Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 127

May 24, 2021

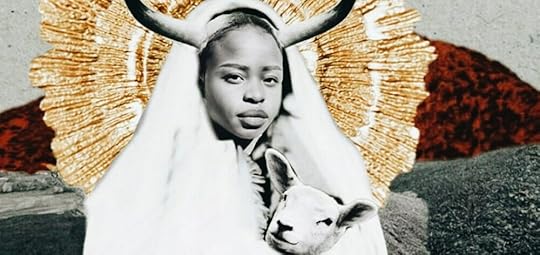

A child of the Rwandan diaspora and the longing for home

The song ���Sabizeze��� tells a story in which a Rwandan king, desiring a son as his heir, banishes his unknowingly pregnant wife. In exile, she gives birth to a son, Sabizeze. Once the king learns of this, he launches a search for his now-grown son and welcomes him home.

The song features heavily in the film, Ndagukunda D��j�� (I Love You Already), a short documentary film directed by S��bastien Desrosiers and David Findlay. The film follows the story of codirector and Qu��b��cois journalist Desrosiers as he meets his estranged Rwandan father (then living in Montreal) and travels to Rwanda in a journey of self-discovery.

The choice of song is apt because of its parallels to the experience of Desrosiers: raised by a white Canadian mother in the absence of his unknowing father, he did not meet his father until he was 28 years old, and was subsequently welcomed to Rwanda by his father���s family.

Central to the 21-minute film are Desrosiers���s discussions of identity and belonging. Early on, he recalls his unwillingness to talk about his father because it would mean ���accepting [his] otherness.��� Later, Desrosiers talks about how he ���played the part of the Black friend��� but felt like an imposter because he was distant from his ���African roots.��� He explains that his journey to Rwanda was about finding acceptance; however, as he reflects on his experience: ���If I thought I was Black in Qu��bec, and that I would … return home to Rwanda … I was dead wrong, because there, to them, I was just a whitey, what they call ���ummuzungu.������ Toward the end of the film, Desrosiers appears to gain the approval he seeks. Reflecting on his conversations with other Rwandans, Desrosiers���s uncle states, ���Do not see him as a stranger. This is our brother. This is our son and our brother … I said, ���Him��� That���s our son. Rwandan just like us.��� They said, ���No. No. He is umuzungu.������ His uncle replied, ���No, no. He doesn���t look like us, but he is Rwandan.���

Such commentary captures Desrosiers���s negotiation of his own self-identification and others��� identification of him. While the film occasionally approaches identity in an essentialist manner, it also captures Desrosiers���s feelings of disappointment about being identified in ways he does not wish to be; his insecurity identifying as African, Rwandan, and/or Black; and his eagerness to belong and have his identity recognized and accepted by others.

The acceptance of Desrosiers���s father and uncle make for a happy if not trite ending; however, such understandings of the film are laid out for the audience in a largely prescriptive way rather than being demonstrated through dialogue and interaction. For instance, the audience is privy to little conversation between father and son. When more naturally occurring discourse is shown, it can be a little awkward. While calling his mother from Rwanda, for example, Desrosiers informs her that he met ���the uncle,��� before correcting himself to ���my uncle.��� While the film approaches Desrosiers���s identification with and belonging among his Rwandan family as a foregone conclusion by virtue of their shared heritage, this small error reveals that identification is a much more complex process. In other words, Desrosiers���s initial identification of his uncle as ���the uncle��� demonstrates that racial, national, or even familial identifications can never be assumed, but are rather products of social practice. I do not fault Desrosiers for this slippage, but I would have welcomed exploration of other instances of mutual discovery and identification.

��The film is also framed as taking place during the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. While unclear who the film���s intended audience is, there is very little history offered about the genocide itself. Desrosiers reveals that his father could not or would not speak about what happened to his family before or during the 1994 genocide. When his uncle accompanies Desrosiers to a genocide memorial, his uncle calmly explains that Desrosiers���s grandfather was killed at what he identifies as the beginning of the genocide in 1963, while his grandmother, aunts, and uncles were killed in 1994. Desrosiers admits that, while he did not know these family members, he feels he owes them ���remembrance.��� But he does not offer an explanation as to why. Indeed, the 1994 genocide itself seems worthy of remembrance, yet it is also presented without context.

Such scenes reveal not only potential differences between talking about the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and in the diaspora, but also the various processes through which the genocide���s memory is encouraged and expected to be taken up by Rwanda���s youth. In one scene, Desrosiers���s father calls his son���s journey ���a bandage on [his] heart.���

Ndagukunda D��j�� is rich with symbolism; however, if Desrosiers travelled to Rwanda to answer questions he asked his entire life, the film also creates more questions than it answers, particularly about identification, belonging, and memory.

May 23, 2021

Exile is more than a geographical concept

A still from "The Colonel's Stray Dogs." The filmmaker Khalid Shamis (left) and his father, Ashur.

A still from "The Colonel's Stray Dogs." The filmmaker Khalid Shamis (left) and his father, Ashur. Last week on AIAC Talk, we featured the poetry of Palestinian and South African writers, a collective meditation on home, exile, and belonging in the wake of Israel���s latest round of brutality against the Palestinian people. A ceasefire now holds, and the world breathes a sigh of relief: many think, ���at least we are now spared daily images of tragedy and loss.��� By the time the truce was announced, Israeli army bombardment killed 243 Palestinians, including 66 children, wounded more than 1,900 and damaged critical infrastructure and thousands of homes, according to news service Reuters. Rockets fired by Hamas, killed 12 people in Israel. Nevertheless, in some ways, the moment can be considered a shift forward for the Palestinians���primarily because this recent episode sparked a common front of resistance across Gaza, the West Bank, and historic Palestine. As noteworthy, is that the Israelis may be losing the war on public opinion in the West, their traditional source of support. Now, high profile members of the Democratic party like Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have condemned Israel as an apartheid state and called for an end to the US giving it millions of dollars in military aid. Along with Senator Bernie Sanders, these progressives have intervened to try and block America���s latest sale of weapons to Israel.�� Tens of thousands have mobilized in Palestinian solidarity in cities like London, New York and Paris, and terms like ���settler-colonialism��� are frequently used to describe Israel���s ethno-nationalist character. But all this is cold comfort for Palestinians. If there���s anything we learned last week, it is that even a temporary or lasting peace cannot heal all wounds for the oppressed and alienated���so to borrow from the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish yet again, ���Exile is more than a geographical concept. You can be an exile in your homeland, in your own house, in a room.���

How the filmmaker Khalid Shamis first encountered his father, Ashur, on British TV. He recognized him by his voice.

How the filmmaker Khalid Shamis first encountered his father, Ashur, on British TV. He recognized him by his voice.This week on AIAC Talk, we���re thinking about exile again.�� A recent film investigates the life and times of an exile, Ashur Shamis. Shamis is an eminent Libyan journalist and long-term political activist who was once a prominent dissident against the dictatorship of Muammar Gaddafi. Like most political detractors, he became a target for the regime and so was forced to flee to London. It was from there that he participated in underground resistance efforts aimed at overthrowing Gaddafi and made a life. The film���s main interlocutor is its director���Shamis��� son, Khalid. The estrangement that comes with growing up in another land, as the son of a man whose dream was always to one day return to his own, is captured when Khalid says in the film���s trailer: ���For the forty years he was in exile in England, it felt like killing Gaddafi was more important to him than living with us.��� In the end, Gaddafi did fall (we know that because it is history) and Ashul Shamis went back to Libya to help rebuild the , but would he be welcome? And did the country move on from him. There���s also all the alliances, secrets and compromises of exile. Considering that Khalid now resides in Cape Town, South Africa���the country where his mother is from���where is home for Khalid? We���re pleased to have the opportunity to ask him, as he���ll be joining us to talk about this film. Khalid is a filmmaker and editor known for films such as The Sound of Masks (2018), The Colonel’s Stray Dogs (2021), and The Silent Form (2016).

“The Less I Know The Better II,” 2021, by Tshepiso Moropa. (Part of The Shape of Blackness).

“The Less I Know The Better II,” 2021, by Tshepiso Moropa. (Part of The Shape of Blackness).In South Africa, despite apartheid ending formally in 1994, there are a myriad of ways in which the country is still inhospitable for its black majority. The persistence of racialized inequality being the chief reason. And in the United States, the end of Jim Crow didn���t usher in full equality and citizenship for black Americans either, compounded by the fact that they are a minority. The international #BlackLivesMatter mobilization of last year has significantly contributed to a heightened consciousness of race and place���as it applies to Palestine, South Africa, the US and elsewhere. Blackness, as a political identity, has always been about going beyond treating race as a natural feature of reality, and understanding racialization (the process by which people come to be identified as ���races���), as intrinsically being an exercise of oppression, of marking the ���Other.�����

In a lecture delivered at the University of Toronto in 2002 called ���The Foreigners Home,��� the late American writer Toni Morrison offers a reflection on the,�� inside/outside blur that can enshrine frontiers, and borders: real, metaphorical, and psychological, as we wrestle with definitions of nationalism, citizenship, race, ideology and the so-called clash of cultures in our search to belong. African and American writers are not alone in coming to terms with these problems, but they do have a long and singular history of confronting them. Of not being at home in one���s homeland; of being exiled in the place one belongs.����

African and American artists have to come to terms with this too. A new virtual exhibition created by Cedric Brown called ���The Shapes of Blackness���, offered a perspective on the black experience by South African and American visual artists���one a black majority nation, and the other a black minority nation. We are pleased to be joined by Cedric, as well as Odysseus Shirindza, one of the exhibition���s curators. Cedric is an Atlantic Fellow for Racial Equality and is an award-winning social impact leader. Odysseus Shirindza is a South African artist and designer and is the director of Gallery MOMO Johannesburg.

Stream the show Tuesdays at 6 pm in Johannesburg, Cape Town, 7 pm Jerusalem, and 12 pm in New York on YouTube.

We are eternally grateful to the writers and poets who appeared on our episode last week, and given the dynamism of the situation, we did not get the chance to name them in its promotion. Many thanks to Mahmoud Al-Shaer, Basman Derawi, Siphokazi Jonas, Rustum Kozain, and Heidi Grunebaum; as well as to Katharine Halls and Adania Shibli for helping with translations. And thanks to Jay Pather for chairing the episode and to PEN South Africa for helping to put it together. That episode is now available on our��YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

May 20, 2021

John Brown had a sick beard

Photo by Florencia Viadana on Unsplash

Photo by Florencia Viadana on Unsplash The images coming out of Charlottesville, Virginia in summer 2017 offer a study in contrast. On the steps of Thomas Jefferson���s university, white men in khakis and undercuts assemble, lit in the August humidity by the soft glow of their absurd prop: garden store tiki torches. Cut to the next day: a car rams through a street full of protesters, captured on shaky cell phone footage in the stark light of day. Rightwing provocateur Richard Spencer���s staged performance had staked its claim: the polo shirts and khakis, the haircut (the undercut, high and tight, the ���fashy������ literary scholar Gr��gory Pierrot has all the names for it in his book Decolonize Hipsters) were a clear statement of political affinity with white ethnonationalism. The injury and death that followed, if not outrightly choreographed, were scripted in the annals of fascism.

The undercut and the long beard had reached something close to ubiquity in the mid-2010s. It was everywhere. In the wake of Charlottesville, it became clear: the cut was compromised. Hipsters had to reckon with the fascist association of their tufted top. But as Pierrot argues in Decolonize Hipsters, his searing analysis of the deep roots of white supremacy and Black exploitation in modern culture, it was already compromised.

Decolonize Hipsters is a handbook, a playbook really, and in it Pierrot breaks down what the hipster has been at since at least the eighteenth century: colonization, extraction, appropriation, gentrification. It is a book that teaches the reader to look at modern culture anew���not through the quizzing glasses of the French Directory or the clear plastic frames of our present day���but through the practice of Black critique. Follow Pierrot and you will see that the ���fashy��� foretold Trump���s rise���the signs were there long before Charlottesville.

The beauty and the force of Decolonize Hipsters is the way Pierrot folds and unfolds the pleats of historical moments to tell a story of race in the Atlantic world. Hipsterdom has deep roots in colonization, Black cultural appropriation, and white supremacy. It is fitting that Pierrot���s book kicks off the series Decolonize That! Handbooks for the Revolutionary Overthrow of Embedded Colonial Ideas, edited by Bhakti Shringarpure. Coloniality is embedded in hipsterdom: the fascination with, scorn for, and theft of Black culture is inextricably tied to the Atlantic slave trade. ���Cultural appropriation wasn���t born in a day, or in twenty-first-century Brooklyn,��� Pierrot reminds us. And so he takes the reader on a tour of the past: from the late 18th-century European fashions of Creole dress, the mid-19th-century Parisian bohemian, to US American cakewalks, minstrel shows, jazz, blues, bebop, and on through Picasso, Portland, The Gap, indie rock, beards, Williamsburg, and the Kardashians.

Pierrot���s journey through hipsterdom���s history of Black cultural appropriation does not merely chart its evolution, he exposes its methods, too. Hipsterdom remains predicated on ���exploiting Blackness���including Black critiques of whiteness���like a bottomless mine.��� For Pierrot, Black cool was born out of the threat of violence and the crafting of tools for survival: ���the communal knowledge that this life in the heart of whiteness is a dangerous game with ever-changing rules.��� This secret knowledge, these subversive tools were incredibly attractive to white outsiders who came to ���discover��� and explain them for a wider white audience. Their finder���s fee was the cool they could now claim as their own, as the hipster is wont to do: ���the original cool peeled and reconstructed by immediate witnesses to the broader circles of the white public��� (see also ���Columbusing,���; ���capitalism���).

The genius of this book is not just in Pierrot���s analysis but in his delivery of it. His mode is decidedly unironic and snark-free. This point deserves emphasis because at first blush a reader might confuse Pierrot���s penchant for humorous nicknames and biting satire with snark (see: ���pillowcase scouts���; ���rapist-in-chief������ but which one? Read to find out!; ���the orange love child of Andrew Johnson and Jefferson Davis���; ���Nappo Number Three,��� etc.). Make no mistake: there is no mocking irreverence here, and Pierrot is dead serious. He trades in facts and history���the book is an uncompromising ledger that shows the hipster, and white culture more broadly, deep in the red.

This doesn���t mean the book is not hilarious because it is! Pierrot���s humor is the kind that refuses to soft pedal for anyone���s comfort. He reveals this kind of accommodation to be part of the problem in the first place: the hipster���s recourse to snark and irony is an insidious dodge. ���Irony,��� Pierrot reveals, ���allows one to eat one���s cake and forever have some left (or, arguably, right). The rebellious stance characteristic of hip and avant-garde can either translate into political action or at least discourse, or remain something short of that, snark without critique. Stay there long enough and you���ll have snark for snark���s sake (say that real fast many times), an outlook that demands that anything serious always be taken down a notch.��� To great effect, Pierrot punctuates the seriousness of his subject���white supremacy, extraction, colonization, fascism���with the hipster refrain: ���Don���t you have a sense of humor?���; ���Jokes, ya know? It was ironic.��� Hipster irony won���t fly in 2021���it can���t fly���not after Trump, not after Charlottesville. The haircut is compromised. The beard, too.

Pierrot���s accounting of the consequences of hipsterdom on present day politics is damning. The cult of individuality and commitment to burnishing one���s quirkiness is exposed for what it is: depoliticization, consumerism, complicity. Hipsterdom is ���a lure, a diversion: it was a glaring instance in a mass movement of depoliticization whose very avowed scorn for politics made the bed for our fascist present.���

In the end, though, Pierrot offers a path forward���the possibility of breaking the cycle of colonization, appropriation, and theft. He brings a genuine spirit of hopefulness imbued with a generosity that cannot but feel a bit heartbreaking. No spoilers here (ok one: it���s not not capitalism), but Pierrot posits a way to take all of that hipster energy spent cool hunting and channel it into something meaningful. It involves another, better white man associated with Virginia: John Brown, whose memory and legacy Pierrot suggests is the one US American culture should be mining and appropriating.

As it turns out, Brown also had a sick beard, so maybe there is hope after all.

May 18, 2021

Silicon Valley in Africa

Last year, the Financial Times ran a piece titled, ���Are tech companies Africa���s new colonialists?��� But while the article focused at length on the issue of venture ownership on the continent, it did not address the underlying business models. This is important, because embedded within these modalities are the logics which lubricate the machinery.

Let���s consider the emergence of rent or lease to own business models. These models are considered an innovation on microfinance, where the customer is able to rent or lease a product (e.g. a motorbike) with a path to ownership. While these initiatives have the potential to expand access to products and services, they also can be damaging to the customers they purportedly serve while exploiting the complexity of the model for asymmetric benefits. As a white, Western person who has lived and worked on the African continent, I suggest that the growth of these rent/lease to own businesses has in part been fueled by their rearticulated relationship to the issue of ���original sin��� (as dubbed by political scientist Patrick Chabal). This issue, as Chabal puts it, refers to the prior (historical or existential) quandary of whether non-Africans (specifically American and European) can legitimately speak (or, by extension, work) on the continent given the twisted nature of their relationship to it. In answer to this question, these startups have provided a response that allows for Western guilt to be completely repackaged and harnessed.

We have seen a similar dynamic in manifestations of the ���(white) savior complex.��� Particularly prevalent in the world of small-scale NGOs, this phenomenon is now being more broadly co-opted by socially oriented ���startups,��� those who fold some normative good into their mission, whether that be access to clean energy or healthcare. Ultimately, these startups propose that to address social challenges, entrepreneurship provides the most ���dynamic��� route���what Ory Okollo has already labelled as the one dimensional ���fetishization��� of entrepreneurship.

The tech landscape in Africa is of course broad, ranging from older, more entrenched Western firms to the established tech giants of China (Alibaba & TenCent, for example) through to African-owned and led startups. However, this article focuses specifically on Western tech firms that have molded themselves on the Silicon Valley paradigm of the high-growth startup (whether that be through funding, the genesis of their founders, etc.) My argument is that this specific configuration of Western Silicon Valley inspired start-ups focusing on rent or lease to own business models have been the most effective in this rearticulation of ���original sin.���

There are no perfect metrics to quantify the presence or influence of these Western tech firms, but when Briter Bridges analyzed funding based on the startups��� place of incorporation or headquarters the top five countries receiving African start-up funding were: the US ($471.8 million); South Africa ($119.7 million); Mauritius ($110 million); the UK ($107.6 million) and Kenya ($77.1 million).

It���s not necessarily the case that all Westerners in this space see themselves as atoning for the aforementioned ���original sin.��� However, the ostensibly good purpose that has attracted them and their ���impact��� to the continent is not neutral and cannot be untangled from the power structures and ideologies that define what impact is necessary, or even possible. By engaging in the neoliberal paradigm of the startup itself, they are necessarily engaging in the causes of the problems they are purportedly there to solve.

The rent/lease to own model provides specific insight into the relationship between capital, time, and psyche as reconfigured in the redemptive logic of these technology companies. ���An object that is mortgaged,��� writes French cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, ���escapes us in time, and has in fact escaped us from the outset.��� Here, Baudrillard alerts us to not only the relationship between time and consumption (and its embedded labor), but also to something more subtle: the duality of anxiety as a modulating variable for both system and individual and the uneasy equilibrium they find themselves in.

This anxiety tells us that capitalism can no longer solely be understood in terms of capital and commodity alone, but must incorporate processes of financialization: the expansion (through credit) of the financial sector into new social, economic, and spatial spheres. In the context of rent or lease to own models, it is a form of asset financing, as the main collateral on the lease or loan is the asset which is being financed. These can occur as a response to the anxiety of becoming ���senile������as Egyptian Marxist economist Samir Amin puts it��� a state which leads to a greater dependence on finance (as capital shifts away from productive activities) and thus to ���rent.���

The growth of the rent and lease to own business models on the continent can be seen as a manifestation of this anxiety as it seeks to collateralize against ���untapped��� markets. Arguably the financialization of the poor has been occurring for some time across Africa, especially with the growth of microfinance. The problems of microfinance have become increasingly well-documented, with mixed evidence over its effectiveness, as well its potential psychological and social impact for those who fall behind on repayments and subsequently carry the burden and shame of debt.

It is worth noting here that the business model of rent-to-own does diverge from that of microfinance institutions, although some will sell through these institutions as intermediaries. Rent-to-own organizations do not generally charge interest at the same rate as MFIs, which is definitively a positive and when managed properly, has the potential to bring benefits. However, when operated with less integrity, even with lower interest rates, there can still be a number of negative implications for the customer. The asset is typically tied to repayment, so if there are issues with repayment, the asset (e.g., the cookstove) is often locked and eventually even repossessed. This can cause issues when the customer has already spent a large percentage of their savings on the deposit and may have less flexibility to find alternatives if they fall behind on their payments, as well as the potential social implications of having to have something repossessed. We are already seeing the technology expand into coercion: such as the ability of a lender of smartphones to lock the phone when repayment falls behind. So, in this form of asset financing, we are now seeing what the cultural theorist Byung-Chul Han has described as late capitalism���s morphing from a mole to a snake, removing limitations of time and space to a system which ���creates space through the course it steers.���

As social entrepreneurship and its rent-to-own models spread across Africa, the rearticulation of ���original sin��� is key. This is because it functions as the glue for an unholy alliance between debt (of the consumer renting or leasing) and infinity (the space to which the object is being mortgaged; because there is no guarantee of repayment). To understand how this apparatus provides the moral currency for redemption, Nietzche and Baudrillard provide some scaffolding.

Baudrillard argues that beneath the whirl of exchange is what cannot be escaped: the negative, absence, and ultimately death, which lubricates the circulation of both credit and debt. Nietzsche suggests that because God redeemed man���s debt by sacrificing his own son, the debt could never be repaid, as that had already been done by the creditor. Within this logic of endless circulation, man will bear his perpetual sin, and as such is the ���ruse of God.��� Baudrillard extends this further, writing that it is also the ruse of capital, which continually plunges the world into greater debt while simultaneously redeeming it. Thus the religious universalism of ���man��� is co-opted by capital and harnessed for its own needs.

It is within this framework that we must understand the proliferation of startups selling on credit and finance across Africa. While in Baudrillard���s conception capital simply mirrors the religious logic of debt-to-redemption to maintain its supremacy, here, more explicitly, the debt of sin is harnessed and repackaged within the modality of capital, allowing it to reorientate its gaze from the past to the future: the infinite. This is particularly important as it allows organizations and individuals to redeem themselves through participation in capital���s new logic���because they now exist in the future, set free by the expansionist logic of capital.

The mechanics here are important, specifically that the poor are turned into financial assets through the sale/consumption of products on credit/finance. Unfortunately, startups on the continent are often building projections about how many of their customers can actually afford to pay as they sell themselves (along with their customers) into the future with skewed projections. At this point, the company can already benefit, because in the process of financialization they now have a base, or number, which can be plugged into various calculations to project their future income, worth, etc., which can then be used as the basis for raising new capital or selling the business���this itself being the basis for asymmetry.

Some of their counterparts, such as investors in venture impact funds or private equity, may present themselves as ���patient capital.��� But they still often bring with them the ruthless commercial pressures of growth and can be seen as already being embedded in the mesh of hyper-capital exchange. In other words, both are in a flux of speculation. When joined together, this relationship forms what Baudrillard calls ���speculative disorder,��� where all internal reference has been eroded. This is a function of the same logic of the (re)cycling of debt: a mirage of exchange to obscure the nothingness below. The interface with other capital allows this to be extended���meaning the projections now exist in the infinite space of speculative disorder���all the more problematic when you assess the asymmetric distribution of benefits which plays out during acquisitions where Western founders receive the majority of the benefits. And while such acquisitions are relatively rare on the continent, we should only expect them to grow as more companies branch into this space.

Of course, Western tech companies will continue to grow on the continent, and can play a role in addressing key social challenges. However, in doing so they would do well to reflect on their impact in the broadest sense, and the integrity of their approaches to ensure more equitable and sustainable benefits.

May 17, 2021

Writing is a cultural weapon

For the people residing between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, this past weekend commemorated the 15th of May, 1948, when the state of Israel came into existence. For one half, it was an occasion to mark triumph, to remember the moment they supposedly returned home. For the other half, it was an occasion for despair and mourning, marking the moment they were expelled from home. As one side celebrated independence, and the other remembered the Nakba, the world continues to bear witness to how the condition for the continuation of a Jewish ethnostate remains Palestinian subjugation.

In the last two weeks illegal Israeli settlers, protected by Israeli state security forces, forcibly removed people in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah from homes they have lived in for generations. Israeli occupation forces, unprovoked, stormed Al Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem, detonating tear-gas, sound bombs, and firing rubber-coated steel bullets leaving over 200 Palestinians wounded on the last Friday of Ramadan. Now there is intensified bombing of civilians in Gaza by the Israeli military; at the time of publication, more than 192 Palestinians have been killed, including 58 children, while over 1200 were injured.

In the face of all this, Israel (emboldened by its backers, like the United States) asserts like a broken record that it ���has the right to defend itself.��� Notwithstanding the fact that even as far as the proximate causes of the current violence is concerned���Israel is the immediate aggressor���Israel has structurally been the aggressor since 1948 when in its creation at least 750,000 Palestinians (from a population of 1.9 million) were made refugees beyond the borders of the state. As the Jerusalem-based writer Nathan Thrall observes, ���In the seven decades of Israel���s existence, there have only been six months, in 1966-67, when it did not place members of one ethnic group under military government while it confiscated their land.��� Couple this fact with Paulo Freire���s trenchant point in Pedagogy of the Oppressed: ���With the establishment of a relationship of oppression, violence has already begun. Never in history has violence been initiated by the oppressed.���

That Israel ���has a right to exist��� as an apartheid state is an outrageous idea, and that��Western governments expect us to take it seriously, is offensive. Israelis, of course, have every right to live in peace and security and flourish, and so do Palestinians.�� It is the notion ��� rooted in a modern but anachronistic concept of the nation-state as Tony Judt once pointed out ��� that Israelis have a supremacist claim to dominate the territory, which makes the Zionist movement, not a homecoming project but a settler-colonial one that required the dispossession and displacement of the indigenous population. Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once noted soberly to an Israeli interviewer: ���You created our exile, we didn���t create your exile.���

In that interview, Darwish goes on to further say:

I want to remind you of a sensitive point. I���m not so sure that the most recent generations of Jews remember that they���re living in exile, be they in Europe or America. Does the concept of ���homeland��� live with you through all the generations? Do all Jews bear such longing? Yet every Palestinian remembers that he had a homeland and that he was exiled from it. Not every Jew remembers this, because two thousand years have passed. The Palestinian���for him, the homeland is not a memory, not some intellectual matter. Every Palestinian is a witness to the rupture ��� Homeland is a broad concept, but when we go to the homeland we���re searching for a specific tree, a specific stone, a window. These components are very intimate and are neither a flag nor an anthem. I long for the little things.

This week���s AIAC talk is devoted to Palestinian solidarity. For international spectators, the case for Palestinian liberation often exists in the heady space of argument, a realm of abstractness. And while there are the visceral images of horror and brutality we are exposed to on our TV screens, when the ceasefires are declared and the violence paused, it can cause us to forget that another violence still remains���in the little things. This is the violence of petty apartheid, a word South Africans used to describe how apartheid���s most debilitating effects, how it controlled the most intimate aspects of life, how it was a daily humiliation. This was exemplified by what happened in East Jerusalem, when Israeli security forces barricaded the Damascus gate esplanade (a popular gathering spot especially during Ramadan), or when those same forces desecrated Al-Aqsa���the point is to rob people of all their dignity in every way.

We want this episode to transport us to the realm of not simply understanding the injustice of apartheid, but of grappling with its totalizing brutality���and it is often the case, that literature, film and poetry can evoke images of places we���ve never been, can allow us to bear witness to feelings we���ve never experienced. Relating the importance of black art in relaying the black experience during apartheid, the South African poet Mafika Gwala declared in his seminal 1984 essay, ���Writing as a Cultural Weapon���: ��� When you face a truth and there is challenging need to express it, you can most emphatically capture it through poetry, because there is no way you can twist it about in a poem. You have to bring out the truth as it is, or people will see through your lines. It is also through poetry that you find, most soberly, that there has never been such a thing as pure language.���

This episode will feature South African writers reading the poetry and prose of Palestinian writers (with some hopefully joining us, subject to availability during these trying circumstances). South Africans know the despair and suffering of apartheid. But South Africans also know that apartheid can end. And so, as Palestinians continue to resist, we hope for this to serve as a small gesture of solidarity as they dream of freedom.

���A dream is a piece of the sky found in everyone,��� asserts Darwish. ���We can���t be boundlessly realistic or pragmatic. We are in need of the sky. To strike a balance between what is true and what is imaginary. The dream is the province of poetry.���

Stream the show on Tuesday at 18:00 in Harare, 20:00 in Gaza, and 12:00 in New York on��YouTube.

Last week, it was the 40th anniversary of Bob Marley���s passing so we devoted the episode to his life and complicated legacy, helped by Matthew J. Smith and Erin MacLeod. That episode is now available on our��YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

May 14, 2021

The specter of Mannetjies Roux

I am traveling with Ethiopian Airlines to Benin, and as is the case so many times, I���m the only woman in business class. Except for two fellow male black African travelers, the section is filled with morose-looking white men dressed in various peculiar shades of muddy dark beige or olive khaki. All that seems to be missing is a big rifle. Theirs is a sullen presence, all uniformly overweight with tree trunks for legs and bellies requiring the use of extender seat belts. And they are knocking back one drink after another, with little apparent enjoyment, just a seemingly dogged determination to get drunk as quickly as possible and pass out. I was seated next to one of them who was already slurring his words when he asked for his own seat belt extender, and he kept up a nervous rat-tat-tat tattoo of sound with his foot on the floor. Luckily, there was another seat available so I could get out of there. In any case, it looked as if he already sat on his own powder keg of impotent white male rage, and I didn���t want to get caught in the crossfire!

These white men have always held a weird fascination for me. They roam around airports and hotel bars all over Africa. I would see them sitting in hotel bars, nursing one beer after another as they spill all over their bar stools, always in the company of young black women who talk too loudly and flash long lean legs as they talk to each and ignore their drunken bar companion until it is time to leave. It���s always a transactional relationship. These many men that I���ve seen over the years roaming morosely, restlessly across Africa … What are they still searching for? The promise of their own Mannetjies Roux day that never came? That retired rugby player is so much a part of Afrikaner legend. He scored a triumphant try against the despised British Lions, which cemented his status as an Afrikaner hero, and of course, he is also known as someone who wasn���t against physical attacks on anti-apartheid demonstrators when he toured England with the Springbok rugby team.

Anyway, if you are brave enough to ask these white men on the plane, they will tell you, keeping it very vague, that they work in security. If you probe further, they will give names of companies like ���Security Solutions for Africa��� or some such. Or they will say they supervise construction. Or help to manage a mine somewhere in Congo. Or they lay pipelines. Or they are trying their hand at farming. They are not a likeable bunch, but then again, they are not trying to be liked. They seem caught in a time warp in this new Africa, where the old rules around race and power no longer work in their favor.�� Mostly resented and despised wherever they go, and called names like ���umlungu��� and ���mzungu��� or ���bwana��� … and never without irony, for to be white and male means power and privilege. They are not ready to let go of the dream of the past, and unwilling to accept the reality of the present. But for the most part, their whiteness still represents power and privilege.

In one of my previous diplomatic postings, I was having an idle conversation about the hectic local traffic with one of our white colleagues. He recalled that in his last posting in East Africa, the traffic was always continuously gridlocked, with a constant cacophony of hooting and no road signs to keep order. I asked him how he coped with that, and he answered with complete unselfconsciousness, ���Oh, it wasn���t a problem for me. I would just put my arm out the window and then everyone would give way.��� He seemed proud of this, the power of a white arm stretched out a car window and the traffic immediately parting as if he was some biblical white Moses parting a Black Sea. Imagine that. The supreme, absolute arrogance borne out of certainty in your ���place.��� Knowing that if you stick your arm out of your window that everyone will make way for you. How much of colonial pain and conquest and power and privilege sits in that action that allows you to lift up your arm, stick it out your car window in the thick of traffic, to signify ���make way.��� And for those giving way, the years of understanding what whiteness signifies, that even when whiteness doesn���t hold institutional power anymore, it still resonates so much in the present that cars and tuk-tuks and motorbikes just give way to you and allow you right of way. What constitutes that ���right of way��� now? So much to explore, so much to unpack. The power and privilege of one white arm able to change the direction of traffic to let you through. The way in which it was recounted as a casual little anecdote made my chest close up and left me breathless for a second. It made me think again about how privilege is used, again and again, even by those who profess to have moved beyond race, but who still dip back into it if it can ease some kind of ���social hardship��� or another.

And still these men continue to roam the continent and elsewhere so that they can cash in their power and privilege for more money and cheap sex. Some of them get so lost to themselves that they find their ���grave by the side of the road.����� I���ve come across some of these graves in another of my previous postings. It was a country that had become over the years somewhat of a sexual siren call for flocks of grey, middle-aged men, who left their families behind in Western countries to travel to its shores so that they could live a carefree life of transactional sexual hedonism with poor young women and men pushed into the sex industry.

How utterly sad. How banal. How tragic.

But still, back to those endless white men nursing their cold beers or brandies in hotels all over the continent, with a bevy of black beauties at their command for dollars or euros. What are they thinking about their past and their present? I think of them as an endless parade of itinerant, restless ���Mannetjies Roux������the so greatly admired character of the uncle who lost his farm after a drought somewhere in Africa, about whom Afrikaner musician Laurika Rauch sings:

My oom is oud en ek is skaars dertien

My oom drink koffie en my tannie tee

Ek vra oor die re��n en hy se, ja nee

En hy drink soet koffie met sy een oog toe

En hy praat weer oor die drie van Mannetjies Roux

O stuur ons net so ‘n bietjie re��n

My oom het ‘n tenk vol diesolien

En se��n my pa

En se��n my ma

En my oom op sy plaas in Afrika

Maar my oom het gesukkel op die plaas

Want die son was te warm en die re��n te skaars

En die man van die bank het net sy kop geskud

Want my oom, ja my oom was te diep in die skuld

[My uncle s old/and I���m barely 13/my uncle drink coffee and my aunty tea/I ask about the rain and he says yes,no/and he drinks sweet coffee with his one eye closed/and he talks again about the try of Mannetjies Roux

Oh send us just a little rain/my uncle have a tank full of gasoline/and bless my father/and bless my mother/and my uncle on his farm in Africa

But my uncle struggled on the farm/because the sun was too hot and the rain too little/and the man at the bank just shook his head no/because my uncle was too deep in debt]

I wonder if this uncle is one of those desolate, morose-looking men now sitting in bars from Accra to Nairobi to Dakar and elsewhere.

But for now, I���m about to land, and I���m excitedly peering out of the window and down on the sprawling urban landscape with its long coastal line … I already call it ���my Benin��� … and Chingchi is waiting … Bonjour, Benin!

���Groete aan Mannetjies Roux��� is a song of great pathos, but with very different meaning depending on how one related to then-apartheid South Africa���s destabilizing campaign in other African countries who were fighting for their own independence and whom the government suspected of supporting the resistance against its rule. Although the song was released long after 1994, I distinctly recall that we would change the words to reflect the role that the South African army played in some of our neighbouring countries like Namibia (colonized by South Africa as South West Africa), so we would sing, with some irony,

En se��n my pa

En se��n my ma

En se��n my Boetie wat veg in Suid-wes Afrika (of Angola, ens!)

(And bless my father

And bless my mother

And bless my brother fighting in South-west Africa)

May 13, 2021

Another essentializing moment?

Justice for Sam DuBose sign. Credit Hayden Schiff via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Justice for Sam DuBose sign. Credit Hayden Schiff via Flickr CC BY 2.0. In his introduction to the recently released volume of Stuart Hall���s writings on race and difference, historian Paul Gilroy argues strongly for the contemporary relevance of Hall���s thought. Yet, as social theorist Sindre Bangstad notes, in ���one particular respect,��� Gilroy ���places … Hall resolutely in the past.��� Specifically, Gilroy identifies the ���considerable hostility��� among contemporary anti-racists towards the ���open … notion of blackness��� as ���a political color accessible to all non-whites,��� a notion that figured centrally in Hall���s classic essays on the politics of difference in 1980s Britain. Bangstad is skeptical of Gilroy���s claim that this version of blackness as a kind of self-identification akin in many respects to class consciousness is ���now anachronistic.��� Instead, he suggests that Hall would react in an ���open��� and ���pragmatic��� manner to the ideas of contemporary anti-racists.

By contrast, I would argue that Gilroy is correct in his assessment; indeed, the passing (or, more optimistically, eclipse) of race as a political rather than ontological category highlights just how much the terrain of struggle has shifted since Hall produced his classic works on the subject. Yet something important has been lost in the bargain by which the racial categories that Hall so presciently revealed to be social, historical, and political have re-ossified into apparently inarguable natural forms. For at a time when, as American political scientist Jodi Dean suggests, ���those taken to share an identity are presumed to share a politics, as if the identity were obvious and the politics didn���t need to be built,��� we seem to have slipped into what Hall might have termed ���another essentializing moment.���

In his classic 1992 essay, ���What Is This ���Black��� in Black Popular Culture?,��� Hall criticized ���the essentializing moment��� he inhabited for naturalizing and de-historicizing difference, for ���mistaking what is historical and cultural for what is natural, biological, and genetic.��� Moreover, he suggested that such essentialism was incompatible with anti-racism: ���the moment the signifier ���black��� is torn from its historical, cultural and political embedding and lodged in a biologically constituted racial category,��� he wrote,�����we valorize, by inversion, the very ground of the racism we are trying to deconstruct.��� The end point of such racial absolutism, he warned, is unwarranted faith in the absurd notion that ���we can translate from nature to politics using a racial category to warrant the politics of a cultural text and as a line against which to measure deviation.��� Ironically, the kind of naturalization that Hall located in Thatcherite racism has taken root at the heart of anti-racist rhetoric itself.

British sociologist Claire Alexander describes ���an important shift during the 1990s [in the UK] from ���political blackness��� to ethnically defined identities, such as black British or British Asian,��� or, more recently and somewhat controversially, BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic).�� According to Alexander, the dynamics of political blackness were once very much like those of class formation. In the 1970s and 1980s, she says, ���young people of color identified as black and campaigned together to fight racial discrimination,��� adding that ���at the heart of political blackness was a shared feeling of being unwanted.��� Yet from the perspective of the present in both the US and the UK, the idea that blackness could denote anything other than African ancestry seems absurd. Alexander, ���who describes herself as an Asian woman in her 50s, says, ���I still use black, but I realize you can���t really get away with that because you look at young people and you describe yourself as black, they will look at you like you���re deranged.������

As logical as it appears to be, the shift away from black as a political identity in which shared politics based on coalition building trumped ancestry to more contemporary notions of natural blackness located in individual and essential bodies was neither necessary nor coincidental. Alexander argues that the British government ������sponsored a specific version of multiculturalism, which was focused on ethnic identities,���… [as] a method to undermine��strong forms of resistance.��� Moreover, she adds, ���the move away from political blackness and toward ethnic identities broke down key alliances between communities … eventually [leading] to a disempowered and, in some ways, a depoliticized anti-racist movement.��� We should not lose sight of what has been lost in the recasting of black as a natural category���the ability to conceptualize a community of struggle that does not ���valorize, by inversion, the very ground of the racism we are trying to deconstruct.���

Ultimately, Hall���s response to contemporary anti-racist racial absolutism might be less to welcome it pragmatically than to see it as the return of the innocent black subject���insofar as that category is seen as pre-given and naturally existing, a feature of ontology rather than the subject of political struggle. We, in turn, would do well to reject the kind of essentialisms Hall criticized so cogently, even���indeed, especially���in service of anti-racism. Instead, we must push for a return of the sort of politics of struggle ���without guarantees��� which Hall advocated in his classic works on race. It is high time that we heed Hall���s reminder that identities are never obvious and that the politics of struggle always need to be built. In this regard, Hall���s work on race as a political category, even in its anachronism, has never been more timely.

May 12, 2021

Managing the city like the military

A poster erected at one of the main entry points to Mukuru kwa Reuben. Source: author.

A poster erected at one of the main entry points to Mukuru kwa Reuben. Source: author. Under the 2010 Kenyan Constitution, functions and powers are shared between the national government and devolved units (county governments). In 2013, Nairobi elected its first governor under this new system of governance: Evans Kidero, who describes himself as a ���slum-born��� former businessman. He vowed to improve service provision in the city within his first 100 days. Not much happened during his tenure, and, in fact, social exclusion was further entrenched. In 2017, Kidero lost to Mike Mbuvi Sonko, a self-confessed jailbird with a penchant for juvenile drama. Sonko devised a simple hierarchical order in which service provision to the residents of the city punitively came as an afterthought, secondary to his habitual revels. He would later be impeached by the Nairobi County Assembly in December 2020. By this point, Sonko had already fostered an ecology of inefficiency, making it easier for the national government to usurp the constitutional powers of the county government.

On February 25, 2020, prior to his impeachment, the governor signed an agreement to hand over certain functions of the county government to the national government. The argument advanced to justify this move was that service delivery in the county had ground to a halt and that intervention by the national government would ensure that residents received services efficiently. A new entity, the Nairobi Metropolitan Service (NMS), was created and a serving military officer handpicked by the president as its director general.

The establishment of the NMS must be viewed as counteraction by a national government that felt emasculated by devolved governance. NMS brings with its establishment an authoritarian spatial order premised on the managerial delivery of results. We are already witnessing the sidelining of democratic institutions like the county government and the county assembly, their places taken over by undemocratic and militarized institutions. In the usual style of an undemocratic institution, the NMS continues to mobilize its capacity for opacity, which is ubiquitous in military governance. It has extensively partaken in the violent erasure of the collective agency of Nairobi���s inhabitants. This is evident from how the views of the city���s inhabitants are never sought or considered whenever the NMS initiates and implements public projects. Similarly, the emasculation of the Nairobi County Government now appears to be complete, as it has adopted a subordinate posture to the NMS.

It appears that for the NMS, public participation in spatial governance processes is a form of odious politics that stands in the way of the ���missing discipline��� it desires to reign supreme. It has conjured an image undoubtedly intended to evoke the feeling of orderliness which is supposedly portended by its arrival in Nairobi. With this image, the NMS strives to impress upon Nairobians and visitors alike the idea of an emergent urban imaginary organized around militarism and a lack of accountability. Its director general, Major General Mohamed Badi, has on numerous occasions scoffed at calls for accountability, quipping that he is only answerable to the president. The General, as he is known, often donning military fatigues, has been a frequent visitor to many of the city���s neighborhoods, where he inspects ongoing projects that are being carried out by the NMS. According to him, ���managing the city is just like managing the military���; serving in the military, he claims, places him at an advantage when dealing with the city���s numerous challenges. He asserts that this is particularly true for the issue of cartels in the city, since, he says, ���dealing with enemies is part of my training.��� This rhetoric is alienating and has as its goal the reinvention of passivity in spatial governance.

By allowing for the fetishization of managerial logics in public policy spaces, we are unwittingly courting dictatorship and facilitating a power grab by an unelected elite. It is therefore critical that we examine the spatial order that the NMS introduces, expose its violence, and grapple with the implications of its entrenchment. From the way it is structured, the NMS is an anti-politics machine designed to subvert the logics of participatory governance which were beginning to take root in the city with the establishment of devolution. Its romanticization of ���efficiency,��� a moniker for lack of accountability, obscures its ideological scaffolding as an undemocratic project and masks its repressive character. We must therefore lift the veil on the NMS and reveal its true character as a sophisticated apparatus of political deception oriented at the systematic dismantling of democratic norms and practices. This requires maintaining a calculated circumspection when consuming its generosity, as its liminal distributive acts will most certainly fail to materially alter the living conditions of the inhabitants of Nairobi, especially those living in informal settlements. Ultimately, the struggle for space in the city must be approached as a wider radical political project that seeks to challenge the asymmetries of power and undo structures of oppression and marginality.

May 11, 2021

Don���t be fooled by a catchy tune

Still from ���Geen Wedstrijd��� by Akwasi, Bizzey.

Still from ���Geen Wedstrijd��� by Akwasi, Bizzey. The US Black Lives Matter movement is not showing any signs of slowing down. Recent weeks saw a new peak in demonstrations during the court case against Derek Chauvin, the policeman charged (and since convicted) with murdering George Floyd, as well as new instances of police violence directed at African Americans. High-profile African American artists have also been continuing their pledges of support for the movement: H.E.R. released her politically charged new song ���Fight For You,��� while CHIKA posted a series of heartfelt freestyle raps to Twitter and Instagram to address systemic racism.

This new musical material adds to an already impressive range of songs released in light of the Black Lives Matter movement. As many commentators have noted, releases such as Anderson�� .Paak���s ���Lockdown,��� Beyonc�����s ���Black Is King��� and the cover of ���For What It���s Worth,��� released by the���admittedly, somewhat peculiar���duo of Stephen Stills and Billy Porter, have attempted to capture the widespread sentiments of anger and hope in the form of songs. On the other side of the Atlantic, artists have also been raising their voices; the Dutch variant of the Black Lives Matter movement was, for instance, applauded and covered in new material released by hip hop acts such as Akwasi, Bizzey and the #Adembenemend (���#Breathtaking���) song project.

Although the active production of these new protest songs has caught the attention of many newspapers and media, the soundtrack to Black Lives Matter not only consists of new material; through the active re-use of legendary protest tracks such as Nina Simone���s ���Mississippi Goddam,��� Billie Holiday���s ���Strange Fruit,��� Public Enemy���s ���Fight the Power��� and N.W.A.���s ���Fuck tha Police,��� BLM has been emphasizing the past as much as the present. This is not entirely surprising; Ann Rigney, literary scholar and leader of the Remembering Activism research project, has pointed out that struggles for a better future often go hand-in-hand with memorializing past struggles.

The recent reappearance of Simone���s ���Mississippi Goddam” in the form of online covers, live performances, and digital quotations is a great example of BLM���s tendency to engage with the past as well as the here-and-now. ���Mississippi Goddam��� is closely tied to specific historical episodes in the struggle for Black emancipation; Simone wrote the song during the 1960s in response to racist lynchings carried out in Mississippi and Alabama. The sarcastic show tune quickly became an anthem of the civil rights movement���but it also took a heavy personal toll on Simone. Igniting a backlash in Southern states, it led to a boycott of Simone���s work by the US music industry. The singer���s commercial success took a considerable blow, after which she retreated, disillusioned, to France.

Some 50 years later, the song resonated with protesters across the Atlantic. It was sung, played, and quoted during demonstrations and videos that addressed systemic racism���and crowds in London and Rotterdam seemed to feel as much for the song���s message as protesters in Minneapolis. Strikingly, Simone���s anthem was often performed in an unaltered form; aside from a few localized variants such as ���Minnesota Goddam��� and ���Roffa (a slang term for Rotterdam) Goddam,��� most demonstrations played and performed the song with Simone���s original lyrics.

This has everything to do with the implications of singing a classic protest song such as ���Mississippi Goddam��� at a modern day demonstration. The song reminds listeners of a long and intense history of struggle, and even after all these years, the song seems to say in 2020, the violence goes on. Singing Simone���s rousing song at a protest in Amsterdam or Paris not only places current-day events in a long history of emancipation, but also links the local struggles of these cities to a history of oppression and resistance on the other side of the Atlantic.

There are also other ways in which protest music has used the past to address the present. The Dutch hip hop project #Adembenemend, for example, addresses the daily impact of systemic racism by shedding a new and subversive light on the past. #Adembenemend���which literally translates to #Breathtaking, an allusion to George Floyd���s last words���is an online song chain instigated by Dutch rapper Manu, record label Top Notch, and Amsterdam institute The Black Archives. It asks artists to detail their encounters with racism over a freely downloadable instrumental track. The many versions of the song bring together a vast range of histories and experiences; Manu���s version of the track, for instance, covers the day-to-day racism felt by his children, the success of ethno-nationalist politicians in both Europe and America, the American civil rights movement, the fight for Indonesian independence, Dutch complicity in the transatlantic slave trade, and Zwarte Piet, a Dutch folklore blackface character that has come under intense criticism from anti-Black racism movements in recent years. By bringing together this dazzling repertoire of subjects, Manu produces a new story about the past���one that showcases the widespread and multi-faceted influence of systemic racism.

Whereas covering Simone���s anthem legitimizes contemporary protests by placing them in existing and accepted stories about the past (specifically, the story of the civil rights movement), #Adembenemend critically breaks down the dominant ways in which the past is represented. By linking the wealth of the Dutch royal family to the oppression and exploitation of the former Dutch Indies and the South African apartheid system, Manu brings together stories that are conveniently separated in the canonical outlook on Dutch history as presented in schools and museums. Thus, Manu bridges insights into the vast, systemic nature of racism and the pain of lived experience.

According to Rigney, remembrance is a dynamic thing. Memories of the past are constantly reused and reworked to make us understand our place in the present a little better, and to allow us to envision the future in a hopeful way. ���Mississippi Goddam��� and #Adembenemend show that remembering the past plays an enormous role in contemporary attempts to tackle societal wrongs. Don���t be fooled by a catchy tune���before you know it, it can kick down the doors of history and change your outlook on the past, the present, and your geographical underpinnings. And sometimes that can definitely be a good thing.

Excavating Kazi Mataani

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers