woven using rhetoric and a false understanding of non-racialism. This very rhetoric is given legitimacy through concepts such as the rainbow nation, apparently having ���the world���s best constitution���, all to sustain the myth of�� ���a South Africa alive with possibilities��� at the expense of the black majority, who continue to be disenfranchised until this day.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission made apartheid the primary and only basis of the struggle waged by the African people. Specifically, the TRC dealt with human rights abuses from period between 1960 and 1994. As for land, it treated the 1913 Land Act as year zero���as if the wars of land dispossession of the African people started then.

Sobukwe addressed this in his first speech as the president of the newly formed PAC. On August 2, 1959, Sobukwe foreshadowed the incompleteness of a negotiated settlement to apartheid, one that would ultimately come to be spearheaded by the ANC. In that speech, Sobukwe already observed that, ���This captured black leadership claims to be fighting for freedom when in truth it is fighting to perpetuate the tutelage of the African people���It has completely abandoned the objective of freedom. It has joined the ranks of the reactionary forces. It is no longer within the ranks of the liberation movement.���

Mangi, as his wife Veronica fondly called him, was a tall lanky fellow who was always full of life, endowed with�� a toughness of spirit, sharpness of mind and intellectually discipline and training. Though not a usual politician, he was the embodiment of virtuous political leader. He forms part of a tradition of Africanist leaders and thinkers who defied the undefinable racist regimes and as ZB Molete, the former secretary of publicity of the PAC, once remarked, that ���Sobukwe belonged in a class of popular but lonely leaders who are distinguishable by their devotion, dedication, and determination.���

Sobukwe was not afraid of isolation or suffering (on Robben Island, authorities deliberately isolated him from other prisoners) and he was not afraid to stand alone in principle. He belonged to a class of thinkers who considered the political argument of restoration and restitution as inseparable from the struggle against psychological domination. He was a university lecturer, and his wife was a qualified nurse. He could have lived a comfortable middle-class life with his family. But Sobukwe chose to “starve in freedom rather than to live in opulence in bondage.”

In a poem dedicated to him and in remembrance of this great man Don Mattera wrote that:

Let no dirges be sung

no shrines be raised

to burden his memory

sages such as he

need no tombstones

to speak their fame

Lay him down on a high mountain

that he may look

on the land he loved

the nation for which he died.

A revolution deferred

Sunset prayer in Tahrir Square, November 2011. Image credit Hossam el-Hamalawy via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Sunset prayer in Tahrir Square, November 2011. Image credit Hossam el-Hamalawy via Flickr CC BY 2.0. This year marks 10 years since the Arab Spring began as a protest movement in North Africa and the Middle East, transforming the region and ushering an era of social upheaval still with us today. Writing in the New York Review of Books, the Moroccan journalist Aida Alami distills the postcolonial dilemma that spurred the uprisings and which still afflicts African states today: ���Most of these countries had won independence from Western colonizers after World War II, only to find themselves ruled by corrupt tyrants. The hopes and wishes of ordinary men and women were never taken into consideration, and these societies were governed for decades by fear.”

These societies, including those south of the Sahara, are still governed by fear. While we unpack the legacy of the Arab Spring and the regimes it challenged, the leader of one, increasingly oppressive regime in Tanzania met his bitter end. On Wednesday, Tanzanian president John Magufuli died allegedly of heart disease. Having begun his presidency on a hopeful note as a corruption busting resource-nationalist, he ended it as an authoritarian, COVID-19 denialist. Magufuli���s rule in many ways simply replayed a leadership script written into post-liberation Africa: appropriate anti-colonial rhetoric to indigenize capitalism, make modest redistribution to the masses, and weaponize this to consolidate the regime���s power.

It was this script that the Arab Spring challenged.

Much of the anniversary-related commentary on the legacy of the Arab Spring fixates on how this challenge failed. We are told to look at Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria and especially Libya���things haven���t changed, or they are much worse than before. But, the mistake of this diagnosis is its assumption that the historical process started by the Arab Spring is complete. We are still in the interregnum from which it started, and for Iranian-American scholar Asef Bayat, the Arab Spring typified the political mobilizations characteristic of the interregnum, what he calls the ���non-movement���������Non-movements refers to the collective actions of non-collective actors; they embody the shared practices of large numbers of ordinary people whose fragmented but similar activities trigger much social change, even though these practices are rarely guided by an ideology or recognizable leaderships and organizations.���

For Bayat, the post-2008 outpouring of non-movements constitute ���revolution without revolutionaries������but the journal Endnotes turns this on its head, noting that instead, ���we are witnessing the production of revolutionaries without revolution, as millions descend onto the streets and are transformed by their collective outpouring of rage and disgust, but without (yet) any coherent notion of transcending capitalism.��� From the Arab Spring itself to moments like #FeesMustFall, the non-movement provides the organizational form for a disorganized age. As uprisings re-emerge on the continent���from #EndSARS in Nigeria, to the re-emergence of protests in Tunisia, protests in Senegal, and the return of student protests in South Africa���they all make the crucial connection between economic stagnation and escalating police brutality���the question is whether from that, sustained critiques of capitalism will emerge.

So, joining us on the next AIAC Talk to explore how much longer the revolution will remain deferred, are Amar Jamal, Nihal El Aaasar and Zacharia Mampilly. Amar Jamal is a Sudanese writer, translator and post-graduate student in anthropology,Nihal is an Egyptian independent researcher currently based in London and Zachary is the Marxe Endowed Chair of International Affairs at the Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, CUNY.

The sort of�� questions we want to ask them are summed up by the ones motivating the book Zachary co-authored in 2015, Africa Uprising: Popular Protest and Political Change: ���From Egypt to South Africa, Nigeria to Ethiopia, a new force for political change is emerging across Africa: popular protest. Widespread urban uprisings by youth, the unemployed, trade unions, activists, writers, artists, and religious groups are challenging injustice and inequality. What is driving this new wave of protest? Is it the key to substantive political change?��� For example, what remains of some of these popular protests, like the Sudan Revolution (which Amar has eloquently written about for Africa Is A Country). And notwithstanding the importance of international solidarity, as Nihal explains, might we also be in a moment that necessitates stronger continental solidarity too? Can we replicate the pan-Africanism of the 20th century, or has the nature of globalization made that impossible?

Stream the show the show on Tuesday at 18:00 in Cairo, 16:00 in London, and 12:00 in New York on��YouTube.

On last week���s show, ���Unearthing the past���, we first spoke to Enver Samuel, the director of Murder in Paris, a new film about the murder anti-apartheid activist Dulcie September, as well as Evelyn Groenink, who is the author of the book from which the film heavily draw, Incorruptible. Then, we spoke to Madeleine Fullard, who leads the Missing Person���s Task Team, an organization that emerged from the TRC and which is responsible for finding the remains of murdered anti-apartheid activists.

Clips from that episode are available on our��YouTube channel, but as usual, best check out the whole thing on our��Patreon��along with all the episodes from our archive.

March 18, 2021

Unchain my art

Lausanne, Festival de la Cit��, 2017. Image credit Gustave Deghilage via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Lausanne, Festival de la Cit��, 2017. Image credit Gustave Deghilage via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. There was really only one music news story in South Africa in February 2021: the protests by musicians Eugene Mthethwa, of the kwaito pioneers Trompies, and Ringo Madlingozi, now an Economic Freedom Front member of parliament, (backed by a statement from his political party) against the South African Music Rights Organization (SAMRO) concerning alleged delinquency in paying royalties.

SAMRO���s job is to administer performing rights on behalf of its members. They do so, ���… by licensing music users (such as television and radio broadcasters, live music venues, retailers, restaurants, promoters and shopping centres), through the collection of license fees which are then distributed as royalties��� to artists.

The claims by Mthethwa and Madlingozi�� coincide with a Facebook post by vocalist/composer Ziza Muftic���supported by multiple followers in the music profession���about the user-unfriendliness of the current SAMRO website, and the perceived breach of natural justice in placing an expiry date on live performance submissions, when the performances have happened and SAMRO has presumably collected on them.

I have not examined the documents related to the Mthethwa/SAMRO dispute. SAMRO���s Mark Rosin has denied wrongdoing and suggests there is a broader context of dispute including monies allegedly due from Mthethwa to SAMRO. I do follow the logic of Muftic���s Facebook post; it makes sense to me. I���m not a legal expert or an actuary, and it���s up to experts such as those to untangle the rights and wrongs of specific cases and practices.

This column is not about these individual cases. It���s about the broader issues: that severe relationship problems clearly persist between the country���s largest royalties collection agency and its constituency at the very time when musicians are most desperately in need of revenue; and that, once more, the government department tasked with overseeing the sector remains silent and apparently unknowing about it all.

I say ���persists��� because the elephant in the room when discussing anything to do with SAMRO is the organization���s negative history during apartheid. Established in 1961 under Dr Gideon Roos the organization became (whether deliberately or not is less relevant in 2021; it was unarguably unjust whatever the intention) a vehicle for all kinds of abuses perpetrated by the white-controlled music industry against black artists, from white producers assigning themselves or their designated stooges as the owners of Black creativity, to the classification of much popular music as ���traditional���, which erased the creativity and denied the financial rights of its modern makers.

We cannot blame the current SAMRO administration for that���but it lurks as a malevolent shadow over any interactions with artists today, even when nobody mentions it.

The first step towards setting relationships with artists on a better footing would be an honest, impartial, transparent reckoning with the past. Establish a mini-Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the recording and rights industry; hear testimonies; report findings and develop a reparations mechanism, whether financial or in the form of scholarships or other investments in the future of Black South African music. However large (and they probably won���t be), such reparations can never be adequate against the psychic pain caused, but they would represent an important acknowledgment.

Prompted by the Facebook entry, I looked���with advice from a registered musician friend���at parts of the current SAMRO website. It certainly is user-unfriendly: clunky, hard to navigate, and written in far-from-plain language. Another aspect of repairing relationships would be to correct that as quickly as possible. And we do, of course, have more than one official language, with great music made in all of them���why force everybody to operate in English?

In July 2020, ConcertsSA (an organization often associated with SAMRO) commissioned a survey of live streaming activities in South Africa: ���Digital Futures.��� Among the recommendations respondents made were some directed at collective management organizations in general, and some directed specifically at CAPASSO (Composers, Authors and Publishers Association) and SAMRO. Repeatedly, the need for simple, transparent and accessible systems and processes, and forums for meaningful constituency input were foregrounded by respondents, alongside making faster, more accurate payments.

Complaints about the justice and effectiveness of royalty disbursements are by no means a uniquely South African issue. A quick Google will turn up dozens of articles on the topic, covering all aspects of intellectual property (IP) administration, and most countries. (See, for example here, and here���a tiny sample from what���s out there.) In South Africa, as I���ve noted above, the issue is further poisoned by historical injustices.

The lack of comment from the government Department of Science, Arts, and Culture (DSAC) is concerning. This blog has noted before that the Department prioritizes ���creative industries��� aspects of the arts, and thus is often more distant from other kinds of debates. But these issues���the practices around IP and collecting and distributing royalties; the earnings of artists���are central to a creative industries perspective. A few days have passed since Mthetwa and Madlingozi���s protests���but far longer since this and related rights and royalties controversies began bubbling. DSAC���s silence remains deafening. Even the usual routine statement���in line with the Department���s responses to various sports body scandals���noting events and appealing to all involved to get their acts together, would have been a minor improvement on nothing.

Even if the Trompies star���s chains aren���t quite as weighty as those brandished by SAPOHR���s Golden Miles Bhudu over the past 20 years, his protest should remind us that all is not well with royalty administration in this country, and that nobody can afford (in the case of our musicians, literally) to let it fester unattended for much longer.

Don���t cede the streets

Image Credit Nicholas Rawhani.

Image Credit Nicholas Rawhani. Police violence in South Africa is frequent. Yet, there is something about how it happens in present circumstances that makes it feel different. One reason for this might be how the BlackLivesMatter uprisings of last year had an immediate effect on transforming people���s consciousness. Now people are alive not just to the incidences of police violence which regularly occur, but are equipped with a vocabulary to explain its injustice. In some cases, this understanding crystallizes into the concrete demand that the police are defunded, or abolished altogether.

Perhaps then, flowing directly from this is the second, curious thing about contemporary police violence: it feels more and more irrational. Importantly, the history of police brutality is the history of its senselessness. Even in tense, protest conditions that turn violent, the likelihood of violence is proven to increase by the mere presence of police who make the situation unnecessarily confrontational. What is curious about the latest, reported cases of police brutality is that they all involve decidedly non-confrontational situations, where the police themselves unashamedly provoked conflict.

The recent, ongoing resurgence of student protests in South Africa are an instance of this. Students across university campuses have been demanding that all eligible students (even those with historical debt owed to the university), are allowed to register. At one demonstration this month outside the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, Mthokosizi Edwin Ntumba was shot and killed by the police. The mainstream media did much to emphasize that he was a passer-by, but in a shared Freudian slip initially began by describing the deceased as a civilian���as if the peacefully protesting students were not civilians. This is revealing of the collective unconscious of the media class and the establishment it represents. Students, engaged in their inalienable right to protest, and engaged in legitimate political speech, are in the media���s imagination some kind of enemy combatant. (A similar thing just happened in the United Kingdom, where a vigil held in honor of Sarah Everard, a woman allegedly murdered by a police officer, was violently shut down by police officers).

Now, this isn���t to attribute what���s happening as the result of some deliberate, conscious plot from the ranks of the police; it is not as if they are receiving direct orders from higher-up to act more belligerently. (South Africa���s Minister of Police, Bheki Cele, has done the usual routine of casting the officers responsible for Ntumba���s death as rotten apples in an otherwise decent batch). Rather, the police are impersonally driven to behave in this way by the totality of capitalism itself, which is why reforms will never really work. The police exist to serve and protect capitalism, to safeguard the private property system upon which it is based. That���s the goal of ���public order policing��� which always attempts to disperse crowds���not because people are threats to each other in those scenarios, but because people are seen as threats to lifeless things around them called property.

So, when capitalism is in as deep and devastating a crisis as it is now, when its legitimacy is becoming more widely questioned and its inequality painfully felt, so too, will its enforcers acutely feel the threat of disorder that arises from this discontent. Everyone is restless, and the system is anxious. The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented situation where supposedly by consent, populations gave up their rights to movement and association in the interests of public health. For a period, social antagonism became invisible because the typical arena of its staging���the streets���were foreclosed. In this period of what was basically a state of emergency, politics was neutralized and a momentary national interest���curbing the spread of the virus���was prioritized. This isn���t to say there was no contestation in the last year, but rather that all of it happened within the bounds of the new national interest.

What is happening now is that politics is returning. With a year of practice, the pandemic is becoming less of a risk to engaging in political activity, and the accumulated grievances around its mismanagement make it for many, a risk worth taking. From the state���s perspective then, the temporary respite is over and the public is a troublesome nuisance again. The annoyance from government functionaries at once again being widely disliked, and challenged, has become palpable. For instance, deflecting criticism that the budget he tabled to parliament is an austerity agenda, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni declared that, ���There is no need to be apologetic about it. There is no social contract to say there must be an increase each year. The allocations we made are what we can afford.���

Mboweni���s budget was well-received by South Africa���s liberal press���another revealing fact. High-minded sermons about why cutting spending is important for ���stability��� are the mirror image of talk about why the police are required for ���order.��� Today���s authoritarianism won���t come in an overnight fell-swoop as some people���s nightmarish visions of Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia suggest. Rather, it���ll come through the return of the repressed. Remember that neoliberalism arose through dictatorship in Chile, and as Grace Blakeley instructs us, capitalism has always been authoritarian, but ���one reason the authoritarianism of the system has been so easy to ignore is that its abuses largely took place out of sight, inflicted on those least able to resist.���

South Africa has been in crisis for some time now, and the decay of its social contract has been obvious ever since former president Jacob Zuma���s corruption-ridden regime came to power a year after 2008���s Wall Street crash. From then, we witnessed the state���s murder of striking miners at Marikana in 2012, the violent suppression of students at the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall protests in 2015 and 2016. And now, students are back to make the same declaration���but what���s different is that some are relating campus struggles to anti-capitalist ones, declaring that #AusterityMustFall too.

It���s hard to predict what course these protests will take���but one of its chief slogans, ���Asinamali���, which in isiZulu means ���We have no money������demonstrates its potential to not only address the barriers to entry of the increasingly commodified university, but the barriers to living in an increasingly commodified world. Many have called the first #FeesMustFall wave the most serious challenge to the post-apartheid political order, but its vital limitation was an inability to connect to broader working-class struggles. That link has now been forged in a way that wasn���t there before.

Another thing to overcome is the pathological exceptionalism peculiar to South African political consciousness���of thinking our police are particularly cruel, our higher education system particularly inaccessible, our state particularly corrupt. Being able to see how our problems are more or less the same as everywhere else in the world empowers us to draw lessons from those who are fighting them earnestly���and whether it was in Chile in 2019, the US in June last year, Nigeria in October last year, India at the start of this year, or Myanmar right now���one lesson endures: don���t cede the streets. We don���t always have to take to them, but they are ours for the taking.

We are stronger than we think, and that is why they fear us.

March 17, 2021

The pathology of economics

Photo by Seyiram Kweku on Unsplash

Photo by Seyiram Kweku on Unsplash On February 24, 2021 Ghana received a vaccine shipment (600,000 doses), the first to sub-Saharan Africa under the COVAX facility. It amounted to a tiny fraction of the hundreds of millions needed on a continent increasingly ravaged by the pandemic. Contrast this to the tens of millions already vaccinated in the UK and US. The optimism that Africa would be spared by ���early lockdown���, ���less dense population, ���the effect of ultraviolet���, ���a climate that meant people spent more time outside��� and ���Africa���s youthful population��� has rapidly faded. Officially there are now more than 100,000 deaths on the continent, but the real numbers are much higher due to the paucity of testing and the lack of capacity to accurately track and evaluate causes of mortality.

The shortage of tests and vaccines are exacerbated by the West���s hyper-nationalism restricting the import of these two vital tools to combat the pandemic.��The same forces have also generated a scarcity of personal protective equipment (PPE), the lack of monoclonal antibody and other treatments, and terrible shortages of medical oxygen so vital to keeping people alive. How is it possible, 60 years after independence, for African countries to be so highly dependent on the goodwill of the outside world for basic health goods? A good deal of the answer lies in the pathology of economics and related policies, which have spread like a pandemic globally and have come to dominate both the West and the continent of Africa. How did this come about? How does it relate to the strategies that have undermined African capacities to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the health and welfare of its people? And what should be done?

Following independence, higher education was a key part of the national development project and was aimed at training Africans to take on vital new roles as doctors, teachers, lawyers, civil servants, and economists. Economic curriculum in universities theorized about the nature of Africa���s integration into the global economy and the domestic policies needed to enhance development. Debates on the government strategies drew on diverse theoretical traditions such as institutional and structural economics. There was a general consensus on the need for African countries to use government tools to build an industrial base.

Beginning in the early 1980s, donors shifted from supporting state planning and import-substitution industrialization toward imposing structural adjustment. They were resisted by local economists not inclined toward the neo-classical model that provided the theoretical basis of neoliberal policies. Donors even ghost wrote reports, pretended they were written locally and then praised them for their thoughtful insights. The World Bank and other donors realized that opposition could be demobilized, and ���ownership��� generated by incorporating the economics profession into the Western economic model.

The crisis of African universities, including the extreme decline of academic wages partly generated by the structural adjustment project of the World Bank in the 1980s, created the opportunity. Donors provided stipends to retrain old faculty, provided the demand for these local ���skills��� in aid packages and supported a new generation of students in neoclassical economics through organizations like the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), formed in 1988 with the support of the World Bank and other agencies. The AERC set out to revamp higher education by training graduate students and by providing financial support to economics departments in African countries to organize graduate coursework and research along Western lines. The AERC flow of tens of millions of dollars from donors to African universities was a huge inducement for African economics departments to participate in the programs. Today, economics departments throughout Africa look no different than their Western counterparts. By the AERCs own count there are thousands of their graduates in African ministries and central banks, think tanks, NGOs, and academic institutions. Empowering this ���epistemic community��� of local economists created trusted purveyors of the international agenda and helped facilitate the institutionalization of neoliberal policies on the continent.

At the heart of adjustment were neoliberal policies of deregulation, privatization, macro-stabilization, and user fees in health and education, which were supposed to lead to static efficiency gains. Unfortunately, the results were very different. Public expenditure cuts and the privatization of social services in health care and education put African countries in worse health and on the wrong trajectory to combat any pandemic.

Neoliberalism loosened restrictions on capital flows, privatized state enterprises, and liberalized trade undermining local manufacturing capacity leading to more reliance on imports of manufacturing goods including pharmaceuticals and other health commodities. Increasingly African countries became more dependent on exporting unprocessed raw materials for foreign exchange. Hence, adjustment led to the deindustrialization of the continent and returned Africa to its colonial style extraction economy with its problematic boom and bust commodity cycles. Manufacturing fell from 18% of GDP in 1980 to only 7%-9% after 2000.

The tools of mainstream economics are limited in their ability to conceptualize the structural and institutional exigencies of development, which have become even more challenging with African countries at the lower end of the of global supply chain. Recent studies have indicated that Africa���s exports after 2000 have increased without a comparable rise in domestic value added.��Yet, orthodox economists see liberalized Africa as naturally following its comparative advantage. Hence, we have prima facie evidence of a discipline that accepts a pathological condition as normal with all of the problematic incapacities to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

African policy makers need to draw on the wealth of accumulated knowledge in multiple theoretical paradigms to design strategies to diversify and structurally transform economies in a value chain world.��None of this is easily conceptualized in the neoclassical paradigm that currently dominates the discipline in Africa; one that narrowly focuses on a world of marginal changes, retracted states, and trade between countries based on static comparative advantage.

A more detailed elaboration of some of the arguments here can be found in H. Stein, ���Institutionalizing Neoclassical Economics in Africa: Instruments, Ideology and Implications��� Economy and Society Volume 50, No.1, Feb. 2021.

The imagined immorality of refuge

Kenyan security forces in Dadaab. Image credit Daniel Dickinson for EC/ECHO via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Kenyan security forces in Dadaab. Image credit Daniel Dickinson for EC/ECHO via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. In recent years, Kenya���s refugee camps have been routinely characterized by mainstream media as ���hotbeds��� in a regional geography of ���terror.��� Images of camps as crisis-ridden or lawless���predating the country���s fight against the Somali Al-Shabaab���have been infused with fears over the infiltration of ���safe��� humanitarian spaces. Refugees at the receiving end of ethno-racialized discrimination, such as Somalis, have born the brunt of growing suspicions from both the government and the wider public in Kenya and abroad, while South Sudanese refugees were no less problematically portrayed as especially ���difficult populations.���

Popular narratives about ���refugee terrorists���, ���criminals���, or ���troublesome��� aliens have loomed large in past years and legitimized acts of spectacular state violence. One example is Operation Usalama Watch in 2014���during which thousands of Somalis were incarcerated and systematically abused by Kenyan police forces��� and punitive police operations against Nuer and Dinka communities in Kakuma Camp the same year, followed by the Kenyan government���s decision to close down the Dadaab refugee camps in 2016. Meanwhile, aid organizations have often pleaded with government authorities to not add to the suffering of ���vulnerable��� groups in need of protection.

In my experience of studying humanitarian operations in Kenya, these opposing representations of refugees as potential ���terrorists��� and ���criminals��� or ���vulnerable victims��� are in fact built on a series of shared imaginaries that reproduce a racialized, colonial discourse on immorality, belonging, and civilization. The United Nations (UN) itself have recently come under fire over institutional racism and discrimination among its ranks. UN Secretary-General Ant��nio Guterres had to defuse a controversy over a memo discouraging staff from participating in anti-racism protests in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd last summer. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) concedes in its Guidance on Racism and Xenophobia that ���racism can undo all the work UNHCR and our partners do to protect those we serve.��� Writing about her experience of working for the organization, former UNHCR staffer Corinne Gray notes in The New Humanitarian, ���while we���d like to think we���re good people because of the very nature of our work, our humanitarianism does not preclude us from exhibiting racism. In many ways our humanitarianism reinforces it.”

Unsurprisingly, prejudice and discrimination rarely manifest in official speeches or reports, in which NGOs, aid agencies, and governments usually profess their commitments to human rights and self-imposed codes of conduct. Adia Benton contends that white supremacy and structural racism are instead more insidiously embedded in everyday humanitarian professional practices, with harmful consequences for aid workers of color and racialized ���beneficiaries.��� According to Ruth Wilson Gilmore, racism works systemically as the ���extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.��� Differential vulnerability of those living under humanitarian administration is further reinforced through the everyday actions, utterances, and imaginings of aid workers and officials. Refugees are habitually viewed through a quasi-colonial gaze that casually���and seemingly inconsequentially���conflates race, ethnicity, and mobility with forms of ���immorality.���

In Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya, one of the largest on the continent, NGO and government workers���both Kenyan and ���foreign��� alike���were often preoccupied with panics around the ���moral degeneracy��� of refugees who they regularly depicted as ���cunning���, ���sexually deviant���, or simply ���uncivilized.��� Buried underneath these ascriptions lay a colonial mapping of the world in which ���primitive��� or ���pre-civilizational��� societies are perennially at the mercy of Western-centric humanitarian salvation. The unspoken subtext of encampment was therefore a ���civilizing mission��� to turn supposedly disorderly and morally unmoored refugees into responsible, worthy, quasi-citizens.

Josiah was a middle-aged aid worker and former officer in the Kenyan army who I first met in March 2015 in the Kakuma camp. In the 1990s, he joined a faith-based aid organization in Kakuma. Yet over two decades on the job had left him disillusioned. ���If you are not intelligent, you can���t manage the Somalis,��� he warned gloomily before asserting almost apologetically���lest there be any doubt���that the South Sudanese were also ���criminals kabisa��� (total criminals). Josiah was no outlier or ���bad apple��� in this regard���far from it. Aid compounds���in which humanitarians, police officers, journalists, researchers, and donor delegations meet and mingle���were breeding grounds for such talk. While white Euro-American humanitarians were flag-bearers of these racist discourses, their Kenyan counterparts (who made up the majority of agency staff) seemed equally invested in tropes that drew much inspiration from the racialized subsoil of postcolonial Kenyan society. A Kenyan UN protection officer remarked nonchalantly during an interview in Kakuma, ���We are dealing with refugees here���one, people that do not understand the law; two, people that do not understand order, you see?���

Refugees as ���crooks��� and opportunistic criminals���who took advantage of both international aid and Kenyan hospitality���was a recurring and, for many, convincing trope. Marcus, a thirty-year-old policeman, decried the criminal minds of young South Sudanese in Kakuma. ���There is no good or bad youth [���]. They are all bad, thieves and thugs���. In his view, pleas for human rights, aid and humanitarian protection were a decoy���a performance directed at well-meaning donors from Europe and North America, whereas his police officers saw the ���unruliness��� and supposed violence that refugee youth were capable of. Stern-faced, he asserted, ���that���s how they really are.���

Relatedly, camp residents were attributed with sexual promiscuity that rehashed racist colonial discourses on hypersexualized Africans and their ���licentious��� urges. While the breakdown of familial ties through displacement offered one oft-cited explanation for the imagined surge of ���immoral��� behavior, notions of immutable cultural and racial ���otherness��� were equally often invoked. Sexuality worked, in Michel Foucault���s terms, as a potent discourse on pleasure and power that organized public morality in the camp. This could easily leave refugees in a double-bind: either as imagined victims or as perpetrators of ���backward��� cultures and violent African masculinities, or as disciples of a debauched ���Western��� morality that supposedly celebrates and promotes homosexuality and rewards those who follow suit with resettlement.

Morality is key for understanding the inner workings of aid regimes. Humanitarianism itself is a deeply ���moral project��� propelled by socio-historical beliefs in a Euro-American mandate for the deliverance of racialized Others through intervention and imposition of ���order.��� Fassin has further identified the rise of a new moral economy of humanitarianism that is not just a way of empathizing with suffering but, crucially, of governing ���sufferers.��� The colonial overtones and pretensions of everyday discourses on the moral decay or ���uncivilized��� customs of refugees in Kakuma were hard to ignore. Faced with trouble in implementing public health outreach inside the camp in 2016, Samantha���a white humanitarian who I sometimes met for dinner at the UN compound���privately denounced an entire refugee community as ���fucking bush people that don���t even know how to use a toilet.��� Years of humanitarian assistance, trainings, and workshops had in her mind done little to change the harmful cultural practices of those refugees, so she wondered ���how are they going to learn more complex stuff?���

���Refuge��� is not only a geographical location to facilitate protection and aid. Rather, it harbors distinct moral imaginaries that often pathologize refugees as a defective category of humanity. Beneath current anxieties about tackling forced displacement, terror, crime, and victimhood lies a recognizable lexicon of racialized difference that infuses humanitarianism in practice. While ���morality��� may offer an emotive framing to put into motion the wheels of aid in times of crisis, it remains a double-edged sword and a colonial technology that problematically naturalizes a hierarchy of who does and does not deserve assistance. As such, it precludes any possibility of genuine solidarity, equality, or material justice.

March 16, 2021

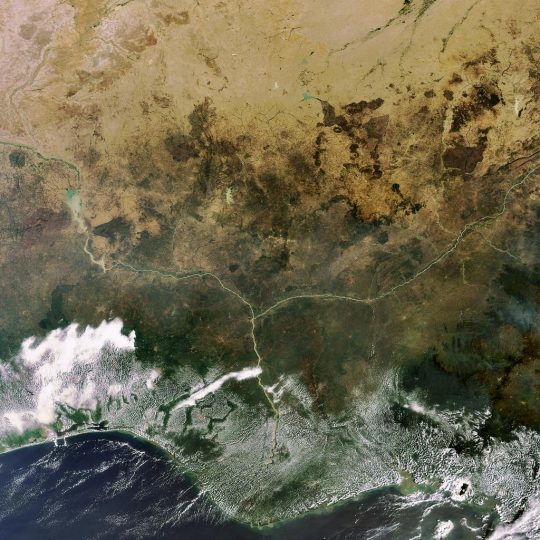

Economic crime in the Niger Delta

Image credit the European Space Agency CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit the European Space Agency CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. The decision of a Dutch court in January 2021 to order Shell���s Nigerian subsidiary to compensate local farmers over recurring oil leaks has been welcomed by many, invoking ���tears of joy��� in some cases. Although the outcome of this hearing is certainly better than its immediate alternative, celebration is premature. The strength of the case largely lies in its potential to kick-start a cumulative prosecution wave that may eventually mean oil conglomerates are meaningfully held to account.

Putting pressure on governments and international bodies to economically sanction harmful activity in the Niger Delta has proven to be insubstantial in the past. Under neoliberal capitalism, harmful activity is legitimized and reproduced through these practices���if community remuneration is to become commonplace in the oil sector, such expenses will merely become a cost-of-business in an organizational balance sheet. Implicit in the existence of such regulation is acceptance of the transactions that occur, reinforcing the ideology that environmental and social wellbeing has a price tag. A reconceptualization of crime to encompass the actions of an elite class, and a dismantling of neoliberal ideals is required to open up the possibility of significant change in the region.

The intricate ecosystem of the Niger Delta is home to countless species of flora and fauna, and is fundamental to the culture, identity and livelihoods of the local Ogoni people. Their way of life has been agonizing over the decades with many communities displaced from ancestral territories, left to survive on land and waters degraded beyond rejuvenation and surrounded by conflict and unrest. Repeated spills have been the source of years of tension between transnational corporations and local communities, a struggle marked by extreme power asymmetries and inexorable ideological incompatibilities.

Today, corporate and institutional actors hold distinguished yet interconnected roles, which ultimately complement one another to uphold an international economic order in which crime is embedded. In post-independence Nigeria, unequal power relations and a subordination of the poor majority���s needs to that of capital accumulation were enhanced through globalization and neoliberalism, aiding corrupt practices and shaping the neocolonial climate. Internationally, we see that capitalism in its most unsparing form has laid fertile ground for the proliferation of economic crime. However, it must also be understood that to see the dominant economic system per se as the problem is a simplification���we must delve further into the roles of the particular powerful actors that represent, enforce, and drive the reproduction of neoliberal capitalism.

In considering the above, the corporate actor is perhaps the most obviously befitting���many engaging extensively in lobbying, insulating themselves by having input into regulatory frameworks or working to remove regulation altogether (a painless task in today���s intensely pro-market climate). In Nigeria, oil syndicates consistently act outside the law, employing aggressive attempts to block protective legislation for communities. Exact figures of oil spills in the region vary, but it can be safely understood that recent decades have seen millions of barrels of oil illegally leaked into the natural systems of the Niger Delta. Shell Petroleum���s own records depict an annual company average of 221 spills in its area of operation since 1989���of course, the true figure is likely to be far higher.

Despite these admittances, Shell maintains that sabotage by local vandals is the primary cause of spillages. While the recent result of the 13-year dispute between the multimillion-dollar oil conglomerate and four local farmers goes some way to shifting mainstream narratives of who is to blame, surface wins are simply not enough to generate sustainable change. Shell and its counterparts must overtly accept responsibility for horrors that result from their quests for profit, and such acknowledgements must be paired with actionable plans of regeneration. This is the very least that should be done to begin rectifying the unquantifiable level of social and ecological harm that has occurred across the past several decades.

Despite publicly declaring their commitment to open and honest accounting, Shell and British Petroleum (BP) have lobbied extensively against this, having successfully overturned rules relating to compliance with revenue-spending transparency in the industry. The well-reported execution of Ken SaroWiwa goes to show the brutal reality of the power that these economic actors have in suppressing opposition. What is more shocking, though, is the audacity of criminal corporate players in framing themselves as community saviors, human rights crusaders, or pioneers in sustainability.

Political actors, too, play a fundamental role in the realization of economic crime in the Delta and beyond, with estimates at more than $500bn in oil revenues looted by Nigerian political leaders (since independence), who use their power and access to public office for social, economic, or political private gain. Nigeria has become an infamous example, with the creation of a class of politically elite so-called ���Godfathers,��� who dictate from the head of substantial patronage networks. At the most fundamental level, the state and the ruling capitalist class collectively harness their institutional power to reproduce social relations and uphold the status quo. In Nigeria, governmental elites engage in the suppression of tribal communities, colluding with oil companies and the military, united by a desire of incessant capitalist expansion and personal riches.

Harms produced, then, are not due to erroneous conduct of either party, but rather central to their very essence and purpose, driven by a search for profit and growth. By virtue of neoliberal logic, the far-away degradation of the Niger Delta���s immense ecosystem can be signed off as an inevitable by-product of profit and accumulation by Shell���s directors in the West. Local governments and international organizations are indivisible from corporates in these interactions, since they actively maintain the global economic order through the elevation of neoliberal ideology, market creation, and portraying corporate prosperity as serving the national interest.

Powerful actors��� ability to influence or dictate regulation is paramount to the proliferation of economic crime; many have commented on the ���revolving door��� between regulator and regulated. Yet, this regulator/regulated dichotomy overlooks the crucial fact that regulatory bodies essentially exist to serve the same purposes as states and corporations: the conflict-free reproduction of a capitalist world order. The majority of international regulatory treaties are formed in rooms dominated by voices representing the interests of the global North, perpetuating unequal power dynamics, and leading to political practices increasingly recognized as environmentally racist. In this sense, the law often acts as the ultimate protector of capital accumulation, and a fundamental driver of criminal societal harm.

The majority of existing efforts to curtail eco-crime (especially solutions pushed by powerful neoliberal winners) seek a ���greener capitalism,��� aspiring to regulate inherently environmentally damaging practices. These policies, not dissimilar to remediation settlements like the one mentioned at the start of this piece, ultimately become harm-producing, insofar as they legitimize the marketization of socially damaging practices. Under these conditions, governance success is measured by a mere reduction, rather than elimination, of harm. Regulatory frameworks in a capitalist system frequently subordinate the needs of the poor majority to the interests of the economically powerful, whose unyielding ability to subject society to criminal harm often goes legally unchallenged. This tendency is blatantly evidenced in Shell���s most recent Sustainability Report, which claims that if avoiding adverse social and environmental outcomes is ���not possible,��� strategies are employed to minimize impacts.

When it comes to prosecution, the tale endures. Criminal justice systems ���are inevitably manned, controlled and operated by, and in the interest of, members of the ruling class who have a vested and entrenched interest in sustaining and even extending corrupt practices.��� They are built with an inherent propensity to evade the prosecution of the powerful. There are some exceptions to this general tendency; on occasion, it is necessary for justice systems to engage in symbolic acts to display their functioning. In these instances, regulatory bodies will identify and punish corporate violation, subordinating one entity���s immediate needs to meet the long-term demands of capital en masse, whilst also assisting in the legitimization of the justice system as a whole.

In the Niger Delta, tougher regulations, penalties, and sanctions will be inadequate to generate positive outcomes for local people. This is proven by the extensive amount of regulatory treaties applicable to the region, which have been limited in creating meaningful change for communities. The act of regulating an inherently damaging practice underscores the deep-rooted problem posed by the current politico-economic paradigm. Normative economic reform will simply reinvent the way in which the powerful generate harm. Attempts to restore the natural systems of the Delta are themselves swimming against a tide of prevailing neoliberal ideologies that will ultimately undermine efforts to ���green��� the extractive industry.

It remains that institutional actors��� hegemonic position advances the propagation of economic crime. Maintenance of the neoliberal economic order is crime-enabling, because peaceful social reproduction serves vested interests of a powerful minority class, who fail to operate according to society���s wider needs. In Nigeria���s Niger Delta, such conditions have resulted in an enduring struggle by local communities to obtain a fair, comfortable, way of life.

Two tales against neocolonialism

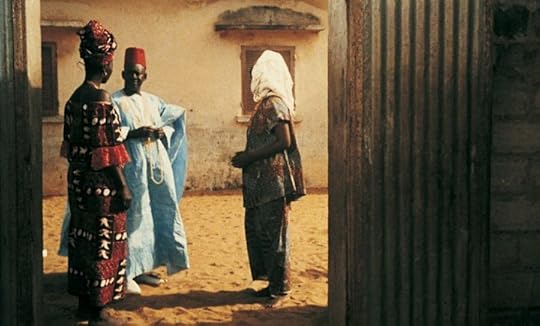

Still from Mandabi.

Still from Mandabi. The film Mandabi (1968) is based on a novel of the same name written by Ousmane Sembene. Set in the early days of Senegal���s independence, it tells the story of Ibrahima Dieng (Makhour��dia Gu��ye), an unemployed middle-aged Dakarois man, whose wives Aram and Mety one day receive a money order from their nephew, Abdou, who works as a street sweeper in Paris. Over the course of the film, Ibrahima goes from one bureaucratic office to another, encountering many relatives and friends on his way, as he tries to get the correct papers in order to cash the money order. Ultimately, he is deceived by a relative, the suit-wearing Mbaye, who swindles him out of the money as well as forces him to sell his house to pay off his debts.

Mrinal Sen���s film Interview (1970) is an adaptation of a story written by Ashish Barman. Set in late-1960s Calcutta, against the backdrop of the Naxalbari uprising, the plot follows Ranjit Mallick, who works as a writer for a left-wing publication, but is looking for a more lucrative source of income. Ranjit���s uncle, a picture of middle-class ���dignity,��� finds him a job with a British firm, and all Ranjit has to do is to show up to the interview in a Western-style suit. The film then follows Ranjit���s attempts to procure such a suit in the chaotic streets of Calcutta, reeling from economic strife. His quest ends in failure, and he does not get the job.

The similarities between these two narratives are plain to see���both are stories about the struggles of an emergent postcolony, depicted through the struggles of working-class men trying unsuccessfully to integrate themselves into the economic setup around them. Not only are the protagonists in both cases vying for some share of foreign money (the money order in Ibrahim���s case, the job with the foreign firm in Ranjit���s), but also their attempts are rendered futile by the end of the movies. This points to an important dynamic in the postcolonial contexts of Senegal and India���that the political promises made to working-class sections of the society were eroded over time due to powerful neocolonial influences (of France and Britain), and a compromise struck whereby a Westernized middle-class was financially enriched at the expense of a politically expedient and economically over-exploited working-class.

Still from Interview.

Still from Interview.The economic contexts of postcoloniality, in Senegal and India, were similar. Both countries came to independence through movements that are not traditionally understood as radical, in contrast to revolutionary struggles for independence in other colonized countries such as Vietnam, Algeria, or Angola. In both contexts, a political party sought to form a wide-ranging coalition that cut across left/right and ethno-religious differences. The Union Progressive Senegalaise and the Indian National Congress were at once was dependent for finances on wealthy, landed, powerbrokers (the landlords of India and the marabouts of Senegal) and paid lip-service to left-wing organizations and ideologies like peasants��� organizations (Mamadou Dia���s rural socialism and the Societes Indigenes Prevoyance in Senegal; the All India Kisan Sabha in eastern India) and trade unions (the Rassemblement Democratique Africain in Senegal and the All India Trade Union Congress) in order to retain mass support. Such a complex alliance naturally made the governments, in both cases, resistant to promulgating wide-ranging land reforms, ultimately stalling the road to industrialization, and leaving them dependent on the influx of foreign capital for development.

Within these strikingly similar economic contexts, Mandabi and Interview show the dangers inherent in the lure of foreign money. The intrusion of the French money order transforms all the social relations that Ibrahima Dieng had cultivated around him. Suddenly, all his neighbors can think of is how to obtain some of the foreign money for their own purposes. The desire for the Westernized executive job transforms how Ranjit thinks of himself, and especially of his previous job as a journalist and editor for a left-wing publication. He is unable to resist the British job that requires him to compromise, not only with his economic ideals, but quite physically, with his cultural identity, and don a suit in place of his dhoti-kurta.

Both movies highlight the precarious independence that most of the postcolonial world experienced, and, by shifting the emphasis from ���postcolony��� to ���neocolony,��� foreground the economic networks upon which, ultimately, any such distinction must be based. The ascription of neocolonial agency must be made, not based upon political expediency, but rather, on the amount of economic influence that a state and its institutions wield.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers