Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 120

August 3, 2021

Sound Sultan’s political music

#EndSars protesters (Photo by Ayanfe Olarinde on Unsplash).

#EndSars protesters (Photo by Ayanfe Olarinde on Unsplash). ��� Dele GiwaNigeria is on fire and the citizens are amused.

��� Odia OfeimunAnd I must tell my story

to nudge and awaken them

that sleep

among my people.

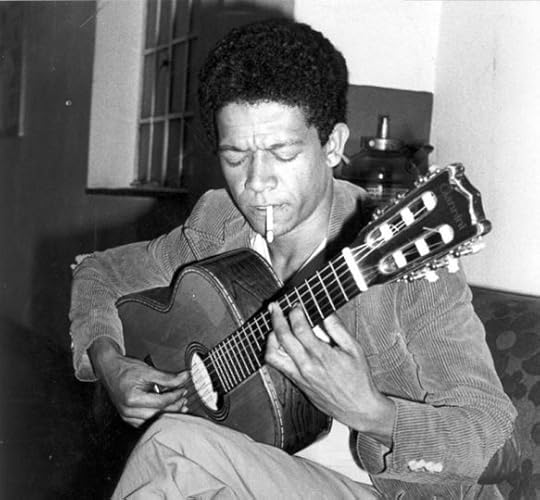

Sound Sultan���the stage name for the legendary Olanrewaju Abdul-Ganiu Fasasi of Naija Ninja (how his brand and label was known)���has saturated social media since July 11th when he succumbed to death at the age of 44. Sultan was born in Jos, Plateau State, the fourth born in a family of five. He was vastly talented and his passion for arts encompassed other mediums such as acting, comedy, songwriting and playing guitar, among others. He had performed widely and won awards for his songs that enriched people���s minds and created a space for them to ponder critically on societal happenings and events, especially in Nigeria.

In Sound Sultan���s songs, the theme of political consciousness is cardinal. Spanning years of intimidating musical successes, his songs capture, beautifully, the plight of the masses and their quotidian frustration and grievances at the Nigerian government and their multiple ways of cheating the people. Also, Sultan���s insights permeate through the choice of the themes he engaged with, and his use of language (the blend of Yoruba and English) he deployed to present these songs. For example, released in 2020, ���Faya Faya,��� which featured Duktor Sett, is a sublime piece of a musical work that depicts the unsettling condition of the country and the longing for hope by the masses. The image of fire portends wanton destruction and unrest happening in the country. Deftly rendered with a voice that carries despair and weariness, ���Faya Faya” enables us to grieve our collective yearnings; our dying dreams and aspirations. The use of refrain in some of Sultan���s politically inclined musical offerings stresses the extremity of the problems bedeviling the citizenry. The repetition of “pana pana” lends credence to the futile years of waiting for leaders to douse the fire of postcolonial problems that include corruption, political instability, needless killings, unemployment, etc. In the song, Sultan sings:

While we are waiting for a miracle

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

For we are waiting oracle

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

We dey pray make fire cool

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

Panapana o panapana o panapana o.

Here, the image of chaos is portrayed through these incisive lines. Years after electing new leaders, their promises of change become mirages. This monumental failure appears disturbing, as the masses become thirsty for the phantom promises of the elected. In recent times, Nigeria has become a craggy hill for activists and people who crave the desired changes from the government. In October 2020, the Lekki Tollgate Shooting (as part of the #EndSars protests) sparked critical reactions in the country. The tragic event triggered a global realization of the recklessness displayed by our security forces to combat the perpetual killings of the citizens by SARS (a police unit notorious for its abuse). Apart from this, the ravaging effects of attacks masterminded by Fulani herdsmen across the country has raised serious concern about the safety of the citizens. In furtherance, the song highlights the weapons of tribalism and religious polarization used in dividing and creating discordant tunes among the masses.

In another song titled ���Ole (Bushmeat),��� released in 2011, Sultan berates the thieving leaders and their gimmicks in milking the country dry. His angst is more pronounced, as he lashes with lines that describe aptly the looters and their insatiable quest for our collective resources. Describing the retrogressive state of the country and the evils perpetrated by its elected leaders, Sultan offers us a memorable song that bears the weight of our collective grief. Revolutionary in style, the song evokes years of looting and the mismanagement of public funds that plague the country. The image of the bushmeat and the hunter represent the citizens and the leaders. The hunters (the leaders) prey on the masses (the bushmeat). Again, the refrain������Ole������threads the song. This portrays Sultan���s creative ingenuity and prowess in capturing the terrible happenings in the society without forgoing the poetic flavor that embellishes his work. In ���Ole,��� he sings:

See them fly for the aeroplane

remember all the pains my people dey maintain

I don tire to dey explain

pikin wey never chop dey complain

water light na yawa

everywhere just light no power

only power na the one wey dem

dey use oppress us.

These lines reinforce the oppressive system engineered by the leaders in Sultan’s homeland. Through this song, we become attuned to the sufferings of the people and the privileges enjoyed by the leaders. The gap between the poor and the rich becomes more visible. For example, typical of our leaders��� ritual is flying abroad for medical intervention, while the masses patronize ill-equipped hospitals that double as a slaughterhouse for those who dread the possible deaths of patients in these hospitals. Worthy of mention are the potholes that garnish our roads, while the leaders travel through air to other countries.

Sultan���s musical trajectory continues to guide us through his penchant for the unflagging engagement of societal decadence and rot that inhabit his homeland. In ���2010 (Light Up),��� featuring M.I. Abaga, his overwhelming anger at the Nigerian leaders prevails. ���2010 (Light Up)��� confronts the leaders with their failure to provide a stable electricity power supply for the masses. Through this song, Sultan revisits the promises made by Nigerian leaders and how the drought of political accountability ravages the country. He sings:

When we ask our government

when dem go give us light o

Dem say na 2010

We don dey wait 2010 since then

But now the waiting must end

Coz 2010 don show oh oh oh.

It is noteworthy to state that ���2010 (Light Up)��� remains one of the most politically reverberating songs in the country. Sultan’s attempt at deracinating the Nigerian populace from the locusts devouring their minds is commendable. The metaphor of Moses leading his people to the promised land deployed by Sultan is befitting. Sadly, his homeland murders those who rise against the tide of revolution. The Moses is hung at the gallows or buried somewhere unknown, while the systemic annihilation of messiahs never ceases. Evaluating the political history of Nigeria, the emergence of the anguish of dashed hope becomes an inevitable reality. One comes face-to-face with the sad stories of the likes of MKO Abiola and the annulled election of June 12, 1993; Ken Saro Wiwa and his fight against oil spillage in Ogoni land, and Dele Giwa and his assassination by unknown killers via a bomb parcel. The deaths of these people accentuate the tragic end of every Moses rising to change the mind-wrenching narratives of postcolonial trauma in Nigeria. Sultan sings:

I want to be like Moses.

Show my people dem

to the promised land

But then I noticed something o

People wey try am don dey underground

I see dem I ja.

Furthering in his indefatigable quest for a utopian homeland, Sultan laments about the ineptitude of the Nigerian leaders and their colossal failures in other verses in this song. Voyaging through the other mind-stirring verses in this song, the revolutionary tropes that render the song a masterful work become more visible. Sultan sings:

Rise up Naija

Raise your apa

Tell them you are tired of the evil

E don tey wen fela don go o

E don tey wen fela don go o

So the leaders are after the dough.

The mention of Fela Kuti is symbolic and timely in this song. Opening the untreated wound of socio-political problems in Nigeria, Fela’s politically poignant songs come to mind. Like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X���s speeches that capture the struggle for black freedom in the United States and on the African continent, Fela’s songs were and still instrumental to instigating the masses against the political weevils burrowing their petals of dreams. He battled with the cankerworm of bad leadership and outright violations of rules of law in his homeland through his songs. He dissected national issues and portrayed through his songs the enormous turbulence created by military leaders and their immense suppression of human rights. He called for the liberation of Nigerians���the common men, the market women, the dying children, the bedridden retired people, the forlorn ones whose means of survival are deprived.

Fela died in 1997, but the Nigerians��� problems remain unsolved. Sultan’s revolutionary voice echoes through the song as he says ���Rise up, Naija/Raise your apa.��� Sultan’s disdain for tyranny and oppression reflects in this song. His scathing criticism of the leaders��� toxic use of power enhances our understanding of how corrupt and ineffective the system is under the government. In ���Naija Jungle,��� released in 2018, Sound Sultan still delves into his usual description of the problems affecting the country, and how the bourgeoisie persist in their familiar way of oppressing the proletariats. The uneven distribution of wealth reflects in the verses of the song too. In addition, the song reminds us of George Orwell���s seminal book titled ���Animal Farm��� and Beautiful Nubia���s ���The Small People���s Anthem.��� In both aforementioned references, the masses suffer greatly, while the leaders amass wealth at the expense of depriving the masses the basic amenities that will help them survive. Instead of contributing immensely to the progress of the society and the people, the leaders watch the people wallow in abject poverty. Sound Sultan sings:

Some dey look, some dey work

Some dey talk, some dey chop

Some dey live on the roof

While some sleep on the ground

Some dey work all the work, while some chop

Till belle full for ground

Chorus:

Monkey dey work, baboon dey chop

Plenty dey happen for jungle

When lion dey talk, tortoise shut up

Plenty levels for jungle.

In other verses in the song, there is the portrayal of the jungle Sultan attempts to explore. This kind of jungle is characterized by injustice and punishment melted on the masses. It is a jungle that offers no respite, and the lives of its inhabitants are vulnerable to untimely death. In this jungle, people die because they are weary of waking up to the ache of lamenting about the worrisome state of everything. This kind of jungle is sinister, and only those who can endure the aches will survive. It is a jungle named Nigeria, and the people there are dying.

Sound Sultan’s Music Politics

#EndSars protesters (Photo by Ayanfe Olarinde on Unsplash).

#EndSars protesters (Photo by Ayanfe Olarinde on Unsplash). ��� Dele GiwaNigeria is on fire and the citizens are amused.

��� Odia OfeimunAnd I must tell my story

to nudge and awaken them

that sleep

among my people.

Sound Sultan���the stage name for the legendary Olanrewaju Abdul-Ganiu Fasasi of Naija Ninja (how his brand and label was known)���has saturated social media since July 11th when he succumbed to death at the age of 44. Sultan was born in Jos, Plateau State, the fourth born in a family of five. He was vastly talented and his passion for arts encompassed other mediums such as acting, comedy, songwriting and playing guitar, among others. He had performed widely and won awards for his songs that enriched people���s minds and created a space for them to ponder critically on societal happenings and events, especially in Nigeria.

In Sound Sultan���s songs, the theme of political consciousness is cardinal. Spanning years of intimidating musical successes, his songs capture, beautifully, the plight of the masses and their quotidian frustration and grievances at the Nigerian government and their multiple ways of cheating the people. Also, Sultan���s insights permeate through the choice of the themes he engaged with, and his use of language (the blend of Yoruba and English) he deployed to present these songs. For example, released in 2020, ���Faya Faya,��� which featured Duktor Sett, is a sublime piece of a musical work that depicts the unsettling condition of the country and the longing for hope by the masses. The image of fire portends wanton destruction and unrest happening in the country. Deftly rendered with a voice that carries despair and weariness, ���Faya Faya” enables us to grieve our collective yearnings; our dying dreams and aspirations. The use of refrain in some of Sultan���s politically inclined musical offerings stresses the extremity of the problems bedeviling the citizenry. The repetition of ���pana pana��� lends credence to the futile years of waiting for leaders to douse the fire of postcolonial problems that include corruption, political instability, needless killings, unemployment, etc. In the song, Sultan sings:

While we are waiting for a miracle

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

For we are waiting oracle

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

We dey pray make fire cool

Fire dey burn dey burn dey burn

Panapana o panapana o panapana o.

Here, the image of chaos is portrayed through these incisive lines. Years after electing new leaders, their promises of change become mirages. This monumental failure appears disturbing, as the masses become thirsty for the phantom promises of the elected. In recent times, Nigeria has become a craggy hill for activists and people who crave the desired changes from the government. In October 2020, the Lekki Tollgate Shooting (as part of the #EndSars protests) sparked critical reactions in the country. The tragic event triggered a global realization of the recklessness displayed by our security forces to combat the perpetual killings of the citizens by SARS (a police unit notorious for its abuse). Apart from this, the ravaging effects of attacks masterminded by Fulani herdsmen across the country has raised serious concern about the safety of the citizens. In furtherance, the song highlights the weapons of tribalism and religious polarization used in dividing and creating discordant tunes among the masses.

In another song titled ���Ole (Bushmeat),��� released in 2011, Sultan berates the thieving leaders and their gimmicks in milking the country dry. His angst is more pronounced, as he lashes with lines that describe aptly the looters and their insatiable quest for our collective resources. Describing the retrogressive state of the country and the evils perpetrated by its elected leaders, Sultan offers us a memorable song that bears the weight of our collective grief. Revolutionary in style, the song evokes years of looting and the mismanagement of public funds that plague the country. The image of the bushmeat and the hunter represent the citizens and the leaders. The hunters (the leaders) prey on the masses (the bushmeat). Again, the refrain������Ole������threads the song. This portrays Sultan���s creative ingenuity and prowess in capturing the terrible happenings in the society without forgoing the poetic flavour that embellishes his work. In ���Ole,��� he sings:

See them fly for the aeroplane

remember all the pains my people dey maintain

I don tire to dey explain

pikin wey never chop dey complain

water light na yawa

everywhere just light no power

only power na the one wey dem

dey use oppress us.

These lines reinforce the oppressive system engineered by the leaders in Sultan’s homeland. Through this song, we become attuned to the sufferings of the people and the privileges enjoyed by the leaders. The gap between the poor and the rich becomes more visible. For example, typical of our leaders��� ritual is flying abroad for medical intervention, while the masses patronize ill-equipped hospitals that double as a slaughterhouse for those who dread the possible deaths of patients in these hospitals. Worthy of mention are the potholes that garnish our roads, while the leaders travel through air to other countries.

Sultan���s musical trajectory continues to guide us through his penchant for the unflagging engagement of societal decadence and rot that inhabit his homeland. In ���2010 (Light Up),��� featuring M.I. Abaga, his overwhelming anger at the Nigerian leaders prevails. ���2010 (Light Up)��� confronts the leaders with their failure to provide a stable electricity power supply for the masses. Through this song, Sultan revisits the promises made by Nigerian leaders and how the drought of political accountability ravages the country. He sings:

When we ask our government

when dem go give us light o

Dem say na 2010

We don dey wait 2010 since then

But now the waiting must end

Coz 2010 don show oh oh oh.

It is noteworthy to state that ���2010 (Light Up)��� remains one of the most politically reverberating songs in the country. Sultan’s attempt at deracinating the Nigerian populace from the locusts devouring their minds is commendable. The metaphor of Moses leading his people to the promised land deployed by Sultan is befitting. Sadly, his homeland murders those who rise against the tide of revolution. The Moses is hung at the gallows or buried somewhere unknown, while the systemic annihilation of messiahs never ceases. Evaluating the political history of Nigeria, the emergence of the anguish of dashed hope becomes an inevitable reality. One comes face-to-face with the sad stories of the likes of MKO Abiola and the annulled election of June 12, 1993; Ken Saro Wiwa and his fight against oil spillage in Ogoni land, and Dele Giwa and his assassination by unknown killers via a bomb parcel. The deaths of these people accentuate the tragic end of every Moses rising to change the mind-wrenching narratives of postcolonial trauma in Nigeria. Sultan sings:

I want to be like Moses.

Show my people dem

to the promised land

But then I noticed something o

People wey try am don dey underground

I see dem I ja.

Furthering in his indefatigable quest for a utopian homeland, Sultan laments about the ineptitude of the Nigerian leaders and their colossal failures in other verses in this song. Voyaging through the other mind-stirring verses in this song, the revolutionary tropes that render the song a masterful work become more visible. Sultan sings:

Rise up Naija

Raise your apa

Tell them you are tired of the evil

E don tey wen fela don go o

E don tey wen fela don go o

So the leaders are after the dough.

The mention of Fela Kuti is symbolic and timely in this song. Opening the untreated wound of socio-political problems in Nigeria, Fela’s politically poignant songs come to mind. Like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X���s speeches that capture the struggle for black freedom in the United States and on the African continent, Fela’s songs were and still instrumental to instigating the masses against the political weevils burrowing their petals of dreams. He battled with the cankerworm of bad leadership and outright violations of rules of law in his homeland through his songs. He dissected national issues and portrayed through his songs the enormous turbulence created by military leaders and their immense suppression of human rights. He called for the liberation of Nigerians���the common men, the market women, the dying children, the bedridden retired people, the forlorn ones whose means of survival are deprived.

Fela died in 1997, but the Nigerians��� problems remain unsolved. Sultan’s revolutionary voice echoes through the song as he says ���Rise up, Naija/Raise your apa.��� Sultan’s disdain for tyranny and oppression reflects in this song. His scathing criticism of the leaders��� toxic use of power enhances our understanding of how corrupt and ineffective the system is under the government. In ���Naija Jungle,��� released in 2018, Sound Sultan still delves into his usual description of the problems affecting the country, and how the bourgeoisie persist in their familiar way of oppressing the proletariats. The uneven distribution of wealth reflects in the verses of the song too. In addition, the song reminds us of George Orwell���s seminal book titled ���Animal Farm��� and Beautiful Nubia���s ���The Small People���s Anthem���.�� In both aforementioned references, the masses suffer greatly, while the leaders amass wealth at the expense of depriving the masses the basic amenities that will help them survive. Instead of contributing immensely to the progress of the society and the people, the leaders watch the people wallow in abject poverty. Sound Sultan sings:

Some dey look, some dey work

Some dey talk, some dey chop

Some dey live on the roof

While some sleep on the ground

Some dey work all the work, while some chop

Till belle full for ground

Chorus:

Monkey dey work, baboon dey chop

Plenty dey happen for jungle

When lion dey talk, tortoise shut up

Plenty levels for jungle.

In other verses in the song, there is the portrayal of the jungle Sultan attempts to explore. This kind of jungle is characterized by injustice and punishment melted on the masses. It is a jungle that offers no respite, and the lives of its inhabitants are vulnerable to untimely death. In this jungle, people die because they are weary of waking up to the ache of lamenting about the worrisome state of everything. This kind of jungle is sinister, and only those who can endure the aches will survive. It is a jungle named Nigeria, and the people there are dying.

August 2, 2021

It���s never just about the music

Spirits Rejoice 1976. Image credit Tony Campbell via Matsuli Music.

Spirits Rejoice 1976. Image credit Tony Campbell via Matsuli Music. In South Africa, it���s never just about the music. And doubly so where South African jazz is concerned. There is also meaning, context, history, and politics to contend with, and here South Africa���s jazz is a synecdoche, out of which tumbles the broad swathe of a history of turbulence, trouble, defiance, and hope. And so it is with two upcoming vinyl reissues from Matsuli Music, a record label specializing in South African rarities and jazz classics: The 1977 jazz fusion breakthrough African Spaces from Spirits Rejoice and the long lost 1968 recording Gideon Plays by the visionary jazz composer Gideon Nxumalo.

They are wildly different albums, but in the manner of siblings: they stretch into their own corners, speak their own dialects, yet they are of a bloodline and undeniably fraternal, successive signposts on a South African jazz cartography that is no narrow thing.

Russel Herman. Image via Matsuli Music.

Russel Herman. Image via Matsuli Music.No matter which way you cut it, Nxumalo is a central figure in the genre. A university-educated composer, he was the first South African jazz artist to incorporate traditional musical sources and instruments. It���s been said that Nxumalo could transition easily from Mozart to Marabi and back again in the course of one eclectic and erudite sitting. He wrote multiple music scores, including that for ���Sponono,��� the first South African production on Broadway, taught music, and mentored multiple budding artists.

Even on a first listening of Gideon Plays, his singular talent as a composer and pianist is unmistakable. This is urbane bop with a distinctive African edge. Like many things that are beautiful and true, there is a plurality to the compositions, but as presented here, these manifold strands become one. This is music that demands that you stop and listen. It is music as an act of healing.

Because with Nxumalo, of course, it���s not just about the music. He was also one of South Africa���s most significant radio presenters and jazz tastemakers. Fom 1954 onwards, nicknamed ���uMgibe,��� he hosted ���This Is Bantu Jazz,��� South African radio���s premier jazz show, and helped popularize the term Mbaqanga (meaning, literally, traditional steamed maize bread, but figuratively, the popular working-class ���daily bread��� of musicians) for the music of the era.

Then, in March 1960, came Sharpeville, when 69 people were gunned down and more than 180 wounded after police opened fire on a crowd protesting against discriminatory pass laws. The massacre marked the beginning of an era of repression of African culture as the government imposed a state of emergency and put activists who challenged apartheid laws on trial. Nxumalo was not politically naive, nor unaware. In the aftermath of Sharpeville, he knew which way the compass pointed. Defiantly, he played records with political connotations on the radio, and it cost him his job.

Undeterred, he continued to find ways to rebel. On his 1962 album Jazz Fantasia, he disguised a quotation from Nkosi Sikelel��� iAfrika in one of his songs. That same year, he played a role in the movie Dilemma, which was based upon the banned Nadine Gordimer novel A World of Strangers, and filmed in secret in Johannesburg.

By an Act of Parliament in 1962, the apartheid regime legalized imprisonment without trial. Many South African artists went into exile, and would continue to do so for almost three decades. Nxumalo could not have left even if he had wanted to: he was refused a passport.

By 1968, he had not been heard on record or radio for years. Gideon Plays thus marked an overdue return to the studio for one of South Africa���s most brilliant and pioneering jazz artists. But after a limited pressing, it was seemingly lost to history.

Gilbert Matthews. Image via Matsuli Music.

Gilbert Matthews. Image via Matsuli Music.Mythologized and sought-after, Gideon Plays painted, in bold strokes, South Africa���s jazz logos. Ten years later, African Spaces recalibrated and refracted the jazz genre, fusing, electrifying, finding new shapes and shades. African Spaces lays the funk on treacle-thick, but there are notable gestures towards soul, disco and pop. The rhythm section keeps things urgent, while the horns fly insistently free. The whole thing is resolutely forward thinking.

Spirits Rejoice (named in honor of Albert Ayler���s 1965 live album) is a band of truly formidable jazz and fusion pedigree. Drummer Gilbert Matthews, who passed away in 2020 was foundational in the group���s inception, and Spirits Rejoice also included iconic bassist Sipho Gumede, Russell Herman and Enoch Mthalane on guitar, reedmen Duku Makasi and Robbie Jansen, George Tyefumani and Themba Mehlomakhulu in the brass section and, in different iterations, Bheki Mseleku and Mervyn Afrika on keyboards. In other words, a supergroup. Together, they created the South African response to the international call of modern jazz, and African Spaces is their debut recording.

A couple of the songs lean towards pop and accessibility, even as the complexity of the underlying musicality subverts any expectation that pop ought to equal simple. But it���s on the more angular, serrated, and boldly neoteric tracks such as ���Mulberry Funk��� and ���Savage Dance,��� and ���African Spaces��� that things really get interesting. They are ambitious and radically progressive. There is a sense of fun in the experimentation, as well as a couple of bass licks so dirty, they���d make George Clinton blush.

This is not music without a message,�� implicit or otherwise, and politically-charged lyrics lacquer over a deceptively simple hook on ���Makes Me Wonder Why.��� How could it be otherwise? This album was recorded mere months after the 1976 Soweto uprising, when protests sparked by the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in South African schools were met with murderous police brutality and hundreds were killed.

As is detailed in Francis Gooding���s liner notes, language, race, and politics also had a bearing behind the scenes within the band as Mthalane fell out with the band���s white management and was fired, a situation ���caused in part by Mthalane���s principled refusal to speak English over isiZulu.”

If Spirits Rejoice were very much a band of their time, they were also in some ways too far ahead of their time, so much so that they struggled to find a South African label brave and progressive enough to release such groundbreaking and radical jazz, and this album was only ultimately released in 1977.

It is in the act of remembrance and re-evaluation of such music that a fuller appreciation of the hidden spaces in this country���s struggle heritage come to light. There is deep history to be excavated. Each in their own way, these albums are psalm songs of the South African jazz holy grail. Within their blending and improvization (which is, after all, an insistence, at the heart of all jazz, on the right to be free) they contain an implicit condemnation of the cultural and creative repressions of apartheid. They weave a curious musomancy into something that is both grounded in material reality and unmistakably South African in idiom, and yet simultaneously beyond memory, beyond history, universal. This is music that is not just heard. It is felt.

Sipho Gumede. Image via Matsuli Music.

Sipho Gumede. Image via Matsuli Music.They are also capsules of a time and a place. Indeed, place provides a fascinating throughline between the two albums. Dorkay House, on Eloff Street in Johannesburg, was a cooperative rehearsal complex and music school. Even after the Group Areas Act and the razing of Sophiatown in the 1950s, it was also an integrated and extraordinary meeting place for all sorts of artists, home to a wild cross-pollination of creative and musical impulses, even as the regime sweated to keep people apart. Dorkay House���s alma mater could fill a South African jazz hall of fame: Miriam Makeba, Abdullah Ibrahim, Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, Kippie Moeketsi, Pat Matshikiza, Ntemi Piliso, John Kani and many more. Dorkay House was also home to the African Music & Drama Association, where Nxumalo taught piano and theory.

In 1974, it was at Dorkay House that members of Spirits Rejoice, who were originally from Cape Town, Johannesburg, Gqeberha (then Port Elizabeth) and Durban, came together and emerged organically from the complex matrix of mid-70s South African jazz to distill their own particular flavor of the zeitgeist.

There is a tinge of melancholy in re-treading this story in the here and now. Something elegiac in these recordings, these rememberings. An online search for Dorkay House elicits a roll call of obituaries. The old venue itself is in dire need of restoration, fading particularly quickly after the death in 2018 of Queeneth Ndaba, matriarch of Dorkay House and one of its keenest proprietors and defenders.

Dorkay House was so much more than four walls. It was a space transformed by those who inhabited it, and imbued it with humanity, fragrance, sound. It was colonized space reclaimed. It was also, importantly, a space where artists organized, doubling as the base of the Union of South African Artists, under which an enormous number of people trained and worked.

Gone is Dorkay, and gone any semblance of a broad musicians movement. These things need to be remembered, now more than ever. In the midst of a pandemic that has devastated the arts industry in South Africa, millions of rands meant for the relief of musicians and artists has been mismanaged. In March, a group of artists staged a month-long sit-in at the National Arts Council���s offices, demanding answers. Meanwhile, the SABC is dragging its feet on the more than R250 million it owes artists in royalties, despite a multi-billion rand bailout.

The hue might have changed, but the struggle continues. Today, South African musicians are beholden to predatory capital, the hidden exploitation of streaming platforms, and a seemingly indifferent government.

And so, as we engage with vinyl reissues such as these, we are also engaging in a fight against forgetting much more than just music. These are valuable artifacts of South Africa���s musical history that were transcendent of repressive daily conditions. Challenges remain in the here and now. The vibrant, radical artists of today���s South African jazz are the descendants of such soothsayers of the non-verbal, speaking truth to that which cannot be silenced. They are still learning to look at themselves differently, still redreaming the world, hidden gods speaking from within them a new language we will all need to learn in order to talk to each other. It���s about much more than just music.

The exilic geographies of the South

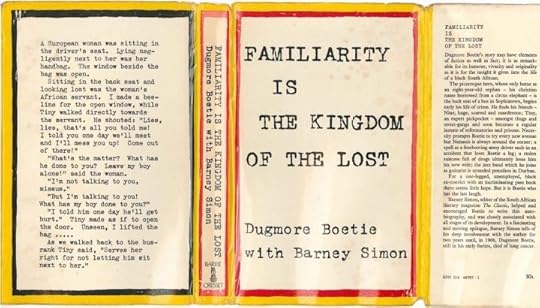

Dugmore Boetie book cover.

Dugmore Boetie book cover. In August 1960, Dugmore Boetie fled South Africa and entered Bechuanaland (present day Botswana) on foot. He was part of a flow of ���discontented young men��� that included the otherwise unfamiliar Johannes Moeng, Jacob Lesabeer, Spencer Tlhole, and Victor Vuysine Vinjike, observed by colonial intelligence agents. Security reports at the time portrayed them as mostly ���obscure��� and rather ���bewildered.��� British colonial security agents routinely monitored the thousands of men and women who entered the High Commission Territory because of the risk of reprisals and retaliatory actions by South Africa���s Special Branch police. South African Special Branch spies and agents were known to mix with refugees, making it ���extremely difficult��� to tell one from the other.

The relatively unknown Boetie was part of a wave of refugees moving north in late 1960, the peak period of an exilic migration that began immediately after the Sharpeville Massacre. It was a wave that swept beyond South Africa���s borders some of its greatest literary talents, many of whom were never to return. To be sure, the massacre was but the accelerator of an exilic movement that had begun in earnest in the mid 1950s. The future Nobel laureate, Nadine Gordimer, interviewed in the early 1980s, explained that persecution ���all began, really with the [1952] Defiance Campaign. People were arrested and the whole political scene got tougher . . . [but] people left South Africa out of intense frustration rather than danger.���

Many celebrated and lesser-known artists, writers, and musicians fled so-called ���banning orders,��� whereby they were completely prohibited from writing and stripped of primary income. Banned from teaching, Es���kia Mphahlele went into exile and published Down Second Avenue in London 1959. The formidable list of censorship provisions on the ���creative black writer��� were only some of the many impediments on expression, according to Zimbabwean poet Toby Tafirenyika Moyana: ���all repressive legislation��� impeded artistic work. Others fled because they were targeted by non-state agents, likely acting as proxies. Arthur Maimane detailed his flight to Ghana in 1958 after publishing a series of gripping gang-life stories in Drum magazine that resulted in him garnering a ���contract.��� He published the controversial Victims in London in 1976. According to the British editor of Drum, Antony Sampson, William ���Bloke��� Modisane left his beloved Sophiatown backyard for the UK in 1959 after constant harassment and threats. He published his powerful autobiography, Blame Me on History in London in 1963.

Born in a country that was politically and economically subjugated by European imperialism and apartheid, Douglas Buti, the author of Familiarity Is the Kingdom of the Lost���published posthumously under the nom de plume Dugmore Boetie���was part of a wave of South African writers who fled apartheid in the 1960s. Like his contemporaries, largely the Drum generation, Boetie���s flee emanated from the rich tradition of protest writing that helped international audiences to understand the brutality of apartheid in the 1950s onwards. These authors were black urbanites; they shared common experiences of racial oppression.

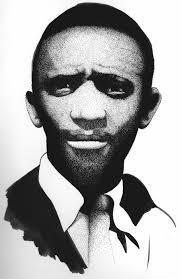

Dugmore Boetie.

Dugmore Boetie.More than telling a story, however, these writers were concerned with what was happening in their communities. They represented black voices through poems, short stories, plays, and novels. Their work was thus a part of the anti-apartheid struggle. With the intensification of the apartheid government repression after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. Censorship became the factor by which government intruded directly into literature. As a means of control censorship was applied more thoroughly and resolutely than before. Eventually, black and white creative writers were forced to submit their works to foreign publishers in Britain and the US. As a result, not a single book of creative literature written in English by a black author was published by a local South African publishing house during the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover, many publications and music were banned and silenced by government decree.

The richness of black literature captivated white liberal interest in the 1950s and the 1960s. Exposure to misery and suffering of black authors, their talent, and their creative work led many white liberals to be compassionate. They facilitated publication while promoting black writers. This was evident in the development of Boetie���s profile, who was supported financially by a writer, theater director, and a co-creator, Barney Simon leading to the publication of the Familiarity.

Boetie romanticizes delinquency and the hardships of urban street life by depicting apartheid���s socioeconomic pressures as factors that pushed him (as an eponymous fictionalized character Duggie) and other characters in his book toward crime. This notion was echoed by Father Trevor Huddleston who wrote:

tsotsi [criminal] is symbolic of something other than a simple social evil common to all countries���Like then he is aggressively anti-social; but unlike them he has a profound reason, as a rule for being so. He is a symbol of the society which does not care.

This normative conceptualization is characteristic of the writings of the Drum protest movement stalwarts, among them Can Themba and Casey Motsisi, who glamorized the tsotsi as the superior villain. As a naturally gifted writer, Boetie expressed what Lewis Nkosi called ���an extreme cultural ���underworldism��� of the African township.��� Nkosi���s assertion was gleaned from his own reality. In the ghetto-like slum at the center of Johannesburg, Sophiatown���s writers reflected on black marginalization and socioeconomic inequality. It was a space with a vibrant street life, where the spirit of the community revealed itself through, music, dance, overpopulation, crime, gangsters, gambling, informal trade, shebeens, brothels, children playing in the streets, and of course, stabbings and street fights where people fought and sometimes died on the streets.

In many respects, the improvisational jazz world of Boetie���s Familiarity is reminiscent of the classic African trickster. And from interviews we conducted in Soweto and Brakpan in the East Rand, with Boetie���s family and friends, evidence suggest that Boetie himself was also trickster in real life. These interviews corroborate archival records, and Simon���s own testimony, presented in the afterword of Familiarity. At times it seems that Boetie may have been fabricating stories to extort money from Simon and other patrons. He told Simon that ���he had no family, just dead sisters��� children who were being looked after by an old woman he had to give money to.��� Yet family testimonies show that when Boetie���s sister, Millicent died, she left her four children with their grandmother Regina.

It was only after Simon met Boetie���s mother, Regina, in hospital that he discovered that Boetie had also lied about her passing when he was a young child. After Simon met Regina, Simon began to describe Boetie to others as ���essentially a con man, so that attempts I have made to establish the facts of his life have led only to chaos and contradiction.��� Perhaps Boetie���s fabrication emerged from the belief that every white person���no matter how sympathetic he may to particular black individuals���benefited from the South African apartheid set-up, and enjoyed privileges based only on color. His own writing suggests as much: ���The white man of South Africa suffers from a defect which can be easily termed limited intelligence. [���] I say this because no man, no matter how dense, will allow himself to be taken in twice by the same trick.���

Boetie���s writing was inextricably bound up with his sensibilities about white supremacy. It was clear to Boetie and other black South Africans that it was hard to fight apartheid system, its racial discrimination and inequality laws. Besides, black people attributed their misery and suffering to apartheid and white imperialism. All these factors suggest that Boetie opted for an alternative way to struggle against apartheid. He used his intelligence and became a con artist.

When Boetie fled, he may or may not have already been at work on his only full-length book, Familiarity is the Kingdom of the Lost. We know little about his creative life during this period and he was on the intellectual periphery of the vibrant Sophiatown arts scene. Boetie���s flight in 1960 was soon followed by that of more distinguished artists, writers, journalists, and musicians. Jazz musician, and composer of King Kong, Todd Matshikiza, successfully relocated to London with his family in 1961, where he published the remarkable memoir Chocolates for My Wife. Lewis Nkosi exited with the support of a scholarship, a result of his collaborations with filmmaker Lionel Rogosin, and soon published Home and Exile in 1965 in New York.

Others not yet famous, but with good connections or clear political allegiances, left South Africa around the same time. The New Age journalist, ANC activist, and future poet laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile went to Dar in 1961. He published Spirits Unchained in Detroit in 1969. Photographer Joseph (Joe) Louw fled in 1962 after being convicted and sentenced for race crimes. He later famously captured the instant Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. Novelist Richard Rive left in 1963, and published Emergency, a fictionalization of the immediate post-Sharpeville chaos enveloping the country, in London. Photographer Ernest Cole fled by first offering to be an informant after he was arrested while photographing arrests for pass violations, and used a group of Lourdes pilgrims as his cover!

Writing in the US in an essay published in the mid 1970s, Moyana declared, ���all the best-known African and coloured writers live in exile.��� Indeed, many, such as Peter Abrahams, Bessie Head, Ng��g�� wa Thiong���o, Alex La Guma, and Wole Soyinka, wrote some of their most memorable work abroad. Many South African performers found fame in exile, notably Miriam Makeba. Indeed, artistic production in exile is a rich African practice, as the poetry of Amadou Bamba demonstrates. But exile was professionally and psychologically counterproductive, as the suicides of writer Nat Nakasa and poet Arthur Nortje demonstrate. While some of the aforementioned lived long enough to return to South Africa after the defeat of the white supremacist regime, with the important exception of key periodicals, such as Staffrider and Purple Renoster, much of the most celebrated anti-apartheid literature was written abroad.

Dugmore Boetie���s exile and future literary notoriety took a different path however to some of the more classic refugee peregrinations. After walking to Dar es Salaam, he simply couldn���t get settled. He then tried and failed to get to London. And at some point, in 1961-62 he made the decision to return to Johannesburg. Ironically, by abandoning his refugee status and somehow finding his way back to the familiarity of Sophiatown he realized the earnest hope of so many exiles abroad. Precisely how he returned to South Africa is still unclear. Upon his return, however, he found kinsmen in Nakasa (editor of The Classic) and Casey Motsisi and promoters in Barney Simon, Nadine Gordimer, Ruth First, and Lionel Abrahams, and he produced his exquisite legacy.

If you���ve not had the opportunity to read Boetie���s picaresque roman �� clef, avail yourself of the pleasure at your earliest convenience. Boetie���s only full-length work, published posthumously, ought to have appeared under the title Tshotsholoza, which many South Africans will immediately recognize as a traditional mining song and unofficial national anthem, immortalized in King Kong. But behind the scenes machinations between Simon and the publisher led to adopting the title of one of Boetie���s short stories. Familiarity is a loosely biographical work, but one that parallels the national story of South Africa���s transition from informal racial separatism in the 1920s to formalized statutory apartheid in the 1950s and 1960s through the eyes of a dispossessed child and destitute young man.

One way to reconcile the real Boetie with his fictionalized persona is to recognize that both Boetie and the fictionalized Duggie knew what it meant to be a ���black survivor��� in the harsh urban Johannesburg. A close friend of Simon whom we interviewed, the actor and director Vanessa Cooke, remembered Boetie as ���a survivor, streetwise, and not scared.��� One gets a similar sense from Es’kia Mphahlele, who described Boetie as ���a representative of the vital, almost unbeatable youth who must survive the continual assaults of white rule as if some malignant fate would have it so.��� Although this further suggests that the real Boetie was indeed a trickster, interviews reveal that he was raised among proudly observant Christians, and he was not uncontrollable. As a result, at least according to family and friends we interviewed, Boetie���s upbringing could not sustain the crimes or any of the other unlawful or violent acts ascribed to his fictional protagonist. Information gleaned from his only surviving friend, the musician Eddie Dlamini, indicates that Boetie mingled with the educated black middle class and he was much impressed by their success.

In the decades since Boetie���s death in a cancer ward in Nqutu in 1966, to the 1995 passing of his editor and collaborator, Simon, critics and scholars have struggled with how to make sense of the work, its contents, and its composition. Is it a co-production? Is it a collaboration? Or is it largely the result of Boetie���s fertile imagination recreating his own experiences and those told him by the tsotsis of Sophiatown? Familiarity is not an easy work to categorize. It certainly does not read like the unapologetic and damning indictments of South Africa authored by his contemporaries, such as Mphahlele and Modisane.

While Boetie did not live long enough to see it in print, he may have authored the only full-length book describing apartheid by a black writer residing within South Africa during the immediate post-Sharpeville period.

August 1, 2021

Wolf in shepherd’s clothing

Nairobi. Photo by Yonko Kilasi on Unsplash.

Nairobi. Photo by Yonko Kilasi on Unsplash. As precarity grows worldwide, many in Kenya are turning to Ponzi schemes that lure them with the promise of inclusive borrowing conditions and returns that will help them realize their dreams. Instead they are the subject of a predatory accumulation that scatters their aspirations, prompts debt and even suicide. The post is republished from The Elephant, the Kenyan news and information website, and is part of a series of selections curated by Wangui Kimari, an editorial board member of Africa Is a Country.

All names in this post have been anonymized to protect identities.

When Michael Kariuki first heard about Ekeza Sacco in 2016, he was quietly excited. He was listening to Kameme FM, the popular Gikuyu language radio station, when host Njogu wa Njoroge began talking about a new savings opportunity live on air. What wa Njoroge described was intriguing. Ekeza���s promise was of a middle-class lifestyle embodied in homeownership, entrepreneurship and family success. Through such radio broadcasts, television adverts and even its own campaign bus, Ekeza exhorted Kenyans to join the Sacco in order to pursue their dreams and aspirations, to use loans for ���putting up a residential house, buying a dream car, purchasing a plot/piece of land, start a business or any other venture.��� Like other Savings and Credit Cooperatives in Kenya (Saccos for short), Njoroge explained how Ekeza was offering its members the opportunity to withdraw three times the amount of their savings in the form of a loan.

But there was an important twist to Ekeza���s offer, one that gave members a distinct advantage. Unlike other Saccos, Ekeza was offering loans without the need for guarantors���other Sacco members who personally put up their savings as a guarantee for another member���s loan. Instead, at Ekeza, the title deeds and logbooks of the properties and vehicles that members would eventually purchase with their loans would act as loan securities. In other words, Ekeza was offering easy access to capital that is hard to come by in contemporary Kenya where banks charge high interest rates and Saccos require social membership. For Kariuki, that a guarantor was not required made saving with Ekeza an attractive opportunity���the chance to obtain capital that would allow him to purchase a car and become a taxi driver without having to undertake the difficult task of finding other Sacco members to stand in as his guarantors. Along with thousands of other Kenyans, Kariuki soon joined the Sacco.

A construction worker who worked long, hard days in the heat of Mombasa, Kariuki went on to save KSh180,000 with Ekeza over the next two years, sending money to his Sacco savings account directly from his MPesa account on his mobile phone. It was the first time in his life that Kariuki had ever saved such a large amount of money. He told me of the sacrifices he and his family made so that he could put more of his earnings into his savings, that there were ���some things������basic necessities and even food���they had to forego in the hope that his savings, and the taxi business that he would start with the loan, would allow him to build them a better future.

But in December 2017, Kariuki started to realize something was wrong. He had gone to withdraw a loan of KSh25,000 from the Sacco���s office in Thika. After filling out the paperwork, he was asked by Ekeza staff to wait the normal 60 days that it would take for the loan to be cleared and arrive in his account. Kariuki went back to Mombasa and waited, but his loan never arrived.

In January 2018, he returned to the office to find out what had happened with his loan. Ekeza staff assured him that his loan was on its way and he was asked to wait again but this time Kariuki refused. Suspecting something was wrong with the Sacco itself, he asked to withdraw all his savings at a fee of KSh1000. Kariuki filled out the paperwork and was once again asked to wait for 60 working days for his savings to reach his bank account.

In March 2018, four days before he was due to receive his savings, Kariuki���s wife called him. She had seen on the news that Ekeza had been officially deregistered by the Kenyan government pending investigations into its accounts. With the SACCO���s accounts frozen, Kariuki could do nothing but wait; he returned to the Ekeza office three times in 2018 and 2019 asking about the status of his savings, to no avail. Like tens of thousands of other Ekeza members, he has been stuck in limbo ever since.

The Ekeza Sacco storyMichael Kariuki���s story is a fairly common one for members of Ekeza Sacco���that after carefully building their savings for around two years, they were finally on the brink of receiving a loan, only to find it constantly delayed before eventually discovering that the SACCO had been deregistered by the government. But even Kariuki���s story is just one aspect of the Ekeza debacle. Other Sacco members reported how Gakuyo ���bought��� land from them without ever paying them in full. Others had their land and vehicles seized even after repaying their loans in full. All told, members lost around KSh2.6 billion in savings.

In March 2018, Commissioner of Co-operatives Mary Mungai formally closed Ekeza pending an investigation and an audit of the Sacco���s accounts. Suddenly, the Sacco���s 53,000 members were plunged into confusion and concern about the fate of their savings. The Sacco���s chairman, David Ngari Kariuki, an evangelical church pastor known as Gakuyo, assured members that their savings were safe. However, an audit of Ekeza���s accounts revealed around KSh1.5 billion of irregular transfers to bank accounts of persons and businesses associated with the chairman.

The audit report revealed fraud on an enormous scale but little has been done to address the plight of the members who have lost their savings. Over the last two years, Ekeza has maintained that its liquidity was damaged by rumors rather than Gakuyo���s expropriation of funds. In the aftermath of the Commissioner���s audit, Ngari moved to sell several of his assets and has repeatedly assured members that their deposits will be refunded, announcing a new 5-tier schedule for doing so in January 2020. Audaciously, Ekeza offered its members plots of land in what were seen as sub-par locations, their monetary worth far below what members had invested. Whilst Ekeza insists that it has refunded thousands of its members, particularly those with savings worth less than KSh50,000, reports from Ekeza victims suggest that there are many more thousands who are yet to receive their money. On social media, victims��� groups continue to organize, but with waning hope that they will ever see their money returned.

Over the past three years, I have been exploring the effect the fallout of Ekeza���s deregistration and the subsequent uncertainty faced by its members. The majority live in muted hope, actively choosing not to think about the money because of the stress the loss of their savings has caused them. Marriages have been ruined. Some Ekeza members have committed suicide after losing their savings. The overwhelming story is one of bitterness and anger towards Ngari. The words of the man I have anonymized in this article as Kariuki give some sense of that bitterness:

If I could be like a soldier holding a gun, I could be searching for that man just to kill him and leave everything. If I die, I die. Because that money, it was my first time to enter into a SACCO, save things. I have never saved an amount like that.

This article aims to recap the story of Ekeza Sacco���how it came to prominence, how its deregistration has shaped the lives of its members, and how its collapse reveals the illusory promises of the ���working class��� dream in contemporary Kenya, how aspirations of leading better material lives are undermined by political authority. The story of Ekeza Sacco is not merely one of fraud, but also one of frustration and anguish with a contemporary Kenya that works for the powerful few, depriving ordinary citizens of the material basis on which they might build their dreams.

The rise, the fall, and the resistanceEkeza Sacco was established in 2013 and formally registered in 2014, but it rose to prominence in the run-up to Kenya���s 2017 elections. Throughout the first half of the year, the Sacco was regularly advertised on Gikuyu language radio stations like Kameme FM alongside its partner firm, Gakuyo Real Estate. During the same period, Ngari attempted to vie for governorship of Kiambu, but eventually joined Ferdinand Waititu���s ���United 4 Kiambu��� team, an alliance of Kiambu politicians (including current governor James Nyoro) through which Waititu contested and ultimately won the gubernatorial seat. Through his association with Waititu, Ngari appeared at rallies across the county throughout 2017. At the time, friends and acquaintances of mine in Kiambu were optimistic of the impact Ngari would have on the county through his association with the prospective new governor. ���He will be the one bringing development, I am sure,��� one Kiambu farmer told me.

At the same time, an Ekeza Sacco-branded mobile truck was traveling around Kiambu exhorting people to ���Invest to nurture your dreams.��� ���His adverts were so convincing,��� one member told me. Another told me how Ekeza���s near-ubiquitous presence made him believe in its legitimacy. ���It was everywhere during the elections.��� Whilst the new Sacco gained prominence and legitimacy through its relentless advertising campaign, for many of those who joined the Sacco in 2016 and 2017, it was Ngari���s status as a pastor that helped earn their trust. ���Because he���s a bishop. He has a good reputation. So I thought my money was safe,��� one member reflected. Others found out about the Sacco through family members. Ann Njeri, a 30-year-old woman from Githurai, found out about the Sacco through her mother-in-law, and soon encouraged her husband to invest in the Sacco to save for a plot of land. For Njeri, ���It was a normal Sacco just like others but at least this particular one had been started by a bishop so it had more credibility.��� She convinced her husband that they should invest in Ekeza in order to buy a plot of land in Nairobi���s outskirts on which to build a home. The couple went on to save KSh500,000 with the Sacco.

For many of the people who joined, Ekeza offered easier access to capital than some of its competitors. As mentioned above, one of the main advantages of saving with Ekeza was that it did not require members to have guarantors for their loans. ���They weren���t even asking for security in the case you were taking a loan to buy land from the sister company, Gakuyo,��� one member explained. ���They would just wait until you pay the full amount before giving you the title deed, and that was my strategy then.��� Members contrasted the ease of entry into Ekeza with the difficulty of becoming a member of what are viewed as more successful and legitimate Saccos such as Mwalimu Sacco. Another member reflected how difficult he thought it would be to join Mwalimu Sacco compared to Ekeza. ���I have to have some friends there.���

Ekeza Sacco promised ordinary Kenyans the chance to live their dream as members of Kenya���s fledgling middle-class. ���Invest to nature [sic] your dreams,��� read one of the Sacco���s slogans. Many Ekeza members were attracted by the prospect of acquiring land���either to build a home to live in, or to rent out in order to supplement their incomes. In this regard, Ekeza���s popularity ought to be viewed in the light of Kenya���s current ���gold rush��� on land���the idea that land in Kenya is ���getting finished,��� ever increasing in value because of its growing scarcity. It is precisely the same scarcity-speculation combination that fuels elite land grabs.

But it was partly through the purchase of Gakuyo Real Estate plots that members began to discover that their investments were flawed. Gakuyo Real Estate���s practice was to buy large plots of land and sub-divide them into individual plots for the construction of stone houses. But in some cases, members would arrive at their new, loan-purchased plots, only to find that the original owners still held the title deed. It was also revealed that Gakuyo Real Estate was in the practice of purchasing land via installments and allowing members to access their land before completing the payment to the original owners. Some Ekeza members were denied ownership of plots that they had paid for because the Sacco had not paid for the plots in the first place.

For others, it was in far more mundane circumstances that they began to realize something was amiss. One member, Andrew Mwangi, arrived at the Ekeza office in Thika one afternoon in early 2018 to find a commotion at the front desk. Another member was complaining that they had filed for complete withdrawal of their savings and had waited months but received nothing. Mwangi was alarmed. ���I immediately filled the withdrawal form.���

The deregistration of the Sacco by Mary Mungai in March 2018 opened a new phase in the Sacco���s lifespan���a political struggle for its control. Not prepared to wait, Ekeza members quickly organized themselves into victims��� groups. Under the leadership of Charles Mage, one group of Ekeza Sacco members stormed the Sacco���s office in Thika. Soon enough, the police took note and in March 2019, Ekeza victims were invited to the Directorate of Criminal Investigations on Kiambu Road to record statements.

For its part, Ekeza maintained that its collapse had been caused by ���panic withdrawals“���that the Sacco���s reputation had become a ���political tool��� in the 2017 elections, a target for opponents who had raised doubts amongst the membership, causing a raft of withdrawals and a liquidity crisis. The Sacco described the situation as a ���mishap.��� No mention was made of the immense suffering caused to members through the loss of their savings. The message to members was: ���bear with us.��� In 2018, Sacco members with smaller amounts of savings���KSh5,000 and below���were refunded, but it left around 53,000 members with substantial savings still waiting.

More significant shifts were to come. At an AGM in February 2019, overseen by the Commissioner Mary Mungai, Sacco members voted to remove Gakuyo and put a temporary board of five people in charge, including Charles Mage as acting Chairman. At the same time, the Commissioner reinstated the Sacco, with the intention that the new interim board would begin refunding members��� deposits.

This moment of optimism quickly passed as Ngari���s lawyers moved rapidly to challenge the new board���s appointment in the courts, citing the possibility of members��� savings being plundered by the new committee. The court issued an injunction, and its effect was to return power to Ngari, locking out members who thought they were on the cusp of regaining control of their savings through access to the Sacco���s bank accounts. At several meetings in 2019, Ekeza Sacco members debated their predicament; the interim committee now had no control over the Sacco���s accounts, the offices were closed and no form of redress was available. The atmosphere at these meetings was combative.

But by 2020, the resistance of Ekeza Sacco victims��� groups had begun to weaken. The death of Charles Mage in a road accident in March 2020, an event that went unreported in national media outlets, further weakened the leadership of members who want to see their savings returned. Whilst some members are preparing court cases against the Sacco in 2021, arrangements are increasingly being made in private rather than through collective action, with Ekeza victims wary of being spied upon by members of ���Gakuyo���s team.��� Meanwhile, Ngari has re-emerged as a figure close to James Nyoro, promising a bigger, better Ekeza, assuring members that refunds are on the way. Ekeza victims have found their plight politicized, used as a football in Kiambu���s politics. Ngari has blamed the failure of his Sacco on Ferdinand Waititu, the now disgraced former governor of Kiambu, claiming that Waititu used Ekeza funds in his campaign.

Lives in limboThe Ekeza debacle is characteristic of a contemporary Kenya defined by an ���unequal capacity to secure a future.” It is emblematic of how those in political authority cannibalize the aspirational projects of ordinary Kenyans, ���eating their sweat.��� ���We are ready to prosper here in Kenya, bwana Peter,��� one Ekeza member told me at a victims��� group meeting on Thika Road. ���It is our leaders who cut us. These people who lead us are not honest, they just deceive us.���

For Ekeza members, the immense difficulty in generating savings and capital for aspirational projects compounds the sense of loss. Most Ekeza members I spoke to described themselves as ���hustlers,��� working long hours for uncertain wages in the informal economy. Their struggle is evoked here by Andrew Mwangi:

You know I lost a lot of money. And you know, I was thinking about that thing each and every day. And I was thinking, maybe we will get our money back. Finally, I came to find out we are not being paid at all. So I told myself I will never think about it again. I agree, the money is lost. And up to now, I don���t engage in any way [with the Sacco]. I just left it like that. I���m sick and tired, I���m tired. I don���t think about that any more. Every time I talk about it, my heart bleeds. That was my money. That was my sweat. I worked so hard for it. My goal was to own a property. That was my dream. My dream was broken by this guy ��� I even hate mentioning the name. So what I can say is that I do not even follow the money anymore.

Michael Kariuki���s words strike a similar tone:

My faith is still there. But I can���t put all my faith in there. I have to work, feed my family, do everything. I can���t put all my mind there, thinking about all that money I saved and it went. If it got lost, it got lost. So, I���ll never get it back. But, for the rest of the victims are just struggling if the money will come. If I stay thinking about the money, I���ll just get sick.

Whilst their words belie a remarkable capacity to move on, for most members the fallout from their loss has been blame within their families. Ann Njoki told me how her husband was understanding, but how other Ekeza members she knew had ended up divorced as a result of losing savings, facing the blame from their partners for the loss of family money.

Meanwhile Ngari continues to walk free, having faced no charges from the DCI, working now as advisor to James Nyoro in the Kiambu County government, a state of affairs that some Ekeza victims find not only frustrating but also insulting���indicative of a Kenya that works for the privileged few, rather than the common mwananchi.

Up to now, he���s in this government, of which even Kenyan government is not bothering about these people who saved their money in that account. It is not bothering with. The chairman now is just talking and talking nonsense of which the government is not bothering anything.

These frustrations extend beyond Ekeza itself to perceptions that Kenya has failed as a place in which one can live and better oneself. A 24-year-old friend of mine from Ruaka who lost KSh64,000, his entire savings, was despondent. ���This is Kenya, man,��� he told me. ���Most likely the politicians have been given something to make sure nothing happens. If I had a choice of leaving this place, I would definitely do that.���

Warnings for the Sacco sector���Limited liquidity is holding SACCOs back from becoming specialised housing finance providers���or mortgage SACCOs (SAMCOs)���like the saving and loans and building societies in industrialized markets,��� remarks a recent academic paper on housing finance in emerging markets. ���It is therefore critical for SACCOs to deepen deposit-taking activities.��� Ekeza Sacco might be an outlier case���an instance where a particular ���fraudster��� has deprived members of their savings. As a recent report by FSD-Kenya reiterated, a single case of fraud need not lead to fears that the Sacco sector is fundamentally flawed.

But there are important lessons to learn from the Ekeza Sacco story. As the FSD report noted, the increased size of Saccos ���comes at the cost of it becoming increasingly difficult for members to look after their own interests directly; to ensure that the management and boards of the SACCO are not taking undue risks or worse.��� In order to increase that membership, Saccos like Ekeza begin to look ever more like Ponzi schemes, their business models based on the recruitment of new members and the sale of a dream, rather than community banking. This was a point not lost on the late Charles Mage.

���The SACCO is not meant to be managed by one person,��� he remarked to me when we first discussed the Sacco in August 2019. ���This guy [Gakuyo] was making all the decisions as if it���s his own company.��� As Mage put it, Gakuyo was withdrawing funds from Ekeza ���any time he wanted,��� buying plots and buildings, building hotels. As he found out in the Commissioner���s audit, ���there was a time the SACCO���s account went down to 0.���

If Saccos can enter the market already in the hands of wealthy and politically connected individuals, and members can be recruited ad infinitum, the scene is set for Kenya���s elites to use them as vehicles for predatory accumulation. Stronger and more interventionist regulation is required to ensure internal transparency���that there are proper lines of communication between members and boards. If Saccos chase greater liquidity through ever-increasing membership, further regulation and oversight from members will be imperative. Recent research suggests that Ekeza evaded regulation through setting up in different counties.

But despite the early action of Sacco Commissioner Mary Mungai, the eventual lack of government action has already damaged the trust that regulators are up to the task. Many Ekeza members say that they have lost trust in the Sacco sector, vowing never to save with one again.

Fault lines and futuresMore than a story of individual fraud, the Ekeza debacle reveals the fault lines in the false promises of contemporary Kenya. Whilst politicians and business leaders promise Kenyans wealth and prosperity, they are able to manipulate institutions to their liking, consuming the sweat of those who work while avoiding sanction. Ordinary Kenyans find themselves struggling for better lives without any such advantage. When one looks at the Ekeza case, fears and suspicions of theft seem justified, anti-elite sentiment vindicated. The cynicism and hopelessness, depression and suicide that have followed in the wake of the Ekeza collapse are hardly surprising. When one struggles in the informal economy, only for one���s savings to be ���eaten��� by a self-proclaimed pastor, when national and county governments practically ignore your plight, what can you do? It is little wonder that William Ruto���s ���hustler��� narrative is gaining traction when frustration is brewing over the way things work in ���hii Kenya.��� If the Ekeza collapse has provoked immense anguish, it has also fueled Kenyans��� desire for a different Kenya���one where institutions work in the interests of the citizen, of the ���hustlers.��� Regardless of its as yet unknown trajectory, Ruto���s ���hustler��� narrative promises Kenyans that a new Kenya is at hand. Without understanding injustices like Ekeza, palpably and materially felt, we cannot appreciate the new calls for justice and an end to the ���dynasties��� that Ruto���s campaign now promulgates.

July 31, 2021

A terrifying vision of South Africa’s future

Downtown Johannesburg (Photo: Vladimir Varfolomeev, via Flickr CC).

Downtown Johannesburg (Photo: Vladimir Varfolomeev, via Flickr CC). Predicting a major political shockwave has been standard fare among South African pundits for some time. The sheer depth of the socio-economic crisis in the country, best encapsulated in a broad unemployment rate of 42%, made it something of a safe bet.

Recently that shockwave arrived, but in a form that was perhaps less expected. It���s trigger was not the increasing prices of necessities or the failing provision of basic services. Instead it was the jailing of former president Jacob Zuma, the man arguably most responsible for the parlous state of those services. It���s embodiment was not mass occupations or demonstrations against an indifferent government. Instead it was the widespread looting of shops and malls, tinctured by outbursts of ethnic violence and outright criminality. It was not civil society organizations or radical opposition parties that led the unrest, but a faction of the ruling party itself.

This has made it far harder to grasp the political meaning of these events and to anticipate their consequences. Amidst a flood of analysis and reporting, interpretations of the unrest, not least within the Left, continue to diverge sharply.

There is a general consensus that the unrest had these two main facets. On the one hand a seditious campaign waged by Zuma-aligned elements (henceforth Zupta) intended to sow instability. On the other, a more spontaneous attempt by desperate people with little or no connection to Zupta ,to secure food and basic necessities���a ���bread riot.��� But that consensus breaks down on the question of how to understand the interrelation of these facets and the relative importance of each in the overall arc of events, and thus how to characterize the episode as a whole. Most commentators have tended to strongly foreground one side or the other.

A widely circulated editorial published on July 12 on the South African website, New Frame (NF), put the emphasis firmly on the latter element. It argued that the influence of Zupta forces, beyond tossing the initial match, was marginal. Reports from NF���s journalists suggested that a substantial majority of those taking to the malls and streets had been driven there by desperation rather than any concern for Zuma. Consequently NF saw the unrest as infused with progressive potential and drew analogies to the bread riots that preceded revolutions in the Middle East and Europe. It saw some chance that they may evolve into a more overtly political mobilization, cohered around a clear set of demands, and even that middle class and other elements may join in on this.

Subsequent posts over the following days by NF editors, sounded a somewhat different note. By this stage, widespread reports of deliberate acts of sabotage targeting strategic infrastructure, as well as a flood of anecdotal evidence pointing to the intervention of well-organized groupings, appeared to show that Zupta forces were more than simply the pilot light for the unrest. Yet NF still drew a very strong distinction between its two facets, contending the acts of sabotage were an entirely ���different phenomena��� from the food riots and that the latter were ���spontaneous … emerging from widespread desperation.���

Writing in Jacobin on July 15, the historian Ben Fogel bent the stick in the other direction. Although not denying that simple desperation was a motivation for many on the streets, he firmly denied that these events could be characterized as ���bread riots.��� Instead he saw them as a part of a deliberate political campaign with clear objectives. In contrast to NF, he emphasized the ethnic and xenophobic dimensions of the unrest. While the title of NF���s editorial announced somewhat loftily that the riots had ���turned the wheel of history,��� Fogel���s exuded pessimism, declaring there to be ���no silver lining��� to what had transpired.

These diverging interpretations seem to arise partly from a dispute over facts, specifically about what caused the unrest. New Frame sees it as having been a spontaneous outburst with distinct organized currents, Fogel sees it as having been orchestrated. Clearly, it was neither one nor the other. It could not possibly have been purely spontaneous because we know at the very least that there were active instigators. At the same time we know it had spontaneous elements; it drew in a great mass of people who were acting at their own behest and for their own objectives. The real question then is about the degrees of orchestration and spontaneity.

We are not yet in a position to know precisely what those were. But as more information is becoming available, it does seem to be pointing to a higher degree of orchestration than appeared to be the case at the start. Leaked WhatsApp messages testify to a very active role played by ANC counselors and other local leaders. They suggest that shopping malls were deliberately targeted because they constituted symbols of ���white monopoly capital.��� Anecdotal evidence points to the widespread busing in of looters and the involvement of well-resourced gangs in bussing out stolen goods. This also encompassed various harder to reach (and typically well-secured) targets, including warehouses, factories and shipping containers, some of which appear to have come under coordinated attack.

The geography of the uprising also suggests the importance of organized elements. If the unrest had been driven by people acting autonomously, based on a ���demonstration effect,��� we would have expected it to be quite diffused. Instead it seems to have remained concentrated in areas where Zupta elements have influence.

It now appears that many of the reports of attacks on water and communication facilities were false. But a number of other incidents, such as the burning of a chemical plant, attacks on transport and food infrastructure and the theft of ammunition depots, still indicate orchestrated subversion unfolding under the cover of the chaos.

Given all this, NF���s insistence that the two facets of the unrest should be seen as ���distinct phenomena��� is an odd one. Its point, it seems, is political rather than sociological. The intent, I think, is to ringfence the actions of the mass of rioters from those of the instigators in the name of preserving the former’s agency and progressive potentiality from the sordidness that started to overtake events as they progressed. Normatively that may be a valid move. But emphasizing distinction too strongly as we try to come to grips with the political meaning of these events is, in my view, a mistake for several reasons.

First, doing so once again imputes a degree of autonomy and spontaneity to the riots for which there simply isn’t justification. This isn���t solely a concern for historians or academics. Understanding the precise role of active legitimation and orchestration in driving people onto the streets may be important for many of the bigger conclusions we will draw from these events. It will have a large bearing, for example, on what we think the riots tell us about the political mood of working class people in the country more broadly, and of the likelihood of similar occurrences.

Second, the fact that the riots took place under the aegis of the ���Free Zuma��� campaign is not irrelevant to understanding the political impacts they will have, or the interpretive frames that will be applied to them by other social actors. I argue in some detail below that the overweening influence of the ANC on both sides of the contest inhibited the capacity of the riots to organically develop their own political direction as NF hoped.