Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 118

September 30, 2021

African cinema into the future

A still from Alain Gomis's Felicite.

A still from Alain Gomis's Felicite. With COVID-19 further impeding the stability and growth of cinema across Africa, it is imperative to promote self-expression and look to the work of filmmakers such as Bassek ba Kobhio and Alain Gomis as models that already exist and would benefit from funding to build and maintain editing and production studios. If global streaming giants want to stand out as promoters of diversity, equity and inclusion, they must invest more resources in African cinema to compensate for the shortcomings of a purely commercial approach to streaming.

The economic and social impacts of the pandemic will undoubtedly be felt for years to come. Like elsewhere, African countries have seen cinema closures, shoots shut down, unpaid actors and technicians, and additional job losses. As African Film Festivals streamed online across North America and Europe and streaming platforms expanded, questions around the future of African cinema have taken new forms. Let���s look more closely at what streaming could offer African cinema in the future; but also, why Euro-American global business models may have serious shortcomings.

African cinema refers specifically to the seventh art���that of cinema���which has historically been crafted on celluloid film by its directors, or auteurs, whose aims have been for Africans to project images of Africans and to inspire thoughtful reactions from viewers, as opposed to Hollywood filmmaking, which is meant to entertain. Nollywood, which emerged as a popular industry in the 1990s, has stood in stark contrast to auteur filmmaking for its video format and aim to entertain.

In many ways, streaming would appear to be the most viable solution for disseminating and screening movies as well as series and other TV programming at once across and beyond the African continent. It is not surprising that global media giants, such as Netflix, have capitalized on confinement and expanded their subscriptions by millions. Meanwhile, other streaming platforms, including Showmax, Iroko TV and TV providers Canal+ Afrique have tried to remain competitive during the pandemic despite layoffs. However, the Netflix approach may have negative impacts for African cinema���s future for several reasons.

Currently, many people who have Internet access on the continent (only about 22% of the total population) may have insufficient bandwidth to stream and/or the money to subscribe to streaming services. As Franco-Senegalese filmmaker Alain Gomis has wisely stated: ���International success often masks realities on the ground.���

For instance, in one of the continent���s largest economies, Nigeria, streaming services cost the equivalent of USD8 per month, which is enough to buy more than 14 pounds of rice. In the DRC, in addition to being prohibitively expensive, there is almost no capability for streaming throughout most of the country���an example of broadening, rather than narrowing, economic inequality.

Programming is predominantly Hollywood or European content, similar to what France exports through its Canal+. In Senegal, for instance, Netflix shows Kobra Kai, The Karate Kid, American History X, The Fast and the Furious, or French crime films like Balle perdue. One of the few African films streaming on Netflix in Senegal is French filmmaker Jean-St��phane Sauvaire���s misrepresentative adaptation of Emmanuel Dongala���s novel Johnny Mad Dog. Even Netflix���s Africa Originals are dominated by Western media formats, such as police thrillers, dramas, or romantic comedies. Further, the vast majority of the Africa Originals are not getting to Netflix subscribers on the continent, in spite of Netflix Head of Africa Originals, Dorothy Ghettuba���s statement that Netflix Africa���s aim is, first, content for African subscribers and, second, for the rest of the world. In fact, it���s the opposite. Of the more than 30 countries where films like The Mercenary, The African Doctor, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, Tsotsi and Mati Diop���s Atlantics are streaming, none of them is available on Netflix in any African country with the exception of South Africa.

Pandemic or not, African cinema continues to face the two-pronged issue of production and distribution today, 60 years since its beginnings. This has to do with the larger problems of lack of (cinema) industry and financial support for the development of cultural institutions and regional collaborations, such as the short-lived Inter-African Consortium of Cinematic Distribution (CIDC), which shut down in the early 1980s. Specifically, training facilities are lacking not only for camera operators, actors, writers and directors, but also for editing and�� editing and production equipment (studios). Movie theatres were already few and far between before COVID-19.

There is much churning and abuzz with regard to cultural production on the continent, which would flourish if given more funding. There is barely support from governments in Africa and the situation is now even worse because of COVID-19. Further, Abderrahmane Sissako notes that with Europe���s closed borders, it is quite hard for Africans to go there and develop filmmaking techniques, skills, and education. Models that are primed for such developments already exist and would benefit from funding to build and maintain editing and production studios. The closest today are described, like Gomis does, as a collaboration of ���government officials and professionals from the film and audiovisual field��� and are the fruits of intense work and networking over decades in some cases. For instance, Bassek ba Kobhio���s ��crans Noirs festival, which over the past 23 years has grown and had success not only as a festival, has also been instrumental in training actors and directors, promoting local cinema in the Central Africa region, as well as from across the continent.

Taking a similar approach in building the Yennenga Center in Dakar, Gomis makes the point that only local Senegalese who have international connections are likely to make it in the industry, whereas one of his goals is to achieve options even for those who are not able to study or train internationally. Gomis underscores that teaching and training must be experiential, particularly in the context of the differences between learning cinema in France and in Senegal, where in the former one learns in the classroom and eventually has plenty of movie theaters to show their films yet in the latter the situation is but theoretical and must be translated to the needs of Senegal.

Some government programs, such as USAID���s Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI), have contributed positively to the development of the cinema industry on the continent. In Niger, for instance, A��cha Macky, an award-winning documentary filmmaker and founding CEO of production company, Production Tabous (Taboo Productions) has benefited from such funding support. In turn, her organization has donated several films to Nigerien television during the pandemic.

On policy and promotion of culture, as Alain Gomis points out, ���if film and cultural property are considered to be mere opportunities for financial gain or success, they lose their impact.��� Furthermore, as he indicates, diversity on the screen ���makes cultural diversity possible.��� It is also a good way to recognize African contributions to culture through art, and to elaborate on how African Americans have inspired Africans and vice versa.

As we consider possible futures, including streaming, for African cinema, it is essential to acknowledge that developing such industry in African countries is a complex endeavor, which requires institutions to be built, education and communications technology to be enhanced, with the ultimate goal of supporting filmmakers and valuing human life through telling human stories.

Alpha Cond��, undone

Image credit Nomi Dave.

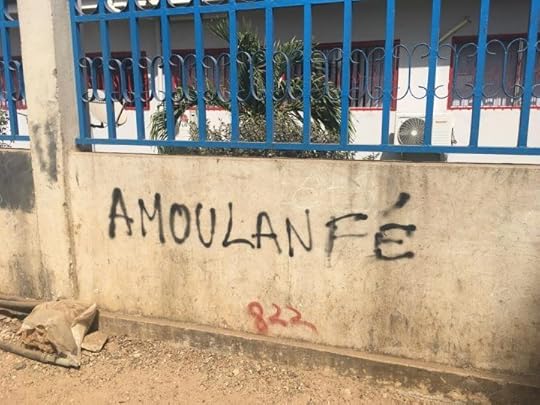

Image credit Nomi Dave. Perhaps the most���if not only���surprising thing about the recent coup d�����tat in Guinea was the images that quickly circulated on social media of ousted president Alpha Cond��. Cond��, who usually appears in public immaculately groomed, was filmed and photographed looking disheveled, unshaven, and hastily dressed. A mobile phone video shot by a member of the military junta that deposed him shows Cond�� slumped down in his private quarters, barefoot in jeans and a partially buttoned shirt with his undershirt clearly visible. He scowls at the camera as young, heavily armed soldiers surround him and one asks him to confirm that they have neither touched nor abused him. Cond�� remains irascibly silent, seemingly both infuriated and resigned. Surely, as many Guineans feel, he knew this day would come.

In October 2020, Cond�� oversaw an election to amend the Guinean constitution to allow him to sit for a third term in office. The move was volcanically unpopular, with months of protest and violence in the run-up and accusations that it symbolized a new dictatorship in Guinea. Cond�� had originally come to office after Guinea���s first democratic presidential elections in 2010, victoriously declaring that ���Guinea is back!��� At the time, many referred to Cond�� as ���le professeur��� because of his previous career in public law in France. But Cond�� quickly proved his dictatorial credentials. His government cracked down on opposition supporters, stifled dissent, and oversaw shady contracts with foreign mining companies. For the past two years, the streets of the capital Conakry have been sprayed with graffiti calling on Cond�� to leave. Few in Guinea will now mourn his departure. Yet, as the journalist Moussa Y��ro Bah suggests, those who opposed Cond�����s third term wanted in part to avoid this shameful fate for the president, who has now been ���shown to the world as a badly dressed, crude, common man.��� Her statement zooms in on the mobile phone images and their humiliating power that cannot be undone or unseen. Cond�� is the emperor in his new clothes, dethroned and disrobed before the public.

Fashion matters to politics. Politicians and leaders carefully compile and curate their sartorial image as a mode of public persuasion. Guinea���s first president, S��kou Tour��, strategically shifted his preferred formal dress from a European business suit to a West African duruki-ba (damask robe) in the mid-1960s, as his regime increasingly honed its anti-imperialist, revolutionary ideology. Tour�� also famously dressed in white as a form of spiritual power and a symbol of purity���and he expected his citizens to do likewise. As this example shows, the politician���s power is further actualized and projected outwards through the dress of others. In fact, the only time I personally ever saw Alpha Cond�� was at an electoral campaign rally in 2009, where partisans were dressed in clothing featuring Cond�����s face. Fashion creates spectacle, allowing power to be concentrated in the figure of the well-dressed leader and to radiate outwards to envelop and be reflected by those around him.

Image credit Nomi Dave.

Image credit Nomi Dave.Yet alongside the power of dress is the shame-laden, gendered power of undressing. As Naminata Diabat�� details in her work Naked Agency, shame is a potent social force in many African contexts, stemming from the understanding that individuals are collectively constituted. What others say, think, and feel about someone matters greatly. Shame is therefore strongly linked to public presentation, clothing, and the body. Women may be forcibly stripped of clothing as an act of disciplining, but women also can wield their nakedness as a source of power, a weapon with which to shame others. Diabat�� shows how female African protesters have deployed this power through strategic nudity in actions across the continent. This gendered notion of shame suggests, however, that men have no such power in a state of undress. Instead, they are simply exposed and undone.

Returning to the recent images from Guinea, we can further read into the spectacles of dress that were on display. Juxtaposed with the imagery of the badly dressed Cond�� were the photographs and videos of the junta leader, Mamady Doumbouya. Doumbouya appears in military fatigues, combat boots, dark sunglasses, and a red beret. This image instantly elicits parallels with Guinea���s previous coup leader, Moussa Dadis Camara, who came to power in 2008. Dadis Camara also had a penchant for sunglasses and red berets, evoking revolutionary heroes such as Che Guevara and Thomas Sankara, as Garhe Osiebe has recently noted. Dadis Camara was hailed as a liberation hero in Guinea when he seized control of the government twelve years ago���much as Doumbouya and his junta have been in the past three weeks. Yet Doumbouya would do well to remember the fate of Dadis and his regime, which imploded within months following political violence and popular anger. So far, Doumbouya is aware of this history, stating, ���We will not repeat the mistakes of the past,��� and appearing on Guinean television draped in the national flag to underscore his patriotic credentials. It remains to be seen, however, just how the new military regime in Guinea will fashion its and the country���s future.

September 29, 2021

Alpha and Omega

Public domain image.

Public domain image. In an update to our regularly scheduled programming, we will no longer be hosting AIAC Talk as a live video show. Instead, we will be focusing on the podcast audio medium. However, that means that AIAC Talk is now finally available on all of the major podcasting platforms such as Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher. Use our new RSS feed to subscribe via your favorite platform, or search “AIAC Talk” within their system. We will still make short video excerpts available on our YouTube channel.

Additionally, we have decided to retire our Patreon account. If you would like to financially support AIAC Talk, or Africa Is a Country in general, you can now do so via one time or monthly donations. Thanks to all the regular listeners and supporters, and keep an eye out for more exciting news soon!

In the kick off to Season two of AIAC Talk, Will Shoki and Sean Jacobs speak with Siba N���Zatioula Grovogui, a professor of international relations theory and law at Cornell University on the recent coup in the West African nation of Guinea-Conakry. On September 5, 2021, the country’s first democratically-elected president, Alpha Cond��, was deposed in a coup led by the country���s armed forces. When elected in 2010, the man once affectionately known as ���Le Professeur��� promised to undo the pattern of political violence that had long destabilized the country, as well as to deliver basic services and development to all. However, after successfully changing the constitution to allow him a run for a third term (and winning it in a disputed election in October 2020), the signs of creeping despotism were clearer than ever.

In Africa Is a Country last April, Grovogui wrote that ���Guinea, more than ever, needs an inclusive debate not only on the function of the state, but also on the nature of our institutions and therefore the very state of the republic.��� The debate is all the more necessary now, and on this episode, we hope to unpack the roots of Guinea���s political crisis, as well as to ask: what comes next?

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/ab4ca57b-0baa-4ef4-a3b4-e0b977a84114/aiac-talk-47-audio.mp3Will Africa be the last oil frontier?

Photo by Yasmine Arfaoui on Unsplash

Photo by Yasmine Arfaoui on Unsplash A major struggle over resources is unfolding in Southern Africa. In the wildlife preserves of the Okavango delta���home to 200,000 people and spanning parts of Namibia and Botswana���a Canadian oil company is drilling for oil over the fierce opposition of indigenous people, activists, and environmental experts. The company, Reconnaissance Energy Africa���known as ReconAfrica���has a plan objectionable to virtually everyone except its investors and Namibia and Botswana government partners, who have granted permits for exploratory tests: it promises to unleash untold levels of pollution, destruction of water supplies and farmland, the eviction of residents from their land, and permanent harm to animals, including endangered species. ReconAfrica���s rush for what they are calling ���largest oil play of the decade��� is nothing short of devastating, profit-fueled extraction, with strong echoes of Africa���s colonial past.

ReconAfrica: Drilling at any costIt���s difficult to overestimate the destructive potential of ReconAfrica���s plans. Investigative journalists, area residents, and activists have accumulated a vast body of evidence of the dangers to Okavango, demolishing the company���s claims to adequate safety measures. As a result, resistance to the drilling plan is growing, along with international attention. National Geographic launched a series of articles in the fall of 2020 condemning the immense threats posed to the wildlife, livelihoods, and environment in the region. Among the most serious is the potential for water contamination, in an area with scarce water supplies. The Okavango is a wetland fed by an inland delta, the region���s major water source. As the one of the articles explains, ���Any contamination to the aquifer will be all but impossible to contain and clean up.��� ReconAfrica���s license to explore lies adjacent to the main river of the Okavango delta, and exploratory drilling is being carried out 160 miles upstream. Critics of the project have raised serious concerns about the lack of analysis in the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of the effects on ground and surface water, especially given the vast amount of water that drilling requires. In fact, the dangers posed to the water supply affect not only Okavango, but roughly half the population of Namibia, a largely arid country where the river supports the water security of more than one million people. Namibia has already experienced frightening degrees of warming, at a rate outpacing that of other regions.

The National Geographic series lays out, in painful detail, the danger posed to the area���s wildlife:��

The Okavango region is home to the largest herd of African elephants on Earth and myriad other animals���African wild dogs, lions, leopards, giraffes, amphibians and reptiles, birds���and rare flora ��� including important migratory routes for the world���s largest remaining elephant population ��� Wild animals use the entire region, which is why Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have created the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA). Bigger than Italy, it���s the largest conservation area on the continent. ReconAfrica���s licensed areas overlap with this huge international park.

The danger that the company could pursue hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in the Okavango looms large. ReconAfrica has not received a license to frack from the Namibian government, and earlier references to the possibility of using ���unconventional methods��� (i.e., fracking) have disappeared from their website. Company spokespeople insist that fracking is off the table. Yet a number of senior executives made their reputations by fracking, including CEO Scot Evans, formerly of oil multinational Halliburton. Drilling operations are headed up by none other than the geologist credited with developing the fracking method, Nick Steinsberger, described by an industry publication as ���one of the men who made the American shale boom happen.���

South African geologist Jan Arkert believes, however, that fracking will be required to extract the oil from the soil, and that harmful emissions will therefore be released into the atmosphere. Despite the dangers, company representatives joyfully declare the potential for 120 billion barrels of oil equivalent, numbers potentially ���laughable because they are so high.��� But it���s not only the exploratory glee that mimics the tone of colonial adventurers of over a century ago. ReconAfrica���s public relations spin comes with promises for the people of Namibia and Botswana, and supposed improvements in their way of life, including jobs. But, as with many extractive projects, the drilling is not labor intensive, so the project is not expected to lead to many new jobs; moreover, the skilled jobs on-site are held mainly by workers from Canada and the US. In fact, jobs for residents in the region have been mostly limited to short-term manual labor, and in some cases, workers have been fired after a brief stint and their pay withheld; according to activist Ina-Maria Shikongo of the organization Fridays for Future Windhoek, when the labor commissioner went to investigate, he himself was slapped with a lawsuit by the company. In fact, ReconAfrica has taken pains to emphasize their ostensible ���strong social license��� and eagerly talk up their efforts at community engagement through a series of public meetings in the region. But, as numerous accounts have described, their outreach was fraught with problems: public notices were only distributed in English���a language not spoken by a majority of the residents���and the sessions themselves, limited due to COVID-19-related restrictions, have included only a small number of people.

The company���s behavior has been so egregious that a lawsuit has been brought by the family of Andreas Sinonge in Mbambi, whose farm is located near the second borehole���one of over 600 working farms that lie within ReconAfrica���s exploration area, some of which are irrigated with water from the Okavango River. Intending to bring the company and several government ministries before the Namibian High Court, they argue that they never consented to the drilling and that ReconAfrica is squatting illegally.

Indigenous resistance and community organizingIn the face of this corporate aggression, the indigenous San people of the Okavango have mobilized and spoken out in protest. They argue that the area should be protected under commitments of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to the ���cultural landscape��� accompanying its designation as a World Heritage site. Further, they continue, the exploration violates the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the commitments to protect the environment enshrined in the Namibian constitution. As a result of protest against the violation of the site, ReconAfrica was compelled to accept an exemption for the Tsodilo Hills of the UNESCO-designated area���a small section of the exploration area, but a victory nonetheless.

Activists have been moving into action both locally and internationally. Fridays for Future Windhoek, Frack Free Namibia and Botswana, the Kavango Alive activist network, and Saving Okavango���s Unique Life (SOUL), among others, have grown their resistance over the past year through a series of marches on UNESCO offices, the parliament, and government ministries. In April 2021, Earth Day���and on the heels of US president Joe Biden���s Leaders��� Climate Summit���protesters in Namibia���s capital city, Windhoek, delivered letters to US and German ambassadors. The letter read, in part: ��� When President Biden said yesterday, ���We have to move. We have to move quickly to meet these challenges,��� surely this meant stopping even the slightest damage to one of the world���s most delicate and magnificent surviving eco-systems, especially in the name of dirty energy!

In the face of activists��� assertion of their right to say no, the regional governments have insisted, on the contrary, on their ���right to explore.��� Notwithstanding strong environmental protections in the Namibian constitution, and the fact that both Namibia and Botswana are parties to the Paris Agreement, aspirations for resource nationalism on the part of both have remained firm. In a joint state���corporation press release, Namibian minister of mines and energy, Thomas Alweendo, extolled the initial drilling results as a ���great period for the people of Namibia,��� hinting at hypocrisy in the idea that the global South should be denied any potential developmental extraction offers. Meanwhile, according to Ina-Maria Shikongo, activists critical of the government���s actions are branded as ���outsiders,��� and as hostile to the opportunities on offer for indigenous people. ReconAfrica, for their part, has welcomed the government as ���one of the friendliest regimes for explorers.���

Extraction in Africa and the ���net zero��� eraThe calls for net-zero emissions and curbs on fossil fuel exploitation have created contradictions where the world���s oil companies face urgent demands to transition to sustainable fuel sources, at the same time that oil is becoming profitable again. During the pandemic, prices crashed globally because of a glut in supply, even dipping into negative territory in the early stages of the crisis. Today, a new oil boom could be around the corner, with prices creeping upward. But even in the economic downturn of 2020, consumption still averaged 91 million barrels a day���more than the world consumed daily in 2012. The world���s largest banks have provided $3.8 trillion to fossil fuel companies since 2016, when the Paris Agreement took effect; global banks provided $750 billion in financing to coal, oil, and gas companies in 2020 alone. At the same time, costs for a ���sustainable transition��� are enormous, where energy investment will need to rise to $5 trillion a year by 2030 to achieve net zero, from $2 trillion today. These tensions exert contradictory pressures on the fossil fuel industry in a number of directions, the result of a wider capitalist economy inextricably tied to competition and profit: how to invest in new technologies while maintaining a way to profit through extractive industries.

Likewise, global powers claiming the mantle of ���net-zero��� aspirations are embarking on a new period of ���green imperialism.��� These are the dynamics of the ���sustainable transition,��� and activist forces and the left must understand this new terrain as one on which we are compelled to fight. ReconAfrica is on a no-holds-barred drive to extract profit for as long as that window of opportunity remains open. And because of mounting pressures on the industry, its tendency to cut regulatory corners, as reported by environmentalists and activists���no matter the cost to communities and wildlife���will only intensify. On the one hand, a small, ���junior��� oil company like ReconAfrica cannot go it alone: as the company itself has stated, they will need the bigger resources of an oil major to step in and pull off the exploration success they claim lies in the Okavango. Given these pressures, when National Geographic revealed, on May 21, the existence of a whistleblower Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) complaint against the company���citing more than 150 instances of false and misleading statements to investors���the news was shocking but not entirely surprising. In response, ReconAfrica hurriedly filed 22 amendments with Canadian securities regulators and lashed out at the magazine for running ���false��� statements and a ���hit piece.���

On the other hand, in the ���net-zero��� landscape, Big Oil needs ���wildcatters��� like ReconAfrica: small companies willing to take risks in ���unexplored��� territory, who can continue to deliver a return on investment in fossil fuels in less heavily regulated regions of the world. In this context, oil majors might be more compelled to sell off their assets to producers more willing to buck the pressures towards ���greening��� their enterprise. In late May 2021, an avalanche of change���from stockholder rebellions at Shell, Exxon, and Chevron to a groundbreaking court ruling in the Netherlands compelling Shell Oil to slash emissions by 45 percent by 2030 compared to 2019 levels���are only the latest developments for high-profile companies like BP and Shell who had already made ���net-zero��� commitments.

The fossil fuel industry is fighting for its future in Okavango and other extraction ���hot spots��� across the continent. Extraction continues under the guise of these ���new finds��� by companies, like ReconAfrica, who opt to violate regulations and human rights. With historically weaker regulatory enforcement, countries of the global South will be likely destinations for these ���last great discoveries.��� As Francois Engelbrecht of the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa explained to CNN, ���The big risk is that the global North makes the transition, and that Africa becomes the dumping ground for the world���s fossil fuel technologies���the last place where this kind of energy is being pursued.��� A 2020 study, for example, found that European oil exported to Nigeria exceeded EU pollution limits by as much as 204 times. Ina-Maria Shikongo describes the stakes well: It���s slavery on another level, it���s a continuation of colonialism. The transition has to be about saving lives, so everyone has a fair share. We have all of the raw materials but we live in poverty, but it���s an imposed poverty.

While Big Oil and governments of the global North advocate for market-based, ���net-zero��� so-called solutions to the crisis, frontline struggles underscore the actual stakes: the oil industry���super-majors and ���junior��� operators alike���will not leave the fossil fuel world stage quietly. Fortunately, the global resistance continues to grow, accelerated in no small part by struggles like the one in Okavango that is helping to reshape the terms of this fight beyond its borders. The coalitions knitted together to stop ReconAfrica in Namibia and Botswana both put the worst, most outrageous abuses on full display in Southern Africa and likewise provide strength and insights for the wider movement. As Ndaundika Shefeni of SOUL remarks, ���As opposition grows across the region and world, unlikely alliances are forming of spiritual leaders, cultural organizations, conservation charities and grassroots community groups.���

These are the forces that will most decisively stop extraction and avert a climate emergency, on terms to meet the needs and interests of ordinary people, including those currently in the crosshairs of profit-fueled extraction. This is the strategic vision embraced by activists across the continent and beyond, some fighting for decades, as they continue to challenge disastrous oil exploration, from Nigeria���s Niger delta region���the site of drilling for three-quarters of a century���to the new East African Crude Oil Pipeline planned to run through Uganda and Tanzania, home to world-famous wildlife preserves. As Nigerian environmental activist Nnimmo Bassey puts it, ���Now is the time for ReconAfrica to spare Okavango, [and] the people of Namibia and Africa, the avoidable harms which will result from their mindless pursuit of profit at the expense of the people and planet. Anything less will be nothing other than willful climate and ecological crimes.���

The global movement will not let them get away with it.

This was first published in a special ���Africa��� issue of the journal, New Politics. It is republished with kind permission of the editors.

September 28, 2021

Lagos street boys

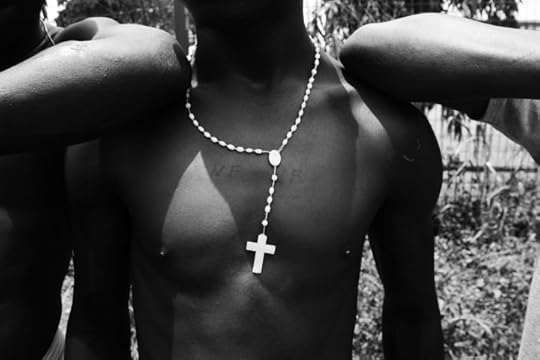

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. A Nigerian���s worst nightmare is an encounter with area boys, who are also known as��agbero. They are loosely organized gangs of street teenagers and adult males operating in the Southern Nigerian cities of Aba, Onitsha, Port Harcourt, Benin, Ibadan, and Lagos, where their notoriety is more renowned. They extort money from passers-by, traders, motorists and passengers, pick pockets, peddle drugs, and during elections become racketeering tools for fraudulent politicians in exchange for financial compensation. But what else do we know about area boys?

The term “area boy” was originally used to refer to anyone who identified with the street, locality or the area where he resides. These young men (and sometimes women) grouped themselves into a form of sociocultural organization who carried out duties to their communities that included acting as de facto security personnels and organizers of local parties and festivals.

That was in the 70s and early years of the 80s. The later years of the 80s came with repressive military leadership that not only disregarded education but instituted policies that brought about economic hardships that thrust many families into poverty. Parents could no longer send their children to school. Youth unemployment became rampant. Another consequence was that some of these young men who were in service to their communities morphed into terrorizing hoodlums. Today, they are maligned and stigmatized for their criminality.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje.Tolulope Itegboje���s poignant and heartfelt film��Awon Boyz, currently showing on Netflix, is a documentary concerned with the other side of the Lagos street boys. Without endorsing their nefarious activities, he presents them with an opportunity to share their stories. And what they offer is a balanced narrative about their lives, which allows us an understanding of who they are and why they are. I spoke with Itegboje about the film, the inspiration behind it, creating it, and the need to humanize the street boys of Lagos.

Dika OfomaArea boys especially those in Lagos are known to be a single thing���notorious. And not without reason; almost every Nigerian has either a theft or an extortion experience with them. Why did you think it important to humanize them by telling their stories?

Tolulope ItegbojeThat���s a pretty good question. You���re right when you say area boys are only known for their notoriety, especially as tools for violence. While aspects of this are true, it is still a single-sided narrative. And so the reason why it was important to humanize them was to challenge this and acknowledge their humanity in sharing their full story. Because disregarding that they are humans as we are means treating them as less than. Because if we act as though they have no sense of shared values, a shared experience with us, it now becomes a case of us against them. Or them against us. And to be honest, we are kind of the same. We have similar hopes and dreams. I don���t think anybody wakes up and decides they want to be an area boy. A lot of us in privileged positions need to realize that but for fate and circumstances, we could be in a similar situation.

Dika OfomaTrue. I was struck by how willing they were to share the minutest detail about their lives. I also appreciate that there wasn’t a voice-over narrating their lives and telling us who they were. Whatever conclusion we arrive at about area boys was gleaned from hearing them share their stories. Was it a conscious decision?

Tolulope ItegbojeYeah. Absolutely. And you know, this project is special for me because it is one of the few times as a filmmaker I went in with one intention and I was able to achieve exactly that intention. I think I should give a background to making this documentary. So I worked as an advertising agency producer for six years. My job entailed producing TV commercials and obviously, in the course of the work we had to interact with area boys. I had this music video shoot in Ajah once, and we hired the police and security and didn���t expect area boys to show up but they did. And to our surprise, the police officers didn���t do anything. In fact, they were the ones who asked us to pay the area boys off. And so from then, every shoot I���ve done that involves an exterior scene, there is a part of me that is prepared to sort out area boys. So in the course of seeing them and interacting with them, I just realized that I had to make something about them. Initially, I wanted to make a musical short film about area boys and present them as these cool guys who don���t answer to anyone. But then it evolved because I realized that would be incomplete without some story and I didn���t know the story so I started researching area boys and how they ended up and the one thing that struck me was what you mentioned about there just being a single narrative about them.

The more research I did, I also realized that there was no real example of a case where area boys had been allowed to tell their stories. The media���s reportage was concerned with that one narrative. At some point when making the film, I thought of including interviews with everyday people sharing their experiences with area boys. In which case, an area boy shares his story, then you cut to someone talking about how area boys robbed them. In a sense, it almost feels like you are passing judgement. And so we decided on just letting the area boys share their stories. And this doesn���t mean that in humanizing them we were endorsing everything they do. It was also important that in telling this story we needed them to confront and take responsibility for the violence they cause. That is why there is a whole segment where we are having a conversation with these guys about violence and if they recognize how destructive it is sometimes.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma Yeah. I think it’s well thought out. You didn’t pass judgment in telling their stories, and neither did they try to absolve themselves of their misdeeds. I think I liked that they owned up to it and merely were interested in telling us how they became who they are.

Tolulope ItegbojeI think that was something that struck us: how incredibly self-aware these guys are.

Dika OfomaI think something we learn from��Awon Boyz��is that these street boys are different, their individual stories differ; what unites them is the social deprivation they’ve all experienced. I’m curious to know whose story you found the most fascinating and why?

Tolulope ItegbojeIt���s a little tough for me, to be honest, to say that anyone, in particular, stands out. I found all of them equally fascinating. If you dig through there are insights and lessons into all their stories.

Dika OfomaAll right. For me, it was Volume who had come to Lagos to pursue his music dreams, loses all his valuables in one night, and had to become a street pimp to survive. His crushed dream almost brought me to tears. I was reminded of how uncertain life is.

Tolulope ItegbojeThat���s interesting. I like how he sees the street as pivotal to his story, but still has the awareness to say that he doesn���t want it for his kids.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma What was the writing/creative process like?

Tolulope ItegbojeInteresting. I spent about a year researching the topic, which in hindsight was an insane amount of time. But it did produce some interesting insights into how I approached the conversations with the guys. We shot the interviews, which ended up being long, and then transcribed those interviews. I worked closely with a wonderful script editor named Omotayo Adeola to craft a script/edit guide for the editors. But I find that the story as we have it now didn’t come together until the editing started. We essentially began this harrowing process of moving stuff around���taking stuff out, adding new stuff for greater emotional context, shooting new footage to contextualize what the guys were saying; exploring the relationship between particular visual and narrative pieces to tell the best story possible. That whole process essentially took about a year to complete and if I had hair, I would have been pulling it out every second of the way till we got to the end when it all came together beautifully.

Dika OfomaSo I’m wondering, have the cast of Awon Boyz seen the documentary yet? What did they think of it?

Tolulope ItegbojeThey have seen it twice. They saw it at a screening at iREP Film Festival, which is held in Lagos every year. I think it was important to us that they saw it at that screening as well. Although, it was a bit of a leap of faith because it was the first time that anybody outside of the internal core team was going to see the documentary and so we didn���t know how anybody would react to it. But it was amazing because we had people in the audience that were crying. The response was overwhelming. Just seeing all those people connect to their stories and be so welcoming and embracing of them in this setting was a lot for them to see. Even my parents were at that screening. Following that, my dad had this group of businessmen in his church invite them over to see the documentary again. It was really special for them because it achieved our purpose for the documentary when we spoke to them the first time. We wanted people to see them in a different light. For them, that was sort of a mission fulfilled and a dream come true.

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma

Image credit Tolulope Itegboje. Dika Ofoma We now have a balanced story about area boys. We have come to see them as multidimensional, not just as a menace to society. Yes, they extort money from motorists but they are also loving fathers and wonderful friends. There’s an element of social activism in ensuring and telling this complete story. But I’m wondering if your activism extends beyond this. Do you have plans to further the conversation around area boys and in helping to alleviate their situation? Do you feel a sense of responsibility?

Tolulope ItegbojeYeah. We do feel a sense of responsibility. I thought I was only going to spend a year working on this film but here we are three years after we shot, and I’m still talking about it. I’m in constant conversations with the guys about ways to support them beyond monetary help, which, of course, is an aspect that we cannot ignore as you rightly pointed out. So, one of the things that we did was to set aside a portion of the revenues from the film and give it to each of the guys. We are also putting them in touch with people who have reached out to say they want to help. And the guys know that they can call me to support them in whatever way I can personally.

But like I said, the conversation goes beyond that. I believe we all have a responsibility to these guys. We all have a role to play. It is not enough to say it’s the government’s responsibility. The government can’t do it alone. Private organizations have a role to play, individuals have a role to play, nonprofit organizations have a role to play. When #EndSars happened, we were the ones who felt the heat from the criminal elements in the aftermath. And so we have to take it seriously. And I believe that the single most important thing I could have done as a filmmaker was to use my voice and skills to call attention to this and create room to have the conversation about why it is important to understand these guys, so we can better interact and co-exist with them. Beyond money, it is that and asking how do we create equal opportunities for them. How do we stop their continued marginalization and disenfranchisement? How do we move them from the fringes of society and reintegrate them?

September 22, 2021

A just recovery from COVID-19

Photo by Houcine Ncib on Unsplash

Photo by Houcine Ncib on Unsplash Food systems are often a point of focus and expression for crises and popular resistance in North Africa. When subsidies are lifted and the prices of essential foods spike, social uprisings follow���and they are nearly always severely suppressed.

Uprisings followed the International Monetary Fund���s (IMF) interventions after the debt crisis in the 1970s and 1980s. Policies from that era endured into the 21st century, with agro-food systems across the region geared towards the expansion of large-scale, commercial agriculture, attracting foreign investment and big agribusiness, export-orientation, and a reliance on imports for domestic food needs and production inputs. This came at the expense of broad-based rural development and traditional food systems and cultures. The result has been the impoverishment of rural populations and mass migration to urban areas and abroad.

A new study by the Transnational Institute (TNI) and the North African Food Sovereignty Network (NAFSN) shows how traditional farming and local food production deteriorated and how food dependency intensified with communities increasingly reliant on imports from the Global North. The takeover of land, water, and seeds by domestic and foreign capital continued.

Uprisings followed the 2007-2008 global food price crisis too. And, more recently, food systems were one of the main catalysts for the uprisings in Tunisia in December 2010 that would spread across the North African and the Arab region forming part of the ���Arab Spring.��� But still, states in the region did not change direction despite popular pressure from below.

Decades of neoliberal state policies have led to considerable food dependency. More than 50% of calories consumed daily in the Arab region are from imported food, with the region spending around $110 billion annually on food imports. As argued in the TNI-NAFSN study, this food dependency is a result of market-based policies dictated by global financial institutions (the IMF, World Bank, and WTO), reinforced by UN organizations (FAO, UNDP, ESCWA), and translated into guiding policy frameworks by regional organisations (Arab Organisation for Agricultural Development/the Arab League). National regimes, in turn, followed these prescriptions to a tee.

This has brought prosperity to a few but left many others facing considerable hardship as markets, resources, and policies are increasingly dominated by a handful of powerful (corporate) actors. A downward swing in oil prices has added to the challenge leaving oil-producing countries, such as Algeria and Libya, struggling to cover the costs of food imports.

The COVID-19-related lockdowns in the region led to hundreds of thousands of layoffs, diminishing households��� purchasing power and disrupting their ability to access food. According to the World Bank (October 2020), unemployment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region hit a record high during the pandemic and caused widespread impoverishment. The economic dislocation wrought by the pandemic has led to a surge in the number of people suffering from hunger and malnutrition in a region in which, even prior to COVIDd-19, a significant share of the population experienced food insecurity.

According to the TNI-NAFSN study, small-scale food producers have been among the hardest hit by the closure of food markets (as in Morocco or Tunisia), declining sales of food and agricultural products, and difficulty accessing key production inputs.

Women have been particularly affected by the pandemic due to the roles they play in productive and reproductive work. Especially in rural areas, they play a key role in obtaining food for their households, exposing them to the risk of infection during their farming, laboring and other work. For example, in Lalla Mimouna in the K��nitra region of Morocco���a pandemic hotspot by June 2020���hundreds of women agricultural strawberry workers became infected while working on farms owned by a Spanish investor producing fruit for export. While being paid starkly low wages, carrying out exhausting physical work and facing clear disparities in terms of access to income, economic opportunities, social protection and health care, women agricultural workers have, in many ways, borne the brunt of the crisis.

Governments and institutional actors across the region have responded to the health and economic crisis in a number of ways, including intervening more assertively in the trade of key foodstuffs and medical items, and extending emergency aid to various sections of society. However, these measures did not address the root causes of the crisis.

International and regional institutions recommended more or less the same policies as before, with minor adjustments to mitigate negative effects, rather than transforming food systems for social justice and sustainability. Essentially, they recommended perpetuating dependency on global agro-food markets and private capital as key mechanisms to deliver food security in the region.

This business-as-usual approach continues to tie people���s food supply to the market mechanisms that prioritize profit for private corporations and the delivery of hard currency to cover state���s debt obligations.

The North African region could be an area for cooperation and solidarity among its peoples. But this will not be brought about by states and local elites that profit from the continuation and expansion of the current agro-food model, with its ���free����� trade and liberalization of local markets dramatically undercutting small-scale producers.

As we argued in the TNI-NAFSN study, the severity of the crisis requires a change of direction���one that is geared towards the rights and agency of laborers and small-scale producers, agro-ecology, and the complete elimination of the structural causes of food dependency and the lack of food sovereignty. By politicizing food systems and putting issues around democratic control at the heart of decision-making, food sovereignty thus offers a radically different pathway out of the current crisis.

Read the whole study here.

The long term prospects for women���s liberation in Egypt

Image credit Women on Walls photo project via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Women on Walls photo project via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. In mid-August of this year, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi ratified amendments to the country���s sexual harassment law, increasing the maximum penalty for those engaging in online (or other electronic) harassment to imprisonment for two to four years. This was a notable improvement from the meager punishment of six months and 3000 Egyptian pounds (approximately 180 USD) that had previously been in place. After a year of highs and lows, these changes have been met with cautious optimism by women���s rights groups in the country.

In Egypt, like elsewhere in the world, progress on the status of women has had its ups and downs. In the last year or so, with a veritable tidal wave of cases and claims of sexual harassment, assault, and violence���and mixed results in terms of justice���many have expressed feeling pushed and pulled by waves of optimism, confusion, vindication, and despair. Indeed, it is hard to assess the degree of progress (or regression) given the constant barrage of stories, both promising and demoralizing, relating to the status of women. Alongside the high-profile stories that galvanized the country���s #MeToo moment, several less-publicized instances of social discourse and legal changes have emerged that may be hugely influential on the long-term prospects for women in the country.

It has been more than ten years since the 2011 uprising that ousted former President Hosni Mubarak. His deeply entrenched authoritarian leadership had lost its momentum many moons prior, characterized in large part by corruption, heightened levels of inequality, and crumbling infrastructure. Since January, the 10th anniversary of the uprising, many voices have explored the outcomes of the uprising and the events in the years that followed: the election of Mohammed Morsi in 2013, his quick spiral from leader to persona non grata, the massive protests that led to his removal, and the rise of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi. Alongside this general discourse lies the question of both the role and treatment of women in Egyptian society; a question galvanized by a movement that emerged last year, sparked by high-profile cases of sexual assault, violence, intimidation, and harassment.

Despite, or perhaps in part because of, the re-energized women���s movement, the new year came with some unwelcome regression for the cause. In February 2021, a draft personal status law significantly curtailing the rights of women was introduced by the Egyptian cabinet. The proposed bill was quickly withdrawn after significant backlash. Still, the fact that the law was even put forward is deeply concerning. Among other archaic and profoundly patriarchal elements, the law would have required women to obtain permission from a male relative to travel, make women unable to sign their own marriage contracts, and significantly reduce the rights of mothers in decisions of custody and child-rearing.

While several high-level positions are held by women in the country, including a number of influential ministerial posts, insufficient female representation within the country���s legal system is likely part of the reason for stagnation and the risk of regressive policies.

Women make up only 0.3% of the judges in the country. In June, for the first time, the Supreme Council of Judicial Bodies approved the appointment of women to high-level positions within the Administrative Judiciary and the Public Prosecution Authority. Before this, women had only been appointed to these positions under ���exceptional��� circumstances. Indeed, in 2010, despite international pressure and a push by the Mubarak regime���which had appointed several women judges���the Administrative Judiciary voted 334 to 42 against the appointment of women judges. While things theoretically improved following the 2011 revolution, with nondiscrimination enshrined into the 2014 constitution, a culture of exclusion has continued, with women thus far only being appointed by presidential decree.

While the cases that jumpstarted the most recent movement were not clearly related to a broader social movement, this linkage has existed at several key points of the country���s modern feminist history. To understand where the women���s movement now stands, it is critical to examine the successes and failures of these pivotal historical events.

The contemporary women���s movement in Egypt has its origins in the 1800s with the development of the modern state under the rulership of Muhammad Ali. The British occupation had unified the country under a nationalist cause which encompassed many groups, including those espousing nationalist and feminist ideals.

By the end of the century, women���s literacy rates among the middle and upper classes had increased substantially, which ultimately led to the establishment of a women���s literary culture and press. In 1892, Al-Fat��h (The Young Woman)���the first entirely feminist publication, written by women for women���was founded by Hind Nawfal, a Syrian Christian author. ���Despite the wide variety of literary and scientific journals available at the time, Nawfal said she had set up Al-Fat��h because none of those publications dealt specifically with the rights of women, nor articulated their problems in a satisfactory manner,��� writes Nabila Ramdani in the Journal of International Women���s Studies.

As the nationalist movement against British occupation gathered steam approaching the 1919 revolution, the feminist movement found a home within the nationalist cause. In turn, calls for women���s education were backed up by arguments for the betterment of Egyptian society as a whole. Similar narratives can still be found in arguments for increased focus on the rights and wellbeing of Egyptian women, such as in the National Strategy for the Empowerment of Egyptian Women, part of the country���s long-term national agenda, ���Egypt Vision 2030.���

���Without the true empowerment of women, in a manner that allows for their self-fulfillment, freeing and supporting their abilities, their smooth and safe participation,��� the strategy���s introduction states, ���no development efforts will be successful nor will intended objectives be achieved.��� However, the nationalism of today does not have an occupying force to foster unification.

The 1919 revolution was perhaps the clearest example of collaboration between the feminist and nationalist movements. Egyptian feminist icon Huda Shaarawi, who led female protests against the British, collaborated closely with revolutionary-turned-statesman Saad Zaghlul, leader of the Wafd Party and later prime minister.

It is often noted that a defining characteristic of the feminist movement that developed around the 1919 revolution against the British was that it included women from all socioeconomic backgrounds. However, Ramdani also points out that while the efforts of those with fewer means have received little attention when compared to their wealthier counterparts, their sacrifices were often much greater. Similarly, those working to incite change today largely come from the wealthier class, while many have complained of disproportionate punishments doled out to women who are less economically advantaged and are therefore seen as acting against public morals.

On a personal level, it becomes complicated to reconcile anecdotal evidence of fierce female empowerment on the one hand, and systematic misogyny and underrepresentation�� on the other. Ultimately, what appears most clearly when examining these changes���both historical and contemporary���is a complex picture, which can perhaps never be wholly accurately represented, especially by the media.

The long terms prospects for women���s liberation in Egypt

Image credit Women on Walls photo project via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Women on Walls photo project via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. In mid-August of this year, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi ratified amendments to the country���s sexual harassment law, increasing the maximum penalty for those engaging in online (or other electronic) harassment to imprisonment for two to four years. This was a notable improvement from the meager punishment of six months and 3000 Egyptian pounds (approximately 180 USD) that had previously been in place. After a year of highs and lows, these changes have been met with cautious optimism by women���s rights groups in the country.

In Egypt, like elsewhere in the world, progress on the status of women has had its ups and downs. In the last year or so, with a veritable tidal wave of cases and claims of sexual harassment, assault, and violence���and mixed results in terms of justice���many have expressed feeling pushed and pulled by waves of optimism, confusion, vindication, and despair. Indeed, it is hard to assess the degree of progress (or regression) given the constant barrage of stories, both promising and demoralizing, relating to the status of women. Alongside the high-profile stories that galvanized the country���s #MeToo moment, several less-publicized instances of social discourse and legal changes have emerged that may be hugely influential on the long-term prospects for women in the country.

It has been more than ten years since the 2011 uprising that ousted former President Hosni Mubarak. His deeply entrenched authoritarian leadership had lost its momentum many moons prior, characterized in large part by corruption, heightened levels of inequality, and crumbling infrastructure. Since January, the 10th anniversary of the uprising, many voices have explored the outcomes of the uprising and the events in the years that followed: the election of Mohammed Morsi in 2013, his quick spiral from leader to persona non grata, the massive protests that led to his removal, and the rise of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi. Alongside this general discourse lies the question of both the role and treatment of women in Egyptian society; a question galvanized by a movement that emerged last year, sparked by high-profile cases of sexual assault, violence, intimidation, and harassment.

Despite, or perhaps in part because of, the re-energized women���s movement, the new year came with some unwelcome regression for the cause. In February 2021, a draft personal status law significantly curtailing the rights of women was introduced by the Egyptian cabinet. The proposed bill was quickly withdrawn after significant backlash. Still, the fact that the law was even put forward is deeply concerning. Among other archaic and profoundly patriarchal elements, the law would have required women to obtain permission from a male relative to travel, make women unable to sign their own marriage contracts, and significantly reduce the rights of mothers in decisions of custody and child-rearing.

While several high-level positions are held by women in the country, including a number of influential ministerial posts, insufficient female representation within the country���s legal system is likely part of the reason for stagnation and the risk of regressive policies.

Women make up only 0.3% of the judges in the country. In June, for the first time, the Supreme Council of Judicial Bodies approved the appointment of women to high-level positions within the Administrative Judiciary and the Public Prosecution Authority. Before this, women had only been appointed to these positions under ���exceptional��� circumstances. Indeed, in 2010, despite international pressure and a push by the Mubarak regime���which had appointed several women judges���the Administrative Judiciary voted 334 to 42 against the appointment of women judges. While things theoretically improved following the 2011 revolution, with nondiscrimination enshrined into the 2014 constitution, a culture of exclusion has continued, with women thus far only being appointed by presidential decree.

While the cases that jumpstarted the most recent movement were not clearly related to a broader social movement, this linkage has existed at several key points of the country���s modern feminist history. To understand where the women���s movement now stands, it is critical to examine the successes and failures of these pivotal historical events.

The contemporary women���s movement in Egypt has its origins in the 1800s with the development of the modern state under the rulership of Muhammad Ali. The British occupation had unified the country under a nationalist cause which encompassed many groups, including those espousing nationalist and feminist ideals.

By the end of the century, women���s literacy rates among the middle and upper classes had increased substantially, which ultimately led to the establishment of a women���s literary culture and press. In 1892, Al-Fat��h (The Young Woman)���the first entirely feminist publication, written by women for women���was founded by Hind Nawfal, a Syrian Christian author. ���Despite the wide variety of literary and scientific journals available at the time, Nawfal said she had set up Al-Fat��h because none of those publications dealt specifically with the rights of women, nor articulated their problems in a satisfactory manner,��� writes Nabila Ramdani in the Journal of International Women���s Studies.

As the nationalist movement against British occupation gathered steam approaching the 1919 revolution, the feminist movement found a home within the nationalist cause. In turn, calls for women���s education were backed up by arguments for the betterment of Egyptian society as a whole. Similar narratives can still be found in arguments for increased focus on the rights and wellbeing of Egyptian women, such as in the National Strategy for the Empowerment of Egyptian Women, part of the country���s long-term national agenda, ���Egypt Vision 2030.���

���Without the true empowerment of women, in a manner that allows for their self-fulfillment, freeing and supporting their abilities, their smooth and safe participation,��� the strategy���s introduction states, ���no development efforts will be successful nor will intended objectives be achieved.��� However, the nationalism of today does not have an occupying force to foster unification.

The 1919 revolution was perhaps the clearest example of collaboration between the feminist and nationalist movements. Egyptian feminist icon Huda Shaarawi, who led female protests against the British, collaborated closely with revolutionary-turned-statesman Saad Zaghlul, leader of the Wafd Party and later prime minister.

It is often noted that a defining characteristic of the feminist movement that developed around the 1919 revolution against the British was that it included women from all socioeconomic backgrounds. However, Ramdani also points out that while the efforts of those with fewer means have received little attention when compared to their wealthier counterparts, their sacrifices were often much greater. Similarly, those working to incite change today largely come from the wealthier class, while many have complained of disproportionate punishments doled out to women who are less economically advantaged and are therefore seen as acting against public morals.

On a personal level, it becomes complicated to reconcile anecdotal evidence of fierce female empowerment on the one hand, and systematic misogyny and underrepresentation�� on the other. Ultimately, what appears most clearly when examining these changes���both historical and contemporary���is a complex picture, which can perhaps never be wholly accurately represented, especially by the media.

September 21, 2021

After Bouteflika

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres.

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres. Every Saturday in Washington, DC���s Dupont Circle at around 2:30 PM, Hamid Lellou, 54, can be found in the northwest corner of the park carefully placing dozens of Algerian flags and banners in the ground.

Once his setup is complete and he is surrounded by the colors of Algeria and slogans like ���You are not alone��� and ���They all must go,��� Lellou positions a tripod, clips in his cell phone, and begins broadcasting live around the world on Facebook.

More than 4,000 miles from the Algerian capital, Lellou and the handful of men and women who join him represent a transformational protest movement, the Hirak as it is called, that took hold across the North African nation and throughout its diaspora starting in early 2019.

The Hirak���a term derived from the Arabic word for movement���began in February of 2019 as weekly street demonstrations protesting the announcement that Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the country���s then 81-year-old president, largely incapacitated after a series of strokes, would stand for a fifth term. The Hirak quickly gained momentum across the country, bringing��out millions from all walks of life via peaceful marches.

In the months prior to leaving Algeria for the US in the fall of 2019, Malik, a New York City-based activist who preferred not to give his last name, took part in massive Hirak demonstrations in the coastal city of B��ja��a, not far from his hometown. When asked to describe the power and emotion of those moments, marching the streets alongside hundreds of thousands of fellow Algerians, he pauses and answers softly: ���We had tears in our eyes.���

Speaking of the octogenarian leader who served as president from April 27, 1999 to April 2, 2019, and passed away on Friday, September 17th,�� he adds: ���He just hated the people.���

But the movement���s grievances were much broader than the removal of a sick and corrupt leader. Bouteflika represented decades of state repression, inequality,��economic stagnation, graft, and political inertia. Since its independence from France in 1962, Algeria has been largely ruled by the same regime���le pouvoir as it is called���an unelected military and business elite who wield the levers of power behind the scenes, despite the veil of elections and democracy.

Brahim Rouabah, an Algerian-born political��scientist at Brooklyn College (City University of New York) who regularly attends Hirak protests in New York, paints the picture of a nation marked by acute ���pauperization and unemployment,��� despite vast natural resources and human capital, and a state more intent on serving foreign interests than addressing the dire health, education, and infrastructure needs of its people. He refers to the ���organized abandonment of the people by the military oligarchy that controls the economy, that dominates political life and denies the people genuine self-determination.��� The Algerian population, he says, ���feel like they live under colonialism with an indigenous face.���

As a mass movement calling for civilian rule, the leaderless Hirak cuts across class, ethnicity, gender, age, and religious observance. Rouabah explains this diversity noting ironically how injustice is the only fact of life that is ���fairly distributed��� in Algeria.

The Hirak also extends across a large diaspora around the world, approximately seven million according to the National Institute of Demographic Studies, a French public research��organization��specializing in population��studies. These activists living abroad do not view themselves as separate and apart from their compatriots living within Algeria���s borders and their actions echo those of their countrymen and women back home.

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres.

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres.In her paper, ���The role of Hirak abroad: a renaissance for the Algerian Diaspora?,��� Algerian academic Hayette Rouibah writes about the impact the Hirak has on Algerians living abroad, bringing them ���closer to the everyday affairs of their home country��� and ���allowing them to be part the change taking place in their country.��� The diaspora, she writes, ���has become an important factor in the Hirak movement.��� She contrasts the current moment with earlier periods of disconnect between Algerians of the ���interior��� and ���exterior.��� Hayette adds: ���Since the start of the Hirak, we���ve noticed an unprecedented mobilization of the Algerian diaspora, via networks, associations and virtual communities on social media.���

While the largest demonstrations outside Algeria take place in France and Canada, small yet vociferous Hirak communities in the US have formed.

For Hamid Lellou, originally from Oran and a resident of Northern Virginia since��2006, the Hirak has been transformative. In many ways, it helped re-orient his time, his energy, and his passion.

���When I saw Hirak, I jumped in. For me it was something natural,��� he says. ���I���m a dual citizen, I have no problem with that. But I am deeply Algerian, and I am proud to help Algerian people. This is what keeps me going.���

Lellou, a mediator and conflict resolution specialist by training and experience, began his Hirak in early 2019 by standing in front of the Algerian Embassy in Washington, DC every week with other protesters voicing their anger with the regime��and calling for civilian rule.��After the start of the pandemic and with the permission of DC officials, Lellou moved to a park near the US Capitol where he began bringing��flags with him, one for every Algerian wilaya or province. Shortly after the January 6 insurrection this year on Capitol Hill, these small demonstrations found their permanent home in Dupont Circle, in the heart of Washington, where Lellou is joined by five to 12 activists every Saturday.

Expatriates like Ahmed (who preferred not to give his last name) meet up with Lellou regularly. Despite having lived all over the world since leaving Algeria as a child, Ahmed remains deeply connected to his country, traveling back nearly every year. In the fall of 2019, he made the trip specifically to see the Hirak protests for himself, an experience he describes as ���awe inspiring.���

The Washington, DC Hirak also mobilizes online, sharing videos from Algeria, sharing videos from DC, debating next steps, posting memes, highlighting government abuses, and simply making statements of solidarity and support. Lellou manages several different social media networks, broadcasting live twice a week: once from his home in Virginia and once from Dupont Circle. His audience varies from hundreds to tens of thousands per video. His goal is to facilitate a conversation about the Hirak, to discuss the implications of current events and to envision what a future Algerian state could look like.

A lot has happened in Algeria since February 2019, though in some respects, very little has changed. Weekly street marches turned into twice weekly demonstrations. In April 2019, President Bouteflika was forced to step down, and a new leader was put in place by the military regime. Elections were held���presidential, a constitutional referendum and a legislative vote���though on terms dictated by the ruling powers. The legitimacy of these and other ���cosmetic��� reforms have been discredited by feeble voter turnout and the tenacity of the Hirak.

The COVID-19 health crisis represented a major challenge and forced the movement to pause or at least take a different form for a while. Activists decided to halt in-person demonstrations due to public health concerns and for nearly a year, the streets were quiet. During this time, the state cracked down harder on descent. Journalists, activists, and social media users were arrested on trumped up charges, arbitrarily detained and even kidnapped and tortured.

A big question for the Hirak, a movement where street demonstrations represented so much, was what it would look like on the other side of the pandemic. Ultimately, online activism picked up and this helped prime the physical and digital terrain for the full return to in-person demonstrations that occurred starting in February of 2021.

Since this spring, the government has taken a more heavy-handed approach to the weekly marches. In May, they began banning protests in many cities outright, while continuing to weaponize the judiciary to mute the peaceful protestors, all under the approval and watchful eye of a supposedly new and reformed government. According to the CNLD, an Algerian citizen rights and watchdog group, approximately 200 individuals are imprisoned today for crimes ostensibly linked to the Hirak.

On why the government has taken the step to forbid marches and silence peaceful protestors, Rouabah, the Algerian political scientist, explains: ���They are, more and more, realizing that this is not going away. This is not a party or a festival. This is a popular revolution to remove them from power. The more they realize that, the more berserk they go: arrests, kidnap, torture���a��judiciary weaponized to abort this revolution. But the more they do this, the more people lose faith in their reformability and become even more convinced of the necessity of uprooting them.���

In the context of the movement in the USs, Algerians in New York, San Francisco and Washington, DC have maintained an in-person and digital presence supporting a Hirak network around the globe.

���You cannot believe how many Algerians I know now, from all over the world,��� says Lelloua. Highlighting the freer space in the US to communicate and organize, he adds: ���and we can do it because there are no security forces coming for us.���

On a warm afternoon this past June, protest chants echo down a quiet street in midtown Manhattan where a small group of Hirak protesters gather in front of the Algerian consulate.

Farida��Bouattoura, who left Algeria 27 years ago when she was a young girl, is��among those��present. She traveled more than an hour from her Long Island home to take part in the weekly rally, bringing with her signs documenting human rights abuses by the��state.

Bouattoura is new to activism. When the Hirak began more than two-and-a-half years ago, she��followed events from afar but did not take an active role. Everything changed for this 36-year-old teacher in April of this year after learning that her two first cousins were detained and imprisoned��in Algeria. Since then,��Bouattoura��has become a fervent participant in the Hirak.

���I remember how beautiful the gardens were there,��� she says, sharing memories of her early childhood growing up in the Algerian capital. She adds: ���It���s hard to explain, there is something about the sun there���The ray of light, it���s like perpetual peace.���

But there were dark memories as well, of an undeclared war marked by state violence and terrorism. What��Bouattoura��refers to as the ���black decade��� lasted from 1991 to 2002 and deeply scarred this nation of 44 million. She recalls a bomb exploding at the airport where her father worked when she was nine: ���We didn���t know what terminal, and I remember waiting at the gate in anticipation���As a child you know how much your life will be impacted if you lost your father. It was such a great moment when I saw him.���

The family ultimately emigrated to New York in 1994 where they found a permanent home.�����We were very fortunate,��� says Bouattoura. ���My parents knew how and what to do to leave.���

Despite the challenges of starting over, alone, in an anglophone country where they did not speak the language, the family rebuilt their lives in Queens and then Long Island, occasionally traveling back to Algeria to visit family. The last time was in 2016 for a wedding. But Bouattoura never found the same country of her early childhood memories, prior to the war. ���To be honest, when I go back, I���m quite disappointed. I want to go back to the way it was,��� she says with regret.

In early 2021, news of her cousins��� arrests in Algeria represented a shock for her, one that brought her much closer to the country she left as a child. These were the boys she played with when they were young kids and the sons of her beloved aunt.

On April 5, 2021, Ahmed Tarek Debaghi, 25, an active participant in the peaceful demonstrations since early 2019, was detained with friends��for posts they had shared on social media. A few weeks later, his older brother Ismail was arrested, according to Bouattoura, after walking down a street of Algiers holding a photo of his detained brother.

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres.

Image courtesy Michael de Vulpillieres.There is much uncertainty around their cases and the Debaghi��brothers remain detained to this day, with limited contact with the outside world. Initially, Bouattoura���s activism was about her family but soon their imprisonment came to represent much more to her. This is what drove Farida to the Hirak.

���I felt morally obligated [to help]���The protests have been peaceful. Even to this day there has only been brutality from the state,��� she says with a quiet Queens accent. ���They act in a fascist way. They use intimidation. The Algerian public understands that they have to stand up to it. It cannot be allowed.���