Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 122

July 24, 2021

When the spirits of the ancestors call you back

Olympic Summer Games 1968 opening. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Olympic Summer Games 1968 opening. Image via Wikimedia Commons. On October 16, 1968, John Carlos and Tommie Smith dared to defy the International and US Olympic Committees by bringing political activism to the podium. They wore only black socks, raised their black-gloved fists above their heads, and looked down as the US national anthem played. It was an insanely audacious act, but far less reprehensible than the injustices Black people had faced for centuries in the US���police brutality, discrimination in housing, schooling, voting and employment. John Carlos and Tommie Smith were expelled from the US team and sent home.

Two days later, on October 18, Lee Evans, a 21-year-old athlete from Madera, California, shattered the 400-meter world record in 43.86 seconds, officially breaking the 44-second barrier for the first time. His record stood for 20 years. On the podium, in spite of the death threats he had received the day before, he took off his shoes and wore a black beret, a symbol of the Black Power movement that he had purchased weeks before in Denver while training at altitude for the thin air of Mexico City. He knew what ���his race��� meant. The next day, as part of the US 4×400 relay team of four African-Americans, he smashed another world record that would hold for 24 years. Lee Evans, the athletic legend was born. The seminal Mexico moment was the culmination of a rare blend of determination, skill, curiosity, and consciousness. On the eve of the Tokyo Summer Olympics, just two months after his passing on May 19, 2021, we remember him for the lessons he has taught the world.

Evans��� parents were Louisiana sharecroppers. In the 1940s, they moved to the rural San Joaquin Valley and continued farm work. Evans attended schools with few Black and Mexican-American students. He did not see where he belonged in American society until the 6th grade, when he learned from a history book that Black Americans primarily descended from West Africans. As he recounted in the keynote speech he delivered at the 2005 Ohio University Sports Africa conference in Athens, Ohio, ���The spirits of my ancestors were calling me back. I am going to go back to Africa for the African who was taken away. I felt that spirit in me.��� It was a consequential spiritual self-discovery.

The times preceding the October 1968 Olympics were tumultuous. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated in April and June respectively. The same year, Steve Biko created SASO (South African Student Organization), which led to the Black Consciousness movement. The 1960s were a foundational decade for Black people in sports and in life. Those ebullient moments of Black nationalism resonated not only in the red hills of Georgia, the Rockies, and the mountains of Tennessee and New York. They sounded stridently around the world. Activists rallied to ban South Africa from international sport because of apartheid. Zimbabweans were living under an oppressive White Minority Rule. Namibia was a de facto colony of South Africa. In Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and Sao Tome e Principe ruled a combination of settler colonialism, racism, and a dictatorship straight from Portugal at the heart of democratic Western Europe.

Events in Africa clearly sharpened Evans��� activism. In 1967, aged 20, he attended a track competition in the UK, where he encountered anti-Apartheid South African poet and activist Dennis Brutus. Evans accepted his offer to attend a South African resistance meeting, recalling: ���I went with them to this meeting. Before the meeting started, they stood up, they said a prayer for the brothers who had fallen in the war���I didn���t even know there was a war going on in South Africa. This was part of my education about South Africa.��� Evans stayed in touch with South African activists over the years and frequently dissuaded American athletes and coaches from working in Apartheid South Africa. This informed his approach to fighting racism in the US.

Against the backdrop of US domestic and international upheaval and before the Mexico City games, Evans along with Tommie Smith and Harry Edwards created the Olympic Project for Human Rights. No Black coach was on the US Olympic Track and Field staff and the project called for a Black boycott of the 1968 Olympics to protest racism and injustice both inside and outside the Games. Evans��� calls for inclusion and diversity earned him death threats. As he related, ���It wasn���t funny when someone threatened your life just for speaking your mind in a so-called free country.��� The committee���s demands went unmet, but they took their protest to the games. Still too few Black people hold high-profile positions of power in sports, despite some contemporary progress. Yet, the fact that Evans took a stand on these issues more than 53 years ago highlights how difficult the journey is.

Before the Olympics, Evans was exploring avenues to make deeper connections with Africa. ���When I made the Olympics I was a Black Nationalist, I���m proud of my people and we are going to win a lot of medals for America. But most of all I was looking forward to meeting African athletes.��� A fervent pan-Africanist, Evans lamented the poor performance of West African nations in track events. Understanding the deep connections between Black Americans and West Africa, Evans stated, ���We African Americans were representing West Africa at the time.���

Lee Evans spent most of his post-Olympic career working in Africa, directing national athletics programs in six countries on the continent. Evans first coached in Nigeria in 1976 with the goal of preparing the national team of that country for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. Ultimately Nigeria, as well as two-dozen African countries and Iraq boycotted the games because they refused to compete alongside New Zealand, which had embarked on a rugby tour of Apartheid South Africa. As famed former Nigerian footballer Segun Odegbami noted, Evans made it his life���s mission to develop athletics in Africa, particularly West Africa.

Several lessons can be drawn from Evans��� remarkable life. First, sports is not solely business. Beyond country, talent, glory, and medals that only a few win, athletes cannot just run in their lanes. They must engage in the struggles of their times and people. The nearly exclusive focus on results and money in sport normalizes inequality and follows neoliberal principles to the detriment of peoples��� lives.

Evans��� humility should be a model for how coaches approach their craft. He noted that the quality and commitment of African coaches needed improving. ���Some of the coaches wanted to be the Minister of Sports looking down on the track instead of being down on the track doing the work itself. I didn���t mind getting down on my hands and knees showing them how to do that.��� Evans considered his people at every step of his success.

Lee Evans returned to his ancestral land to live out his life. A Yoruba proverb says ���No matter how far the stream flows, it never forgets its source.��� When the great Muhammad Ali journeyed to Zaire to fight George Foreman in 1974, Ali���s hype man Bundini Brown rapped, ���The king is going home to get his throne. From the root to the fruit!���

The fruits of Evans��� career nourished his efforts back home, Nigeria, where he is buried.

Matthew Kirwin’s views don���t represent the US governmentJuly 23, 2021

Abnormal rugby in an abnormal society

Cape Town Stadium, where all three tests between the British and Irish Lions and the Springboks will be played without fans. Photo: Warrenski, via Flickr CC.

Cape Town Stadium, where all three tests between the British and Irish Lions and the Springboks will be played without fans. Photo: Warrenski, via Flickr CC. A friend of mine asked me recently why I had not objected to the current British and Irish Lions tour of South Africa. He was of course referring to the petition and letter of objection���objecting to South Africa���s bid to host the 2023 Rugby World Cup���that I had sent to World Rugby (the body that runs international test rugby) and every single affiliated rugby body I could get contact details for. In the end, the SA Rugby (SARU) bid was unsuccessful, and France got the nod for the 2023 tournament.

I did not bother too much with the British and Irish Lions tour because I strongly suspected that SA Rugby would require the same leeway in terms of game time as they had needed for the 2020 Rugby Championship���and that they would therefore call off the tour, especially in the face of the COVID-19 scourge. I was wrong: the excuses and flip-flopping by the world champions during the 2020 season had passed their sell-by date, and the Springboks were ready to show the world why they are world champions.

This year���2021���is also a significant year in the Springbok calendar, as it celebrates 130 years of international test rugby. Ninety of those years, however, totally excluded ���black��� intrusion, until Errol Tobias gave ���legitimacy��� to the bok jersey in 1981 (during a tour of New Zealand and the United States). It is also the 40th anniversary of the last time the Springboks played the New Zealand M��ori. The Polynesian tribe from Aotearoa visited South Africa in 1993���4 as participants in the M-Net Nite series and never toured the Republic of South Africa again. Ironically, the puritan souls at SARU dismissed the team as being ���racially selected,��� an idea and policy so abhorrent that no matches between the New Zealand M��ori and South African sides may take place under SARU���s watch or with their sanction. At the time, Jurie Roux, the chief executive officer of SARU, said that the Springboks do not play against teams selected on ���race.��� Instead, SARU merely honors the racist history and legacy of ���the most valuable brand in sports.�����

The Springboks are shielded by the broad and wide shadow of Nelson Mandela, who, together with the ANC (and with the aid of the National Party), sold South Africa���s social structures for the right to host the 1995 Rugby World Cup and for ���black��� South Africans��� freedom to proudly wear the distasteful green and gold mantle. All social structures in sports were completely destroyed, simultaneously obliterating the lines of communication to communities affected by poverty. Under apartheid, the localized structures in sport, arts, culture, education, and politics directed the energies of the poor into more positive���albeit revolutionary���pursuits. Sports formed an integral part of the political educational framework���there were no childish illusions of ���keeping politics out of sports.���

Rassie Erasmus, coach of the 2019 world championship team (and now SARU director) and his world champions toured South Africa in 2019, after his impassioned speech about the ���real issues facing the country��� inspired the Springboks to their third World Cup triumph. The very issues he swore about���and cried tearfully about in the Disney-esque ���documentary��� series Chasing the Sun���have not disappeared. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has drawn back the veil that Springbok achievements on the field have deflected attention away from for so long.��

The social conditions that separate South Africans into camps of hope and hopelessness are the very conditions that favor the Springboks currently and historically. In sporting terms, things have improved for the sporting brand of racism and apartheid, and have regressed to the point of nonexistence for the sporting structures that opposed apartheid through sports. The sham of including ���black��� rugby icons in the Springbok rugby museum had a very short life, because it tried to knock ���black��� pegs into green holes. This sham was preceded by a period of ���honoring��� the victims of apartheid with the colours of apartheid and racism, through the awarding of Springbok colors to them. In the spirit of the Errol Tobias era, this was a process of legitimizing the Springbok brand. With Siya Kolisi as the face of this appalling brand, nobody will dare probe the uncomfortable dark corners of bok history, especially now that JZ (not that one, the other one) has bought into the mighty bokke through endorsement deals with prominent players.

Now, as smoke billows from Kwazulu Natal and Gauteng, the British and Irish Lions continue their tradition of ignoring the acrid odor, focusing on scrums and line-out drills while their opponents smash scrum machines and treadmills. Tackling bags, kicking tees, and heated jacuzzis dull the moral senses of an elite group of people who play for prestige and money and nothing else. And the flags that are waving in support fan the flames of a rapidly unfolding disaster.

I did not bother objecting to the British and Irish Lions tour because I knew that it would expose the system for what it is. There can be no normal sports in an abnormal society. Even if Rassie cries those Hollywood tears over social conditions, those tears are for the rugby Oscars���not for the people.

This country is in very deep trouble, and it is bound into the system of inequality that people celebrate through the Springboks.

I told you so.

July 21, 2021

Decolonize this

Photo by Abdulaziz Mohammed on Unsplash

Photo by Abdulaziz Mohammed on Unsplash Republished from the latest issue of menelique.

There is no doubt that a sensational story and a captivating image can win the day if one wants to send a very complicated political message to the world. In many disciplines, academics and journalists have relied on the power of the story and the image to explain a complex idea. In journalism, media reporting, and popular culture in particular, these stories and images can fall in the trap of sexism, racism, and other exclusionary politics.

Take for instance the powerful story and image of the young Sudanese woman, Alaa Salah, who became the icon of the recent youth uprising in Sudan. The uprising toppled the authoritarian regime of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir on April 11, 2019. Al-Bashir ruled the country for 30 years with strict conservative religious laws that led to more war and fragmentation. ��One day before he was ousted, Alaa appeared in the New York Times’ fashion section wearing a Sudanese white-body wrap (Taub) and Nubian-style jewelry.��She was surrounded by protesters taking snapshots from their smartphones as she recited a resistance poem from atop a standing vehicle. The image went viral in both national and international news media, dubbing her the Nubian queen (kandaka) of the revolution and presenting her as��a youthful face��of a new Sudan.

It is insincere to deny the power of Alaa���s story and image and the purpose they served at that particular moment. Her story came at a moment when the media was distracted by other major global events and many people had forgotten about Sudan after the separation of the South in July 2011.

Despite lack of international attention, however,�� the youth of Sudan continued to protest in many parts of the country. Their protests culminated in the uprising that began on December 19, 2018 and continued until April 11, 2019. In fact, the protest is ongoing. Protesters hope to avoid the fate of October 1964 and April 1985 revolutions in Sudan, which have been co-opted by military coup d�����tats after short democratic periods. They also hope to avoid the co-optation of the Arab Spring movements in the Middle East and North Africa.

Therefore, it is fair to say that Alaa���s representation helped raise global awareness about the Sudanese uprising. However,��it fails to answer important feminist questions:��How are women, especially women from the global South, and women of color in the diaspora being represented in global media and in popular culture?��And what are the pros and cons of such representations?

Feminists have long contested reductionist representations of women in nationalist and internationalist discourses and practices. That is, reducing women and their struggles to mere images, symbols, and stereotypes. Such images abound:��women are often represented as beauty queens and as symbols of fertility.��Other examples include��images of half-naked native women on coins, brands, and art works. Women are also represented as monuments of freedom and liberation, as the image of Alaa obviously suggests. These images often mask women���s national and transnational struggles as workers, farmers, migrants, mothers, and professionals. They also fail to show how women are excluded from real representation in various public spheres.

No wonder Alaa herself was taken aback by the massive response to her image and the many kudos she received, such as being dubbed the gem of the revolution (iqaunat althawra). She said in one interview that there were other women who marched along with her and that there were martyrs who died for the cause of freedom. They should be treated as gems too.

Despite cheering for Alaa, Sudanese feminists also responded to her representation. Some felt uncomfortable with the invocation of��the term Nubian queen (Kandaka). Although the term references their female ancestors��� glorious past���the history of the black Nubian queens who protected their polity from external incursions���it also overshadowed women���s past and present struggles. This is especially true in the post-colonial moment, where the past does not necessarily provide answers for present struggle, nor does it provide clear answers for the future aspirations of diverse groups of women.

Invoking the term Kandaka, therefore, may put women on a pedestal and continue to manipulate, silence, and distract them from their demands for equality and full participation in politics. For instance, during the negotiation process that led to the establishment of the current transitional post-revolutionary government in Sudan, only one woman was represented among the majority men negotiators. Moreover, few women were called upon to fill high level political posts afterwards. In fact, in the third ministerial reconfiguration announced in February 2021, women filled only four posts out of 25 ministerial offices.

Also missing from such representation is Sudanese women���s long history of fighting against oppression during both the colonial and postcolonial time and their successful struggles for the right to vote, to work in public, and to serve as parliamentarians.��Furthermore, there is a genealogy of Sudanese women���s representation in global media that preceded Alaa���s snapshot image. For example, when the Darfur conflict took the media by storm,��then-president George Bush employed stories of Darfurian women to make Darfur part of his political agendas.

French officials also championed the case of the Sudanese woman, Lubna al-Hussein, to mark the place of France in the world:��a beacon of democracy and liberation and�� supporter of the cause of ���oppressed Muslim women��� in Africa and the Middle East. Alas,��the interest in veiled women���s oppression in Africa and the Middle East is championed without reference to the struggle of Muslim and other immigrant women in France and other Western countries.

Of course, this genealogy of liberal narratives disconnects women of color and diaspora women from their local and transnational histories of struggle. We still remember the sexist and racist representations of Muslim women during the Iraq war and after the horrible 911 attack in the United States, when Muslim women were, and still are, targeted because of their regalia.

Stereotypes and representations that exclude certain groups of people because of their gender, skin color, religion, or national affiliation have a deep history that goes back to colonial conquests and the enslavement and racialization of non-western people. These histories live today in new practices of racialization and othering that women of color have been fighting against nationally and internationally.

The recent Black Lives Matter (BLM) activism, for instance, is not but a response to this continuous racial representation that has been rearing its head in the US, and elsewhere, in the form of police brutality and other socio-economic violence against communities of color. The ���#Say Her Name,��� campaign launched in 2014 is an example of a powerful initiative led by women of color to include gender based-violence into the framework of the BLM movement and to bring attention to the increasing police violence against black women who are often represented as hyper-sexual, criminal, and lazy ���welfare queens.���

Negative portrayal of a whole group of people using simplistic representations, images, and stereotypes adds to these exclusionary problems.��Such representations are not new, and they continue to acquire new meanings according to changing political and historical circumstances.

For instance, Asian-American women in the US have been sexualized and racialized as exotic, docile, and subservient subjects for a long time. The current outbreak of COVID 19, however, ��increased the visibility of and violence against Asian-Americans. Bodies of immigrants whether black, brown, or even of those considered ���white-but-not-quite��� Europeans have been subject to scrutiny and regulation and described as bodies ���out of place,��� often associated with disease, immorality, and unruly practices.

Today���s rising prejudiced representations mobilize global activists across different social boundaries and political borders to contest the impact of negative gender and racial stereotypes that continue to affect the lives of diasporas and recent immigrants in the US and elsewhere.

There is nothing wrong with global solidarity.��It is much needed now and more than ever before. But what we also need is a serious focus on how to decolonize these misrepresentations, racial stories, and imageries. Let���s call them EEFO functional representations because they continue to float around, essentializing, exoticizing, fetishizing, and orientalizing women and people of color. These EEFOs still portray ���the other��� as someone living outside history.

To decolonize these functional representations, we first have to situate them in the political histories that enable their production. EEFO functional representations may raise awareness about conflict or oppression in one place like the case of Alaa; they may also deepen sexism, xenophobia, and racism as we saw in the case of immigrant and diaspora women in the US and Europe. The function of these EEFO representations is often exclusionary and deploys the long-lasting effect of colonial histories of subordination and oppression.

So, what is most needed is a historically grounded solidarity; solidarity that pays close attention to the struggle of women and people of color in different locations. Women of color, in particular, have long been fighting multiple forms of oppression. Paying attention to their intersecting local and global histories of struggle requires digging deep beneath the sensational narrative, the racial stereotype, and the powerful snapshot image.

July 20, 2021

In the company of coronavirus

A man gets his temperature checked at the entrance gate of Mpilo Hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe, April 2020. Image credit KB Mpofu (ILO) via Flickr CC.

A man gets his temperature checked at the entrance gate of Mpilo Hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe, April 2020. Image credit KB Mpofu (ILO) via Flickr CC. Just over a year ago, in February 2020, I flew to Nairobi to award the 5th Mabati Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature at a ceremony at the Intercontinental Hotel. While disembarking from the plane, every single passenger had their temperature taken with an infrared thermometer, causing a long, mildly disgruntled queue in a confined space at the arrival gate. We all knew this was because the coronavirus had started to appear outside of China, but we didn���t think there was much risk of contagion at that point. When I flew back to London a few days later, I changed planes in Paris and mingled freely with thousands of passengers from all over the world. On arrival at Heathrow, my temperature was not checked at all. In fact, it took until February 2021���a year later���before the British government restricted entry to the UK and enforced mandatory quarantine on arrival.

I had a similar experience when I flew to Lagos in 2014 for the Ake Festival while Ebola was raging in nearby West African countries; at the time, these countries were struggling to contain the deadly, appallingly contagious virus within their borders. At Murtala Mohammed International Airport in Lagos, all passengers had their temperatures checked, but on my return to London, I only saw a few posters that warned of Ebola in West Africa. Nobody checked where I had come from or whether I had been in contact with anyone who could be infected, even though there was a Liberian writer at the festival in Abeokuta and a Liberian woman being taxed for a bribe in the passport queue in front of me in Lagos. Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone were the three countries affected by this outbreak, the worst in the history of Ebola.

Two weeks after I left Nairobi last year, the chair of the Kiswahili Prize, Mwalimu Abdilatif Abdalla, was told he could not leave Kenya to return home to Germany on March 26. After I left, he had stayed on to go to Mombasa and Tanzania and visit relatives in his village in Kenya. Instead, his return flight was canceled and he was confined to government accommodation for over two weeks. When I asked him on WhatsApp how he was coping, he said that after three years in solitary confinement in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison (1969���1972), he was managing very well. His sense of humor always defies belief! His friends even joked that he could write a quarantine memoir called ���Sauti ya Korona��� (The Voice of Corona), after Sauti ya Dhiki, his prison anthology.

By March 16, 2020, the UK was in lockdown and coronavirus had spread all over the world. I couldn���t help thinking that I had been safer in Africa���and I promptly caught the virus and lost my sense of taste and smell for 10 days. The friend I had probably caught COVID-19 from developed long COVID-19 and was ill for six months, whereas I recovered quickly. It seems this roll of the dice reaction was the same for many people: symptoms varied and doctors struggled with the scale and variety of immune responses. A year later, this coronavirus has realized the fears of a global pandemic precipitated by SARS and dreaded for Ebola; at the time of writing, the world approaches 5 million COVID-19 deaths, with 163 million recoveries among the 178 million recorded cases globally. Notably, the Kenyan death toll is currently under 4,000, and the Nigerian count just over 2,000.

In Veronique Tadjo���s book In The Company of Men (2019), first published in French in 2017, we find a timely reminder of ���the destructive powers of pandemics.��� The book focuses on the Ebola outbreak of 2014, which preceded the COVID-19 pandemic by six years but has been present in parts of Africa since 1976, when it was first discovered in the Democratic Republic of Congo and named after the Ebola River near which it was found. Tadjo has commented that she sees a clear link between Ebola and COVID-19, although they are very different diseases. ���For me,��� she writes, ���the Covid-19 pandemic is a continuation, not a break. It inscribes itself in the same context of climate change and its consequences. Ebola wasn���t a one off and Covid-19 won���t be either.���

Through five sections comprising 16 different points of view, Tadjo presents the impact of the Ebola pandemic from the perspectives of different characters including trees, nurses, those infected, survivors, and the virus itself. For example, in a chapter titled ���The Whispering Tree,��� the narrator declares, ���I am Baobab.��� The choice of the baobab tree���s perspective is unique, telling of Tadjo���s concern with environmental degradation as a key factor in the development of such a deadly virus. Reviewer Simon Gikandi, a Kenyan novelist and scholar, comments that ���Tadjo weaves a story that turns the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa into a parable of what happens when the chain that connects human beings to nature is broken.��� And this is perhaps where we have the most to learn in terms of new ways of seeing the COVID-19 pandemic. As Gikandi remarks, ���In the Company of Men��gives voice to the natural world and mourns the loss of the well-being that existed before the destruction of the environment and the arrival of postmodern pandemics.���

In the context of such questions, I was struck by a recent BBC documentary called Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer, in which David Olusoga and Steven Johnson examine the history of vaccination starting with the rise and eradication of smallpox. They detail how an African man was purchased in 1706 by a Puritan congregation in Boston as a gift for their minister, Cotton Mather, and was ���forced to take on a new name,��� Onesimus, after a slave in the New Testament. When Mather asked whether Onesimus had ever had smallpox���rife in Africa at the time���he replied, ���Yes and no,��� and then described the variolation procedure he had undergone in Africa before his capture. Variolation involved cutting the arm and putting fluid from a smallpox wound onto the cut, creating resistance in the host���s bloodstream without transmitting full-blown smallpox. This practice precedes Jenner���s experiments with cowpox by 90 years and had been present elsewhere in the world since the 1500s. This is a key example of effective preventative medicine that was present in Africa before slavery. And yet, the onset of modern transatlantic slavery is when the destruction of the global environment seems to really begin. With the export of ���valuable commodities��� from Africa, including human beings, there soon followed deforestation, mining, farming, and building projects that formed the foundations of colonialism, western capitalism, the industrial revolution and imperialism. The rapacious nature of this conquest, which ignored indigenous knowledge systems and ways of living in harmony with the environment, also often spread disease, occasionally leading to new discoveries in medicine (which were not acknowledged or credited at the time).

The presenters of the documentary rightly laud the eradication of smallpox in just 18 years (1967���1985) as one of the great achievements of mankind, one which epidemiologist Larry Brilliant called ���the end of an unbroken chain of transmission going all the way back to Rameses V.��� Prior to vaccination efforts, smallpox had been killing 2 million mostly poor people a year, and the subsequent campaign involved the cooperation of 73 countries, including Cold War enemies the US and USSR. As Lucy Mangan writes in her Guardian review, ���We can be so terrible, and we can perform such wonders.��� And it is these wonders that Tadjo brings to our attention by writing In The Company of Men. The containment of the Ebola virus in West Africa in 2014 is due to the combined heroic efforts of people on the ground and the local people who heeded public health messages, attended clinics, separated family members, stopped attending funerals, and got vaccinated.

Tadjo reflects in an interview that ���the Ebola epidemic has a multi-layered dimension. It seemed to me that listening to various voices was the best way to get closer to a form of reality. An incredible number of people were involved in the fight against the virus and I could not bring myself to focus on one voice only.��� Interesting correlations and discoveries were made by zoologists, for example who,

discovered a phenomenon that greatly increases Ebola���s catastrophic impact. When an outbreak is about to happen in a forest region, the virus will leave gruesome traces in the natural environment. It attacks antelopes, deer and rodents, but especially big apes such as chimpanzees … The remains of hundreds of animals are scattered on the ground … Whenever the villagers notice an unusual number of wild animal carcasses, they���ve learned to alert the local authorities at once, since the carcasses signify that an Ebola outbreak among humans is about to happen.

This connection to the rest of the natural world seems crucial to understanding epidemiology itself and answering the question of how these viral mutations arise (e.g., swine flu, bird flu, etc.). This is why we should be paying closer attention to the other (mass) extinctions occurring in this Anthropocene epoch.

Using the voice of the baobab is inventive and useful in establishing a timeless link to the forest and to ancestral points of view. But using the voice of a virus itself is fairly unusual in African literature. Kgebetle Moele was the first South African writer to do this, writing from the point of view of HIV in his novel The Book of the Dead (2012), which I have written about elsewhere. Moele���s HIV is a malevolent, predatory infiltrator of the human body. This infiltrator, once personified, seems to corrupt its host while replicating itself in unsafe sexual encounters, killing hundreds if not thousands of men and women in deliberate acts of aggression. The Ebola virus, on the other hand, is immediately established (in its own words) as less malignant than humans themselves; Tadjo writes of ���man and his incurable, pathological destructiveness.��� Humans are blamed throughout for having destroyed the environment and the natural harmonious link between man and nature. However, this is countered by the assertion of human solidarity as a powerful weapon or antidote. Early on in the book, the nurse welcomes the help of volunteers, saying, ���when I see solidarity, it makes me want to work even harder.��� Even the virus admits that ���I understood that their true power showed itself when they presented a united front.���

Much of Tadjo’s writing, including The Shadow of Imana (2002), articulates what ���cannot be written or heard.��� By writing the voices of the perpetrators and victims of genocide, Tadjo enables us to reach a point of understanding���or, at the very least, consciousness���of what many consider unspeakable. The art of her storytelling lies in this ability to synthesize factual accounts and information first with the lives of real people who lived through the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi, and now with the experiences of those who lived through the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. In the Company of Men works similarly to unveil the voices of the hidden and, most significantly, those of the dead who cannot tell their own stories. Her writing itself is an act of solidarity. If we listen, we can not only empathize���we can learn from these stories. The accounts should also act as a warning, as pandemics will continue to threaten humankind alongside climate change.

Tadjo���s book reminds me of an aspect of��Colson Whitehead���s The Nikel Boys��that I have admired so much���that it is so difficult for a narrator to tell a story when the protagonist is dead. Usually, the telling of the tale gives away the fact that the protagonist has survived, or at least lived long enough to narrate the story, but Whitehead twists the ending of his novel to such an extent that we do hear a tale from the grave, from an impostor. This almost reinvigorated story describes the tragic fate shared by many Nikel Boys, whose identities are now lost. This is what is important about Tadjo���s writing: by including the voices of the dead in��In The Company of Men, she inscribes the lives of those whose pitiful deaths don���t make it into the real story of Ebola (except as death toll statistics). This is what the novelist Maaza Mengiste refers to when she asks, ���What do the living owe to the dead?��� The sheer number of people who died in the Ebola epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic, the HIV/AIDS pandemic: this is what causes us to lose our sense of perspective and our ability to understand the real human cost of each universe that is lost to these deadly diseases.��Mengiste���s further question������What do they owe to the earth, which both protects and punishes?������is one we will have to keep considering while we continue to destroy our earth. Is Tadjo���s Ebola virus right? Is man���s pathological destructiveness incurable? What do we owe the earth? Is there the political will, as there was with smallpox, to vaccinate every human against COVID-19, before it mutates into something far worse?

July 18, 2021

The most humanistic and scientific socialist of our generation

Endsars protesters in Nigeria. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Endsars protesters in Nigeria. Image via Wikimedia Commons. This is an edited version of a speech given by Professor Biodun Jeyifo on the 75th birthday celebration of Edwin Madunagu.

Of all such friends and comrades that I have ever met and worked with very closely both in Nigeria and in other parts of the world, Edwin Madunagu stands out in a group comprising no more than two or three comrades who have been consistent in their intellectual and scholarly activism. He is the most humanistic and scientific socialist of our generation.

It is considered very unusual for a socialist to be both a humanistic and a scientific socialist. Without wishing to oversimplify the complexity of this formulation, which contrasts and pits humanistic and scientific socialists against one another, the implied contrast between them can be framed as the conflict between a socialism of the heart and a socialism of the head, or one based on ���sentiment��� and the other based on ���rigor.��� As a matter of fact, among all Marxists, this categorical distinction between the two putative ���socialisms��� has been enshrined in the supposedly fundamental division between the writings of the ���early Marx��� and the later, ���scientific Marx.��� On this premise, in the writings of the so-called ���early��� Marx, the emphasis of the youthful, revolutionary theoretician was squarely on passionate analyses and denunciations of the generalized alienation, poverty, exploitation, and suffering of the working and non-working poor of Europe and the whole world. But in the writings of the older, more mature, and more ���scientific��� Marx, sentiment and passion gave way to detailed and complex analyses of the objective forces and movements of capitalism, together with the equally objective forces that���irrespective of the subjective desires and inclinations of both oppressors and the oppressed���can be mobilized to bring an end to the terrible state of affairs in the world.

That was and is the received understanding of humanistic and scientific socialism. Though it has largely been revised, it still holds true to this day among many Marxists and socialists. Why is this the case? For me, I start with the elementary but irrefutable observation that to become aware of and concerned about exploitation, oppression, and suffering in the world, you do not need to have read Marx or joined a socialist movement. As a matter of fact, that is how most people in the world become aware of and responsive to terrible conditions of exploitation and suffering in their communities, their nations, and the world. That being the case, ���socialism��� and ���Marxism��� are what we might call secondary or additional elements to the foundational status of either personal and collective experiences of exploitation and suffering, or vicarious and solidaristic identifications with the suffering of others. To use this formulation to get to the nitty-gritty of this tribute to Eddie, permit me to draw on aspects of events and realities that brought Eddie and myself together in our youth and shaped our experiences in the Nigerian Left.

Eddie and I first met as undergraduates at the University of Ibadan, and then again in 1976 upon my return to the country after graduate studies in the US; at the time of our second meeting, we were both still ���beginners��� in Marxism. The Anti-Poverty Movement of Nigeria���which Eddie and others had started and into which I was recruited and became editor of the organization���s magazine, The People���s Cause���was not, strictly speaking, a Marxist organization. The important point is that both of us, having barely started our encounter with Marxism, began what would eventually become our most serious theoretical engagement with Marxism and socialism. There is nothing quite like the exponential growth of knowledge that happens when two or more people grow together, driven by something as elemental as the passion to effectively challenge the scourge of poverty and oppression in the world.

As Eddie and I (and others too) grew in sophisticated knowledge of Marxism and socialism, this passion remained the foundational element in our maturation as Marxists. I will go so far as to argue that we were so driven by this factor that it, and not ���Marxism��� or ���socialism,��� became the yardstick by which we measured the authenticity and reliability of all the comrades we came across and worked with. Eddie in particular is very responsive to this factor, without being inquisitorial about it: what people feel, genuinely feel, about needless human suffering and exploitation matters to him immeasurably.

As much as it may seem counterintuitive to most of the comrades who might be reading this tribute, Eddie���more than any other comrade that I know of in the Nigerian Left���is ready and willing to forgive ignorance of, and even indifference to, ���Marxism��� and ���socialism��� from any comrade with whom he establishes genuine collaboration, as long as they are irreproachably genuine in their opposition to human suffering and exploitation. This particular observation leads me directly to perhaps the most crucial���and at the same time most debatable���aspect of this tribute, which is the place of Marxism and socialism in Eddie���s lifework.

Although he has never deliberately set out to create the image of an inflexible and doctrinaire Marxist, for many in the Nigerian Left, this is the general opinion of Edwin Madunagu. Ironically, in the mid-to-late 70s, epithets like ���romantic,��� ���anarchist,��� and ���Trotskyite��� were hurled at him (and this writer) by the most orthodox individuals and organizations in the Nigerian Left. Given this background, it seems nothing short of a paradox that it is Eddie who has turned out to be the most dedicated and articulate voice and repository of the Marxism and socialism of the historic founders, both for this generation and the generations before.

Eddie writes almost exclusively for the Left in a resolute move that seeks to establish the fact that the Left not only still exists but must be sustained. Though he and I have never explicitly discussed this ���arrangement,��� we have perfectly understood its necessity. To this I can only add that what Eddie brings to Nigeria���s national political discourse is incalculable. If you are among those who claim that Marxism and socialism are no longer relevant in Nigeria, even in the face of their resurgence in many parts of the world, all you have to do is read Eddie���s periodic writings in The Guardian; he is undeniably one of the most enlightening columnists on the crises facing Nigeria, Africa, and the world at the present time.

As I think of Eddie���s lifework in relation to Marxists and socialists of the present and past, I think of the well-known African proverb which states that ���when an old man or woman dies, it is a whole library that dies with him or her.��� Of course, this is a tribute to a still living, still intellectually vibrant comrade and long, long may this continue to be so! But it is Eddie���s great achievement to be the uncontested repository and archivist of the heritage of Marxism and socialism in our country. Thus, I can report here that as far back as the mid-70s, Eddie and I began to plan for the need to produce ���information��� and ���documentation��� on the struggles, victories, and defeats of the Left in our country���a major aspect of our work.

I think I can reasonably claim to have met the ���information��� quotient of this self-assigned task. Thus, to Eddie has fallen the far more daunting task of ���documentation.��� The first���and perhaps only���free peoples��� library in Africa was established in Calabar by Eddie and his wife, Bene Madunagu. Sadly, that library has closed down due to many factors, chief of which was lack of funds to keep it going. However, what is left of the library is not rubble, and it is not ashes: it is the largest collection of the papers, memorabilia, and published and unpublished writings of past and living generations of the Nigerian Left. This collection comprises leaders of the working class movement, academic socialists and Marxists, women���s organizations, and student and youth movements.

Knowing my friend and comrade very well, I can imagine his surprise at this tribute, surprise that he is being showered with praise for the work of a lifetime which he could not but carry out���which, indeed, he often feels is incomplete. To this, my response is this: Eddie, who else but me can and will say it: that you will never know the number of our youths who look up to you! You have garnered and also planted many seeds. Indeed, your life���s work is like a granary���for those of the present, coeval generations as well as for those who will come hereafter.

One last thing, Eddie, that I have always wanted to say to you over the decades, but which I somehow never brought myself to say: Would you please try to show the humanist side of your socialism more openly, more publicly than you tend to do? You see, all our friends to whom I have tried to reveal this side of your revolutionary subjectivity and identity have always told me that it is nonexistent, that I am making it up!

July 16, 2021

What is the value of pan-Africanism for psychology?

A monument for those killed in the Soweto Uprising of 1976. Photo: April Killingsworth, via Flickr CC.

A monument for those killed in the Soweto Uprising of 1976. Photo: April Killingsworth, via Flickr CC. This post is part of a limited series,��Psychiatry Beyond Fanon. It is published once a week and explores the history and politics of psychology in Africa. It is edited by Matt Heaton, historian from Virginia Tech with contributions from Heaton and Victor Makanjuola (Psychiatrist at the University Hospital, Ibadan), Katie Kilroy- Marac (Anthropology at the University of Toronto), Ursula Read (Anthropology, King���s College, University of London), Ana Vinea (Anthropology and Asian Studies at UNC Chapel Hill), Shose Kessi (Psychology at the University of Cape Town) and Sloan Mahone (History at Oxford).

In 2019, the journal Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, published an article, ���Age- and education-related effects on cognitive functioning in Colored South African women.��� The findings of the study claimed that low cognitive functioning in ���coloured��� women (what is understood as mixed race in South Africa) had something to do with ���race��� and socio-demographic factors. The study was widely condemned for its epistemological and methodological flaws and subsequently swiftly retracted by the journal editors. Nearly one year later, another article, drawing on attitudes research, a strong tradition in mainstream psychology, became the subject of popular concern. ���Why are black South African students less likely to consider studying biological sciences?��� published in 2020 by the South African Journal of Science, the flagship journal of the Academy of Science of South Africa, makes findings based on ���race��� as an explanatory factor for students��� study choices at university.

Both incidents highlight how much South African universities have yet to decolonize. For psychologists, this has meant revisiting questions about the relevance of the discipline in the afterlives of slavery, colonialism, and apartheid and about what psychology can contribute to improving our understanding of humans. We know, for instance, that psychology and psychologists have been complicit in scientifically ���proving��� racial and gendered hierarchies with the effect of legitimizing colonization and apartheid. Why then should we continue to think of psychology as useful?

For me, it is not about the survival of psychology as a discipline, but rather about how psychologists can and should become advocates for African and African feminist critiques of academia and of society. Pan-African struggles (although not complete) should be explored as the most important global contributions to resisting and overcoming racist, capitalist, imperial conquest and therefore should feature prominently in any psychological exploration of contemporary human life.

Pan-Africanism is a philosophy of African unity based on the recognition of the common experience of black oppression. Pan-Africanism is at once a political agenda, an economic project, a socio-cultural movement, and an intellectual quest to center black life and claim Africa as a place of belonging, physically, psychologically, and spiritually. Despite the psychological nature of many pan-African ideas of African unity seen through the theorizations of N��gritude, Afrocentricity, black nationalism, black consciousness, and pan-African feminisms, there is a dearth of engagement of these concepts in mainstream psychological research and in the formal teaching of psychology.

African psychology emerged amongst African American psychologists in the 1970s, who proposed an African cosmology as its conceptual-philosophical framework. Assumptions of communal and cooperative life, collective responsibility and interdependence are seen as intrinsic to the humanity of African people. Emphasis is placed on culture, the spiritual and the metaphysical along with multiple epistemologies, including the mythical and metaphorical. This conceptual-philosophical framework presents an important shift away from a Euro-American paradigm focused on individualistic and segregationist principles and attempts to provide alternative analyses of racial origins, skin color, black intelligence, and the black self/personality. A central thrust is a rejection of scientific racism and an emphasis on one���s ���historical consciousness��� and the renewal of a ���collective spirituality.��� These theorizations have challenged the positivist and empirical principles of race science and propose instead a psychology of protest and rehabilitation.

The point of departure for African psychology is a common understanding of racism and its effects and offers scholars culturally specific classification systems to research the mental health of people of African descent. These instruments measure and analyze black people���s worldviews and personalities outside of Euro-American definitions of mental health. Some examples include the African Self-Consciousness Scale (ASCS) and the Belief Systems Analysis Scale (BSAS) that measure different aspects of black personality with a strong emphasis on African heritage, resistance, survival, and liberation.

Despite these very important developments, there is a tendency in African psychology to present uncritical and essentializing views. Debates on the origins of race, cultural attributes, or the nature of black intelligence and black personality, are located within a framework of biological, cultural, or essentialized difference. As a result, these theories do not necessarily present a critical engagement with the idea of ���race��� as a socio-political construct and reinforce ideas about ���races��� as naturally different. In similar ways, the reification of an African cosmology as collective and communal can, on the one hand, have the effect of promoting homogeneous and ahistorical views about Africa, overlooking ���prevalent and injurious African cultural practices;��� and, on the other hand, negate the individual agency and innovation that African subjects contribute to modern life, as we remain confined to the sphere of communalism and tradition. These ideas are based on the myth of race, tribe, and nation.

It is unclear therefore how these assumptions of African psychology would enable us to critically investigate the concerning levels of violence in our communities, including racialized, xenophobic, gendered, and sexual violence in South Africa and elsewhere without further falling into the trap of pathologizing the perpetrators and their victims as ���un-African.��� Such criticisms have already been raised over claims of homosexuality being un-African. Indeed, African psychology has not invested sufficiently in questions of gender and sexuality. African feminists have noted the continued erasure of women���s political agency in the nationalist project. Narrow, masculinist nationalism has perpetuated normative gender roles and the control of women���s productive and reproductive labor and sexuality. The assumptions of communality, collective responsibility, and interdependence in African psychology, although valid as aspirational values, may have the unintended effect of pathologizing those whose behaviors fall outside of these prescribed norms.

African feminist thought offers critical and more nuanced insights into the intersecting and interlinked experiences of black oppression. A pan-African feminist lens shows how the myth of common biological or ethnic origins and cultural values reinscribes ideas about membership to a national collective in which the position of women and LGBT people remains precarious. The violence of forced sterilizations of black women instituted through population policies and legitimized under the guise of race science is arguably being perpetuated in other ways through the preoccupation and control over women���s sexuality, the criminalization of homosexuality and the practice of ���corrective rape��� that are justified through notions of a common African culture.

African feminists and anti-colonial feminists privilege instead the type of research that focuses on contemporary social challenges without making claims to ���know��� others, their cultures or personalities. These contributions focus on participatory, narrative, and archival work, and the type of memory work that brings people together in conversations, dialogues, exhibitions, performances���or pluriversal knowledges���that promote collective consciousness, mobilization, and activism within a clear agenda for social justice. These insights may be the key to advancing African psychology as a psychology of protest, collective resistance and liberation, and to engage in earnest with conceptions of blackness and Africanness, as well as the critical social challenges of our time.

July 15, 2021

South Africa���s gaping wounds

Photo by LT Ngema on Unsplash.

Photo by LT Ngema on Unsplash. Social unrest������though others may prefer ���riots and looting,��� ���food riots,��� or ���insurrection������have swept South Africa since Monday. It���s unsettled an already unsettled nation. And as with all South Africa���s heightened moments, our historic fault lines have been re-exposed. Racial and ethnic divisions, class antagonisms, xenophobia, questions of violence and its use. These are some of our wounds that have never been treated. Over the last decades we���ve covered them with patriotic bandages, unity slogans and surface-level performances of a shared national consciousness. But the wounds have opened again now, and as the country bleeds, the rot is open for all to see. Flashing moments tell an incomplete but tragic story of the reality unfolding in our country.

Impoverished communities with limited prospects, rejoice as they leave megastores with stolen food and essential resources. Elderly women are seen taking medication that they otherwise could not afford. A father exits a store with nappies (diapers) for his child. Families that have struggled with eating daily meals suddenly have food for a month.

Elsewhere, in the historically Indian community of Phoenix, an elderly man is surrounded by people from a nearby�� informal settlement. He is commanded that he needs to hand over his home, or otherwise will face attacks on his family in the dead of night. In the night, drive-by shootings claim lives as stray bullets shatter family homes.

Armed Indian and white ���vigilantes��� drive around shooting African people they assume are looters. Hunting them down while recording vicious videos, beating them with sjamboks as the person begs for their lives.

These videos are shared and watched repeatedly across social media, racially charged viewers salivate with a carnal sense of pleasure as one racial group watches the other suffer and bleed.

At least 15 people are killed by armed community members of Phoenix. They blockade roads entering the community, racially profiling people, preventing them from access to functioning supermarkets. Bodies are found in the night. #PhoenixMassacre trends on twitter echoing disgust and outrage at the anti-black sentiment within the South African Indian community.

The home of Thapelo Mohapi, the spokesperson of Abahlali BaseMjondolo, the shack dwellers movement in KwaZulu-Natal that safeguards working-class interests, has his home burnt down on Wednesday morning. Mohapi, like most in Abahlali, is outspoken against ANC corruption and political violence in the country, with Abahlali members often the targets for political killings.

Shacks burnt down in response to the looting. Reports of xenophobic attacks by the rioters. Families terrified as gunshots break their windows. Small community stores torched. Blood banks and clinics ransacked. Essential foods become scarce, gas stations close.

The excitement of people getting access to expensive TVs, furniture, alcohol, and commodities they would not be able to access otherwise. Because in South Africa we know that nice things are reserved for a minority���and you either have to be crazy lucky and gifted, or crazy devious and connected, to escape the poverty cycle.

This is the status quo of our neocolonial, violent and divided country. Every snapshot from the riots reveals a new layer of a tragedy we���re all too familiar with but have made no substantial material effort to address to this point. And now the rot in our open wound has become septic.

In the midst of all this mess and complexity, many are now left trying to make sense of where they stand regarding these riots���with the mask of a shared national consciousness being ruthlessly peeled back ��� some who thought they understood their political standings are having to rethink their position after being thrust into a violent situation where racial and class perceptions pre-determine their position for them.

Orchestrated or Inevitable?A central question on people���s minds is who is responsible for the unfolding events. How much of it is orchestrated as part of the #FreeZuma campaign that sparked this moment with former President Zuma���s arrest, and how much is simply an overflow from the desperate situation a majority of South Africans find themselves in. The reality is, of course, complex. Reports from activists on the ground and observers indicate the riots are likely made up of multiple forces.

Some are believed to be political agents of the pro-Zuma faction of the African National Congress ANC, using chaos to fight their battle against President Cyril Ramaphosa. These agents are known to have organized the initial demonstrations and are believed by some commentators to continue funding transport for rioters and operating in the background to hamstring the local economy. Some now attribute this orchestrated terror with the targeted burning of key distribution centers, factories, network towers, and trucks.

Others involved are not politically linked to a factional ANC agenda or desire to destabilize the country. They are there because the moment has presented families with access to food under dire circumstances and the opportunity for temporary relief from the dredges of poverty. One may say that their situation is being purposefully manipulated by political agendas, but the material reality of their situation is no less real. Individuals from well-known working class organizations that are strongly anti-ANC in all forms have reported taking part in looting as the moment allowed for sorely needed aid to struggling communities.

And of course, with any mass gathering, there are simply those criminal elements who use the moment with malicious intent, stirred by past and present grudges, looking to impose power and fear on those they see as ���other.��� Yet, these malicious sentiments exist on both the ���sides��� of the rioters and those responding to them. It is every person���s right and entitlement to defend themselves, their family, and personal property from harm against malicious forces. But much of this defence and protection of what is dear�� has morphed into older desires to harm, dehumanize, and kill those considered ���other.��� How much of our violence in the name of defence is rooted in the historic rot we���ve left untreated from colonialism, apartheid, and a world that hates poor people?

Military interventionMany are in support of the President Cyril Ramaphosa���s position that the army be deployed to quell the riots, looting, and violence. They argue for an armed, militant, and potentially lethal response.

Part of this rationale is in response to the signs of orchestration and mobilization by pro-Zuma political forces. As some of the actions show signs of being organized and targeted strikes, they will not subside organically and so the use of intelligence and organized force would be necessary to intervene. This tactical move acts in support of the President Cyril Ramaphosa and preserving the current status quo of South Africa.

The other reason is that the racial conflict between communities has reached such a heightened state that many fear an echo of the Durban Riots of 1949. With armed vigilantes enacting destruction, racial profiling, and vicious killing onto those they brand ���looters�������� and the responsive revenge cycles this opens up���there can be no road that does not lead to further death. And right now there is no Steve Bantu Biko and his dear friend Strini Moodley to lead us back on the path towards a more human face.

However, even in the face of this leadership vacuum, military intervention is short sighted, ahistoric, and temporary at best. The wounds are all open now, the military cannot heal, only repress.

Ultimately the scale and intensity of these riots have very little to do with political infighting within the ANC and the tensions between communities could not be set alight if there was not already kindling of unresolved tensions. The material conditions of South Africa indicate that it���s been ripe for mass political uprising for years now. With grants cut under lockdown, youth unemployment nearly 70%, service delivery a mess or none existent, trust in government, media and political parties at record lows���there seems to be meagre hope for South Africans on the wrong side of the poverty line���and very little to lose.

Whether it���s an orchestrated plot by devious political agendas, a student throwing poop on a colonial statue or an increase in bread prices as was seen in South America���a spark is all that���s needed to set alight a desperate people.

The best case scenario with military intervention this time is further repression of people���s material frustrations. If people die, the situation becomes further inflamed. When the next spark goes off the riots will be more organized, with living memory of the injustices of this moment. And if not organized by our dysfunctional Left, it will be led by reactionary forces. Most dangerous of all is, as with other examples from history, as military forces play a greater role in a country���s internal policing, they become more used to enacting power over its populace, and ambitious autocrats rise up their ranks in military command.

With military intervention, we admit that the violence and death that will be enacted on the working class populace is worth a return to South Africa���s abnormal normal. The violence of this moment simply transferred back to those who held it silently a week ago.

Repression and military enforcement of a violent status quo is not the answer. Material conditions need to change, people need to be fed, grants need to be returned and our septic wounds that have laid open for centuries need urgent attention.

If there is no material justice and investment in healing the generations of harm enacted onto us���and by us���the rot in our wounds will overcome us. And we will become the rot.

Rage as love under duress

Photo by Gabe Pierce on Unsplash.

Photo by Gabe Pierce on Unsplash. Two of South Africa���s most populous provinces are on fire. Others teeter on the brink. Together with many others who are observing this iteration of the smoldering blaze, I am caught in the confluence of all kinds of emotions. My sisters and their children live at the center of the fire that is raging in Pietermaritzburg. They are terrified. Even though I am observing the fires from Maputo, their horror at the destruction is an affect that they have drawn me into as well. Social media is flush with the devastating images. Acquaintances have lost businesses that they remain mired in debt over. I have internalized the fear of my family and others whose terror I watch on Twitter. In moments of life altering change, we are usually counseled to sit respectfully and to learn from the experience. For this reason and because I am depleted by the effects of COVID-19 on African lives, and as a consequence of the conflicting emotions jostling within me, I had decided to be quiet and to learn.��

Over the past decade, I have been thinking of the rogue emotion of collective rage that occasionally surfaces and sweeps us in its wake. For this reason, Pumla Gqola tweeted asking that I remind tweeps about the work of collective rage in this moment. I write in response to this invitation to think through the lessons of rage and its fires. To begin with, we might think of rage as intentional and networked anger rather than as a free standing emotion. Rage builds on sedimented anger but it is not reducible to anger. It transforms individual grievances into shared problems and structures anger into collective action. In the words of Fred Motem, rage is love and care under duress. This is because it forces the downtrodden to choose themselves and assert their presence even when the world has blotted them out.��

To rage is to say, ���fuck it, I love myself too much to allow this.��� Steve Biko reminded us that we are either alive or dead and when we die, we don���t care anyway. Rage is patterned on history because the grievances build up over time and their expression finds resonance with old and evolving forms of protest. I do not have to remind the reader of just how deep South Africa���s protest history goes and how it folds into and out of social sanction and respectability���attributions of good and bad. Following the old feminist adage, the personal (anger) becomes political (rage). Because of what it represents and does, property has always been the target of rage.������

These protests and looting bare the hallmarks of rage. Unemployment sits between 60 and 80 percent among black youth. Many are unemployable. They watch us live comfortably and they see the excess of jet setting Moet lives. Businesses come to squarely represent excess. They���ll never get jobs at a shopping centre or mall from which they are routinely chased out and seen���with justification at times���as potential thieves. In Pietermaritzburg there are tons of young men that sleep on the streets, in parks, under shop awnings, bridges, road overpasses, and the city���s cemeteries. Everyone knows to look out for the ���paras��� despite this being the seat of the unseeing provincial government. The ���paras��� broke into my sister���s house twice while the family slept. The children are traumatized. The ���paras���want food. Some take drugs to numb the pain. And then they need money to buy the drugs. Because they already live in the street, their fate is not tied to the cashiers and waiters who work at the burning shopping centers. This is to say that if their mothers and cousins lose their jobs as a consequence of a burned shop, this will not have material bearing on their overlooked lives. And those who are not homeless already live precarious lives. They see the dimness of their futures.��

When someone strikes a match and invites them to take from the shops, the young people are more than ready to rage and eat. Even if for a day or two. The feeling of fleeting control is priceless. To watch the things that taunt and mock you go up in flames is to finally experience the adrenaline of living. It is to turn the world upside down so that we can all feel the destabilizing effects of marginality. With or without shops in the neighborhood, they will always experience hunger and humiliation. So they don���t believe that they are cutting their own noses. Today is their day. For today, it is we who are terrified and uncertain. Tomorrow they will watch us rummage through the ashes. They know the feeling too well. They live in urine stained ashes.��

With reference to the Vietnam war, Spike Lee���s protagonist in Da 5 Bloods says ���No one should use our rage against us. We own our rage.��� It is apt here. Jacob Zuma and his children have attempted to own the rage of the unemployed. Those they forsook and overlooked when they led the rampant feeding at the trough of political patronage. Now they seek to use the rage of the forsaken to fight the reckoning that must follow reckless and wanton corruption that robbed the poor and swelled the ranks of the unemployed. They lit the match and tossed it. It has landed on dry tinder. Now the flames are engulfing us.��

On this precipice, we too have to sit with the warning. ���No one should use our rage against us.��� As the middle classes and the tenuously employed working classes, do we hit out at the raging youth or do we help in closing the growing gulf between the poor and the wealthy. Not through slogans about old Stellenbosch money, but our own money, political decisions, and privilege that we use to build walls around our properties. Even if we got our hands on all the white Stellenbosch money and imprisoned apartheid generals and war mongers, our problems will not be overcome. Not to use the rage of the unemployed calls on us to end our problematic relationship to property and to recenter the public good. It is insufficient to take care of our families and to complain about black tax. It is to take seriously that the raging youth own their rage and that it is an expression of their self-love under duress. We might condemn their destruction of property but to take rage seriously is to reconsider the social role of property not as enrichment but as public good. This moment is one of reckoning. It shines the spotlight on the government���s ineptness, the fissures between us, and the violence of property.��

Perhaps the rage will die down in a few days. Rage always burns itself out. But all it needs are reckless political feeders who thrive on attention and self-importance to light the kindling. Proxy political battles, xenophobes, fascists and others will fill the yawning fissures of inequality. We will return to this place again. We have been here before. Those old enough to remember the fires of the 1980s and the transition years know the fires of rage. Those who came of age in the 1970s nurse the burns of the Soweto and Langa uprisings. The Durban strikes. And earlier still, in the 1960s, the Mpondo revolt and Sharpeville massacre had their own fires. The women who marched on the Union Buildings know the heat of rage.��

To riff off James Baldwin, there will be a fire next time. The embers and kindling are in place. What matters is what we do between this fire and the next.��

July 14, 2021

Another hero falls

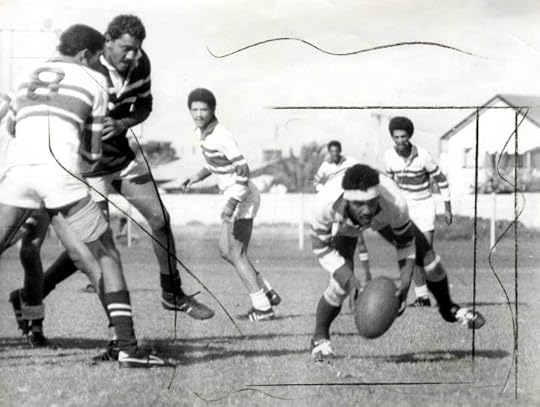

Photo credit Lennie Himson. The image was scanned at the Kimberley Africana Research Library.

Photo credit Lennie Himson. The image was scanned at the Kimberley Africana Research Library. Eric ���Bucs��� Damons, who died May 12, 2021 in Kimberley, South Africa, was a legend of black rugby. Nobody within the current Griqualand West Rugby Union (GWRU) rugby circles will know his name. Not many within the old national South African Rugby Board (SARB) and the now South African Rugby Union (SARU) framework will know his name, nor will they care that he ever existed. But the tragedy of South Africa���s transition to ������democracy������ can be superbly explored through the lens of what has happened to sport within oppressed communities and to the memories of players like Damons while they were still alive.

A player of incredible talent, “Bucs” wasted away over the past few years. His stomping grounds, the AR Abass Stadium in Kimberley, stands like a silent tumor that grows with every death of the heroes that once gave it purpose. Eric ���Bucs��� Damons existed beyond the frame of the narrow scope of the elite South African sporting narrative. He is, in terms of this narrow view, of no particular importance or significance. The system that denied him his rightful place as a South African rugby legend is alive and well and currently under black management. It is supported, endorsed, and rubber-stamped by the victims and their descendants, of the very policies that denied them their place in the sporting sun during the hard days of legislated racism.

Today apartheid sporting policy is less transparent. It sneaks around feasting on the corpses of fallen community sporting heroes, denied space and place by the expediency of the ANC-managed sports unity deals, which coincidentally, was ratified in the city of Eric���s birth���Kimberley. It was this deal that slowly killed ���Bucs.���

I was not old enough, nor was I ever good enough to play against ���Bucs.��� I saw him play in countless fixtures, and he was truly a sight to behold. His tall, wiry frame belied his strength, skill, and athletic prowess. I do not know anything about his training regimen, but from what I can remember, he performed some amazing feats on the rugby field. He loved, above all else, his club, Young Collegians RFC. The club died with the era of so-called unity. (The period refers to the negotiations to unite the segregrated sports bodies of Apartheid in the early 1990s, which effectively resulted in black sports bodies, particularly in sports like rugby and cricket, being swallowed by the more financially resourced former white sports associations.) It was a blow that shattered many lives, not only in Kimberley, but across the country where rugby was played for reasons that are worth far more than filthy lucre.

In my minds eye, I can see Bucs loping from the base of the scrum, his long legs punctuated by boots that could well have been designed for Goofy. Very often one of his hands would be gripping the large leather ball as he used the other to fend off would be tacklers. His cartoon-like gait always included a sudden turn of speed, which would see him burst through gaps as he rallied his troops toward the try line. In Kimberley rugby circles, Bucs stands alongside other legends such as Mr. Bunny Hermanus, Piet Van Wyk, Dennis Jacobs, Jaap Kruger, Toby Ferris, Freddie Fredericks, and others. It has always been a contentious issue that “Bucs” was never selected for SARU. (This is different from the current SARU and refers to the original, non-racial national rugby union affiliated to the South African Council on Sports, which in turn was allied to the anti-apartheid movement and agitated for ���no normal sport in an abnormal society.���)�� He certainly had the rugby acumen and was a fearsome opponent. Upon reflection at his omission from SARU honors, it in a way lifts the burden from his shoulders of having had to adorn the cloak of those who denied him in the first place. In South Africa, rugby justice is provided by allowing those who were suppressed by apartheid policies, to adorn the colors of the proud sporting symbol of apartheid���the springbok.

South Africa���s post-apartheid sporting dementia has worsened as is evidenced by the circus at the Cricket South Africa�� as well as the shenanigans at SASCOC (South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee). The victory in the 2019 Rugby World Cup tournament by the springboks led by Siya Kolisi, has steered attention away from the stench of the longest rotting corpse in history���the springbok. This year, all eyes turn to the pending tour of the British and Irish Lions, long supporters of the system of sporting apartheid, and supporters of the system of convenient amnesia. A system that continuously and purposely denies the existence of heroes such as Bucs Damons.

On Friday, May 7, 2021, Mr. Abubacker ���Baby��� Richards also passed away. Mark Alexander, president of SARU, posted a tribute to Mr. Richards, a former president of the GWRU and said: ���He was president of Griquas both before and after unity in rugby and whether he served as secretary, referee, president or chairman in rugby, he did so with much integrity and ability.���

Despite his years of service, even within the poisonous space of unified rugby in Kimberley, Mr. Richards features in a nameless photograph on page 30 in the 2011 publication ���Diamonds in the Rough 125 Years of Griqua Rugby 1886-2011.��� The publication, edited by rugby writer Wim van der Berg, does not even include ���unity��� as a memorable moment in the timeline of significant events on pages 39 through to 45. Unity, in the eyes of South African rugby, is an inconvenient blip on an otherwise untrammeled historical pathway. The suppression of sporting truth is the primary objective of the custodians of the game in South Africa.

The publication lauds the legends of Griqualand West Rugby on pages 50 through to 58, including names such as Ian Kirkpatrick, Piet Visagie, Gawie Visagie, Flippie van der Merwe, Andre Markgraaf, Dawie Theron and others; ll players who played for the whites only team of Griques under Apartheid. Bucs Damons is not mentioned. He is not alone in this, as not a single player from the non-racial fold is mentioned. They never existed and in the words of writer Wim van der Berg in an email from GWRU to the author: