Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 125

June 16, 2021

Diagnostic dilemmas

Abbasiyya, Egypt's oldest mental health hospital (Photo: Ana Vinea, Supplied). This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

Abbasiyya, Egypt's oldest mental health hospital (Photo: Ana Vinea, Supplied). This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford). It was a puzzle I repeatedly encountered during my field research on revivalist Islamic healing in Cairo. It starts with a young person who begins to experience disturbing physical, psychological, or behavioral symptoms, especially in religious contexts: convulsions, hallucinations, extreme emotions, among others. How are such symptoms to be diagnosed? Echoing Ludwig Wittgenstein���s famous duck-rabbit image that can alternatively be seen as either a duck or a rabbit, the question has two answers in Egypt: a mental disorder or possession by jinn���invisible spirits mentioned in the Qur���an that historically have been at the center of curative practices.

This diagnostic quandary implicates primarily the patients and families personally affected and the psychiatrists and Islamic healers called to treat these afflictions. Yet, in the past decades, the jinn possession/mental disorder pair has become the focus of heated public debates at the crossway of religious and medical domains. On television screens, online, or on the pages of various publications, revivalist healers, known as Qur���anic healers and mental health professionals, alongside journalists, religious scholars, and members of the public have clashed over this diagnostic dilemma, keeping the two categories simultaneously conjoined and apart in a dichotomous grip.

Participants in these mass-mediated polemics have approached the impasse from the angle of the reality of jinn possession, each side invoking conflicting exegeses of the Qur���an and hadith and diverging over the precedence of religious versus scientific evidence. My interviews show that psychiatrists, joined by some religious scholars and secular intellectuals, assert that jinn possession is doubly unsupported, by science and religion, and, hence, ignorant twice over. Recognizing mental disorders and their psychiatric treatments, Qur���anic healers have nevertheless maintained that the religious texts that prove possession trump current medical knowledge.

What is at stake in these debates are conflicting ideas about what afflictions exist in the world and what are the remedies to address them. Furthermore, these arguments project questions of maladies and suffering onto larger socio-political discourses concerning the relationship of science and religion, the state of society, and modern citizenship.

Certainly, such tensions between medical and occult etiologies are not restricted to Egypt or the present. From miraculous healing at Lourdes in Third Republic France to hearing voices in the contemporary US, they speak about broader authoritative challenges posed by biomedicine to other understandings of affliction. Still, questions remain���why this pair and why now?

If jinn possession has been disputed throughout Islamic history and occasionally linked to psychological disturbances as understood at the time, in its current form the jinn possession/mental disorder pair goes back to the 19th century. The advent of Western-inspired medicine and psychiatry led to a familiar story throughout the African continent���the reshaping of the therapeutic landscape into the dichotomous domains of modern medicine and a heterogenous new category of ���traditional medicine.��� In this context, medical professionals and reformist Muslim scholars targeted practices around the jinn as the paradigm of all that had to pass for Egypt to modernize. Reframed as superstitious, but not explicitly outlawed or regulated, jinn therapies survived, and sometimes flourished, under the radar of the modern state.

In the second half of the 20th century, several transformations have intersected to push the jinn possession/mental disorder binary into the limelight. Against the background of an Islamic revival, beginning in the 1980s and 1990s a Salafi-oriented therapy of jinn exorcism gradually coalesced and gained popularity in Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries. These Qur���anic healers claim that theirs is the only ���orthodox��� treatment of possession that systematizes the existing curative repertoire eliminating all that is religiously unpermitted. Moreover, these practitioners have engaged in a multifaceted dialogue with psychiatry and biomedicine, both challenging some of their premises (the rejection of the invisible) and redeploying concepts and practices derived from these disciplines, such as symptoms and experimentation.

For instance, Qur���anic healers have used the notion of symptoms to devise diagnostic checklists for each possession type and subtype, while infusing it with religious meanings through emphasizing symptoms��� religious content and the context of their occurrence. Creatively embracing tools of mass dissemination, especially television with the satellite revolution of the 2000s, Qur���anic healers have pushed jinn possession into the public eye, stirring anxieties across the religious/secular spectrum.

Changes in the psychiatric domain have also contributed to the prominence of the jinn possession/mental disorders duo. Such is the turn of some mental health professionals towards an Islamically-attuned practice, the neoliberal erosion of the public health system that has left psychiatric services wanting, as well as the spread of psychiatric languages among the population aided by anti-stigma campaigns and a noticeable presence of psychiatrists on satellite television. The increasing visibility of Qur���anic healing has intersected with psychiatry���s growing foothold in public awareness to create a fertile ground for deliberations over notions of affliction, care, and expertise.

The prominent debates around the jinn possession/mental disorders pair reveal a vibrant therapeutic landscape that cannot be frozen in a secular/religious divide but remains haunted and partially shaped by it. The resistance of psychiatrists to Qur���anic healers��� attempts to impinge on their domain of expertise places Egypt at odds with the recently renewed calls of the WHO to integrate traditional medicine into health care systems. Instead of the partnerships forged in some African countries, in Egypt there is an official attempt to keep such therapies at an arm���s length, if not to eradicate them completely���a testament of how they have been framed as thwarting progress since the 19th century. The only attempts of rapprochement have come, so far, from the ranks of Qur���anic healers. Even if in public debates these practitioners have vehemently defended jinn possession to the effect of reinforcing the dichotomy with mental disorders, in their therapeutic practice they have adopted a stance of ontological multiplicity that tangles such divides. Recognizing the validity of both categories, as well as their many shared symptoms, Qur���anic healers have devised ways of telling jinn possession and mental disorders apart, with the hope that one day they would work side by side with psychiatrists.

Such fluctuations between relative flexibility and rigidity reflect the limitations of the WHO���s push toward integration, which skims over the complex historical and contextual factors that sometimes work against official cooperation. Yet, this apparent failure has its productive facets. The tensions between psychiatry and Qur���anic healing account for the vitality of contemporary debates around affliction and healing. No surprise then that these precise tensions have been mobilized by a Qur���anic healer who has conceptualized a new disease category���wahm, the affliction of experiencing real possession symptoms while being unconsciously, but falsely, convinced one is possessed. This novel malady has emerged as a third way that tries to overcome the jinn possession/mental disorder binary while keeping the reality of jinn possession intact, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the ailments that plague Egyptians.

June 15, 2021

Fractured dreams: The life of a Libyan exile

A still from the film.

A still from the film. ���The dream of Libya has always been with me.���

���You were my revolution.���

Filmmaker Khalid Shamis sits at a table drinking coffee with his mother Shamela in their family home in Croydon, South London. Shamis asks his mother what she knew of his father���s work as a leading member of the opposition to Libya���s Muammar Gaddafi in exile: was he an arms dealer? A terrorist? A freedom fighter? She shakes her head, avoids the questions, and with a smile insists, ���you were my revolution.���

The motifs of revolution, dreams, secret lives, and of exile’s longing, play throughout Shamis���s second feature film, The Colonel���s Stray Dogs (2021). Shamis���s father, Ashur Shamis, was one of Gaddafi���s ���stray dogs:��� Libyans in exile who coordinated opposition to the regime under threat of ���physical liquidation.��� Gaddafi occupies a contested space in the histories of postcolonial Africa. While some remember his revolutionary pan-Africanism, support of anticolonial and dissident movements, and uncompromising antagonism towards neocolonial relations with the West, others focus on his authoritarianism, corruption, and violent repression.

Gaddafi targeted his opponents at home and abroad. After an attempted coup in 1983, Gaddafi established new prison complexes, instituted televised public hangings, and increased attacks abroad through bombings and traveling death squads. But Shamis is not interested in litigating Gadaffi���s legacy, though the dangers and stakes are clear; his story is the story of his father and the opposition movement he led from exile that kept him from his family. For Ashur Shamis, the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL) was creating an army for the liberation of Libya based on a ���nationalist Islamist agenda������a democratic society based on freedom of expression, progressive values, and religious plurality. Over 40 years, the revolution they envisioned was delayed and deferred, evolving from armed military effort into a media savvy campaign. When the revolution finally came in 2011, spearheaded by a new generation from within Libya, excitement and relief soon turned to exhaustion and despondency.

Asher Shamis and his son, Khalid.

Asher Shamis and his son, Khalid.If you follow African cinema, then you have most likely seen the work of Khalid Shamis, even if you don���t realize it. From his home in Cape Town, Shamis has served as editor on some of the most memorable and exciting films from the continent in the past decade, particularly from first-time filmmakers and those pushing the boundaries of the documentary form. I myself only began to see this connection when I realized that a series of African documentary films I had curated alongside acclaimed documentary filmmaker Francois Verster back in 2017 all shared the same editor���Shamis. His filmography brings to mind the seldom acknowledged ���auteur-editor.��� Without lessening the achievements of these remarkable and talented filmmakers, Khalid���s editorial mark can be seen throughout this body of work. Shamis���s collaborations on films including Hajooj Kuka���s Beats of the Antonov, Mpumi Mcata���s Black President, and Perivi Katjavivi���s The Unseen, among many others, reflect the critical self-reflexivity, blend of the political and the intimate, and formal experimentation that characterize a new generation of African filmmaking. Echoing his mother���s declaration, perhaps film is their revolution.

This political and personal aesthetic translates into Shamis���s own directorial work. His first film, Imam and I (2011), focused on the killing of Imam Abdullah Haroon, Shamis���s maternal grandfather, by the apartheid state. In this film, Shamis set out to reconnect to his mother���s side of the family and the Muslim Cape Malay community in South Africa. Through still photographs, interviews, and animation, Shamis tells the story of a liberal, politically active Muslim leader whose role in anti-apartheid activism and murder by apartheid police were denied for years.

In Stray Dogs, Shamis reconstructs not only an ���alternative history of modern Libya,��� but also an intimate portrait of a family in exile. Shamis intersperses the political history of a nation with family home videos captured miles away, framing the story through the memories of children, absences, and traces of the past. We see the father as he may have appeared to his family at the time, obscured and in silhouette on national television to protect his identity. We hear voices from the past on taped messages, fleeting moments of connection and longing. We watch Shamis touch the archives of a revolutionary, neatly packed in an old suitcase: multiple passports, security files, the NFSL���s magazine ���The Exiles��� and catalogues of weapons. History is shown, not told, through archival footage of social life in colonial Tripoli to the rise of the Gaddafi regime in 1969 and through the decades of struggle leading up to the Arab Spring. History has a way of making the inconceivable seem inevitable, but here, the inevitable is painfully ever-present and deferred over decades of struggle, sacrifice, and loss.

Shamis plays with light and shade to bring this shadowy history into focus. He reflexively inserts himself into the frame: popping in to check on the camera placement, tenderly adjusting his father���s microphone, and engaging his parents directly in conversations���at times ambivalent and tense, at others warmly affecting���about a part of their family history that remains unspoken. His father recalls how he instructed his son not to say he was Libyan, a doubled exile from place and self. These multiple exiles���geographical, political, and personal���fracture the dreams both father and son hold for Libya. Yet, from the opening credits to the final scene, family abides.

What happened to Ethiopia?

An 18-year-old survivor of gender-based violence sits for a portrait in Mekelle, on April 15, 2021, UNICEF (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

An 18-year-old survivor of gender-based violence sits for a portrait in Mekelle, on April 15, 2021, UNICEF (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) The recent goings-on in Ethiopia, particularly those of the last few months, have left many puzzled as to what exactly happened to the Ethiopia of 2018���an Ethiopia that promised major political transformations and even took a handful of steps to that effect. Both the ongoing displacement and killings of minorities in regions such as Oromia, Amhara, and Beneshangul-Gumuz and the ongoing war in Tigray���labeled by the federal government as enforcing law and order���are disturbing. Toward the end of 2020, the federal government started waging what it startlingly called a ���law enforcement operation��� in the Tigray region, branding the Tigray People���s Liberation Front (TPLF), the leading partner in the ruling Ethiopian People���s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) between 1988 and 2018, as ���a criminal organization and vowing to destroy it.��� From media coverage of the events, we have learned that some veterans of TPLF were caught and brought to court while others were killed. The hunt and its accompanying promise to bring the perpetrators to justice continues today; both the war and the legal procedures of those who have been caught are still ongoing at the writing of this post. The humanitarian crisis and the danger of famine in Tigray have become alarming to the international community, while the Ethiopian government seems to turn a deaf ear to humanitarian pleas and pressure. One wonders where we got it wrong while actually trying to right the sociopolitical ills that the country has inherited from a troubled federal experiment and authoritarian rule since 1991, and a violent imperial history that preceded it.

If we take a closer look at Ethiopia���s political history, particularly in its moments of transition, a familiar pattern of relying on the criminal justice system to solve political problems can easily be detected. For instance, in November 1974, upon seizing power, the Derg (then provisional military government) ordered the killing of 60 high-ranking officials who served in the monarchy. They justified this action by labeling the individuals as criminals as attested to by a statement from the provisional military council. ���The executions,��� the council said, ���were a political decision taken to mete out justice to those officials of the previous government who had thrived on corruption, maladministration and a “divide and rule” policy.��� The Derg also decreed that the rest of the detainees would be tried in a military tribunal. A new government, led by the TPLF/EPRDF, came to power after ousting the Derg in 1991. Again, the regime resorted to the language of law. The first step the EPRDF took was to hunt the perpetrators and bring them to court. These events, which journalist John Ryle described as ���the first large-scale human rights trial of recent times,��� unfolded on a grand scale: the entire former leadership of the country was under indictment for genocide and crimes against humanity. On both the discursive and practical levels, there is continuity between these three events. The criminalization of political problems and the attempt to solve them through the court system is a consistent trait of these moments of transition. All three mobilize the law; with a particular�� commitment to preserving a preexisting law. They believe in the courtroom���which, ironically, they control���to deliver justice. By this account, justice for victims partly depends on the removal of those who are now defined as perpetrators from the political realm, because they are reduced to being criminals, not political actors with constituencies. Only the victors are legitimate political actors; they claim to mete out�� justice and are thereby absolved of any responsibility for partaking in the violence. All three regimes in post-imperial Ethiopia, sideline the main issue���that is, the unresolved political problems���while relying on the seeming universality and neutrality of the law.

Resorting to the criminal justice system instead of seeking political solutions through the intricacies of the political process justifies further violent actions in the interest of maintaining law and order. As a result, the political goes unscrutinized and the victors simply operate within the existing structure instead of introducing more profound change. This simply shows that���as Mahmood Mamdani cautions in his new book, Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities���a ���Nuremberg Trial��� inspired approach to solving politically driven violence is inadequate. The courtroom in fact reinforces the vicious cycle of violence by dichotomizing political communities as either victims or perpetrators, thereby defining new enemies. Most of the sociopolitical and economic problems that necessitated the change, such as the quest for democracy, equality, freedom, respect of human rights, and economic development, remain largely unaddressed. Unless Ethiopia is willing to give a new way of resolving political differences a chance, the vicious cycle of violence will continue unabated. As Mamdani suggests, there has to be room and preparedness to change rules and to be open to new political orders. Relying on the courtroom to solve political problems only serves the interests of those in power, and helps them maintain their position by creating enemies around which they can galvanize popular support. For instance, TPLF has now become the new criminal group; it makes perfect sense, then, for the government and its supporters to withdraw protection from civilians in Tigray and elsewhere who have been victimized in the name of restoring law and order. Collateral damage is the language used to explain atrocities on civilians. Conducting performative politics such as elections elsewhere in the country while framing the conflict in Tigray as a “law and order” issue will not address the deep seated problems Ethiopia is confronted with.

June 14, 2021

Kwame Nkrumah���s Encounter with Karl Marx

Photo: Guido Sohne, via Flickr CC.

Photo: Guido Sohne, via Flickr CC. In his seminal work Black Marxism, Black American sociologist Cedric Robinson argues that African decolonization movements were born out of a separate radical tradition which came into contact with the European Marxist tradition. When we look at what Robinson calls the epistemological substratum of each tradition, however, we can see not only the points of fracture���which are Robinson���s focus���but also the intimate points of contact and creative reworking. They are not necessarily non-overlapping magisteria, as I argued in a recent edited collection on Marxism and Decolonization. I am interested in this encounter between African decolonial intellectuals and Marxism in the twentieth century.

I begin with Kwame Nkrumah���particularly how Karl Marx was appropriated, incorporated, and threaded through his traveling theory. It is insightful to think of Nkrumah���s thinking as moving through multiple onto-epistemological worlds within and beyond both Africa and Euro-North America. He was adapting to different political contexts; appropriating, engaging with, creating, co-constituting, inspiring and being exposed to a variety of knowledges and critical perspectives; and bringing each of these directly to bear on the questions of decolonization and neocolonialism in Ghana and the world.��

This is reflected throughout Nkrumah���s life. His early upbringing occurred among Roman Catholic missions, and in 1930, he attended Prince of Wales College at Achimota, as did many of his generation. He was first shaped by his Akan heritage and early education in Ghana by West African nationalists Nnamdi Azikiwe, from Nigeria, and Dr. Kwagyir Aggrey, a fellow Ghanaian, both of whom introduced him to W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. He attended secondary school in the United Kingdom and the United States and was an active member of a Leninist reading group. His politics developed within the milieu of organizing conferences for the West African Students Union, spending summers with Harlem activists while attending the University of Pennsylvania, and debating the works of Marcus Garvey, George Padmore, Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Working in the colonial administration and then towards independence, Nkrumah also had a profound interest in the economics of Pan-Africanism and sought advisors from the diaspora, Eastern Europe, and the United States.��

Where is the line that neatly separates Nkrumah from these entanglements? There is none.

It is within this context that Nkrumah���s written works and speeches reveal a selective encounter and appropriation of tools���in this case from Marxist thought���that were translated through Nkrumah���s traveling theory. Consciencism, for example, is Nkrumah���s attempt to rework historical materialism to account for African thought. He was trying to provide an Afrocentric ontology of non-atheistic materialism that would strategically allow for decolonization and the unification of Africa against neocolonialism. Pragmatically, this ideology was Nkrumah���s way to respond to the limitations of the Eurocentric focus of standpoint Marxism by reorienting historical materialism through his reading of Akan cosmology, quantum physics, and political economy at the historical conjuncture of African liberation and decolonization.��

Neocolonialism, the uses of political economy, and the analytical categories of class employed by Nkrumah also provide a relevant example to think about the intimacies between Nkrumah and Marxism. Think about Lenin���s claim about imperialism���that it was the highest stage of capitalism���and Nkrumah���s reworking of this claim, which identifies neocolonialism as the highest stage of capitalism. This is not a minor move; the changing of a word and the development of a concept open up new possibilities for understanding the present and working towards solutions.��

In many ways, Marx was also a traveling theorist, moving through the post-Enlightenment and post-German idealist philosophy that saw non-Europeans as outside of the World Spirit, the progressive linear movement of history and human development. But Marx is also a product of the creativity of living labor���what he calls the ���form-giving fire������born out of the specific sociohistorical, cultural, and onto-epistemological conditions of his experiences in Europe and the coloniality of knowledge production. Yet Marx���s works spoke to and contributed to the development of Nkrumah���s thought and action.��

The experience and creativities of Nkrumah and his encounter with Marxism demand that we continue to confront the big questions of decolonization and imperialism as manifested in a neocolonial racialized global political economy. They also demand that we try to think and act a way out of them.

The way we tell stories

Haitian director Raoul Peck���s four-part HBO film series Exterminate All the Brutes starts with a powerful premise. The series promises to situate the history of white supremacy squarely within the concepts of civilization, colonization, and extermination that provided the ideological and material backbone for the construction of whiteness. Drawing from a statement made by his friend, the author Sven Lindqvist, Peck assures the viewers that we already know this history, insisting that ���it is not knowledge we lack … what is missing is the courage to understand what we know.��� Unfortunately, rather than giving the audience the courage to understand the history of colonialism, Peck instead centers white men as the makers of history in a way that re-inscribes notions of white superiority. The decontextualized photographs, illustrations, and reenactments that fill the series further reduce the victims of colonization to the role of passive spectators in history. The painful irony is that in his attempts to name and portray the violence of colonialism, Peck ends up perpetuating that violence himself.

Peck presents the series in the style of a personal essay, detailing his understanding of the history he narrates. Yet for a series that is intended to challenge white supremacy, Peck curiously centers a white male archetype, played by Josh Harnett, as the protagonist in the story. Episode one showcases a dramatization of an 1836 battle in which a Native American woman from the Seminole nation challenged the United States government���s efforts to take her land and enslave her black friends. In the ensuing scenes, Peck���s white male archetype, who appears in the first episode as a military general, shoots the Seminole woman point-blank in the head. A few frames later, the general grabs her lifeless body from among the fire-charred black and Seminole bodies scattered on the battlefield and scalps her, holding her severed flesh and hair to the camera. It is not clear what function these gruesome scenes serve beyond their shock factor. In this representation of US colonialism, Peck casts the Seminole woman and her black comrades as no match for the awesome power of the white man, who emerges from the battle triumphant, unscathed by the easy defeat.

Peck���s depiction of indigenous communities easily succumbing to white men���s violence is repeated again and again throughout the series. In a dramatization of events in colonial Congo, the same white male archetype appears again, played still by Harnett, and proceeds to shoot a Congolese man in the head for not providing him with enough rubber. Referencing the atrocities Belgian colonizers committed to satiate King Leopold���s greed, the white man orders a young Congolese man to cut off the dead man���s hands while a mass of undifferentiated Congolese stand in the background of the frame, acting out their assigned role as agency-less victims in the history the white man enacts.

There is certainly an argument to be made for centering white men in the histories of violence that accompanied colonization and a host of other crimes against humanity. The historical record is full of the stories that the series dramatizes. Perhaps that is why many reviews of this series have been so generous. People may just appreciate the fact that these crimes have been given cinematic representation. But by depicting indigenous communities as completely helpless in the face of white men���s power, Peck reinforces the idea that white men are the only historical actors with any agency to speak of. Moreover, Peck casts white violence as so powerful that any attempts to resist it will result in death. As a viewer, these scenes were so horrifying that I wanted to stop thinking about this history altogether. And that is the danger. The series inundates audiences with images that are so overwhelming that it forecloses the possibility of imagining a world without white supremacist violence.

For all the problems with what Peck portrays in Exterminate All the Brutes, what he does not say is equally troubling. Throughout the series, Peck���s brassy authoritative voice engulfs the frames, narrating the violence depicted in a dizzying assortment of photographs, videos, animations, illustrations, and reenactments. Yet when it came to images of sexual violence, Peck is curiously silent. In one part of the series, for example, a disturbing painting titled ���The Rape of the Negro Girl��� is showcased but is given no context. In another, the viewer is shown a collection of photographs of white men sexually exploiting women in various locations throughout the world, but Peck makes no attempt to explain how sexual assault was used as a weapon of colonization.

What emerges from Peck���s exhibition of these images is essentially a conversation between men. Peck reduces the women and girls in these images to what might have been the most humiliating experiences of their lives in order to use their subjugation as evidence of white men���s atrocities. This representation of sexual violence reinforces what media scholar Ariella Azoulay has described as the tendency to think of sexual violence as incidental to the histories of colonialism. That is to say, sexual violence is presented as something that just happened during colonialism instead of being seen as an integral component of the mechanics of colonization. Not only did Europeans use sexual assault as an instrument of subjugation, the illustrations and photographs Peck displays were often circulated as postcards throughout European metropoles to encourage white men to go to the colonies to enact their sexual fantasies. White women, for their part, used these images to define their piety vis-��-vis the sexual exploitation of women in the colonies.

The ways we tell stories matters just as much as the stories we tell. Peck���s aim in this series is an ambitious and laudable one. For sure, the violence that accompanied colonial conquest needs cinematic representation. But it is not enough to simply showcase grisly images of these atrocities. Telling nuanced stories about colonialism isn���t just about telling a story of white violence. It is about completely decentering the logics of whiteness that makes us see and present history from the perspective of white men and disregard sexual violence against women of color.

What we need are well-contextualized cinematic representations of these events that move beyond exhibitions of violence and open up new possibilities for demanding accountability and restitution.

The paths toward presenting better histories of colonialism can be found in the rich traditions of resistance in communities throughout the world. From the histories of Native American opposition to Western expansion, to the revolutions against slavery and colonialism in Africa, to the ways women throughout the world continue to foreground conversations that tie the history of colonialism to the disappearance, trafficking, and murder of women in their communities, the historical record and contemporary activism make it clear that white supremacy has always been contested by the people whom it seeks to exterminate. By marginalizing these perspectives and centering white men in the series, Peck missed the opportunity to engage with the history of colonialism in a way that empowers viewers to imagine a future in which whiteness is not the locus of power and authority.

June 12, 2021

�������������� ���������� �������������� ��������

For English click here.

�������������� �������� �������� ���� ������ �������� �������� �������������� ��������. �������� ������������ ������������������ ������ �������������� ���������������� ���������� ���������� �������������� ���������������� ���������� ���������������� ���������� ������������ ���� ���������� ���������� �������������� ������������ ������������ �������� �������� ���������� ������������ ������������ ������������ ���������������� �������������� ���� �������������� ������������ ��������������. �������� �������� �������������� �������������� ���� �������� ������������ ���������� ������������ ������������������ ���������������� �������� ���������� ���������������� ���������� ����������.

������ ���� ������ ���������� �������� ���������� ���������� �������������� �������������������� �������� �������� �������������� ������������ ��������. ������ ���������� ������������ ���������������� �������� ���������� ������������������ ���������� ������ ���������� ������������ �������������� ������������ ������������ �������������� ������������ ���������������������� �������������������� �������� ������������ ���������������� ������ �������� �������� ���� ������������ ������������ ������������. �������� ������ �������� ������ �������� ������ �������������� �������������� �������� ������������ �������� ������������ ������������������ ���������� ���� �������������� ���������� ������������ ���������� �������� ���� �������� ���������� �������������� ������ ���������� ����������������.

���������� �������������� ������������ ���������� ���������������� ���������������� ������ ������������ ���� �������� �������� ������ ������������ ���� �������� �������� ������������ ���������� �������� ���������������� ������������ �������� �������� ������������ �������������� ������������������ �������������� ���������������� ���������������� ������������. �������������� ���������� �������������� �������� �������� ������ �������� ������������ ������������ �������� ������������ “���� ������ �������� ��������������” (2016) ������������ ������������ ������������ ������ ������ �������� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” (1968) ���� �������� �������� ���������� ������ ������ ���� �������������� ���������� ���� ������ ������������ �������������� ������������������ ������������.

�������� ������ “���� ������ �������� ��������������”�� �������� (������������ �������� ������ ��������)�� �������� �������� ���������� ������ ���������� ���������� �������� ���������� �������� �������������� �������������� �������������� ���������������� ������ ������ ������������ ������. ���� ���������� �������� ������������ ���� ������ 2009 �������� ���� �������� ���� ������ 2016�� ������ �������� �������� ������ �������������� ���������������� ������������������ ������������ �������� ���������� ������������ �������������� ���������� �������� ���������� �������������������� ���������� �������� ���������������� ������������ ������ ������������ ������ ���������� ���������� ������������������ ���������������� ���� ���� ���������� �������������������� ������������ ������������ ������������ ������ ������������ ������������.

���������� �������� �������� �������������� ���� ���������� �������� ���� ������ ���������� ���� ������ ��������������. ������ �������������� ���������� �������� ���������� ���������� ���������� ������ ������������: ���������� ������������ ������������ ���� ������������������ �������� �������� �������� �������� ������ ���� ���������� �������� �������� ������������ ���� �������� ���������� �������������� �������������� ���������� �������� ���� ���������������� ������������������ ����������������. �������������� ���������������� �������� ������������������ �������������� ���� ������������ ���������� ������ ���������� ������ ���������� �������������� ���������� �������������� ������������������ �������������� ������������������ ���� ���������� �������������� ���������� �������������� ���� ���������� ������������ ������������ ������������ ������ ���������� ��������������.

������ ������ 50 ������������ �������� ������������ �������������� ���� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ���� ���������� �������� ������������ ������������ ���������������� ������ �������� �������� ���� ��. �������� ���������� “���������� �������� ����������”. ���������� �������������� ���� ������ 1968�� ������ ���������� ���� ���������������� �������� �������� ������������ ������������ ������������ ���������� ������������ ��11 ���������� ������ ���� ���������� �������� ������ ������ �������� �������������� ������������ ������������������ �� ���� ������ ������������ ���������� ���������� �������� ������������ ������������ �������� ������������ �������������������� �������������� ������������ ������ �������������� �������� ����������������.

�������� ���������� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” �������� ������������ �������������� ���� ������ ������������ ������ ���������������� ���������������� ������ ���������� ���������� ������������ ������������ ������������ ������������ ���������� ���������������� �������� �������� ���������������� ���� �������� ������������ ������������ �������������� ��������. ������ ������������ ������ ���������� ���������� ���������������� ���������� ������������ �������������� �������������� ���������������� ���� ������������ ������������ ���� ���������� ���� ������ �������� �������� �������� �������� ������������������ ���� ���������� ����������. ������ ���������������� ������ �������������� ���� ������������ ���������� ������������ ���� �������� ���������� ���������� �������� ������ ���������� ������ ���� ���������� ���� �������� ���������� ���������� �������������� ������������ ������������ ������������ �������� �������� ������������ ������������ ���� ���������� ������������.

���������� ���������� ���������� “���� ������ �������� ��������������” �� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ���� ���������� ������������ �������������� ������ �������������� ���� �������������� ������������ �������� ������������ �������� ������������ ������������ ���������������� ���������� ���������� ���� ������������ �������������� �������������� ������������ ���� ����������. ������ ���������� ���� ���� �������� ������������ �������������� ���� ���������� ���� �������� ���������� ������ �������� ������ ���� ������������ ������������ ������������ ���������������� �������� ������������ �������� �������������� ���������� �������������� ������ ������ ��������������������. ������ ������������ ���������������� ���� ���������� ���������������� �������������� ���������������� �������������������� �������� ������������ ������ ���������� �������� ������������ ���������������� ������ ���� �������� �������� ���������� ������������������.

������������ �������� �������� ������������������ ������ �������������� ���� ������������ ���� �������������� ���� �������������� ������������ ���� �������� ������������ ���� �������������������� ���������������� ���������������� �������������� �������� ���� ������������ �������������� ���������� ������������������ ���� �������� ������������������ ���������������� ������������ ���������� ������������������. ������������ ���������������� ���������� ������������ �������������� ������������ ������ ���� �������� ������ ���������� ������ ������������ ���� ���������� ���� ������������ ���������� �������� ���� ������ ���������������� ��������������.

���� �������������� ������ �������� ���������� �������� ���������� ������������ ������ ������������ ���� �������� ���������� ���������� ������������ ������������������ ������ ���� ���� �������� �� ��������. ���������� ���������� �������������� ������������ ���������� ���� ������������ ������������������ ���� �������� ���������� ���������� ������������������ �������������� �������� ������������ ������������ �������� ���������� ������ �������� �������������� ������ �������������� ���������������� ������������������. ���� ������ �������� ���������� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ������ �������� �������������� �������������� ���� �������� ��������. �������� ���������� �������������� �������������� �������� ������ �������������� ���������������� ������������ ������ “���������� �������� ���������� ���������� ���� ������ ����������” ���� ������ �������� ���� ������������ �������� “���� ���������� ���� ���������� ������������”.

������ �������������� �������� ���� �������� ������ ���������� ������������ �������������������� �������������� ���������������� ���������� ������ ������������ ���� ������������ �������������� ����������������. �������� ������ �������� �������� ���� ������ �������� ������������ ���������� �������� ���� �������� ���� 120 ���������������� ������������������ ���� �������� ���������� ������������ �������� ������ �������� ���� 12 ���������� ������������ ������ ���� �������� �������� ���� �������� ������������ �������� ���� �������������� �������������� �������������� ������������������������������ �������� ������ �������������� ���������� ��������. ������ ���������������� �������� �������� ���������� ���������������� �������������� ������ ���������� ������������ ������������ ������������ �������� ���� ���� ������������ ���������� �������������� ������������ ���������� �������������� �������������� �������� ���� ���������������� �������������� ������ �������� ������������ ������������������ �������� ���������������� �������� ������ ������������ ���������� ���� ������������ ������������. ������ ������������������ �������������� ���������� �������� ���������� �������� ���� ���������� �������� ������ ������ ������������ ���������������� ������������ ������������ ���� �������� ������ ���������� �������� ������ “������������ ������������”�� �������� ������ ������������ �������������������� ����������������. .

������ ������������������ ���������������������� ������������������ ���������������� �������� ������ ������ �������������� ��������������. ������ �������� �������� ���������� ������������ �������� ���������� ���� ������������ ���� ������������ ���������� ���������������� ������������ ���������� ������������ ������ �������� �������� ������ ���������� �������� ������������ ��������. �������� ���������� ���������� �������� �������� ���������� ������ ������ �������������� �������������� ������ ������������ �������������� �������������� ���������� ��������������. ���������� �������� ������ �������������� ������������ ���������������� ���������� �������������� ���� ������������ ���������� ���������� ������������ �������������� ���������� ������������ ������ ������ ���������� ���������� �������� ���� �������� ������������ �������� ������ �������� “�������� ��������������” ���� ��������������. �������� �������������� ���������� ������ ������ ������������������ ������ ������ ������ ������������ ������������������ ������ ������ �������� ������ ������������ �������������� ������������ �������� �������� ���������� ���������� ���������������� �������������� ���� ������ �������������� ������������ ������ �������� ������������ ���������� ���������� ������������ ������������ ������������. ������ ���� ������ ������ �������� ���� �������� ���������� ������������ �������������� ���������� ���� ��������������. ������ �������������� ������ ���������� ������������������������ ���� �������� �������� ������������ �������� ������ ������������ ���������� �������� ���� ���������� ������������ ��������������.

������ ������������ ������������ �������������� ���� �������� �������� ������������ �������� ���� ���������� ������������ ������������. �������� ������ ������ ���������� ���� ���������� “������ ������������”�� “������������ ������������ �������������� ������������”. ���� ���������� ���� ���� �������� ���������� ���� ���������� ���������� ������ ���������� �������������� ������������ ���������������� ���������������� ���������������� ���������������� ���� ���������� ��������������. ������������ ���� ���� �������� �������� ������������ �������������� ������������ ���������� ���� ������������ ���������� �� ������ �������� ������ ���������� �������� ������������ ������������������ �������� ���������� ������������ ������������ ���������������� ������������������ ���������� ���� �������� ���������� �������� ������������ ������ ������������ ������������ ���������� �������������� ������ ���� ������������ ���� ������ ������������ ������������. ���������� ���� �������� ���������� ������������ ������ ������������ �������� ������������ ������ �������������� ���� ������������. ���������� �������� �������� �������� ���������������� ���� �������� ���������� ���������� �������������� ������������ �������� ���� ������������ ���� ���������� ���������� ������������������. ���� �������� �������� ���� “���� ������ �������� ��������������”�� �������� ������������ ������ ������ �������� ���� ������ ���� ������������ ���������������� �������������� ������������ ���� �������������� �������� �������� ������ ������������ �������� �������� ���������� �������������� �������� ���������� ������ �������� �������� ������������ ����. ������ ������������ ���� �������� �������������� �������� ���������� ���������� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ������ ������ ���������� ���� ���� ���������� ������ �������� ������ ���������� �������� ���������� ������������ ���� ������������ �������� ���������������� �������������� �������� �������� �������� �������������� ������ ���� ������ �������� �������� ������ ���������� �������� �������� ���������� ���� ���������� ������ ���������� ���������� ������������.

������ �������������� ������������ ���� ������������ �������������������� ���� ������ �������������� ���������������� �������� �������� ���������� �������� �������� ������������ ���� ������������ ����������������. ���� ���� �������� ���� “���� ������ �������� ��������������” �������� ���������� ������������ �������������� �������� ���������� �������� ������ ���������������������� ����������. ������ �������������� ������ ���������� �������������� ���� ������������ ���� ���������������� ���������������������������� ������������ �������� ������ “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ���� �������������� ���������� ���������� ���������� ���������� ���������� ����������: “���� ���������� ������������ ������������ �������� ���������� ���������� ���������� �������� ���������� ��������������: “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������”. ���� ������ ���������� ���������������� �������� �������� �������� ������������ �������������� ������ ���������� �������������� ���������� ���� ������������.” �������� ���������� �������� ���� ������ ���������� ���� ������������ ������ �������� ������ �������������������������� ���������� �������� ������������������ ���� ���������������� ������ ������ �������������� �������������� �������� ���������� ���� �������� �������������� ������ �������� ������ �������� ���������� ������ ������������������ ������������������ ������������������ �������� ���� �������� ���������� ������������ ���������� ������ �������� ���� �������� �������� �������� �������� ����������.

������ �������������� ���������� ���� ������������ ������������ ���� ��������������. ������ ������������ �������������� ���� “���� ������ �������� ��������������” �� “������ ������������ ���� ������������ ������” ���������� ������ ������������ �������� ���������� ������������������ �������������� ���� ��������������. �������������� �������� ���������� ��������������. �������� ���������� ���� ���������� ��������������.

June 11, 2021

A different picture of the struggle

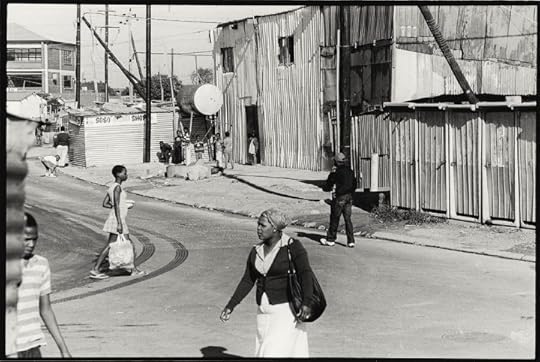

Photo: Louise Reynolds, via Flickr. Creative Control Licensed.

Photo: Louise Reynolds, via Flickr. Creative Control Licensed. In April 2014 I found myself in the dining room of a family home in Diepkloof, Soweto, speaking to two middle-aged women about their experiences of the political uprisings that engulfed Soweto and other townships across South Africa during the final, turbulent decade of apartheid in the 1980s. As one woman laid down a tray of coffee and vetkoek, the other, Zanele, interjected, ���You know, the petrol bomb is very powerful.��� She proceeded to tell me about how, as a teenager and school student, she herself had participated in the township uprisings by targeting white-owned businesses and bus companies with stones and petrol bombs. Listening to the recording of our interview later, the banal hums of domesticity���the stirring of teaspoons and clinking of cups���sounded in stark contrast to Zanele���s descriptions of burning vehicles, police birdshot, and rolling Casspirs in Soweto���s streets.

In previous histories of South Africa���s liberation movement, the involvement of girls and young women like Zanele is all but missing. From the mid-1970s, Black children, students, and youth were the vanguards and shock troops of the anti-apartheid struggle. But these young activists have been depicted as a primarily male and deeply masculine group. As township politics grew increasingly confrontational and dangerous during the mid-1980s, girls and young women were thought to have been largely excluded from the struggle and increasingly confined to the home.

Yet from 2014 to 2016 I met and interviewed dozens of former comrades from Soweto, all of whom had given up their habitual lives as teenage girls to fight against apartheid by joining ANC-aligned student and youth organizations in the 1980s. Now middle aged, these women were eager to share their past experiences, and their stories repudiated the idea that girls were absent or sidelined from political activism during these years. While they were far fewer in number than their male counterparts, these women still protested in the streets, confronted security forces with stones and petrol bombs, took on leadership roles in their communities, and were detained, interrogated, and tortured by the apartheid state.

Their narratives placed them at the very center of the township uprisings and emphasized how, despite the stereotypes attached to their gender, they were willing to risk their lives for the struggle just like boys and young men in their communities. ���Our heads were so hot, we didn���t want to be left at the back,��� Zanele explained. If her male comrades ever discouraged her from participating in dangerous or physically demanding missions, she���d protest: ���No, we are going there. Why must we stay behind? Because we were all fighting. If you throw a petrol bomb, I throw one too. If you mixed the petrol bomb there, I want to know, how did you mix it?��� In many ways these women���s narratives conformed to archetypal images of the fearless, heroic, but at times over-zealous comrade inscribed in collective memories of South Africa���s liberation struggle. But because this image is so starkly masculine, the female comrades I interviewed were often more intent than men to clearly demonstrate their valor and proficiency as stalwarts of the liberation movement. Zanele spoke of how she was often the first and most eager among her group of comrades to chase after and discipline suspected police informers, and how she felt no fear when confronting security forces in township streets.

Yet in many other ways, the stories these women tell expand and complicate our current understandings of the liberation struggle, as they highlight issues often eclipsed or overlooked in men���s accounts. Zanele spoke of the struggles female comrades faced in trying to balance their identities as both daughters and activists. ���It was a little bit difficult,��� she sighed, explaining how she was forced to choose between attending political meetings and completing her household chores. ���Maybe it was easy for men but for us it was difficult because I got beaten everyday by my grandmother. If I didn���t finish to do this [cooking, cleaning] ���I was beaten, maybe in a week, thrice.���

Once the police became aware of Zanele���s political activities, her home life was further complicated. Her grandparents forbid her to stay with them anymore, fearing she���d bring the police to their door. While Zanele at times expressed pride in rebelling against her domestic duties and parental pressures, she also spoke about the personal difficulties her politicization caused: ���It was so painful, because I missed them. I want to see them, you know? I want to change my clothes. But I wasn���t allowed���it wasn���t safe for me to go home.���

These women���s stories thus tell us about how activism was lived on a day-to-day basis, and the struggles it brought to young people���s private and family lives���topics rarely explored in current histories which tend to prefer comrades��� more public identities and activities.

Zanele���s narrative was punctuated with the full spectrum of human emotion. She spoke candidly about how angry police informers made her (���I hate those people���, she repeatedly stated). She laughed when discussing how she and her friend would enforce a consumer boycott, demonstrating the thrill such confrontations brought. But she also expressed remorse for disappointing her grandparents, for attacking bus drivers during a bus boycott, and for destroying the groceries of those caught shopping at white-owned stores. Her narrative was at times contradictory and ambivalent���she would long for her days as a young activist and the excitement this brought, while also lamenting just how difficult those years were and the high price she paid for her political involvement.

These oral histories offer us a different picture of the struggle than those usually told by men: one that is messy, non-linear, and startlingly candid. It is no rosy, unequivocal, celebration of a war won. It is an introspective tale of what it meant to be a young woman against apartheid, both at the time of the liberation struggle and in the three decades since.

June 10, 2021

Three psychologies of Mau Mau

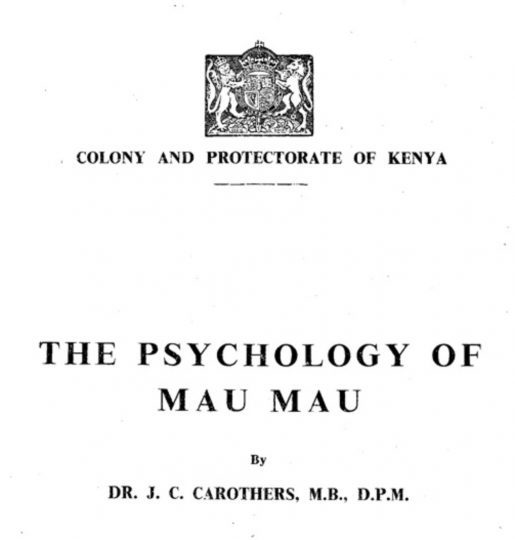

The cover of J.C. Carruthers' infamous "The Psychology of the Mau Mau." The full text of the book is online.

The cover of J.C. Carruthers' infamous "The Psychology of the Mau Mau." The full text of the book is online. This post is part of a limited series, Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

In 1951, a prominent British medical journal on mental disease published the now-notorious account from Dr J.C. (John Colin) Carothers on ���frontal lobe function and the African.��� While such racist pseudo-sciences were ubiquitous throughout the colonial period, this article contained the rather shocking analogy comparing the brains of ���normal��� Africans to that of leucotomized (lobotomized) Europeans. Although the original article is lost somewhat to obscurity, its hypothesis has been a mainstay in much of the historiography surrounding the racist science behind what can be called a ���colonial psychiatry.���

Since Megan Vaughan���s seminal article on ���Idioms of Madness in a Nyasaland asylum��� (1983), a robust sub-genre in medical history scholarship has followed suit to explore the concepts, confinements, and rhetorical abuses of colonial institutions across their occupied territories. Kenya, as is often the case, looms large. This is due, in part, to the work of Carothers throughout the 1940s from Nairobi���s Mathari Mental Hospital, which followed on from an ugly eugenicist turn amongst white settler physicians in the 1930s. The body of work by such physicians appearing frequently within the pages of the East African Medical Journal and the later, more substantial, publications by Carothers in the early 1950s, solidified what came to be known as the East African School of psychiatry with Carothers as exemplar.

Carothers is known for three influential publications; the aforementioned article on frontal lobe function, a widely read World Health Organization monograph, The African Mind in Health and Disease (1953), and a British government commissioned treatise on the Mau Mau rebellion, ���The Psychology of Mau Mau��� (1954). Despite his prominence in some quarters, and the expectation that his years of service at the helm of Mathari qualified him as an expert witness on African mentalities, Carothers��� work did not receive a quiet acceptance among his contemporaries. Experts from psychiatry and anthropology weighed in with responses to the WHO monograph with scathing reviews appearing in equally prominent journals. Lest Carothers��� stance on race appear unclear, critics made direct references to his racial and biological determinism���fair play, considering Carothers himself cited his frontal lobe theory in his later works.

Frantz Fanon, critiquing the agony of the colonial situation, referred directly to the sinister nature of the work emanating from Kenya and from Carothers specifically. Although Fanon had many targets, Carothers��� infamy was cited in a summing up of his chapter on ���Colonial War and Mental Disorders��� in The Wretched of the Earth with commentary on the damage done by the widespread acceptance, even in university teaching, of the ���uniform conception of the African.���

���In order to make his point clearer��� Fanon wrote, ���Dr Carothers establishes a lively comparison. He puts forward the idea that the normal African is a ���lobotomized European.�������� Unlike Fanon, J.C. Carothers was not actually trained as a psychiatrist (he completed a diploma course in psychology while on leave in the UK). He utilized the patient population of Mathari Hospital and a general armchair anthropological tendency that infected many colonial administrators, to publish his findings about the nature of the ���normal and abnormal��� African. Although he lacked genuine academic credentials, he did enough to beat out experts like Melville Herskovitz (a prominent figure in the founding of modern African Studies in the US) to win the WHO commission. Despite this intellectual coup, the book was seen as a racially charged blemish on the organization and was controversial the moment it was released.

Melville Herskovitz��� review warned that the potential damage caused by the publication was palpable. ���For where, as in Africa, stakes are high and tempers are short, anything this side of the best scientific knowledge will accelerate existing tensions and make their resolution the more difficult.��� The impact of the book might have remained fairly academic; it was, after all, an extended institutional report with a poorly constructed literature review. But it gave Carothers an air of authority as an expert on African psychology amidst a period of turmoil and increasingly violent demands for independence.

By the time the state of emergency was declared in Kenya in 1952, Carothers had already returned to the UK. When the British government called on him to provide his opinion on the psychological impulse behind the Mau Mau rebellion, he was able to oblige from the comfort of home by plagiarizing substantial aspects of The African Mind with added polemics about the ���forest psychology��� of the Mau Mau. He made a brief government sponsored visit in 1954 to observe the detention camps, and his visit to Manda Island was documented in a scant entry in Gakaara Wa Wanjau���s Mau Mau Author in Detention. The result was a widely read government pamphlet, ���The Psychology of Mau Mau,��� which not only explained the reasons why Kenyans had resorted to violence, but also laid out a medicalized rationale for what to do about it.

Under the radar, in the mid-1950s, another psychiatrist had a mandate to visit the camps. However, so dominant is the Carothers narrative of East African psychiatry, these two doctors are generally not compared as such. Edward Lambert Margetts was a little-known psychiatrist from Canada who had the distinction of having overseen Mathari Hospital during the Mau Mau war. In stark contrast to Carothers, Margetts made some surprising observations about the trauma of detention camps���although it must be said that he was no sympathizer to the Mau Mau cause. Despite a penchant for collecting, documenting, and writing, he eschewed any opportunity to write about the Mau Mau war directly, but he too was invited to visit detention camps and to examine detainees brought to Mathari. Camp superintendents had little interest in big picture theories about the African mind, but they were keen to expose specific prisoners who were suspected of feigning mental illness as a means of escaping hard labor.

While some of Margetts��� notes are uncharacteristically cagey, he observed key patterns amongst a small number of detainees held in camps as well as Kenyans living amidst Mau Mau chaos. Most fascinating are medical notes with a term coined by Margetts ���Mau Mau perplexity fear syndrome��� in which he documented the anguished testimonies or panicked delusions of Kenyans who lived under a constant terror of violence. For detainees, Margetts made a remarkable observation that while some prisoners might well be ���malingering,��� others exhibited signs of dissociation caused by extreme trauma related to their confinement. Ganser Syndrome (after Sigbert Ganser, 1898) was also known as ���prison psychosis��� and included an array of unusual symptoms such as hysterical blindness or the compulsion to give nonsensical answers to easily understood questions. Margetts queried whether some detainees could be considered under this diagnosis���an indication that some of the trauma in Kenya might be attributable to British administration of the war and not the innate savagery of the African personality.

Frantz Fanon also referred directly to Carothers��� ���Psychology of Mau Mau,��� and to the government���s concurrence that the ���revolt [was] the expression of an unconscious frustration complex whose reoccurrence could be scientifically avoided by spectacular psychological adaptations.��� If Fanon was aware of Margetts at all, he would likely have conflated his views with those of his predecessor within the East African School. Fanon noted that Carothers��� work dovetailed with the types of claims made by the North African School. and the credence given to such ideas made the corruption, and ���tragedy��� of colonial medicine all the more evident.

Although they were contemporaries, these three psychiatrists had little in common, although two of them challenged the ���Mau Mau as mental disease��� paradigm from the distinct vantage points of clinical curiosity and revolutionary political thought. There are still many avenues to pursue within a scholarship concerned with psychiatry���s entanglement with colonial politics and violence, but perhaps J.C. Carothers output has had a shelf life beyond what it should have done. Edward Margetts��� tenure at Mathari is not unproblematic, but nonetheless leaves a very different intellectual footprint. From his clinical notes and writing, we may apply a bit more nuance and tension to the otherwise flat depiction of Carothers��� overt racism.

The ���East African school��� represents a paradox between a scientific community that for the most part knew better in the 1950s, and the undeniable influence of racialized intellectual outputs placed in just the right circumstances to do the most damage.

June 9, 2021

The Nigerian and the Lenin Prize

A street scene in Nigeria's commercial capital, Lagos. Very few people in Nigeria remember or know about Peter Ayodele Curtis Joseph, a businessman and nationalist politician (Photo: Satanoid, via Flickr CC.)

A street scene in Nigeria's commercial capital, Lagos. Very few people in Nigeria remember or know about Peter Ayodele Curtis Joseph, a businessman and nationalist politician (Photo: Satanoid, via Flickr CC.) In May 1966, the politician, businessman, and writer Peter Ayodele Curtis Joseph became the first Nigerian ever to receive the Lenin Peace Prize. The prize, which named its first winner in 1950, was originally named the Stalin Prize 1950 to 1955, but was changed to the Lenin Prize two years after Stalin���s death following a period of de-Stalinization. Its last recipient was Nelson Mandela in 1990. In addition to Mandela and Curtis Joseph, a number of prominent Africans and members of the African diaspora have won the prize, among them Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Bram Fischer, S��kou Tour��, Kwame Nkrumah, Modibo Keita, Ben Bella, Jean Martin Cisse, Sam Nujoma, Samora Machel, Agostino Neto, Abd al-Rahman al-Khamisi, and Julius Nyerere. Curtis Joseph is not the only Nigerian to be awarded the prize. In 1971, the Lenin Prize was awarded to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, the activist whose children include the musician Fela and the doctors and activists Beko and Olikoye (the latter of whom also served as Nigeria���s health minister). But unlike Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, who is now remembered as a feminist and nationalist in Nigeria, Curtis Joseph has been largely forgotten.

Peter Ayodele Curtis Joseph died in December 2006, and November 8th of last year marked the centenary of his birth. But barring a commemorative event held in his memory at the 22nd Lagos Book and Art Festival on November 10th, 2020, fourteen whole years have passed since his death���years in which Nigerians have not done much to remember, honor, or celebrate this unsung hero.

How do we commemorate someone effectively unknown to history? It is usually the case in Nigeria that those who credit her independence to nationalist leaders like Nnamdi Azikiwe, Obafemi Awolowo, and Ahmadu Bello have no clue whatsoever who militant nationalists like Nduka Eze, Kola Balogun, and Raji Abdallah are. The reason for this is pretty simple: many Nigerians are totally unaware of the roles these people played during the struggle for independence from the mid-1940s to early 1950s. Even more, average Nigerians are completely oblivious to the existence of a Nigerian left. This in part explains why the story of Curtis Joseph, a member of the Nigerian left, remains largely untold.

Curtis Joseph was born in 1920 in Benin City, where both his father and mother had roots. His father, Joseph, was a peasant farmer, and his mother, Mary, a petty trader. Curtis Joseph grew up in Ikare, in the present day state of Ondo, where he started schooling under the West Indian educationist Reverend Lackland A. Lennon in 1928. He later attended schools in Oshogbo, the present-day state of Osun, and in Owo, the present-day Ondo. Curtis Joseph���s Yoruba middle name, Ayodele, was given to him by members of the Ikare community. In protest against the already rising wave of tribalism in those days, he later exchanged his surname for his father���s baptismal name.

His family fell on hard times, and at 15, barely out of school, Curtis Joseph went to work as a shop assistant. Not long after, he was hired in the Agricultural Produce Section by the United African Company (UAC), a prominent British trading company in West Africa. Ikare was a trading point for the cocoa produced in its surrounding areas.

Drawing on a salary of 15 shillings monthly, Curtis Joseph enrolled for correspondence courses in politics, philosophy, journalism, and commerce. In 1944, he resigned his job, but returned to take up another post for UAC in Okitipupa, or present-day Ondo state. Unfortunately,�� it is difficult to say with any certainty what prompted this resignation.

Two years later, in 1946, the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), a political party led by Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, was ushered into Okitipupa by Curtis Joseph during its countrywide effort to marshal a nationalist opposition to the Richard constitution. The NCNC���s opposition to this constitution was not only on the grounds that it introduced regionalism into the colonial administration and politics in Nigeria, but also because it made no provision for Nigerians to participate in running their own affairs. Curtis Joseph also helped raise money to enable the party to send a protest delegation to the Colonial Office in London.

In 1947, while still working at UAC, he used a pen name to write about the NCNC. His bosses at the UAC were not pleased, and this may have contributed to him leaving the UAC in 1951. The UAC, working through the Association of West African Merchants, wanted to increase its political influence as Britain was decolonizing Nigeria.

But Curtis Joseph���s reasons for quitting had more to do with UAC���s poor treatment of its senior African employees. At about the same time, starting in 1948, the UAC had pursued a policy of sponsoring its politically ambitious Nigerian employees for elections. Curtis Joseph, however, would not be persuaded by friends to stand for election in Benin during the first general elections of 1951. Instead, for his independence of mind, he chose to set up a small trading business that could help secure his bread and butter and enable him to write for free for the West African Pilot (Azikiwe���s newspaper) and other media.

This is also around the time that he was exposed to left-wing ideas. Though he had encountered Marxist literature by the mid-forties, his embrace of it would happen between 1951 and 1961, mainly because of his political and business activities. In this period, as Curtis Joseph realized that it had become necessary for Nigerians to build a solid front to fight against foreign monopolies, he increasingly resolved to leave the UAC. These events directly contradict the claim that Curtis Joseph had become a Marxian radical by 1944, which was made by Adam Mayer in his book, Naija Marxisms: Revolutionary Thought in Nigeria.

After the disappointment of spending five years trying to pool resources with others for the purpose of building the solid front he envisioned, Curtis Joseph proceeded in 1956 to set up his own firm, Nigeria Import & Export Agency Ltd. His trading company, then located in what is today the Akowonjo area of Lagos, started exporting crushed bones, scrap metals, and shea nuts. In building his company, Curtis Joseph had decided to challenge the monopoly of British merchant capital in Nigeria himself.

In 1951, a 30-year-old Curtis Joseph joined the World Council of Peace (WCP) after reading about it in a magazine. He became the first Nigerian to gain membership in the organization. His strong belief in world peace���perhaps seeded when he had read the entire Bible as a teenager���stirred his interest in the activities of the WCP. Equally strongly, he held that Marxism-Leninism was the only ideology capable of birthing a just and peaceful world. Soon after establishing contact with the Soviet Weekly and drawing on his WCP affiliation, Curtis Joseph set up a bookshop through which he sold and distributed imported pamphlets and books about Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet Union.

This book enterprise���which was mostly unprofitable���caused tongues to wag his way. It was one major reason for his constant run-ins with the Police Special Branch, which had been formed on the heels of the ban placed on the Zikist movement in 1950 and at the height of the Cold War. Of course, another factor was his membership in the WCP, which, according to a declassified report released by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 2015, was said to have been an international front funded and controlled by the Soviet Union for the purpose of carrying out overt forms of ���active measures.���

The Zikist movement, which came into existence in February 1946, was the brainchild of four young radical journalists: Kolawole Balogun, M.C.K. Ajuluchukwu, Abiodun Aloba, and Nduka Eze. The movement at the time was initially formed to protect and defend the life of Azikiwe, who towards the end of the General Strike of 1945 alleged that the colonial government planned to assassinate him. By November of 1949, about five months before the colonial government���s ban and one year after its open lecture titled, ���The Age of Positive Action,��� the left-leaning Zikist movement was already organizing rallies, protests, and demonstrations in Enugu, Lagos, and other cities in the wake of the Iva Valley Massacre.

The ordeal of Mokwugo Okoye���who, as the secretary general of the Zikist movement, was jailed for almost three years for possessing ���revolutionary pamphlets������best illustrates the radical ferment of those times. Before his sentencing, Okoye refused to make a plea and instead insisted���just as Zikists Raji Abdallah and Osita Agunwa did in November of 1948���that his case with the colonial government was between Nigeria and Britain. He worsened the situation by describing the African judge as ���a symbol of imperialist machinery.��� Okoye���s arrest in 1950 came after Chukwuma Ugokwe���s failed attempt to assassinate Sir Hugh Foot, who was then chief secretary for the colonial government.

In May of 1950, just one month after the colonial government declared the Zikist movement an ���unlawful society,��� Nduka Eze, M.C.K. Ajuluchukwu, and other ���free��� Zikists launched the Freedom Movement. But as the specific Zikist tendency within the Nigerian radical movement had begun to wane in 1951, some of its members decided to join other political formations. While people like Mokwugo Okoye, Osita Agunwa, and Kola Balogun remained in the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (which the Zikists were the radical wing of), others like Nduka Eze, S.G. Ikoku, and Raji Abdallah jumped ship. Curtis Joseph, who for his part had been a member of the NCNC since the 1940s, left bourgeois party politics in 1958. He was not a Zikist.

In the early 1950s, alongside other Nigerian socialists like Gogo Chu Nzeribe, Tanko Yakassai, M.O. Johnson, and J.B.K. Thomas, Curtis Joseph initiated a Marxist-Leninist discussion group that culminated in the formation of the left-leaning Nigerian People���s Party (NPP) in 1961. At that time, Curtis Joseph and his peers believed that the dismal state of the nation demanded a major regrouping of what then remained of the Nigerian left. Due to the provisions of the Macpherson constitution, the situation in Nigeria was such that the Nigerian feudalists (Sir Ahmadu Bello and Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa) and their bourgeoisie counterparts �� (Chief Obafemi Awolowo and Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe), both of whom had taken over from the British colonialists, were engaged in a bitter struggle to consolidate power at the center and in the regions.

Specifically, it was the power tussles between the Northern People���s Congress, Action Group, and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens in the Northern, Western, and Eastern regions of Nigeria���all of which were waged at the expense of the masses���that necessitated the formation of the NPP. Ideologically, the NPP was opposed to regionalism and favored a unitary system of governance. It reasoned that without vast transformation aimed at changing the lives of its great masses of people, Nigeria would remain ���backward, economically dependent and politically docile.��� To effect the desired change, the NPP pledged to stage an obdurate fight against capitalism.

Sometime in 1961, Curtis Joseph attended his first WCP conference in Helsinki, Finland. The following year, as founder of the Nigerian Council for Peace (NCP), he led the Nigerian WCP delegation to the Moscow Conference for peace and disarmament. In his capacity as founder and president of the NCP, he was elected a member of the WCP Presidential Committee at the Geneva Conference in 1965. By May of 1966, the month that the NCP was banned by the military regime of General Aguiyi-Ironsi, Curtis Joseph had become the first of only two Nigerians to be awarded the International Lenin Peace Prize. His medal, presented to him at the Kremlin by Dmitri Skobeltsyn, was more for the work he put into the struggle for world peace, and less for his campaign ���for trade with the USSR,��� as Mayer claims in Naija Marxisms.

Mayer regrettably fails to cite his source, but the aforementioned CIA report does affirm that the WCP was an international Soviet front established in April of 1949 in protest of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Regardless of the rationale for his award, it is true that after the visit to the International Trade Fair in Brussels where he established initial contact with Soviet trade organizations, Curtis Joseph came back to Nigeria in 1958 to lead the charge for trade with the Soviet Union and other socialist countries. That campaign, which resulted in a trade agreement between Nigeria and the Soviet Union in 1963, is what most likely secured him the Gold Medal and Ribbon award from the Czechoslovak Society for Foreign Relations in 1965.