Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 126

June 7, 2021

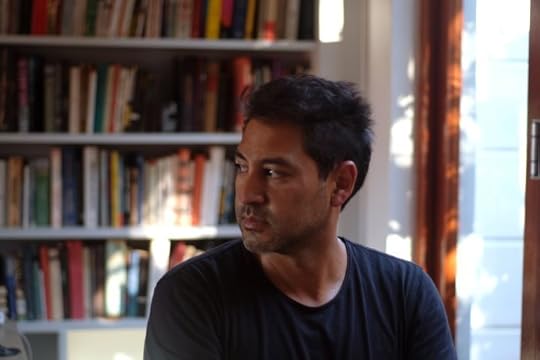

Where do just ideas come from?

Photo: Francesca Noemi Marconi, via Unsplash.

Photo: Francesca Noemi Marconi, via Unsplash. Now treated as a prescient representation of the 1968 generation that forever transformed left-wing politics, Jean-Luc Godard���s 1967 film La Chinoise portrays a group of French students forming a Maoist collective and living together in a cosy Parisian apartment where fierce discussions over politics and revolutionary strategy happen with religious devotion. On the only occasion an outsider enters the secret enclave, it���s to deliver a seminar on the ���Prospects for the European Left.��� The gentleman, introduced only as Omar, is also the film���s only black character. In the seminar���s Q&A, one of the French students asks if a non-socialist revolution can peacefully be changed into a socialist one. In answering the question (���Yes, but under specific conditions���), Omar claims it is based on a false, underlying notion, and asks back: ���Where do just ideas arise? Where do just ideas come from?���

Of course, we know that this man is the only true revolutionary in the film because Omar Blondin Diop was a revolutionary in real life. His appearance in the film counts as the only record of him speaking available, and part of a handful of visuals in general. Blondin Diop never had much of a chance to fully announce himself to the world ��� at 26 years old, he suspiciously died in Senegalese detention in May 1973, 14 months into a three-year sentence handed to him by L��opold Sedar Senghor���s regime. Senghor is equally thought of as a revolutionary, and a significant intellectual for theorizing N��gritude. But why would one revolutionary be an existential threat to another?

Writing of the ���Senghor myth���, AIAC contributor Florian Bobin notes that ���Once you���ve exhausted all the Negritude quotes, you have to confront the fact that Leopold Sedar Senghor ran Senegal as a repressive, one-party state.��� Senghor was the quintessential philosopher-king, and as Bobin further observes, ���Under the single-party rule of Senghor���s Senegalese Progressive Union (UPS), authorities resorted to brutal methods; intimidating, arresting, imprisoning, torturing and��killing dissidents.��� A prime example was when Senghor accused Mamadou Dia, the president of Senegal���s Council of Ministers, of attempting to stage a coup against him. Dia had long been advocating for decentralizing power and vesting it in the hands of peasant communities. Despite being a fighter, moving to wage a military campaign against Senghor���s regime, Blondin Diop was thinking against him too. In his segment in La Chinoise, Blondin Diop (who at 21, was already a student-professor) answers the question he puts to the group by affirming democracy, political and economic. Just ideas come from social interaction, from the fight to produce, and scientific research, but above all, ���From the class struggle. Some classes are victorious, others are defeated. That���s history. The history of all civilizations.��� Who is victorious in Senegal?

In this AIAC Talk then, we want to investigate Senegal���s post-colonial history, especially to grapple with it in the context of Senegal���s ongoing civil unrest against incumbent president Macky Sall. This will not be the first time a popular uprising has emerged in Senegal���s recent history to resist creeping authoritarianism. On June 23, 2011, the Senegalese people mobilized to challenge former president Abdoulaye Wade���s attempt to change the constitution to permit him to run for a third term and to win elections by securing less of the vote. The moment produced the M23, a broad movement for democratization in Senegal, as well as groupings like ���Y’En A Marre��� ; which means ���Fed up��� and is a collective of mostly rappers and youth disgruntled with Senegal���s political and economic stagnation. What have become of these movements in the 10 years since their inception? How do we make sense of the fact that, this time round, dissident energy is rallied behind Ousmane Sonko, the opposition leader whose arrest following accusations of rape are what precipitated the current crisis?��

We are joined by Florian�� and Marame Gueye to help us make sense of all of this. Florian Bobin is a student in African history and host of Elimu Podcast. His research focuses on post-colonial liberation struggles and state violence from the 1960s and 1970s in Senegal. Marame is an Associate Professor of African and African Diaspora Literatures at East Carolina University. Her work explores gender, verbal art, and migration. She is also an activists of women���s rights in Senegal and its diaspora.

Stream the show on Tuesdays at 4 p.m. in Dakar, 6 p.m. in Harare, and 12 p.m. in New York City.

Last week, we tackled Africa���s long, complicated, and evolving relationship with Asia, from its promising, Third-Worldist past to its present, as both are fully integrated into the world capitalist system. Thanks to Christopher J. Lee, Lina Benabdallah, and Abdou Rehim Lema for being such insightful and provocative guests. That episode is now available on our��YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

June 4, 2021

Trapped by history

Still from Sons of the Sea.

Still from Sons of the Sea. Abalone (or marine snails) is a hot commodity on the black market. It is a luxury food item particularly sought after in the far East and Europe. It is not surprisingly, also the life blood of working class families of fishermen who poach the marine mollusk from protected waters. Large syndicates, often linked to the drug trade or turf gangs, act as middlemen in the trade. South Africa, especially the coast around Cape Town, is a key node in this illegal trade. Just earlier this month, Cape Town police arrested 65 suspected abalone poachers in one day.

Sons of the Sea is a new feature film by Mexican-American director John Gutierrez. (The film had its premiere at Cinequest in March 2021 and will be showing again at the Durban International Film Festival in South Africa which takes place between 22 July and 1 August. 2021.)�� The film is set on the False Bay coast in Cape Town. The plot follows two brothers from the ���council flats��� on the wrong side of the tracks of the picturesque fishing village and tourist haven of Kalk Bay. One of the brothers stumbles across a motherload of poached abalone, or perlemoen as it is known locally. Older brother Mikhail (Marlon Swartz) sees it as his last ticket out of the ghetto, while for younger brother Gabe (Roberto Kyle) it could spell the end of a promising future. As they figure out a plan to sell the abalone on the black market, a rogue city council official (Brendon Daniels), who has his own set of personal tragedies to deal with, begins to hunt them down.

Still from Sons of the Sea.

Still from Sons of the Sea.Without being didactic, the film touches on colonialism, displacement, and man���s complicated relationship with nature. It is a beautifully shot, authentically performed thriller that will travel well on the festival circuit. Gutierrez is based in Cape Town (his life partner is the acclaimed South African writer and director Nadia Davids, an executive producer on Sons of the Sea) and we met to talk about the film and its themes; his documentary approach to making fiction; and the similarities between his native California and his current home on the tip of Africa.

Dylan ValleyThis film is very much a labor of love. How did the project begin?

John GutierrezIt really started in 2013 where a producer friend of mine and I came down to Cape Town looking for a story for a feature film. I told him ���dude we gotta take the train, head to Kalk Bay and you gotta see that coast.��� We did and took a couple of still 35mm cameras, hung out in the harbor took some photos and spoke to people ��� we knew there was something there. We just didn���t know what the story was, and then it just fell in the background.

In 2018, I had written this script, I was introduced to (producer) Khosie Dali through Imran Hamdulay, who also produced and did production design on the film. I wrote this script called Lie of the Land about a white family who moves into a home in Protea Village and the people whose home it was tries to get it back. It was a bit ambitious for a first feature, and Khosi was like ���I don���t think we can do this on $5,000!��� I was starting low. I knew we could raise more money, but I realized we had to do this on a shoestring.

Still from Sons of the Sea.

Still from Sons of the Sea.So, I put that away and I decided to do something very documentary style���with a few actors and a very simple story. I started to think about my own home in California, and about the themes I wanted to explore, and I wanted to explore brotherhood. I went back to this old story in the Mexican American community about this diver called Mechudo who goes diving as part of this contest. He gets greedy and goes for the biggest pearl and dies down in the water. There are many iterations of this story. He was also a Yaqui Indian, who are an incredible tribe that my family is descended from. This story was picked up by John Steinbeck, who wrote the novella The Pearl, and these became the two inspirations that I thought could be something that I could transplant to Cape Town. From there I started returning to Cape Town and talking to the young kids who live in the fisherman cottages, hanging out with them, watching them surf, etcetera and kind of approaching the story from a documentary angle, not really sure where it was going. I would hear little pieces of what they were up against. I came across the book The Poacher by [South African journalist] Kimon de Greef around the same time, and I became friends with him. And then I just started doing this deep dive into the abalone scene which is incredible. And then I realized this is not just about people trying to make a quick buck, this is everything. This is a global story. This is people trying to survive off their sea that they can no longer survive from.

John Gutierrez. Dylan Valley

John Gutierrez. Dylan Valley Why is the abalone trade such a big thing in Cape Town���s underground?

John GutierrezYou can go into the crime story, where it���s about gangsters, it���s about the Chinese triad, and it���s about drugs that get pumped into the Cape Flats in exchange for abalone that gets sold in China for hundreds and hundreds of dollars. For me, the abalone that Gabe and Mikhail find, that���s the bag of treasure, the ���McGuffin��� that pulls you through the story. At the core of the story, it���s about a group of men who come from a place in the world, who lived off that place, and they���ve been displaced. Because of systemic racism and the history of colonialism, they���re struggling to survive in the place they���re from. And that���s a universal story that connects to my people back home; the Black community, the Native American community and the Hispanic community. When they watch this film, they see themselves reflected in it. So, while I was telling a very specific South African story, in that specificity, I was telling a global story about brownness and blackness in a world that���s been colonized.

Dylan ValleyThere are definitely many historical and cultural similarities between California and Cape Town. Have you also found this to be the case?

John GutierrezThere are profound similarities in the landscape, particularly the San Francisco Bay Area where I���m from and Cape Town, that incredible, breath-taking meeting of mountain and sea. Then there are the radical differences between the wealthy and the impoverished���though of course those differences are much more intense in Cape Town. At an intimate level, I sense and feel a familiarity between brown Cape Town and mestizo California���the same history of cultural collision, of being a mix of indigenous people, folks brought over by force and settlers.��Other things are familiar too: the coming together of family in large numbers over food, the fashioning of the individual as a part of a collective, of a community. So there are both painful and beautiful markers of sameness.

Still from Sons of the Sea. Dylan Valley

Still from Sons of the Sea. Dylan Valley Keeping in mind the themes of colonialism and displacement, I noticed that there are no white characters in this film, despite Cape Town having a relatively large white population. Cape Town is often described in this way as feeling very colonial, despite being decades into democracy. Was this a conscious decision and what was the motivation behind this?

John GutierrezThe initial financiers recommended three white male actors for the role of Peterson, the government official but we (the producers) met as a group and decided to decline the offer. For two main reasons; I wanted to de-centralize whiteness in the film, though of course, it���s a consistent feature, the colonial imprint is everywhere, in the landscape, in the paintings, in the entire social context/construct of the boys��� world. But also, it was important because the official needed to come from the same world as the boys, and in a sense, all four of the male characters (from the little boy to the grown man) are representative of a single life and how trapped we can be by history. Also, it always hurts more when your own enact violence on you, we know that, and there���s a difficult, complicated history of how that happens.

Sons of the Sea premiered in March 2020 at Cinequest Film Festival in San Jose, California (John Gutierrez���s hometown).

June 3, 2021

The legacy of French colonial psychiatry

A still from Ousmane Sembene's "Black Girl."

A still from Ousmane Sembene's "Black Girl." This limited series, Psychiatry Beyond Fanon, published once a week, explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Technical University with contrIbutions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King’s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

Between 1897 and 1914, the French colonial government transferred more than 140 West African mental patients from Senegal to Marseille, where they were institutionalized within a large public asylum called l���Asile de St-Pierre. Though justified in humanitarian terms, this colonial experiment was an abysmal failure on all counts���an act of colonial violence framed as care, and staged within the Metropole itself. Few West African patients sent to Marseille were ever repatriated, and most died within two years of their arrival within the asylum.

Colonial psychiatry in West Africa had emerged first and foremost from an imperative to maintain colonial order, joining together medicine, surveillance, and incarceration in powerful and enduring ways. Always central to this project were questions of racial difference and the (im)possibility of assimilation. According to many colonial psychiatrists of the day, madness in Africa had been rare in precolonial times, but was growing more common precisely because of the inability of Africans to adapt to the conditions of colonial modernity. The possibility that colonial oppression and dispossession might itself be the root cause of mental distress was not given serious consideration until much later. Instead, the onus was placed wholly upon those who could not (or would not) assimilate.

With the transfer of West African mental patients to the Marseille asylum, colonial psychiatry was brought home, so to speak, producing a particular kind of encounter in which African bodies���and African madness specifically���became an object of medico-scientific scrutiny and careful observation at close quarters, within the Metropole itself. West African patients confined at St-Pierre were scrutinized for signs of assimilability and described in terms of their alterity. The patients, or les ali��n��s as they were called at the time, were imagined ���alien��� in the double sense of the French word later remarked upon by Frantz Fanon: both as estranged from themselves in their madness, and as distinctly foreign others. In a 1908 medical thesis written by a doctor named Paul Borreil that drew on his two years��� work as an intern in the Marseille asylum, for example, West African patients at St-Pierre are described as pitiable, but also indecipherable, unassimilable, and dangerous: these patients, Borreil writes, cannot be allowed to participate in events organized for patients because of their ���disorderly behavior, their tendency to run away, their unsociability,��� and anyway, they don���t ���take pleasure in that which entertains the other patients.��� They required constant surveillance and extra guards, and their unpredictable (sometimes violent) behavior means that they often need to be separated from the white patients and from each other. What is more, Borreil notes, the high number of tuberculosis-related deaths within the asylum is directly related to the presence of these patients, who are a ���source of infection��� and contaminate the other (read: white) patients. ���[T]hey spread their sputum (spittle) everywhere, and when it dries it mixes with the dust,��� Borreil writes. What is more, he stresses, West African patients refuse to sleep in beds, and instead ���wrap themselves in a blanket and sleep on the floor, where certain and inevitable infection��� awaits them. Borreil���s message is clear: the failure or inability of West African patients to comply with doctors��� demands and integrate themselves into the daily activities of the asylum not only stands as confirmation of their madness, but also reinforces racial difference as radical otherness, posing a threat to the institution itself.

I was in Marseille in spring 2020, doing archival research related to this story and searching for traces of the men and women subjected to this cruel intervention, when COVID-19 took hold. From the very start of the pandemic, I watched as the same gamut of racist tropes that animated the writings of colonial psychiatrists circa 1900���from speculations about Black immunity, to ideas about heightened vulnerability due to comorbidities, lifestyle choices, or a refusal to comply/assimilate, to fears that Black communities might in fact fuel the spread���began circulating in media outlets and online fora in France and beyond. By July, results from an INSEE (l’Institut national de la statistique et des ��tudes ��conomiques) study were showing an excess mortality rate of +144% in France for citizens or residents who had been born in sub-Saharan Africa���a markedly higher rate than that of French-born citizens (here and across many epidemiological studies, the French government���s ���color-blind��� approach to public policy and refusal to allow for the collection of data related to race or ethnicity leads researchers to lean on ���country of origin��� data to do comparable work). While it was by then generally accepted that these higher mortality rates were related to the overrepresentation of persons of African origin among frontline workers, many commentaries still fixated upon behavioral choices and noncompliance as the heart of the problem: ���Take a walk ��� around Ch��teau-Rouge and Ch��teau d���Eau, near the Gare du Nord and the Gare de l���Est, and you will see the African neighborhoods of Paris: nobody���s wearing a mask and people stand huddled together. That���s the first ��� risk of contamination.���

I was still in Marseille when, in the wake of the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in the US, thousands of people took to the streets in cities all over France in a show of solidarity for Black Lives Matter and to demand justice for Adama Traor��, a young black man who died in police custody in July 2016, and greater accountability from their own police. Since those protests, it should be noted, quite the opposite has happened: A ���global security��� bill was fast-tracked through the French National Assembly in November 2020 that aimed to both increase the surveillance capacities of the police and expand police protections. Article 24 of the contentious bill imposed a penalty of up to a year in prison and ���45,000 for disseminating images of officers or soldiers engaged in police operations, a move that critics fear will allow police to operate with even greater impunity. The bill met with such massive public outrage and large-scale protests, however, that ruling party members of parliament walked it back in early December with the promise that Article 24 would be rewritten.

A brilliant recent AIAC article written by Florian Bobin titled ���Law and Disorder��� draws a direct connection between forms of surveillance, policing, and incarceration that were established and refined in France���s colonies and the contemporary crisis in policing in France today, where young men perceived to be Black or Arab are 20 times more likely to be stopped for a police identity check than young white men, and where the practice of racial profiling has begotten numerous cases of harassment and police brutality. In a similar vein, colonial medicine and colonial psychiatry laid the foundation for the ways in which ���native��� minds and racialized bodies���Black bodies in particular���come to be imagined and pathologized in terms of risk and contagion, both within popular media and in the domain of healthcare in France today. Significantly, this alienation has contributed to a slew of negative health outcomes: Among patients of African descent, for example, legitimate health concerns are frequently downplayed, dismissed, or misunderstood in culturalist terms. French citizens/residents with origins in sub-Saharan Africa report high rates of discrimination in health care settings (the highest of these being among Muslim women), which has in turn been linked to patients avoiding or forgoing health care altogether.

My own research likewise underscores the extent to which the (il)logics of race in contemporary France���born and refined in the colonial encounter, perpetuated through its institutions and policies, and played out in myriad forms each day���are both recursive and accumulative. Racial discrimination and inequality pose an ever-present and enduring threat to the health and livelihood of racialized persons in France, even as the social reality of race continues to be denied, and even at a moment when postcolonial scholarship is itself blamed for creating the very problems it seeks to address.

June 1, 2021

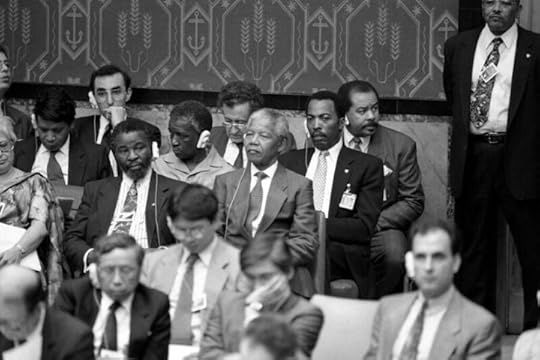

Kwame Nkrumah and Israel

Parts of this text are adapted from Israel in Africa: Security, Migration, Interstate Politics, published by Zed Books.

In April 1959, the first Africa Freedom Day event was held at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. It was a ceremonious gathering that marked the anniversary of the First Congress of Independent African States, held in Accra exactly one year earlier. The only member of the United Nations not invited to attend the event was Israel. Israel already had diplomatic ties with several independent African states at the time, but among the sponsors of the event in New York were Egypt (then the United Arab Republic), Libya, and Tunisia, who threatened to boycott if Israel was included. Their position prevailed.

In Jerusalem, Israel���s exclusion from the ���African Party��� caused considerable anxiety, to which a pile of telegrams in the Israel State Archives testifies. In the following year, therefore, attempts were made to guarantee Israel���s participation in advance, and Ghana, upon Israel���s insistence, agreed to call for its invitation. This led to a confrontation between the Ghanaian and Egyptian ambassadors to the UN, but once again, the Arab position prevailed. Ironically, Israel���s complaints that it was being unreasonably singled out only led to the exclusion of another country from the 1960 Freedom Day gathering: apartheid South Africa, the last country Israel wanted to be publicly associated with at the time.

There was a good reason behind Israel���s preoccupation with its right to attend these early celebrations of African independence. In April 1955, Israel was excluded from the first Asian���African Conference in Bandung. Not only that, but the participants of the conference also formally expressed their support ���of the rights of the Arab people of Palestine and called for the implementation of the United Nations Resolutions on Palestine and the achievement of the peaceful settlement of the Palestine question.��� The Bandung conference prompted a reassessment of Israel���s foreign strategy. To prevent Arab states from mobilizing, as one official put it at the time, ���a broad and unified front of Asian and African nations��� against it at the UN, Israel soon began to seek alliances in Africa, making an effort to brand itself as a legitimate member of the postcolonial Afro���Asian world.

Israel���s relationship with Ghana marked the beginning of these diplomatic efforts. A consulate in Accra was established in 1956, prior to Ghana���s independence, and it was upgraded to an embassy upon independence the following year. Ehud Avriel, Israel���s first ambassador to Ghana, recounted that at independence Kwame Nkrumah presented the Israeli delegation with ���the same list of urgent requirements he expected from other older states,��� and that within a year ���every single requirement on Nkrumah���s list had become a subject for intensive cooperation between Ghana and Israel.��� Ghana was to turn into a ���showcase of Israel���s aid in Africa���s development,��� and thus pave its way to international legitimacy.

Several bilateral initiatives were developed. The Israeli water planning authority assisted with water infrastructure development, the Israeli construction firm Solel Boneh helped establish the Ghana National Construction Company, and a Ghanaian���Israeli shipping company was established, 60% of which was owned by the government of Ghana and 40% by the Israeli shipping company Zim. The two countries signed a trade agreement and Israel extended Ghana a $20 million loan. Israel also sold light arms and provided training to the Ghanaian army, while Israeli military officers assisted with the establishment of the Ghanaian Nautical College and the Flying Training School, which trained pilots for the Ghana Air Force and Ghana Airways. One Israeli expert even assisted with the establishment of the National Symphony Orchestra.

Ambassador Avriel became a close confidant of Nkrumah, who was able to facilitate contact with other African leaders. In March 1958, Israeli Foreign Minister Golda Meir attended Ghana���s first independence anniversary as part of her first visit to the African continent. She met with both Nkrumah and Trinidadian Pan-Africanist George Padmore, and was invited by the latter to address representatives of multiple African liberation movements visiting Accra. If Padmore and Nkrumah hoped to prevent Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Soviet Union from dominating the Pan-African agenda, Israel hoped that an autonomous African bloc over which Arab leaders had�� limited influence would strengthen its position in the international arena and allow it to obstruct Arab initiatives at the UN, particularly with regard to the right of return of Palestinian refugees.

Following the experience in Ghana, a decision was taken in Jerusalem to pursue ties with other African nations before they gained independence in order to curb Arab influence as early as possible. Israel began sending envoys to African countries to court those who were expected to lead their nations after independence, promising technical assistance and military training. This strategy worked. By 1963, Israel had 22 embassies in Africa. The only two countries that achieved independence at the time south of the Sahara and did not establish ties with it were Mauritania and Somalia. The growth in Israel���s presence in the continent in the early 1960s was extraordinary, especially given that it did not build on any existing diplomatic networks from the colonial period.

The warm ties with Ghana were crucial for Israel���s expansion in Africa at the moment of the continent���s independence, but they were also short-lived. By 1961, Nkrumah���s vision of a federated Africa drew Accra closer to Cairo. In January that year, the leaders of Ghana, Mali, Guinea, Morocco and the United Arab Republic convened in Casablanca against the background of the political crisis in Congo. At Egypt���s behest, one of the topics discussed was the Israeli���Arab conflict, and a resolution was adopted, denouncing Israel as ���an instrument in the service of imperialism and neo-colonialism not only in the Middle East but also in Africa and Asia.��� To pursue his political vision, Israeli diplomats assessed, Nkrumah was willing to take a more critical stance towards Israel. But Israel���s close relationship with France (then its main arms supplier), the US and the UK, was also undermining its relationship with Ghana.

Israel, in response to the developments in Casablanca, sought closer ties with the leading states of the opposing ���Monrovia bloc���, whose members rejected the idea of an African federation propagated by the ���Casablanca group��� in favour of a greater emphasis on state sovereignty and non-interference. The ���Monrovia states��� were not necessarily more pro-Israeli. Among them were Somalia, Libya, and Mauritania. But they avoided the Israeli���Arab issue altogether for the sake of pragmatic multilateral cooperation, a position that ultimately served Israel as well. Due to their opposition, the issue also remained largely off the agenda of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), established in Addis Ababa in May 1963, in its early years. By then, Israel���s focus in Africa shifted to the eastern part of the continent, where it cultivated close (and more militarized) relationships with elites in Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania.

In the years of African independence, Israeli rhetoric portrayed Israel as a young, post-colonial nation and Zionism as a liberation movement, associating the Jewish state with other newly independent nations in the ���Third World,��� and rejecting the comparison between Zionism and imperialism. After the war of 1967 and Israel���s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, this narrative became increasingly untenable, and Israel���s ���golden age��� in Africa gradually came to an end. One thing that the brief Ghanaian���Israeli ���honeymoon��� of the late 1950s indicates, however, is also how from the very moment of African independence, concerns over Arab influence over African affairs meant that Israel was suspicious of initiatives that appeared to take too seriously the idea of Pan-African integration and unity. Such initiatives, clearly, threatened to complicate its efforts to project its influence into the continent.

More than five decades later, it is now Gulf countries that are trying to persuade African states���from Sudan to Mauritania���to normalize ties with Israel. But precisely for this reason and as extreme international inequality becomes ever more entrenched, the logic that underpinned earlier calls for continental unity continues to resonate. ���Singly we are too weak to avoid being used by those whose help we need, but together we shall be able to accept aid and investment without endangering our national integrity and independence,��� Julius Nyerere wrote to Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion following the formation of the OAU in 1963. ���It is in this spirit that we are working towards African Unity. We have no desire to isolate our continent from the rest of the world, nor to build an aggressive, hostile continent.���

The house of migrants

A still from the film The Last Shelter.

A still from the film The Last Shelter. Ousmane Samass��kou just won the main DOX:Award at the 2021 CPH:DOX for his second feature-length documentary, The Last Shelter (Le dernier refuge, 2021). The film is an intimate portrait of the lives of Esther, Khady, Natacha, and several other individuals who pass through the House of Migrants, a refuge in Gao, Mali, as they embark upon or return from their tumultuous journey across the Sahara in hopes of reaching Europe. The film also screened at Hot Docs and is in competition at Doc.fest Munich. A��cha Macky���s film Zinder (2020) had its world premiere at the Visions du R��el festival, where it entered the feature-length documentary international competition before going on to the Change Makers program at CPH:DOX. It is now competing in the Official Selection Competition at DOK.fest in Munich. Zinder, the second largest city in Niger, and where A��cha was born and raised, became her camera���s focus once she earned the trust of gang members from the disadvantaged neighborhood of Kara Kara. By telling their story with them as opposed to about them, Zinder changes the narrative about the lives of gang members, not only in that country, but across the world. Ousmane���s and A��cha���s films are the first two films that figure among those selected for the Generation Africa project in collaboration with STEPS South Africa, a series of short and feature-length documentaries made across Africa that seeks to create new narratives on migration from youth perspectives across the continent.

I spoke with Ousmane Samassekou (OS) and A��cha Macky (AM) about their films, their collaborations, the inspirations for their films, their documentary auteur styles, and reception and funding.

Sara HanaburghOusmane and A��cha, your first films were successful and now here you are once again, both on the international festival circuit. You���ve worked together as well. Can you talk about your collaborations?

A��cha MackyI sought out Ousmane. I had met him a few times when we were in school, when he was a young producer. I had never made a feature before, and Ousmane gave me a chance to prove my worth. He is also lively and pragmatic and willing to take risks. For me, [the way to do it is] you start with someone who has zero experience and you let them shine. That���s how I came to work with Ousmane, and I do not regret it.

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouI met A��cha in 2013. We were pitching our films then: she, The Fruitless Tree, and I, The Heirs of the Hill. I was in awe of the way she brought out fragility and humanity in her story. When she contacted me about her project Zinder, I was quite moved because I like what she does, not only as a film director, but also for her activism on social issues. It was also an honor for me, fresh out of production school. I immediately agreed. It was a pretty colossal project, a challenge, and it brought me back to my own first film, which was also inside a system that was quite violent.

Sara HanaburghWhat inspired you to make your films?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouAs a kid, I was fascinated by the people who would leave, because I had an uncle who had left. I don���t know why he left, or why he didn���t come back. And in my family, there was always this story about my uncle that remained in suspense. The absence of this uncle. As I was growing up, I came to realize that the entire family had helped him prepare to leave. Some had given him money; others had made sacrifices, prayed. My grandmother would tell me the story of this uncle who was brave, a warrior who had to leave everything to go and find happiness for the family, leaving his two children and his wife who never remarried. So I was always curious about how someone could just leave everything and go, and I wanted to make a film about it.

Sara HanaburghHow did you go about writing?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouI remember the first draft that I had written. I sent it to A��cha and she said to me, ah, that���s very poetic, but there is no story in there. I was searching for the story I wanted to tell, and I was gathering images that were a bit metaphorical, you know? At that point, I was thinking only of the departure, of putting together various stories of people who had left along with abstract images of the desert, a pirogue on the river. Around that time there was the call for films by Generation Africa in Burkina [Faso], and my proposal was accepted. So we went to [Ouagadougo], and while we were there, a gentleman named Albert from Niger gave a talk on migration, and he started talking about a place called the House of Migrants. And being one of the only Malians there, I was amazed to find out that there was this house in Gao on the edge of the desert that welcomed migrants upon their departure as well as their returns. I had to go see what was happening there. Albert gave me the email of the coordinator at the House of Migrants, whom I harassed many times before I could get the authorization to go there. Finally, when I arrived, I was fascinated by a woman there who was amnesic, who no longer knew how to return to her home. She had been there for five years. That woman���s story brought back memories of my uncle. I thought that he, too, was lost somewhere.

Sara HanaburghThat���s Natacha���s story?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouNatacha, exactly. I thought, maybe my uncle is dead, or perhaps he is like Natasha, whose family is waiting for her somewhere, thinking that she is dead and awaiting her return. That���s how the journey of making The Last Shelter began. The question had become how to transport the viewer into the space of the desert on the migrant���s journey without filming an individual or a migrant actually making the journey, with only images of the desert.

Sara HanaburghWhat inspired Zinder, A��cha?

A��cha MackyI was born and grew up in Zinder, and until I was 30 years old, I had never once set foot in Kara Kara, a neighborhood up on a hill, where lepers and beggars were sent away to. It seemed mythical to me. Mythical because people talked about it but had never been there. I thought back to my childhood. When I was in preschool, age four or five, there was a water tank which would cross the city every day, transporting water to the people in Kara Kara so they could have water to drink. As children, we would see this, and I remember we would give food to the children of Kara Kara; but we would open their bags with sticks so as to avoid coming into direct contact with them, so we were not contaminated. So there was this injustice that we committed, even as children. You see, there was a sort of invisible border��� a psychological barrier���between us and them, and that astounded me. As children we were manipulated to think that lepers were contagious and so I started thinking of making some sort of reparations for the people whom we had stigmatized. Additionally, at one point, the international media started reporting on acts of violence carried out by gangs, called ���palais.��� It brought back childhood memories when we used to welcome anyone who was hungry to share our food���our doors were always open���or when I would run around with my friends, and climb and slide down those huge boulders which you saw in the film. All of that was no longer possible because of those stories of violence. That resonated with me. So I decided to go back to my city to find out what was really going on. That was the first time I ever set foot in Kara Kara, that neighborhood completely ocher in tones, and it stirred up all sorts of emotions inside of me, including fear, and fascination too.

Sara HanaburghHow did you decide to portray Kara Kara in your film?

A��cha MackyI had to kind of completely change my life and meet the people there; let go of my judgments. In Kara Kara, I saw people who were not so different from elsewhere, from gangs in the ghetto of the United States, for example, or from the children in the Parisian banlieues and other peripheral neighborhoods across Europe, where people live a certain social injustice and are seeking rights. Rights to education, rights to food, to shelter. Quite simply, that was what led me to point my camera at this social situation, to try to document it from the perspective of this youthful population whom people wanted to hide from view.

Sara HanaburghAt the beginning of Zinder, you ask one of the reformed gang members, Siniya Boy, what the difference is between you and him. His response is education. What does he mean by that?

A��cha MackyThere are many things lacking in Kara Kara compared to my neighborhood, which is also a rather modest neighborhood in the city. Arriving in that neighborhood led me to understand so many things, not only a certain poverty all around, but also that strong communities had formed around these people who knew that their wrongdoings were not the answer. On the state level, the neighborhood was created; it was unplanned. There was no water, no hospital, there was absolutely nothing at all. It was a sort of nomad���s land to herd people, like animals. At first, lepers were sent there. Then beggars. It was a sort of statelessness within the state. Even in terms of forms of ID: they didn���t have it. As a result, many people there did not have the right to go to school. The few who were allowed to go to school had to leave their desks and let other children sit there because some more advantaged families didn���t want their children sharing the desk with the poorer children. And that really got to me.

Sara HanaburghAlso, I think of the favelas in Brazil, which is yet another example of communities that society prefers to hide and maintain invisible, voiceless.

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouActually, the favelas in Brazil, the banlieues in Europe, or the ghettos in Nigeria were exactly the types of examples we talked about when we were producing Zinder. These are neighborhoods which at one point or another had been invaded by modernization and urbanization, and were just left to fend for themselves, make their own laws. The police didn���t go there, nor did the government. In fact, there was no policy for the development of these enclaves.

Sara HanaburghLet���s talk a little about the writing, the creative process of your films. Both of you had to gain the trust of the individuals and the communities you were filming. It comes out very clearly in each of your films. Ousmane, you capture a deep intimacy with regard to your characters Khady and Esther. And then they become friends with Natacha. It is obvious that you also have contributed to this sense of intimacy between them.

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouActually, when I pitched the script, I didn���t even know that I was going to meet Khady and Esther. I met them during the last shoot. But what I did know was that Natacha was always there. So the project developed quite a lot in terms of writing while I was filming Natacha. However, in practice it was quite difficult with Natacha, because she was always very quiet and didn���t manage to construct her own story. And then, by chance, during the last shoot, I found Khady and Esther. At first, Khady was more willing to be filmed, and Esther outright refused. She just wanted to leave, and the people from the House tried to calm her down. But she was very spirited, she wanted to leave. So I started filming Khady first and started showing her images to Esther and as she watched, she became more and more relaxed. Once I had established those exchanges with Esther, I said, now let���s make a short scene, but this time without Khady. And when I made that short scene, she said, oh wow, I want to be an actress now! She started to loosen up. She had dreams: of becoming an actress, a boxing champion. And I was there, like, wow. I told her that what we were doing was a little different. It���s a documentary, so you have to be more natural. We���re going to film you in your everyday without interfering very much. I started filming them together and getting to know Esther better and better. She was extremely natural and unbelievable! Sometimes she would forget I was even there with my camera and would fall asleep while I was filming her! There���s something unbelievable about that young girl! She is incredibly warm, intelligent, spirited. I mean, she can be jovial, happy, joking; then she can be completely curt. And when she started telling me her story for the first time, about her mom, I made the connection with Natacha, who was also searching for her family. Esther almost didn���t know her family at all. She did not know her father. She only knew the woman who raised her, and when she passed away, Esther was told that that woman was not her real mother. The children of that woman told her, ���You are not our mother���s child.��� So it was a double shock. Esther was looking for a mother and Natacha was looking for a family. She doesn���t remember if she has any children. But when you look at Natacha, you sense that she does have children. So I tried to focus on her interactions with Esther in particular, on connections between a mother and a daughter���one looking for her family and one looking for her mother.

Sara HanaburghWhat a process, wow!

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouYes, that���s what I like about the documentary genre. It���s those surprises. I could have never imagined Esther and Khady. I didn���t know at first that they were going to be the main characters in the film. And yet, they carry the film, and I am happy about it.

Sara HanaburghA��cha, I noticed that the members of the palais love to flex their muscles for the camera. Did that allow you to enter into their space with your camera? But seriously, how did you gain their trust and in what ways were they engaged in the process of telling their stories?

A��cha MackyI had the opportunity to meet some of the palais members several times. [Electricity cut interrupts the interview, we laugh.] And I started observing how those palais function, and there were all sorts of rituals involved. If, for instance, someone wanted to join a palais, they were given a test, to test their loyalty. I didn���t manage to pass the tests, and they tried to scare me, but I kept going back and, at some point, they gave up. They could see that I was not going there just to film them. I was for real and I wanted to talk with them. I went back several times, which allowed them to see there was something that I wanted to have with them. In the end they understood that I wanted to make a film that would allow their voices to be heard, to allow them to express themselves. That is how I managed to convince them that I had a way for them to make themselves heard beyond that border. And once they understood that I could also be their bullhorn, all the walls they had built between them and me started to come down. It took years.

Sara HanaburghHow many years did it take you to build this trust?

A��cha MackyEight years. From the pitch to the pilot, it took eight years. It was a project in the making well before The Fruitless Tree. Also, I did not set out to make a film about the children of Kara Kara. My preference was to make a film with them. And making a film with them implies their participation in making the film. If you���re going to make a film, you have to come to where I am from. To come to where I am from, you cross borders. When I was going to Zinder, I was also working on several other smaller projects. I was also a volunteer in a USAID program called Search for Common Ground. For that, I was training youth with respect to transformations from conflicts and how we could confront extremism and violence through debates and conversation, and so the film is about something very real that exists in the heart of communities. That is how I really came to understand the mechanism of how those gangs worked and that���s how I ���infiltrated��� them.

Sara HanaburghOusmane, many people who pass through the House of Migrants have some sort of psychological trauma. What inspired you to place emphasis on this subject in your film?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouWell, it has always been a sort of taboo subject when someone does not manage to achieve their goals, doesn���t manage to get to Europe and is repatriated and returns home in spite of him or herself. This has always been a taboo subject because immigration has always been a family affair in Africa. That���s to say that when a child decides to leave, the whole family supports him. What the child is not told is that when you are on that journey, you will pass through dangerous zones in the Sahel or the desert or on the sea; there is a lot of smuggling���human smuggling, sexual enslavement���many things that are really inhuman. And when you go through that sort of thing, you never come back as a full human being. I thought it was important to show in the film that there are many types of trauma.

Sara HanaburghThe absence of the state is noticeable in each of your films. Can you talk about that?

A��cha MackyYes, it���s important to talk about that. Kara Kara, as I mentioned, was a village that was created with absolutely no public policy, whether access to health care or education, and this continues today in the 21st century. So as we are organizing international screenings for June, I���ve asked UNHCR if we can bring five characters so that they can bear witness to the film being shown internationally. But of course, in order for them to travel abroad, they need an ID card to get on the plane. To travel. And they don���t have one. So right now Siniya is having his friend���s birth certificate made. And the guy, Tchicara, is in prison. He has no birth certificate! This thirty-year-old has no civil status. That���s one reason I talk about these stateless individuals inside the country. You are there. You exist, but in reality, you do not exist, not when it comes to the state. And you mentioned the hospital. Even when it comes to the public hospital, there isn���t really basic care for stateless people. That���s the reason that many children who are born in Kara Kara have not been to school, because in order to receive even a little care at the hospital, you have to have a little money. To pay for the bed when a woman gives birth. But that���s money people don���t have because they barely have money to eat. There are many people who are born without legal status, and if you don���t have access to civil status, you don���t have access to school. And when the child is old enough to vote, he cannot vote. His voice is stolen.

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouImmigration is a situation that brings grief. Everyone in my family is still asking whether my uncle is coming back. Is he alive or dead? We also know other families who are grieving the departures of their sons and daughters, women who are widows but don���t know it, who are there waiting for their husbands; there are lots of fatherless children because of that. Why does this situation persist today in the 21st century? It���s because there is no real policy, actually, that prevents people from leaving. Why do people leave? They leave because they don���t have basic care. They leave because there is a lack of education. The majority of those who leave have not had the chance to go to school. So either they went to school and did not finish, or they completed their studies but there are no jobs. They go so they can provide for their families. There is also inequality of opportunities in the hiring system, so those who come from minority or poor families have to go looking elsewhere. The first thing that comes to mind is to go to Europe, to go through the desert or across the sea. There���s a lack of political commitment on behalf of the state. That���s what makes me want to be in this profession, to make documentaries, to talk about taboo subjects and denounce what is wrong. That���s also why I love the name of A��cha���s production company, Taboo Productions. Those are topics that are almost untouchable in our societies, but we are going to touch on them. We���re going to talk about them.

Sara HanaburghLet���s talk about sound and visual framing. Ousmane, your film is very poetic. Particularly striking in your film are the whipping winds of the desert. But also, visually, your framing is distinctive.

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouIn terms of sound, when I was in the desert for the first time, I was amazed to hear that the desert has its own musicality, and its silence is glacial! It���s different from any other silence. When you���re in the desert and there is absolutely no sound, it���s unbelievable. And the force of the wind brings out different emotions. Visually, I wanted to make something photographic, to show for example that when the sun starts coming up and you see a little sand, it���s as if the sand were coming out of embers. It���s stunning. So what I wanted to convey in the film is that the desert has something poetic about it but at the same time something sad.

Sara HanaburghA��cha, visually, one thing that resonates in your film is the relationship between the body and the land of the Sahel. For example, you manage to capture beauty even when you���re filming scars. Can you talk about that?

A��cha MackyYes, for me it was important to approach it allegorically. The history of that neighborhood goes back to the question of skin, actually. Just as drought leaves marks on the earth, leprosy leaves scars on one���s skin, and in the same way terrorism in a city also leaves its indelible mark. So, whether drought, illness or terrorism, it all leaves scarring on one���s skin. So, I made allegories out of this, and I am proud to hear that they come through in my film.

Sara HanaburghHow were your films received at the festivals?

A��cha MackyWhen it comes to festivals, with these world premieres, I find it to be quite a beautiful thing but also quite a pity at the same time, because oftentimes the people who are in the film don���t have the opportunity to see themselves on screen before the international audience sees it. On the other hand, the interest of the international audience allows the film to echo beyond borders.

Sara HanaburghHave you shown your film locally? Did your cast get to see themselves in your film?

A��cha MackyLocally, I was able to show my film while it was in completion to one of the protagonists, Siniya Boy, who had come with me to attend a forum. He came to speak on behalf of the youth. He is among those who represent Zinder. I had invited him to my place, into my small living room, together with another person who had made contact with Siniya, whose name was Asmana. When they watched the film, it was very emotional. It was also the first time that I became emotional after the film, because they said to me: ���We have never before been shown to be as dignified as you showed us to be, A��cha.��� And that moved me, them telling me that I had shown them to be human, as opposed to just showing them as criminals or thugs. For Siniya to come away from the film knowing that he was shown with so much humanity, so much dignity as he said, that made me feel like I succeeded. I could have shown them in a different way, images of their fights, their fresh wounds.

Sara HanaburghBut there is not a single image of that.

A��cha MackyRight, I really wanted to show that violence was something they had left behind, that they had taken the path of change. And what I am doing currently is, I am organizing a peace caravan to bring my film to more communities in Niger. Each morning, there are about a hundred buses that leave Niamey, the capital where I live now, for various cities around Niger. My impact campaign, with support from UNHCR, is to put my film inside those 100 buses, and I will be there too, along with some characters from the film. And like that, we are turning those buses into mobile movie theaters.

Sara HanaburghAnd the funding?

A��cha MackyI am currently seeking funding. We have already applied to the USAID YALI���the Young African Leaders Initiative���because each year they have the Alumni Engagement Innovation Fund. I need to secure additional funding, and I am going to seek funding from the government of Niger. And with the support from UNHCR, the impact campaign is something that resonates throughout the world, in the US and in Europe. It���s a model. We make linkages between the children of Kara Kara, for example, who can participate in training and educational programs if we have funding. And they can then pursue their dreams. My larger goal is to build bridges between these youth and international organizations

Sara HanaburghOusmane, have you been able to show your films locally as well? In Mali? In other countries in Africa?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouRegarding the circulation of my film, like A��cha, we have what you call an impact process, and we are seeking institutional funding from NGOs and private companies to circulate my film. In Mali, we are quite used to working with the Digital Mobile Cinema, the CNA, to show the film across Africa. We���ve also promoted the film in Mali, for instance at the French Institute, at the Cine Balimbao, and also at a few big schools in Mali, which allows us to show the film to lots of youth, some of whom want to leave. We talk about what is at stake when it comes to immigration. And we hope that we���ll be able to go beyond that, to go to the most remote areas of Mali to show the film, because I think that, like A��cha said, it���s extremely important for an African filmmaker to be able to show our work in our countries. We are also planning to show The Last Shelter in Gao at the House of Migrants, which is organizing a screening for each group of migrants upon their arrival because their role is to inform people as best as they can about their departure. Also, the film allows people to see themselves and what this House offers in terms of welcoming and recovery, and reestablishing contact with families.

Sara HanaburghWhat do you hope that The Last Shelter can bring to international audiences?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouWe have the capacity to show what is happening in our area of the world in ways that are not dehumanizing, without showing the poverty, misery, and illness that are usually incorrectly projected about Africa and that hide our actual reality, our humanity and humanism. I think it���s an opportunity for people to learn not only about what is happening, but also, I hope that a lot of people who see the film will understand what is at stake for those who are in this situation, who have these dreams, the desire to leave on a journey through the desert.

Sara HanaburghLet���s talk about production. In Bamako, you work with DS Productions?

Ousmane Zorom�� SamassekouI am an associate producer at DS Productions in Mali. With digital filming being favored, there is a lot happening. A lot of people are interested in cinema and television, and there are many initiatives, like Illustration Africa, OuagaLab, Africa Direct, and lots of young directors. The thing with digital filmmaking is that it has not facilitated North-South co-productions. What is of interest with regard to North-South productions is that it allows for the promotion of our films beyond Africa. We still need the North for financing and to be able to develop our films, because on the continent we don���t have a real cinema industry. But for digital filmmaking, we have great African technicians who can make films without any need for contributions from the North.

Sara HanaburghA��cha, can you tell me about your production company in Niamey, Taboo Productions?

A��cha MackyI ended up creating my own production company because there were practically none in my country. Also, in economic terms, making documentary films is not a big moneymaker like commercial films and doesn���t necessarily allow you to live from your art. You make a film and it basically belongs to your producer. So Ousmane encouraged me to open my own production company. However, I am not a producer. That���s why I called Ousmane, so that he could produce my film and I could concentrate on the artistic aspects of my film. Additionally, the idea was to help young talent, much like Balibari did for me, and so my production company is open to any artist who would like to work in it.

May 31, 2021

Accra to Bandung, Addis to Beijing

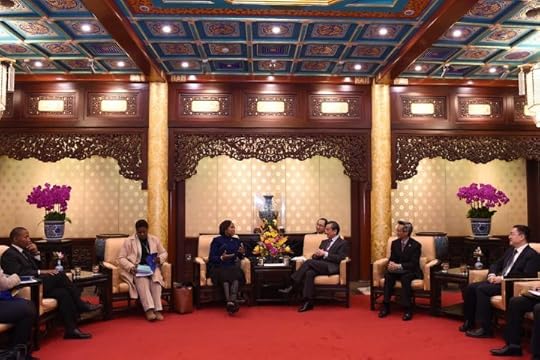

South African and Chinese diplomats in February 2017 (GCIS, via Flickr CC).

South African and Chinese diplomats in February 2017 (GCIS, via Flickr CC). Increasingly, the global political order is viewed as being in a proto-Cold War moment. The West is in decline, and the East is rising. Rather than walking back the enmity displayed towards China from Donald Trump���s presidency, US president Joe Biden has sharpened it, elevating the stakes of the post-COVID recovery as concerning not just a return to national normalcy, but the question of who will lead the COVID-free world. Not only would this be a world after COVID, but a world without a credible growth model, in the ruins of neoliberalism and at the door of climate catastrophe.

As these ���great power��� binaries make their way into politics again, it���s helpful to recall that the last time they existed, there were other political possibilities. Before the boring neutrality of the ���Global South���, there was the counter-hegemonic posture of the Third World. As AIAC contributor Christopher J. Lee once wrote, in the mid-twentieth century:

In contrast to many contemporary understandings of this expression, the Third World was embraced as a positive term and virtue, an alternative to past imperialism and the political economies and power of the US and the Soviet Union. It represented a coalition of new nations that possessed the autonomy to enact a novel world order committed to human rights, self-determination, and world peace. It set the stage for a new historical agency, to envision and make the world anew.

The historic site for the official formation of Third World identity was the 1955 Asian-African conference when delegates from 30, mostly newly independent states descended on Bandung in Indonesia to discuss their mutual ambitions for post-colonial world-making. Then, the affinities between Africa and Asia were obvious and deeply felt���as the first president of Indonesia, Ahmed Sukarno, stated in his opening address at the conference: ���For many generations, our peoples have been the voiceless ones in the world. We have been the unregarded, the peoples for whom decisions were made by others whose interests were paramount, the peoples who lived in poverty and humiliation.��� In Africa Must Unite, his manifesto for African unification, Kwame Nkrumah (who also spearheaded the Non-Aligned Movement that would concretize principles developed at Bandung), echoed Sukarno by declaring that ���The great millions of Africa, and of Asia, have grown impatient of being hewers of wood and drawers of water, and are rebelling against the false belief that providence created some to be menials of others.���

What has become of this organic Afro-Asian solidarity? Of course, the world after national liberation is very different, one where the imperial power structure involves the participation of, rather than contestation from, national governments and the domestic capital they represent. With the rules of the economic order accepted, all Asia represents for Africans is a developmental model outside the scars of�� US-sponsored free trade liberalism and structural adjustment. Buoyed by generous investment from China, some believe Africa���s ���Asian tiger��� moment is around the corner; while others warn of a ���Debt trap��� where China ensnares countries in financial arrangements that ultimately give it exclusive control of national assets. But, as AIAC contributor Lina Benabdallah recently said in an interview, ���We have no evidence to back these speculations but from an African perspective, these speculations have one thing in common: they imagine Africans to be incapable of making decisions on their own.���

But how do we restore the agency of Africa in conversations about her fate in this conjuncture? And what of the relationship not only between Asia and Africa but between Africa and Asia? There is, for example, a sizeable African diaspora in Asia, and despite coziness at the level of the political elite, ordinary African migrants in Asia are racially othered as much as they are anywhere else in the world���as Abdou Rehim Lema has written about for the site. So, to help us make sense of the complicated, contradictory past and present of Afro-Asian relations, this week on AIAC Talk we are joined by Abdou, Lina, and Christopher.

Abdou, from Benin,��is a Yenching Scholar of Peking University, where he completed a Master���s Degree in China Studies, focusing on Politics and International Relations. His research work focuses on South-South Cooperation, Triangular Cooperation, and the growing Sino-African security and development relations; Lina is an�� Assistant Professor of Politics and International Affairs at��Wake Forest University. Her��research��focuses on international relations theory, foreign policy,��critical theories of power, and knowledge production and hegemony in the��Global South; and she is the author of�� Shaping the Future of Power: Knowledge Production and Network-Building in China-Africa Relations��(University of Michigan Press, 2020); and Chris is an Associate Professor of History and Africana Studies at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, and is the author of six books, including Making a World after Empire: The Bandung Moment and Its Political Afterlives (2010, 2nd edition 2019), Frantz Fanon: Toward a Revolutionary Humanism (2015), and Kwame Anthony Appiah (2021).

Stream the show on Tuesdays at 4 p.m. in Accra, 11 p.m. in Bandung, and 12 p.m. in New York City on Youtube.

Last week, we continued exploring the concept of exile through two new artistic works: one, a film on a Libyan dissident directed by Khalid Shamis, and the other, an exhibition on the black experience created by Cedric Brown and co-curated by Odysseus Shirindza. We were joined by Khalid, Cedric and Odysseus to discuss their works. That episode is now available on our��YouTube channel. Subscribe to our��Patreon��for all the episodes from our archive.

May 28, 2021

Another neoliberal Spring

Photo: Random Institute.

Photo: Random Institute. Uganda���s January 2021 elections were a showdown of domestic and international politics, global political economy, and international development, all at once. They also marked another step in the long transformation of the country towards a fully fledged neoliberal society.

The two competing main narratives of the election campaign were not new. President Yoweri Museveni was portrayed either as a dictator or as a visionary; the country was either on the road to prosperity and with a secure future for all, or instead was a country in deep crisis and back to ���square one��� politically. These bifurcated discourses and the state violence that underpins them are long-standing features of the making and operation of neoliberal Uganda. The idiosyncrasies of these two competing discourses were already manifest before the beginning of the 2021 election campaign���a mix of economic depression, systemic corruption, widening inequalities, and endemic poverty hand-in-hand with growing state repression of mushrooming, diverse, and localized social struggles.

Two events were significant in the years leading up to the election: First, the detention and torture in August 2018 of the popular ���ghetto��� musician-turned-politician Bobi Wine���the NUP (National Unity Platform) presidential candidate, the main opponent to the US-backed military rule of Museveni, and, for significant numbers of people, an embodiment of the aspirations and imaginaries of masses of young voters. Second, the imprisonment of Museveni���s vocal critic, feminist scholar, and activist Stella Nyanzi in the same year. They point to the increasingly authoritarian character of Museveni���s government which, finding itself in a serious crisis of legitimacy, responds with the inherited violence of the colonial state.

Challenged by the explosion of popular mobilizations and protests, and inundated by public controversies (such as around allegations of high profile corruption), the state framed existing political formations as a threat to national security and the country���s road to progress, allowing it to shift the terrain from struggles for social justice, emancipation, and the construction of political alternatives, to�� questions of patriotism, national security and political stability.

Notably, the use of political violence in 2020/21 is not solely linked to the political turbulence caused by the election campaign. Indeed, it does not signal the failure, but rather the successful implementation of the model of authoritarian neoliberalism: using state power and coercion to establish functioning markets and defend/advance the core political-economic interests and preferred social order of the ruling actors. Without it, the very existence of the government would be jeopardized. Its constant deployment is meant to secure the maintenance and reproduction of the larger social block in power. It is the same violence the government unleashed against recalcitrant rural populations resisting state-orchestrated land enclosures and other contentious, state-led, donor-funded development projects. Human, civic, and other political rights in today���s Uganda are being sacrificed on the altar of the neoliberal model.

Day-to-day politics���election mode or not���is about the use of power. The question is what does the election violence in contemporary Uganda tell us about power and political economy, and about the relationship between capitalism and democracy in the country? It is here where most human rights-based analyses fall short.

To follow the dynamics in election-mode Uganda means to observe and come to terms with the character and impact of this neoliberal restructuring, and with the actual operations of this proto-type market society. It also means to critically think about the decades-long discursive hegemony of Uganda as a success story, which has produced a dominant set of data and self-celebratory interpretations. These conceptual hunches help to situate presidential elections in the broader context of the post-1986 political, economic, ecological and socio-cultural changes which transformed Ugandan society, polity and economy in unprecedented ways.

Against this wider background, we offer a set of analytical points emerging from a collective analysis written by more than 20 scholars from across disciplines. They are key features of the neoliberalization of Uganda over the last three decades (see the conclusion here for an extended version of the summary below).

Neoliberalization is a multidimensional process which emanates from multiple poles of power, discourse, interest, and wealth. As such, it is not simply exogenous to, or imposed on Uganda. Rather it is articulated with���and metabolized within���society and politics at many interconnected levels. In Uganda���s case, the process was a joint exercise of power by way of an alliance of resourceful foreign and domestic actors. The triad of state-capital-donors rolled out its agenda of reform in various ways over a significantly vulnerable population. It cemented structural, institutionalized, and bureaucratized forms of discipline in the state and the economy.

Economic growth has become the center of gravity, a key indicator of political success at the expense of social justice, emancipation, equality, political, and civic freedoms, and human rights. The maximizing of private profits is the dominant principle that informs policy making.

Uganda is a striking example of authoritarian neoliberalism. Sector restructuring through privatization and liberalization was often executed in an uncompromising way, with ample use of authoritarianism and state violence and with little concern for the harmful social and ecological repercussions. International financial institutions (IFIs) along with the international development sector enabled the build-up of a powerful and oppressive security apparatus and are implicated, directly and indirectly, in the growth of corruption, authoritarianism and militarization, and in a more explicit turn towards crony/rentier capitalism. Violence has been an intrinsic component of the neoliberal project, rather than its antithesis. As in other neoliberal societies, the escalation of violence has taken multidimensional forms���military, disciplinary, economic, political, cultural, and verbal. State policies (especially those that hit the poor) have unleashed systemic violence and corresponding widespread social harm. The militarization of whole villages and districts to curb dissent and protest���for instance, against large-scale land acquisitions and related displacing dynamics���has been a constant feature of post-1986 Uganda. The emerging agribusiness, oil, and mining sectors are driving this agenda further.

There are notable similarities and continuities between the neoliberal and colonial development projects, especially with regard to access and control of key natural resources and the accelerating extractive logic of capitalism. Uganda is undergoing a deep structural transformation into an extractive and authoritarian enclave where foreign interests are treating land, water, oil, forestry, and conservation areas as sinks for resource extraction.

Economic achievements (housing, road and education infrastructure, GDP growth, cheap mobile communication technologies, etc.) are uneven across classes, genders, ethnicities, and geographies, and are mobilized to strengthen national pride, making neoliberalism appear desired, especially (but not only) among the middle classes. Yet, a colonial matrix of dispossession and domination persists in the neoliberal period, reproducing neo-colonial structures of inequality and projects of subjugation through development projects, market violence, land theft, looting of natural resources, exploitation, and cultural assault.

Popular protests against the government have taken different forms and contributed to shaping important alliances among social constituents that created new political space by challenging the implementation of neoliberal development projects. Myriad social struggles are taking place around key areas of societal transformation. Social media has become a protest platform that the state constantly strives to restrict in order to control dissent and criticism of state action.

The neoliberal agenda has advanced inequalities and divisions between classes and exacerbated social injustice. Systemic elite bias and elite capture of development projects turned these into tools to advance and consolidate the power of dominant classes. Over the years, President Museveni���s rhetoric and vision for the country has been consistent and insistent on the role of foreign investors. Symptomatic of neoliberal Uganda is an acceleration of ���jobless��� economic growth, whereby much of the investment takes place in the extractive and financial sectors, with little or no linkages to local economies, with wealth captured by a plethora of actors with little societal redistribution, and with public debt at heightened levels.

Neoliberal policies have negatively impacted the most vulnerable segments of the population. The financial demands and pressures on these people to just survive and recover from ill-health for example are extraordinary. The multiple and interacting crises produced by neoliberal restructuring are often addressed by more neoliberal reform, which promotes little advancement. Neoliberal reason has become a habit of thought, a cognitive frame that shapes the way many people see themselves and others, and consequently the ways in which they act in that context.

Neoliberal discourses���from good governance to empowerment and accountability���provide a sanitizing spin to the brutal exercise of power and relentless restructuring that has locked in a capitalist social order based on increased inequality and permanent social crisis. This results in the depoliticizing of debates about development and change. Donor-led development narratives and ideologies systematically conceal the class interests behind thereforms. Narratives of free markets, empowerment, and competition among free individuals tend to conceal the substantial concentration of wealth, monopolistic tendencies, and resulting profit accumulation strategies inherent in the neoliberal economy.

The Ugandan situation is part and parcel of institutionalized neoliberal capitalism globally. There is no way out of these crises unless the key pillars of neoliberal order are questioned, and inroads towards a significant de-neoliberalization of the country are made. But where are the political actors who could push for such a change in Uganda?