Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 123

July 12, 2021

Makeshift modernity

��� Ben Okri, The Famished RoadStrange fishes and sea-monsters and mighty plants live in the rock-bed of our spirits. The whole of human history is an undiscovered continent deep in our souls. ��� We must look at ourselves differently. We are freer than we think. ��� We can redream this world and make the dream real. Human beings are gods hidden from ourselves.

���AFRICAFANTASTIKA continues to boom,��� wrote scholar Mark Bould in 2016. His words are almost an understatement today. Here, I will examine some commonly referenced reasons for the rise of African Speculative Fiction (ASF) in 2007���2008: the global financial crisis; the rise of the middle class; accelerated flows between diaspora, African America, and the continent; and phones. I argue that the last point needs more fleshing out, and suggest we look deeper at the new, technologically facilitated cultural wave in relation to the dawn of ���makeshift modernity.���

Space is the placeWhile there were only about five ASF publications in the 1990s, since 2010 the numbers have jumped to hundreds of publications per year. Neil Blomkamp���s District 9 came in 2009, followed by his 2015 film Chappie. In 2011, South African writer Lauren Beukes won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for her cyberpunk-inspired Zoo City (2010). There have been several successful anthologies, such as Lagos_2060, AfroSF, AfroSFv2, and, most recently, the brilliant Africanfuturism Anthology, published by Brittle Paper and edited by Wole Talabi. The first issue of Omenana, a pan-African speculative fiction magazine, appeared in 2014, and the magazine continues to grow stronger. In 2016, Nnedi Okorafor made headlines when she received both a Hugo Award and a Nebula Award for her novella Binti (2015). That same year, the African Speculative Fiction Society was launched at the Ak�� Arts and Book Festival in Nigeria, together with the annual Nommo award for best African speculative fiction. Lauren Beukes���s ���The Shining Girls��� (though not set on the continent) is coming to Apple TV+ in 2022 and Okorafor���s Binti is becoming a TV series on Hulu as we speak. Though the film may be divisive, I cannot avoid mentioning Black Panther and its striking characters T���Challa and Shuri. Their role in propelling both Afrofuturism and ASF onto the global cultural stage is undeniable.

First off, let me argue how excellent the rise of ASF is for everyone, but most importantly for us, the people of African descent. ���The place in which I���ll fit will not exist until I make it,��� said James Baldwin. To make it, one must first imagine it; to make change, one must first imagine a different kind of future. ASF can be linked to the decolonization of the mind in many ways: we must break the molds of colonial prescriptions, education, and decisions about Africa���s place in the world, much like speculative fiction breaks the mold of what can and cannot exist.

ASF points to an insistence on partaking in the technology-steeped global future and represents a push to actively influence that future. Furthermore, publishing and sharing tales and ideas about the future shows a new kind of optimism and self-confidence. Newfound confidence also arguably comes from stronger and more frequent connections with cousins from another planet���those in African America���facilitated by modern communication technology and faster cultural exchange. Africa is looking to African America for cool self-confidence, and African America is looking to Africa for roots and authenticity. This has been going on for a long time. Increasingly, however, African American interest has given cultural expressions from the continent a boost onto the global stage. After five centuries of the rest of the globe telling Africa its cultures and inputs are useless, those cultures and inputs suddenly find themselves at the forefront of global ���cool.��� But this time around, we might actually gain something from it.

Attack of the academicsWith success comes scholarly interest. Canadian science fiction writer Geoff Ryman has compiled his 100 interviews with African writers of speculative fiction and fantasy, and the Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry and the magazine Paradoxa are not alone in publishing special issues on ASF. In my working group CoFUTURES, we are looking at cultural expressions of speculative futures from around the world, outside of the US and UK. I am looking specifically at ASF in relation to imagined ���climate changed��� futures.

From what I have read so far, the limited scholarship on ASF is in agreement on two points: first, that science fiction from and on the African continent is in no way new, and that it is our job as scholars to fight that misconception. Many have written about this, including Mark Bould (the scholar quoted above) and Ugandan filmmaker and writer Dilman Dila. Dila talks about oral traditions and rich mythological universes, bringing in stories like that of Luanda Magere, the man made of stone, and Kibuuka, the man who could fly and shoot arrows. He points out how many societies linked ancestry to aliens, citing most famously the Dogon of West Africa and, according to his research, possibly the Baganda too (see more here).

Part of the colonial hangover is arguably a belief that westerners have dibs on speculation, on looking to the stars and wondering about it all. Or on wondering about the effects of technology, as though this very basic human inclination was completely foreign to the continent until some project sent down an iPad and people could watch Iron Man on it.

Dila���s conclusion has a strong kick to it: ���When some claim that the genre is alien to Africa, that Africans don���t consume scifi, that there is no audience, I want to ask; which African community are you talking about? When they say Africans are not ready for scifi, what do they really mean? … Africans won���t relate to Captain America, or Star Wars, or Spiderman, but they���ll relate to stories of John Akii-Bua running faster than a rally car, or to stories of trees whose branches are living bridges strong enough for buses and lorries to drive over, or, as we see in Nollywood films, they pay to watch alternate worlds spiced with juju fantasy.���

So that is one battle that creators of ASF are waging. Second, it is agreed that the boom of what can perhaps more correctly be called new, published written work���the video games and films circulating globally���began around 2007���2008.

���Boom! What was that?���But the reasons we have settled on this timeline need to be examined further. According to academic Peter Maurits, the first reason is the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007���2008. He calls the GFC a fall and rise moment, both for global capitalism and for TINA���the sense that There Is No Alternative. In that moment, Maurits argues, lots of other possible systems were imaginable, and many people were even inspired to fight for them. This was also the start of the ���Africa rising��� moment, when public discourse embraced the idea of a shift of economic centers away from the West.

A second reason often listed is the growth of the middle and upper classes. The growth of the middle class allows content producers to imagine audiences at home. Writing for African readers completely changes the game, both for writers and publishers. Today, writers are daring to write less apologetically from ���under their own stars,��� and there are fewer creators now than before who feel pressured to ���explain Africa��� to imagined western audiences. Interestingly, writer Ezeiyoke Chukwunonso blames the third wave of African writers for setting too rigid and constraining expectations on what African literature can and should be. ���African literary fiction,��� he writes, ���is again awakening from the coma it had been in after the era of Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ng��g�� wa Thiong���o and other writers of that generation.��� Writers have been expected to be political or social activists more than anything else; as a result, a lot of literature resembles pamphlets with characters. ���African writers are traumatized,��� writes Dila. ���They forever have to defend their work. If it���s not someone questioning why they are not tackling the problems of their societies, it���s someone wondering why they only write about misery and gloom in the continent.��� Whether or not one agrees, having these conversations is another reason why the rise of ASF is so important.

To this can be added the effect of vastly accelerated global flows, which allow diasporas to more immediately participate in cultural production. Undeniably, a lot of those producing ASF have studied or lived outside of their home countries. The influence of African America is no less undeniable here, including the explosion of Afrofuturism onto screens all over the world. This is both the ���coolness��� factor���Beyonc�� with tribal markings and everybody walking around making the Wakanda sign���and the ideology behind Afrofuturism, which is based on a construction of the future as a political project. Again, this shift is related to audience: Afrofuturism and ASF communities on the continent seem extremely conscious of conceptual questions like what kind of point of reference are we writing from, and whom are we writing for?

Through the black speculative imagination comes an assumption of self-respect and confidence which can translate to real-world effects in the present���sometimes phrased as ���taking what���s ours.��� For example, I believe that the massive solidarity shown for Black Lives Matter around the globe (even here in Norway) can be explained in part by the recent rise of Afrofuturism���s popularity in the global imagination. That solidarity translated into feet on the streets. These feet then become political headaches, which finally result in policy changes and statue replacements. The future matters.

A glorious new dawnA third reason, linked to the other two, is what Maurits calls the ���conditions of possibility,��� i.e., the rise of democratizing technological innovations like cell phones. I read this argument again and again, in different contexts: the reason for something happening is that Africa now has phones. But I am always left with a feeling that this argument does not quite cover what is going on. Phones are coming, yes, and they have changed a lot of things���at least for the middle class. But this again sets communities in a passive role, as mere receivers of technology. How are the phones being used, and what does that tell us in cultural studies? Is technology bringing Africa into the digital age, in the way the term is usually understood? Is it ushering in posthumanism, modernism, postmodernism? Is it final proof that the continent is leapfrogging industrialization?

To take the first question first: it is not reasonable to argue that the African continent is in the same place as the global North when it comes to posthumanism or digital lifestyles. But it does not seem quite right to say that it is ���behind,��� either. The latter statement would suggest that the continent is ���developing��� both on the same trajectory and toward the same position as the global North. That doesn���t seem right. Pennsylvania State University Associate Professor Magal�� Armillas-Tiseyra writes about the African continent being framed globally as a part of Ferguson���s ���global shadows,��� spaces of absence or negation. The shadow space ���haunts��� the West, yet is instrumental for its self-conceptualization: ���There is, after all, no ���civilization���, ���modernity��� or ���development��� without its opposite.��� Part of the decolonial global paradigm shift I have advocated for elsewhere is rejecting the shadow narrative and insisting on filling those spaces of perceived absence.

In the case of the second and third questions: what should we call the new cultural wave facilitated by new technology? I would argue that on the African continent, if we must suppose a linear trajectory and if it must be compared to European history, both early industrialization, modernism, postmodernism and post-postmodernism exist all at once. The expected timeline is collapsed. There are parallels to each, and yet this is something new.

The best term I can come up with to try and describe the new cultural wave is makeshift modernity. Modernity, because the emphasis is on self-definition, advancement, technology, and change. This emphasis reveals a sense of optimism about technological possibilities, leading to a perceived gulf between this generation and previous generations (that of third-wave writers, early postcolonial leaders, and theorists). It cannot be called an ���African version of modernity,��� defined against the West, as with Geoff Ryman���s comparison between the Africa rising moment and England in the Elizabethan age. This is because it is an entirely different meal, though cooked with many of the same ingredients: urbanization, conflict and war, an enormous and widening gap between rich and poor, massive amounts of new opportunities enabled by groundbreaking technologies, a sense of gritty optimism, a spirit of cutthroat entrepreneurship and innovation, a new global sensibility and space in the world, and a growing confidence in taking up that space.

The ���makeshift��� encapsulates all the innovative, often improvised ways that both technology and culture are being used and reused. In the words of Jean and John Comaroff, this is ���a retooling of culturally familiar technologies as a new means for new ends.��� But it is not only hardware that is being rethought and reappropriated, it is also modern sensibilities, global culture, and pick-and-choose cultural concepts from around the globe.

Additionally, ���makeshift��� emphasizes the agency of the practitioner. It highlights the temporality of that modernity, of everything being a temporary make-do solution. Indeed, it underscores how entire lives are being lived with make-do solutions, in lieu of something better; how people are constantly looking toward a better condition and how cultural movements are steeped in a sense of ���one day��� or ���heading towards a better place.���

Dilman Dila points out how having this kind of hopeful other reality in the mind can cause what he calls a kind of ���schizophrenic��� state. ���It hurts,��� he writes, ���to daydream of better things. It hurts even more to write about it, for at some point I begin to feel like afrofuturism is becoming something like a mind-control drug, something like a religion that makes you endure a horrible life with promises of a paradise after death.���

���Nkoloso, launch the second rocket!���In this post, I have looked at some commonly referenced reasons for the rise of ASF: the global financial crisis and the momentary disappearance of TINA; the rise of the middle class and accelerated flows between diaspora, African America, and the continent; and phones. I have argued that the last reason often needs more meat to it���what are phones being used for?���and suggested one possible answer: that they are part of facilitating the age of makeshift modernity on the continent. Makeshift modernity is no derivation or exercise in ���catching up��� with Europe, but an entirely new condition, which in turn is facilitating exciting new cultural production.

Dila and others have expressed worry about the global interest in ASF. They fear that it will become too popular and become watered down, like the horror genre. Whether or not this will happen remains to be seen. I would argue that with new global interest, the tables may have shifted some, yet they have not turned. I strongly doubt whether this will translate into any meaningful change in the lives of the average African, economic or otherwise. In Brittle Paper���s Africanfuturism Anthology, there is a great story by Tlotlo Tsamaase extrapolating this phenomenon. In the story, we follow a young woman who gets a great new job at a tech company. Yet her mind is slowly being taking over, and it turns out (spoiler!) that the international company is ���mining diversity��� directly from its Botswanan employees, drawing from them patterns for fashion, ancestral connections. It is quite gruesome, yet makes an interesting point. The effects of being ���cool in the USA��� need to be further explored.

In my opinion, the great global gaze comes and goes, without really leaving many tangible marks. What really matters is what ASF is doing on the continent. ASF has already made its mark as part of the next phase of decolonization. We have all looked back and agreed that, for several reasons, the past 500 years were very bad. Now it���s time to ask: what���s next?

The mother of all failures

Photo by Francisco Ven��ncio on Unsplash

Photo by Francisco Ven��ncio on Unsplash In Angola, the pandemic is the mother of incompetence. In his state of the nation speech, President Jo��o Louren��o declared the COVID-19 pandemic responsible for all the failures of 2020. But it was less the pandemic itself than incompetence in state management that caused problems.

First, let���s discuss corruption, a close cousin of incompetence. Currently under an agreement with the IMF, the Angolan state should be more careful in how it manages pandemic related funds. In July 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a piece called ���Corruption and COVID-19��� that called for transparent management of the pandemic. The pandemic crisis would not, the IMF said, sideline its governance and anti-corruption work. The IMF emphasized that the pandemic demanded broad intervention by governments but also advised that ���governments need timely and transparent reporting, ex post facto audits and accountability processes, as well as close cooperation with civil society and the private sector���.

Despite positive reviews from the IMF, the Angolan state has not been as transparent as possible in its accounting nor does it have good systems of oversight in place.

Declarations of a state of public emergency and of public calamity in March and May 2020, respectively, offered rare moments when the state openly discussed the costs of COVID-19. Following pressure from journalists and widespread rumors, the Minister of Health, Dr. S��lvia Lutucuta, estimated the total cost per COVID patient in April 2020 at about 16 million kwanzas (nearly $25,000). In June 2020, the former Minister of State and Head of the President’s Security Office, General Pedro Sebasti��o, presented the first and only report on the costs of the fight against COVID-19 to the Angolan parliament, arguing that the executive had spent (to date) the equivalent of $69.4 million. Finally, during his speech at the UN general debate on COVID on December 19, 2020, Angola’s president presented the costs at $164.6 million, meaning the expenses had more than doubled in a 6 month period. The media outlet TVRecord Angola calculated the cost per patient at $10,715. Even if the cost per patient had dropped, the cost per patient in Angola is six times higher than in other places in the world, like Portugal.

The numbers are big and transparency requires studies with greater detail. Stuck between the precedent of deference to executive powers and the gray areas of legal interpretation, Members of Parliament have not audited the state���s reports. This despite nearly daily complaints about the involvement of high-level government officials in scandals around the importation of PPE; the construction of facilities to house field hospitals; the lack of disposable material in public hospitals; and insufficient examinations for doctors. The presence of PPE sold by street vendors in Luanda fuels speculation. Given that local industry is producing goods and the state has a monopoly on importing PPE and external support, the lack of masks and gloves in public hospitals while they are for sale on the street is unacceptable.

It is not surprising that Transparency International ranked Angola in the 142nd position (of 180 countries) in 2020. A study that analyzed the promotion of transparency in sub-Saharan countries established ten indicators, of which Angola has achieved none.

In addition to a lack of transparent management of COVID related resources and the incompetence demonstrated in the production and distribution of PPE, the state has also failed to ensure public security. In the first two months of implementing the state of emergency, security forces killed more people than COVID-19. Political violence is more deadly than the pandemic.

The death of a pediatrician, Dr. S��lvio Dala, a victim of police brutality in September 2020, sparked a wave of national repudiation including protests by doctors. Other citizens have been killed, shot or beaten to death for not wearing masks, even when they were alone in their cars.

Many measures taken in Angola lead us to believe that we are faced with decision makers who are unaware of the reality of most Angolans. The journalist Jo��o Armando in an editorial published in April 2021 wrote that “the fight against corruption is fundamental, but the fight against incompetence too.” He notes that those who are competent ���are more interested, offer more opinions, want to make more changes, but end up being called ���revolutionaries��� and are pushed aside.��� Instead we get a game of musical chairs in which incompetent leaders fail, but then are re-assigned to different positions in the state.

Some failures combine corruption and incompetence. The regime tries to influence and assert itself within professional organizations and unions in order to control the masses. This put the Angolan Association of Doctors, who accepted the state���s story that Dala had died from pre-existing conditions, and the Doctors��� Union, who blamed police brutality, at odds over�� Dala���s cause of death. As a result slogans like: ���Out with S��lvia Lutucuta,��� the Minister of Health, were heard during the demonstrations against the death of Dr. S��lvio Dala in September 2020.

Corruption, manifest in the regime���s refusal to let the Angolan Association of Doctors act independently of state influence,was also visible in how the state has treated Angola doctors as a professional class during the pandemic.�� Doctors in the union criticized Lutucuta and the state over pandemic-related policies that marginalized Angolan doctors at a moment when their expertise was most needed. When 244 Cuban doctors arrived in Angola to help in the fight against COVID-19 across the country, it created a wave of discontent among doctors, as Angola has many doctors with the same qualifications but who find themselves unemployed. The wage gap between Cuban and Angolan doctors created more tension: Cubans receive salaries ten times that of Angolans. This is an example of the commitment and the ���blood debt��� that the MPLA has with Cuba, a country with which it has established privileged relations in the areas of defense, security, education, and health, after Cuban troops helped guarantee Angola’s independence on behalf of the MPLA.

Nurses, the largest group of health professionals in the country, considered going on strike in February 2021 to demand better safety conditions in health units and an additional month of salary. In the midst of the pandemic, doctors and nurses and the professional organizations and unions that represent them have been left hanging by the regime’s ineptitude.

The problems of governance associated with the pandemic reveal deeper, longer running troubles. The regime has never looked at public health as a potential investment and part of the pact between state and society. Instead what we have are parallel systems of public and private healthcare in which the political elite, starting with the president himself, get their medical services from private clinics and, often, outside the country.

July 9, 2021

The lessons of history

Nairobi. Image credit Sterminator via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Nairobi. Image credit Sterminator via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. In a bid to try and keep power between an elite group of male politicians, Uhuru Kenyatta and former opposition leader Raila Odinga are pushing for the adoption of a “Building Bridges Initiative” that would require changing the 2010 Constitution. While a recent court ruling deemed this bid unconstitutional, and there is little public support for their ���new Kenyan nation,��� Uhuru draws on a number of narratives to legitimize this effort, including, as Githuku and Maxon argue, fables about constitution making in colonial Kenya. This post is from our partnership between the Kenyan website The Elephant and Africa Is a Country. We will be publishing a post from their site regularly, curated by our Contributing Editor Wangui Kimari.

The rapprochement of March 2018 between Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, now famously referred to as ���the handshake���, which kick-started the BBI consultation process and culminated in the Report of the Steering Committee on the Implementation of the Building Bridges to a United Kenya Taskforce Report, is emblematic of the rough-and-tumble that is the country���s tumultuous political history.

The report of the taskforce provided long-awaited principles and recommendations for the construction of ���a new Kenyan nation,��� including several changes in the current constitution. But a portion of Kenyatta���s Mashujaa Day speech on 20 October 2020 suggests a need for caution. It was rather ahistorical, and unfortunately, oblivious of numerous imposed top-down attempts at constitution-making and other general attempts to foist government declarations or policy documents on ordinary people.

Hoping to, perhaps, prepare the ground for elite-led changes to the 2010 constitution, the president���s speechwriters sought to arrive at this end by using a portion of the speech to remind citizens that constitutions are not static but often change. This process, the writers asserted, should be a product of ���constant negotiation and renegotiation of nationhood���, and building a constitutional consensus. The italicized end of the president���s paraphrased speech is instructive, and erroneous in the light of the country���s constitutional history.

Moreover, referring to the Steering Committee���s report, the speech sought to prepare the ground for constitutional and other changes by calling for the building of ���a sense of national ethos��� that will emphasize belonging and inclusion. This, as the committee rightly observed, must include ���documenting our history honestly���. But not so the president as per his speech, notably.

Most historians and citizens would agree that a key element in such an honest history must be factual accuracy regarding past events and interpretations solely based upon such facts. It is this latter point that the speechwriters disregarded in putting forth an account of constitution-making. While correctly emphasizing the need for a constantly moving exercise requiring, again, note, a consensus among political leaders and wananchi, the examples from which they drew during the colonial era demonstrate no such thing. Neither the Lyttleton Constitution of 1954 nor the Lennox-Boyd Constitution (announced in 1957 and implemented in 1958) were the product of a consensus.

First, both constitutions were imposed by the secretaries of state for the colonies after whom they are named, and the terms were dictated by the then governor Sir Evelyn Baring and his advisors���does this ring a bell yet? Elitist. Moreover, the Kenyan population, and particularly Africans, had no input whatsoever in the Lyttleton Constitution, which was imposed even though all six of the Africans appointed to the Legislative Council (LegCo) refused to accept the Lyttleton plan. That plan was not about inclusion at all, but its main purpose was to create a multiracial council of ministers in which, in the early stages of planning, no African would hold a portfolio. Lyttleton eventually agreed for one ministry to be headed by an African, but it ought to be recalled that the constitution provided for three European settler ministers to join the two settlers already holding the important portfolios of finance and agriculture.

The key group for Lyttleton and the governor in Kenya���s racial politics of the time was thus the European settler politicians. The acceptance of the plan by most of them constituted Lyttleton���s success and left the African population, among whom none could vote for representatives to the Legislative Council, totally excluded. While there was little inclusion, African LegCo members did gain a promise from Lyttleton that the colonial government would take steps to provide for African representation.

The promise, imposed without the agreement of settler representatives, led to the first African elections of March 1957. The eight African Elected Members (AEM) immediately launched a campaign for change that would produce a more inclusive constitutional order (European voters elected 14 LegCo members and Asian voters 6). Amazingly, Kenyatta���s speechwriters cast this as consensual by the statement that if the Lyttleton Constitution ���was wrong, it was made right��� by the Lennox-Boyd Constitution. This interpretation has no basis in fact as all the European settler members of LegCo opposed the AEM campaign, which included a refusal to accept the two ministerial positions reserved for Africans in 1957.

Significantly, most Asian political leaders came to support the AEM demands. Just as in 1954, then Secretary of State Alan Lennox-Boyd, in response to the AEM campaign, flew to Nairobi in late 1957 to implement constitutional changes suggested by Baring. He was prepared to increase the number of AEM in the LegCo and determined to make them accept ministerial portfolios and introduce what came to be known as specially elected members to the LegCo. AEM rejected these proposals, including the six additional LegCo seats for Africans and the creation of a council of state. Convinced he knew best, and that the only views that mattered were those of the European settler population, an infuriated Lennox-Boyd went ahead anyway, giving up his attempt to build consensus and ignoring the opinions of most of the Kenyan population. The result was continued political exclusion, and a period of on-going political tension and racial hostility.

The AEM boycott of the Lennox-Boyd innovations (except the six additional LegCo positions) by April 1959 forced the British government to accept that the Lennox-Boyd plan had become unworkable. The solidarity of the AEMs won the battle. But it was a glaring distortion of history to single out Oginga Odinga, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, and Masinde Muliro as heroes in the president���s speech while at the same time seeming to say that as AEMs they consented to the changes desired by Lennox-Boyd and Baring.

Nothing could be further from historical fact as the archival records of the discussions leading to the Lennox-Boyd Constitution clearly illustrate. Asian political opinion supported the need for constitutional change, but several of the European elected members of LegCo did not favour discussing constitutional changes. The years 1959 and 1960 brought an end to consensus among the settler political elite. The first Lancaster House constitutional conference (LH1) thus brought together Kenyan LegCo members who viewed constitutional change very differently with few apparent grounds for agreement.

While the settlers were divided, the 14 AEM delegates were united in a firm stand in favor of a rapid democratic transition for Kenya leading to self-government and independence within a short period of time. European delegates were, by contrast deeply divided, with the right-wing United Party favoring continued colonial rule and the New Kenya Party (NKP) delegates favoring a gradual transition to independence, and a multiracial executive and parliament with reserved seats for Europeans and fewer for Asians.

The new Secretary of State Iain Macleod, like his predecessors, was unable to find or facilitate consensual agreement on a new constitution. Contrary to the claims of the speechwriters, therefore, there was no common ground negotiated among the delegates. Macleod moved beyond this stalemate by putting a set of proposals before the by-now weary delegates that they were required to accept in full or reject. This was a quite different approach than in 1954 and 1957. Macleod then cleverly maneuvered the African, Asian, and NKP delegates into acceptance of his terms that went some way toward meeting the demands of African delegates, but not others, for instance, universal suffrage, the appointment of a chief minister, and the release of Jomo Kenyatta.

In a real sense, for that reason, the LH1 constitution was an imposed one, and indeed many living in Kenya at the time rejected it. Nonetheless, the AEM accepted it as ending European settler political predominance in Kenya and the new plan as a step on the way to independence. Over subsequent months, however, the consensus that had united the AEM disappeared as bitter divisions developed regarding the type of constitution Kenya should adopt as an independent nation.

The competing visions of the two political parties, KANU (a unitary republic) and KADU (majimbo or a federal republic), were difficult to reconcile. This formed the background for the second Lancaster House conference in 1962. The absence of agreement on the basic constitutional structure was clear from the first meeting, and again, a British colonial secretary was forced to impose a settlement that did not take the form of a constitution but of a framework on which a coalition government in Kenya would work out the final document. This took a year and required the British government to draft the self-government constitution and decide key provisions because the KANU and KADU ministers could, well, not agree.

This brief narrative serves to make it clear that there was no consensus here anymore than with the three previous constitutional talks. It is thus, rather puzzling, if not amusing in an odd way that, in a desire to promote negotiated and consensual constitutional innovation under the auspices of the BBI in the year 2020, and by the president no less, these should be the examples put before the Kenyan public in justification. Rather, an accurate account and analysis of earlier or past constitutional innovations demonstrate very clearly the need for wide consultations among the populace (unlike the episodes described above where only a narrowly defined political elite participated) and a broad-based consensus.

In other words, the same message can be got across to the public by relating the correct facts. As the speechwriters noted: ���The more we ponder our history in its truest form, the more liberated we become.��� It is always best to heed the lessons of history, not to ignore it altogether, and repeat the same grievous mistakes.

July 8, 2021

Can we reclaim football from below?

Photo by Patrick de Laiv, Creative Commons

Photo by Patrick de Laiv, Creative Commons In Europe, we recently saw mass protests by the supporters of Liverpool, Manchester United and other English Premiership clubs against the proposed European Super League. This action sank the proposed elite League and demonstrated the potential power of supporters, which reached all the way to the inaccessible boardrooms controlling European football.

In South Africa, such action is unimaginable. The famous, popular, and solidarity-based Iwisa Charity Spectacular tournament was killed by the commercial interests of the once-dominant Orlando Pirates and Kaizer Chiefs. And there was no action by football supporters. The season-opening tournament existed for more than 15 years and participation in it was always based on the popular vote of at least two million football supporters each year determining which four teams competed. The entire proceeds were given to ���charity.���

Where there was some kind of mass action was a limited march in early May by Chiefs fans to demand better performance from their team. This is an action that Pirates fans threatened to undertake for the same reasons, but failed to execute.

It is the power of money over football that has led to the decade-long domination of the Premier football League (PSL) by Mamelodi Sundowns. Sundowns are financed from the mining-based profits and wealth held by the family of Patrice Motsepe, whose companies largely pay starvation wages to tens of thousands of mine workers.

This commodification of football can be seen elsewhere too���the capture of TV rights by the Naspers-owned DSTV, the dependence of professional football on sponsorships by capitalist companies, and the control of football clubs by unelected and unaccountable families and private companies.

As implied above, the reality of commodified and elite-controlled football is taken as given and unchangeable by the majority of fans. This hegemonic reality is actually in direct contradiction to what had existed at earlier moments of our history.

My club, Orlando Pirates, was not known as the People���s Club for a trite reason. It was precisely because its supporters attended meetings en masse and held significant weight in the decisions made about the direction of the club. Earlier, the club even had a more community character when the old Orlando Boys Club, from which Pirates originated, was controlled by a community-elected and women-dominated committee.

The same was the case for Moroka Swallows, the early Sundowns, Witbank Black Aces, the defunct Pimville United Brothers and many others. Importantly, this culture of working class control of a club was not the case with Chiefs, which has always centered around the figure of Kaizer Motaung.

The rolling back of popular control of these clubs was often bloody and deadly. The currently�� dominant mafia would not tolerate any opposition to its rising control of these clubs. It is a great omission that little has been written or recorded in film about this aspect of South African football history.

The only semblance of fan participation is in the Supporters��� Clubs that leading clubs operate. Through country-wide branches there is limited exercise of supporter power and voice at the most basic level. However, there is little�� autonomy and ultimate subordination to the marketing divisions of the actual football�� club. Supporters still do not have any say, voice or power in the ownership, control, and administration of the clubs.

The mafia-style control of South African football has led to the disaster that is the national men���s team for more than 15 years now. This failure largely stems from the absence of a broad-based, resourced, dynamic, and innovative football development agenda. Instead, the mafia at the helm uses its power to primitively accumulate wealth, which takes away from bottom-up development.

When the PSL first negotiated TV rights with Supersport in 2007, it decided to pay a R70 million bonus to a three-person committee (Irvin Khoza, Kaizer Motaung and Mato Madlala) that negotiated the R1,6 billion deal. They did this instead of meeting the demand from lower tier clubs to increase the monthly grant from R50,000 to R200,000. This was coupled with another demand to increase voting powers for these clubs from two to five.

The South African Football Association (SAFA) scored a windfall of R685 million for football development from hosting the 2010 FIFA World Cup tournament. FIFA transferred this amount into the 2010 FIFA World Cup Legacy Trust which was established by the international organization and SAFA to promote and develop football. The most logical thing was to start at school level.

Despite this windfall, SAFA has never initiated any such grassroots development program. In many townships and rural villages, school football is not supported at all. There are no coach development programs, schools do not have budgets for playing equipment, transport costs to games are self-financed by each school, and school sports grounds are poorly developed. Moreover, SAFA has not publicly accounted for how the FIFA windfall was used. The only reported activity was the R137 million used to build SAFA House next to the famous FNB Stadium in Soweto. Already by 2014, SAFA financial statements confirmed a loss of R55m for that year.

Instead of promoting real bottom-up development, the mafia dangles the false promise of commercialized football as the path to its development. Even university-based clubs are encouraged to secure private sponsorships in the same way as varsity rugby and second- and third-tier and lower division clubs, which have far fewer resources than the premier division. As a result, many of the newly enriched Black Economic Empowerment beneficiaries have sought ownership of these lower tier clubs as a demonstration of their newly arrived status. Some have taken short cuts by buying premier clubs��� statuses. All this perpetuates the domination of commercial logic over broad-based development.

The underdevelopment of women���s football is another symptom of the mafia approach to the game. If women���s football proves to be commercially viable, it is likely that the same mafia will capture it in order to continue with accumulation and not for the development of the women���s game.

Despite the limits of the Supporters��� Clubs, the seed for change in football actually lies in them. They can become an important platform and voice in the necessary struggle to democratize the game and reclaim it from the elites. This agenda can start with the demand for the return of the Charity Tournament, creating institutional space for the role of supporters in the ownership and control of clubs, and the redirecting of resources to lower level football development.

Beyond the clubs, there is much work to do to raise the banner of school football development. This is where teacher trade unions, student organizations and parents need to be better organized around the revival of school sports in general. It is on that basis that they can be an organized voice putting mass pressure on both the state, the football establishment and private companies for the redirection of resources away from the mafia into school sports.

These ideas can only become real with much activist effort and the effective organization of a radical sports transformation agenda in supporters clubs and in school sports. This would promote a more sustainable and democratic foundation, which would, in turn,guarantee quality and success of South Africa���s national teams in the long term.

July 7, 2021

One Zambia, one nation

Zambia���s inaugural president, Kenneth Kaunda, died on June 17, 2021, at the age of 97. From the early 1950s onwards, he led a nonviolent liberation struggle against British rule, eventually forging independence in 1964. In power for the first twenty-seven years of Zambia���s independent statehood, Kaunda leaves a controversial legacy. He abandoned multiparty elections in 1973, ruled as an authoritarian leader for the next eighteen years, and was the architect of disastrous economic policies that compounded the already significant levels of poverty in the country. However, Kaunda should also be remembered as a leader who was instrumental in guiding Zambia through its formative years, doing so in the absence of the wars or mass atrocities that blighted many of its neighbors.

Kaunda���s role in steering his country away from instability and mass violence���especially in the first decade of independence���is particularly noteworthy given the challenges at the time. His own stamp on state building helped to navigate these tensions: he shaped a new national identity that transcended ethnic or tribal affiliations, neither favoring nor scapegoating any group. Kaunda was acutely aware that the new state���with its borders artificially and arbitrarily constructed by its former colonial occupiers���was in peril of fragmenting through power struggles along tribal and ethnic lines. Referring to the dominant language groups, he reiterated the gravity of this new national identity in his 1967 memoir: ���with any luck,��� he wrote, ���this generation will think of itself not in tribal terms as Bemba, Lozi or Tonga, but as Zambians. This is the only guarantee of future stability.��� Kaunda thus seemed to be keenly aware that ideology can act as a catalyst as well as one of the most important restraints on mass atrocities; his humanist perspective fostered the latter while other leaders in the region chose the former.

Kaunda backed this principled stance with action during the first decade of independence, when his governing party, the United National Independence Party, began to fragment into factions based on ethnolinguistic differences. Kaunda frequently shuffled ministerial portfolios between factions and often changed personnel in all departments of the public sector���all in an effort to prevent the possibility of ethnolinguistic differences and tensions becoming formally entrenched within the new state. Throughout the 1960s, this constant reshuffling was effective in maintaining a power balance between the country���s different groups; but by the end of the decade, escalating tensions between these factions led to some forming breakaway parties on the basis of ethnolinguistic differences. This prompted Kaunda to centralize power and ban opposition political parties, forging a regime that was increasingly intolerant of opposition voices. Zambia, however, avoided the large-scale violence that some of its neighbors experienced. Although populations in dictatorial regimes are more at risk for mass atrocities than populations in democracies, Kaunda���s decision to centralize power and prohibit opposition parties was motivated���at least in part���by a desire to avoid the formal entrenchment of Zambia���s ethnolinguistic tensions.

In making this decision, however, Kaunda provoked a whole new set of challenges as an authoritarian leader. It wasn���t until 1991 that he lifted the ban on opposition parties, ushering in a transition toward a new phase of democratization. This was done under duress in the context of long-term economic decline, IMF-imposed economic reforms, and increasing dissatisfaction with his regime. Yet even this transition was largely restrained. The opposition movement itself (the Movement for Multiparty Democracy, or MMD) was a broad coalition that embodied Kaunda���s own vision of a Zambia that transcended ethnic and tribal difference. When the MMD registered as a political party and won the 1991 election, Kaunda conceded defeat and transferred power without contestation. While so many other authoritarian leaders opted for a violent response to the contestation of their power, Kaunda chose not to cling to power at all costs.

Even during Zambia���s phase of one-party rule from 1973 to 1991, Kaunda���s legacy of state building stands in contrast to the violent exclusionary tendencies of many regimes in the region. Although he centralized power, this was in part a response to a belief���shared by many leaders across the African continent in the 1960s and 1970s���that multiparty elections were divisive. So while research has shown repeatedly that established democracies tend to be safer for their inhabitants than democratizing or dictatorial countries, Kaunda actually seems to have used his dictatorial rule to steer the country away from the preconditions of mass violence.

Kaunda was able to shape the nation���s identity because dictatorial leaders, through their sway over the dominant narrative of their societies, can be particularly influential and shape how a population may think or act. The way in which Kaunda chose to do so was, however, extraordinary. Oftentimes, dictatorial regimes will use a destructive and exclusionary ideology, as it is through the definition of the ���other��� that the in-group can be defined and united. Creating such a cohesive in-group can have positive effects for leaders who tend to be more respected, but it can also enhance schisms and cause polarization or, even dehumanization, which can be conducive to massive violence. Populations are particularly likely to turn to leaders with such destructive ideologies when their life conditions are difficult; as people look for ways to understand their reality and search for someone to blame. Kaunda���s feat of uniting the nation, without exploiting ethno-linguistic tensions, is, therefore, even more noteworthy given the real and many risks for identity-based divisions to become entrenched in the first three decades of independence. Though far from perfect, Kaunda���s repeated call of ���One Zambia, One Nation��� resonated strongly, and established a precedent of stability and inclusion when so many other post-colonial African states went down more violent and exclusionary paths.

July 6, 2021

Life as young black men in Johannesburg

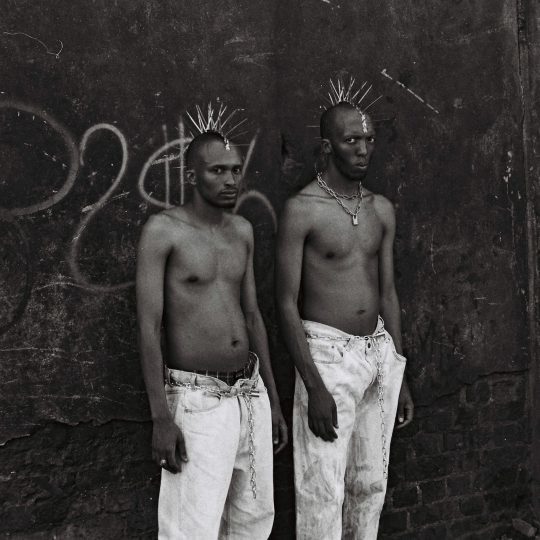

Cover art from Stiff Pap's debut album, TUFF TIME$. By Unathi Mkonto.

Cover art from Stiff Pap's debut album, TUFF TIME$. By Unathi Mkonto. What is the role of the artist in society? As my father once put it, ���It���s the artist that exposes the hypocrite in society. It���s the artist that exposes the exploiter, and the exploitation. It���s the artist who looks at people at ground level, and asks: what are your dreams and hopes?���

Which is to say: artists reflect society around them. There is an especially potent power in art that does this while also daring to show that the world is, in fact, changeable. With their debut full-length project, TUFF TIME$, South African duo Stiff Pap have created an intensely vivid snapshot of life as young black men in Johannesburg, set to the backdrop of a global pandemic still raging on a local level. The album�� is both reflective of their context and defiantly hopeful of something better.

The�� album���s ten tracks showcase the entire spectrum of Stiff Pap���s sound: a conscious ferment of hip-hop, electro and gqom colliding with a punk sensibility into a shape that they have called post-kwaito. The timing of the release is entirely apt, with a third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic cresting over South Africa. Stiff Pap are reckoning with the apocalypse at the door, and this is an urgent reminder that music is not just an escape.

���It���s important for us to acknowledge the realities of what it���s like to be in South Africa during a time like this,��� explains Jakinda, one half of Stiff Pap and producer of the beats that lead vocalist MC Ayema Problem rhymes over. ���We had to be what we think artists should be, and that is to reflect the times. We felt like it was important to use our art, use our platform, to express the feelings that we���ve always had���because we���ve always really been political people, but we���ve never really expressed it this much in our music. We felt that now is the time for us to speak more about that, because things are really bad right now in this country for young people, and we wanted to be a voice for the youth of South Africa, for young black people who are struggling right now. Because it is tough times. It���s tough times being young and black in South Africa.���

Having met as students in Cape Town, Jakinda and Ayema���s music quickly started a buzz in the underground, earning them some time in the city���s Red Bull Studios. They knew they would have to move to Johannesburg to further their careers; but just as they did so, the pandemic hit, sparking a reimagining of their artistic output.

���Now life hits you,��� explains Ayema. ���So most of the lyrics, and most of the ideas, and even the energy is based around the context of us being in Johannesburg, and having to live in a South Africa that is failing us.���

���We had to be about the times,��� Ayema continues. ���And especially when Covid hit, the impact of a failing government hit us hard. So it���s based on that. And also, as Jakinda said, we wanted to be the voice of the disgruntled youth of South Africa.���

The project is paired with a short film, ���TUFF TIME$ NEVER LAST.��� The film is a fitting centerpiece that crystallizes the howl at the heart of this album���how hard life has been during the pandemic and how the South African government has let people down when, as Jakinda bluntly asserts, ���things are basically going to shit.��� Both Jakinda and Ayema knew exactly what they wanted the short film to be: punk and gritty, grounded in the Jozi CBD, reflective of the group���s rebellious sound, and, most importantly, imbued with the energy of being young, black, and progressive. They also knew who might best bring their idea to life.

Director Meghan Daniels met Jakinda during the Fees Must Fall protests in Cape Town in 2015. ���I had arrived at a protest and saw him across the street,��� Daniels remembers. ���We asked where the other was going and headed there together. We first collaborated a little while after that.���

Because Daniels didn���t have access to gear at the time, they experimented with cell phones, laptop cameras, and screen recordings, creating layers through photobooth on a laptop and producing art that spoke to ���a hyper technology and information age.��� The end result was a music video for Stiff Pap���s song ���NNNEWWW.��� ���It was pure experimentation and play,��� Daniels explains.

Skip forward a couple of years: as Stiff Pap were toying with the idea of pairing their new album with audiovisual accompaniment, Daniels was the obvious choice to direct. ���Meghan was someone we enjoyed working with, and someone whose work we really admire,��� Jakinda tells me. ���So it was a no-brainer.���

���This narrative and project is not mine at all���it is entirely Ayema and Jakinda���s,��� Daniels insists. ���My role as a director was to do whatever I could to help bring this to fruition.���

Finding the right director, as it turned out, was the easy part. With a tiny budget to work with���Daniels was originally going to shoot the project on their camcorder���the group was pushed to think creatively in order to achieve their vision. ���For example, we had permit and time limitations and couldn���t physically walk through all the streets we wanted���so we turned a taxi into a mobile stage and used that as a conduit to explore the streets,��� Daniels explains. ���We also made use of digital collage to create scenes we couldn���t shoot.���

���Ayema and Jakinda wanted a ���documentary feel��� to the piece, and so we utilized various equipment and multimedia to emulate this: shooting on a cellphone and having a floating camcorder on set that anyone could use to shoot, enhancing the collaborative nature of the film.���

The remarkable result is a punked-out odyssey through the pawnshops, cash-for-gold exchanges, betting halls, Spazas, scrapyards, and urban decay of central Johannesburg, smash-cut with collaged news headlines, service delivery protest footage, and the ubiquitous flyers promising solutions to all a city dweller���s social, medical, and sexual needs. It looks like a fever dream South African grindhouse zine and sounds like Vangelis���s ���Blade Runner Blues��� unspooling through the Kenwood in your cousin���s CitiGolf.

The short film encapsulates the beating heart of Stiff Pap���s latest work. TUFF TIME$ is a semi-autobiographical story of rebellious black youth in Johannesburg���s inner city���of rebelling against the broken system that South Africa���s born-free generation has inherited.

���Through TUFF TIME$, we express the rage, pain and joys of moving to Johannesburg in pursuit of our dreams,��� the duo���s artistic statement for the project reads. ���We���ve always been inspired by the resilience and creativity of Johannesburg���s inner city youth. We���re just young artists trying to do what we can with what we have to create a better life for ourselves and our families. In our eyes, this city epitomizes that. It���s not pretty, it���s rough and it���s scary but through it all it���s beautiful. We���ve learnt a lot, we know who we are and we know what we want.���

There is an urgency to Stiff Pap���s raging against the machinery of classism, racism, and economic inequality, and TUFF TIME$ serves as a rallying call for radical change. It���s a story boldly told through the lens of the group���s growing audiovisual universe. Through this journey they find healing, struggle, and perseverance, fueled by the hope instilled in them by the generations who fought for their freedom and by their own undying commitment to their craft and each other.

This is art of the internet age, with layer upon layer of cultural exchange inflecting an idiom that is at once unmistakably authentic and entirely new. It both reflects the wreckage of the society around it and projects a defiant flyness in its face. Because even as Stiff Pap hold a mirror to a chaotic and bleak world, their art is unafraid to imagine a different future. In tough times, hope is a radical act.

July 4, 2021

KK and the USA

When Kenneth David Kaunda died in Lusaka, Zambia on June 17, 2021, it marked the passing of the last of the great African nationalists who led the fight against racism and colonialism. Kaunda, known by all as ���KK,��� first emerged on the international stage in the 1950s as an organizer for the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress (NRANC). He rode around the vast northern province on his bicycle with his guitar in tow, giving speeches and singing freedom songs in scores of villages and thereby inspiring the locals to found NRANC branches. After serving time in prison for his activism, he emerged to take charge of the splinter United National Independence Party (UNIP) in 1960. He was chosen as the first African prime minister of Northern Rhodesia in early 1964, and when Zambia became independent on October 24 that year, he took the reins as the first president. He held that post until 1991. This story is familiar to many students of African history, but less well-known is Kaunda���s central role in relations between his nation and the United States. Indeed, for over 40 years beginning in 1960, KK did more than anyone else to build bridges between Zambia and the US.

Kaunda���s connections with the US started in 1960 when he participated in Africa Freedom Day festivities in New York City and encountered civil rights leader, Martin Luther King. Kaunda visited several places across the US, including Atlanta, where he reunited with King for an event at the Ebenezer Baptist Church (where King served as pastor). Their friendship personified the global nature of the fight against racism and initiated an important long-term connection between black Americans and Zambians. In 1961 KK returned for Africa Freedom Day, and although he was only a nationalist in a British colony, was invited to the White House for a meeting with John F. Kennedy. Kaunda impressed Kennedy, and vice versa. In 1963 after receiving an honorary doctorate from Fordham University in the Bronx, New York, KK revisited the White House and this time met with attorney general Robert Kennedy, the president���s fiery younger brother. The Kennedy brothers made a real impression on KK, and he was deeply saddened by their assassinations.

In early December 1964, shortly after independence, Kaunda returned to the White House for talks with President Lyndon Johnson (LBJ). Johnson had done much to facilitate passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and while vice president had taken a trip to Senegal. Although LBJ���s resume seemed to suggest good things for Kaunda and Zambia, the presidential summit started out positively but quickly devolved into disagreement. Kaunda���s criticism of a recent US intervention in the Congo to rescue hostages angered Johnson and the session ended on a sour note. Seeing that LBJ was no Kennedy reinforced Kaunda���s inclination to pursue a non-aligned foreign policy, and in 1965 he began working to establish ties with the governments in China and the Soviet Union. His efforts bore fruit when China agreed to build a railroad connecting the Copperbelt to the port of Dar Es Salaam. The US worried about Zambian friendliness with the Communist bloc, and high-ranking diplomats such as Vice President Hubert Humphrey maintained close ties with Kaunda until the end of the Johnson years.

For the only time between the presidencies of John Kennedy and George H.W. Bush, there would be no White House visit by Kaunda during the Richard Nixon era. Following a Nixon directive to keep Africa at the bottom of the foreign affairs agenda, his staff refused to arrange a meeting of the presidents when KK journeyed to the USA to speak at the United Nations in 1970. Displeased at this show of disrespect, Kaunda accused Nixon of racism. During the rest of Nixon���s tenure, members of Congress and State Department officials repeatedly urged the scheduling of a meeting between the presidents, but it was not to be. Impressive diplomats such as Representative Charles Diggs, secretary of state William Rogers, and ambassador to the United Nations, George H.W. Bush, all travelled to Lusaka for talks with Kaunda during the Nixon years, so it was not quite a case of Kaunda being ignored completely by US officials.

Although stymied at the highest political level, Kaunda succeeded in building cultural connections between Zambians and black Americans in the early 1970s. Shortly after the snub by Nixon, KK hosted the legendary African American singer James Brown at the State House in Lusaka. Brown, known as the Godfather of Soul, thrilled Zambian audiences with lively performances on the Copperbelt and in Lusaka, and KK had attended the Lusaka show. During their dinner at State House, Kaunda and Brown spoke at length about their shared love of music. By embracing Brown and his funky music, KK improved his popularity among Zambians and strengthened bonds with blacks in the USA. Other similar landmark events during the mid-1970s in Lusaka included a concert by Duke Ellington and a visit by Coretta King to open the Martin Luther King library for Zambian students.

With the overthrow of the dictator Marcello Caetano in Portugal (which caused the independence of Mozambique and Angola) and the replacement of the disgraced Nixon with Gerald Ford as US president, the year 1974 marked a turning point for KK���s role in US relations with southern Africa. Good diplomacy by Jean Wilkowski, the US ambassador in Lusaka, and Vernon Mwaanga, the Zambian foreign minister, laid the groundwork for a Kaunda state visit to the White House in April 1975. Ford was a gracious host, even when KK lambasted the US for not having a very admirable policy toward his region since the days of Kennedy. Ford and his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, met at length with Kaunda and his team and were treated to KK���s detailed analysis of the challenging situation in his part of the world, particularly in Angola which was descending into civil war. For the next ten years Kaunda occupied center stage when it came to US relations with southern Africa.

In April 1976, Kissinger delivered one of the most significant speeches in the history of US foreign relations in Lusaka, and his pledge to fight colonialism and racism brought KK to tears. Kaunda and Kissinger met multiple times for long talks throughout 1976 in hopes of facilitating a settlement that would bring peace, majority rule, and independence to neighboring Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). There was no question that Kissinger considered KK���s advice and mediation crucial to the undertaking. Their attempt came up short but not for lack of effort by either Kaunda or Kissinger, who left office when his boss Ford lost to Jimmy Carter in November.

Carter kept the diplomatic spotlight on Rhodesia and worked more closely with KK than any other US president. The highlight was a three-day state visit to Washington by Kaunda in May 1978, when the two presidents spent many hours in conversation. During a black-tie dinner at the White House, KK strummed his guitar and sang his most famous freedom song, ���Tiyende Pamodzi��� (let us go forward together), in Bemba. The Carter years also featured continued cooperation between Kaunda and African Americans, most notably the US ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young. Young served as Carter���s point man on relations with southern Africa, and he met multiple times with KK and with other southern African leaders. Kaunda, ultimately, played a central role in influencing the decision by British prime minister Margaret Thatcher to organize a conference in late 1979 at Lancaster House which eventually brought peace, majority rule, and the independent nation of Zimbabwe. Both Young and Kaunda attended the April 1980 independence ceremony in Harare and gleefully listened to Bob Marley perform ���Zimbabwe.���

As the focus of regional diplomacy shifted first to Namibia and then South Africa, Kaunda maintained his place as Washington���s key contact in the region. Both Ronald Reagan and his successor Georg H.W. Bush hosted KK for White House visits, in 1983 and 1989, respectively. Kaunda���s commitment to fight racism and colonialism contributed to the end of apartheid in South Africa and independence for Namibia. Defeated in 1991 in Zambia���s first multiparty election since 1972, Kaunda soon shifted his energy to the fight against HIV/AIDS. During a year-long residency for retired African heads of state at Boston University in 2002-03, he addressed audiences around the US and emphasized this cause. When George W. Bush signed the historic legislation pledging $15 billion to the struggle against HIV/AIDS in 2003, he acknowledged the tireless work on the issue by KK, who was in attendance. For over 40 years, Kenneth Kaunda cooperated with a wide range of people from the US in the fights against racism, colonialism, and disease. No one has done nearly as much as KK to improve between Zambia and the USA, and surely no one ever will.

July 1, 2021

The EFF will not bring the change South Africans need

This is an edited version of an article first published in Amandla magazine in South Africa. It is republished here courtesy of a partnership between Africa Is a Country and Amandla.

Reading the Economic Freedom Fighters��� manifesto for South Africa���s last general election in 2019 and watching their online lecture series, one sees a party that offers Pan-African socialism. The thought of Frantz Fanon has converged with Marxist Leninism to supposedly deliver a revolution deferred 27 years ago.

But postapartheid politicians are infamous for talking left and walking in every other direction. Has the EFF���s professed commitment to socialism remained steadfast? Have their radical ideals been made tangible in the actions of the party throughout its brief history?

An overview of the EFF in the past and present reveals a party bloated by ideological ambiguity and contradiction. Lacking an ideological anchor, they often misdiagnose the source of the country���s major crisis, offering antiquated solutions while also undermining their ability to achieve their stated objectives.

So how is the party of Julius Malema to be understood?��

They can be classified as electoral populists, where populism is as a style of politics and set of strategies used to amass power. Because the party is entangled in ideological disorder, issues of race are dangerously misunderstood and exploited for electoral gains or trivial wars of identity. The project of kindling class consciousness and building working class power from the bottom up is cast aside. And once again, citizens are left yearning for radical change through a political party that cannot deliver it.

���In South Africa, we are still to deal with class divisions. At the core of our divisions is racism,��� Malema has stated.

Populists on both the right and left often portray the struggle for political power as one erupting between corrupt elites and oppressed masses. For the EFF, the great divide is between a wealthy white minority and the destitute black masses, whose oppression and exploitation both produces and sustains white economic domination.

Racial inequality is the central factor which fuels the EFF���s program. This presents a problem not only for the EFF but for anyone seeking to diagnose the source of our society���s major ills. No one awake to South Africa���s reality can reasonably deny the disastrous impacts of systemic racism. But as an explanation for all social and economic issues, racism only takes us so far when trying to understand the nature of oppression.

Racism is a fluent and visceral expression of class domination under capitalism. The mass poverty, unemployment, and exploitation long endured by black South Africans is a result of capitalism���s imperatives. These imperatives exclude most from accessing the means for producing wealth by exalting the use of private property for making and hoarding profits. Those locked out of such access become an underclass which must work in life-draining servitude for pitiful wages.

Race as we understand it today is a myth, refined over centuries to justify capitalism���s class divisions. Those branded as inferior or barely human can be treated as expendable tools to amass wealth for the comfort and domination of a ���superior��� minority. Colonial conquerors and the apartheid regime used the myth of racial identities to legitimize their conquest and accumulation. Because revolution was deferred in 1994, primarily due to the interests of global and local capital, the exploitative structure of apartheid���s economy largely persists into our present.

The EFF���s obsession with racial divisions is misleading. The reclaiming of white wealth will not lead to black liberation. Moreover, the rhetoric of anti-racism can be co-opted by black people hoping to change the racial composition of inequality but not inequality itself. And such ambitions are often expressed as a desire to rid our economy of white supremacy.

But if relations of class domination and exploitation persist, so will destitution for most black people. Remember that a small black elite has found success in the postapartheid era, but those black faces in high places have no interest in advancing liberation. Their class positions���as corporate managers, career politicians and successful tenderpreneurs���compel them to pursue self-enrichment. And, importantly, to keep intact an economic order which keeps the working class exactly where they are.

The EFF has offered stirring critiques of capitalism. But the future they offer is not socialist. It is not of an economy democratically run by workers or a society held together by communal ownership and collective decision-making, where all contribute and benefit in accordance with their needs and abilities. Rather, the party proposes an economy partly managed by the state ���on behalf��� of citizens, with some sectors still under the reins of private interests.

Can this top-down, state-led approach to transforming the economy be trusted? In other words, is the party of Julius Malema truly fighting for the working class?

A concerning and constant criticism of the EFF is the absence of a democratic culture within the party. Old and current members have revealed how the organization shuts down criticism or constructive dissent, preferring loyalty to the thinking of the executive leadership. One also can���t overlook the intense adoration for commander-in-chief Julius Malema within the party. This adoration can be fierce���to the point that members defend some of Malema���s disturbing remarks or harass those (particularly journalists) who criticize their leader.

This lack of a democratic culture is another reason for the EFF���s ideological confusion. Stifling criticism and centering a party around its top brass of leadership limits the capacity for new ideas or new strategies for advancing its objectives. This erases the possibility of moving beyond its contradictions. It may also produce a leadership that evades accountability while treating its members as instruments for their political ambitions.

It���s hard to imagine that a party so presently hostile to a democratic culture could suddenly embrace it once in executive power, or that it could be democratic in its management of the state and national resources.

It is the working class which actually produces society���s wealth. If it becomes aware of its status and is mobilized, it can threaten the power of capital using its immense leverage. Historically, this has made it a pivotal force for radical change. Although the EFF is not totally distanced from the working class (many of its members are poor and working class), its relationship is not one of steadfast solidarity. The party���s engagement with this grouping is largely opportunistic, sporadic, and guided by authoritarian impulses. Therefore, the party is unlikely to pose a significant threat to capital���s political power or economic might.

Grassroots movements across the country, such as the Amadiba Crisis Committee and Abahlali baseMjondolo, have courageously fought and won valuable victories over mass evictions, labor disputes, municipal corruption, xenophobia, and food security. But the EFF���s interaction with these progressive agents has been lackluster at best. It has often been absent in the struggles of rural women against mining industries or in the fights of the poor against violent evictions. Some grassroots movements have even condemned the EFF as opportunists, rejecting the party with fierce contempt.

Additionally, no close ties or tangible solidarity exist between the EFF and the country���s various unions. The Workers and Socialist Party has previously criticized the red berets for their previous attempts to take over the union, as well as for attempts by the EFF to silence and dismiss criticism during internal leadership meetings.

If the EFF were seriously pursuing socialism, they would understand that it cannot be won through the ballot box alone. Outside government, there exist zones of power���within the media, the state, the education system, and of course the private sector���that function to maintain the supremacy of capital alongside the political order which sustains it. To combat these concentrations of power, a working class movement is needed to consistently exert pressure for radical change, challenge dominant ideologies, and combat the inevitable state violence that will result from such mass mobilization.

Without such a sustained movement, any radical party will not be able to defend itself against an onslaught of opposition from those eager to preserve the status quo. Almost a decade since its creation, the EFF is not firmly rooted in the working class, therefore undermining its own proclaimed goals.

The EFF is neither fascist nor legitimately leftist. Devoid of ideological clarity, mostly disengaged from the working class and reluctant to embrace democracy from within the party, they are bound to a populism that can invite great attention and perhaps gain them some electoral advances. But ultimately, they will not be an avenue for radical change.

Breaking the shackles

Photo by Etornam Ahiator on Unsplash

Photo by Etornam Ahiator on Unsplash This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

In February 2020, the British newspaper The Guardian published an article entitled ���The scandal of Ghana���s shackled sick.��� The article portrayed a grim picture of Ghana as a ���mental health void.��� There were, according to the journalist, only a ���handful��� of community mental health nurses in the country and medical facilities were ���empty of psychiatric understanding.��� The journalist met one of these nurses, Stephen Asante, who had set up an NGO, visiting families and healers, and working to free people with mental illness from their chains. However, there were problems with the supply of pharmaceuticals. ���Since we ran out of medication, the only thing on offer is the chain,��� he was quoted as saying.

The journalist and photographer were accompanying Human Rights Watch on a research trip to Ghana, the results of which were included in a report ���Living in Chains,��� which documents the shackling of people with mental health conditions in homes, healing centres, and hospitals, predominantly in Africa and Asia. Such reports on human rights and mental health in Ghana have become ubiquitous over the years. A 2012 report by Human Rights Watch depicting chaining and other human rights abuses in prayer camps, shrines, and hospitals cast Ghana in the spotlight of global mental health and was widely used to support calls for investment and research.

The Guardian article was accompanied by a series of carefully composed portraits depicting people chained to trees or locked behind iron grills, often alone. The overwhelming impression is of stasis, emptiness, and lack. These are familiar tropes of Africa: the place without history or innovation, where nothing changes; of starving bodies, deprivation and backwardness, awaiting rescue from outside of course. The images of chained Black bodies recall those deployed to argue for the abolition of the slave trade, the Black African on his knees, raising his shackled wrists in supplication������Am I not a man and a brother?��� In Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, the American writer and academic, Saidiya Hartman argues that these images reinforce the dynamics of the master slave relationship���the African must beg for his freedom, which rests in the hands of a powerful White saviour to bestow. The resonance with slavery is obvious but unmentioned (or unmentionable)���the chains and shackles that bind people with mental illness today are almost exact replicas of those used to forcibly capture and kidnap millions of Africans.