Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 131

April 20, 2021

More widespread than we think

Image via Euranet on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Image via Euranet on Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. During the anti-globalization movement of the early 2000s, tech collectives such as Riseup and Autistici came into existence to provide autonomous, non-corporate communication tools and ���How-Tos��� for social movements to organize safely and securely with emerging new media. In South Africa, the Right2Know campaign was initiated in 2010 in response to the Protection of State Information Bill, which aimed at weakening the rights of journalists and whistleblowers to access information. As part of their work, R2K has published guides for activists to protect themselves digitally.

To heighten my own digital defense practice, I recently took a virtual workshop offered by the New York-based Tech Learning Collective. This collective provides technology education for radical organizers and revolutionary communities with special attention to underserved groups. These groups, which design tools and training for activists, are not a new occurrence. They have an interesting history across varying political cultures dating back, at the very least, to the national liberation struggles of the 20th century. Let���s take two of these, both armed struggles.

The first was the work of the section technique (technical branch) within the Front de Lib��ration Nationale, the movement at the head of the Algerian struggle against French colonialism. In his essay, ���Ici la voix d���Alg��rie��� (���This Is the Voice of Algeria���), Frantz Fanon describes the section technique���s secret, mobile shortwave radio, whose transmitter was mounted on a moving truck that broadcast revolutionary messages from inside Algeria. The broadcast included information on the fighting, the history of the Algerian people, political and military commentaries, patriotic songs, and religious sermons encouraging commitment to the country���s freedom and independence. To listen to the revolutionary broadcast, most Algerians had to get their hands on radio sets designed by Algerian radio technicians, who had started opening shops for the sale of secondhand radio sets. The technicians had innovated in producing battery-powered radio in a country that, for the most part, lacked electrification. Fanon suggests that the purchase of these radio sets did not mean ���the adoption of a modern technique for getting news, but the obtaining of access to the only means of entering into communication with the Revolution, of living with it.��� In other words, Algerians were not simply listening to the broadcast or adopting an information technology for narrow instrumental purposes; rather, something changed in their disposition as a result of their participation in the broadcasts as listeners.

When French authorities understood the power of the Voice of Algeria as a force coming from outside the disciplinary mechanism of the colonial state, they passed a series of laws to prohibit the sale of radio sets to Algerians in order to restrict their access to the broadcasts. Further, as French forces were unable to take hold of the transmitter���they tried to bomb the truck that carried it, with no success���the only way to silence this revolutionary voice was to try to jam the airwaves. But even with French jamming attempts, the existence of the revolutionary broadcast was sometimes more important symbolically than being able to grasp its every word and sentence. Every evening, ���Algerians would imagine not only words, but concrete battles,��� Fanon says, thereby strengthening the national consciousness. The Voice of Algeria became a tool for the revolution not only through its technical branch���that is, its broadcast content���but also performatively, as the mere technical possibility of the broadcasts, against all odds and attempts to suppress, confirmed that the revolution was alive.

The second example comes from the technical committee that supported the South African national liberation struggle. From the late 1950s until the early 1990s, a technical committee developed technical artifacts and trained freedom fighters and their foreign comrades on how to use these tools to support the struggle. The technical committee���s approach to science and technology was influenced by major Cold War events such as the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957. It was not only state actors, such as the American government, that were influenced by Sputnik 1, sparking an ambitious scientific and technological research program that would lead to the creation of the Internet. The launch would also influence the scientific and technological orientation of a national liberation movement.

After it was forced into exile, the technical committee and its members continued to operate in the United Kingdom. They designed tools for the people such as ���leaflet bombs,��� harmless leaflet launchers which would explode in crowded areas and facilitate the mass distribution of handouts. The first scene from the 2020 film, Escape from Pretoria, is a good representation of how leaflet bombs worked and how white South Africans and foreigners especially could use their white privilege for the struggle as they easily navigated white areas. The committee also created small boxes containing audio amplifiers connected to tape recorders which would be left in crowded areas, often in townships, by freedom fighters. Thanks to a timing device, these boxes would then play a short, five-minute message once the operative was away.

Probably the most sophisticated project of the technical committee was an encrypted communication system that allowed freedom fighters to communicate secretly and transnationally between South Africa, Zambia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Canada in the late 1980s. Over almost a decade, the technical committee experimented with newly available technologies of the time such as telematics (combining computers and telephones), computer programming, and encryption, while at the same time training freedom fighters and their comrades to operate such systems. These communication systems later came to be included in Operation Vula in the mid-1980s, an operation that aimed to launch a people���s war.

These two examples show how contemporary tech collectives are rooted in a wider history of technical skills, tools, and groups supporting past and current struggles. In fact, the practical investment of national liberation struggles with science, technology, and communication are practices that might be more widespread than we think. Only by digging further into these radical science and technology traditions across varying political cultures will we have access to a different set of materials and ideas to think about what revolutionary science, technology, and communications can do.

April 19, 2021

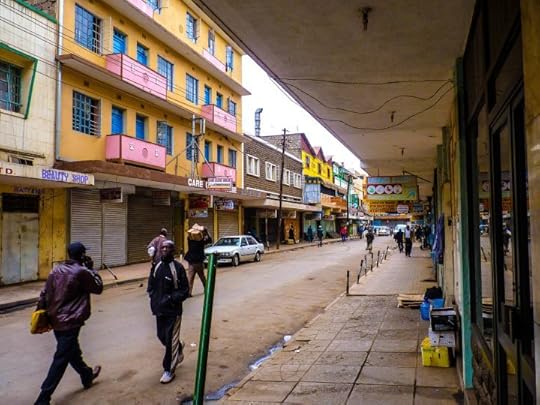

The hustlers of Nairobi

Downtown Nairobi. Image credit James Hammond via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Downtown Nairobi. Image credit James Hammond via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. Why is Nairobi���s government ���terrorizing��� hustlers around the city? This question has been pondered by many development practitioners and scholars over time. In order to answer it, this piece explores the historical lens precedent set by anthropologist Wangui Kimari and positions the urban hustle as another form of the provisional urban world described by Prince Guma.

In “Harnessing the ���hustle,'” a special issue of Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute, hustling is conceived as a political-economic language of improvisation, struggle, and solidarity. This broad definition sends the message that hustling is a survival strategy. The definition also raises the question of why hustlers must improvise in the first place. Tatiana Thieme, Meghan Ference, and Naomi van Stapele in the same issue describe hustling as “a mood, an action, a positioning, and a condition,” which shows that to understand and define both the concept and term one must understand the history and context in which this happens. This is certainly needed when discussing the hustle in Nairobi���s central business area.

Demolitions of residential and business structures have been a common feature of Nairobi since the 1920s, when the colonial authority demolished ���African villages,��� a handful of them in order to make the city habitable for the empire that is racially, spatially, ecologically, and economically divided. In 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic and in the middle of a rainy season, a number of government demolitions brought added suffering to the residents of Kariobangi and Ruai. The government always backs such actions by calling the structures ���illegal���, a word we can easily substitute with informal. This argument helps the authorities to maintain the colonial construct of segregating many of the inhabitants from the ���formal��� activities of�� the city. The informality claims reinforces what Prince Guma describes as “hegemonic narratives or modernist imaginaries of what a city should be or look like.” This consequently necessitates improvisation by the secluded inhabitants in a bid to not only survive but to be part of the city makers.

The hawkers around Nairobi���s central business area are among the peons that the city has long considered other than critical city makers. These traders are always in running battles with the authorities and the government has tried on many occasions to “formally” relocate the traders to locations on the outskirts of the city, locations that any entry-level business class would categorize as un-strategic. This kind of social spatial erasure is predicated on the colonial hegemony that the authority was founded on. Examples of previous battles with other hustlers are not difficult to cite, including the criminalization of the matatu���the informal transportation system in place until 1973 when the then president Jomo Kenyatta decriminalized it. The battles show what Kim Dovey and Ross King call ���interstitial, where informal space rubs against the formal.” They echo the dynamic of improvised survival strategies that emerge and are vital for navigating provisional urban worlds systems that are imposed on the majority of poor, urban residents.

Nairobi���s particular context���its colonial legacy and seat as a bedrock of racial capitalism���has not prevented the very resilient hawkers from taking charge of their hustles, or their city. Hustling in Nairobi is born of urban marginalization and underinvestment in infrastructure, resources, and jobs. General observance and interactions with the hustlers confirm that they come from diverse groups and ages���most of them urban youth who are disproportionately excluded. One such trader is Kelvin, a resident of Mathare and a daytime student at the University of Nairobi. Kelvin spends evenings selling clothes in the central business district�� to contribute to the family income. The merchandise he sells is ever-changing depending on availability of stock at Gikomba market, where he sources the goods. Kelvin���s daily routine is reflective of Nairobi���s provisional urban livelihoods. His hustle also shows what Guma and Jochen Monstadt describe as varied possibilities of cities��� endogenous innovation capabilities.

In closing, a better understanding of history and a true description of the marginalized Nairobi hustlers will help put an end to the one-sided ���inclusion��� narrative and bridge the chasm between a city of elitist dreaming and a real life on the streets.

Exit the bulldozer, enter Mama Samia

Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

Image credit GCIS via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. It is almost certain that Tanzania���s late president, John Magufuli, died of COVID-19 in mid-March, but anyone even hinting as much did so on pain of arrest. What is also certain is that despite all the scolding from the American embassy and the BBC for his retrograde habits of rule, the former president was truly popular in Tanzania. His supporters could point to endless examples of newly upgraded roads, railways, and ���flyovers��� that eased congestion at major intersections. Completing the world���s longest heated oil pipeline will provide Tanzania with a share in Uganda���s oil windfall. Traffic tickets and licenses were no longer problems to be fixed with a bit of ���tea��� for the tillerman. Tax bills were no longer a friendly negotiated price for doing business, but were calculated by government accountants who, although they didn���t always understand the total costs of running a business, could estimate gross revenues that dwarfed civil service salaries. Confronting entrenched connections between businessmen and ruling party politicians required power, and ���the Bulldozer��� was more ruthless than anyone had expected.

With his passing, he has paved a wide-open path for one of the most unlikely presidents of the new century. At her swearing-in as president, the former vice president, Samia Suluhu Hussein, responded to those who might ask, ���Can this woman be the President of the United Republic of Tanzania?��� She told the crowd of political leaders and party cadres ���that the one standing here ��� is the president of the United Republic of Tanzania, in the body of a woman.��� She noted that the former president rarely traveled abroad, and that she had good relations in the international community because she had served as Tanzania���s lead diplomat outside of East Africa. A quiet but tough technocrat in hijab, ���Mama Samia��� managed the traumatic transition with grace and is now taking forceful charge of the government, promoting experienced civil servants and hinting at a more business-friendly regime. There is a cautious hope among opponents of the ruling party that she may take a more humane attitude toward criticism and the virtues of multiparty politics, and she has already created a new scientific task force to address the pandemic that her predecessor had ignored when he wasn���t mocking vaccines and prescribing quack cures.

A couple of years ago, I took an upcountry bus out of Dar es Salaam. A few hours into the journey, we pulled into one of the weigh stations along the heavily trafficked highway that runs westward to Zambia. In the last decade, these weigh stations had slowly come back to life. They offered the road���s thin layer of asphalt���and the centuries-old route underneath it, pioneered by porters and slave traders, missionaries and colonial armies���some protection from the massive double- and triple-hitched cargo trucks grinding their way along. In the 21st century, the two-lane road was cut with deep ruts and sedan-swallowing potholes that marked the disparity between the engines and the engineering. The first-term president, John Magufuli, was a former minister of works, famous for firing contractors and telling builders to start all over if their quality did not pass muster. Our bus was stopped at the weigh station for being overloaded with cargo in the luggage hold. In previous administrations, this infraction may have been easily fixed with a small bribe that the bus company took as the cost of doing business and that the weigh station operator saw as a friendly tip for his concern about the passengers��� prompt arrival. On this occasion, the station operator was apologetic, with dozens of irritated passengers milling about. He was not angling for a bigger bribe���if it were up to him, he���d just let us go���but if we were weighed again up ahead and were overweight, it would be said that he was lax in his job, possibly even corrupt. The only solution was to unload some cargo. Eventually, a businesswoman reluctantly allowed her massive, wrapped bundles to be unloaded and to spend the night at the weigh station, with the promise that tomorrow���s bus would pick them up. People grumbled but understood. This was a new, much needed, administrative culture where rules were rules, at least at the level of highway weigh stations.

Magufuli was an ���accidental��� president in 2015, coming to the fore when ruling party-connected factions chose him as a compromise candidate untainted by the corruption of original frontrunner Edward Lowassa, who promptly shifted to the opposition. Magufuli surprised the ruling elite when he took in hand the reins of a political system that retained the essential structure of a socialist party-state. He made a show of exposing ghost workers, confronting corruption, and arresting opposition politicians and critical journalists. Locally, his model resembled that of Paul Kagame in Rwanda, who rationalized his censorious state with the legacy of genocide. Globally, he followed the lead of Xi Jinping in China, who offered the Chinese model of a one-party state that provided rational overlordship, facilitating economic growth and keeping big business in line. Compared to the political gridlock and misinformation plaguing Western democracies, 1970s-style bureaucratic authoritarianism seemed like a means of breaking the corrupt and inefficient habits plaguing government and business alike. But when Magufuli spent nearly a billion dollars to buy a fleet of brand-new jets for the money-losing national carrier, critics reasonably wondered whether government-run businesses could be responsible stewards of taxpayer money. The latest auditor general report indicated gross mismanagement at the airline and the possibility that its planes could be impounded by foreign creditors. Magufuli had directed all government business toward the new Air Tanzania, which mostly poached routes from an unglamorous, locally based private carrier, Precision Air. With a modest business model built upon the diligent maintenance of its own staff and workaday propeller planes, Precision had profitably plied East African skies for three decades before facing large losses in recent years.

One of Magufuli���s first actions in 2015 was to fire the head of the port authority after a surprise visit by his prime minister uncovered nearly 3,000 missing shipping containers. Within a week of taking office, Suluhu has ordered an investigation of the port authority and fired its current director, a chief tax collector, and her predecessor���s spokesman; the last of these was also the director of the communications authority which had become notably censorious during Magufuli���s presidency. She replaced them all with experienced civil servants, and some of her targets suggest that her predecessor���s showy housecleaning may not have been as effective as advertised. President Suluhu is proceeding with businesslike efficiency. Rather than making surprise visits to hospitals and construction sites, the new president has been remaking the cabinet to her liking. Administrative shuffling is the key power wielded by Tanzanian presidents in a country ultimately ruled by institutions, political parties, and governmental ministries���not by individuals.

Power in Tanzania is bureaucratic, and when the former president���s death was announced, opposition figures made firm calls for prompt transition according to constitutional procedure, which is what happened. The Tanzanian press and political opposition have expressed hope that the new president will bring a technocratic and more democratic approach to the presidency. Tundu Lissu, the presidential candidate who represented a coalition of opposition parties in the last election, has expressed the same hope, but is reserving judgment precisely because power does not reside solely in the presidency but in the party that has retained power for all of Tanzania���s independent history. Lissu was the target of an assassination attempt in a guarded government compound for ministers of parliament in 2017, which he believes was ordered from the top, and which was only the most egregious of a pattern of police killings,disappearances, and harassment of critics and opposition figures. Samia Suluhu, as vice president, was the only representative of Magufuli���s administration to visit Lissu in the hospital.

Despite her quiet bureaucratic allegiance to her former boss, Suluhu showed moments of independence even as vice president, bucking his revival of the policy of expelling pregnant girls from school. She is now taking a more scientific approach to the COVID-19 pandemic and hinting that she will ease some of her predecessor���s more authoritarian policies towards the press. ���We should not ban the media by force,��� Suhulu said recently. ���Reopen them, and we should ensure they follow the rules.��� Whether she will release investigative journalists who have not been seen for years remains an open question. The business community is pleased with her surprise choice for vice president, Phillip Mpango. Another career civil servant, Mpango was willing to act independently of the party���s intimidating factions and favorites. In 2018, he publicly upbraided the powerful regional commissioner for Dar es Salaam, Paul Makonda, for his refusal to pay taxes on 20 containers of furniture that were ostensibly donated for schools, hinting that he would resign if forced to back down. ���I took an oath to enforce tax laws and I will not waver,��� said Mpango when he was Minister of Finance and Planning under Magufuli. ���On that I���m ready to ask the president ��� that that���s it. It���s enough ��� The rule of law must prevail. We will not victimise anyone nor will we fear anyone when it comes to enforcement of taxes.���

In February, Mpango was filmed coughing through a press conference. He recovered but was hospitalized long enough that Magufuli had to counter premature rumors of his death during the requiem for another aide, the chief secretary John Kijazi, who had just died after a two-week hospitalization ostensibly for a heart attack. On February 27, the day before he disappeared from view, Magufuli appointed the leftist academic, Bashiru Ally, as the new chief secretary, and some expected that Suluhu Hussein would appoint him as her vice president. Despite a lack of political experience, Ally had served as general secretary of the ruling party, appointed by Magufuli to replace one of the party���s more effective administrators, Abdulrahman Kinana. Kinana had shepherded Magufuli to victory in 2015 but resigned in 2018, around the time Lutheran, Catholic, and Muslim religious leaders protested the government���s authoritarian turn. Last year, Kinana and several other party veterans were censured by the party for allegations of conspiring against the president. So when Magufuli fell sick in late February, Bashiru Ally was shifted from the party into the state house as a loyal caretaker to replace Kijazi, who had died on February 17. That was also the day that the renowned opposition figure Maalim Seif Hamad, then serving as vice president in a power-sharing government in Zanzibar, passed away. Hamad told the world that he had COVID-19 and warned people to be careful. Despite his willingness to confront the political establishment, Seif Hamad was a stabilizing influence, always willing to cool down Zanzibari opposition supporters and negotiate with the government for peaceful democratic progress. Come 2025, his loss will likely be the more palpable one in Tanzania���s political firmament.

April 17, 2021

Football and empire

The English footballer, Stanley Matthews, photographed in Rotterdam in 1962. He visited and played in South Africa regularly since the 1950s through the 1970s, long after South Africa was banned from FIFA (Wiki Commons).

The English footballer, Stanley Matthews, photographed in Rotterdam in 1962. He visited and played in South Africa regularly since the 1950s through the 1970s, long after South Africa was banned from FIFA (Wiki Commons). For most football enthusiasts, the last year of matches and competition bore the stamp of something most people think should be kept out of the sport: politics. After the #BlackLivesMatter protests around the world sparked heightened consciousness of racial injustice, footballing leagues (most significantly, the English Premier League) embarked on initiatives to spread awareness and communicate messages of zero tolerance. Displays of solidarity, like taking the knee, became ritualized, and from these efforts all manner of debate arose around whether this was just toothless PR, a sincere campaign against racism, or an assault on the integrity of sports as something separate from politics.

But as former England football manager Sven-G��ran Eriksson once said, ���There is more politics in football than in politics.��� Rather than separate from society, sports are often a mirror of it���a testament to the prevailing attitudes, to the evolving social and economic relations. If our society has become more globalized, commercialized and unequal, then the nature of sport will develop this way too. As Kenan Malik writes in The Guardian, ���Football is not just about watching 22 people kick the ball around for an hour and a half. What gives football its heart, its soul and its drama, is that every game, every fan, is part of a wider story. Part of a collective memory, an identity, an imagined community.���

The segregated stands of a sports arena in Bloemfontein, South Africa in May 1969 (UN Photo/H Vassal).

The segregated stands of a sports arena in Bloemfontein, South Africa in May 1969 (UN Photo/H Vassal).It is in the interests of the footballing world to project an image of itself as both separate from politics, while simultaneously also being ahead of it. For example, sports boycotts are widely lauded as an effective tool against oppressive regimes, and something which sports players, organizations and their investors are historically inclined to do. In the final analysis, sports emerge in divided societies as a ���great unifier.��� Describing how this narrative plays out in South Africa, the historian Peter Alegi writes:

In the opening act, the consolidation of apartheid in the 1950s inspires sport activists to build an antiracist network seeking to racially integrate national teams, thereby casting sport in the political spotlight. The second act is set in the 1960s and 1970s as the sport boycott ostracizes white South Africa from the Olympic movement, world football, and nearly every other major sport���important symbolic victories in the larger quest for freedom. The third and final act unfolds against the backdrop of apartheid giving way to democracy in the early 1990s. Segregated sport federations merge into unified, nonracial institutions and South Africa���s re-entry into global sport is celebrated with home victories in the 1995 Rugby World Cup and 1996 African Cup of Nations, unleashing a wave of rainbow nationalist euphoria throughout the sports-mad nation.

But what would be the more complicated story? What if, rather than simply being made by politics, football itself was something that made politics too. Writing about the history of white football in South Africa, Chris Bolsmann observes that during apartheid, ���white football players, organizations, and administrators maintained close links with Britain, the Commonwealth and the notion of Empire and were at the forefront of globalizing football.��� So, joining us on AIAC Talk this week to discuss the forgotten entanglement of South African football with English football at the nexus of empire, is Chris Bolsmann.

Chris has just published a journal article on the great English footballer, Stanley Matthews��� long association with South African football. Previously, he had published articles about white professional football in South Africa and about an 1899 tour by a team of 15 black footballers to Europe.��

He is based at California State University Northridge, specializing in the social history of sport. Together with Peter Alegi, Chris co-edited South Africa and the Global Game: Football, Apartheid and Beyond (2010) as well as Africa���s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space and South Africa (2013).

Stream the show the show on Tuesday at 18:00 in Harare, 17:00 in London, and 12:00 in New York on��YouTube.

On our last episode, we considered ���What���s left of the South African left?��� a debate over whether the moment was right for South Africa���s left to form a new party (and if there was even a left to do it), we were joined by Niall Reddy, Tasneem Essop and Mazibuko Khanyiso Jara. That episode is also available on our YouTube channel. Subscribe to our Patreon for all the episodes from our archive.

April 16, 2021

A disturbing story

Rwanda. Image credit lksriv via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Rwanda. Image credit lksriv via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. It is widely believed that following the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which claimed nearly one million lives, Paul Kagame led a group of rebels known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)���based in neighboring Uganda���to oust a murderous regime and usher in an era of peace and stability in Rwanda. In fact, this small landlocked nation in Eastern Africa is today often held up as a model developmental state and a poster child for Western aid.

However, in her soon to be released book, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad, British writer and journalist Michela Wrong debunks the myth that Kagame���s Rwanda is an island of peace and stability in a conflict-prone region. The book, a searing indictment of Kagame���s 27-year rule, reveals the dark underbelly of a leadership that uses fear to hold on to power, and is highly intolerant of dissent.

This is the fourth in a series of books on Africa by Wrong. Her debut book, In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz, describes the final days of Zaire���s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. It���s Our Turn to Eat, her book on a major corruption scandal in Kenya and the whistleblower who exposed it, is a critical examination of a post-colonial state driven by ethnic politics and myopic interests.

Wrong started her journalistic career as an Africa correspondent for Reuters and the Financial Times. Her books have been praised for their unflinching honesty and clarity about a continent that is often painted in broad brush strokes by Western journalists, with little nuance or context. Wrong talks to Rasna Warah about what motivated her to write Do Not Disturb, and why she believes this story needed to be told.

Rasna WarahWhat drove you to write a book about the dark side of Rwanda, considering that it is the darling of Western donors and is held up as a model African country that rose out of the ashes of a genocide?

Michaela WrongI was prompted to write this book by one simple event: the murder of Patrick Karegeya, Rwanda���s former head of external intelligence. Had Patrick not met his death in such lurid circumstances���strangled in a Johannesburg hotel room to which he had been lured by a Rwandan businessman friend���there would have been no book. In fact, the title of the book comes from the sign that Karegeya���s killers hung on the door handle of his hotel room.

I had been following events in Rwanda from a distance, and I���d certainly been intrigued by the��growing signs of disquiet and unhappiness in the RPF���s ruling elite, with a remarkable number of President Paul Kagame’s��trusted aides and military men ending up in exile, being hunted down by the regime’s agents. But Patrick���s murder made me��sit up and think: ���This is a story that isn’t being told, and really needs to be.��� I���d known for years that the reality of life in modern Rwanda was a far cry from the glowing image the regime successfully broadcast abroad; it was uglier and��darker. The disparity was crying out to be explored and exposed.

Rasna WarahWhile the killing of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul led to global outrage, the killing of Rwandan opposition figures in exile does not seem to elicit a similar response. Why do you think this is so?

Michaela WrongThat���s the key question: why is Kagame allowed to get away with it? I think there are several elements to the answer. Western guilt over sitting back and letting the genocide occur in 1994 is one ingredient. Former regime insiders I interviewed remarked on how successfully they could always play the guilt card in Western capitals to silence criticism. The other is Rwanda���s role as a developmental poster child: officials at the World Bank, IMF, DfID, and USAID are desperate for success stories to justify their foreign aid programs, and that���s what Rwanda has come to represent. But ultimately, I would suggest there���s a certain patronizing element at play, which verges on racism. The Great Lakes is a rough neighborhood, the argument goes, with a horrific recent history, and its citizens have gone through so much that they have to lower expectations of their governments and will put up with a level of repression others would not, as long as there���s food on the table. I would question that assumption.

Rasna WarahYour critics might say that your books on countries like Eritrea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya focus on the fault lines in African countries and that perhaps you are too cynical about the continent. Any comments?

Michaela WrongI���ve been covering events on the African continent now since the early 1990s. If you take a step back, yes, one can identify all sorts of massive improvements: the way Africa is now hooked up to the rest of the world, thanks to the internet, mobile phones and cheap travel, impressive education levels, better health care. But if you look at democracy, free speech, at human rights, it often feels like we���re pedalling backwards. In the 1990s we had Mobutu [in DRC, then known as Zaire], Bongo [in Gabon], Biya [in Cameroon] and Moi [in Kenya]. We used to call them ���dinosaur��� leaders. Today the supposedly progressive Renaissance leaders���[Yoweri] Museveni [in Uganda], Kagame, Isaias [Afwerki in Eritrea]���have turned into dinosaurs in their own right:�� impossible to shift, surrounded by sycophantic cronies, filling their bank accounts, clamping down on the opposition (and Biya, amazingly, is still in situ).

I get nervous making sweeping generalisations about Africa, because the continent is just too diverse. I find it more helpful to look at the specific countries I���ve focused upon in my books and know best: DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, Eritrea. And when I do that, my heart does not lift with cheerful optimism. The key point is that it doesn���t really matter what a white Western writer thinks about what the last few decades have achieved in those various African nation states; what matters are the views of the citizens of those countries. And there���s plenty of dissatisfaction and restlessness there, which I���m echoing in my writing. Having said all that, there���s the old saying, ���happiness writes white.��� If these were happy, well-run societies, there would be little to say. As a reporter, or a non-fiction writer, you���re always going to be more interested in what goes awry. That���s true of any society, whether I was writing about the UK, Italy, or Rwanda.

Rasna WarahWhat stood out the most for you in terms of the human rights record (or lack thereof) of Kagame���s regime?

Michaela WrongNo dictator tolerates criticism well, but what���s striking about Kagame���s regime is that it appears to have no baseline of acceptance at all: any challenge, any criticism is regarded as utterly unacceptable. And what���s really gob-smacking is how far Kagame reaches geographically to snuff dissent out, not just across his own borders but also in other African countries, such as South Africa, and as far as the US, Canada, Belgium, France, the UK, even Australia and New Zealand. The level of energy and focus that goes into that intimidation and elimination operation is quite extraordinary. Freedom House recently listed Rwanda alongside Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran, Turkey and China as one of the world���s most egregious practitioners of ���transnational repression������countries which ���stand out due to the extent and violence of their campaigns.���

But what I find most sinister about the regime���s approach���because of the echoes it has with Germany under the Nazis or Eastern Europe in Communist times���is the way Kagame���s regime seems to practise a policy of collective punishment. So if you just happen to be the distant cousin or an in-law of someone who has been deemed an enemy of the state, you too are suspect, even if you haven���t had any contact for years and don���t share that person���s political views in any way. No matter, you are tarred, too. And so you get these humiliating

���To whom it may concern��� letters, in which Rwandans will publicly distance themselves from old friends or members of their family in order to try and escape state punishment. That���s so sinister.

Rasna WarahDo you have fears that the Rwandan government might also target you?

Michaela WrongYou can���t spend nearly five years interviewing individuals who have been tracked, threatened, detained without charge, shot at, persecuted even once in exile and warned by foreign police forces that their lives are in active danger without coming to share some of their nervousness. The fear that permeates the Rwandan diaspora is tangible, and infectious. But as a Western foreigner, I obviously have less to fear ���my government might take less kindly to one of its citizens being treated in the same way. I���m expecting a counter-blast, but it will probably take reputational form. Kagame employs a small army of social media trolls and there���s already an hourly torrent of abuse on Twitter, much of it coming from anonymous sites, which I am pretty sure are run by Rwandan intelligence. I���m being accused of being a genocide denier, a racist, a colonialist, of having been the former concubine of Patrick Karegeya and of having worked for the French military. It���s not pleasant, but I���ve been insulted like this for years: the books I wrote about the Kenyan whistleblower John Githongo and Eritrea both triggered similar accusations. You just have to shrug and move on. The world would be a much healthier, saner, nicer place if Twitter made it impossible to open anonymous accounts. If Twitter only took that simple step, we���d suddenly be able to see clearly the dictatorships that actually loom behind all these supposedly heart-felt personal accounts.

April 15, 2021

Geographies of war-making in East Africa

Public Domain image, credit Stuart Price for AMISOM.

Public Domain image, credit Stuart Price for AMISOM. In late January, reports circulated on social media about a suspected US drone strike in southern Somalia, in the Al-Shabaab controlled Ma���moodow town in Bakool province. Debate quickly ensued on Twitter about whether the newly installed Biden administration was responsible for this strike, which was reported to have occurred at 10 p.m. local time on January 29th, 2021.

Southern Somalia has been the target of an unprecedented escalation of US drone strikes in the last several years, with approximately 900 to 1,000 people killed between 2016 and 2019. According to the nonprofit group Airwars, which monitors and assesses civilian harm from airpower-dominated international military actions, ���it was under the Obama administration that a significant US drone and airstrike campaign began,��� coupled with the deployment of Special Operations forces inside the country. Soon after Donald Trump took office in 2017, he signed a directive designating parts of Somalia ���areas of active hostilities.��� While the US never formally declared war in Somalia, Trump effectively instituted war-zone targeting rules by expanding the discretionary authority of the military to conduct airstrikes and raids. Thus the debate over the January 29 strike largely hinged on the question of whether President Joe Biden was upholding Trump���s ���flexible��� approach to drone warfare���one that sanctioned more airstrikes in Somalia in the first seven months of 2020 than were carried out during the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, combined.

In the days following the January 29 strike, the US Military���s Africa Command (AFRICOM) denied responsibility, claiming that the last US military action in Somalia occurred on January 19, the last full day of the Trump presidency. Responding to an inquiry from Airwars, AFRICOM���s public affairs team announced:

We are aware of the reporting. US Africa Command was not involved in the Jan. 29 action referenced below. US Africa Command last strike was conducted on Jan. 19. Our policy of acknowledging all airstrikes by either press release or response to query has not changed.

In early March, The New York Times reported that the Biden administration had in fact imposed temporary limits on the Trump-era directives, thereby constraining drone strikes outside of ���conventional battlefield zones.��� In practice, this means that the US military and the CIA now require White House permission to pursue terror suspects in places like Somalia and Yemen where the US is not ���officially��� at war. This does not necessarily reflect a permanent change in policy, but rather a stopgap measure while the Biden administration develops ���its own policy and procedures for counterterrorism kill-or-capture operations outside war zones.”

If we take AFRICOM at its word about January 29th, this provokes the question of who was behind that particular strike. Following AFRICOM���s denial of responsibility, analysts at Airwars concluded that the strike was likely carried out by forces from the African Union peacekeeping mission in Somali (AMISOM) or by Ethiopian troops, as it occurred soon after Al-Shabaab fighters had ambushed a contingent of Ethiopian troops in the area. If indeed the military of an African state is responsible for the bombing, what does this mean for our analysis of the security assemblages that sustain the US���s war-making apparatus in Africa?

Thanks to the work of scholars, activists, and investigative journalists, we have a growing understanding of what AFRICOM operations look like in practice. Maps of logistics hubs, forward operating sites, cooperative security locations, and contingency locations���from Mali and Niger to Kenya and Djibouti���capture the infrastructures that facilitate militarism and war on a global scale. Yet what the events of January 29th suggest is that AFRICOM is situated within, and often reliant upon, less scrutinized war-making infrastructures that, like those of the United States, claim to operate in the name of security.

A careful examination of the geographies of the US���s so-called war on terror in East Africa points not to one unified structure in the form of AFRICOM, but to multiple, interconnected geopolitical projects. Inspired by the abolitionist thought of Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who cautions activists against focusing exclusively on any one site of violent exception like the prison, I am interested in the relational geographies that sustain the imperial war-making infrastructure in Africa today. Just as the modern prison is ���a central but by no means singularly defining institution of carceral geography,��� AFRICOM is a fundamental but by no means singularly defining instrument of war-making in Africa today.

Since the US military���s embarrassing exit from Somalia in 1993, the US has shifted from a boots-on-the ground approach to imperial warfare, instead relying on African militaries, private contractors, clandestine ground operations, and drone strikes. To singularly focus on AFRICOM���s drone warfare is therefore to miss the wider matrix of militarized violence that is at work. As Madiha Tahir reminds us, attack drones are only the most visible element of what she refers to as “distributed empire������differentially distributed opaque networks of technologies and actors that augment the reach of the war on terror to govern more bodies and spaces. This dispersal of power requires careful consideration of the racialized labor that sustains war-making in Somalia, and of the geographical implications of this labor. The vast array of actors involved in the war against Al-Shabaab has generated political and economic entanglements that extend well beyond the territory of Somalia itself.

Ethiopia was the first African military to intervene in Somalia in December 2006, sending thousands of troops across the border, but it did not do so alone. Ethiopia���s effort was backed by US aerial reconnaissance and satellite surveillance, signaling the entanglement of at least two geopolitical projects. While the US was focused on threats from actors with alleged ties to Al-Qaeda, Ethiopia had its own concerns about irredentism and the potential for its then-rival Eritrea to fund Somali militants that would infiltrate and destabilize Ethiopia. As Ethiopian troops drove Somali militant leaders into exile, more violent factions emerged in their place. In short, the 2006 invasion planted the seeds for the growth of what is now known as Al-Shabaab.

The United Nations soon authorized an African Union peacekeeping operation (AMISOM) to ���stabilize��� Somalia. What began as a small deployment of 1,650 peacekeepers in 2007 gradually transformed into a number that exceeded 22,000 by 2014. The African Union has emerged as a key subcontractor of migrant military labor in Somalia: troops from Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda deployed to fight Al-Shabaab are paid significantly higher salaries than they receive back home, and their governments obtain generous military aid packages from the US, UK, and increasingly the European Union in the name of ���security.��� But because these are African troops rather than American ones, we hear little of lives lost, or of salaries not paid. The rhetoric of ���peacekeeping��� makes AMISOM seem something other than what it is in practice���a state-sanctioned, transnational apparatus of violent labor that exploits group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death. (This is also how Gilmore defines racism.)

Meanwhile, Somali analyst Abukar Arman uses the term ���predatory capitalism��� to describe the hidden economic deals that accompany the so-called stabilization effort, such as ���capacity-building��� programs for the Somali security apparatus that serve as a cover for oil and gas companies to obtain exploration and drilling rights. Kenya is an important example of a ���partner��� state that has now become imbricated in this economy of war. Following the Kenya Defense Forces (KDF) invasion of Somalia in October 2011, the African Union���s readiness to incorporate Kenyan troops into AMISOM was a strategic victory for Kenya, as it provided a veneer of legitimacy for maintaining what has amounted to a decade-long military occupation of southern Somalia. Through carefully constructed discourses of threat that build on colonial-era mappings of alterity in relation to Somalis, the Kenyan political elite have worked to divert attention away from internal troubles and from the economic interests that have shaped its involvement in Somalia. From collusion with Al-Shabaab in the illicit cross-border trade in sugar and charcoal, to pursuing a strategic foothold in offshore oil fields, Kenya is sufficiently ensnared in the business of war that, as Horace Campbell observes, ���it is not in the interest of those involved in this business to have peace.���

What began as purportedly targeted interventions spawned increasingly broader projects that expanded across multiple geographies. In the early stages of AMISOM troop deployment, for example, one-third of Mogadishu���s population abandoned the city due to the violence caused by confrontations between the mission and Al-Shabaab forces, with many seeking refuge in Kenya. While the mission���s initial rules of engagement permitted the use of force only when necessary, it gradually assumed an offensive role, engaging in counterinsurgency and counterterror operations. Rather than weaken Al-Shabaab, the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia observed that offensive military operations exacerbated insecurity. According to the UN, the dislodgment of Al-Shabaab from major urban centers ���has prompted its further spread into the broader Horn of Africa region��� and resulted in repeated displacements of people from their homes. Meanwhile, targeted operations against individuals with suspected ties to Al-Shabaab are unfolding not only in Somalia itself, but equally in neighboring countries like Kenya, where US-trained Kenyan police employ military tactics of tracking and targeting potential suspects, contributing to what one Kenyan rights group referred to as an ���epidemic��� of extrajudicial killings and disappearances.

Finally, the fact that some of AMISOM���s troop-contributing states have conducted their own aerial assaults against Al-Shabaab in Somalia demands further attention. A December 2017 United Nations report, for example, alleged that unauthorized Kenyan airstrikes had contributed to at least 40 civilian deaths in a 22-month period between 2015 and 2017. In May 2020, senior military officials in the Somali National Army accused the Kenyan military of indiscriminately bombing pastoralists in the Gedo region, where the KDF reportedly conducted over 50 airstrikes in a two week period. And in January 2021, one week prior to the January 29 strike that Airwars ascribed to Ethiopia, Uganda employed its own fleet of helicopter gunships to launch a simultaneous ground and air assault in southern Somalia, contributing to the deaths���according to the Ugandan military���of 189 people, allegedly all Al-Shabaab fighters.

While each of the governments in question are formally allies of the US, their actions are not reducible to US directives. War making in Somalia relies on contingent and fluid alliances that evolve over time, as each set of actors evaluates and reevaluates their interests. The ability of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda to maintain their own war-making projects requires the active or tacit collaboration of various actors at the national level, including politicians who sanction the purchase of military hardware, political and business elite who glorify militarized masculinities and femininities, media houses that censor the brutalities of war, logistics companies that facilitate the movement of supplies, and the troops themselves, whose morale and faith in their mission must be sustained.

As the Biden administration seeks to restore the image of the United States abroad, it is possible that AFRICOM will gradually assume a backseat role in counterterror operations in Somalia. Officially, at least, US troops have been withdrawn and repositioned in Kenya and Djibouti, while African troops remain on the ground in Somalia. Relying more heavily on its partners in the region would enable the US to offset the public scrutiny and liability that comes with its own direct involvement. But if our focus is exclusively on the US, then we succumb to its tactics of invisibility and invincibility, and we fail to reckon with the reality that the East African warscape is a terrain shaped by interconnected modes of power. The necessary struggle to abolish AFRICOM requires that we recognize its entanglement in and reliance upon other war-making assemblages, and that we distribute our activism accordingly. Recounting that resistance itself has long been framed as ���terrorism,��� we would do well to learn from those across the continent who, in various ways over the years, have pushed back, often at a heavy price.

The Black Man with the Bible in his Hand

Photo: Niko Knigge.

Photo: Niko Knigge. Siphuxolo, a close friend of mine, was late, and I was a little bit annoyed with him. We are two different types of people. I am the anxious kind, so I prefer to be at an appointment twenty minutes early. Siphuxolo, on the other hand, relies on his dysfunctional intuition ���to sense the time the bus will come.��� We got to Cape Town���s bus terminal in the nick of time, paid, and sat across three seats, his bag between us. Conversations with Siphu are always political in nature, something we are both worried about. As a social experiment, we once talked about the weather, and believe me���we soon realized that the personal is political, and vice versa. I was raised coloured, he was black. I am gay, he is straight. I am queer, he is cis-het. Allegedly an unlikely pair in the rainbow nation of South Africa. Either way, we were both headed home for the Easter weekend. The same bus, different places. I lived in Atlantis, a coloured settlement created by the apartheid government in the 1970s, and he lived in Witsand, an informal settlement at the entry of Atlantis occupied primarily by black people. Both homes the product of apartheid and democracy in many similar but different ways.

As the bus left Salt River, The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand stood up and greeted us in the name of God. The one and real God, because there is just one God in democratic South Africa, and he is Christian. The moment God was welcomed into the Sibanya/Golden Arrow bus packed with people during a pandemic���because how else must working-class people enter the wealthy city center to provide their labor���Siphu and I glanced at each other. We knew what was going to happen. Pentecostals, and practitioners of Charismatic Christianity, are notorious for preaching on trains and buses.

���Don���t wear a mask. You do not need a mask; you just need the blood of Jesus Christ to cover you. It is not the first time that religion, especially Christianity, has encountered COVID-19 in South Africa.��� One woman in front of him in an industrial-grade mask tried to refute him by saying he should stop spreading misinformation. But God���s self-proclaimed children are good at silencing. ���All you sinners. You sangomas. You prostitutes. It is never too late to come to God. He will forgive you,��� The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand said. Siphu rustled in his seat uncomfortably. I took a deep breath, a familiar sensation building in my stomach. We are used to this. The other people in the bus certainly were, too; it seemed like nobody paid him any attention except the two of us. Like clockwork, as if my stomach knew the vile and poison it would soon keep company with, The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand said, ���If you are a moffie, it is not too late to stop sinning. God will forgive you.��� My stomach lurched; my eyes knew what to do. They knew to glance down so that my eyelids would force the tear ducts closed, so that neither this man nor the other passengers could see the tears I long thought I had cried out. I knew this was coming. This always came. As I glanced at Siphu sitting at my right-hand side, I found him already on his feet. He saw my eyes and told me to move my leg; he wanted to pass into the aisle between the seats. My petitions, out of anxiety and concern that the bus would turn on us, were not enough for him anymore. I know that calling out violence is the right thing to do, but I was scared to call out someone that wielded the word moffie with such godly, masculine authority. But Siphu knew what the word moffie does to gay and queer persons in South Africa. He knew what it did to me. He shuffled past The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand and approached the driver. My stomach and heart were protesting, my eyes still concealing (with decades of practice) the tears that are so often interpreted as guilt and weakness. Siphu returned and, two minutes later, the bus stopped. The driver attempted to address The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand by saying, ���Sorry, sir. Can you please stop? Some people do not like the way you are preaching.��� Silence.

���They are Satanists and wrong-doers, that���s why! Fire! Fire! Fire!���

In shock, the woman in the row of seats next to me declared that the man cannot help it, the holy spirit led him to say what he said. The group of young, colored men at the back, after a day of work, had mixed opinions. One said that The Black Man with The Bible in His Hand should shut up because ���not all of us are Christians,��� while another said, ���we all grew up Christian.��� All the while I could feel the eyes on Siphu and me. Surely, I tell thee, it was Siphu who made the complaint. They probably assumed we were a gay couple. My higher-pitched, melodious voice, with my haggard beard and swinging hips. My queerness. Which seemingly cannot coexist with my friendship with a black cis, straight man. Either way, we were deemed Satanists.

Just last week, the murderer of Lindokuhle Cele was sentenced. He got 25 years��� imprisonment for stabbing Lindo to death. Last week Sphamandla Khoza was stabbed and gruesomely murdered. We have a Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court who weaponizes his Christianity. Pastors who fart on congregants to heal them. The separation of church and state in a democracy works well on paper. Just like my masters dissertation, which tried to map out how Christianity is not always a space of violence for gender nonconforming and sexually diverse peoples, but also a space of resilience and beauty and love. Yet the murders, sexual violence, and abuse still endure.

This Easter weekend happened. The bus ride happened. I called my own research into question. Maybe, in the halls of the University of Cape Town and the University of Edinburgh, I had grown too comfortable with an enemy that kills my kin. Why am I doing this work? I had an ally, a friend, speak up in order to protect me from violence. Yet, we risked other forms of violence. My political consciousness or activism, if you will, experienced a crisis. Do I speak up? If I witness this violence again, because I am destined to, do I say anything? If I keep quiet, because I really do not want to be violated, does it make me a sellout? When God spoke, my body remembered how young children of nine years old spoke with the holy spirit, passed on by their parents, and declared me a ���moffie.��� Years of therapy, years of theorizing gender and sexuality to the point of my Ph.D., and A Black Man with a Bible in His Hand, on a public bus, during Easter, brought me to my knees. To pray? Or because I am just tired? The Black Man with the Bible in His Hand had me thanking God for Siphu and for my ability to recall my breathing techniques when panic attacks swell in my chest. Yet, God had me angry and tired. Angry that the violence and death at the hands of his children. The ones who proclaim moffies and sangomas and ���prostitutes��� as sinners. Passengers on the bus said that we did not want to hear about our sin. Am I a sin to God? Religious interpretation���violence in the name of God���is killing lesbian, gay, trans, bisexual and intersex persons. They might not have killed me on that bus, but have you ever seen a bus full of people, filled with the ecstasy of God? Ready to defend his words to the sinners, to stone, to judge? Those are who we live with, eat with, ride a bus with. How are we safe? How do I make sense of the love and acceptance so many queer people, including myself, have found in religion? In the Christian religious tradition, Jesus Christ rises. He gets to live by divine ordination. We get killed.

April 14, 2021

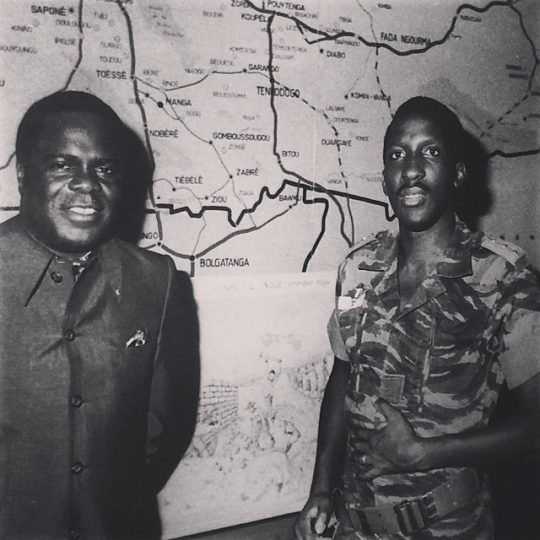

Man of action

Image via Kaysha on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image via Kaysha on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Thomas Sankara���s 1983 to 1987 revolution in Burkina Faso was part of a small group of national, radical political movements in the global south during the heady but volatile 1980s. These movements were geared to achieve economic and political independence for their countries as the majority of global south nations oriented their political institutions according to the prescriptions of North American and European patrons and the detrimental economic models of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Union College Professor Brian Peterson���s Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa, published in February 2021 by Indiana University Press, is a timely, engrossing, highly informative history that is as much a biography of Sankara as it is a national memoir of West Africa during the Cold War of the 1980s. Peterson positions Sankara���s revolution as an example of the counter-hegemonic struggles during the 1980s��� neoliberal transition.

In addition to his most recent book and articles on the intersection of Islam and colonial rule in West Africa, Peterson is the author of Islamization from Below: The Making of Muslim Communities in Rural French Sudan, 1880-1960 (Yale University Press, 2011).

I was fortunate to have the following exchange with Peterson via email about Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa.

Benjamin��TaltonIt���s really nice to have your book, Thomas Sankara, in print. I learned so much about Burkina Faso and the domestic and transnational politics of the 1980s from reading it. For those who may not be familiar with Thomas Sankara and his revolution in Burkina Faso, how do you present him in terms of political ideology and leadership? What is his legacy in the context of West Africa���s recent history, the 1980s, the Cold War, and Africa generally?

Brian PetersonIn my book, I tried to present him as a complex individual who, in the most fundamental way, was a self-described patriot. He was completely committed to his people and put his energies into fighting for his country���s political and economic sovereignty. Sankara rejected labels, but there were clearly some main strands to his thought. At the core was his visceral opposition to injustice and a sense of moral outrage at oppression and inequality. This is reflected in his intellectual influences, like Marxism, Catholic liberation theology, and Third Worldist currents of thought. This bundle of ideological orientations was packaged in a highly charismatic individual who, ultimately, was a man of action. In his leadership style, I would emphasize Sankara���s non-conformism and preternatural work habits. I also think he set a high bar in terms of moral rectitude and incorruptibility, and, because of these qualities, Sankara���s legacy in Africa has been mostly positive.

In so many ways, Sankara went against the main political currents of the 1980s. As a revolutionary hero and political icon, he is often viewed as a virtuous political leader who, despite his errors, had the genuine interests of the people at heart. Reading your book on Mickey Leland made me realize how much the two men shared, in terms of their commitment to the people and their positioning within global politics. They both represented powerful counter-hegemonic struggles that were ongoing in the 1980s but have often been occluded by triumphalist neoliberal narratives.

Benjamin��TaltonI also see many similarities between Mickey Leland and Sankara, despite their different political positions and the contexts in which they moved. An obvious similarity is that they died tragic, untimely deaths at a point in their political trajectories where they appeared to be on the verge of launching transformative social and political projects. You write of the tendency in studies of Sankara and his revolution to read events through the lens of his death. Could you elaborate on what you mean by that and describe how your book departs from this practice?

Brian PetersonSure, that���s a great question, and what I mean by that is that the way the revolution ended���with Sankara���s assassination���shaped perceptions of the entire course of the revolution. This singular violent event was so shocking, and demanded explanation, that both Blaise Compaor�� apologists and Sankara���s allies, in their public statements and books, placed heavy attention on the processes leading to his assassination, and this tended to obfuscate the revolutionary process. The various revolutionary actors who opportunistically joined Compaor�����s regime also revised the revolution���s history and heaped excessive blame on Sankara, even as he remained largely admired by the people. So, in response to the official repudiation of Sankara, there was a powerful counter-memory that proliferated as he was kept alive at the grassroots level, especially among the youth. But there���s another component that merits attention, and that is the fallacy that the revolution ended���when in fact things were on the ascent and revolutionary enthusiasm was at its peak. In other words, Sankara���s murder has been framed, especially in popular transnational understandings, as the abrupt termination of an otherwise successful revolutionary project.

But my research shows that Sankara was assassinated just as popular grievances mounted and internal factionalism grew. And, of course, this was against the backdrop of foreign powers��� efforts to destabilize the revolution. So, the revolution had a life of its own, with different interests, internal factions, external pressures, countervailing forces, and many things that were far beyond Sankara���s control. What I���ve done in this book is chart the trajectory of the revolution alongside Sankara���s political career, keeping track of the different moving parts and integrating conflicting views while drawing on new primary research in order to present a more balanced picture of the revolution and Sankara���s life.

Benjamin��TaltonSankara appears as a reluctant Pan-Africanist in your narrative. He regards race, and blackness specifically, as possessing limited political currency and relevance. Yet, you also depict him in Harlem, New York in 1984 delivering a fiery speech to an African American audience where he deploys the rhetoric of black solidarity. How do you characterize Sankara���s internationalist, continental and racial politics and the factors that shaped them?

Brian PetersonThis question really gets at how Sankara evolved as a thinker and statesman. The way I look at it, as Sankara came to see himself more and more as a revolutionary on a global stage, pan-Africanism grew in importance in his public statements. We have to remember that Sankara initially built his political career on fighting corruption, neocolonialism, and poverty within Burkina Faso. He was certainly keen to condemn racism, but comments on racial justice did not have as much political currency with his own people. Yet Sankara evolved over time, especially as he sought to popularize the revolution during his travels around Africa and the wider world, and in time pan-Africanism moved closer to the core of his outlook, as he promoted ideas of African unity in addressing shared challenges. And, of course, his pan-Africanist messages resonated deeply with the African youth. But I also think that Sankara���s sense of ���internationalism��� was even more powerfully rooted in an affinity with the socialist world and Third Worldist ideas of solidarity with countries in the wider global South that were experiencing foreign aggression, unbridled resource extraction by foreign corporations, and various forms of control via international banking institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund.

Benjamin��TaltonRelated to your point about international banking institutions, France���s presence looms large in the events you reconstruct in the book. In post-independence Burkina Faso, it was both a patron and political and economic interloper, among its other complex roles. You describe the repeated efforts by French officials to persuade Sankara to sign with the economic programs of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. How did Sankara perceive and attempt to handle his country���s relationship with France?

Brian PetersonYes, definitely, and it���s quite a yarn to unravel. I think that Sankara had a complicated, even ambivalent, relationship with France. At different points in this history, France did try to work with Sankara, and even tolerated quite a bit of revolutionary rhetoric targeting France. But Sankara expected to be treated as an equal, a peer head of state of a fully sovereign country. He refused to accept his country being a vassal in a neocolonial relationship of domination. However, there were risks involved on this path���opposing debt repayment, criticizing foreign aid, publicly attacking France, and so forth. As I see it, Sankara knew that he couldn���t break with France completely, and the CNR [The National Council for the Revolution] was still depending on foreign aid, especially from France. A transition to greater autarky would take time, and in four short years, this wasn���t possible. My research shows that it was Sankara���s reluctance to accept an IMF agreement in 1987 that led to many economic problems and loss of political support within the CNR. Moreover, from the moment Sankara emerged as a political force in 1983, France had been trying to remove him from power. France finally succeeded in October 1987, when an array of French economic pressures, intelligence operations, diplomatic maneuvers, and disinformation campaigns in the French press paved the way for his overthrow.

Benjamin��TaltonWhile these forces were converging to undermine Sankara and his policies, his government developed special programs that aimed to improve the economic and social position of Burkinab�� women. Who were some of the women in key roles in the revolution and in Sankara���s government?

Brian PetersonAbsolutely, one of the most progressive actions by the revolutionary state under Sankara was to give more political power to women by bringing them into government at all levels, from the local Revolutionary Defense Committees (CDRs) to ministerial positions. In fact, Sankara implemented a 30 percent quota for all government offices to be filled by women. Among the ten civilian ministers within the CNR, three were women, which included Josephine Ouedraogo as minister of family development, Rita Sawadogo as minister of sports and leisure, and Ad��le Ouedraogo as minister of budget. Moreover, women now served in the military and gendarmerie. Germaine Pitroipa, who was High Commissioner of Kouritenga Province during the revolution, recalled how Sankara worked tirelessly to support his female colleagues, and how he took many of his cues from women in devising pro-woman policies. He also entrusted high priority state actions to women, like when he put Josephine Ouedraogo in charge of the relief operations during the drought and famine of 1984-85.

Benjamin��TaltonIt���s ironic that while Sankara was immensely popular with students, urban workers, and farmers, he did not enjoy the full support of trade unions and student associations. What contributed to his strained relationship with these key constituencies? Did these factors pave the way for the success of Compoar�����s coup in 1987?

Brian PetersonThis observation really gets at one of the more complicated, and often misunderstood, political processes that unfolded across the entire revolutionary period. It���s important to understand that there was intense internal factionalism within the revolutionary leadership, and labor unions and student groups were used as political weapons by Sankara���s opponents. So even as students were still mostly pro-Sankara at the grassroots level, Compaor�����s clique used control over the student groups as a way of opposing Sankara. With the labor unions, because the working class in Burkina Faso was very small, unions mostly represented the interests of civil servants and others deemed ���petty bourgeoisie.��� And during the revolution, the CDR system, which was incidentally controlled at the highest levels by Compaor�����s military loyalists, slowly eclipsed the labor unions, and this generated grievances. But it���s also true that in seeking to redirect more resources to rural areas, Sankara reduced the salaries and privileges of civil servants, thus diminishing their purchasing power and political clout. Compaor�� was able to take advantage of the resulting grievances and wrongly present Sankara as being anti-labor, while absurdly positioning himself to the left of Sankara.

Benjamin��TaltonYou describe countless national initiatives that were part of Sankara���s revolution. He was clearly ambitious and squarely focused on transformative and sustainable development toward a truly independent, self-determined country. Before Blaise Compaor�� launched his rectification program to undo these programs, how would you rate the success of Sankara���s revolution? What were among its outstanding achievements and where was it headed?

Brian PetersonThis is a great question, and I think that when measuring the revolution���s success, we should also look at the sheer difficulty of accomplishing its goals in such a narrow horizon of time. What Sankara was seeking to accomplish would usually have taken decades. That said, Sankara���s entire progressive agenda radically reoriented the state on a wide array of issues, from battling corruption to promoting women���s rights. I think that citizens in Burkina Faso finally felt that they had a state that was responsive to their needs, not just those of political elites or neocolonial interests. We know that the revolutionary state was very successful in wiping out corruption and promoting greater self-reliance while redirecting far more state resources to rural areas, from the rather bloated civil service to the peasantry. This meant a countrywide improvement of basic health care, the ���commando��� vaccination drives, and expanded water access. We can also cite the impressive achievement of food self-sufficiency by the end of 1986, following a devastating drought and famine, and the concomitant shift to sustainable development and environmental restoration, which included mass reforestation drives.

As I see it, Sankara viewed raising political consciousness as the most important long-term task, but admittedly the most difficult. It���s not easy to change how people think, their consumption patterns, or entrenched attitudes around things like gender relations. And Sankara understood that this required a major overhaul of the larger cultural matrix, and there was only so much that any nation-state could do. The revolutionary state certainly launched numerous projects, such as literacy campaigns, building schools, mobile film units, and cultural festivals as a way of providing the scaffolding necessary for ���decolonizing mentalities.��� But this was a long-term intergenerational struggle, and the forces at play transcended the nation-state, both in terms of culture and politics. In the months before his assassination, he redoubled his commitment to the peasantry, and took further steps to raise political consciousness. He also initiated a campaign of revolutionary ���self-criticism��� and of addressing the errors of the revolution. He was responsive to people���s grievances and even called for a revolutionary ���pause,��� a course correction. His enemies saw an opportunity, took advantage of his candor, and implemented their coup.

The politics of social welfare

Image credit Randy Greve via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Randy Greve via Flickr CC BY 2.0. ��� Two women in the Eastern Cape

“I imagined that when he [her son] was born, it would solve all the problems in our relationship. That the three of us could start a family together.”

“When I discovered I was with child, I was too far in the pregnancy to go to a public clinic, and I couldn���t afford to go to a private one.”

These snapshots are extracted from narratives about pregnancies among young and middle-aged women, collected from research conducted in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Looking back was a painful endeavor, but these women insisted on sharing their stories, even if it meant revisiting memories of betrayal, hardship, guilt, and shame.

The childcare grant is the cornerstone of South Africa���s welfare program, one of the most impressive in sub-Saharan Africa, with different grants currently assisting more than 18 million people. For many of the recipients, grants are the only reliable source of income in an otherwise precarious existence. Grants are also central to the government���s relief measures in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequences of national lockdowns. Existing grants were given a ���top-up,��� together with the introduction of a new COVID-19 grant to ease the impact on people���s health and wellbeing.

Yet, social welfare programs in South Africa are rarely described as success stories. Across media platforms, particularly digital media, one encounters negative opinions ranging from how the large number of grant recipients is a national embarrassment, to how grants instill a dependency syndrome or, as one NGO official told me in confidence, ���it has not only dealt a deathblow to entrepreneurship in the townships, it has also made people lazy.��� But the most pervasive is that girls get pregnant so they can claim the child grant.

Yet, if money were the motivation, avoiding pregnancy would be the more rational strategy. Pegged at R410 rand (less than US$40), the child grant barely covers one child���s monthly needs. Having children equals less money for job-hunting, and together with emotional attachment and responsibility, makes it harder to move around in search of employment. The stories about girls leaving their children in the care of their own parents while keeping the grants for themselves, similarly holds little weight in reality���as if young girls nationwide feel no sense of obligation toward their child. With only a few exceptions, in all cases I recorded the grant card stayed with whoever cared for the child

According to the women I spoke to who were relatively young when they had children, pregnancies were not something they had planned for. Many had themselves been raised by single mothers or grandparents and had been told how young motherhood was not something to be desired. While contraception is accessible at the local clinic or in shops, many confessed to having avoided these options out of a fear of being subject to gossip or moral scorn. Sadly, women still have to negotiate their sexuality against a backdrop of patriarchal notions.

Upon discovering the pregnancy, most of the women confessed to feeling ambiguous about whether to terminate it or not. The decision frequently boiled down to whether they had money to pay for the fare to a public clinic (a particular barrier for women living in rural areas), or for paying for a private procedure if the pregnancy was past 13 weeks. Those who decided to continue with the pregnancy tried to see it as the road to a better life; the birth would be the event heralding a bright, harmonious future. More often than not, this ended in disappointment.

There���s no space for such nuances among those who cling to the myth about grants ���creating children.��� Instead it illustrates how the colonial construction of black sexuality as immoral and socially disruptive prevails. It is a stark reminder of how the debate on decolonization must address perspectives on sexuality and the black body.