Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 117

October 7, 2021

But, first we’ll take this W

Abdulrazak Gurnah at the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest, via Flickr CC).

Abdulrazak Gurnah at the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest, via Flickr CC). The feeling was stronger than previous years, and it did seem like the Swedes were gazing towards Africa. One of the most infuriating things about the Nobel Literature prize committee is how hard they try to be cool and to surprise everybody, and to make sure never to pick anyone who���s on the betting rosters. That’s why I was certain that the Nobel Prize in Literature would not go to perennial Ladbroke favorites, Kenya���s Ngugi wa Thiong���o or Somalia���s Nuruddin Farah. I was ready for something outrageous like the prize going to Chimamanda Adichie (you never know though, they may give her the Peace one). I was frankly ecstatic that this year���s choice was Abdulrazak Gurnah, whose novels come to us by way of the sea, from the Swahili coast of Zanzibar.��

Abdulrazak Gurnah is the sixth African writer to have won the Nobel Prize in literature.��

The others�� are Wole Soyinka (1986), Naguib Mahfouz (1988), Nadine Gordimer (1991), JM Coetzee (2003) and Doris Lessing (2001). Indeed, he is also only the third Black writer to have won the prize. Unlike the Booker Prize which has historically scored well on the diversity points, the Nobel has always favored the whitest and the most European of all literature.��

That said, the Nobel had its heyday of diversity too. There appears to be a tidy alignment between the ascendancy of multiculturalism movements in Europe and recipients of the literature prize. The short spell of the canon wars during the late 80s and 90s, and the furious debates about what is canonical and classical seemed to have directly shaped the way the Nobel���s literature experts thought about the prize. Soyinka, Mahfouz, Gordimer, Derek Walcott, Toni Morrison and Kenzabur�� ��e won almost in succession from the years 1986 to 1994. For a brief eight years, the LitNobel was diverse, political, progressive and completely with-it.��

What followed was not so bad either. After a short spell of mostly Europeans, the LitNobel crew took a truly international journey from the years 2000-2012. Gao Xingjian from China, V.S Naipau from Trinidad, Orhan Pamuk from Turkey and amazingly two African writers, albeit white: South African J.M Coetzee and Zimbabwean Doris Lessing. A side note here: that it was not one but two South Africans (Coetzee and Gordimer) that won this prize, is somewhat astounding. The LitNobel is a pretty committed one-country-of-color only kind of institution. South Africa and China are the only two countries from the Global South to have scored this lottery twice. The LitNobel is essentially enamored by French literature (17 winners) followed by US literature (13 winners) and then British literature (11 winners). Even though it is tempting to think of African countries performing poorly here, it is the vast body of literature from the Middle East and South and Central America that appears to be least rewarded by the Swedes.��

Gurnah���s win pushes us to think about the role of the LitNobel and prizes, more generally, and the way in which they construct what we think of, read, engage with and buy as African literature today. In the end, it’s not too different from the way scholars, critics, academics do it. Lily Saint and my African literature survey is a good case in point. English language writing is privileged, it’s always about the novel, South Africa and Nigeria dominate. And the place of Egypt, North Africa and writing in Arabic always presents a crisis of categorization.

I remain ecstatic about Gurnah���s win but the elephant in the room here is the snub to the giant of African letters, Ng��g�� wa Thiong’o. I would go as far as to say that Gurnah would even agree with me that Ng��g�� more than deserves this prize. Suddenly, East Africa has been put on a pedestal and will come to be constituted into the Western prize circuits. But alas, it has been emptied of its most important, decisively pioneering writer as well as an influential critic and academic: Ng��g��. It is a bit surreal but the fact that Gurnah who writes in English was picked over Ng��g��, the vocal native-languages advocate also sends a message about the primacy of English language domination in African literature. Undoubtedly, Kenya and Tanzania are vibrant centers of Swahili language, culture, education, literature and Swahili operates alongside several other languages in these countries. Gurnah choose to write in English, perhaps partially because he fled to the UK at a really young age. But Zanzibar and Tanzania are places which have birthed legends of Swahili literature such as Haji Gora Haji, Euphrase Kezilahabi and Shabaan bin Robert.��

The LitNobel chose to highlight this incredibly linguistically rich region but sidestepped the very man who gave us the ���decolonize your mind��� mantra entirely premised upon the loss of native languages and who has fought for the psychic, spiritual and core importance of cherishing mother tongues that were snatched by colonialism. This decision does not simply make for bad symbolism but has concrete and material effects upon the marketplace within which African literature operates, the ways in which the West and ���Rest��� consume African literature.

This LitNobel for Gurnah has held up the mirror to publishers, editors, agents and critics. In the US, no one can find his books for purchase or public libraries. Many friends in my tiny circle of African literature lovers have been called by the US media to offer comments and pull quotes, there is a scramble to gain more information on him. The truth is crystal clear: US publishing is truly hostile to African literature. Here, only one, two, three writers are held up to represent an entire continent of over fifty countries and a gazillion languages, cultures, landscapes.

The visibility factor will drastically change for Gurnah and rights for his books will get bought up and the books will also get bigger distribution. But what about the countless other new and old literary works from the African continent?

But, first we’ll take this win.

A matter that defies tears

Photo by ib daye on Unsplash

Photo by ib daye on Unsplash W���le ���oyinka pulls Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, his third novel, out of a very deep well of passion, turbulent but empowering, for a writer pushing 90. It is a novel by turns angry, perplexed, and cynical, yet effusively solicitous of a principled outlook on life. The themes here resonate with those of the Nobel laureate���s dramas of moral decay (Madmen and Specialists, Opera Wonyosi, Requiem for a Futurologist). Stylistically, the novel is closer to his post-1998 prose works and the memoirs, especially Ibadan: The Penklemes Years and You Must Set Forth at Dawn. Years ago, ���oyinka told an interviewer, Jane Wilkinson, that ���the novel for me is not a very congenial form���I don���t even like the novel [and]���the kind of fiction which I really enjoy is good science-fiction.���

Reading this unusual novel clarifies his reasons. His achievements here, it seems, are those of a writer unable to trust any other form to bear the weight of his desire in accounting for the state of things in his homeland. This is fictional Nigeria, assuming that isn���t a tired tautology, a story about everything that is happening in a country caught in the crosshairs of unimaginable events. Religious terrorism���alias Boko Haram���operates in lockstep with unhindered kidnapping, illegal gold mining fuels widespread insecurity even across the borders, and the predatory teeth of the powerful sharpen themselves on the entrails and other body parts of the powerful-to-be. ���oyinka simply sets it all down, even at the risk of doing violence to novelistic conventions best suited to his narrative.

A drama of colorful characters, from the religious charlatan Papa Davina (alias Teribogo, alias Gardener of Souls), supremo at Villa Potencia, to Sir Goddie Danfere, the Prime Minister not too overwhelmed by matters of state to ignore petty social intrigues, to Chief Modu Udensi Oromotaya (proprietor of the morbidly named National Inquest). There is the counter-force known as the Gong o��� Four���Badetona (The Scoffer), the surgeon Kighare Menka, Duyole Pitan-Payne and Farodion���the last of whom is missing in action since their parting in college, until a sleight-of-hand reference reveals his identity in the novel���s final pages. There is The Family, comprising the three siblings of Duyole, his first son, and the patriarch, Otunba Pitan-Payne, alias Pop of Ages, the collective antagonist in the thriller that takes up one-fifth of the novel. There are the women, too; each passionate and steadfast, none too misty-eyed to be sold a lie.

Duyole Pitan-Payne, ���engineer and non-conformist man of business,��� has a new position at the United Nations, and he visits the seat of government to meet Sir Goddie, ostensibly to be celebrated for the recognition. But a plot is afoot���one so thick and subterranean even this self-aware man of the world has no idea of its existence, let alone its dimension. Why does the shrewd Badetona take to his heels at the mere sight of the inner (or outer?) sanctums of Villa Potencia, only to lapse into eternal silence after a spell in detention? Is there more to the membership of a lodge shared by the prime minister, the Otunba, and Papa Davina?�� Why would the prime minister give a private audience to a foreigner engaged in illegal gold mining? What is the connection between the ���business proposition��� to Menka by three shadowy visitors and the fire that soon obliterates Hilltop Manor, his club-cum-residence? Everything is happening, but nothing is as it seems. Homeless overnight, Menka accepts his friend Duyole’s invitation to relocate to Lagos���to Badagry, in fact���and the two briefly renew their faith in the Gong and its lingo, which is ���more reliable in gesture, tone and context than meaning specific.���

The reunion is an opportunity for Duyole to start tinkering with the Codex Seraphinianus, the secret code of the cartel behind the traffic in human body parts, whose emissaries recently accosted Menka with the business proposition. In his line of work as a surgeon, Menka has had to operate on the victims of Boko Haram bombings and Sharia scalpels. He has seen all the horror. Despite his and his friend���s jaded views of human life in Nigeria, however, they never imagine the level of degradation at which the cartel operates. Cracking the code becomes a matter of duty, if they must restore a semblance of life to the values that they have spent their long friendship cultivating. With Badetona silenced, and Farodion unaccountably missing, the two Gong members come to stand for the novel’s protagonist. A blast goes off in Duyole’s study moments before he breaks the code, as though his fingers are the ones on the fuse. The remaining two-fifths of the novel takes up the saga of seeking medical help for him abroad and, failing that, bringing the body home for a decent burial. All in the face of implacable opposition from his family.

The bombing is an insider job. The Family is in it up to its neck, although with the exception of Damien, Duyole’s son, we are not shown exactly how. It is enough that Otunba’s preferences cast a spell on everyone. In a move that readers familiar with the moral universe of Soyinka’s work will readily recognize, Menka takes up the challenge of saving his friend’s brittle life, going through a series of episodes like a sequence from a crime thriller. The friendship between him and Duyole will rank among the most exemplary in African literature. If literature is a reflection of the rhythms of linguistic life, ���tight from heaven, like Duyole and Menka��� ought to be an idiom about friendship. The surgeon’s lack of family (nuclear or extended) contrasts sharply with Duyole’s, although it becomes clear, as the drama of saving his life unfolds, that the latter���s natal community is resolved to undermine everything he stands for.

Slightly short of five hundred pages, Chronicles is a gushing narrative, perhaps overly so. There is not a single timorous moment. Every page of it crackles with the barely restrained rage of a writer at the end of his patience, but constrained to seek release in high humor, the kind he has spent an entire career perfecting. The range of celebratory Nigeriana is on view here, the world of multiplying acronyms inhabited by a people for whom, it seems, happiness is invented. The Festival of the People’s Choice. Brand of the Land. Yeoman of the Year. People���s Award for Common Touch.

The first section of the chapter titled ���The Scoffer’s Progress,��� seen from Badetona���s point of view, reveals a cynical but profound insight into the psychological aspects of Nigerian life. Papa Davina���s profile is something of a charlatan���s itinerary, and the reader comes away with the chastening knowledge that this morally vacuous person was once part of the Gong o��� Four.

In another moment, daily existence is no more than ���…a cozy cohabitation between two religions which, a mere kilometer or two from that very spot [the presidential villa], held each other by the throat to be piously squeezed or slit at little or no provocation.��� At yet another unnerving moment, a character observes: ���We are ringed by new abominations every day, acts you never could have contemplated in your youth–all have become commonplace.��� None of these denies Chronicles its fragrance. Moments of pleasant surprise appear, such as the affectionate detour on classical music, and a thumbnail focus on Austria. The long, somewhat Kafkaesque exchange between Menka and a man in the dark before Hilltop Manor burns down is reminiscent of the Indonesian shadow play. A brief but intense reflection on female grief shows the depths of empathy to which ���oyinka plumbs to ameliorate what may come across as an excessive focus on starring males.

Like ���oyinka���s two other novels, The Interpreters and Season of Anomy, this is written from an omniscient perspective. Unlike them, there is an undertone of sarcasm throughout, rising to an overtone of exasperated cynicism. In one sense, it is an indication that this is a work of satire, fitting for the company of the plays mentioned earlier. One could go so far as to claim that, other than Opera Wonyosi, The Beatification of Area Boy, and the volumes in the Interventions series, Chronicles is the next thing ���oyinka has written that is so totally invested in the political and moral puzzle that is Nigeria. It is, for that reason, deeply committed to a utopian vision, and there is nothing odd in seeing utopia in a satirical work, for the one is always secretly active in the sphere of influence of the other.

In another sense, the style is better suited to a narrative in the first-person perspective. That perspective would be Menka���s, the closest person to Duyole (who, in a way, looks like a revised version of ���ekoni, the visionary engineer in The Interpreters). In fact, it is conceivable to think of Menka as the novel���s central character, the one endowed with the greatest narrative authority. A native of Gumchi, a fictional town in Plateau State, Menka is also about the closest ���oyinka has moved to creating a non-Yoruba protagonist, far from the singular avatar based on Ogun, the Yoruba deity that serves as the metaphor for his creative idealism.

Perhaps this was the point of that literary conceit all along: to fashion a creature of sensibilities from a given culture and set if free of the original mooring because hallowed be all earth, including rocky, backwater Gumchi. Urban Jos, one of Nigeria���s most cosmopolitan cities, is Menka���s professional home, but it has also become a site of heedless ethnic and religious violence over the past decade. His reflections are everywhere touching and heartfelt, and the arresting description of the fire at the Hilltop Manor goes on for over two pages of closely observed detail, entirely from his point of view. The sections of the novel that put the thoughts and desires of these friends at the center are always the most compelling and emotionally rewarding. Menka may turn out to be the writer’s best-realized character, irrespective of genre.

A drawback of the style is that, except in a few minor cases, all the characters are wily, cynically knowing or opaque, and only intentions separate compassionate characters such as Menka from venal ones like Papa Davina and Sir Goddie. There are consequential differences between the Nigerian and US editions of the novel, but still, the sprawling storytelling could have used more control and proportion, skills that the author typically commands. In an ethical gesture to one of his abiding critiques, ���oyinka chooses to place the Pitan-Payne family home in Badagry, the better to focus on the legacies of Atlantic slave trade. It is odd, though, to contemplate the notion of any African family deriving its fortunes from the slave trade. Status maybe; African receipts in the trade were mostly on the order of an impossible exchange.

���oyinka has written and published continuously for over 60 years, and he has everything to show for it. A novel of this kind, in scope and depth, at this stage of his career is a surpassing achievement. Even if Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth were the only thing that he ever wrote about Nigeria, it would be sufficient.

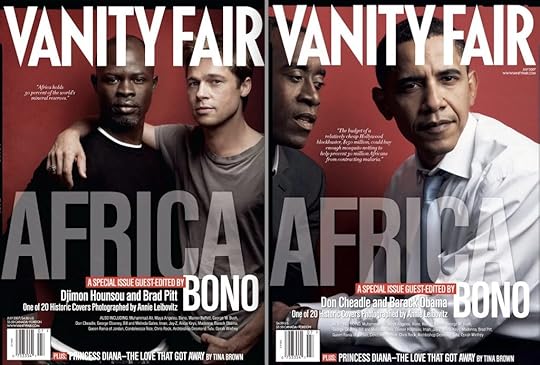

Bono’s vanity

On June 15, 2007, Tony Karon published a post I wrote for his then, very popular, blog, Rootless Cosmopolitan, about the magazine Vanity Fair’s “Africa” issue. Euro-American media doing special “Africa” issues was the thing back then. I had met Tony via our daughters chance meeting in a Brooklyn, New York public park. They announced during introductions that both heir fathers were South African. Soon Tony and I discovered our mutual Cape Town connections and talked politics. Which is how he asked me what I thought of the Vanity Fair issue. Tony’s description of me at the time seems quaint now: “… guest columnist Sean Jacobs, a fellow Capetonian who these days divides his time between Brooklyn and Ann Arbor, where he is an assistant professor of Communication Studies and African Studies at the University of Michigan. He describes himself as ‘a frustrated journalist’ (is there any other kind?), and in his spare time edits the online edition of Chimurenga magazine. In 2004 he directed the��Ten Years of Freedom Film Festival in New York City in April 2004.” The “edits the online edition” of Chimurenga is a bit of poetic license (I was asked to figure out what the online version of Chimurenga should look like). If you ask Ntone Edjabe of Chimurenga, trying to do that for Chimurenga is perhaps what inspired me “go across the street” and start a new storefront eventually: what became Africa Is a Country. At the time, I was also blogging as Leo Africanus.) As for the piece, I still like the piece and I think it aged nicely, though now it reads like an audition to take Bono’s gig (LOL) and I look stupid for calling Barack Obama “the US presidential long shot.” In any case, it is still worth revisiting�� for how Africa was being defined among Western elites and their media in the 2000s.

In 1965, the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene wrote and directed���against the odds, with minimal support from his government and a few French patrons, and as a director with meager cinematic background���the film “Le noir de ��� (Black Girl)” about a young Senegalese immigrant domestic working for a French family in Antibes.

The film, the first feature directed by a black African, was hailed at the time by New York Times critic A.H. Weiler (in now outdated language) as ���put[ing] a sharp, bright focus on an emerging, once dark African area and on a forceful talent with fine potentials.��� Sembene died [on June 9, 2007] at 84 after an illustrious career, saluted by another New York Times critic, A.O. Scott,��for being as uncompromising in his criticism of Africa���s post-liberation regimes as he had been of French colonial domination. More importantly, Scott pointed out, Sembene was also passionate about celebrating the equality of Africa with the West: ���He believed that Africans would experience true liberation when they threw off European models and discovered their own, homegrown versions of modernity.���

One can only wonder what Sembene might have achieved with the resources made available to former rock star Bono in his recent role as guest editor of��a special ���Africa��� issue of the high-end monthly��Vanity Fair.

Africa, of course, is now everyone���s pet cause. It offers Euro-American political leaders unpopular at home an opportunity to shine [whenever they go on visits there or through development aid], and for Hollywood actresses and former and current pop stars to be seen doing their bit for humanity by lining up to visit the continent (mainly its children) or pleading its case in Western capitals.

Bono, especially, has built a new career as a savior of Africa and [in the issue] makes much of pulling out all stops to plead the continent���s case���his access to the corridors of power makes him a lot more effective in this role than his pop predecessor [in this line of work], Bob Geldof.

In March this year, the U2 frontman who has accomplished the remarkable feat of being a friend to Nelson Mandela and George W. Bush simultaneously, announced he would guest edit the special Africa issue of Vanity Fair, which would ���rebrand Africa��� for the magazine���s well-heeled readership and advertisers. His intentions were noble: ���When you see people humiliated by extreme poverty and wasting away with flies buzzing around their eyes, it is easy not to believe that they are same as us,��� he said.

Capturing the energy of a continent with 890 million and 54 countries in one issue of a magazine was always going to be a tall order, but even then, Bono and his team gets it really wrong. The key personnel included the head of communication of Bono���s RED Campaign as well as the actor Djimon Hounsou, who is credited as a ���consultant.��� And it shows. At times it looks like another ad for the RED Campaign.

It is never entirely clear whether the purpose of the edition is to showcase Africa ��� or people who promote Africa in the West, especially within the United States?

Much has been made of the issue���s twenty different covers. Twenty-one ���prominent people��� photographed by Annie Liebovitz in groups of two and three in a series meant to depict a ���conversation��� about Africa���she called it a ���visual chain letter ��� spreading the message from person to person.���

The result of all that planning and effort (the real editor Graydon Carter lists Liebovitz���s flight schedule in his ���editor���s letter���) is hardly extraordinary���though I was intrigued by, if not sure what to make of, the curious shot of Madonna apparently sniffing Maya Angelou.

Only three of those featured are actual Africans: the actor (and editor���s consultant) Djimon Hounsou, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Iman. (Three and a half, if you count U.S. presidential long shot Barack Obama, another cover model, by virtue of being the son of a Kenyan economist.)

Not exactly a new brand of Africa: Hounsou is largely a product of Hollywood; Tutu, with respect, has retired from his life as an activist cleric; and Iman���s only qualification is that she was a well-known model in 1980s.

As for the non-Africans featured on the cover, if some of these are Africa���s friends, it does not need enemies. President George W. Bush and his Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice are a particularly odd choice���incidentally, they are pictured in a strangely intimate moment with Condi seeming to tug at George���s arm, as if the image was designed to provoke titillated speculation in the U.S. media.

Vanity Fair is not a news magazine, and therefore usually avoids putting people it dislikes on its cover. Carter, in his editor���s note, reveals his differences with Bono about including Bush and Rice, but the rock star appears to believe Bush���s Africa policies may be the ���silver lining��� of the current U.S. administration. But if silver linings were the criteria, then Thabo Mbeki, probably the most recognizable African political leader for his promotion of democracy, good governance and economic development, ought to have been included���perhaps Editor Bono deems Mbeki���s strange politics on HIV/AIDS and his ���quiet diplomacy��� on the crises in Zimbabwe are somehow worse than the Iraq war.

As for as strange cover choices go, though, Queen Rania of Jordan tops this list. I hope it was not because Bono thought Jordan was an African country.

A group of actual Africans profiled as representing the ���spirit��� of the continent������activists, artists, doctors, athletes, entrepreneurs, economists��� are given more limited treatment in short paragraph-length descriptions of their achievements.

The feature articles are written by go-to ���Africa hands��� in the United States, including Christopher Hitchens (offering a rambling stream of consciousness piece of Tunisia that recycles some earlier reporting), Sebastian Junger (a journalist described elsewhere as fascinated with ���extreme situations and people at the edges of things���), and Spencer Wells (an ���explorer-in-residence at National Geographic���). Only one actual African contributor, Binyavanga Wainaina on contemporary Kenya, made the cut.

Youssou N���Dour, the Senegalese singer, is credited as a contributor for a piece on a music festival in Mali written by a former MTV executive, but that appears more like a transparent attempt to counter criticism of the magazine���s editors for the limited African ���voice��� in the magazine.

The big profiles go to anti-poverty economist Jeffrey Sachs (Bono���s friend) and the late Princess Diana���since the issue appeared, much of the mainstream coverage has been about how this article, and an accompanying book, could resurrect the career of Tina Brown. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton writes on Nelson Mandela and Brad Pitt plays journalist by asking Archbishop Desmond Tutu really silly questions. Having praised South Africa for going the route of ���restorative justice������last time I checked nothing of the sort happened���Pitt has a follow-up question for Tutu: ���Then it is worth asking what is the outcome for societies who have rushed toward retributive justice, like the Shia in Iraq?��� Huh? Madonna gets to redeem herself after her bungled adoption of a Malawian child: she is doing a documentary on orphans in Malawi now.

Nothing substantial is written about the continent���s most populous and vibrant region, West Africa (except for the article on the music festival in the Malian desert). South Africa, the continent���s richest country (with Johannesburg slowly emerging as the continent���s cultural and media capital as the paragraph-length feature on the Africa Channel and the drooling photograph of actress Terry Pheto of the film��Tsotsi��suggests) gets short shrift. Apart from the Clinton piece on Mandela (which, typical of the tradition here, reduces the former guerrilla to saintly grandfather) and the Pitt ���interview��� with Tutu, there is nothing that captures some of the struggles to define this new Africa.

Nevertheless, on the upside, publications like the Cape Town-based literary and politics magazine��Chimurenga��(full disclosure: I am its online editor) and ���new wave��� writers such as Wainaina,��Orange Prize-winner Chimamanda Adichie, Doreen Baingana and Mohamed Magani, among others, are getting some helpful exposure to new (and well-heeled) audiences and readers. And there���s some well-deserved attention for the��AIDS activism of people like Zackie Achmat��and the global justice campaigner Archbishop Ndungane (Tutu���s successor as Anglican prelate in South Africa, who would have been a more contemporary choice for the cover image), among others.

Also recognized is the tireless work of New York African Film Festival director Mahen Bonetti, as well as the filmmakers Teddy Mattera, Gaston Kabore, Jean Marie Teno, and Safi Feye who all, unfortunately, are featured only in a group photo, with their work summed up in one paragraph. The coverage of these figures, however, is very minimal.

But even these upsides are spoiled by the sloppiness of the magazine. According to one of my sources, the one substantive article on the actual work of Africans (apart from Wainaina���s piece on Kenya)���an omnibus article on the continent���s ���literary renaissance��� by Elissa Scappell and Rob Spillmann���contains a lot of untruths and plain invention.

For one, Nadine Gordimer, part of the old guard of African letters is described as a ���founder member of the African National Congress��� and the ���conscience of South Africa.��� Uh, the ANC was founded in 1912, 11 years before Gordimer���s birth, and only opened its membership to whites in 1969. As for Gordimer being the ���conscience of South Africa,��� I���m not sure you���d find many South Africans who would have accorded her such prominence in the national imagination.

It also appears that description of the event at the heart of the article���the SLS Kenya/Kwani? Literary Festival���is a bit off base. According to my source (who like me, is a fan of Adichie���s novels) the descriptions of ���standing room only��� readings given by her in Nairobi, is more an attempt by the writers of the articles to make the story fit the issue���s hype. On the night she read at the University of Nairobi, most festival visitors opted instead to go listen to the much older Ugandan writer Taban Lo Liyong, who was reading in the room next door.

In the end, reading Bono���s Vanity Fair Africa branding edition leaves me remembering what a friend of mine says when he feels he���s been had: ���As Fela would say, this is ���expensive shit���.���

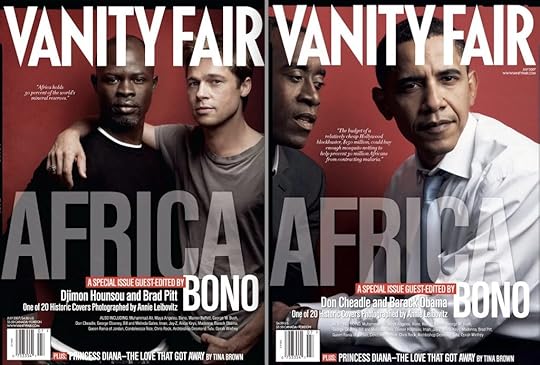

Bono’s Vanity

On June 15, 2007, Tony Karon published a post I wrote for his then, very popular, blog, Rootless Cosmopolitan about the magazine Vanity Fair’s “Africa” issue. The subject of the post���Euro-American magazines publishing their regular fair (Euro-American focuses and then doing special “Africa” issues) was the thing back then. Tony, who I had met���via our daughters chance meeting in a Brooklyn, New York public park and declaring to each other that their fathers were South African and we then discovering our mutual Cape Town connections���had asked me what I thought of the Vanity Fair issue. Tony’s description of me at the time seems quaint now: “… guest columnist Sean Jacobs, a fellow Capetonian who these days divides his time between Brooklyn and Ann Arbor, where he is an assistant professor of Communication Studies and African Studies at the University of Michigan. He describes himself as ‘a frustrated journalist’ (is there any other kind?), and in his spare time edits the online edition of Chimurenga magazine. In 2004 he directed the��Ten Years of Freedom Film Festival in New York City in April 2004.” The “edits the online edition” of Chimurenga is a bit of poetic license, but also, if you ask Ntone Edjabe of Chimurenga, is perhaps what inspired me “go across the street” and start a new storefront eventually: Africa Is a Country. (At the time, I was blogging as Leo Africanus.) As for the piece, I still like it, though it reads like an audition to take Bono’s gig (LOL) and I look stupid for calling Barack Obama “the US presidential long shot.” In any case, it is still worth revisiting�� for how Africa was being defined among Western elites and their media in the 2000s.

In 1965, the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene wrote and directed���against the odds, with minimal support from his government and a few French patrons, and as a director with meager cinematic background���the film “Le noir de ��� (Black Girl)” about a young Senegalese immigrant domestic working for a French family in Antibes.

The film, the first feature directed by a black African, was hailed at the time by New York Times critic A.H. Weiler (in now outdated language) as ���put[ing] a sharp, bright focus on an emerging, once dark African area and on a forceful talent with fine potentials.��� Sembene died [on June 9, 2007] at 84 after an illustrious career, saluted by another New York Times critic, A.O. Scott,��for being as uncompromising in his criticism of Africa���s post-liberation regimes as he had been of French colonial domination. More importantly, Scott pointed out, Sembene was also passionate about celebrating the equality of Africa with the West: ���He believed that Africans would experience true liberation when they threw off European models and discovered their own, homegrown versions of modernity.���

One can only wonder what Sembene might have achieved with the resources made available to former rock star Bono in his recent role as guest editor of��a special ���Africa��� issue of the high-end monthly��Vanity Fair.

Africa, of course, is now everyone���s pet cause. It offers Euro-American political leaders unpopular at home an opportunity to shine [whenever they go on visits there or through development aid], and for Hollywood actresses and former and current pop stars to be seen doing their bit for humanity by lining up to visit the continent (mainly its children) or pleading its case in Western capitals.

Bono, especially, has built a new career as a savior of Africa and [in the issue] makes much of pulling out all stops to plead the continent���s case���his access to the corridors of power makes him a lot more effective in this role than his pop predecessor [in this line of work], Bob Geldof.

In March this year, the U2 frontman who has accomplished the remarkable feat of being a friend to Nelson Mandela and George W. Bush simultaneously, announced he would guest edit the special Africa issue of Vanity Fair, which would ���rebrand Africa��� for the magazine���s well-heeled readership and advertisers. His intentions were noble: ���When you see people humiliated by extreme poverty and wasting away with flies buzzing around their eyes, it is easy not to believe that they are same as us,��� he said.

Capturing the energy of a continent with 890 million and 54 countries in one issue of a magazine was always going to be a tall order, but even then, Bono and his team gets it really wrong. The key personnel included the head of communication of Bono���s RED Campaign as well as the actor Djimon Hounsou, who is credited as a ���consultant.��� And it shows. At times it looks like another ad for the RED Campaign.

It is never entirely clear whether the purpose of the edition is to showcase Africa ��� or people who promote Africa in the West, especially within the United States?

Much has been made of the issue���s twenty different covers. Twenty-one ���prominent people��� photographed by Annie Liebovitz in groups of two and three in a series meant to depict a ���conversation��� about Africa���she called it a ���visual chain letter ��� spreading the message from person to person.���

The result of all that planning and effort (the real editor Graydon Carter lists Liebovitz���s flight schedule in his ���editor���s letter���) is hardly extraordinary���though I was intrigued by, if not sure what to make of, the curious shot of Madonna apparently sniffing Maya Angelou.

Only three of those featured are actual Africans: the actor (and editor���s consultant) Djimon Hounsou, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Iman. (Three and a half, if you count U.S. presidential long shot Barack Obama, another cover model, by virtue of being the son of a Kenyan economist.)

Not exactly a new brand of Africa: Hounsou is largely a product of Hollywood; Tutu, with respect, has retired from his life as an activist cleric; and Iman���s only qualification is that she was a well-known model in 1980s.

As for the non-Africans featured on the cover, if some of these are Africa���s friends, it does not need enemies. President George W. Bush and his Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice are a particularly odd choice���incidentally, they are pictured in a strangely intimate moment with Condi seeming to tug at George���s arm, as if the image was designed to provoke titillated speculation in the U.S. media.

Vanity Fair is not a news magazine, and therefore usually avoids putting people it dislikes on its cover. Carter, in his editor���s note, reveals his differences with Bono about including Bush and Rice, but the rock star appears to believe Bush���s Africa policies may be the ���silver lining��� of the current U.S. administration. But if silver linings were the criteria, then Thabo Mbeki, probably the most recognizable African political leader for his promotion of democracy, good governance and economic development, ought to have been included���perhaps Editor Bono deems Mbeki���s strange politics on HIV/AIDS and his ���quiet diplomacy��� on the crises in Zimbabwe are somehow worse than the Iraq war.

As for as strange cover choices go, though, Queen Rania of Jordan tops this list. I hope it was not because Bono thought Jordan was an African country.

A group of actual Africans profiled as representing the ���spirit��� of the continent������activists, artists, doctors, athletes, entrepreneurs, economists��� are given more limited treatment in short paragraph-length descriptions of their achievements.

The feature articles are written by go-to ���Africa hands��� in the United States, including Christopher Hitchens (offering a rambling stream of consciousness piece of Tunisia that recycles some earlier reporting), Sebastian Junger (a journalist described elsewhere as fascinated with ���extreme situations and people at the edges of things���), and Spencer Wells (an ���explorer-in-residence at National Geographic���). Only one actual African contributor, Binyavanga Wainaina on contemporary Kenya, made the cut.

Youssou N���Dour, the Senegalese singer, is credited as a contributor for a piece on a music festival in Mali written by a former MTV executive, but that appears more like a transparent attempt to counter criticism of the magazine���s editors for the limited African ���voice��� in the magazine.

The big profiles go to anti-poverty economist Jeffrey Sachs (Bono���s friend) and the late Princess Diana���since the issue appeared, much of the mainstream coverage has been about how this article, and an accompanying book, could resurrect the career of Tina Brown. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton writes on Nelson Mandela and Brad Pitt plays journalist by asking Archbishop Desmond Tutu really silly questions. Having praised South Africa for going the route of ���restorative justice������last time I checked nothing of the sort happened���Pitt has a follow-up question for Tutu: ���Then it is worth asking what is the outcome for societies who have rushed toward retributive justice, like the Shia in Iraq?��� Huh? Madonna gets to redeem herself after her bungled adoption of a Malawian child: she is doing a documentary on orphans in Malawi now.

Nothing substantial is written about the continent���s most populous and vibrant region, West Africa (except for the article on the music festival in the Malian desert). South Africa, the continent���s richest country (with Johannesburg slowly emerging as the continent���s cultural and media capital as the paragraph-length feature on the Africa Channel and the drooling photograph of actress Terry Pheto of the film��Tsotsi��suggests) gets short shrift. Apart from the Clinton piece on Mandela (which, typical of the tradition here, reduces the former guerrilla to saintly grandfather) and the Pitt ���interview��� with Tutu, there is nothing that captures some of the struggles to define this new Africa.

Nevertheless, on the upside, publications like the Cape Town-based literary and politics magazine��Chimurenga��(full disclosure: I am its online editor) and ���new wave��� writers such as Wainaina,��Orange Prize-winner Chimamanda Adichie, Doreen Baingana and Mohamed Magani, among others, are getting some helpful exposure to new (and well-heeled) audiences and readers. And there���s some well-deserved attention for the��AIDS activism of people like Zackie Achmat��and the global justice campaigner Archbishop Ndungane (Tutu���s successor as Anglican prelate in South Africa, who would have been a more contemporary choice for the cover image), among others.

Also recognized is the tireless work of New York African Film Festival director Mahen Bonetti, as well as the filmmakers Teddy Mattera, Gaston Kabore, Jean Marie Teno, and Safi Feye who all, unfortunately, are featured only in a group photo, with their work summed up in one paragraph. The coverage of these figures, however, is very minimal.

But even these upsides are spoiled by the sloppiness of the magazine. According to one of my sources, the one substantive article on the actual work of Africans (apart from Wainaina���s piece on Kenya)���an omnibus article on the continent���s ���literary renaissance��� by Elissa Scappell and Rob Spillmann���contains a lot of untruths and plain invention.

For one, Nadine Gordimer, part of the old guard of African letters is described as a ���founder member of the African National Congress��� and the ���conscience of South Africa.��� Uh, the ANC was founded in 1912, 11 years before Gordimer���s birth, and only opened its membership to whites in 1969. As for Gordimer being the ���conscience of South Africa,��� I���m not sure you���d find many South Africans who would have accorded her such prominence in the national imagination.

It also appears that description of the event at the heart of the article���the SLS Kenya/Kwani? Literary Festival���is a bit off base. According to my source (who like me, is a fan of Adichie���s novels) the descriptions of ���standing room only��� readings given by her in Nairobi, is more an attempt by the writers of the articles to make the story fit the issue���s hype. On the night she read at the University of Nairobi, most festival visitors opted instead to go listen to the much older Ugandan writer Taban Lo Liyong, who was reading in the room next door.

In the end, reading Bono���s Vanity Fair Africa branding edition leaves me remembering what a friend of mine says when he feels he���s been had: ���As Fela would say, this is ���expensive shit���.���

October 6, 2021

EndSARS, workers��� power, and war

Photo by Eiseke Bolaji on Unsplash

Photo by Eiseke Bolaji on Unsplash The present shape of Nigeria���s ruling-class oppression goes back to the mid-1980s, with the imposition of a comprehensive structural adjustment program (SAP) by the military junta of Ibrahim Babangida. The SAP was a state campaign to implement the harsh and anti-welfarist conditions required by the loans taken from the World Bank and the IMF. Workers and youth have resisted the SAP, which has led to a drastic reduction in government sponsorship of social infrastructure, such as education, healthcare, housing, and job creation. The SAP is why most industries in glass, textiles, agriculture, automobile, and so on, were decimated by privatization and other neoliberal policies that transfer public wealth into private pockets. The business empires of a few billionaires are then bolstered through monopoly, hoarding, and other diabolical policies, while millions of people live in abject poverty.

The country���s legacy of police brutality is the kernel of these decades of oppression, as epitomized by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) of the Nigerian Police Force. Following the unit���s founding in 1992, amid a rash of kidnappings and robberies in the city of Lagos, SARS officers���often dressed in plainclothes���were ostensibly tasked with the investigation and prosecution of individuals suspected of ���violent crimes.��� The covert unit has since been implicated in a long and sordid history of abuse and brutality against civilians, including extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, extortion, blackmail, and forced disappearances; it has also been widely viewed as facilitating election rigging for the ruling parties. Popular resistance against the unit began with the birth of the #EndSARS movement in 2017, when youth activists began to organize mass mobilizations via social media. Soon, agitation against the criminal tendencies of SARS officers became widespread as citizens testified publicly about illegal harassment, torture, and extortion. By August 2019, some activists who had been part of the 2017 and 2018 #EndSARS protests had organized the #RevolutionNow campaign.

Subsequently, the ruling class, after pulling all its weight to win re-election for President Muhammadu Buhari in 2019, embarked on a sweeping campaign to authorize anti-people policies, including deregulation, the devaluation of the Nigerian naira, and refusal to require a meager 30,000 naira minimum wage (USD72.70). Buhari���s government also harshly suppressed two general strikes, in May 2016 and September 2020. These followed seven earlier general strikes, the last of which was in January 2012, against the removal of fuel subsidies, which involved workers in over 45 cities and towns across Nigeria.

Today, as workers��� power grows, many sleep with one eye open, as the hydra-headed horrors of violence and war rear their heads through both state and individual acts of terror. The Boko Haram war has shed the blood of thousands and turned citizens into ���internally displaced persons��� overnight. Hundreds of villages and towns are currently controlled by the insurgents. Bandits whose specialty is mass kidnapping, including recent abductions in the town of Kankara and at the Federal College of Forestry Mechanization in the state of Kaduna, have been terrorizing residents across the country.

Popular responses to these developments have taken two forms: first, self-determination (secessionist) groups, like the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and the Yoruba Nation agitators; and second, the #RevolutionNow movement, which has been the most consistent in sustaining struggles and has deployed strategies that have had a great influence on the wider #EndSARS movement, as well as on worker and youth struggles more generally. #RevolutionNow is also firm in its principle of the unity of all the oppressed.

The two souls of revolution���youth revolts, such as #EndSARS, and the rise in strikes that build workers��� power, like the Judiciary Staff Union���s shutdown of the courts in May of this year���must unite in order to give birth to a new Nigeria that rises from the ruins of the old.

In 2019, there were several major protests led by #RevolutionNow���campaigning alongside civil society groups Concerned Nigerians, Enough Is Enough, and others���against the shrinking of public spaces. On August 3, two days before a planned #RevolutionNow national protest, democracy activist and former presidential candidate, Omoyele Sowore, was arrested, gestapo-style by government security forces. Protests continued from August 5 until December 24, when Sowore was finally released. The Coalition for Revolution continued mass mobilizations from January 2020 until the one-year commemoration of the August 5 uprising, when protests were held in 14 cities and towns, including Abuja and Lagos, where more than 100 protesters were arrested and released within 48 hours.

As soon as comrades were released from the mass crackdown on August 5, planning for the next mass actions on October 1, Nigeria���s Independence Day, began. However, by October 1 the momentum had grown so much that the federal government had to cancel all Independence Day celebrations, with widespread mobilizations for mass actions underway���including on the part of self-determination groups like the Yoruba Nation agitators.

On the day itself, it was only the #RevolutionNow campaigners who stormed the streets.. On the heels of a betrayal of the people���s trust on the part of the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) and the Trade Union Congress (TUC), which had undemocratically called off a general strike scheduled for September 28, the October 1 protests finally broke the state���s hold on the opening of public spaces.

The current leaders of both national labor organizations have close ties to the state and tend to make more excuses for state actions than do government officials themselves. The general strike of April 2016, for instance, was intentionally sabotaged by the labor bureaucracy as they compromised with the Buhari government. State councils were mobilized in lackluster fashion while cowardly statements were made over the airwaves, demoralizing workers. The Joint Action Front and United Action for Democracy, leading radical groups in 2016, had been weakened through inactivity on the part of their leadership, as well by as the loyalty of many key activists to so-called class collaboration with the ���progressive bourgeoisie��� in the All Progressives Congress, one of Nigeria���s two main political parties. Despite many efforts at revival, neither group has yet recovered from these missteps.

However, workers continue to mount sectoral strike upon strike, from nurses and doctors to the current judiciary workers��� strikes over financial autonomy of the executive branch of government. In May, the Kaduna chapter of the NLC led a five-day workers��� strike in Kaduna State, where Nasir el-Rufai, a proud fascist, is governor. Labor has repeatedly brought state operations to a halt and fought off state thugs who are being sponsored to violently attack demonstrations.

But the bureaucracy still has considerable power, and it has shown that it can successfully suppress agitation for a general strike within the labor movement. In fact, many of those who participated in the #EndSARS protests were workers who would have loved their unions to formally join the movement and call a general strike.

As noted above, October 1, 2020, was a watershed, following the labor bureaucracy���s cancellation of the September 28 general strike. Confidence among activists was largely restored; as video of SARS brutality in Sapele trended globally, youth organizers began to plan a major intervention through the #EndSARS campaign. But, after only two of the campaign���s agenda setters on Twitter proposed actionable tactics, Omoyele Sowore of #RevolutionNow took up the baton with a proposal to occupy police headquarters all over the country; at the same time, Runtown, a well-known songwriter and producer, proposed a protest rally and march on Lagos Island.

By October 6, while 31 protesters who had been arrested during the #RevolutionNow protests on October 1 were being released, Sowore led a protest of thousands to police headquarters in Abuja. A small group of youth led by Rinu, a Twitter influencer and student activist, surrounded the Lagos Police Command with mats and music. About ten #RevolutionNow comrades joined them, and proceeded to hold a vigil at the Police Command. By the second day, protesters moved to the Lagos State Assembly Complex in Alausa, where hundreds of protesters joined. On the third day, Rinu and others in the leadership met with the Lagos State Assembly speaker Mudashiru Obasa and other legislators. Some agreements were drafted. Then, the leaders proceed to call off the protest���without consulting with the hundreds of protesters still dancing and singing outside.

By the second morning, thousands had joined the protests at Alausa, at which point a culture of congresses and democratic engagement and debate became the norm. For two days, the protesters debated whether the occupation should have leadership or demands. Many cited lessons learned from the betrayals of the labor bureaucracy and previous protests; accordingly, the first proposal, regarding the creation of leadership roles, was rejected. But the second proposal, to craft a list of demands, was accepted. So, at an afternoon congress on October 9, led by Sanyaolu, the now well known #5for5demands calling for drastic reforms were issued.

The Buhari government did not immediately respond to the demands. With help from singer-songwriter Davido and others, they were then presented to the inspector general of police. Over the next few days, the government made no concrete promises, and the revolt continued to grow all over the country. A congress in Alausa on October 13 saw the addition of two other demands, calling for the resignation of the inspector general and President Buhari, and the hashtag #EndBadGovernance began to trend widely. By October 17, more than 253 barricades had been mounted all over Lagos, even in far-flung neighborhoods.

Days earlier, state-sponsored thugs had been unleashed on protesters in the neighborhoods of Alausa, Lekki, and Oworonshoki. Protesters in Ketu, in particular, were the target of inter-cult attacks, while the police never intervened. Ruling party leader Bola Tinubu, along with President Buhari���s advisor Itse Sagay, had written on October 18 that the Buhari government should employ force to quell the protest. Many prominent former activists, including Debo Adeniran, Jiti Ogunye, and others, supported this position. Lagos State governor Jide Sanwo-Olu was also holding meetings with former activists and military and police leadership about how to stop the protests. In Abuja, thugs engaged protesters, burned their cars, and even threatened them���all live on air, while the police watched.

The #EndSARS protesters were aware of the credibility of such threats. The first martyr of the movement, Jimoh Isiaka, a student at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, had been felled by police bullets in Ogbomosho on October 11. All barricades of the #EndSARS nationwide held candlelight vigils and rallies in his honor. He was but one among numerous protesters who would be killed for their participation in the movement in the days to come.

A youth strike was declared at the Alausa barricade congress on the night of October 18, and by 5am the next morning, all workplaces were closed, given that transit routes were shut down. Only the protesters, in their millions, had free movement. The strike began to place increasing pressure on the working class, and activists called on the NLC and TUC to make it official by declaration. This was not to be.

After the massacre, many angry youth reacted by storming government establishments, including courthouses and police stations. More than 20 stations were burned in Lagos alone. Palaces and houses belonging to ruling-class elements���including the king of Lagos, Rilwan Akiolu, and Bola Tinubu���were attacked and looted. While these attacks were uncoordinated and poorly managed, the items emerging from these residences led to a great revelation: state governments and politicians were stealing and hoarding relief shipments intended to allay the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic! By comparison, the ���great lockdown��� had been enforced for nearly three months without citizens being given access to any of these supplies. In fact, #RevolutionNow campaigners had led a massive ���pots and pans��� protest online in April 2020 demanding access to healthcare.

The largest uncovering and mass rescue of COVID-19 relief was in the city of Jos, in Plateau State, where hundreds of thousands were pictured helping themselves to foodstuffs that had been withheld from the people. Lagos politicians were repackaging the COVID-19 relief supplies as ���stomach infrastructure,��� handed out to party members and supporters during birthday celebrations and other events.

The Lekki massacre halted the #EndSARS revolts, but it never broke the movement. As I write, the hashtag #EndSARS continues to trend. Illustrating the resilience of the movement, activists initiated #OccupyLekkiTollGate on February 13, 2021 at the city���s new toll plaza, against the plan of the Lagos government to start charging drivers to enter the city. Forty-six protesters were arrested, beaten, and tortured, yet the movement prevailed: as of this writing, the toll plaza remains closed.

There was, however, one thing that was missing in the #EndSARS revolt: general strikes by workers. After all, it was at the outset of the youth strike that the #EndSARS revolt became most effective. The state responded by drowning the protests in blood, from Lekki to Abuja. Even journalists were not spared. Pelumi Onifade, a 19-year-old reporter with GBUA TV was murdered for filming the recovery of pandemic relief supplies. Earlier, Onifade had broken news of the horrible event on October 21, 2020, where a member of the House of Representatives, Abiodun Bolarinwa, shot sporadically at protesters in the Abule Egba neighborhood in Lagos, killing three.

There are two ways forward in the current situation: to break up Nigeria, or to make revolution. Both will only happen under conditions approaching those of open warfare. The ruling class from north to south is united against both secession and revolution. They would prefer a coup, or a crackdown from the top. But if faced with the choice of either secession or revolution, the rulers would prefer secession.

Secession of the eastern state of Biafra would most likely lead to a civil war, which would favor local members of the ruling class. Many so-called ���baby tyrants��� would emerge, and conditions countrywide would deteriorate to resemble those in Somalia or South Sudan, where the situation, in popular street parlance, is described as ���yam pepper scatter scatter!��� In fact, many of the self-determination agitations are secretly backed by politicians eyeing the presidency in 2023. Those secessionist agitations serve as instruments to strengthen mass support in those regions. Yoruba Nation agitator Sunday Igboho recently proclaimed the obvious when he urged Bola Tinubu, the former Lagos governor and national leader of the ruling party, to agree to be president of the Yoruba Nation. Southeastern governors are equally united against IPOB and its military wing, the Eastern Security Network (ESN). The governors promptly launched a counterinsurgency outfit, codenamed ���Ebube Agu,��� that collaborates with government soldiers to confront IPOB/ESN.

However, the safest and the most harmonious solution is revolution. In the wake of #EndSARS, which struck fear into our thieving ruling class, a united action of all the oppressed is the way forward. In fact, the IPOB garnered its greatest support so far by joining the #EndSARS revolt.

The African Action Congress is the most consistent and largest revolutionary party involved in #EndSARS. There is a need for the party to work assiduously toward uniting all oppressed workers and youth under the banner of the #RevolutionNow campaigns, led by the Coalition for Revolution. In the north, the task is to build resistance against not only Boko Haram and the bandits, but also the neoliberal and pro-terrorism policies of the northern oligarchy. In the south, there is a dire need to intervene concretely to bolster support for workers��� strikes and unite them with youth agitations like #EndSARS.

What is needed is for the working class that organized the January 2012 uprising against the removal of fuel subsidies to collaborate with the #EndSARS movement. If these two boiling points burn together to produce the fire next time, a new Nigeria will be possible.

October 5, 2021

Louder in Lagos

Image credit Mike Calandra.

Image credit Mike Calandra. In the shadow of Nigeria’s 61st Independence Day, Africa Is a Country radio stops over in Lagos on its tour of African club cultures inspired by the Ten Cities book project. Unfortunately, due to a host of factors beyond our control, I wasn’t able to link up with Mallam Mudi Yahaya, cultural activist and essayist for the book’s Lagos chapter. But his essays did serve as a guide in the curation of the songs featured in this episode. I cannot recommend his essays enough as they serve as a sort of corrective to the general narrative around “Afrobeats” circulating in the international media.

That narrative is one that focuses on individual artists’ success, propelled by a general surprise around Africans’ access to wealth, itself fueled by a long tradition of single African stories. At a time when Wizkid has sneaked his way into our daily subconscious via the banal stream of mainstream radio, even making it on to that holy commercial grail of US black radio that black international stars have been trying to crack for decades, we would be wise to remember that the push and pull dynamics of national history that have shaped the Lagos music scene (and its urban environment in general) are inseparable from the music itself.

Take a listen on Worldwide FM or below via Mixcloud, and if you have an account there, go ahead and hit follow to keep up on all the latest episodes.

October 4, 2021

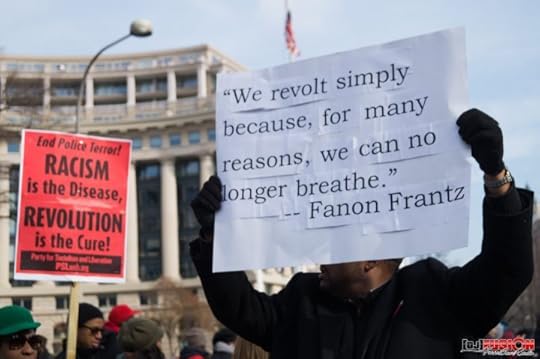

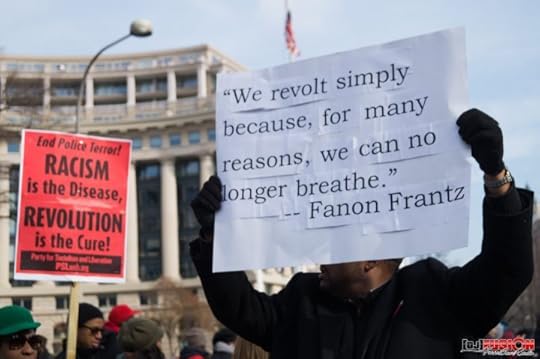

The Opacity of Fanon

Justice for All March, Washington DC, 2014. Credit Fusebox Radio via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Justice for All March, Washington DC, 2014. Credit Fusebox Radio via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. In this week���s episode of AIAC Talk, we speak to Professor Leswin Laubscher and Professor Derek Hook from Duquesne University, who with Miraj Desai, are editors of the upcoming book Fanon, Phenomenology, and Psychology (published by Routledge). From twentieth-century anti-colonial movements to contemporary struggles for racial and economic justice, Fanon remains a cherished source of political guidance���but how have his psycho-analytical and philosophical insights been neglected?

This is also the last episode where Sean joins us as a regular co-host. Will is taking up the baton as our solo regular host for now. Sean will be missed!

Watch short a video preview below, and listen to the whole show via podcast.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/37a64a6f-40e8-4faf-a10d-5010ac4af05f/aiac-talk-s2-ep2-fanon-ing.mp3The opacity of Fanon

Justice for All March, Washington DC, 2014. Credit Fusebox Radio via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Justice for All March, Washington DC, 2014. Credit Fusebox Radio via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. In this week���s episode of AIAC Talk, we speak to Professor Leswin Laubscher and Professor Derek Hook from Duquesne University, who with Miraj Desai, are editors of the upcoming book Fanon, Phenomenology, and Psychology. From twentieth-century anti-colonial movements to contemporary struggles for racial and economic justice, Fanon remains a cherished source of political guidance���but how have his psycho-analytical and philosophical insights been neglected?

This is also the last episode where Sean joins us as a regular co-host. Will is taking up the baton as our solo regular host for now. Sean will be missed!

Watch short a video preview below, and listen to the whole show via podcast.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/37a64a6f-40e8-4faf-a10d-5010ac4af05f/aiac-talk-s2-ep2-fanon-ing.mp3We don’t need no education

Photo credit Kristian Buus for The Stars Foundation via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Photo credit Kristian Buus for The Stars Foundation via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Since 2017, Kenya has incrementally adopted a new competency-based curriculum, and the state argues that it will be more responsive to the needs of learners. But as our author writes, not only has it been conceptualized and implemented in an “incoherent” and elite manner, it has also done nothing to change the institutionalized colonial injunction that posits real education as only that delivered through formal schooling. This piece is part of a series of posts republished from The Elephant. Wangui Kimari, one of our editorial board members, makes the selections.

This is a call to Kenyans of conscience to step back and reflect on the lies about education that are circulating in the media, the schooling system and government. Foreign sharks have camped in Kenya to distort our education. Using buzzwords such as ���quality��� and ���global standards���, these sharks seek to destroy the hopes, dreams, and creativity of young Africans, not just in Kenya, but in the whole region, and to make a profit while at it. With the help of local professors, bureaucrats and journalists, they spread hatred for education among the population. At the same time, they ironically create a thirst for schooling that makes parents resort to desperate measures to get their children into school, going as far as accepting violence and abuse in schools that causes children to take their own lives.

This insanity must end.

We must accept that education is a life endeavor through which people constantly adapt to their social and natural environment. Education is more than going to school and getting the right paper credentials. Education occurs anywhere where human beings process what they perceive, make decisions about it and act together in solidarity. That is why education, culture, and access to information are inseparable.

However, since colonial times, both the colonial and ���independence��� versions of the Kenya government have worked hard to separate education from culture and access to information. They have done so through crushing all other avenues where Kenyans can create knowledge. We have insufficient public libraries and our museums are underfunded. Arts festivals, where people come together and learn from unique cultural expressions, have been underfunded, and by some accounts, donors have been explicitly told not to fund creativity and culture. In the meantime, artists are insulted, exploited and sometimes silenced through censorship, public ridicule, and moralistic condemnations in the name of faith.

All these measures are designed to isolate the school as the only source of learning and creativity, and this is what makes the entry into schools so cutthroat and abusive.

But entering school does not mean the end of the abuse. Once inside the schools, Kenyans find that there is no arts education where children can explore ideas and express themselves. In school, they find teachers who themselves are subject to constant insults and disruptions from the Ministry of Education and the Teachers Service Commission. Under a barrage of threats and transfers, teachers are forced to implement the Competency Based training which is incoherent and has been rejected in other countries. Many of the teachers eventually absorb the rationality of abuse and mete it out on poor children whose crime is to want to learn. This desperation for education has also been weaponized by the corporate world that is offering expensive private education and blackmailing parents to line the pockets of book publishers.

By the end of primary and secondary school, only a mere three percent of total candidates are able to continue with their education. This situation only worsens inequality in Kenya, where only two percent of the population have a university degree, and where only 8,300 people own as much as the rest of Kenya.

But listening to the government and the corporate sector, you would think that 98 percent of Kenyans have been to university. The corporate sector reduces education to job training and condemns the school system as inadequate for meeting the needs of the corporations. Yet going by statements from the Kenya Private Sector Alliance (KEPSA) and the government, there is no intention to employ Kenyans who get training. The government hires doctors from Cuba and engineers from China, and then promises the United Kingdom to export our medical workers. KEPSA is on record saying that we need to train workers in TVET so that they can work in other African countries.

It is clear that the Kenya government and the corporate sector do not want Kenyans to go to school and become active citizens in their homeland. Rather, these entities are treating schooling as a conveyor belt to manufacture Kenyans for export abroad as labor and to cushion the theft of public resources through remittances.

The media and the church also join in the war against education by brainwashing Kenyans to accept this dire state of affairs. The media constantly bombards Kenyans with lies about the composition of university students, and with propaganda against ���useless degrees���. The church has abandoned prophecy and baptizes every flawed educational policy in exchange for maintaining its colonial dreams of keeping religion in the curriculum to pacify Kenyans in the name of ���morality���.

The government is now intending to restrict education further through the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) which seeks to limit education through pathways that prevent children from pursuing subjects of their interests, and by imposing quotas on who can pursue education beyond secondary school. At tertiary level, the government is devising an algorithm that will starve the humanities and social sciences of funding. It claims that funds will instead go to medical and engineering sciences, which are in line with Kenya���s development needs.

But recall that foreigners are doing the work of medical professionals and engineers anyway, so ���development��� here does not mean that Kenyan professionals will work in their home country. They will work abroad where they cannot be active citizens and raise questions about our healthcare and infrastructure.

The proposed defunding of the arts, humanities and social sciences aims to achieve one goal: to reserve thinking and creativity for the 3 per cent of Kenyans who can afford it. This discrimination in funding of university education is about locking the majority and the poor out of spaces where they can be creative and develop ideas. It also seeks to prevent Kenyans from humble backgrounds from questioning policies and priorities that are passed under dubious concepts such as ���development needs��� that are largely studied in the humanities and social sciences.

Clearly, there is a war against education and against Kenyans being creative and active citizens in their own country. For the 8,300 Kenyans to maintain their monopoly of resources, they need to distract Kenyans with propaganda against education, they need to limit Kenyans��� access to schooling, and they need to shut down alternative sources of training, information and knowledge. By limiting access to schooling and certificates, the 8,300 can exploit the work of Kenyans who have not been to school, or who have not gone far in school, by arguing that those Kenyans lack the ���qualifications��� necessary for better pay.

We must also name those who enable this exploitation. The greedy ambitions of the political class are entrenched by people who, themselves, have been through the school system. To adapt Michelle Obama���s famous words, these people walked through the door of opportunity, and are trying to close it behind them, instead of reaching out and giving more Kenyans the same opportunities that helped them to succeed. This tyranny is maintained by a section of teachers in schools, of professors in universities and of bureaucrats in government, who all fear students and citizens who know more than they do, instead of taking joy in the range of Kenyan creativity and knowledge. The professors and bureaucrats, especially, are seduced into this myopia with benchmarking trips abroad, are spoon-fed foreign policies to implement in Kenya. They harvest the legitimate aspirations of Kenya and repackage them in misleading slogans. For instance, they refer to limited opportunities as ���nurturing talent���, and baptize the government���s abandonment of its role in providing social services ���parental involvement.���

These bureaucrats and academics are helped to pull the wool over our eyes by the media who allow them to give Kenyans obscure soundbites that say nothing about what is happening on the ground. They also make empty calls for a return to a pre-colonial Africa which they will not even let us learn about, because they have blocked the learning of history and are writing policies to de-fund the arts and humanities. We must put these people with huge titles and positions to task about their loyalty to the African people in Kenya. We call on them to repent this betrayal of their own people in the name of ���global standards.���

We Kenyans also need an expanded idea of education. We need arts centers where Kenyans can meet and generate new ideas. We need libraries where Kenyans can get information. We need guilds and unions to help professionals and workers take charge of regulation, training and knowledge in their specializations. We need for all work to be recognized independent of certification, so that people can be paid for their work regardless of whether one has been to school or not.

We need recognition of our traditional skills in areas like healing, midwifery, pastoralism, crafts and construction. We need a better social recognition of achievement outside business and politics. It is a pity that our runners who do Kenyans proud, our scientists, thinkers, artists and activists who gain international fame, are hardly recognized in Kenya because they were busy working, rather than stealing public funds to campaign in the next election. Our ideas are harvested by foreign companies while our government bombards us with useless bureaucracy and taxes which ensure that we have no impact here.

Most of all, we need an end to the obsession with foreign money as the source of ���development���. We are tired of being viewed as merely labor for export, we are tired of foreigners being treated as more important than the Kenyan people. We are tired of tourism which is based on the tropes of the colonial explorer and which treats Africans as a threat to the environment. And the names of those colonial settlers who dominate our national consciousness must be removed from our landmarks.

Development, whatever that means, comes from the brains and muscles of the Kenyan people. And the key to us becoming human beings who proudly contribute to society and humanity is education. Not education in the limited sense of jobs and certificates, but education in the broader sense of dignity, creativity, knowledge, and solidarity.

October 1, 2021

As we lose our fear

The recent killings of two brothers���Benson Njiru Ndwiga, 22, and Emmanuel Mutura Ndwiga, 19, who had

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers