Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 121

July 29, 2021

An��lise da gest��o da COVID-19

Photo by Francisco Ven��ncio on Unsplash

Photo by Francisco Ven��ncio on Unsplash Em Angola, a pandemia �� a m��e da incompet��ncia. No discurso do estado da na����o, o Presidente Jo��o Louren��o declarou a pandemia COVID-19 respons��vel por todos os fracassos de 2020. Mas foi menos a pandemia em si do que a incompet��ncia na gest��o do estado que causou problemas.

Primeiro, vamos discutir a corrup����o, que �� prima pr��xima da incompet��ncia. Actualmente ao abrigo de acordo alargado ao abrigo do programa de financiamento ampliado com o FMI, o Estado angolano deve ser mais cuidadoso na gest��o dos fundos relancionados com a pandemia. Em julho de 2020 o FMI publicou um artigo intitulado ���Corruption and COVID-19,��� que clamava por uma gest��o transparente da pandemia. Durante a crise atual, o FMI afirmou que n��o se esqueceu de seu trabalho de governan��a e combate �� corrup����o. O FMI enfatizou que a pandemia exigia ampla interven����o dos governos, mas tamb��m alertou que ���os governos precisam de relat��rios oportunos e transparentes, auditorias ex post facto e processos de responsabiliza����o, bem como uma coopera����o estrita com a sociedade civil e o setor privado.���

Apesar das avalia����es positivas do FMI, o Estado angolano n��o tem sido t��o transparente quanto poss��vel na sua contabilidade nem disp��e de bons sistemas de fiscaliza����o.

As declara����es do estado de emerg��ncia p��blica e da calamidade p��blica em Mar��o e Maio de 2020, respectivamente, foram os raros momentos em que se discutiram os custos do COVID-19. Esta �� uma clara viola����o do direito �� informa����o. Na sequ��ncia de press��es de jornalistas e de algumas especula����es, a Ministra da Sa��de, Dra. S��lvia Lutucuta, em abril fez citar o custo total por paciente em cerca de 16 milh��es de kwanzas (quase $25,000). Seguidamente, em Junho, o ex Ministro de Estado e Chefe do Gabinete de Seguran��a do Presidente, General Pedro Sebasti��o, apresentou ao parlamento angolano o primeiro e ��nico relat��rio n��o detalhado sobre os custos da luta contra a COVID-19, argumentando que, o executivo tinha gasto (at�� �� data) o equivalente a $69.4 milh��es. Por fim, durante seu discurso no debate geral da ONU sobre a COVID-19 de dezembro de 2020, o presidente da Oi apresentou os custos em $ 164,6 milh��es, o que significa que as despesas mais do que dobraram em um periodo de seis meses. A TVRecord Angola calculou o custo por paciente em $ 10.715. Mesmo que o custo por paciente tenha ca��do, o custo por paciente em Angola �� seis vezes maior do que em outros lugares no mundo, como Portugal.

Os n��meros s��o grandes e a transpar��ncia exige estudos mais detalhados. Presos entre o precedente de defer��ncia aos poderes executivos e as ��reas cinzentas da interpreta����o jur��dica, os membros do Parlamento n��o auditam os relat��rios do Estado. E isso apesar do fato de den��ncias quase di��rias sobre o envolvimento de altos funcion��rios do Estado em esc��ndalos como os que envolvem a importa����o de EPI; a constru����o de instala����es para abrigar hospitais de campanha; a falta de material descart��vel nos hospitais p��blicos; e exames insuficientes para m��dicos. A presen��a de EPI nas m��os de vendedores ambulantes nas ruas de Luanda �� marcante. Tendo em vista que a ind��stria local est�� produzindo bens e o estado tem o monop��lio da importa����o de EPI e do apoio externo, a falta de m��scaras e luvas nos hospitais p��blicos �� inaceit��vel.

N��o �� surpreendente que a Transpar��ncia Internacional tenha classificado Angola na 142a posi����o (de 180 pa��ses) em 2020. Um estudo que analisou a promo����o da transpar��ncia nos pa��ses subsaarianos estabeleceu dez indicadores, dos quais Angola n��o atingiu nenhum.

Al��m da falta de transpar��ncia na gest��o dos recursos da COVID e da incompet��ncia demonstrada na produ����o do EPI, o Estado tamb��m falhou em garantir a seguran��a p��blica. Nos primeiros dois meses de implementa����o do estado de emerg��ncia, as for��as de seguran��a causaram mais mortes do que a COVID-19. A viol��ncia pol��tica �� mais mortal do que a pandemia.

A morte de um pediatra, Dr. S��lvio Dala, v��tima da brutalidade policial, desencadeou uma onda de rep��dio nacional que levou a protestos tamb��m de m��dicos. Outros cidad��os foram mortos, baleados ou espancados at�� a morte, por n��o usarem m��scaras, mesmo quando estavam sozinhos em seus carros.

Muitas medidas tomadas em Angola levam-nos a crer que estamos diante de decisores pouco capazes que desconhecem a realidade da maioria dos angolanos. O jornalista Jo��o Armando em editorial publicado em Abril de 2021 escreveu que ���o combate �� corrup����o �� fundamental, mas o combate �� incompet��ncia tamb��m.��� Ele observa que ���os mais competentes s��o mais interessados, d��o mais opini��es, querem fazer mais altera����es, mas acabam por ser apelidados por ���revus��� e s��o afastados.��� Em vez de ter quadros competentes, temos um jogo de cadeiras em que l��deres incompetentes fracassam, mas depois s��o realocados em diferentes posi����es no Estado.

Algumas falhas combinam corrup����o e incompet��ncia. O regime tenta influenciar e se afirmar dentro das organiza����es profissionais e sindicatos a fim de controlar as massas. Isso colocou a Ordem dos M��dicos de Angola, que aceitou a hist��ria de que o Dala tinha morrido de doen��as pr��-existentes, e o Sindicato de M��dicos, que culpou a brutalidade da pol��cia, em desacordo sobre a causa da morte de Dala. Como resultado, slogans como ���Fora S��lvia Lutucuta,��� foram ouvidos durante as manifesta����es contra a morte do Dr. S��lvio Dala em Setembro de 2020.

A corrup����o, manifestada na recusa do regime em permitir que a Ordem dos M��dicos de Angola agisse independentemente da influ��ncia do Estado, foi tamb��m vis��vel na forma como o Estado tratou os m��dicos angolanos como classe profissional durante a pandemia. Os m��dicos do Sindicato de M��dicos criticaram a Lutucuta e o Estado por causa das pol��ticas relacionadas com a situa����o do COVID19 que marginalizam os m��dicos angolanos num momento em que os seus conhecimentos eram mais necess��rios. Quando 244 m��dicos cubanos chegaram a Angola para ajudar no combate ao COVID-19 em todo o pa��s criou uma onda de descontentamento entre os m��dicos, visto que Angola tem muitos m��dicos com as mesmas qualifica����es que se encontram desempregados. H�� disparidade salarial entre m��dicos cubanos e angolanos criou mais tens��o: os cubanos recebem sal��rios dez vezes superiores aos angolanos, com os m��dicos cubanos a receberem dez vezes mais do que os angolanos: Este �� um exemplo do compromisso e a ���d��vida de sangue��� que o MPLA tem com Cuba, pa��s com o qual estabeleceu rela����es privilegiadas nas ��reas da defesa, seguran��a, educa����o e sa��de, depois de as tropas cubanas terem ajudado a garantir a independ��ncia de Angola em nome do MPLA.

Os enfermeiros, maior grupo de profissionais de sa��de do pa��s, cogitaram fazer greve em fevereiro deste ano para exigir melhores condi����es de biosseguran��a nas unidades de sa��de e 13�� m��s de abono salarial. Em meio �� pandemia, m��dicos e enfermeiras e as organiza����es profissionais que os representam ficam pendurados pela incapacidade e incompet��ncia do regime.

As dificuldades de governan��a associadas com a pandemia, revelam problemas mais duradouros.�� O regime nunca olhou para a sa��de p��blica como um investimento potencial e um elemento de poder. Diante disso, a elite pol��tica, a come��ar pelo pr��prio presidente, obt��m seus servi��os m��dicos em cl��nicas privadas e, muitas vezes, fora do pa��s.

Ol��vio N’kilumbu e professor ao Universidade de Oscar Ribas, polit��logo, analista pol��tico e consultor.

Nighttime in Nairobi

President Records Ltd present Matata, London, 1971, photo: unknown, (c) President Records Ltd.

President Records Ltd present Matata, London, 1971, photo: unknown, (c) President Records Ltd. As a child, one of my favorite Soukous songs was “Nairobi Night” by the Soukous Stars. I loved the rolling bassline, percussive guitars, and the language-neutral singalong chorus. I knew little about nightlife, only from parties my parents threw in their basement on occasions like New Years Eve, but seeing the title, perhaps I imagined what a Nairobi night might feel like thousands of miles away. So it is in the spirit of that imagining that I present the next episode of Africa Is a Country Radio, where we continue our look at club culture across the African continent, and take a visit to Nairobi.

In this episode I chat with Bill Odidi, a journalist and radio programmer who participated in the Ten Cities book project about his essay on clubbing culture in the Kenyan capital. I ask, questions like “What defines a club in a city full of mobile soundsystem matatus?” “How does club culture reflect the character of the city?” “What do you think of sheng drill music in?” and more. We of course listen to some both classic and cutting edge tune out of one of East Africa’s most vibrant and diverse music scenes. Take a listen on Worldwide FM, and follow us on Mixcloud to catch up on all the episodes.

July 28, 2021

Postfeminism is only for wealthy Nigerian women

Deola RTW, NY Fashion Week 2014. Image credit James Nova via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Deola RTW, NY Fashion Week 2014. Image credit James Nova via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Simidele Dosekun���s new book, Fashioning Postfeminism: Spectacular Femininity and Transnational Culture, is a book about young, class-privileged women in Lagos who wear���to a spectacular degree and in spectacular combination���weaves and wigs, false eyelashes and false nails, heavy and flawless makeup, and the highest of heels. This ���spectacularly feminine style,��� as she calls it, has been growing in visibility and popularity in Nigeria for about the last 15 years. It dominates Nigerian popular media, from Nollywood stars and other celebrities, to glossy women���s magazines, to the looks curated by sites like bellanaija and other accounts on Nigerian social media. Unsurprisingly, it is also the style of brides and other women at the most ���fabulous��� Nigerian weddings. Based on interviews with 18 women in Lagos who dress broadly in this style, Fashioning Postfeminism is concerned with the accompanying senses of identity and self being fashioned and communicated. The book argues that the women see themselves in ���postfeminist��� terms: as ���already empowered��� and even ���self-empowering.��� Donning a style of dress that promises self-confidence by way of normative feminine beauty, these women see themselves as individually beyond the need for feminism as collective politics and struggle.

In the following conversation, Grace Adeniyi-Ogunyankin and Simidele Dosekun discuss and reflect upon Dosekun���s book. Their conversation comes out of a wider panel discussion at the 2021 Lagos Studies Association Conference.

Grace Adeniyi-OgunyankinI found Fashioning Postfeminism exciting because it moves away from the predominant scholarship on low-income African women who supposedly ���need to be empowered.��� We rarely read about ultra-privileged African women who are ���already empowered,��� particularly through consumerism and its accompanied ���freedoms and choices.��� I am, however, intrigued by the implicit suggestion in the book that ���postfeminism is only for wealthy Nigerian women.��� I wonder about the non-wealthy women in Nigeria���s new economy who are also influenced by transnational culture and engage in practices of the spectacular feminine, and about the women we might call the ���empowered almost,��� those who embody the aspirational and imagine their future selves as ���fully empowered.��� Where might they come in?

Simidele DosekunWhen I started the project 10 years ago, there was an uninterrogated assumption in the literature that postfeminist notions that women can ���have it all��� and no longer need feminism were addressed pretty much exclusively to privileged white women in the global north. My counterargument in the book is that postfeminism travels across borders of various kinds, but I didn���t want to slip into making an argument that the culture is just up for grabs by any or all women everywhere. I do think that, ultimately, it is quite elitist. This is not to say that, in a place like Nigeria, only wealthy women consume postfeminist media, for example, or engage in the kind of spectacular fashion and beauty practice with which my book is concerned. But I do think to have or at least claim a sense of self as ���already empowered,��� as happily unencumbered by power relations, requires a fair bit of material privilege. My argument about class is about who can claim postfeminism in the present; I very much agree with you that there are questions about aspirational futures that also need to be considered.

Grace Adeniyi-OgunyankinWhile reading, I also kept on wondering about elite queer and trans Lagosian women, who do not appear to be part of your research demography. Is it possible for some of them to be postfeminist subjects? Which technologies of feminine beauty do they employ and what do these technologies promise for them? How do they navigate transnational culture vis-��-vis the negotiation of local power and culture in Nigeria?

Simidele DosekunAbsolutely. I think queer and trans women can and do also ���do��� postfeminism, both in terms of the kinds of technologies of feminine beauty in question in the book, and the accompanying claims and mentalities about feminine empowerment that I heard from the cis women whom I interviewed. Indeed, there are also cisgendered men too, both queer and not, taking up the beauty technologies���in Nigeria, media personality Denrele Edun comes to mind, for instance. As to what such beauty technologies and practices promise and mean for different kinds of gendered subjects who embrace them, I cannot presume to answer, as I don���t believe we can read subjectivity from style. To answer, we���d precisely have to hear from the actors in question.

Grace Adeniyi-OgunyankinThe women in the book clearly articulated their desire not to be misrecognized as ���runs girls��� [Nigerian slang for women who engage in transactional sexual/romantic relationships]. They also embraced sexual propriety and respectability when it came to distancing themselves from transactional sex. I am curious about the possibility of considering this embrace of sexual propriety and respectability as ���cruel attachments��� too.

Simidele DosekunI was a little surprised at the relative sexual conservatism that the participants expressed, to be honest. I suspect one reason was that I did not always bring up questions of sex and sexuality in the most fluid way, so, most likely, I introduced some awkwardness around these themes. It���s useful to think of women���s attachment to ���sexual respectability��� in terms of ���cruel attachments,��� as promising much but ending up hurting us, so thanks for the suggestion. I think women the world over know that, at the end of the day, ���respectability��� will not protect us from possible abuse and violence of all kinds, and, moreover, that the line between the putatively respectable and disrespectable is incredibly fine and capricious.

Grace Adeniyi-OgunyankinMy favorite topic was your insightful and nuanced analysis of weaves and wigs as ���unhappy technologies��� of spectacular femininity, using Sara Ahmed���s definition of unhappy objects as those that ���embody the persistence of histories that cannot be wished away by happiness.��� You point out that the women���s postfeminist claims and affects, for instance, could not resolve or even mask the melancholy and painful histories of their hair choices and stories.

Simidele DosekunI really wanted to make a case in the book for moving past reading or seeing black women in weaves and wigs as ���self-hating,��� ���wanting to be white,��� and so on. I find this far too simplistic, and even disrespectful; it pathologizes black women, and even if it is voiced in the name of black nationalism, in a roundabout way it continues to affirm and naturalize white supremacy. Sara Ahmed���s concept of the ���unhappy��� helped me make an argument for keeping white supremacy in view without making it the whole story. I do not explore the following question in the book���I had it in mind for a postdoctoral project that never happened���but I���d say that we also need to think about and conceptualize the fact that the so-called ���human hair��� that black women are wearing and desiring is ���Indian hair,��� ���Vietnamese hair,��� and so on. What are the race���and other���politics of this? It is very complicated.

Grace Adeniyi-OgunyankinOverall, you argue for a politics of the unfashionable in a book about fashion by urging us to look beyond the market/consumerism for liberation. In a moment when global white supremacist capitalist patriarchy pervades our daily lives, you insist that we be ���killjoys,��� circumvent ���happiness,��� zero in on uncomfortable questions around justice, and magnify the need for liberation from structural inequalities.

Simidele DosekunYes, I am suspicious of sexy and fashionable and commodified feminisms! This is not to say that I think feminism is, or feminists are, sexless, frumpy, humorless, and so on, which are of course well-worn stereotypes. I just think that we need to resist strongly the co-optation and hollowing out of feminist and other progressive politics by the market���the reduction of feminist politics into T-shirt slogans, say. I also believe firmly in the right to and value of anger so long as there are things in the world that make us angry!

What is whiteness in North Africa?

Photo by Xingtu, via Flickr CC.

Photo by Xingtu, via Flickr CC. On the second day of Ramadan, in early May of 2019, the Doha-based television channel Libya al-Ahrar aired an episode of its hidden camera program in which the show���s star prankster blackens her face, adopts mocking versions of a ���Sudanese��� accent and attire, and then traps strangers in an elevator with two monkeys that she insistently describes as her children. Only a few days later, the show repeated the blackface gag. This time, the actor asked the waiter in a Lebanese restaurant in Libya to read the menu line by line with her as she responded with outrageous incomprehension, confusing things like ���juice box��� and exclaiming, ���You have dog juice?!��� The elevator episode circulated on social media platforms with some condemnation but remains available on YouTube; the restaurant episode seemingly aired without hesitation. The ostensible comedy in these depictions relies on anti-black racism and, in so doing, functions to ratify discourses of white supremacy. Like blackface performance practices elsewhere, these depictions reveal much more about those creating and consuming the racist portrayals than about those supposedly being portrayed. In these Libyan hidden camera clips and elsewhere in North African popular culture, who are the ���white��� Arabic speakers that these racist depictions aim to elevate? What is whiteness in this context?

How should we think about these questions���about whiteness and race���in North Africa? The answer requires consideration of Islam, slavery, indigeneity, Arabness, the Sahara, and colonial legacies in the region. It also requires accepting two claims.�� First, there is analytical purchase to thinking whiteness in and through North Africa, even while this formation of whiteness only partially overlaps with the more dominant formations of whiteness attendant to and produced by European colonialism. Second, through a range of discourses and performances in both scholarship and popular culture, blackness is repeatedly constructed as if it were non-indigenous to North Africa. Ironically, this latter discursive practice is among many which, as Jemima Pierre has argued, ���actually work to impede race analysis about the African continent (beyond southern Africa), entrapping us into a kind of race-blindness.��� The North versus Sub-Saharan Africa divide, Pierre continues, ���has shaped Africanist scholarship to the point that this distinction is often assumed rather than interrogated.��� This naturalized division is racialized: colonial scholars painted light-skinned people of the southern Mediterranean as ���closer��� to Europe both geographically and in terms of civilization. By continuing to describe North Africa as inevitably distinct from ���Black Africa,��� we not only reinscribe this violent hierarchy, but we also prevent ourselves from seeing racialization as processual and dynamic. In so doing, we miss the opportunity to understand North and Saharan African spaces as sites for the ongoing production of race and white supremacy.

To offer a starting place: in a 1967 article, historian Leon Carl Brown described North Africa as ���the great border zone where white ends meeting the area where black begins������where, he contended, ���native whites and native blacks have confronted each other since the beginning of history.��� Brown���s essay goes on to incorporate a number of the key factors that I identify here, and compellingly illuminates a period of early postcolonial African hope and its emerging challenges by describing the ambivalent Pan-Africanism of Gamal Abdel Nasser and others in the 1950s and 1960s. But this formulation of a ���great border zone��� aptly illustrates the racialization of naturalized geography which has long characterized colonial (and some earlier) descriptions of northern Africa. When we take for granted the idea that the Sahara constitutes a natural border, we reify a logic that posits racial whiteness as indigenous to North Africa, racial Arabness as contributing to the maintenance of that whiteness, and racial blackness as non-indigenous. Amazigh (���Berber���) indigeneity is here simultaneously configured as racially white and erased insofar as indigenous modes of thinking difference are domesticated.

Here, and in my research on contemporary Libya, I am invested in understanding whiteness not as a static ontology but as ���a problematic, or an analytical perspective: that is, a way of formulating questions about social relations.��� Thinking in terms of both conceptual and embodied movement, I am especially interested in ���the ways that whiteness seduces and rewards, becoming the subject of fantasy and desire,��� and I agree with Steve Garner that ���the best way to understand whiteness is to think both relationally and comparatively.��� In Garner���s work and in more recent scholarship, this has primarily meant taking the critical study of whiteness beyond its ���home��� of the United States and into Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. But what happens when we take this study from settler colonial contexts into the postcolony? To turn again to Pierre, ���how could any postcolonial society not be structured by its legacy of race and racialization���especially when colonialism was, in the most ideological, political, and practical way, racialized rule? How do we, in fact, analyze the persistence of white (and racialized Arab) privilege in postcolonial spaces?���

Whiteness is both productive and the product of affective force, and while it moves, it moves us. As Sara Ahmed has argued, ���Whiteness could be described as an ongoing and un-finished history, which orientates bodies in specific directions, affecting how they ���take up��� space.��� My argument here is not that (some) North Africans are in any stable sense white or have access to the top rungs of global hierarchies of white supremacy. Rather, I am interested in the array of things that formations of whiteness do and enable in the contexts of northern Africa.

Whiteness shapes both how bodies can take up space and what spaces are available to whom. As Ahmed writes,

If the world is made white, then the body-at-home is one that can inhabit whiteness. As Fanon���s work shows, after all, bodies are shaped by histories of colonialism, which makes the world ���white���, a world that is inherited, or which is already given before the point of an individual���s arrival. This is the familiar world, the world of whiteness, as a world we know implicitly. Colonialism makes the world ���white���, which is of course a world ���ready��� for certain kinds of bodies, as a world that puts certain objects within their reach.

Ahmed is not describing North Africa here (even while a trace of North Africa haunts this passage with Fanon). But the ���bodies-at-home��� in North Africa are most often those that can inhabit whiteness. As I suggest above, both Western scholarship and local discursive practices make North African spaces white. In this way, whiteness in North Africa takes on valences of ���Europeanness��� as a colonial remnant, while it also operates in another register, as ���our own��� whiteness, a color-coded language of virtue and status. This includes but is not reducible to white-as-Western because a local articulation of whiteness can be valorized at the same time that Westernness is rejected. This local articulation of whiteness is bound up in histories that stretch back at least as far as the seventh-century Arab invasion of North Africa.

Blackness is produced as nonindigenous to North Africa through a racial imaginary that relies on the histories of racialized enslavement that have characterized the region. To offer an incomplete list, the slave trade was officially outlawed in Tunisia in 1841, Algeria in 1848, Libya in 1856, Egypt in 1887, Morocco in 1923, and Mauritania in 1980.

In each of these contexts, abolition involved a complex interplay of colonial politics with regional and local discourses and economic forces; in most cases, the practice continued for decades after its legal prohibition. The slave trades that moved across the Sahara, the Red Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea involved captives of a range of geographic and ethnic backgrounds, and, as a number of historians have shown, frequently were justified through moral-legal formations that marked non-Muslims as enslavable. Yet historians have also illustrated how enslavement came to specifically express a conception of blackness in these regions, producing a racialized distinction. John Hunwick, for example, argued that from the sixteenth century onward in the ���Mediterranean Islamic world,��� blackness became associated with slavery by virtue of the high proportion of enslaved black people. Similarly, and pushing back against a generation of scholarship which described ���Islamic slavery��� as a relatively ���benign��� institution, Chouki El Hamel more recently argued ���that relying solely on Islamic ideology as a crucial key to explain social relations, particularly in the history of black slavery in the Muslim world, yields an inaccurate historical record of the people, institutions, and social practices of slavery in the Arab world.��� More broadly, in the context of North Africa, the production of a category of blackness linked to enslavement and arrival also enabled the production of a formation of whiteness linked to Arabness, superiority, and normative belonging.��

The legal and social histories of Arab attempts to variously claim and disavow whiteness in the United States have received substantive scholarly attention. These studies have illustrated how nineteenth and early twentieth-century legal claims to whiteness by Arab immigrants were structured by the particular racial and legal regimes of their time. Primarily Christian immigrants who had come from greater Syria litigated claims to their whiteness as the route to naturalization in a period of Asian exclusion. This history is particular and contingent; that is to say, it might, in different circumstances, have been otherwise.

Even while describing a US context, such studies are relevant for conceptualizing whiteness in North Africa insofar as they enable us to observe some key aspects of the overlapping problematics at play between these two geopolitical sites, as well as the limitations of this overlap. Histories of Arab racialization in the US inflect globally circulating racial discourses. Further, even in a more contemporary US political context, one in which many Arab Americans do not actively seek access to whiteness, we find some popular and even scholarly articulations of Arabness that specifically occlude blackness. One finds this occlusion in, for example, discussions of shifting Arab American inclusion in whiteness, which leave out black Arab Americans for whom whiteness has never been accessible.

Historians have also traced notions of Arabness as whiteness in other geopolitical and historical contexts. Ibn Battuta, for example, wrote in the mid-fourteenth century of ���whites��� as he traveled through the West African Sahel and southern Sahara; for him, these included Arabs and Arabophone North Africans, but not Berbers, whose ���distance and foreignness from the normative cultural practices of the Arab Muslim World��� precluded whiteness. El Hamel demonstrates that this formulation of ���white��� Arabness may have included people of a variety of family lineages, so long as they could claim ���one drop��� of (paternal) ���Arab blood.��� Precolonial Arab and Arabophone social formations did not necessarily value whiteness in terms of color and in terms of Europeanness in the same way that these come to be valued through empire, but Arabophone anti-blackness is evident long before the European colonial period. In postcolonial North Africa, these intertwined legacies have enabled outcomes like that described by Afifa Ltifi in Bourguiba���s Tunisia, where colorblind family name policies constructed a normative whiteness and ���reproduced the patron client relationships that bound slave and master���s descendants.��� Across contexts, ���Arab��� proximity to and approximation of whiteness has historically been predicated on anti-blackness���on the ability to define themselves in opposition to a black Other.

Colonial representations in scholarship and popular media which utilize an oppositional framework for understanding ���North Africa��� as distinct from ���Sub-Saharan Africa��� suggest a racialized boundary of naturalized geography in the desert. A wave of scholarship in recent decades has attempted to alter this paradigm, describing the desert as a ���bridge��� and honing in on Saharan and ���trans-Saharan��� histories and lifeworlds. Some of this work has illuminated the racialization that the Arabophone states of the Mediterranean coast continue to extend to the descendants of enslaved peoples captured in West Africa and other places. This racialization, as I describe above, posits blackness as a referent of enslavement which sticks to an array of bodies, including those of more recent migrants and indigenous black North Africans. One result of this is the carving away of indigeneity from black North Africans. By linking blackness to enslavement, this discourse in both scholarship and popular practice dispossesses black North Africans of a natal claim to North Africa (and, in some instances, Arab identity) apart from a history of arrival. If, as Sara Ahmed has argued, ���whiteness becomes worldly through the noticeability of the arrival of some bodies more than others,��� then this is a distortion that contributes to the (re)production of whiteness in/as North Africa.

One of the quotidian ways these racial geopolitics are maintained is through the common third-person descriptor of black people in northern Africa as ���Africans��� distinct from an unspecified (unmarked) norm. This discursive practice also produces a tension-filled and ambivalent whiteness, one with which Algerian diasporic activist Houria Bouteldja recently danced in a polemic on ���whites, Jews, and us.��� She writes, ���Fifty years after the independence movements, North Africa is the one subduing its own citizens and black Africans. I was going to say ���my African brothers.��� But I no longer dare to, now that I have admitted my crime. Farewell Bandung.��� In ���no longer daring��� to claim fraternal kinship, Bouteldja acknowledges the violence of North African anti-blackness. Yet, even then, in describing ���North Africa��� as ���subduing its own citizens and black Africans,��� she also seems to suggest that the end of the colonially constructed state system could end North African anti-blackness. But the latter runs far deeper than the postcolonial state. North African unmarked whiteness itself holds up the ���and��� in her phrase, ���its own citizens and black Africans,��� as though these categories are or have ever been mutually exclusive.

If whiteness needs maintenance to persist and racializations of all sorts are continually unfolding, popular culture is a privileged site in which this work occurs. In film, performance, visual art, and literature, representations mark bodies in and out of normative community, naturalize racialized language, entrench stereotypical figurations, and reify social hierarchies. Recent years have seen greater public controversies appear surrounding racist representations of black characters in North African (and other Arab) popular culture. Scholarship investigating race and popular culture in/and North Africa is relatively emerging, but has tackled a range of themes and questions surrounding nationalism, empire, alterity, and aesthetics across performance forms in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Continued work is needed. As of yet, scholars have more vigorously illustrated and theorized anti-black discourses, practices, and representations in popular culture than they have asked how these works produce and maintain whiteness.

Describing blackface performance in early twentieth-century Egypt, Eve Troutt Powell wrote of songs and plays in which ���Nubian��� (���berberi���) and ���Sudanese��� characters enacted Egyptian anticolonial, nationalist desires. As she explained, ���In the absence of the ���right��� kind of Sudanese political allies���that is, those who would proclaim a desire for the unity of the Nile Valley���the Egyptian artists and writers deeply involved in the promulgation of the nationalist message “made up their own Sudanese.��� The Libyan hidden camera skits with which I opened this writing, and which drew directly from this long history of Egyptian caricatures of Sudanese people, illustrate the continued need to interrogate the racial work that blackface and other performance practices do in North African contexts. Through violently erasing the Others they purport to represent, both a century ago and in the recent past these practices have served to construct their performers��� and audiences��� visions of themselves. They utilize anti-black tropes to produce whiteness in their performers, audiences, and cultural milieus. In this way, they join myriad other discursive and performative practices that repeatedly construct blackness as not indigenous to North Africa. It is imperative that we do not stop at noting the anti-black racism that we rightly see in these, but rather go on additionally to theorize the racial and spatial whiteness that these practices enable and uphold.

What is Black Conservatism in South Africa

The podcaster, Sihle Ngobese, known as ���Big Daddy Liberty��� and a well known South African black conservative (Youtube screen grab).

The podcaster, Sihle Ngobese, known as ���Big Daddy Liberty��� and a well known South African black conservative (Youtube screen grab). The last time South Africans had serious intellectual discussions about black conservatism was in the late 1980s. Various academics and researchers concentrated specifically on the figure of Chief Gatsha Buthelezi and his Inkatha movement as emblematic of black conservatism in the country. Those who identified Inkatha as a black conservative movement include historians Jabulani (Mzala) Nxumalo (1988), Gerhard Mar�� and Georgina Hamilton (1987), as well as political scientist Shireen Hassim (1988). Hassim in particular honed in specifically on the gendered implications of Buthelezi���s conservatism as a black politician.

Of particular relevance for reviving discussions of black conservatism now is an argument that Hassim makes in relation to Inkatha. She focuses specifically on its centralization of an expressly patriarchal and hierarchical invocation of the traditionalist Zulu family, mobilized in defense of Inkatha���s anti-labor and anti-sanctions or divestment politics at the time.��

Buthelezi���s sociopolitical conservatism stood in stark contrast to the politics of black liberation���which he claimed nonetheless. In fact, we take it for granted that in the apartheid era, to be a black politician and public intellectual meant being situated someplace on the left-liberal spectrum. However, a figure such as Buthelezi put that assumption into question, along with a large number of black male intellectuals who were part of the apartheid government���s 1980s reforms which focused on creating a new black middle class with a stake in preserving rather than overthrowing this system. Fast-forward to the postapartheid period and 21st-century South Africa, and we can observe how the fruits of the 1980s project begin to take prominent shape in the greater push for expanding the middle class���especially the black middle class.��

It should be acknowledged, however, that to speak of a homogenous black middle class in South Africa is problematic, especially given the lack of clarity as to how one measures middle class identity (as academics like Ronel Burger, Cindy Lee Steenekamp, Servaas van der Berg, Asmus Zoch,��Geoffrey Modisha, and Roger Southall show). Despite such warnings, the black middle class constitutes an important identity to which we should pay attention in studies of modern-day South Africa.��

Sociologist Roger Southall sees value in focusing on the black middle class in South Africa; ���while the black middle class may indeed play an important role in furthering democracy,��� he writes, ���its political orientations and behavior cannot be assumed to be inherently progressive.��� In other words, as part of a global class that has been labeled as preoccupied with consumption and status, Southall notes that the middle class���s significance in contemporary South Africa ���revolves overwhelmingly around the extent and consequences of black upward social mobility.��� Consequently, the interests of this class are likely to align with conservative modes of self-preservation rather than plebeian politics. To this end, middle-class buy-in to conservative right economic discourse does not need much defending���the issue of diversity of interests within this class notwithstanding.

This means that despite its rich history of left politics, South Africa is not shielded from the rise of the type of black conservatism ripping through the United States (but also England, Canada, and parts of northern Europe). In the United States, the names of Condoleezza Rice, Clarence Thomas, and Ben Carson are just a few of the personalities associated with black conservatism. In South Africa, Herman Mashaba (the former Democratic Alliance mayor of Johannesburg) and Sihle Ngobese (a podcaster known as ���Big Daddy Liberty���) are certainly newer reflections of this phenomenon in postapartheid South Africa.��

Writing on Ngobese, for example, political scientist Christopher McMichael describes ���a black online media personality who styles himself on black American political operatives like Candace Owens [identified with Donald Trump and the American far right] reinforcing white conservatives��� beliefs that structural racism does not exist because a black person says so and that they are under siege from creeping socialism.��� What Ngobese and, in particular, Mashaba represent (as the most vocal and public faces of the rising black conservatism) is a view that is in line with traditional New Right discourse, namely that ���the decline of values such as patience, hard work, deferred gratification and self-reliance have resulted in the high crime rates, the increasing number of unwed mothers, and the relatively uncompetitive academic performances of black youth,��� as black American philosopher Cornel West described in 1986.��

What this alignment means is that the black South African middle class���s attack on programs aimed at redress, undertaken in pursuit of ���middle-class respectability based on merit rather than politics,����� can easily sideline the poor among them and further the Afrophobia against Africans from elsewhere on the continent. For example, Herman Mashaba, while mayor of Johannesburg, promoted these ideas under the guise of protecting South Africa from so-called criminal elements.��

What reflects as middle-class pursuit in the postapartheid context is more akin to conservative New Right ideology (complete with its moral regeneration campaign) than it is to the liberal narrative of the pursuit of equality and freedom for all. In the case of South Africa, it is arguable that the latest national election results in 2019 reflect a general trend towards such middle-class economic conservatism.��

In fact, in the 2019 South African general elections, the Inkatha Freedom Party drew support nationally, as well as in the two major provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal (where, at the time of writing this piece, pro-Zuma protests in response to his imprisonment were underway). Furthermore, the newly formed church-based party, the African Transformation Movement (ATM), with its ���South Africans First��� motto, managed to secure an eighth position in the elections nationally on its first try. ATM claims to follow the philosophies of humanism and ubuntu, but a closer reading of its policies reveals that ATM believes in the return of capital punishment, building a ���society founded on Divine-based Values,��� promoting ���Moral Regeneration,��� and reinvigorating the role of traditional leadership in governance. As is clear from this list, ATM espouses ideas commonly found in conservative and New Right discourse as imported from the United States. In fact, in expanding the reach of ATM���s discourse beyond the black block, we can observe that its discourse aligns very well with the Democratic Alliance���s conservative stances and policies on immigration, crime, and rights of sexual minorities. This points to a broader conservative alliance between the white right-centered bloc and the black middle class. Interestingly enough, ATM���s economic principles are more in line with the Economic Freedom Fighters��� nationalization of the economy, including the reserve (or central) Bank. It remains to be seen how it balances this ���socialist��� economic outlook with its moral conservatism.��

Another conservative Christian organization also garnered enough votes for a sixth place finish in the 2019 elections: the African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP), founded in 1993. While its electoral performance has basically remained flat, this party has nonetheless remained competitive in all elections since 1994, failing to acquire any national seats in only one election (1994). Its highly positive 2019 elections performance indicates its continued relevance, especially in light of the argument of this piece regarding the rise of black conservatism. In fact, the ACDP performed well in the three major provinces of Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape.��

Led by Reverend Kenneth Moshoe, the ACDP promises a fresh start based on Christian and family values: in its own words, ���The ACDP promotes, upholds and defends Christian family values����� Moreover, the ACDP proclaims: ���We adhere to a moral philosophy that is based upon the Word of God, and measure the interpretation of our policies against the prerequisites of biblical standards.��� More importantly, the ACDP economic policy foregrounds traditional right economic principles. It does so by advocating for a commitment to ���reducing government debt and spending; job creation and economic growth through an open-market policy with as little government interference as possible; becoming competitive in the global economy and global markets; lowering inflation; state enterprises operating in open competition with private providers; and doing away with complicated tax forms, laws and expensive monitoring.��� In other words, there is much conservatism to be found in the specifically evangelical Christian orientation of this organization, including the fact of their black constituency.

Although the focus here is only on a few organizations, the point is to illustrate the very eclectic nature of what constitutes black conservatism in present-day South Africa. This eclecticism means that there seem to be two distinct conservative currents at work: one that is more traditional and the other that is a more populist-styled current. The first current, embodied by Herman Mashaba and Sihle Ngobese, embraces free-market economics and self-improvement ethics. The second, more populist-styled current is embodied by parties or movements like ATM (which does embrace some outwardly left-wing policies like nationalization).��

This raises questions of viability and appeal. One, which of these strains of black conservatism is most viable in the current political context? Two, can the strains be further demarcated along the urban black middle class versus working class line? In fact, in making a case for why the 2019 elections mattered and doing so in a way that highlights the key aspect of black conservatism, we can note how the rise of this aspect is tied to a number of challenges usually associated with conservative backlash. Both conservative strains address aspects of the challenges related to the economy, education, morality, national identity, and sexuality. This raises the question of how our democracy will respond to these challenges, a question that leaves open the possibility that South African politics remain fertile ground for new orientations, albeit mainly conservatively black in my estimation. To which eish is not a sufficient response from the left.

What is Black Conservatism in South Africa?

The podcaster, Sihle Ngobese, known as ���Big Daddy Liberty��� and a well known South African black conservative (Youtube screen grab).

The podcaster, Sihle Ngobese, known as ���Big Daddy Liberty��� and a well known South African black conservative (Youtube screen grab). The last time South Africans had serious intellectual discussions about black conservatism was in the late 1980s. Various academics and researchers concentrated specifically on the figure of Chief Gatsha Buthelezi and his Inkatha movement as emblematic of black conservatism in the country. Those who identified Inkatha as a black conservative movement include historians Jabulani (Mzala) Nxumalo (1988), Gerhard Mar�� and Georgina Hamilton (1987), as well as political scientist Shireen Hassim (1988). Hassim in particular honed in specifically on the gendered implications of Buthelezi���s conservatism as a black politician.

Of particular relevance for reviving discussions of black conservatism now is an argument that Hassim makes in relation to Inkatha. She focuses specifically on its centralization of an expressly patriarchal and hierarchical invocation of the traditionalist Zulu family, mobilized in defense of Inkatha���s anti-labor and anti-sanctions or divestment politics at the time.��

Buthelezi���s sociopolitical conservatism stood in stark contrast to the politics of black liberation���which he claimed nonetheless. In fact, we take it for granted that in the apartheid era, to be a black politician and public intellectual meant being situated someplace on the left-liberal spectrum. However, a figure such as Buthelezi put that assumption into question, along with a large number of black male intellectuals who were part of the apartheid government���s 1980s reforms which focused on creating a new black middle class with a stake in preserving rather than overthrowing this system. Fast-forward to the postapartheid period and 21st-century South Africa, and we can observe how the fruits of the 1980s project begin to take prominent shape in the greater push for expanding the middle class���especially the black middle class.��

It should be acknowledged, however, that to speak of a homogenous black middle class in South Africa is problematic, especially given the lack of clarity as to how one measures middle class identity (as academics like Ronel Burger, Cindy Lee Steenekamp, Servaas van der Berg, Asmus Zoch,��Geoffrey Modisha, and Roger Southall show). Despite such warnings, the black middle class constitutes an important identity to which we should pay attention in studies of modern-day South Africa.��

Sociologist Roger Southall sees value in focusing on the black middle class in South Africa; ���while the black middle class may indeed play an important role in furthering democracy,��� he writes, ���its political orientations and behavior cannot be assumed to be inherently progressive.��� In other words, as part of a global class that has been labeled as preoccupied with consumption and status, Southall notes that the middle class���s significance in contemporary South Africa ���revolves overwhelmingly around the extent and consequences of black upward social mobility.��� Consequently, the interests of this class are likely to align with conservative modes of self-preservation rather than plebeian politics. To this end, middle-class buy-in to conservative right economic discourse does not need much defending���the issue of diversity of interests within this class notwithstanding.

This means that despite its rich history of left politics, South Africa is not shielded from the rise of the type of black conservatism ripping through the United States (but also England, Canada, and parts of northern Europe). In the United States, the names of Condoleezza Rice, Clarence Thomas, and Ben Carson are just a few of the personalities associated with black conservatism. In South Africa, Herman Mashaba (the former Democratic Alliance mayor of Johannesburg) and Sihle Ngobese (a podcaster known as ���Big Daddy Liberty���) are certainly newer reflections of this phenomenon in postapartheid South Africa.��

Writing on Ngobese, for example, political scientist Christopher McMichael describes ���a black online media personality who styles himself on black American political operatives like Candace Owens [identified with Donald Trump and the American far right] reinforcing white conservatives��� beliefs that structural racism does not exist because a black person says so and that they are under siege from creeping socialism.��� What Ngobese and, in particular, Mashaba represent (as the most vocal and public faces of the rising black conservatism) is a view that is in line with traditional New Right discourse, namely that ���the decline of values such as patience, hard work, deferred gratification and self-reliance have resulted in the high crime rates, the increasing number of unwed mothers, and the relatively uncompetitive academic performances of black youth,��� as black American philosopher Cornel West described in 1986.��

What this alignment means is that the black South African middle class���s attack on programs aimed at redress, undertaken in pursuit of ���middle-class respectability based on merit rather than politics,����� can easily sideline the poor among them and further the Afrophobia against Africans from elsewhere on the continent. For example, Herman Mashaba, while mayor of Johannesburg, promoted these ideas under the guise of protecting South Africa from so-called criminal elements.��

What reflects as middle-class pursuit in the postapartheid context is more akin to conservative New Right ideology (complete with its moral regeneration campaign) than it is to the liberal narrative of the pursuit of equality and freedom for all. In the case of South Africa, it is arguable that the latest national election results in 2019 reflect a general trend towards such middle-class economic conservatism.��

In fact, in the 2019 South African general elections, the Inkatha Freedom Party drew support nationally, as well as in the two major provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal (where, at the time of writing this piece, pro-Zuma protests in response to his imprisonment were underway). Furthermore, the newly formed church-based party, the African Transformation Movement (ATM), with its ���South Africans First��� motto, managed to secure an eighth position in the elections nationally on its first try. ATM claims to follow the philosophies of humanism and ubuntu, but a closer reading of its policies reveals that ATM believes in the return of capital punishment, building a ���society founded on Divine-based Values,��� promoting ���Moral Regeneration,��� and reinvigorating the role of traditional leadership in governance. As is clear from this list, ATM espouses ideas commonly found in conservative and New Right discourse as imported from the United States. In fact, in expanding the reach of ATM���s discourse beyond the black block, we can observe that its discourse aligns very well with the Democratic Alliance���s conservative stances and policies on immigration, crime, and rights of sexual minorities. This points to a broader conservative alliance between the white right-centered bloc and the black middle class. Interestingly enough, ATM���s economic principles are more in line with the Economic Freedom Fighters��� nationalization of the economy, including the reserve (or central) Bank. It remains to be seen how it balances this ���socialist��� economic outlook with its moral conservatism.��

Another conservative Christian organization also garnered enough votes for a sixth place finish in the 2019 elections: the African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP), founded in 1993. While its electoral performance has basically remained flat, this party has nonetheless remained competitive in all elections since 1994, failing to acquire any national seats in only one election (1994). Its highly positive 2019 elections performance indicates its continued relevance, especially in light of the argument of this piece regarding the rise of black conservatism. In fact, the ACDP performed well in the three major provinces of Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape.��

Led by Reverend Kenneth Moshoe, the ACDP promises a fresh start based on Christian and family values: in its own words, ���The ACDP promotes, upholds and defends Christian family values����� Moreover, the ACDP proclaims: ���We adhere to a moral philosophy that is based upon the Word of God, and measure the interpretation of our policies against the prerequisites of biblical standards.��� More importantly, the ACDP economic policy foregrounds traditional right economic principles. It does so by advocating for a commitment to ���reducing government debt and spending; job creation and economic growth through an open-market policy with as little government interference as possible; becoming competitive in the global economy and global markets; lowering inflation; state enterprises operating in open competition with private providers; and doing away with complicated tax forms, laws and expensive monitoring.��� In other words, there is much conservatism to be found in the specifically evangelical Christian orientation of this organization, including the fact of their black constituency.

Although the focus here is only on a few organizations, the point is to illustrate the very eclectic nature of what constitutes black conservatism in present-day South Africa. This eclecticism means that there seem to be two distinct conservative currents at work: one that is more traditional and the other that is a more populist-styled current. The first current, embodied by Herman Mashaba and Sihle Ngobese, embraces free-market economics and self-improvement ethics. The second, more populist-styled current is embodied by parties or movements like ATM (which does embrace some outwardly left-wing policies like nationalization).��

This raises questions of viability and appeal. One, which of these strains of black conservatism is most viable in the current political context? Two, can the strains be further demarcated along the urban black middle class versus working class line? In fact, in making a case for why the 2019 elections mattered and doing so in a way that highlights the key aspect of black conservatism, we can note how the rise of this aspect is tied to a number of challenges usually associated with conservative backlash. Both conservative strains address aspects of the challenges related to the economy, education, morality, national identity, and sexuality. This raises the question of how our democracy will respond to these challenges, a question that leaves open the possibility that South African politics remain fertile ground for new orientations, albeit mainly conservatively black in my estimation. To which eish is not a sufficient response from the left.

July 27, 2021

The longest shadow

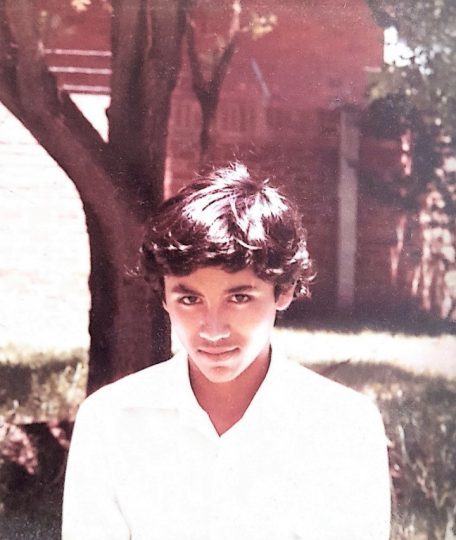

The author outside St Cyprian's Cathedral in 1981 at the age of 13.

The author outside St Cyprian's Cathedral in 1981 at the age of 13. ��� South African writer Sol Plaatje in his 1930 novel, Mhudi���I am going to leave this place while the leaving is good.”

However hard I try, I find myself being unable to write anything else before I have written this. I am in the midst of writing a fourth novel, but the cogs of my creativity have ground to a halt, the exit routes that lead the imagination beyond this wretched piece are sealed. All that remains is this blank screen onto which these hands are forced into writing this miserable story. Perhaps, once it is written, I will be able to turn my mind to other things; this will be a case of writing to free my mind. As James Baldwin wrote: ���Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.���

I was born in Johannesburg in April 1968, under the sign of Aries, and during the Chinese year of the monkey. I am told that this is a formidable astrological alignment, but I don���t set much store by such things. When I was two weeks old, my parents moved to Cape Town, the first of many journeys that would typify my nomadic life, a life of incurable wanderlust, a life lived on the move: running away from the past, running away from myself.

I have many memories from my early years in Cape Town. I remember the layout of the house we lived in. I remember the bulbous reflective kettle in the kitchen that distorted the shape of my face when I peered into it. I remember the kindergarten I went to, and that yellow crayons were my favorite because they had a luminous glow.

I remember shaving off my eyebrows because I didn���t want to pose for photographs at a birthday party my parents had organized. I remember us one day driving behind a huge lorry packed with cars. That was when I learned the word ���pantechnicon.��� I remember an older cousin from Johannesburg coming to live with us while he was studying at the University of the Western Cape, and the big, heavy books he was always buried in. I remember the little girl I played with at the end of the corridor, only to be told years later that she had actually died in the house before we moved in. I remember falling ill and always being surrounded by doctors. I didn���t like that, but their strange necklaces fascinated me. That was when I learned the word ���stethoscope.��� I remember the old ladies who appeared when the doctors had left. They strung garlands of garlic around my neck, plastered my chest with cabbage leaves, and rubbed my forehead with strong-smelling potions. That was when I learned the words ���Hollandse medisyne.��� But no matter how many doctors and old women came to my bedside, I did not recover.

I remember being told that the cold and wet Cape Town winters were not good for me, and that we would be moving to Kimberley where the climate was drier. The move to Kimberley is the first journey I recall. My mother and I went by plane because I was too ill to travel by road. That was my first of countless flights. I still have the navy blue tailored jacket my parents dressed me in for the flight, and the ticket with the old South African Airways flying springbok emblem. All these memories, and I was only five.

If I could go back in time, I would save that little boy from boarding that flight. The move to Kimberley would prove to be disastrous for my family life and for me. Small towns cast the longest shadows.

I started school in Kimberley in 1974. The next twelve years���the years before my matriculation from secondary school in 1985���would be a torment for me. I hated school because of all the bullying. I was called a pretty boy with flowing hair, but neither adjective was intended as a compliment. The first bullying incident I remember was in grade one, when an older girl with bushy hair pulled a fistful of hair from my head and said, ���You have girls��� hair. Give it to me.��� I was chosen last for sports teams and tormented for playing the piano. The torment escalated when word got out that I was taking typing lessons on my mother���s typewriter.

Kimberley is a diamond mining city and the capital of the Northern Cape province. Cecil John Rhodes established De Beers Consolidated Mines there in 1888. The ���Diamond City��� is situated in the center of the country, close to the border between the Northern Cape and the Free State.�� It is 950 kilometers from Cape Town, 480 from Johannesburg, and 700 from Port Elizabeth and East London. I know these routes well because few school holidays passed without us traveling to visit family in those cities. I lived for those journeys, because life in Kimberley was dull and drab; everybody was obsessed with the pursuit of small-town bourgeois respectability. There was nothing like the thrill of my mother stepping on the accelerator once we had reached the open road and looking back to see the lights of Kimberley disappear on the horizon behind us. But when at home, we did our best to entertain ourselves. As children, we baked mud cakes in the garden on Saturday mornings. I can still smell that wet red soil, the red soil for which Kimberley is famous.

During these earthy games, we kept a lookout for diamonds because there were always stories circulating of people finding diamonds while gardening. Like many Kimberlites, we got to know the Kimberley Mine Museum like the back of our hands and the story of the Open mine by rote. The biggest hole in the world started as a hillock on a farm, which belonged to the De Beers brothers. Digging for diamonds there commenced in 1871 and ended in 1914. During that time, 22 million tons of earth were excavated, yielding 2,700 kilograms of diamonds. All this digging left a crater 200 meters deep with a circumference of two kilometers. It also left high mine dumps of blue-grey kimberlite around the city. A favorite pastime was to go tobogganing down those dumps on old conveyor belts. We became proficient with the diamond mining process: from deep level explosions, to excavation, to filtering on grease belts to which the diamonds stuck, to weighing, to sorting, and finally to cutting. Sorting happened in Harry Oppenheimer House, one of Kimberley���s two tallest buildings. It rises over fourteen floors with windows on only the south-facing side. These dark-tinted windows are angled precisely to let in just the right amount of light to facilitate the sorting process. Access was strictly curtailed. We would stare up at those angled windows from down below and imagine the mysterious process of sorting the world���s finest gemstones. Many of my classmates dreamed of working up there when they finished school. Not me. My only dream was to get out.

But it is another famous Kimberley landmark that passes the longest shadow over my life, ���longest��� being a poignant word here because it houses the longest nave in South Africa���St. Cyprian���s Cathedral. While I am a Muslim, I am from the kind of religiously mixed family that typifies my hybrid community in South Africa, a family in which Hindus married Christians and Christians married Muslims. If South Africa were to split along sectarian lines, families like mine would be torn apart. St. Cyprian���s was where my maternal family worshiped. Growing up, I spent a lot of time there because I was an altar boy and a chorister. Being an altar boy meant serving at Mass four or five times a week. Being a chorister meant choir practice twice a week and singing at Mass two or three times a week���more often on big religious festivals like Christmas and Easter. In a monotonous city where nothing special ever happened, being associated with superlatives like the biggest hole in the world and the longest church in the country brought some kind of sad kudos. I say that this landmark has cast the longest shadow over my life because it is at St. Cyprian���s Cathedral where I was sexually abused by priests from the age of ten.

I first came out about the child sexual abuse I experienced at St. Cyprian���s in 2018, after Archbishop Desmond Tutu resigned as ambassador to Oxfam following the sex abuse scandal that rocked the international aid agency. I made my statement then to point out that while Tutu was being critical of Oxfam, he never fully addressed the systematic and institutionalized sexual abuse happening inside his own organization, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa. In my initial statement, I did not divulge the names of the priests who abused me. Neither did I go into the details of the abuse and its full impact on my life. In fact, I turned down subsequent requests for interviews resulting from that first statement. Even at the point of coming out, I still acted on one of the most common impulses the abused feels towards their abusers���to protect them.

At the time, I thought that my initial coming out would be the end of the story. I was wrong, firstly because I now realize that coming out is not the end of the conversation, but the beginning, and secondly because three years after my statement, the abuse I experienced in the Church continues in different forms. While child sexual abuse in cities like Cape Town and Johannesburg is relatively well documented, it remains comparatively underreported in provincial cities like Kimberley, where recourse is often curtailed by concerns like, ���What will people say?��� So let me proceed with the details now���by no means to discredit a faith, but rather to challenge an institution. I hope that speaking openly will help other survivors to realize that they are not alone either, even if they choose to remain silent. We tell our stories when we are ready.

My first abuser arrived at St. Cyprian���s in 1978, the year I turned ten. His name was Roy Snyman. The touching started almost immediately. Snyman was a divisive man, who at the height of apartheid insisted on displaying the old South African flag in the cathedral. As a boy, I never understood why a bigoted white man would be attracted to a skinny black boy like me, but now I have come to realize that his abuse was not attraction. It was the typically racist assertion of white power and authority over the black body; his intention was not to flatter, but to humiliate. When Snyman shook my hand in greeting, he would drop our tightly clenched hands to my groin, rub my intimate parts, and ask, ���How is the tiger in the tank growing?��� This happened whether we were dressed in civilian clothes or religious robes. It happened whenever he could snatch a moment with me alone: in the dark corners of the cathedral, in his office in the cathedral, or in his house on the cathedral grounds.

When I was sent with messages to his office, he would beckon me to stand behind his desk. Remaining seated, he would rub my intimate parts and ask his usual question. On one occasion, I was sent to deliver a message to his house. I found him in the TV room, watching the weather forecast. He gestured at me to sit on the armrest of his armchair and told me to wait, because the weather was important���all the while fondling my intimate parts. Snyman was a man full of wit, but also prone to ugly outbursts of anger. He could have people in stitches, but could also make them tremble with fear. With time, I stopped laughing at his jokes, but I never moved on from my fear of him.

When Snyman���s death in Port Elizabeth was reported on September 15, 2020, I was filled with a strange mixture of confusing emotions for which I have still not found the words. In the months since Snyman���s death, I have felt stuck, unable to leave the house, and unable to focus on anything much for any length of time. So one day I set about researching all the adults who were in positions of authority while I was a child at St. Cyprian���s. That was when I made a shocking discovery: the cathedral choirmaster, Nicolaas Bester, who had in the intervening years emigrated to Tasmania, was imprisoned there on two occasions for sexually abusing one of his fifteen-year-old students. Bester, who is now a convicted sex offender, described the abuse he had inflicted on his student as ���awesome.���

My second abuser arrived in Kimberley from Wales in 1981, the year I turned thirteen. His name is Keith Thomas. I still remember the first time I saw him; it was at a baptism service in the cathedral. I also remember his first visit to our house during his rounds to introduce himself to congregants of the parish. While I have no recollection of Snyman visiting our home���he was more given to socializing with white parishioners���this visit from Thomas, a handsome Welshman, was a big deal; it felt as though God himself had walked through the door. The special cups and saucers were brought out, and the table decked from side to side with canap��s and snacks. When the visit ended, Thomas asked me to walk him to his car, which he had parked on the next street. I remember him commenting on the size of the lemons on our neighbors��� lemon tree during our walk. Today, it strikes me as strange that he did not park outside our house, especially as we had an ample driveway. But at the time, the bullied boy felt like the chosen one.

While Snyman was an opportunist, Thomas played the long game. First, there were increasing visits to our house until, over the years, he became a family friend who was always invited to special family occasions. My parents��� marriage was in decline and Thomas was their marriage counselor. Then there were invitations to join the youth club, which met at his house on the cathedral grounds on Friday nights. Looking back, I see that this is how child sexual abusers frequently operate���by winning the trust of the family. Youth club was supposed to be a safe space, keeping young people of the parish away from clubs, substances and underage sex, all of which were rampant in Kimberley. With the deterioration of my parents��� marriage during the course of 1982 and 1983 and my increasingly fraught relationship with my father, the invitations extended to spending the night after youth club so that I didn���t have to go home to face my father. It wasn���t long before I was spending the whole weekend at Thomas���s house, only going home after Evensong on Sunday nights. Over the years, I was becoming increasingly isolated from my family, while often being selected for special roles in the church. For instance, in preparation for Bishop George Swartz���s enthronement as Bishop of Kimberley and Kuruman in 1983, I was the boy selected to clean and polish his silver crozier. It took me two days working in Thomas���s house to remove all the tarnish.

Even though the sexual abuse started almost immediately, with Thomas coming into my bed every night I stayed over, I did not understand it as abuse. I longed for the weekends when I could get out of our troubled family home and spend time with him. My bed was in the corner in a room at the end of the corridor. Thomas would come into it during the night. I would press myself into the wall, but he would press up behind me, rubbing himself up against the back of me while trying to pull down my pajamas to gain access to my intimate parts. That was when I learned the word ���frigid,��� because that was what Thomas called me when I resisted him.

Today, I���m still trying to understand what was worse, the escalating sexual abuse or the increasing psychological abuse that followed. Thomas would lose his temper with me whenever I spent my free time with my family, my cousins, or my friends. I started to feel guilty for neglecting him, so I withdrew from those relationships to spend all my time with him.

I also remember that Thomas���s shelves were lined with books���that was where I read The Diary of Anne Frank for the first time. There were afternoon drives into the countryside during which Thomas let me change the gears on the car while he guided my hand with his; there were times when I listened to Mozart at full volume while conducting the imaginary orchestra in my mind.

Sometimes, I used his key to enter the cathedral when nobody was there. Alone in that magnificent building, I would spend Saturday and Sunday afternoons by myself playing the beautiful grand piano and the splendid pipe organ. My favorite piece to play on the piano was Beethoven���s ���Moonlight��� Sonata; on the organ, his 5th Symphony. Even the food Thomas served was a novelty: I had never eaten baked beans on toast. But most of all, there was love, or so I thought. I loved Thomas as a father; after my parent���s marriage ended, I fantasized about him marrying my mother. (My teenage fantasy overlooked the prohibition of such a union by South Africa���s Immorality Act, which banned sexual relations between white people and people of other races.) In fact, it would be many years before I realized that the sexual acts Thomas inflicted on me were also prohibited, and that what he had done was criminal. I simply had no notion that priests could do any wrong. At the time, I believed that he loved me, so when the time came for me to go to university, my elation at finally being able to leave Kimberley was tempered with sadness at having to leave him behind.

My child sexual abuse took place during the political abuse of the grand structure of apartheid. As my political awareness developed at university, I started to grapple with my position as a man who was racially abused by the apartheid state and a child who had been sexually abused at the hands of white priests. My story is not an exception. Neither does it belong to the past; child sexual abuse in South Africa remains pervasive. According to the Children���s Institute at the University of Cape Town, one in three South African children are sexually abused before the age of eighteen. In my experience, the reasons survivors of child sexual abuse are reluctant to speak about their abuse are complex and many: as children, they don���t have the language to express what is happening; they are afraid no one will believe them; they worry that they have done something wrong; they fear retaliation from their abuser; they expect that they will be punished; they become entrapped in a ring of isolation their abuser weaves around them; they are afraid for the reputations of their families; and they internalize the shame, all of which leads them to choose suffering in silence, as I had done for forty years.

The consequences of child sexual abuse endure into adulthood, long after the abuse has stopped. I live with bipolar disorder. I have grappled my whole life with the symptoms of my condition, which are well-documented: excessive spending, substance abuse, eating disorders, extreme highs during which one feels invincible, debilitating lows during which one cannot stir from bed, suicidal thoughts, sexual promiscuity, self-harm, and risky behavior. Such behavior started in early adolescence and continued all through my adult life, until three potentially fatal events, which happened in quick succession in 2017, finally forced home the realization that my life had become unmanageable and that if I didn���t seek help, I would end up dead. Today, I manage my condition with counseling, medication, vipassana meditation, exercise, and the unconditional support of my loved ones.

But that has not stopped the abuse I experience from the Church, which has now taken on other forms. In April 2018, I gave the names of the priests who abused me to a senior bishop of the Anglican Church in South Africa. Since then, I am not aware of any conclusive action taken against Snyman or Thomas by the Church; I only know that Snyman died a priest in robes in September 2020. In September 2019, after no substantive action relating to my case on the part of the Church, I initiated legal action against Snyman, Thomas, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa, and the Office of the Archbishop of Cape Town. In retaliation, the Church demanded that I pay $40,000 as surety for their legal fees because I am not a resident in South Africa. In December 2020, the courts threw out that demand, opening the way for us to move forward with legal proceedings, which are now pending. That Snyman died before facing trial is perhaps part of my confusion surrounding his death. The rest is for the courts to decide, but I have little faith in the Anglican Communion Safe Church Network given the Church���s lack of transparency and sincerity in its handling of my own abuse case. And whenever I hear Beethoven���s ���Moonlight��� Sonata and 5th Symphony, I am overcome with feelings of utter loss and total foreboding.

As altar boys, we were given medals depicting a phoenix rising from the ashes. Like all writers, one is frequently asked about why one writes. In the past, a typical response was: Because I feel I have to. But I have never fully understood why I have felt so compelled to write���until now. It is only through writing this that I have come to understand the drive behind the compulsion, and it turns out to be quite basic: I write to stay alive. The pen is now my phoenix, and if I am unable to write another thing, at least I have written this, and it has kept me living. Writing has brought me to a greater understanding of what happened to me when I was a child. Now, as a man, I stand on the threshold of my most important journey���from the shadows and into the sunlight.

July 26, 2021

On failed states and the pitfalls of Western commentary

Photo by Emmanuel Ikwuegbu on Unsplash