Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 124

June 30, 2021

An oblique public voice

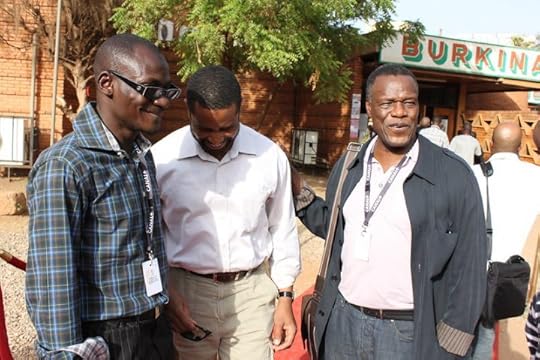

Filmmakers Mikail Isah bin Hassan and Nasiru B. Mohammad with Manthia Diawara. Photo by Carmen McCain CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Filmmakers Mikail Isah bin Hassan and Nasiru B. Mohammad with Manthia Diawara. Photo by Carmen McCain CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Three years after publishing African Cinema: Politics and Culture, his first book and perhaps the most cited scholarly text in African cinema criticism, Malian-born author and filmmaker Manthia Diawara released a documentary titled Rouch in Reverse (1995). This halting homage and evaluation of the impact of Jean Rouch, the famous French cine-ethnographer, is a perplexing achievement in using privileged access as an opportunity for critique, a work limited by the process that makes it possible. In the words of Diawara, the film���s narrator, Rouch would not have entertained such requests from many filmmakers. Those who might be upset that Diawara let his man off too easily can take solace in the fact that this was his first film, and that making films is not easy.

Trained as an engineer, Rouch moved to West Africa after World War II. Starting from 1947 and through the 1980s, he made over a hundred ethnographic films about a broad variety of topics in African history, the French-speaking countries his stomping grounds. The reach of that work is so far and deep that any proposed attempt to turn the camera on him���to reverse the gaze, as it were���had better be ready to beat the man at his game. The film Petit-��-Petit (1970) is Rouch���s controlled permission for such an undertaking; in it, he gets his African collaborators���figures such as Safi Faye, Damoure Zika and Ilo Gaoudel���to ���study��� French natives in their natural habitat. Compared to Chronicle of a Summer (1966), the great exemplar of cinema verit��, however, Petit-��-Petit comes across as light amusement.

Soon after his first film, Diawara published In Search of Africa (1999), a book of integrated chapters that, though dealing with scholarly materials more suited to classrooms and the lecture circuit, are written in the style of a personal essay. The book has a film component, and thus staged, the writer-filmmaker fashions a style and an attitude. He has since kept at it.

With An Opera of the World (2017), Diawara���s essay-films arrive at a clarifying pass. It is perhaps his most conceptually heightened work to date. It has a self-consciousness that comes from the conceptual nature of migration as a contemporary phenomenon and the classical elements that are associated with the opera as a form. The way the film is edited also makes it increasingly easier to appreciate what the writer-director is trying to do in his films���what one may call the defining, or recurring, features of his work as a filmmaker. By using the ideas of philosophically inclined Martinican writer ��douard Glissant to frame the editing of the film, Diawara seems, finally, to have come to an idea of his own intellectual practice. One can say that his previous films have been attempts at developing just such an idea���that he had been in search, not so much of Africa, as the title of his second book has it, but of a voice that can carry the weight of what he has to say.

Working with limited resources and primarily through commissions from European cultural institutions for mid-scale shows for galleries, Diawara has directed nearly a dozen films. These films are typically hamstrung to rely on interviews and staged incidents that Diawara largely���though unobtrusively���mediates. In Conakry Kas (2004), he travels with a cameraman to Conakry, the capital of Guinea, from which his family had been expelled during S��kou Tour�����s rule. There, he films an impromptu performance in an open-air arena. The performers, like the venue, are relics of the African Ballet, the dance company created by nationalist poet Keita Fodeba���the same poet about whom Frantz Fanon writes with fierce optimism in his classic The Wretched of the Earth (1963), and who ultimately fell out of favor with S��kou Tour�� and was executed for imagined conspiracies.

Bamako, the Malian capital and Diawara���s birthplace, is where his family relocated to from Guinea. It is also the setting of Bamako Sigi Kan (2003), which unfolds as a series of deep-focus encounters with figures of the Malian elite, acquaintances of the filmmaker. They debate social, sartorial, and economic issues, arguing over migration to France. Diawara sits among them but never appears on camera. Strikingly, his cameraman, African American poet and filmmaker Arthur Jaffa, is shown walking along a Bamako street.

The film N��gritude: A Dialogue Between Soyinka and Senghor (2015) pitches the ideas of the Nigerian-born Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka against those of L��opold Senghor, the founding president of Senegal and a leading proponent of N��gritude, a quasi-philosophical idea about the natural essence of blackness. Soyinka, younger than Senghor by nearly three decades, animated African literary circles in the early 1960s with his famous quip, ���A tiger does not need to proclaim his tigritude; he pounces!��� He has frequently tried to add nuances to that bon mot: later in his writings, he came to affirm several of the notions about N��gritude, becoming close friends with Senghor and writing about him at different times with the kind of interest that few black writers have extended to the legendary poet. The tiff initiated by that original pronouncement has endured, however; it becomes, in the film, the basis for Diawara���s quest to think through issues of democracy, multiculturalism, and the like. The dialogue that he sets up between both men is uneven: Soyinka responds to real-time questions while the viewer encounters only brief, isolated footage of Senghor���s interviews.

Diawara���s preferred cinematic style is poised, conversational, and deliberative. It is an approach that, as he offered once in defense of the overall tone of his work, has allowed him to bypass academic protocols in his reflections on African and black intellectual traditions. Where scholars go out to the field, to the site of material, with a pen and a notebook, Diawara brings a camera that, though he doesn���t himself wield it, often shapes how and what he sees. La Maison Tropicale (2009) is about an architectural curiosity���the building of French-style houses in tropical countries���and another person might approach the topic as a journal article.

Even when he turns to materials that typically invite scholarly analysis, as he does in African Film: New Forms of Aesthetics and Politics (2010), Diawara���s mode of engagement is light and exploratory. He writes with a clear voice, and the outlay of his ideas, projects, and hunches mimics a kind of cinematic language, unobtrusively processing sound and sundry images from Berlin, Ouagadougou, Cape Town, and Lagos into a curatorial thesis. This approach gives room to other voices that range from voluble to sententious, and Diawara looks on patiently, nodding, pulling back, trusting in the editorial stage to bring discussions or disagreements to some sort of closure.

The strongly public voice has never been hard to hear in his films, but it has always sounded politically oblique. It is as if, to Diawara, the standing of the African intellectual out of home, a simultaneously political and aesthetic stance, can only be inferred from the editorial process; as if the act of making that inference in one case requires the kind of cultural sophistication that comes from having known all the other films.

In An Opera of the World, Diawara���s voice finally becomes audible as directly political. He succeeds in subordinating the personal perspective that is integral to the essay-film to the political character of migration as a Malian, African, and global issue. His editorial choices, and especially the manipulation of the soundtrack against archival images, open up���against all attempts at suturing���the wound of voluntary, precarious migration as a transnational eyesore.

It is worth noting that this film is based primarily on a libretto���Bintou Were, A Sahel Opera���by Chadian playwright Koulsy Lemko; it was performed in Bamako at least ten years before the film was made. This is important because it makes it possible to view this film in comparison with works like Abderrahmane Sissako���s Bamako, which was released in 2006, and with Diawara���s own ���malaria��� memoir, We Won���t Budge (2003). One consequence of such an approach is an increased awareness of the diverse forces driving not only the quest after European refuge among young and old African expendable populations, but also the prioritization of this phenomenon in artistic narratives.

Are there, for example, comparable quests within the West African subregion, that is, Malians moving to Accra, the way Nigeriens and Burkinabes used to go looking for work there and in Abidjan?

In his sole appearance in the film, Lemko discusses the nature of chanting in African art. The delivery mode of the griot, a mixture of chanting and singing, seemed so suited to opera, and the major characters, especially Bintou and the smuggler, do the incredible work of acting���making Soninke sound, well, operatic. It would have been more helpful for an understanding of this claim if Lemko had more time to speak about his work, and in particular about the process of composing this particular libretto. Without the cinematic device of assemblage through which the opera is edited into a singular narrative of migration, Bintou Were is sufficient as a regional documentation of the phenomenon; it carries a weight different from Bamako, where migration, though similarly fraught, is just one of several set pieces.

But at best, this sufficiency can only be inferred. The editing puts the viewer in the reflexive position of watching the opera as a show, one set against theoretical analyses of opera as form. These analyses are presented by Alexander Kluge, Richard Sennett, and Diawara himself. The placement of that meta-commentary, in addition to other elements of standard practice such as interviews with Senegalese writer Ken Bugul and other activists in the cause of migration, feels uneasily like European theoretical elaboration of African artistic raw materials. Without Lemko���s own explicit comments, the viewer is left with little more than speculation about the status of the poetic or narrative acts that power the recorded performance. Listening to those scholarly discussions of opera brings to mind the ponderous question posed by scholar Abiola Irele in his essay, ���Is African Music Possible?��� ���What novel contribution to the universal patrimony of music,��� he asks, ���can be made by a work written for that wonderful instrument [the kora]���say, a ���Concerto for Kora and Orchestra������that has not already been made by the organic fusion of oral utterance with song in the Manding epic of Sundiata?���

Nonetheless, these analyses, especially those by Kluge and Sennett, are worthy of attention���as are Diawara���s interjections. Kluge���s definition of opera is different from but not necessarily opposed to Lemko���s. This is Glissant���s tout-monde in practice: to stand in the world rather than for the world. That the film does not reveal much more about the perspective of the Chadian author is an editorial decision that Diawara has to answer for.

The film achieves its high moment in two justly climactic instances. When the diegetic sound of Bintou���s hollering and the percussion in Oumou Sangar�����s song are intercut with the image, from Al Jazeera, of exclusively Eastern or Middle Eastern refugees making a rough passage, we see the linked destinies of all refugees irrespective of age, region, or color, an intimation of the eventual objective method of statistical accounting in which the phenomenon will be rationalized. Diawara does not make the point, or even create sufficient contexts to make it suggestive, but making Greece the setting of some of the encounters invites a particular kind of reflection. Greece was the classical ���root��� of racialized European civilization, but it became the paradigmatic insolvent nation-state some years ago. It remains, too, one of those regions where Europe comes into contact with its racial or cultural others. Furthermore, Bintou���s willful murder of her newborn baby is reminiscent of Toni Morrison���s Beloved, and her own willed suicide keeps the viewer grounded in a idea with which the Old Mali of Sundiata is fully at ease: that death is preferable to shame. Walter Benjamin had the same idea���with tragic consequences.

June 28, 2021

Time for an agriculture Green New Deal in South Africa

Photo by Megan Thomas on Unsplash

Photo by Megan Thomas on Unsplash Strong farmer lobbies like Agriculture South Africa (AgriSA) have consistently argued over the years that if land is taken from white farmers and handed over to blacks, it could lead to food insecurity in the country. The threat of food insecurity is predicated on incorrect assumptions, for example: that all white-owned farms produce food for the markets (not true); that all transferred land must produce for the markets (not realistic); and that the government has enough time and resources to operate an orderly transfer of land to a group of people who are not just willing but also able to make successful businesses of their land (again, unrealistic).

As poverty levels rise in the COVID-19 era, and tensions grow in rural communities, it is time for an Agriculture Green New Deal (AGND) in South Africa. It is time for a great transformation, one that factors the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of the land question and not just market considerations. Such a transformation would prioritize the right to food, dignity, and degrowth so that people can believe in the national project again. Today, more than ever before, land reform must be given new impetus and treated with greater urgency.

Land is a very emotional subject in South Africa. A lot of it has to do with the colonial land dispossession that began with the arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck in what is now Cape Town in April 1652. However, the bigger damage was caused first by the Native Land Act of 1913, which transferred 87% of the territory���s land to whites, and later by the apartheid-era laws that dispossessed even more blacks and forced them into overcrowded homelands (Bantustans).

When the African National Congress (ANC) came to power in 1994, it identified land reform as a major priority to end 400 years of dispossession and apartheid geography. In 1997, the Department of Land Affairs published the White Paper on South African Land Policy, which developed land reform around three pillars: restitution (to seek redress for person or community dispossessed of property after June 19, 1913 as a result of past racially discriminatory laws or practices); tenure reform (for people or communities whose tenure of land was legally insecure as a result of past racially discriminatory laws or practices; and redistribution (to enable citizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis).

Two other key decisions were made around this time. The ANC government promised to transfer 30% of all arable land to blacks within 15 years. Furthermore, at the behest of the World Bank, it was also decided to acquire land on the principle of ���willing buyer���willing seller��� principle (in other words, on free market terms).

A slew of programs have been developed over the years to actualize the government���s decision of transferring land to blacks, the most important of which are the Settlement and Land Acquisition Grant (launched in 1995), the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (launched in 2001), and the Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy (launched in 2006). Concurrently with these programs, legislation (the Extension of Security of Tenure Act 62 of 1997, the Prevention of Illegal Occupation of Land Act of 1998, etc.) and court processes have helped to advance the restitution and tenure reform agenda.

However, at the time of writing, the government has achieved only 30% of its initial ambition of transferring 30% of agricultural land to blacks by 2015. An undercapitalized program, the willing buyer���willing seller approach means that land reform has advanced at a snail���s pace. Too often also, the government has let the private sector dictate debates about land, and yet, there cannot be any doubt about it: to paraphrase agrarian scholar Sam�� Moyo, land reform is a key component of the agrarian transformation and the agrarian transformation is a key component of the socioeconomic transformation.

Three dimensions of the national question are putting greater urgency on the land question. The first is poverty. The coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated the poverty, inequality, and unemployment crisis in the country. Recent data shows that half the country cannot afford to buy food on a regular basis. The second is the climate crisis. South Africa is a water-stressed country. Paradoxically, it is also the 12th largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world (largely due to its coal power fleet) and the biggest exporter of agriculture commodities on the African continent. The large-scale commercial farms that dominate South African agriculture use up more than 60% of the country���s available water.

Current farming practices, which rely on frequently turning the earth���sometimes twice a year���for sowing purposes means that LSCF constantly release vast amounts of CO2 and methane into the atmosphere. These practices certainly play a role in complicating the drought situation in the country. South Africa only recently emerged from one of the longest droughts in the country���s history. Parts of the country that rely heavily on agriculture, notably the Northern Cape and the Eastern Cape, have not yet recovered from this drought episode and dams there have sunk to their lowest levels ever. At the same time, it is important to note that within the framework of South Africa���s Nationally Determined Contributions to the United Nations��� Framework Convention on Climate Change, the country has to significantly reduce its CO2 emissions. Changing how the farming sector uses water must be a key part of that strategy.

The third is a troubling deterioration of race relations. Every election cycle, skilled populists use land-related talking points to drive a wedge between the races and South Africa to the brink. We saw this following the murder of young farm manager Brendin Horner when skirmishes between blacks and whites almost resulted in a shootout. Similar episodes played out again in the town of Piet Retief in late April 2021 when four white farmers appeared in the magistrate���s court following the murder of two job seekers.

An AGND in South Africa should focus on a number of key priorities. First, redistribution plot sizes should be kept small. In parallel, mix-use housing projects should be rolled out in urban areas to help erase apartheid geography. Land reform projects typically fail for a number of reasons, including the size of the project, a lack of resources, a lack of skills, and a lack of infrastructure. Clear answers have to be developed to address these issues in future projects.

Second, major dams and rain harvesting infrastructure should be developed around the country to provide water to new land owners. Greater investments in smallholder irrigation, including drip irrigation, should also become a priority area for both national and local governments. This infrastructure can go a long way in alleviating the water crisis in many parts of the country. More importantly, it keeps small farmers who practice agroecology and consume most of their harvests within the household in business.

Third, renewable power projects should be set up in rural South Africa to provide power for farm mechanization. This will help create a pool of prosumers (producers/consumers) and ensure that more of the power production revenue goes to rural homes rather than to speculators. The recent amendment to Schedule Two of the Electricity Regulation Act of 2006, authorizing South Africans to produce up to 100MW of electricity without an electricity regulator ( NERSA) license is an important enabler of this objective. In the not-so-distant future, rural farmers shall be able to wheel some of the electricity they produce through the national grid to customers. They shall also be able to generate some extra income by leasing their land to wind and solar energy companies.

This very short essay is by no means a complete blueprint for rolling out land reform in South Africa. Rather, its purpose is to highlight that the number one priority of land reform���beyond justice and equity considerations, of course���should really be about empowering people to own their own land and produce some of their own food, and here, major rural infrastructure within an AGND dynamic can help. The dream of creating a class of black large-scale commercial farms should be subordinated to this priority.

My fellow Africans

Photo by Brad Neathery on Unsplash

Photo by Brad Neathery on Unsplash A few weeks ago on AIAC Talk, we spoke to Anakwa Dwamena and Bhakti Shingrapure about the world of writing and publishing on the African continent. A recurring theme throughout the conversation was how to revive the lively intellectual culture which thrived on the continent during its wave of decolonization.<

But, in romanticizing the past we can sometimes ignore that in the present, there exists a vibrant world of ideas on the continent already, that sometimes, we just aren���t looking closely enough. This is one of the reasons why Africa Is a Country began a fellowship program, the purpose of which is to ���support the production of original work and new knowledge on Africa-related topics that are under-recognized and under-covered in traditional media, new media, and other public forums. It particularly seeks to amplify voices and perspectives from the left that address the major political, social, and economic issues affecting Africans in ways that are original, accessible, and engaging to a variety of audiences.���

In May last year, we awarded ten fellowships and since then have been working with the inaugural class of fellows to support the creation and publication of their original work. This week on AIAC talk, we will profile two fellows and their projects: Youlandree Appasamy, a freelance writer and editor from South Africa, will explore South African Indian class identities, particularly in Kwazulu-Natal province; and Liam Brickhill, a freelance journalist from Zimbabwe, will unearth stories on Zimbabwean cricket.

Another fellow, Ricci Shryock, has previously appeared on AIAC talk to discuss the role of women in Guinea-Bissau���s liberation war.

Last week, we were joined by Grieve Chelwa to remember the life and legacy of Zambia���s founding president Kenneth Kaunda, as well as Herman Wasserman to discuss the rise of media disinformation in Africa. Watch that show on our YouTube channel and stream the next show Tuesday at 6pm in Johannesburg, 7pm Nairobi, and 12pm in New York.

The music industry and vaccine apartheid

Photo by Sam Moqadam on Unsplash

Photo by Sam Moqadam on Unsplash Cabo Verde has one of the highest per capita coronavirus infection rates in Africa. A combination of vaccines from Covax, China, and Hungary��� ���to avoid new waves of migration������has supplied roughly 250,000 doses, enough to immunize about one-fifth of the total population. A better situation than many African countries, but still nowhere near enough for an economy reliant on the outside world.

Two artists from the islands, both acts at our record label, have revealed their frustration at the vaccine divide. One is a member of the diaspora, a European citizen, and has access to a vaccine shortly. The other, a former soldier with FARP, the armed wing of Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau���s independence movement, turned Coladeira guitarist, will have to wait before vaccines reach his small town of S��o Domingos.

While both lament the lack of action by African governments and the inequality of vaccine provision within Cabo Verde itself, Pascoal, the ex-soldier, vents that ���developed countries can acquire the quantities of vaccines they want, wherever they need, and as for poor countries, they can only have the quantities offered to them.��� Tony, of the diaspora, mourns that ���Africa will only be vaccinated when the West is finished��� and believes the music business has a ���moral duty��� to protect all those it employs. Global vaccine equity should be considered as important as the notes on their guitars. But that isn���t the case.

It should strike anyone as curious and shameful that the music industry, especially the so-called ���world music��� industry���now rebranded by the Grammys as ���global music������has not uttered a collective word of protest to the immense vaccine apartheid facing the planet. A tiny minority of rich, primarily Western countries, have hoarded doses exceeding their populations, blocked the ability of the global South, lush with vaccine facilities and brilliant scientific minds, to produce generics via temporary patent waivers at the World Trade Organization, and even disallowed African countries from innovating new vaccines.

A Western-dominated ���world music��� business is often governed, via unresolved historical guilt, by ethical rules written in the metropoles of the global North. Yet these ethics, like the Western liberal ideology that underwrites them, have proven to be what Conor Cruise O���Brien concluded was ���an ingratiating moral mask that a toughly acquisitive society wears��� because we hear of 50-50 profit splits between labels and artists, yet we hear nothing of the 87% to -0.2% split of vaccine coverage between the global North and South.

Vaccine apartheid is at worst a crime against humanity and, at best, monumentally idiotic. Even Western vaccines with their meticulous public relations will be rendered useless by ���mutant variants���, set to emerge relentlessly unless vaccines are widely available. For the music industry, it is also self-defeating. How are your favorite African, Latin American, and Asian acts going to tour European and North American shores, especially with vaccine passports becoming a reality? With pitiful returns from digital streams, tours are paramount for survival and they require vaccine equity. Yet there is no outcry.

The music industry has even been a diligent participant in concealing vaccine apartheid. VaxLive, a fundraising concert by Global Citizen, a corporate public relations group, lavished a stage with international pop���s stars channeling messages of equitable vaccine distribution. Not once did the initiative, its sponsors, or its artists mention the true reason for vaccine apartheid: the imperial monopoly of intellectual property governing life saving pharmaceuticals. All funds raised will go to Covax, a classic conscious-clearing Western charity initiative meant to give crumbs with one hand to hide the greater theft taking place with the other.

Aid concerts for famine-ridden Ethiopia in the 1980s played the same role���a nauseating soundtrack of ethical goodwill that obscured deliberate Western trade and austerity policies that vanquished food sovereignty in large parts of the South. Many surely have strong feelings about vaccine apartheid and abhor its reality, yet the inability to articulate this, the lack of fervor or anger that would inspire action, is the result of three realities that plague the ���world music��� business.

The first is, as mentioned, a faux ethical discourse which serves as a competitive tool to morally outdo competitors, especially those from the South who operate on an entirely different set of ethics not dictated by morality makers in Toronto, London, or Berlin. Consider the African response to the patronizing Band Aid 30 concert by Bob Geldof meant to combat the Ebola crisis.

The second emerges from a systematic erasure of the history and political thought that gave rise to the most powerful music from the global South, now a staple of dance floors worldwide. Never before has so much music, both contemporary and historic, from the South been available to a global audience.

For such a glut of music from former colonies to enter the global imagination but not radically transform the politics of its producers or listeners should be inconceivable. Independence era movements, their worldview, their economics, the role of Western financial power, of debt, of structural adjustment programs, and WTO rulings have vacated the context. All we���re left with are cheap tourist thrills; Black and Brown faces serving warm sounds to frozen climates.

You cannot separate the historic music of, say, the Caribbean from the politics of Aim�� C��saire and Marcus Garvey; of West Africa from the philosophies of Thomas Sankara and Cheikh Anta Diop; of Indonesia from the vision of the Bandung Conference. How could anybody absorb these sounds, revere these artists, even yearn to visit the countries that produced such sophistication without developing a deep empathy for the frustrations, visions, and hopes of these societies? These independence-era politics, and the thinkers behind them, would have preached the crucial necessity of medical sovereignty above all.

This erasure unknowingly follows the apartheid South African game plan. The book Guerilla Radios in Southern Africa reveals that the apartheid regime depoliticized, or sanitized, South African music to ���placate the African��� and dampen the resistance���a curious precursor to the depoliticization of music, particularly hip-hop, by corporate labels, a trend that has disappointingly trickled down to independent outfits.

Some decision makers in music don���t want to ���get political��� because they fear it may alienate their centrist Western market who, they argue, would prefer to have their music served without the murmurs or cries of the colonized. More groovy basslines, less critical canon.

Vaccine apartheid is not a political issue. It is not up for debate. It is not a for or against vote. This is a matter of human decency. There is no apartheid where there are valid arguments on both sides. Believing so is the hallmark of supremacist thinking. A fear to alienate fans and customers at the expense of the lives of the artists and their families could be mistaken for pragmatic neutrality. Neutrality in such instances is rank colonial cowardice.

The third glaring issue is a lack of diversity at the very top of the music business; an enduring whiteness that struggles to find any real attachment to peoples of the South. Few from the gated North can hope to generate a modicum of empathy towards one million dead in India or the fragile health system of Africa���s fourth most populous country, a music powerhouse, stretched to the brink. The same thinking lies behind the shifting news coverage of the pandemic from one of dignified decency when hospitals overflowed in Italy to depraved pandemic porn when tragedy struck India.

It is easy to ignore when you cannot understand, at the very core of your soul, that vaccine apartheid during the worst crisis of our lifetimes, is not only history repeating itself, but also generous rubbing of salt and lime in the festering wounds of a world so thoroughly stereotyped, marginalized, and exoticized that its peoples��� lives do not command enough value to fuel necessary rage.

Music companies, big and small, have giant social media followings that could stir real, vital, tangible public action by inspiring a movement to end the heartlessness of Western rejections of patent waivers for vaccines, therapeutics, and medical technology. Industry leaders in the UK said it themselves when it came to climate change. ���The music industry has the opportunity to lead here,��� said a spokesman for the green movement, completely oblivious to the power the industry would have to challenge vaccine apartheid.

Rallying for climate change is commendable, if the playbook was not obvious to us in the South. It���s no coincidence that environmental and vegan movements in the West arose alongside the growth of African and Asian middle classes. As former colonies began driving more cars, eating more meat, and generally consuming more, still nowhere near Western levels, an entire ethical discourse was devised as yet another ingratiating mask that acted as a competitive marketing tool. As the Western music industry sets environmental standards, how are its counterparts in the South, at a different stage of economic development because of Western rapacity, meant to compete? Making noise about the environment when the most immediate pressing challenge is vaccine apartheid is simply posturing.

Indeed to recognize and speak out against vaccine apartheid would confer equality on the peoples of a global South, overturning a relationship which elevates the producer from the global North to a position of authority and relevance. It would confer a value on Black and�� Brown life, blurring any distinctions that equally elevate and infantilize. A lack of vaccine access only further empowers everyone from the global North. The settler and the native; the journalist and the fixer; the inoculated and the diseased.

A silence is perhaps in the industry���s best long-term interest. Nevermind that many paraded #BlackLivesMatter only for indifference to set in when nearly one billion Black African lives are at stake.

Perhaps vaccine apartheid, like passport apartheid, will only be recognized when Westerners realize that their summer concerts and autumn festivals will not feature so many of the Black and Brown artists they love. Record labels wrote their representatives only when tours and concerts were threatened, coming to the laughably belated realization of the inequity of citizenship. A similar approach might arise when the entitlement of Western leisure is once again under threat.

Elements of the same intellectual property regime that govern the monopoly rights to life- saving pharmaceuticals also govern contracts in the music industry. They also govern the rights of film, which is why Hollywood rallied behind the pharmaceutical industry. A temporary patent waiver would not threaten lucrative deals in any entertainment business. We���re told that the altar of intellectual property, codified at the WTO to impose on the world the dominant IP regimes of the US and Europe, is at stake for many of the world���s most powerful industries. The fear is absurd and irrelevant. Intellectual property in music does not determine the life and death of hundreds of millions and the future of normalcy.

Music is not the only global business that relies on Southern talent shamefully silent about vaccine apartheid. Football underwent a convulsion during a proposal that would have permanently deformed the world���s most beloved sport. Fans marched in the streets and some of the most powerful institutions, like J.P. Morgan, not only buckled, but apologized. If such energy attacked vaccine apartheid, patents would be waived tomorrow and Pfizer���s CEO would be forced to make a statement. The music industry can make this happen.

There has never been a time in history when the music business has worked so closely with artists in Africa and Asia. African music in particular has a larger global audience than ever before. More artists are drawing from Africa, more labels are signing African artists, and more music interest is focused on the global South, whose sounds are finally challenging the humdrum of mainstream Western pop in the global imagination.

For the music business to remain obtuse, willfully silent, or even unwilling to participate, one can only recall the memorable frustration of iconic Ivorian footballer Didier Drogba (whose country via Covax received only 500,000 vaccines, enough for two percent of its people): ���It���s a fucking disgrace!���

Nobody gets to profess any sort of love for Black and Brown music or project any ethical narrative without having the common decency to fight for Black and Brown life. Perhaps future albums should come with a new warning sign: ���Remained silent about vaccine apartheid during the COVID-19 pandemic.���

Music���s ingratiating moral mask has withered, revealing a disfigured face whose true ethical philosophy is, as Lauryn Hill once noted, ���paper thin.���

June 24, 2021

When the war is over

Photo by Rachel Martin on Unsplash.

Photo by Rachel Martin on Unsplash. Mahmood Mamdani���s work is always provocative and sparks debate. In August 2017, I watched with some glee as Mamdani told an audience at the University of Cape Town (UCT) that ���it is no exaggeration to say that Afrikaans represents the most successful decolonizing initiative on the African continent,��� and that the language was in large part the product of a vast affirmative action program. Mamdani���s point was to explain why no postcolonial government elsewhere on the continent had elevated indigenous languages to languages of science or humanities, beyond what he described as ���folkloric.��� So I expected that Mamdani���s new book would at least get us talking.

I first encountered Mamdani���s work as a graduate student completing a master���s degree in political science at Northwestern University in 1995. (I have one clear memory of him speaking about Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, upstairs at the famed Red Lion Pub; the owner���s mother had been an African Studies scholar.) By the time I returned to South Africa one year later, Mamdani had been appointed as director of UCT���s Center for African Studies (CAS). What happened there is now well known���just search for ���the Mamdani affair,��� the name given to his clash with the university over its core curriculum. Mamdani had proposed a new curriculum that challenged the university and South Africa���s relationship to the rest of the continent. At the time, African Studies essentially meant studying black South Africans. (At one point, Mamdani referred to CAS as the ���new home for Bantu education.���) Mamdani eventually left UCT to take up a tenure track position at Columbia University in 1999, but while he was still at UCT, he gave an inaugural lecture organized around this question: ���When does a settler become a native?��� And as he writes in his new book, Neither Settler Nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities, his answer was the same then as it is now: never.

Mamdani has been returning to this question of political belonging repeatedly in his books covering South Africa, Rwanda, and Darfur (he is quite prolific; he seems to write a new book every 3 to 4 years). In his latest book, he expands the canvas to include the United States and Israel. He also returns to his earlier focus on Sudan and South Africa.

By way of summary, Mamdani���s book makes three main contributions. One is the obvious contribution to revisionist political history: Mamdani makes settler colonialism and the story of native peoples in the United States central to any understanding of the country in a way that few similarly synthetic accounts do. He identifies the US as the first settler colonial state (which many US scholars still fail to do) and highlights the colonial status of native people in the United States: they are still stuck outside the polity, reduced to bantustan status in their ���reservations.���

Since the book���s publication, a number of prominent Native American scholars, most notably Dina Gilio-Whitaker (author of As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock) and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (author of An Indigenous Peoples��� History of the United States), have pointed to the importance of Mamdani���s contribution in this regard.

Mamdani also offers insights into the study of comparative politics. Here, I am referring to his taking up the challenge of making the connections between the US, Germany, South Africa, and Israel obvious, a comparison in which he uses the US���usually the exceptional state���as the norm. This presentation of the world from a non-Western-centric perspective���in a discussion of the US, no less���is even more impressive given that Mamdani is a Third World scholar (or, as some prefer, a scholar from the Global South).

But the book���s overarching contribution is how he brings South Africa back into the discussion. For Mamdani, South Africa represents an interesting starting point for imagining ideas about the nation other than permanent majorities and minorities. And here it is important to note that Mamdani is not saying that postapartheid South Africa is a utopia (in fact, he spends some time engaging with that criticism of this aspect of his argument), but rather that it points to the terms of a viable political future. South Africa is not perfect, but it prevented one civil war in 1994 and���for all its problems since���it is not currently in danger of falling into another.

Mamdani���s framework of ���the lessons from South Africa��� for Israel is especially useful. I say this partly because South Africa dominates my own scholarship and it is a country in which I have a personal stake, but also because I think he is right about South Africa���s potential for imagining ideas about the nation beyond those of permanent majorities and minorities.

And this is also where I think Mamdani���s work challenges us.

The first challenge Mamdani offers relates to his notion of survivors. Mamdani proposes that all victims, perpetrators, beneficiaries, bystanders, and exiles be included in an expanded political process; here, Mamdani refers to the usefulness of constitutional negotiations and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in South Africa. This goes against much of the contemporary debate in South Africa, in which the TRC is just reduced to a ���betrayal��� or ���sellout.��� Mamdani is also not enthusiastic about the use of criminal prosecutions (the Nuremberg option) as a way out of cycles of violence.

Mamdani is right that during and since the negotiations to end apartheid rule, the idea that South Africa belonged to ���those who already lived in it��� was the one issue on which the white minority and the liberation movements already agreed. In the view of both parties, the struggle against apartheid was contested by South African nationals, and the nation to come belonged to those who had declared it for themselves during that struggle. This was the case whether they were victims, perpetrators, beneficiaries, bystanders, or exiles.

So it follows, then, that what binds black and white South Africans together is a kinship based on their shared experience of colonialism and apartheid. But here���s the catch: that kinship doesn���t extend beyond the nation-state���s borders or to any new arrivals. It manifests as xenophobia toward these new arrivals, especially Africans from elsewhere on the continent. As South African writer Sisonke Msimang, writing on this site, has put it so well: For South Africans, ���foreigners [in South Africa] are foreign precisely because they cannot understand the pain of apartheid, because most South Africans now claim to have been victims of the system. Whether white or black, the trauma of living through apartheid is seen as such a defining experience that it becomes exclusionary; it has made a nation of us.��� (Moreover, that tag of ���foreigner��� in South Africa is applied exclusively to black migrants from elsewhere on the African continent. Increasingly, South Asian migrants���Bangladeshi or Pakistani traders who have opened informal stores, spazas, in black townships in the last fifteen years or so���have been added to the mix.)

So if Mamdani���s book leaves us with a challenge, it is how to move to an understanding of South Africa that extends beyond the nation-state. For me, this involves treating colonialism, apartheid, and capitalism in South Africa as transnational phenomena. Capitalism in South Africa was always a multinational affair; South Africa was never exceptional, it was also part of a regional capitalism that started with slavery and moved through mining capital, industry, and agriculture. These industries are all built on multinational workforces. At times, even apartheid had to come to terms with this. In the late 1980s, apartheid South Africa had no choice but to extend resident status and even citizenship to those workers from Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Namibia, and Zambia who had worked its mines and industry, thus confirming the multinational nature of local capitalism. It is also no revelation that workers from elsewhere Southern Africa were equally at the heart of the three major strikes of the twentieth century in South Africa���the strikes of 1946, 1973, and 1987���that played a significant role in ending apartheid.

Similarly, resistance to apartheid involved the whole region. The African National Congress (ANC) and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) camped out in Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Botswana, and Angola. Countries on South Africa���s border paid the price for its support of the liberation struggle; think of the brutal attacks by the South African military on Mozambique, Botswana, and Lesotho. Namibia was basically a South African colony, and the apartheid army occupied parts of southern Angola for long stretches. South African writer William Shoki puts it bluntly: ���There are no truly indigenous South Africans; there conceptually cannot be any. What we now call the nation-state of South Africa is a modern invention that has always been a land of foreigners.���

But it is perhaps Mamdani���s rereading of the 1970s in South Africa that stands out the most to me. Here, his argument is that anti-apartheid resistance took a creative turn in the 1970s: that period was the first time that resistance did not reproduce the architects of apartheid inside the resistance itself. Before that, resistance to apartheid and racial capitalism was organized through separate organizations for different racial groups: the ANC for Africans, the Indian Congress for Indians, the Coloured People���s Congress and the white Congress of Democrats, and so on. (Not to belabor the point, but it is not much talked about these days that the ANC maintained these racial lines in its own organization into the mid-1980s. For example, only in 1985 did the ANC open its national executive committee to people of all ���races��� other from ���Africans.���)

Mamdani���s argument is that the key initiative came from the student movement. Black students broke from the white student movement and went to reorganize themselves collectively as the Black Consciousness Movement, reinventing blackness as a political identity that was dynamic, contingent, and rooted in material conditions. They also revitalized township protests, which had gone dormant after the state clamped down on internal resistance by the mid-1960s and forced the major liberation movements into exile. Radical white students broke with the white National Union of Students and went to organize workers to develop transhistorical identities subject to struggle. We can then read what followed���the 1976 student uprising, the broad left politics of the 1980s of the United Democratic Front, and the Congress of South African Trade Unions with its alternative media, its theater groups and its sports associations���as the formation of new identities based on shared struggles. Mamdani may overstate the ontological break of the early 1970s, but his point holds. (By the way, some critics may take Mamdani to task for treating the UDF in two paragraphs, but, as he has during one of the launch events for the book, he had to leave some things out.) That popular energy of Black Consciousness, the 1973 strikes and later the UDF, the unions, and the student movement, would all eventually cede leadership of the struggle (and with it leadership during formal negotiations with the apartheid government) in pursuit of reimagining the basis of postapartheid South Africa. But it can���t be denied that they contributed considerably to rethinking the idea of political community.

While the ANC, like most postcolonial states and ruling parties, has tried to corral these energies (when the ANC was unbanned, it stood at the lead of negotiations with the apartheid state and demobilized the UDF), it hasn���t been entirely successful. The sporadic upheavals, organizing, and mass protests evidenced by the social movements of the early 2000s (the AIDS treatment movement, the various anti-privatization movements, shack dwellers, and others) and, more recently, Fees Must Fall and Rhodes Must Fall from 2015 to 2017, suggest that some of that tradition is still alive. What���s interesting about all of these new social movements and student uprisings are that they���re all concerned with crafting new political subjectivities and doing so from below.

It is here that I think Mamdani is onto something, and we should think about ways to describe it in more dynamic terms.

What continues to fascinate me about South Africa is how resistance plays out. For me, what is promising is the way that South Africa and South Africans reinvent the political community through struggle. And struggle is crucial for this because it is an education in exercising control over your life and having the power to remake your world. Genuine self-determination is a revelation, not just what���s promised as an empty abstract ideal by most nationalisms.

To consider how this happens beyond state forms and legal structures would bring in questions of mass movements, of culture, of popular culture, and it would expand the terrain on which the forms of solidarity that Mamdani describes���or wishes for���can become possible.

Earlier this year, we saw nascent signs of this new kind of politics again. Young people across university campuses in South Africa revived the protests of Fees Must Fall (and, by extension, of the ���education crisis committees��� of the 1980s, the Soweto uprising, and Black Consciousness) to demand that all eligible students���even those with historical debt owed to the university���are allowed to enroll. The protests are over for now. Police intimidation and repression were a big part of their dissolution. At one demonstration outside Wits University in Johannesburg, one person was shot and killed by the police.

What is striking, however, was how a prominent slogan of the protests was ���Asinamali,��� which in isiZulu means, ���We have no money.��� This slogan plays a starring role in Mamdani���s account of the epistemic break of the 1970s. Students were central to the movements of the 1970s just like they are now.

The protests failed of course, but as Shoki argued at the time about these kinds of pop-up protests: by adopting this symbol, ���the protesters demonstrate their potential to not only address the barriers to entry of the increasingly commodified university, but the barriers to living in an increasingly commodified world.��� And as Shoki adds, many have called the first #FeesMustFall protests from 2015 to 2017 the most serious challenge to the postapartheid political order while also pointing out that their vital limitation ���was an inability to connect to broader working-class struggles.��� But those links may still be forged again in a way that wasn���t there before. For Mamdani, the question of belonging is not who is a settler or who is a native. Instead, he suggests that rather than imagined, the political community ought to be a concrete one of our own making. The South African story at least gets us some of the way there. What South Africans, and others, can learn from Mamdani���s book is that only through collective action can the nation-building project be restarted or put back on a more fulfilling path.

June 23, 2021

Africa���s lost psychiatrists

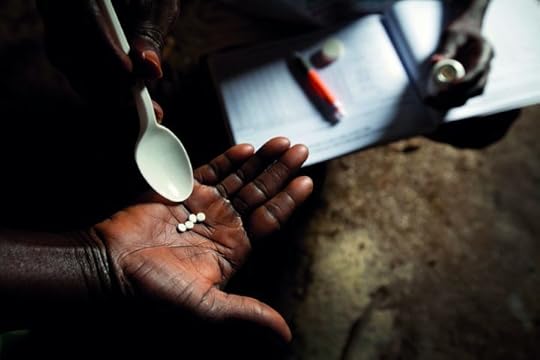

Photo credit Kate Holt/Sightsavers. This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

Photo credit Kate Holt/Sightsavers. This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford). The brain drain of medical professionals from African countries to rich countries in Europe, North America, and the Middle East has been particularly pronounced since the 1980s. As Bibilola Oladeji and Oye Gureje have noted, as of 2011, there were more than 17,000 African physicians practicing in the US alone, over two-thirds of whom had been trained in African medical schools. Of this group, two-thirds were trained either in Nigeria or South Africa, the two countries with the most extensive medical training systems on the continent. Psychiatrists have also made up a significant piece of the larger medical migration, drawn by higher salaries, better facilities, opportunities for professional development, and prospects for long-term stability to seek jobs outside of the continent.

The brain drain has become a commonplace terminology to describe the emigration of highly skilled labor from developing countries to highly industrialized states in the post-colonial world. The concept has been particularly valuable for understanding persistent underdevelopment in sub-Saharan African countries as related not so much to deficiencies in African expertise as its redirection primarily for the benefit of wealthy countries. Similar to the ���brawn drain��� of the Atlantic slave trade or the natural resource depletion that characterized European colonialism in much of the continent, brain drain has had long-lasting impacts on African countries��� internal development and position in the global economy.

The impact of the brain drain on mental health care in Africa can be seen through the example of Nigeria, one of the few sub-Saharan African countries with university hospitals providing accredited medical training in psychiatry. Nigeria���s first trained psychiatrist of indigenous background was Thomas Adeoye Lambo, who studied at Birmingham and the Maudsley Hospital in the UK before returning to Nigeria to practice at the newly founded Aro Mental Hospital in 1954. Lambo and his acolyte, Tolani Asuni, developed much of the infrastructure of Nigerian psychiatry in the 1960s and 1970s, and several Nigerian universities began producing psychiatrists by the 1980s. The purpose of developing such programs was to produce a qualified mental health workforce for the country. Students from other countries in West Africa also trained in psychiatry at Nigerian institutions. Nigeria���s mental health care workforce grew slowly but surely from only three psychiatrists in 1955, to 25 by 1975, and 100 by 2001. But the brain drain has had a major impact on Nigerian psychiatry. Today, there are roughly 250 psychiatrists in Nigeria to serve a population of approximately 190 million. At the same time, a study from 2010 found that there were 384 Nigerian psychiatrists practicing in the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand, a number 50% higher than the estimated total practicing in Nigeria.

The effects of this psychiatric brain drain have been significant. Beyond the worsening of the psychiatrist-to-population ratio, this phenomenon has the potential of severely weakening ongoing reproduction of this limited resource as more freshly qualified psychiatrists and senior residents are being enticed/encouraged to relocate on the guise of training opportunities abroad, from which they never return. In addition to psychiatrists, mental health nurses are also leaving the continent in droves, with packages designed to make emigration easy and more likely to be permanent. The rate of migration far outstrips the rate of production, leaving a huge deficit in human resources, one of the major pillars of a health system, according to the World Health Organization.

Several reasons have been proffered for the exodus of medical doctors from Africa to the economically developed world. Oberoi and Lin classified these reasons into endogenous and exogenous factors. Endogenous factors include poor working conditions, poor remuneration, and lack of job satisfaction and job security with little or no opportunities for career development. Exogenous factors include social pressures from relatives, preponderances of civil unrest, and armed conflicts with attendant high levels of insecurity. Ironically, the factors that push mental health care workers to relocate abroad are the same ones that likely contribute to rates of psychological distress in their communities of origin that, in turn, require more and better mental health care.

Since the late 2000s, the ���global mental health��� movement has sought to ameliorate this ���treatment gap��� in mental health services in developing countries, including Nigeria and others in sub-Saharan Africa. In most cases, reducing the treatment gap relies heavily on training lower-qualified workers to perform the duties of highly-skilled practitioners, a set of practices known as ���task shifting.��� Task shifting in international public health has existed for a long time, and has been employed extensively in the field of HIV/AIDS diagnosis and treatment in many environments. But it���s use in psychiatric care is somewhat more controversial. Most notably, global mental health has been critiqued as potentially socially and culturally insensitive, importing knowledge and practices from western industrialized countries that might not adequately reflect local cultural beliefs or social determinants of health, while simultaneously marginalizing indigenous health systems.

Task shifting has also been proposed as a strategy for alleviating the effects of the brain drain on the health care sector. In a review of policies to address brain drain in sub-Saharan African countries, Edward Zimbudzi has identified some areas of possible intervention. These include ethical recruitment, brain drain tax or compensation for source countries, increasing investment in training more professionals, improving remuneration of health workers and working conditions in general, importing more staff, ensuring political stability, and encouraging remittances. However, the review concluded ���that there is considerable consensus on task shifting as the most appropriate and sustainable policy option for reducing the impact of health professional brain drain from Africa.��� While some studies have concluded that task shifting has effectively filled the treatment gap, others have indicated that it is by no means a comparable substitute for professional mental health care due to lack of proper supervision and training of lower level workers, among other factors.

But we would like to offer a different critique of the task-shifting discourse: it���s tendency to normalize the brain drain of health care professionals. Global mental health has always emphasized practicality over ideology: anything that can be done to fill the ���treatment gap��� is presumably better than not doing it. The origins of the medical brain drain are not really global mental health���s concern, but its consequences are a large part of the foundation of the movement���s argument for ���scaling up��� the health care workforce to address the ���treatment gap,��� which is effectively the primary justification for the movement���s existence. However, in making the case for immediate action, the discourse on task-shifting in global mental health replicates the long history of ignoring the long-term exploitation of African resources in order to focus on short-term, externally funded, non-state interventions to provide what Africa supposedly ���lacks.���

Promoting task shifting to lower cadre health care workers as the best way to scale up mental health services in low- and middle-income countries indirectly suggests that these countries cannot hope for better, even as billions of dollars are lost by African countries from investment in training highly qualified health workers who go on to treat patients in wealthy countries. Meanwhile wealthy countries acquiesce to helping train up less-qualified caregivers to fill the ���treatment gap��� created in part by this brain drain. It also implies that African countries can get by on less than wealthy countries. Indeed, severe mental illness continues to be neglected under the ���task shifting��� model that does little to increase specialist capacity to handle such cases. While this rather popular principle in global mental health appears practical, it inadvertently panders to the notion that some lives are more important than others, and calls to question the relative value placed on the health and lives of citizens of the developing countries of Africa compared to the developed world. It reinforces and normalizes global inequalities.

Mitigating the psychiatric brain drain must ultimately be about much more than filling ���treatment gaps.��� It must also be about addressing the geopolitical and macroeconomic conditions that have produced the gap in the first place. Developing equitable and sustainable�� mental health services for all Africans is a political, economic, moral, and ethical issue of contemporary urgency and historical significance.

June 22, 2021

Unmasking Nigerian elites

Still from film.

Still from film. After months of being teased with clips and titillating pictures of Nollywood���s first neo-noir film on social media, we finally get to see one of the most anticipated films of 2020.

With a good number of Nollywood films subverting public gathering restrictions brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic through different Netflix acquisition deals, it was expected that��La Femme Anjola��would take that route. But that didn���t happen, at least, not yet.

The film highlights a common phenomenon in Nigeria: a lot of businesses that appear legal are fronts for money laundering and drug trafficking. In Nigeria, crime is often associated with the poor, and so many live in gated estates and communities to keep them at a distance. But our characters with their proper English and fine cars and expensive clothes are caught up in this muddy world of crime. The movie unmasks the Nigerian elite���no one is exactly what they seem.

La Femme Anjola��concerns a young stockbroker, Dejare Johnson (Nonso Bassey), who has it all going for him: engaged to a beautiful woman, a happy close-knit family, a great job, a good home, a fine car. But he is bored. He���s passionate about music and is a skilled saxophonist. In pursuit of this passion, he joins a band at a local bar and crosses paths with the beautiful and conceited Anjola Kalu (Rita Dominic), wife of a wealthy gangster and vocalist for the band. They have a minor altercation at their first meeting, and a fellow band member warns him about her, but he rebuffs, ���I work with sharks all day.��� He is not merely asserting that he is not intimidated by her arrogance. As a stockbroker, Dejare is confident, takes successful investment risks, much to the envy of his colleagues. But he isn���t quite prepared for Anjola. His life is upturned the moment he meets her. Their story pirouettes to a love affair. There���s sex. Pillow talk. Heartbreak and betrayal. And there���s also murder.

The movie takes the form of the 1944 Hollywood noir film, Billy Wilder���s Double Indemnity. Both films are told through flashbacks and aided by a voice-over from the protagonists. Where Dejare is an investment banker, Walter Neff of Double Indemnity was an insurance salesman. They are also weak, unassuming men who slip into criminality for the women they are infatuated with. Needless to say, both Anjola and Phyllis Dietrichson are femme fatales. The films also share a clever crime in common. Mildred Okwo draws influences from the classic noir film and delivers neo-noir, but in an African setting.

The referencing also reveals the filmmaker’s ambitious and deliberate efforts to pay homage to Double Indemnity and other noir films of the 1940s and 1950s. It goes to show how far the industry has come. The last time Nollywood reminded us of Double Indemnity was in 2009 with Frank Rajah Arase���s��Shakira (Face of Deceit), but this was a bad imitation, complete with dialogue rip-offs.

Acclaimed screenwriter Tunde Babalola and director Okwo collaborate on this. Their last collaboration was in 2011���the classic comedy��The Meeting���which��satirized corruption in Nigeria���s public service.��La Femme Anjola��takes a jab is at the rogue Nigerian police.

La Femme Anjola��is rich with brilliant performances, especially from its male lead, Bassey, who is excellent in his first major film role. He has an emotional range that lets him go from confident to timid, from vulnerable to angry in situations that call for their expression, employing intensity and nuance in right proportions. He also shares great chemistry with love interests Anjola and Thabisa (Mumbi Maina).

Also striking is the film���s cinematography. Mildred Okwo works with Jonathan Kovel who had been put to good use in the brilliant South African noir, Jahmil T Qubeka���s 2012��Of Good Report,��shot in monochrome. Lagos, however, is too vibrant and chaotic for black and white, and so we get colors but saturated with dark hue. Unlike standard Nollywood, in this film, Lagos is not just fine bridges and Lekki mansions, and neither is the grittiness of the city���s slums romanticized in an attempt to be different. Kovel captures the duality of the city. Lagos is complex, it is an embodiment of these different ends of the spectrum, metaphorical for the characters found in her. If La Femme Anjola��says anything about Lagosians and humans in general, it is that no one is either good or bad, just humans in pursuit of different desires.

Take the character inspector Danladi (Paul Adams) for instance. A skilled policeman who uncomplicates the maze of crime surrounding the murder in the film. When he catches his culprit, rather than apprehend him, he demands a settlement instead. It’s easy to dismiss the policeman as being corrupt just like his cohorts in traffic who harass and extort drivers and passengers alike. But a closer look reveals that he’s a victim of the Nigerian situation. After years of dedication to the Nigerian force he has barely anything to show for it. For retirement, he’s sure to be doomed to an irregular monthly stipend as pension. This is the reality of many Nigerian police officers, and echoes the events of the #EndSARS protests in October of 2020. While rallying for the disbandment of the rogue SARS (for Special Anti-Robbery Squad) unit and an end to police brutality, Nigerians had tabled a five-point demand to the government that included better pay and compensation for the police, acknowledging the poor conditions under which police render duty that pushes them to corruption.

The slow-burn thriller is still showing in some cinemas in Nigeria, underappreciated by cinemagoers too used to ensemble comedies. But, La Femme Anjola is one of the most intriguing and brilliant pieces of cinema to come out of Nollywood and serves as a beacon of hope and nudge to filmmakers who wish to explore stories and genres beyond the staple slapstick comedy and melodrama.

The academic game

On the scale of things that young academics cannot avoid, the circus of peer-reviewed publications, impact factors, and curricula boosting surely scores high. The goal, young academics are told, is to get articles out and place them in outlets considered prestigious, ���leading in their field.���

Indexed academic journals, the scholarly reviews usually published quarterly, are hard currency in the business, followed by monographs and university press book chapters. While it���s no big secret that the market is an unhealthy oligopoly of some six dominant conglomerates (Taylor and Francis, Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, Springer, Routledge, and Elsevier), little collective action exists to reverse or stop this trend, whether through collective boycott or by finding viable alternatives.

Worse, even progressive universities and professors tell their graduate students that while the publishing market is uneven, unhealthy, and unfair, there is no other path to be competitive for one of the rare permanent university jobs. So far, so good. A social scientist myself, I find solace in a mix of Mancur Olson���s collective action problem and Gramscian theories of hegemony to guide my cynical, but ultimately powerless, reflection as I look at the perverse ramifications of a system I despise.

Yet, there is more, as I learned in a recent publishing experience. Having published in journals before, I���ve been lucky in navigating the obstacles of peer review. Yet, this recent paper taught me new lessons on privilege and position. As I shared on Twitter a few months ago, the piece I submitted came out of my PhD���and while some of my supervisors liked it a lot, it was rejected by two journals before it was published. The truth is, being published is no infallible judgment of quality. I have managed to get poor research published and been rejected for good research. The quality of editors and reviewers is as variable as that of our manuscripts.

So I pitched a journal considered top-notch ���in my field.��� One spot-on reviewer offered critical but useful feedback, and a second one less so. The journal���s editors pushed me to improve, providing extremely detailed comments. After two rounds of revisions, I was told that though my draft sat on the edge of being published, they were unable to accept it. Still, I was thankful for the learning process.

I reworked the paper and submitted it to another journal, less prestigious but considered high quality. After a long wait, I received lukewarm reviews. I resubmitted, and, having done so, I waited eight months. When I asked for updates, I got a rejection, with no explanation except that ���it wasn���t in the scope of the journal��� (though, curiously, it initially had been). I was puzzled, but given the lousy performance by reviewers and editors, I thought it was for the best. Bear in mind: while some journals have fantastic teams, others excel by arrogance.

Again, I redrafted and then submitted to a journal that inspires me both scientifically and politically. After revisions, editors accepted the paper. Yet, reviewer two had���in broken English���complained that my English wasn���t great. This is another recurrent issue in academic publishing: English dominates, with both good (common ground and global conversation) and less good (exclusion of non-native speakers) consequences. I told the editors that I was on a precarious contract with no funding to pay for professional editing. To my surprise, they expressed understanding and offered help in editing so that the paper could be published.

Now, what if my experience is just a sneak preview of what others experience regularly? I���m neither a rich kid nor trained in Ivy League or fancy UK universities. Hence, I don���t have the pedigree instilled by institutions with a centuries-old sense of self-bravado and a carefully crafted image of superiority. However, I am a white male who studied in a few European universities, where I learned how to play the game of pretense that dominates our business. How much worse might it be for thousands of students and researchers with different lives, backgrounds, and histories?

Academic postings and publications are a vertical affair. Sterile curricula and the right networks get you somewhere, research quality often not that much. Journals pride themselves on fostering merit-based processes by doing ���blind peer review.��� However, what if all that���s blind is the reckoning with inherent systemic discrimination?

Most of the time, as we review manuscripts, we have an idea about the authors who wrote them, because the work tends to be in our respective narrow fields. When we read drafts, we easily recognize degrees of style and elegance, influencing our judgments ���even to the point of using broken English to bash good research because it does not measure up to our Shakespearean ideals and elite Eton jargons. How might this affect a young researcher from Francophone Africa submitting to a top Oxford-edited journal? What assurance does peer review provide to judge research presented in less assertive or less arrogant ways, as research tells us women���s writing often is? What does it offer when formatting and other formal requirements are not so flawless, whether it is because an author at an underfunded Global South university has no means to access editing services or because that person is less acquainted with the invisible codes of belonging to the scientific elites? These questions only scrape the surface of a long discussion.

Academic publishing is a stressful process to many, and there is an unhealthy balance between a peer-review process that is only in theory fair, anonymous, and non-discriminatory, and the constant pressure to publish. We should all question and critique these dynamics more publicly and openly. Being published is but one of many criteria to judge the quality of your research. It is often more a result of luck than academic skill. Young researchers not ticking all the boxes of privilege should never forget this as they write.

June 21, 2021

Story maps of no location

Julie Mehretu, "Stadia II," 2004.

Julie Mehretu, "Stadia II," 2004. In the wake of the so-called Arab Spring, Julie Mehretu began a year-long project, a series of large-scale paintings titled Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) (2012). The title references the imposing modernist government building often mis-ascribed to the Soviet-influenced Nasserist era but actually constructed by 1949, prior to Nasser���s reign. Sitting on the edge of Tahrir Square, the building has come to represent the overbearing bureaucracy that crushes Egyptians under its enormous weight. Similarly, Mehretu���s four vertical canvases engulf the viewer within their distorted, shifting perspectives; the architectural drawing in the top half of each painting is upside down, creating a mirroring effect with the bottom part. This foundational architectural layer incorporates details from similar sites of resistance and revolution. However, rather than approaching these spaces as stages, Mehretu treats them as ���containers��� created by the layers of overlapping histories, their narratives disrupted by the outbreaks of ink markings and gestures that explode across the canvas. Tahrir Square���an unplanned public space, ���the accumulation of leftover spaces,��� surrounded by buildings that capture different moments in Egypt���s history���embodies the kind of archeological unearthing that the artist has been undertaking for almost three decades.

Mehretu���s mid-career survey is breathtaking and immersive. Following a year of confinement marked by the smallness of life, the work feels monumental, not only in scale but in the expanse and scope of its vision and the world it imagines. Multilayered and multi-referential, her paintings and works on paper engage with questions of power, surveillance, migration, war, displacement, climate change, and globalization, capturing both possibility and pain, hope and shattered dreams. By drawing on an extensive range of references, Mehretu collapses geographical and historical demarcations in works that feel at once urgent and timely but also ancient and epic. During a career committed to abstract painting, Mehretu has challenged assumptions about the continued relevance and political significance of the approach. As an Ethiopian-American woman, she defies expectations that artists of color should produce representational work, a practice whose dismissal is often justified by its ���absence��� from ���traditional��� non-western art. Instead, she renders the (figuration/abstraction) binary superfluous.

Following her graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design in the mid-1990s, Mehretu began developing an intricate and complex lexicon, wielding a wide-ranging vocabulary of influences. In early works such as Time Analysis of Character Behavior (1997) and Conflict Location Index (1997), the artist conducts meticulous studies���almost scientific dissections���of her experimental system of gestures, markings, and symbols. Using graphs and charts, she plots the movement and behavior of these characters, each independent and complete with its own path in a carefully choreographed dance.

In the early 2000s, Mehretu���s practice shifted as her concerns became more global. Her interest in cartography expanded to include maps, blueprints, and architectural plans in the layered landscape her earlier characters come to inhabit. Transcending: The New International (2003) fuses maps of Addis Ababa with those of other African capitals. In using aerial plans of indigenous, modernist, and internationalist architectural styles, the artist plays with perspective so as to merge these systems and collapse historical trajectories. Born in the Ethiopian capital in 1970, Mehretu has often talked about the influence of her early childhood during the moment of pan-African possibility that preceded the civil war (1974���1990). Transcending captures the failed promises of African decolonial projects and the subsequent cooptation of these dreams while also acknowledging the hope they once offered.